Submitted:

14 October 2024

Posted:

15 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Modern Energy Systems and Their Challenges

1.2. The Role of Smart Grids in Future Energy Infrastructures

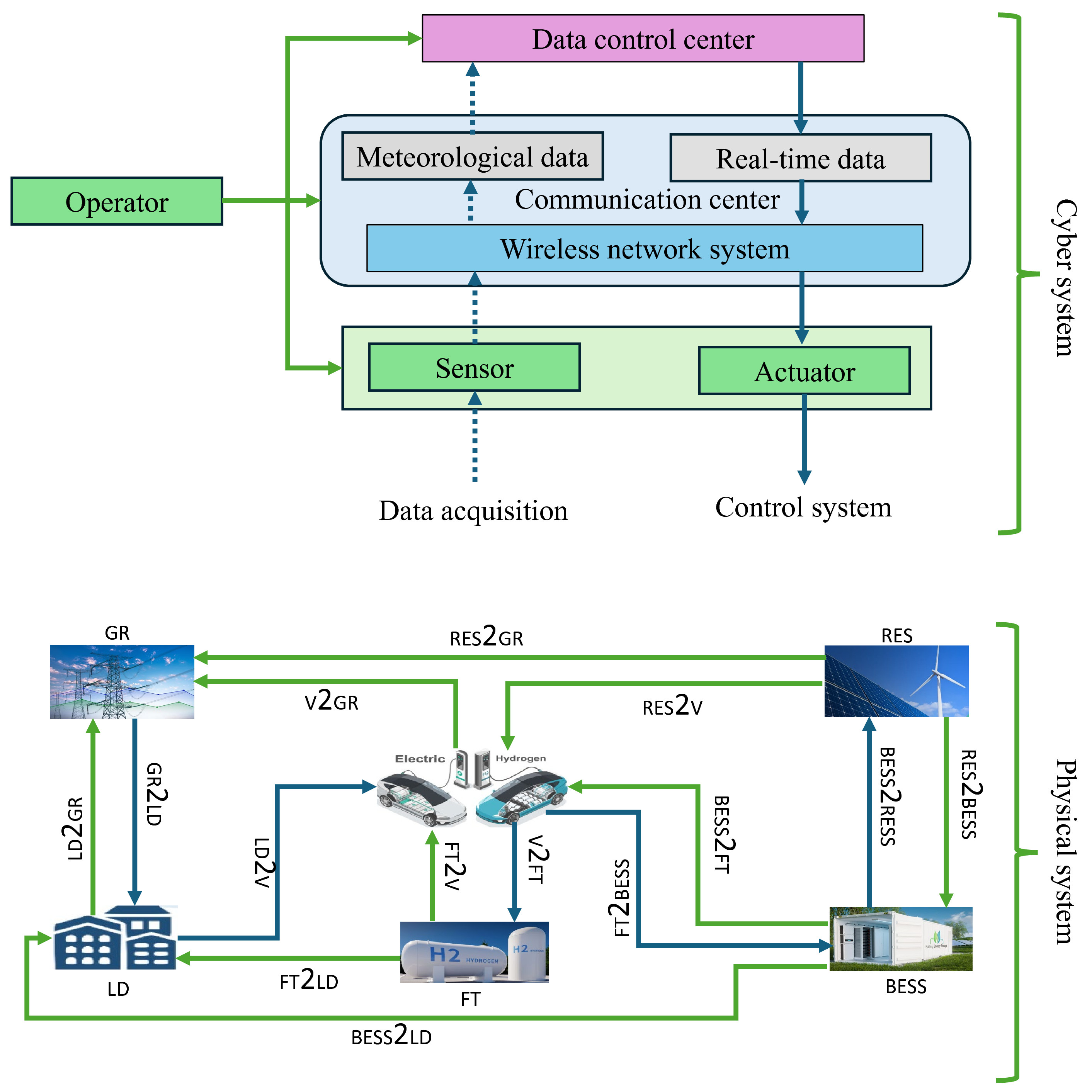

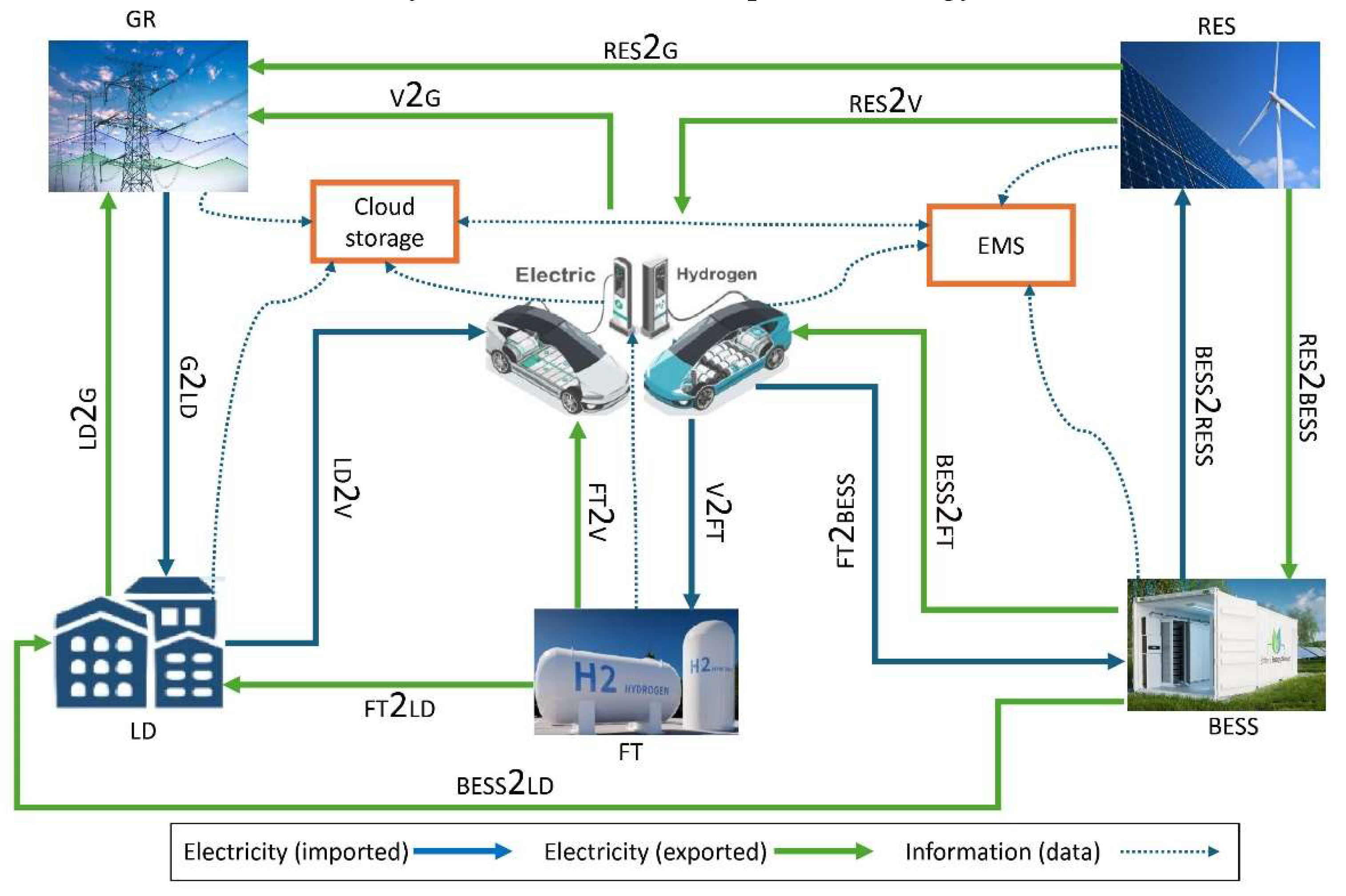

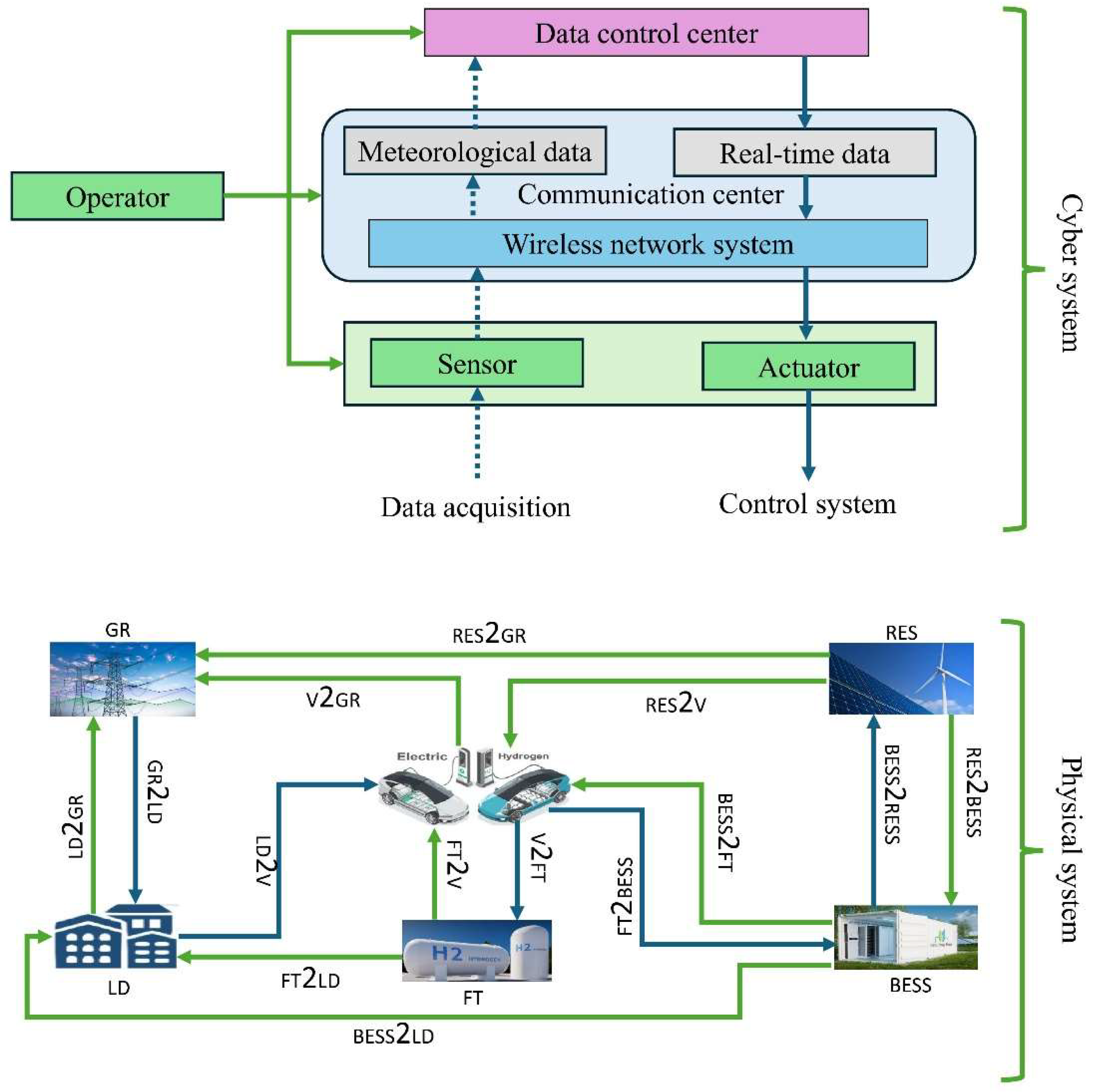

- G2LD: Grid to Load (electricity flowing from the grid to the load)

- LD2G: Load to Grid (electricity being sent from the load back to the grid, possibly through energy storage or local generation)

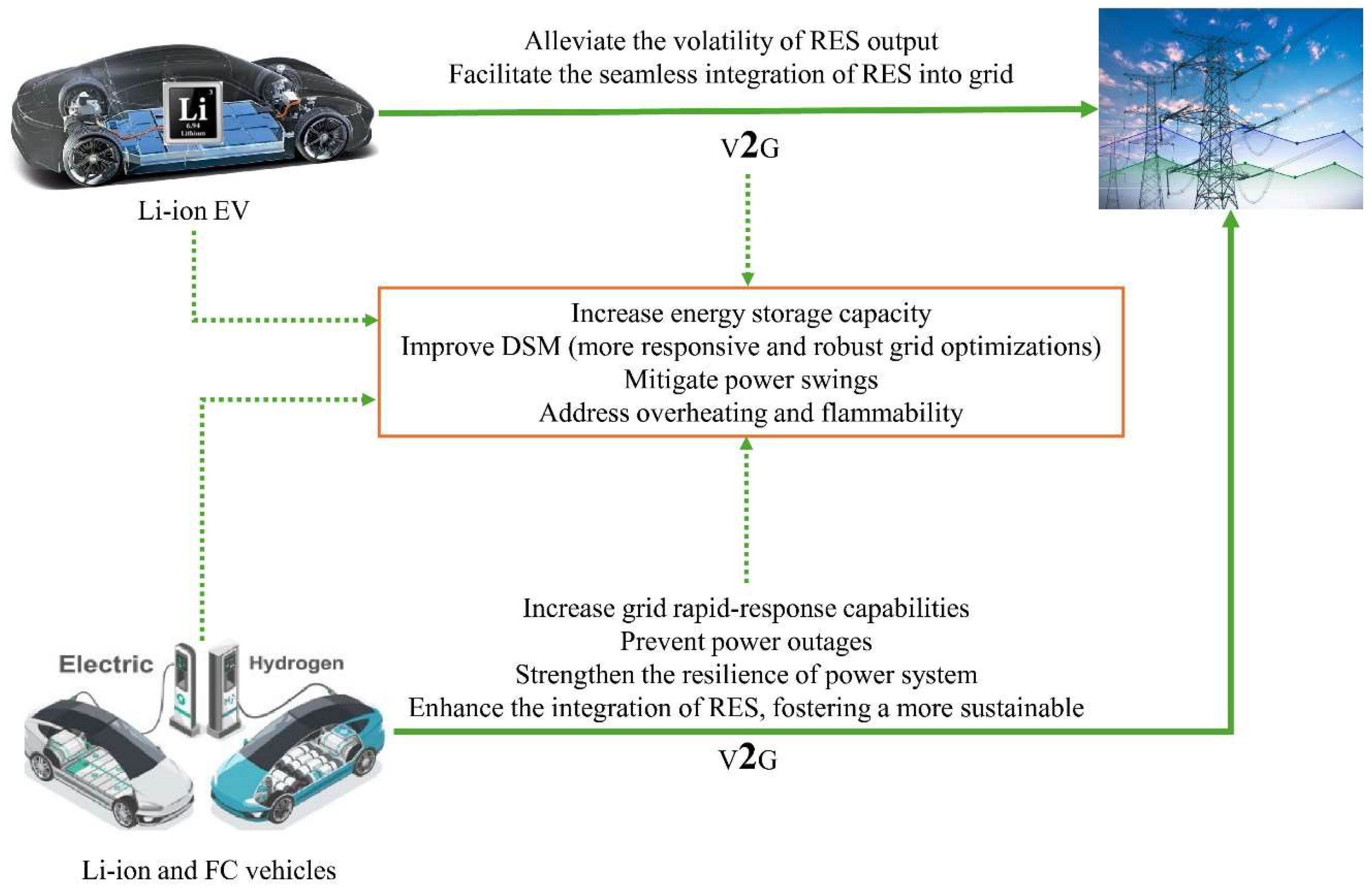

- V2G: Vehicle to Grid (electricity being exported from electric vehicles back to the grid)

- LD2V: Load to Vehicle (electricity being imported from load to electric vehicles for charging)

- RES2G: Renewable Energy Source to Grid (electricity flowing from renewable energy sources to the grid)

- RES2V: Renewable Energy Source to Vehicle (electricity flowing from renewable energy sources to charge vehicles)

- RES2LD: Renewable Energy Source to Load (electricity flowing from renewable energy sources to load directly)

- BESS2LD: Battery Energy Storage System to Load (electricity flowing from battery storage to the load)

- BESS2G: Battery Energy Storage System to Grid (electricity flowing from battery storage back to the grid)

- BESS2RES: Battery Energy Storage System to Renewable Energy Source (for energy balance or storage)

- FT2LD: Fuel Tank to Load (electricity generated from hydrogen used to supply load)

- FT2V: Fuel Tank to Vehicle (hydrogen being used to refuel hydrogen vehicles)

- V2FT: Vehicle to Fuel Tank (hydrogen vehicles potentially sending energy back to hydrogen storage or conversion)

- FT2BESS: Fuel Tank to Battery Energy Storage System (energy generated from hydrogen used to charge batteries)

- BESS2FT: Battery Energy Storage System to Fuel Tank (electricity from battery storage being used to generate hydrogen)

- Cloud Storage: Data storage related to the energy management system and vehicle-to-grid communications, possibly for real-time energy usage data and forecasts.

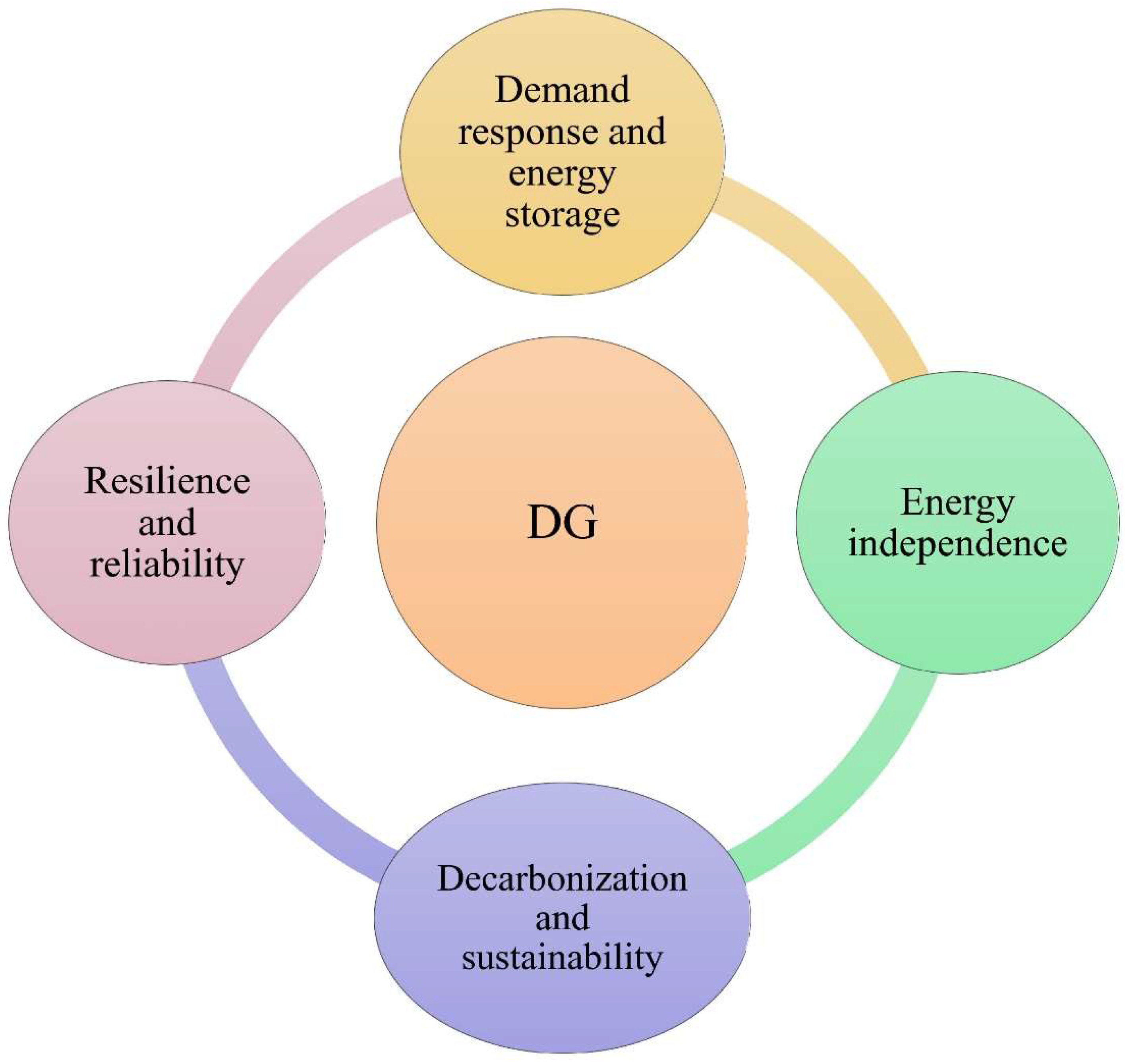

1.3. Distributed Generation: Decentralizing Power Supply

1.4. Contributions of This Paper

- Comprehensive review of SGs and DG: The paper provides an extensive review of the integration of SG technologies, DG, EVs, and ESS in the modern energy systems. It highlights how these technologies create more flexible, resilient, and sustainable energy infrastructures.

- Analysis of energy system optimization: The study explores how the convergence of SGs, DG, and EVs offers opportunities to optimize energy systems. It discusses technologies such as battery storage and FCs that help stabilize grids, reduce transmission losses, and promote the adoption of RES.

- Focus on cybersecurity: One of the paper's key contributions is its in-depth focus on the growing importance of cybersecurity in digitized energy systems. The paper reviews vulnerabilities that arise as energy infrastructures become more interconnected and digital and explore advanced cybersecurity strategies such as AI-driven threat detection, blockchain-based security, and quantum-resistant encryption to protect these systems.

- Exploration of Emerging Technologies: The paper also investigates the role of emerging technologies, including AI and ML, blockchain, and quantum computing, in enhancing the security and performance of modern energy systems. These technologies are presented as key enablers for grid optimization and future-proofing against cyber threats.

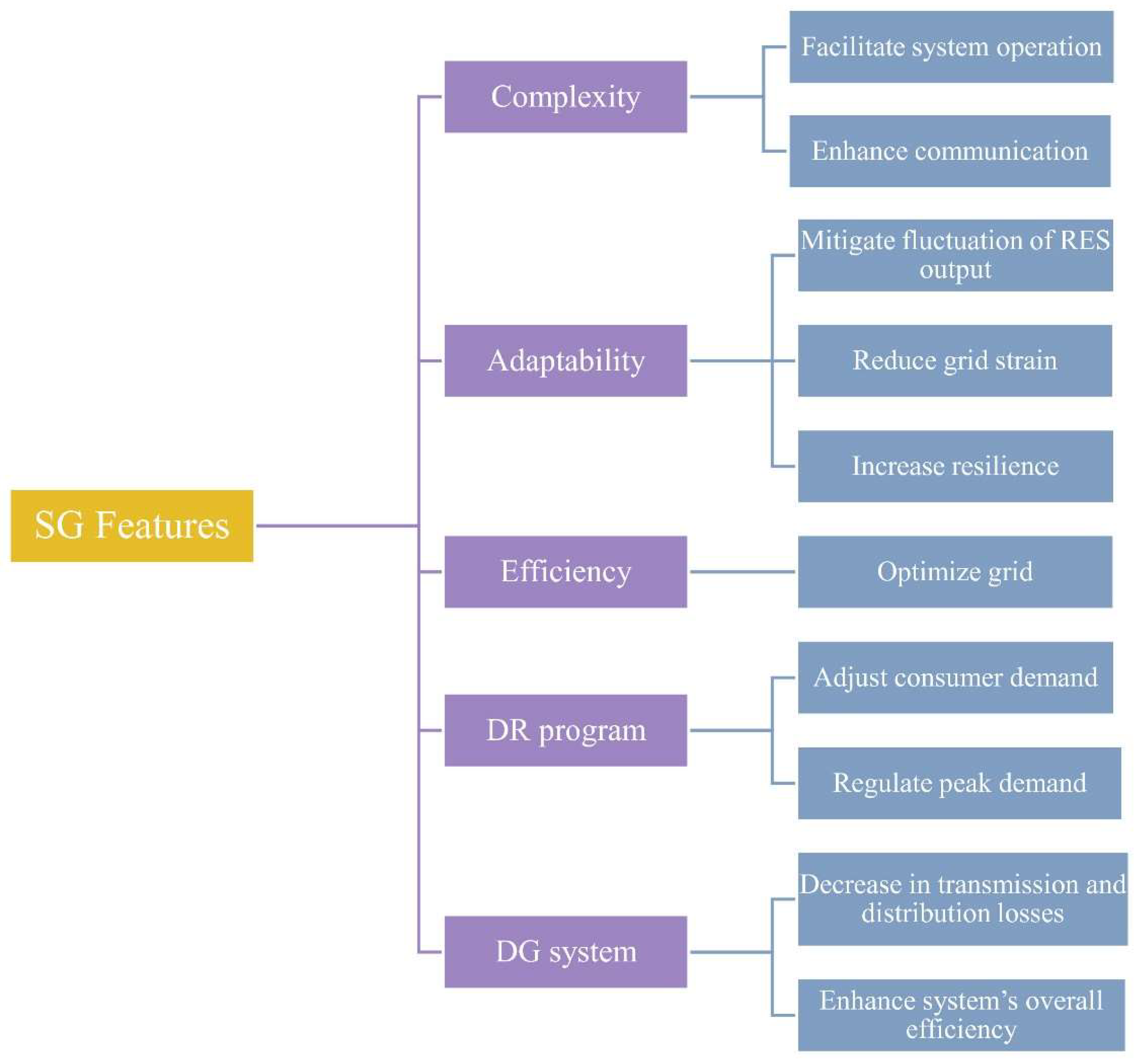

2. Smart Grids: A Catalyst for Energy System Transformation

2.1. Evolution and Key Components of Smart Grids

2.2. Benefits of Integrating Renewable Energy with Smart Grids

- Improved Grid Flexibility: SGs increase adaptability in regulating energy supply and demand. They can dynamically regulate electricity flows by utilizing real-time data from DERs, including PV panels and WTs, thereby maintaining grid stability despite variations in renewable supply [44]. This adaptability diminishes the necessity for traditional backup generation and aids in stabilizing the system among fluctuating RES.

- Enhanced Energy Efficiency: Integrating renewable energy with smart networks improves overall energy efficiency by minimizing transmission losses and optimizing locally generated electricity. Distributed renewable energy technologies, along with rooftop solar panels, produce electricity near consumption sites, hence reducing the necessity for long-distance transmission and limiting energy losses [45]. SGs enhance efficiency by modifying energy consumption patterns based on real-time grid circumstances, so ensuring optimal energy utilization.

- Decarbonization and Sustainability: Transitioning to renewable energy via SG integration is crucial for diminishing GHG emissions and advancing towards a low-carbon energy future. SGs facilitate increased integration of renewable energy into the grid by supplying the necessary infrastructure to manage its unpredictability and intermittency. This aids decarbonization initiatives and enhances global climate objectives by diminishing dependence on fossil fuel-based energy production [46].

- Energy Resilience and Dependability: With SG technology, RES enhances grid resilience by diversifying the energy portfolio and diminishing reliance on a singular energy source. SGs may swiftly redirect electricity from DERs during natural disasters or grid disruptions, assuring a more dependable and resilient energy supply. Furthermore, the capacity of SGs to regulate ESS devices facilitates backup power during outages, hence augmenting grid resilience [47].

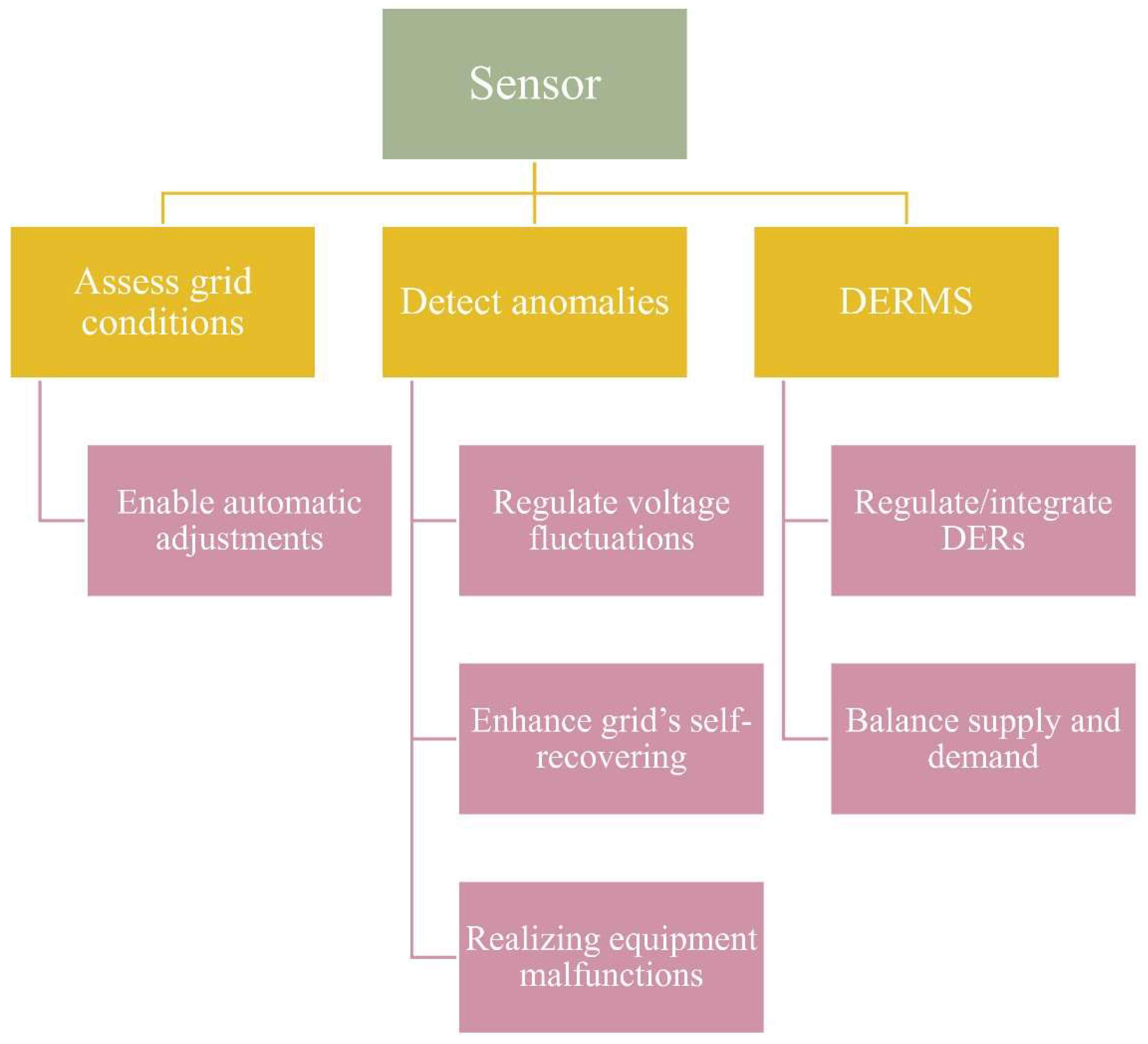

- Advanced Sensors: Sensors installed across the grid deliver real-time data on voltage levels, power flows, and system performance. They can identify anomalies, such as voltage fluctuations or equipment malfunctions, and notify operators of possible problems before they intensify. These sensors are crucial for the self-recovering functions of SGs, enabling the system to detect defects and redirect electricity to reduce downtime autonomously [48].

- Smart meters are essential components of SG infrastructure, facilitating bidirectional communication between consumers and utilities. These meters not only record energy consumption but also transmit real-time data to grid operators, facilitating dynamic pricing models, DR initiatives, and enhanced load management. Consumers can benefit from smart meters by obtaining enhanced control over their energy consumption, receiving comprehensive feedback on their usage patterns, and modifying their consumption to decrease expenses [49].

- Two-Way Communication: Two-way communication is a defining characteristic of SG systems, facilitating real-time data interchange across the GR and users. This connection enables grid operators to dynamically adapt to fluctuations in energy demand, optimize energy distribution, and integrate RES more efficiently. Integrating all energy system components facilitates bidirectional communication, ensuring real-time balance between supply and demand, averting interruptions and improving overall grid efficiency [50].

- Grid Optimization: These technologies collectively provide real-time grid optimization, guaranteeing maximal efficiency in power generation, distribution, and consumption. Through constant monitoring of grid conditions and the corresponding adjustment of operations, SGs can minimize transmission losses, avert energy waste, and enhance the integration of RES. This results in a more sustainable, dependable, and economical energy system [51,52].

3. Distributed Generation and Its Impact on Grid Stability

3.1. Integrating Solar, Wind, and Other RES

3.2. DG’s Role in Supporting Decentralized Energy Management

- Energy Independence: A principal advantage of DG is its capacity to enhance energy autonomy for local communities, enterprises, or people. By producing electricity on-site or in proximity, users depend less on the central grid. This is especially beneficial in rural regions with restricted grid access or during natural catastrophes when the centralized grid may be disrupted [57].

- Resilience and Reliability: DG systems, particularly when integrated with MGs, can enhance the resilience of energy systems. MGs are localized electrical networks capable of functioning autonomously from the primary grid. During a grid outage or blackout, MGs powered by DG can maintain energy supply to critical loads, including hospitals, emergency services, and essential enterprises. This skill is essential for improving the reliability of electricity supply amid escalating climate-related disruptions and grid vulnerability [58].

- Demand Response and Energy Storage: DG and ESS technologies significantly contribute to DR tactics. DR schemes incentivize consumers to alter their energy consumption during peak demand periods or when grid stability is at risk. By generating or storing their electricity, DG users can diminish their reliance on the primary grid and contribute to balancing the overall supply-demand dynamic. This action not only aids in stabilizing the grid but also alleviates peak loads, potentially postponing or eliminating the necessity for expensive grid infrastructure enhancements [59].

- Decarbonization and Sustainability: DG aids decarbonization initiatives by advocating for adopting clean energy sources. The shift to renewable DG mitigates GHG emissions by replacing fossil fuel-based power generation. Furthermore, DG systems that utilize local resources, such as solar or wind, enhance the sustainability of energy supply by diminishing reliance on imported fuels and mitigating the environmental impact of extensive energy infrastructure [60].

4. Energy Storage Solutions: Battery and Fuel Cell Technologies

4.1 Advances in Battery Technologies for Grid and EV Applications

4.2 Fuel Cells as an Alternative for Long-Duration Energy Storage

4.3 Impact of Energy Storage on Grid Flexibility and Reliability

5. Electric Vehicles as Dynamic Energy Resources

5.1. V2G Technologies and Their Role in Grid Stabilization

5.2. EVs: DR and Load Management Opportunities

5.3. Infrastructure Requirements for EV Integration into SGs

- Charging Stations: A comprehensive and dependable network of intelligent charging stations is crucial to fully exploit EVs' capabilities as dynamic energy resources. These stations must be equipped to charge EVs and facilitate bidirectional energy transfers to support V2G technologies. Furthermore, charging stations must be optimally situated to conveniently charge EVs at residences, businesses, or public areas. Fast-charging stations are essential for minimizing charge durations and increasing flexibility for EV users [82].

- Communication Networks: SGs necessitate a resilient communication infrastructure to enable real-time data transmission among EVs, grid operators, and utility companies. Advanced metering infrastructure (AMI) and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies are crucial for facilitating the seamless integration of EVs with the grid. These systems enable grid operators to observe EV charging and discharging trends, regulate energy flows, and react to grid circumstances instantaneously. Efficient and dependable communication networks are essential for effectively integrating V2G technologies and other SG applications [83].

- Energy Management Systems: Effective EMSs are essential for maximizing the charging and discharging of EVs inside smart networks. EMS technologies facilitate dynamic management of energy flows, enabling grid operators to prioritize energy allocation according to grid demand, renewable generation, and EV availability. EMS platforms enhance grid efficiency by including EVs in comprehensive DR and load management methods while simultaneously addressing the energy requirements of EV owners [84].

6. Cybersecurity in SGs and DG

- Power Flows: Power generated from renewable energy sources (such as wind and solar) is transmitted to the grid and distributed to customers. Energy is also sent to and from a BESS and electric/hydrogen vehicles, enabling energy flexibility and resilience in the grid.

- Data Flows: Data flows are managed through a network of routers and gateways, which transmit real-time operational information between key grid components, such as renewable energy generation, battery storage, and customers. The data is essential for optimizing grid operations, including balancing supply and demand, ensuring stability, and integrating DERs.

- Service Provider and Operations: Service providers and operational systems receive data from the grid to monitor, analyze, and manage the system's performance. This helps in demand response, predictive maintenance, and overall grid optimization.

6.1. Emerging Cybersecurity Threats in Energy Systems

- Data Breaches: Implementing AMI and smart meters generates and transmits substantial quantities of data among utilities, consumers, and grid operators. This data contains sensitive information regarding consumer usage patterns, which, if breached, could result in privacy infringements or exploit weaknesses in grid management systems. Data breaches provide a substantial threat, as nefarious individuals may acquire essential operational information that might be utilized to undermine energy services or implement more advanced assaults [87].

- Malware: Malware assaults entail the penetration of energy systems by malicious software intended to incapacitate or compromise operational technology (OT) systems. A notable instance is the BlackEnergy malware assault on the Ukrainian power grid in 2015, which resulted in extensive power disruptions by penetrating the control systems of electricity distribution companies. Analogous assaults on SGs may result in severe service interruptions by undermining control systems that regulate electricity distribution across decentralized generation networks [88].

- Denial-of-Service Attacks: In a DoS attack, cybercriminals inundate network systems with excessive traffic, incapacitating them from addressing legitimate requests. Such attacks might severely compromise SG control centers, which depend on continuous connection with grid elements such as smart meters and DERs. By saturating these communication channels, DoS attacks may inhibit grid controllers from monitoring or regulating energy flows, potentially resulting in extensive outages [89].

- Ransomware: The proliferation of ransomware in vital infrastructure sectors has also impacted the energy sector. Ransomware attacks entail the encryption of essential systems or data, making them inoperable until a ransom is remitted. Within the framework of a SG, such an assault might disrupt grid operations, leading to significant economic and societal consequences. The 2021 Colonial Pipeline ransomware assault showed the catastrophic impact such incidents may inflict on essential infrastructure, leading to major fuel shortages and financial losses. An analogous assault on a SG could yield similarly catastrophic outcomes [90].

- Supply Chain Vulnerabilities: The intricate supply chains associated with the production and deployment of SG technology provide a notable risk. Supply chain assaults entail integrating harmful components or software at multiple phases of the technology manufacturing and distribution process. Such attacks may be challenging to identify and can jeopardize the security of entire systems by introducing weaknesses before the deployment of the equipment. Ensuring the supply chain protection for SG technologies is a paramount problem as assaulters increasingly focus on upstream suppliers [91].

6.2. Challenges of Securing Interconnected Energy Networks

- Decentralization and Distributed Generation: The decentralization of energy production, facilitated by the emergence of DG systems such as PV panels, WTs, and energy storage units, enhances the complexity of grid security. Every DG unit represents a potential vulnerability to hackers, and safeguarding the extensive network of devices, communication channels, and control systems that oversee these units poses a considerable problem. In contrast to centralized power plants, which a singular, strong security perimeter may safeguard, DG systems necessitate a decentralized cybersecurity strategy wherein each individual node must be secured [87].

- Interoperability with Legacy Technologies: A significant problem in safeguarding SGs is the compatibility between legacy and contemporary technologies. Numerous utilities continue to depend on conventional grid infrastructure not designed initially with cybersecurity considerations. Integrating legacy systems with contemporary SG technologies introduces dangers from disparities in security standards, software compatibility, and operational procedures. Maintaining secure communication and control across many systems without jeopardizing grid stability or performance presents a significant problem [92].

- Real-time Operations and Availability: The instantaneous nature of grid operations poses an additional challenge. SGs and DERs necessitate immediate communication and decision-making to equilibrate energy supply and demand, regulate voltage levels, and stabilize the grid. Delays resulting from security procedures—such as authentication or encryption—may result in operational inefficiencies or even power outages. Consequently, cybersecurity systems must be designed to deliver robust protection while maintaining the availability and performance of the grid [93].

- Human Factor and Insider Threats: The human element continues to provide a significant barrier in cybersecurity. Insider threats, whether stemming from malicious intent or inadvertent mistakes, present considerable risks to energy systems. Employees possessing access to essential systems may unintentionally facilitate cyberattacks via phishing attempts, inadequate passwords, or misconfigured systems. Furthermore, dissatisfied personnel or contractors with knowledge of grid operations and access to control systems might inflict significant disruptions if not adequately managed. Training all people in cybersecurity best practices and implementing appropriate access controls to mitigate these threats is essential [94].

6.3. Strategies for Enhancing Cybersecurity in Digitized Grids

- Robust Encryption and Authentication: Implementing stringent encryption and authentication procedures is a highly effective method of safeguarding SG communication channels against cyberattacks. By encrypting data during its transmission between smart meters, substations, and control centres, grid operators may safeguard important operational information from illegal access. Multifactor authentication (MFA) is a crucial security measure, guaranteeing that only authorized individuals can access vital systems. Public key infrastructure (PKI) and digital certificates can be utilized to authenticate devices communicating within the grid [97].

- AI for Threat Detection: AI is increasingly vital for identifying and addressing cyber risks within SGs. By analyzing extensive data produced by grid operations, AI systems can detect real-time irregularities that may signify a cyberattack. AI algorithms can identify behavioural patterns that diverge from the norm, signalling possible hazards before they escalate into more substantial disruptions. AI-driven threat detection improves the capacity to address emerging and dynamic attack vectors, facilitating more adaptable and proactive cybersecurity strategies [98].

- Resilience and Redundancy in Grid Architecture: Incorporating resilience into the architecture of SGs is essential for alleviating the effects of cyberattacks. This can be accomplished by redundancy in essential grid components and self-repairing functionalities. Redundant systems guarantee that if one grid component fails, other components can maintain operation, hence averting complete system failure. Integrating sophisticated sensors and automation, self-recovering grids may autonomously identify and isolate faults, reinstating electricity and safeguarding the larger grid from cascading failures [99].

- Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA): Implementing a ZTA entails assuming that any device, user, and system within the SG may be hacked until validated. This method necessitates ongoing verification and surveillance of all activities conducted within the grid. ZTAs enhance security by eliminating implicit trust, hence diminishing the danger of unwanted access and insider threats [100].

- Worldwide Collaboration and Standards: Due to the global characteristics of energy systems and supply chains, worldwide cooperation is essential for formulating cybersecurity standards and best practices. Cooperative initiatives involving governments, utilities, and technology providers can facilitate the establishment of uniform security measures, sharing threat intelligence, and formulating coordinated responses to cyber-attacks. Entities like the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) play a crucial role in formulating recommendations for the security of SGs and DG systems [101].

7. Emerging Technologies for Grid Optimization

7.1. The Role of AI in Grid Security

- Predictive Maintenance and Fault Detection: AI algorithms may evaluate extensive data from sensors integrated into SGs to identify anomalies that may signify probable equipment failure or operational inefficiency. AI-driven predictive maintenance anticipates faults prior to their occurrence, hence minimizing downtime and maintenance expenses while enhancing overall grid reliability. AI models can be trained to identify patterns that precede equipment failures, enabling utilities to implement preventive measures to avert expensive interruptions [81,106,107].

- Automated Threat Detection: As cyberattacks on energy systems grow increasingly complex, AI is essential in cybersecurity for real-time identification and response to threats. AI algorithms can identify anomalous activity patterns that may indicate a cyber intrusion, like abrupt increases in the data flow, unauthorized access attempts, or atypical behaviour from grid-connected devices. By analyzing historical instances, AI systems might enhance their threat detection capacities over time, allowing grid operators to react more promptly to emergent cyber threats [108].

- Grid Load Forecasting and Energy Demand Management: AI enhances load forecasting and regulates energy demand. AI algorithms can evaluate previous grid data and meteorological circumstances to forecast future energy consumption patterns with improved precision. These projections enable grid managers to enhance energy distribution, distribute resources more efficiently, and minimize energy waste. In renewable energy systems, AI can predict solar and wind generation patterns, enabling grid operators to control the fluctuation of RES effectively [109,110].

7.2. Blockchain for Securing Distributed Energy Transactions

- Decentralized Energy Markets: In decentralized energy markets, prosumers—individuals or entities that simultaneously produce and consume energy—can engage in direct transactions of electricity with one another using blockchain-enabled platforms. These platforms obviate the necessity for centralized intermediaries, such as utility corporations, by facilitating P2P energy transactions recorded on a blockchain. Every transaction is authenticated using a consensus method, guaranteeing that all participants can access a safe, transparent, and immutable record [111]. This decentralized method enhances energy trading efficiency, diminishes transaction expenses, and encourages increased involvement in renewable energy generation.

- Ensuring the Security of Distributed Energy Systems: Blockchain is crucial in safeguarding distributed energy systems by offering a robust and immutable framework for documenting energy transactions and regulating access to grid resources. In a blockchain-enabled grid, each transaction between DERs and the grid is cryptographically secured, thereby diminishing the possibility of fraud or tampering. Moreover, smart contracts self-executing agreements with stipulations encoded directly into software—can facilitate the automation of energy trading procedures and guarantee that specified criteria are satisfied before exchanging energy [112].

- Improving Grid Transparency and Efficiency: Blockchain technology ensures exceptional transparency in energy systems by documenting all transactions in a public or restricted-access ledger available to authorized entities. This transparency enhances confidence among market participants and enables regulators to oversee energy markets more efficiently. Moreover, blockchain might enhance grid efficiency by facilitating automated DR systems, allowing energy consumption to be modified according to real-time pricing signals. This adaptability is particularly advantageous in reconciling supply and demand in grids with significant renewable energy integration [113].

7.3. Leveraging Advanced Data Analytics for Grid Management

- Real-time Grid Surveillance and Visualization: Sophisticated data analytics provide real-time observation of grid conditions, offering grid operators actionable knowledge regarding the energy system's state. Analytics platforms can pinpoint grid regions experiencing congestion, voltage imbalances, or equipment breakdowns by displaying data from several sensors. This real-time insight facilitates expedited responses to operational challenges, minimizing downtime and enhancing overall grid resilience [40].

- Enhancing DER Management: The increasing prevalence of DG and RES presents a significant challenge for grid operators in managing the variability of these resources. Advanced data analytics offer instruments for optimizing the allocation of DERs, guaranteeing that energy is distributed precisely when and where it is most required. Analytics solutions can predict solar or wind generation utilizing weather data and historical trends, enabling operators to prepare more effectively for variations in energy supply and demand [114].

- Predictive Analytics in Asset Management: Predictive analytics employs AI models and statistical methods to forecast the potential failure of grid assets, including transformers and energy storage devices. Through the analysis of historical performance data, predictive models can anticipate the condition of grid infrastructure, facilitating condition-based maintenance and diminishing the probability of unforeseen failures. This proactive asset management strategy prolongs the lifespan of essential grid components and decreases maintenance expenses [115].

- Energy Efficiency and DSM: Advanced data analytics are essential for enhancing energy efficiency by pinpointing opportunities for DSM. By analyzing consumption data from smart meters, utilities can identify opportunities for enhancing energy efficiency, such as optimizing heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems in commercial structures or encouraging consumers to alter their energy usage to off-peak periods. These insights facilitate a reduction in overall energy usage, decrease costs for users, and alleviate the strain on the grid during peak demand periods [116].

9. Case Studies: Global Perspectives on Integration

9.1. Successful Implementation of SGs and DG Systems Worldwide

- United States: The U.S. has led in SG advancement, notably through the SG Investment Grant (SGIG) program, which allocated $4.5 billion for grid modernization. Incorporating AMI and DG systems, particularly solar energy, has resulted in substantial enhancements in grid efficiency and the integration of renewable energy. The Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) exemplifies the implementation of SG technologies to monitor grid performance in real-time, enhance outage management, and facilitate the integration of solar energy. The efficacy of PG&E's SG and DG integration initiatives illustrates the merit of governmental investment in grid modernization and underscores the significance of utilizing public-private partnerships [118,119,120].

- Germany is a global leader in DG, notably with its Energiewende plan, which seeks to attain 80% renewable energy by 2050. The nation has effectively incorporated substantial quantities of solar and wind energy into its system through the implementation of decentralized energy models and the improvement of grid flexibility. The Smart Region Pellworm project is significant, as it is an island characterized by a substantial integration of solar and wind energy. Incorporating energy storage and SG technology has allowed the island to equilibrate supply and demand in real-time, diminishing its dependence on fossil fuels and exemplifying renewable energy integration [100]. Germany's strategy for SG implementation highlights the significance of adaptable ESS technologies to facilitate elevated renewable generation levels [121,122].

- Japan: Following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011, Japan altered its energy policy to prioritize renewable energy and SGs. The nation has executed MG initiatives, including the Sendai MG, which employs DG and energy storage devices to improve resilience against natural catastrophes. This project was developed to sustain power for essential facilities during grid failures, demonstrating the capabilities of SGs and DG systems in disaster recovery. Japan's experience underscores the significance of MGs in enhancing energy security and reliability, especially in areas susceptible to natural disasters [123,124].

- Denmark: Denmark is a leader in implementing SG and DG systems, especially in integrating wind energy. As of 2021, more than 50% of Denmark's electricity is derived from wind power, and the nation has implemented sophisticated SG systems to regulate this fluctuating energy source. The Cell Controller Pilot Project is a pivotal endeavour in Denmark, designed to incorporate wind energy and CHP plants into the grid using advanced control mechanisms. This study has illustrated how distributed control systems may equilibrate fluctuating energy supply and demand, facilitating the efficient utilization of renewable energy while preserving grid stability [125,126].

9.2. Regional Variations in Cybersecurity Approaches for Energy Systems

- Europe: European nations, especially those inside the European Union (EU), have implemented extensive cybersecurity rules for vital infrastructure, including energy systems. Ref. [103] establishes fundamental security criteria for critical service operators, such as energy firms, and enforces incident reporting and risk management protocols. Countries like Germany have implemented further measures to enhance the security of their SGs by mandating utilities to adopt advanced encryption technologies and perform regular security assessments. The Federal Office for Information Security, Germany's national cybersecurity organization, is essential in establishing cybersecurity standards for energy systems, exemplifying the nation's proactive strategy in safeguarding critical infrastructure [127,128].

- United States: The United States' strategy for energy cybersecurity is influenced by a blend of federal and state policies. The North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) establishes cybersecurity guidelines for the electricity sector, notably the Critical Infrastructure Protection (CIP) standards, which delineate rules for safeguarding bulk power networks against intrusions. The U.S. prioritizes public-private partnerships via initiatives such as the Electricity Subsector Coordinating Council (ESCC), which promotes information exchange between governmental entities and utility firms [129,130]. The decentralized structure of the U.S. energy sector, comprising multiple commercial utilities and regulatory bodies, can hinder the establishment of common cybersecurity requirements.

- Asia-Pacific: In Asia-Pacific, nations such as Japan and South Korea have concentrated on establishing comprehensive cybersecurity frameworks to safeguard their SGs and DG systems. Japan has implemented rigorous cybersecurity protocols for energy infrastructure after the Fukushima accident. The Cybersecurity Strategy Headquarters in Japan supervises safeguarding vital infrastructure, including energy systems, by collaborating with industry stakeholders and advocating for using AI in threat detection. Simultaneously, South Korea has invested substantially in SG security by initiating the K-SG Cybersecurity Program to protect its advanced energy systems from possible cyber assaults [131,132].

- The Middle East: The Middle East is progressively investing in SG technologies; nevertheless, cybersecurity measures are inconsistent. Countries such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia have advanced in establishing cybersecurity guidelines for their energy sectors. The UAE's Cybersecurity Strategy seeks to bolster key infrastructure security, particularly energy systems, through capacity building, incident response, and public-private collaboration. Nonetheless, the region encounters distinct problems, including geopolitical tensions that elevate the probability of assaults on energy infrastructure [133,134].

9.3 Lessons from Leading SG and Distributed Energy Projects

- Significance of Public-commercial Partnerships: The efficacy of SG and DG initiatives frequently depends on the cooperation between governmental bodies and commercial organizations. Public financing and regulatory assistance have been crucial in promoting SG technologies in the United States and Germany. These collaborations mitigate financial and technological obstacles linked to extensive grid upgrading initiatives.

- Integration of Energy Storage: Significant incorporation of renewable energy necessitates efficient ESSs to address unpredictability and ensure grid stability. Case studies from Denmark and Japan illustrate the essential function of storage in facilitating the retention and utilization of surplus renewable energy when required. This lesson emphasizes the significance of integrating energy storage into SG systems to enhance reliability and resilience.

- Cybersecurity by Design: Given the continual evolution of cyber threats, it is evident that cybersecurity must be incorporated into the design of SGs from the beginning. Regions such as Europe and Japan, where cybersecurity is regarded as a fundamental component of energy infrastructure, offer examples of how other nations may emphasize security. These instances underscore the necessity of formulating cybersecurity guidelines in conjunction with SG technology.

- Flexibility in Grid Operations: Flexibility is essential for controlling the dynamic characteristics of DG systems. Initiatives such as Denmark’s Cell Controller Pilot Project demonstrate that decentralized control systems can enhance grid stability via real-time balancing of variable RES. This lesson is especially pertinent for areas with elevated wind and solar energy, where adaptable grid management is crucial for integrating renewables.

10. Challenges and Opportunities in Future Energy Systems

10.1. Overcoming Grid Congestion and Bottlenecks

- Limitations of Transmission Infrastructure: The inadequate capacity of the current transmission infrastructure is a significant cause of grid congestion. Renewable energy generation frequently occurs in isolated locations (e.g., offshore wind farms or extensive solar installations in rural areas), necessitating the transmission infrastructure to transport electricity across considerable distances to urban centers, where demand is greatest. Insufficient transmission infrastructure can generate bottlenecks, obstructing renewable energy from reaching consumers and resulting in curtailment (i.e., the reduction of renewable energy production to prevent system overload) [136].

- Energy Storage as a Solution: A significant opportunity to mitigate grid congestion is implementing ESS technology. By accumulating surplus electricity during periods of elevated generation, such as during sunny or windy conditions, storage devices can mitigate the strain on transmission networks and discharge the stored energy when demand escalates. BESS, pumped hydro storage (PHS) and hydrogen storage (HS) are essential for mitigating supply-demand discrepancies and alleviating grid congestion [137]. Utilizing DR algorithms enables grid operators to modify consumption patterns during peak generation periods, alleviating congestion.

- Enhancing Transmission Networks: In addition to storage alternatives, enhancing transmission networks with SG technology can markedly alleviate congestion. SGs provide real-time surveillance of energy flows, employing sophisticated sensors and automated control systems to regulate electricity distribution dynamically. These technologies enhance grid performance by allocating electricity to areas of greatest need and managing supply and demand changes more efficiently [138].

10.2. Navigating Regulatory Barriers in the Integration of DG and EVs

- Interconnection Standards: A key regulatory problem in integrating DG systems is clear and consistent interconnection requirements. These standards regulate the connection of DERs to the grid. Inconsistent or excessively intricate connectivity requirements might impede project development and deter investment in DG systems. Optimizing interconnection procedures and establishing standardized protocols can markedly diminish entrance barriers for prosumers and small-scale renewable energy producers [107].

- Incentives for DG: Regulatory frameworks must adapt to offer suitable incentives for implementing DG systems. In numerous areas, obsolete electricity tariffs and net metering rules must sufficiently remunerate prosumers for the energy they produce, resulting in financial disincentives for adopting renewable technologies. Policymakers can resolve this issue by revising tariffs to represent the value that DG systems accurately contribute to the grid, including reducing transmission losses and improving grid resilience. Feed-in tariffs (FiTs) and renewable energy certificates (RECs) offer financial incentives to energy companies that supply renewable electricity to the grid [139].

- EV Integration: The swift expansion of EVs presents supplementary regulatory problems, especially concerning charging infrastructure and V2G technology. In some areas, laws governing the installation of charging stations, particularly public charging networks, are inconsistent or insufficient, hindering the extensive adoption of EVs. Governments can enhance EV integration by providing subsidies for charging infrastructure development, establishing standardized charging protocols, and promoting grid-interactive charging technologies such as V2G, which allow EVs to function as energy storage assets for the grid [130].

- Market Access for Prosumers: Regulatory frameworks must facilitate increased prosumer participation in energy markets. Prosumers—entities that produce electricity—encounter obstacles in selling surplus energy to the grid because of restrictive market frameworks. P2P energy trading platforms, facilitated by technology such as blockchain, provide a novel solution to this issue by allowing prosumers to transact electricity directly with other customers, circumventing conventional utilities. Nonetheless, these platforms necessitate conducive legislative frameworks facilitating decentralized energy trade [140].

10.3. Enhancing Interoperability Between Different Energy Systems

- Standardization of Communication Protocols: A primary obstacle in achieving interoperability is the absence of established communication protocols for SG components and DERs. Devices like smart meters, solar inverters, EV chargers, and ESSs sometimes employ disparate communication standards, complicating the ability of grid operators to monitor and manage these resources cohesively. Establishing and implementing international communication standards, such as Open Automated Demand Response (OpenADR) and IEC 61850, can enhance interoperability among energy systems and guarantee the successful operation of devices from various manufacturers [141].

- Data Management and Cybersecurity: The escalating digitization of energy systems has resulted in a significant surge in the volume of data produced by SGs, IoT devices, and DERs. Effectively managing this data while ensuring cybersecurity is a significant problem for improving interoperability. Advanced data analytics tools assist grid operators in processing and analyzing data in real-time, facilitating more efficient grid management and decision-making. The development of linked devices expands the attack surface for cyber threats, requiring stringent cybersecurity measures to safeguard data integrity and grid operations [142,143].

- Integrated EMS: Integrated EMSs are crucial for coordinating the operation of various energy resources to address the complexity of modern energy systems. EMSs utilize real-time data to enhance energy generation, storage, and consumption across many assets, including PV panels, WTs, EVs, and BESSs. By consolidating these resources into a unified platform, grid operators may more effectively balance supply and demand, augment grid resilience, and decrease energy expenses. EMS platforms facilitate dynamic engagement in energy markets, permitting distributed resources to react instantaneously to price signals or grid conditions [134].

- Grid Flexibility and Resource Coordination: Incorporating renewable energy, DG, and EVs into the grid necessitates improved flexibility to manage variable energy production and changing demand. The interoperability of these systems facilitates enhanced resource coordination, permitting grid managers to react to fluctuations in supply and demand instantaneously. During elevated renewable energy generation moments, grid operators can direct EVs to charge or employ distributed storage to capture surplus electricity. During periods of peak demand, EVs with V2G technology can release stored energy back into the grid, serving as a crucial resource for grid stability [144].

11. Future Directions for Securing and Optimizing Energy Systems

11.1. Predicting the Next Wave of Innovation in SGs and Cybersecurity

- AI-Driven Automation and Autonomous Grids: The future of SGs will be shaped by the deployment of AI-driven automation, enabling the grid to operate autonomously with minimal human intervention. Autonomous grids can automatically adjust to fluctuations in supply and demand, manage DG systems, and respond to grid emergencies in real-time. AI algorithms will play a key role in predictive maintenance, identifying potential failures before they occur, and enhancing overall grid reliability. Furthermore, self-recovering grids, equipped with advanced sensors and AI, will be able to isolate faults and restore power without human intervention, reducing the duration of outages and improving resilience.

- Enhanced Cybersecurity with Quantum Computing: As cyberattacks become more sophisticated, future cybersecurity innovations will likely involve using quantum computing and quantum cryptography to protect critical infrastructure. Quantum cryptography offers the potential to create unbreakable encryption, which could safeguard energy systems from cyber intrusions. This technology will be crucial as energy grids become more interconnected and reliant on digital communication. Post-quantum cryptography solutions will also be needed to defend against the emerging threats of quantum computing, ensuring that grid communications remain secure even as computational power increases exponentially.

- Blockchain and Decentralized Security Protocols: Blockchain technology is poised to play a significant role in future energy systems, particularly in enhancing the security of distributed energy transactions. Blockchain provides a tamper-proof ledger that can be used to securely track energy generation, distribution, and consumption across decentralized energy systems. Future innovations will likely involve the integration of blockchain with smart contracts, which will automate energy transactions and ensure that energy flows are secure and transparent. This will be particularly important for managing P2P energy trading, where prosumers (both producers and consumers of energy) exchange electricity directly.

11.2. Preparing for the Expansion of Distributed Generation and Electric Mobility

- Scalable Distributed Generation Systems: The expansion of DG systems, including rooftop PVs, WTs, and small-scale hydropower, will require scalable solutions that can be seamlessly integrated into both urban and rural grids. Future developments will likely focus on optimizing the dispatchability of DG resources by integrating them with ESS technologies, enabling real-time grid balancing. Moreover, modular MGs will emerge as a key solution, providing localized energy generation and storage capabilities that can operate independently or in conjunction with the larger grid. These MGs will be essential in areas prone to natural disasters, offering reliable power in times of crisis.

- EV Infrastructure and V2G Expansion: As the adoption of EVs accelerates, future energy systems will need to accommodate the growing demand for EV charging infrastructure. The widespread deployment of smart charging stations will allow for the optimized charging of EVs based on grid conditions, minimizing strain during peak demand periods. Additionally, V2G technology will become more prevalent, enabling EVs to discharge electricity back into the grid when needed. This will turn EVs into mobile energy storage units, capable of supporting grid stability during periods of high demand or low renewable energy generation. Governments and utilities will need to develop policies and standards that encourage the deployment of V2G systems while ensuring grid reliability [43].

- Hybrid Renewable-Energy-and-EV Systems: As distributed renewable energy systems and electric mobility become more interconnected, hybrid energy systems will emerge as a key component of future energy infrastructure. These systems combine renewable energy generation, energy storage, and EVs to create fully integrated solutions to balance supply and demand in real-time. For example, PV panels can power EV charging stations, while surplus energy can be stored in batteries for later use. This integrated approach will maximize the use of renewable energy, reduce reliance on fossil fuels, and enhance the overall resilience of energy systems.

11.3. A Roadmap for Building Resilient and Secure Energy Infrastructures

- Investment in SG Technologies and Infrastructure: A resilient energy infrastructure starts with modernizing the grid by deploying SG technologies. Governments and utilities must invest in upgrading transmission and distribution networks to handle the increased complexity of integrating DG, renewable energy, and electric mobility. This includes deploying real-time monitoring systems, automated control mechanisms, and advanced communication networks to optimize energy flows and prevent bottlenecks. Ensuring these scalable and flexible systems will be critical as energy demands grow and diversify.

- Regulatory Frameworks and Policy Support: Effective regulatory frameworks will be crucial for supporting the growth of DG, EVs, and SG technologies. Governments must establish clear interconnection standards that facilitate the integration of DERs into the grid. Additionally, policies that promote renewable energy adoption, such as feed-in tariffs and renewable portfolio standards, will provide financial incentives for investment in clean energy. Cybersecurity regulations must also evolve to address the growing threat of cyberattacks on energy infrastructure, ensuring that grid operators comply with the latest security standards and best practices.

- Resilience through Decentralization and Redundancy: One of the key strategies for enhancing grid resilience is decentralization. DG systems, MGs, and ESS solutions provide a more resilient energy system by reducing dependence on large, centralized power plants. In a natural disaster or cyberattack, decentralized systems can operate independently, ensuring that critical facilities such as hospitals, emergency services, and data centres remain powered. Redundancy, including the deployment of backup power systems and diversified energy sources, will further enhance resilience by ensuring that the failure of one component does not lead to a widespread outage.

- Collaborative Cybersecurity Initiatives: Given the increasing complexity of energy systems, collaboration between industry stakeholders, government agencies, and international organizations will be essential for addressing cybersecurity challenges. Initiatives such as the Electricity Information Sharing and Analysis Center in the United States and the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity in Europe provide platforms for sharing information about emerging threats, vulnerabilities, and best practices. Strengthening these collaborations will improve the ability to detect and mitigate cyberattacks on energy infrastructure, reducing the risk of widespread disruptions.

- Public-Private Partnerships and Innovation Hubs: Public-private partnerships will play a vital role in fostering innovation and driving the deployment of new energy technologies. Governments should establish innovation hubs that bring together academic institutions, technology companies, and energy providers to develop next-generation solutions for grid optimization, cybersecurity, and renewable energy integration. These hubs will accelerate the commercialization of emerging technologies such as solid-state batteries, FCs, and AI-driven grid management systems, ensuring that the energy sector remains at the forefront of technological innovation.

12. Conclusion

12.1. Summary of the Synergies Between Smart Grids, DG, EVs, and Cybersecurity

12.2. The Role of Advanced Technologies in Future-Proofing Energy Systems

12.3. Final Thoughts on a Secure, Sustainable, and Optimized Energy Future

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Allahham, A.; Greenwood, D.; Patsios, C. INCORPORATING AGEING PARAMETERS INTO OPTIMAL ENERGY MANAGEMENT OF DISTRIBUTION CONNECTED ENERGY STORAGE. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Electricity Distribution; Madrid; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S.H.R.; Allahham, A.; Adams, C. Techno-economic-environmental Analysis of a Smart Multi-energy Grid Utilising Geothermal Energy Storage for Meeting Heat Demand. IET Smart Grid 2021, 4, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahidinasab, V.; Nikkhah, S.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D. Boosting Integration Capacity of Electric Vehicles: A Robust Security Constrained Decision Making. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2021, 133, 107229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazhoohesh, M.; Allahham, A.; Das, R.; Walker, S. Investigating the Impact of Missing Data Imputation Techniques on Battery Energy Management System. IET Smart Grid 2021, 4, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahham, A.; Greenwood, D.; Patsios, C.; Taylor, P. Adaptive Receding Horizon Control for Battery Energy Storage Management with Age-and-Operation-Dependent Efficiency and Degradation. Electric Power Systems Research 2022, 209, 107936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, S.; Alahyari, A.; Allahham, A.; Alawasa, K. Optimal Integration of Hybrid Energy Systems: A Security-Constrained Network Topology Reconfiguration. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonti, D.; Maniatis, K. Security of Supply, Strategic Storage and Covid19: Which Lessons Learnt for Renewable and Recycled Carbon Fuels, and Their Future Role in Decarbonizing Transport? Appl Energy 2020, 271, 115216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajini, K. Integrating Renewable Energy into Existing Power Systems: Challenges and Opportunities. ournal of Advanced Research in Management Architecture Technology & Engineering (IJARMATE) 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Allahham, A.; Greenwood, D.; Patsios, C.; Taylor, P. Adaptive Receding Horizon Control for Battery Energy Storage Management with Age-and-Operation-Dependent Efficiency and Degradation. Electric Power Systems Research 2022, 209, 107936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Pages, C.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D.; Patsios, C. Modelling and Simulation of a Smartgrid Architecture for a Real Distribution Network in the UK. The Journal of Engineering 2019, 2019, 5415–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M. Smart Grids and Renewable Energy Systems: Perspectives and Grid Integration Challenges. Energy Strategy Reviews 2024, 51, 101299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seward, W.; Chi, L.; Qadrdan, M.; Allahham, A.; Alawasa, K. Sizing, Economic, and Reliability Analysis of Photovoltaics and Energy Storage for an Off-grid Power System in Jordan. IET Energy Systems Integration 2023, 5, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, S.; Alahyari, A.; Rabiee, A.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D. Multi-Port Coordination: Unlocking Flexibility and Hydrogen Opportunities in Green Energy Networks. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2024, 158, 109937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, C.J.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D.; Blake, S.; Taylor, P. Modelling of a Virtual Power Plant Using Hybrid Automata. The Journal of Engineering 2019, 2019, 3918–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, S.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D.; Bialek, J.W.; Walker, S. Application of Robust Receding Horizon Controller for Real-Time Energy Management of Reconfigurable Islanded Microgrids. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Madrid PowerTech; IEEE, June 28 2021; pp. 1–6.

- Salkuti, S.R. Challenges, Issues and Opportunities for the Development of Smart Grid. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE) 2020, 10, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, S.; Allahham, A.; Royapoor, M.; Bialek, J.W.; Giaouris, D. Optimising Building-to-Building and Building-for-Grid Services Under Uncertainty: A Robust Rolling Horizon Approach. IEEE Trans Smart Grid 2022, 13, 1453–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahham, A.; Greenwood, D.; Patsios, C.; Walker, S.L.; Taylor, P. Primary Frequency Response from Hydrogen-Based Bidirectional Vector Coupling Storage: Modelling and Demonstration Using Power-Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation. Front Energy Res 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dileep, G. A Survey on Smart Grid Technologies and Applications. Renew Energy 2020, 146, 2589–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, K.; Pedinti, V.S.; Goel, S. Decentralized Distributed Generation in India: A Review. Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, G.; Mancarella, P. Distributed Multi-Generation: A Comprehensive View. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2009, 13, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.-E.; Rahimi, E.; Javadi, M.S.; Nezhad, A.E.; Lotfi, M.; Shafie-khah, M.; Catalão, J.P.S. Impact of Distributed Generation on Protection and Voltage Regulation of Distribution Systems: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 105, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayeghi, H.; Alilou, M. Distributed Generation and Microgrids. In Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems and Microgrids; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 73–102.

- Khawaja, Y.; Qiqieh, I.; Alzubi, J.; Alzubi, O.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D. Design of Cost-Based Sizing and Energy Management Framework for Standalone Microgrid Using Reinforcement Learning. Solar Energy 2023, 251, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, Y.; Qiqieh, I.; Alzubi, J.; Alzubi, O.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D. Design of Cost-Based Sizing and Energy Management Framework for Standalone Microgrid Using Reinforcement Learning. Solar Energy 2023, 251, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, K.Y.; Chin, H.H.; Klemeš, J.J. Blockchain Technology for Distributed Generation: A Review of Current Development, Challenges and Future Prospect. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 175, 113170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarizadeh, H.; Yamini, E.; Zolfaghari, S.M.; Esmaeilion, F.; Assad, M.E.H.; Soltani, M. Navigating Challenges in Large-Scale Renewable Energy Storage: Barriers, Solutions, and Innovations. Energy Reports 2024, 12, 2179–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, K.; Ali, M.; Siddique, M.N.I.; Chand, A.A.; Kumar, N.M.; Dong, D.; Pota, H.R. A Review of Battery Energy Storage Systems for Ancillary Services in Distribution Grids: Current Status, Challenges and Future Directions. Front Energy Res 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskouei, M.Z.; Şeker, A.A.; Tunçel, S.; Demirbaş, E.; Gözel, T.; Hocaoğlu, M.H.; Abapour, M.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B. A Critical Review on the Impacts of Energy Storage Systems and Demand-Side Management Strategies in the Economic Operation of Renewable-Based Distribution Network. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, P.; Vendel, M.; Nuur, C. Integrating Distributed Energy Resources in Electricity Distribution Systems: An Explorative Study of Challenges Facing DSOs in Sweden. Util Policy 2020, 67, 101117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, Y.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D.; Patsios, C.; Walker, S.; Qiqieh, I. An Integrated Framework for Sizing and Energy Management of Hybrid Energy Systems Using Finite Automata. Appl Energy 2019, 250, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.H.C.; Lim, Y.S.; Wong, J.; Allahham, A.; Patsios, C. A Novel Characteristic-Based Degradation Model of Li-Ion Batteries for Maximum Financial Benefits of Energy Storage System during Peak Demand Reductions. Appl Energy 2023, 343, 121206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, S.; Rabiee, A.; Soroudi, A.; Allahham, A.; Taylor, P.C.; Giaouris, D. Distributed Flexibility to Maintain Security Margin through Decentralised TSO–DSO Coordination. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2023, 146, 108735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadid, R.; Khawaja, Y.; Bani-Abdullah, A.; Akho-Zahieh, M.; Allahham, A. Investigation of Weather Conditions on the Output Power of Various Photovoltaic Systems. Renew Energy 2023, 217, 119202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royapoor, M.; Allahham, A.; Hosseini, S.H.R.; Rufa’I, N.A.; Walker, S.L. Towards 2050 Net Zero Carbon Infrastructure: A Critical Review of Key Decarbonization Challenges in the Domestic Heating Sector in the UK. Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, S.; Allahham, A.; Bialek, J.W.; Walker, S.L.; Giaouris, D.; Papadopoulou, S. Active Participation of Buildings in the Energy Networks: Dynamic/Operational Models and Control Challenges. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.; Vahidinasab, V.; Sepasian, M.S.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D.; Taylor, P.; Aghaei, J. Stochastic Procurement of Fast Reserve Services in Renewable Integrated Power Systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 30946–30959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhsen, H.; Allahham, A.; Al-Halhouli, A.; Al-Mahmodi, M.; Alkhraibat, A.; Hamdan, M. Business Model of Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading: A Review of Literature. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, S.; Sarantakos, I.; Zografou-Barredo, N.-M.; Rabiee, A.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D. A Joint Risk- and Security-Constrained Control Framework for Real-Time Energy Scheduling of Islanded Microgrids. IEEE Trans Smart Grid 2022, 13, 3354–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Mohanty, S.; Rout, P.K.; Sahu, B.K.; Parida, S.M.; Kotb, H.; Flah, A.; Tostado-Véliz, M.; Abdul Samad, B.; Shouran, M. An Insight into the Integration of Distributed Energy Resources and Energy Storage Systems with Smart Distribution Networks Using Demand-Side Management. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 8914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.O.; Elmarghany, M.R.; Abdelsalam, M.M.; Sabry, M.N.; Hamed, A.M. Closed-Loop Home Energy Management System with Renewable Energy Sources in a Smart Grid: A Comprehensive Review. J Energy Storage 2022, 50, 104609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehmani, M.H.; Reisslein, M.; Rachedi, A.; Erol-Kantarci, M.; Radenkovic, M. Integrating Renewable Energy Resources Into the Smart Grid: Recent Developments in Information and Communication Technologies. IEEE Trans Industr Inform 2018, 14, 2814–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Mifta, Z.; Salsabil, N.A.; Papiya, S.J.; Hossain, M.; Roy, P.; Chowdhury, N.-U.-R.; Farrok, O. A Critical Review on Control Mechanisms, Supporting Measures, and Monitoring Systems of Microgrids Considering Large Scale Integration of Renewable Energy Sources. Energy Reports 2023, 10, 4582–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couraud, B.; Andoni, M.; Robu, V.; Norbu, S.; Chen, S.; Flynn, D. Responsive FLEXibility: A Smart Local Energy System. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 182, 113343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.-H.; Pye, S. Assessing the Benefits of Demand-Side Flexibility in Residential and Transport Sectors from an Integrated Energy Systems Perspective. Appl Energy 2018, 228, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, S.; Becerra, V.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D.; Foster, J.M.; Roberts, K.; Hutchinson, D.; Fawcett, J. Demand Response Model Development for Smart Households Using Time of Use Tariffs and Optimal Control—The Isle of Wight Energy Autonomous Community Case Study. Energies (Basel) 2020, 13, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, S.; Allahham, A.; Alahyari, A.; Patsios, C.; Taylor, P.C.; Walker, S.L.; Giaouris, D. Building-to-Building Energy Trading under the Influence of Occupant Comfort. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2024, 159, 110041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabalci, E.; Kabalci, Y. Introduction to Smart Grid Architecture. In; 2019; pp. 3–45.

- Avancini, D.B.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C.; Martins, S.G.B.; Rabêlo, R.A.L.; Al-Muhtadi, J.; Solic, P. Energy Meters Evolution in Smart Grids: A Review. J Clean Prod 2019, 217, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekik, S.; Baccour, N.; Jmaiel, M.; Drira, K. Wireless Sensor Network Based Smart Grid Communications: Challenges, Protocol Optimizations, and Validation Platforms. Wirel Pers Commun 2017, 95, 4025–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantakos, I.; Nikkhah, S.; Peker, M.; Bowkett, A.; Sayfutdinov, T.; Alahyari, A.; Patsios, C.; Mangan, J.; Allahham, A.; Bougioukou, E.; et al. A Robust Logistics-Electric Framework for Optimal Power Management of Electrified Ports under Uncertain Vessel Arrival Time. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain 2024, 10, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantakos, I.; Bowkett, A.; Allahham, A.; Sayfutdinov, T.; Murphy, A.; Pazouki, K.; Mangan, J.; Liu, G.; Chang, E.; Bougioukou, E.; et al. Digitalization for Port Decarbonization: Decarbonization of Key Energy Processes at the Port of Tyne. IEEE Electrification Magazine 2023, 11, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, S.; Rezgui, Y.; Hippolyte, J.-L.; Jayan, B.; Li, H. Towards the next Generation of Smart Grids: Semantic and Holonic Multi-Agent Management of Distributed Energy Resources. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 77, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, V.; Manna, S.; Rajput, S.K.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, B.; Alsharif, M.H.; Kim, M.-K. Navigating the Complexities of Distributed Generation: Integration, Challenges, and Solutions. Energy Reports 2024, 12, 3302–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtola, T.; Zahedi, A. Solar Energy and Wind Power Supply Supported by Storage Technology: A Review. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2019, 35, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Meena, N.K.; Singh, A.R.; Deng, Y.; He, X.; Bansal, R.C.; Kumar, P. Strategic Integration of Battery Energy Storage Systems with the Provision of Distributed Ancillary Services in Active Distribution Systems. Appl Energy 2019, 253, 113503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, N.; Aboudrar, I.; El Hani, S.; Ait-Ahmed, N.; Motahhir, S.; Machmoum, M. Energy Transition and Resilient Control for Enhancing Power Availability in Microgrids Based on North African Countries: A Review. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallsgrove, R.; Woo, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Akiba, L. The Emerging Potential of Microgrids in the Transition to 100% Renewable Energy Systems. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.; Patra, S.; Sidqi, Y.; Bowler, B.; Zimmermann, F.; Deconinck, G.; Papaemmanouil, A.; Khadem, S. Community-Based Microgrids: Literature Review and Pathways to Decarbonise the Local Electricity Network. Energies (Basel) 2022, 15, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, I.; Rajasekharan, J.; Cali, Ü. Decentralization, Decarbonization and Digitalization in Swarm Electrification. Energy for Sustainable Development 2024, 81, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku, M.Y. Recent Advances in Energy Storage Systems for Renewable Source Grid Integration: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A.A.; Kalogiannis, T.; Van Mierlo, J.; Berecibar, M. A Comprehensive Review of Stationary Energy Storage Devices for Large Scale Renewable Energy Sources Grid Integration. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 159, 112213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokmen, K.F.; Cavus, M. Review of Batteries Thermal Problems and Thermal Management Systems. Journal of Innovative Science and Engineering (JISE) 2017, 1, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad Hamdan; Cosmas Dominic Daudu; Adefunke Fabuyide; Emmanuel Augustine Etukudoh; Sedat Sonko Next-Generation Batteries and U.S. Energy Storage: A Comprehensive Review: Scrutinizing Advancements in Battery Technology, Their Role in Renewable Energy, and Grid Stability. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 2024, 21, 1984–1998. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, K.; Dubarry, M.; Glick, M.B. The Viability of Vehicle-to-Grid Operations from a Battery Technology and Policy Perspective. Energy Policy 2018, 113, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elberry, A.M.; Thakur, J.; Veysey, J. Seasonal Hydrogen Storage for Sustainable Renewable Energy Integration in the Electricity Sector: A Case Study of Finland. J Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, H.; Faaij, A. A Review at the Role of Storage in Energy Systems with a Focus on Power to Gas and Long-Term Storage. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 81, 1049–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widera, B. Renewable Hydrogen Implementations for Combined Energy Storage, Transportation and Stationary Applications. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2020, 16, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, V.M.; Ortiz, A.; Ortiz, I. Challenges and Prospects of Renewable Hydrogen-Based Strategies for Full Decarbonization of Stationary Power Applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 152, 111628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elalfy, D.A.; Gouda, E.; Kotb, M.F.; Bureš, V.; Sedhom, B.E. Comprehensive Review of Energy Storage Systems Technologies, Objectives, Challenges, and Future Trends. Energy Strategy Reviews 2024, 54, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldinelli, A.; Barelli, L.; Bidini, G. Progress in Renewable Power Exploitation: Reversible Solid Oxide Cells-Flywheel Hybrid Storage Systems to Enhance Flexibility in Micro-Grids Management. J Energy Storage 2019, 23, 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farivar, G.G.; Manalastas, W.; Tafti, H.D.; Ceballos, S.; Sanchez-Ruiz, A.; Lovell, E.C.; Konstantinou, G.; Townsend, C.D.; Srinivasan, M.; Pou, J. Grid-Connected Energy Storage Systems: State-of-the-Art and Emerging Technologies. Proceedings of the IEEE 2023, 111, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, J.; Mohagheghi, S.; Kroposki, B. Application of Mobile Energy Storage for Enhancing Power Grid Resilience: A Review. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14, 6476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.; Kamran, M.; Rashid, U. Impact Analysis of Vehicle-to-Grid Technology and Charging Strategies of Electric Vehicles on Distribution Networks – A Review. J Power Sources 2015, 277, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavus, M. Maximizing Microgrid Efficiency: A Unified Approach with Extended Optimal Propositional Logic Control. Academia Green Energy 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.N. Vehicle-to-Grid Demonstration Project: Grid Regulation Ancillary Service with a Battery Electric Vehicle; 2002.

- Yang, Y.; Wang, W.; Qin, J.; Wang, M.; Ma, Q.; Zhong, Y. Review of Vehicle to Grid Integration to Support Power Grid Security. Energy Reports 2024, 12, 2786–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.; Panda, S.; Parida, S.M.; Rout, P.K.; Sahu, B.K.; Bajaj, M.; Zawbaa, H.M.; Kumar, N.M.; Kamel, S. Demand Side Management of Electric Vehicles in Smart Grids: A Survey on Strategies, Challenges, Modeling, and Optimization. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 12466–12490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, S.A.; Paredes, Á.; González, J.M.; Aguado, J.A. A Three-Layer Game Theoretic-Based Strategy for Optimal Scheduling of Microgrids by Leveraging a Dynamic Demand Response Program Designer to Unlock the Potential of Smart Buildings and Electric Vehicle Fleets. Appl Energy 2023, 347, 121440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.B.; Awais, M.; Alquthami, T.; Khan, I. An Optimal Scheduling and Distributed Pricing Mechanism for Multi-Region Electric Vehicle Charging in Smart Grid. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 40298–40312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavus, M.; Allahham, A.; Adhikari, K.; Giaouris, D. A Hybrid Method Based on Logic Predictive Controller for Flexible Hybrid Microgrid with Plug-and-Play Capabilities. Appl Energy 2024, 359, 122752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.M.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.K.; Yong, J.Y. Integration of Electric Vehicles in Smart Grid: A Review on Vehicle to Grid Technologies and Optimization Techniques. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 53, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A.; Tan, C.W.; Ayop, R.; Dobi, A.; Lau, K.Y. A Comprehensive Review of Energy Management Strategy in Vehicle-to-Grid Technology Integrated with Renewable Energy Sources. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2021, 47, 101439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, H.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Li, S.; Tan, C.W. Electric Vehicles Standards, Charging Infrastructure, and Impact on Grid Integration: A Technological Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 120, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butun, I.; Lekidis, A.; Santos, D. Security and Privacy in Smart Grids: Challenges, Current Solutions and Future Opportunities. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy; SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology Publications, 2020; pp. 733–741.

- Unsal, D.B.; Ustun, T.S.; Hussain, S.M.S.; Onen, A. Enhancing Cybersecurity in Smart Grids: False Data Injection and Its Mitigation. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Qammar, A.; Zhang, Z.; Karim, A.; Ning, H. Cyber Threats to Smart Grids: Review, Taxonomy, Potential Solutions, and Future Directions. Energies (Basel) 2022, 15, 6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faquir, D.; Chouliaras, N.; Sofia, V.; Olga, K.; Maglaras, L. Cybersecurity in Smart Grids, Challenges and Solutions. AIMS Electronics and Electrical Engineering 2021, 5, 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah-Ofori, A.; Islam, S.; Lee, S.W.; Shamszaman, Z.U.; Muhammad, K.; Altaf, M.; Al-Rakhami, M.S. Cyber Threat Predictive Analytics for Improving Cyber Supply Chain Security. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 94318–94337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, V.D.; Raluca, N.A. Cybersecurity Threats and Vulnerabilities of Critical Infrastructures. American Research Journal of Humanities Social Science (ARJHSS) 2021, 4, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, B.; Sarker, A.; Abhi, S.H.; Das, S.K.; Ali, Md.F.; Islam, M.M.; Islam, Md.R.; Moyeen, S.I.; Rahman Badal, Md.F.; Ahamed, Md.H.; et al. Potential Smart Grid Vulnerabilities to Cyber Attacks: Current Threats and Existing Mitigation Strategies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheem, M.; Shah, S.B.H.; Butt, R.A.; Raza, B.; Anwar, M.; Ashraf, M.W.; Ngadi, Md.A.; Gungor, V.C. Smart Grid Communication and Information Technologies in the Perspective of Industry 4.0: Opportunities and Challenges. Comput Sci Rev 2018, 30, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji Mirzaee, P.; Shojafar, M.; Cruickshank, H.; Tafazolli, R. Smart Grid Security and Privacy: From Conventional to Machine Learning Issues (Threats and Countermeasures). IEEE Access 2022, 10, 52922–52954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, S.; Amissah, J.; Kinga, S.; Mugerwa, G.; Emmanuel, E.; Mansour, D.-E.A.; Bajaj, M.; Blazek, V.; Prokop, L. Securing Modern Power Systems: Implementing Comprehensive Strategies to Enhance Resilience and Reliability against Cyber-Attacks. Results in Engineering 2024, 23, 102647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Oubelaid, A.; Almazrouei, S. khameis Staying Ahead of Threats: A Review of AI and Cyber Security in Power Generation and Distribution. International Journal of Electrical and Electronics Research 2023, 11, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengidis, N.; Tsikrika, T.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. Blockchain and AI for the Next Generation Energy Grids: Cybersecurity Challenges and Opportunities. Information & Security: An International Journal 2019, 43, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, Z. Robust and Efficient Authentication Protocol Based on Elliptic Curve Cryptography for Smart Grids. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Green Computing and Communications and IEEE Internet of Things and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing; IEEE, August 2013; pp. 2089–2093.

- Priyanka, C.N.; Ramachandran, N. Analysis on Secured Cryptography Models with Robust Authentication and Routing Models in Smart Grid. International Journal of Safety and Security Engineering 2023, 13, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, I.; Lim, J.; Chae, K. Secure Authentication for Structured Smart Grid System. In Proceedings of the 2015 9th International Conference on Innovative Mobile and Internet Services in Ubiquitous Computing, IEEE, July 2015; pp. 200–204. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Qian, Y.; Sharif, H. A Secure and Reliable In-Network Collaborative Communication Scheme for Advanced Metering Infrastructure in Smart Grid. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference, IEEE, March 2011; pp. 909–914. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Su, C. Secure and Efficient Mutual Authentication Protocol for Smart Grid under Blockchain. Peer Peer Netw Appl 2021, 14, 2681–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavus, M.; Allahham, A.; Zangiabadi, M.; Adhikari, K.; Giaouris, D. Energy Management of Microgrids Using a Flexible Hybrid Predictive Controller. In Proceedings of the In Proceedings of the 2nd World Energy Conference and 7th UK Energy Storage Conference; Birmingham, 2022.

- Pamulapati, T.; Cavus, M.; Odigwe, I.; Allahham, A.; Walker, S.; Giaouris, D. A Review of Microgrid Energy Management Strategies from the Energy Trilemma Perspective. Energies (Basel) 2022, 16, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, O.; Cavus, M.; Cengiz, M.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D.; Forshaw, M. Hybrid Intelligent Control System for Adaptive Microgrid Optimization: Integration of Rule-Based Control and Deep Learning Techniques. Energies (Basel) 2024, 17, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavus, M.; Ugurluoglu, Y.F.; Ayan, H.; Allahham, A.; Adhikari, K.; Giaouris, D. Switched Auto-Regressive Neural Control (S-ANC) for Energy Management of Hybrid Microgrids. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 11744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W.; Vlasov, A.; Selivanov, K.; Muraviev, K.; Shakhnov, V. Prospects and Challenges of the Machine Learning and Data-Driven Methods for the Predictive Analysis of Power Systems: A Review. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavus, M.; Allahham, A. Enhanced Microgrid Control through Genetic Predictive Control: Integrating Genetic Algorithms with Model Predictive Control for Improved Non-Linearity and Non-Convexity Handling. Energies (Basel) 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Kamble, R. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Techniques in Power Systems Automation. In Artificial Intelligence Techniques in Power Systems Operations and Analysis; Taylor & Francis, 2023.

- Cavus, M.; Allahham, A.; Adhikari, K.; Zangiabadia, M.; Giaouris, D. Control of Microgrids Using an Enhanced Model Predictive Controller. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Power Electronics, Machines and Drives (PEMD 2022); Institution of Engineering and Technology, 2022; pp. 660–665.

- Cavus, M.; Allahham, A.; Adhikari, K.; Zangiabadi, M.; Giaouris, D. Energy Management of Grid-Connected Microgrids Using an Optimal Systems Approach. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 9907–9919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmat, A.; de Vos, M.; Ghiassi-Farrokhfal, Y.; Palensky, P.; Epema, D. A Novel Decentralized Platform for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading Market with Blockchain Technology. Appl Energy 2021, 282, 116123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachuk, R.-V.; Ilie, D.; Robert, R.; Kebande, V.; Tutschku, K. Towards Efficient Privacy and Trust in Decentralized Blockchain-Based Peer-to-Peer Renewable Energy Marketplace. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2023, 35, 101146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Li, J.; Amin, W.; Huang, Q.; Umer, K.; Ahmad, S.A.; Ahmad, F.; Raza, A. Role of Blockchain Technology in Transactive Energy Market: A Review. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2022, 53, 102646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onile, A.E.; Petlenkov, E.; Levron, Y.; Belikov, J. Smartgrid-Based Hybrid Digital Twins Framework for Demand Side Recommendation Service Provision in Distributed Power Systems. Future Generation Computer Systems 2024, 156, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]