Submitted:

14 October 2024

Posted:

15 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

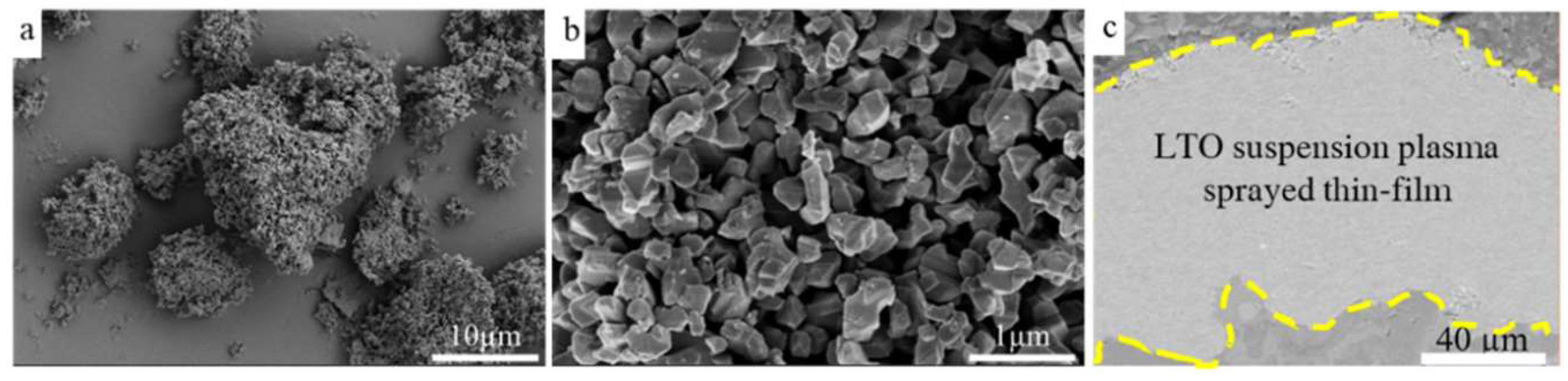

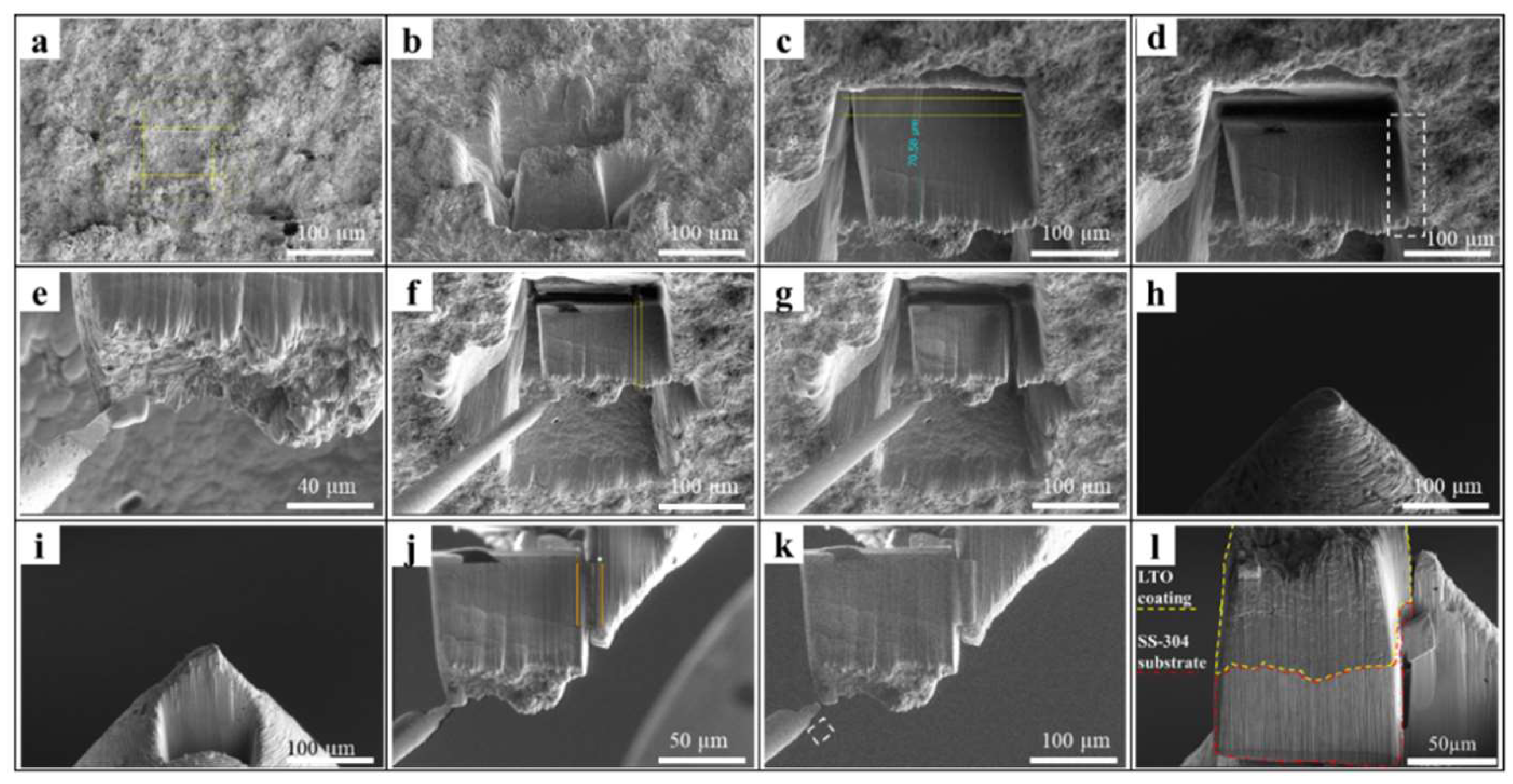

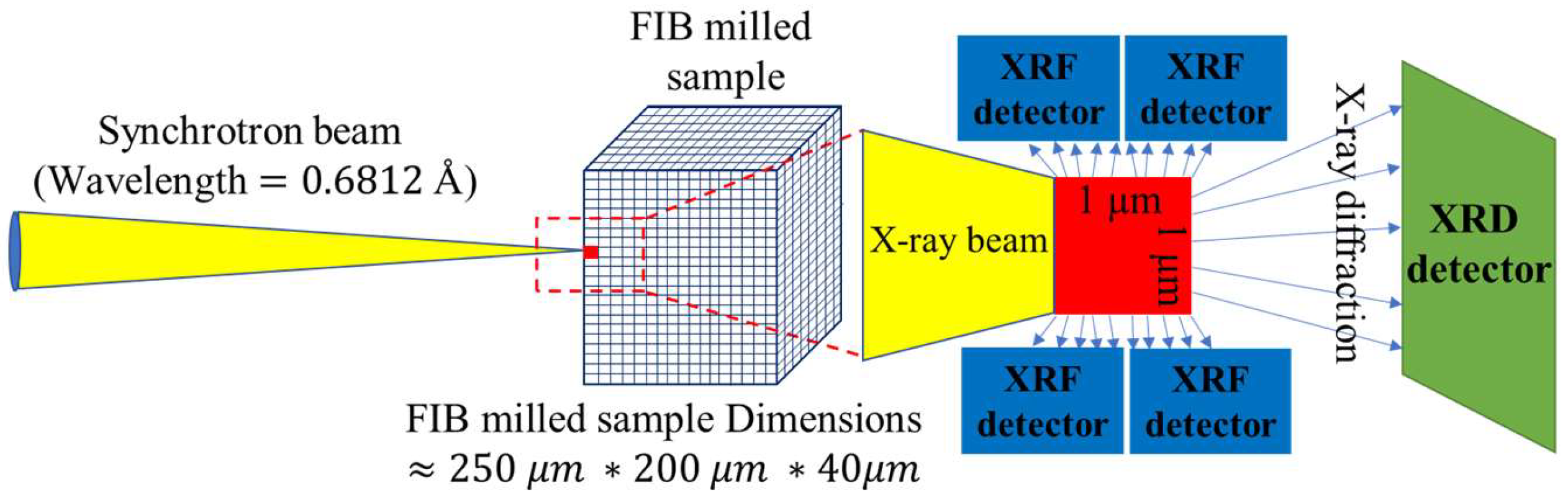

Experimental Works

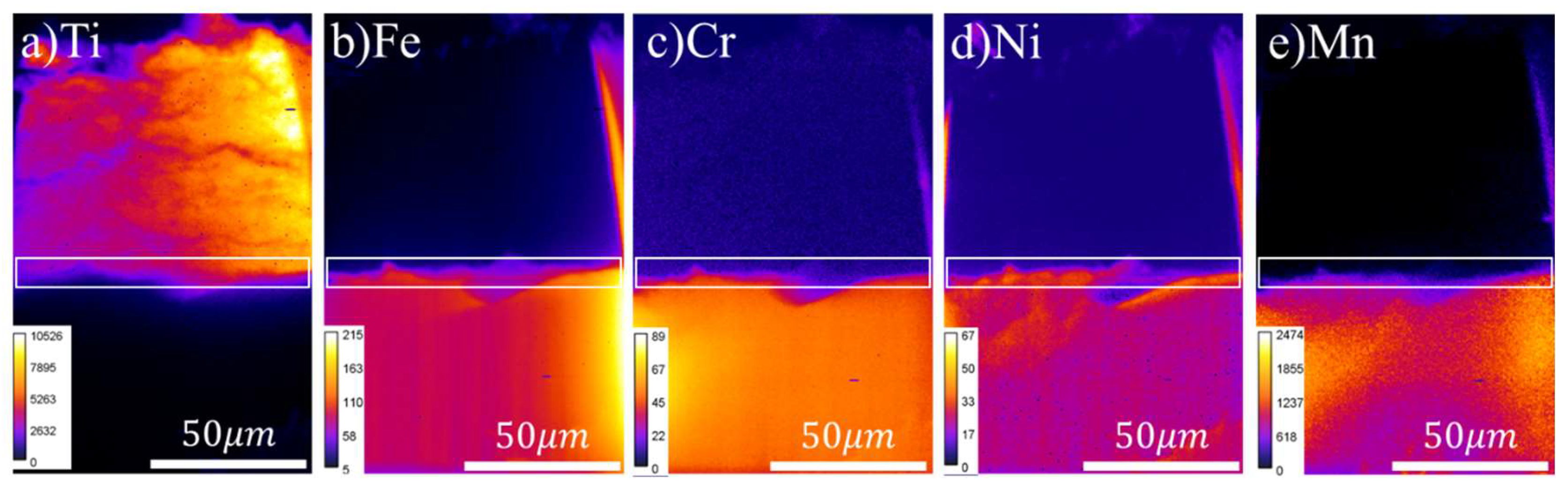

Results and Discussion

Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgment

References

- P. Kurzweil, “Gaston Planté and his invention of the lead–acid battery—The genesis of the first practical rechargeable battery,” J Power Sources, vol. 195, no. 14, pp. 4424–4434, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- D. A. J. Rand and P. T. Moseley, “Energy Storage with Lead–Acid Batteries,” in Electrochemical Energy Storage for Renewable Sources and Grid Balancing, Elsevier, 2015, pp. 201–222. [CrossRef]

- J. Garche, C. Dyer, P. T. Moseley, Z. Ogumi, D. A. J. Rand, and B. Scrosati, Encyclopedia of electrochemical power sources. Newnes, 2013.

- A. B. Yaroslavtsev, I. A. Stenina, T. L. Kulova, A. M. Skundin, and A. V. Desyatov, “Nanomaterials for Electrical Energy Storage,” in Comprehensive Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, Elsevier, 2019, pp. 165–206. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Mohammadi and D. J. Fray, “Low temperature nanostructured lithium titanates: controlling the phase composition, crystal structure and surface area,” J Solgel Sci Technol, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 19–35, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Vijayakumar, Sebastien Kerisit, Kevin M. Rosso, Sarah D. Burton, Jesse A. Sears, Zhenguo Yang, Gordon L. Graff, Jun Liu, Jianzhi Hu, “Lithium diffusion in Li4Ti5O12 at high temperatures,” J Power Sources, vol. 196, no. 4, pp. 2211–2220, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Sorensen, S. J. Barry, H.-K. Jung, J. M. Rondinelli, J. T. Vaughey, and K. R. Poeppelmeier, “Three-Dimensionally Ordered Macroporous Li 4 Ti 5 O 12 : Effect of Wall Structure on Electrochemical Properties,” Chemistry of Materials, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 482–489, Jan. 2006. [CrossRef]

- X. Sun, P. V. Radovanovic, and B. Cui, “Advances in spinel Li 4 Ti 5 O 12 anode materials for lithium-ion batteries,” New Journal of Chemistry, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 38–63, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhou, N. Huang, J. Yan, H. Zhang, and X. Li, “High Rate Performance Li 4 Ti 5 O 12 /N-doped Carbon/Stainless Steel Mesh Flexible Electrodes Prepared by Electrostatic Spray Deposition for Lithium-ion Capacitors,” Chem Lett, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 337–340, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Arman Hasani, Mathis Luya, Nikhil Kamboj, Chinmayee Nayak, Shrikant Joshi, Antti Salminen, Sneha Goel, Ashish Ganvir, “Laser Processing of Liquid Feedstock Plasma-Sprayed Lithium Titanium Oxide Solid-State-Battery Electrode,” Coatings, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 224, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Liang, Y. Wang, X. Zhang, D. Han, L. Lan, and Y. Zhang, “Performance study of a Li4Ti5O12 electrode for lithium batteries prepared by atmospheric plasma spraying,” Ceram Int, vol. 45, no. 17, pp. 23750–23755, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Wu, X. Liang, X. Zhang, L. Lan, S. Li, and Q. Gai, “Structural evolution of plasma sprayed amorphous Li4Ti5O12 electrode and ceramic/polymer composite electrolyte during electrochemical cycle of quasi-solid-state lithium battery,” Journal of Advanced Ceramics, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 347–354, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Oksa, E. Turunen, T. Suhonen, T. Varis, and S.-P. Hannula, “Optimization and Characterization of High Velocity Oxy-fuel Sprayed Coatings: Techniques, Materials, and Applications,” Coatings, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 17–52, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Bianchi, A. C. Leger, M. Vardelle, A. Vardelle, and P. Fauchais, “Splat formation and cooling of plasma-sprayed zirconia,” Thin Solid Films, vol. 305, no. 1–2, pp. 35–47, Aug. 1997. [CrossRef]

- P. Kotalík and K. Voleník, “Cooling rates of plasma-sprayed metallic particles in liquid and gaseous nitrogen,” J Phys D Appl Phys, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 567–573, Feb. 2001. [CrossRef]

- A. Ganvir, R. F. Calinas, N. Markocsan, N. Curry, and S. Joshi, “Experimental visualization of microstructure evolution during suspension plasma spraying of thermal barrier coatings,” J Eur Ceram Soc, vol. 39, no. 2–3, pp. 470–481, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Aghasibeig, F. Tarasi, R. S. Lima, A. Dolatabadi, and C. Moreau, “A Review on Suspension Thermal Spray Patented Technology Evolution,” Journal of Thermal Spray Technology, vol. 28, no. 7, pp. 1579–1605, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Torre-Gamarra, M. Sotomayor, W. Bucheli, J. Amarilla, J. Sanchez, B. Levenfeld, A. Varez, “Tape casting manufacturing of thick Li4Ti5O12 ceramic electrodes with high areal capacity for lithium-ion batteries,” J Eur Ceram Soc, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 1025–1032, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

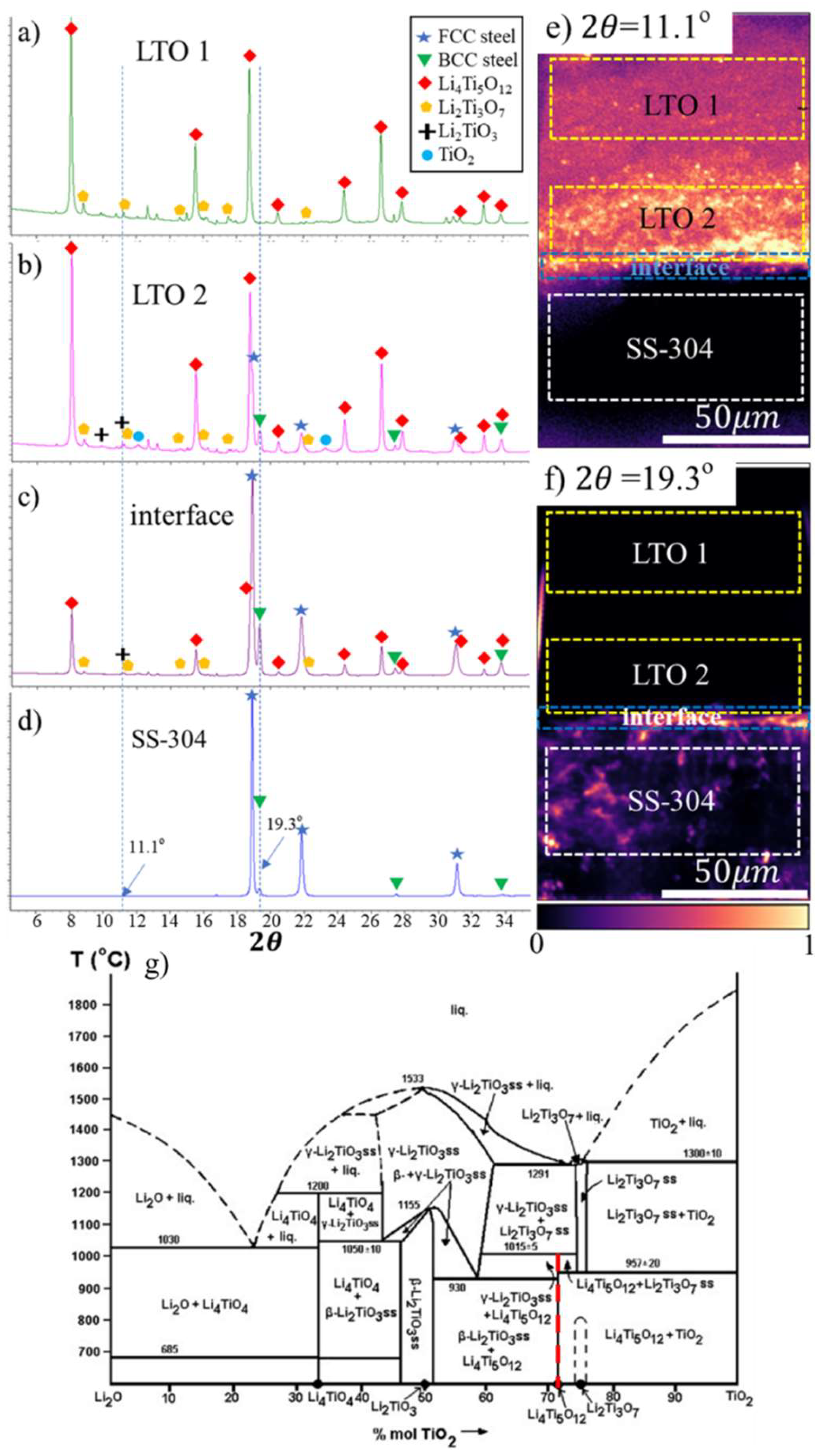

- G. Izquierdo and A. R. West, “Phase equilibria in the system Li2O-TiO2,” Mater Res Bull, vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 1655–1660, Nov. 1980. [CrossRef]

- P. Kaskes, T. Déhais, S. J. de Graaff, S. Goderis, and P. Claeys, “Micro–X-ray fluorescence (µXRF) analysis of proximal impactites: High-resolution element mapping, digital image analysis, and quantifications,” in Large Meteorite Impacts and Planetary Evolution VI, Geological Society of America, 2021, pp. 171–206. [CrossRef]

- H. A. O. Wang, D. Grolimund, L. R. Van Loon, K. Barmettler, C. N. Borca, B. Aeschlimann, D. Günther, “Quantitative Chemical Imaging of Element Diffusion into Heterogeneous Media Using Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry, Synchrotron Micro-X-ray Fluorescence, and Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure Spectroscopy,” Anal Chem, vol. 83, no. 16, pp. 6259–6266, Aug. 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Mathiyalagan, S. Björklund, S. Johansson Storm, G. Salian, R. Le Ruyet, R. Younesi, S. Joshi, “Facile one-step fabrication of Li4Ti5O12 coatings by suspension plasma spraying”, Materials Research Bulletin, vol. 181, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Killian Clovis, “Deposition and characteristics of ther-mal sprayed layers as solid-state thin film battery components,” University West, Trollhättan, SWEDEN, 2023.

- C. N. Borca, D. Grolimund, M. Willimann, B. Meyer, K. Jefimovs, J. Vila-Comamala, C. David, “The microXAS beamline at the swiss light source: Towards nano-scale imaging,” J Phys Conf Ser, vol. 186, p. 012003, Sep. 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. Grimm, “https://www.dectris.com/en/detectors/x-ray-detectors/eiger2/eiger2-for-synchrotrons/.”.

- A. W. Colldeweih, M. G. Makowska, O. Tabai, D. F. Sanchez, and J. Bertsch, “Zirconium hydride phase mapping in Zircaloy-2 cladding after delayed hydride cracking,” Materialia (Oxf), vol. 27, p. 101689, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Ashiotis, A. Deschildre, Z. Nawaz, J. P. Wright, D. Karkoulis, F. Emmanuel Piccac, J. Kieffer, “The fast azimuthal integration Python library: pyFAI,” J Appl Crystallogr, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 510–519, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Solé, E. Papillon, M. Cotte, Ph. Walter, and J. Susini, “A multiplatform code for the analysis of energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectra,” Spectrochim Acta Part B At Spectrosc, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 63–68, Jan. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, Y. Huang, X. Wang, Y. Zhang, J. Ding, Y. Guo, X. Tang, “Synthesis of defects and TiO2 co-enhanced Li4Ti5O12 by a simple solid-state method as advanced anode for lithium-ion batteries,” Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 6682–6687, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Subhan, F. Oemry, S. N. Khusna, and E. Hastuti, “Effects of activated carbon treatment on Li4Ti5O12 anode material synthesis for lithium-ion batteries,” Ionics (Kiel), vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 1025–1034, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Q. Meng, L. Wang, F. Chen, Q. Hao, and X. Sun, “Preparation of Ramsdellite-type Li2Ti3O7 hollow microspheres with high tap density by flame melting method as anode of Li-ion battery,” Mater Res Bull, vol. 161, p. 112166, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kang, Y. Xie, F. Su, K. Dai, M. Shui, and J. Shu, “α-Li 2 TiO 3 : a new ultrastable anode material for lithium-ion batteries,” Dalton Transactions, vol. 51, no. 47, pp. 18277–18283, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Yang, Z. Shan, X. Liu, L. Tan, and S. Wang, “Study on Thermal Simulation of LiNi 0.5 Mn 1.5 O 4 /Li 4 Ti 5 O 12 Battery,” Energy Technology, vol. 9, no. 5, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Chen, C. C. Wan, and Y. Y. Wang, “Thermal analysis of lithium-ion batteries,” J Power Sources, vol. 140, no. 1, pp. 111–124, Jan. 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. Pelleg, “Interdiffusion,” 2016, pp. 69–74. [CrossRef]

- G. N. Irving, J. Stringer, and D. P. Whittle, “Effect of the possible fcc stabilizers Mn, Fe, and Ni on the high-temperature oxidation of Co-Cr alloys,” Oxidation of Metals, vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 393–407, Dec. 1974. [CrossRef]

- I. Shuro, S. Kobayashi, T. Nakamura, and K. Tsuzaki, “Determination of α/γ phase boundaries in the Fe–Cr–Ni–Mn quaternary system with a diffusion-multiple method,” J Alloys Compd, vol. 588, pp. 284–289, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. D. Shannon, “Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides,” Acta Crystallographica Section A, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 751–767, Sep. 1976. [CrossRef]

- M. Mojahed, A. Gholizadeh, and H. R. Dizaji, “Influence of Ti4+ substitution on the structural, magnetic, and dielectric properties of Ni-Cu–Zn ferrite,” Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, vol. 35, no. 18, p. 1239, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

| Element | Ti | O | Cl, Si, Al | Fe | Cr | Ni | Mn | C, P, S, Si, N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTO powder (wt%) (Excluding Li, which could not be detected) |

54.4 | 45.2 | 0.4 | - | - | - | - | - |

| SS-304 substrate(wt%) | - | - | - | balance | 18-20 | 8-11 | 2 | 1.005 |

| Suspension feed (mL/min) | Total gas flow (L/min) | Power (kW) | Enthalpy (kJ) | Number of passes |

| 42 | 200 | 110 | 11 | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).