Submitted:

15 October 2024

Posted:

16 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

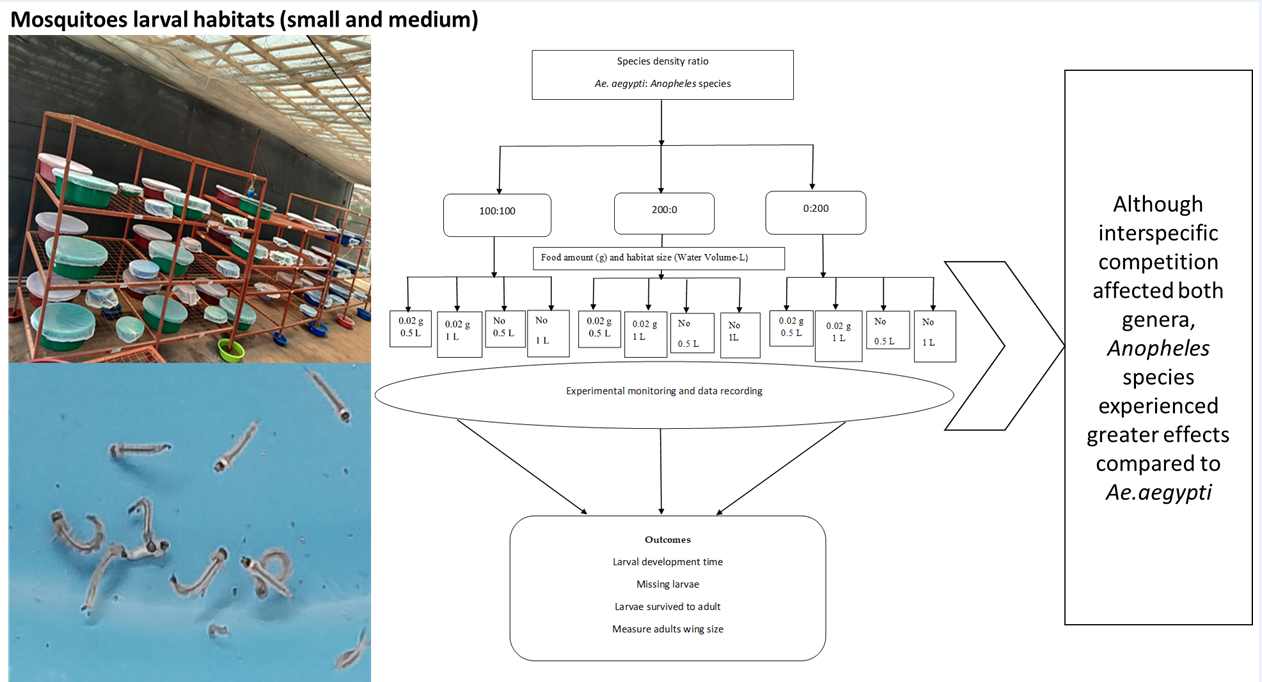

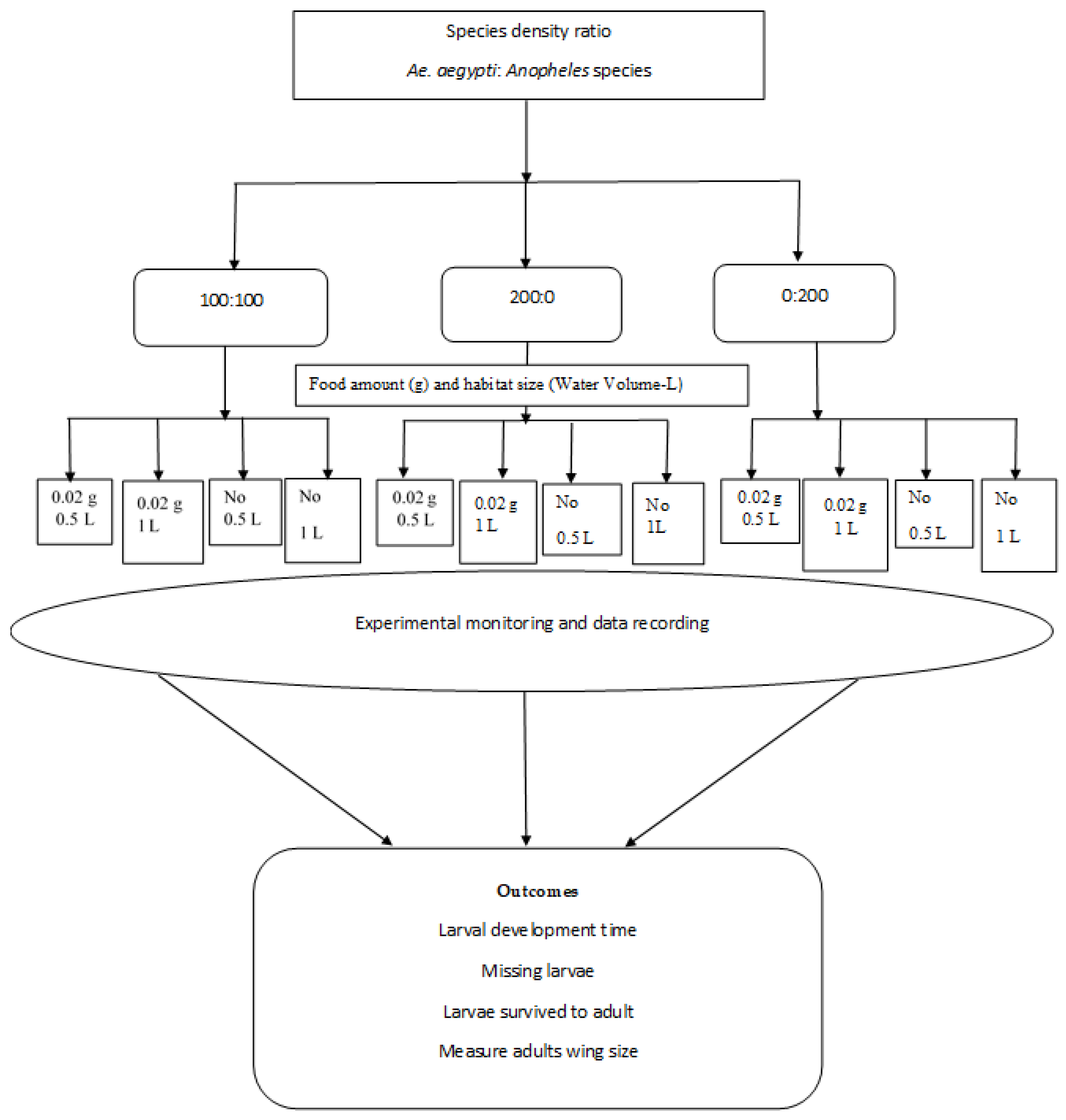

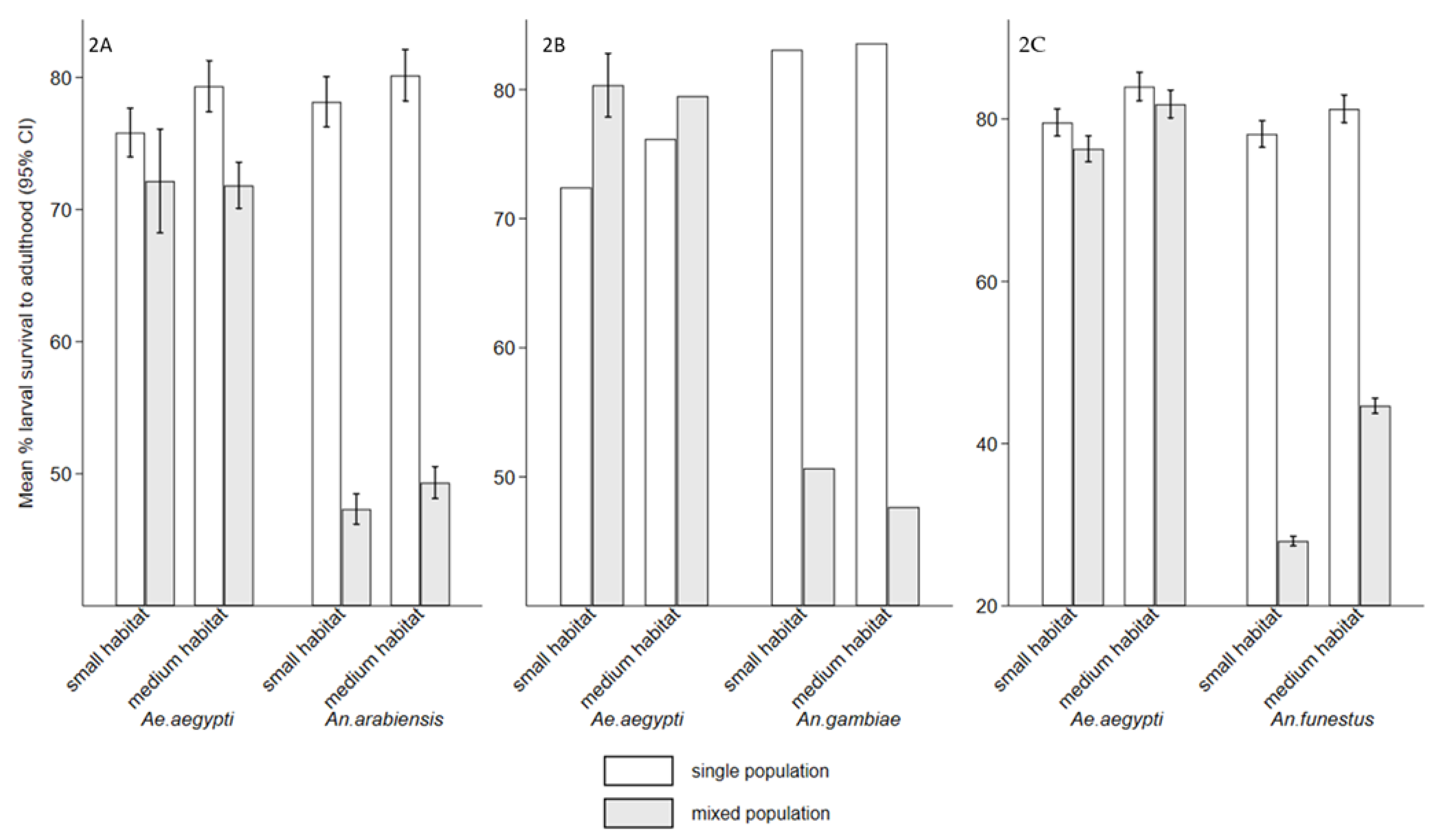

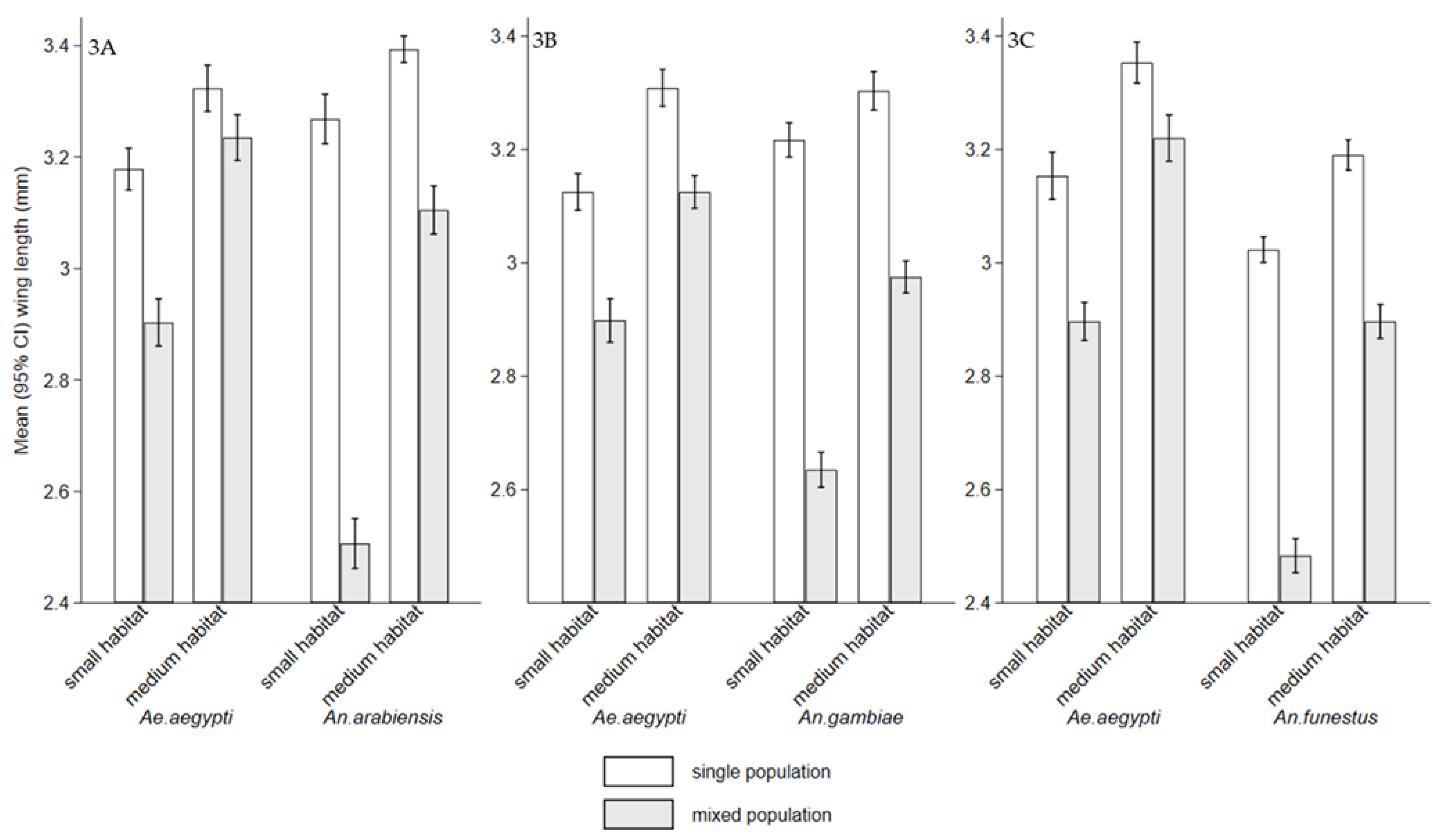

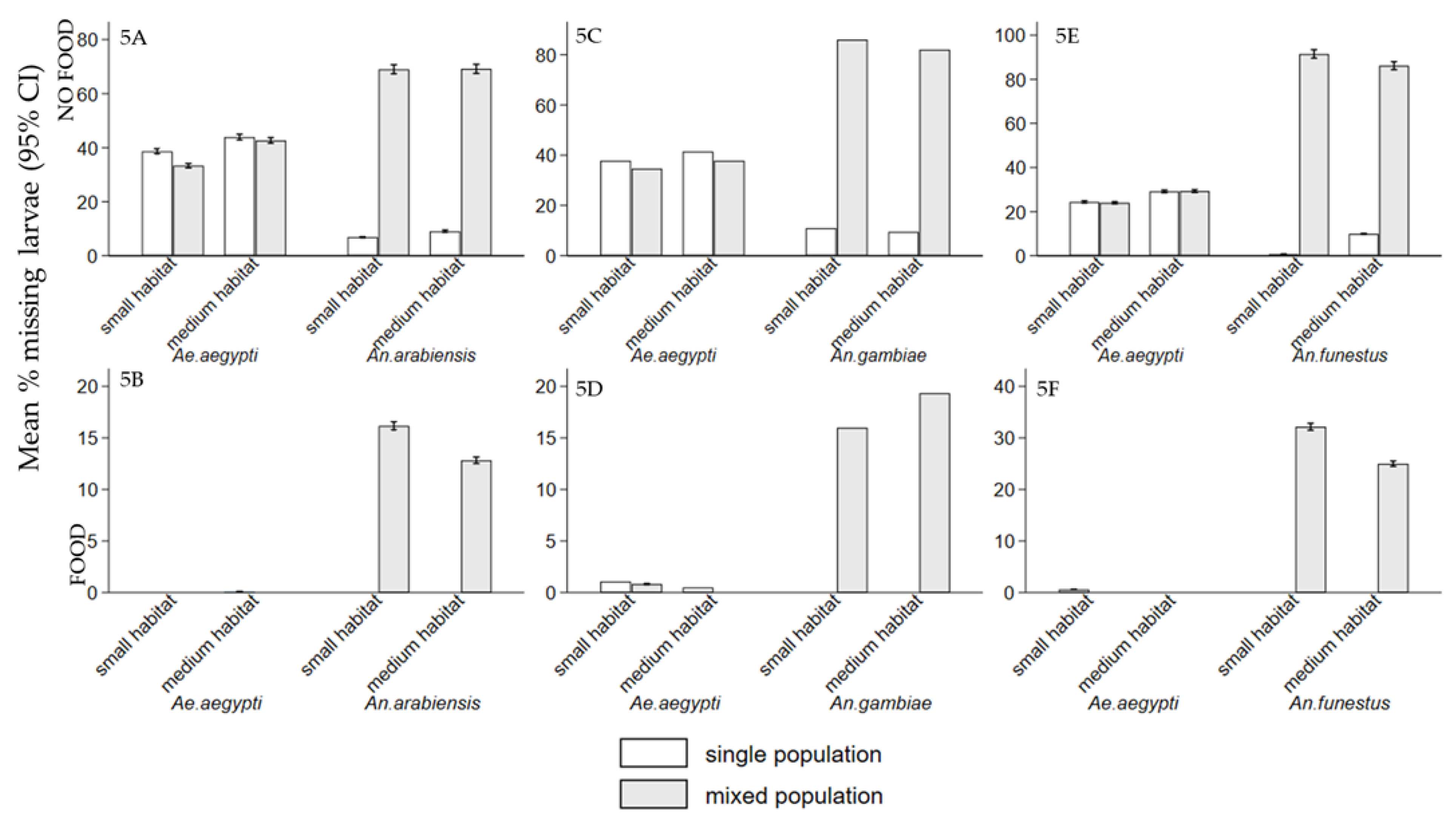

Interspecific competition between mosquito larvae may affects adult vectorial capacity, potentially reducing disease transmission. It also influences population dynamics, cannibalistic and predatory behaviors. However, knowledge of interspecific competition between Ae. aegypti and Anopheles species is limited. The study examined interspecific competition between Ae. aegypti larvae and either An. arabiensis, An. gambiae, or An. funestus on individual fitness in semi-field settings. The experiments involved density combinations of 100:100, 200:0, and 0:200 (Ae. aegypti: Anopheles), reared with and without food, in small habitat (8.5 cm height × 15 cm diameter) with 0.5 litre and medium habitats (15 cm height × 35 cm diameter) with 1 litre of water. The first group received Tetramin® fish food (0.02 g), while the second group was unfed to assess cannibalism and predation. While, interspecific competition affected both genera, Anopheles species experienced greater effect, with reduced survival and delayed development, compared to Ae. aegypti. The mean wing lengths of all species were significantly small in small habitats in mixed population (p < 0.001). The presence of food reduced cannibalism and predation compared to its absence. These interactions have implications for diseases transmission dynamics and can serve as biological indicators to signal the impacts of vector control interventions.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and methods

2.Study area

2.Study design

2.Larval habitats

2.Experimental procedures

2.Data collection

2.Data management and statistical analysis.

Results

3.Larval developmental time

3.Effects of competition on mosquito larvae survived to adults

3.Adults body size via wing length (mm)

Discussion

Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

Authors’ Contributions

Ethical Clearance

Data Availability and Materials

Publication Consent

References

- Wilkerson, R.C.; Linton, Y.-M.; Fonseca, D.M.; Schultz, T.R.; Price, D.C.; Strickman, D.A. Making Mosquito Taxonomy Useful: A Stable Classification of Tribe Aedini that Balances Utility with Current Knowledge of Evolutionary Relationships. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0133602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Global vector control response 2017-2030, WHO [Internett]. J. Sains dan Seni ITS. Hentet fra: http://repositorio.unan.edu.ni/2986/1/5624.pdf%0Ahttp://fiskal.kemenkeu.go.id/ejournal%0Ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2016.06.001%0Ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2016.12.055%0Ahttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2019.02.006%0Ahttps://doi.org/10.1.

- Fagbohun, I.K.; Idowu, E.T.; Awolola, T.S.; Otubanjo, O.A. Seasonal abundance and larval habitats characterization of mosquito species in Lagos State, Nigeria. Sci. Afr. 2020, 10, e00656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbanzulu, K.M.; Mboera, L.E.G.; Wumba, R.; Engbu, D.; Bojabwa, M.M.; Zanga, J.; Mitashi, P.M.; Misinzo, G.; Kimera, S.I. Physicochemical Characteristics of Aedes Mosquito Breeding Habitats in Suburban and Urban Areas of Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Front. Trop. Dis. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahgoub, M.M.; Kweka, E.J.; Himeidan, Y.E. Characterisation of larval habitats, species composition and factors associated with the seasonal abundance of mosquito fauna in Gezira, Sudan. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2017, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmuda A, Usman M. Preferred breeding sites of different mosquito species in Sokoto. 2011.

- Djossou DH, Djègbè I, Mensah K, Dabla A, Nonfodji OM. Diversity of larval habitats of Anopheles mosquitoes in urban areas of Benin and influence of their physicochemical and bacteriological characteristics on larval density. Parasit Vectors. 2022;1–17.

- WHO. World malaria World malaria report report [Internett]. Hentet fra: https://www.wipo.int/amc/en/mediation/%0Ahttps://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2023.

- Ebhodaghe, F.I.; Sanchez-Vargas, I.; Isaac, C.; Foy, B.D.; Hemming-Schroeder, E. Sibling species of the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae display divergent preferences for aquatic breeding sites in southern Nigeria. Malar. J. 2024, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahamba, N.F.; Finda, M.; Ngowo, H.S.; Msugupakulya, B.J.; Baldini, F.; Koekemoer, L.L.; Ferguson, H.M.; Okumu, F.O. Using ecological observations to improve malaria control in areas where Anopheles funestus is the dominant vector. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munga S, Minakawa N, Zhou G, Barrack OOJ, Githeko AK, Yan G. Effects of larval competitors and predators on oviposition site selection of Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto. J Med Entomol. 2006;43:221–4.

- Asigau, S.; Parker, P.G. The influence of ecological factors on mosquito abundance and occurrence in Galápagos. J. Vector Ecol. 2018, 43, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantaux, A.; Ouattarra, I.; Lefèvre, T.; Dabiré, K.R. Effects of larvicidal and larval nutritional stresses on Anopheles gambiae development, survival and competence for Plasmodium falciparum. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.; Takken, W.; Mccall, P.J. Interspecific competition between sibling species larvae of Anopheles arabiensis and An. gambiae. Med Veter- Èntomol. 2000, 14, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenraadt CJM, Majambere S, Hemerik L, Takken W. Cannibalism and predation among larvae of Anopheles gambiae s.l. Entomol Exp Appl. 2004;112:125–34.

- Koenraadt, C.J.M.; Takken, W. Cannibalism and predation among larvae of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Med Veter- Èntomol. 2003, 17, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muturi, E.J.; Kim, C.-H.; Jacob, B.; Murphy, S.; Novak, R.J. Interspecies Predation Between Anopheles gambiae s.s. and Culex quinquefasciatus Larvae. J. Med Èntomol. 2010, 47, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huxley, P.J.; Murray, K.A.; Pawar, S.; Cator, L.J. The effect of resource limitation on the temperature dependence of mosquito population fitness. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2021, 288, 20203217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabachnick, W.J. Nature, Nurture and Evolution of Intra-Species Variation in Mosquito Arbovirus Transmission Competence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounibos LP, Bargielowski I, Carrasquilla MC, Nishimura N. Coexistence of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Peninsular Florida Two Decades After Competitive Displacements. J Med Entomol. 2016;53:1385–90.

- Couret, J.; Dotson, E.; Benedict, M.Q. Temperature, Larval Diet, and Density Effects on Development Rate and Survival of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e87468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Luppi, T.; Spivak, E.D.; Anger, K. Experimental studies on predation and cannibalism of the settlers of Chasmagnathus granulata and Cyrtograpsus angulatus (Brachyura: Grapsidae). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2001, 265, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessen, D.; de Roos, A.M.; Persson, L. Population dynamic theory of size–dependent cannibalism. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2004, 271, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo KS, Muturi EJ, Lampman RL, Alto BW. The effects of resource type and ratio on competition with Aedes albopictus and Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2014;48:29–38.

- Marini, G.; Guzzetta, G.; Baldacchino, F.; Arnoldi, D.; Montarsi, F.; Capelli, G.; Rizzoli, A.; Merler, S.; Rosà, R. The effect of interspecific competition on the temporal dynamics of Aedes albopictus and Culex pipiens. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.V.; Drake, J.M.; Jones, L.; Murdock, C.C. Assessing temperature-dependent competition between two invasive mosquito species. Ecol. Appl. 2021, 31, e2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmamuthuraja, D.; D., R.P.; M., I.L.; Isvaran, K.; Ghosh, S.K.; Ishtiaq, F. Determinants of Aedes mosquito larval ecology in a heterogeneous urban environment- a longitudinal study in Bengaluru, India. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011702. [CrossRef]

- Fader, J.E.; Juliano, S.A. An empirical test of the aggregation model of coexistence and consequences for competing container-dwelling mosquitoes. Ecology 2013, 94, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrell, E.G.; Juliano, S.A. Predation resistance does not trade off with competitive ability in early-colonizing mosquitoes. Oecologia 2013, 173, 1033–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjana, T.; Tuno, N.; Higa, Y. Effects of temperature and diet on development and interspecies competition in Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Med Veter- Èntomol. 2012, 26, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefèvre, T.; Vantaux, A.; Dabiré, K.R.; Mouline, K.; Cohuet, A. Non-Genetic Determinants of Mosquito Competence for Malaria Parasites. PLOS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuno, N.; Farjana, T.; Uchida, Y.; Iyori, M.; Yoshida, S. Effects of Temperature and Nutrition during the Larval Period on Life History Traits in an Invasive Malaria Vector Anopheles stephensi. Insects 2023, 14, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alto, B.W.; Bettinardi, D. Temperature and Dengue Virus Infection in Mosquitoes: Independent Effects on the Immature and Adult Stages. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 88, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muturi EJ, Blackshear M, Montgomery A. Temperature and density-dependent effects of larval environment on Aedes aegypti competence for an alphavirus. J Vector Ecol. 2012;37:154–61.

- Alto BW, Lounibos LP. Vector competence for arboviruses in relation to the larval environment of mosquitoes. Ecol parasite-vector Interact. 2013;81–101.

- Alto BW, Lounibos LP, Mores CN, Reiskind MH. Larval competition alters susceptibility of adult Aedes mosquitoes to dengue infection. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2008;275:463–71.

- Ready PD, Rogers M. Ecology of parasite-vector interactions. Ecol. parasite-vector Interact. 2013.

- Nebbak, A.; Almeras, L.; Parola, P.; Bitam, I. Mosquito Vectors (Diptera: Culicidae) and Mosquito-Borne Diseases in North Africa. Insects 2022, 13, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, H.M.; Ng'Habi, K.R.; Walder, T.; Kadungula, D.; Moore, S.J.; Lyimo, I.; Russell, T.L.; Urassa, H.; Mshinda, H.; Killeen, G.F.; et al. Establishment of a large semi-field system for experimental study of African malaria vector ecology and control in Tanzania. Malar. J. 2008, 7, 158–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong’wen, F.; Onyango, P.O.; Bukhari, T. Direct and indirect effects of predation and parasitism on the Anopheles gambiae mosquito. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koella, JC. Relationship between body size of adult Anopheles gambiae s.l. and infection with the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology. 1992;104:233–7.

- Alomar, A.A.; Pérez-Ramos, D.W.; Kim, D.; Kendziorski, N.L.; Eastmond, B.H.; Alto, B.W.; Caragata, E.P. Native Wolbachia infection and larval competition stress shape fitness and West Nile virus infection in Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1138476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, V.R.; Alem, I.; De Majo, M.S.; Byttebier, B.; Solari, H.G.; Fischer, S. Effects of scarcity and excess of larval food on life history traits ofAedes aegypti(Diptera: Culicidae). J. Vector Ecol. 2018, 43, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, M.; Service, M.W.; Birley, M.H. Density-dependent regulation of Aedes cantans (Diptera: Culicidae) in natural and artificial populations. Ecol. Èntomol. 1993, 18, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyrisco GG, Sohi SS, Moore CG, Whitacre DM, Pioneering E. Competition in Mosqviitoes. Production of Aedes aegypti 1 Larval Growth Retardant at Various Densities and Nutrition Levels 2. 1972;915–8.

- Bédhomme, S.; Agnew, P.; Sidobre, C.; Michalakis, Y. Pollution by conspecifics as a component of intraspecific competition among Aedes aegypti larvae. Ecol. Èntomol. 2005, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widahl, L.-E. Flow Patterns around Suspension-Feeding Mosquito Larvae (Diptera: Culicidae). Ann. Èntomol. Soc. Am. 1992, 85, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho C, Ewert A, Chew L. Interspecific Competition Among Aedes aegypti, Ae. albopictus, and Ae. triseriatus ( Diptera : Culicidae ): Larval Development in Mixed Cultures. 1989;26:615–23.

- Paaijmans, K.P.; Huijben, S.; Githeko, A.K.; Takken, W. Competitive interactions between larvae of the malaria mosquitoes Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles gambiae under semi-field conditions in western Kenya. Acta Trop. 2009, 109, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, D.A.; Juliano, S.A. Consequences of detritus type in an aquatic microsystem: effects on water quality, micro-organisms and performance of the dominant consumer. Freshw. Biol. 2006, 51, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, R.C.; Haq, S.; Kumar, G. Interspecific competition between larval stages of Aedes aegypti and Anopheles stephensi. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2019, 56, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armistead JS, Arias JR, Nishimura N, Lounibos LP. Interspecific larval competition between Aedes albopictus and Aedes japonicus (Diptera: Culicidae) in northern Virginia. J Med Entomol. 2008;45:629–37.

- Pocock K. Interspecific competition between container sharing mosquito larvae, Aedes aegypti (L.), Aedes polynesiensis Marks, and Culex quinquefasciatus Say, in Moorea, French Polynesia. 2007;

- Murrell EG, Juliano SA. Detritus Type Alters the Outcome of Interspecific Competition Between Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus ( Diptera : Culicidae ). 2008;375–83.

- Juliano SA, Lounibos LP, O’Meara GF. A field test for competitive effects of Aedes albopictus on A. aegypti in South Florida: differences between sites of coexistence and exclusion? Oecologia. 2004;139:583–93.

- Juliano SA, Philip Lounibos L. Ecology of invasive mosquitoes: effects on resident species and on human health. Ecol Lett. 2005;8:558–74.

- Barrera, R. Competition and resistance to starvation in larvae of container-inhabiting Aedes mosquitoes. Ecol. Èntomol. 1996, 21, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisen, W.K.; Azra, K.; Mahmood, F. Anopheles Culicifacies (Diptera: Culicidae): Horizontal and Vertical Estimates of Immature Development and Survivorship in Rural Punjab Province, Pakistan1. J. Med Èntomol. 1982, 19, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, D.A.; Kesavaraju, B.; Juliano, S.A. Interspecific Differences in Feeding Behavior and Survival Under Food-Limited Conditions for Larval Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Ann. Èntomol. Soc. Am. 2004, 97, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wolfshaar, v.; Roos, d.; Persson; Hočevar, S.; Kuparinen, A.; Toscano, B.J.; Figel, A.S.; Rudolf, V.H.W.; Benkendorf, D.J.; Whiteman, H.H...; et al. Size-Dependent Interactions Inhibit Coexistence in Intraguild Predation Systems with Life-History Omnivory. Am. Nat. 2006, 168, 62. [CrossRef]

- Ng'Habi, K.R.; John, B.; Nkwengulila, G.; Knols, B.G.; Killeen, G.F.; Ferguson, H.M. Effect of larval crowding on mating competitiveness of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Malar. J. 2005, 4, 49–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.; Briegel, H. Reproductive physiology of Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles atroparvus. J. Vector. Ecol. 2005, 30, 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lyimo, E.O.; Takken, W. Effects of adult body size on fecundity and the pre-gravid rate of Anopheles gambiae females in Tanzania. Med Veter- Èntomol. 1993, 7, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takken, W.; Klowden, M.J.; Chambers, G.M. Articles: Effect of Body Size on Host Seeking and Blood Meal Utilization in Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto (Diptera: Culicidae): the Disadvantage of Being Small. J. Med Èntomol. 1998, 35, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochaska J, Benowitz N. HHS Public Access. Physiology & Behaviour. 2016;176:100–106.

- Suwanchaichinda C, Paskewitz SM. Effects of Larval Nutrition , Adult Body Size , and Adult Temperature on the Ability of Anopheles gambiae ( Diptera : Culicidae ) to Melanize Sephadex Beads. 1998.

- Juliano, S.A. Species Interactions Among Larval Mosquitoes: Context Dependence Across Habitat Gradients. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2009, 54, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinsen, WK; RW E. Cannibalism in Anopheles stephensi liston. 1976.

- Clements, A. The Biology of Mosquitoes, Volume 2: Sensory Reception and Behaviour; CABI Publishing: Oxon, United Kingdom, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Population | Species | Effects | RR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ae.aegypti & An.arabiensis | Ae.aegypti | Competition | Intraspecific Interspecific |

1 0.40 (0.30, 0.55) |

<0.001 |

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 0.88 (0.66, 1.16) |

0.359 |

||

| An.arabiensis | Competition | Intraspecific Interspecific |

1 0.23 (0.15, 0 .35) |

<0.001 |

|

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 0.84 (0.56, 1.29) |

0.441 |

||

| Ae.aegypti & An.gambiae | Ae.aegypti | Competition |

Intraspecific Interspecific |

1 0.50 (0.34, 0.74) |

0.001 |

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 0.89 (0.63, 1.27) |

0.55 |

||

| An.gambiae | Competition | Intraspecific Interspecific |

1 0.43 (0.26, 0.71) |

0.001 |

|

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 0.82 (0.52, 1.28) |

0.393 |

||

| Ae.aegypti & An.funestus | Ae.aegypti | Competition | Intraspecific Interspecific |

1 0.26 (0.17, 0.39) |

<0.001 |

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 0.65 (0.45, 0.94) |

0.901 |

||

| An.funestus | Competition | Intraspecific Interspecific |

1 0.19 (0.13, 0.28) |

<0.001 |

|

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 1.02 (0.69, 1.52) |

0.024 |

||

| Population | Species | Effects | RR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ae.aegypti & An.arabiensis | Ae.aegypti | Competition | Alone Mixed |

1 0.76 (0.72, 0 .80) |

<0.001 |

|

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 1.16 (1.09, 1.22) |

<0.001 |

|||

| Competition× Habitat | Mixed ×Medium |

1.21 (1.11, 1.31) |

<0.001 |

|||

| An.arabiensis | Competition | Alone Mixed |

1 0.47 (0.44, 0.50) |

<0.001 |

||

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 1.13 (1.08, 1.19) |

<0.001 |

|||

| Competition ×Habitat | Mixed ×Medium |

1.61 (1.48, 1.74) |

<0.001 |

|||

| Ae.aegypti & An.gambiae | Ae.aegypti | Competition | Alone Mixed |

1 0.80 (0.76, 0.84) |

<0.001 |

|

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 0.20 (1.15, 1.26) |

<0.001 |

|||

| Competition× Habitat | Mixed ×Medium |

1.04 (0.98, 1.12) |

0.196 |

|||

| An.gambiae | Competition | Alone Mixed |

1 0.56 (0.54, 0.58) |

<0.001 |

||

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 1.09 (1.04, 1.14) |

<0.001 |

|||

| Competition× Habitat | Mixed ×Medium |

0.29 (0.21, 1.37) |

<0.001 |

|||

| Ae.aegypti & An.funestus | Ae.aegypti | Competition | Alone Mixed |

1 0.77 (0.73, 0.82) |

<0.001 |

|

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 1.22 (1.17, 1.29) |

<0.001 |

|||

| Competition× Habitat | Mixed ×Medium |

1.13 (1.05, 1.22) |

0.001 |

|||

| An.funestus | Competition | Alone Mixed |

1 0.58 (0.56, 0.60) |

<0.001 |

||

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 1.18 (1.14, 1.22) |

<0.001 |

|||

| Competition× Habitat | Mixed ×Medium |

0.28 (1.21, 1.35) |

<0.001 |

|||

| Population | Species | Effects | RR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ae.aegypti & An.arabiensis | Ae.aegypti | Competition | Alone Mixed |

1 0.54 (0.38, 0 .79) |

0.001 |

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 1.15 (0.82, 1.62) |

0.423 |

||

| Food | No Yes |

1 0.001 (0.0001, 0 .005) |

<0.001 |

||

| An.arabiensis | Competition | Alone Mixed |

1 8.24 (4.91, 13.83) |

<0.001 |

|

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 1.28 (0.79, 2.06) |

0.303 |

||

| Food | No Yes |

1 0.13 (0.07, 0 .21) |

<0.001 |

||

| Ae.aegypti & An.gambiae | Ae.aegypti | Competition | Alone Mixed |

1 0.49 (0.36, 0.66) |

<0.001 |

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 0.86 (0.64, 1.16) |

0.326 |

||

| Food | No Yes |

1 0.02 (0.01, 0 .03) |

<0.001 |

||

| An.gambiae | Competition | Alone Mixed |

1 6.35 (4.34, 9.29) |

<0.001 |

|

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 1.16 (0.83, 1.63) |

0.386 |

||

| Food | No Yes |

1 0.16 (0.11, 0.24) |

<0.001 |

||

| Ae.aegypti & An.funestus | Ae.aegypti | Competition | Alone Mixed |

1 0.71 (0.49, 1.03) |

0.07 |

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 0.98 (0.67, 1.45) |

0.942 |

||

| Food | No Yes |

1 0.01 (0.003, 0.013) |

<0.001 |

||

| An.funestus | Competition | Alone Mixed |

1 14.09 (8.55, 23.22) |

<0.001 |

|

| Habitat | Small Medium |

1 1.99 (1.27, 3.11) |

0.002 |

||

| Food | No Yes |

1 0.26 (0.16, 0.42) |

<0.001 |

||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).