Submitted:

14 October 2024

Posted:

15 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

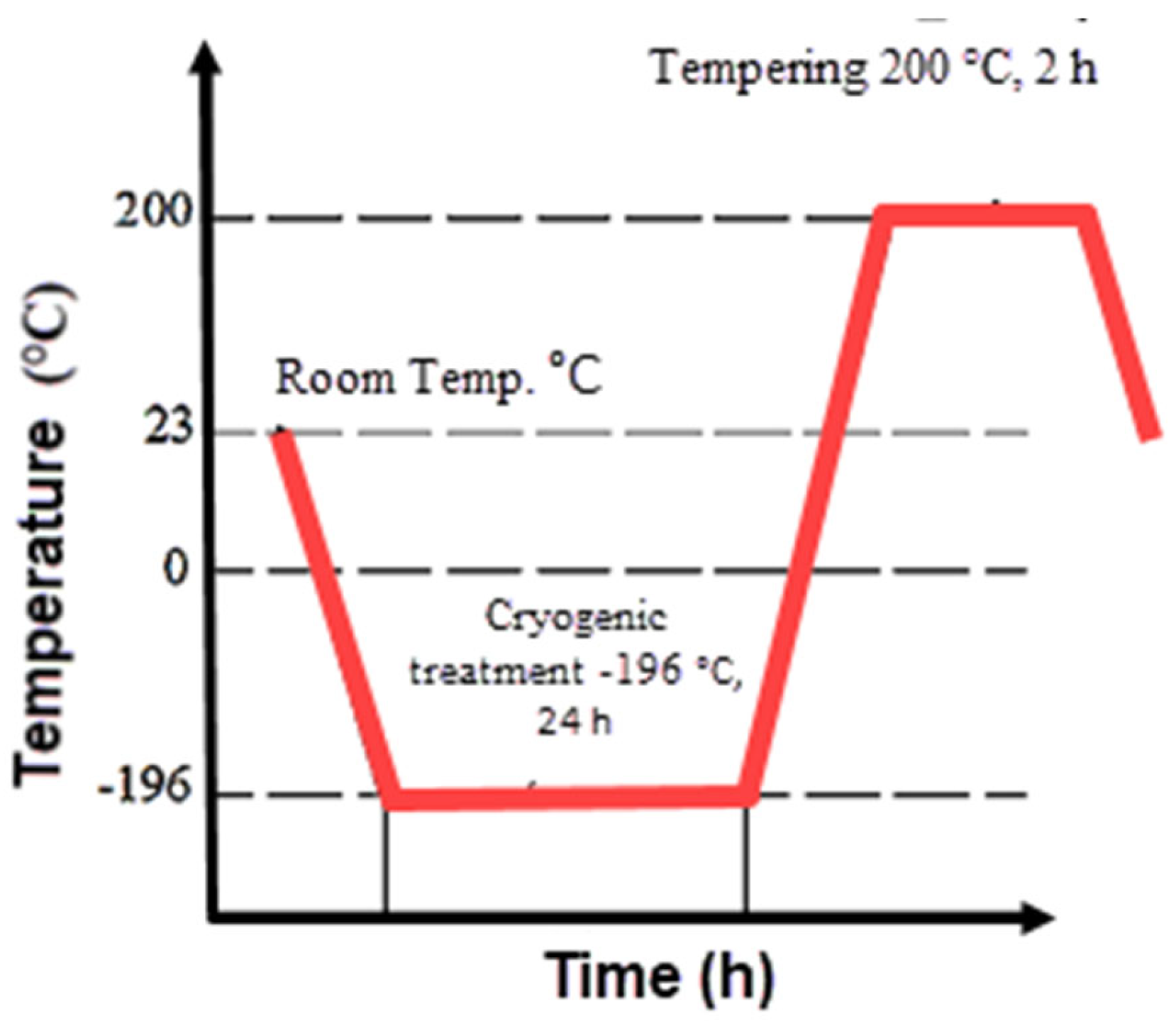

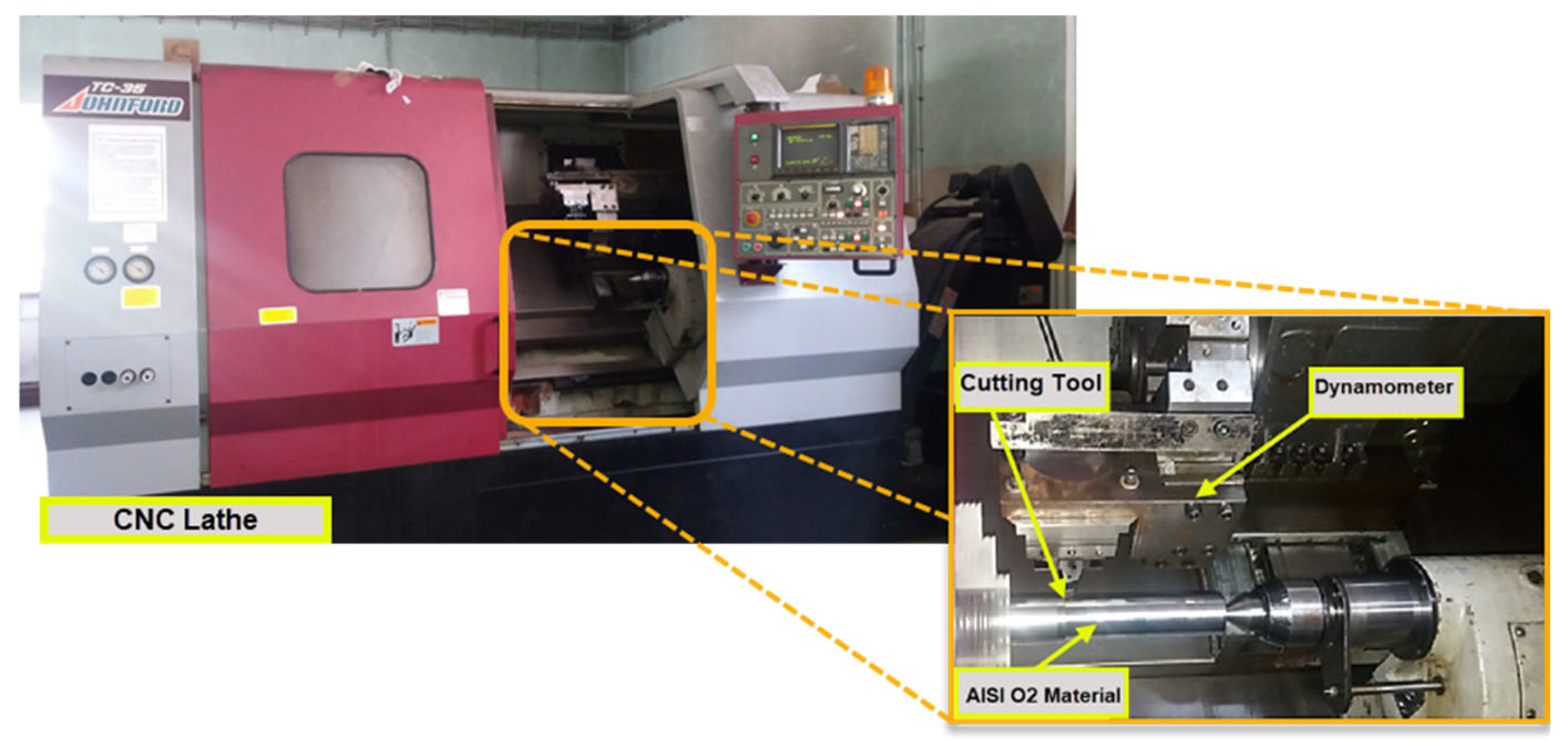

2. Materials and Methods

3. RSM Optimization

4. Effect of Cryogenic Treatment on Tool Wear

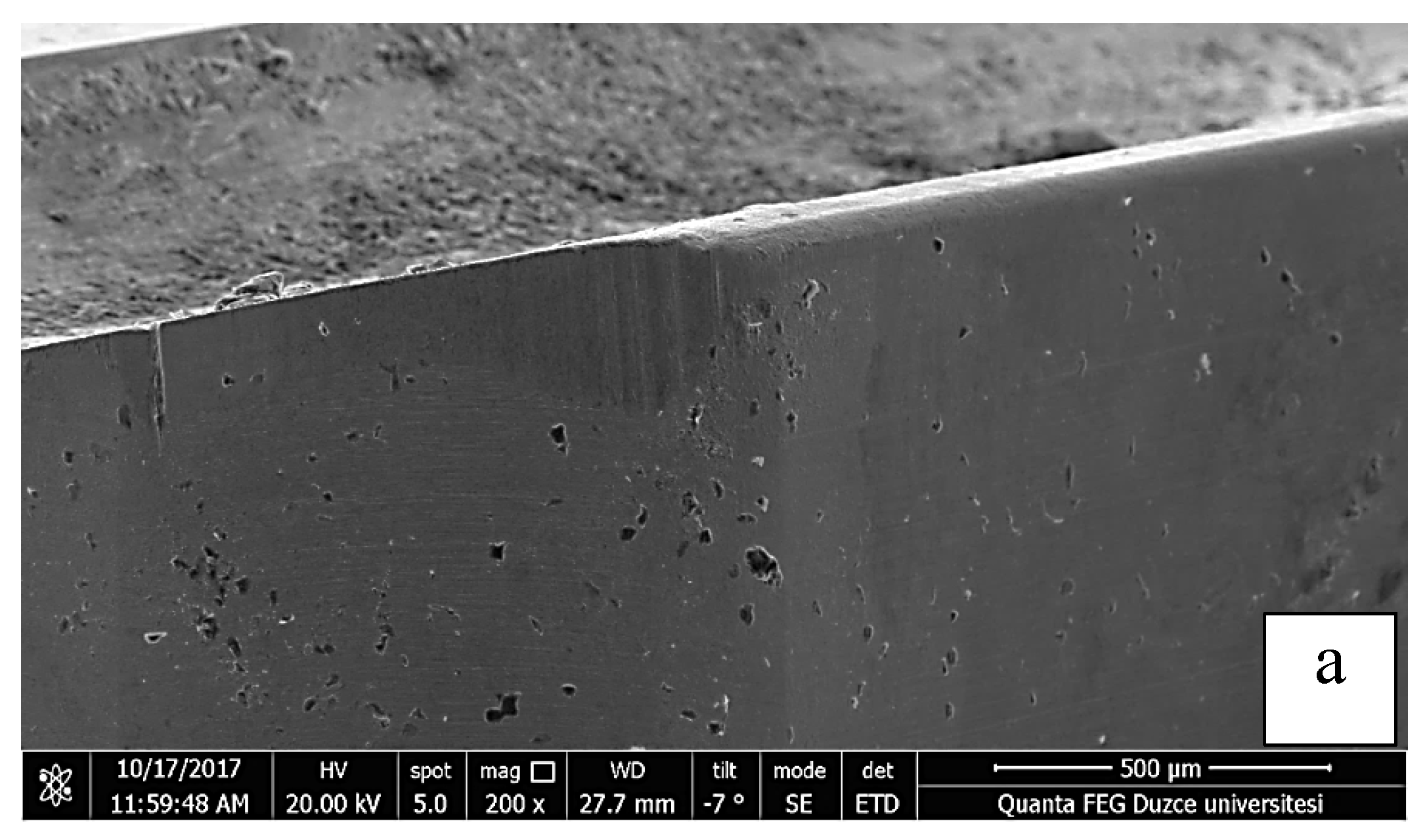

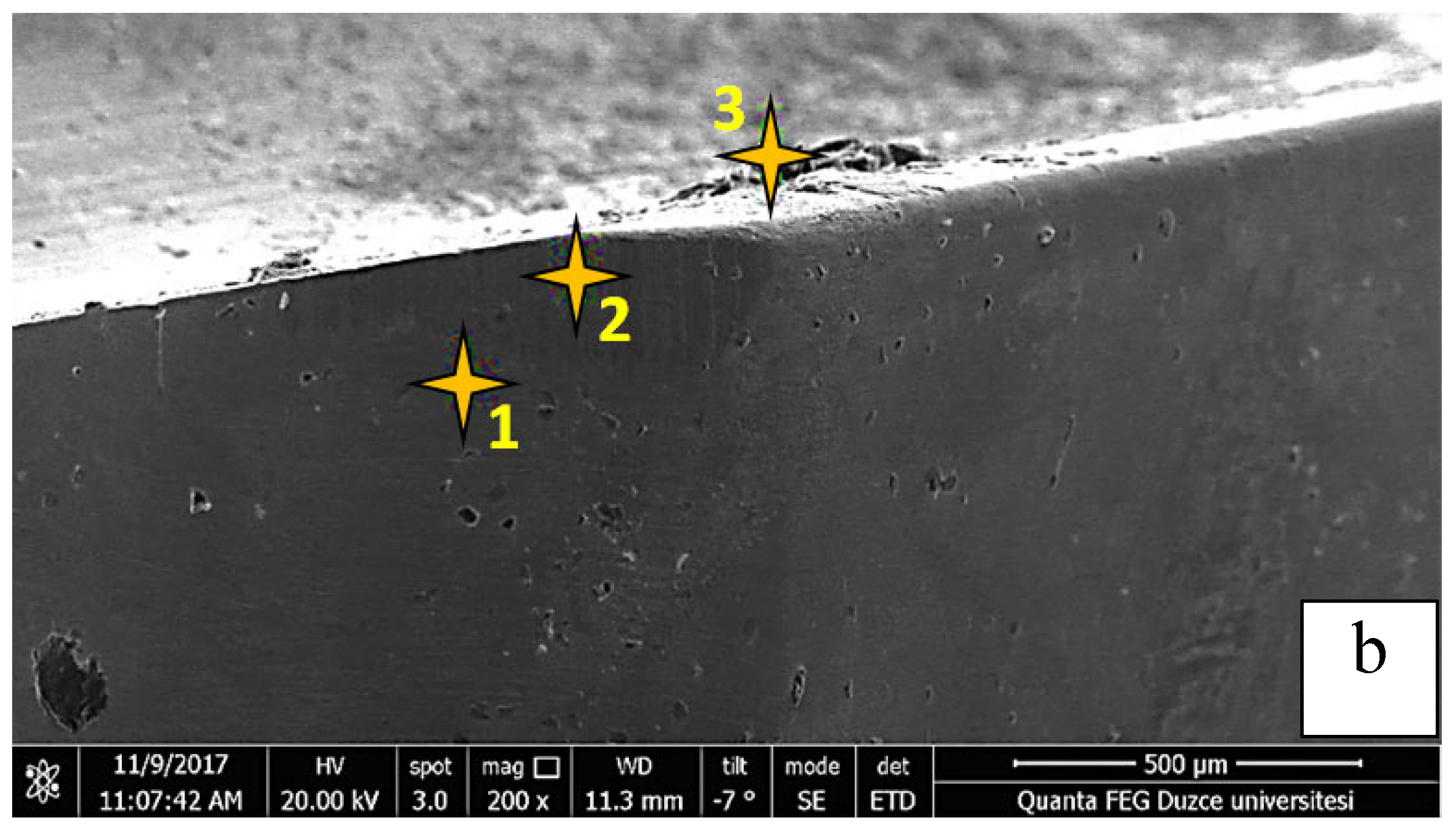

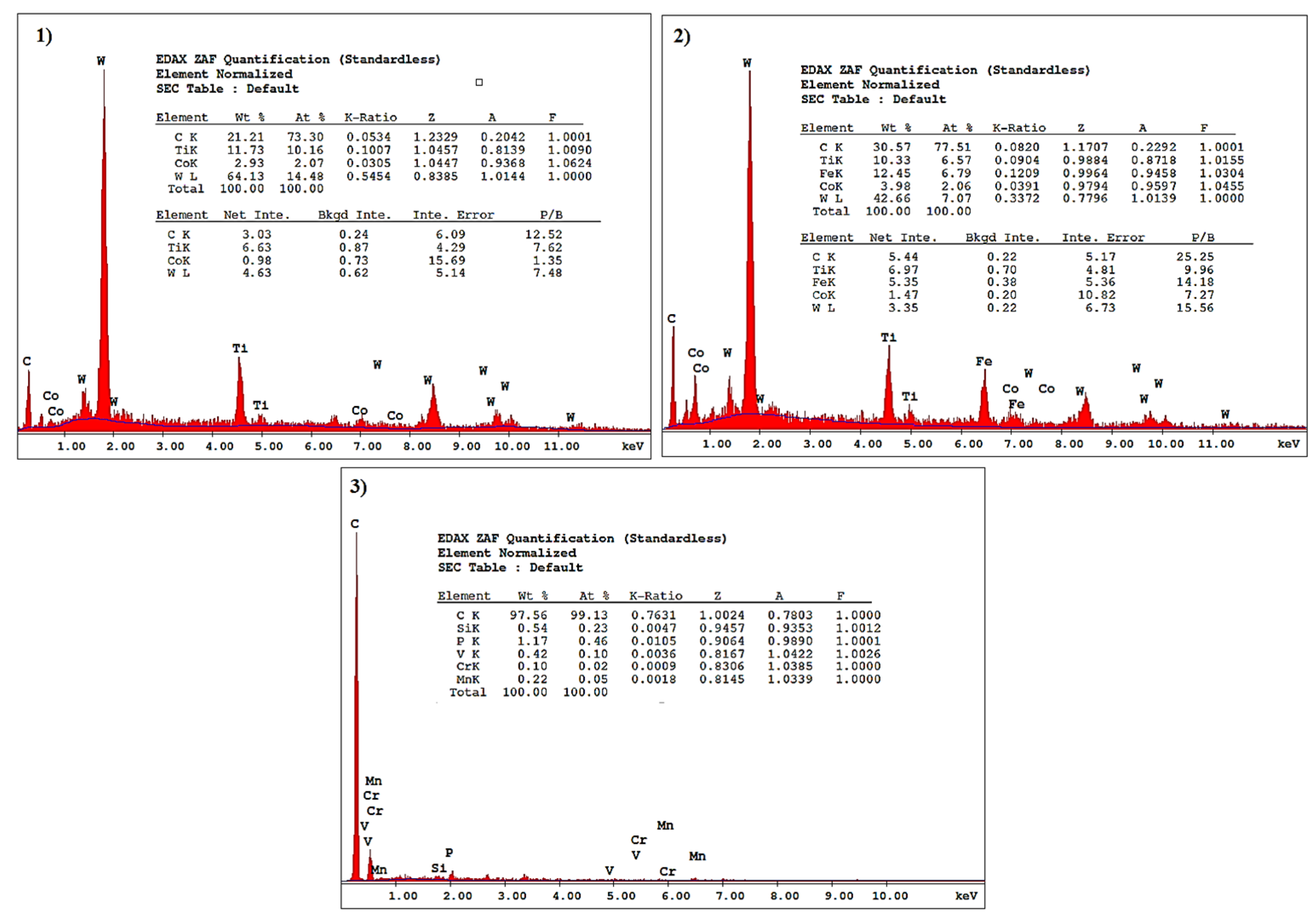

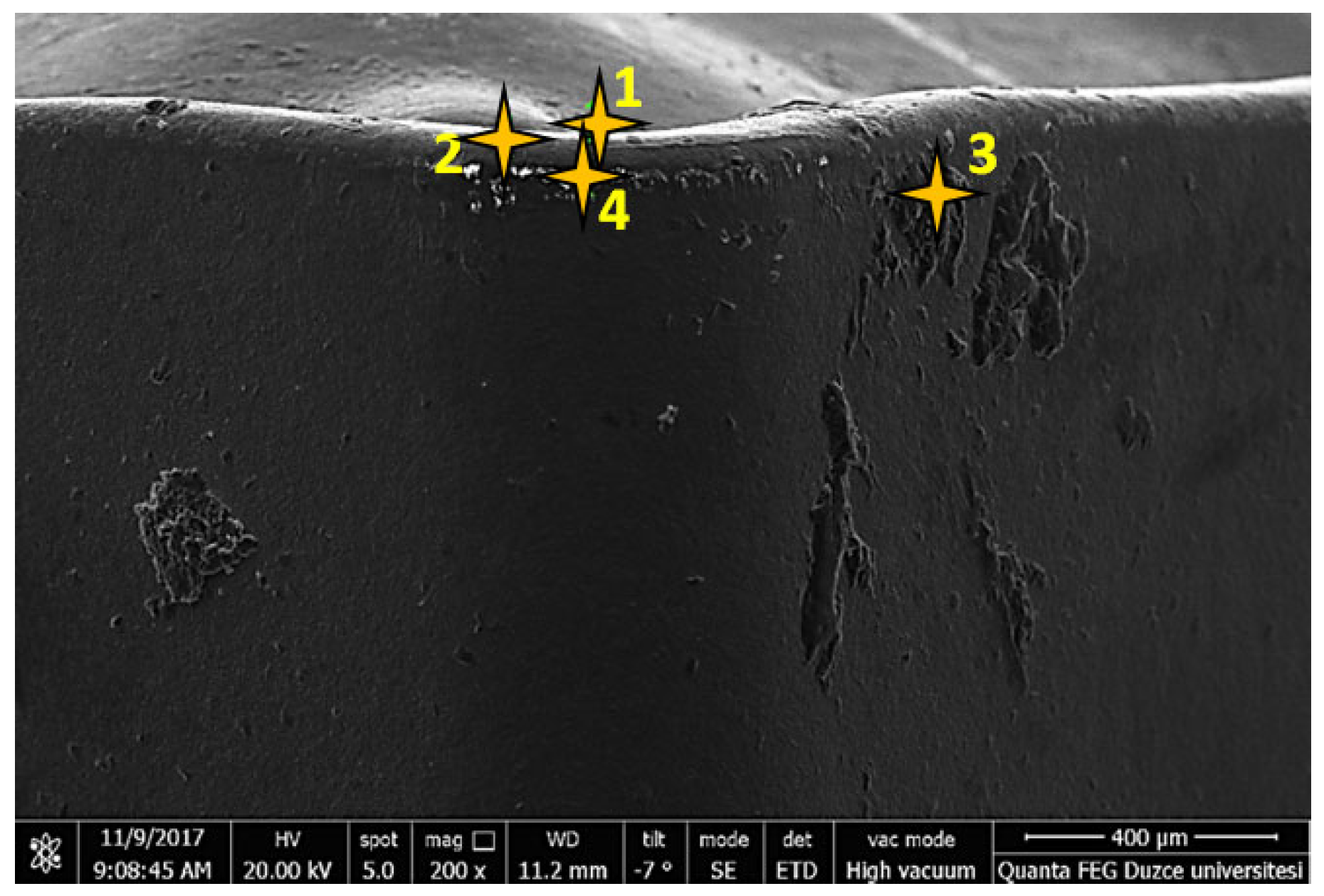

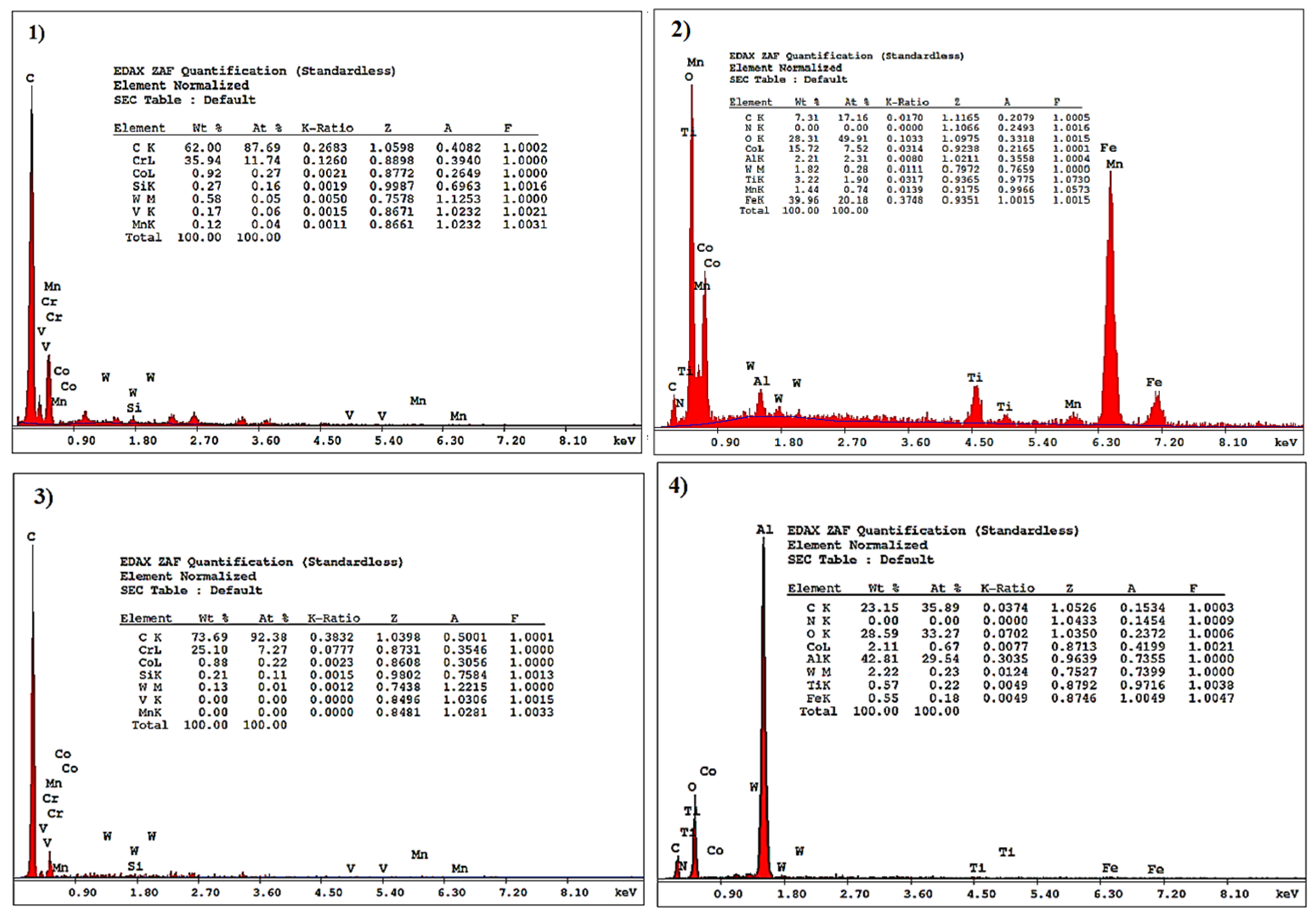

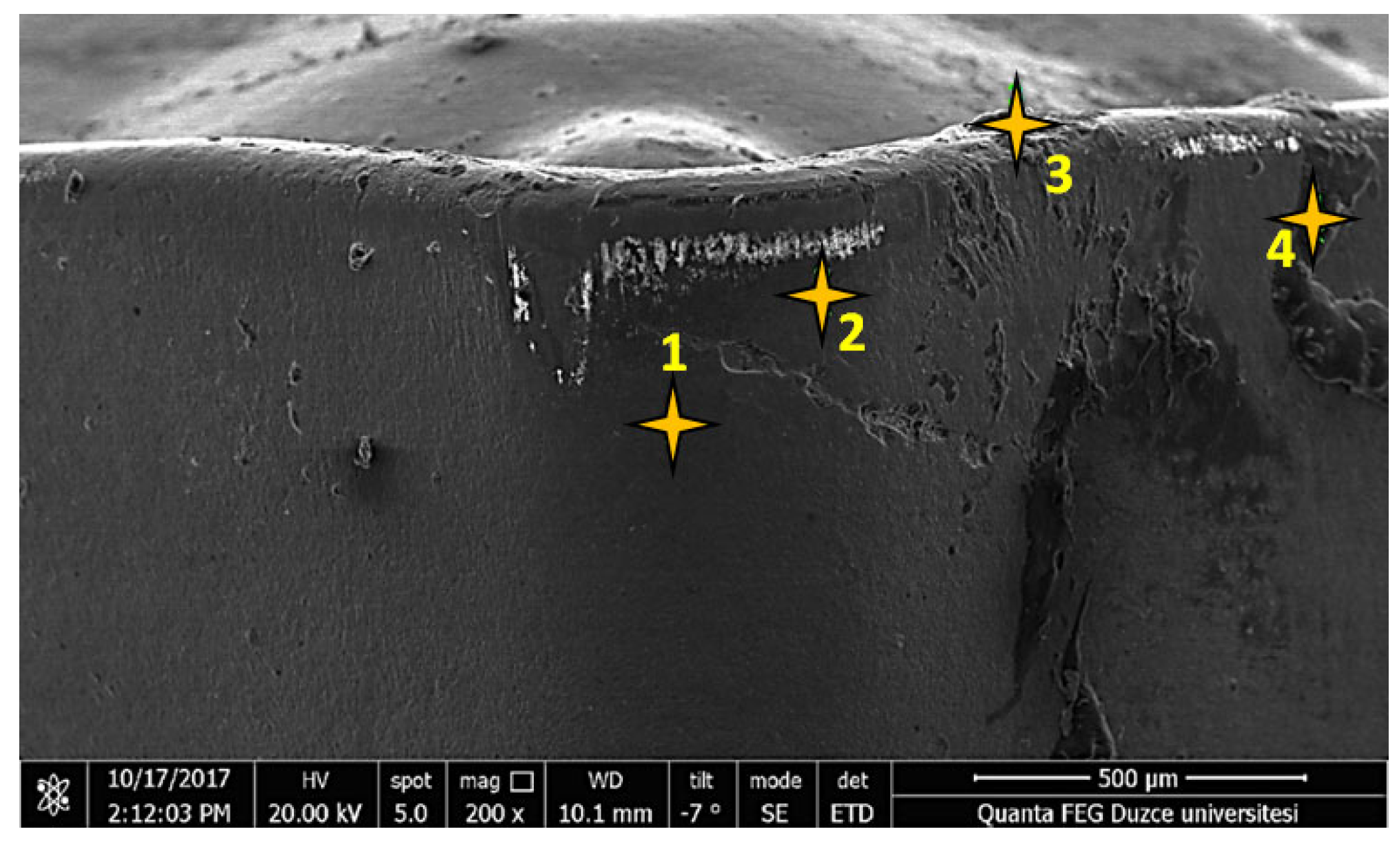

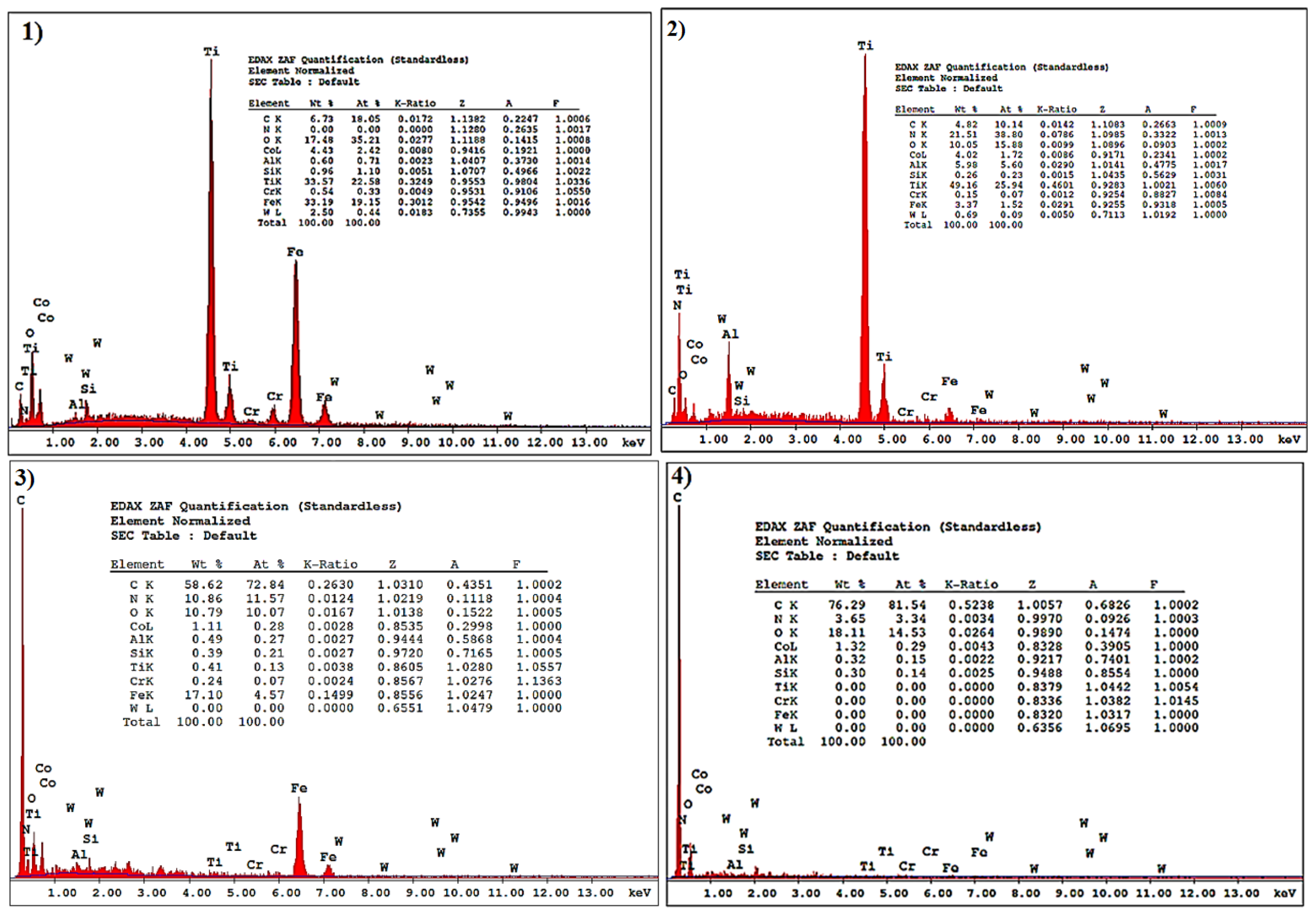

4.1. SEM and EDX Analyses

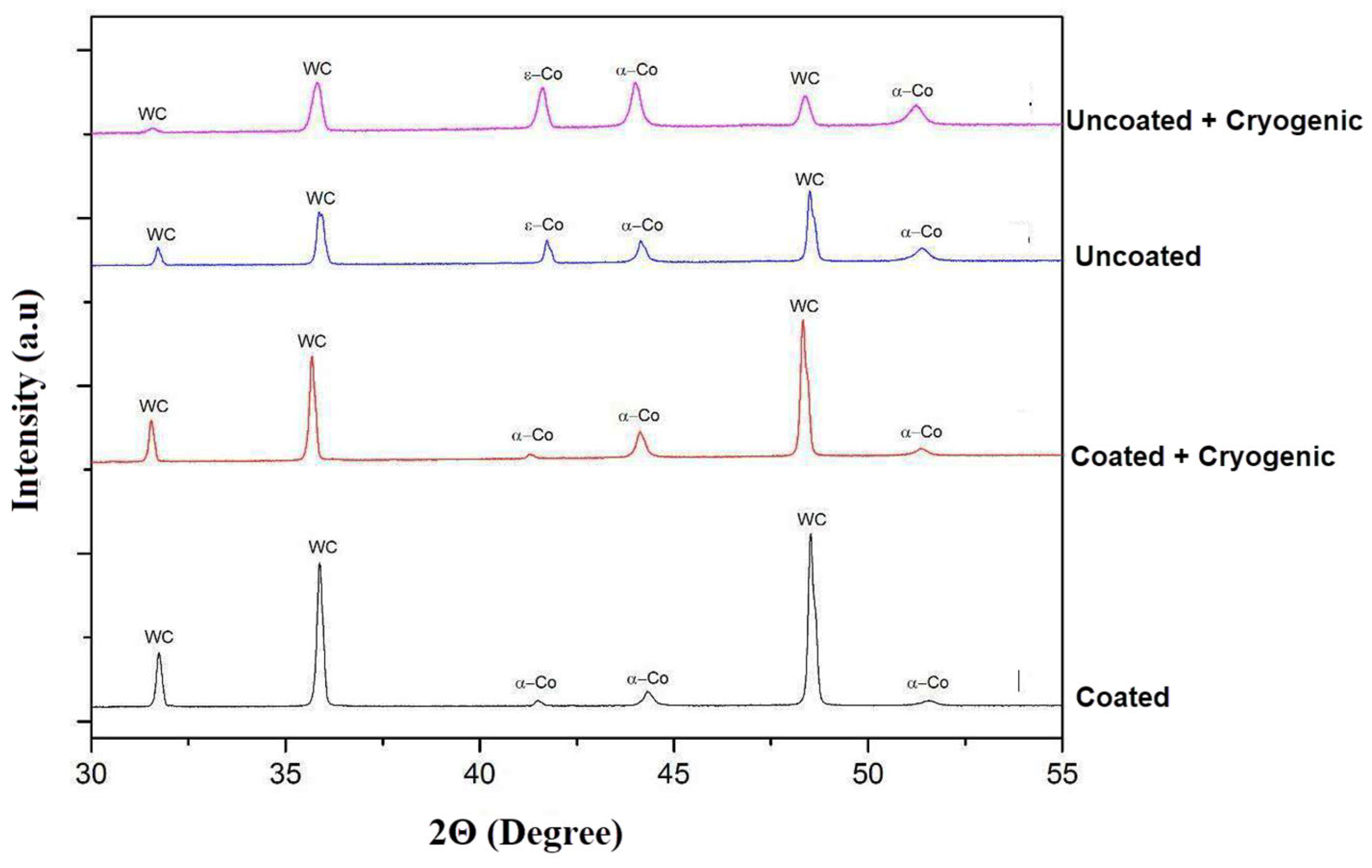

4.2. Rietveld Analysis

4.3. Hardness Analysis

5. Conclusions

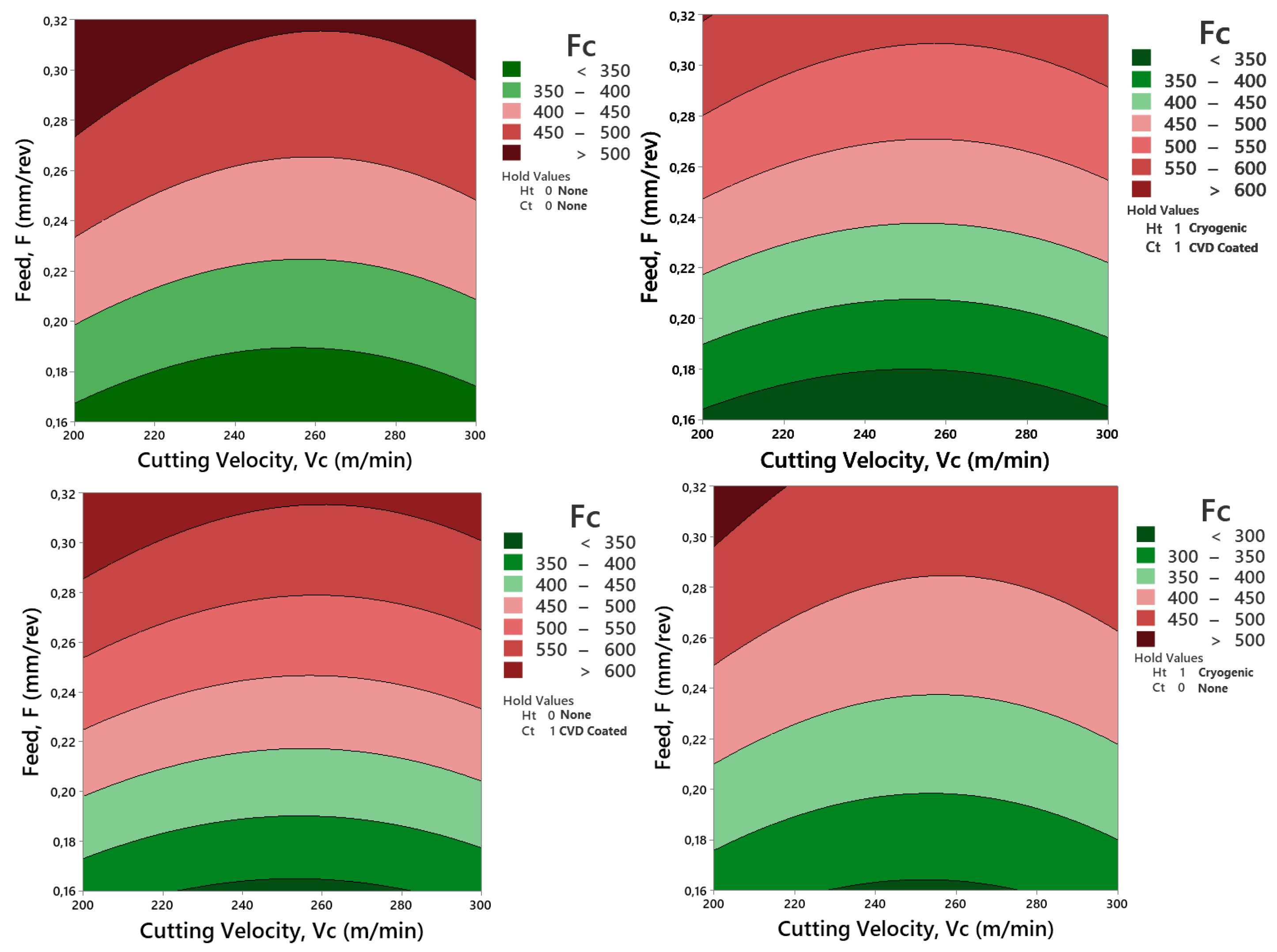

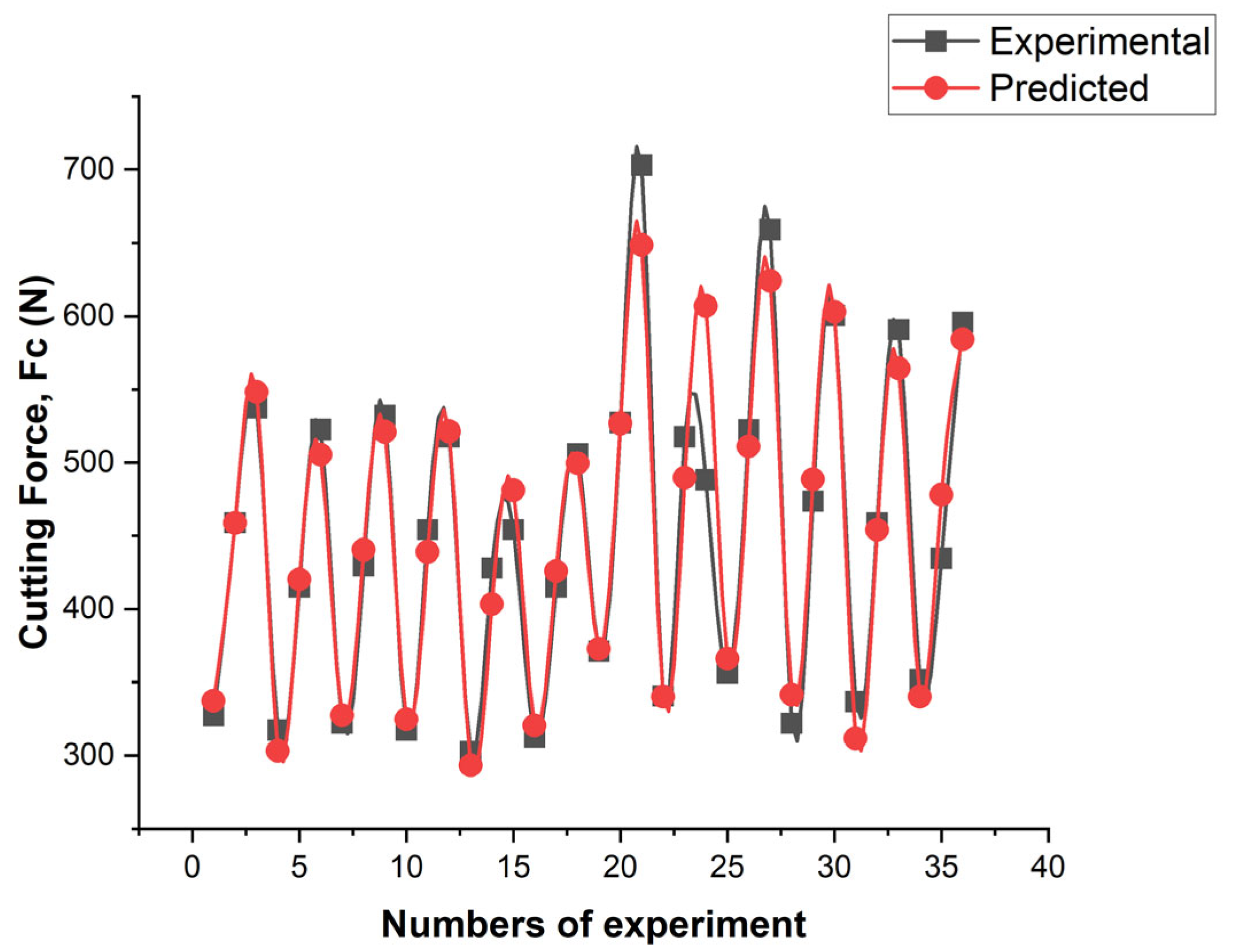

- It was determined that the most influential parameter on Fc was feed (F), with 78.89%. Ct, which was in second place, affected the Fc output parameter with 8.25%. The effect of the Ht and Vc parameters was minimal. The success of the numerical model created to estimate Fc was 93.28%.

- It has been determined that Fc increases dramatically with the increase of F, which is valid for all heat treatment and coating types. In addition, it is possible to say that Fc increases up to approximately 250 m/min with the increase of cutting speed (Vc) and then tends to decrease.

- The lowest optimized Fc value with the RSM method was determined as 339.99 N. In order to obtain this value, Vc should be selected as 252.525 m/min and F 0.16 mm/rev. In addition, a cutting tool without cryogenic heat treatment and with CVD coating should be preferred for optimum Fc.

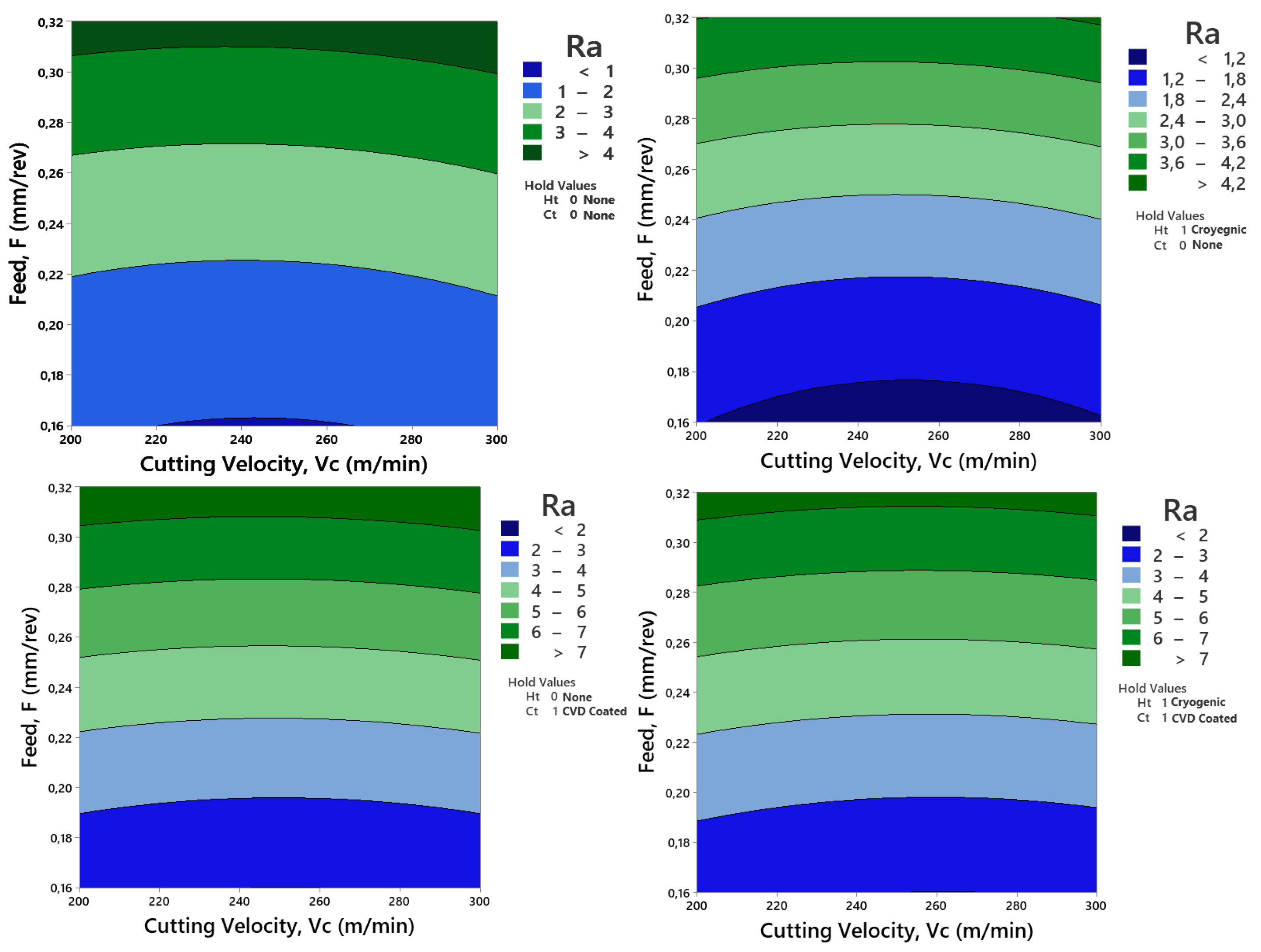

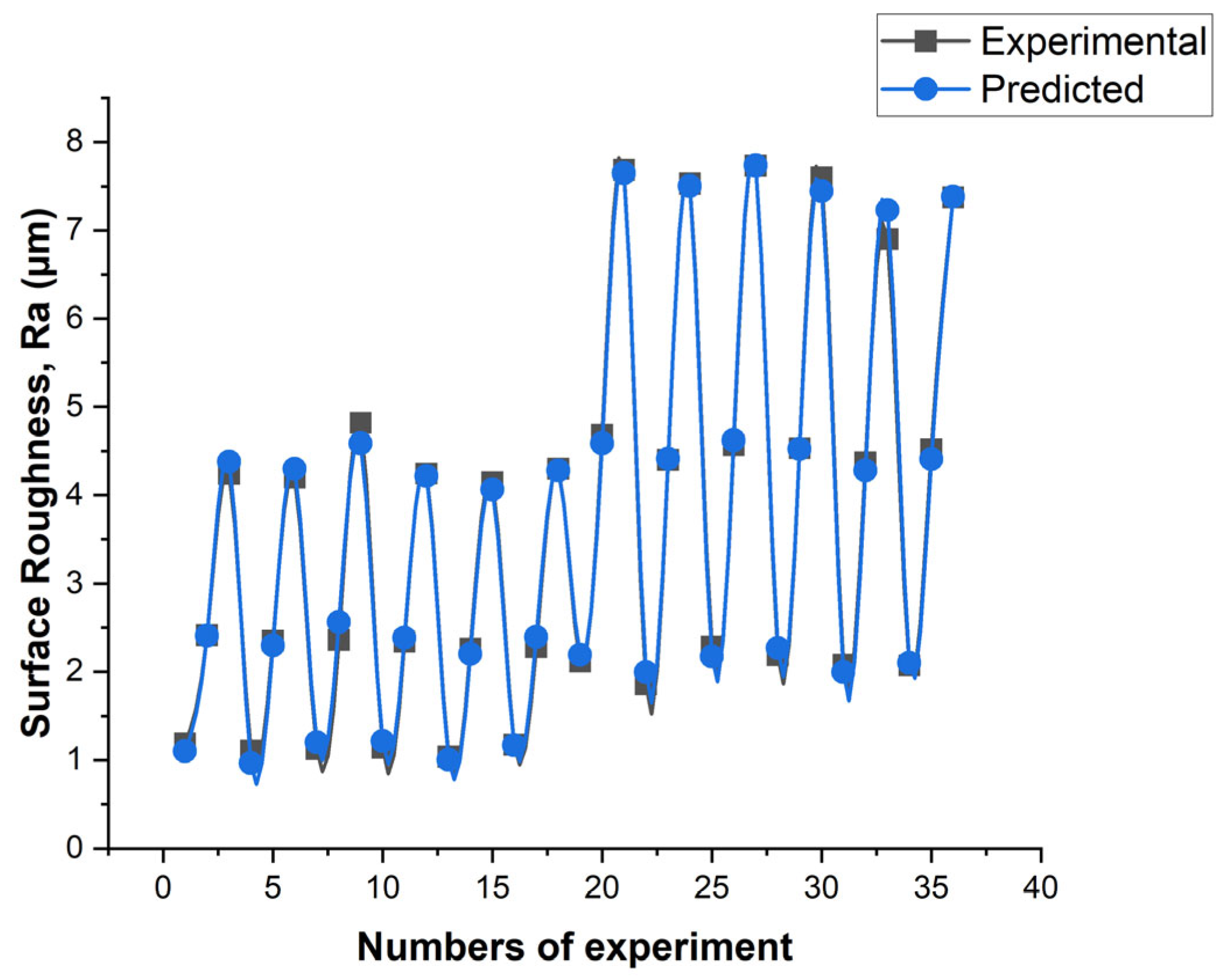

- It was found that the most influential parameter on Ra was F, with a rate of 69.38%. The second parameter is Ct, with a rate of 24.97%. Since the effect of Vc and Ht is below 1%, no interaction can be mentioned. The success of the numerical prediction model is exceptionally high and has been realized at a rate of 99.74%.

- It was determined that Ra increased significantly with increasing feed rate, which is valid for both heat treatment and coating cases. In addition, it was determined that Ra increased slightly with increasing Vc and then tended to decrease again.

- The smallest Ra value optimized with the RSM method was determined as 1.04 µm. To obtain this value, Vc 243.434 m/min and F 0.16 mm/rev should be selected. In addition, a cutting tool without cryogenic heat treatment and coating is also needed for optimum Ra.

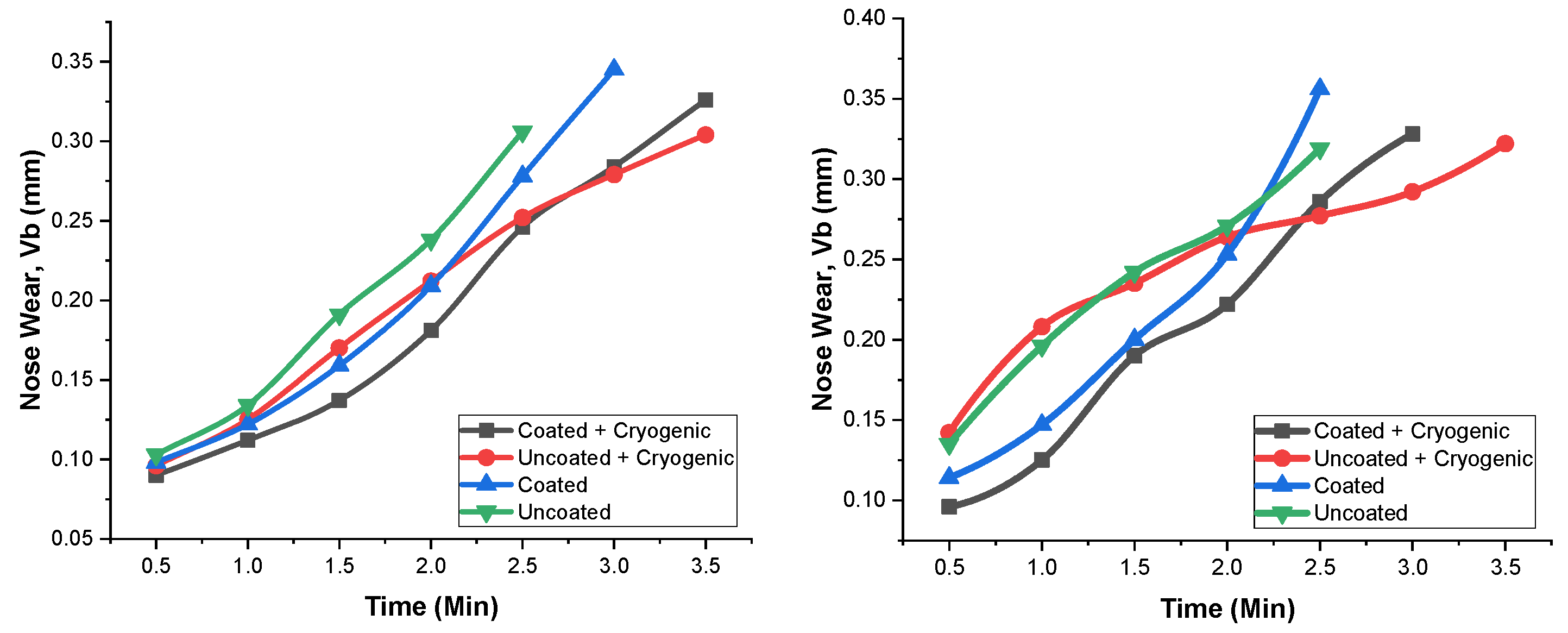

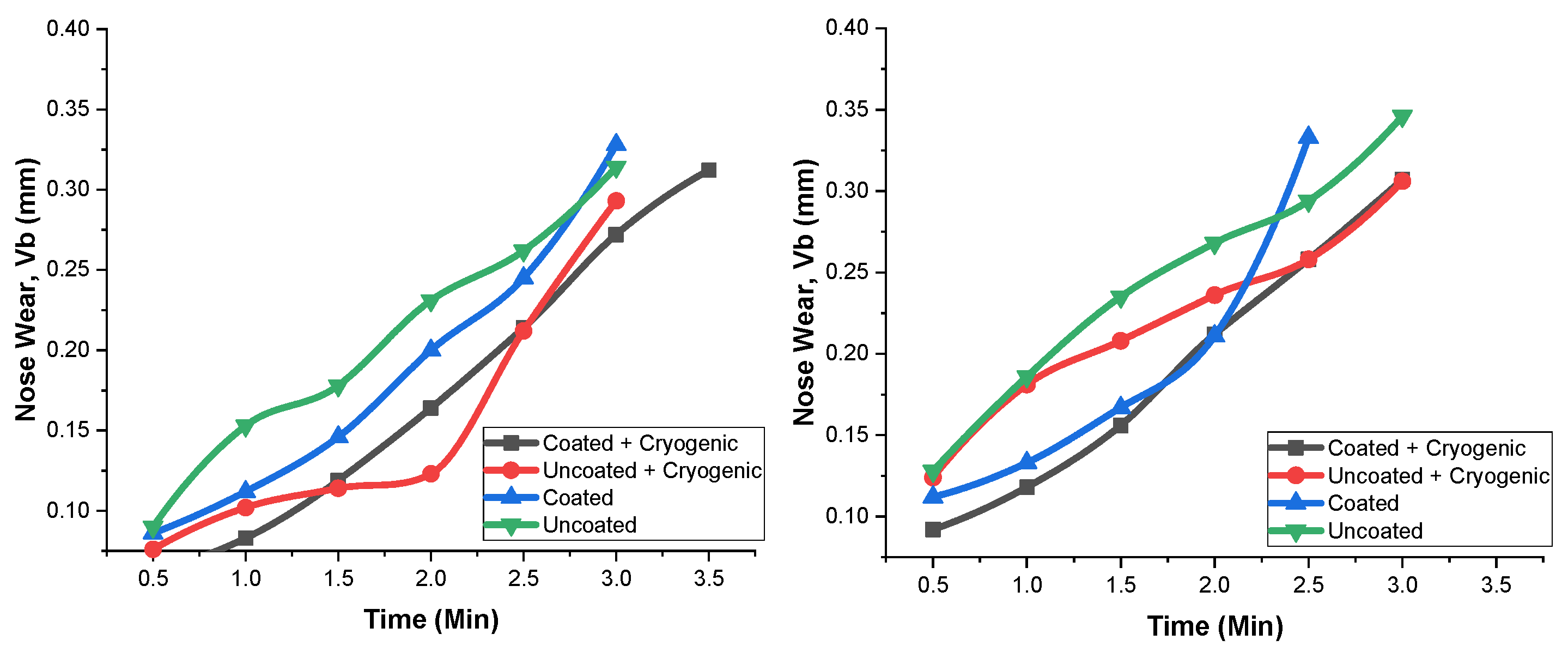

- The best tool life results were seen in coated and uncoated cryogenically treated tools in the operations performed at 200 m/min cutting speed and 0.08 mm/rev feed rate. In light of the data, cryogenically treated tools provided a minimum 16% life increase compared to the others. After the operations performed at the same cutting speed and 0.16 mm/rev feed rate, cryogenically treated coated and uncoated tools provided a minimum 20% life increase compared to the others.

- After the operations performed at 250 m/min cutting speed and 0.08 mm/rev feed rate, cryogenically treated coated tools provided a minimum 16% life increase compared to the others. When the feed rate was increased to 0.16 mm/rev, the coated tool with cryogenic treatment, the uncoated tool with cryogenic treatment, and exceptionally, the uncoated tool without cryogenic treatment provided a 20% increase in life compared to the cryogenic treated tool.

- When the SEM images were examined, it was observed that wear was reduced in uncoated cutting tools due to the effect of the cryogenic treatment.

- When the elements detected in the EDX analysis of the uncoated cryogenic treated cutting tool at point 1 were examined, it was seen that the uncoated carbide (WC+Co+TiC+TaC) tool consisted of wolfram (W), carbon (C), cobalt (Co), titanium (Ti) and tantalum (Ta) elements. The elements at point 2 were also similar. However, when the elements at point 3 were examined, it was seen that the elements were C, Co, Cr, Mn, V, P, and Si, which were also found in the microstructure of the AISI O2 cold work tool steel workpiece. This result determined that there was adhesion at this point. It was determined that agglomerate chip formation occurred at the point indicated by 3.

- Agglomerate chip formation occurred at points 1 and 3 in the SEM image of the coated cutting tool that was not cryogenically treated. The elements belonging to the workpiece material were seen at these points as a result of the EDX analysis. Points 2 and 4 contain elements belonging to the coated carbide cutting tool material. A similar situation applies to the coated cutting tool that was cryogenically treated.

- The XRD diagram of the deeply etched cutting tools showed that there was an increase in the carbide peaks after the cryogenic treatment.

- As a result of the Rietveld analyses performed, it was seen that the samples were etched at different rates and, therefore, had different WC ratios. Since the peaks belonging to these phases were seen to be of sufficient intensity from the obtained XRD diagrams, the deep etching process was not repeated. It is seen that the ratios of α-Co and Ɛ-Co carbides increased significantly after the cryogenic treatment. These results are similar to literature studies.

- After the cryogenic treatment was applied to the coated cutting tool, the α-Co ratio increased by approximately 71%, and the Ɛ-Co ratio increased by 31%.

- After the cryogenic treatment was applied to the uncoated cutting tool, the α-Co increased by approximately 30%, and the Ɛ-Co increased by approximately 50%.

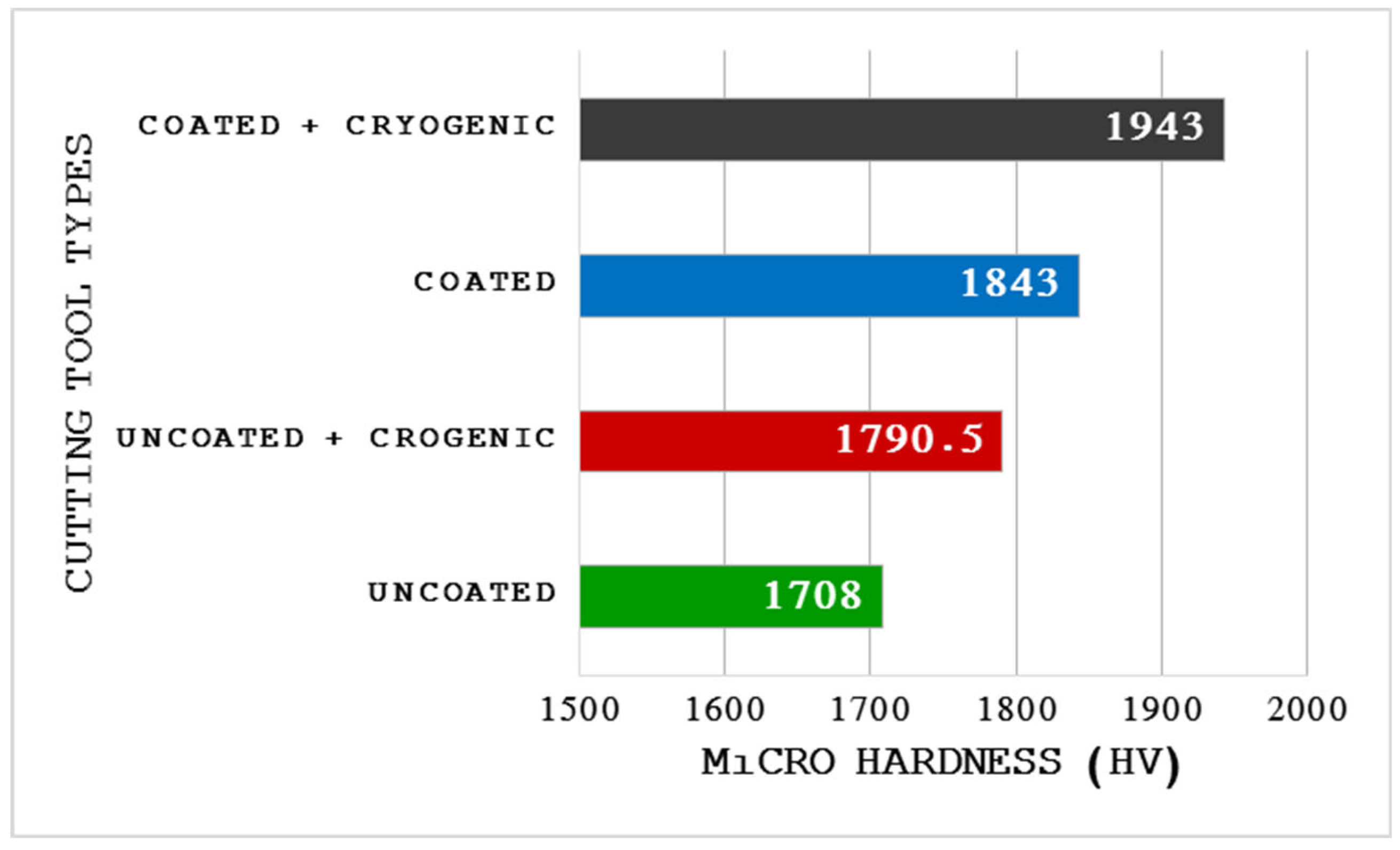

- While the hardness value of the uncoated carbide tool before the cryogenic treatment was 1708 HV, it increased by 4.8% after the cryogenic treatment and became 1790.5 HV. In the coated carbide tool, the hardness value was initially determined as 1843 HV, and this value increased by 5% after the cryogenic treatment and was obtained as 1943 HV.

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baş, M., Ertan, R., & Yavuz, N. (2011). The Analysis of the Effect of the Surface Processing Methods on the Fatigue Behaviour of Cold Working Tool Steel. Uludag University Faculty of Engineering Journal, 16(1).

- Ekinović, S., Dolinšek, S., & Begović, E. (2005). Machinability of 90MnCrV8 steel during high-speed machining. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 162-163, 603–608. [CrossRef]

- Çalışkan, H. Kurbanoğlu, C. Kramar, D. Panjan, P., & Kopac, J. (2012). Hard milling operation of AISI O2 cold work tool steel by carbide tools protected with different hard coatings. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 21-26.

- Huang, J. Y., Zhu, Y. T., Liao, X. Z., Beyerlein, I. J., Bourke, M. A., & Mitchell, T. E. (2003). Microstructure of cryogenic treated M2 tool steel. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 339(1-2), 241–244. [CrossRef]

- Adin, M. Ş. (2024). Machining aerospace aluminium alloy with cryo-treated and untreated HSS cutting tools. Advances in Materials and Processing Technologies, 10(3), 2664-2689. [CrossRef]

- Braic, V., Zoita, C. N., Balaceanu, M., Kiss, A., Vladescu, A., Popescu, A., & Braic, M. (2010). TiAlN/TiAlZrN multilayered hard coatings for enhanced performance of HSS drilling tools. Surface and Coatings Technology, 204(12-13), 1925-1928. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G., Gill, S. S., & Dogra, M. (2017). Techno-economic analysis of blanking punch life improvement by environment friendly cryogenic treatment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 143, 1060–1068. [CrossRef]

- Özbek, N. A., Çİçek, A., Gülesİn, M., & Özbek, O. (2016). Application of deep cryogenic treatment to uncoated tungsten carbide inserts in the turning of AISI 304 stainless steel. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, 47, 6270-6280. [CrossRef]

- Özbek, N. A. (2020). Effects of cryogenic treatment types on the performance of coated tungsten tools in the turning of AISI H11 steel. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 9(4), 9442-9456.

- Isik, Y., (2007). Investigating the machinability of tool steels in turning operations. Materials and Design, vol.28, no.5, 1417-1424. [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, H., Kafkas, F., & Şeker, U., (2011). Experimental Investigation of the Effect of Coatings Applied to Cutting Tools with Different Methods on Cutting Forces and Surface Roughness, 6th International Advanced Technologies Symposium (IATS’11) (pp.27-32). Elazığ, Turkey.

- Asiltürk, İ., Neşeli, S., & İnce, M. A. (2016). Optimisation of parameters affecting surface roughness of Co28Cr6Mo medical material during CNC lathe machining by using the Taguchi and RSM methods. Measurement, 78, 120–128. [CrossRef]

- Uysal, A., & Altan, E. (2016). Slip-line field modelling of rounded-edge cutting tool for orthogonal machining. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture, 230(10), 1925-1941. [CrossRef]

- Chetan, Ghosh, S., & P. Venkateswara Rao. (2017). Performance evaluation of deep cryogenic processed carbide inserts during dry turning of Nimonic 90 aerospace grade alloy. Tribology International, 115, 397–408. [CrossRef]

- Mavi, A. (2013). Effect of cryogenic treatment applied to cutting tools on cutting tool performance in machining of ti6al4v titanium alloy (Doctoral dissertation, Gazi University Institute of Science, Ankara).

- Çiçek, A., Kara, F., Kivak, T., & Ekici, E. (2013). Evaluation of machinability of hardened and cryo-treated AISI H13 hot work tool steel with ceramic inserts. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials, 41, 461–469. [CrossRef]

- K. Vadivel, & R. Rudramoorthy. (2008). Performance analysis of cryogenically treated coated carbide inserts. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 42(3-4), 222–232. [CrossRef]

- Basmacı, G., Kırbaş, İ., Ay, M., Peker, M. (2018). Optimisation and influence of cutting parameters on surface roughness during turning of ASTM b574 (Hastelloy C-22) using a hybrid of Taguchi and RSM methods. Sakarya University Journal of Science, 22(2), 761-771. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Luo, B., Bai, Z., Zhu, B., & Ouyang, S. (2016). Effects of deep cryogenic treatment on the microstructure and properties of WC Fe Ni cemented carbides. International Journal of Refractory Metals & Hard Materials, 58, 42–50. [CrossRef]

- Musfirah, A. H., Ghani, J. A., & Haron, C. H. C. (2017). Tool wear and surface integrity of inconel 718 in dry and cryogenic coolant at high cutting speed. Wear, 376-377, 125–133. [CrossRef]

- Grzesik, W., Piotr Niesłony, Habrat, W., Sieniawski, J., & Laskowski, P. (2018). Investigation of tool wear in the turning of Inconel 718 superalloy in terms of process performance and productivity enhancement. 118, 337–346. [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, E., Riemer, H., D. Schröter, Henze, S., Sammler, F., Barthelmä, F., & Frank, H. (2018). Investigation of wear resistance of coated PcBN turning tools for hard machining. International Journal of Refractory Metals & Hard Materials, 72, 270–275. [CrossRef]

- Chinnasamy, M., Rathanasamy, R., Pal, S. K., & Palaniappan, S. K. (2022). Effectiveness of cryogenic treatment on cutting tool inserts: A review. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials, 108, 105946. [CrossRef]

- Mahendran, R., Rajkumar, P., Nirmal Raj, L., Karthikeyan, S., & Rajeshkumar, L. (2021). Effect of deep cryogenic treatment on tool life of multilayer coated carbide inserts by shoulder milling of EN8 steel. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering, 43(8), 378. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P. H. S., Israel, C. L., Da Silva, M. B., Klein, G. A., & Soccol, L. P. H. S. (2020). Effects of deep cryogenic treatment on microstructure, impact toughness and wear resistance of an AISI D6 tool steel. Wear, 456, 203382. [CrossRef]

- Singh, L. P. (2022). Effect of Cryogenic Treatment on Tool Life. IUP Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 15(2).

- Kara, F. (2014). Investigation of the effects of cryogenic process parameters on fatigue life and grindability of AISI 52100 steel. Karabuk University, Ph. D. dissertation, Karabuk, Turkey.

- Gill, S. S., & Singh, J. (2010). Effect of deep cryogenic treatment on machinability of titanium alloy (Ti-6246) in electric discharge drilling. Materials and Manufacturing Processes, 25(6), 378-385. [CrossRef]

- SreeramaReddy, T. V., Sornakumar, T., VenkataramaReddy, M., & Venkatram, R. (2008). Machining performance of low temperature treated P-30 tungsten carbide cutting tool inserts. Cryogenics, 48(9-10), 458–461. [CrossRef]

- Mukkoti, V. V., Sankaraiah, G., & Yohan, M. (2018). Effect of cryogenic treatment of tungsten carbide tools on cutting force and power consumption in CNC milling process. Production & Manufacturing Research, 6(1), 149-170. [CrossRef]

- Padmakumar, M., & Dinakaran, D. (2020). Investigation on the effect of cryogenic treatment on tungsten carbide milling insert with 11% cobalt (WC–11% Co). SN Applied Sciences, 2(6), 1050. [CrossRef]

- Collins, D. N. (1998). Cryogenic treatment of tool steels. Advanced materials & processes, 154(6), H23. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, D. Ramamoorthy, B., & Vijayaraghavan, L. (2008). Influence of different post treatments to maximize the wear resistance of 18 % Cr martensitic stainless steel by Taguchi method. Materials Letters, vol. 62, pp. 4403-4406.

- Akhbarizadeh, A., Shafyei, A., & Golozar, M. A. (2009). Effects of cryogenic treatment on wear behavior of D6 tool steel. Materials & Design, 30(8), 3259–3264. [CrossRef]

- Seah, K. H. W., Rahman, M., & Yong, K. (2003). Performance evaluation of cryogenically treated tungsten carbide cutting tool inserts. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture, 217(1), 29–43. [CrossRef]

- Gill, S. S., Singh, J., Singh, H., & Singh, R. (2011). Metallurgical and mechanical characteristics of cryogenically treated tungsten carbide (WC–Co). The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 58(1-4), 119–131. [CrossRef]

- Özbek, N. A., & Özbek, O. (2022). Effect of cryogenic treatment holding time on mechanical and microstructural properties of Sverker 21 steel. Materials Testing, 64(12), 1809-1817.

- SreeramaReddy, T. V., Sornakumar, T., VenkataramaReddy, M., & Venkatram, R. (2009). Machinability of C45 steel with deep cryogenic treated tungsten carbide cutting tool inserts. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials, 27(1), 181–185. [CrossRef]

- Kalsi, N. S., Sehgal, R., & Sharma, V. S. (2014). Effect of tempering after cryogenic treatment of tungsten carbide–cobalt bounded inserts. Bulletin of Materials Science, 37, 327-335. [CrossRef]

| C | Si | Mn | Cr | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.90 | 0.25 | 2.00 | 0.35 | 0.10 |

| Heat treatment, (Ht) | Coating type, (Ct) | Cutting speed, m/min, (Vc) | Feed rates, mm/rev, (f) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Cryogenic | CVD Coated | 200 | 0.16 |

| None | None | 250 | 0.24 |

| 300 | 0.32 |

| Exp. No. | Control Factors | Output Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Treatment | Coating Type | Cutting speed, (Vc), m/min | Feed rates (f), mm/rev | Surface Roughness (Ra) µm | Cutting Force (Fc), N | |

| 1 | None | None | 200 | 0.16 | 1.188 | 327.14 |

| 2 | None | None | 200 | 0.24 | 2.4137 | 458.98 |

| 3 | None | None | 200 | 0.32 | 4.2437 | 537.10 |

| 4 | None | None | 250 | 0.16 | 1.106 | 317.38 |

| 5 | None | None | 250 | 0.24 | 2.351 | 415.03 |

| 6 | None | None | 250 | 0.32 | 4.199 | 522.46 |

| 7 | None | None | 300 | 0.16 | 1.126 | 322.16 |

| 8 | None | None | 300 | 0.24 | 2.362 | 429.68 |

| 9 | None | None | 300 | 0.32 | 4.817 | 532.22 |

| 10 | Cryogenic | None | 200 | 0.16 | 1.141 | 317.38 |

| 11 | Cryogenic | None | 200 | 0.24 | 2.34 | 454.10 |

| 12 | Cryogenic | None | 200 | 0.32 | 4.2457 | 517.57 |

| 13 | Cryogenic | None | 250 | 0.16 | 1.04 | 302.73 |

| 14 | Cryogenic | None | 250 | 0.24 | 2.2623 | 428.16 |

| 15 | Cryogenic | None | 250 | 0.32 | 4.147 | 454.10 |

| 16 | Cryogenic | None | 300 | 0.16 | 1.1737 | 312.50 |

| 17 | Cryogenic | None | 300 | 0.24 | 2.278 | 415.03 |

| 18 | Cryogenic | None | 300 | 0.32 | 4.3017 | 506.12 |

| 19 | None | CVD | 200 | 0.16 | 2.116 | 371.09 |

| 20 | None | CVD | 200 | 0.24 | 4.684 | 527.34 |

| 21 | None | CVD | 200 | 0.32 | 7.684 | 703.12 |

| 22 | None | CVD | 250 | 0.16 | 1.857 | 340.62 |

| 23 | None | CVD | 250 | 0.24 | 4.4023 | 517.57 |

| 24 | None | CVD | 250 | 0.32 | 7.529 | 488.28 |

| 25 | None | CVD | 300 | 0.16 | 2.288 | 356.44 |

| 26 | None | CVD | 300 | 0.24 | 4.5673 | 522.34 |

| 27 | None | CVD | 300 | 0.32 | 7.7323 | 659.17 |

| 28 | Cryogenic | CVD | 200 | 0.16 | 2.1867 | 322.03 |

| 29 | Cryogenic | CVD | 200 | 0.24 | 4.535 | 473.63 |

| 30 | Cryogenic | CVD | 200 | 0.32 | 7.5947 | 600.58 |

| 31 | Cryogenic | CVD | 250 | 0.16 | 2.081 | 336.91 |

| 32 | Cryogenic | CVD | 250 | 0.24 | 4.375 | 458.98 |

| 33 | Cryogenic | CVD | 250 | 0.32 | 6.900 | 590.82 |

| 34 | Cryogenic | CVD | 300 | 0.16 | 2.071 | 351.56 |

| 35 | Cryogenic | CVD | 300 | 0.24 | 4.523 | 434.57 |

| 36 | Cryogenic | CVD | 300 | 0.32 | 7.3743 | 595.93 |

| Source | DF | Seq SS | Contribution | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 12 | 367059 | 93.28% | 367059 | 30588 | 26.60 | 0.000 |

| Linear | 4 | 350415 | 89.05% | 350415 | 87604 | 76.19 | 0.000 |

| Vc | 1 | 1238 | 0.31% | 1238 | 1238 | 1.08 | 0.310 |

| F | 1 | 310431 | 78.89% | 310431 | 310431 | 269.99 | 0.000 |

| Ht | 1 | 6278 | 1.60% | 6278 | 6278 | 5.46 | 0.029 |

| Ct | 1 | 32468 | 8.25% | 32468 | 32468 | 28.24 | 0.000 |

| Square | 2 | 8902 | 2.26% | 8902 | 4451 | 3.87 | 0.036 |

| Vc*Vc | 1 | 6839 | 1.74% | 6839 | 6839 | 5.95 | 0.023 |

| F*F | 1 | 2063 | 0.52% | 2063 | 2063 | 1.79 | 0.193 |

| 2-Way Interaction | 6 | 7742 | 1.97% | 7742 | 1290 | 1.12 | 0.380 |

| Vc*F | 1 | 306 | 0.08% | 306 | 306 | 0.27 | 0.611 |

| Vc*Ht | 1 | 46 | 0.01% | 46 | 46 | 0.04 | 0.843 |

| Vc*Ct | 1 | 12 | 0.00% | 12 | 12 | 0.01 | 0.920 |

| F*Ht | 1 | 305 | 0.08% | 305 | 305 | 0.26 | 0.612 |

| F*Ct | 1 | 6304 | 1.60% | 6304 | 6304 | 5.48 | 0.028 |

| Ht*Ct | 1 | 770 | 0.20% | 770 | 770 | 0.67 | 0.422 |

| Error | 23 | 26445 | 6.72% | 26445 | 1150 | ||

| Total | 35 | 393504 | 100.00% |

| Ht | Ct | Equation |

|---|---|---|

| None | None | |

| Cryogenic | None | |

| None | CVD | |

| Cryogenic | CVD |

| Inputs | Optimum Machining Parameters | RSM Prediction | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Goal | Vc, (m/min) | f, (mm/rev) | Ht | Ct | Lower | Target | Predicted response | Upper | Desirability |

| Fc (N) | Minimum | 252.525 | 0.16 | None | CVD | 302.73 | 302.73 | 339.99 | 703.12 | 0.906 |

| Source | DF | Seq SS | Contribution | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 12 | 158.219 | 99.74% | 158.219 | 13.185 | 739.09 | 0.000 |

| Linear | 4 | 149.797 | 94.43% | 149.797 | 37.449 | 2099.25 | 0.000 |

| Vc | 1 | 0.002 | 0.00% | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.14 | 0.715 |

| F | 1 | 110.056 | 69.38% | 110.056 | 110.056 | 6169.29 | 0.000 |

| Ht | 1 | 0.122 | 0.08% | 0.122 | 0.122 | 6.84 | 0.015 |

| Ct | 1 | 39.616 | 24.97% | 39.616 | 39.616 | 2220.72 | 0.000 |

| Square | 2 | 1.159 | 0.73% | 1.159 | 0.579 | 32.48 | 0.000 |

| Vc*Vc | 1 | 0.280 | 0.18% | 0.280 | 0.280 | 15.68 | 0.001 |

| F*F | 1 | 0.879 | 0.55% | 0.879 | 0.879 | 49.28 | 0.000 |

| 2-Way Interaction | 6 | 7.264 | 4.58% | 7.264 | 1.211 | 67.86 | 0.000 |

| Vc*F | 1 | 0.012 | 0.01% | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.65 | 0.429 |

| Vc*Ht | 1 | 0.033 | 0.02% | 0.033 | 0.033 | 1.83 | 0.190 |

| Vc*Ct | 1 | 0.022 | 0.01% | 0.022 | 0.022 | 1.25 | 0.276 |

| F*Ht | 1 | 0.114 | 0.07% | 0.114 | 0.114 | 6.39 | 0.019 |

| F*Ct | 1 | 7.080 | 4.46% | 7.080 | 7.080 | 396.87 | 0.000 |

| Ht*Ct | 1 | 0.003 | 0.00% | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.18 | 0.673 |

| Error | 23 | 0.410 | 0.26% | 0.410 | 0.018 | ||

| Total | 35 | 158.629 | 100.00% |

| Ht | Ct | Equation |

|---|---|---|

| None | None | |

| Cryogenic | None | |

| None | CVD | |

| Cryogenic | CVD |

| Inputs | Optimum Machining Parameters | RSM Prediction | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Goal | Vc, (m/min) | f, (mm/rev) | Ht | Ct | Lower | Target | Predicted response | Upper | Desirability |

| Ra (µm) | Minimum | 243.434 | 0.16 | None | None | 1.04 | 1.04 | 0.96 | 7.7323 | 0.960 |

| Coated | Coated + Cryogenic | Uncoated | Uncoated + Cryogenic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Co (%) | 21.353 | 36.542 | 26.421 | 34.463 |

| Ɛ–Co (%) | 8.768 | 11.410 | 18.142 | 27.332 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).