1. Introduction

Soils of the tropical and, partly, subtropical bioclimatic zones differ significantly from soils of other geographical zones. First of all, it is connected with differentiation of substance and energy flows by vertical stratification of a plant communities. The ecosystems of boreal and sub-boreal forests seem to be very simply organized compared to the terrestrial ecosystems of the humid tropics. Tropical soils are not included in the classical zonal soil cover scheme proposed by V.V. Dokuchaev [

1], which can be considered as a predictor of their separate study as an isolated biogeochemical phenomenon. At the same time, mineral terrestrial soils of the tropics are studied in details [

2,

3,

4].

This cannot be argued about suspended soils (which are also called canopy soil), the studies of which are numbered in the first dozens. Suspended soils are not soils in the classical sense and definiton. In them, the organic part dominates over the sparse mineral part. In other words, the skeleton of the soil is not the mineral part, but organic plant residues, forming small epiphytic clusters, baskets, mats and even small suspended bogs on different elevation tropical forest tiers. These soils, as it was shown by different authors, are characterized by specific morphological organization, peculiarities of chemical composition, unique microbial communities. The physical properties and chemical composition of these soils has received negligible attention, unlike mineral terrestrial soils of the tropical belt [

5,

6].

Epiphytes are characterized by different ways of forming suspended soils. In some epiphytes, soils are formed under the clump itself, for example, in mosses or

Hymenophyllum ferns. Very often, ants settle in the epiphyte clump, playing an important role in the genesis of suspended soil [

7]. In the case of “nested” epiphytism, litter is captured by a funnel of leaves, and the growth of roots, forming a powerful lump of soil around the root system, visually resembles a bird's nest. In our study, this group of epiphytes includes, for example, the ferns

Asplenium nidus, Microsorum punсtatum and the flowering epiphyte

Hedychium bousigonianum. “Bracket” epiphytes use a similar mechanism, forming funnels for collecting litter and rainwater with the help of specialized bracket leaves [

8,

9]. In the genera of epiphytic ferns

Drynaria, Platycerium and

Aglaomorpha, the role of “brackets” is played by rigid fronds of a special morphology, the living tissues of which die off early, but the fronds themselves or their bases remain on the plant for many years. In some cases, nesting epiphytes (mainly some orchids and aroids) form special adventitious roots with negative geotropism, which act as a “brush” in which litter gets stuck – impoundment roots [

10]. In our study, the orchid

Cymbidium finlaysonianum belongs to this type of epiphytes. Nesting epiphytes with these roots, as well as other adaptations for retaining water and litter, are persistently called “trash-basket” [

8]. In the course of our research, we found that impoundment roots usually lack meristems, have a pronounced determinate growth and possess special mechanical strength due to the modification of stele cells [

11]. Thus, epiphytes have a wide range of adaptations that allow them to act as edificatory role of the environment of tropical tree crowns and accumulate suspended soil massifs in it.

Nevertheless, the main hydrologic properties of these soils are important not only for the processes in the soil mass itself, but also for the regulation of tropical forest mesoclimate. When water accumulates in all tiers, it promotes humidization of the whole landscape, makes it more eluvial and forms a specific biogeochemical regime. Importantly, the low water-holding capacity of tropical soils may also influence the formation of monospecific forest communities in Amazonian rainforests [

12]. Smagin et al. [

13] points out the hydrological and soil-hydrophysical role of plant detritus in the formation of water-holding capacity of boreal ecosystems. This phenomenon may play an essential role in tropical ecosystems. These authors have shown that the physical mechanism of detritus hydrological function is the formation of capillary barriers that block evaporation and capillary resorption of moisture in forest litter and peat, and this soil property can be used to construct artificial soils. As we indicated earlier [

14], suspended soils are a unique biotechnological model for sequestering carbon from organic compounds. They can also be a very informative model for vertical gardening systems; in particular, they can be used to predict the behavior of water in urban vertical ecosystems. Murray et al. point to a certain climate-regulating ability of suspended soils at the local level, reporting that suspended soils regulate not only humidity, but also temperature [

15]. Special interest represents also investigation of water retention capacity of suspended soil in afforested territories in artificial trees plantations of South Vietnam [

16]. In addition, their chemical composition has hardly been studied in the context of their origin in different ecosystems and different types of epiphytes. Suspended soils functionally are comparable with Histosols or peat materials in terms of water holding capacity. These soils are “extraordinary” [

17], and represents separate branch of soil formation presented by intensive accumulation of organic matter. In current Russian soil taxonomy [

18] peat soils are separated from other soils in special classification trunk of “organogenic soils”, which could be oligotrophic and eutrophic, dependly on source of nutrition and mineral particles origin.

This, taking into accounts the supposed importance of the ecosystem role of suspended soils, we have undertaken a large-scale study of their chemical and hydrological parameters from different ecosystems of 5 national parks of South Indochina: from mangrove to moss forest. The main objective of the study was to find out whether the chemical composition and hydrological parameters depend significantly on the genesis of suspended soil, or they represent a single soil phenomenon with a certain supposed ecosystem function. To do this, we studied their hydrological properties, chemical composition of macro- and microelements, heavy metals, and the isotopic composition of carbon and nitrogen.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Studies

Field studies were conducted in southern Indochina in 2015 – 2022 in five different environments (

Figure 1). The first habitat was open savanna-like forest on oligotrophic mineral soils (Phu Quoc, Vietnam). Phu Quoc Island, located in the Gulf of Siam, has a subequatorial, tropical monsoon (Am) climate [

11]. Sampling plots with a total area of several hectares were located not far from both shores of the island (within 0.5 – 3 km), around the line between 10°16′46″ N, 103°55′23″ E and 10°24′17″N, 104°03′02″ E, (altitude 0 – 1.5 m a.s.l.). Average trees height was 5 − 7 m. Trees were widely spaced, the herb layer poorly developed and alternated with large areas of bare soil. Many trees were infected by hemiparasites from Loranthaceae and Viscaceae families (three species). The following samples were examined from this habitat: - 2/7 collected from the epiphytic orchid

Cymbidium finlaysonianum; 3/7 from fern

Asplenium nidus; 3/8 from fern

Microsorum puncatum; 3/10 from

Drynaria quercifolia fern; 3/14 from

Platycerium coronans fern.

The second plot investigated was Con Dao Island (Vietnam) located opposite the mouth of the Megong River, 100 km from the coast. Despite the fact that there is a national park on the island, this place is very poorly explored. We found that epiphytes were almost absent on the island and a small epiphytic community was present only in the coastal dry dipterocarp forest on the sand dunes near 8°39'13.5"N 106°36'14.3"E. The following samples are collected here: 3/1 and 3/6 from the fern Drynaria bonii; 3/2 and 3/11 from the fern Davallia sp.

The third habitat investigated was lowland forest (Cat Tien, Vietnam). Cat Tien National Park is located in the lowlands of Dong Nai province. It has subequatorial monsoon climate [

19]. The sample plot occupied approximately 1 hectare around the point 11°26'14"N and 107°25'26"E (≈ 120 m asl). Canopy trees height reached 30-35 m. Here we collected the following specimens: 2/2 from the fern

Asplenium nidus; 2/4 from

Drynaria quercifolia fern; 2/6 from epiphytic ginger

Hedychium bousigonianum; 3/12 from the fern

Microsorum punсtatum and 3/13 from under a mixed cushion of aroid

Remusatia vivipara and epiphytic orchids.

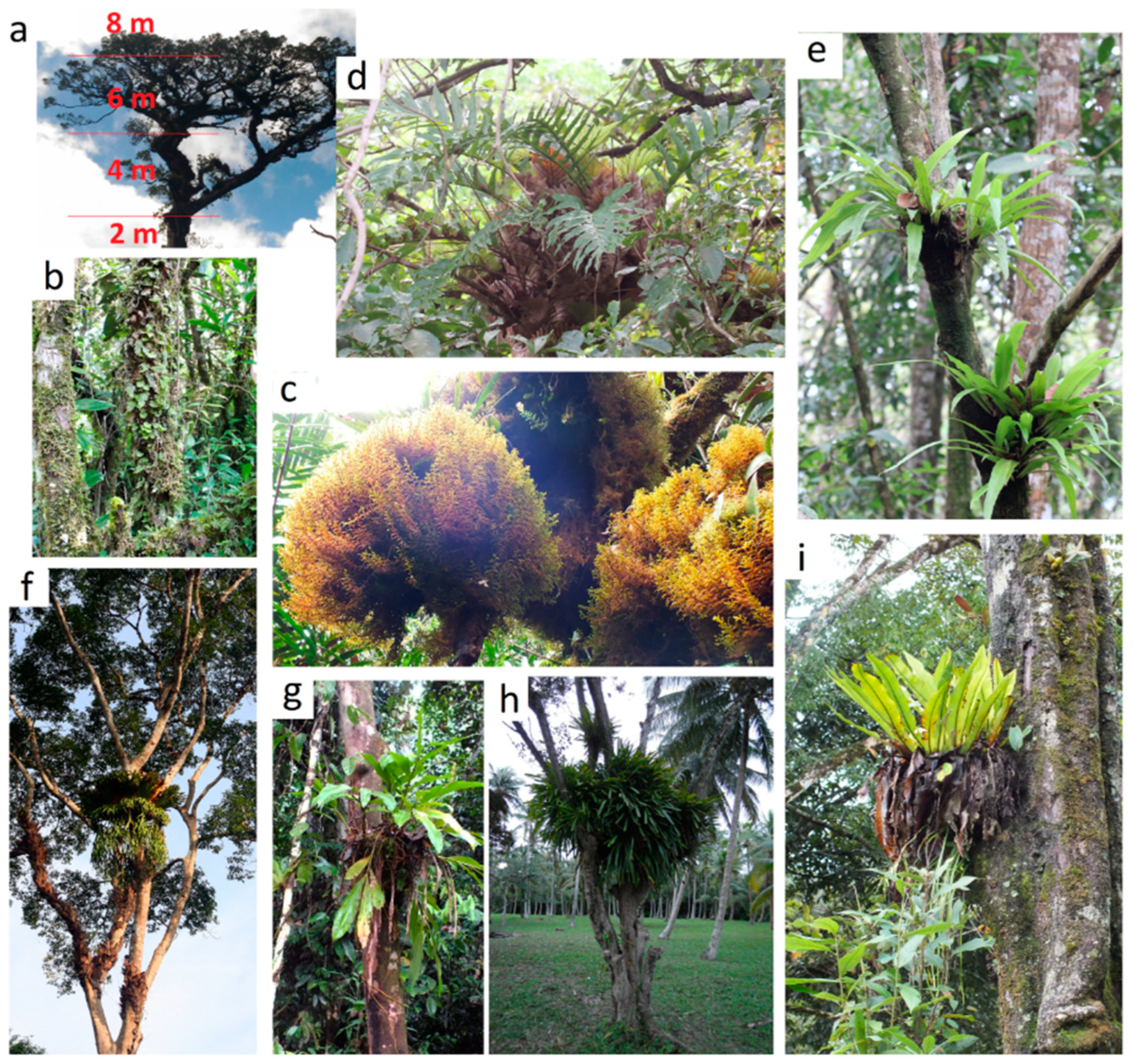

The fourth habitat was montane forest (Bidoup, Vietnam). Bidoup Nui Ba National Park is located at Da Lat Plateau. Its climate is much wetter and cooler than in neighbouring plains of southern Vietnam. Materials were collected at Hon Giao mountain top (≈ 2000 m asl), in a stunted, one-layered cloud forest, from a plot of several hectares around the point 12°11'24"N and 108°42'38"E. Average trees height was 5 − 8 m. From here the following samples were collected: from one tree they were collected from bottom to top - 1/1 from 1 tier at a height of up to 2 m, 1/2 from 2 tier 4 m, 1/3 from 3 tier 6 m, 1/4 from 4 tier over 6-8 m. 2/1 Moss cushion in a moss forest, 2/3 from the fern Aglaomorpha sp., 2/5 from the epiphytic heather Vaccinium sp.

And finally, the fifth habitat was on the top of the mesas of Phnom Bokor (Preah Monivong National Park) in Cambodia, this southern tip of the Elephant Mountains is in direct line of sight from the island Phu Quoc (Vietnam) around the point 10°39'27.9"N 103°59'33.0"E. At an altitude of about 1000 m. Despite the relatively low altitude, the warm air rising from the sea and reaching the plateau cools sharply, because of this, moss forests develop on the edge of the plateau and, a little further into the plateau, low crooked forests reminiscent of kerangas. Here we collected samples 3/5 from under the pillows of the fern

Hymenophyllum sp., 3/3 and 3/4 from the fern

Aglaomorpha sp., 3/9 from the Moss pillow in the moss forest (

Figure 2).

All studied habitats are located relatively close to each other; however, due to different heights and complex terrain, they differ in both the diversity of climate and the diversity of underlying soils. These data are shown in

Table 1.

2.2. Laboratory Analysis

Soil samples were delivered to the laboratory of the Department of Applied Ecology, St. Petersburg State University. Further, the soils were grounded in a mill and sieved through a sieve with mesh diameters of 2 mm. Thus, conditional fine soil was used for analysis, although, of course, it is fine soil only by the size of the ground soil. This ensured the comparability of the results of the study of all samples, because initially, the organic substrates of the suspended soils consisted of different-sized plant residues of different degrees of decomposition.

Chemical analysis. The pH values were determined using the pH analyzer by the potentiometric method [

20].The elemental composition of HAs was determined on a CHN analyzer (EA3028-HT EuroVector, Pravia, PV, Italy). Oxygen content was calculated from the following equation (with taking to account ash content):

The content of ammonium nitrogen (N-NH

4) and nitrate-nitrogen (N-NO3) was determined using the potassium chloride solution [

21]. The content of potassium (K

2O) and phosphorus (P

2O

5) was determined by the Kirsanov method [

22]. The method is based on the extraction of mobile compounds of phosphorus and potassium from the soil with a solution of 0.2 M HCl (1:5) with photocolorimetric or flame-photometric determination of nutrient concentrations. For organomineral horizons, the determination of the main nutrients was repeated three times. Laboratory tests were performed in certified laboratories. Measurement control was carried out with standardized soil samples (samples with known physical and chemical parameters). Exchangeable form of Ca and Mg was determined by titration with use of trilonometry [

23]. The content of trace metals was determined following to the standard ISO 11047-1998 “Soil Quality-Determination of Cadmium (Cd), Cobalt (Co), Copper (Cu), Lead (Pb), Nickel (Ni) and Zinc (Zn) in Aqua Regia Extracts of Soil–Flame and Electrothermal Atomic Absorption Spectrometric” method at Atomic absorption spectrophotometer Kvant 2M (Moscow, Russia). According to this methodology and the instrument’s datasheet, the lower detection limit for the metals to be detected is as follows: Pb—0.05; Cr—0.02; Cu—0.01; Cd—0.005; Ni—0.02; Zn—0.01. Standard samples of solutions with metal concentrations from 0.1 to 2 mg × cm

−3 were used to calibrate the spectrophotometer [

24]

Hydrological analysis. The key soil hydrophysical characteristics of soils are hygroscopic water content (HM), maximum hygroscopic water content (MHW), maximum water holding capacity (MWHP), field moisture capacity (FMC). Hygroscopic water content was determined gravimetrically by determining the weight difference between air-dry soil and soil dried to constant weight in a thermostat at 105 ℃. The MWHP and FMC are usually determined in the field using the column or floodplain experimental plot method. For suspended soils this is not technically possible due to their specific nature. Therefore, we determined these parameters in laboratory conditions in plastic columns 20 cm high and 7 cm in diameter. These columns were filled with soil, the bottom of the column was covered with 5 filter paper on a rubber band and placed in a container filled with water up to a height of 10 cm. FMC characterizes the maximum possible amount of vaporous water that the soil can absorb from air almost saturated with water vapor. The method is based on prolonged saturation of soil with water vapor in the desiccator and further gravimetric determination of the mass of sorbed water layer. All these methods are described in manual of Rastvorova [

25].

Stable isotope analysis. Dried samples were pulverized in the Retsch MM 200 mill and wrapped in tin foil. Sample weight of plant material was about 1500 μg, of soil up to 3000 μg. Isotopic composition of N and C was measured using Thermo Flash 1112 elementary analyzer and Thermo Delta V Plus isotopic mass-spectrometer at the Joint usage center at the A.N. Severtsov

Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Moscow. The isotopic composition of N and C was expressed in the δ-notation relative to the international standard (atmospheric nitrogen and VPDB, respectively):

where R is the ratio of the heavier isotope to the lighter isotope. Samples were analyzed with reference gas calibrated against the IAEA reference materials USGS 40 and USGS 41 (glutamic acid). The drift was corrected using the internal laboratory standards (casein, alfalfa). The standard deviations of the δ

15N and δ

13C values of reference materials (n=8) were <0.2‰. Along with isotopic analyses, nitrogen and carbon contents (as mass %) and mass C/N ratio were determined in all samples.

2.3. Statistics

The relationship (linear regression) between various parameters soil-hydrological constants was visualized in the Statistics package. Multivariate comparisons performed by One-way ANOVA. In order to identify general patterns in the elemental composition of the suspended soils, we performed ordination using the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) method for 22 features using the Euclidean distance. In order to normalize the distribution of variables, the data were transformed to the base of the natural logarithm with the addition of a constant or logit transformation (percentage values of the content of C, N, H, O). Before analysis, all data were centered and scaled. The number of significant axes for interpretation was determined using the Broken stick diagram.

We compared suspended soils from different groups of epiphytes in pairs using PERMANOVA (permutational multivariate analysis of variance, the "adonis" function in the "vegan" package) for the entire set of features, and separately for each soil parameter using the Fisher-Pitman permutation test for two samples with Monte Carlo approximation in the "coin" package.

We also tried to identify groups of suspended soils using cluster analysis and compare them with the plants where they formed and the area of material collection. However, different methods of cluster analysis (single linkage agglomerative clustering, complete linkage agglomerative clustering, unweighted par-group method using arithmetic averages, Ward’s minimum variance clustering, and k-means partitioning) did not reveal clusters that clearly reflect the taxonomic position of epiphytes or the area of material collection.

Differences in δ

13C and δ

15N values were compared between suspended soils and other elements of the tropical ecosystem. A total of 12 types of objects were compared: suspended soils, terrestrial soils, phorophyte plants, terrestrial herbaceous plants, lithophytes, accumulative, succulent, carnivorous, myrmecophilous and avascular epiphytes, semiparasites and hemiepiphytes. Differences were detected using the Fisher-Pitman permutation test for several samples with Monte Carlo approximation, followed by pairwise multiple comparisons with false discovery rate control correction in the “coin” and “rcompanion” packages [

26,

27]. For the sample, data on other objects were used that formed the basis of our earlier studies [

28,

29]

3. Results

Hydrological parameters. Based on statistical processing of the obtained data, the highest coefficients of determination between SOC content and hydrologic properties are observed between SOC/HM and SOC/MHW (

Figure 3). In some cases, the relationship is close to functional, for example, between SOC and MHW for suspended soil samples from Con Dao and Phnom Bokor R2 0.99 and 0.97, respectively (p <0.0001). The relationship between SOC and MHW for samples collected from Bidoup and Cat Tien was also observed, a positive relationship was found between these characteristics (R2 0.22 and 0.48 respectively, p < 0.05). However, it was found that a relationship may not be observed for similar characteristics (Phu Quoc - R2 <0.01, p < 0.05). The relationships between SOC and MWHP/FMC are multidirectional, with R2 varying widely with no general trend evident for all sampling locations.

When analyzing the full data set (

Figure 4), high R2 coefficients of determination were found between SOC and HM - 0.57 (p < 0.0001), SOC and MHW - 0.33 (p < 0.0001) which may be associated with the capacity of suspended soils to soak up vaporous atmospheric moisture from the environment under the high humidity conditions typical of tropical forests. No relationship was found between MWHP/FMC, R2 < 0.11 at significance level p < 0.05. Multivariate comparisons by One-way ANOVA (

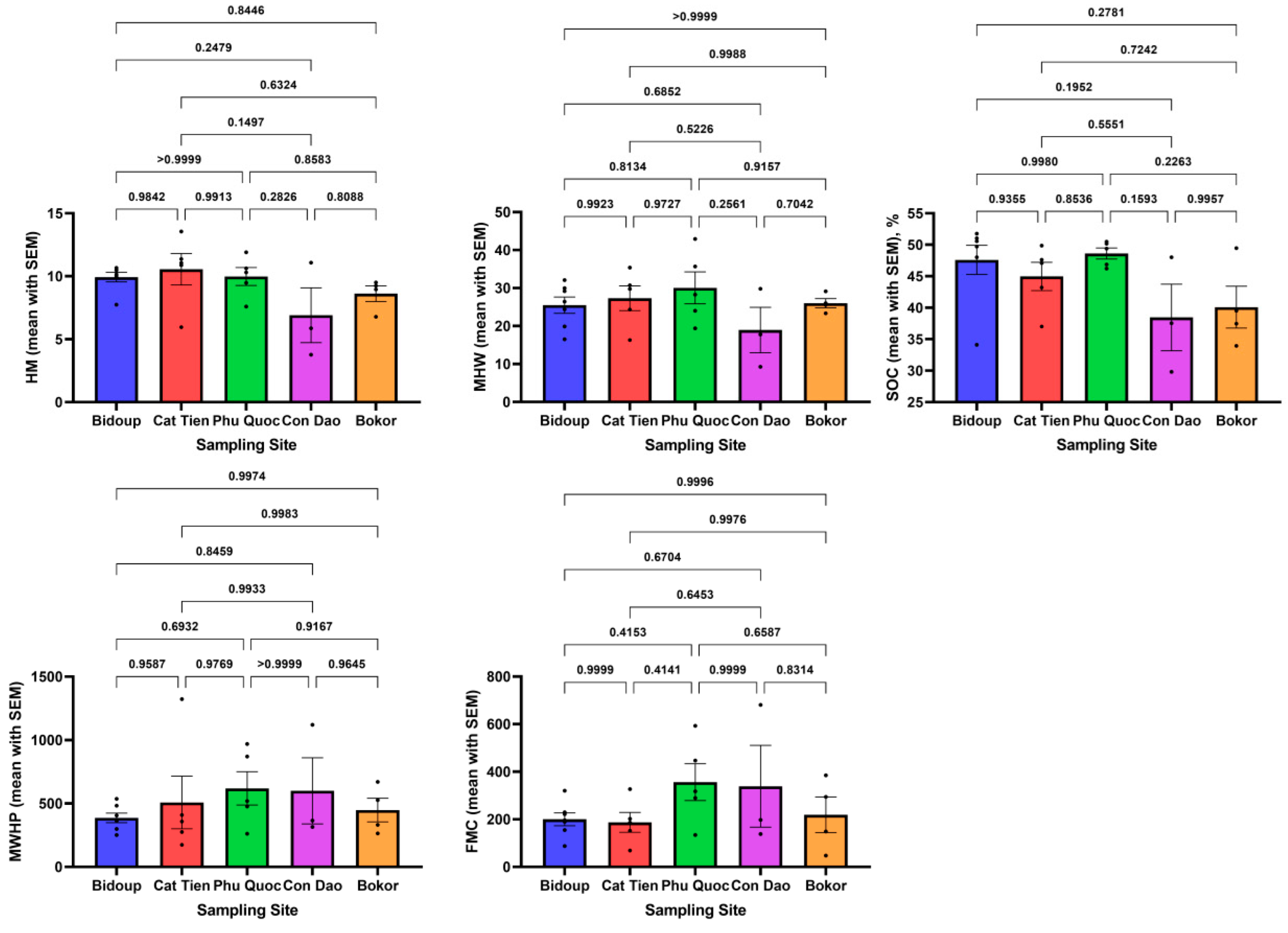

Figure 5) showed no significant differences between mean values of hydrologic properties and SOC (p > 0.05) for all studied suspended soils from different sampling locations.

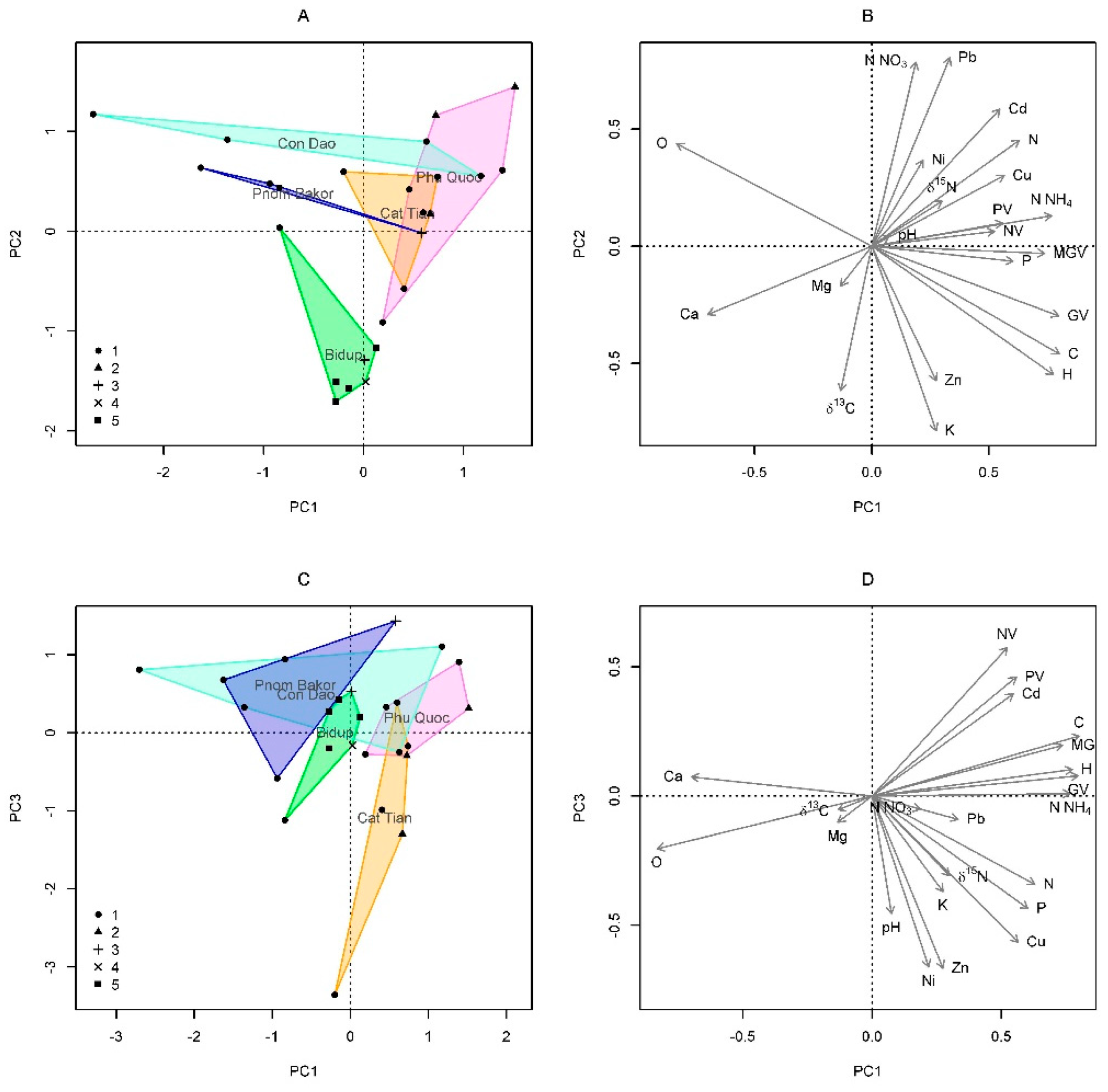

General patterns of elemental composition of suspended soils of epiphytes. The results of ordination by the principal component method showed that the first three principal components explained 60.1% of the variation in the properties of suspended soils (

Table 2). The first axis was positively reated with moisture values, the content of mobile phosphorus and ammonium nitrogen, and negatively with the percentages of calcium (

Figure 6). Along the second axis, the content of nitrate nitrogen and heavy metals (Pb) increased, and the content of Zn, K decreased, as well as the values of δ13 C, which became more negative (

Figure 6). Along the third axis, the pH values, as well as the content of Ni and Zn, decreased. According to the set of attributes, suspended soils collected from orchid, fern and moss cushions did not differ significantly from each other. However, fern composed soils contained significantly more lead Pb (p=0.020) than orchid soils, and the C:N ratio was higher in moss cushion soils than in orchid soils (p=0.024). For other traits, these groups did not differ significantly, possibly due to the small sample size of mosses and ferns. Spearman's correlation coefficients were calculated between all traits.

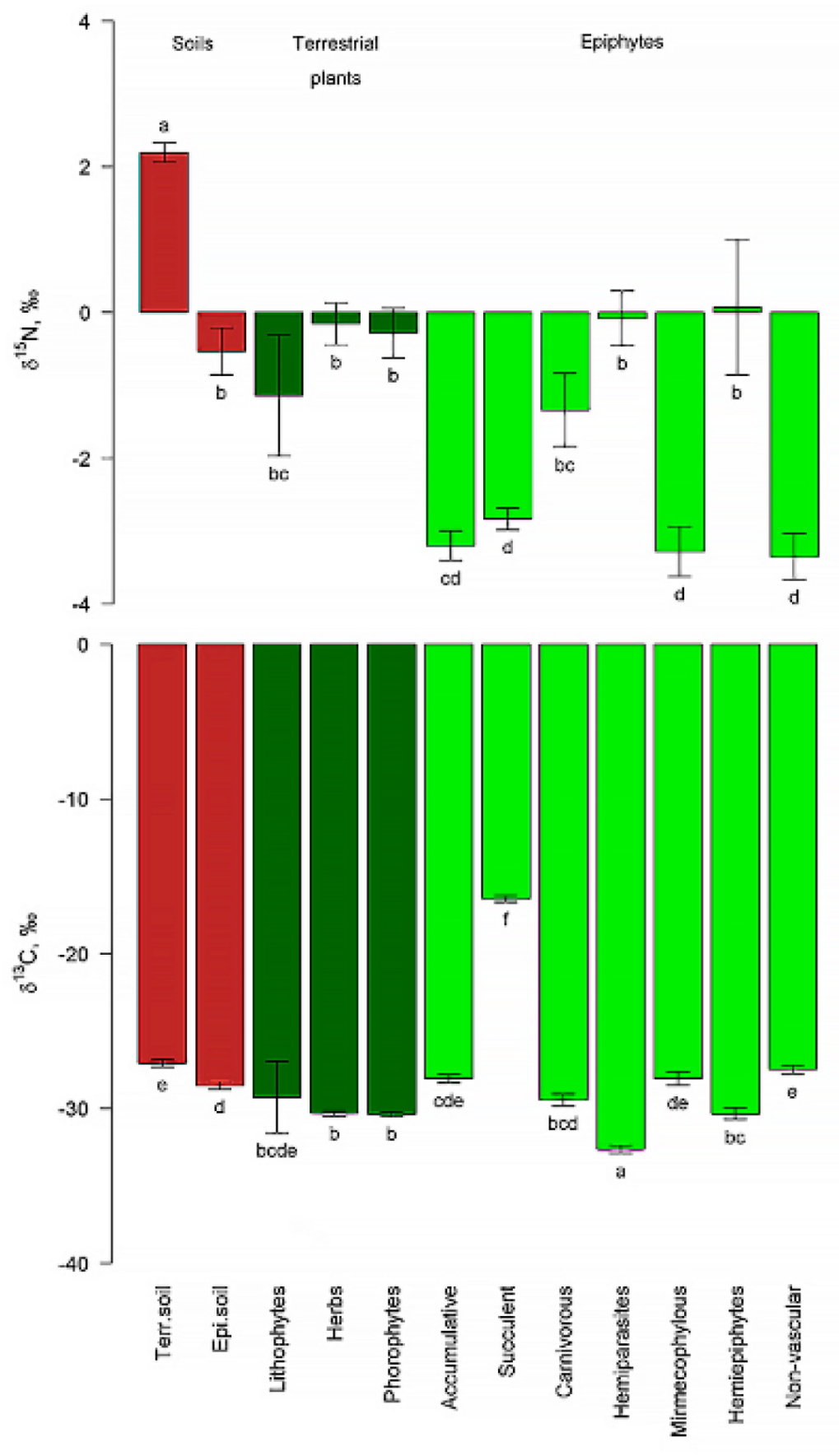

Stable isotope. The isotopic composition of carbon in suspended soils differed significantly from terrestrial soils and phorophytes, but, as expected, did not differ from accumulative epiphytes (around which suspended soil is formed) and ecobiomorphs close to them: myrmecophylls and carnivorous epiphytes. The isotopic composition of nitrogen did not differ significantly from terrestrial plants and differed significantly from typical epiphytes. The greatest difference in δ15N was observed in suspended soils from terrestrial soils, with the signature of the latter being the only one giving positive δ15N values (Figure. 7).

4. Discussion

The carbon content of organic compounds in all studied materials was high. In general, this corresponds to the assumption of E.V. Dmitriev about organic soils as a special “extraordinary” type of soil formation [

17] where organic matter dominates over mineral matter. Moreover, if the carbon content is 40-50%, then the remaining part is far from mineral, since it is represented by hydrogen, nitrogen, as well as ash elements of various compositions. The opposite of these soils are Ahumic soils or Regoliths, i.e., humus-free or mineral soils, described as typical, primarily for the ecosystems of Antarctica [

30]. These soils, along with organic soils, form two final stages of one series of soils and are equally different from the central archetype of organomineral soil (“king of soils”) - Chernozem, described by V.V. Dokuchaev [

1]. In the Russian soil classification, terrestrial organic soils are distinguished into a separate higher taxonomic unit - trunk, along with postlithogenic, synlithogenic and primary soils [

18]. According to the definition of this classification, they include

“Includes soils whose profile (all or most of it) consists of organic material, usually peat of any botanical composition and degree of decomposition. The trunk includes two divisions: natural peat soils with natural, though somewhat different in properties peat horizons, and drained peat soils and peat bogs (with different agrogenic horizons). Since peat horizons are present in soils of different departments and trunks, it is reasonable to give a scheme of soil profile structure with peat horizons of different thickness and their different ratios with underlying mineral horizons." Here the question arises as to whether the suspended soils of the tropics can be classified strictly as this taxonomic unit, since they do not have a mineral parent material. This may be a formal problem, but not a logical one. Indeed, for terrestrial organomineral soils, the critical thickness depth of the organic soil layer is 50 cm; deeper, the soil already becomes a special type organogenic parent material – pallustium (freshwater swamp sediments) [

31], which, in our opinion, “suspends” peat above the mineral rock.

The given detailed description of the high organogenicity of soils is necessary for understanding the parameters of their water-holding capacity and interpreting hydrologic properties. which we turn to below.

In

Figure 3 shows the dependence lines of key hydrologic properties on the SOC content. The level of hygroscopic moisture is closely related to the carbon content in all studied soils. Except Phu-Quok soils. By the way for this object In general. different dependencies are characteristic compared to other objects. Apparently the nature of the water-holding capacity here is related not so much to the content of organic matter. How many with other parameters – porosity development. etc. presumably - a higher degree of decomposition and humification of organic matter. In Cat-Tien for hygroscopic moisture. there is a correlation between carbon and absorbed moisture. For other indicators – maximum hygroscopic water content (MHW). Field moisture capacity (FMC) and maximum water holding capacity (MWHP). The relationship with carbon content is becoming less clear. This also indicates a transformation of the aggregative state of organic matter and its pore environment. In other cases – Con Dao. Bokor and Bidoup. as the category of soil-hydrological constants increases. the close relationship between carbon content and moisture capacity does not increase. This indicates a low degree of humification transformation of organic matter.

Information on the reliability of differences in the content of organic carbon and the values of hydrologic properties is shown in

Figure 5. It can be seen that there are no statistical differences between the carbon content when comparing objects with each other. The same applies to comparing the levels of hydrological variables with each other. This is due to the significant heterogeneity of the material of the studied samples. On the other hand in a series of samples taken from one object correlation patterns can be traced since there is a gradual dynamics of carbon content within a sample of one trunk. Where differentiation of the degree of decomposition of organic matter of epiphytic soil formations can also occur which was previously confirmed for example by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy methods [

14].

In terms of the nature of the quantity and quality of organic matter and the degree of moisture capacity suspended soils are closest to peats (especially high-moor soils). Impressive abilities to absorb vaporous moisture (ranging from 9.27 to 42%) to field moisture capacity which reaches 1323% (

Table 3) indicate the special ecosystem role of suspended soils. Moreover estimates of the scale of suspended soils can be very large for example in the system of tropical mountain forests they amount to almost 20.000 kg per hectare (20.9 t ha) of mass in primary forests versus only 5 kg per ha (0.006 t ha) in secondary forests which is 4% and 0.004% of the terrestrial forest biomass respectively [

32]. Under dry season conditions the moisture content of epiphytic substrates in the forests of Vietnam is 2.5 times higher than the moisture content of the upper soil horizon [

33] and is close to 80%. This is due to the interception of dripping condensate which settles in the crown at night and practically does not reach the ground [

34]. Which in turn is connected with the well-known paradox of a tropical seasonal forest - despite a week-long absence of rain very high air humidity remains under the canopy (sometimes close to 100%) and during night cooling literally streams of condensate can flow down the trunk which can be intercepted by rosettes of epiphytes and preserved by suspended soils. Large-scale accumulation of suspended soils makes it possible to retain large volumes of water in the crowns. At the whole stand level estimated values of sequestered water in epiphytic material (epiphytes + suspended soils) ranged from 0.81 mm in a tropical montane forest of Costa Rica [

35] to 5 mm in a moss cloud forest in Tanzania [

36]. Mosses also lose stored moisture more quickly: during 3 days without precipitation. maximum water loss was 251% of dry weight for bryophytes and 117% for suspended soils [

37]. In Cat Tien in 2018 at the beginning of the dry season (more than a week without rain) the wet mass of suspended soils of epiphytic “nests” contained 203% of the deposited moisture of moss cushions and 125% and moss “beards” are only 28% [

16]. Our data fully confirm the special ecosystem role of suspended soils in the balance of water supply in the crowns - in Bidoup and Phnom Bokor where mountain moss forests dominate and the genesis of suspended soils is confined to moss cushions the moisture capacity of which is not very high and ranges from 251% to 536% and in seasonal forests (Cat Tien) or shorter and sparse forests (Con Dao) where the buffer and moisture-storing role of suspended soils is much more important reaching 1323% and 1120% but this applies exclusively to suspended soils of ferns. For flowering epiphytes the moisture capacity is much more modest reaching the lowest value in the epiphytic ginger 174%

Hedychium bousigonianum (

Table 3). Analyzing the full data set obtained by our research (

Figure 4) it can also be seen that there is an unexpressed trend for increasing values of hydrologic properties with increasing SOC content. The highest R2 values were found for HM/SOC dependencies - 0.57 and MHW/SOC - 0.33 which may be related to the ability of suspended soils to absorb vaporous moisture from the environment under conditions of high humidity which is characteristic of tropical forests.

The carbon content in suspended soil materials varied widely and was comparable with that of tropical forest litter [

38] and boreal peatlands [

39]. At the same time, tropical suspended soils are characterized by very low nitrogen content, which is reflected in very wide carbon-to-nitrogen ratios. Such a ratio is typical of peats and forest litter [

40] and indicates a very low degree of humification of organic matter [

41]. The values of the O/C and H/C atomic ratios indicate a fairly high degree of oxidation and a low degree of hydrogenation of organic matter.

As a rule, in forest litters of the boreal zone, the calcium content is higher in relation to magnesium [

42]. A decrease in the content of mobile forms of calcium and magnesium in litter may be a consequence of anthropogenic impact [

43]. This may also indicate competition for these non-volatile but important elements for photosynthesis among epiphytes absorbing them from washed-out and suspended soils. Soil pH values belong to the acidic, and more often strongly acidic range. This corresponds well to the low content of mobile forms of calcium and magnesium and corresponds to the oligotrophy of the soils. Soil acidity in this case almost completely depends on the composition of organic matter under conditions of low ash content of the material. High acidity of litter is characteristic, as a rule, of boreal and tropical vegetation [

44] and indicates some similarity in the types of biogenic cycles characteristic of the forest as an eluvial-stable type of vegetation [

45]. The content of mobile forms of phosphorus, potassium and ammonium nitrogen is extremely high in suspended soils. This indicates the accumulative and trophic role of suspended forest organic matter. Abnormally high potassium content is characteristic of Bidup soils. The high content of nutrients in tropical suspended soils is incomparably high compared to forest soils of other climatic zones [

44] and should be noted as their most important attributive characteristic. Since the biotic cycle is considered as a barrier to the removal of chemicals from the soil [

45], the closure of a significant part of this cycle in suspended soils serves the biogeochemical stabilization of the entire ecosystem of the humid tropical forest. In case of precipitation deficiency, there is no need to conserve nutrients in litter, they still cannot be washed out of the soil then, under the conditions of an eluvial flushing regime, the decisive method of preserving nutrients is their accumulation and stabilization in the composition of organic matter.

There are no uniform international standards for the content of heavy metals in soils. The most stringent requirements for soil quality are related to the concept of maximum permissible concentrations, which are most often close to the Clarke or differ from it by tens (but not hundreds) of times. In soils, the maximum permissible concentration of Cu is 33 mg/kg, Pb- 32 mg/kg, Zn - 55 mg/kg, Ni - 80 mg/kg [

46]. For comparison, in Finland, the MAC analogue for lead is 200-750 mg/kg for different types of soil, in the Netherlands 85-600 mg/kg, in Germany - 200-2000 mg/kg. Thus, the soils we studied, even according to strict Russian standards, are unpolluted by copper and lead (only in one sample approaching the MAC level). These soils are also not polluted by nickel and zinc. Taking into account the high accumulative-sorption capacity of suspended soils, the low content of heavy metals in them indicates the absence of modern aerotechnogenic pollution of all the studied ecosystems. It is logical to compare our soils with the background content of heavy metals in the lithosphere [

46]. So for Zn it is 85 mg / kg, for Cu - 47 mg / kg, for Ni - 58 mg / kg, for Pb - 16 mg / kg. Thus, in this case, the studied soils are not contaminated and we are talking about a certain deficiency of heavy metals in the eluvial ecosystem of the tropical rain forest. The mobility of all the specified heavy metals in tropical soils is indicated in the work [

47], it is also indicated there that these metals are characterized by increased bioavailability, and mineral soils poorly retain heavy metals due to the acidic reaction of the environment and the deficiency of clay minerals. Zinc and copper deficiency is known for tropical swamp terrestrial soils [

48] and since this deficiency concerns classical soils, it is difficult to expect elevated concentrations of these elements in suspended soils.

The most amazing thing about the phenomenon of suspended soils is their very existence. It is completely unclear why almost pure organic substrates exist for long periods of time in the warm and very humid atmosphere of the tropics under completely aerobic conditions in which peats (after losing the anaerobicity of bog conditions) very quickly decompose. Suspended soils possess unique microbial assemblages [

49,

50] and have high levels of fungal biomass per unit of organic matter compared to forest floor soils [

51]. Thus at first glance they should be destroyed and washed out faster than they accumulate. Perhaps just as with epiphytes. we should consider them not from a dynamic (successional) point of view as with a sequential change of species or processes. but with “accumulation” because phorophytes seem to accumulate epiphytes throughout their lives [

52,

53,

54] and they in turn are suspended soils. Really Werner et al. [

55] shows that the proportion of epiphytic biomass represented by vascular epiphytes and suspended soils correlates with branch thickness. Recent large-scale studies by Murray et al. [

15] also emphasize the importance of tree size and precipitation levels in determining the quantity and quality of organic matter in suspended soil canopies. Quite rightly they draw attention to the fact that the organic matter of suspended soils (POM) is dominated by O-alkyl C and alkyl C [

56,

57]. O-alkyl C (45–110 ppm) is formed from cellulose. hemicellulose and/or proteins from plant litter or microbial products and alkyl C (10–45 ppm) is commonly found in microbial and plant lipids [

58,

59,

60]. O-alkyl C is often the first carbon group to decrease in abundance upon degradation and is therefore considered labile or “preferred” by degrading microorganisms [

58,

61,

62]. The predominance of O-alkyl C suggests that soil solid organic matter is particularly vulnerable to stress, which can accelerate the decomposition of organic matter. Thus we can talk about potential vulnerability and possibly quite narrow ecological ranges in which suspended soils can exist which as we noted earlier [

50] are most likely an analogue of litter. absent from lowland tropical forests. Together with their high moisture capacity they turn into a kind of edificatory function of epiphytes which seriously shape the microclimate and habitat in the crowns for thousands of species of microorganisms, fungi, microarthropods, worms, insects and in frequent cases vertebrates.

And finally, the study of the parameters of the isotopic signatures showed that the isotopic composition of carbon in suspended soils differed significantly from terrestrial soils and phorophytes, but did not differ from accumulative epiphytes and close to them ecobiomorphs, this suggests that the carbon cycle of suspended soils is largely separated from trees host and formed by the epiphytes themselves and their consorts. The isotopic composition of nitrogen did not differ significantly from terrestrial plants and differed significantly from typical epiphytes. But the greatest difference in δ

15N in suspended soils from terrestrial soils, and the signature of the latter is the only one giving positive values of δ

15N (Fig. 7). This gives us a clear and reliable tool for distinguishing suspended soils from formed peats, for example, in analytical studies, because visually they are very similar. The older and deeper the peats are, the more positive the δ

15N value is; deeper than 50 cm (and older than 100 years), the nitrogen signature value becomes greater than 0 and is indistinguishable from the signature of terrestrial soils, which are always positive [

63,

64].

Figure 1.

Map of the study region. Sample sites are marked with red circles.

Figure 1.

Map of the study region. Sample sites are marked with red circles.

Figure 2.

Some epiphytic communities and epiphytes from which suspended soils were collected: (a) Lyonia ovalifolia tree in Bidup Nui Ba from which suspended soils were collected from heights up to 2 m, mainly under mosses and ferns; 2–4 m. moss cushions with ferns and small orchids underplanted; 4–6 m, mainly large orchids and heather and 6–8 m, mainly small orchids and lichens on individual thin branches; (b) ferns Hymenophyllum cushion in Phnom Bokor moss forest; (с) moss cushions with suspended soils form in the mountain forest of Bidup Nui Ba; (d) ferns epiphyte Drynaria quercifolia in lowland forest (Cat Tien park); (e) ferns epiphyte Microsorum punсtatum in lowland forest (Cat Tien park); (f) ferns epiphyte Platycerium coronans in lowland forest (Cat Tien); (g) ginger epiphyte Hedychium bousigonianum in lowland forest (Cat Tien) and (h) orchid epiphyte Cymbidium finlaysonianum in a sparse community (Phu Quoc); (i) classical nesting epiphyte ferns Asplenium nidus forms suspended soils in a lowland forest (Cat Tien park).

Figure 2.

Some epiphytic communities and epiphytes from which suspended soils were collected: (a) Lyonia ovalifolia tree in Bidup Nui Ba from which suspended soils were collected from heights up to 2 m, mainly under mosses and ferns; 2–4 m. moss cushions with ferns and small orchids underplanted; 4–6 m, mainly large orchids and heather and 6–8 m, mainly small orchids and lichens on individual thin branches; (b) ferns Hymenophyllum cushion in Phnom Bokor moss forest; (с) moss cushions with suspended soils form in the mountain forest of Bidup Nui Ba; (d) ferns epiphyte Drynaria quercifolia in lowland forest (Cat Tien park); (e) ferns epiphyte Microsorum punсtatum in lowland forest (Cat Tien park); (f) ferns epiphyte Platycerium coronans in lowland forest (Cat Tien); (g) ginger epiphyte Hedychium bousigonianum in lowland forest (Cat Tien) and (h) orchid epiphyte Cymbidium finlaysonianum in a sparse community (Phu Quoc); (i) classical nesting epiphyte ferns Asplenium nidus forms suspended soils in a lowland forest (Cat Tien park).

Figure 3.

Relationship of soil-hydrological constants and total soil organic matter content. Both – in gravimetric percent’s (% to dry grounded fine earth).

Figure 3.

Relationship of soil-hydrological constants and total soil organic matter content. Both – in gravimetric percent’s (% to dry grounded fine earth).

Figure 4.

Relationship (linear regression) of hydrologic properties with SOC content for the whole data set.

Figure 4.

Relationship (linear regression) of hydrologic properties with SOC content for the whole data set.

Figure 5.

One-way ANOVA multiple comparisons results between different sampling sites for hydrologic properties and SOC content (above the lines is the following p-value).

Figure 5.

One-way ANOVA multiple comparisons results between different sampling sites for hydrologic properties and SOC content (above the lines is the following p-value).

Figure 6.

Ordination diagram of suspended soil samples based on the results of principal component analysis (A, C – PC1 and PC2; B, D – PC1 and PC3). PC1, PC2, PC3 – principal components. A, C – suspended soil samples. Sample groups: 1 – orchids, 2 – ferns, 3 – mosses, 4 – Vaccinium sp., 5 – Bidup tiers. Polygons connect the extreme points for habitats (the centroids are labeled on the diagram). B, D – soil features.

Figure 6.

Ordination diagram of suspended soil samples based on the results of principal component analysis (A, C – PC1 and PC2; B, D – PC1 and PC3). PC1, PC2, PC3 – principal components. A, C – suspended soil samples. Sample groups: 1 – orchids, 2 – ferns, 3 – mosses, 4 – Vaccinium sp., 5 – Bidup tiers. Polygons connect the extreme points for habitats (the centroids are labeled on the diagram). B, D – soil features.

Figure 7.

δ15N and δ13C values in different types of substrates (mean and standard error of the mean). Identical letters indicate objects that are not significantly different from each other based on the results of pairwise permutation tests.

Figure 7.

δ15N and δ13C values in different types of substrates (mean and standard error of the mean). Identical letters indicate objects that are not significantly different from each other based on the results of pairwise permutation tests.

Table 1.

Edaphic and climatic conditions of the habitats studied.

Table 1.

Edaphic and climatic conditions of the habitats studied.

| Location |

Phu Quoc |

Con Dao |

Cat Tien |

Bidoup |

Phnom Bokor |

| Mean annual precipitation |

2880 mm |

2070 mm |

2470 mm |

1860 mm*

|

2780 mm |

| Dry season |

January – February |

December – April |

November – April |

Not pronounced |

January – February |

| Mean annual temperature |

27.1°C |

27.1°C |

26.2°C |

18.2°C |

22.5°C |

| Soil |

Folic Arenosol, Stagnic |

Folic Arenosol, |

Dystric Skeletic Rhodic Cambisols and Skeletic Greyzemic Umbrisols |

Loamic Folic Ferralsols |

Folic Arenosol, Stagnic |

Table 2.

Results of ordination using the principal component method. PC1, PC2, PC3 – the first three principal components.

Table 2.

Results of ordination using the principal component method. PC1, PC2, PC3 – the first three principal components.

| |

PC1 |

PC2 |

PC3 |

| Eigenvalue |

6.35 |

4.17 |

2.70 |

| Proportion explained |

0.289 |

0.189 |

0.123 |

| Cumulative proportion |

0.289 |

0.478 |

0.601 |

Table 3.

The value of the measured hydrologic properties of the studied suspended soils. Collection points are ranked by increasing altitude above sea level from top to bottom, with these altitudes indicated. Epiphytes from which suspended soils were collected are marked * moss cushions, ** ferns, *** flowering plants, **** the samples was taken along the entire length of one tree from bottom to top; the epiphytic community consisted of many mosses, small ferns and orchids. Ca Ex.f. and Mg Ex.f. - Exchangeable form of Ca and Mg; HM - hygroscopic water content; MHW - maximum hygroscopic water content; MWHP - maximum water holding capacity; FMC - field moisture capacity.

Table 3.

The value of the measured hydrologic properties of the studied suspended soils. Collection points are ranked by increasing altitude above sea level from top to bottom, with these altitudes indicated. Epiphytes from which suspended soils were collected are marked * moss cushions, ** ferns, *** flowering plants, **** the samples was taken along the entire length of one tree from bottom to top; the epiphytic community consisted of many mosses, small ferns and orchids. Ca Ex.f. and Mg Ex.f. - Exchangeable form of Ca and Mg; HM - hygroscopic water content; MHW - maximum hygroscopic water content; MWHP - maximum water holding capacity; FMC - field moisture capacity.

| Habitat: national park |

Samples |

Species of epiphyte |

Ca Ex.f., mol/

100g |

Mg Ex.f., mol/

100g |

рН |

P2O5, mg/

kg |

K2O, mg/

kg |

N-NH4, mg/

kg |

N-NO3, mg/kg |

Cu, mg/

kg |

Pb, mg/kg |

Zn, mg/kg |

Ni,

mg/kg |

Сd,

mg/kg |

δ13C |

δ15N |

C,% |

H,% |

N % |

O % |

С/N |

O/C |

H/C |

HM |

MHW |

FMC |

MWHP |

Phu Quoc

(Vietnam)

≈ 0-1.5 m asl |

3/7 |

Asplenium nidus** |

6.25 |

50.0 |

3.0 |

490 |

470 |

266 |

13.2 |

14.2 |

30.9 |

6.07 |

9.51 |

0.21 |

-31.1 |

0.28 |

46.9 |

5.33 |

1.94 |

45.9 |

24.2 |

0.98 |

0.11 |

11.9 |

35.7 |

969 |

593 |

| 2/7 |

Cymbidium finlaysonianum*** |

11.2 |

10.0 |

3.6 |

473 |

4365 |

268 |

1.39 |

1.62 |

7.65 |

23.6 |

4.19 |

<0.005 |

-27.5 |

-2.43 |

46.2 |

5.55 |

1.37 |

46.9 |

33.8 |

1.02 |

0.12 |

7.59 |

19.4 |

477 |

318 |

| 3/10 |

Drynaria quercifolia** |

6.25 |

31.2 |

3.5 |

190 |

600 |

174 |

15.1 |

5.4 |

8.1 |

4.32 |

8.27 |

0.10 |

-29.2 |

2.23 |

50.5 |

5.28 |

1.39 |

42.9 |

36.4 |

0.85 |

0.10 |

10.6 |

24.0 |

519 |

290 |

| 3/8 |

Microsorum punсatum** |

6.25 |

17.5 |

3.2 |

400 |

2210 |

197 |

8.02 |

9.54 |

14.2 |

3.27 |

3.83 |

0.30 |

-29.7 |

-2.14 |

49.4 |

5.48 |

1.97 |

43.2 |

25.0 |

0.87 |

0.11 |

9.48 |

42.9 |

871 |

447 |

| 3/14 |

Platycerium coronans** |

7.50 |

26.2 |

3.5 |

480 |

510 |

267 |

113.2 |

9.8 |

16.9 |

3.08 |

8.38 |

0.16 |

-29.5 |

-3.60 |

50.2 |

5.08 |

1.40 |

43.4 |

36.0 |

0.87 |

0.10 |

10.3 |

28.3 |

262 |

135 |

Con Dao

(Vietnam)

≈ 20 m asl |

3/11 |

Davallia sp.** |

15.0 |

<0.20 |

4.5 |

230 |

540 |

190 |

9.43 |

13.4 |

10.9 |

2.74 |

8.29 |

0.14 |

-30.6 |

2.15 |

48.6 |

5.11 |

1.55 |

44.8 |

31.4 |

0.92 |

0.11 |

11.0 |

30.1 |

387 |

191 |

| 3/2 |

Davallia sp.** |

62.5 |

15.0 |

3.0 |

150 |

230 |

77 |

10.8 |

2.55 |

6.08 |

0.61 |

2.20 |

0.05 |

-29.5 |

-3.60 |

29.8 |

3.10 |

0.74 |

66.4 |

41.3 |

2.34 |

0.10 |

3.77 |

9.27 |

315 |

198 |

| 3/6 |

Drynaria bonii** |

7.50 |

<0.20 |

2.8 |

360 |

680 |

493 |

19.3 |

7.53 |

7.56 |

4.54 |

2.94 |

0.14 |

-27.9 |

0.93 |

48.0 |

5.06 |

1.47 |

45.5 |

32.8 |

0.95 |

0.11 |

11.1 |

29.8 |

1120 |

681 |

| 3/1 |

Drynaria bonii** |

35.0 |

32.5 |

3.0 |

260 |

270 |

96 |

10.8 |

5.56 |

10.10 |

0.38 |

3.11 |

0.04 |

-28.9 |

-2.49 |

37.5 |

3.96 |

0.98 |

57.6 |

38.5 |

1.78 |

0.10 |

5.87 |

17.8 |

366 |

139 |

Cat Tien

(Vietnam)

≈ 120 m asl |

2/2 |

Asplenium nidus** |

37.5 |

<0.20 |

3.9 |

309 |

1756 |

215 |

7.88 |

17.6 |

6.0 |

89.0 |

31.7 |

<0.005 |

-30.0 |

0.27 |

43.2 |

4.74 |

1.76 |

50.3 |

24.5 |

1.16 |

0.11 |

11.1 |

29.8 |

1323 |

327 |

| 2/4 |

Drynaria quercifolia** |

16.2 |

6.3 |

4.8 |

288 |

1091 |

190 |

4.17 |

10.6 |

3.0 |

41.8 |

4.05 |

<0.005 |

-29.3 |

-0.14 |

47.6 |

4.87 |

1.38 |

46.2 |

34.4 |

0.97 |

0.10 |

13.6 |

35.4 |

275 |

152 |

| 2/6 |

Hedychium bousigonianum*** |

12.5 |

38.8 |

3.6 |

691 |

4555 |

168 |

19.0 |

24.0 |

11.5 |

61.0 |

54.2 |

0.04 |

-29.5 |

-2.08 |

37.0 |

4.80 |

1.53 |

56.7 |

24.2 |

1.53 |

0.13 |

5.9 |

16.3 |

174 |

69 |

| 3/12 |

Microsorum punсtatum** |

10.0 |

<0.20 |

2.8 |

260 |

570 |

268 |

6.13 |

16.70 |

7.74 |

2.57 |

5.42 |

0.17 |

-23.1 |

-3.30 |

49.9 |

5.21 |

1.84 |

43.1 |

27.1 |

0.86 |

0.10 |

10.9 |

24.4 |

409 |

186 |

| 3/13 |

Remusatia vivipara + ep.orchids*** |

6.25 |

25.0 |

3.0 |

300 |

1130 |

226 |

9.90 |

10.70 |

8.71 |

5.41 |

5.62 |

0.12 |

-30.6 |

2.15 |

47.1 |

5.24 |

1.83 |

45.9 |

25.7 |

0.97 |

0.11 |

11.4 |

30.7 |

358 |

202 |

Phnom Bokor (Cambodia)

≈ 1000-1050 m asl |

3/4 |

Aglaomorpha sp.** |

11.2 |

27.5 |

5.0 |

210 |

690 |

116 |

8.96 |

3.94 |

7.29 |

1.76 |

4.89 |

0.07 |

-27.9 |

-2.11 |

37.5 |

4.26 |

0.92 |

57.4 |

40.9 |

1.53 |

0.11 |

8.96 |

25.6 |

332 |

48 |

| 3/3 |

Aglaomorpha sp.** |

47.5 |

<0.20 |

4.0 |

200 |

570 |

129 |

9.43 |

2.46 |

4.65 |

1.73 |

4.81 |

0.05 |

-30.9 |

-4.18 |

39.5 |

4.38 |

0.92 |

55.2 |

43.0 |

1.40 |

0.11 |

9.51 |

26.0 |

527 |

294 |

| 3/5 |

Hymenophyllum sp.** |

33.8 |

40.0 |

2.5 |

160 |

440 |

118 |

7.07 |

1.55 |

6.97 |

1.58 |

6.72 |

0.08 |

-29.9 |

0.33 |

33.9 |

4.03 |

0.41 |

61.7 |

82.6 |

1.86 |

0.12 |

6.78 |

23.3 |

264 |

149 |

| 3/9 |

Moss cushions *

|

7.50 |

18.8 |

2.8 |

390 |

1230 |

312 |

6.13 |

2.05 |

5.56 |

1.94 |

9.09 |

0.15 |

-30.9 |

-4.18 |

49.5 |

6.03 |

0.62 |

43.9 |

79.7 |

0.89 |

0.12 |

9.24 |

29.2 |

671 |

385 |

Bidoup

(Vietnam)

≈ 1500-2000 m asl |

1/1 |

1 tier 2m**** |

35.0 |

52.5 |

3.0 |

267 |

1993 |

134 |

2.32 |

3.68 |

1.59 |

14.6 |

3.25 |

0.02 |

-26.9 |

-2.74 |

51.0 |

5.64 |

0.87 |

42.5 |

58.9 |

0.83 |

0.11 |

10.7 |

26.4 |

406 |

222 |

| 1/2 |

2 tier 4m**** |

31.2 |

<0.20 |

3.5 |

288 |

3274 |

130 |

3.71 |

5.15 |

2.16 |

23.2 |

4.70 |

0.11 |

-26.8 |

-2.40 |

49.7 |

6.00 |

0.98 |

43.3 |

50.6 |

0.87 |

0.12 |

10.2 |

16.5 |

536 |

320 |

| 1/3 |

3 tier 6 m**** |

18.8 |

25.0 |

3.2 |

272 |

4081 |

111 |

2.78 |

6.26 |

1.87 |

14.7 |

4.74 |

<0.005 |

-27.6 |

-2.97 |

48.0 |

5.67 |

0.51 |

45.9 |

94.1 |

0.96 |

0.12 |

10.5 |

30.0 |

364 |

88 |

| 1/4 |

4 tier 6-8 m**** |

43.8 |

56.2 |

2.8 |

284 |

3701 |

174 |

0.93 |

4.80 |

2.45 |

12.8 |

4.16 |

<0.005 |

-27.3 |

-2.63 |

50.6 |

5.44 |

0.59 |

43.4 |

86.2 |

0.86 |

0.11 |

9.93 |

24.4 |

366 |

230 |

| 2/3 |

Aglaomorpha sp.** |

37.5 |

18.8 |

3.0 |

333 |

1091 |

278 |

1.39 |

5.10 |

4.94 |

26.9 |

7.65 |

<0.005 |

-28.9 |

-0.38 |

34.1 |

3.96 |

1.53 |

60.4 |

22.3 |

1.77 |

0.12 |

7.74 |

19.9 |

251 |

155 |

| 2/5 |

Vaccinium sp.*** |

58.8 |

65.0 |

3.4 |

420 |

4650 |

150 |

2.78 |

5.54 |

7.92 |

21.6 |

0.97 |

0.02 |

-27.2 |

-0.99 |

51.8 |

5.51 |

0.85 |

41.9 |

61.6 |

0.81 |

0.11 |

10.5 |

29.2 |

299 |

196 |

| 2/1 |

Moss cushions * |

22.5 |

<0.20 |

3.1 |

300 |

2088 |

170 |

3.24 |

3.27 |

3.08 |

23.3 |

2.49 |

0.02 |

-26.8 |

-3.70 |

48.0 |

5.72 |

0.72 |

45.6 |

67.7 |

0.95 |

0.12 |

10.1 |

32.1 |

483 |

190 |