Submitted:

04 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

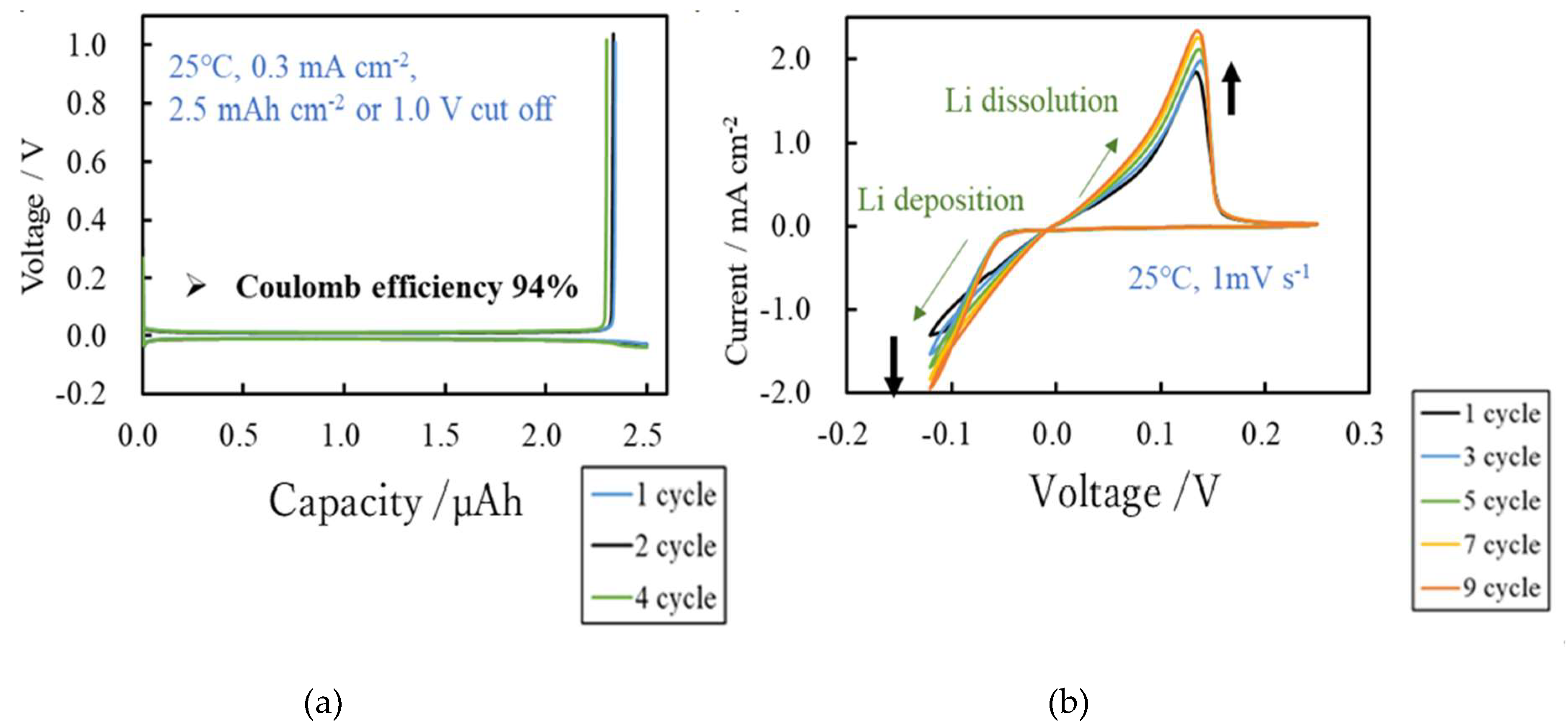

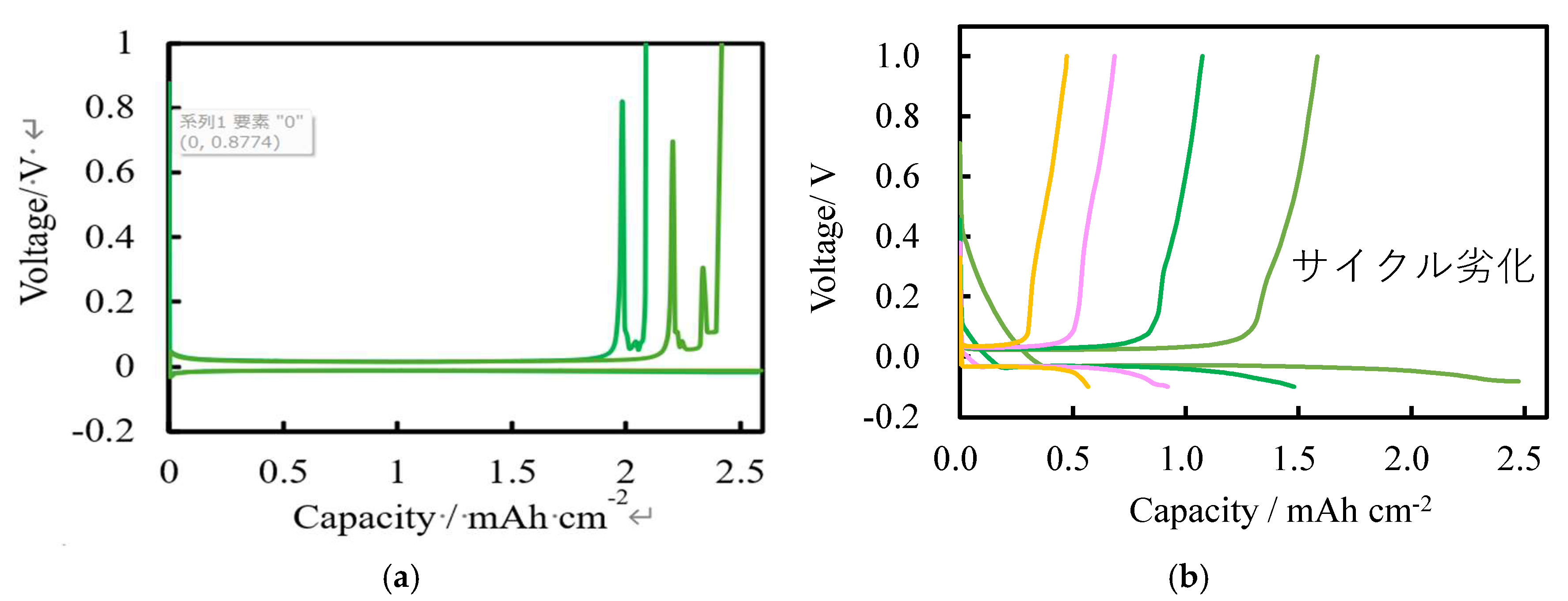

We demonstrate the potential of Lithium titanate (LiTiO) and amorphous titanium oxide (a-TiOx) thin films synthesized from titanium diisopropoxide bis acetylacetonate C16H28O6Ti [Ti(acac)2(OiPr)2] using atmospheric-pressure mist chemical vapor deposition method as negative electrode and solid electrolyte for anode-free lithium-ion battery (LIB). LTO thin films synthesized from Ti(acac)2(OiPr)2 and LiNO3 at 500 ℃ act as a negative electrode in LIB. In a-TiOx synthesized at 200-300 ℃, Li-ion permeability improved with charge/discharge cycles and acts as a solid electrolyte. The high diffusivity of Li ions demonstrated its superior behavior as a solid electrolyte. The a-TiOx solid electrolyte battery achieved an charge/discharge efficiency of 94%. These results imply that a-TiOx holds promise for realizing anode-free lithium metal batteries.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

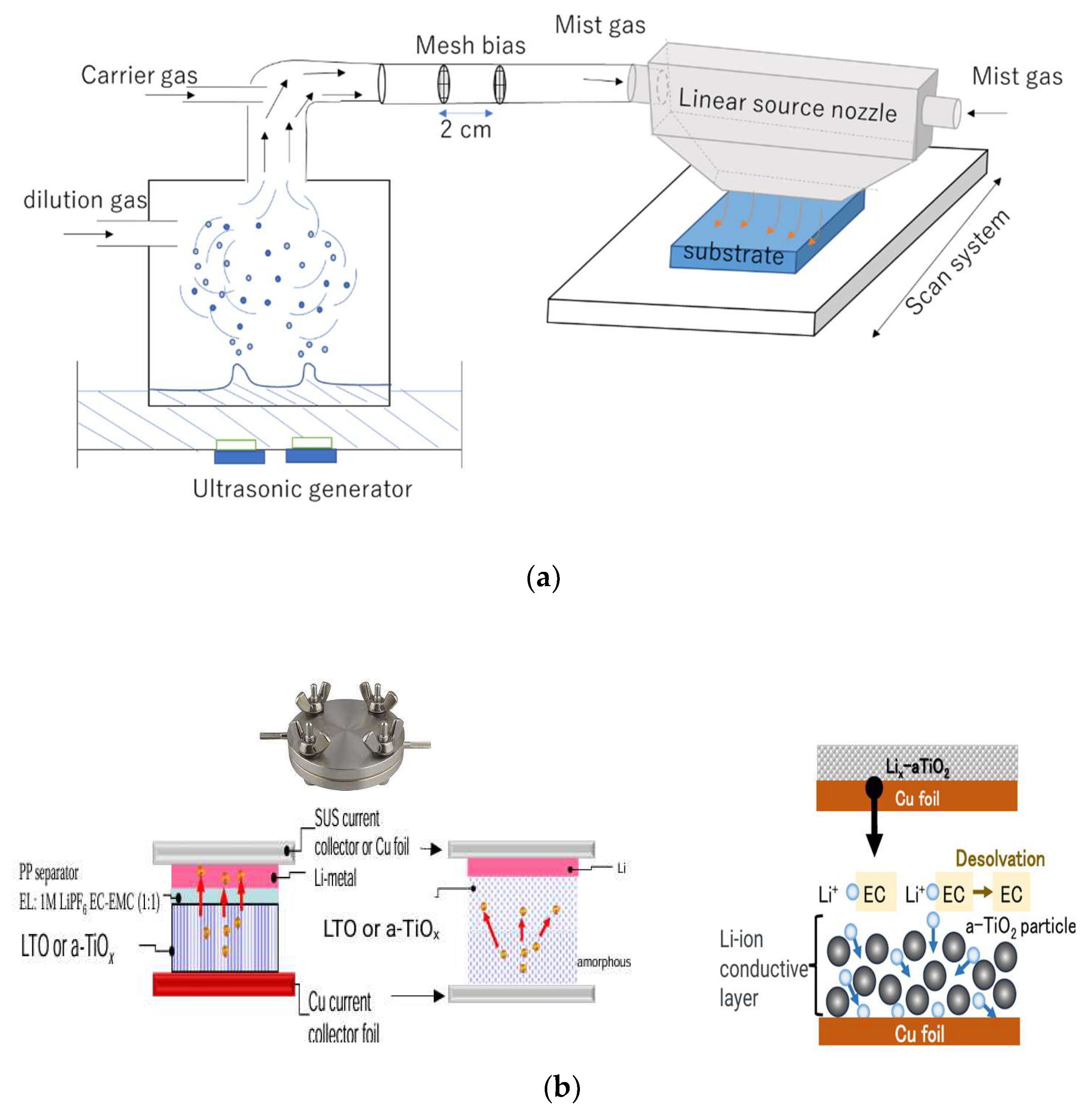

2. Materials and Methods

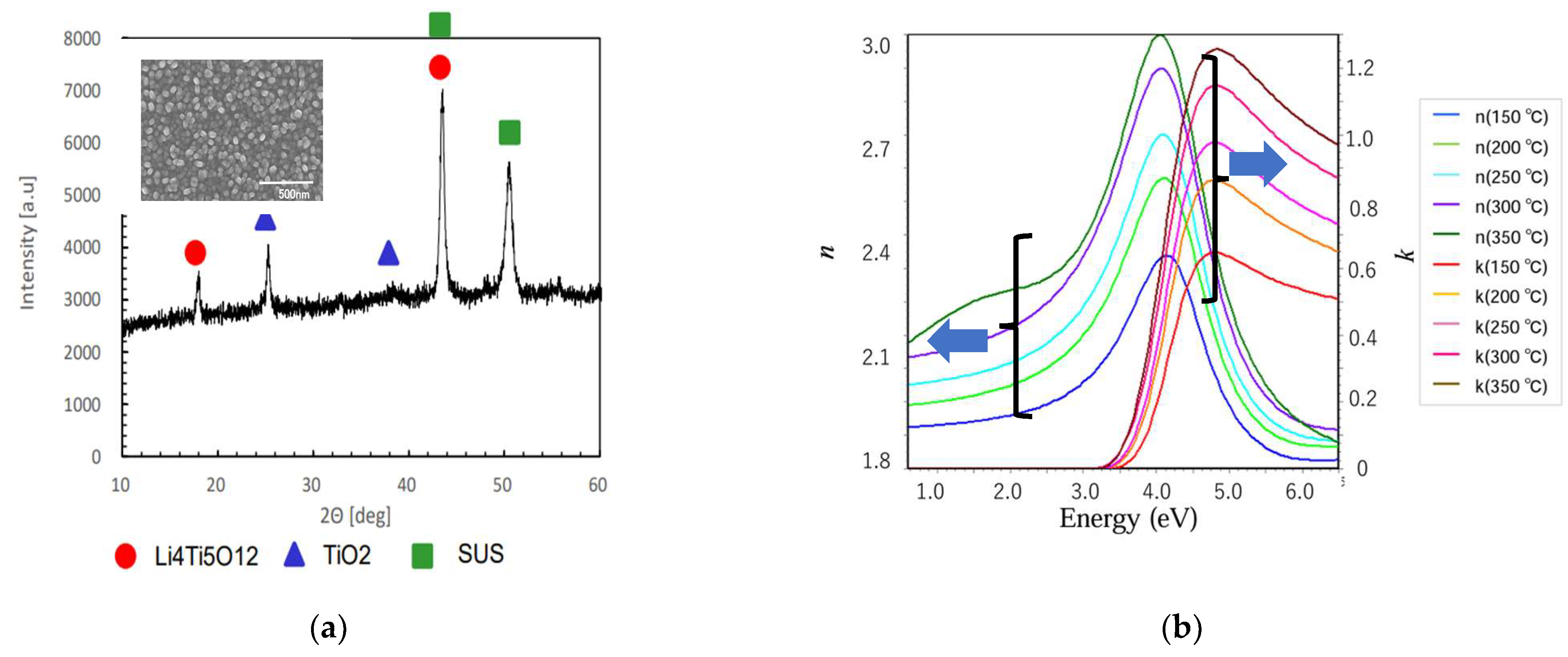

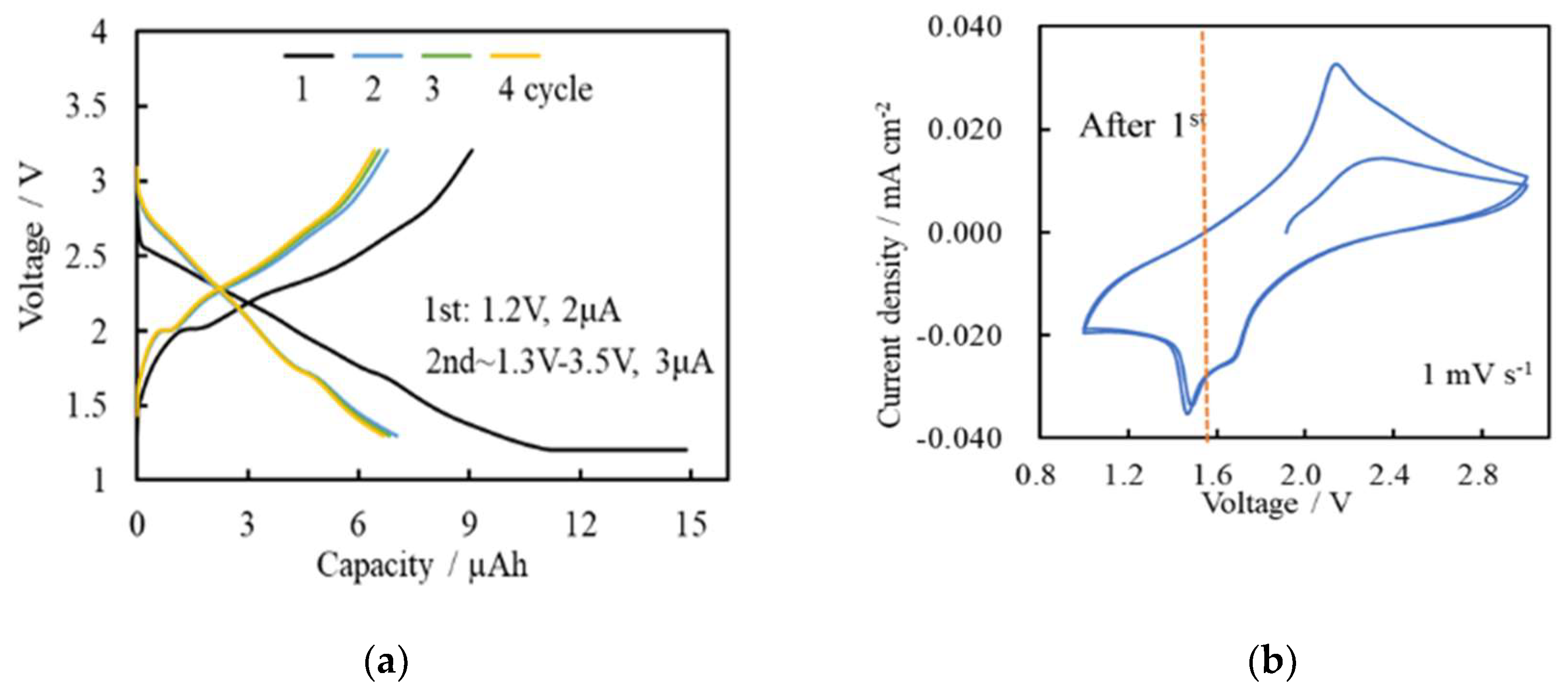

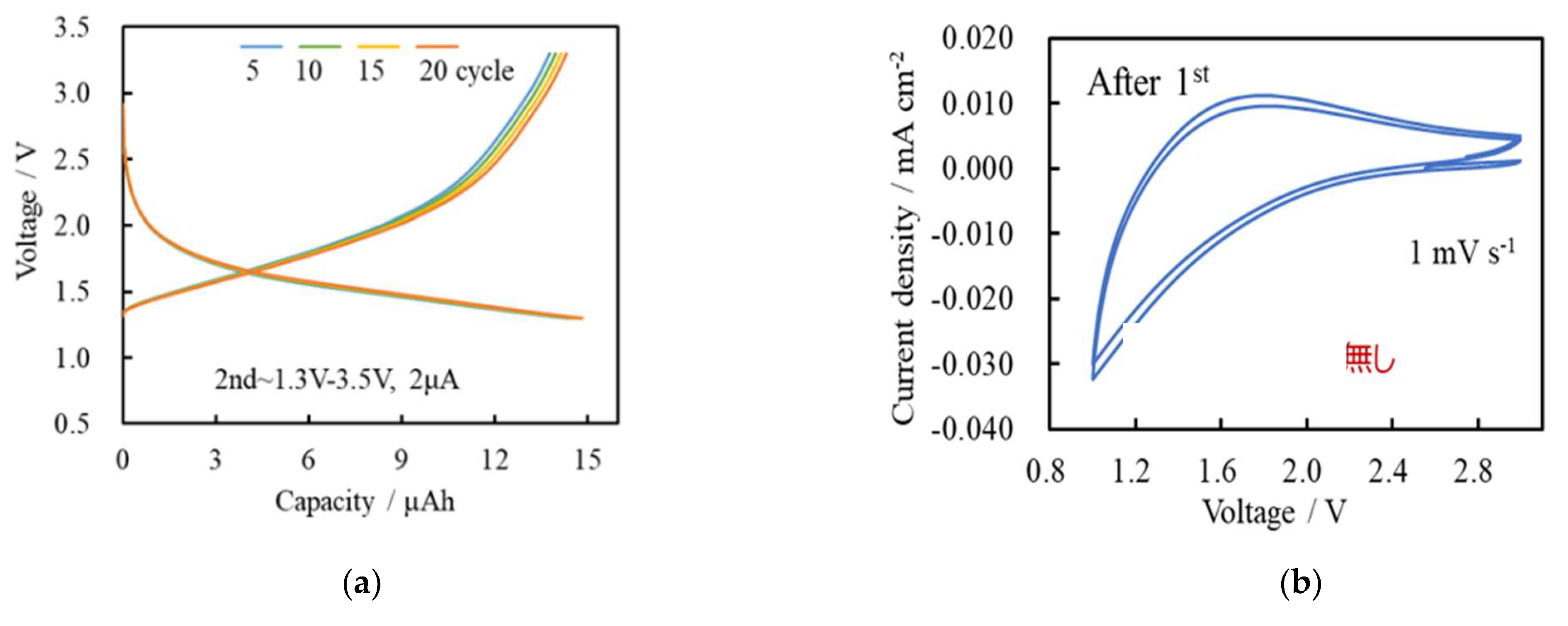

3. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, G.; Abrahama, C.; Ma, Y.; Lee, M.; Helfrick, E.; Oh, D.; Lee, D. Advances in Materials Design for All-Solid-state Batteries: From Bulk to Thin Films. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Li, Z.-B.; Wang, X.-L.; Zhao, X.-B.; Han, W-Q. Recent Advances in Inorganic Solid Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries Frontier Energy Res. 2014. 27 Sec. Electrochemical Energy Storage Volume 2. [CrossRef]

- M. Yashima, M. Itoh, Y. Inaguma, and Y. Morii. Crystal Structure and Diffusion Path in the Fast Lithium-Ion Conductor La0.62Li0.16TiO3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 3491–3495. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J. , Fast Li+ ion conducting glass-ceramics in the system Li2O – Al2O3 – TiO2 – SiO2 – P2O5. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1997, 80, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, R.; Thangadural, V.; Weppner, W. , Fast Lithium Ion Conduction in Garnet-type Li7La3Zr2O12. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed,. 2007, 46, 7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Bates, J.B.; Hart, F.X.; Sales, B.C.; Zuhr, R.A.; Robertson, J.D. , Characterization of Thin-Film Rechargeable Lithium Batteries with Lithium Cobalt Oxide Cathodes. J. Electrochemical. Soc., 1996, 143, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Seki, J.; Asaoka, T. , Electrochemical Performance of an All-solid-state Lithium Ion Battery with Garnet-Type Oxide Electrolyte. J. Power Sources 2012, 202, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, R.; Murayama, M. , Lithium Ionic Conductor Thio-LISICON: The Li2 S GeS2 P 2 S 5 System. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2001, 148, A742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Hori, S.; Saito, T.; Suzuki, K.; Hirayama, M.; Mitsui, A.; Yoneyama, M.; Iba, H.; Kanno, R. High-power All-solid-state Batteries using Sulfide Superionic Conductors. Nature Energy 2016, 1, 16030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaya, N.; Homma, K.; Yamakawa, Y.; Hirayama, M.; Kanno, R.; Yonemura, M.; Kamiyama, T.; Kato, K.; Hama, S.; Kawamoto, K.; Mitsui, A. , A Lithium Superionic Conductor. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, A.; Hama, S.; Minami, T.; Tatsumisago, M. , Fast Lithium-Ion Conducting Glass-Ceramics in the System Li2S-SiS2-P2S5. Electrochem. Commun. 2003, 5, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, S.; Tanibata, N.; Hayashi, A.; Tatsumisago, M.; Yamada, A. The Crystal Structure and Sodium Disorder of High-Temperature Polymorph β-Na3PS4. J. Mater. Chem. A., 2017, 5, 25025–25030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakari, T.; Sato, Y.; Yoshimi, S.; Hayashi, A.; Tatsumisago, M. Favorable Carbon Conductive Additives in Li3PS4 Composite Positive Electrode Prepared by Ball-Milling for All-Solid-State Lithium Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 162, A2804–A2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuda, A.; Hayashi, A.; Tatsumisago, M. Recent Progress on Interface Formation in All-Solid-State Batteries. Curr. Opin. Electrochem., 2017, 6, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, C.Y.; Mansergh, R.H.; Ramos, J.C.; Nanayakkara, C.E.; Park, D. -H. ; Ferron, S.G.; Fullmer, L.B.; Arens, J.T.; Gutierrez-Higgins, M.T.; Jones, Y.R.; Lopez, J.I.; Rowe, T.M.; Whitehurst, D.M.; Nyman, M.; Chabal, Y.J.; Keszler, D.A. Low-index, Smooth Al2O3 Films by Aqueous Solution Process, Optical Material Express 2017, 7, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, A.; Smecca, E.; Sanzaro, S.; Bongiorno, C.; Giannazzo, F.; Mannino, G.; Magna, A.L. Nanostructured TiO2 Grown by Low-Temperature Reactive Sputtering for Planar Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 2, 6218–6229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H. -Q.; Xu, H.; Zhou, Y. -N.; Lu, F.; Fu, Z. -W. Electrochemical Characteristics of Al2O3-Doped ZnO Films by Magnetron Sputtering. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.H.; Lee, S.H.; Joo, S.K. , Characterization of Sputter-deposited LiMn2O4 Thin Films for Rechargeable Microbatteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1994, 141, 3296–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamala, K.S.; Murthy, L.C.S.; Radhakrishna, M.C.; Rao, K.N. Characterization of Al2O3 Thin Films Prepared by Spray Pyrolysis Method for Humidity Sensor. Sens. Actuators A 2007, 135, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, A.; Jiang, Q.H.; Lina, Y.H.; Nan, C.W. , Lithium Lanthanum Titanium Oxide Solid-State Electrolyte by Spark Plasma Sintering. J. Alloys Compounds 2009, 486, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Chu, H.P.; Hu, X.; Yue, P. -L. Preparation of Heterogeneous Photocatalyst (TiO2/Alumina) by Metal-Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1999, 38, 3381–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.K.; Won, S.O.; Park; Y. ; Kim, J.; Park, T.J.; Kim, S.K. Atomic-layer deposition of TiO2 Thin Films with a Thermally Stable (CpMe5)Ti(OMe)3 Precursor. Appl Surf Sci. 2021, 550, 149381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelofs, K.E.; Brennan, T.P.; Dominguez, J.C.; Bailie, C.D.; Margulis, G.Y.; Hoke, E.T.; McGehee, M.D.; Bent, S.F. Effect of Al2O3 Recombination Barrier Layers Deposited by AtomicLayer Deposition in Solid-State CdS Quantum Dot-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 5584–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Zhang, T.F.; Lee, H. -B. R.; Yang, J.H.; Choi, W.C.; Han, B.; Kim, K.H.; Kwon, S. -H. Improved Corrosion Resistance and Mechanical Properties of CrN Hard Coatings with an Atomic Layer Deposited Al2O3 Interlayer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 26716–26725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrysson, C.E.; Pitt, C.W. Al2O3 Thin Films by Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapour Deposition Using Trimethyl-Amine alane (TMAA) As the Al Precursor. Appl. Phys. A 1997, 65, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, Y.H.; Kanamura, K. Fabrication of thin film Electrodes for All Solid State Rechargeable Lithium Batteries, J. Electroanal. Chem. 2003, 559, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, Y.; Kanamura, K. Solid State Chem. Solid State Chem. 2003, 559, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, K. -T.; Kim, H. -Y.; Kim, D. -H.; Hwan Han, J.H.; Park, J.; Park, J. -S. Facile Synthesis of AlOxDielectrics via Mist-CVD Based on Aqueous Solutions. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 8932–8937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, T.; Kawaharamura, T.; Shibayama, K.; Hiramatsu, T.; Orita, H.; Fujita, S. Mist Chemical Vapor Deposition of Aluminum Oxide thin Films for Rear Surface Passivation of Crystalline Silicon solar cells. Appl. Phys. Express 2014, 7, 021303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaharamura, T.; Uchida, T.; Sanada, M.; Furuta, M. Growth and Electrical Properties of AlOx Grown by Mist Chemical Vapor Deposition. AIP Adv. 2013, 3, 032135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajib, A.; Enamul, K.; Kuddus, A.; Ishikawa, R.; Ueno, K.; Shirai, H. Synthesis of AlOx Thin Films by Atmospheric-pressure Mist Chemical Vapor Deposition for Surface Passivation and Electrical Insulator Layers. Journal Vacuum Science & Technology 2020, A38, 033413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajib, A.; Kuddus, A.; Shida, T.; Ueno, K.; Shirai, H. Mist Chemical Vapor Deposition of AlOx Thin Films Monitored by a Scanning Mobility Particle Analyzer and its Application to the Gate Insulating Layer of Field-effect Transistors. ACS Applied Electronic Materials 2021, 3, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajib, A.; Kuddus, A.; Yokoyama, K.; Shida, T.; Ueno; K. ; Shirai; Mist, H. Chemical Vapor Deposition of Al1-xTixOy Thin Films and Their Application to a High Dielectric Material. J. Applied Physics. 2022, 131, 105301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, K.; Kuddus, A.; Shirai, H. Mesh-bias Controlled Synthesis of TiO2 and Al0.76Ti0.24O3 Thin films by Mist Chemical Vapor Deposition and Applications as Gate Dielectric Layers for Field-Effect Transistors. ACS Applied Electronic Mater. 2022, 4, 2516–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadanaga, K.; Yamaguchi, A.; Hayashi, A.; Tatsumisago, M.; Mosa, J.; Aparicio, M. Preparation of Li4Ti5O12 electrode thin films by a mist CVD process with aqueous precursor solution. J. Asian Ceramic Soc., 2015, 3, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadanaga, K.; Yamaguchi, A.; Sakuda, A.; Hayashi, A.; Tatsumisago, Duran, A. ; Aparicio, Preparation of LiMn2O4 Cathode Thin Films for Thin Film Lithium Secondary Batteries by a Mist CVD Process. Mater. Res. Bul. 2014, 53, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igawa, T.; Kaneko, K.; Fujita, S. Fabrication of Lithium-based Oxide Thin Films by Ultrasonic-Assisted Mist CVD Technique. J. Soc. Mater. Sci., Japan 2011, 60, 994–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, M.; Kim, K.; Toujigamori, T.; Cho, W.; Kanno, R. Epitaxial growth and electrochemical properties of Li4Ti5O12 thin-film lithium battery anodes. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 2882–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohzuku, K.; Ueda, A.; Yamamoto, N. Zero-Strain Insertion Material of Li[Li1/3Ti5/3]O4 for Rechargeable Lithium Cells. J. Electrochem.Soc. 1995, 142, 1431–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amine, K.; Belharouak, I.; Chen, Z.; Tran, T.; Yumoto, H. Ota, N.; Myung, S.T.; Sun, Y.K. Nanostructured Anode Material for High-power battery System in Electric Vehicles. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 3052–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, M.; Thijs, M.; Ooms, F.G.B.; Ganapathy, S.; Wagemaker, M. High Dielectric Barium Titanate Porous Scaffold for Efficient Li Metal Cycling in Anode-free cells. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cheng, X.; Cao, T.; Niu, J.; Wu, R.; Liu, X. Zhang, Y. Constructing ultrathin TiO2 protection layers via atomic layer deposition for stable lithium metal anode cycling, Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2021, 865, 158748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Solute | Ti(acac)2(OiPr)2 |

| Li source | LiNO3, (CH3COO)Li, LiCl |

| Solvent | CH3OH |

| Solution concentration | 0.015 mol/L |

| Substrate temperature; Ts | LTO; 500- 550 ℃, a-TiOx; 200- 350 ℃ |

| Substrate | p-Si, SUS, Cu foil (180 µm) |

| Mist generation gas | N2, Ar: 500 sccm |

| Dilution gas flow; Fd | N2, Ar: 2400 sccm |

| Repetition cycle; N | 1 - 30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).