Submitted:

16 October 2024

Posted:

16 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Plant Materials

2.2. Sandwich Method

2.3. Plant Box Method

2.4. Gas Chromatography – Mass Spectrometry

2.5. Aqueous Extract Preparation

2.6. Pot Experiment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

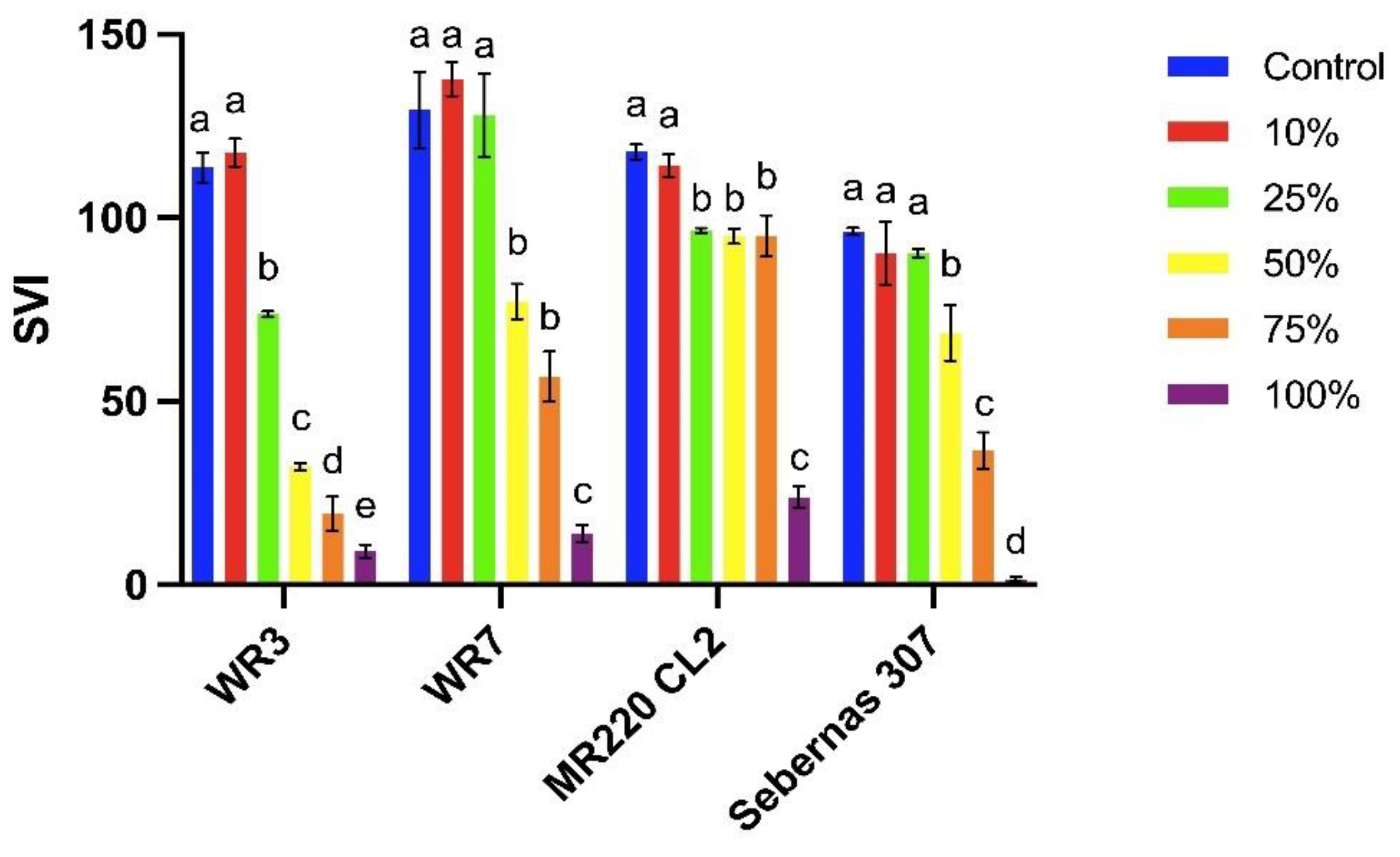

3.1. Allelopathic Potential of T. procumbens Foliar Leachate

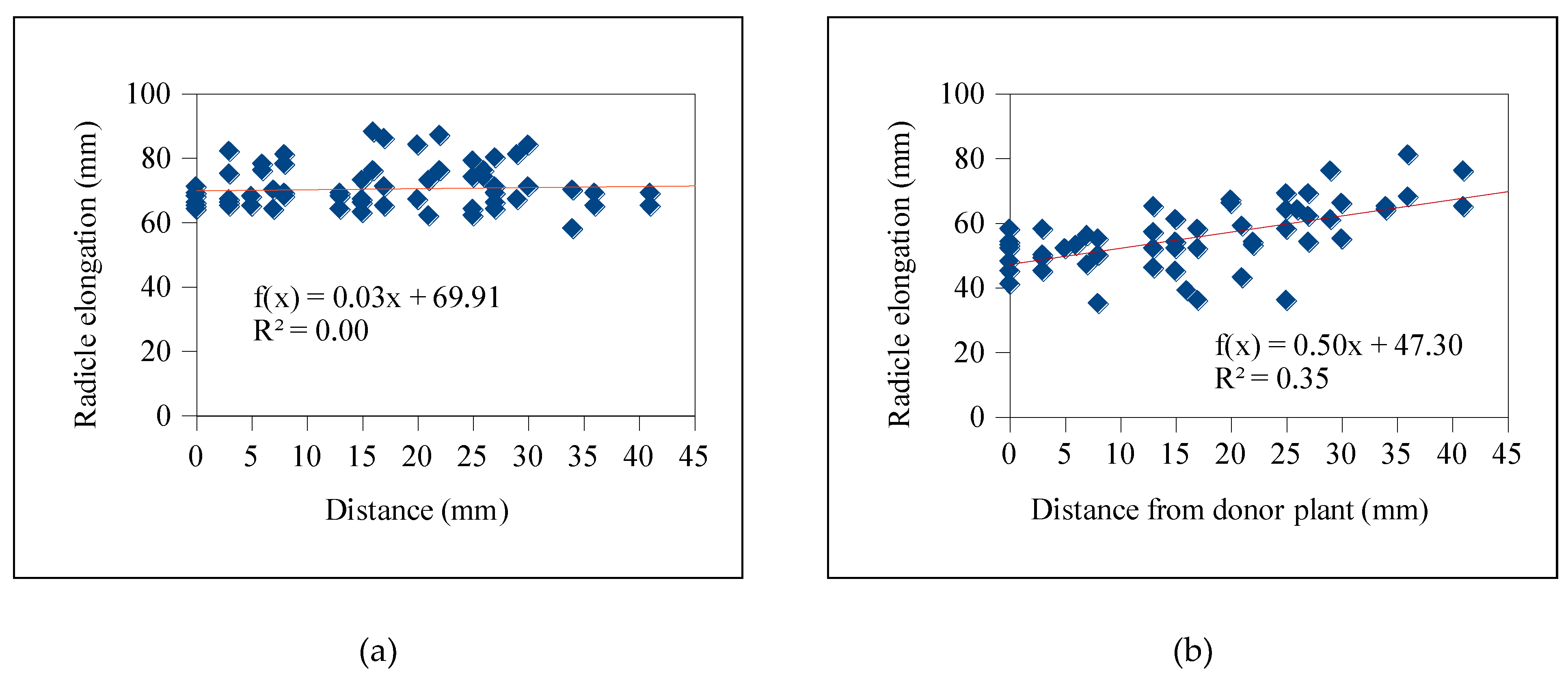

3.2. Allelopathic Potential of T. procumbens Root Exudates

3.3. Allelochemicals Presence in T. procumbens Leaves

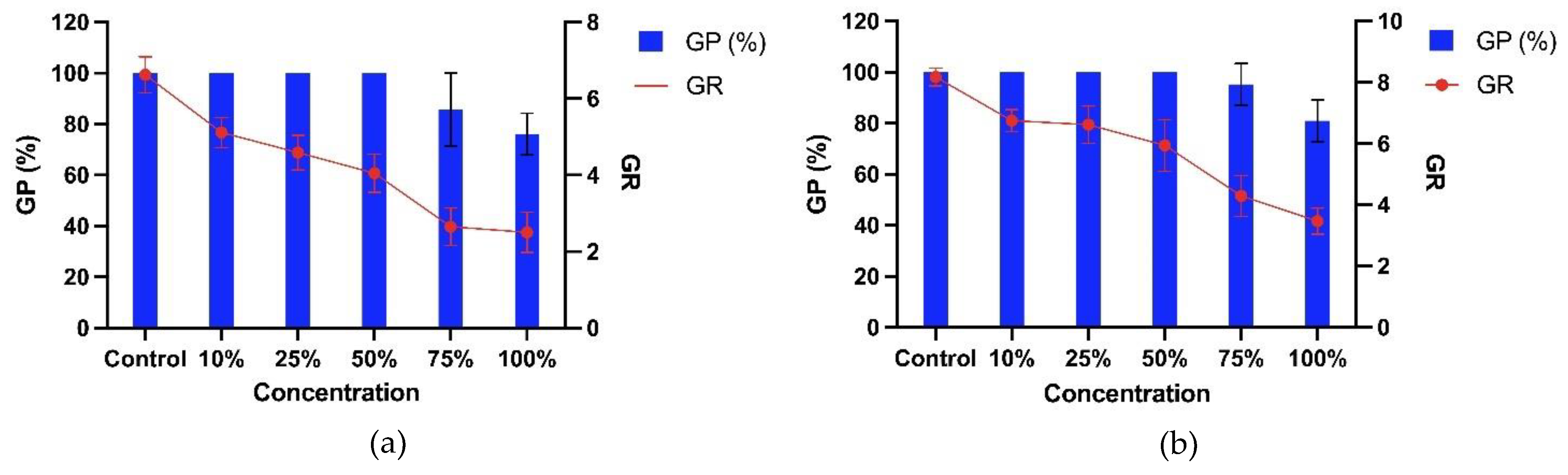

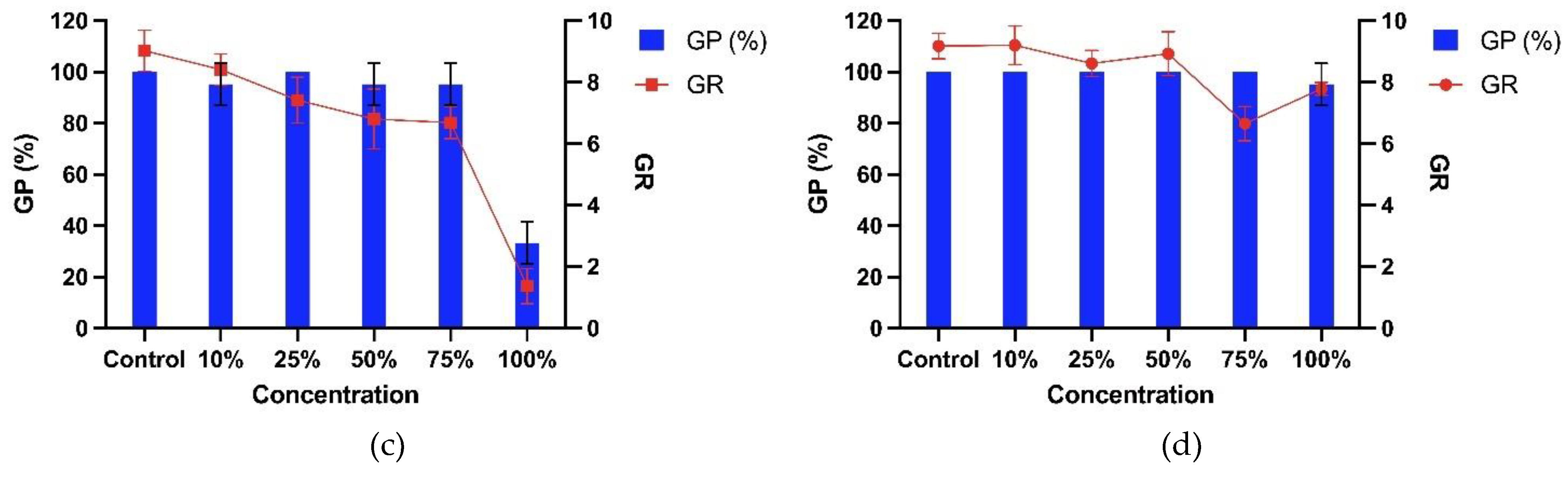

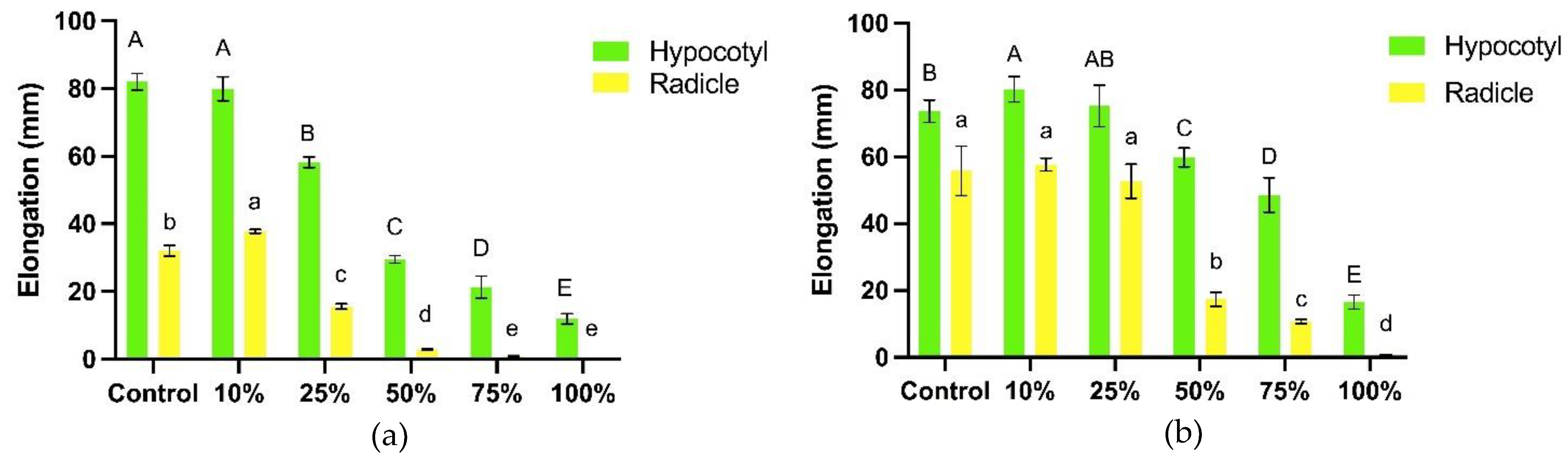

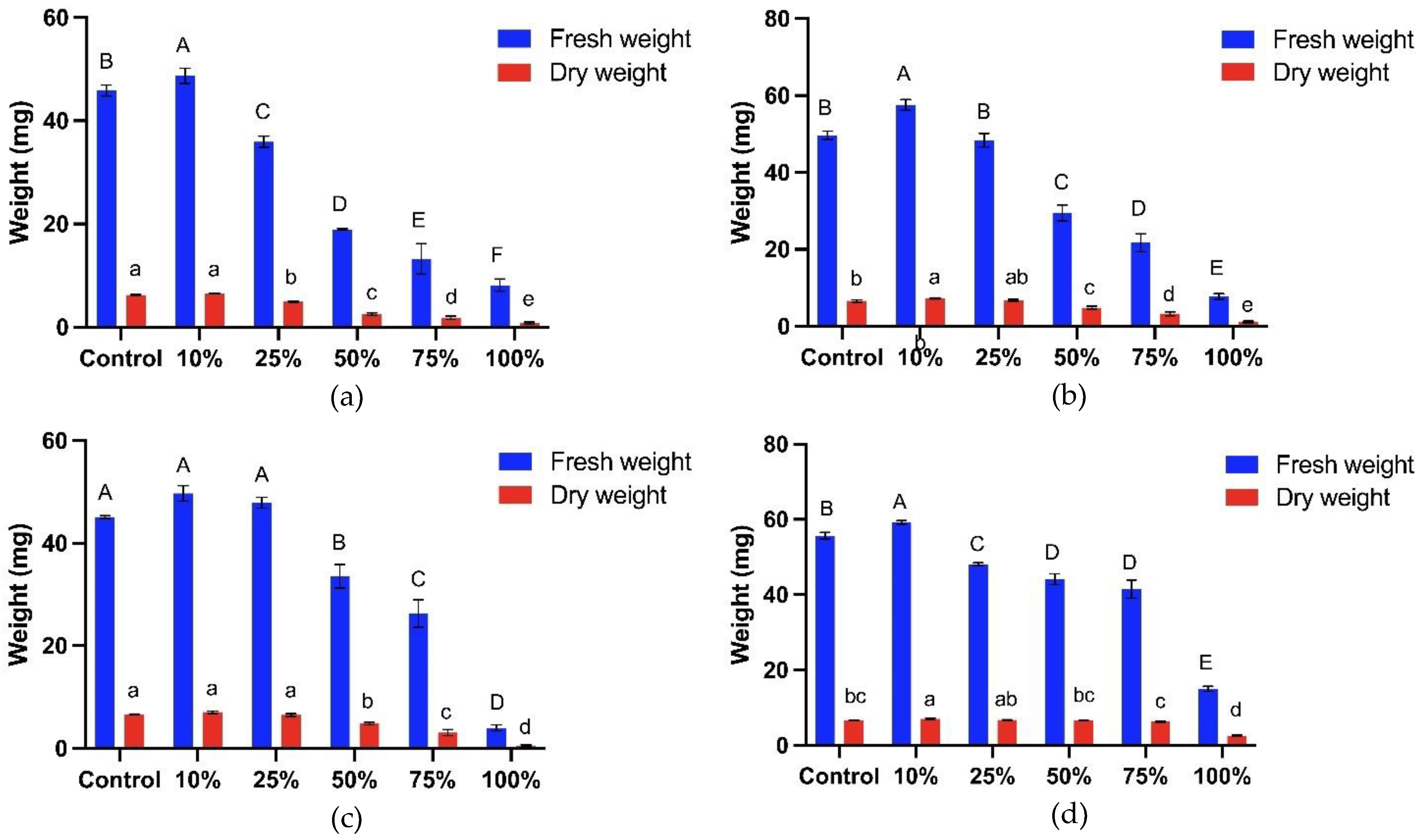

3.4. Allelopathic Influzences of T. procumbens Leaf Aqueous Extract

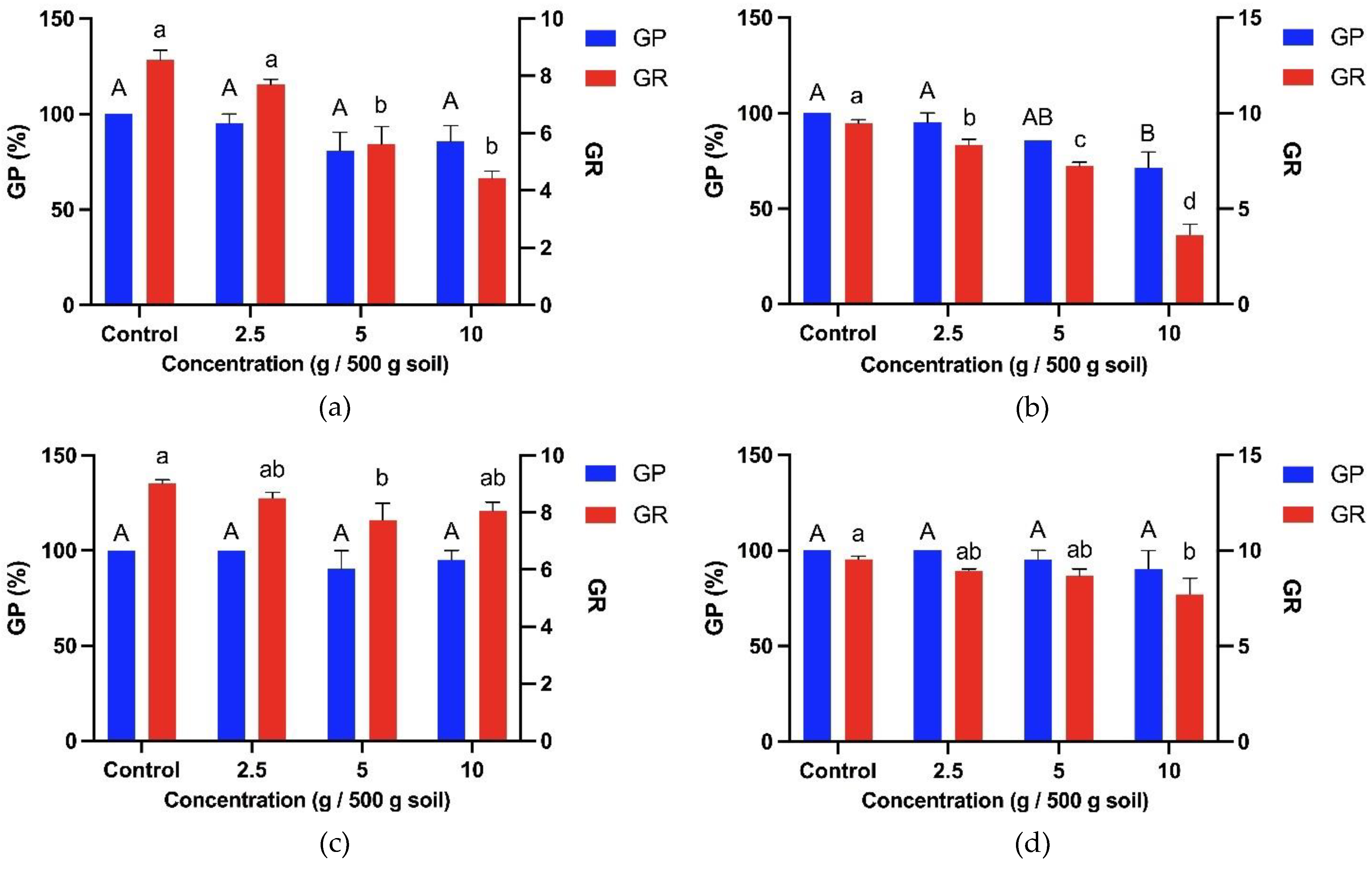

- A Germination

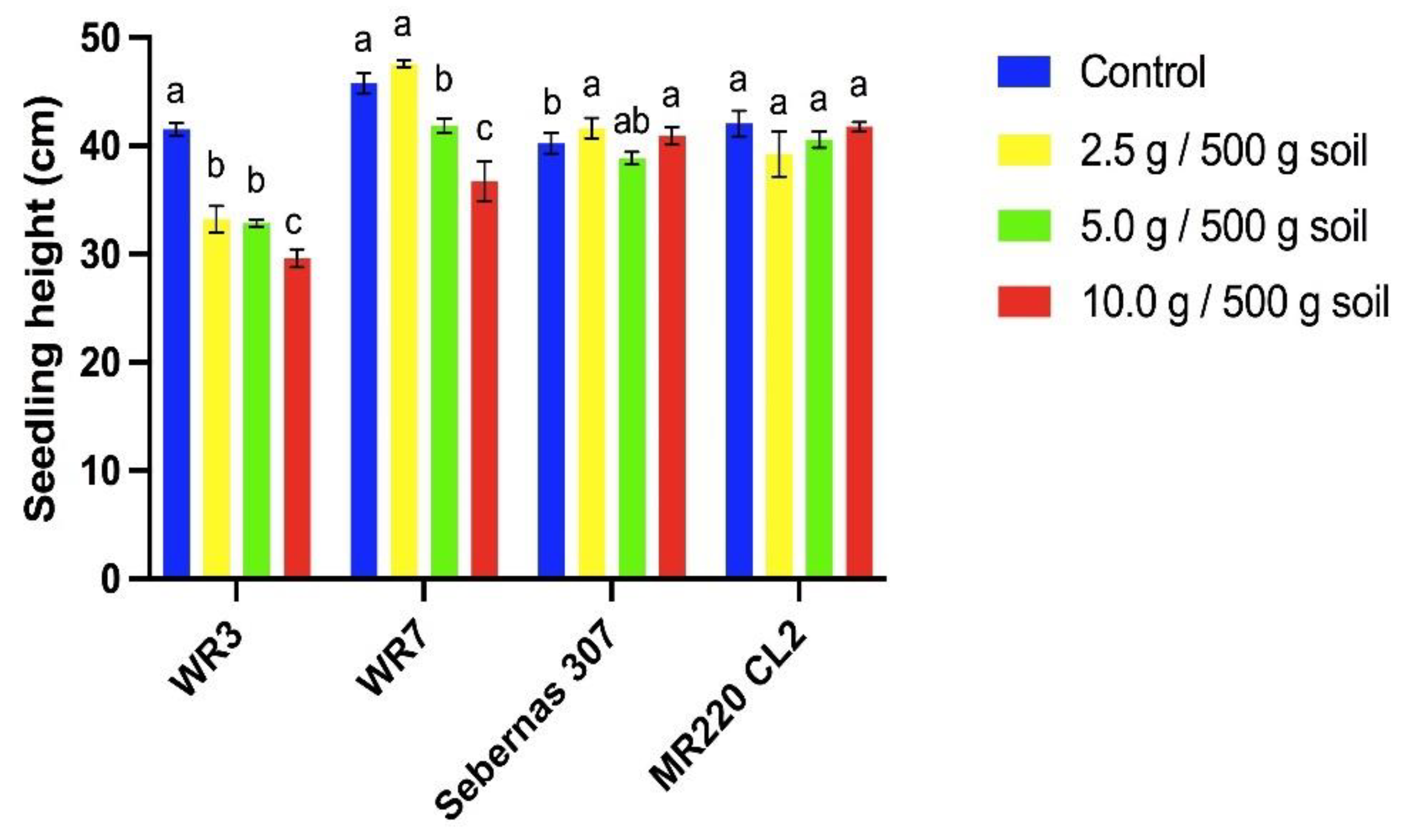

- B Seedling growth

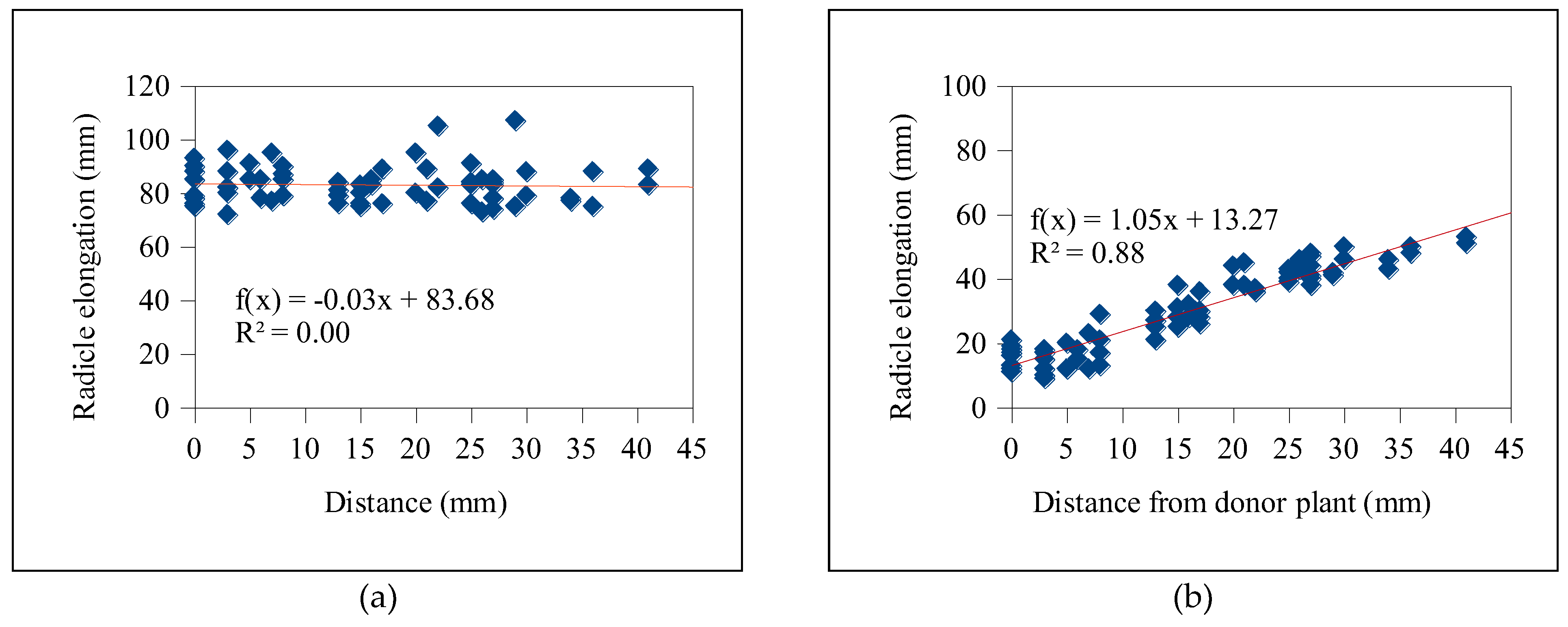

3.5. Allelopathic Influences of T. procumbens Leaf Debris

- A Germination

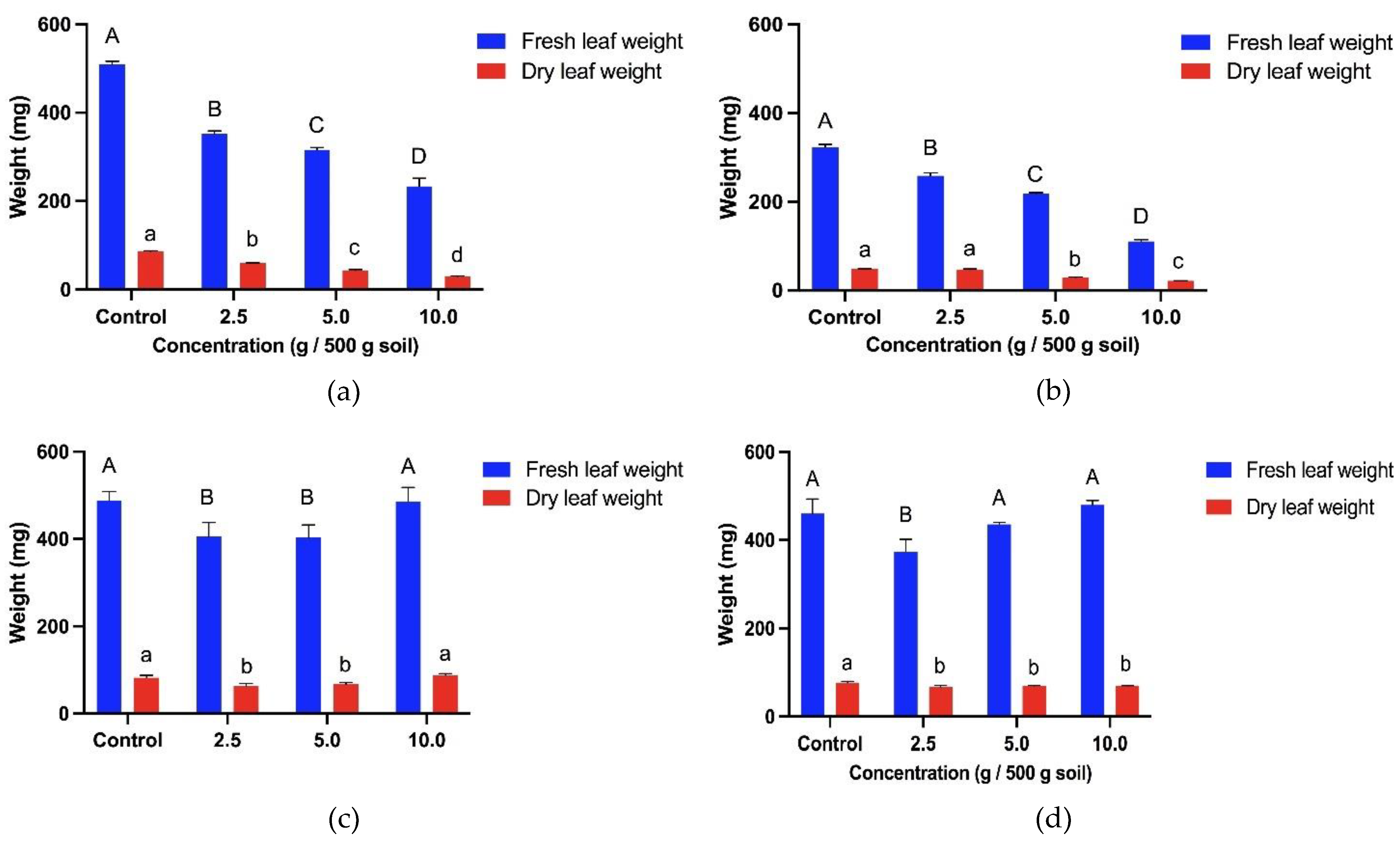

- B Seedling growth

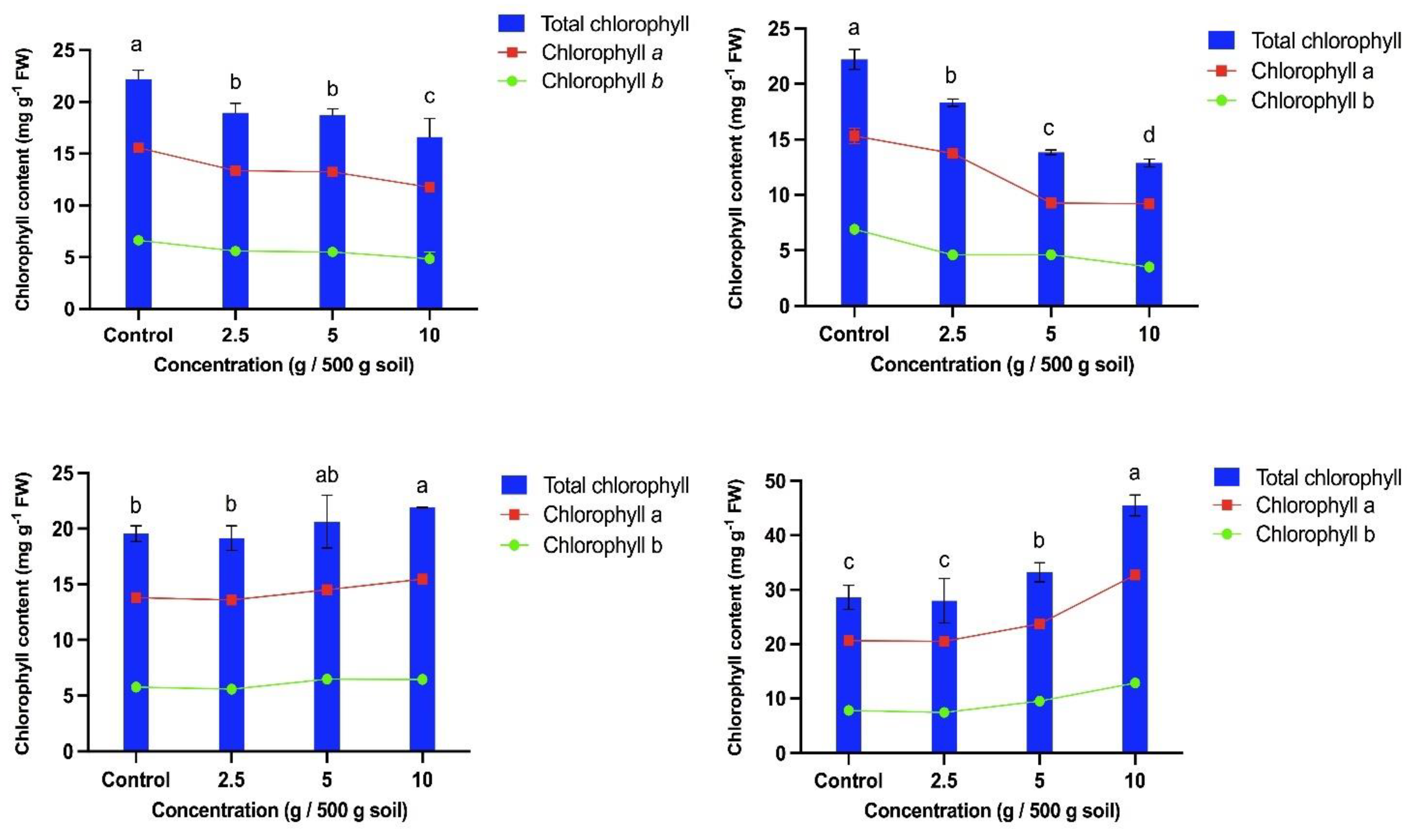

- C Chlorophyll content

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, K.; Kumar, V.; Saharawat, Y.; Gathala, M. Weedy rice: An emerging threat for direct-seeded rice production systems in India. Journal of Rice Research, 2013; 1, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sudianto, E.; Neik, T.-X.; Tam, S.M.; Chuah, T-S.; Idris, A.A.; Olsen, K.M.; Song, B-K. Morphology of Malaysian weedy rice (Oryza sativa): Diversity, origin and implications for weed management. Weed Science 2016, 64, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.P.M.D.; Azmi, M.; Othman, A.S. Morphological study of the relationships between weedy rice accessions (Oryza sativa complex) and commercial rice varieties in Pulau Pinang rice granary area. Tropical Life Sciences Research 2010, 21, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karim, R.S.M.; Zainal, M.; Mansor, M.; Azmi, M. Weedy rice: a cancerous threat for rice growers in Malaysia. In. Proceedings of the National Rice Conference 2010. Perak, Malaysia: Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute, 2010; pp. 327–329.

- Azmi, M.; Watanabe, H.; Abdullah, M.Z.; Zainal, A.H. Padi angin, an emerging threat to direct-seeded rice. In. Proceedings of the Malaysian Congress of Science and Technology, Kuala Lumpur. Confederation of Scientific and Technological Association in Malaysia, 1994.

- Ziska, L.H.; Gealy, D.R.; Burgos, N.; Caicedo, A.L.; Gressel, J.; Lawton-Rauh, A.L.; Avila, L.A.; Theisen, G.; Norsworthy, J.; Ferrero, A.; Vidotto, F. 2015. Weedy (red) rice: an emerging constraint to global rice production. Advances in Agronomy. 2015, 129, 181–228. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, S.; Stallworth, S. ; Tseng, T-M. 2018. Weedy rice: Competitive ability, evolution and diversity [Online First]. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/weedy-rice-competitive-ability-evolution-and-diversity (accessed on 29 November 2018).

- Azmi, M.; Abdullah, M.Z.; Muhammad, H. Pengenalan dan Kawalan Padi Angin di Malaysia. Serdang: MARDI Publication, 2001.

- Nakayama, S.; Ghani, R.A.; Azmi, M. Chemical control and a case study on some ecological characteristics. In. Ecology of major weeds and their control in direct seeded rice culture of Malaysia.Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI): Penang, 1996; pp. 98–105. P.

- Watanabe, H.; Vaughan, D.A.; Tomooka, N. 2000. Weedy rice complexes: case studies from Malaysia, Vietnam, and Surinam. In. Baki, B.B. et al. (eds.). Wild and Weedy Rice in Rice Ecosystems in Asia: A Review. IRRI: Philippines, 2000; pp. 25.

- Saharan, H.A. Rice Weed Control in Malaysia. MARDI Report No. 66. MARDI: Serdang, 1979.

- Estorninos Jr., L. E.; Gealy, D.R.; Talbert, R.E.; Gbur, E.E. Rice and red rice interference. Response of red rice (Oryza sativa) to sowing rates of tropical japonica and indica rice cultivars. Weed Science 2005, 53, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, B.S. Strategies to manage weedy rice in Asia. Crop Protection 2013, 48, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilipkumar, M.; Burgos, N.R.; Chuah, T.S.; Ismail, S. Cross-resistance to imazapic and imazapyr in a weedy rice (Oryza sativa) biotype found in Malaysia. Planta Daninha. 2018, 36, e018182239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, E.L. Allelopathy, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: New York, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H.P.; Batish, D.R.; Kohli, R.K. Allelopathy in agroecosystems: An overview. Journal of Crop Production 2001, 4920, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Kulsoom, M.I.; Khan, R.; Khan, S.A. Screening the allelopathic potential of various weeds. Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research 2011, 17, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Nornasuha, Y.; Ismail, B.S. Sustainable weed management using allelopathic approach. Malaysian Applied Biology 2017, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, J.N.; Ghatak, A.; Singh, A.K. Allelopathy: How plants suppress other plants. Rashtriya Krishi 2017, 12, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, S.O.; Lydon, J. Herbicides from natural compounds. Weed Technology 1987, 1, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, F.A.; Marin, D.; Oliveros-Bastidas, A.; Castellano, D.; Simonet, A.M.; Molinillo, J.M.G. Structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies of benzoxazinones, their degradation products, and analogues. Phytotoxicity on problematic weeds Avena fatua L. and Lolium rigidum Gaud. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2006, 54, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, D.E.; Chan, L.G. Common Weeds of Malaysia and Their Control. Ancom Berhad: Kuala Lumpur, 1990.

- Holm, L.; Plucknett, D.; Pancho, J.; Herberger, J. The World's Worst Weeds: Distribution and Biology. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1977.

- Holm, L.; Pancho, J.V.; Herberger, J.P.; Plucknett, D.L. A Geographical Atlas of World Weeds. Wiley and Sons Inc: New York, 1979.

- Andriana, Y.; Xuan, T.D.; Quan, N.V.; Quy, T.N. Allelopathic potential of Tridax procumbens L. on radish and identification of allelochemicals. Allelopathy Journal 2018, 43, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femina, D.; Lakshmipriya, P.; Subha, S.; Manonmani, R. Allelopathic effect of the weed (Tridax procumbens L.) on seed germination and seedling growth of some leguminous plants. International Research Journal of Pharmacy 2012, 3, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, R.S.M.; Man, A.B.; Sahid, I.B. Weed problems and their management in rice fields of Malaysia: an overview. Weed Biology and Management 2004, 4, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Parvez, S.; Parvez, M.M.; Ohmae, Y.; Iida, O. Screening of 239 medicinal plant species for allelopathic activity using the sandwich method. Weed Biology and Management 2003, 3, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardani, H.; Kazantseva, E.; Onipchenko, V.; Fujii, Y. Evaluation of allelopathic activity of 178 Caucassian plant species. International Journal of Basic and Applied Science 2016, 5, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Pariasca, D.; Shibuya, T.; Yasuda, T.; Kahn, B.; Waller, G.R. Plant-box method: a specific bioassay to evaluate allelopathy through root exudates. In. Fujii, Y.; Hiradate, S. (eds.). Allelopathy: New Concepts and Methodology. Science Publishers: Enfield, 2007.

- Kushwaha, P.; Yadav, S.S.; Singh, V.; Dwivedi, L.K. Phytochemical screening and GC-MS studies of the methanolic extract of Tridax procumbens. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 2019, 10, 2492–2496. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, T.; Khalid, S.; Saeed, M.; Mazhar, R.; Qureshi, H.; Rashid, M. Allelopathic interference of leaf powder and aqueous extracts of hostile weed: Parthenium hysterophorus (Asteraceae). Science International 2016, 4, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurul Ain, M.B.; Nornasuha, Y.; Ismail, B.S. Allelopathic assessment of selected common weeds in Malaysia. AIP Conference Proceedings 2016, 1784, 060039. [Google Scholar]

- Popoola, K.M.; Akinwale, R.O.; Adelusi, A.A. Allelopathic effect of extracts from selected weeds on germination and seedling growth of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) varieties. African Journal of Plant Science 2020, 14, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, N.M.; Centurion, M.A.P.D.C.; Alves, P.L.D.C.A. Influência de extratos aquosos de sorgo sobre a germinação e o desenvolvimento de plântulas de soja. Ciência Rural 2005, 35, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, C.I.O.; Miyaura, R.; Tapia Y Figueroa, M.D.L.; Rengifo Salgado, E.L.; Fujii, Y. Screening of 170 Peruvian plant species for allelopathic activity by using the Sandwich Method. Weed Biology and Management 2012, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, T.; Nakahata, Y.; Kato-Noguchi, H. Allelopathic activity of some herb plant species. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology 2013, 15, 1359–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi, S.; Watanabe, I.; Kuno, K.; Fujii, Y. Allelopathic activity of leaching from dry leaves and exudate from roots of ground cover plants assayed on agar. Weed Biology and Management 2002, 2, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moujahid, L.; Le Roux, X.; Michalet, S.; Bellvert, F.; Weigelt, A.; Poly, F. Effect of plant diversity on the diversity of soil organic compounds. PloS One 2017, 12, e0170494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.R.; Li, X.; Won, O.J.; Park, S.U.; Pyon, J.Y. Herbicidal activity of phenolic compounds from hairy root cultures of Fagopyrum tataricum. Weed Research 2011, 52, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierziak, J.; Kostyn, K.; Kulma, A. Flavonoids as important molecules of plant interactions with the environment. Molecules 2014, 19, 16240–16265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, P.G.; George, S. Allelopathic effect of greater club rush on rice and weedy rice. Trends in Biosciences 2017, 10, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahari, S.; Miransari, M. Allelopathic effects of rice cultivars on the growth parameters of different rice cultivars. International Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 3, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, G. P,; Vinita, H,; Audiseshamma, K.; Paramageetham, C. Allelopathic effects of some weeds on germination and growth of Vigna mungo (L). Hepper. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci 2014, 3, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Mubeen, K.; Nadeem, M.A.; Tanveer, A.; Zahir, Z.A. Allelopathic effect of aqueous extracts of weeds on the germination and seedling growth of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Pakistan Journal of Life and Social Sciences. 2011, 9, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, A.; Tanveer, A.; Nadeem, M.A.; Zahir, Z.A. Comparative allelopathic potential of metabolites of two Alternanthera species against germination and seedling growth of rice. Planta Daninha 2014, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.; Joshi, A. Allelopathic effects of weed extracts on germination of wheat. Annals of Plant Sciences 2016, 5, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MADA. Rice R&D @ MARDI. 2019. Available online: http://www.mada.gov.my/wp- content/uploads/2019/09/lawatan-delegasi-filipina2-edited-140119-1.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Krishna, A.; Ramana, P.; Talekar, M. Allelopathic effect of weed extracts on seed germination of paddy cultivars. Karnataka Journal of Agricultural Science 2006, 20, 671–673. [Google Scholar]

- Ilori, O.J.; Otusanya, O.O.; Adelusi, A.A.; Sanni, R.O. Allelopathic activities of some weeds in the Asteraceae family. International Journal of Botany 2010, 6, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, N.; Tamotsu, S.; Nagata, N.; Saito, C.; Sakai, A. Allelopathic effects of volatile monoterpenoids produced by Salvia leucophylla: inhibition of cell proliferation and DNA synthesis in the root apical meristem of Brassica campestris seedlings. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2005, 31, 1187–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietjens, I.M.; Alink, G.M. Nutrition and health-toxic substances in food. Ned. Tijdschr Geneeskd 2003, 147, 2365–2370. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, A.; Devkota, A. Allelopathic effects of aqueous extract of leaves of Mikania micrantha HBK on seed germination and seedling growth of Oryza sativa L. and Raphanus sativus L. Scientific World 2013, 11, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodzadeh, H.; Mahmoodzadeh, M. Allelopathic effects of Cynodon dactylon L. on germination and growth of Triticum aestivum. Annals of Biological Research 2013, 5, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Khaliq, A.; Matloob, A.; Khan, M.B.; Tanveer, A. Differential suppression of rice weeds by allelopathic plant aqueous extracts. Planta Daninha 2013, 31, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Rao, P.B. Allelopathic effect of four weed species extracts on germination, growth and protein in different varieties of Glycine max (L.) Merrill. Journal of Environmental Biology 2006, 27, 571–577. [Google Scholar]

- Macías, F.A.; Galindo, J.C.G.; Massanet, G.M. Potential allelopathic activity of several sesquiterpene lactone models. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 1969–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, R.; Serin, T.; A. Man. Economic evaluation of Clearfield® Paddy Production System. Economic and Technology Management Review 2013, 8, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ruzmi, R.; Ahmad-Hamdani, M.S.; Abidin, M.Z.Z.; Burgos, N.R. Evolution of imidazolinone-resistant weedy rice in Malaysia: The current status. Weed Science 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, R.; Thakur, M.; Paul, Y.S. Antifungal activity of the essential oils of Chromolaena adenophorum, Ageratum conyzoides and Lantana camara. Indian Phytopathology 2012, 65, 409–411. [Google Scholar]

- Usuah, P.E.; Udom, G.N.; Edem, I.D. Allelopathic effect of some weeds on the germination of seeds of selected crops grown in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. World Journal of Agricultural Research 2013, 1, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Fatunbi, A.O.; Dube, S.; Yakubu, M.T.; Tshabalala, T. Allelopathic potential of Acacia mearnsii De wild. World Applied Sciences Journal 2009, 7, 1488–1493. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, M.; Salam, M.A.; Zaman, F. Allelopathic effect of siam weed debris on seed germination and seedling growth of three test crop species. Acta Scientifica Malaysia (ASM) 2021, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koodkaew, I.; Rottasa, R. Allelopathic effects of giant sensitive plant (Mimosa pigra) leaf powder on germination and growth of popping pod and purslane. International Journal of Agricultural Biology 2017, 18, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, B.S.; Tan, P.W.; Chuah, T.S. Assessment of the potential allelopathic effects of Pennisetum purpureum Schumach. on the germination and growth of Eleusine indica (L.) gaertn. Sains Malaysiana 2015, 44, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, B.S.; Kumar, A. Effects of aqueous extracts and residues decomposition of Mikania micrantha H.B.K. on selected crops. Allelopathy Journal 1996, 3, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.; Jabran, K.; Cheema, Z.A.; Wahid, A.; Siddique, K.H. The role of allelopathy in agricultural pest management. Pest Management Science 2011, 67, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.; Bajwa, A.A.; Cheema, S.A.; Cheema, Z.A. Application of allelopathy in crop production. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology 2013, 15, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, S.E.; Mutwali, E.M. Allelopathic effect of Datura stramonium on germination and some growth parameters of swiss chard (Beta vulgaris var. cicla). International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology 2018, 3, 726–730. [Google Scholar]

- Hegab, M.M.; Gabr, M.A.; Al-Wakeel, S.A.M.; Hamed, B.A. Allelopathic potential of Eucalyptus rostrata leaf residue on some metabolic activities of Zea mays L. Universal Journal of Plant Science 2016, 4, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Siddique, M.A.B.; Ismail, B.S. Allelopathic effects of Fimbristylis miliacea on the physiological activities of five Malaysian rice varieties. Australian Journal of Crop Science 2013, 7, 2062–2067. [Google Scholar]

- Bottery, B.R.; Bozzell, R.I. 1977 The relationship between chlorophyll content and rate of photosynthesis in soybean. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 1977, 57, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.L.; Jing, R.L.; Chang, X.P.; Li, W. Quantitative trait loci mapping for chlorophyll fluorescence and associated traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum). Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2007, 49, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.I.; Reigosa, M.J. A chlorophyll fluorescence analysis of photosynthetic efficiency, quantum yield and photon energy dissipation in PSII antennae of Lactuca sativa L. leaves exposed to cinnamic acid. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2011, 49, 1290–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilori, O.J.; Otusanya, O.O. Changes in chlorophyll and protein contents of Vigna unguiculata, Glycine max, Zea mays and Sorghum bicolor raised in soil incorporated with the shoots of Tithonia rotundifolia. Journal of Advances in Biology & Biotechnology 2020, 23, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, R. Handbook of Pesticide Toxicology: Principles and Agents. Academic Press: Oxford, 2001.

| Designation | Rice type | Sampling location | Coordinates | Morphological characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WR2 | Weedy variant | Kg. Sawah Sempadan | 3.453°N 101.214°E | Awnless; straw-hulled; open panicle |

| WR3 | Weedy variant | Kg. Pasir Panjang | 3.567°N 101.067°E | Awnless; straw-hulled; closed panicle |

| WR4 | Weedy variant | Telok Mesira, Bachok. | 6.143°N 102.343°E | Awnless; brown-hulled; open panicle |

| WR5 | Weedy variant | Jln. Tanjong, Tawang, Bachok | 6.102°N 102.321°E | Awless; brown-hulled; closed panicle |

| WR6 | Weedy variant | Kg. Tok Ajam, Pasir Puteh | 5.9038°N 102.374°E | Awned; straw-hulled; open panicle |

| WR7 | Weedy variant | Kg. Titi Serong, Parit Buntar | 5.099°N 100.471°E | Awned; brown-hulled; closed panicle |

| MR 220 CL2 | Modern cultivar | Gene and Seed Bank Center, MARDI Seberang Perai | - | - |

| Sebernas 307 | Modern cultivar | Gene and Seed Bank Center, MARDI Seberang Perai | - | - |

| MR 297 | Modern cultivar | Gene and Seed Bank Center, MARDI Seberang Perai | - | - |

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Model | DB-5MS-UI |

| Column length (m) | 30 |

| Diameter (mm) | 0.25 |

| Stationary phase | 5% phenyl methylpolysiloxane |

| Film width (µm) | 0.25 |

| Company | Agilent Technologies |

| Rice type | Bioassay | Radicle inhibition percentage (%) | Mean inhibition percentage (%) | Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 mg | 50 mg | ||||

| Weedy rice | WR2 | 30.93 ab | 93.24 a | 62.09 | 2 |

| WR3 | 36.09 a | 97.31 a | 66.70 | 1 | |

| WR4 | 29.68 ab | 76.65 b | 53.17 | 4 | |

| WR5 | 26.29 bc | 91.63 a | 58.96 | 3 | |

| WR6 | 9.58 de | 94.67 a | 52.13 | 5 | |

| WR7 | 6.89 e | 53.57 d | 30.23 | 7 | |

| Modern cultivars |

MR220 CL2 | 8.67 de | 25.43 e | 17.05 | 9 |

| Sebernas 307 | 14.17 cde | 27.34 e | 20.76 | 8 | |

| MR297 | 21.34 bcd | 64.68 c | 43.01 | 6 | |

| Rice type | Bioassay | Hypocotyl inhibition percentage (%) | Mean inhibition percentage (%) | Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 mg | 50 mg | ||||

| Weedy rice | WR2 | 19.83 a | 33.10 bc | 26.47 | 4 |

| WR3 | 18.93 a | 61.44 a | 40.19 | 1 | |

| WR4 | 19.83 bc | 33.10 bc | 26.47 | 3 | |

| WR5 | 8.87 ab | 22.75 cd | 15.81 | 6 | |

| WR6 | 10.76 a | 61.02 a | 35.89 | 2 | |

| WR7 | 13.01 a | 22.22 cd | 17.62 | 5 | |

| Modern cultivars |

MR220 CL2 | 14.16 a | 12.43 de | 13.30 | 7 |

| Sebernas 307 | -9.55 c | -5.20 f | -7.38 | 9 | |

| MR297 | -9.89 c | 5.37 ef | -2.26 | 8 | |

| Bioassay | Radicle elongation(mm) | Radicle elongation (%) | Correlation Pearson | Correlation coefficient, R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Exudates | ||||

| WR2 | 65.8 ± 0.46 | 29.0 ± 1.50 | 44.1 ** | 0.80 ** | 0.64 |

| WR3 | 82.8 ± 0.91 | 30.5 ± 1.60 | 36.8 ** | 0.94 ** | 0.88 |

| WR4 | 82.9 ± 0.83 | 56.3 ± 2.16 | 67.9 ** | 0.88 ** | 0.78 |

| WR5 | 73.9 ± 0.47 | 46.4 ± 2.14 | 62.8 ** | 0.93 ** | 0.87 |

| WR6 | 85.0 ± 0.78 | 41.7 ± 3.07 | 49.1 ** | 0.94 ** | 0.86 |

| WR7 | 68.8 ± 0.54 | 42.9 ± 2.20 | 62.3 ** | 0.90 ** | 0.81 |

| MR220 CL2 | 70.5 ± 0.85 | 55.7 ± 1.17 | 79.2 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.35 |

| MR297 | 69.3 ± 0.58 | 44.8 ± 1.82 | 64.8 ** | 0.90 ** | 0.81 |

| Sebernas 307 | 85.9 ± 0.89 | 49.8 ± 0.92 | 58.0 ** | 0.77 ** | 0.60 |

| No. | Retention time (min) | Peak area (%) | Chemical compounds | Molecular formula | Molecular weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.24 | 8.36 | cis-Pinane | C10H8 | 138.25 |

| 2 | 12.53 | 1.37 | 1,8-Nonadiene, 2,8-dimethyl- | C11H20 | 152.28 |

| 3 | 12.66 | 2.59 | 7-Tridecanone | C13H26O | 198.34 |

| 4 | 12.77 | 2.39 | 3,7,11,15-Tetramethyl-2-hexadecen-1-ol | C20H40O | 296.50 |

| 5 | 13.35 | 2.04 | Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | C17H34O2 | 270.50 |

| 6 | 13.85 | 5.02 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 256.42 |

| 7 | 14.67 | 1.98 | β-D-Mannofuranoside, farnesil- | C21H36O6 | 384.50 |

| 8 | 14.89 | 12.46 | Hexadecanoic acid, trimethylsilyl ester | C19H40O2Si | 328.60 |

| 9 | 15.69 | 2.47 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester, (Z,Z,Z)- | C19H32O2 | 292.50 |

| 10 | 15.86 | 6.65 | Phytol | C20H40O | 296.50 |

| 11 | 16.20 | 2.41 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | C18H30O | 278.43 |

| 12 | 16.29 | 6.22 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid (Z,Z,Z)- | C18H30O2 | 278.40 |

| 13 | 16.63 | 1.51 | Silane, [(3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-2-hexadecenyl)oxi]trimethyl- | C23H48OSi | 368.70 |

| 14 | 17.20 | 2.59 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-, trimethylsilyl ester | C21H40O2Si | 352.60 |

| 15 | 17.30 | 4.42 | α-Linolenic acid, trimethylsilyl ester | C21H38O2Si | 350.61 |

| 16 | 18.09 | 2.78 | Dispiro[2.2.2.0]Octane, 4,5-trans-diphenyl- | C20H20 | 260.40 |

| 17 | 20.93 | 1.48 | Bis(2-(Dimethyllamino)ethyl) ether | C8H20N20 | 160.26 |

| 18 | 25.88 | 10.63 | Squalene | C30H50 | 410.70 |

| 19 | 26.02 | 11.55 | 2-[4-(4-Fluorocinnamoyl)anilino]-3-piperidino-1,4-naphthoquinon | C30H25FN2O3 | 480.50 |

| 20 | 33.42 | 4.99 | Stigmasterol | C29H48O | 412.70 |

| 21 | 34.99 | 6.09 | β-sitosterol | C29H50O | 414.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).