Submitted:

15 October 2024

Posted:

16 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

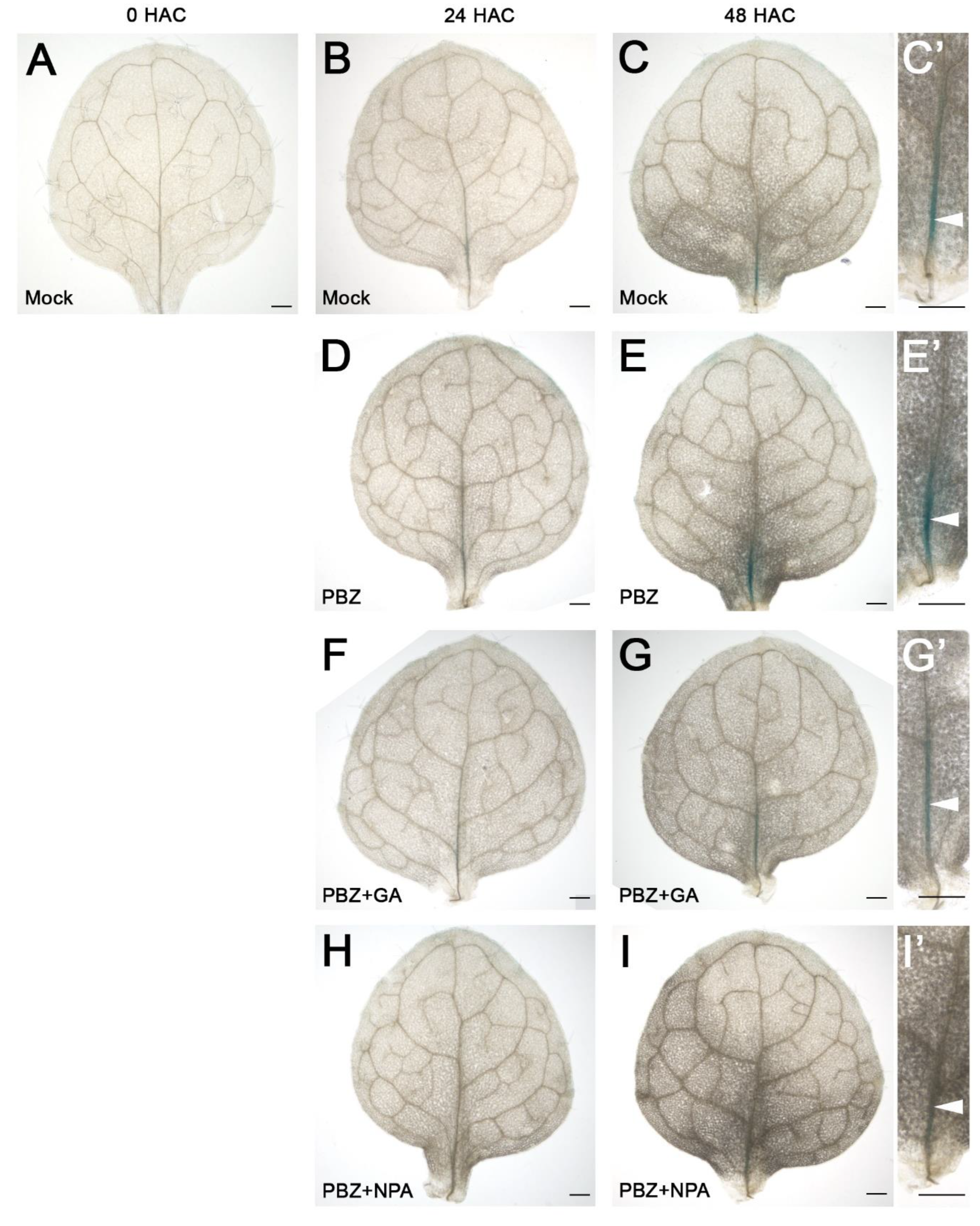

2.1. Blocking of GA Synthesis by PBZ Accelerates AR Formation

2.2. The Positive Effects of Auxin and PBZ Treatment on DNRR Are Distinguishable

2.3. Loss of GA Biosynthesis Enzymes and GA Signaling Overcome Eradication of AR Formation in Erecta Mutant Leaf Explants

2.4. PBZ Treatment Can Rescue Root Regeneration in er Mutants

2.5. Transcriptomic Analysis, Using er Leaf Explants, Revealed That PBZ Treatment Suppresses GA and Brassinosteroids Responses, While Inducing the Expression of the Rooting Factor LBD16

3. Discussion

3.1. Probable Direct Effects of PBZ Treatment on GA and BR Signaling During DNRR

3.2. Probable Direct and Indirect Effects of PBZ Treatment on the Expression of the Rooting Factor LBD16 During DNRR

3.3. Probable GA/BR-Related DNRR Factors Beyond and in Parallel to LBD16

4. Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Culture Conditions

De Novo Root Regeneration (DNRR) and Hormone Treatment

Adventitious Root Formation from Etiolated Hypocotyls

Root Length and Lateral Root (LR) Number Assays

RNA-Seq and Expression Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pan, X.; Yang, Z.; Xu, L. Dual roles of jasmonate in adventitious rooting. EXBOTJ 2021, 72, 6808–6810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochholdinger, F.; Park, W.J.; Sauer, M.; Woll, K. From weeds to crops: Genetic analysis of root development in cereals. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taramino, G.; Sauer, M.; Stauffer, J.L.; Multani, D.; Niu, X.; Sakai, H.; Hochholdinger, F. The maize (Zea mays L.) RTCS gene encodes a LOB domain protein that is a key regulator of embryonic seminal and post-embryonic shoot-borne root initiation. Plant J 2007, 50, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Tai, H.; Saleem, M.; Ludwig, Y.; Majer, C.; Berendzen, K.W.; Nagel, K.A.; Wojciechowski, T.; Meeley, R.B.; Taramino, G.; et al. Cooperative action of the paralogous maize lateral organ boundaries (LOB) domain proteins RTCS and RTCL in shoot-borne root formation. New Phytol 2015, 207, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Yu, X.; Yu, J.; He, X.; Zhang, S.; Shou, H.; Wu, P. ARL1, a LOB-domain protein required for adventitious root formation in rice. Plant J. 2005, 43, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inukai, Y.; Sakamoto, T.; Ueguchi-Tanaka, M.; Shibata, Y.; Gomi, K.; Umemura, I.; Hasegawa, Y.; Ashikari, M.; Kitano, H.; Matsuoka, M. Crown rootless1, Which Is Essential for Crown Root Formation in Rice, Is a Target of an AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR in Auxin Signaling. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R.A.; Li, X.; Duan, S.; Xing, Q.; Müller-Xing, R. Citrus threat huanglongbing (HLB) - Could the rootstock provide the cure? Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druege, U.; Hilo, A.; Pérez-Pérez, J.M.; Klopotek, Y.; Acosta, M.; Shahinnia, F.; Zerche, S.; Franken, P.; Hajirezaei, M.R. Molecular and physiological control of adventitious rooting in cuttings: Phytohormone action meets resource allocation. Ann. Bot. 2019, 123, 929–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.; Xu, C.; Xu, K.; Hu, Y. LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN transcription factors direct callus formation in Arabidopsis regeneration. Cell Res. 2012, 22, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okushima, Y.; Fukaki, H.; Onoda, M.; Theologis, A.; Tasaka, M. ARF7 and ARF19 regulate lateral root formation via direct activation of LBD/ASL genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Cho, C.; Pandey, S.K.; Park, Y.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, J. LBD16 and LBD18 acting downstream of ARF7 and ARF19 are involved in adventitious root formation in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol 2019, 19, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, L.; Hu, X.; Du, Y.; Zhang, G.; Huang, H.; Scheres, B.; Xu, L. Non-canonical WOX11-mediated root branching contributes to plasticity in Arabidopsis root system architecture. Development 2017, 144, 3126–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Ge, Y.; Cai, G.; Pan, X.; Xu, L. WOX-ARF modules initiate different types of roots. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Hu, X.; Qin, P.; Prasad, K.; Hu, Y.; Xu, L. The WOX11-LBD16 Pathway Promotes Pluripotency Acquisition in Callus Cells During De Novo Shoot Regeneration in Tissue Culture. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Xing, R.; Xing, Q. In da club: The cytoplasmic kinase MAZZA joins CLAVATA signaling and dances with CLV1-like receptors. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 4596–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Fang, X.; Liu, W.; Sheng, L.; Xu, L. Adventitious lateral rooting: The plasticity of root system architecture. Physiol Plant 2019, 165, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Xing, R.; Xing, Q. The plant stem-cell niche and pluripotency: 15 years of an epigenetic perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, T.; Ardiansyah, R.; Xu, Q.; Xing, Q.; Müller-Xing, R. Reprogramming of Cell Fate During Root Regeneration by Transcriptional and Epigenetic Networks. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Tong, J.; Xiao, L.; Ruan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zeng, M.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.-W.; Xu, L. YUCCA-mediated auxin biogenesis is required for cell fate transition occurring during de novo root organogenesis in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 4273–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sheng, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Huang, H.; Xu, L. WOX11 and 12 are involved in the first-step cell fate transition during de novo root organogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Auxin Biosynthesis: A Simple Two-Step Pathway Converts Tryptophan to Indole-3-Acetic Acid in Plants. Molecular Plant 2012, 5, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashiguchi, K.; Tanaka, K.; Sakai, T.; Sugawara, S.; Kawaide, H.; Natsume, M.; Hanada, A.; Yaeno, T.; Shirasu, K.; Yao, H.; et al. The main auxin biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 18512–18517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, C.; Shen, X.; Mashiguchi, K.; Zheng, Z.; Dai, X.; Cheng, Y.; Kasahara, H.; Kamiya, Y.; Chory, J.; Zhao, Y. Conversion of tryptophan to indole-3-acetic acid by TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASES OF ARABIDOPSIS and YUCCAs in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 18518–18523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, F.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Sun, L.; Bao, N.; Zhang, T.; Cui, C.-X.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Jasmonate-mediated wound signalling promotes plant regeneration. Nat. Plants 2019. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, B.-B.; Shang, G.-D.; Pan, Y.; Xu, Z.-G.; Zhou, C.-M.; Mao, Y.-B.; Bao, N.; Sun, L.; Xu, T.; Wang, J.-W. AP2/ERF Transcription Factors Integrate Age and Wound Signals for Root Regeneration. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Xing, Q.; Jing, T.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Müller-Xing, R. The epigenetic regulator ULTRAPETALA1 suppresses de novo root regeneration from Arabidopsis leaf explants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dob, A.; Lakehal, A.; Novak, O.; Bellini, C.; Murphy, A. Jasmonate inhibits adventitious root initiation through repression of CKX1 and activation of RAP2.6L transcription factor in Arabidopsis. EXBOTJ 2021, 72, 7107–7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binenbaum, J.; Weinstain, R.; Shani, E. Gibberellin Localization and Transport in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, T. Molecular biology of gibberellin synthesis. Planta 1998, 204, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, E.; Hedden, P.; Sun, T.-p. Highlights in gibberellin research: A tale of the dwarf and the slender. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M. de; Davière, J.-M.; Rodríguez-Falcón, M.; Pontin, M.; Iglesias-Pedraz, J.M.; Lorrain, S.; Fankhauser, C.; Blázquez, M.A.; Titarenko, E.; Prat, S. A molecular framework for light and gibberellin control of cell elongation. Nature 2008, 451, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Martinez, C.; Gusmaroli, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, F.; Chen, L.; Yu, L.; Iglesias-Pedraz, J.M.; Kircher, S.; et al. Coordinated regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana development by light and gibberellins. Nature 2008, 451, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, M.-Y.; Shang, J.-X.; Oh, E.; Fan, M.; Bai, Y.; Zentella, R.; Sun, T.-p.; Wang, Z.-Y. Brassinosteroid, gibberellin and phytochrome impinge on a common transcription module in Arabidopsis. Nat Cell Biol 2012, 14, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-Bartolomé, J.; Minguet, E.G.; Grau-Enguix, F.; Abbas, M.; Locascio, A.; Thomas, S.G.; Alabadí, D.; Blázquez, M.A. Molecular mechanism for the interaction between gibberellin and brassinosteroid signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 13446–13451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, M.; Davière, J.-M.; Cheminant, S.; Regnault, T.; Baumberger, N.; Heintz, D.; Baltz, R.; Genschik, P.; Achard, P. The Arabidopsis DELLA RGA - LIKE3 Is a Direct Target of MYC2 and Modulates Jasmonate Signaling Responses. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3307–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Bai, M.-Y.; Arenhart, R.A.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.-Y. Cell elongation is regulated through a central circuit of interacting transcription factors in the Arabidopsis hypocotyl. Elife 2014, 3, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Galvão, V.C.; Zhang, Y.-C.; Horrer, D.; Zhang, T.-Q.; Hao, Y.-H.; Feng, Y.-Q.; Wang, S.; Schmid, M.; Wang, J.-W. Gibberellin Regulates the Arabidopsis Floral Transition through miR156-Targeted SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING–LIKE Transcription Factors. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3320–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, Y.; Richter, R.; Vincent, C.; Martinez-Gallegos, R.; Porri, A.; Coupland, G. Multi-layered Regulation of SPL15 and Cooperation with SOC1 Integrate Endogenous Flowering Pathways at the Arabidopsis Shoot Meristem. Dev. Cell 2016, 37, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Tian, H.; Park, J.; Oh, D.-H.; Hu, J.; Zentella, R.; Qiao, H.; Dassanayake, M.; Sun, T.-p. The master growth regulator DELLA binding to histone H2A is essential for DELLA-mediated global transcription regulation. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 1291–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, I.; Libbert, E. Adventivwurzelbildung bei der Windepflanze Calystegia sepium (L.) R. Br: Stimulation durch Auxine, Vitamine und den Gihherellinantagonisten 2-(Chloräthyl)trimethylammoniumchlorid 1 1)Zweiter Teil einer Dissertation der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Rostock (URBAN 1965). Der dritte Teil wird anschließend publiziert. ). Flora oder Allgemeine botanische Zeitung. Abt. A, Physiologie und Biochemie 1967, 157, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRIAN, P.W.; HEMMING, H.G.; LOWE, D. Inhibition of Rooting of Cuttings by Gibberellic Acid: With one Figure in the Text. Ann. Bot. 1960, 24, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauriat, M.; Petterle, A.; Bellini, C.; Moritz, T. Gibberellins inhibit adventitious rooting in hybrid aspen and Arabidopsis by affecting auxin transport. Plant J. 2014, 78, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busov, V.; Meilan, R.; Pearce, D.W.; Rood, S.B.; Ma, C.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Strauss, S.H. Transgenic modification of gai or rgl1 causes dwarfing and alters gibberellins, root growth, and metabolite profiles in Populus. Planta 2006, 224, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, H. Die Wirkung von Gibberellinsure und Indolylessigsure auf die Wurzelbildung von Tomatenstecklingen. Planta 1967, 74, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, W.; Li, J.; Jiang, W.; Xiao, C.; Wei, D.; Yang, C.; Xu, R.; et al. Gibberellin disturbs the balance of endogenesis hormones and inhibits adventitious root development of Pseudostellaria heterophylla through regulating gene expression related to hormone synthesis. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2021, 28, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BRIAN, P.W.; HEMMING, H.G.; Radley, M. A Physiological Comparison of Gibberellic Acid with Some Auxins. Physiol Plant 1955, 8, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, J. Studies on the Physiological Effect of Gibberellin II. Physiol Plant 1958, 11, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, B.; Wang, J.; Sauter, M. Interactions between ethylene, gibberellin and abscisic acid regulate emergence and growth rate of adventitious roots in deepwater rice. Planta 2006, 223, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, S.; Ruiz-Cano, H.; Fernández, M.Á.; Sánchez-García, A.B.; Villanova, J.; Micol, J.L.; Pérez-Pérez, J.M. A Network-Guided Genetic Approach to Identify Novel Regulators of Adventitious Root Formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedden, P.; Graebe, J.E. Inhibition of gibberellin biosynthesis by paclobutrazol in cell-free homogenates ofCucurbita maxima endosperm andMalus pumila embryos. J Plant Growth Regul 1985, 4, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, C.A.; Sheldon, C.C.; Olive, M.R.; Walker, A.R.; Zeevaart, J.A.D.; Peacock, W.J.; Dennis, E.S. Cloning of the Arabidopsisent -kaurene oxidase gene GA 3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95, 9019–9024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helliwell, C.A.; Poole, A.; James Peacock, W.; Dennis, E.S. Arabidopsis ent -Kaurene Oxidase Catalyzes Three Steps of Gibberellin Biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1999, 119, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabadí, D.; Gil, J.; Blázquez, M.A.; García-Martínez, J.L. Gibberellins Repress Photomorphogenesis in Darkness. Plant Physiol. 2004, 134, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.-L.; Ogawa, M.; Fleet, C.M.; Zentella, R.; Hu, J.; Heo, J.-o.; Lim, J.; Kamiya, Y.; Yamaguchi, S.; Sun, T.-p. SCARECROW-LIKE 3 promotes gibberellin signaling by antagonizing master growth repressor DELLA in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 2160–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Schwarz, S.; Saedler, H.; Huijser, P. SPL8, a local regulator in a subset of gibberellin-mediated developmental processes in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 2007, 63, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Ji, Y.; He, W.; Jiang, Z.; Li, M.; Guo, H. Coordinated regulation of apical hook development by gibberellins and ethylene in etiolated Arabidopsis seedlings. Cell Res 2012, 22, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yu, R.; Fan, L.-M.; Wei, N.; Chen, H.; Deng, X.W. DELLA-mediated PIF degradation contributes to coordination of light and gibberellin signalling in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Han, Y.; Li, J.; Ding, M.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, F.; Soppe, W.J.; Liu, Y.; Leubner, G. Arabidopsis thaliana SEED DORMANCY 4-LIKE regulates dormancy and germination by mediating the gibberellin pathway. EXBOTJ 2020, 71, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cao, H.; Zhang, C.; Chen, F.; Liu, Y. The SNF5-type protein BUSHY regulates seed germination via the gibberellin pathway and is dependent on HUB1 in Arabidopsis. Planta 2022, 255, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrique, A.; Campinhos, E.N.; Ono, E.O.; Pinho, S.Z.d. Effect of plant growth regulators in the rooting of Pinus cuttings. Braz. arch. biol. technol. 2006, 49, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, G. The effect of paclobutrazol on in vitro rooting, transplant establishment and growth of fruit plants. Plant Growth Regulation 1988, 7, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Križan, B.; Ondrušiková, E.; Dradi, G.; Rocasaglia, R. The effect of paclobutrazol on in vitro rooting and growth of GF-677 hybrid peach rootstock. Acta Physiol Plant 2006, 28, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, R. Optimization of rhizogenesis for in vitro shoot culture of Pinus massoniana Lamb. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.L.; Li, L.; Wu, K.; Peeters, A.J.; Gage, D.A.; Zeevaart, J.A. The GA5 locus of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a multifunctional gibberellin 20-oxidase: Molecular cloning and functional expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1995, 92, 6640–6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Goodman, H.M.; Ausubel, F.M. Cloning the Arabidopsis GA1 Locus by Genomic Subtraction. Plant Cell 1992, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabadí, D.; Gallego-Bartolomé, J.; Orlando, L.; García-Cárcel, L.; Rubio, V.; Martínez, C.; Frigerio, M.; Iglesias-Pedraz, J.M.; Espinosa, A.; Deng, X.W.; et al. Gibberellins modulate light signaling pathways to prevent Arabidopsis seedling de-etiolation in darkness. Plant J 2008, 53, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, H.; Sasaki, E.; Akiyama, K.; Maruyama-Nakashita, A.; Nakabayashi, K.; Li, W.; Ogawa, M.; Yamauchi, Y.; Preston, J.; Aoki, K.; et al. The AtGenExpress hormone and chemical treatment data set: Experimental design, data evaluation, model data analysis and data access. Plant J. 2008, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Hanada, A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Kuwahara, A.; Kamiya, Y.; Yamaguchi, S. Gibberellin Biosynthesis and Response during Arabidopsis Seed Germination[W]. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1591–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.M.; Araújo, W.L.; Fernie, A.R.; Schippers, J.H.M.; Mueller-Roeber, B. Translatome and metabolome effects triggered by gibberellins during rosette growth in Arabidopsis. EXBOTJ 2012, 63, 2769–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vain, T.; Raggi, S.; Ferro, N.; Barange, D.K.; Kieffer, M.; Ma, Q.; Doyle, S.M.; Thelander, M.; Pařízková, B.; Novák, O.; et al. Selective auxin agonists induce specific AUX/IAA protein degradation to modulate plant development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 6463–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorin, C.; Bussell, J.D.; Camus, I.; Ljung, K.; Kowalczyk, M.; Geiss, G.; McKhann, H.; Garcion, C.; Vaucheret, H.; Sandberg, G.; et al. Auxin and Light Control of Adventitious Rooting in Arabidopsis Require ARGONAUTE1. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1343–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Chai, M.; Li, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhang, J.; Sun, G.; Jiang, C.; Shi, L. Global Transcriptome Profiling Analysis of Inhibitory Effects of Paclobutrazol on Leaf Growth in Lily (Lilium Longiflorum-Asiatic Hybrid). Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divya Nair, V.; Jaleel, C.A.; Gopi, R.; Panneerselvam, R. Changes in growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Ocimum sanctum under growth regulator treatments. Front. Biol. China 2009, 4, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karidas, P.; Challa, K.R.; Nath, U. The tarani mutation alters surface curvature in Arabidopsis leaves by perturbing the patterns of surface expansion and cell division. EXBOTJ 2015, 66, 2107–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Aloni, D.D.; Adur, U.; Hazon, H.; Klein, J.D. Characterization of Growth-Retardant Effects on Vegetative Growth of Date Palm Seedlings. J Plant Growth Regul 2013, 32, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, J.; K. , A.; Kumar, R.K.; Jacob, J. MORPHOLOGICAL CHANGES IN YOUNG PLANTS OF HEVEA BRASILIENSIS INDUCED BY PACLOBUTRAZOL. Rubber Science 2015, 28, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, G.E.; Boag, T.S.; Stewart, W.P. Changes in leaf, stem, and root anatomy of Chrysanthemum cv. Lillian Hoek following paclobutrazol application. J Plant Growth Regul 1992, 11, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.C.; Matsumoto, S.N.; Ribeiro, A.F.F.; Viana, A.E.S.; Tagliaferre, C.; Carvalho, F.D.; Pereira, L.F.; Silva, V.A. Morphophysiology and quality of yellow passion fruit seedlings submitted to inhibition of gibberellin biosynthesis. Acta Sci. Agron. 2020, 43, e51541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegaw, T.; Hammes, S.; Robbertse, J. Paclobutrazol-induced Leaf, Stem, and Root Anatomical Modifications in Potato. HortScience 2005, 40, 1343–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, L.M.; Amasino, R.M. Senescence Is Induced in Individually Darkened Arabidopsis Leaves, but Inhibited in Whole Darkened Plants. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 876–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yang, C.; Gao, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Kuai, B. Age-Triggered and Dark-Induced Leaf Senescence Require the bHLH Transcription Factors PIF3, 4, and 5. Molecular Plant 2014, 7, 1776–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leivar, P.; Monte, E. PIFs: Systems Integrators in Plant Development. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Carol, P.; Richards, D.E.; King, K.E.; Cowling, R.J.; Murphy, G.P.; Harberd, N.P. The Arabidopsis GAI gene defines a signaling pathway that negatively regulates gibberellin responses. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 3194–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torii, K.U.; Mitsukawa, N.; Oosumi, T.; Matsuura, Y.; Yokoyama, R.; Whittier, R.F.; Komeda, Y. The Arabidopsis ERECTA gene encodes a putative receptor protein kinase with extracellular leucine-rich repeats. Plant Cell 1996, 8, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lease, K.A.; Lau, N.Y.; Schuster, R.A.; Torii, K.U.; Walker, J.C. Receptor serine/threonine protein kinases in signalling: Analysis of the erecta receptor-like kinase of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 2001, 151, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-Y.; Krishnakumar, V.; Chan, A.P.; Thibaud-Nissen, F.; Schobel, S.; Town, C.D. Araport11: A complete reannotation of the Arabidopsis thaliana reference genome. Plant J 2017, 89, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieu, I.; Ruiz-Rivero, O.; Fernandez-Garcia, N.; Griffiths, J.; Powers, S.J.; Gong, F.; Linhartova, T.; Eriksson, S.; Nilsson, O.; Thomas, S.G.; et al. The gibberellin biosynthetic genes AtGA20ox1 and AtGA20ox2 act, partially redundantly, to promote growth and development throughout the Arabidopsis life cycle. Plant J 2008, 53, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, A.; Furumoto, T.; Ishida, S.; Takahashi, Y. AGF1, an AT-Hook Protein, Is Necessary for the Negative Feedback of AtGA3ox1 Encoding GA 3-Oxidase. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiponova, M.K.; Morohashi, K.; Vanhoutte, I.; Machemer-Noonan, K.; Revalska, M.; van Montagu, M.; Grotewold, E.; Russinova, E. Helix–loop–helix/basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor network represses cell elongation in Arabidopsis through an apparent incoherent feed-forward loop. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 2824–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Fan, X.-Y.; Cao, D.-M.; Tang, W.; He, K.; Zhu, J.-Y.; He, J.-X.; Bai, M.-Y.; Zhu, S.; Oh, E.; et al. Integration of Brassinosteroid Signal Transduction with the Transcription Network for Plant Growth Regulation in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Choe, S. The Regulation of Brassinosteroid Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 2013, 32, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Verstraeten, I.; Trinh, H.K.; Lardon, R.; Schotte, S.; Olatunji, D.; Heugebaert, T.; Stevens, C.; Quareshy, M.; Napier, R.; et al. Chemical induction of hypocotyl rooting reveals extensive conservation of auxin signalling controlling lateral and adventitious root formation. New Phytologist 2023, 240, 1883–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorwerk, S.; Biernacki, S.; Hillebrand, H.; Janzik, I.; Müller, A.; Weiler, E.W.; Piotrowski, M. Enzymatic characterization of the recombinant Arabidopsis thaliana nitrilase subfamily encoded by the NIT 2/ NIT 1/ NIT 3-gene cluster. Planta 2001, 212, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Pu, H. Crystal structure of methylesterase family member 16 (MES16) from Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2016, 474, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognetti, V.B.; van Aken, O.; Morreel, K.; Vandenbroucke, K.; van de Cotte, B.; Clercq, I. de; Chiwocha, S.; Fenske, R.; Prinsen, E.; Boerjan, W.; et al. Perturbation of Indole-3-Butyric Acid Homeostasis by the UDP-Glucosyltransferase UGT74E2 Modulates Arabidopsis Architecture and Water Stress Tolerance. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2660–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Hu, Y.; Aoi, Y.; Hira, H.; Ge, C.; Dai, X.; Kasahara, H.; Zhao, Y. Local conjugation of auxin by the GH3 amido synthetases is required for normal development of roots and flowers in Arabidopsis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2022, 589, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherp, A.M.; Westfall, C.S.; Alvarez, S.; Jez, J.M. Arabidopsis thaliana GH3.15 acyl acid amido synthetase has a highly specific substrate preference for the auxin precursor indole-3-butyric acid. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2018, 293, 4277–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takase, T.; Nakazawa, M.; Ishikawa, A.; Manabe, K.; Matsui, M. DFL2, a New Member of the Arabidopsis GH3 Gene Family, is Involved in Red Light-Specific Hypocotyl Elongation. Plant and Cell Physiology 2003, 44, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbez, E.; Kubeš, M.; Rolčík, J.; Béziat, C.; Pěnčík, A.; Wang, B.; Rosquete, M.R.; Zhu, J.; Dobrev, P.I.; Lee, Y.; et al. A novel putative auxin carrier family regulates intracellular auxin homeostasis in plants. Nature 2012, 485, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gälweiler, L.; Guan, C.; Müller, A.; Wisman, E.; Mendgen, K.; Yephremov, A.; Palme, K. Regulation of Polar Auxin Transport by AtPIN1 in Arabidopsis Vascular Tissue. Science 1998, 282, 2226–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Huang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Mou, Z.; Li, J. Increased Expression of MAP KINASE KINASE7 Causes Deficiency in Polar Auxin Transport and Leads to Plant Architectural Abnormality in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.; Li, B.; Li, S.; Liang, Y.; Wu, X.; Ma, M.; Wang, J.; Gao, J.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Cascade MKK7-MPK6 Plays Important Roles in Plant Development and Regulates Shoot Branching by Phosphorylating PIN1 in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol 2016, 14, e1002550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejos, R.; Rodriguez-Furlán, C.; Adamowski, M.; Sauer, M.; Norambuena, L.; Friml, J.; Russinova, J. PATELLINS are regulators of auxin-mediated PIN1 relocation and plant development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Cell Science 2018, 131, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perotti, M.F.; Ribone, P.A.; Cabello, J.V.; Ariel, F.D.; Chan, R.L. AtHB23 participates in the gene regulatory network controlling root branching, and reveals differences between secondary and tertiary roots. Plant J 2019, 100, 1224–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargmann, B.O.R.; Birnbaum, K.D.; Brenner, E.D. An undergraduate study of two transcription factors that promote lateral root formation. Biochem Molecular Bio Educ 2014, 42, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yu, J.; Ge, Y.; Qin, P.; Xu, L. Pivotal role of LBD16 in root and root-like organ initiation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 3329–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, Z. DELLA–PIF Modules: Old Dogs Learn New Tricks. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 813–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-Y.; Sae-Seaw, J.; Wang, Z.-Y. Brassinosteroid signalling. Development 2013, 140, 1615–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, D.; Zhao, J.; Jing, Y.; Fan, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Xin, W.; Hu, Y.; Yu, H. The Arabidopsis IDD14, IDD15, and IDD16 Cooperatively Regulate Lateral Organ Morphogenesis and Gravitropism by Promoting Auxin Biosynthesis and Transport. PLoS Genet 2013, 9, e1003759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Olson, A.; Kim, K.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Ware, D. HB31 and HB21 regulate floral architecture through miRNA396/GRF modules in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol Rep 2023, 149, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.E.; Ercoli, M.F.; Debernardi, J.M.; Breakfield, N.W.; Mecchia, M.A.; Sabatini, M.; Cools, T.; Veylder, L. de; Benfey, P.N.; Palatnik, J.F. MicroRNA miR396 Regulates the Switch between Stem Cells and Transit-Amplifying Cells in Arabidopsis Roots. Plant Cell 2016, 27, 3354–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, M.; Thurow, C.; Gatz, C. TGA Transcription Factors Activate the Salicylic Acid-Suppressible Branch of the Ethylene-Induced Defense Program by Regulating ORA59 Expression. Plant Physiol. 2014, 165, 1671–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinovich, L.; Weiss, D. The Arabidopsis cysteine-rich protein GASA4 promotes GA responses and exhibits redox activity in bacteria and in planta. Plant J 2010, 64, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, N.R. A NAC Transcription Factor for Flooding: SHYG Helps Plants Keep Their Leaves in the Air. Plant Cell 2014, 25, 4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, M.; Arif, M.; Fisahn, J.; Xue, G.-P.; Balazadeh, S.; Mueller-Roeber, B. NAC Transcription Factor SPEEDY HYPONASTIC GROWTH Regulates Flooding-Induced Leaf Movement in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 25, 4941–4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnaswamy, S.; Verma, S.; Rahman, M.H.; Kav, N.N.V. Functional characterization of four APETALA2-family genes (RAP2.6, RAP2.6L, DREB19 and DREB26) in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 2011, 75, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Chang, Y.; Guo, J.; Chen, J.-G. Arabidopsis Ovate Family Protein 1 is a transcriptional repressor that suppresses cell elongation. Plant J 2007, 50, 858–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.L.; Fedoroff, N.V. LRP1, a gene expressed in lateral and adventitious root primordia of arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Yadav, S.; Singh, A.; Mahima, M.; Singh, A.; Gautam, V.; Sarkar, A.K. Auxin signaling modulates LATERAL ROOT PRIMORDIUM 1 (LRP 1 ) expression during lateral root development in Arabidopsis. Plant J 2020, 101, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qu, Y.; Sheng, L.; Liu, J.; Huang, H.; Xu, L. A simple method suitable to study de novo root organogenesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Xing, Q.; Müller-Xing, R. A novel UV-B priming system reveals an UVR8-depedent memory, which provides resistance against UV-B stress in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1879533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xing, Q.; Liu, X.; Müller-Xing, R. Expression of the Populus Orthologues of AtYY1, YIN and YANG Activates the Floral Identity Genes AGAMOUS and SEPALLATA3 Accelerating Floral Transition in Arabidopsis thaliana. IJMS 2023, 24, 7639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Xing, R.; Ardiansyah, R.; Xing, Q.; Faivre, L.; Tian, J.; Wang, G.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Jing, T.; Leau, E. de; et al. Polycomb proteins control floral determinacy by H3K27me3-mediated repression of pluripotency genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 8, e0127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xing, Q.; Ardiansyah, R.; Zhou, H.; Ali, S.; Jing, T.; Tian, J.; Song, X.S.; Li, Y.; et al. Ectopic expression of the transcription factor CUC2 restricts growth by cell cycle inhibition in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Signal. Behav. 2020, 15, 1706024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Xing, R.; Clarenz, O.; Pokorny, L.; Goodrich, J.; Schubert, D. Polycomb-Group Proteins and FLOWERING LOCUS T Maintain Commitment to Flowering in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 2457–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).