Submitted:

13 October 2024

Posted:

16 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Seed Priming as a Strategy to Overcome the Negative Effect of Stresses on Plants

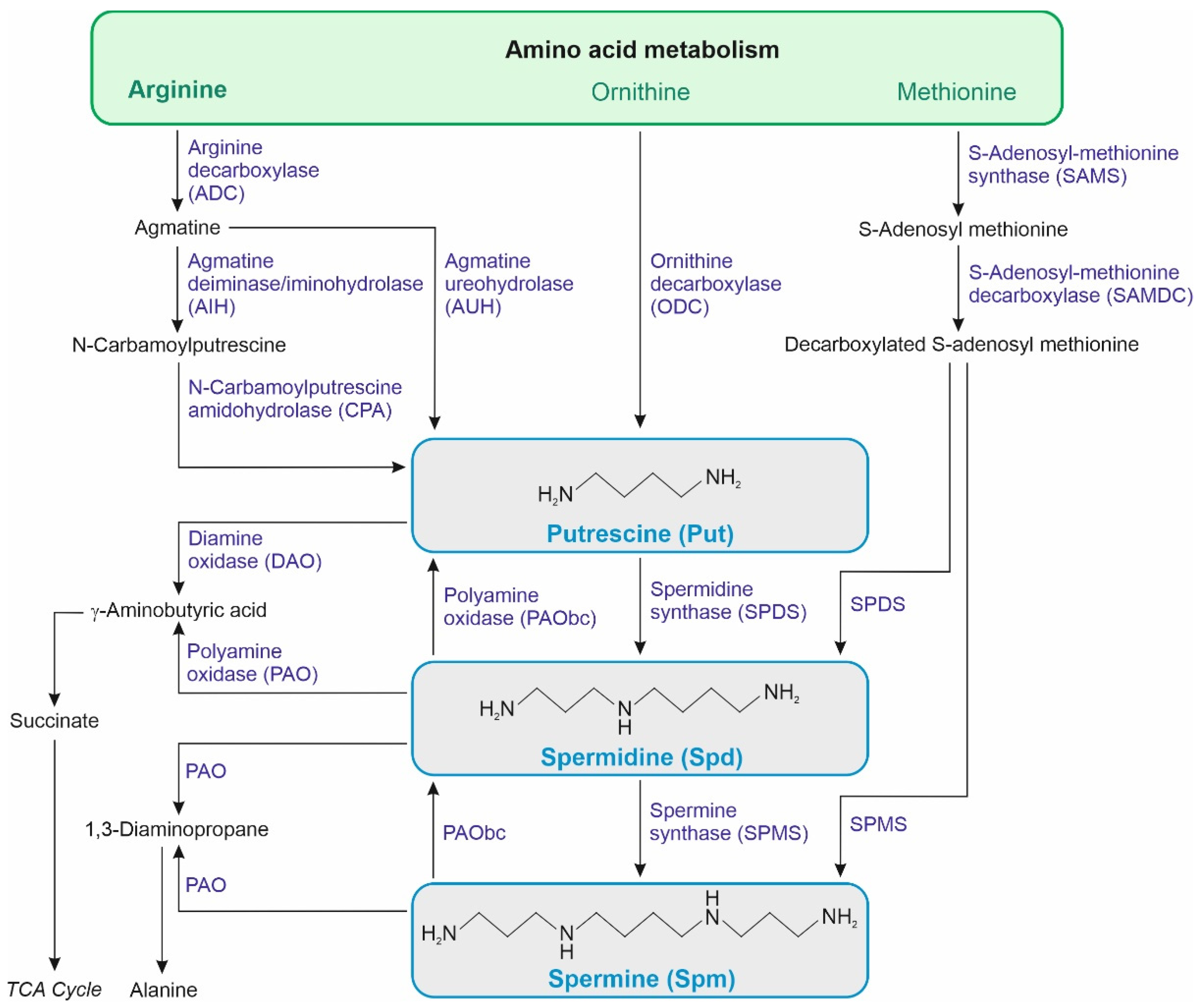

2. Polyamines as Regulatory Molecules That Impact Plant Stress Responses

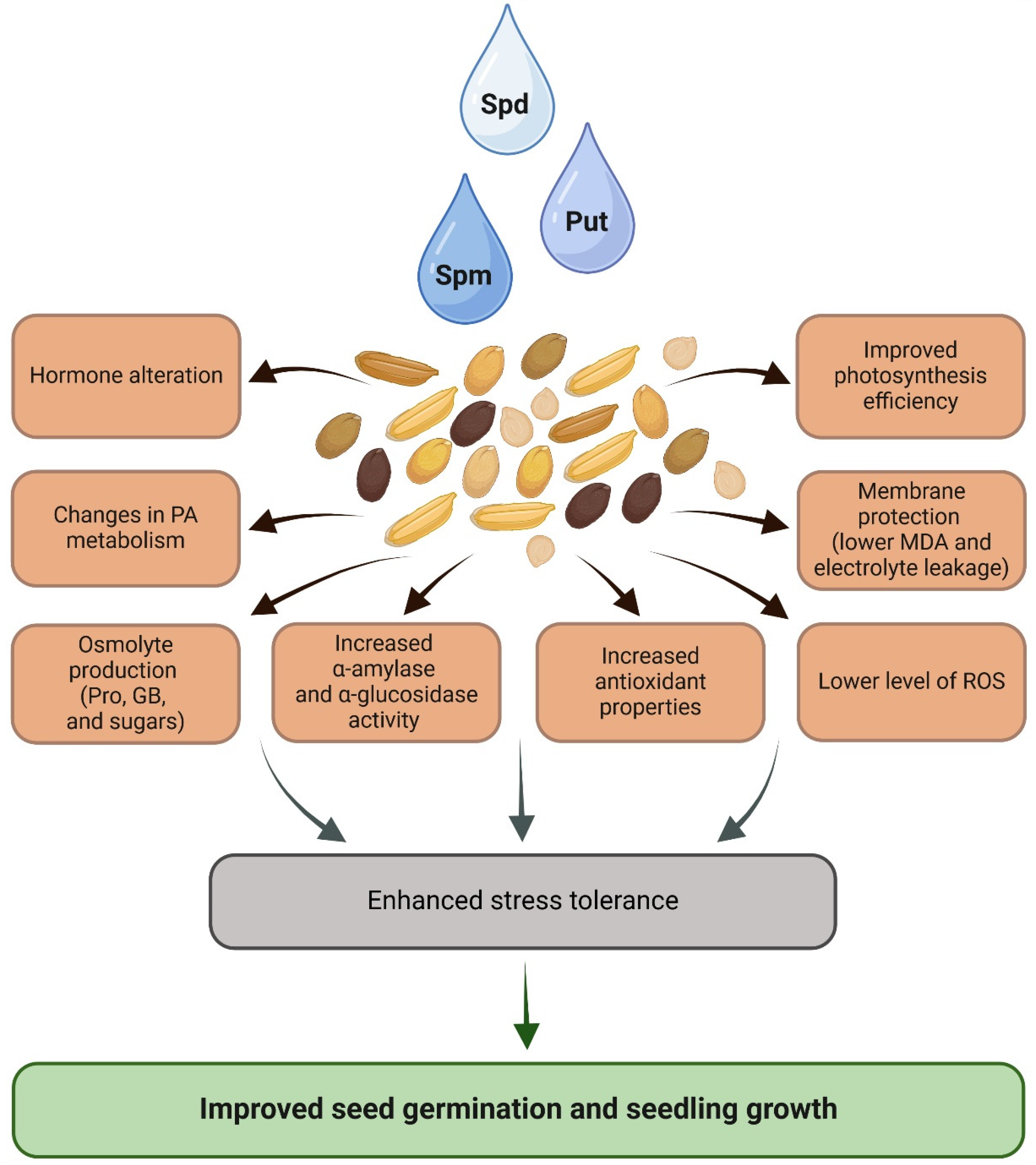

3. Polyamine Seed Priming as a Way to Modify Plant Metabolism and Improve Stress Resistance

| Plant species | Stress | Priming agent | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acer saccharinum L. | Mild and severe desiccation | Spd |

|

[58] |

|

Brassica napus L. cv. SY Saveo (sensitive), Edimax CI (intermediate tolerant), and Dynastie (tolerant) |

Salinity | Spd Spm |

|

[46] |

|

Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala |

Chilling | Spd |

|

[56] |

|

Chenopodium quinoa Willd. |

Salinity | Spd Spm |

|

[66] |

|

Cucurbita pepo var. styriaka |

Salinity | Put |

|

[47] |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. MSk326 (sensitive) and Honghuadajinyuan (tolerant) |

Chilling | Put |

|

[59] |

|

Solanum lycopersicum L. cv. Principe Borghese |

Salinity | Put Spm Spd |

|

[60] |

|

Oryza sativa L. ssp. Japonica cv. Zhegeng 100 |

Heat | Spd |

|

[57] |

|

Oryza sativa L. cv. Chunyou 927 (sensitive), and Yliangyou 689 ( tolerant) |

Chromium | Spd |

|

[49] |

|

Oryza sativa L. cv. Chunyou 927 (sensitive) |

Chromium toxicity | Spd |

|

[50] |

|

Oryza sativa L. cv. Khao Dawk Mali 10 |

Salinity | Spd |

|

[65] |

| Oryza sativa L. | Chilling | Spd |

|

[61] |

| Oryza sativa L.cv. IR-64 | Salinity | Spd |

|

[51] |

|

Oryza sativa L. cv. Zhu Liang You 06 and Qian You No.1 |

Chilling | Spd |

|

[62] |

|

Oryza sativa L. cv. Gobindobhog |

Salinity | Spd Spm |

|

[52] |

|

Oryza sativa L. cv. IR-64 (sensitive) and Nonabokra (tolerant) |

Salinity | Spd Spm |

|

[53] |

|

Oryza sativa L. cv. viz., Huanghuazhan (HHZ, inbred) and Yangliangyou6 (YLY6, hybrid) |

Drought | Spd |

|

[63] |

|

Oryza sativa L. |

Chilling | Spd |

|

[64] |

|

Oryza sativa L. cv. Niewdam (tolerant) and KKU-LLR-039 (sensitive) |

Salinity | Spd |

|

[48] |

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evenari, M. Seed Physiology: Its History from Antiquity to the Beginning of the 20th Century. Bot. Rev. 1984, 50, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanos, C.A. Theophrastus the Founder of Seed Science - His Accounts on Seed Preservation. ENSCOnews 2007, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, A.B.; Raj, S.K. Seed Priming: An Approach towards Agricultural Sustainability. JANS 2019, 11, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, R.; Tripathi, S.; Devi, R.S.; Srivastava, P.; Singh, P.; Kumar, A.; Bhadouria, R. Seed Priming: State of the Art and New Perspectives in the Era of Climate Change. In Climate Change and Soil Interactions; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 143–170 ISBN 978-0-12-818032-7.

- Heydecker, W. Germination of an Idea: The Priming of Seeds. School of Agriculture Research, University of Nottingham 1973, 50–67.

- Di Girolamo, G.; Barbanti, L. Treatment Conditions and Biochemical Processes Influencing Seed Priming Effectiveness. Ital. J. Agronomy 2012, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajjou, L.; Duval, M.; Gallardo, K.; Catusse, J.; Bally, J.; Job, C.; Job, D. Seed Germination and Vigor. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 507–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparella, S.; Araújo, S.S.; Rossi, G.; Wijayasinghe, M.; Carbonera, D.; Balestrazzi, A. Seed Priming: State of the Art and New Perspectives. Plant Cell Rep 2015, 34, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutts, S.; Benincasa, P.; Wojtyla, L.; Kubala, S.; Pace, R.; Lechowska, K.; Quinet, M.; Garnczarska, M. Seed Priming: New Comprehensive Approaches for an Old Empirical Technique. In New Challenges in Seed Biology - Basic and Translational Research Driving Seed Technology; Araujo, S., Balestrazzi, A., Eds.; InTech, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Jisha, K.C.; Vijayakumari, K.; Puthur, J.T. Seed Priming for Abiotic Stress Tolerance: An Overview. Acta Physiol Plant 2013, 35, 1381–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthandan, V.; Geetha, R.; Kumutha, K.; Renganathan, V.G.; Karthikeyan, A.; Ramalingam, J. Seed Priming: A Feasible Strategy to Enhance Drought Tolerance in Crop Plants. IJMS 2020, 21, 8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Tiwari, S.; Kataria, S.; Anand, A. Recent Advances in Seed Priming Strategies for Enhancing Planting Value of Vegetable Seeds. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 305, 111355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtyla, Ł.; Lechowska, K.; Kubala, S.; Garnczarska, M. Molecular Processes Induced in Primed Seeds—Increasing the Potential to Stabilize Crop Yields under Drought Conditions. Journal of Plant Physiology 2016, 203, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, A.; Macovei, A.; Balestrazzi, A. Molecular Dynamics of Seed Priming at the Crossroads between Basic and Applied Research. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 657–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, E.A. Seed Priming to Alleviate Salinity Stress in Germinating Seeds. Journal of Plant Physiology 2016, 192, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.; Puthur, J.T. Seed Priming as a Cost Effective Technique for Developing Plants with Cross Tolerance to Salinity Stress. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2021, 162, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, P.; Dwivedi, P. Seed Priming and Its Role in Mitigating Heat Stress Responses in Crop Plants. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 2021, 21, 1718–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Dey, S.; Kundu, R. Seed Priming: An Emerging Tool towards Sustainable Agriculture. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 97, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, T.J.A.; Matthes, M.C.; Napier, J.A.; Pickett, J.A. Stressful “Memories” of Plants: Evidence and Possible Mechanisms. Plant Science 2007, 173, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrath, U.; Beckers, G.J.M.; Langenbach, C.J.G.; Jaskiewicz, M.R. Priming for Enhanced Defense. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2015, 53, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Medina, A.; Flors, V.; Heil, M.; Mauch-Mani, B.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Pozo, M.J.; Ton, J.; Van Dam, N.M.; Conrath, U. Recognizing Plant Defense Priming. Trends in Plant Science 2016, 21, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhi, P.; Chang, C. Priming Seeds for the Future: Plant Immune Memory and Application in Crop Protection. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 961840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Arora, R. Priming Memory Invokes Seed Stress-Tolerance. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2013, 94, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.J.; Amtmann, A.; Ton, J. Epigenetic Processes in Plant Stress Priming: Open Questions and New Approaches. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2023, 75, 102432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, J.; Huang, K.; Batool, M.; Idrees, F.; Afzal, R.; Haroon, M.; Noushahi, H.A.; Wu, W.; Hu, Q.; Lu, X.; et al. Versatile Roles of Polyamines in Improving Abiotic Stress Tolerance of Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1003155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Shao, Q.; Yin, L.; Younis, A.; Zheng, B. Polyamine Function in Plants: Metabolism, Regulation on Development, and Roles in Abiotic Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcázar, R.; Bueno, M.; Tiburcio, A.F. Polyamines: Small Amines with Large Effects on Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Cells 2020, 9, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez, M.A. Polyamines: Their Role in Plant Development and Stress. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2024, 75, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Lv, A.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, A.; Xu, X.; Shao, Q.; Zheng, Y. Exogenous Spermidine Enhanced the Water Deficit Tolerance of Anoectochilus Roxburghii by Modulating Plant Antioxidant Enzymes and Polyamine Metabolism. Agricultural Water Management 2023, 289, 108538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Pan, X.; Jiang, Q.; Xi, Z. Exogenous Putrescine Alleviates Drought Stress by Altering Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging and Biosynthesis of Polyamines in the Seedlings of Cabernet Sauvignon. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 767992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özmen, S.; Tabur, S.; Öney-Birol, S.; Özmen, S. The Effect of Exogenous Spermine Application on Some Biochemichal and Molecular Properties in Hordeum vulgare L. under Both Normal and Drought Stress. Biologia 2022, 77, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legocka, J.; Sobieszczuk-Nowicka, E.; Wojtyla, Ł.; Samardakiewicz, S. Lead-Stress Induced Changes in the Content of Free, Thylakoid- and Chromatin-Bound Polyamines, Photosynthetic Parameters and Ultrastructure in Greening Barley Leaves. Journal of Plant Physiology 2015, 186–187, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Hou, J.; Gao, W.; Tong, X.; Li, M.; Chu, X.; Chen, G. Exogenous Spermidine Alleviates the Adverse Effects of Aluminum Toxicity on Photosystem II through Improved Antioxidant System and Endogenous Polyamine Contents. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, 207, 111265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raziq, A.; Mohi Ud Din, A.; Anwar, S.; Wang, Y.; Jahan, M.S.; He, M.; Ling, C.G.; Sun, J.; Shu, S.; Guo, S. Exogenous Spermidine Modulates Polyamine Metabolism and Improves Stress Responsive Mechanisms to Protect Tomato Seedlings against Salt Stress. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2022, 187, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, L.S.; López-Climent, M.F.; Segarra-Medina, C.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Zandalinas, S.I. Exogenous Spermine Alleviates the Negative Effects of Combined Salinity and Paraquat in Tomato Plants by Decreasing Stress-Induced Oxidative Damage. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1193207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Gu, W.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Xie, T.; Qu, D.; Meng, Y.; Li, C.; Wei, S. Exogenously Applied Spermidine Alleviates Photosynthetic Inhibition under Drought Stress in Maize (Zea mays L.) Seedlings Associated with Changes in Endogenous Polyamines and Phytohormones. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, 129, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hao, J.; Fan, S.; Liu, C.; Han, Y. Role of Spermidine in Photosynthesis and Polyamine Metabolism in Lettuce Seedlings under High-Temperature Stress. Plants 2022, 11, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElSayed, A.I.; Mohamed, A.H.; Rafudeen, M.S.; Omar, A.A.; Awad, M.F.; Mansour, E. Polyamines Mitigate the Destructive Impacts of Salinity Stress by Enhancing Photosynthetic Capacity, Antioxidant Defense System and Upregulation of Calvin Cycle-Related Genes in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2022, 29, 3675–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napieraj, N.; Janicka, M.; Reda, M. Interactions of Polyamines and Phytohormones in Plant Response to Abiotic Stress. Plants 2023, 12, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhuang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, Z. Exogenously Applied Spermidine Alleviates Hypoxia Stress in Phyllostachys Praecox Seedlings via Changes in Endogenous Hormones and Gene Expression. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borek, S.; Morkunas, I.; Ratajczak, W.; Ratajczak, L. Metabolism of Amino Acids in Germinating Yellow Lupin Seeds III. Breakdown of Arginine in Sugar-Starved Organs Cultivated in Vitro. Acta Physiol Plant 2001, 23, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, M.; Hanfrey, C.C.; Murray, E.J.; Stanley-Wall, N.R.; Michael, A.J. Evolution and Multiplicity of Arginine Decarboxylases in Polyamine Biosynthesis and Essential Role in Bacillus subtilis Biofilm Formation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 39224–39238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yariuchi, Y.; Okamoto, T.; Noutoshi, Y.; Takahashi, T. Responses of Polyamine-Metabolic Genes to Polyamines and Plant Stress Hormones in Arabidopsis Seedlings. Cells 2021, 10, 3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, I.; Bourdais, G.; Gouesbet, G.; Couée, I.; Malmberg, R.L.; El Amrani, A. Differential Gene Expression of ARGININE DECARBOXYLASE ADC1 and ADC2 in Arabidopsis thaliana : Characterization of Transcriptional Regulation during Seed Germination and Seedling Development. New Phytologist 2004, 163, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Y.; Ahmed, S.; Yan, J.; Adio, A.M.; Powell, H.M.; Morris, P.F.; Jander, G. Arabidopsis ADC1 Functions as an N δ -acetylornithine Decarboxylase. JIPB 2020, 62, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stassinos, P.M.; Rossi, M.; Borromeo, I.; Capo, C.; Beninati, S.; Forni, C. Enhancement of Brassica Napus Tolerance to High Saline Conditions by Seed Priming. Plants 2021, 10, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farsaraei, S.; Mehdizadeh, L.; Moghaddam, M. Seed Priming with Putrescine Alleviated Salinity Stress During Germination and Seedling Growth of Medicinal Pumpkin. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 2021, 21, 1782–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunthaburee, S.; Sanitchon, J.; Pattanagul, W.; Theerakulpisut, P. Alleviation of Salt Stress in Seedlings of Black Glutinous Rice by Seed Priming with Spermidine and Gibberellic Acid. Not Bot Horti Agrobo 2014, 42, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, F.; Bhat, J.A.; Ulhassan, Z.; Noman, M.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, W.; Kaushik, P.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, P.; Guan, Y. Seed Priming with Spermine Mitigates Chromium Stress in Rice by Modifying the Ion Homeostasis, Cellular Ultrastructure and Phytohormones Balance. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, F.; Ulhassan, Z.; Mou, Q.; Nazir, M.M.; Hu, J.; Hu, W.; Song, W.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; Zhou, W.; Bhat, J.A.; et al. Seed Priming with Nitric Oxide and/or Spermine Mitigate the Chromium Toxicity in Rice (. Funct. Plant Biol. 2022, 50, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Roychoudhury, A.; Banerjee, A.; Chaudhuri, N.; Ghosh, P. Seed Pre-Treatment with Spermidine Alleviates Oxidative Damages to Different Extent in the Salt (NaCl)-Stressed Seedlings of Three Indica Rice Cultivars with Contrasting Level of Salt Tolerance. Plant Gene 2017, 11, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Roychoudhury, A. Effect of Seed Priming with Spermine/Spermidine on Transcriptional Regulation of Stress-Responsive Genes in Salt-Stressed Seedlings of an Aromatic Rice Cultivar. Plant Gene 2017, 11, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Roychoudhury, A. Seed Priming with Spermine and Spermidine Regulates the Expression of Diverse Groups of Abiotic Stress-Responsive Genes during Salinity Stress in the Seedlings of Indica Rice Varieties. Plant Gene 2017, 11, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, K.; Hirt, H. REACTIVE OXYGEN SPECIES: Metabolism, Oxidative Stress, and Signal Transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, N.; Jiang, C.; Chen, L.; Paul, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Shen, G. Achieving Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants through Antioxidative Defense Mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, D.; Huang, Y.; Mei, G.; Zhang, S.; Wu, H.; Zhao, T. Spermidine Enhances Chilling Tolerance of Kale Seeds by Modulating ROS and Phytohormone Metabolism. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Mei, G.; Cao, D.; Qin, Y.; Yang, L.; Ruan, X. Spermidine Enhances Heat Tolerance of Rice Seeds during Mid-Filling Stage and Promote Subsequent Seed Germination. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1230331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, H.; Plitta-Michalak, B.P.; Małecka, A.; Ciszewska, L.; Sikorski, Ł.; Staszak, A.M.; Michalak, M.; Ratajczak, E. The Chances in the Redox Priming of Nondormant Recalcitrant Seeds by Spermidine. Tree Physiology 2023, 43, 1142–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Ma, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, S. Chilling Tolerance in Nicotiana tabacum Induced by Seed Priming with Putrescine. Plant Growth Regul. 2011, 63, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borromeo, I.; Domenici, F.; Del Gallo, M.; Forni, C. Role of Polyamines in the Response to Salt Stress of Tomato. Plants 2023, 12, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Pan, R.; Hu, W.; Guan, Y.; Hu, J. Seed Priming with Spermidine and Trehalose Enhances Chilling Tolerance of Rice via Different Mechanisms. J Plant Growth Regul 2020, 39, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheteiwy, M.; Shen, H.; Xu, J.; Guan, Y.; Song, W.; Hu, J. Seed Polyamines Metabolism Induced by Seed Priming with Spermidine and 5-Aminolevulinic Acid for Chilling Tolerance Improvement in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Seedlings. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2017, 137, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Tao, Y.; Hussain, S.; Jiang, Q.; Peng, S.; Huang, J.; Cui, K.; Nie, L. Seed Priming in Dry Direct-Seeded Rice: Consequences for Emergence, Seedling Growth and Associated Metabolic Events under Drought Stress. Plant Growth Regul 2016, 78, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, P.-D.; Mohammad, K.-H.; Masoud, E. Alleviating Harmful Effects of Chilling Stress on Rice Seedling via Application of Spermidine as Seed Priming Factor. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 9, 1412–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theerakulpisut, P.; Nounjan, N.; Kumon-Sa, N. Spermidine Priming Promotes Germination of Deteriorated Seeds and Reduced Salt Stressed Damage in Rice Seedlings. Not Bot Horti Agrobo 2021, 49, 12130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, S.; Antognoni, F.; Marincich, L.; Lianza, M.; Tejos, R.; Ruiz, K.B. The Polyamine “Multiverse” and Stress Mitigation in Crops: A Case Study with Seed Priming in Quinoa. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 304, 111292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishnav, D.; Chowdhury, P. Types and Function of Phytohormone and Their Role in Stress. In Plant Abiotic Stress Responses and Tolerance Mechanisms; Hussain, S., Hussain Awan, T., Ahmad Waraich, E., Iqbal Awan, M., Eds.; IntechOpen, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Basra, A.S.; Singh, B.; Malik, C.P. Amelioration of the Effects of Ageing in Onion Seeds by Osmotic Priming and Associated Changes in Oxidative Metabolism. Biologia Plant. 1994, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechowska, K.; Wojtyla, Ł.; Quinet, M.; Kubala, S.; Lutts, S.; Garnczarska, M. Endogenous Polyamines and Ethylene Biosynthesis in Relation to Germination of Osmoprimed Brassica Napus Seeds under Salt Stress. IJMS 2021, 23, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutts, S.; Hausman, J.-F.; Quinet, M.; Lefèvre, I. Polyamines and Their Roles in the Alleviation of Ion Toxicities in Plants. In Ecophysiology and Responses of Plants under Salt Stress; Ahmad, P., Azooz, M.M., Prasad, M.N.V., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2013; pp. 315–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).