1. Introduction

Advanced technologies have had a transformative impact on education. With the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) and extended reality, fields like learning, training, and human performance sciences are embracing innovative possibilities. When being used for human performance, extended reality–––a collective term for immersive learning technologies such as virtual reality, augmented reality, mixed reality, and the metaverse–––offers simulated, experiential, and in-situ learning experiences for knowledge construction and skills application [

1,

2,

3].

In addition to extended reality, since the introduction of large language models (LLMs; e.g., [

14]), a type of AI technologies, researchers’ interests of AI technologies have surged [

10,

40,

41]. The promising use of AI technologies gained wide attention in many different fields, such as health, medicine, and pharmacy [

18], business [

19], engineering [

20], and learning technologies [

10,

40]. In human performance, studies focusing on the use of applied AI technologies such as web-based chatbots have burgeoned. For example, Mendoza et al. [

11] proposed a model for developing chatbots specifically designed for educational purposes. Their model facilitates the creation of chatbots that address the needs of teachers, students, and administrative staff. They highlighted the utility of chatbots in various roles, such as providing information, handling frequently asked questions, offering feedback, and assisting with administrative tasks such as course registration and admission processes. Further, Ma et al. [

12] improved chatbot technology by designing and developing

ExploreLLM, which employs a schema-based structure rather than the traditional task decomposition method. This alternative approach enabled LLM technology to provide an additional dimension of capability, enhancing its effectiveness in facilitating reasoning and addressing complex problem-solving challenges encountered by users.

Although chatbots are useful and have a low barrier to application, the affordances of AI technologies and extended reality encompass well beyond chatbots alone. These technologies offer a broad range of possibilities, including immersive learning experiences, enhanced data visualization, and more sophisticated forms of human-computer interaction. Specifically, the potential of AI technologies can be significantly expanded through multimodal interactions that incorporate various sensory inputs and outputs, such as audio, images, and video. As vision-language models (VLMs) become more advanced and largely applicable [e.g., [

12,

13]], these multimodal capabilities enable richer, more interactive experiences, allowing users to engage with content in ways that closely mimic real-world interactions. This evolution in AI and extended reality could not only possibly enhance user experience but also set forth new avenues for innovation in learning technologies. In the design and implementation of learning technologies, multimodal interactions have been sought to support authentic experience [

15], embodiment for deep learning [

16], and learning analytics for deep insights about learning processes [

17].

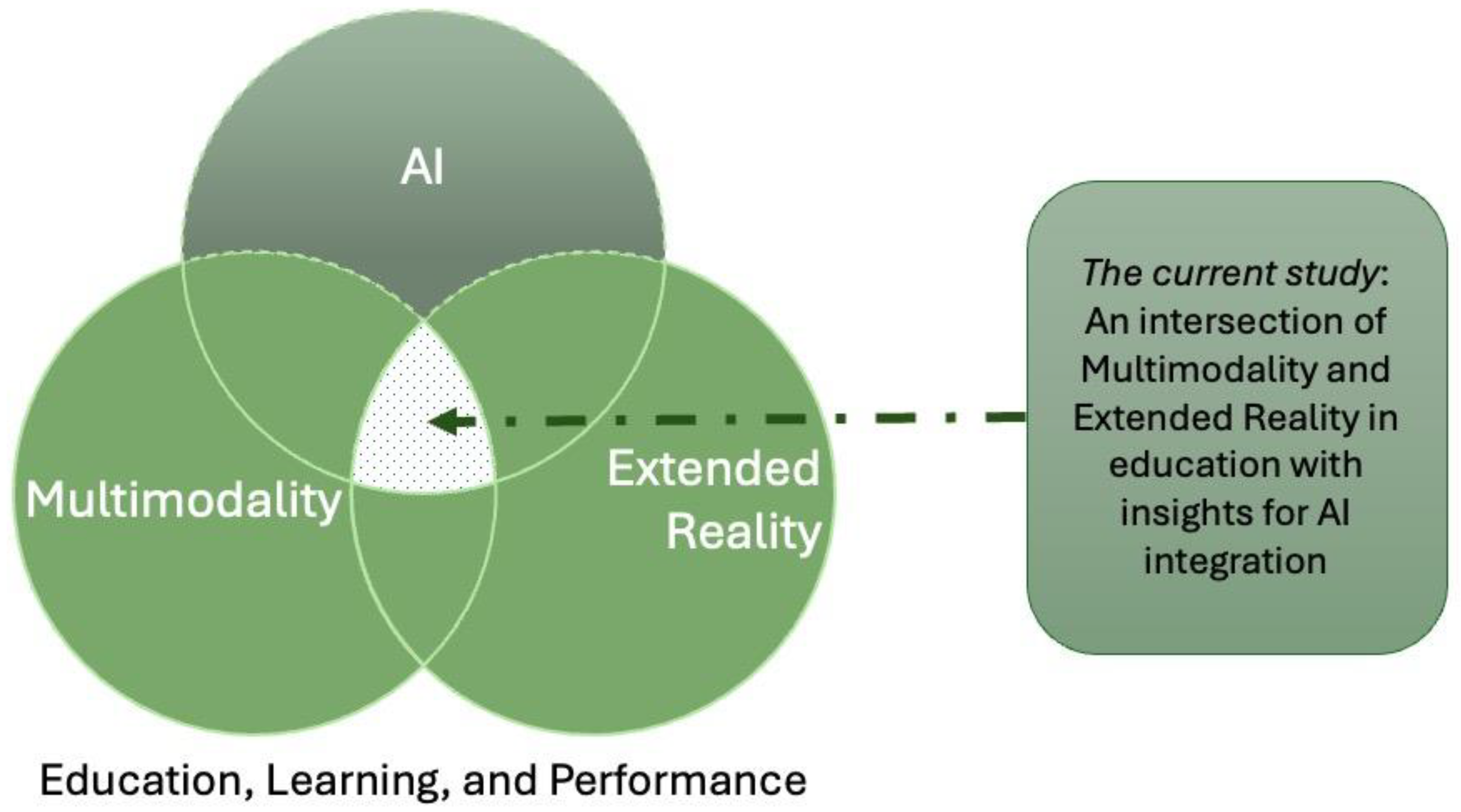

Research into the use of multimodal AI technologies in extended reality for enhancing learning is still in its infancy. Despite growing interest, the lack of understanding in this area may hinder researchers from designing and implementing effective multimodal AI technologies for learning in extended reality (

Figure 1). Several previous reviews have focused on specific, fragmented aspects of the field. For example, Reiners et al. [

4] reviewed literature in the intersection of AI and extended reality. The study indicated the applications and integrations of AI and extended reality, but not in multimodality. Rakkolainen et al. [

5] reviewed the scope of multimodal interaction technologies in extended reality, but less on education and the design implications. Numerous other reviews on extended reality or the metaverse in education lacked a specific focus on multimodality [

6,

7] or AI [

8,

9].

The purpose of this study is to provide insights into the use of multimodal AI technologies in extended reality for learning, training, and performance. We fulfill the purpose through a systematic literature review to explore the current status of the field and offer a future outlook for research. Based on the backgrounds, we asked the following research questions (RQs) in this study to guide our exploration:

What are the trends of multimodality in AI-supported extended reality for learning, training, and performance?

What are the goals of multimodality in AI-supported extended reality for learning, training, and performance?

What are the techniques and approaches to designing multimodality in AI-supported extended reality for learning, training, and performance?

What are the future directions of multimodality in AI-supported extended reality for learning, training, and performance?

In the following sections, we first provide the definitions of terms, and then present the method used, followed by the results, discussion, and conclusion.

1.1. Backgrounds and Definitions of Terms

Our study inquired into the integration of multimodality within AI-supported extended reality environments, specifically aimed at enhancing human learning, training, and performance outcomes. In this section, we focused on defining the key terms used throughout the paper and providing a comprehensive overview of the core concepts that underpin our study.

1.1.1. Extended Reality

As an umbrella term for various immersive technologies, extended reality blends the physical and virtual worlds, allowing people to live, work, learn, play, and engage in activities within these interconnected environments with varying degrees of immersion [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Driven by human curiosity, imagination, and the need for immersive technologies, the concept and development of extended reality have evolved through successive generations of progress. The concept and imagination of simulated reality, initially emerging as fiction [

22], evolved into the early development of virtual reality technologies [

23] and, later, the metaverse [

24]. With these different forms of extended reality, Milgram [

25] developed a taxonomy of the virtuality continuum for mixed reality, which spans from real environments to fully virtual environments. Specifically, extended reality offers simulated environments that meet the needs of safe training, such as complex or dangerous tasks like flight simulations for pilots, military exercises, and medical procedures. Additionally, it provides exciting entertainment and creative experiences for the gaming industry.

Aside from the virtuality continuum and technological representations of extended reality [

25], interactions within the simulation environment are also crucial [

3]. These include not only the user’s engagement with the environment and its elements but also social interactions between users facilitated by network technologies.

A comprehensive view of extended reality is embodied in the metaverse. Key aspects of the metaverse, such as user avatars, social interactions, persistence, and decentralization are crucial [

26,

27,

28,

61]. Weinberger’s definition of the metaverse offers a visionary conceptualization of the future world with extended reality. Weinberger [

27] (p. 13) maintained: “The Metaverse is an interconnected web of ubiquitous virtual worlds partly over- lapping with and enhancing the physical world. These virtual worlds enable users who are represented by avatars to connect and interact with each other, and to experience and consume user-generated content in an immersive, scalable, synchronous, and persistent environment. An economic system provides incentives for contributing to the Metaverse.”

1.1.2. Multimodality

Multimodality, in a broader sense, involves integrating multiple sensory modes of communication and interaction –– such as visual, auditory, and kinesthetic [

21,

29] –– and has become increasingly relevant in technologies used in everyday situations. By leveraging these diverse sensory modes, multimodality can enhance human reasoning and make transitions between different forms of representation more concrete and meaningful [

32].

When being discussed with extended reality, multimodality leverages multiple sensory inputs to create a more immersive and interactive experience. By engaging various senses simultaneously, extended reality environments may provide realistic simulations and interactions. This approach is particularly valuable in educational settings, training programs, and performance enhancement strategies [

30,

31]. Through the engagement of multiple senses and methods of interaction, multimodal learning environments can potentially cater to diverse learning needs, enhance engagement, and improve the retention of information. For example, a combination of visual aids, interactive simulations, and auditory instructions may create a richer learning experience, leading to more effective knowledge construction and skills development [

32,

44].

1.1.3. AI in Human Performance

AI in education encompasses a broad spectrum, including its use as a technology to enhance learning, its integration into curricula, and the study of AI literacy to develop the AI competencies of students and stakeholders. More specifically, AI for human performance focused on leveraging AI technologies to augment human capabilities or enhance human performance. The conceptualization of AI has evolved since 1950s, when the term was first coined [

33]. It has developed into a variety of applications, including complex decision-making systems [e.g., [

34]], data analysis [e.g., [

35]] and pattern recognition [

36]. When AI is used to enhance or augment human performance, it can take various forms, such as learning analytics that personalize learning [e.g., [

37]], diagnostic systems that assist in medical decision-making [e.g., [

38]], virtual companions or agents that provide support [e.g., [

42]], and autonomous systems that complement human tasks across different domains [e.g., [

43]]. These AI technologies can be integrated into the design and development of both extended reality and multimodality to achieve the objectives of these advanced systems. This integration could enhance user experiences and fosters more intuitive interactions across various platforms, allowing designers and developers to create experiential environments that respond dynamically to user inputs and maximize the effectiveness of extended reality applications. [

3]. However, the landscape and specific applications of AI in extended reality with multimodality remain ambiguous, and a scoping synthesis is lacking.

Given the emerging nature of research and development in the areas combining AI, extended reality, and multimodality for learning, training, and performance, this paper adopts a broad definition of AI. This broad definition is intended to encompass a wider range of relevant literature, as the field is still developing. Based on the literature [

40,

41], we defined AI as “any system or algorithm designed to execute tasks that normally necessitate human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, problem-solving, perception, and language processing.” Moreover, we also embrace a broad definition of human performance in alignment with our scoping purposes. In this paper, human performance includes a wide range of learning, training, human skills/competence improvements (including human behaviors, cognition, psychological performance, emotion, rehabilitation, and collaborative workplace).

2. Method

2.1. Systematic Scoping Review and Machine Learning-based Semi-automatic Approach

Given our purpose of this study, to gain comprehensive insights into the emerging field of multimodal AI technologies in extended reality for human learning, training, and performance, we conducted a systematic scoping review [

50]. According to Arksey and O’Malley, a scoping review is particularly valuable in emerging areas of research, as it helps to evaluate the current state of knowledge on the topic, map the existing literature, and understand the development of the field. Additionally, it can be used to identify critical gaps in research, providing a foundation for future studies and guiding the direction of more detailed investigations. We followed standard systematic review procedures outlined in the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA, [

51]) and adapted our approach with semi-automatic techniques using machine learning [

52] to gather insights from the searched articles. Specifically, we used text-mining and topic modeling for our purposes. Researchers have argued that integrating text mining and topic modeling [

53] in systematic reviews helps to gain preliminary insights and enhance the quality of mapping and synthesis [

54].

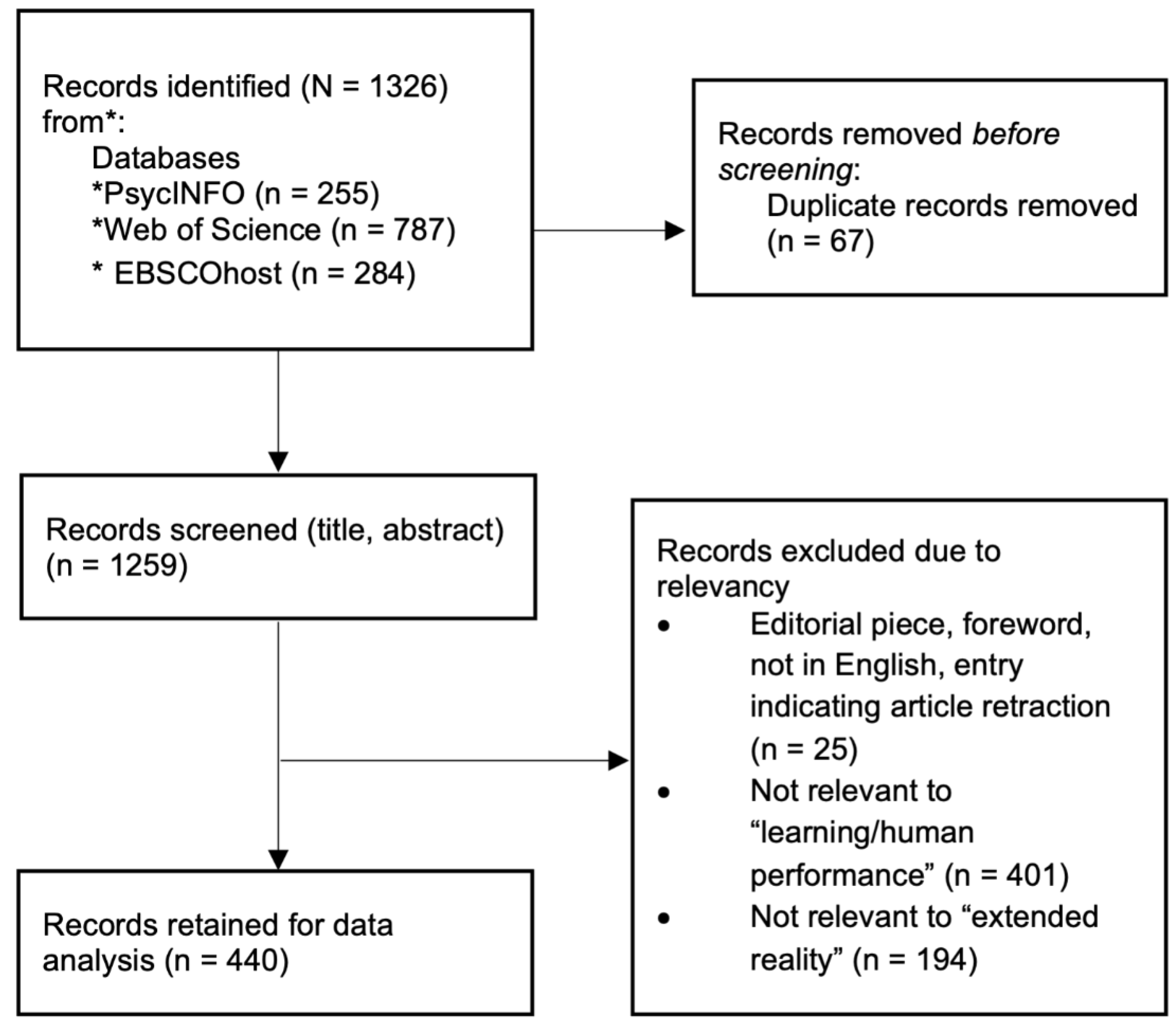

2.2. Literature Search

We searched relevant databases available and relevant to the field, including PsycINFO (n = 255), Web of Science (n = 787), and EBSCOhost (n = 284). We didn’t restrict our search to specific years or publication date as our goal was to capture the scope of the existing literature. We used the following search terms and keywords in each database, we present the rationale of the search terms and keywords in each category in

Table 1:

2.3. Procedures

We first collected the lists of the literature documents. With these documents, we identified duplications in the lists, and we removed them. The resulted comprehensive list of literature was then reviewed by humans following the inclusion and exclusion criteria (

Figure 2 showed the procedures). We also conducted the first preliminary text mining and topic modeling with the base of the collected literature to capture the general ideas of the documents based on the keywords and the abstracts and to support preliminary analyses [

53,

55,

56]. We reported the details of the machine learning-based semi-automatic approach for text mining and topic modeling in the following sections. With the pre-screening dataset, we applied inclusion and exclusion criteria (see

Table 2 for details). The two major categories are the topic relevancy and article characteristics. Specifically, for topic relevancy, we also excluded instrument validation studies, studies with a sole outcome focus of technology acceptance; because these studies did not fit our purposes of understanding how the technologies are being used for learning, training, and performance. In addition, we excluded serious games, videogames (but not “virtual reality gameplay”) in the current study because we would like to put an emphasis on “extended reality,” in alignment with our discussions in

Section 1.1.1. Further, we excluded studies that simply described extended reality as a multimodal experience without specifying the technologies or applications involved (i.e., only described the “extended reality” used as “multimodal”).

2.3.1. Machine Learning-Based Semi-Automatic Approach

The text mining and topic modeling processes were being executed in Python using several packages, including NLTK (Natural Language Toolkit), scikit-learn, and Gensim. We followed standard text-mining and topic modeling procedures to process the documents. First, we removed the special characters and extra spaces. We then converted the keywords in the documents to lowercase to ensure that the variations (e.g., “Metaverse,” “metaverse,” or “METAVERSE”) are treated as the same word, avoiding unnecessary duplicates and noise, as well as improving consistency and tokenization. We then processed “lemmatization,” of which the words were reduced to their base or root form (e.g., “sensing” became “sense”). Next, a Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) vectorizer was applied, with the number of features capped in 2000 [cf. [

59]]. This step transforms the text into numerical values, allowing for the identification of important terms across the corpus. This limit on features ensured the most significant terms, based on their frequency in documents and across the dataset, are included, while reducing dimensionality and improving computational efficiency. Common stop words were excluded during preprocessing to enhance the relevance of selected features. Following the vectorization of the text using TF-IDF, we also created a corpus by converting the documents into a bag-of-words (BoW) representation. With the BoW, a Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) algorithm was applied to uncover latent topics within the document corpus.

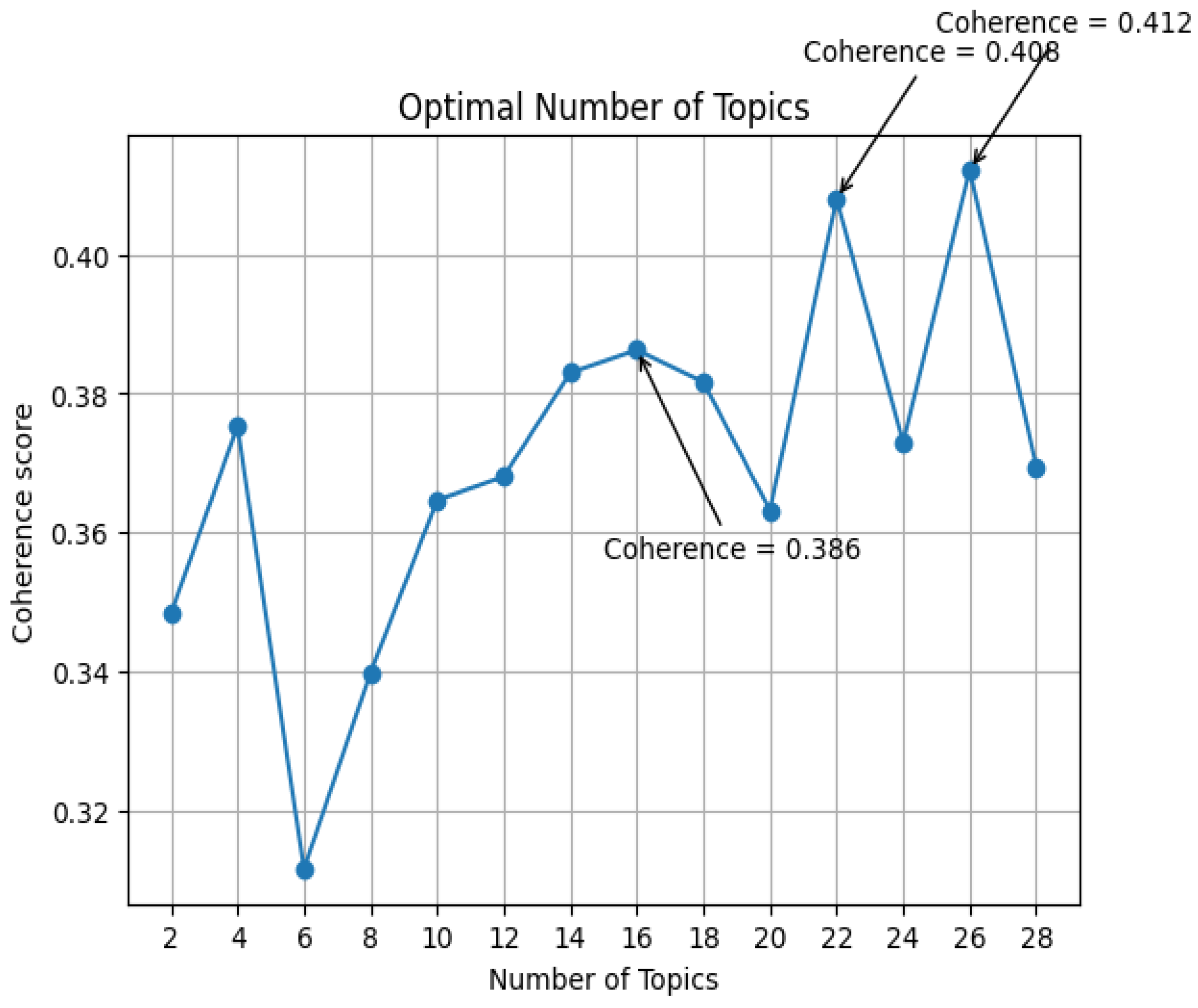

To determine the optimal number of topics, we used the coherence measure in “

Gensim” (Generalized Similarity Measure) library to calculate the coherence value. The coherence measure evaluates how semantically consistent and meaningful the words within a topic are. A higher coherence value indicates that the words in the topic frequently appear together in the same documents and are more likely to form a coherent topic. The coherence measure of

Cv (Coherence value), based on the normalized pointwise mutual information (NPMI) and the cosine similarity, was used by following the pipelines introduced in Röder et al. [

57]. We chose

Cv measure over other coherence measures such as UMass-coherence or UCI-coherence due to its robust normalization, which provides a consistent and interpretable score across different corpora. In addition, normalization helped mitigate the impact of corpus size and word frequency variations, aligning well with our goal of using it in a semi-automated procedure that incorporates human-in-the-loop analysis. our purpose to use it as semi-automated procedure with humanin-the-loop analysis. The formula for calculating

Cv is as follows see [

57,

58], where

is the number of unique word pairs in the topic (which is

),

is the joint probability of the words

and

co-occurring,

and P(

) are the individual probabilities of

and

, respectively, and ε is used as a smoothing parameter to avoid zero probabilities.

This approach was conducted twice, first with the

preliminary, pre-screening dataset (n = 1259), and then with the

final included dataset after screening (n = 440). With the

Cv coherence score, the optimal number of topics for the

pre-screening dataset would be 14 (Coherence = 0. 449), while eight topics and 24 topics yielded the same coherence score of 0.448, we presented the information in

Figure 3. For the distribution of dominant topic in the 14-topic solution, please see

Figure 5.

Figure 3.

Optimal number of topics for the pre-screening dataset.

Figure 3.

Optimal number of topics for the pre-screening dataset.

Figure 4.

Optimal number of topics for the dataset of final included studies.

Figure 4.

Optimal number of topics for the dataset of final included studies.

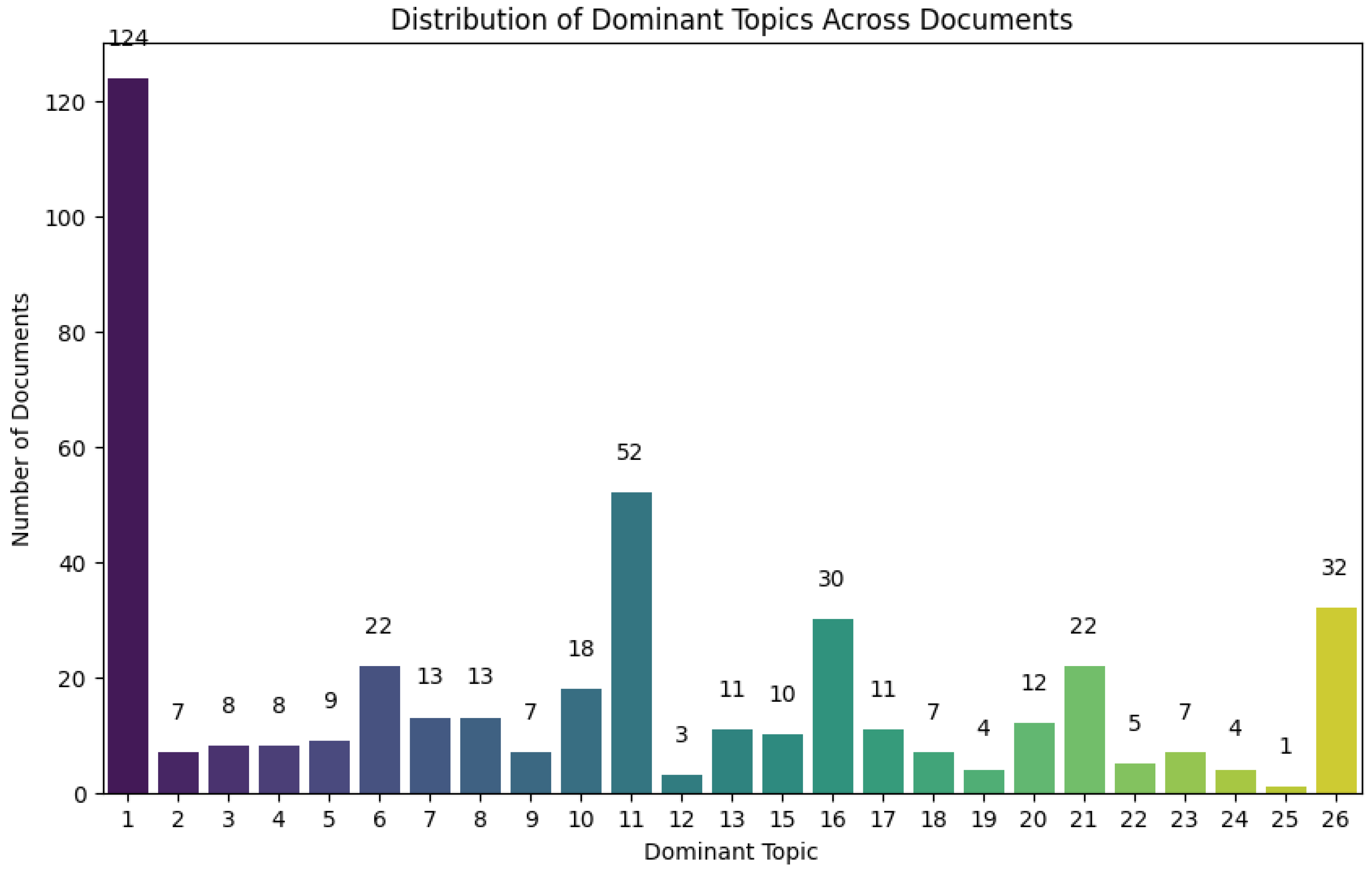

Figure 5.

Distribution of dominant topics across documents from the pre-screening dataset.

Figure 5.

Distribution of dominant topics across documents from the pre-screening dataset.

Figure 6.

Distribution of dominant topics across documents from the dataset of final included studies.

Figure 6.

Distribution of dominant topics across documents from the dataset of final included studies.

2.3.2. Analysis Approach for the Pattern Review

To complement the findings from text mining and topic modeling, we conducted comprehensive human reviews aimed at uncovering nuanced insights and implications. Our pattern review was grounded in the results derived from these computational methods, ensuring a robust analytical framework. We maintained a detailed code sheet that cataloged essential information, including article titles, abstracts, publication years, authors, keywords, and links to the full-text articles. Additionally, we organized the machine learning-classified documents according to the dominant topics identified, specifically adopting the twenty-six-topic solution, the final included studies (see

Figure 6).

Throughout our open coding process, patterns related to topical focus emerged and were further refined through iterative rounds of review. This process involved constant comparison [

49] between the outputs of the machine learning analyses and the insights gained from human reviews. By integrating these two approaches, we aimed to achieve a richer understanding of the data, ultimately allowing for a more comprehensive exploration of the themes and implications present in the literature.

3. Results

3.1. Insights from Text Mining and Topic Modeling

To determine the optimal number of topics, we used the

Cv coherence score described in

Section 2.3.1. The optimal number is calculated to be 26 topics (Coherence = 0. 412), closely followed by 22 topics (Coherence = 0. 408) (see

Figure 4). With the 26 topics solution, we examined the dominant topics among these 26 topics.

Figure 6 showed the distribution of dominant topics across documents. Top ten dominant topics are Topic One, Topic Eleven, Topic Thirty-Six, Topic Sixteen, Topic Six, Topic Twenty-One (they are tied in the number of documents/papers, n

Topic Six and Twenty-One = 22), Topic Ten, Topic Seven, Topic Eight (they are tied in the number of documents/papers, n

Topic Seven and Eight = 13), and Topic Twenty. In comparison to the pre-screening dataset (

Figure 5), the topic modeling in the final included study dataset (

Figure 6) resulted in a more distinguished distribution of dominant topics.

We summarized the key words in the top ten topics in

Table 3. The keywords of the most dominant topic (i.e., Topic 1) indicated that, in terms of extended reality technologies, most studies focused on “virtual reality,” followed by “augmented reality” (e.g., Topics 11, 26) and “mixed reality” (e.g., Topic 32). While the general term “multimodal” (e.g., Topics 6, 13, 16) was listed, text mining also yielded some keywords more granular in specificity. That is, several keywords provided insights on how “multimodality” was enacted in the included studies, e.g., “haptic,” “visual,” “time,” “assembly,” “sensing,” “eeg,” “emotion,” “brain,” “gaze,” and “eye tracking.” The keywords indicated that the studies utilized various technologies to detect different external signs of human experiences, such as emotions, eye movements, physical interactions, and brain activity. The AI technologies employed were aligned with the use of these multimodal technologies, with related keywords including “vision,” “recognition,” and “robot.” It also revealed that AI technologies were being adopted as a machine learning approach to validate the “accuracy” of evaluation and training results (Topic 21).

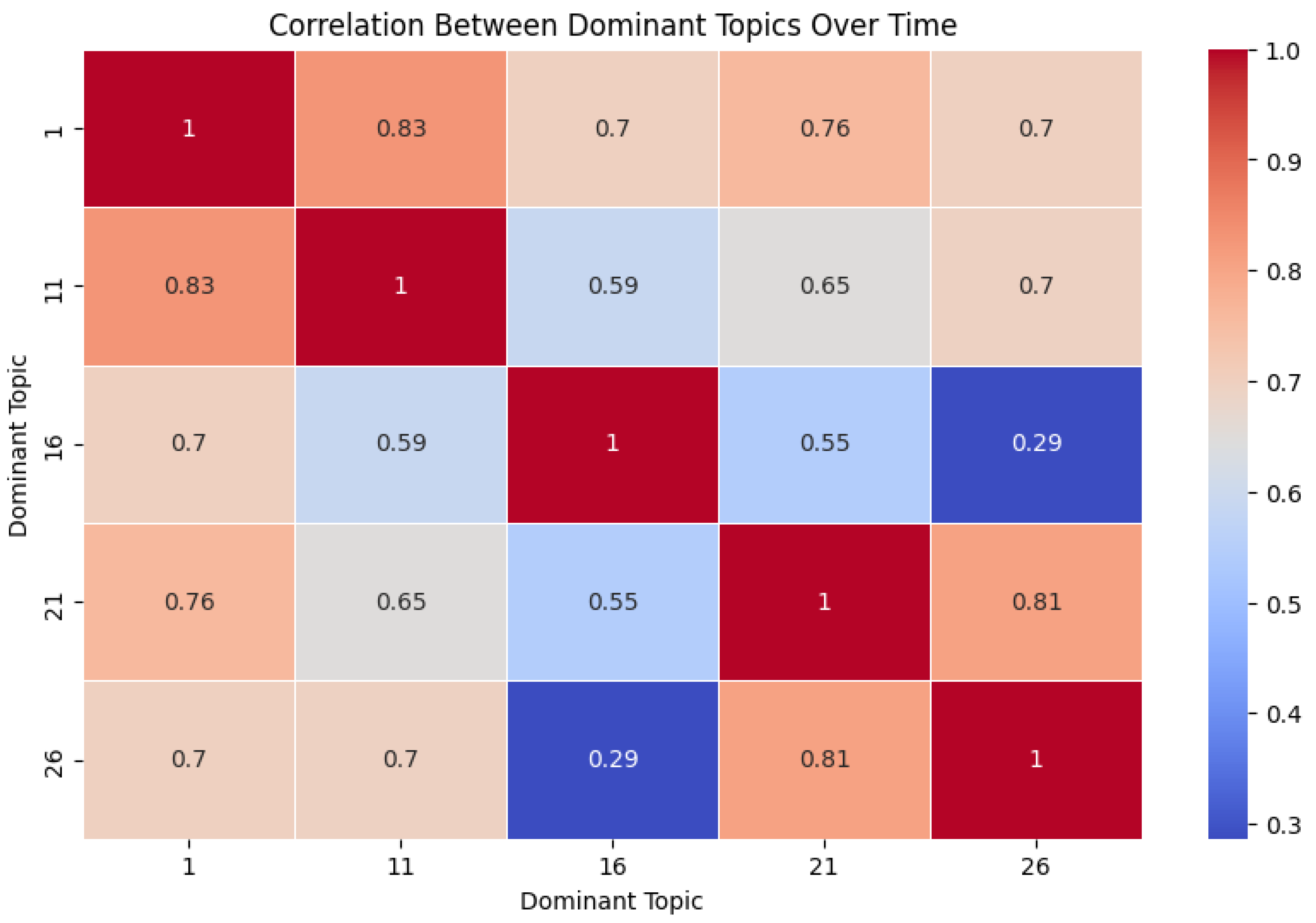

To gain further insights into the top five topics, we conducted a correlation analysis between them (see

Figure 7). The results indicated that the strongest correlation was between Topics One and Topic Eleven (r = 0.83), followed by Topics Twenty-One and Twenty-Six (r = 0.81). By examining the keywords and content of these topics, we can reason an emphasis on “interaction” and the use of extended reality—particularly virtual reality and augmented reality—to enhance learning through usability study techniques. Additionally, we can observe that the technologies used to capture these interactions varied, including eye tracking, brain tracking, hand tracking with haptic interfaces, and emotion detection.

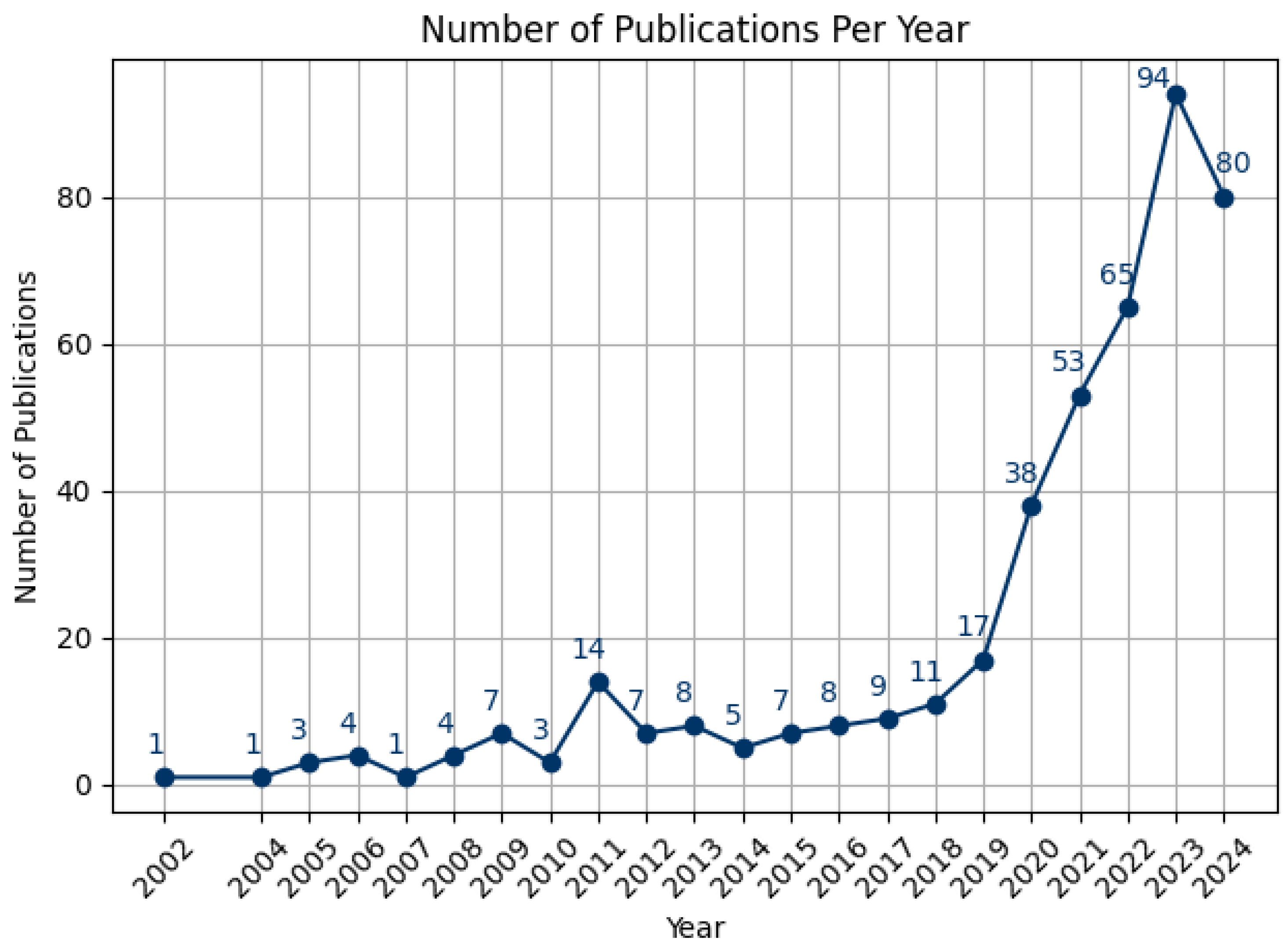

The number of publications each year reflected the trends of the topic over time. Research on extended reality with multimodal AI technologies for human performance began to emerge around 2002, fluctuated for more than a decade, and experienced a notable upswing in the 2020s (see

Figure 8). This increase was likely driven by the rise of LLMs, facilitated by advances in big data availability and computing power, and aligns with recent trends in AI technology development and adoption. It is worth noting that the literature search for this review was conducted in mid-2024, and by that time, 80 papers had already been published that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, approaching the total of 94 papers published in all of 2023.

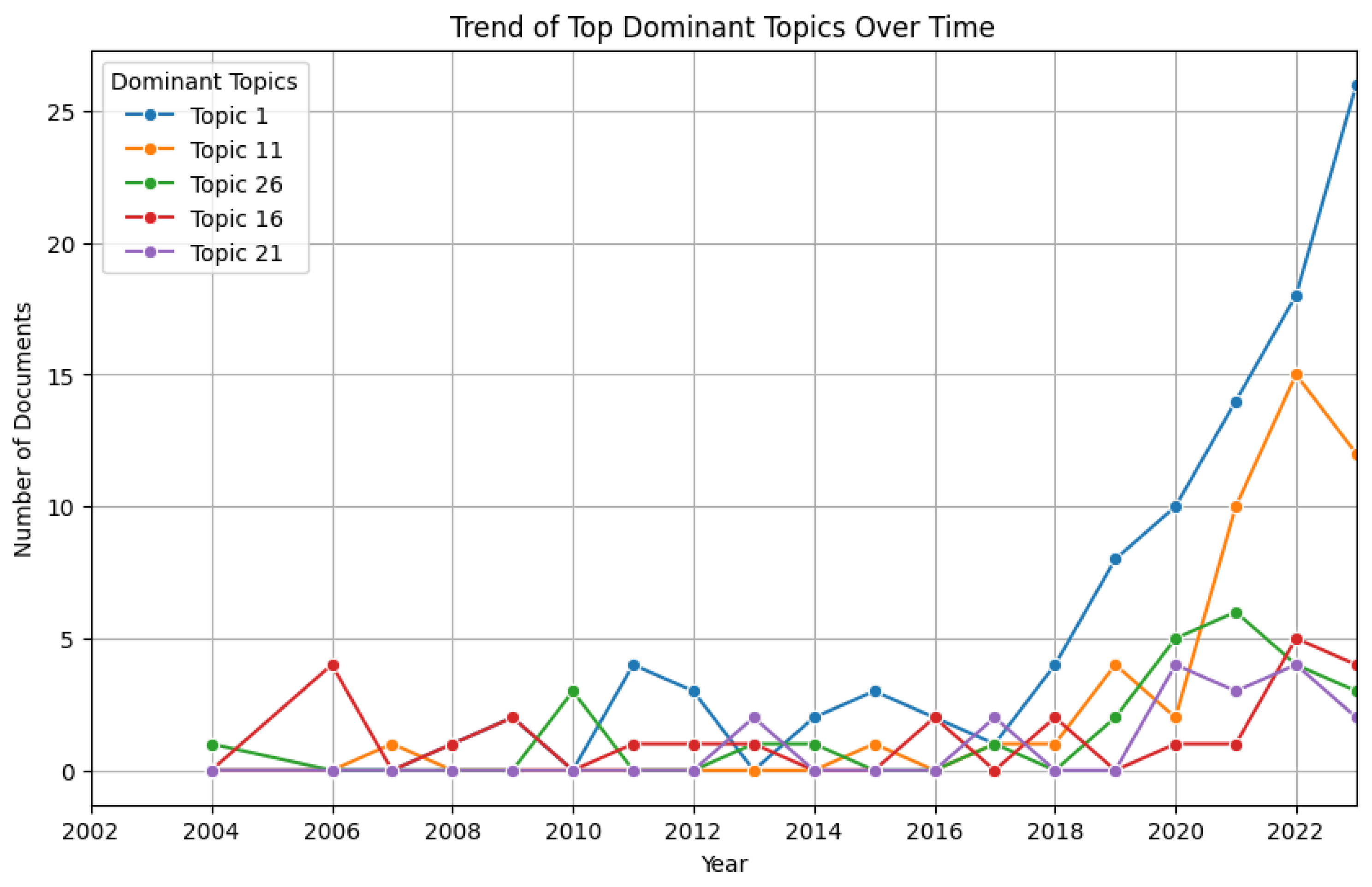

Furthermore, we selected the top five topics and illustrated the trends of these dominant topics over the years (see

Figure 9). The trends align with the overall trajectory, with Topic One showing a drastic increase starting in 2018. Moreover, initially, Topic Sixteen ranked lower than Topics Twenty-One and Twenty-Six. However, in 2022, Topic Sixteen crossed over to surpass both Topics Twenty-One and Twenty-Six, which experienced a decline. This emerging trend is not yet very pronounced and requires further observation over additional years for validation. It is essential to recognize that Topics Twenty-One and Twenty-Six contains technologies that are more resource-intensive.

3.2. Pattern Review

In addition to the text mining and topic modeling results, we also analyzed the pattern and information from the included studies, with subtle, nuanced, and informative observations from the literature to supplement the findings from text mining and topic modeling. In the following sections, we presented the “Goals and Outcomes,” “ It is interesting to note that several included studies exhibit crosscutting characteristics. For example, the multimodal techniques used are also associated with specific types of AI technologies. Although we discussed

3.2.1. Goals and Outcomes of AI-Supported Multimodal Extended Reality for Human Performance

To understand the goals of multimodality in AI-supported extended reality, we examine the subjects and content areas of the included studies. Specifically, rehabilitation [

67,

76], medical training [

65,

78], workforce training (including manufacturing performance) [

68,

69], language learning [

70,

77], history (cultural heritage) [

71,

73] and STEM (including chemistry learning, molecular structures) [

74,

75] are the subjects identified to be relevant in the areas of multimodality, AI, and extended reality for human performance. This identification highlighted the specific outcomes and areas where AI-supported extended reality can be productively implemented with multimodality.

After mapping these areas, it became evident that the key affordances of this intersection of technologies may lie in enhancing experiential learning, fostering embodiment, and leveraging smart adaptive technology for personalized learning. By integrating these elements, it is possible to create more immersive and tailored learning experiences that respond dynamically to individual needs. In a particular example, “rehabilitation” can greatly benefit from multimodal feedback associated with movement execution. For example, Ferreira dos Santos [

76] reviewed the movement visualization techniques in virtual rehabilitation environments for individuals’ movements and motor learning outcomes. The review offers compelling suggestions for using multimodal extended reality in rehabilitation.

3.2.2. Disentangling the Dynamics of User Interactions in Virtual Environments with Multimodal Strategies

There is still a varierty of facets that researchers used to frame “mulitmodality” in VR with AI approaches, in practice, sometimes, multimodality could indeed inlcude “bimodality,” e.g., text and image, or text and video, it is rare for an application to contain more than two modalities simultaneously. An incredible change inlcudes the applications of context-aware, environment-sensitive spatial-sound computing used in extended reality. For example, Rubin and colleauges [

65] discussed the use of extended reality, with either typical human anatomy models or tailored patient-specific models for preprocedural planning and education in anaesthesiology. They suggested that “multiuser shared spaces” is an innovative affordances of extended reality, allowing users to engage with holographic avatars in shared virtual environments. This capability, when paired with tools for preprocedural planning, could facilitate collaboration among distant colleagues in ways that traditional video conferencing cannot achieve, calling for the advancement in spatial computing. In a similar vein regarding spatial computing, Kim et al. [

66] investigated robot-assisted surgery using a virtual vision platform (VVP) to enhance surgical performance. They found no significant difference in overall performance between the VVP and the conventional stereo viewer (SV) vision system. However, participants demonstrated better performance on one specific metric—the craniovertebral angle—when using the VVP. Additionally, participants expressed a positive view and preference regarding their experience with the VVP.

Indeed, one characteristic of the “metaverse” is the social interactions and collaborations enabled by the technology [

26,

27,

28,

61]. Interestingly, although “metaverse” was not on the keyword list revealed by text mining and topic modeling, several studies aim to foster collaborations and social interactions in extended reality through multimodality, using intelligent technologies to enhance human performance. To enhance remote collaborative work, Wang and colleagues [

60] designed a virtual reality (VR)-Spatial Augmented Reality (SAR) system to investigate how haptic feedback can be used to enhance collaboration on physical tasks among users in different locations. Another study [

62] also explored remote collaboration in mixed reality using multimodal sensing technologies for physical interaction (i.e., gesture and head pointing). Both studies find common ground in the multimodal approaches used in extended reality [

60,

62]. Specifically, they discussed the established concept of “annotation” in remote multimodal task collaboration, where 2D markers can be transmitted remotely in an extended reality interface. Furthermore, both studies [

60,

62] built on existing research focused on using “annotation” by suggesting that innovative tangible haptic feedback [

60] and gesture- and head-based interactions [

62] may better enhance outcomes such as enjoyment, confidence, and user attention in these extended reality environments than the “annotation” approach. [

60,

62].

In addition to the multimodal interactions enabled by embodied experiences in extended reality, the included studies also utilized multimodal inputs using mouse and keyboard, speech, and image data points [e.g., [

63,

64]]. Plunk et al. [

63] explored the use of semi-supervised machine learning to study interpersonal social behaviors for individuals with autism spectrum disorder in virtual teamwork-based collaborative undertakings. Another multimodal approach involves using audio-tactile cueing to assist patients with spatial attention deficits [

78]. This technique is specifically designed to enhance attention in such contexts [

78,

79]. The combination of audio and tactile cues is provided via a head-mounted display equipped with a cushion featuring six-coin vibrators evenly placed on the forehead, along with over-ear headphones.

3.2.3. Synergistic Multimodality with Emerging AI Technologies Using Machine Learning, LLMs, and VLMs

In addition to the focus on multimodality for the pattern review, the various AI technologies being used in the included studies also emerged as an interesting area of focus. In the current list of studies, AI technologies have been used with machine learning techniques, LLM and VLM architectures. We recognized that VLM represents an important and promising future direction, as techniques from this area can enhance the functionality of AI-supported multimodal extended reality [

81,

82]. However, its application in the included studies remains limited and is still in the early stages of development.

Machine learning and deep learning are classic and widely observed techniques of AI employed in the included studies. The machine learning techniques utilized in these studies are diverse in their applications, ranging from biodata classification and detection [

84,

85] to enhancing multimodal embodied interactions and movements [

83]. This variety highlighted the versatility of machine learning, demonstrating its capability to address different challenges within the area of AI-supported extended reality. By employing these techniques, researchers developed more sophisticated systems that better understand and respond to human behaviors and interactions in complex environments. More specifically, Rahman [

85] used multimodal physiological data (e.g., electroencephalogram and heart rate variability) to train machine learning models for designing virtual reality exposure therapy. This approach allows users to practice responding to anxiety-evoking stimuli in a virtual environment, gradually helping them cope with stress and anxiety. Specifically, the machine learning model can detect anxiety-induced arousal in users, triggering calming activities in the virtual reality setting to assist them in managing and alleviating their distress.

In another study, Alcañiz Raya [

83] designed a virtual reality system with machine learning capabilities and a depth sensor camera to capture the body movements of children with autism spectrum disorder. Their results revealed that the machine learning classification accuracy for head, trunk, and feet movements was above eighty-two percent, higher than arms and legs (between sixty and seventy percent). Additionally, the system incorporated visual, auditive, and olfactory stimuli. The visual condition had the highest accuracy rate, followed by the visual-auditive stimuli and the visual-auditive-olfactory stimuli. A unique modality incorporated in this study [

83] was olfactory stimuli. Using a wireless freshener with a programmable fan, the system can deliver twelve scents with adjustable duration and intensity. One example of a delivered scent is butter, which represents the smell of a muffin. To realize a fully immersive system using extended reality, the incorporation of olfactory stimuli is a critical area of research and development.

Machine learning and deep learning have laid the groundwork for the emergence of LLMs. For language-related tasks and text-based modality, transformer-based models enhance human performance. In workforce enhancement, Izquierdo-Domenech et al. [

80] embedded speech recognition and LLM in augmented reality to process information in the environment (e.g., in a shop) so that expert knowledge can be used to support shop floor operators. This technique is an innovative way for technical documentation in the workforce. Noting that one essential component in these LLM-enabled architectures and applications is the expert knowledge base [

64,

80].

Another novel study combined multimodal, transformer-based models, and 6G communication technology to improve human experience [

86]. Chen et al. [

86] created a cross-modal intelligent system in metaverse using technologies such as transformers and graphic neural networks (GNNs). Their design addressed issues including semantic misinterpretation, transmission noise, and illusion creation. Their intelligent cross-modal graph semantic communication approach integrated modalities of text, audio, image, and haptics. These studies [e.g., [

83,

85,

86]] addressed current issues of inauthenticity and aim to enhance human experience in extended reality through multimodal approaches and AI technologies.

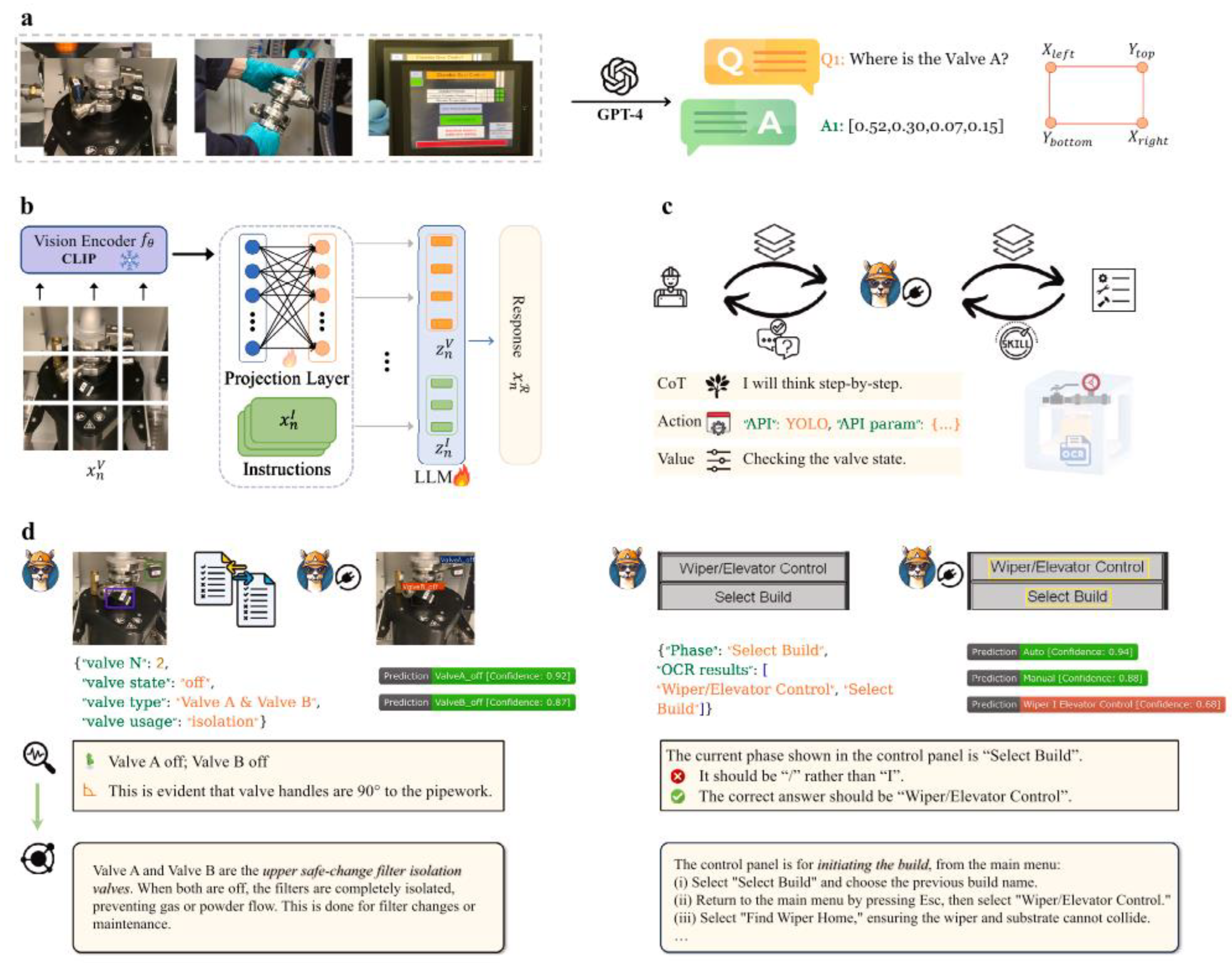

Building on the discussion of GNNs, VLMs, though still emerging and relatively rare in our included studies, represent a valuable AI technology that can enhance interactivity and improve the modality experience in extended reality. For the purpose of improving metal additive manufacturing (AM) training in augmented reality, Fan and colleagues [

82] integrated different tools to design a VLM-centered digital twin framework. The VLM leveraged was Generative Pretrained Transformer 4 Vision (GPT-4V) [

87]. Similar to the training of LLMs, Fan et al. [

82] implemented a two-stage training process for their VLM system. They began with pre-training for feature alignment, followed by fine-tuning for “instruction following and knowledge injection” (p. 261) (see

Figure 10). In

Figure 2, b, CLIP was developed by Radford et al. [

88] served as the foundational neural network architecture for computer vision tasks, the use of LLM was based on Chiang’s [

89] open-source model

Vicuna. Through this integration, Fan et al. [

82] aligning text and image features during the VLM training. Specific to their domain (an expert system in manufacturing training) [

82], the discipline-specific interactions were made possible by the use of You only Look Once (YOLO) API [

90] and Character Region Awareness for Text Detection (CRAFT) [

91,

92]. Despite presenting this novel digital twin system designed to provide immersive manufacturing training through the integration of VLMs and augmented reality, Fan et al. [

82] also highlighted inherent challenges associated with VLMs. These challenges include the advocacy for using video training data instead of static images for dynamic scenarios, as well as VLMs’ limitations in accuracy when decoding 3D content and understanding spatial relationships.

3.2.4. Fostering Engaging, Interactive and Immersive Human Experiences through Ambient Intelligence

Ambient intelligence is another concept emerged in the applications of AI in extended reality for learning [

93]. One characteristic of extended reality is the blend of virtual and physical environments, which creates a world with “ambient intelligence.” To elaborate, the idea of "ambient intelligence" relates to environments that are responsive to the presence and needs of users, which can work together with extended reality technologies. While ambient ingelligence is not pervasive yet in the included studies, it has been envisioned, conceptualized, and studied for about a decade now [

93,

94,

95]. Ambient intelligence seamlessly integrates with agents, robotics, and extended reality to create immersive and responsive environments that enhance user experiences. Intelligent agents serve as the cognitive backbone of ambient intelligence, enabling systems to perceive, analyze, and respond to user needs in real time. Robotics adds a physical dimension, allowing for interactive and tangible assistance in various settings, from smart homes to healthcare facilities. Meanwhile, extended reality–––encompassing virtual, augmented reality, and metaverse–––offers new avenues for user engagement, transforming how individuals interact with their surroundings. These technologies create a holistic ecosystem where users can benefit from personalized, context-aware interactions, making everyday environments more intuitive and supportive. This synergy not only enhances efficiency and convenience but also opens up innovative possibilities for learning, collaboration, and human performance. Ambient intelligence constitutes mainly with “sensors, sensor networks, pervasive computing, and AI” [

94] (p. 277). In Godwin-Jones’s [

93] work, the author discussed ambient intelligence’s role in language learning through the theory of sociomaterialism [

96], which explained the interrelationships and entanglments between materials worlds, semiotics, and humans. The author also offered several examples of the devices that can entail ambient intelligence such as smart wristbands, apple watches, cameras, and smart speakers.

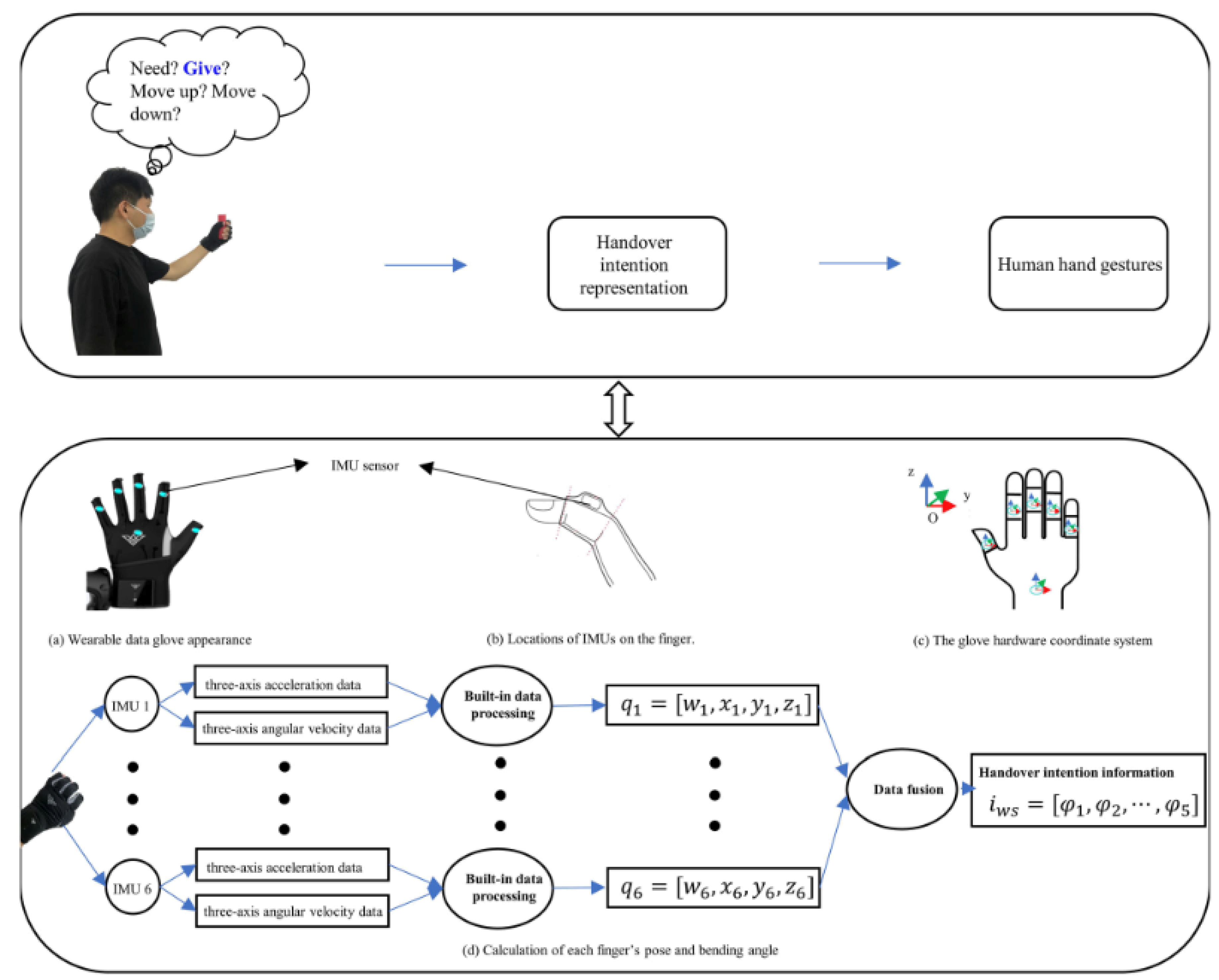

Wearable data gloves [

69,

72] is another interesting use of AI-supported multimodal interactions that can be considered as part of the ambient intelligence devices. Focusing on human–robot handover task performance in collaborative environments, Zou et al. [

72] demonstrated the use of wearable data gloves in tandem with augmented reality to teach robot on these tasks (

Figure 11). This design and development have the potential to advance human-robot collaboration to improve human performance in extended reality. Likewise, in another study, Hughes and colleagues [

69] designed a low-cost wearable glove, called MemGlove, using technologies such as knitted resistive sensing and fluidic pressure sensing architecture to support user sensing (e.g., pose/gesture and heart rate), environmental sensing (e.g., sensing temperature, stiffness, and force), and task classification (e.g., object detection and handwriting). Their innovative architecture (i.e., combining resistive and fluidic sensing in wearable gloves) have implications for complex multimodal interactions in extended reality. In particular, the wearable glove has exciting applications for embodied interactions in immersive virtual environments.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review of current status and future outlook applying a machine learning-based semi-automatic approach, we investigated the scope and landscape of the intersection between multimodality, AI, and extended reality in relation to human performance. We employed text mining and topic modeling to map the current literature in this area. Additionally, we conducted a pattern review to supplement our findings and delve deeper into the goals and techniques of the included studies related to multimodal AI-supported extended reality.

4.1. The Trends and the Goals (RQs 1 and 2)

The trend over the past years, specifically, five years, indicates a noticeable increase in attention and investment in research in AI-supported multimodal extended reality. While versions of extended reality technologies are not new and have been around for generations [

22,

23,

24], the integration of transformer-based AI (i.e., LLM, VLM) and advanced technologies for multimodal enhancement represents a more recent innovation. This surge in attention and investment is possibly further fueled by the global pandemic, which has highlighted the importance of remote immersive technologies, as well as by technological advancements driven by the commercial sector. For instance, Facebook's rebranding as Meta in 2021 [

97] underscored this shift. These factors may help explain the growing interest and increased number of publications in this field. This growing trend also align with findings from other systematic reviews focused on subset dimensions such as multimodality [

98], metaverse in education [

99], and AI in education [

40,

100]. As the trend continue to grow, researchers and developers should continue to approach AI-supported multimodal extended reality with caution and responsible plan and design [

101,

102] as these technologies are prone to systematic bias, misuse, or overestimated benefits relative to the risks [

102].

Another intriguing finding regarding the goals and outcomes of AI-supported multimodal extended reality is the context, setting, and discipline that scholars and practitioners have focused on. Notably, due to the unique characteristics of multimodality and extended reality, rehabilitation has emerged as a prominent area of application, e.g., [

67], alongside the well-established field of medical training, see [

40]. Additionally, workforce learning and training, particularly in manufacturing, have seen extensive and growing applications. Interestingly, collaboration has become a notable outcome in workforce learning and training within industry. This finding aligns with the characteristics of the metaverse [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48], where shared and social experiences are essential in this type of virtual environments. Furthermore, it suggests ongoing research efforts to reimagine the future workplace and human performance.

4.2. The Techniques and Apporaches, and Future Directions (RQs 3 and 4)

The topics analyzed highlighted the scope of multimodal techniques, the types of extended reality in use, and, to some extent, the applications of AI technologies present in the current set of literature. Traditional multimodal techniques were identified through text mining and topic modeling, while the pattern review revealed additional novel techniques. While traditional methods such as eye, hand, and brain tracking, as well as emotion analytics, are valuable, the pattern review also distilled that olfactory stimuli could represent an encouraging future direction for research [

83]. The exploration of senses, in addition to eyes and haptics, could enhance extended reality by providing a more immersive and comprehensive experience for human performance.

Several emerging techniques are shaping future directions for the design and development of immersive and comprehensive experiences aimed at enhancing human performance. These techniques fall under the overarching concept of ambient intelligence, leveraging advanced technologies such as environmental sensors and wearable devices [

69,

72,

93]. Since the introduction of computer applications utilizing large language models (e.g., ChatGPT), discourse surrounding generative AI has intensified, spanning different disciplines [e.g., [

103,

104,

105]], particularly in the context of text-based applications. However, the application of AI in extended reality with multimodality is essential for driving radical innovations in how humans live, work, and play in alternative environments [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48], enhancing performance, well-being, and lived experiences. To this end, the integration of ambient intelligence is pivotal despite the need for tremendous investment in research and development.

Finally, methodologically, the current review demonstrated that a semi-automatic approach, which supplements machine learning analysis with human reviews, offers a promising direction for future research focused on collaboration between humans and machines [

52,

105,

106]. While the accuracy of machine learning for analyzing and reviewing literature is constantly improving, human analysis and reasoning remains critical, as machines have limitations in distinguishing nuanced differences and charting future directions. Furthermore, from a human-centered perspective on the use of machine intelligence, decision-making and future planning and orientation should rest with humans, rather than being replaced by machines or AI [

101,

107].

5. Conclusions

In closing, this systematic review has provided useful and valuable insights into the intersection of multimodality, artificial intelligence, and extended reality, particularly regarding their implications for human performance. Our findings indicate a significant upward trend in research and investment in AI-supported multimodal extended reality over the past five years, driven by technological advancements and a heightened focus on immersive remote technologies. As demonstrated, the integration of traditional multimodal techniques alongside emerging innovations, such as olfactory stimuli, offers exciting avenues for enhancing user experiences. Moreover, the overarching concept of ambient intelligence plays a critical role in shaping future developments; however, it requires substantial investment in research and development to foster continued innovation while also addressing potential biases and the overestimation of benefits. Methodologically, our use of a semi-automatic approach highlights the importance of collaboration between human and machine analysis in systematic reviews. Considering future possibilities, it is essential for researchers and developers to approach these technologies with caution and responsibility, ensuring that they realize their full potential in transforming how we live, work, and engage in diverse environments.

Author Contributions

C-P. Dai: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. A. Nuder: formal analysis, visualization, writing—review and editing.

Acknowledgments

We thank the support from Hawaiʻi State Department of Education and Hawai'i Education Research Network.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dai, C. P.; Ke, F.; Zhang, N.; Barrett, A.; West, L.; Bhowmik, S.; Southerland, S. A.; Yuan, X. Designing conversational agents to support student teacher learning in virtual reality simulation: a case study. In Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2024, pp. 1-8.

- Dai, Z.; Ke, F. ; Dai, C-P.; Pachman, M.; Yuan, X. Role-play in virtual reality: a teaching training design case using opensimulator. In Designing, Deploying, and Evaluating Virtual and Augmented Reality in Education; Akcayir, G., Demmans Epp, C., Eds.; IGI Global, 2021; pp. 143–163. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, C-P. Applying Machine Learning to Augment the Design and Assessment of Immersive Learning Experience. In Machine Learning in Educational Sciences; Khine, M. S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 245–264. [Google Scholar]

- Reiners, D.; Davahli, M. R.; Karwowski, W.; Cruz-Neira, C. The combination of artificial intelligence and extended reality: A systematic review. Front. Virtual Real. 2021, 2, 721933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakkolainen, I.; Farooq, A.; Kangas, J.; Hakulinen, J.; Rantala, J.; Turunen, M.; Raisamo, R. Technologies for multimodal interaction in extended reality—a scoping review. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro de Oliveira, T.; Biancardi Rodrigues, B.; Moura da Silva, M.; Antonio, N. Spinassé, R.; Giesen Ludke, G.; Ruy Soares Gaudio, M.; Mestria, M. Virtual reality solutions employing artificial intelligence methods: A systematic literature review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, K. L.; Smith, S. P.; Bailey, J. D.; Krynski, B. Integrating biofeedback and artificial intelligence into eXtended reality training scenarios: A systematic literature review. Simul. Gaming 2024, 55, 445–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iop, A.; El-Hajj, V. G.; Gharios, M.; de Giorgio, A.; Monetti, F. M.; Edström, E. . & Romero, M. Extended reality in neurosurgical education: a systematic review. Sensors 2022, 22, 6067. [Google Scholar]

- Kasowski, J.; Johnson, B. A.; Neydavood, R.; Akkaraju, A.; Beyeler, M. A systematic review of extended reality (XR) for understanding and augmenting vision loss. J. Vis. 2023, 5, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.-P.; Ke, F.; Dai, Z.; West, L.; Bhowmik, S.; Yuan, X. Designing artificial intelligence (AI) in virtual humans for simulation-based training with graduate teaching assistants. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS 2021), 2021.

- Mendoza, S.; Sánchez-Adame, L. M.; Urquiza-Yllescas, J. F.; González-Beltrán, B. A.; Decouchant, D. A model to develop chatbots for assisting the teaching and learning process. Sensors 2022, 22(15), 5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordes, F.; Pang, R. Y.; Ajay, A.; Li, A. C.; Bardes, A.; Petryk, S. ;... Chandra, V. An introduction to vision-language modeling, 2024; arXiv:2405.17247. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Yang, J.; Loy, C. C.; Liu, Z. Learning to prompt for vision-language models. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130(9), 2337–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P. ;... & Amodei, D. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv preprint 2020.

- Giannakos, M. N.; Sharma, K.; Pappas, I. O.; Kostakos, V.; & Velloso, E. Multimodal data as a means to understand the learning experience. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, S.; Souchet, A. D.; Lameras, P.; Petridis, P.; Caporal, J.; Coldeboeuf, G.; & Duzan, H. Multimodal teaching, learning and training in virtual reality: a review and case study. Virtual Reality & Intell. Hardw. 2020, 2, 421–442. [Google Scholar]

- Di Mitri, D.; Schneider, J.; Specht, M.; & Drachsler, H. From signals to knowledge: A conceptual model for multimodal learning analytics. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2018, 34, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K. B.; Wei, W. Q.; Weeraratne, D.; Frisse, M. E.; Misulis, K.; Rhee, K. . & Snowdon, J. L. Precision medicine, AI, and the future of personalized health care. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, S. M. C.; Guerreiro, J.; & Tussyadiah, I. Artificial intelligence in business: State of the art and future research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 911–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, J. , Olsson, H. H., & Crnkovic, I. (2021). Engineering AI systems: A research agenda. In Artificial intelligence paradigms for smart cyber-physical systems (pp. 1-19).

- Dai, C.-P.; Ke, F.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Y. Exploring students’ learning support use in digital game-based math learning: A mixed-methods approach using machine learning and multi-case study. Comput. Educ. 2023, 194, 104698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinbaum, S. G. Pygmalion’s Spectacles; Wonder Stories, 1935.

- Mazuryk, T.; Gervautz, M. History, applications, technology, and future. Virtual Reality 1996, 72(4), 486–497. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, N. Snow Crash; Bantam Books: New York, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, P.; Kishino, F. A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems 1994, 77(12), 1321–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Dahan, N. A.; Al-Razgan, M.; Al-Laith, A.; Alsoufi, M. A.; Al-Asaly, M. S.; Alfakih, T. Metaverse framework: A case study on E-learning environment (ELEM). Electronics 2022, 11(10), 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, M. What is metaverse?—a definition based on qualitative meta-synthesis. Future Internet 2022, 14(11), 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh-The, T.; Pham, Q. V.; Pham, X. Q.; Nguyen, T. T.; Han, Z.; Kim, D. S. Artificial intelligence for the metaverse: A survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 117, 105581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi-Lanna, L. Multimodal Learning Analytics research with young children: A systematic review. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51(5), 1485–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.-P.; Ke, F. Designing narratives in multimodal representations for game-based math learning and problem solving. In de Vries, E.; Hod, Y.; Ahn, J. (Eds.). Proceedings of the 15th International Conference of the Learning Sciences - ICLS 2021 2021, pp. 909-910. Bochum, Germany: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

- Bernsen, N. O. Multimodality Theory. In Multimodal User Interfaces: From Signals to Interaction; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Ke, F.; Dai, C.-P. Patterns of using multimodal external representations in digital game-based learning. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2023, 60(8), 1918–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.; Minsky, M. L.; Rochester, N.; Shannon, C. E. A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, August 31, 1955. AI Magazine 2006, 27, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H. A. The New Science of Management Decision; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, C.; Ventura, S. Educational Data Mining: A Survey from 1995 to 2005. Expert Systems with Applications 2007, 33, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C. M. Neural Networks for Pattern Recognition; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R. Using learning analytics in personalized learning. In Handbook on personalized learning for states, districts, and schools, 165-174, 2016.

- Jussupow, E.; Spohrer, K.; Heinzl, A.; Gawlitza, J. Augmenting medical diagnosis decisions? An investigation into physicians’ decision-making process with artificial intelligence. Information Systems Research 2021, 32(3), 713–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. A. Artificial Intelligence: An Empirical Science. Artificial Intelligence 1995, 77(1), 95–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.-P.; Ke, F. Educational Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Simulation-Based Learning: A Systematic Mapping Review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2022, 3, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.-P.; Ke, F.; Pan, Y.; Moon, J.; Liu, Z. Effects of artificial intelligence-powered virtual agents on learning outcomes in computer-based simulations: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review 2024, 36, Article 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahavandi, S. Trusted autonomy between humans and robots: Toward human-on-the-loop in robotics and autonomous systems. IEEE Systems, Man, and Cybernetics Magazine 2017, 3(1), 10-17.

- Kirkley, S. E.; Kirkley, J. R. Creating next generation blended learning environments using mixed reality, video games and simulations. TechTrends 2005, 49(3), 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çöltekin, A.; Lochhead, I.; Madden, M.; Christophe, S.; Devaux, A.; Pettit, C. . & Hedley, N. Extended reality in spatial sciences: A review of research challenges and future directions. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 439. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ning, H.; Lin, Y.; Wang, W.; Dhelim, S.; Farha, F. . & Daneshmand, M. A survey on the metaverse: The state-of-the-art, technologies, applications, and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 14671–14688. [Google Scholar]

- Arena, F.; Collotta, M.; Pau, G.; & Termine, F. An overview of augmented reality. Comput. 2022, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhsaritalemi, S.; Sadeghi-Niaraki, A.; & Choi, S. M. A review on mixed reality: Current trends, challenges and prospects. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speicher, M.; Hall, B. D.; & Nebeling, M. What is mixed reality? In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, May 2019; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B. G. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Probl. 1965, 12, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O'Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J.; McKenzie, J. E.; Bossuyt, P. M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T. C.; Mulrow, C. D. . & Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2020, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacinger, F.; Boticki, I.; Mlinaric, D. System for semi-automated literature review based on machine learning. Electronics 2022, 11(24), 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D. M.; Ng, A. Y.; Jordan, M. I. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2003, 3(Jan), 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Ananiadou, S.; Rea, B.; Okazaki, N.; Procter, R.; Thomas, J. Supporting systematic reviews using text mining. Social Science Computer Review 2009, 27(4), 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, I. J.; Wallace, B. C. Toward Systematic Review Automation: A Practical Guide to Using Machine Learning Tools in Research Synthesis. Systematic Reviews 2019, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mara-Eves, A.; Thomas, J.; McNaught, J.; Miwa, M.; Ananiadou, S. Using Text Mining for Study Identification in Systematic Reviews: A Systematic Review of Current Approaches. Systematic Reviews 2015, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Röder, M.; Both, A.; Hinneburg, A. Exploring the space of topic coherence measures. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Shanghai, China, February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, S.; Spruit, M. Full-Text or Abstract? Examining Topic Coherence Scores Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA); IEEE: 17; pp. 165–174. 20 October.

- Forman, G. BNS feature scaling: an improved representation over tf-idf for svm text classification. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2008; pp. 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Bai, X.; Billinghurst, M.; Zhang, S.; Han, D.; Sun, M. . & Han, S. Haptic feedback helps me? A VR-SAR remote collaborative system with tangible interaction. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 1242–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Di Mitri, D.; Limbu, B.; Schneider, J.; Iren, D.; Giannakos, M.; & Klemke, R. Multimodal and immersive systems for skills development and education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, S.; Bai, X.; Billinghurst, M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S. . & Yan, Y. A gesture-and head-based multimodal interaction platform for MR remote collaboration. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 105, 3031–3043. [Google Scholar]

- Plunk, A.; Amat, A. Z.; Tauseef, M.; Peters, R. A.; & Sarkar, N. Semi-supervised behavior labeling using multimodal data during virtual teamwork-based collaborative activities. Sensors 2023, 23, 3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wei, Y.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, J.; Yu, C. LLM Enabled Generative Collaborative Design in a Mixed Reality Environment. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J. E.; Shanker, A.; Berman, A. B.; Pandian, B.; Jotwani, R. Utilisation of extended reality for preprocedural planning and education in anaesthesiology: a practical guide for spatial computing. Br. J. Anaesth. 2024, 132, 1342–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. G.; Lee, J. H.; Shim, J. W.; Rhee, W.; Kim, B. S.; Yoon, D. . & Kim, S. A multimodal virtual vision platform as a next-generation vision system for a surgical robot. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2024, 62, 1535–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist, R.; Rauter, G.; Marchal-Crespo, L.; Riener, R.; Wolf, P. Sonification and haptic feedback in addition to visual feedback enhances complex motor task learning. Exp. Brain Res. 2015, 233, 909–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Park, S.; Ryu, J. The effects of physical fidelity and task repetition on perceived task load and performance in the virtual reality-based training simulation. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55, 1507–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Spielberg, A.; Chounlakone, M.; Chang, G.; Matusik, W.; Rus, D. A simple, inexpensive, wearable glove with hybrid resistive-pressure sensors for computational sensing, proprioception, and task identification. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2020, 2, 2000002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. F.; Guan, J. Q.; Wang, X. F.; Chen, Q.; Hwang, G. J. Examining students' self-regulated learning processes and performance in an immersive virtual environment. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bekele, M. K.; Champion, E.; McMeekin, D. A.; Rahaman, H. The influence of collaborative and multi-modal mixed reality: Cultural learning in virtual heritage. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Cai, H. Multimodal Learning-Based Proactive Human Handover Intention Prediction Using Wearable Data Gloves and Augmented Reality. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6(4), 2300545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. Personalized healthcare museum exhibition system design based on VR and deep learning driven multimedia and multimodal sensing. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2023, 27, 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriarte-Portillo, A.; Ibáñez, M. B.; Zatarain-Cabada, R.; Barrón-Estrada, M. L. Comparison of using an augmented reality learning tool at home and in a classroom regarding motivation and learning outcomes. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2023, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhammad, A.; Falah, J.; Alfalah, S. F.; Abu-Tarboush, M.; Tarawneh, R. T.; Drikakis, D.; Charissis, V. “MedChemVR”: a virtual reality game to enhance medicinal chemistry education. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira dos Santos, L.; Christ, O.; Mate, K.; Schmidt, H.; Krüger, J.; Dohle, C. Movement visualisation in virtual reality rehabilitation of the lower limb: a systematic review. Biomed. Eng. Online 2016, 15, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, H.; Hu, H. Restructuring multimodal corrective feedback through augmented reality (AR)-enabled videoconferencing in L2 pronunciation teaching. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2023, 27, 83–107. [Google Scholar]

- Knobel, S. E. J.; Kaufmann, B. C.; Geiser, N.; Gerber, S. M.; Müri, R. M.; Nef, T. . & Cazzoli, D. Effects of virtual reality–based multimodal audio-tactile cueing in patients with spatial attention deficits: Pilot usability study. JMIR Serious Games 2022, 10, e34884. [Google Scholar]

- Knobel, S. E. J.; Gyger, N.; Nyffeler, T.; Cazzoli, D.; Müri, R. M.; Nef, T. Development and evaluation of a new virtual reality-based audio-tactile cueing system to guide visuo-spatial attention. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2020: 3192-3195, 3192. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo-Domenech, J.; Linares-Pellicer, J.; Ferri-Molla, I. Large language models for in situ knowledge documentation and access with augmented reality. Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2023, advance online publication.

- Konenkov, M.; Lykov, A.; Trinitatova, D.; Tsetserukou, D. VR-GPT: Visual language model for intelligent virtual reality applications. arXiv 2024.

- Fan, H.; Zhang, H.; Ma, C.; Wu, T.; Fuh, J. Y. H.; Li, B. Enhancing metal additive manufacturing training with the advanced vision language model: A pathway to immersive augmented reality training for non-experts. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 75, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcañiz Raya, M.; Marín-Morales, J.; Minissi, M. E.; Teruel Garcia, G.; Abad, L.; Chicchi Giglioli, I. A. Machine learning and virtual reality on body movements’ behaviors to classify children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.; Chirico, A.; Varandas, R.; Gamboa, H.; Gaggioli, A.; i Badia, S. B. Multimodal emotion classification using machine learning in immersive and non-immersive virtual reality. Virtual Reality 2024, 28, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. A.; Brown, D. J.; Mahmud, M.; Harris, M.; Shopland, N.; Heym, N.; Lewis, J. Enhancing biofeedback-driven self-guided virtual reality exposure therapy through arousal detection from multimodal data using machine learning. Brain Inform. 2023, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Song, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, Y.; & Wang, L. Cross-Modal Graph Semantic Communication Assisted by Generative AI in the Metaverse for 6G. Res. 2024, 7, 0342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OpenAI. GPT-4v(ision) system card. 2023, URL: https://cdn.openai.com/papers/ GPTV_System_Card.pdf.

- Radford A, Kim JW, Hallacy C, Ramesh A, Goh G, Agarwal S, Sastry G, Askell A, Mishkin P, Clark J, Krueger G, Sutskever I. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. arXiv:2103.00020, 2021.

- Chiang W-L, Li Z, Lin Z, Sheng Y, Wu Z, Zhang H, Zheng L, Zhuang S, Zhuang Y, Gonzalez JE, Stoica I, Xing EP. Vicuna: An open-source chatbot impressing GPT- 4 with 90% ChatGPT quality. 2023, URL: https://lmsys.org/blog/2023- 03- 30- vicuna/.

- Wang C-Y, Bochkovskiy A, Liao H-YM. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. CVPR, 2023, p. 7464–75.

- Baek Y, Lee B, Han D, Yun S, Lee H. Character region awareness for text detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2019, p. 9365–74.

- Li C, Bian S, Wu T, Donovan RP, Li B. Affordable artificial intelligence-assisted machine supervision system for the small and medium-sized manufacturers. Sensors 2022;22(16). [CrossRef]

- Godwin-Jones, R. Emerging spaces for language learning: AI bots, ambient intelligence, and the metaverse. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2023, 27, 2. [Google Scholar]

- I.A. Group, Scenarios for ambient intelligence in 2010, 2001.

- Cook, D. J.; Augusto, J. C.; Jakkula, V. R. Ambient intelligence: Technologies, applications, and opportunities. Pervasive Mobile Comput. 2009, 5, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toohey, K. The onto-epistemologies of new materialism: Implications for applied linguistics pedagogies and research. Appl. Linguist. 2019, 40, 937–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Kanbach, D. K.; Krysta, P. M.; Steinhoff, M. M.; & Tomini, N. Facebook and the creation of the metaverse: Radical business model innovation or incremental transformation? Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 2022, 28, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; & King, I. Multimodality in meta-learning: A comprehensive survey. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 250, 108976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, F.; Petrillo, A.; Iovine, G.; Salzano, C.; & Baffo, I. How does the metaverse shape education? A systematic literature review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13(9), 5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, S.; & Kim, N. Analysis of worldwide research trends on the impact of artificial intelligence in education. Sustainability 2021, 13(14), 7941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukurova, M.; Kent, C.; & Luckin, R. Artificial intelligence and multimodal data in the service of human decision-making: A case study in debate tutoring. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50(6), 3032–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: Large multi-modal models. WHO Guid. 2024, World Health Organization.

- Roumeliotis, K. I.; Tselikas, N. D. ChatGPT and OpenAI models: A preliminary review. Future Internet 2023, 15(6), 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujahid, M.; Rustam, F.; Shafique, R.; Chunduri, V.; Villar, M. G.; Ballester, J. B.; Ashraf, I. Analyzing sentiments regarding ChatGPT using novel BERT: A machine learning approach. Information 2023, 14(9), 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafferner, Z.; Illés, B.; Krammer, O.; Géczy, A. Can ChatGPT help in electronics research and development? A case study with applied sensors. Sensors 2023, 23(10), 4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, A.; Siriwardana, C.; Law, D.; Gunasekara, C.; Zhang, K.; Gamage, K. A scoping review and analysis of green construction research: a machine learning aided approach. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shneiderman, B.

Human-centered AI

. Oxford University Press 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).