1. Introduction

Mangrove forests are complex ecological assemblages composed of trees and shrubs adapted to grow in intertidal environments along tropical and subtropical coasts. Despite the wide consensus about their economic and societal value, more than 50% of the world’s mangroves have already been destroyed [

1,

2]. A considerable portion of the ecosystem services attributed to mangrove forests are closely linked with soil properties and composition

, such as their ability to act as CO2 sinks or to regulate coastal water composition and quality [

3,

4].

Intertidal soils often show water saturation, high organic matter contents, fine texture, near-neutral pH, and redox conditions varying from suboxic to anoxic [6-8]. However, small variations in topography and in hydrological conditions lead to a complex spatial variability in terms of the composition and properties of soils and sediments in these environments [

9,

10]. Additionally, these properties and composition show significant seasonal changes in these environments, sometimes affecting soil and water quality, since these changes can increase the bioavailability of potentially toxic elements and substances [

11,

12].

Mangroves in Brazil occur along a coastline over 7,000 km long, from the equatorial Amazon coast to the southern coast, showing variable forest patterns due to climatic and geologic variations [10, 13]. Among the different Brazilian states, the state of Bahía has the longest coastline (932 km, coastal extension) and the second largest bay in the country, Baía de Todos os Santos, 178 km2 of whose area are occupied by mangrove forests [

14,

15].

Many studies have been carried out on the BTS, aiming to understand the ecological aspects [

16,

17], and pollution [

18,

19]. However, the number of studies has examined spatial variations in soil components, properties, and quality is smaller [

20], and, as far as we are aware, no studies have addressed the spatiotemporal variability of mangrove soils in the BTS and very few have looked at this aspect in the whole of Brazil. In this sense, this work aims to contribute to a better understanding of the spatiotemporal heterogeneity typical of intertidal environments. To this end, samples were seasonally collected at four sites that were representative of different coastal environments to analyze soil parameters and components, including texture, water, pH, Eh, total organic carbon, total nitrogen, C/N ratio, δ

13C, and δ

15N, as well as total Fe and its geochemical fractions.

2. Materials and Methods

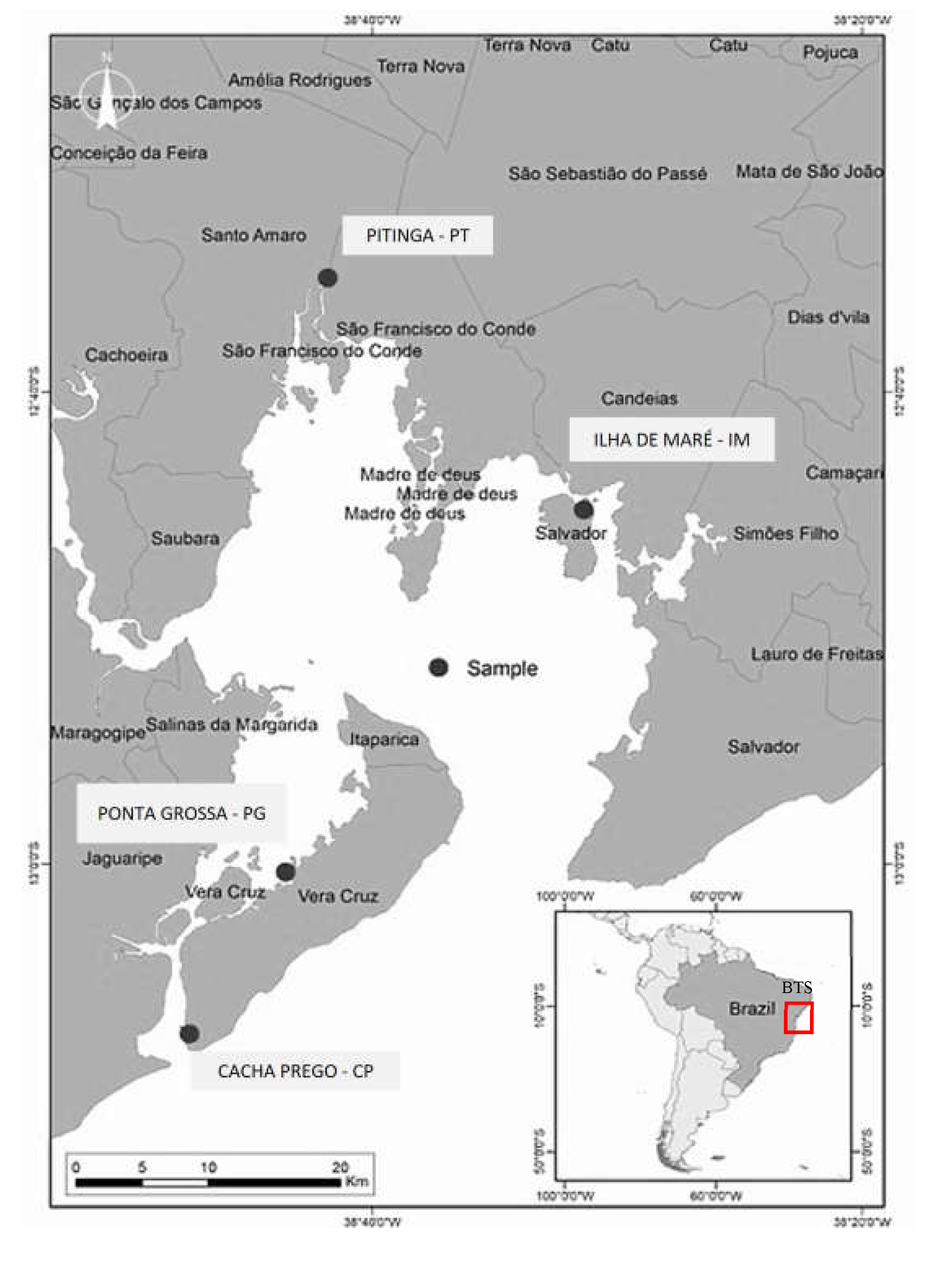

The study was performed in Baía de Todos os Santos, characterized by a tropical-humid climate with a mean annual temperature of 25.2 °C and a mean rainfall of 1900 mm/year. There is a dry season during the months of January to March (<150 mm/month), when maximum temperatures reach 30 ºC and mean values are around 27 ºC, while during the rainy season (April, May, and June), mean temperatures are around 24 ºC and rainfall exceeds 300 mm/month [

21,

22]. A total number of four mangrove forest sites were selected in Baía de Todos os Santos (BTS,

Figure 1): two of them located at the entrance of the bay (Cacha Prego, CP, and Ponta Grossa, PG), in areas with a low degree of anthropic impact; another one located in the northeastern region (Ilha de Maré, IM), close to industrial areas and maritime ports, and another one in the northern region (Pitinga, PT), an area with a history of metal pollution associated with past metallurgical activity [

16].

The selected sites showed different hydrodynamic conditions, with the IM site located in the middle of the BTS, in a more sheltered area with a lower degree of exposure to hydraulic energy. Mangrove sites CP and PG, located in Itaparica Island, were subjected to a higher influence of marine currents due to the higher speed of tidal currents at the entrance of Baía de Todos os Santos [

23]. Finally, mangrove site PT, despite being located at the northern end of the BTS, far away from the Atlantic Ocean, is included within an estuarine area subjected to the influence of the Subaé River [

23].

Mangroves in sites IM and CP were composed of single-species Rhizophora mangle (L.) forests, while PT and PG showed mixed forests composed of R. mangle and Laguncularia racemosa (L.). These sites were selected in order to cover different sections of the BTS to analyze potential spatial variations due to the composition of the different forest compositions and hydrodynamic characteristics of each site.

Soil and mangrove leaf samples were collected at low tide during the dry season (DS), between December 2020 and February 2021, and during the rainy season (WS), in the months of June and July 2021. For each site and season, 12 samples were collected from the soil surface layer (0–5 cm) and from the deep layer (15-30 cm); each sample was in turn composed of three subsamples, collected using stainless steel corers. Additionally, twelve leaf samples were collected at each site; considering the representative species within each forest site, samples collected at CP and IM consisted of R. mangle leaves, while those collected at PG and PT consisted of R. mangle and L. racemosa leaves. Each composite sample consisted of 12 leaves from three different individual trees for each species.

Soil samples were characterized in terms of pH and Eh using a HI8424 portable pH-meter (Hanna Instruments). The pH electrode was previously calibrated using pH 4 and pH 7 standards, while the Eh-meter was tested using a 220 mV standard redox solution. Granulometry was determined by sifting through a 2 mm sieve to obtain the fine earth fraction, then through a 0.05 mm sieve to separate the fine sand from the fine fraction (silt and clay particles). To calculate water content, 5 g of each wet soil sample were dried in an oven at 60 °C for 48 h.

Total organic carbon (TOC%), total nitrogen (TN%), and carbon (δ13C) an nitrogen (δ15N) isotope ratios were determined in soil and plant samples on an elemental analyzer (FlashEA1112, ThermoFinnigan). All soil samples had been previously subjected to acid attack using 10 ml HCl (1N) to remove carbonates. After adding the acid solution, samples were shaken for 1 h, then centrifuged to remove HCl, washed five times in deionized water, and dried in an oven at 40 °C. Leaf samples were washed in distilled water several times to remove all adhered material. All the analyses were performed by the Research Support Services (Servizos de Apoio á Investigación, SAI) of the University of A Coruña.

Fe content was determined on 0.5 g of ground sample, digested using 9 ml nitric acid (HNO

3 65%) and 3 ml ultrapure hydrochloric acid (HCl 37.5%) in a closed-system microwave digestor (Milestone; ETHOS EASY); determination was done on an atomic absorption spectrometer (Perkin Elmer). The analytical method used was validated using certified reference material for soil (SO-3, Canadian Certified Reference Material Project, Canada), with an iron recovery rate over 87%. Sequential extraction of metallic phases was performed using the BCR method [

24] and the sequence proposed by [

25], as described below:

- F1, soluble fraction, exchangeable and associated with carbonates (ExCa): 30 ml acetic acid (0.11 mol L-1; pH = 4.5) were added to each sample (2 g wet sample); samples were then shaken at 25 °C for 16 h. After shaking, samples were centrifuged to remove the supernatant (fraction 1), washed in ultrapure deoxygenated water with bubbling N2 for 10 min and then centrifuged again, a procedure that was repeated before each subsequent stage;

- F2, fraction associated with amorphous iron oxides (Am): to the residue of the previous fraction, 20 ml of solution containing 20 g ascorbic acid + 50 g sodium citrate + 50 g bicarbonate + 1 L ultrapure deoxygenated H2O and N2 at pH 8 were added. Samples with the solution were shaken at 25 °C for 24 hours and were subsequently centrifuged to collect the washed extract;

- F3, fraction associated with crystalline iron oxyhydroxides (Cri): each sample was added 20 ml of solution containing 73.925 g sodium citrate + 9.24 g NaHCO3 in 1 L ultrapure H2O and 3 g sodium dithionite, then shaken for 30 min at 75 °C and then centrifuged to collect the washed extract;

- F4, reduced forms associated with organic matter and oxidizable sulfides (Red): each sample was added 10 ml H2O2 (8.8 M) and warmed in a bath at 85 °C until evaporation down to 3 ml, followed by a second addition of 10 ml H2O2. Samples were kept warm (in a bath at 85 °C) until evaporation down to 1 ml, at which point 50 ml of AcNH4 solution were added and samples were shaken for 16 h at 25 °C.

The residual fraction (FR) value was calculated from the difference between the total concentration after microwave digestion and the sum of bioavailable fractions (∑ F1 → F4). Contents in each fraction were analyzed by atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS).

To extract pyrite, 10 g of wet soil sample from each site were freeze-dried for 48 hours and then gently disaggregated using an agate mortar [

26]. Pyrites were separated by density inside a fume hood using bromoform (ρ=2.89 g cm

-3) and subsequently washed in acetone and analyzed under a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Ultra-Plus, Zeiss, Germany).

The results were analyzed using descriptive statistics (Sigmaplot 12.0), and a Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test was applied at a p<0.05 level of significance (XLSTAT 2014) to compare the results obtained from the different study sites. This non-parametric test was selected due to its higher robustness and lower statistical assumption requirements [

27].

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical characterization of soils

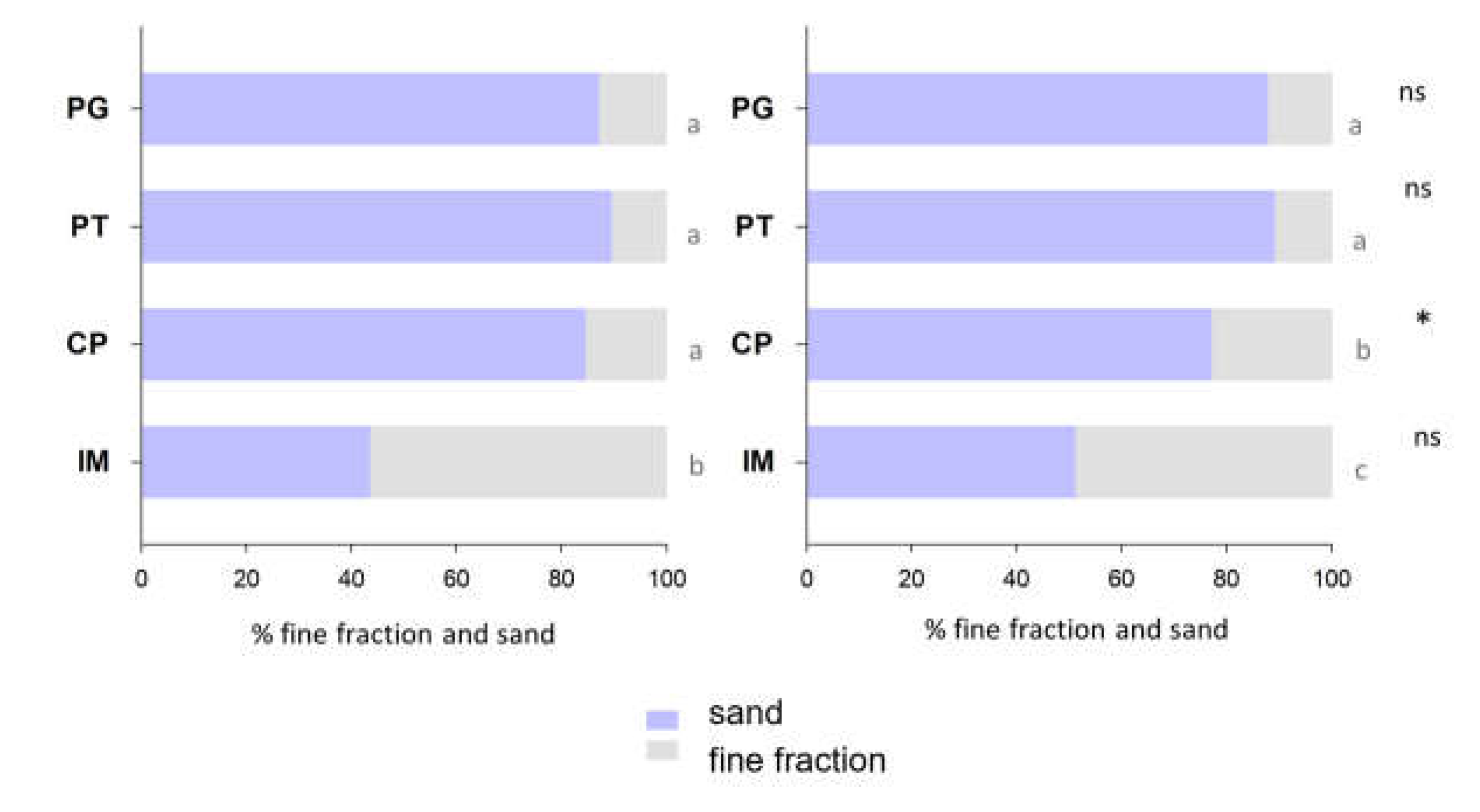

Sand contents ranged from 43.7% to 89.8%, with soils from IM (silt+clay: 52.4±8.6%;

Figure 2) showing a significantly finer texture than the remaining sites both in the surface and deep layers (). Site CP (fine fraction: 22.6±3.1%) showed a significantly finer texture in the deep layer than the remaining two sites: PT (11.9±3.6%) and PG (10.6±2.4%).

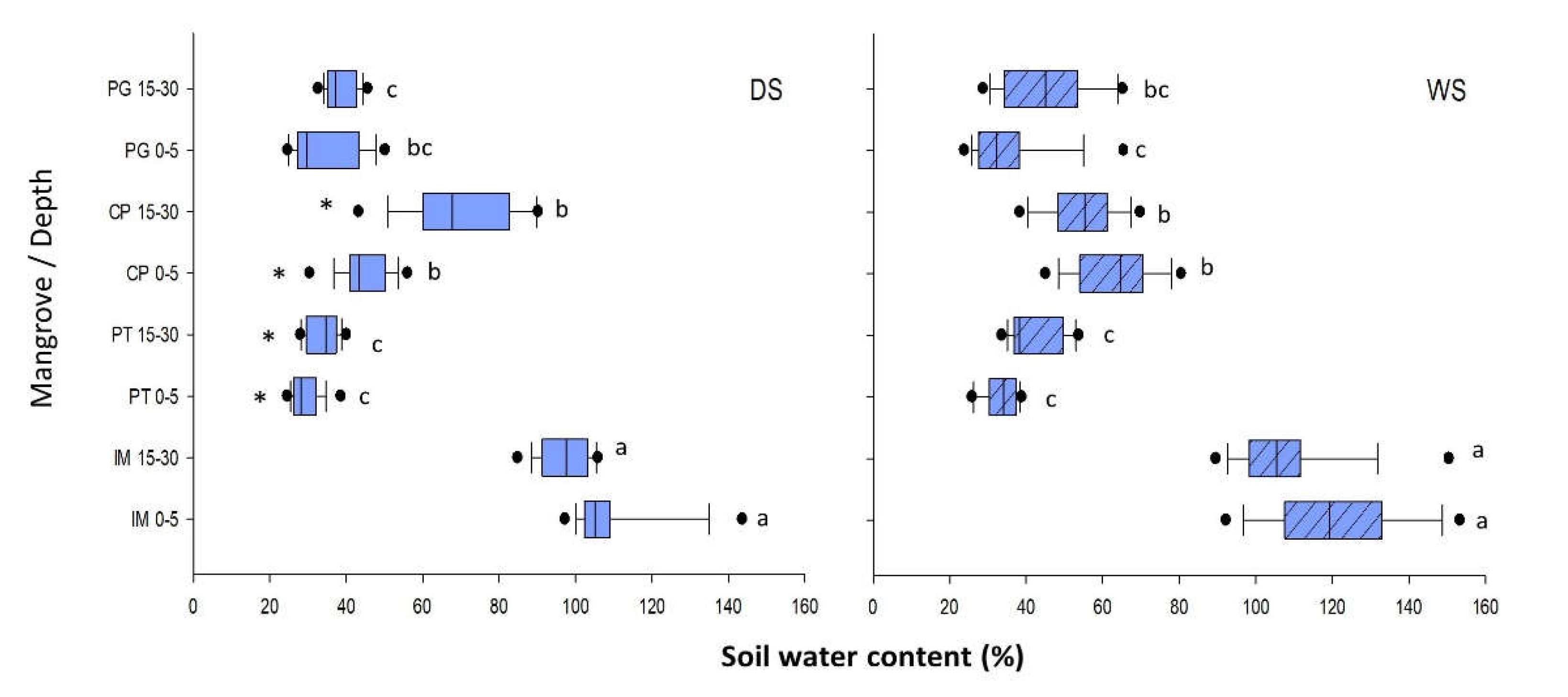

Water content varied between 24% and 153%, with significantly higher values in IM (85-153%, mean: 109±16%) than in the remaining sites during both the dry and

the rainy seasons (

Figure 3). No common patterns related to depth or seasonality were observed for water content.

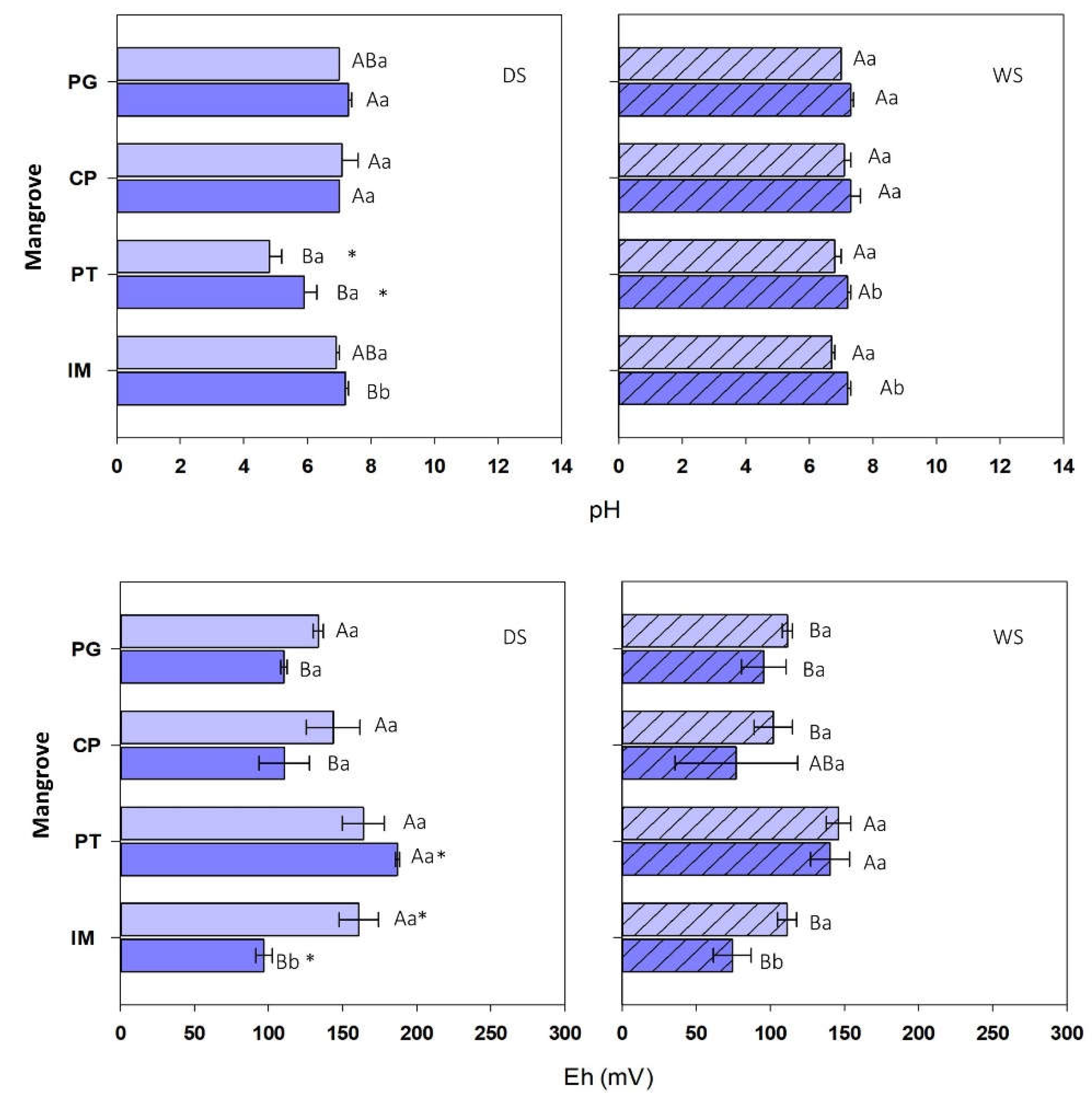

During the dry season (DS), pH varied between 4.5 and 7.4 (

Figure 4), with PT soils ranging from highly to moderately acidic (range: 4.5-6.2), while values in the remaining areas were near neutral, ranging between 6.9 and 7.4. In the rainy season (WS), pH varied between 6.6 and 7.7, with mean values approaching neutrality in all sites (

Figure 4). Variations according to depth were observed during the rainy season in the PT mangrove and in the two seasons in IM, with the lowest pH values found in the surface soil layer. As for seasonality, only PT showed significant differences, with more acidic values in the dry than in the rainy season.

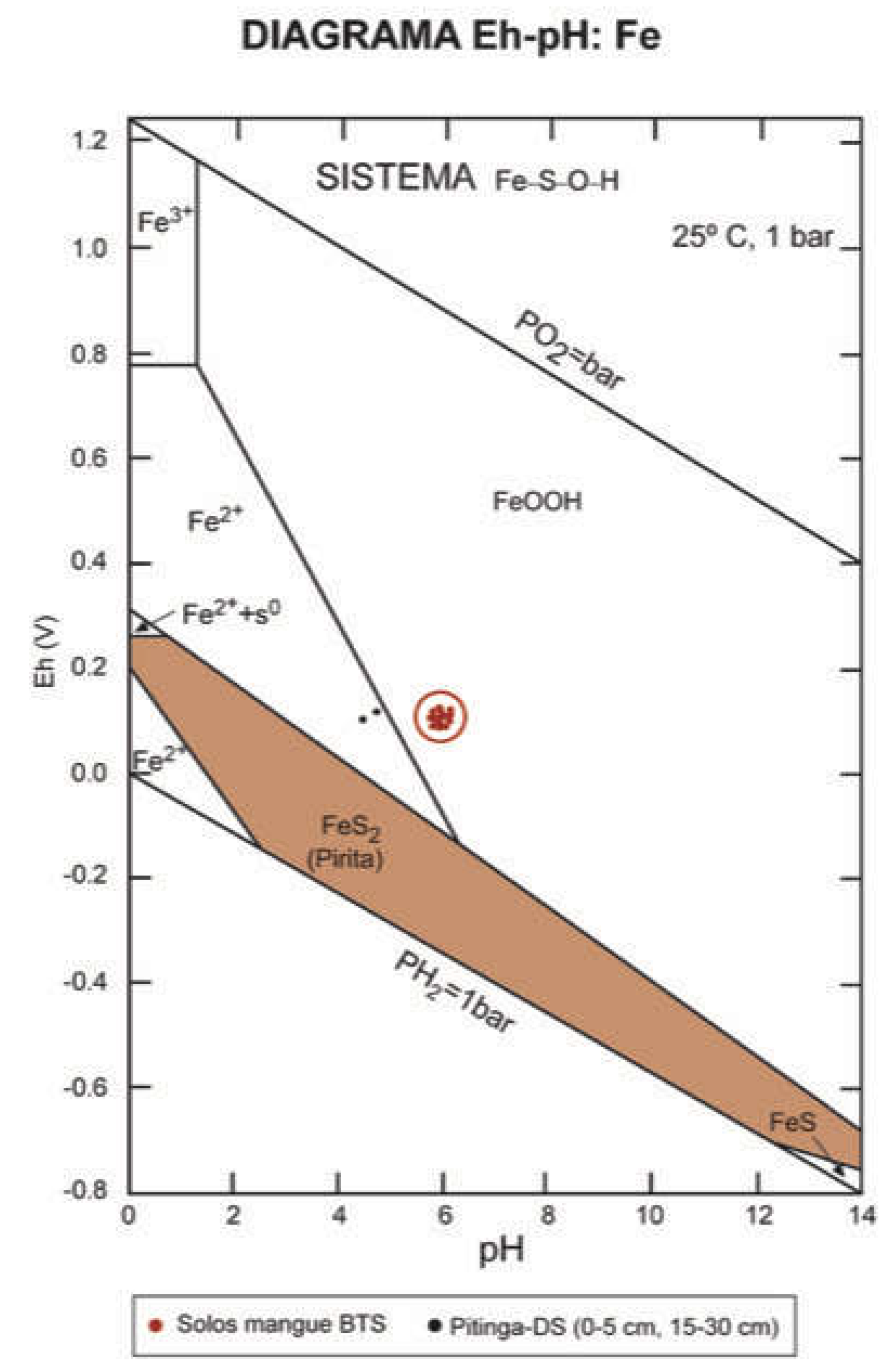

Eh during the rainy season ranged from +92 mV to +188 mV (

Figure 4), with mean values typical of suboxic soils in all the mangroves (generally Eh<300 mV) [

8] except for IM, where conditions in the deep soil layer were predominantly anoxic (+93±6 mV). Eh values during the rainy season were generally lower than those observed during the dry season (range: 30 to 155 mV), mainly corresponding to suboxic conditions in the surface layer and anoxic conditions in the deep layer in IM, PG, and CP (IM: 93±27 mV; PG: 96±15 mV; CP: 90±31 mV). Seasonal differences were observed in the surface and deep soil layers in IM, while for PT, they were only observed in the deep layer. Vertical variations were only observed in IM, with the highest values found in surface soils for both seasons. Eh showed significant spatial differences, with the highest values in the PT mangrove in both seasons.

3.2. Soil composition: total organic carbon (TOC), total nitrogen (TN), C/N ratio, and isotopic ratios

Value ranges for TOC and TN were 0.75-6.59% and 0.03-0.35%, respectively, with the highest contents in IM soils; these parameters showed a strong positive correlation (r=0.84; p<0.001) (

Table 1). No seasonal differences or variations according to depth were observed, except in the case of IM during the dry season, where the highest contents were found in surface soils (TOC: 6.01±0.58%; TN: 0.32±0.03%). C/N ratio varied between 17.3 and 31.6, with no seasonal or spatial differences. Differences according to depth were only observed in IM during the dry season, with higher values in the deep layer.

Values for δ13C ranged from -28.4‰ to -25.6‰, with no seasonal differences but with significant spatial variations for the two periods. Contents in PT during the dry season (15-30 cm depth: -27.40±0.54‰) were significantly lower than in PG (-26.16±0.16‰). During the rainy season, contents in surface soils were also lower in PT than in PG, as well as lower than those observed in the deep soil layer of the remaining sites. Differences between depths were only observed in IM during the rainy period, with the lowest values in the surface soil layer.

The values for δ15N varied between 0.3‰ and 3.8‰, and contents observed in PG during the dry season in the surface soil layer (0-5 cm) and during the rainy season in the deep soil layer (15-30 cm) were significantly lower than those found in the remaining sites. No differences between depths or seasonal variations were found.

3.3. Leaf composition: total C, TN, C/N, δ13C, and δ15N

C and N contents in plants ranged from 36.7% to 42.5% and from 0.7% to 1.4% (

Table 2), respectively, with no spatial variation but showing significant differences between species in PT, with

Rhizophora mangle leaves (total C: 41.5±0.5%; total N: 1.3±0.2%) showing significantly higher values than

Laguncularia racemosa leaves (total C: 40.5±0.3 %; N total 1.0±0.2%). C/N ratio ranged from 30 to 54 and showed no differences among sites, but it did show variations between species in PT, with significantly higher values for

L. racemosa.

Contents of δ13C and δ15N varied between -30.6‰ and -28.6‰ and between 0.4‰ and 3.3‰, respectively, again with differences between species in the PT mangrove, where δ13C values were higher for R. mangle, while δ15N was higher for L. racemosa.

δ13C content in R. mangle showed spatial variations, with poorer levels in IM and CP, while the opposite pattern was observed for δ15N. As for L. racemosa leaves, differences among sites were only observed for δ15N, values, with contents in PT (2.93±0.32‰) being significantly higher than in PG (1.83±0.12‰).

3.4. Total Fe and geochemical partitioning in soils

Total Fe varied between 0.10% and 2.8% and showed no differences according to soil depth (

Figure 5), but did show significant spatial variations, with the highest values corresponding to IM soils, both during the dry (0-5 cm: 2.3±0.5%; 15-30 cm: 2.6±0.1%) and the rainy season (0-5 cm: 2.3±0.5 %; 15-30 cm: 2.6±0.1%). Contents in CP during the rainy season (0-5 cm: 1.3±0.3%; 15-30 cm: 1.2±0.2%) were also higher than those found in PT and PG for both depth levels. Seasonal differences were only observed for the deep soil layer in sites IM and CP, where contents were higher during the rainy season.

The majority of non-residual Fe was present in the form of crystalline oxyhydroxides (FeCri) and associated with the reduced fraction (FeRed), except for the values found in PT during the dry season, where contents were similarly distributed among fractions FeAm, FeCri, and FeRed (

Table 3). FeExCa and FeAm contents ranged from 2.4 to 133.0 mg kg

-1 and from 0.3 to 944.1 mg kg

-1, respectively, and were higher in IM and CP, while FeCri contents were generally higher in IM except for the values observed in the surface soil layer during the rainy season in this site, which did not differ from the concentrations found in CP and PG. FeRed, was higher in IM and CP, with the exception of the surface soil layer during the dry season.

Seasonal variations were only observed in the CP mangrove, where FeExCa concentrations in the deep layer were higher during the dry season. Regarding depth, differences were observed for FeAm (rainy season) and FeCri (dry season) contents in IM, where values found in surface soils (FeAm: 356±90 mg kg-1; FeCri: 1828±181 mg kg-1) were higher than those in deep soils (FeAm:107±53 mg kg-1; FeCri: 1154±76.8 mg kg-1), as well as higher than FeRed contents in PT (rainy season), which were significantly higher in the deep layer (1721±853 mg kg-1).

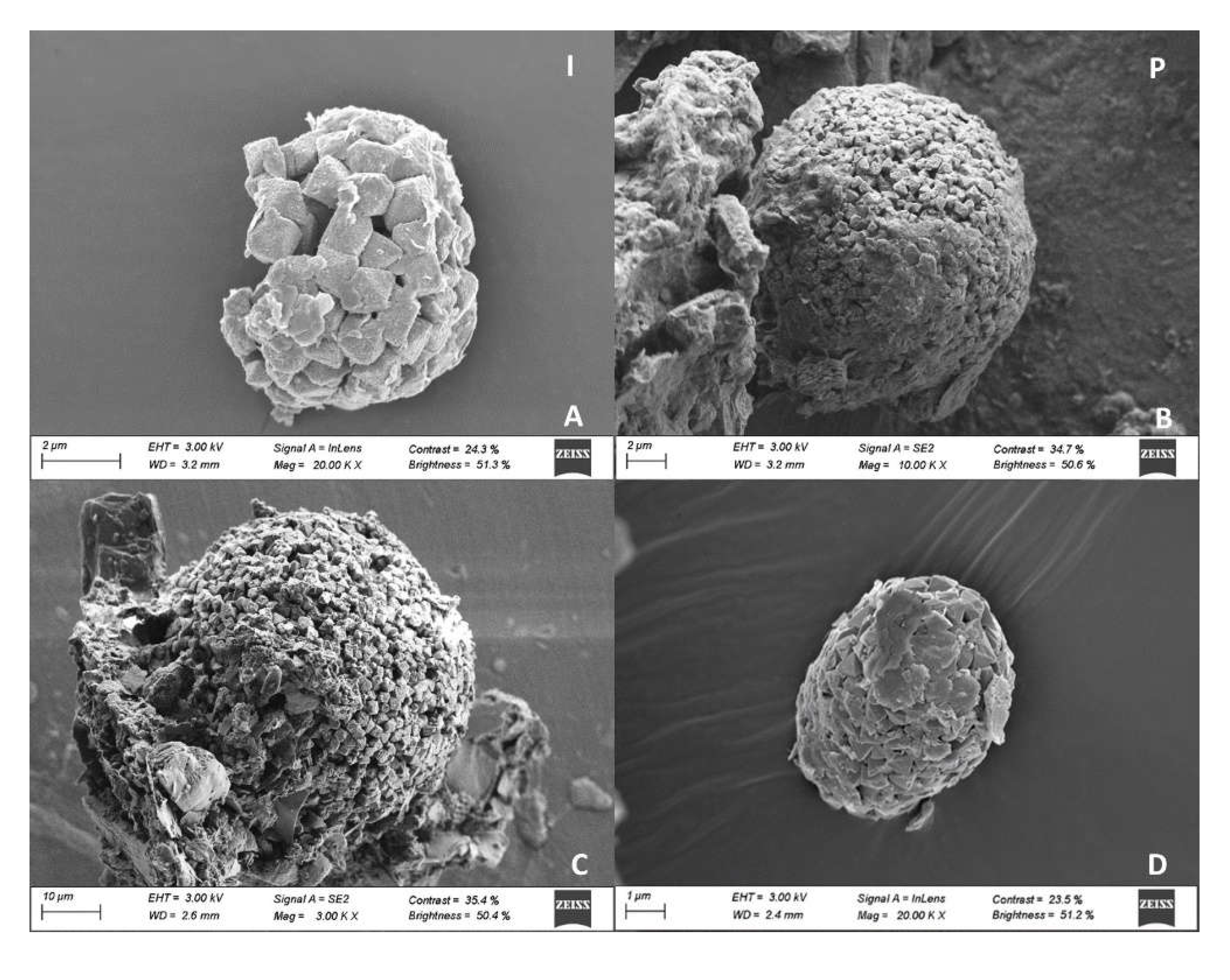

3.5. Pyrite morphology

A total of 51 pyrites of different morphologies were identified at the FESEM. Pyrite crystals were present in soils in three main morphologies (

Figure 6): isolated euhedral crystals, forming framboids (aggregations of pyrite crystals), and polyframboids (aggregation of framboids). Isolated crystals were generally smaller than 1 µm (mean size: 1.1±0.9 µm; range: 0.10 - 2 µm); most framboids were 10-25 µm in size, and polyframboids showed markedly larger sizes, generally between 50 and 75 µm (

Figure 7-9).

Individual pyrite crystals (28 occurrences) showed a predominantly octahedral habit (

Figure 7 E, F, G) in all mangrove sites, with truncated octahedral crystals only found in IM (Fig. 7C, D). Isolated crystals with signs of degradation were identified in PT and PG, including the presence of perforations and poorly defined vertices (Fig. 7F, G, H).

Framboids were mainly spherical in shape, although subspherical shapes were also recorded, as well as some aggregates with undefined shape, mostly constituted by uniformly sized crystals. However, one framboid found in PT showed microcrystals of different sizes from that of crystals forming the aggregate; these microcrystals were present on the surface and had an undefined habit (

Figure 8D). Crystals present in framboids showed variable habits: octahedral, truncated-octahedral, and cubic (

Figure 8). Except for IM, framboids with signs of degradation were observed in all mangrove sites, including alterations in shape (

Figure 9A), presence of perforations, and poorly defined vertices (

Figure 9B, C, D).

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity in mangrove soils

Intertidal environments are considered highly dynamic biogeochemical environments whose acid-base and redox conditions can oscillate widely from hyperacidic (pH<3.5) to neutral (pH ~6.5) and from anoxic (Eh<100 mV) to oxic (Eh>400mV) [

10,

28]. In mangrove soils, these changes are mainly driven by hydroperiod dynamics, which encompasses all components of the water budget (rainfall, evaporation, and subsurface and surface flow). Seasonal changes are one of the main environmental factors with the highest influence on edaphic and biogeochemical processes in soils of intertidal environments such as mangrove forests [10-12]. In tropical and subtropical areas, two seasons (dry and rainy) can mainly be differentiated, the drastic changes in temperature and rainfall between them substantially affecting water availability in ecosystems; such is the case of the BTS [21, 22].

Consistently with the complex interaction among factors regulating sedimentary and biogeochemical processes in coastal environments, soils in the BTS showed spatial differences affecting both their composition and their properties. Granulometric composition was a clear example of spatial variability, with differences in particle size according to the different sedimentary conditions along the coastal area [

29,

30]. Mangroves in PT and PG are close to river mouths, while CP is close to the Atlantic Ocean; both are high-energy environments, which can explain the higher proportion of the sand fraction in these areas [23; 30]. Conversely, IM is located in the middle of the BTS and is therefore more sheltered from wave action and from marine and river currents [

23].

Acid-base conditions showed spatial and seasonal changes. Acidity conditions in mangrove soils during the rainy season were close to neutrality, which is consistent with the reduction processes that are typical of flooded soils, leading to the consumption of protons, particularly associated with the reduction of Fe oxyhydroxides and sulfates (reactions 1 and 2) [

6,

8,

31].

Conversely, a different spatial pattern was observed during the dry season, with significant differences among mangrove sites and with soils ranging from highly acidic in PT to neutral in the remaining sites. The higher acidity and Eh in PT soils are consistent with their lower water saturation (

Figure 3), which promotes soil aeration. Additionally, the more sandy texture observed in PT soils, together with the higher relief related to the riverbed, promotes faster drainage and higher levels of soil aeration, with the subsequent oxidation of Fe sulfates according to reactions 3 and 4, leading to proton release and decreased pH [

32,

33]. Moreover, the small size observed for many isolated pyrite crystals (<1 µm,

Figure 7) provides them with a large specific surface area and a high reactivity, promoting their rapid oxidization.

The presence of a large number of degraded pyrites with signs of alteration in this mangrove site, as well as the low contents of Fe associated with the reduced fraction (FeRed) during the dry season, confirmed the pattern observed for pH and Eh and suggested a higher oxidative dissolution of sulfates (FeS and FeS2) in this area, mainly during the period with lower water availability (reactions 3 and 4) (6,26,31].

4.2. Variation of organic matter composition in mangrove soils

Mangrove soils are currently recognized as one of the marine ecosystems that store the greatest amounts of organic C (over 900 Mg ha

-1), known as blue carbon (Pérez et al., 2018). In our case, the content of organic C stored in mangrove soils showed great spatial variability, with mean TOC values ranging from 1.0% to 6.0% (

Table 1). The high spatial variability systematically observed in organic C content in mangrove soils is particularly relevant to estimate the global C stock stored in marine ecosystems [

10,

31,

34].

However, the origin of the organic C stored in mangrove soils and sediments is still poorly known. Depending on local conditions, organic carbon entering mangrove soils is either produced autochthonously or imported by tidal currents and/or rivers. Mangrove litter and benthic microalgae are usually the most important autochthonous carbon sources, while phytoplankton and seagrass detritus imported by tidal currents may represent a significant supplementary carbon input in other circumstances [

35,

36].

Our results agree with those obtained by previous studies in that the specific characteristics of each study area play an essential role in organic C contents in mangrove soils. Thus, the highest TOC values observed in the IM site (6.0±0.5%) are consistent with an environment with a high sedimentary rate due to its lower energy promoting the deposition of fine particles (silt and clay) and presumably also of organic matter [

23,

37]; at the same time, minerals in the clay fraction exert a protective effect against the microbial degradation of organic matter [

38].

Comparing TOC contents with the results observed in other mangrove forests in Brazil, mean values in IM were higher than mean contents found in northeastern Brazil (2.2±1.5%) [

12], but lower than those found in southeastern Brazil (4.0-25%) [

6], (6.6-9.2%) [

7], (6.9±7.1%) [

33], as well as lower than the values recorded for mangroves in other regions of the world, such as New Caledonia (2-17%) [

39], Indonesia (16.4±2.1) [

40], and Venezuela (14.5±0.71%) [

41], which is consistent with the fact that organic matter content in mangrove forests depends on a wide range of factors (e.g. coastal morphology, type of vegetation, soil properties and composition, etc.) that define the coastal environmental setting [

34,

42].

In our case, the observed TOC contents also showed differences depending on forest composition, with the highest contents in areas colonized by R. mangle (IM and CP) compared with areas occupied by mixed mangrove forests (PG and PT). Differences in TOC values according to species composition of mangrove forests have also been observed in other studies, with enriched contents in soils occupied by

Rhizophora mangle [

39,

41], which could be associated with the more developed root system of this species [

39], as well as with differences in biomass and in carbon transformation processes [

41,

43,

44].

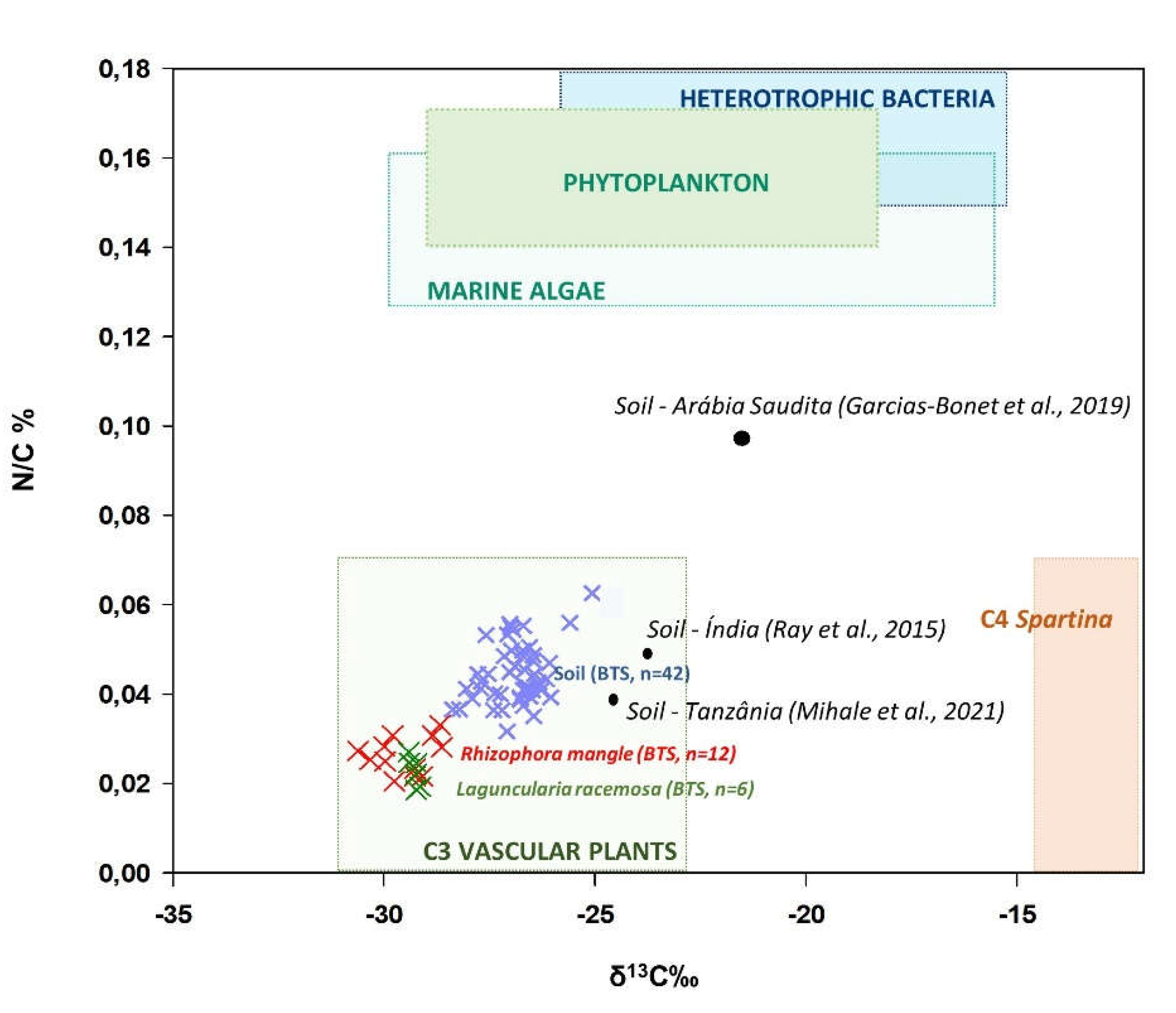

Most of the organic C contained in mangrove soils is generally associated with autochthonous sources, such as detritus from mangroves and roots, as well as benthic microalgae [

35,

45]. δ

13C values in soil (δ

13C: -26.9±0.6‰) were higher than those observed in plants (δ

13C: -29.4±0.5‰), unlike C/N ratios (soil: 22.8±3.4; leaves: 40.9±6.8), which were higher in leaf tissue. The observed differences suggest a progressive

13C enrichment of organic matter and C depletion in CO

2 [

46,

47]. On the other hand, the joint analysis of the δ

13C and C/N ratios suggests that part of the organic matter could have an allochthonous origin, mainly associated with terrestrial plants with C3 metabolism (

Figure 10) [

40,

48,

49].

Phytoplankton and marine algae are more enriched in the heaviest C isotope (

13C), leading to a higher δ

13C ratio, with values ranging from -23‰ to -17‰; this is due to the origin of the C used in marine photosynthesis, both from CO2 (lower δ

13C) and from HCO

3- (higher δ

13C), while terrestrial plants use only atmospheric CO

2, therefore showing lower δ

13C values [

48,

49]. Isotope patterns and N/C ratios in soils from the BTS were similar to those found in Tanzania [

45] and India [

50], but different from the patterns observed in Saudi Arabia [

51], where organic matter showed a greater contribution from phytoplankton and C4 plants (

Figure 10).

4.3. Spatiotemporal variability of geochemical forms of Fe in mangrove soils

Mangroves are located in the transition zone between the terrestrial and the marine environment and, despite the narrow strip they occupy within the coastal area, they experience spatial changes in their characteristics, particularly in those affected by flooding, such as redox processes, which in turn affect the geochemical forms of redox-sensitive elements (e.g. Fe, S). Geochemical Fe partitioning revealed clear differences among sites, with higher values for all fractions in IM. The high contents found in IM could be explained by the lower energy of the system, which promotes the deposition of small-sized particles (clay and silt) and metal and organic colloids [

52,

53]. The anoxic conditions also promote Fe precipitation and sulfate formation, mainly as pyrite [

8].

The results showed clear spatial differences in concentrations of the different forms of Fe, while seasonal differences were not as evident, particularly in the deep layer. At the spatial level, it is worth highlighting that crystalline Fe oxyhydroxides and pyritic Fe were the dominant forms of Fe across all mangrove sites, accounting for 23.6±3.8% and 70.0±3.8%, respectively, of potentially reactive Fe in CP, PG, and IM. Meanwhile, the distribution pattern in PT was different during the dry season, with reactive Fe mainly present in the amorphous oxyhydroxide (38.5±10.5%) and crystalline oxyhydroxide phases (41.0±14.7%), while pyritic Fe accounted for 17.3±10.4% of non-residual Fe.

Pyrite shows high stability under reduced conditions [

8]; however, the observed redox conditions and the presence of degraded pyrites in most mangrove sites suggest their instability and oxidization to Fe oxyhydroxides (

Figure 11). In intertidal environments, Fe sulfates, and especially pyrite, are subjected to intense recycling as a result of the alternating oxic and anoxic conditions experienced by these soils due to seasonal changes affecting water availability in the system, as well as biological activity (e.g. crab reproductive activity, plant flowering, etc.) [

7,

9,

11,

54].

Amorphous Fe oxyhydroxides represent less than 9% of reactive Fe, with a clear decrease during the rainy season, consistently with the lower thermodynamic stability of this fraction under prolonged flooding conditions, as well as with the rapid microbial reduction of these Fe forms in suboxic and anoxic environments compared with crystalline Fe oxyhydroxides [55-57]. Crystalline Fe oxyhydroxides, in turn, experienced an increase during the dry period as a result of pyrite oxidization, a process that first leads to amorphous oxyhydroxides, with the subsequent generation of crystalline forms within a relatively short period [

55].

Soluble or exchangeable Fe forms (range: 12.4-133.0 mg kg

-1) represented 2.1±1.9% of the non-residual content. This fraction corresponds to Fe

2+, which is highly unstable in mangrove soils due to fluctuations in redox conditions, being rapidly consumed under oxic conditions and precipitating as Fe (III) oxyhydroxides, while under anoxic conditions, it is consumed to form sulfates as a result of the predominance of sulfate and Fe reduction pathways [

58]. The Eh-pH conditions observed for most samples suggest a higher stability of Fe oxyhydroxides, with the most stable Fe

2+ found in the PT mangrove, where the system reaches highly acidic conditions (

Figure 11). The higher Fe

2+ values observed in IM could correspond to low-crystallinity FeS forms solubilized during the first extraction step, according to the reaction:

The mainly suboxic redox conditions observed in these mangrove forests are consistent with the results obtained for mangroves within the BTS [

20] and in other regions in northeastern Brazil [

33], and these can be related to climate conditions [

33], as well as to the shallow depth at which samples were collected (0-30 cm), where bioturbation associated with plants and crabs contributes to soil oxygenation, leading to pyrite destruction [

26,

35,

54].

Pyrites occurred mainly as framboids and isolated crystals, consistently with the results found in other reducing marine environments [

26,

59], with crystals showing a mainly octahedral habit and generally found in soils with high sulfur contents [

60]. Crystals of cubic habit were only observed in IM, which could be associated with a higher Fe content in soils of this area [

61]. Octahedral, pyritohedral, and cubic habits are among the most commonly observed in pyrites, which can also occur in intermediate forms, such as the truncated-octahedral one found in IM. Differences in habits are associated with differences in pyrite growth conditions, which vary among mangrove forests and are influenced by granulometry, organic matter content, and nutrient availability [

62].

A large portion of pyrites showed signs of degradation, including perforations, shape alterations, and poorly defined crystal vertices, with smaller framboid sizes (1.9±1.9 µm) than those observed in other coastal systems in Brazil [

63] and worldwide [

26,

59], which may suggest alternating redox conditions during their formation and growth periods [

64]. Moreover, the presence of these alterations indicates the occurrence of degradation by oxidization in these areas, associated with the role of tidal fluctuations and bioturbation on the alteration of redox conditions [

26,

54].

The lower stability of pyrites in these mangroves in the face of oxidative processes could also have been favored by their small size, which leads to higher reactivity. In addition, the presence of a large proportion of crystals of octahedral habit supports their greater instability, as they are subjected to weathering to a greater degree due to their mineral facet {111}, compared with faceted crystals {100}, such as cubic ones [

65].

5. Conclusions

Soil parameters and components showed spatial heterogeneity, with differences affecting soil attributes and composition. The environments identified within the BTS ranged from strongly reduced ones, associated with low-energy areas with higher deposition of finer fractions and organic matter, to mangroves with predominantly sandy texture, which promotes aeration and favors stability of Fe (III) oxyhydroxides to the detriment of pyrite. On the other hand, physicochemical conditions of soils, the results from sequential extraction, and electron microscopy images seem to suggest that pyrites are found in conditions of instability, with the exception of those in Ilha de Maré (IM), where pyrites showed well-developed habits.

Organic matter in mangrove soils seems to have a mixed origin, both associated with local (autochthonous) and allochthonous terrestrial production, with low contribution from phytoplankton and seaweed. Seasonal changes also contribute to increasing the heterogeneity and complexity of geochemical processes in mangrove soils within the BTS, while no clear general pattern can be observed for all the study sites.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Surface chemical composition of pyrite from the mangrove soil of Ilha de Maré; Table S1: Physical chemical attributes and soil components of the mangroves of Ilha de Maré, Ponta Grossa, Pitinga and Cacha Prego.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Conceptualization, M.A.V.R., A.P.A., G.N.N, X.L.O.; methodology, M.A.V.R., A.P-A., G.N.N, X.L.O; software, não se aplica; validation, M.A.V.R., A.P-A., G.N.N, X.L.O; formal analysis, M.A.V.R., A.P-A., G.N.N, X.L.O; investigation, M.A.V.R., A.P-A., G.N.N, X.L.O; resources, M.A.V.R., A.P-A., G.N.N, X.L.O; data curation, M.A.V.R., A.P-A., G.N.N, X.L.O; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.V.R., A.P.A., G.N.N, X.L.O; writing—review and editing, , M.A.V.R., A.P-A., G.N.N, X.L.O; visualization, M.A.V.R., A.P.A., G.N.N, X.L.O; supervision, X.L.O.; project administration, X.L.O.; funding acquisition, X.L.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-funded by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) do Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologias e Inovações do Brasil, Project titled “Desenvolvimento do Índice de Qualidade das Florestas de manguezais na Baía de Todos Santos (BTS), Bahia” (n°441389/2017-1) and the Consellería de Educación, Universidade e Formación Profesional-Xunta de Galicia (Axudas á consolidación e estruturación de unidades de investigación competitivas do SUG do Plan Galego IDT, Ambiosol Group ref. ED431C; 2022/40).

Data Availability Statement

Most of the results are presented in the tables of the manuscript and in the supplementary material. The results with which the figures have been elaborated can be requested directly from the corresponding author (augustoperezalberti@gmail.com) or M.A.V.R. (monica.ramos@ufrb.edu.br).

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to María José Santiso for her assistance with laboratory work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Feller, I. C. , Lovelock, C. E., Berger, U., Mckee, K. L., Joye, S. B., Ball, M. C. Biocomplexity in Mangrove Ecosystems. Annual Review of Marine Science, 2010 2:1, 395-417.

- Alongi. D. M. Mangrove forests: Resilience, protection from tsunamis, and responses to global climate change. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 2008; 76, 1–13.

- Nóbrega, G.; Ferreira, T.O.; Siqueira, M.; Mendonça, E.; Romero, R. E.; Otero, X. L. The importance of blue carbon soil stocks in tropical semiarid mangroves: a case study in Northeastern Brazil. Environmental Earth Science, 2019 78:369. [CrossRef]

- Nóbrega, G. N., Otero, X. L., Romero, D. J., Queiroz, H. M., Gorman, D., Copertino, M. S., Piccolo, M. C., Ferreira, T. O. Masked diversity and contrasting soil processes in tropical seagrass meadows: the control of environmental settings. Egusphere, 2022,. [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, E., Connolly, R.M.; Otero, X.L., Marchand, C.; Ferreira, T.O.; Ribera-Monroy, V.H. Biogeochemical cycles: Global approaches and perspectives. In Mangrove ecosystems: a global biogeographic perspective (V.H. Rivera-Monroy, S.Y. Lee, E. Kristensen, R.R. Twilley, eds). Springer, 2017, Chapter 6 pp 163-220.

- Ferreira, T. O. , Otero, X. L., Vidal-Torrado, P., Macías, F. Redox Processes in Mangrove Soils under Rhizophora mangle in Relation to Different Environmental Conditions. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2007a; 71, 484–491. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, T. O., Vidal-Torrado, P., Otero, X. L., Macías, F. Are mangrove forest substrates sediments or soils? A case study in southeastern Brazil. Catena 70, 79–91. Geoderma, 2007b, 142, 36–46.

- Otero, X.L., Ferreira, T.O., Huerta-Díaz, M.A., Partiti, C.S.M., Souza Jr., V., Vidal-Torrado, P., Macías, F. Geochemistry of iron and manganese in soils and sediments of a mangrove system, Island of Pai Matos (Cananéia — SP, Brazil). Geoderma, 2009, 148, 318–335.

- Otero, X. L., Macías, F. Spatial variation in pyritization of trace metals in salt-marsh soils. Biogeochemistry, 2003, 62: 59–86.

- Ferreira, T. O, Otero, X, L., Souza-Júnior, V. S., Vidal-Torrado, P., Macías, F., Firme, L. P. Spatial patterns of soil attributes and componentes in a mangrove system in Southeast Brazil (São Paulo). J Soils Sediments, 2010, 10:995–1006.

- Otero, X. L., Macías, F. Variation with depth and season in metal sulfides in salt marsh soils. Biogeochemistry, 2002, 61, 247–268.

- Nóbrega, G.N., Ferreira, T.O., Romero, R.E., Marques, A.G.B., Otero, X.L. Iron and sulfur geochemistry in semi-arid mangrove soils (Ceará, Brazil) in relation to seasonal changes and shrimp farming effluents. Environ. Monit. Assess., 2013, 185:7393 7407. [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer-Novelli, Y. Mangue e manguezal. In: ICMBIO – Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade. Atlas dos manguezais do Brasil. Brasília: Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade, 2018. chap. 1, 15-20.

- Hadlich, G.M.; Ucha, J.M.; Celino, J.J. Apicuns na Baía de Todos os Santos: distribuição espacial, descrição e caracterização física e química. In: Queiroz, A.F. S. Celino, J.J. (Coords.), Avaliação de ambientes na Baía de Todos os Santos: aspectos geoquímicos, geofísicos e biológicos. Salvador: UFBA, 2008, p. 59-72.

- Pinheiro, L. S., Coriolano, L. N., Costa, M. F., Dias, J. A. O nordeste brasileiro e a gestão costeira. Journal of integrated coastal zone management, 2008, v.8, n.2, 5-10.

- Hatje, V., Barros, F., Figueiredo, D. G., Santos, V. L. C. S., Peso-Aguiar, M. C. Trace metal contamination and benthic assemblages in Subaé estuarine system, Brazil. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2006, 52, 969–987.

- Barros, F., Costa, P. C., Cruz, I., Mariano, D. L. S., Miranda R. J. Habitats Bentônicos na Baía de Todos os Santos. Rev. Virtual Quim., 2012, 4, 5, 551-565.

- Milazzo, A. D. D., Van Gestel, C. A. M., Cruz, M. J. M. Spatio-temporal variation of metal concentrations in estuarine zones of the todos os santos Bay, Bahia, Brazil. Geociências, 2020, v. 39, n. 1, 153 – 169.

- Santos, L. L., Miranda, D., Hatje, V., Alberfaria-Barbosa, A. C. R., Leonel, J. PCBs occurrence in marine bivalves and fish from Todos os Santos Bay, Bahia, Brazil. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2020, 154, 111070.

- Bomfim, M. R., Santos, J. A. G., Costa, O. V., Otero, X. L., Boas, G. S. V., Capelão, V. S., Santos, E. S., Nacif, P. G. S. Genesis, Characterization, and Classification of Mangrove Soils in the Subaé River Basin, Bahia, Brazil. R. Bras. Ci. Solo, 2015, 39:1247-1260.

- Lessa, G. C., Dominguez, J. M. L., Bittencourt, A. C. S. P., Brichta, A. The Tides and Tidal Circulation of Todos os Santos Bay, Northeast Brazil: a general characterization. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc., 2001, 73 (2), 245-261.

- Lessa, G. C., Cirano, M., Genz, F., Tanajura, C. A. S., Silva, R. R. Oceanografia física. In: Hatje, V. Andrade, J. B. (Org.). Baia de Todos os Santos: aspectos oceanográficos. Salvador: EDUFBA, 2009.

- Lessa, G. C., Bittencourt, A.C.S.P., Brichta, A., Dominguez, J. M. L. A Reevaluation of the Late Quaternary Sedimentation in Todos os Santos Bay (BA), Brazil. An. Acad. Bras. Ci., 2000, 72 (4), 573-589.

- Rauret, G, López-Sánchez, J. F., Sahuquillo, A., Rubio, R., Davidson, C., Ureb, A., Quevauvillerc, P. H. Improvement of the BCR three step sequential extraction procedure prior to the certification of new sediment and soil reference materials. J. Environ. Monit., 1998, 1, 57–61.

- Tessier, A., Campbell, P. G. C., Bisson, M. Sequential Extraction Procedure for the Speciation of Particulate Trace Metals. Analytical chemistry, 1979, 51, 7. 844-851.

- Otero, X. L., Guevara, P., Sánchez, M., López, I., Queiroz, H. M., Ferreira, A., Ferreira, T. O., Nóbrega, G. N., Carballo, R. Pyrites in a salt marsh-ria system: Quantification, morphology, and mobilization. Marine Geology, 2023, 455, 106954.

- Reimann, C., Filzmoser, P., Garrett, R.G., Dutter, R. Statistical Data Analysis Explained, Statistical Data Analysis Explained: Applied Environmental Statistics with R. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK, 2008.

- Otero, X. L., Sánchez, J. M., Macías, F. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in thionic fluvisols by a marine polychaete: the role of metal sulfides. J. Environ. Qual., 2000, 29, 1133-1141.

- Silva, M. A. B., Bernini, E., Carmo, T. M. S. Características estruturais de bosques de mangue do estuário do rio São Mateus, ES, Brasil. Acta Bot. Bras., 2005, 19(3): 465-471. 4: 19(3).

- Souza-Júnior et al., V. S., Vidal-Torrado, P., Tessler, M. G., Pessenda, L. C. R., Ferreira, T. O., Otero, X. L., Macías, F. Evolução quaternária, distribuição de partículas nos solos e ambientes de sedimentação em manguezais do estado de São Paulo. R. Bras. Ci. Solo, 2007, 31:753-769.

- Otero X.L, Méndez A, Nóbrega GN, et al. High fragility of the soil organic C pools in mangrove forests. Mar. Pollut. Bull., 2017, 119: 460–64. 4: 119.

- Berrêdo, J. F., Costa, M. L., Vilhena, M. S. P., Matos, C. R. L. Modificações nas propriedades físico-químicas de sedimentos de manguezais submetidos ao clima amazônico. Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi. Cienc. Nat., 2016, v. 11, n. 3, p. 313-328. 11.

- Ferreira, T. O., Queiroz, H. M., Nóbrega, G. N., Souza Júnior, V. S., Barcellos, D., Ferreira, A. D., Otero, X. L. Litho-climatic characteristics and its control over mangrove soil geochemistry: A macro-scale approach. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 811, 152152.

- Twilley, R.R., Rovai, A.S., Riul, P. Coastal morphology explains global blue carbon distributions. Front Ecol Environ, 2018, 16(9): 503–508, doi: 10.1002/fee.1937. 5: 16(9). [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, E., Bouillon, S., Dittmar, T., Marchand, C. Organic carbon dynamics in mangrove ecosystem. Aquat. Bot., 2008, 89 (2), 210–219.

- Bouillon, S., Dahdouh-Guebas, F., Rao, A.V.V.S., Koedam, N., Dehairs, F. Sources of organic carbon in mangrove sediments: variability and possible ecological implications. Hydrobiologia, 2003, 495, 33–39.

- Pérez, A., Libardoni, B.G., Sanders, C.J. Factors influencing organic carbon accumulation in mangrove ecosystems. Biol. Lett., 2018, 14: 20180237. [CrossRef]

- Hassink, J. The capacity of soils to preserve organic C and N by their association with clay and silt particles. Plant and Soil, 1997, 191, 77–87.

- Marchand, C., Fernandez, J.-M., Moreton, B., Landi, L., Lallier-Vergès, E., Baltzer, F. The partitioning of transitional metals (Fe, Mn, Ni, Cr) in mangrove sediments downstream of a ferralitized ultramafic watershed (New Caledonia). Chemical Geology, 2012, 300-301, 70–80.

- Sasmito, S. D., Kuzyakov, Y., Lubis, A. A., Murdiyarso, D., Hutley, L. B., Bachri, S., Friess, D. A., Martius, C., Borchard, N. Organic carbon burial and sources in soils of coastal mudflat and mangrove ecosystems. Catena, 2020, 187, 104414. 1044.

- Barreto, M. B., Mónaco, S. L., Díaz, R., Barreto-Pitto, E., López, L., Peralba, M. C. R. Soil organic carbon of mangrove forests (Rhizophora and Avicennia) of the Venezuelan Caribbean coast. Organic Geochemistry, 2016, 100, 51–61.

- Rovai, A.S., Twilley, R.R., Castañeda-Moya, E., Riul, P., Cifuentes-Jara, M., ManrowVillalobos, M., Horta, P.A., Simonassi, J.C., Fonseca, A.L., Pagliosa, P.R.Global controls on carbon storage in mangrove soils. Nat. Clim. Change, 2018, 8, 534–538. [CrossRef]

- Mckee. L. Determinants of mangrove species distribution in neotropical forests: biotic and abiotic factors affecting seedling survival and growth. Dissertation. Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA, 1993.

- Alongi, D. M., Tirendi, F., Clough, B. F. Below-ground decomposition of organic matter in forests of the mangroves Rhizophora stylosa and Avicennia marina along the arid coast of Western Australia. Aquatic Botany, 2000, 68, 97–122.

- Mihale, M. J., Tungaraza, C., Baeyens, W., Brion, N. Distribution and Sources of Carbon, Nitrogen and Their Isotopic Compositions in Tropical Estuarine Sediments of Mtoni, Tanzania. Ocean Science Journal, 2021, 56:241–255. [CrossRef]

- Blair N, Leu A, Munoz E, Olsen J, Kwong E, Des Marais D. Carbon isotope fractionation in heterotrophic microbial metabolism. Appl Environ Microbiol, 1985, 50:996–1001.

- Natelhoffer K.J., Fry, B.Controls on Natural Nitrogen-15 and Carbon-13 Abundances in Forest Soil Organic Matter. Soil Sci. Am. J., 1988, 52, 1633-1640.

- Bouillon, S., Connolly, R. M., Lee, S. Y. Organic matter exchange and cycling in mangrove ecosystems: Recent insights from stable isotope studies. Journal of Sea Research, 2008, 59, 44-58.

- Leng, M.J., Lewis, J.P. C/N ratios and carbon isotope composition of organic matter in estuarine environments. Applications of Paleoenvironmental Techniques in Estuarine Studies Developments in Paleoenvironmental Research, 2017, 213-237.

- Ray, R., Rixen, T., Baum, A., Malik, A., Gleixner, G., Jana, T. K. Distribution, sources and biogeochemistry of organic matter in a mangrove dominated estuarine system (Indian Sundarbans) during the pre-monsoon. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 2015, 167, 404-413.

- Garcias-Bonet, N., Delgado-Huertas, A., Carrillo-de-Albornoz, P., Anton, A., Almahasheer, H. Marbà, N., Hendriks, I. E., Krause-Jensen, D., Duarte, C.Mn.Carbon and Nitrogen Concentrations, Stocks, and Isotopic Compositions in Red Sea Seagrass and Mangrove Sediments. Front. Mar. Sci., 2019, 6:267. [CrossRef]

- Harbison, P. Mangrove Muds-A Sink and a Source for Trace Metals. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 1986, v. 17, n. 6, pp. 246-250.

- Soto-Jiménez, M. F., Páez-Osuna, F. Distribution and Normalization of Heavy Metal Concentrations in Mangrove and Lagoonal Sediments from Mazatlán Harbor (SE Gulf of California). Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 2001, 53, 259–274.

- Ferreira, T. O., Otero, X. L, Vidal-Torrado, P., Macías, F. Effects of bioturbation by root and crab activity on iron and súlfur biogeochemistry in mangrove substrate. Geoderma, 2007c, 142: 36-46. 3: 142.

- Cornell, R. M., Giovanoli, R., Schneider, W. Review of the hydrolysis of iron (III) and the crystallization of amorphous iron (III) hydroxide hydrate. Journal of Chemical and technology and biotechnology, 1989, 46, 115-134.

- Canfield, D. E. Reactive iron in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 1989, 53:619-632.

- Canfield D.E., Raiswell R. and Bottrell S. The reactivity of sedimentary minerals towards sulfide. Am. J. Sci., 1992, 292: 659–683. 6: 292.

- Otero, X. L. , Souza, M. L., Macías, F. Iron and trace metal geochemistry in mangrove soils. In: Pérez, X.L.O., Vázquez, F.M. (Eds.), Biogeochemistry and Pedogenetic Process in Saltmarsh and Mangrove Systems. Nova Science Publishers Inc., New York, 2010, pp. 1–24.

- Ding, H. Yao, S., Chen, J. Authigenic pyrite formation and re-oxidation as na indicator of an unsteady-state redox sedimentary environment: Evidence from the intertidal mangrove sediments of Hainan Island, China. Continental Shelf Research, 2014, 78: 85–99.

- Arrouvel, C., Eon, J.G. Understanding the Surfaces and Crystal Growth of Pyrite FeS2. Materials Research, 2019, 22 (1): e20171140.

- Barnard, A. S., Russo, S. P. Modelling nanoscale FeS2 formation in sulfur rich conditions. J. Mater. Chem., 2009, 19: 3389–3394. 3: 19.

- Rickard, D. Sulfidic Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks. Developments in Sedimentology, Vol. 65. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Aragon, G. T., Miguens, F. C. Microscopic analysis of pyrite in the sediments of two Brazilian mangrove ecosystems. Geo-Marine Letters, 2001, 21:157-161.

- Wilkin, R. T., Barnes, H. L., Brantley, S. L. The size distribution of framboidal pyrite in modern sediments: An indicator of redox conditions. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1996, v. 60, n. 20, 3897-3912.

- Du, R., Xian, H., Wu, X., Zhu, J., Wei, J., Xing, J., Tan, W., He, H. Morphology dominated rapid oxidation of framboidal pyrite. Geochem. Persp. Let., 2021, 16, 53–58.

- Brookins, D.G. Eh–pH diagrams for geochemistry. Springer-Verlang, Berlin, 1985.

Figure 1.

Map showing the locations of sampling sites in mangroves within Baía de Todos os Santos (BTS). Sites IM and CP correspond to single-species Rhizophora mangle forests, while PT and PG are mixed R. mangle and Laguncularia racemosa forests.

Figure 1.

Map showing the locations of sampling sites in mangroves within Baía de Todos os Santos (BTS). Sites IM and CP correspond to single-species Rhizophora mangle forests, while PT and PG are mixed R. mangle and Laguncularia racemosa forests.

Figure 2.

Percentages of sand and fine fraction (silt and clay) in mangrove soils from Ponta Grossa (PG, n= 06), Cacha Prego (CP, n= 06), Ilha de Maré (IM, n=06), and Pitinga (PT, n=06). For each depth (i.e. 0-5 cm and 15-30 cm), lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p<0.05) in granulometric composition among sites, while (*) indicates significant differences between depths within the same site (p<0.05); ns: indicates that variations between depths within the same site were not significant (p>0.05).

Figure 2.

Percentages of sand and fine fraction (silt and clay) in mangrove soils from Ponta Grossa (PG, n= 06), Cacha Prego (CP, n= 06), Ilha de Maré (IM, n=06), and Pitinga (PT, n=06). For each depth (i.e. 0-5 cm and 15-30 cm), lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p<0.05) in granulometric composition among sites, while (*) indicates significant differences between depths within the same site (p<0.05); ns: indicates that variations between depths within the same site were not significant (p>0.05).

Figure 3.

Water content in mangrove soils from Pitinga (PT), Ilha de Maré (IM), Ponta Grossa (PG), and Cacha Prego (CP) in the surface (n=12; 0-5 cm) and deep (n=12; 15-30 cm) soil layers during the dry (DS) and rainy (WS) seasons. For each season (DS and WS), different letters indicate significant differences among sites and between depths (p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Water content in mangrove soils from Pitinga (PT), Ilha de Maré (IM), Ponta Grossa (PG), and Cacha Prego (CP) in the surface (n=12; 0-5 cm) and deep (n=12; 15-30 cm) soil layers during the dry (DS) and rainy (WS) seasons. For each season (DS and WS), different letters indicate significant differences among sites and between depths (p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Water Spatial and seasonal variations in pH and Eh (PT: Pitinga; IM: Ilha de Maré; PG: Ponta Grossa; CP: Cacha Prego) in the surface (0-5 cm) and deep (15-30 cm) soil layers. For each season (dry season, DS, and rainy season, WS), different letters indicate spatial differences both between depths and among sites, while (*) indicates significant seasonal differences within each site and depth.

Figure 4.

Water Spatial and seasonal variations in pH and Eh (PT: Pitinga; IM: Ilha de Maré; PG: Ponta Grossa; CP: Cacha Prego) in the surface (0-5 cm) and deep (15-30 cm) soil layers. For each season (dry season, DS, and rainy season, WS), different letters indicate spatial differences both between depths and among sites, while (*) indicates significant seasonal differences within each site and depth.

Figure 5.

Total Fe content (%) in surface (0-5 cm) and deep (15-30 cm) mangrove soils in Baía de Todos os Santos, both during the dry (DS) and rainy (WS) seasons. For each season, different letters indicate differences among sites (p<0.05), while (*) indicates seasonal variations.

Figure 5.

Total Fe content (%) in surface (0-5 cm) and deep (15-30 cm) mangrove soils in Baía de Todos os Santos, both during the dry (DS) and rainy (WS) seasons. For each season, different letters indicate differences among sites (p<0.05), while (*) indicates seasonal variations.

Figure 6.

Distribution of different pyrite morphologies in mangrove soils in Baía de Todos os Santos.

Figure 6.

Distribution of different pyrite morphologies in mangrove soils in Baía de Todos os Santos.

Figure 7.

Isolated pyrite crystals from mangrove soils in Baía de Todos os Santos.

Figure 7.

Isolated pyrite crystals from mangrove soils in Baía de Todos os Santos.

Figure 8.

Microphotographs of pyrite framboids from mangrove soils in Baía de Todos os Santos: A) and B) individual framboids composed of octahedral crystals from the Ponta Grossa and Ilha de Maré sites; C) individual framboid from the Ponta Grossa site, with a poorly defined shape and composed of octahedral crystals; D) framboid from the Pitinga site, with presence of microcrystals; E) subspherical framboid from Ilha de Maré, composed of octahedral crystals; F) individual framboid from Ilha de Maré, composed of cubic crystals.

Figure 8.

Microphotographs of pyrite framboids from mangrove soils in Baía de Todos os Santos: A) and B) individual framboids composed of octahedral crystals from the Ponta Grossa and Ilha de Maré sites; C) individual framboid from the Ponta Grossa site, with a poorly defined shape and composed of octahedral crystals; D) framboid from the Pitinga site, with presence of microcrystals; E) subspherical framboid from Ilha de Maré, composed of octahedral crystals; F) individual framboid from Ilha de Maré, composed of cubic crystals.

Figure 9.

Microphotographs of framboid clusters: A and B) microphotographs of framboid clusters from the Cacha Prego site; C and D) truncated octahedral crystals from Ilha de Maré; E) octahedral crystals on a diatomaceous skeleton from Ilha de Maré; F and G) octahedral crystals showing signs of oxidization, collected in Pitinga; H) crystals showing signs of oxidization, collected in Ponta Grossa.

Figure 9.

Microphotographs of framboid clusters: A and B) microphotographs of framboid clusters from the Cacha Prego site; C and D) truncated octahedral crystals from Ilha de Maré; E) octahedral crystals on a diatomaceous skeleton from Ilha de Maré; F and G) octahedral crystals showing signs of oxidization, collected in Pitinga; H) crystals showing signs of oxidization, collected in Ponta Grossa.

Figure 10.

Carbon isotope ratios (δ13C) and N/C ratios in soils and plants (Rhizophora mangle and Laguncularia racemosa) from the BTS, and potential sources of organic matter for mangroves in IM, PT, PG, and CP in relation to other mangrove forests in Brazil and worldwide.

Figure 10.

Carbon isotope ratios (δ13C) and N/C ratios in soils and plants (Rhizophora mangle and Laguncularia racemosa) from the BTS, and potential sources of organic matter for mangroves in IM, PT, PG, and CP in relation to other mangrove forests in Brazil and worldwide.

Figure 11.

Eh-pH diagram showing mineral stability of the Fe-S-O-H system in mangroves in Baía de Todos os Santos [

66].

Figure 11.

Eh-pH diagram showing mineral stability of the Fe-S-O-H system in mangroves in Baía de Todos os Santos [

66].

Table 1.

TOC, TN, δ13C (‰), and δ15N (‰) contents, and C/N ratio in mangrove soils (n=03). For each season, different uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p<0.05) among sites. For each site, different lowercase letters indicate differences according to depth.

Table 1.

TOC, TN, δ13C (‰), and δ15N (‰) contents, and C/N ratio in mangrove soils (n=03). For each season, different uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p<0.05) among sites. For each site, different lowercase letters indicate differences according to depth.

| Depth |

COT (%) |

TN(%) |

C/N |

δ13C (‰) |

δ15N (‰) |

| Dry season (DS) |

| IM |

0-5 cm |

6.0 ± 0.5Aa

|

0.32 ± 0.03Aa

|

19.1 ± 1.3Ab

|

-26.98 ± 0.24Aa

|

2.76 ± 0.53Aa

|

| 15-30 cm |

4.8 ± 0.3Ab

|

0.21 ± 0.02Ab

|

22.8 ± 1.1Aa

|

-26.58 ± 0.13ABa

|

2.20 ± 0.45Aa |

| PT |

0-5 cm |

1.3 ± 0.4Ba

|

0.07 ± 0.04Ba

|

19.9 ± 3.7Aa

|

-27.35 ± 0.21Aa

|

1.97 ± 0.52Aa

|

| |

15-30 cm |

1.1 ± 0.3Ba

|

0.05 ± 0.01Ba

|

20.2 ± 3.2Aa

|

-27.40 ± 0.54Ba

|

2.63 ± 0.51Aa

|

| CP |

0-5 cm |

2.5 ± 0.4Ba

|

0.10 ± 0.02Ba

|

24.7 ± 2.9Aa

|

-27.18 ± 0.26Aa

|

2.13 ± 0.41Aa

|

| |

15-30 cm |

3.2 ± 0.5Ba

|

0.12 ± 0.04Ba

|

26.7 ± 4.2Aa

|

-26.77 ± 0.27ABa

|

2.18 ± 0.46Aa

|

| PG |

0-5 cm |

1.3 ± 0.7Ba

|

0.06 ± 0.04Ba

|

23.5 ± 3.2Aa

|

-26.43 ± 0.49Aa

|

1.12 ± 0.93Aa

|

| |

15-30 cm |

1.4 ± 0.0Ba

|

0.06 ± 0.00Ba

|

24.9 ± 0.7Aa

|

-26.16 ± 0.16Aa

|

0.94 ± 0.39Ba

|

| Rainy season (WS) |

| IM |

0-5 cm |

5.9 ± 0.9Aa

|

0.30 ± 0.06Aa

|

19.6 ± 1.3Aa

|

-26.90 ± 0.16ABb

|

2.56 ± 0.29Aa

|

| 15-30 cm |

4.8 ± 0.3Aa

|

0.23 ± 0.01Aa

|

21.1 ± 1.7Aa |

-26.39 ± 0.21Aa

|

2.26 ± 0.69Aa

|

| PT |

0-5 cm |

1.5 ± 0.4Ca

|

0.06 ± 0.01Ba

|

23.2 ± 4.3Aa

|

-27.83 ± 0.33Ba

|

3.10 ± 0.63Aa

|

| 15-30 cm |

2.1 ± 0.6Ba

|

0.08 ± 0.02Ba

|

25.7 ± 1.6Aa

|

-28.00 ± 0.34Ba

|

2.37 ± 0.30Aa

|

| CP |

0-5 cm |

3.4 ± 0.8Ba

|

0.15 ± 0.04Ba

|

22.4 ± 2.4Aa

|

-27.04 ± 0.33ABa

|

2.63 ± 0.04Aa

|

| 15-30 cm |

2.5 ± 0.4Ba

|

0.11 ± 0.03Ba

|

23.0 ± 1.7Aa |

-26.51 ± 0.18Aa

|

2.74 ± 0.24Aa

|

| PG |

0-5 cm |

1.0 ± 1.2Ca

|

0.05 ± 0.03Ba

|

21.0 ± 4.4Aa

|

-26.09 ± 0.70Aa

|

1.20 ± 0.66Ba

|

| 15-30 cm |

1.9 ± 1.2Ba

|

0.07 ± 0.04Ba

|

26.9 ± 2.3Aa |

-26.50 ± 0.07Aa

|

1.12 ± 1.13Aa

|

Table 2.

C, N, δ13C, and δ15N contents and C/N ratio in Rhizophora mangle and Laguncularia racemosa leaves from mangroves in Baía de Todos os Santos (n=03). Different letters indicate spatial differences within the same species (p<0.05).

Table 2.

C, N, δ13C, and δ15N contents and C/N ratio in Rhizophora mangle and Laguncularia racemosa leaves from mangroves in Baía de Todos os Santos (n=03). Different letters indicate spatial differences within the same species (p<0.05).

| |

C (%) |

N (%) |

C/N |

δ13C (‰) |

δ15N (‰) |

| R. mangle |

| IM |

41.6± 0.8a

|

1.0 ± 0.2a

|

43.5 ± 7.2a

|

-29.7 ± 0.4bc

|

2.7 ± 0.4a

|

| CP |

40.4 ± 0.9a

|

1.0 ± 0.1a

|

38.7 ± 1.8a |

-30.3 ± 0.3c

|

2.2 ± 0.1a

|

| PT |

41.5 ± 0.5a

|

1.3 ± 0.1a

|

32.8 ± 2.7b

|

-28.7 ± 0.1a

|

0.9 ± 0.2b

|

| PG |

41.1 ± 1.0a

|

1.0 ± 0.2a

|

40.6 ± 7.2a

|

-29.4 ± 0.4ab

|

1.1 ± 0.6b

|

| L. racemosa |

| PT |

40.5 ± 0.3b

|

1.0 ± 0.2b

|

41.0 ± 4.1a

|

-29.3 ± 0.1b

|

2.9 ± 0.3a

|

| PG |

38.5 ± 1.6a

|

1.0 ± 0.2a

|

48.2 ± 7.2a

|

-29.2 ± 0.2a

|

1.8 ± 0.1b

|

Table 3.

Mean concentration (with standard deviation between parentheses) of geochemical fractions of Fe (mg kg-1) in soils (from Ilha de Maré, Pitinga, Ponta Grossa, and Cacha Prego during the dry (DS) and rainy (WS) seasons (n=03). Different uppercase letters indicate differences among sites within the same season, while lowercase letters indicate differences according to depth within the same site. * indicates significant seasonal differences (p<0.05).

Table 3.

Mean concentration (with standard deviation between parentheses) of geochemical fractions of Fe (mg kg-1) in soils (from Ilha de Maré, Pitinga, Ponta Grossa, and Cacha Prego during the dry (DS) and rainy (WS) seasons (n=03). Different uppercase letters indicate differences among sites within the same season, while lowercase letters indicate differences according to depth within the same site. * indicates significant seasonal differences (p<0.05).

| Depth |

FeExCa |

FeAm |

FeCri |

FeRed |

|

| |

DS |

WS |

DS |

WS |

DS |

WS |

DS |

WS |

| Ilha de Maré (IM) |

|

| S |

77.9 Aa

(21.3) |

68.0 Aa

(22.9) |

355Aa

(163) |

356 Aa

(90.2) |

1828 Aa

(181) |

2154 Aa

(816) |

5074 Aa

(3329) |

5855 Aa

(1580) |

| P |

63.3 Aa

(17.5) |

69.5 Aa

(8.9) |

196Aa

(68.1) |

107 ABb

(53.2) |

1155 Ab

(76.8) |

1243Aa

(65.5) |

7200 Aa

(2662) |

6819 Aa

(1437) |

| Pitinga (PT) |

|

| S |

39.6 Aa

(18.0) |

40.3 Aa

(11.3) |

613Aa

(335) |

136 Aa

(167) |

568 Ba

(368) |

346 Ba

(170) |

140 Aa

(7.9) |

313 Bb

(184) |

| P |

22.1 Aa

(5.8) |

14.9 Aa

(2.4) |

340Aa

(241) |

12.3 Ba

(5.7) |

279 Ba

(138) |

196 Ca

(50.1) |

160 Ba

(106) |

1722 Ca

(853) |

| Cacha Prego (CP) |

|

| S |

55.2 Aa

(10.3) |

85.1 Aa

(41.9) |

223 Aa

(30.4) |

513 Aa

(381) |

577 Ba

(73.1) |

1255 ABa

(773) |

2488 Aa

(1044) |

3621 Aa

(689) |

| P |

73.8 Aa*

(4.1) |

55.2 Aa*

(5.1) |

224 Aa

(108) |

325 Aa

(152) |

575 Ba

(63.3) |

630 Ba

(126) |

3782 ABa

(1828) |

4321 Ba

(851) |

| Ponta Grossa (PG) |

|

| S |

32.8 Aa

(27.5) |

33.8 Aa

(8.9) |

112 Aa

(46.5) |

54.5 Aa

(38.8) |

562 Ba

(633) |

629ABa

(573) |

1163 Aa

(1348) |

467 Ba

(471) |

| P |

35.0 Aa

(25.2) |

30.9 Aa

(15.1) |

46.5 Aa

(65.5) |

29.1 Ba

(26.5) |

395 Ba

(206) |

317 Ca

(43.3) |

881 Ba

(246) |

1082 Ca

(417) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).