Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

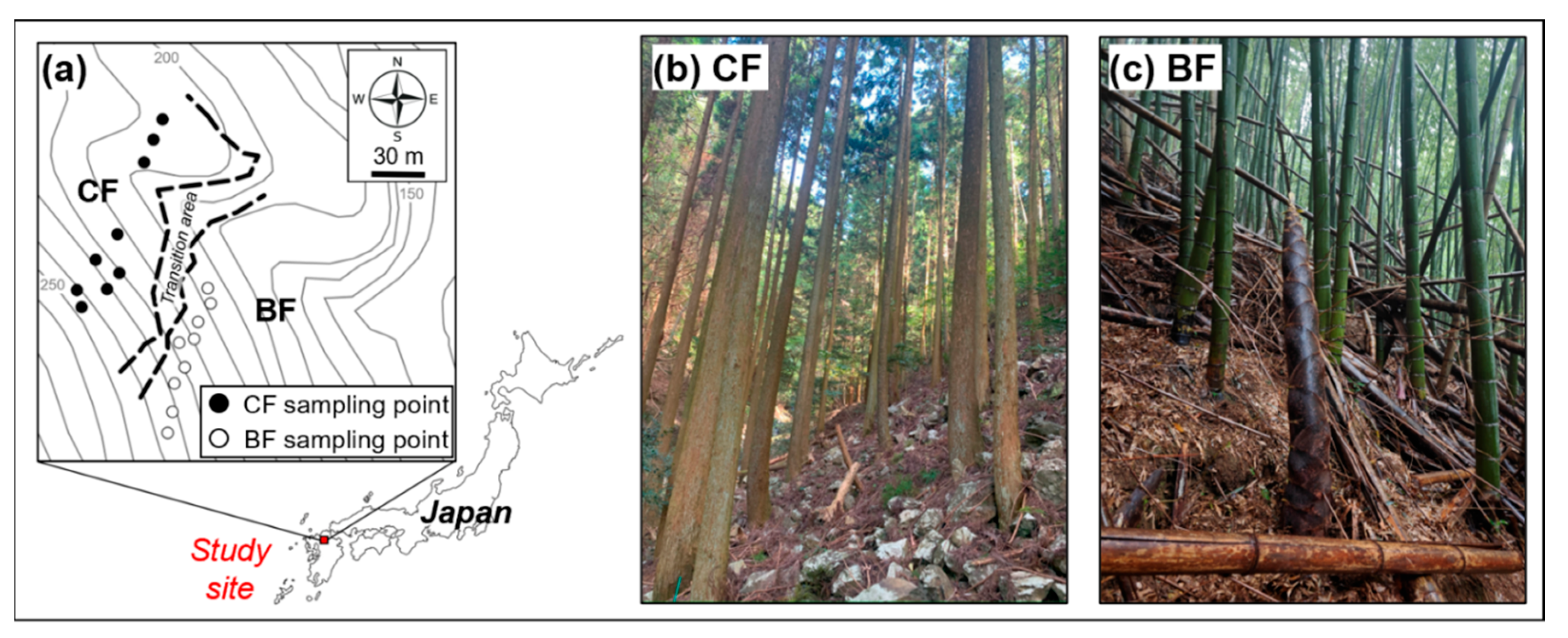

2.1. Site Description and Sampling Points for Soil Solution

2.2. Soil Solution Collection and Chemical Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Soil Solution Chemistry in Different Forest Types

3.2. Vertical Distribution Patterns of Soil Solution Chemistry

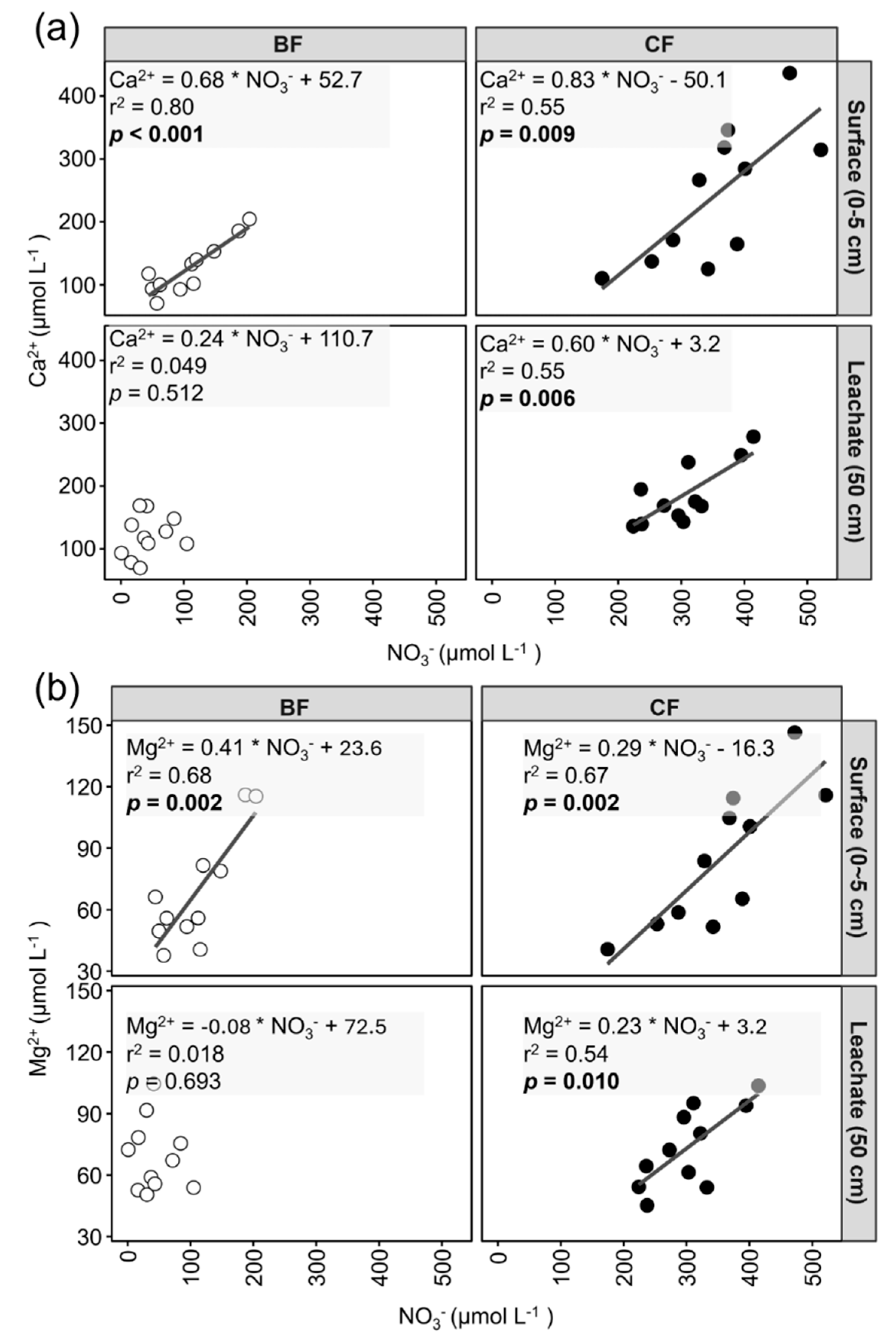

3.3. Correlations Between NO₃⁻ and Major Cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺)

3.4. Anion Deficit Dynamics and Its Correlations with Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanisms Underlying Different Soil Solution Chemistry Between BF and CF

4.2. Differences in Vertical Distribution Patterns for Major Ions Between BF and CF

4.3. Possible Mechanisms for Vertical Differences in Ionic Composition Maintaining Charge Balance (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, NO₃⁻, Anion Deficit) Between BF and CF

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Acknowledgements

Competing Interests

References

- Gao, J. Breeding Status and Strategies of Moso Bamboo. In The Moso Bamboo. In The Moso Bamboo Genome; Gao, J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 193–208. ISBN 978-3-030-80836-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Md Tahir, P.; Osman Al-Edrus, S.S.; Uyup, M.K.A. Bamboo Resources, Trade, and Utilisation. In Multifaceted Bamboo: Engineered Products and Other Applications; Md Tahir, P., Lee, S.H., Osman Al-Edrus, S.S., Uyup, M.K.A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-981-19-9327-5. [Google Scholar]

- Buziquia, S.T.; Lopes, P.V.F.; Almeida, A.K.; De Almeida, I.K. Impacts of Bamboo Spreading: A Review. Biodivers Conserv 2019, 28, 3695–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.-F.; Liang, C.-F.; Chen, J.-H.; Li, Y.-C.; Qin, H.; Fuhrmann, J.J. Rapid Bamboo Invasion (Expansion) and Its Effects on Biodiversity and Soil Processes +. Global Ecology and Conservation 2020, 21, e00787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Eziz, A.; Xiao, S.; Fang, W.; Cai, Q.; Ma, S.; Zhu, J.; Yang, Q.; Hu, J.; Tang, Z.; et al. Effects of Bamboo Invasion on Forest Structures and Diameter–Height Allometries. Forest Ecosystems 2025, 12, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isagi, Y.; Torii, A. Range Expansion and Its Mechanisms in a Naturalized Bamboo Species, Phyllostachys Pubescens, in Japan. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 1997, 6, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhou, G.; Du, H.; Lu, D.; Mo, L.; Xu, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, Y. Current and Potential Carbon Stocks in Moso Bamboo Forests in China. Journal of Environmental Management 2015, 156, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamada, M. Satoyama Landscape of Japan—Past, Present, and Future. In Landscape Ecology for Sustainable Society; Hong, S.-K., Nakagoshi, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 87–109. ISBN 978-3-319-74328-8. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, S. Chronological Location Analyses of Giant Bamboo (Phyllostachys Pubescens) Groves and Their Invasive Expansion in a Satoyama Landscape Area, Western Japan. Plant Species Biology 2015, 30, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, T., Shibata, S., Hasegawa, H., & Itoh, K. Trends and issues of landscape ecological studies on range expansion of bamboo forests in Japan—perspective for sustainable use of bamboo forests—. Jpn. J. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 25:119–135. [CrossRef]

- Shimono, K.; Katayama, A.; Kume, T.; Enoki, T.; Chiwa, M.; Hishi, T. Differences in Net Primary Production Allocation and Nitrogen Use Efficiency between Moso Bamboo and Japanese Cedar Forests along a Slope. Journal of Forest Research 2022, 27, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Ouyang, M.; Yang, Q.; Lu, H.; Yang, G.; Chen, F.; Shi, J.-M. Degradation of Litter Quality and Decline of Soil Nitrogen Mineralization after Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys Pubscens) Expansion to Neighboring Broadleaved Forest in Subtropical China. Plant Soil 2016, 404, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, T.-M.; Lee, J.-S. Comparing Aboveground Carbon Sequestration between Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys Heterocycla) and China Fir (Cunninghamia Lanceolata) Forests Based on the Allometric Model. Forest Ecology and Management 2011, 261, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, K.; Fan, L.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, L.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Lin, H.; Hu, R. High Nutrient Utilization and Resorption Efficiency Promote Bamboo Expansion and Invasion. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 362, 121370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Su, W.; Fan, S.; Chu, H. Effects of Intensive Management Practices on Rhizosphere Soil Properties, Root Growth, and Nutrient Uptake in Moso Bamboo Plantations in Subtropical China. Forest Ecology and Management 2021, 493, 119083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Chiwa, M. Contrasting Nitrate Leaching from an Abandoned Moso Bamboo Forest and a Japanese Cedar Plantation: Role of Vegetation in Mitigating Nitrate Leaching. Plant Soil 2023, 492, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Lu, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Yang, G.; Yang, Q. Accessing the Impacts of Bamboo Expansion on NPP and N Cycling in Evergreen Broadleaved Forest in Subtropical China. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 40383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, P.; Luo, J.; She, C.; Guo, X.; Yuan, J.; Sun, Y.; Guo, R.; Li, Z.; et al. Unveiling the Impacts Moso Bamboo Invasion on Litter and Soil Properties: A Meta-Analysis. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 909, 168532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smethurst, P.J. Soil Solution and Other Soil Analyses as Indicators of Nutrient Supply: A Review. Forest Ecology and Management 2000, 138, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichihashi, R.; Komatsu, H.; Kume, T.; Onozawa, Y.; Shinohara, Y.; Tsuruta, K.; Otsuki, K. Stand-Scale Transpiration of Two Moso Bamboo Stands with Different Culm Densities. Ecohydrology 2015, 8, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Li, Y.; Ouyang, X.; Wang, B.; Ge, X.; Tang, L. Bamboo Plantation Establishment Changes Rainfall Partitioning and Chemistry. Ecosystems 2023, 26, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiwa, M.; Onozawa, Y.; Otsuki, K. Hydrochemical Characteristics of Throughfall and Stemflow in a Moso-Bamboo (Phyllostachys Pubescens) Forest. Hydrological Processes 2010, 24, 2924–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, X.; Liao, K. Comparing the Variations and Controlling Factors of Soil N2O Emissions and NO3–-N Leaching on Tea and Bamboo Hillslopes. CATENA 2020, 188, 104463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adsorption of Dissolved Nitrogen by Forest Mineral Soils Available online:. Available online: https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/abs/10.1139/x09-147 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Chiwa, M.; Tateno ,Ryunosuke; Hishi ,Takuo; and Shibata, H. Nitrate Leaching from Japanese Temperate Forest Ecosystems in Response to Elevated Atmospheric N Deposition. Journal of Forest Research 2019, 24, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, P.; Schmidt, I.K.; Raulund-Rasmussen, K. Leaching of Nitrate from Temperate Forests Effects of Air Pollution and Forest Management. Environ. Rev. 2006, 14, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, T.; Shin, K.-C.; Saitoh, Y.; Nakano, T.; Hiura, T. The Effects of Differences in Vegetation on Calcium Dynamics in Headwater Streams. Ecosystems 2018, 21, 1390–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aber, J.; McDowell, W.; Nadelhoffer, K.; Magill, A.; Berntson, G.; Kamakea, M.; McNulty, S.; Currie, W.; Rustad, L.; Fernandez, I. Nitrogen Saturation in Temperate Forest Ecosystems: Hypotheses Revisited. BioScience 1998, 48, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen-Thorn, A.; Callesen, I.; Armolaitis, K.; Nihlgård, B. The Impact of Six European Tree Species on the Chemistry of Mineral Topsoil in Forest Plantations on Former Agricultural Land. Forest Ecology and Management 2004, 195, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, B.W.; Hansen, H.C.B.; Borggaard, O.K.; Andersen, M.K.; Raulund-Rasmussen, K. Composition and Reactivity of DOC in Forest Floor Soil Solutions in Relation to Tree Species and Soil Type. Biogeochemistry 2001, 56, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legout, A.; van der Heijden, G.; Jaffrain, J.; Boudot, J.-P.; Ranger, J. Tree Species Effects on Solution Chemistry and Major Element Fluxes: A Case Study in the Morvan (Breuil, France). Forest Ecology and Management 2016, 378, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, T.; Niwa, S.; Hiura, T. Calcium Concentration in Leaf Litter Affects the Abundance and Survival of Crustaceans in Streams Draining Warm–Temperate Forests. Freshwater Biology 2014, 59, 748–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, T.; Hiura, T. Root Exudation of Low-Molecular-Mass-Organic Acids by Six Tree Species Alters the Dynamics of Calcium and Magnesium in Soil. Can. J. Soil. Sci. 2016, 96, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, D.V.; Hennon, P.E.; Schaberg, P.G.; Hawley, G.J. Adaptation to Exploit Nitrate in Surface Soils Predisposes Yellow-Cedar to Climate-Induced Decline While Enhancing the Survival of Western Redcedar: A New Hypothesis. Forest Ecology and Management 2009, 258, 2261–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chiwa, M. Influence of Surface Soil Chemistry on Nutrient Leaching from Japanese Cedar Plantations and Natural Forests. Landscape Ecol Eng 2024, 20, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Space-for-Time Substitution as an Alternative to Long-Term Studies. In Long-Term Studies in Ecology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 1989; pp. 110–135 ISBN 978-1-4615-7360-9.

- Dijkstra, F.A.; Van Breemen, N.; Jongmans, A.G.; Davies, G.R.; Likens, G.E. Calcium Weathering in Forested Soils and the Effect of Different Tree Species. Biogeochemistry 2003, 62, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiwa, M. Long-Term Changes in Atmospheric Nitrogen Deposition and Stream Water Nitrate Leaching from Forested Watersheds in Western Japan. Environmental Pollution 2021, 287, 117634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, Y.; Misumi, Y.; Kubota, T.; Nanko, K. Characteristics of Soil Erosion in a Moso-Bamboo Forest of Western Japan: Comparison with a Broadleaved Forest and a Coniferous Forest. CATENA 2019, 172, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2024). _R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- Asiedu, D.K.; Suzuki, S.; Shibata, T. Provenance of Sandstones from the Lower Cretaceous Sasayama Group, Inner Zone of Southwest Japan. Sedimentary Geology 2000, 131, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, A.; Shibata, H.; Inokura, Y.; Nakao, T.; Toda, H.; Satoh, F.; Sasa, K. Chemical Characteristics in Stemflow of Japanese Cedar in Japan. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2001, 130, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Tsunogai, U.; Nakagawa, F.; Sambuichi, T.; Chiwa, M.; Kasahara, T.; Shinozuka, K. Stable Isotopic Evidence for the Excess Leaching of Unprocessed Atmospheric Nitrate from Forested Catchments under High Nitrogen Saturation. Biogeosciences 2023, 20, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Fukuzawa, K.; Nakayama, M.; Tateno, R.; Hishi, T.; Shibata, H.; Chiwa, M. Nitrate Leaching and Its Susceptibility in Response to Elevated Nitrogen Deposition in Japanese Forests. Journal of Forest Research 2024, 29, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobbágy, E.G.; Jackson, R.B. The Distribution of Soil Nutrients with Depth: Global Patterns and the Imprint of Plants. Biogeochemistry 2001, 53, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, T.H.; Xincheng, X.; Shakoor, A.; Rashid, M.H.U.; Bashir, M.F.; Nawaz, M.F.; Kumar, U.; Shahzad, S.M.; Yan, W. Spatial Distribution of Carbon Dynamics and Nutrient Enrichment Capacity in Different Layers and Tree Tissues of Castanopsis Eyeri Natural Forest Ecosystem. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022, 29, 10250–10262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Zu, Y. Temporal Changes in SOM, N, P, K, and Their Stoichiometric Ratios during Reforestation in China and Interactions with Soil Depths: Importance of Deep-Layer Soil and Management Implications. Forest Ecology and Management 2014, 325, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Xia, M.; Tang, X.; Fan, S. Spatial Variability of Soil Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium Contents in Moso Bamboo Forests in Yong’an City, China. CATENA 2017, 150, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, Y.; Sakai, H.; Shinomiya, Y.; Yoshinaga, S.; Torii, A.; Yamada, T.; Noguchi, K.; Morishita, T.; Fujii, K. Effects of Climate and Acidic Deposition on Interannual Variations of Stream Water Chemistry in Forested Watersheds in the Shimanto River Basin, Southern Japan. Ecological Research 2025, 40, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urakawa, R.; Toda, H.; Cao, Y. Long-term Changes in Stream Water Chemistry in Small Forested Watersheds in the Northern Kanto Region. Ecological Research 2025, 40, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, P.H. Changes of pH across the Rhizosphere Induced by Roots. Plant Soil 1981, 61, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassirirad, H. Kinetics of Nutrient Uptake by Roots: Responses to Global Change. New Phytologist 2000, 147, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Song, X.; Chang, S.X.; Peng, C.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Nitrogen Depositions Increase Soil Respiration and Decrease Temperature Sensitivity in a Moso Bamboo Forest. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2019, 268, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Tang, C.; Zhang, S.; Fu, S.; Jiang, P.; Ge, T.; Luo, Y.; Song, X.; et al. Rates of Soil Respiration Components in Response to Inorganic and Organic Fertilizers in an Intensively-Managed Moso Bamboo Forest. Geoderma 2021, 403, 115212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BF | CF | |

| Stem density (No. ha-1) | 6900 | 1020 |

| Stem diameter (cm) | 8.6 | 34.1 |

| Plant height (m) (m) |

10.9 | 23.6 |

| Soil pH (H2O) | 5.33 | 5.47 |

| Soil solution pH (5 cm depth) | 6.08 | 6.32 |

| Soil solution pH (50 cm depth ) | 7.05 | 6.82 |

| Surface | Leachate | p | |

| BF | |||

| Na+ | 200.9 | 210.1 | 0.336 |

| NH4+ | 24.5 | 7.0 | <0.001 |

| K+ | 80.6 | 16.7 | <0.001 |

| Ca2+ | 128.1 | 126.0 | 0.773 |

| Mg2+ | 69.1 | 69.2 | 0.706 |

| Cl- | 284.7 | 214.1 | 0.186 |

| NO3- | 110.3 | 47.5 | 0.030 |

| SO42- | 56.2 | 50.1 | 0.259 |

| CF | |||

| Na+ | 233.2 | 207.4 | 0.044 |

| NH4+ | 6.8 | 1.7 | 0.008 |

| K+ | 50.0 | 15.4 | <0.001 |

| Ca2+ | 257.6 | 189.8 | <0.001 |

| Mg2+ | 88.7 | 75.7 | 0.045 |

| Cl- | 383.9 | 264.4 | <0.001 |

| NO3- | 354.1 | 305.6 | 0.036 |

| SO42- | 47.5 | 50.9 | 0.394 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).