Submitted:

10 October 2024

Posted:

11 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of the Processed Cheese Samples

2.3. Chemical Composition

2.4. Color

2.5. Free oil

2.6. Textural Measurements

2.7. Sensory Evaluation

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition

3.2. Color

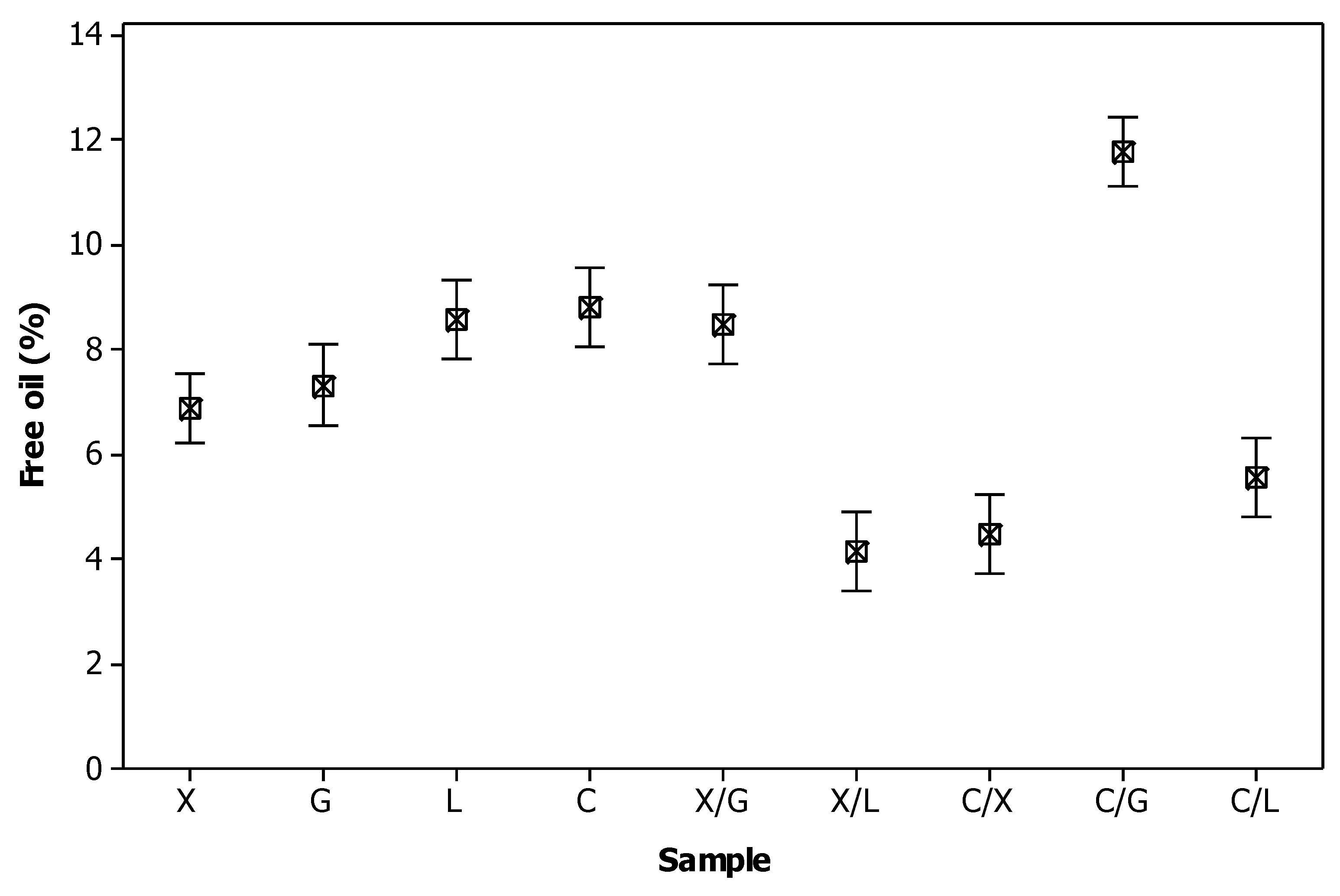

3.3. Free oil Formation

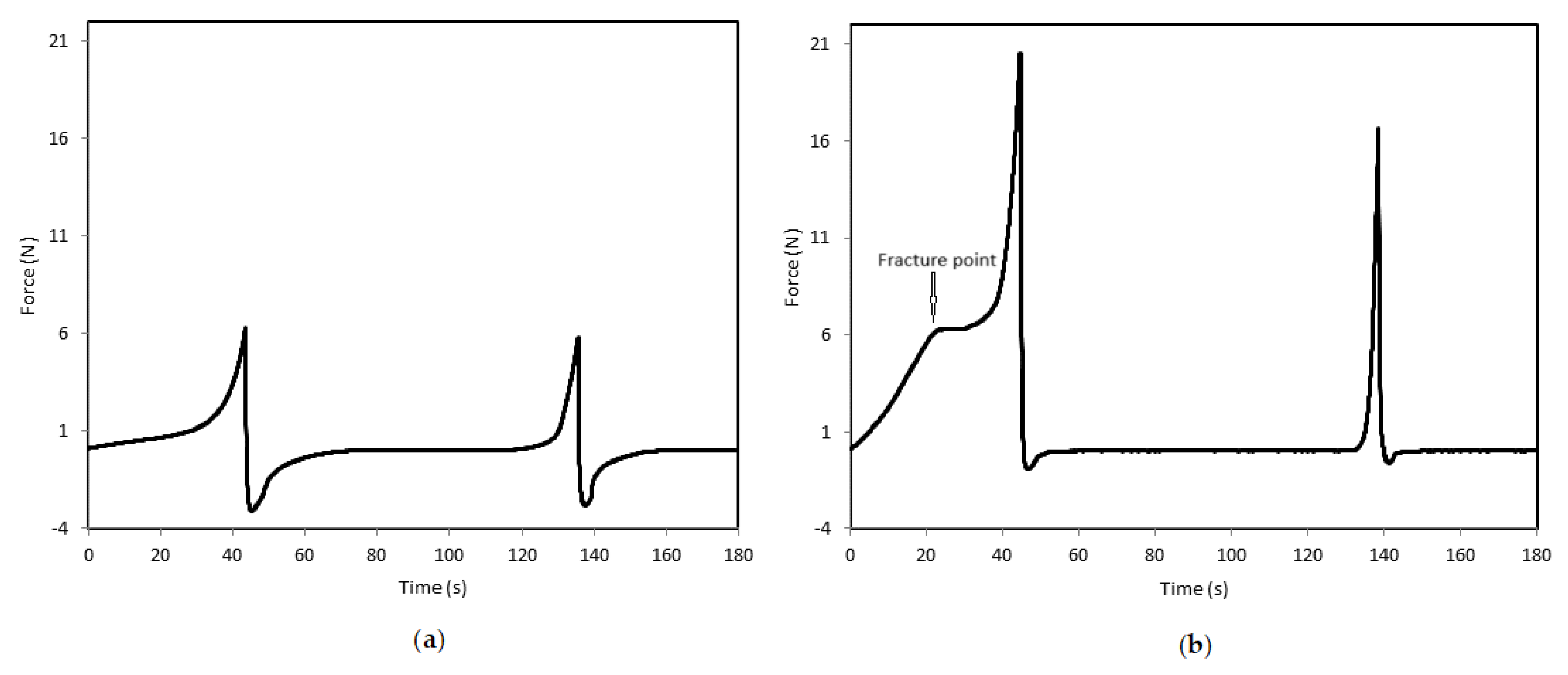

3.4. Textural Properties

3.5. Sensory Attributes

3.6. Correlations between Instrumental and Sensory Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guinee, T.P.; Carić, M.; Kaláb, M. Pasteurized processed cheese and substitute/imitation cheese products. In: Cheese Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology, Vol. 2, 3rd ed.; P.F. Fox, P.L.H. McSweeney, T.M. Cogan; T.P. Guinee, Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press: London, UK, 2004; pp. 350–394. [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Bast, A.; de Boer, A. Valorized food processing by-products in the EU: Finding the balance between safety, nutrition, and sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandona, E.; Blažić, M.; Jambrak, A.R. Whey utilisation: Sustainable uses and environmental approach. Food Technol. Biotech. 2021, 59(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lappa, I.K.; Papadaki, A.; Kachrimanidou, V.; Terpou, A.; Koulougliotis, D.; Eriotou, E.; Kopsahelis, N. Cheese Whey Processing: Integrated biorefinery concepts and emerging food applications. Foods 2019, 8, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N., Heena, Dixit, A., Mehra, M., Daniloski, D., Trajkovska Petkoska, A. (2023). Utilization of Whey: Sustainable Trends and Future Developments. In: Whey Valorization, A. Poonia, A. Trajkovska Petkoska Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023.

- El-Aidie, S.A.M.; Khalifa, G.S.A. Innovative applications of whey protein for sustainable dairy industry: Environmental and technological perspectives—A comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, 13319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, S.; Ahmed, N.; Soda, M. Application of salt whey from Egyptian Ras cheese in processed cheese making. Food Nutr. Sci. 2013, 4, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shibiny, S.; Shenana, M.E.; El-Nagar, G.F.; Abdou, S.M. Preparation and properties of low fat processed cheese spreads. Int. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 2(1), 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustaw, W.; Mleko, S. The effect of polysaccharides and sodium chloride on physical properties of processed cheese analogs containing whey proteins. Milchwissenschaft 2007, 62(1), 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mihulová, M.; Vejlupková, M.; Hanušová, J.; Štětina, J.; Panovská, Z. Effect of modified whey proteins on texture and sensory quality of processed cheese. Czech J. Food Sci. 2013, 31(6), 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sołowiej, B.G.; Nastaj, M.; Szafranska, J.O.; Terpiłowski, K.; Małecki, J.; Mleko, S. The effect of fat replacement by whey protein microcoagulates on the physicochemical properties and microstructure of acid casein model processed cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2022, 131, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, B.J.; Wendorff, W.L.; Lindsay, R.C. Effects of ingredients on the functionality of fat-free process cheese spreads. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65(5), 822–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziantoniou, S.E.; Thomareis, A.S.; Kontominas, M.G. Effect of chemical composition on physico-chemical, rheological and sensory properties of spreadable processed whey cheese. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 241, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Anema, S.G. The effect of the pH at cooking on the properties of processed cheese spreads containing whey proteins. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziantoniou, S.E.; Thomareis, A.S.; Kontominas, M.G. Effect of different stabilizers on rheological properties, fat globule size and sensory attributes of novel spreadable processed whey cheese. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245(1), 2401–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermiki, M.; Ntzimani, A.; Badeka, A.; Savvaidis, I.N.; Kontominas, M.G. Shelf-life extension and quality attributes of the whey cheese “Myzithra Kalathaki” using modified atmosphere packaging. LWT 2008, 41, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Butt, M.S.; Pasha, I.; Sameen, A. Quality of processed cheddar cheese as a function of emulsifying salt replaced by κ-carrageenan. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015, 19(8), 1874–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjo, A.F.; Saraiva, B.R.; da Silva, J.B.; Ogawa, C.Y.L.; Sato, F.; Bruschi; M. L.; Riegel-Vidotti, I.C.; Simas, F.F.; Matumoto-Pintro, P.T. A new food stabilizer in technological properties of low-fat processed cheese. Eur. Food Res. Tech. 2023, 249, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černíková, M.; Buňka, F.; Pavlínek, V.; Březina, P.; Hrabě, J.; Valásěk, P. Effect of carrageenan type on viscoelastic properties of processed cheese. Food Hydrocoll. 2008, 22, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černíková, M.; Buňka, F.; Pospiech, M.; Tremlová, B.; Hladká, K.; Pavlínek, V.; Březina, P. Replacement of traditional emulsifying salts by selected hydrocolloids in processed cheese production. Int. Dairy J. 2010, 20(5), 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabour, N.; El-Shanshory, A. The influence of protein content and some hydrocolloids on textural attributes of spreadable processed cheese. TJSAR 2018, 14(5), 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, D.F.; de Souza Ferreira, S.B.; Bruschi, M.L.; Britten, M.; Matumoto-Pintro, P.T. Effect of commercial konjac glucomannan and konjac flours on textural, rheological and microstructural properties of low fat processed cheese. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 60, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochvílová, A.; Salek, R.N.; Vašina, M.; Lazárková, Z.; Dostálová, J.; Šenkýrová, J. The impact of different hydrocolloids on the viscoelastic properties and microstructure of processed cheese manufactured without emulsifying salts in relation to storage time. Foods 2022, 11, 3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arda, E.; Kara, S.; Pekcan, O. Synergistic effect of the locust bean gum on the thermal phase transitions of κ-carrageenan gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.C.; Bourbon, A.I.; Rocha, C.; Ribeiro, C.; Maia, J.M.; Gonçalves, M.P.; Teixeira, J.A.; Vicente, A.A. Rheological characterization of κ-carrageenan/galactomannan and xanthan/galactomannan gels: Comparison of galactomannans from non-traditional sources with conventional galactomannans. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 83, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaiudom, S.; Goff, H.D. Effect of κ-carrageenan on milk protein polysaccharide mixtures. Int. Dairy J. 2003, 13, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouryieh, H.A.; Herald, T.J.; Aramouni, F.; Alavi, S. Intrinsic viscosity and viscoelastic properties of xanthan/guar mixtures in dilute solutions: Effect of salt concentration on the polymer interactions. Food Res. Int. 2007, 40, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, D.E.; Chen, Y.; Liao, M.-L.; Salvatore, R.; Boger, D.V.; Prica, M. Structure and rheology of the κ-carrageenan/locust bean gum gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2001, 15, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, D.; van de Velde, F.; Visschers, R.W. The gap between food gel structure, texture and perception. Food Hydrocoll. 2006, 20, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakir, E.; Foegeding, E.A. Combining protein micro-phase separation and protein-polysaccharide segregative phase separation to produce gel structures. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 1538–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallieri, A.L.F.; Cunha, R.L. Cold-set whey protein gels with addition of polysaccharides. Food Biophys. 2009, 4, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benichou, A.; Aserin, A.; Garti, N. W/O/W double emulsions stabilized with WPI–polysaccharide complexes. Colloid Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2007, 294, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, C.; Lopes da Silva, J.A.L. Rheology of galactomannan–whey protein mixed systems. Int. Dairy J. 2003, 13, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, X.T.; Turgeon, S.L. Textural and water binding behaviors of β-lactoglobulin-xanthan gum electrostatic hydrogels in relation to their microstructure. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 49, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Hydrocolloids at interfaces and the influence on the properties of dispersed systems. Review Article. Food Hydrocoll. 2003, 17, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.K.; Nickerson, M.T. Formation and functionality of whey protein isolate- (kappa-, iota-, and lambda-type) carrageenan electrostatic complexes. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 27, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.S.; Decker, E.A.; McClements, D.J. Influence of pH and carrageenan type on properties of β-lactoglobulin stabilized oil-in-water emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2005, 19(1), 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakir, E.; Khan, S.A.; Foegeding, E.A. The effect of pH on gel structures produced using protein-polysaccharide phase separation and network inversion. Int. Dairy J. 2012, 27, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDF Standard 4, Cheese and processed cheese. Determination of total solid content (reference method); International Dairy Federation: Brussels; 2004.

- ISO Standard 3433, Cheese - Determination of fat content - Van Gulik method. ISO: Geneva; 2008.

- AOAC Official methods of analysis. , 17th ed.Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington DC, USA, 2005.

- Kindstedt, P.S.; Fox, P.F. Modified Gerber test for free oil in melted mozzarella cheese. J. Food Sci. 1991, 56(4), 1115–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, M.C.; Comstock, S.H. Effect of degree of compression on texture profile parameters. J. Texture Stud. 1981, 12, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO Standard 8586, Sensory analysis -- General guidelines for the selection, training and monitoring of selected assessors and expert sensory assessors. ISO: Geneva; 2012.

- Rousseau, B. Sensory evaluation techniques. In Handbook of Food Analysis: Physical Characterization and Nutrient Analysis, Vol. 1, 2nd ed.; L.M.L. Nollet, Ed.; Marcel Dekker Inc.: New York, USA, 2004; pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, A.D.; Mallmann, S.; Gazoni, I.; Cavalheiro, D.; Rigo, E. Effect of acid casein freezing on the industrial production of processed cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2021, 118, 105043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarso, S.; McParland, S.; Visentin, G.; Berry, D.P.; McDermott, A.; De Marchi, M. Genetic and nongenetic factors associated with milk color in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 7345–7361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul-Sadhu, S. Impact of low refrigeration temperature on colour of milk. Acta Aliment. 2016, 45(3), 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, D.; Hansen, E.; Arndal, A.; Appelgren Trinderup, R.; Skibsted, L.H. Influence of light and temperature on the colour and oxidative stability of processed cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2001, 11, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, M.; Kelly, A.L.; Vasiljevic, T. Gelling properties of microparticulated whey proteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 6825–6832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, C.R.; Dias, A.I.; Viotto, W.H. Microstructure, texture, colour and sensory evaluation of a spreadable processed cheese analogue made with vegetable fat. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowney, M.; Roupas, P.; Hickey, M.W.; Everett, D.W. Factors affecting the functionality of mozzarella cheese. Aust. J. Dairy Technol. 1999, 54, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Emulsion gels: The structuring of soft solids with protein-stabilized oil droplets. Review Article. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 28, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomareis, A.S.; Hardy, J. Evolution de la chaleur spécifique apparente des fromages fondus entre 40 et 100°C. Influence de leur composition. J. Food Eng. 1985, 4, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, A.; Hemar, Y.; Singh, H. Influence of polysaccharides on the rate of coalescence in oil-in-water emulsions formed with highly hydrolyzed whey proteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 5491–5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouryieh, H.A.; Puli, G.; Williams, K.; Aramouni, F. Effects of xanthan–locust bean gum mixtures on the physicochemical properties and oxidative stability of whey protein stabilised oil-in-water emulsions. Food Chem. 2015, 167, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copetti, G.; Grassi, M.; Lapasin, R.; Pricl, S. Synergistic gelation of xanthan gum with locust bean gum: a rheological investigation. Glycoconjugate J. 1997, 14, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, A.; Ichikawa, Y.; Kawabata, A. Rheological properties of mixed gels of κ-carrageenan with galactomannans. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 1995, 59(1), 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.R.; Dumlu, P.; Vermeir, L.; Lewille, B.; Lesaffer, A.; Dewettinck, K. Rheological characterization of gel-in-oil-in-gel type structured emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 46, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paderes, M.; Ahirwal, D.; Pieto, S.F. Natural and synthetic polymers in fabric and home care applications. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2017, 20170021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitreli, G.; Thomareis, A.S. Texture evaluation of block-type processed cheese as a function of chemical composition and in relation to its apparent viscosity. J. Food Eng. 2007, 79, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummel, S.E.; Lee, K. Soluble hydrocolloids enable fat reduction in process cheese spreads. J. Food Sci. 1990, 55, 1290–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, A.H.; Patel, H.G.; Pinto, S.; Prajapati, J.P. Quality of casein based Mozzarella cheese analogue as affected by stabilizer blends. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 47(2), 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totosaus, A.; Guerrero, I.; Montejano, J.G. Effect of added salt on textural properties of heat-induced gels made from gum–protein mixtures. J. Texture Stud. 2005, 36, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Shirashoji, N.; Lucey, J.A. Rheological, textural and melting properties of commercial samples of some of the different types of pasteurized processed cheese. Int. J. Dairy Tech. 2007, 60(2), 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Content1 (% w/w) |

|---|---|

| Moisture | 55.93 ± 0.45 |

| Protein | 12.35 ± 0.12 |

| Fat Fat in dry matter |

25.50 ± 0.10 57.86 ± 0.55 |

| Ash | 1.65 ± 0.23 |

| NaCl | 1.04 ± 0.08 |

| Sample | Lightness, L* | Parameter a* | Parameter b* |

|---|---|---|---|

| X | 90.7 ± 0.3b 2 | –1.1 ± 0.3a | 6.3 ± 0.7d |

| G | 91.8 ± 0.3a | –1.3 ± 0.2ab | 6.2 ± 0.1d |

| L | 90.9 ± 0.7b | –1.6 ± 0.3bc | 6.4 ± 0.1c |

| C | 90.2 ± 0.3c | –1.5 ± 0.2bc | 7.1 ± 0.1 a |

| X/G | 91.4 ± 0.3a | –1.6 ± 0.3bc | 6.8 ± 0.2b |

| X/L | 91.6 ± 0.4a | –1.7 ± 0.3c | 6.8 ± 0.2b |

| C/X | 91.6 ± 0.3a | –1.3 ± 0.2ab | 6.6 ± 0.2c |

| C/G | 90.9 ± 0.4b | –1.7 ± 0.2c | 7.2 ± 0.2a |

| C/L | 90.6 ± 0.5b | –1.6 ± 0.3bc | 7.1 ± 0.3a |

| Textural Property | Sample | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | G | L | C | X/G | X/L | C/X | C/G | C/L | |

| B (N) | - | - | - | 4.56 ± 1.30c | - | 5.85 ± 1.58b | - | 3.19 ± 0.78d | 10.26 ± 1.67a |

| H1 (N) | 6.99 ± 1.70g 2 | 11.03 ± 0.41ef | 8.87 ± 0.68fg | 25.64 ± 2.40b | 12.11 ± 0.36e | 22.21 ± 2.51c | 11.04 ± 1.67ef | 16.33 ± 1.72d | 31.71 ± 1.76a |

| H2 (N) | 6.38 ± 1.53f | 10.47 ± 0.33d | 8.34 ± 0.65e | 18.86 ± 1.07b | 11.06 ± 0.35d | 17.90 ± 1.53b | 10.08 ± 1.27d | 13.44 ± 1.15c | 23.10 ± 1.38a |

| A1 (mJ) | 22.33 ± 4.41e | 34.50 ± 2.26de | 28.33 ± 2.50de | 101.97 ± 22.34b | 46.83 ± 2.14d | 94.83 ± 18.86b | 44.00 ± 10.86d | 73.00 ± 12.18c | 154.67 ± 14.35a |

| A2 (mJ) | 10.83 ± 3.13c | 9.67 ± 1.03cd | 8.83 ± 2.14cd | 13.67 ± 2.73b | 8.33 ± 0.82cd | 10.83 ± 2.31c | 6.17 ± 0.41e | 9.49 ± 1.27cd | 16.83 ± 1.17a |

| A2/A1 (-) | 0.48 ± 0.01a | 0.28 ± 0.01b | 0.31 ± 0.07b | 0.13 ± 0.02cd | 0.18 ± 0.02c | 0.12 ± 0.04cd | 0.15 ± 0.03cd | 0.13 ± 0.01cd | 0.11 ± 0.01d |

| A3 (mJ) | 12.00 ± 3.16a | 7.67 ± 1.03b | 8.00 ± 2.68b | 3.50 ± 0.56cd | 5.17 ± 0.75c | 1.50 ± 0.55d | 4.00 ± 0.89cd | 2.67 ± 0.52cd | 1.00 ± 0.01d |

| S1 (mm) | 16.12 ± 2.17a | 5.78 ± 1.03cd | 8.54 ± 0.86b | 6.88 ± 1.23bc | 5.07 ± 0.71cd | 6.28 ± 1.69c | 3.93 ± 0.50d | 5.14 ± 1.42cd | 8.32 ± 0.60b |

| S2 (mm) | 16.44 ± 2.12a | 8.41 ± 1.39d | 14.09 ± 2.83b | 10.98 ± 3.02c | 6.89 ± 1.16d | 6.74 ± 1.95d | 5.15 ± 0.90d | 7.73 ± 2.04d | 7.62 ± 0.88d |

| G (N) | 3.41 ± 1.07a | 3.04 ± 0.36ab | 2.82 ± 0.75b | 3.35 ± 0.49a | 2.12 ± 0.18cd | 2.33 ± 0.33bcd | 1.58 ± 0.20d | 1.58 ± 0.18d | 3.45 ± 0.15a |

| Intensity rating test1 | Hedonic rating test2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Yellow color | Fattiness | Stickiness | Aroma-flavor acceptability | Texture acceptability | Overall acceptability |

| X | 2.43 ± 0.64e 3 | 7.37 ± 0.82ab | 6.80 ± 0.80a | 6.33 ± 1.21ab | 7.02 ± 0.78a | 6.23 ± 1.57ab |

| G | 3.00 ± 0.71de | 5.98 ± 0.69bc | 7.67 ± 0.57a | 6.87 ± 0.76a | 8.42 ± 0.49a | 8.20± 0.63a |

| L | 3.47 ± 0.69cd | 8.10 ± 0.75a | 7.92 ± 0.84a | 6.98 ± 1.18a | 6.58 ± 0.99a | 7.05 ± 1.02a |

| C | 4.88 ± 0.48b | 4.55 ± 0.69cd | 4.62± 0.55b | 3.42 ± 1.49c | 2.70 ± 1.19c | 2.23 ± 0.96c |

| X/G | 4.00 ± 0.52c | 8.05 ± 0.67a | 8.07 ± 0.67a | 6.73 ± 0.94a | 7.78 ± 0.58a | 7.53 ± 0.77a |

| X/L | 3.65 ± 0.48cd | 3.35 ± 1.77de | 2.43 ± 1.41c | 3.30 ± 1.22c | 0.77 ± 0.50d | 1.07 ± 0.38c |

| C/X | 2.95 ± 0.29de | 4.73 ± 2.15cd | 4.85 ± 1.63b | 4.75 ± 1.02bc | 4.83 ± 2.04b | 4.65 ± 2.48b |

| C/G | 5.62 ± 0.53a | 4.05 ± 2.28cde | 4.10 ± 0.93b | 5.73 ± 1.26ab | 3.57 ± 2.18bc | 4.87 ± 1.19b |

| C/L | 6.10 ± 0.68a | 2.18 ± 1.18e | 2.05 ± 1.10c | 3.98 ± 0.88c | 2.63 ± 1.63c | 2.35 ± 0.63c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).