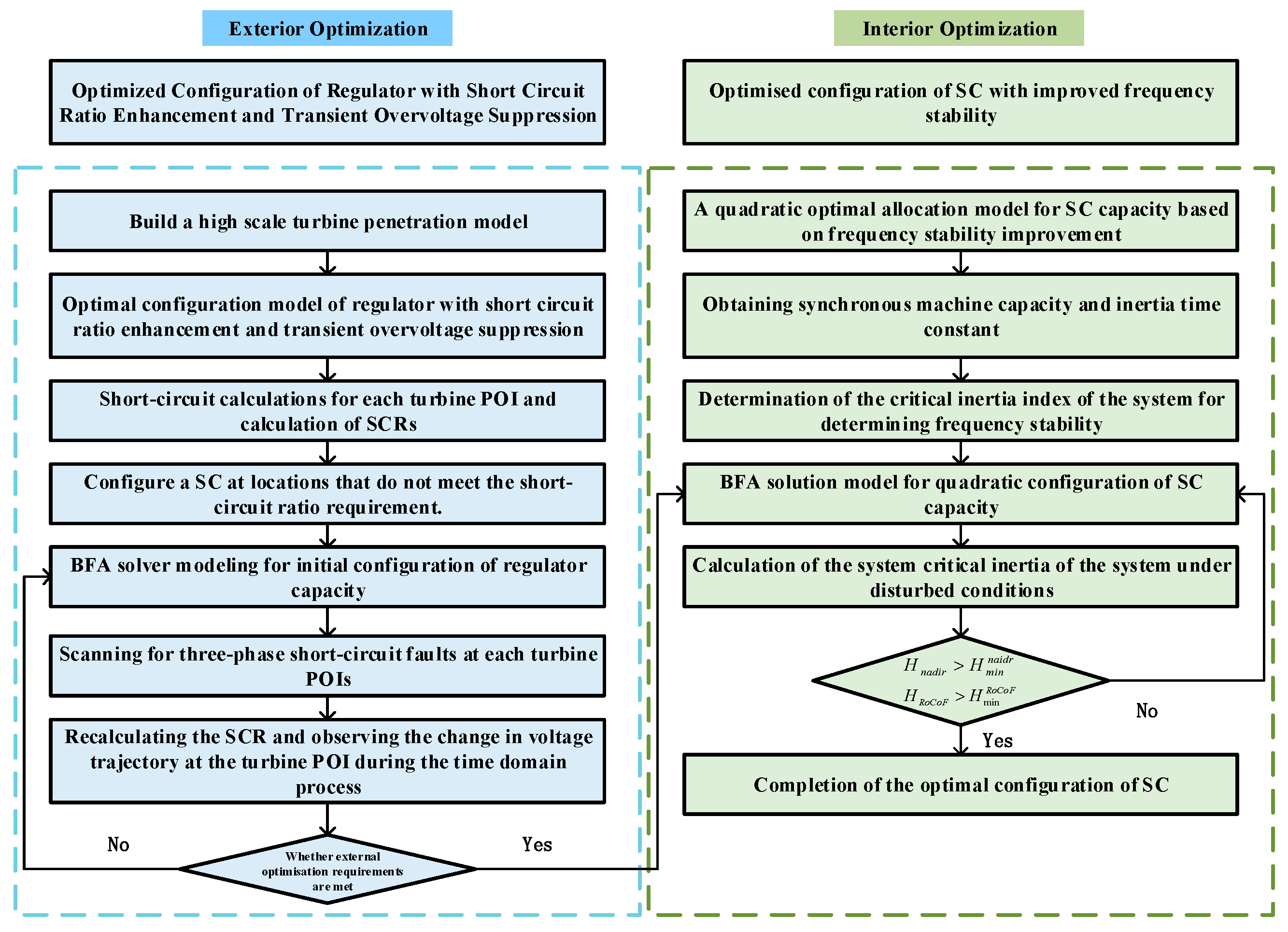

2.1. The Impact of Synchronous Condenser Configuration on the Short-Circuit Capacity at the Wind Turbine POI

The short-circuit capacity at a point in the grid is the product of the three-phase short-circuit current at that point and the rated voltage, i.e., equation (1)

Short-circuit capacity is a crucial indicator of the strength of grid voltage support. High short-circuit capacity (corresponding to low impedance) indicates grid robustness, meaning that load variations or the connection of shunt filters do not cause significant voltage fluctuations. Conversely, low short-circuit capacity indicates increased grid vulnerability, where load changes or the connection of shunt filters may lead to substantial voltage fluctuations.

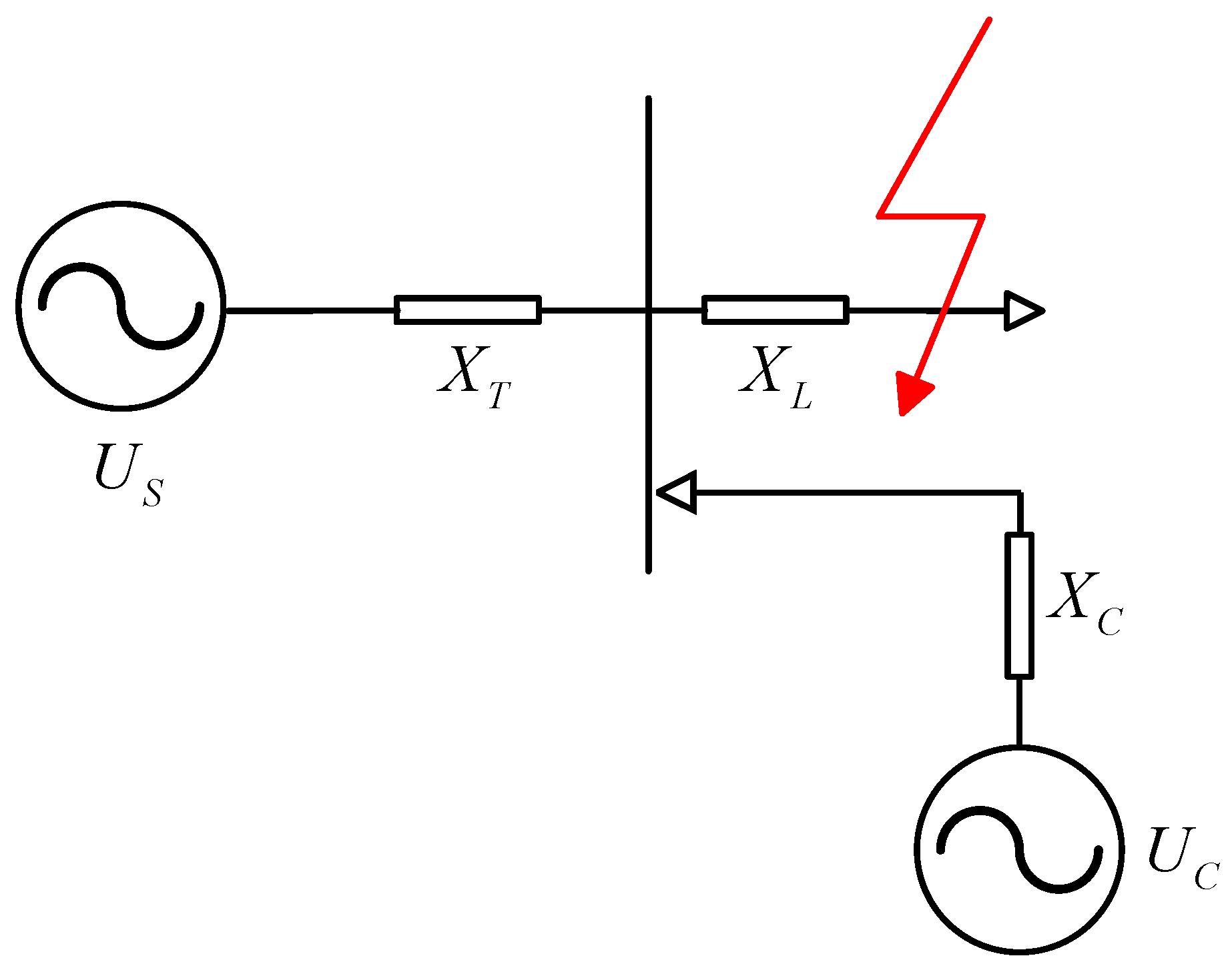

Given that the SC is connected to the grid through the stator resistor, it can be regarded as a shunt inductive branch in the grid. For the circuit shown in

Figure 1, Let its network transfer impedance equivalent to positive sequence reactance be

, the equivalent impedance between the SC connect point and the short-circuit point is positive sequence equivalent reactance

, the positive sequence reactance of the SC is

, the system equivalent power supply is

.

From equation (1), short-circuit current directly affects short-circuit capacity. Therefore, the effect of SC connection on short-circuit current is analyzed first. In the event of a short-circuit fault before the SC is connected, the per unit (p.u.) value is used for calculation. The short-circuit current

flowing at the short-circuit current is

After connecting to the SC, the short-circuit current flowing at the short-circuit point changes to

Considering that both line and SC stator windings are inductive, thus there is, i.e. . It can be seen that connecting to the SC increases the short circuit current and, subsequently, the short circuit capacity.

2.2. Evaluation Index for Grid Voltage Support Strength

The model of the SC connected to the grid is shown in

Figure 2. The SCR is given by equation (4), Used to ensure that the wind turbine POI is of adequate strength [

19], and can be used to characterize the support strength of the grid voltage.

In the equation,

is the short-circuit capacity of bus

,

is the nominal active power of the wind turbine installed at busbar

,

is the Thevenin's equivalent impedance. The SCR can be equivalently expressed in equation (5) when the rated bus voltages

and

are taken as the reference values, It can be seen that the larger the SCR, the smaller the Thevenin's equivalent impedance

is, and a disturbance in the system will not cause a significant change in voltage magnitude.

The results of short-circuit power calculations vary depending on the method used. In this paper, short-circuit calculations are performed according to the IEC 60909 standard, which is widely applied in grid planning.

IEC 60909 defines maximum and minimum values for short-circuit power, which are calculated using different network configurations. In this paper, these two configurations are reconciled by taking the average of the maximum and minimum short-circuit power, as expressed in equation (6).

In the equation,

is the maximum short-circuit capacity of bus

,

is the minimum short circuit capacity of bus

,

is the average of the maximum and minimum short circuit capacity. Combining equation. (4) with equation. (6), the SCR can be expressed by equation (7).

2.3. The Effect of Synchronous Condenser Connection on Transient Overvoltage at the Wind Turbine POI

1) Transient overvoltage levels in the wind farm before and after synchronous condenser connection.

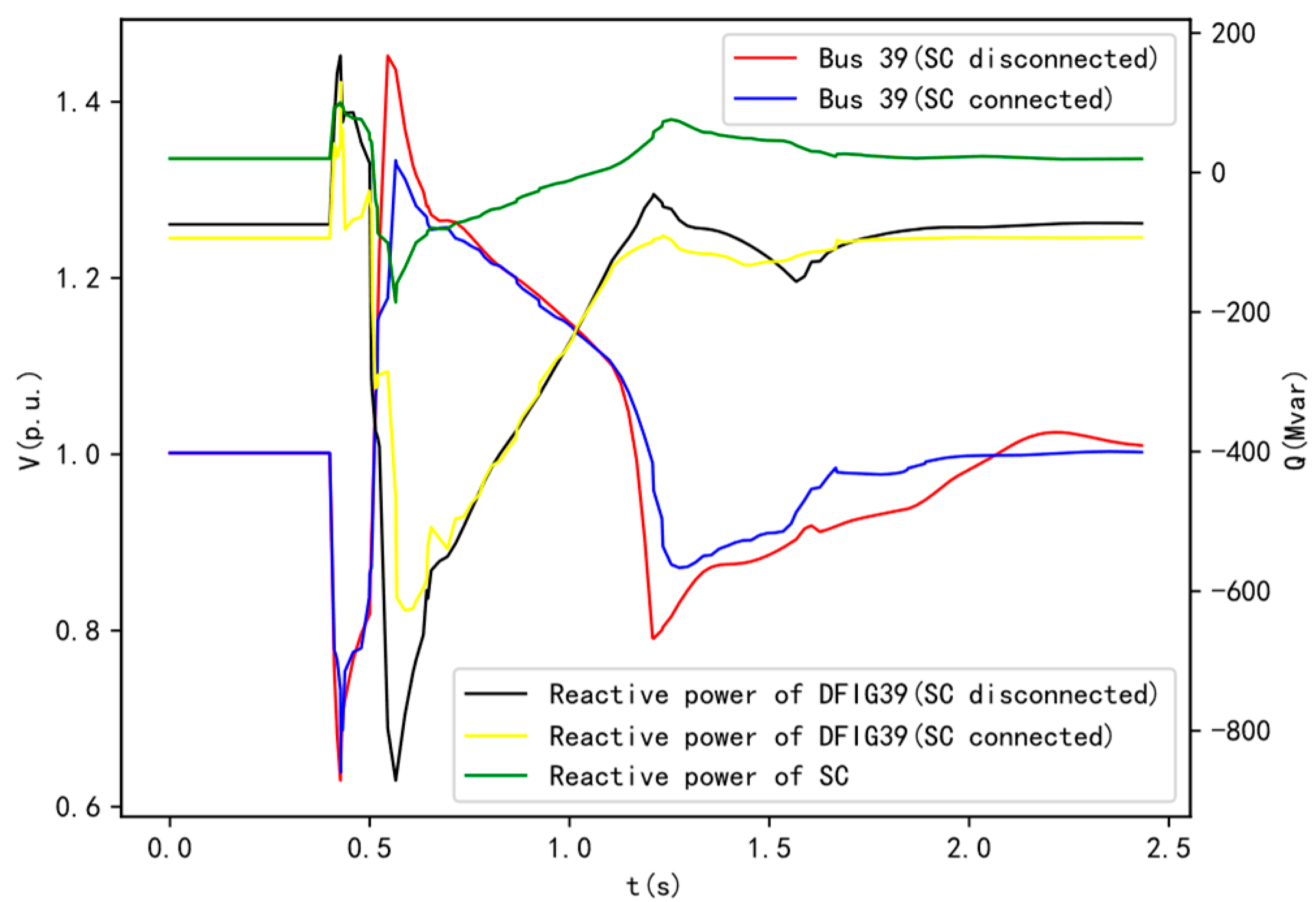

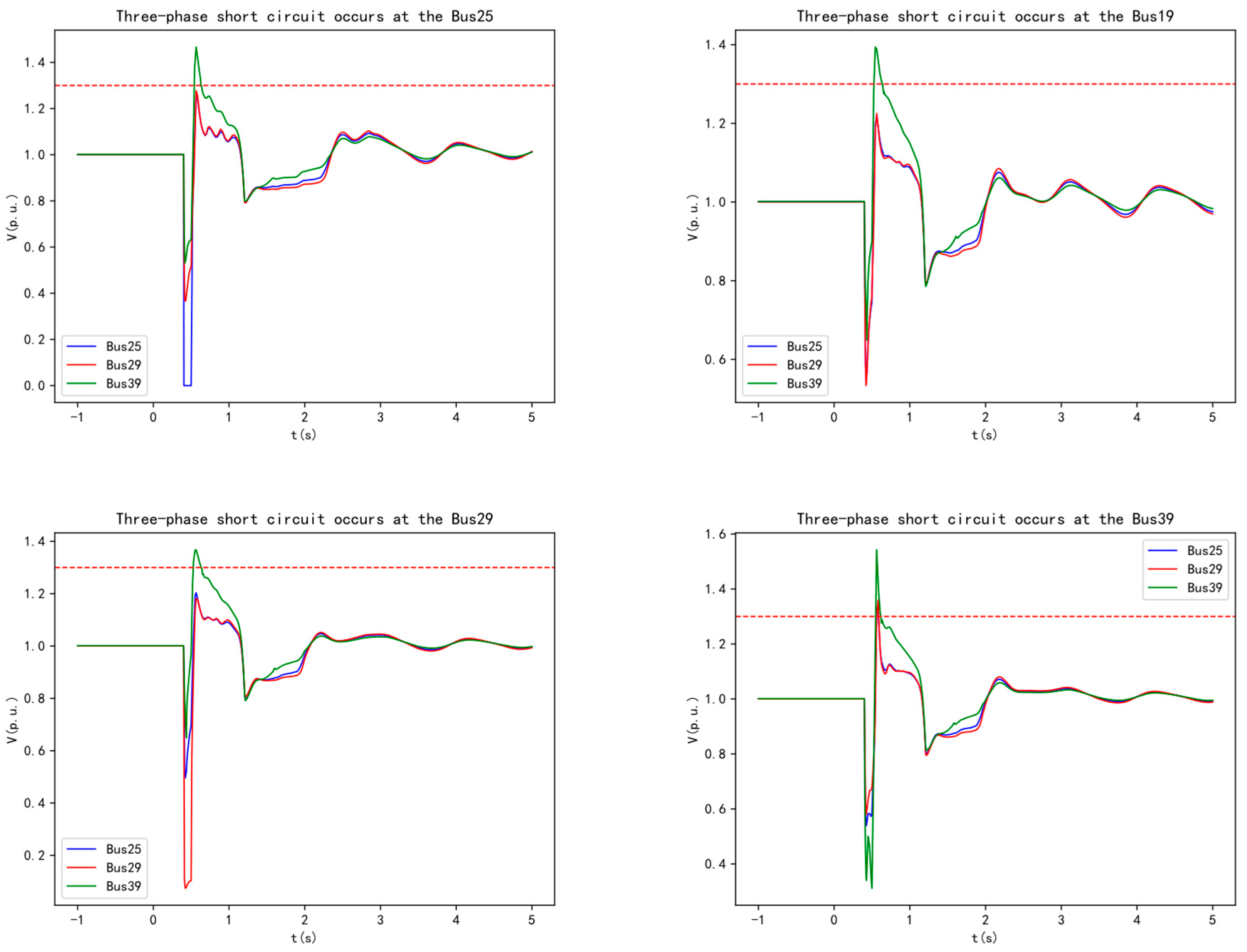

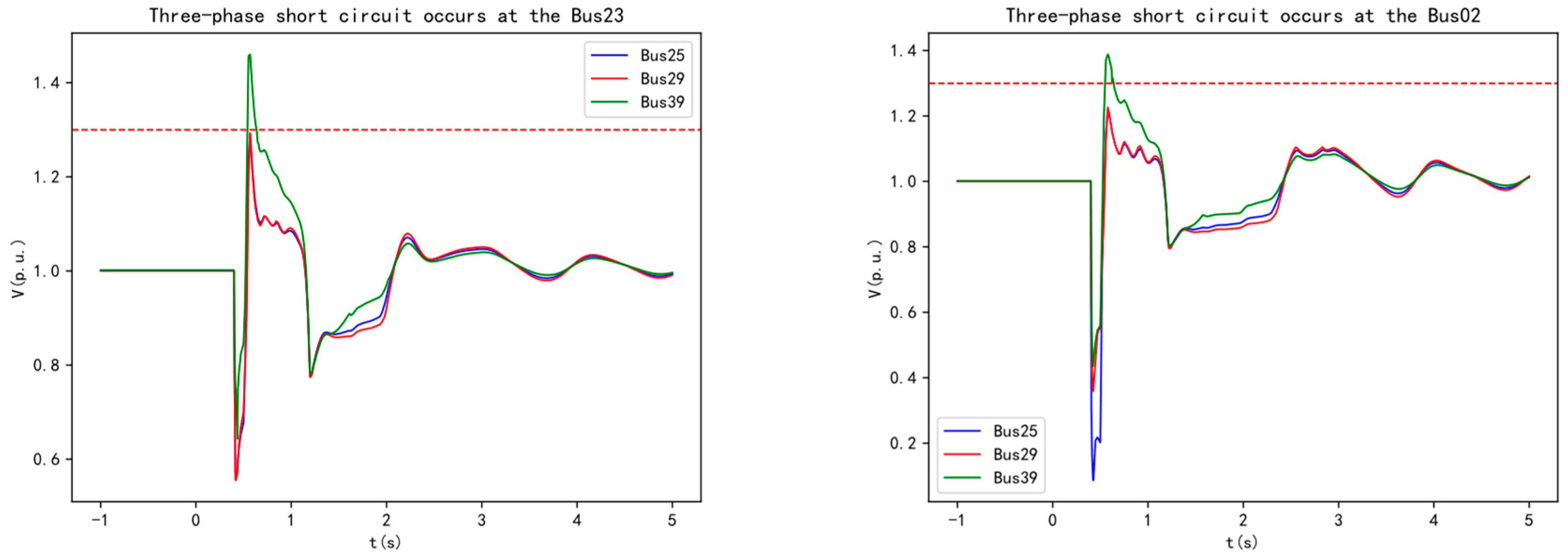

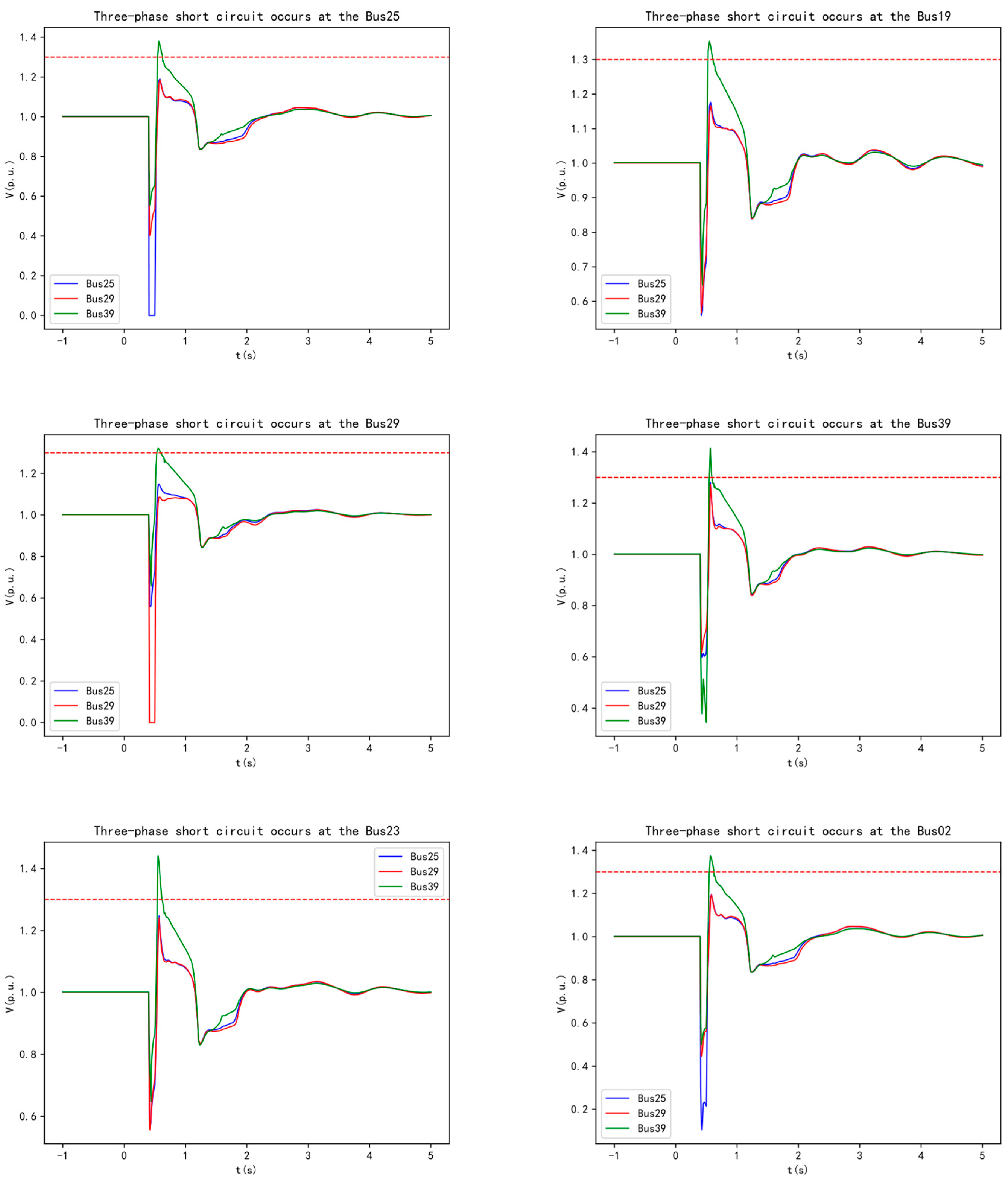

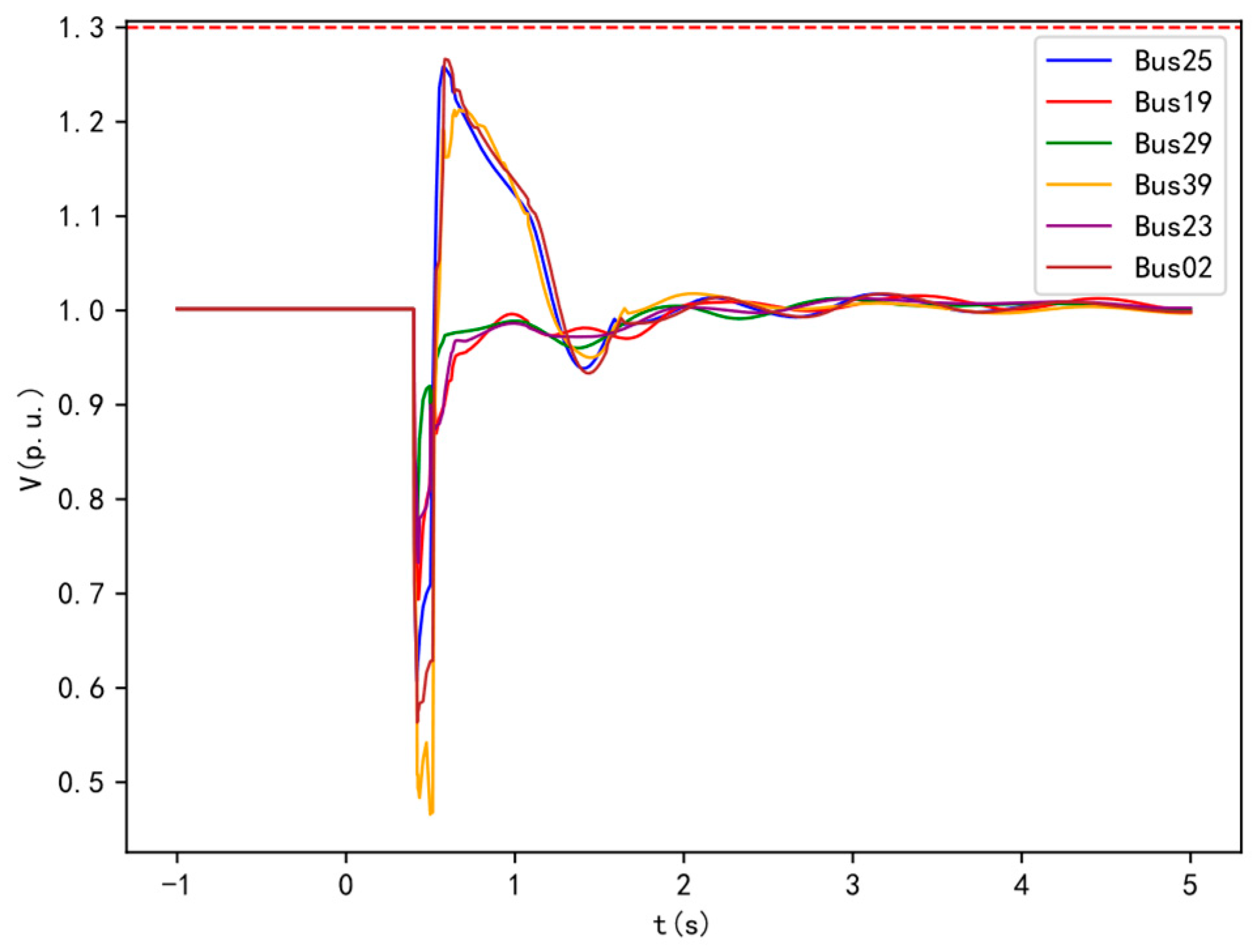

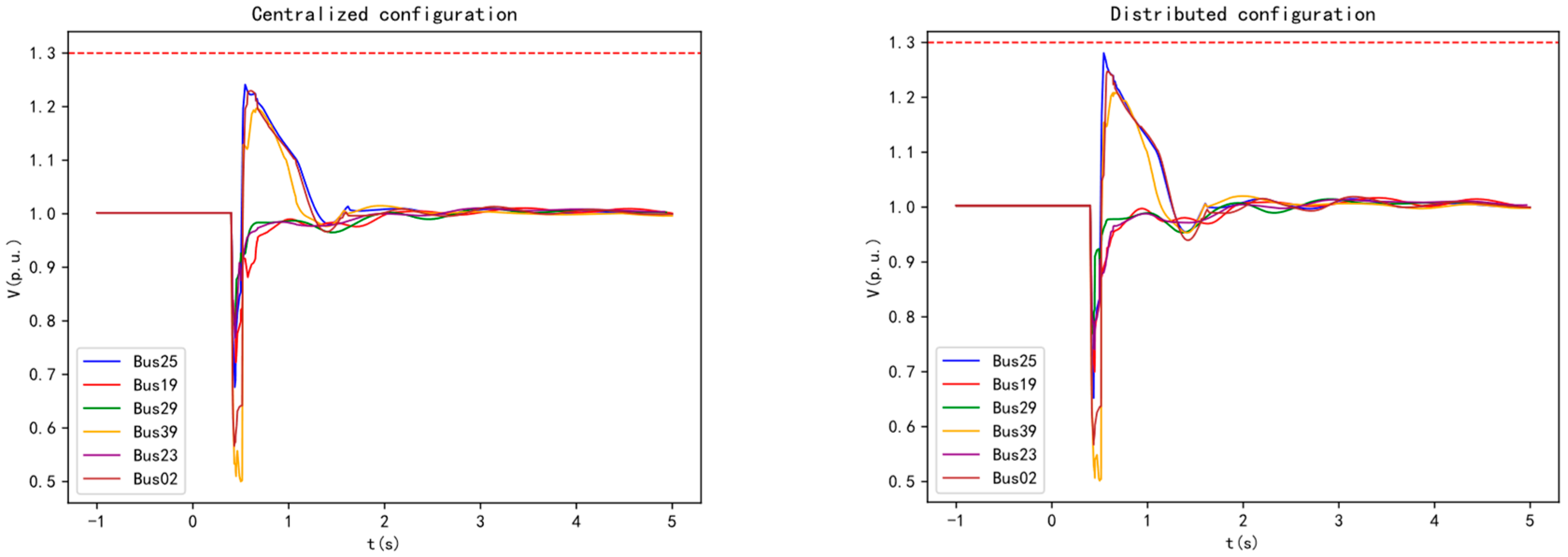

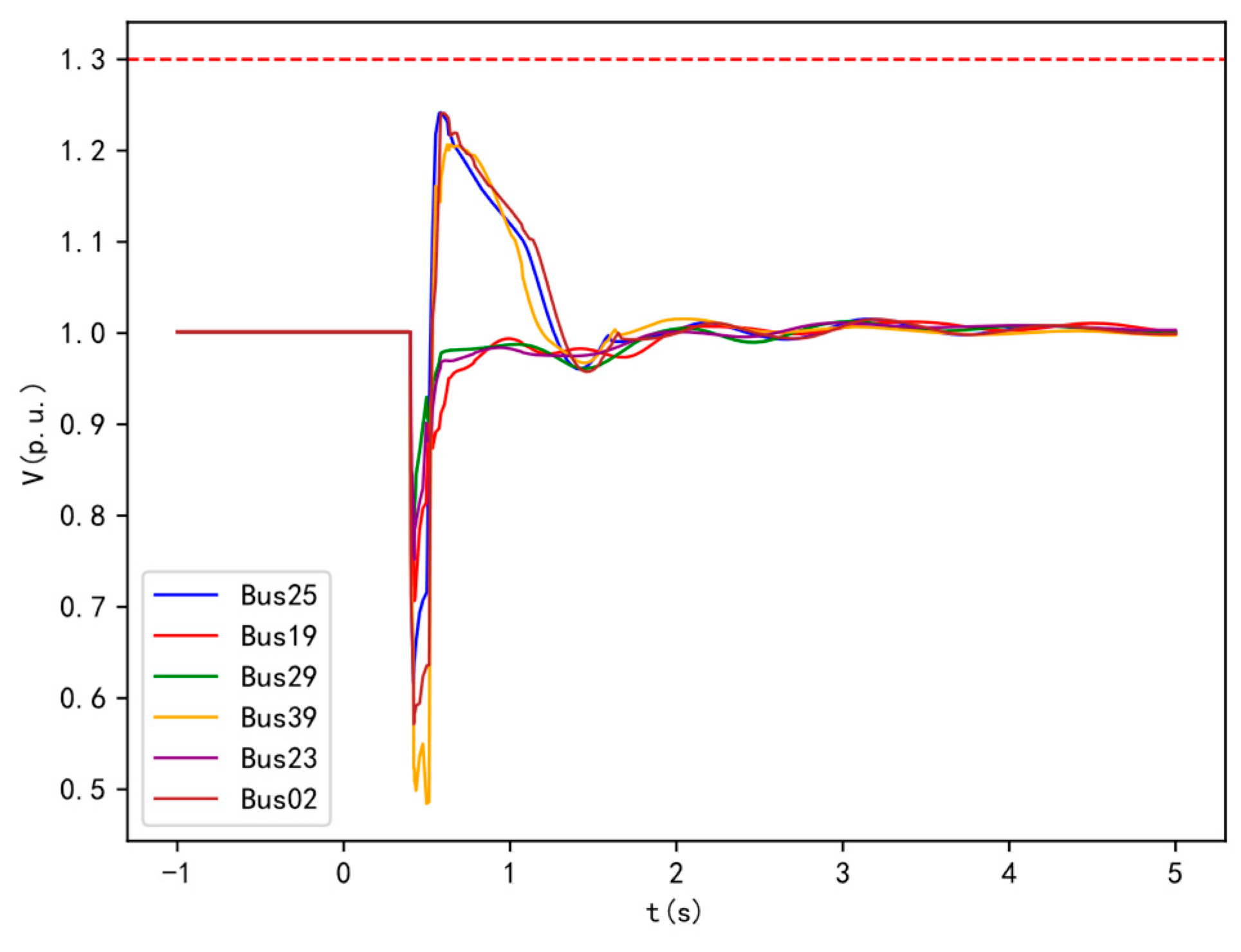

In the modified arithmetic example (presented in

Section 4), Bus 25 experiences a three-phase short-circuit fault lasting 0.1 seconds. Before and after the connection of wind turbine POI buses Bus 25, Bus 29, and Bus 39 to the 50 MVA SC, the changes in voltage at the wind turbine POI of DFIG39, the output reactive power, and the SC's reactive power are shown in

Figure 2.

Before the SC is connected, during a fault, the voltage at Bus 39 drops, and the connected DFIG39 wind turbine increases its reactive power output. Due to the hysteresis characteristic of the wind turbine's reactive power response, the voltage recovers instantaneously after the fault is cleared. However, because of the time-delay characteristic of the control system, the additional reactive power generated during the fault cannot be withdrawn, resulting in excess reactive power and transient overvoltage at the machine terminal. Simulation results show that the maximum transient overvoltage reaches 1.452 p.u.

After the SC is connected, its synchronous rotating nature and electromagnetic transient characteristics help maintain magnetic flux in the windings before and after fault disturbances, making the reactive power response instantaneous. At the moment of the fault, the voltage drops, and the SC immediately increases its reactive power output to mitigate the voltage drop. Once the fault is cleared, the voltage recovers, and the SC quickly reduces its reactive power and absorbs the excess reactive power, effectively suppressing transient overvoltage. The maximum voltage is reduced to 1.333 p.u. The electromagnetic transient characteristics of the SC windings contribute to suppressing the transient overvoltage level after the fault is cleared.

2) The Mechanism of Transient Overvoltage Suppression by Synchronous Condenser Connection

SCs are connected to the wind farm via transformers and serve as reactive power compensation devices, with their active power being minimal and negligible. Based on the active power expression for generators, when the power angle

, the high-voltage side voltage of the synchronous condenser transformer and the injected reactive power can be expressed as follows:

In the equation, , , represent the high-voltage side voltage of the SC, the direct axis voltage component, and the quadrature axis voltage component, respectively. and represent the direct axis and quadrature axis current components, respectively, while denotes the reactive power injected by the SC.

The change in reactive power output

of the SC before and after a disturbance can be expressed in incremental form as:

In the formula, the subscript 0 represents the electrical quantity before the disturbance, and the symbol represents the change in the electrical quantity.

The change in before and after the disturbance is very large, which has a significant impact on the reactive power change of the SC. The following derivation is combined with the SC model.

Based on the

-axis transient and subtransient differential equations related to

in the six-order model of the synchronous machine, and the algebraic equation of the internal voltage and terminal voltage, when ignoring the stator resistance, the following expressions can be derived:

In the formula, , , and represent the synchronous reactance, transient reactance, and subtransient reactance of the -axis for the SC, respectively. and represent the transient and subtransient open-circuit time constants of the -axis for the SC, respectively. , and represent the field excitation voltage, -axis transient voltage, and -axis subtransient voltage of the SC, respectively. and represent the derivatives of and , respectively, and represents the reactance of the transformer at the output of the SC.

The expressions for

and

are:

In the formula, and represent the magnetic fluxes of the field winding and the damper winding , respectively. , , and represent the direct-axis armature reaction reactance, the leakage reactance of the winding, and the leakage reactance of the winding, respectively.

Expressing equation (10) in incremental form and applying the Laplace transform, we get:

In the equation, , , and represent the changes in the corresponding voltages, and is the Laplace operator.

From the first equation of (13), we can solve for

, which is:

In the above equation,

is expressed as the difference between the change in the subtransient

-axis internal voltage and the change in the high-voltage side terminal voltage of the SC, divided by the reactance

.

can be derived from equation (13) as follows:

In the equation, the coefficients

,

,

,

, and

are, respectively:

Combining equations (14) and (15) allows us to express the time response characteristics of

after the fault disturbance. At the instant of disturbance, due to the conservation nature of the winding magnetic flux, equation (12) indicates that

cannot change abruptly, so in the instant of disturbance,

. At this moment, equation (14) can be expressed as:

Substituting into equation (10), the instantaneous change in reactive power of the SC after the disturbance is:

From the first term of the above formula, it can be seen that since , the SC has a strong instantaneous reactive power support capability. The corresponding reactive power response is in the same direction as . Therefore, during the transient overvoltage phase after the fault is cleared, it will absorb a large amount of reactive power to suppress the transient voltage rise. The second term is usually much smaller than the first term (the change in current is greater than the pre-disturbance . When the pre-disturbance is smaller or negative (the synchronous condenser is operating in the leading power factor mode), the reactive power support capability for voltage is stronger, which is more favorable for suppressing the transient overvoltage after the fault is cleared.

2.4. The Impact of Synchronous Condenser Connection on Frequency Stability during the System Inertia Response Phase

The frequency of a power system is collectively determined by the rotational speeds of the numerous synchronous machines within it. When a disturbance occurs in the system, due to the rotational inertia and conservation of magnetic flux in the rotor windings of synchronous machines, the magnitude and phase of the equivalent electromotive force (EMF) of these machines, including SCs, do not change abruptly. This characteristic ensures that when a disturbance occurs, such as a sudden increase in load causing an active power imbalance in the receiving-end system, the power deficit is automatically transmitted and distributed to synchronous machines with voltage source characteristics, in proportion to the inverse of the electrical distance from the disturbance point to each machine. As a result, the output electromagnetic power (corresponding to the resistive torque acting on the rotor shaft) of the synchronous machines increases rapidly. At this point, the prime mover power (corresponding to the motive torque acting on the rotor shaft) has not yet changed. According to the rotor motion equation of the synchronous machine (as shown in equation (19)), the speed of the synchronous machine will decrease. This process is referred to as the inertial response of the synchronous machine.

In the equation is the unit electrical speed or system frequency, is the rated electrical speed of the unit or the rated frequency of the system; is the unit inertia time constant or the system equivalent inertia time constant; is the prime mover power; is the output electromagnetic power of the synchronous machine.

Synchronous condensers, as a type of synchronous machine, adhere to the conservation of magnetic flux and possess an inertial response, similar to synchronous generators. This means that SCs, like synchronous generators, exhibit the characteristics of a voltage source, where the magnitude and phase do not change abruptly. This characteristic ensures that part of the power deficit in the system will be transmitted to the SC through the electrical network in a timely manner. For SCs, the prime mover power in equation (19) is zero; if friction losses during operation are neglected, the electromagnetic power is also zero in the steady state. However, during the transient process of grid disturbances, SCs, like synchronous generators, will share the power disturbance, meaning . Due to the inherent inertia of their rotating elements, SCs take on a share of the system's power disturbance.

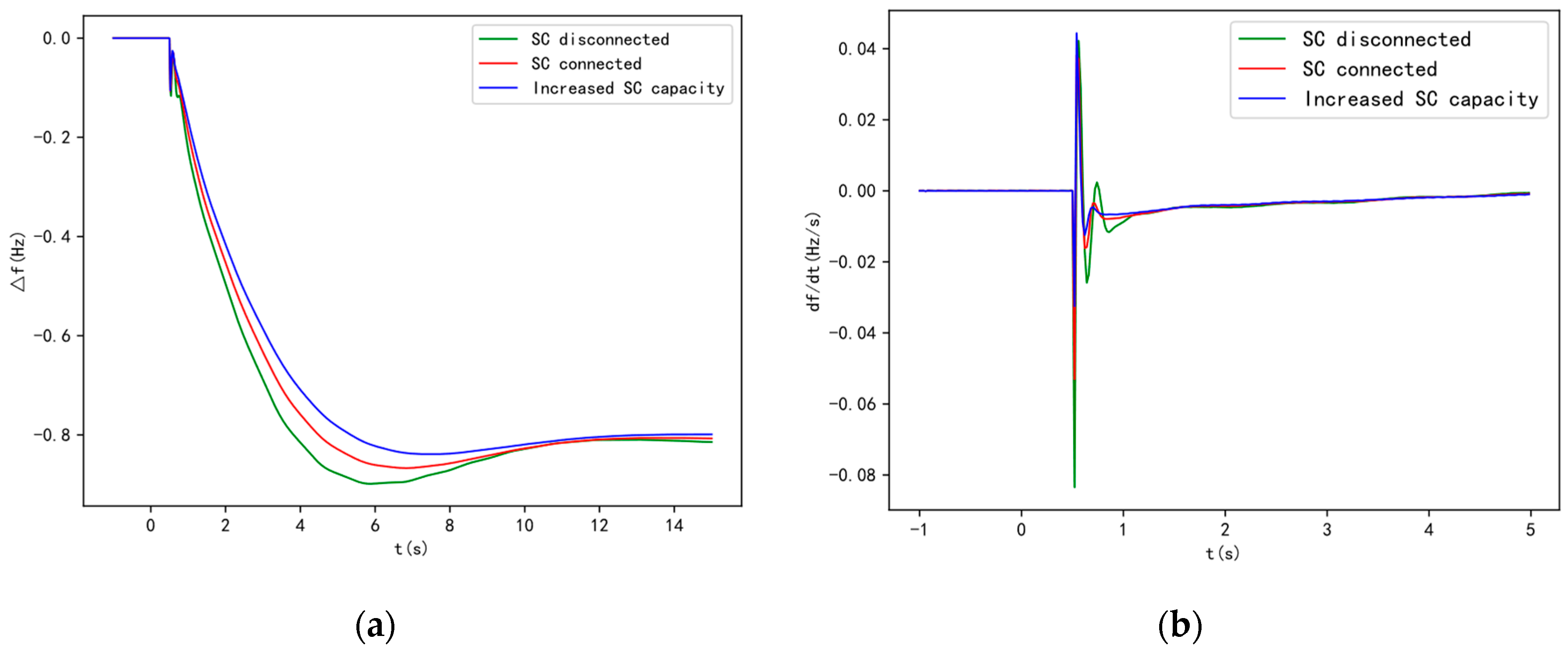

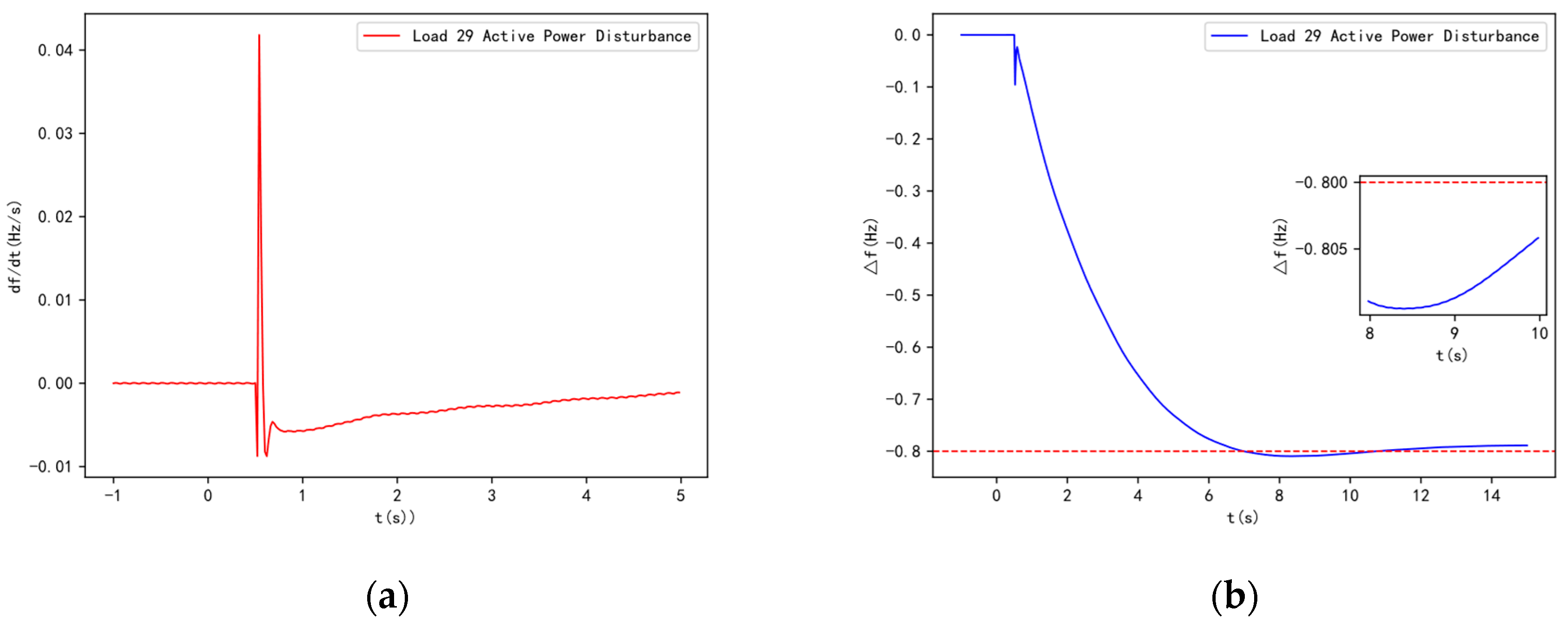

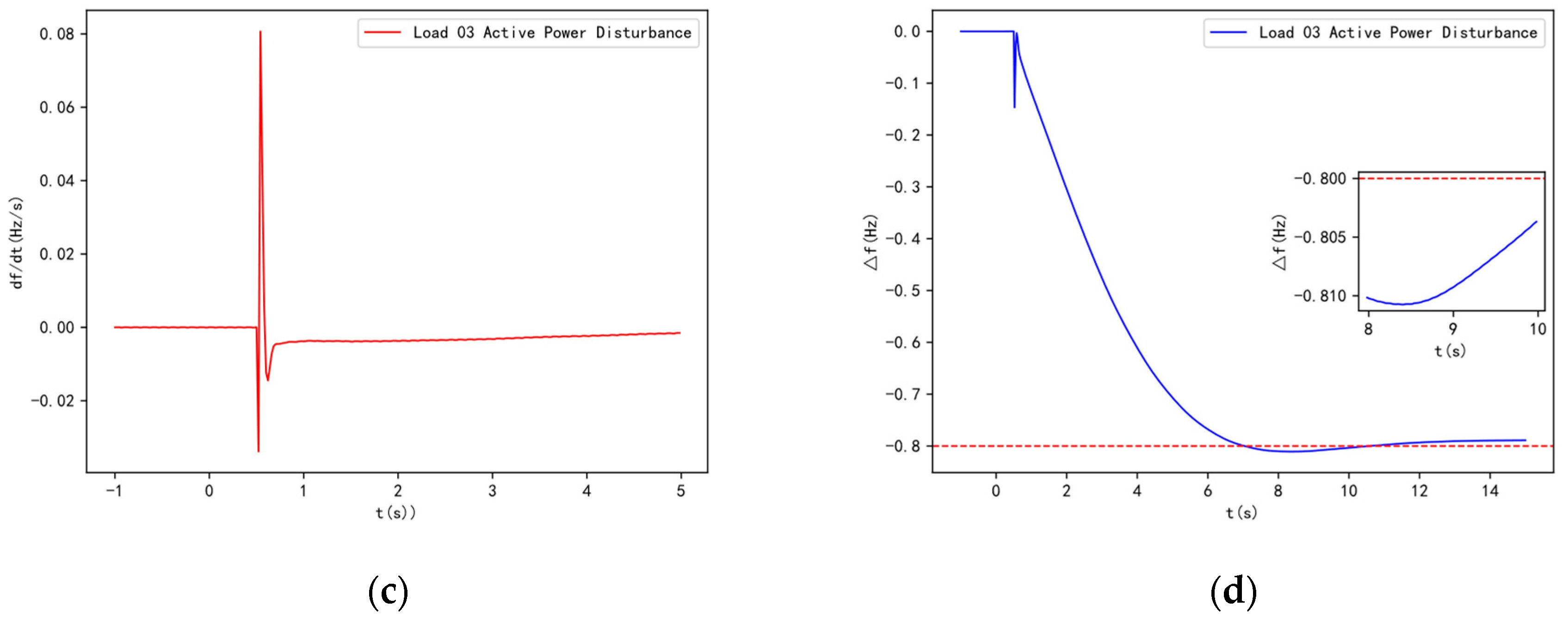

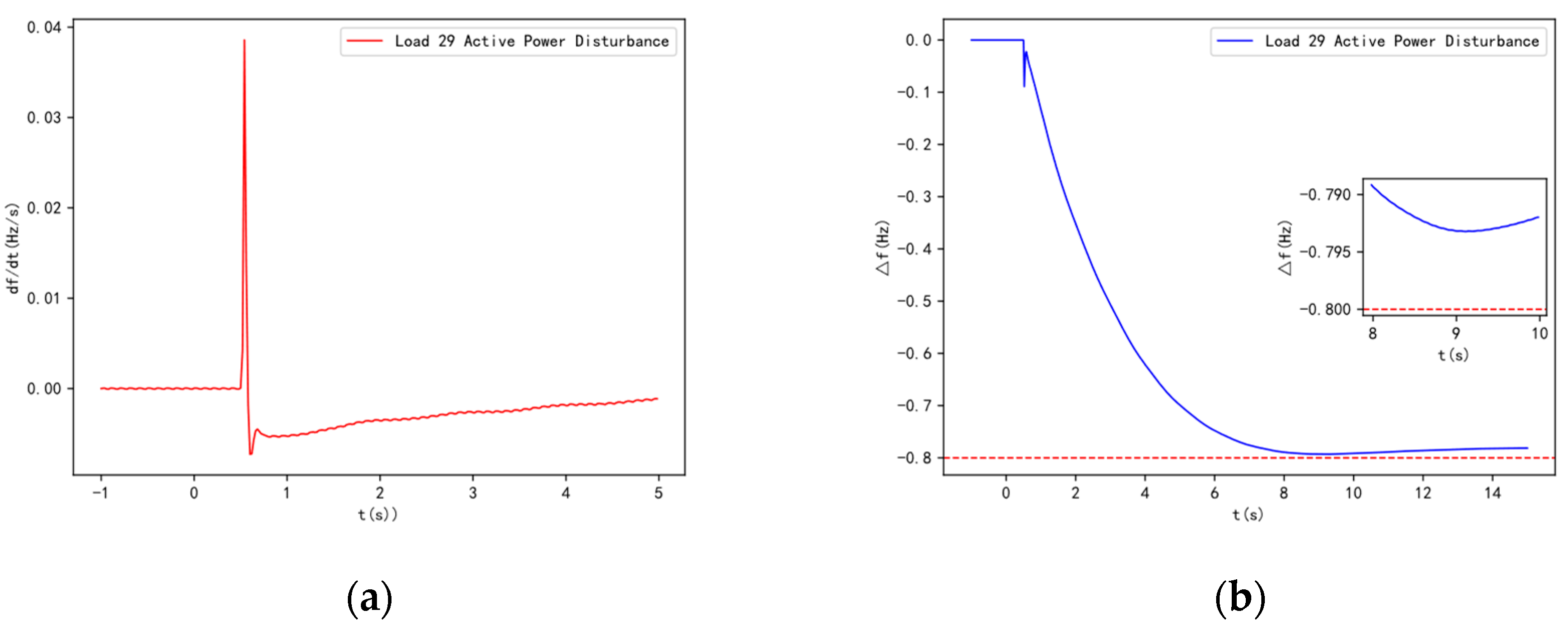

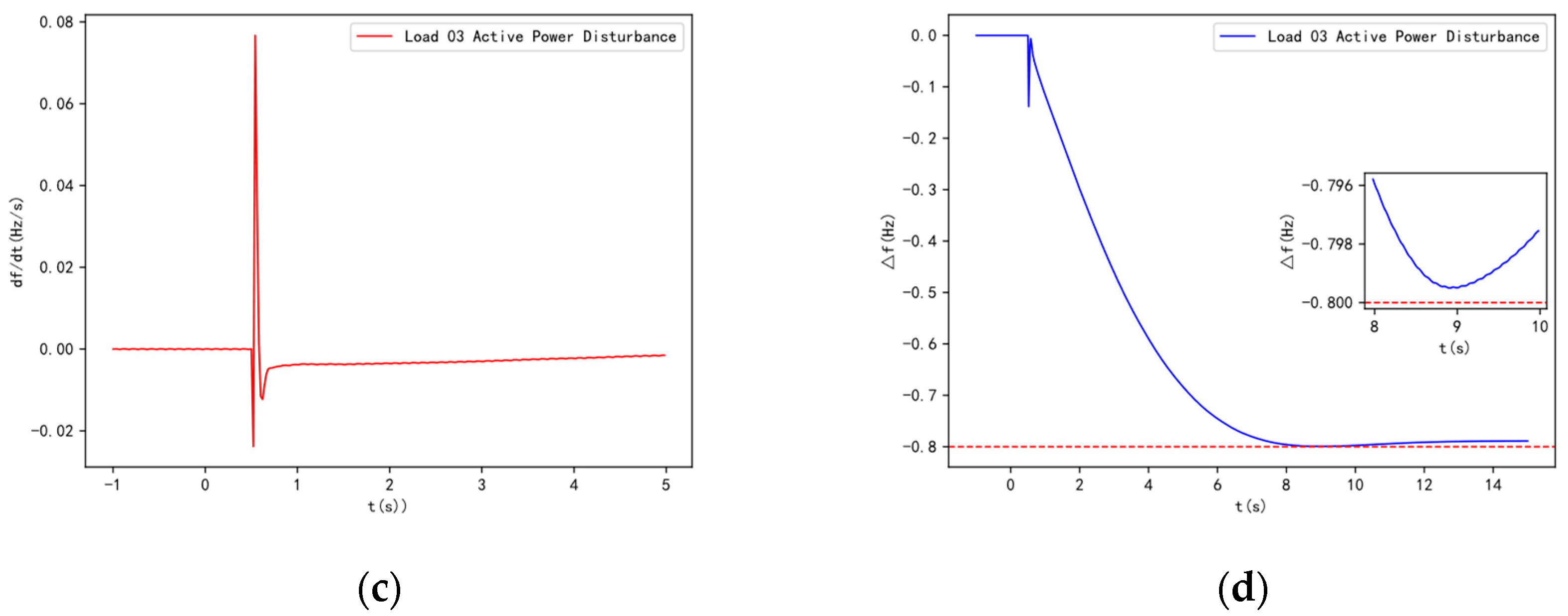

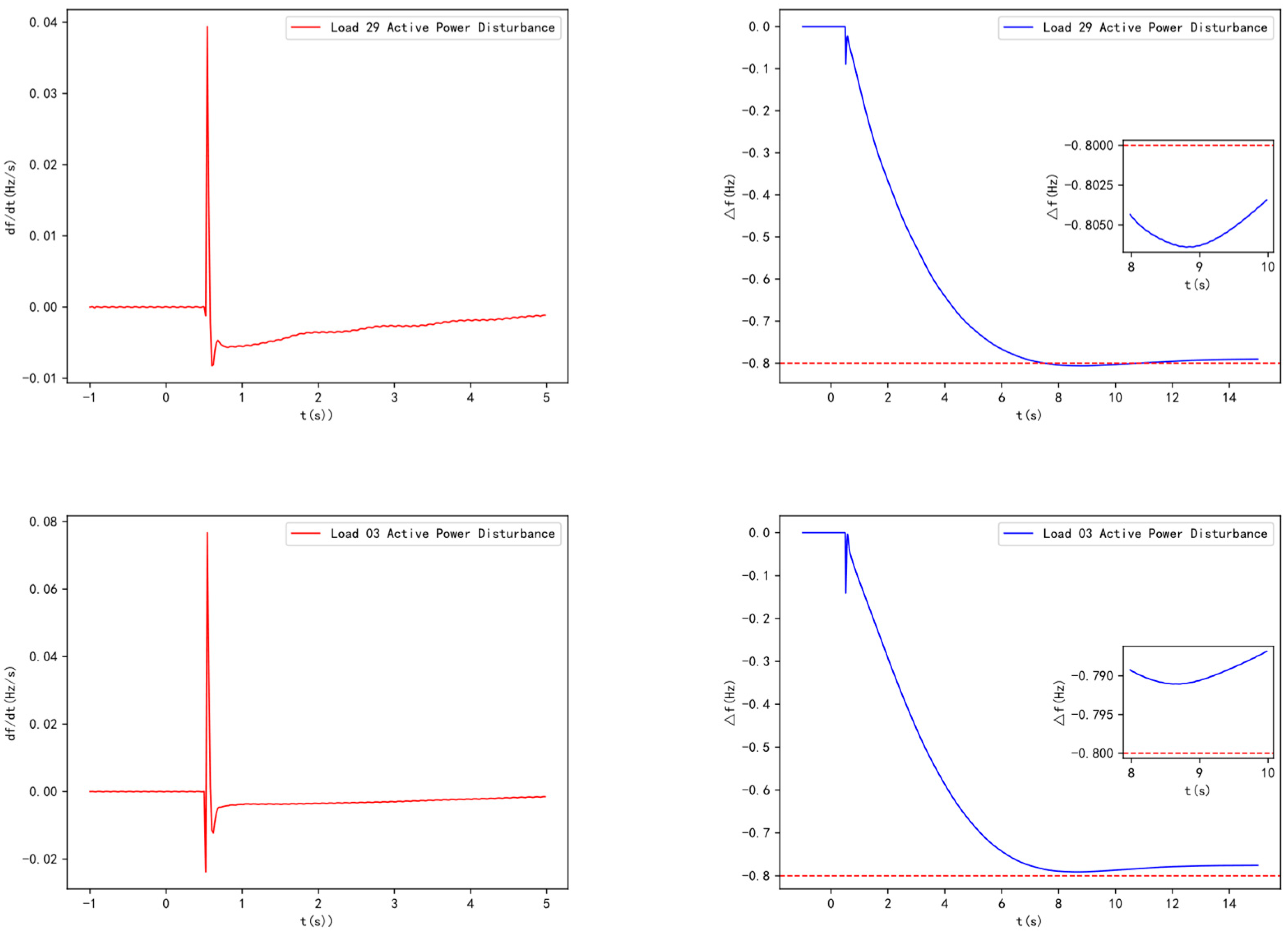

When a power deficit disturbance occurs in the system, both SCs and generators will increase their electromagnetic power output, leading to a decrease in their rotational speeds. Due to the effect of the generator set's prime mover governor system, or the primary frequency regulation effect, the generator's rotational speed will decrease to a certain extent (after passing the dead zone), after which the prime mover power will increase, slowing the speed decrease or even causing the speed to rise. SCs, however, do not have a prime mover system and lack primary frequency regulation capability. Therefore, over time, the rotational speed of the SC will become lower than that of the generator, causing the phase of the generator's potential to gradually lead to that of the condenser. According to the characteristics of the electrical network, active power flows from the leading phase to the lagging phase. As a result, over time, the electromagnetic power output by the SC will decrease, automatically transferring to the generator and eventually being fully borne by the generator. Ignoring friction losses, the electromagnetic power output by the SC will return to zero in the steady state. The impact of the condenser's connection on system frequency is shown in

Figure 4. In summary, the inertial response of the SC increases the overall inertia of the system. Although it does not affect the steady-state frequency of the system after the disturbance, it influences the frequency dynamics following the disturbance. In conjunction with the system's primary frequency regulation, it delays the occurrence of the lowest frequency to some extent. When the power deficit is large and the primary frequency regulation capacity has not yet been adjusted, it prevents the system frequency from temporarily dropping to the first threshold of under frequency load shedding.

The magnitude of inertia in a power system is commonly quantified by the inertia time constant. The inertia of the entire power system can be defined as the sum of the rotational energies stored in all the rotating machines connected to the network, as shown in Equation (20).

In the equation is the rated capacity (MVA) of the synchronous generator, is the inertia time constant of the synchronous generator (s).

Calculate the center of inertia frequency as in equation (22) and its rate of change as in equation (23) from the output results.

In the equation is the synchronous machine end frequency

It is evident that the connection of renewable energy sources, which replace traditional synchronous generating units, leads to a decrease in the inertia level of the power system. By configuring SCs, the equivalent inertia of the system can be increased, which reduces the rate of frequency change and the maximum frequency deviation during the system's inertia response phase. This also delays the occurrence of the lowest frequency point, which is beneficial for improving the system's frequency dynamic response and promoting the stable operation of the power system.