1. Introduction

A great diversity of invertebrates has assimilated different ecological niches in almost completely all types of ecosystems has determined rich spectrum of forms and adaptations allowing them to survive and to realize their life-cycles in different environment and habitats. The study of an adaptive potential of invertebrates enables scientists to realize analogue mechanisms in engineering, medical, architectural, agricultural, textile, food industry and many other developed branches of the practical economics [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

One of the actual direction of the contemporary agriculture development is an involvement of terrestrial invertebrates to gain the animal protein product with a nutrient-dense composition (i.e. supplied with relatively more nutrients than calories) applied for feed and food production [

6]. World growth of food products requirements demands for search of new sources of the animal protein in addition to the traditional cattle farming production [

7,

8,

9]. Currently, interest in protein production from terrestrial invertebrates is increasing [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The major attention is paid to so-called deep processing of stuff gained from an agricultural animal, precisely: liver, skin, accessible matter of bone tissue etc. Within a frame of an innovative approach, a new method of production of snack using skin of agricultural livestock, birds and fish has been presented [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. A profound study of nutrient composition of skin of African frogs has revealed the high content of main nutrients, especially protein. This may be used for the production of animal protein containing food products in the regions with serious deficiency of protein in diet [

26]. Nevertheless, the use of “additional” protein containing food products cannot solve the protein deficiency problem, and the production remains at the same level of almost completely exhausted potential of agriculture. The burden on ecosystems, with its connection to the production of feed and necessity to use poultry and livestock excrements related to III-V hazard classes, as well as to the influence of the processing industry, significantly limits further increase in total livestock numbers and has negative influence on natural and urban ecosystems [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. To compensate a lack of animal protein, avoiding the above-mentioned problems, it is needed to use the biomass of invertebrates as an alternative to traditional resources of protein [

31,

34,

35], but with reference to the safety of reared edible invertebrates [

9,

11,

31,

36,

37].

Currently, a trend to raise terrestrial insects, molluscs, arachnids, worms and other invertebrates is actually being developed worldwide [

30,

38,

39,

40], including Russia [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Despite the generating technologies to raise and actively operating farms to produce the biomass of invertebrates mainly to feed domestic animals, this work is currently at an experimental level and far from being fully adopted at an industrial level. Nonetheless, five species of insects authorized by the European Commission (EC) for sale, farming and novel food consumption are already used for the preparation of flour to enrich bread ingredients with the animal protein, and the EC Regulation no. 853/2004 defines five species of terrestrial gastropods as ‘edible snails’ to be used in restaurant gastronomy [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46].

As mentioned before, one of the important ways in the protein production industry development assumes a high quality biomass gained from terrestrial invertebrates, with its potential ability of the nutrient composition enhancement, its high bioavailability and bioaccessability of main nutrients.

It is important to mention that the forage, development and living conditions are significantly influenced on nutrient composition in biomass of invertebrates. The realisation of feasible methods of the biomass enrichment allowing to gain maximum nutrient density product is necessary to obtain high efficiency results under the generation of terrestrial invertebrates raising technology. The directional enrichment of feeding substrate to gain necessary level of particular nutrients in the biomass of model species of invertebrates, presented the main theme of the Project aimed to study nutrient composition design of biomass, is one of such methods.

In course of the study, four invertebrate species belonging to three phylums of Animalia have been selected, namely: the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758), the Speckled cockroach Nauphoeta cinerea (Olivier, 1789) (Arthropoda: Insecta), the Giant African land snail Lissachatina fulica (Férussac, 1821) (Mollusca: Gastropoda) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) (Annelida: Lumbricidae). Standard living conditions have been provided and a standardized food substrate has been prepared for all model species. During the experiment the substrate was enriched with the substances defining accumulation of particular nutrients in biomass of model species (so-called precursors), the result was considered as potential of accumulation of necessary nutrients as demanded.

In the previous work of nutrient composition in biomass of two invertebrate species, the Speckled cockroach Nauphoeta cinerea (Olivier, 1789) and the Giant African land snail Lissachatina fulica (Férussac, 1821), have been studied and analysed. Biomass content variation of other two species, the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) are studied in the present paper.

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental Design

Two invertebrate species, the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826), were chosen as model species.

The experiment was held in five groups for each model species. The first group was the control one; the individuals were being fed with a substrate with a lack of enrichment. The second group was developed on a substrate enriched with vitamins C and B7, the third – with a complex mineral addition for plant (chelate), the fourth – with vitamins B1 (thiamin), B3 (niacin) and B9 (folate), and the fifth one was developed on the basis of fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, K.

The cultures were raised under laboratory conditions with a temperature of c. +25˚С and humidity of c. 60% in cricket and c. 80% in earthworms. Model species were placed in separate plastic containers and provided with a feeding substrate and precursors, or without them in case of the control group. The feeding substrate for cockroaches contained a mixture of grated carrot (12 g), oat flakes (10 g), dried milk (1 g) and dried gammarus (1 g), and for earthworms it contained loose tea leaves (5 g). Also, containers with crickets were provided with Petri dishes with water.

The replacement of substrate and addition of precursors were undertaken three times a week. Under a precursor (a substance inserted into the feeding substrate and shared in metabolism of invertebrates) generated a particular nutrient in the biomass. In the experiment the following substances were chosen as precursors: vitamins C and B7 (biotin) to generate protein, a complex mineral addition for plant (chelate) to minerals, vitamins B1, B3 and B9 for concordant vitamins of В-complex, and vitamins A, D, E and K for fat-soluble vitamins.

Enrichment of feeding substrate was generated in two stages. At the first stage precursors were inserted in minimal doses ranging from 1 to 50 mg per 1 kg of feeding substrate according to the type of input substance. Such a dosage corresponds approximately with recommendations for vitamin and mineral rations provided to agricultural animals to prevent hypovitaminosis. At the second stage doses of precursors were increased twice in proportion to each substance input in the substrate. In this case, doses of precursors should have sufficient enriched biomass up to the required level for metabolism and also accumulate particular nutrients. Quantities of input samples of precursors are given in

Table 1.

After 30 days, samples of crude frozen biomass (0.4 kg) of each model species were analysed. The analyses were undertaken in the test centre “OOO Sibtest” as a small-scale innovative enterprise of the National Research Tomsk Polytechnic University, Tomsk, Russia in a laboratory accredited with the license “GOSTAkkreditatsiya”, No.GOST.RU.22152.

Sample analyses were aimed at detecting ash, carbohydrates, chitin, proteins including content and ratio of amino acids, lipids, including analysis of fat acids, vitamins B1 (thiamine), B2 (riboflavin), B3 (niacinamide), B9 (folic acid), B12 (cyanocobalamin), A (retinol palmitate), D3 (cholecalciferol), E (α-tocopherol), K (fillokinone), and minerals: iron (Fe), selenium (Se), zinc (Zn), magnesium (Mg), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), phosphorus (P), lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), molybdenum (Mo), iodine (I), calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), potassium (K), and chlorine (Cl). The calorific values of the biomass for both species were also determined. The protocols of analyses are provided with the reference to GOSTs which are a summary of Russian State standards.

Statistical Analysis

R version 4.0.2 [

47] was used for statistical analysis of the nutrient parameters. For analysis of changes of nutrient composition in dependence of feeding substrate Student t-test for independent samples was applied. Evaluation of significance of differences with control and confidence intervals are estimated with correction to multiply comparisons according to Bonferroni method of correction, in case of 5 comparisons α = 0.01 and in case of 8 comparisons α = 0.006. Accordingly, confidence intervals (CI) on graphs are given with 99% and 99.4% correction for probability.

Results

Nutrient Composition in the Biomass of Model Species

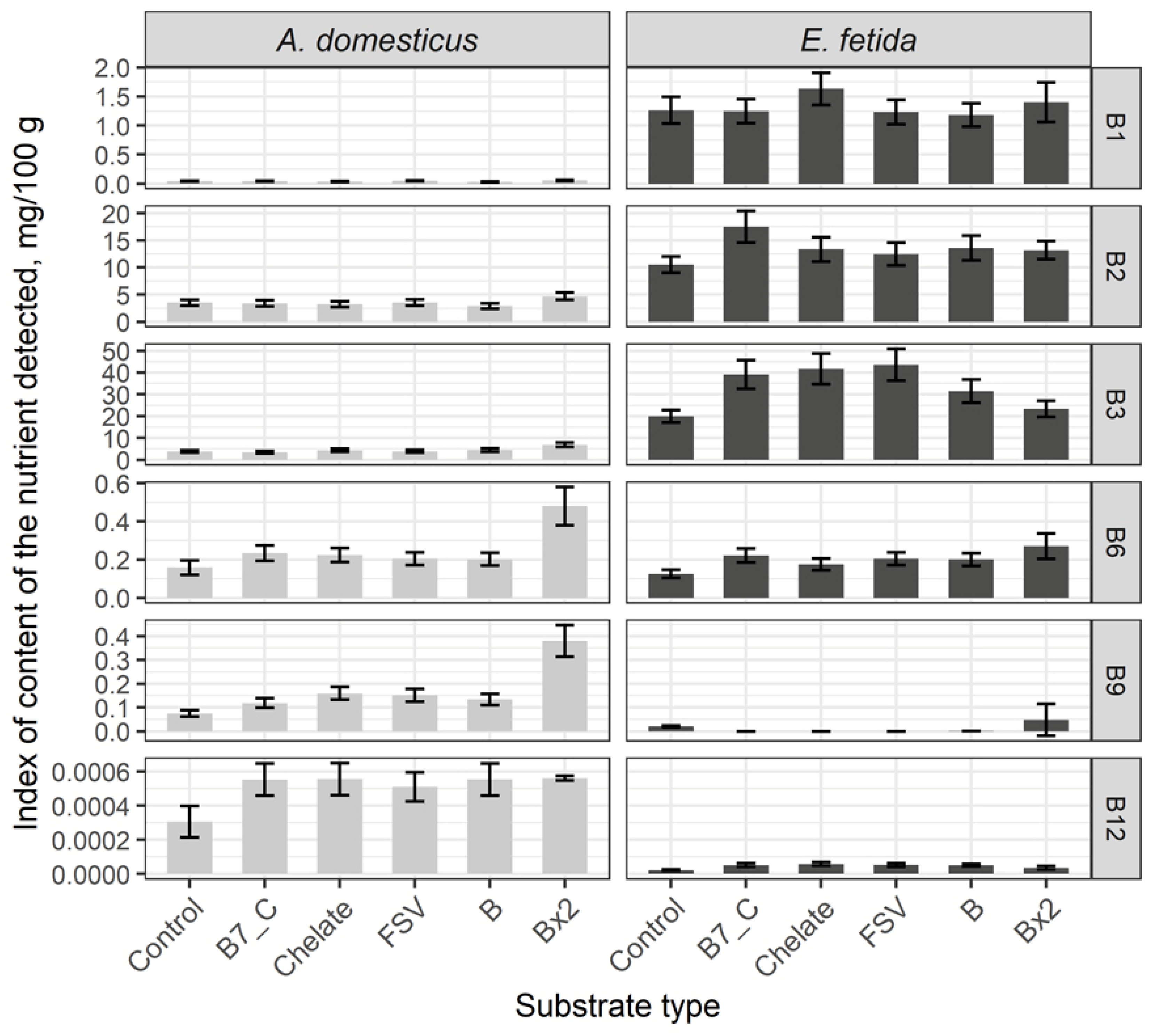

Nutrient composition of the two model species significantly differs. Comparative analysis of B-vitamins content in control group of crickets and earthworms has demonstrated low indexes of B1, B2 and B3 and high level of B9 and B12 in crickets, whereas in earthworms high indexes of B1, B2 and B3 and low B9 and B12 are registered (

Figure 1). The content of B6 vitamin is comparable in both species.

After a single dose substrate enrichment with biotin (B7) and C vitamin, minerals, and fat-soluble and B complex vitamins the content of B1, B2 and B3 vitamins is not changed. Statistically significant increase of B6, B9 and B12 vitamins in comparison with the control group is observed. In result of feeding substrate enrichment with a double dose of B-vitamins the sharp increasing of content of B6 twice higher and B12 in three times is registered.

Statistically significant increasing of B2, B3, B6 and B12 vitamins and decrease of B9 vitamin is registered in earthworms after substrate enrichment with a single dose of biotin (B7) and C vitamin, minerals, and fat-soluble and B complex vitamins, and B1 content is increased only after substrate enrichment with microelements. The increase of all vitamins excepting B3 and B1, their level is comparable with the control group, is registered after substrate enrichment with a double dose of B-vitamins.

General tendencies of nutrient composition change after feeding substrate enrichment in crickets and earthworms are comparable and characterized by increase of the particular B vitamins which level was initially high.

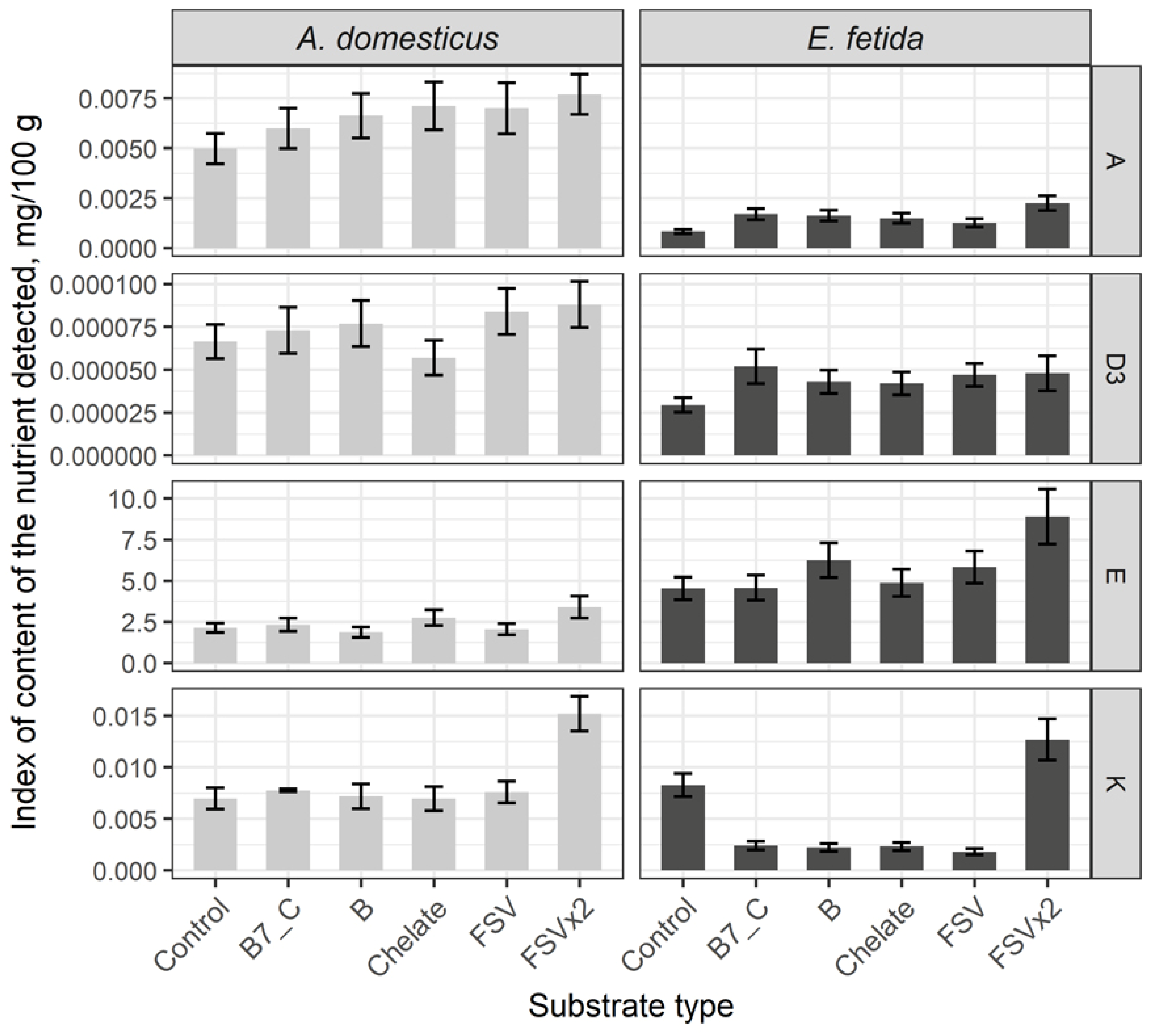

High indexes of A and D3 vitamins in crickets and low in earthworms, and higher content of E and K vitamins in earthworms in the control are revealed after the comparative analysis of fat-soluble vitamins content. Among fat-soluble vitamins, there is registered the increase of content of vitamin A and stable not variable meanings of vitamins D3, E and K after a single dose substrate enrichment with biotin (B7) and C vitamin, minerals, fat-soluble vitamins and B complex vitamins. Double dose enrichments have resulted in increasing of all fat-soluble vitamins in comparison with the control group (

Figure 2).

Overall, doubled dose substrate enrichment with fat-soluble vitamins have increased all vitamins of the group both in the crickets and the earthworms.

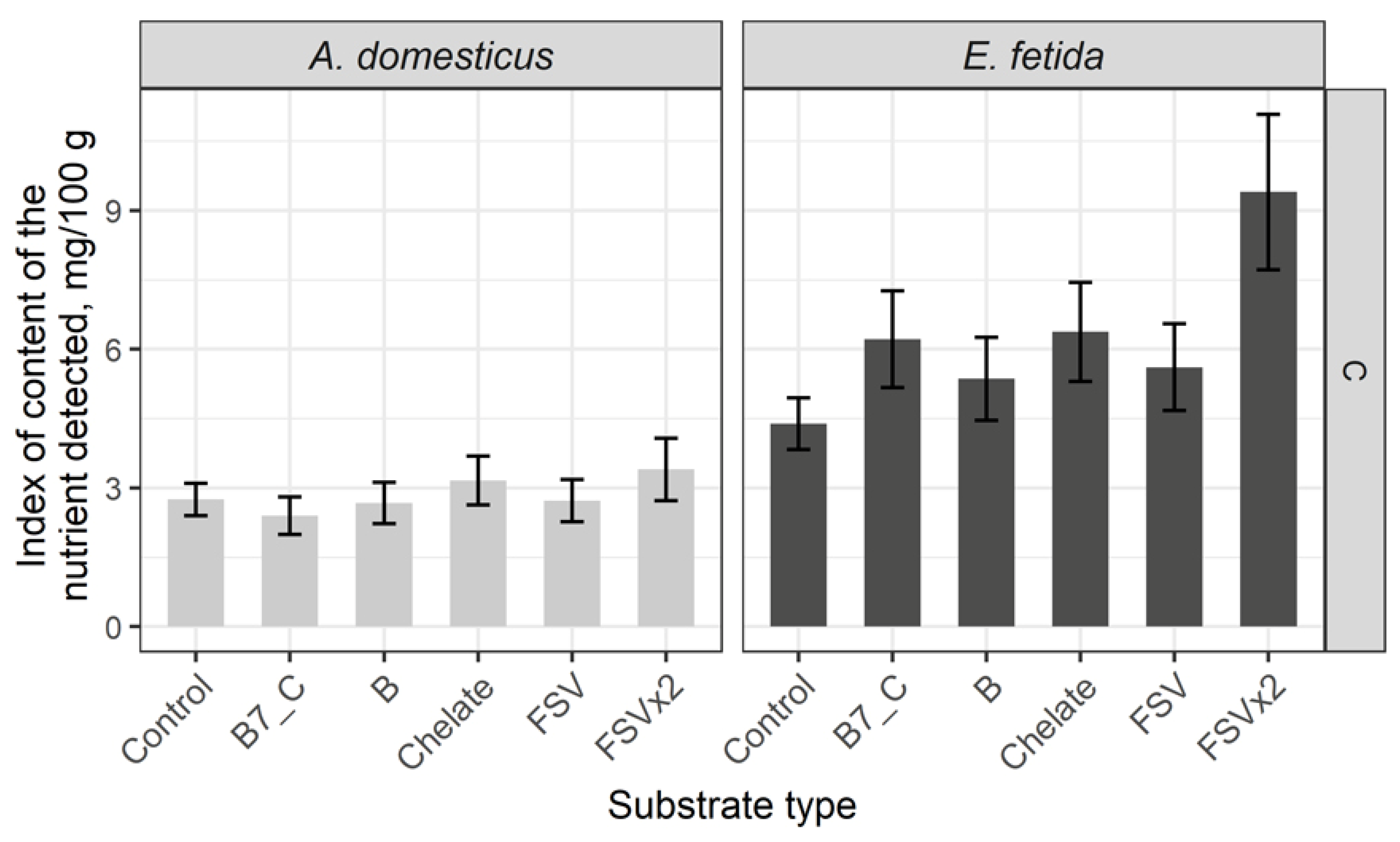

The content of vitamin C in control groups of model species is 1.5 times lower in crickets. After substrate enrichment the content of vitamin C in crickets is not changed, whereas it is significantly increased in earthworms (

Figure 3).

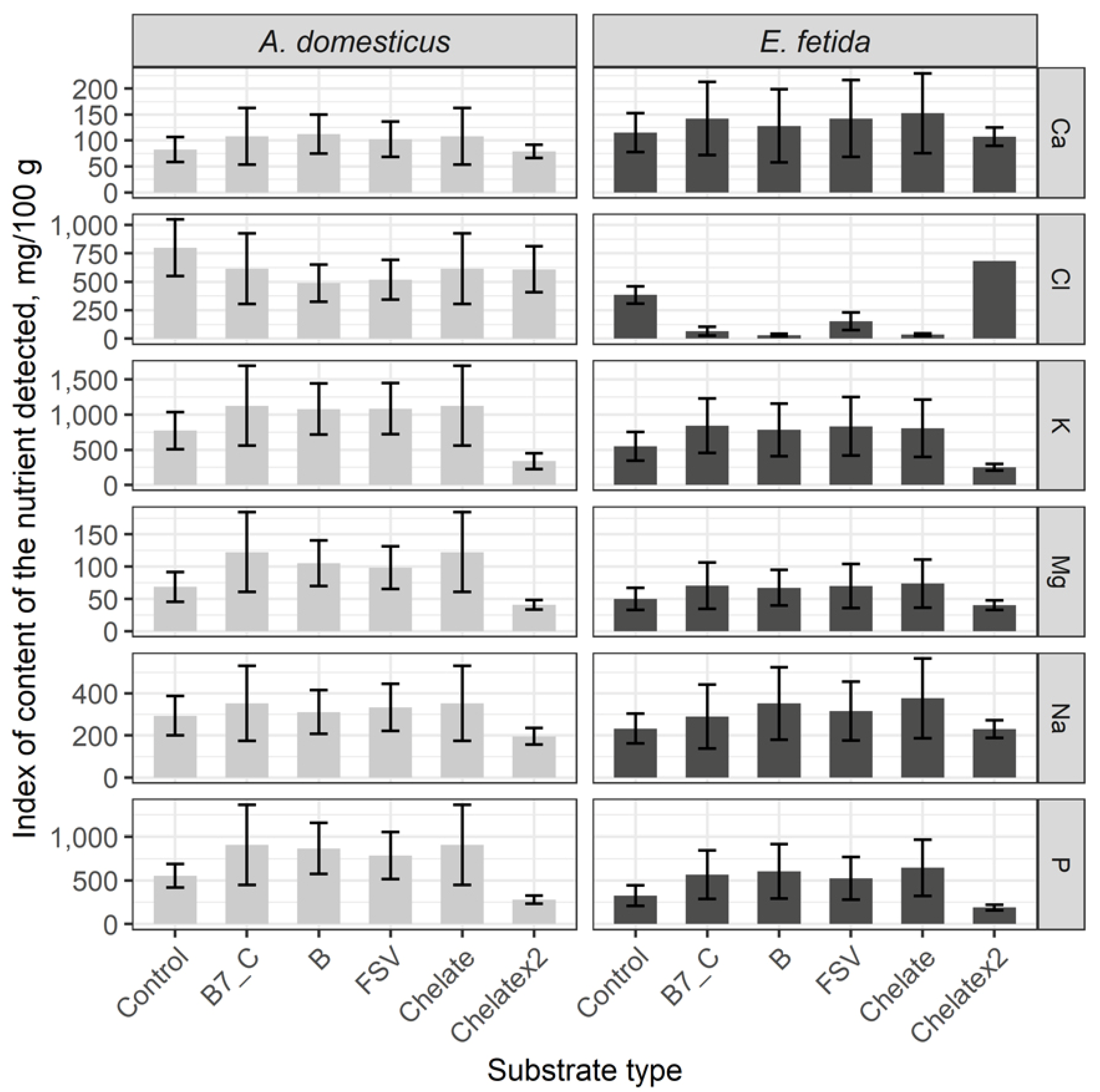

Comparative analysis of macroelements has showed a high content of Cl and P in crickets, but the level of other elements is similar to the control group in crickets and earthworms.

A single dose addition of biotin (B7) and C vitamin, minerals, and fat-soluble and B complex vitamins to feeding substrate has not affected on cricket nutrient composition, but it has significantly decreased the level of Cl in earthworms. Doubled dose enrichments have decreased the level of K and P both in crickets and earthworms, but they have considerably increased the level of Cl in earthworms (

Figure 4).

On the whole, substrate enrichments have not followed to significant increasing of macroelements in crickets and earthworms, but doubled dose enrichment may decrease the level of macroelements in biomass of the model species.

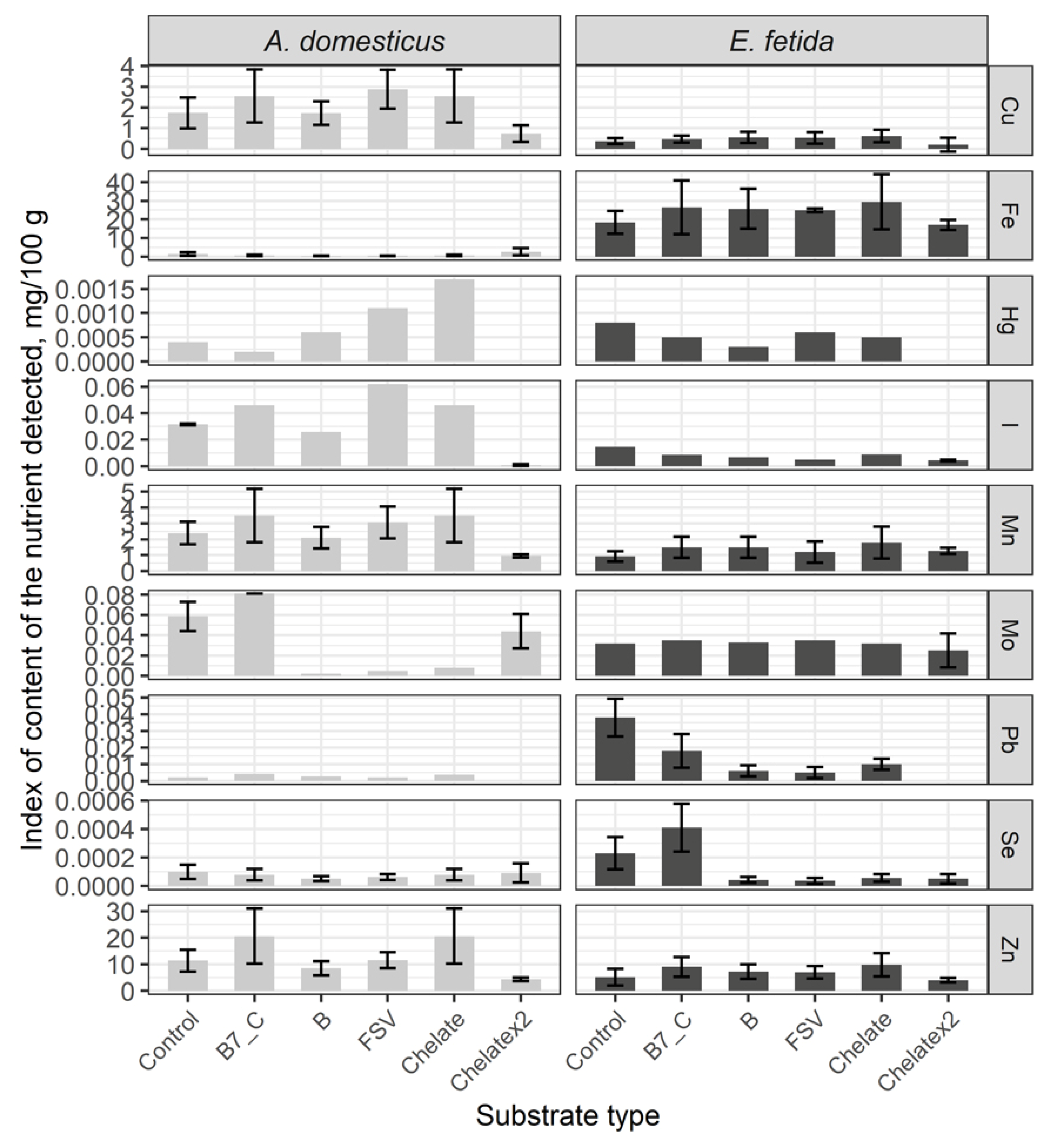

Comparative analysis of the microelements content in the control group seriously differs among crickets and earthworms. Thus, in crickets level of Cu, I, Mn, Mo and Zn is higher, while in earthworms Fe, Hg, Pb, Se (

Figure 5).

After a single dose substrate enrichment, the content of Cu, Fe, I, Mn, Pb and Se considerably has not changed. As a result of substrate enrichments with B vitamins, fat-soluble vitamins and minerals the level of Hg has significantly increased, and the Mo content has decreased. Doubled dose mineral enrichment has brought to a significantly decreased number of microelements excepting Fe and Se registered comparably with the control.

In earthworms, a single dose of substrate enrichments has significantly decreased the level of Pb and Se but indexes of other elements remained comparable with control. Doubled dose enrichment has decreased the content of Hg, I, Pb, Se, and other elements are kept comparable with control.

Thus, the mineral enrichment has had no impact on the microelement composition in crickets, whereas in earthworms the content of Pb and Se has considerably decreased. Doubled dose enrichment has demonstrated a tendency to decreasing of the mineral content in the biomass of model species.

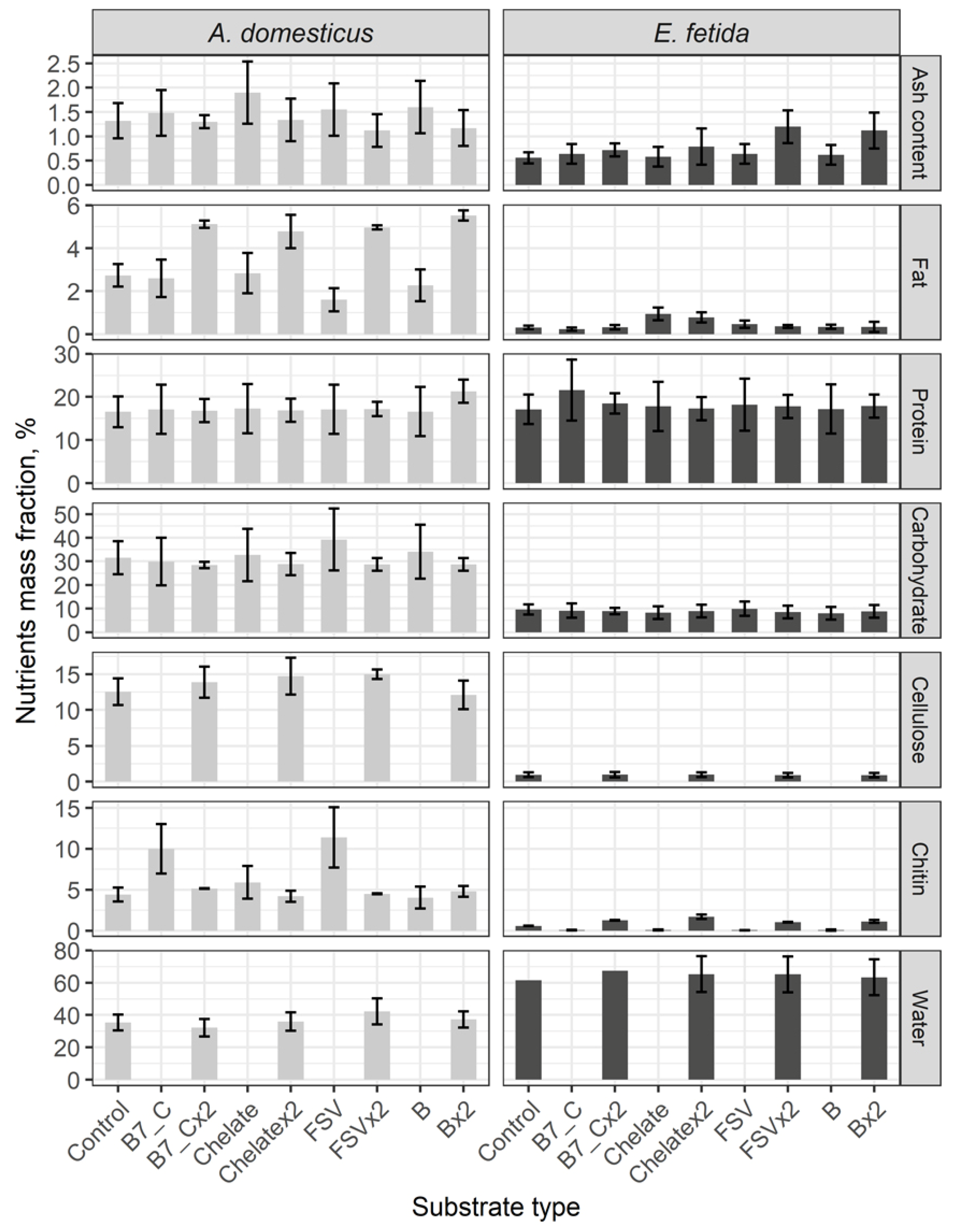

In the control groups of crickets and earthworms the content of protein is similar, the content of water is twice higher in earthworms and the other parameters, namely: ashes, fats, carbohydrates, cellulose, chitin, are significantly higher in crickets (

Figure 6). Differences among the content of ash, protein, carbohydrates, cellulose and water are not registered after a single and a double dose enrichment of feeding substrate of model species of

in vertebrates.

A single dose substrate enrichment has no impact on the fat content, but its doubled dose sharply increases more than twice the level of fat in crickets. After a single dose input of biotin (B7) and fat-soluble vitamins, a level of the chitin content is observed as twice increased, but the chitin content with a double dose is comparable with the control.

The content of fat in earthworms increases only after single and doubled doses of a mineral input. Within a singular dose application, the content of a number of nutrients in earthworms decreases, and with a double dose the content increases.

On the whole, in crickets both in the control and in the experiment groups, the content of main organic nutrients is higher than in earthworms. The content of protein in both model species is comparable.

The enrichment of the feeding substrate has no significant impact on changing of the main parameters of a nutrient composition in the biomass of invertebrates. Only a double dose enrichment has a result in a considerable increase of fat in crickets and the chitin level in earthworms.

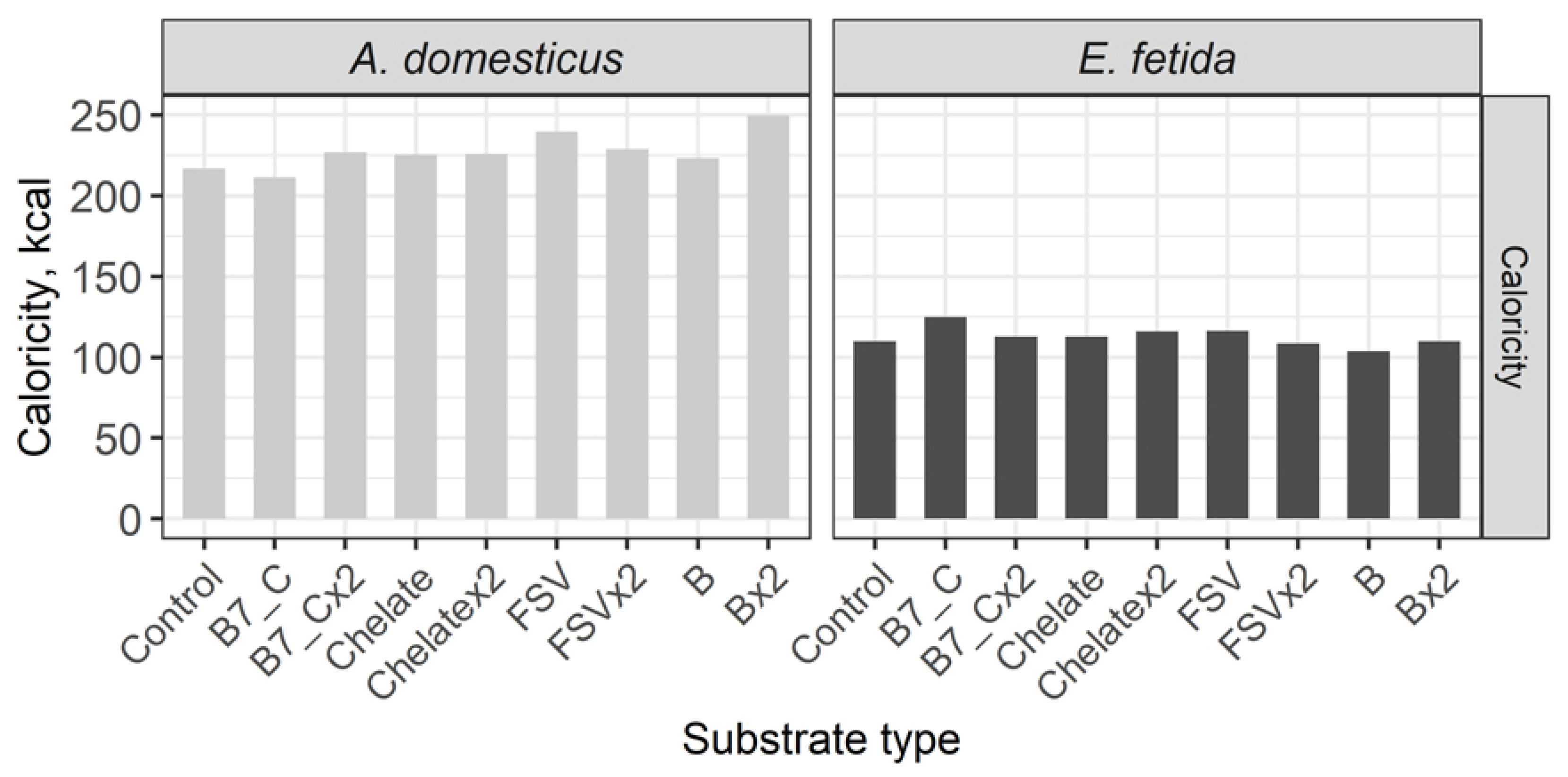

The calorific value of crickets is twice higher than in earthworms and the substrate enrichment has no significant influence on the calorie level in model species (

Figure 7).

Discussion

Both the crickets and the earthworms are traditionally used as an object of research in a field of agriculture. Due to the fact, that the house cricket

Acheta domesticus Linnaeus, 1758 is authorized by the European Commission (EC) for sale, farming and novel food consumption [

41,

42,

43], many articles about the nutrient composition of crickets are published nowadays. Comparative analysis of the nutrient composition in the biomass of different cricket species used for food in the world is given in [

47]. It is stated that only

Acheta domesticus accumulates higher level of protein in its biomass (2.41–71.09 g/100 g dry weight), as well as

Gryllus assimilis and

Gryllus bimaculatus are able to accumulate up to 70 g/100 g dry weight, although a typical level of protein in crickets is about 50 g/100 g dry weight.

Acheta testacea is the species similar to the House cricket accumulates the lowest level of protein, 18 g/100 g dry weight. Thus, nutrient indexes strongly differ in various taxonomically similar species within one group of Orthoptera. Nevertheless, different species of crickets are considered as perspective sources of food protein, minerals and vitamins.

The earthworms are also used as food in some regions of South-East Asia [

49], but mainly the nutrient composition of

Eisenia sp. biomass has been studied to justify the effectiveness of the usage of the earthworms application in the production of livestock feeding (broilers, fish, pigs etc.) [

50,

51,

52]. It is stated, that the feed powder prodused from the earthworm

E. fotida includes the protein content that is six times higher than in the barley flour (66.90% against 11.81%), and when broilers are fed with the mixture of traditional feed with the worm powder, it improves the taste of meat and increases the weight gain [

51]; among Guinea pigs, energy exchange and feed digestibility improve in 10% [

52]; and for fish and crustaceans it provides the necessary fatty acids [

51].

Traditionally, the nutrient composition of invertebrates is considered as a fixed data block, gained after a particular study of the species biomass. Nevertheless, there might be a difference within the nutrient composition or within its level, caused by a number of reasons.

For example, significant differences in the nutrient composition of the earthworm

Eisenia foetida have been registered even using various methods of the biomass fixation [

50]. An oven-dried biomass may preserve a lower level of protein and some minerals, but a high level of fat acids, while a freeze-dried one has shown a higher level of protein and can demonstrate better nutrients detection in the same biomass. Also, there have been registered interspecific differences of biomass content in allied groups of invertebrates. The comparison of the nutrient composition in House Cricket

Acheta domesticus and Field Cricket

Gryllus bimaculatus has revealed a twice higher level of water, ash and carbohydrates, but a twice lower content of fats and fibre in House cricket [

53]. Obviously, the differences in nutrient composition are typical for invertebrate species belonging to various taxonomic ranks or inhabit varied ecological niches. As a result of the experiment, the revealed variations in the composition and level of the nutrient content in biomass of two model species are considered to be logical, however, exact nutrient parameters are regarded to be more interesting.

Opposite values of the vitamins B-group content in crickets and earthworms with a low content of vitamins B1, B2 and B3 in crickets and high in earthworms, and vice versa a high level of B9 and B12 in crickets and a low level in earthworms may be explained by internal physiological reasons of these species, because the substrate enrichment has not changed the content of vitamins, with an initially low level. It is worth to mention, that the doubled dose enrichment increases a level of vitamins B, this level was high in the control. Remarkably, it is possible to increase a level of B-vitamins in crickets and earthworms, but each species will be provided with a high level of particular vitamins, typical to each species.

Fat-soluble vitamins have demonstrated another picture of the content after the substrate enrichment. Its minimal dose has increased a level of vitamins A and D3, their indexes were initially high in crickets and low in earthworms. So, even this minimal enrichment of the food substrate may increase their content in the model species. The doubled dose enrichment has demonstrated a sharp increase of fat-soluble vitamins in the biomass of crickets and earthworms, presenting good perspective of invertebrate biomass enrichment by the fat-soluble vitamins.

A level of vitamin C was higher in the control group of earthworms and increased after the substrate enrichment, i.e. only earthworms are able to accumulate vitamin C in significant quantity. In crickets, the concentration of vitamin C was in a stable level during all experiments. Presumably, this evidence may be explained by the fact that the earthworms growth is in progress through their whole life and they may constantly enlarge in size that needs a high protein content in biomass. Vitamin C is involved in the protein synthesis process and is vitally required for earthworms. The crickets at both larvae and imago stages are covered with a cuticular sheath not allowing them to increase the biomass immediately without the ecdysis, that is why a level of vitamin C is stable and sufficient to supply a vital function of an organism, excepting the biomass expansion.

Unlike vitamins, the content of minerals in organisms of the model species remains stable. Neither singular nor doubled dose of precursors has no results in increasing a minerals level, but a double dose might even decrease the mineral content in biomass. This fact confirms that the accumulation of minerals after the feeding substrate change is not typical for invertebrates, their organisms try to maintain “mineral homeostasis”, that defines a low level of heavy metals and some elements that might cause a toxic effect. In this case, the biomass of invertebrates may be considered as more valuable and healthy than in fish, for example, some fish species are able to accumulate heavy metals and toxins, causing intoxication of an organism as a result [

54,

55,

56,

57].

Differences in content of main nutrients in crickets and earthworms are noticeable in a high content of ash, fats, carbohydrates, cellulose and chitin in crickets, and a twice higher level of water in earthworms, that can be explained by the morphophysiology of these species. Thus, earthworms do not have hard and massive chitin covers and need more water to supply the elasticity of the body and realization of biochemical reactions, while crickets are provided with a high level of chitin in an external skeleton to maintain the homeostasis of an organism under a low water content.

Regarding the aspect of nutrition, it is said that under a similar protein content in the model species, the earthworm biomass is more nutritious, because its protein is not surrounded with hard and indigestible chitin. Probably, morphophysiological organization of invertebrates, provided with hard external coverings, does not allow this significant increase of main substance parameters without changing their morphological indexes, namely: body growth, thinning of cuticle etc.). Apparently, this fact is also determined the stable indexes of the calorific value of both species. Biomass of crickets is twice as rich in calories as one of earthworms, the enrichment of the food substrate does not affect its increase or decrease.

Conclusions

Contrary indexes of b-vitamins, fat-soluble vitamins, C vitamin and microelements content are registered both in the control and the experimental groups of crickets and earthworms.

Similar tendencies of the B-vitamins content increase might be observed in crickets and earthworms with an initially high level in the biomass, after the enrichment of the feeding substrate with B-vitamins precursors.

Doubled dose enrichment of the feeding substrate has a result in increasing of all fat-soluble vitamins in biomass of crickets and earthworms.

In the control group, the content of vitamin C is 1.5 time lower in crickets than in earthworms. After the enrichment of food substrate, a level of vitamin C in crickets is not changed, while in earthworms this level is significantly increased.

The content of all studied macroelements has not significantly changed after the feeding substrate enrichment, but a double dose enrichment has resulted in decrease of the level of macroelements both in crickets and earthworms.

The content of microelements has not changed after a singular dose enrichment, but some microelements, Pb and Se have significantly decreased in earthworms after doubled dose enrichment of feeding substrate.

Doubled dose enrichment of feeding substrate has decreased the content of minerals in the biomass of invertebrates.

An organic content is higher in crickets both in the control and the experiment groups, but a protein content is comparable. The substrate enrichment has no impact on an organic part of nutrients in biomass of the model species, excepting a double dose enrichment that increases fats in crickets and a level of chitin in earthworms.

The calorific value of crickets is twice higher than of earthworms and it is not significantly changed after doubled dose substrate enrichment.

It is revealed that the content of vitamins in biomass of the model species can be controlled within the feeding substrate enrichment process. The enrichment with a high dose of nutrient precursors is not always resulted in increasing of their biomass level, but sometimes the opposite effect is observed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T., V.M. and A.S.; methodology, V.M., I.B., A.B., M.M., S.T., R.B., K.S., M.Sh. and A.S.; formal analysis, S.T., I.B., V.M. and M.M.; investigation, K.S. and M.M.; writing— original draft preparation, S.T., V.M., M.M. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, S.T., E.S., M.M.; visualization, S.T, E.V., M.M. and K.S.; supervision, S.T. and A.S.; project administration, S.T., M.Sh., E.S. and A.S. All authors have read and approved the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study is financially supported by the Russian Science Foundation, project № 23-26-00075 (https://rscf.ru/project/23-26-00075/).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Alexey N. Tchemeris (Tomsk) for his help in the analytical work, to Prof. Mark Seaward (Bradford University, U.K.) for the linguistic revision of the text and to Mrs Nina M. Mordvinova (OOO Sibtest), Tomsk) for accurate chemical laboratory testing of nutrient contents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wilson-Sanders, S.E. Invertebrate Models for Biomedical Research, Testing, and Education. ILAR Journal 2011, 52, 126–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanes, C. Invertebrates and Their Use by Humans. Animals and Human Society 2018, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollo, S.; Vitale, A. Invertebrates and Humans: Science, Ethics, and Policy. The Welfare of Invertebrate Animals 2019, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda García, A.M.; Fracassi, P.; Scherf, B.D.; Hamon, M.; Iannotti, L. Unveiling the Nutritional Quality of Terrestrial Animal Source Foods by Species and Characteristics of Livestock Systems. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannotti, L.; Rueda García, A.M.; Palma, G.; Fontaine, F.; Scherf, B.; Neufeld, L.M.; Zimmerman, R.; Fracassi, P. Terrestrial Animal Source Foods and Health Outcomes for Those with Special Nutrient Needs in the Life Course. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A.; Fulgoni III, V.L. Nutrient density: principles and evaluation tools. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2014, 99, 1223S–1228S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Raamsdonk, L.W.D.; Van der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; De Jong, J. New feed ingredients: the insect opportunity. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A 2017, 34, 1384–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Yang, D.; Liao, H.; Sun, H.; Liu, C.; Wei, L.; Li, F. Edible insects as a food source: a review. Food Production, Processing and Nutrition 2019, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobolkova, B. Edible Insects-the Future of a Healthy Diet? Novel Techniques in Nutrition and Food Science 2019, 4, 000584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonincx, D.G.A.B.; van der Poel, A.F.B. Effects of diet on the chemical composition of migratory locusts (Locusta migratoria). Zoo Biology 2011, 30, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huis, A.; Van Itterbeeck, J.; Klunder, H.; Mertens, E.; Halloran, A.; Muir, G.; Vantomme, P. Edible insects: future prospects for food and feed security. Food and agriculture organization of the united nations: Rome, 2013; pp. 190. https://www.fao.org/3/i3253e/i3253e.pdf.

- Zielińska, E.; Baraniak, B.; Karaś, M.; Rybczyńska, K.; Jakubczyk, A. Selected species of edible insects as a source of nutrient composition. Food Research International 2015, 77, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, C.; Boccuni, A. Current Status of the Insect Producing Industry in Europe. Edible Insects in Sustainable Food Systems. [CrossRef]

- Gorbunova, N.A.; Zakharov, A.N. Edible insects as a source of alternative protein. A review. Theory and practice of meat processing 2021, 6, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshernyshev, S.E.; Babkina, I.B.; Modyaeva, V.P.; Morozova, M.D.; Subbotina, E.Yu.; Shcherbakov, M.V.; Simakova, A.V. Invertebrates of Siberia, a potential source of animal protein for innovative food production. 1. The keelback slugs (Gastropoda: Limacidae). Acta Biologica Sibirica 2022, 8, 749–762. [Google Scholar]

- Tshernyshev, S.E.; Baghirov, R. T-O.; Modyaeva, V.P.; Morozova, M.D.; Skriptcova, K.E.; Subbotina, E.Yu.; Shcherbakov, M.V.; Simakova, A.V. Invertebrates of Siberia, a potential source of animal protein for innovative human food production. 3. Principles of biomass nutrient composition design. Euroasian Entomological Journal 2023, 22, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshernyshev, S.E.; Baghirov, R. T-O.; Modyaeva, V.P.; Morozova, M.D.; Skriptcova, K.E.; Subbotina, E.Yu.; Shcherbakov, M.V.; Simakova, A.V. Invertebrates of Siberia, a potential source of animal protein for innovative food production. 4. New method of protein food and feed products generation. Euroasian Entomological Journal 2023, 22, 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Olivadese, M.; Dindo, M.L. Edible Insects: A Historical and Cultural Perspective on Entomophagy with a Focus on Western Societies. Insects 2023, 14, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siaw, C.L.; Idrus, Z.; Yu, S.Y. Intermediate technology for fish craker (“keropok”) production. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 1985, 20, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widati, U.S. The long influence of boiling on the level of development of rabbit skin rambak crackers after gfrying. Faculty of Animal Husbandry. 1988. University of Brawijaya.

- Kartiwa, U.M. Utilization of Fish Skin as Raw Material for Making Skin Crackers. Thesis. Faculty of Fisheries and Kelatan Sciences. Agricultural Institute, Bogor. 2002.

- Junianto; Haetami, K.; Maulina, I. Fish skin production and utilization it as a basic ingredient in making crackers. Hibah Research Report Competing IV Year I. 2006. Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Sciences Hasanuddin University. Makassar.

- Lilir, F.B.; Palar, C.K.M.; Lontaan, N.N. Effect of time drying on the processing of cow skin crackers. Zootec 2021, 41, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, S.; Hintono, A.; Mulyani, S.; Ardi, F.A.; Arifan, F. Comparison of chemical characteristics of various commercial animal skin crackers. American Journal of Animal and Veterinary Sciences 2022, 17, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairil, A.; Irhami; Umar, H. A.; Irmayanti. The effect of long skin soaking in the calcium solution on the quality of rambak crackers from buffalo skin. Theory and practice of meat processing 2023, 8, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatik Baran Mandal, Moumita Dutta. The potential of entomophagy against malnutrition and ensuring food sustainability. African Journal of Biological Sciences 2022, 2022. 4, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premalatha, M.; Abbasi, T.; Abbasi, T.; Abbasi, S.A. Energy-efficient food production to reduce global warming and ecodegradation: The use of edible insects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2011, 4357–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belluco, S.; Losasso, C.; Maggioletti, M.; Alonzi, C.C.; Paoletti, M.G.; Ricci, A. Edible insects in a food safety and nutritional perspective: A critical review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2013, 129, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanboonsong, Yu.; Jamjanya, T.; Durst, P.B. Six-legged livestock: edible insect farming, collection and marketing in Thailand Bangkok. Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations regional office for Asia and the Pacific. 2013. Bangkok 58. https://www.fao.org/3/i3246e/i3246e00.htm.

- Mlcek, J.; Rop, O.; Borkovcova, M.; Bednarova, M. A comprehensive look at the possibilities of edible insects as food in Europe — a review. Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences 2014, 64, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assielou, B.; Due, E.A.; Koff, M.D.; Dabonne, S.; Kouame, P.L. Oryctes owariensis Larvae as Good Alternative Protein Source: Nutritional and Functional Properties. Annual Research, Review in Biology 2015, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Shin, J.T.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y.S.; Kim, Y.W. An overview of the South Korean edible insect food industry: Challenges and future pricing/promotion strategies. Entomological Research 2017, 47, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huis, A.; Oonincx, D.G.A.B. The environmental sustainability of insects as food and feed. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2017, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpold, B.A.; Schlüter, O.K. Potential and challenges of insects as an innovative source for food and feed production. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2013, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayensu, J.; Annan, R.A.; Edusei, A.; Lutterodt, H. Beyond nutrients, health effects of entomophagy: a systematic review. Nutrition and Food Science 2019, 49, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huis, A. Edible insects contributing to food security? Agriculture & Food Security 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murefu, T.R.; Macheka, L.; Musundire, R.; Manditsera, F.A. Safety of wild harvested and reared edible insects: A review. Food Control 2019, 101, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, A.; Berggren, A. Insects as Food — Something for the Future? A report from Future Agriculture 2015, Uppsala: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU). 36 p.

- Kim, T.-K.; Yong, H.I.; Kim, Y.-B.; Kim, H.-W.; Choi, Y.-S. Edible Insects as a Protein Source: A Review of Public Perception, Processing Technology, and Research Trends. Food Science of Animal Resources 2019, 39, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlongwane, Z.T.; Slotow, R.; Munyai, T.C. Nutritional composition of edible insects consumed in Africa: A systematic review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EC) No 852/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the hygiene of foodstuffs. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2004/852/oj (accessed on 7.10.2024).

- EFSA Scientific Committee. Risk profile related to production and consumption of insects as food and feed. EFSA Journal 2015, 13, 4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (4 Juy 2022). Safety of frozen and freeze and dried formulations of the lesser mealworm (Alphitobius diaperinus larva) as a Novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA Journal 2022, 20, 7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahteenmaki-Uutela, A.; Grmelova, N. European law on insects in food and feed. Eur Food Feed Law Review 2016, 11, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Van Peer, M.; Frooninckx, L.; Coudron, C.; Berrens, S.; Álvarez, C.; Deruytter, D.; Verheyen, G.; Van Miert, S. Valorisation Potential of Using Organic Side Streams as Feed for Tenebrio molitor, Acheta domesticus and Locusta migratoria. Insects 2021, 12, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/58 of 5 January 2023 authorising the placing on the market of the frozen, paste, dried and powder forms of Alphitobius diaperinus larvae (lesser mealworm) as a novel food and amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/2470 Available online:.

- R Core Team. 2024. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R. Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Magara, H.J.O.; Niassy, S.; Ayieko, M.A.; Mukundamago, M.; Egonyu, J.P.; Tanga, C.M.; Kimathi, E.K.; Ongere, J.O.; Fiaboe, K.K.M.; Hugel, S.; Orinda, M.A.; Roos, N.; Ekesi, S. Edible Crickets (Orthoptera) Around the World: Distribution, Nutritional Value, and Other Benefits — A Review. Frontiers in Nutrition 2021, 7, 537915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Zh.; Jiang, H. Nutritive Evaluation of Earthworms as Human Food. Future Foods 2017, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunya, B.; Muchenje, V.; Masika, P.J. The Effect of Earthworm Eisenia foetida Meal as a Protein Source on Carcass characteristics and Physico-Chemical Attributes of Broilers. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 2019, 18, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isea-León, F.; Acosta-Balbás, V.; Rial-Betancoutd, L.B.; Medina-Gallardo, A.L.; Mélécony Célestin, B. Evaluation of the Fatty Acid Composition of Earthworm Eisenia tive Lipid Source for Fish Feed. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research 2019, 7, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Bedriñana, J.; Chirinos-Peinado, D.; Sosa-Blas, H. Digestibility, Digestible and Metabolizable Energy of Earthworm Meal (Eisenia Foetida) Included in Two Levels in Guinea Pigs (Cavia Porcellus). Advances in Science, Technology and Engineering Systems Journal 2020, 5, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomsil, N.; Imsoonthornruksa, S.; Gosalawit, Ch.; Ketudat-Cairns, M. Nutritional Values and Functional Properties of House Cricket (Acheta domesticus) and Field Cricket (Gryllus bimaculatus) Food Science and Technology Research 2019, 25, 597–605. 25. [CrossRef]

- Arshanitsa, N.M.; Onishchenko, L.S.; Voronin, V.N. Materials of pathological and epizootological studies on sartan disease in fish. Biological resources and rational use of water bodies in the Vologda region 1989, 293, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ludupova, E.Yu.; Sergeeva, L.A.; Gyrgeshkinova, N.S; Oloeva, E.V.; Badmaeva, V.Ya.; Budasheeva, A.B. A case of occurrence of Haff disease (alimentary-toxic paroxysmal myoglobinuria) in the Republic of Buryatia in the villages of the Pribaikalsky district located near Lake Kotokel. Bulletin of the East Siberian Scientific Center of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences 2009, 67, 92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Arshanitsa, N.M.; Onishchenko, L.S. Gaff disease. Issues of legal regulation in veterinary medicine 2016, 2, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Savchenko, A.A.; Krasnolobova, E.P.; Veremeeva, S.A.; Glazunova, L.A. Pathomorphological changes in the detoxification organs of white mice during an outbreak of "Haff" disease. Bulletin of the Bashkir State Agrarian University 2023, 4, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Content of B vitamins in biomass of the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs, with confidence intervals (with correction for multiple comparisons CI 99%). Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9); Bx2 – substrate enriched with a double dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 1.

Content of B vitamins in biomass of the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs, with confidence intervals (with correction for multiple comparisons CI 99%). Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9); Bx2 – substrate enriched with a double dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 2.

Content of fat-soluble vitamins in biomass of the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs, with confidence intervals (with correction for multiple comparisons CI 99%). Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; FSVx2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 2.

Content of fat-soluble vitamins in biomass of the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs, with confidence intervals (with correction for multiple comparisons CI 99%). Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; FSVx2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 3.

Content of C vitamin in biomass of the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs, with confidence intervals (with correction for multiple comparisons CI 99%). Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; FSVx2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 3.

Content of C vitamin in biomass of the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs, with confidence intervals (with correction for multiple comparisons CI 99%). Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; FSVx2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 4.

Content of macroelements in biomass of the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs, with confidence intervals (with correction for multiple comparisons CI 99%). Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; Chelatex2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 4.

Content of macroelements in biomass of the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs, with confidence intervals (with correction for multiple comparisons CI 99%). Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; Chelatex2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 5.

Microelements content in the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs, with confidence intervals (with correction for multiple comparisons CI 99%). Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; Chelatex2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 5.

Microelements content in the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs, with confidence intervals (with correction for multiple comparisons CI 99%). Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; Chelatex2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 6.

General complex analysis of biomass of the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs, with confidence intervals (with correction for multiple comparisons CI 99.4%). Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C, B7x2_C – substrate enriched with doubled dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; Chelatex2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; FSVx2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9); Bx2 – – substrate enriched with doubled dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 6.

General complex analysis of biomass of the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs, with confidence intervals (with correction for multiple comparisons CI 99.4%). Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C, B7x2_C – substrate enriched with doubled dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; Chelatex2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; FSVx2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9); Bx2 – – substrate enriched with doubled dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 7.

Calorific value of the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs. Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C; B7x2_C – substrate enriched with doubled dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; Chelatex2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; FSVx2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9); Bx2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Figure 7.

Calorific value of the House cricket Acheta domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) and the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) fed on different substrates. Average indexes are given on graphs. Designations: Control – control group; B7_C – substrate enriched with a single dose of vitamins B7 and C; B7x2_C – substrate enriched with doubled dose of vitamins B7 and C; Chelate – substrate enriched with a single dose of mineral complex additive; Chelatex2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of mineral complex additive; FSV – substrate enriched with a single dose of fat-soluble vitamins; FSVx2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of fat-soluble vitamins; B – substrate enriched with a single dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9); Bx2 – substrate enriched with doubled dose of B-complex vitamins (B1, B3 and B9).

Table 1.

Quantity of precursors added to feeding substrate of model species during experiment.

Table 1.

Quantity of precursors added to feeding substrate of model species during experiment.

| Type of precursor |

I stage, singular dose of precursor |

II stage, doubled dose of precursor |

| per 1 kilo of food substrate, mg |

per food portion of crickets, mg |

per food portion of earthworms, mg |

per 1 kilo of food substrate, mg |

per food portion of crickets, mg |

per food portion of earthworms, mg |

| C |

50 |

1.2 |

0.25 |

100 |

2.4 |

0.5 |

| B7 |

25 |

0.6 |

0.125 |

50 |

1.2 |

0.25 |

| minerals(chelate) |

5 |

0.12 |

0.025 |

10 |

0.24 |

0.05 |

| B1 |

2 |

0.048 |

0.01 |

4 |

0.096 |

0.02 |

| B3 |

30 |

0.72 |

0.15 |

60 |

1.44 |

0.3 |

| B9 |

1 |

0.024 |

0.005 |

1 |

0.048 |

0.01 |

| A |

25 |

0.6 |

0.125 |

50 |

1.2 |

0.25 |

| D |

2.5 |

0.06 |

0.0125 |

5 |

0.12 |

0.025 |

| E |

20 |

0.48 |

0.1 |

40 |

0.96 |

0.2 |

| K |

2 |

0.048 |

0.01 |

4 |

0.096 |

0.02 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).