1. Introduction

Environmental and health considerations are contributing strongly to increasing demand for plant-based food offerings in the diet use [

1,

2]. The global market for plant-based dairy products anticipated to expand from USD 30.49 billion in 2024 to USD 62.03 billion by 2031, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.7% [

3]. Specifically, the plant-based cheese market, which was valued at

$1.4 billion in 2023, is projected to grow at a CAGR of over 16.0% by 2030 [

4]. This significant growth highlights the rising consumer demand for plant-based offerings, diversity and choice in their purchasing choices.

Cheese, a fundamental component of diets worldwide, is celebrated for its wide range of flavours, textures, and versatility. Among the most popular types is Cheddar, which is traditionally made from pasteurized cow’s milk, using calf rennet or its alternatives for coagulation [

5]. Processed cheese, on the other hand, is created by melting and heating natural cheese blends with the addition of emulsifying salts and other ingredients [

6,

7]. These conventional cheese products set the standard for the sensory and functional qualities that plant-based alternatives aim to replicate.

Plant-based cheese analogues use water, fats, proteins, emulsifiers, hydrocolloids, and flavouring agents in an attempt to mimic conventional cheese products [

8,

9]. Such plant-based products typically have lower protein content, higher saturated fats and carbohydrates, and different structural properties compared to established dairy products, complicating efforts to mimic the texture and melting characteristics of traditional cheese [

10,

11]. For example, plant proteins, with their larger molecular size and more complex quaternary structures, struggle to form the compact gel networks that casein proteins do, making it difficult to replicate functional properties such as meltability and flowability in plant-based cheeses [

12].

Sensory attributes such as flavour and texture, play a crucial role in determining consumer acceptance of cheese products. Traditional dairy cheeses are highly valued for their ability to deliver these qualities. However, consumer preference remains a significant challenge for plant-based products, primarily due to their often-unpleasant intrinsic flavours and odours, which can limit their appeal. These off-flavours, frequently described as “green,” “grassy,” and “beany” arise from common volatile off-flavour (such as aldehydes, furans, alcohols, pyrazines, ketones) as well as non-volatile compounds (like phenolics, peptides, alkaloids, saponins), negatively impacting their consumer acceptance [

13,

14]. Assessing sensory properties is therefore essential for evaluating product performance and guiding the development of plant-based cheese products to overcome these challenges and meet consumer expectations [

15].

There are different formats of cheese products including block-style and slice-style available in the market. Block cheeses are typically used for slicing and grating, while slice cheeses are primarily used in sandwiches and burgers, where texture and meltability are critical. This study analysed commercially available plant-based cheese analogues on the Irish market, specifically focusing on block-style and slice-style formats, to assess how these products compare to conventional dairy cheeses in terms of composition, physical properties, and sensory performance. A total of 16 cheese products, including plant-based blocks and slices, Cheddar, and processed cheeses, were collected from leading Irish retailers. These products were evaluated for proximate composition, microstructure, rheology, thermal behaviour, and sensory attributes using instrumental analysis and a trained sensory panel. The objective was to identify key differences and potential performance gaps between plant-based and dairy cheeses, particularly regarding flavour, texture, and meltability across both formats. By completing a comprehensive benchmarking exercise, this work provides insights into how current plant-based cheese analogues align with consumer expectations and highlights specific areas for product improvement to enhance acceptance and expand market potential.

4. Conclusions

Significant differences were observed between plant-based and dairy-based products. With plant-based cheeses having lower protein, higher moisture, and higher carbohydrate content due to the use of hydrocolloids and starches, while Cheddar cheese had the simplest composition and highest protein content. Before melting, plant-based cheeses generally had higher lightness (L*), with redness (a*) and yellowness (b*) as influenced by colorants like paprika extract, while upon melting, lightness decreased across all samples. Microstructural analysis revealed no continuous protein network in plant-based products, unlike Cheddar cheese, which exhibited a natural protein-fat matrix contributing to its high hardness. Plant-based cheeses showed varied hardness, with some achieving firmness similar to dairy cheese through hydrocolloids. Processed and most plant-based cheeses had low meltability due to starch, stabilizers, and emulsifying salts. Sensory evaluation found traditional dairy cheese most preferred, with strong positive correlations for flavour, texture, and acceptability. Processed cheese was moderately accepted, while plant-based cheeses had least likeness of flavour and texture leading to lowest overall acceptability.

The study highlights the challenges plant-based cheeses face in replicating dairy cheese’s sensory and functional attributes. Despite advancements, textural and sensory deficiencies remain, emphasizing the need for further research on ingredient optimization and fermentation to improve consumer acceptance and market competitiveness.

Figure 1.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy images (x20) of block-style Cheddar (a), processed (b), plant 1 (c), plant 2 (d), plant 3 (e), plant 4 (f) and plant 5 (g) products. The images show distribution of fat globules (green) and protein (red). Scale bar corresponds to 30 μm.

Figure 1.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy images (x20) of block-style Cheddar (a), processed (b), plant 1 (c), plant 2 (d), plant 3 (e), plant 4 (f) and plant 5 (g) products. The images show distribution of fat globules (green) and protein (red). Scale bar corresponds to 30 μm.

Figure 2.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy images (x20) of Slice-style Cheddar (a), processed (b), plant 1 (c), plant 2 (d), plant 3 (e), plant 4 (f), plant 5 (g), plant 6 (h) and plant 7 (i) products. The images show distribution of fat globules (green) and protein (red). Scale bar corresponds to 30 μm.

Figure 2.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy images (x20) of Slice-style Cheddar (a), processed (b), plant 1 (c), plant 2 (d), plant 3 (e), plant 4 (f), plant 5 (g), plant 6 (h) and plant 7 (i) products. The images show distribution of fat globules (green) and protein (red). Scale bar corresponds to 30 μm.

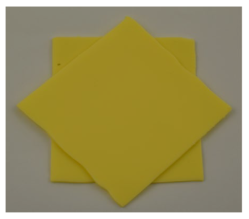

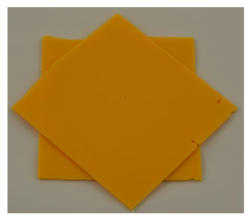

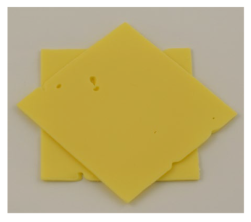

Figure 3.

Photographs of Block style cheddar, processed, plant 1, plant 2, plant 3, plant 4 and plant 5 products before (a-g) and after (h-n) oven melting at 232°C for 5 min.

Figure 3.

Photographs of Block style cheddar, processed, plant 1, plant 2, plant 3, plant 4 and plant 5 products before (a-g) and after (h-n) oven melting at 232°C for 5 min.

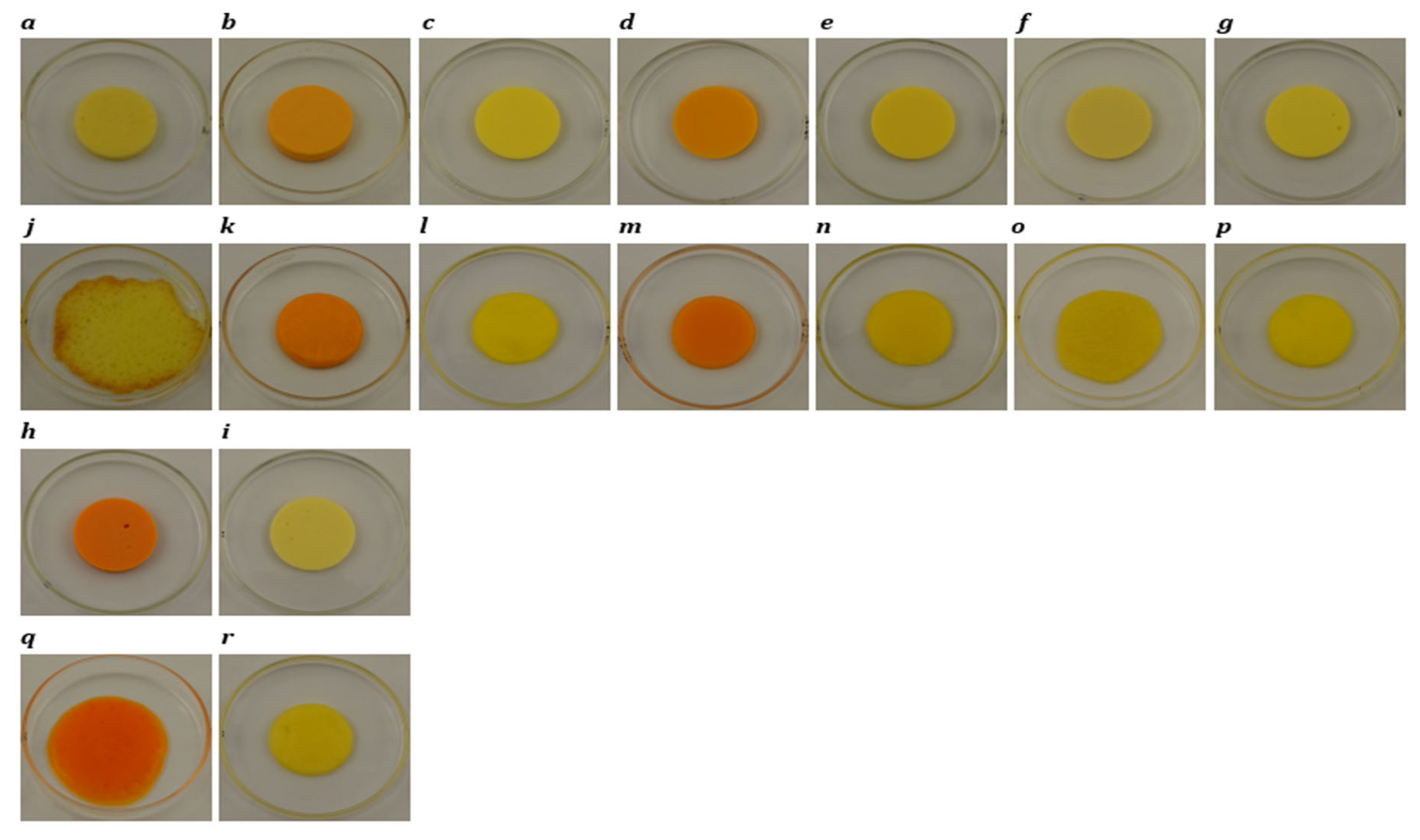

Figure 4.

Photographs of Slice style cheddar, processed, plant 1, plant 2, plant 3, plant 4, plant 5, plant 6 and plant 7 products before (a-i) and after (j-r) oven melting at 232°C for 5 min.

Figure 4.

Photographs of Slice style cheddar, processed, plant 1, plant 2, plant 3, plant 4, plant 5, plant 6 and plant 7 products before (a-i) and after (j-r) oven melting at 232°C for 5 min.

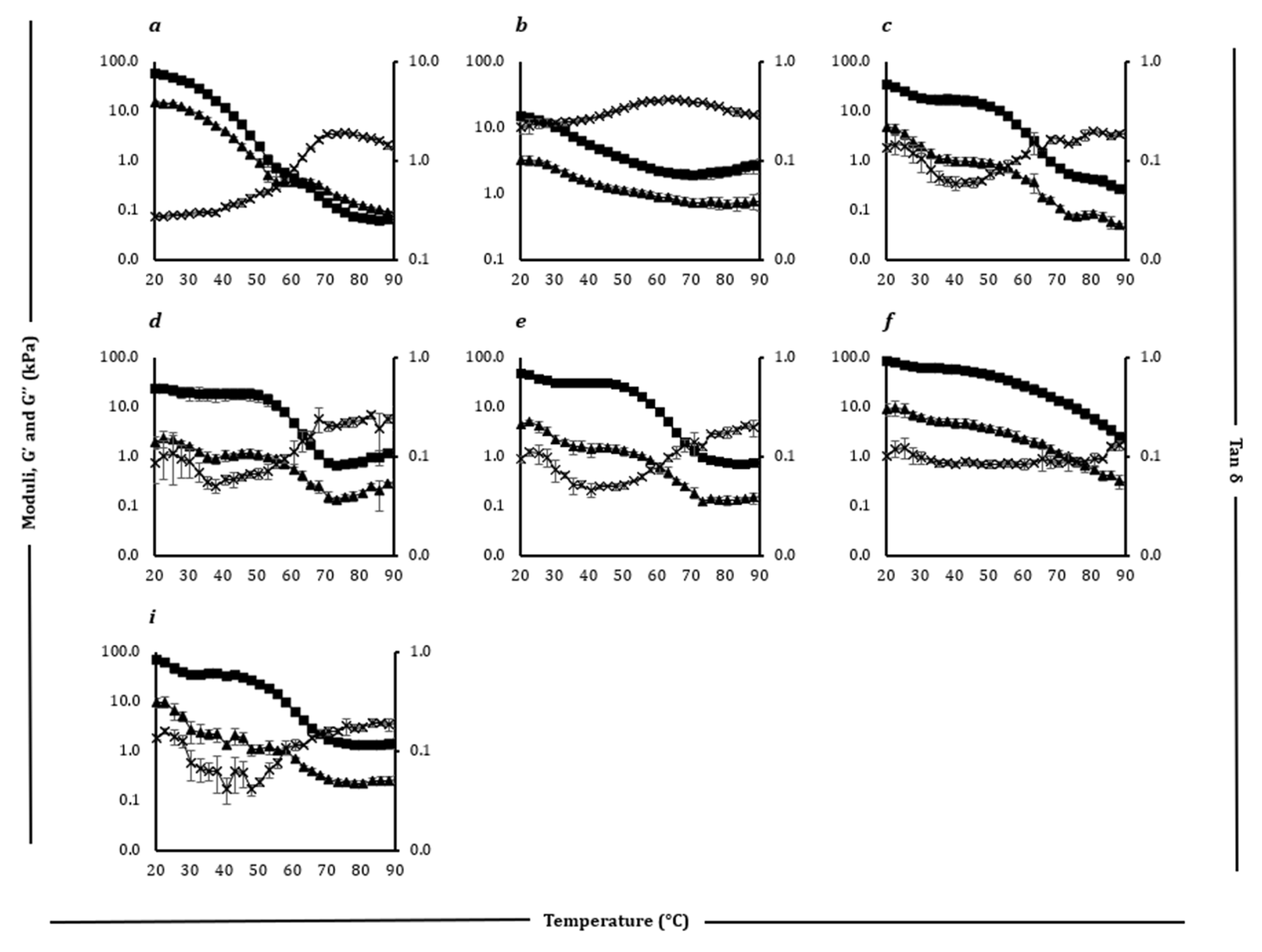

Figure 5.

Rheological profiles showing storage modulus (G’) (filled square), loss modulus (G’’) (filled triangle) and loss tangent (Tan δ) (cross) as a function of temperature in the range 20–90°C for block style cheddar (a), processed (b), plant 1 (c), plant 2 (d), plant 3 (e), plant 4 (f) and plant 5 (g) products.

Figure 5.

Rheological profiles showing storage modulus (G’) (filled square), loss modulus (G’’) (filled triangle) and loss tangent (Tan δ) (cross) as a function of temperature in the range 20–90°C for block style cheddar (a), processed (b), plant 1 (c), plant 2 (d), plant 3 (e), plant 4 (f) and plant 5 (g) products.

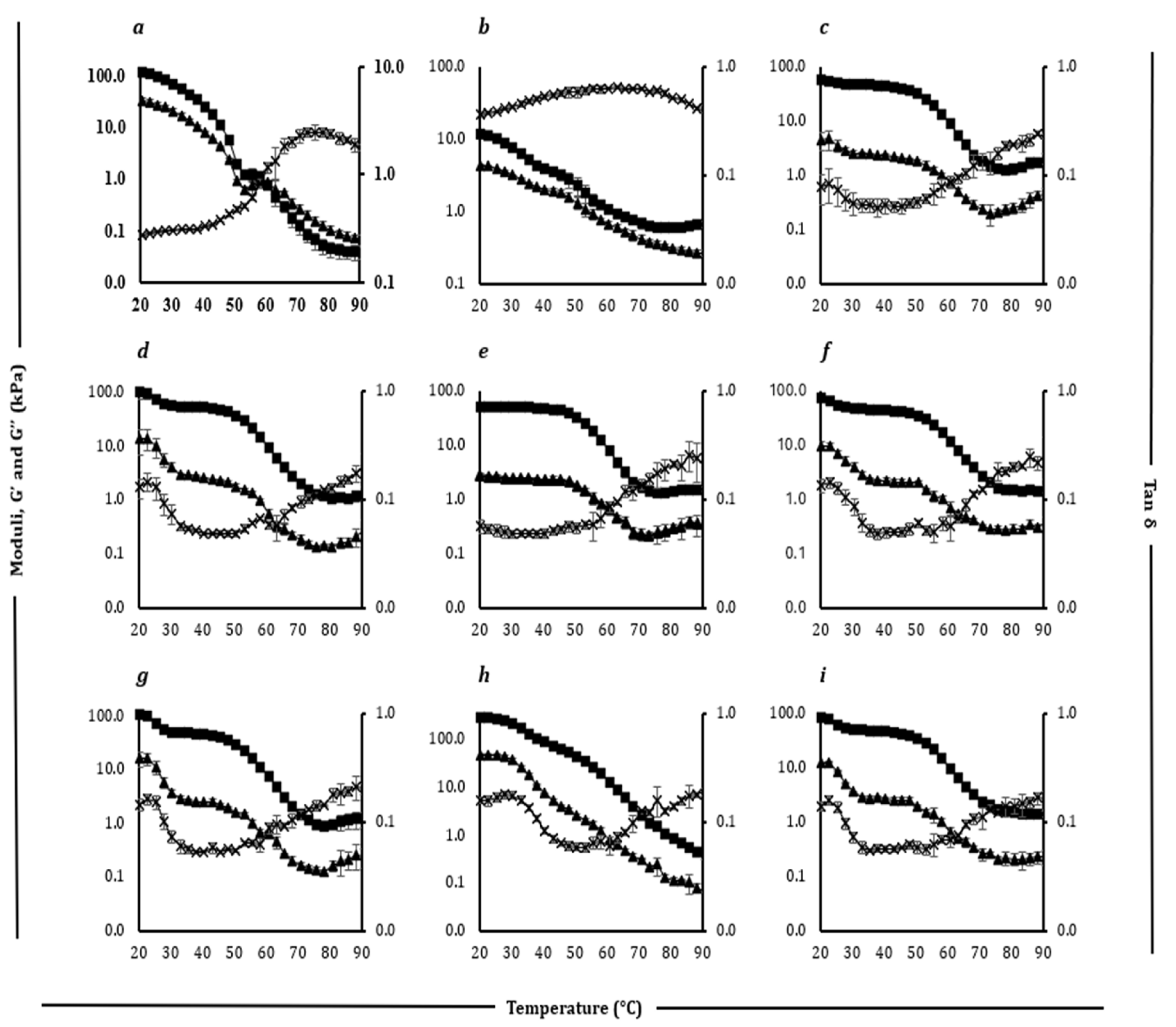

Figure 6.

Rheological profiles showing storage modulus (G’) (filled square), loss modulus (G’’) (filled triangle) and loss tangent (Tan δ) (cross) as a function of temperature in the range 20–90°C for Slice style cheddar (a), processed (b), plant 1 (c), plant 2 (d), plant 3 (e), plant 4 (f), plant 5 (g), plant 6 (h) and plant 7 (i) products.

Figure 6.

Rheological profiles showing storage modulus (G’) (filled square), loss modulus (G’’) (filled triangle) and loss tangent (Tan δ) (cross) as a function of temperature in the range 20–90°C for Slice style cheddar (a), processed (b), plant 1 (c), plant 2 (d), plant 3 (e), plant 4 (f), plant 5 (g), plant 6 (h) and plant 7 (i) products.

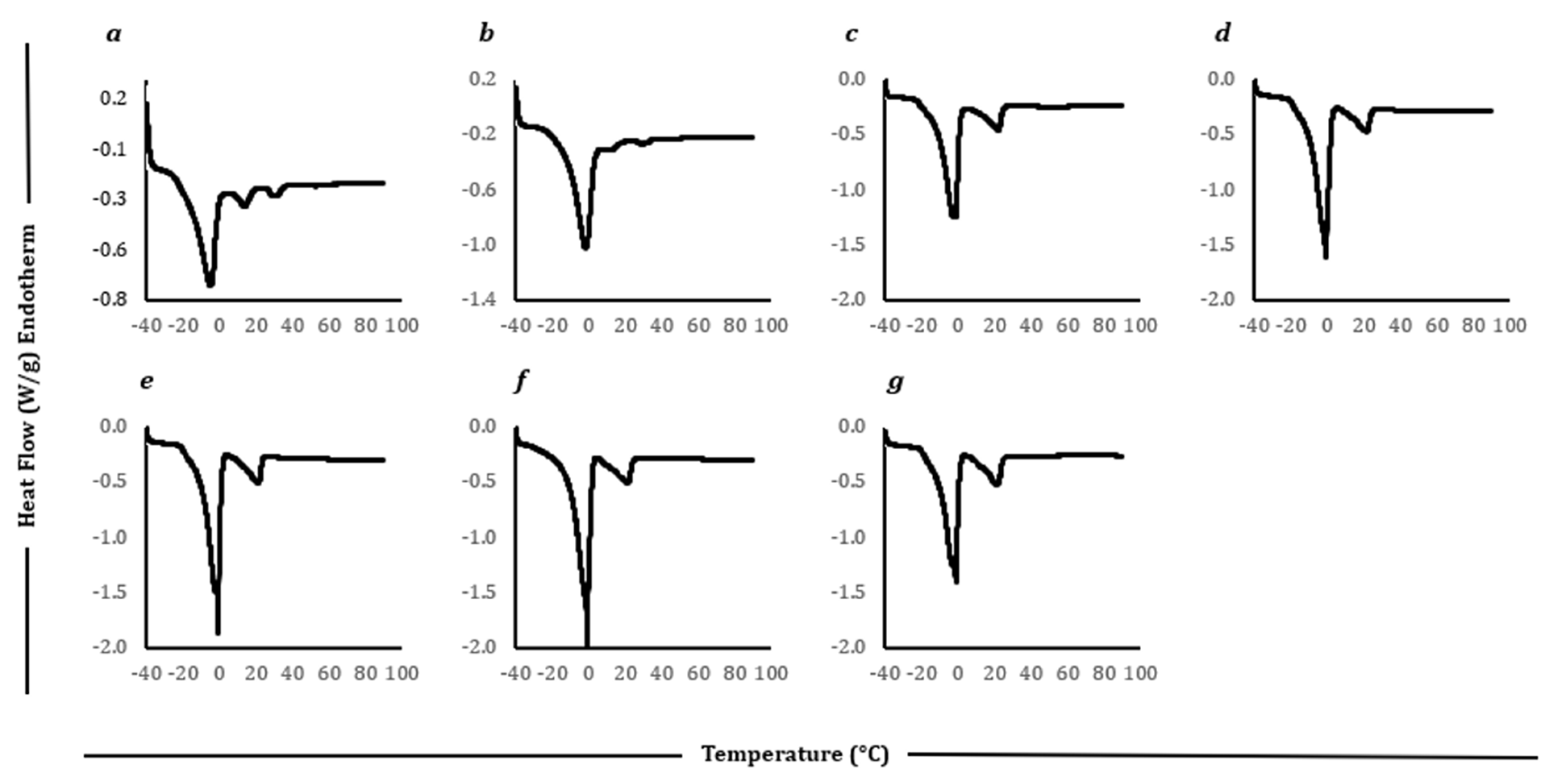

Figure 7.

Differential scanning calorimetry thermograms of heating ramp from −40 to 90°C for block style cheddar (a), processed (b), plant 1 (c), plant 2 (d), plant 3 (e), plant 4 (f) and plant 5 (g) products.

Figure 7.

Differential scanning calorimetry thermograms of heating ramp from −40 to 90°C for block style cheddar (a), processed (b), plant 1 (c), plant 2 (d), plant 3 (e), plant 4 (f) and plant 5 (g) products.

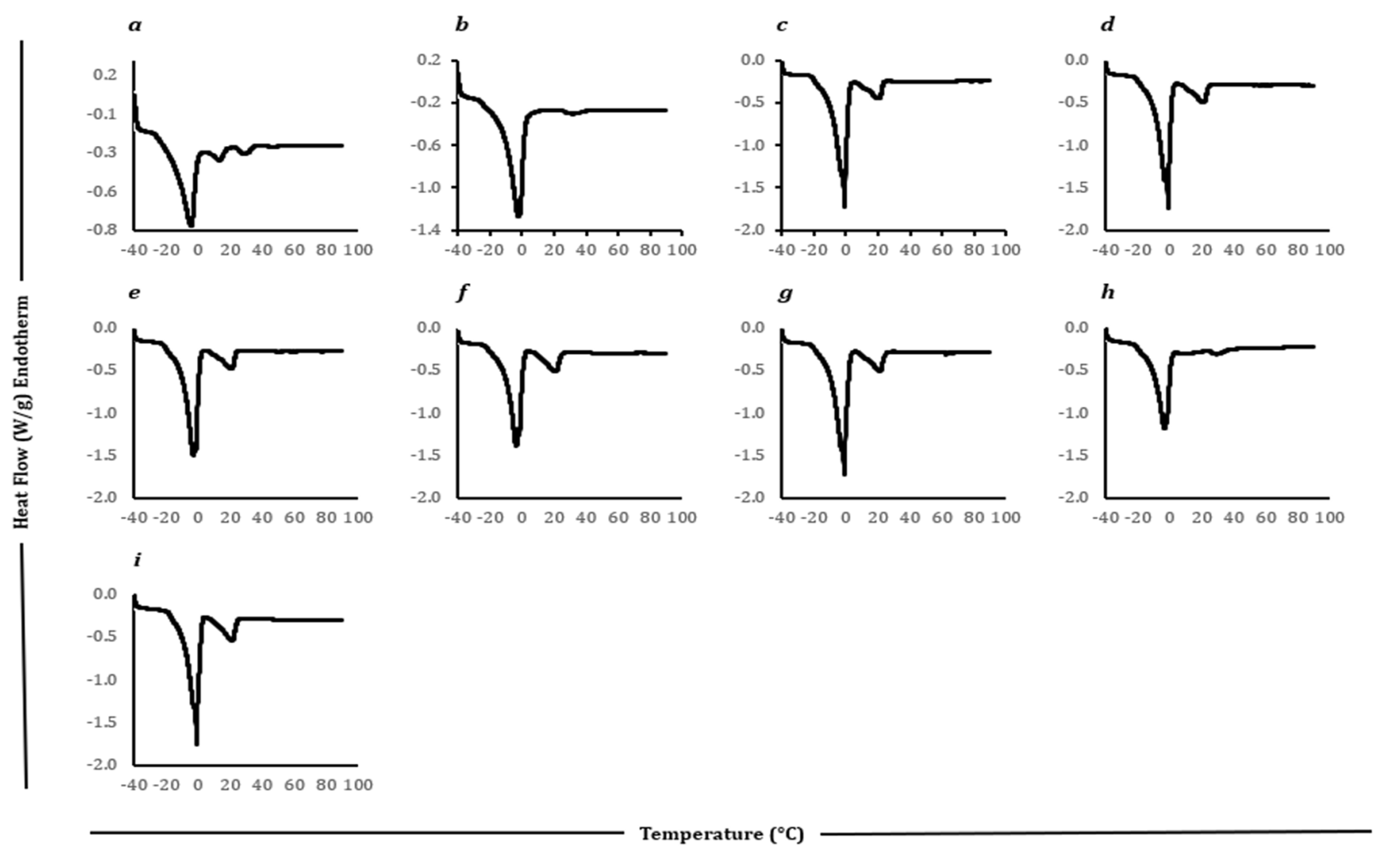

Figure 8.

Differential scanning calorimetry thermograms of heating ramp from −40 to 90°C for Slice style cheddar (a), processed (b), plant 1 (c), plant 2 (d), plant 3 (e), plant 4 (f), plant 5 (g), plant 6 (h) and plant 7 (i) products.

Figure 8.

Differential scanning calorimetry thermograms of heating ramp from −40 to 90°C for Slice style cheddar (a), processed (b), plant 1 (c), plant 2 (d), plant 3 (e), plant 4 (f), plant 5 (g), plant 6 (h) and plant 7 (i) products.

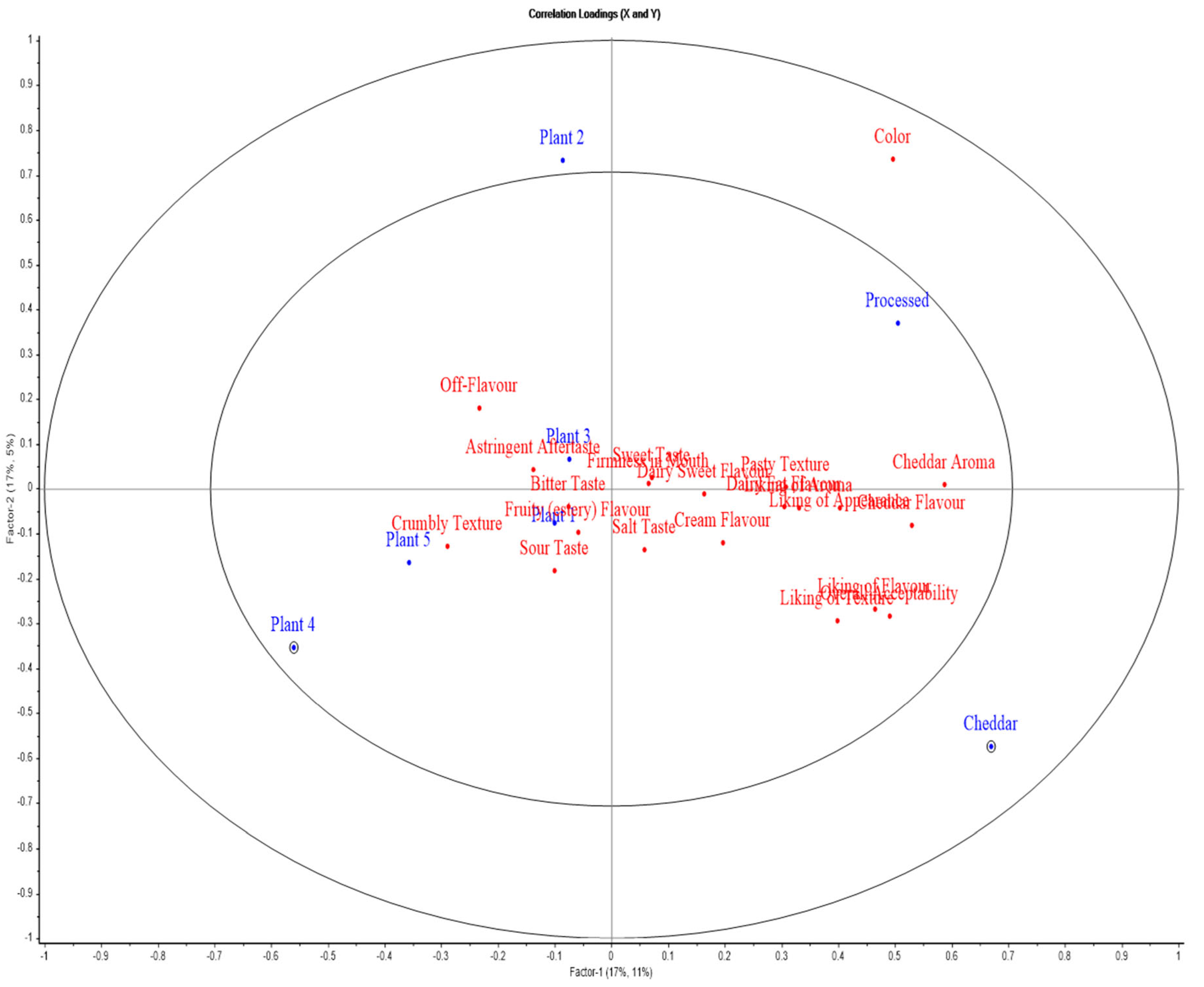

Figure 9.

APLSR graph for sensory evaluation of block-style products. Plotted are cheese variants verses sensory (hedonic and descriptive) attributes.

Figure 9.

APLSR graph for sensory evaluation of block-style products. Plotted are cheese variants verses sensory (hedonic and descriptive) attributes.

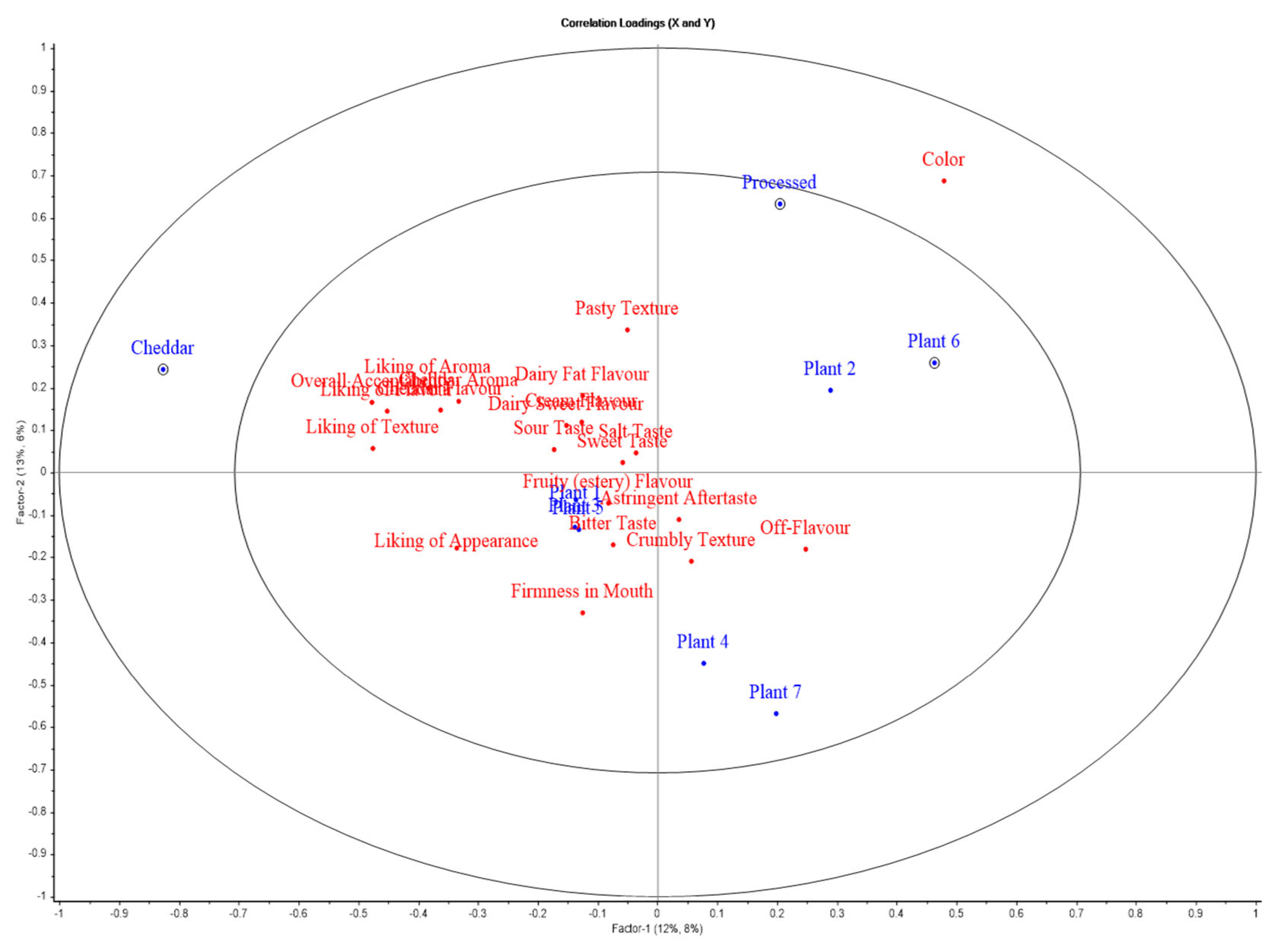

Figure 10.

APLSR graph for sensory evaluation of slice style products. Plotted are cheese variants verses sensory (hedonic and descriptive) attributes.

Figure 10.

APLSR graph for sensory evaluation of slice style products. Plotted are cheese variants verses sensory (hedonic and descriptive) attributes.

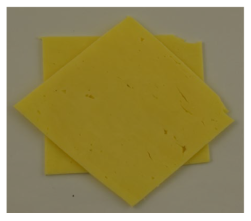

Table 1.

List of ingredients and images for Block style products.

Table 1.

List of ingredients and images for Block style products.

| Products |

Ingredients |

Pictures |

| Cheddar |

Milk, rennet, salt |

|

| Processed |

Cheese (60%), water, vegetable oils (coconut, palm), milk protein, emulsifying salts (sodium phosphates, sodium polyphosphate), modified maize starch, whey powder (milk), tri-calcium phosphate, acidity regulator (citric acid), colour (paprika, carotene) |

|

| Plant 1 |

Water, coconut oil (24%), modified starch, starch, sea salt, lentil protein, cheddar flavour, acidity regulator (lactic acid), olive extract, colour (beta-carotene), vitamin B12 |

|

| Plant 2 |

Water, coconut oil (21%), modified starch, starch, sea salt, cheddar flavour, olive extract, colour (beta-carotene, paprika extract, vitamin B12 |

|

| Plant 3 |

Water, coconut oil (24%), maize starch, modified maize starch, modified potato starch, modified tapioca starch, sea salt, flavouring, olive extract, colour (carotenes), vitamin B12 |

|

| Plant 4 |

Water, coconut oil (25%) (non-hydrogenated), starch, sea salt, potato protein, acidity regulator (lactic acid) (non-dairy), vegan flavourings, olive extract, vitamin B12 |

|

| Plant 5 |

Water, coconut oil (24%) (non-hydrogenated), modified starch, starch, tapioca maltodextrin, sea salt, vegan natural flavourings, olive extract, colour (natural beta-carotene), vitamin B12 |

|

Table 2.

List of ingredients and images for Slice style products.

Table 2.

List of ingredients and images for Slice style products.

| Products |

Ingredients |

Pictures |

| Cheddar |

Milk, rennet, salt |

|

| Processed |

Cheese (60%), water, palm oil, milk protein, modified potato starch, emulsifying salts (E452, E339), calcium phosphate, salt, acidity regulator (lactic acid) (milk), flavouring (milk), natural colours (beta carotene, paprika extract) |

|

| Plant 1 |

Water, coconut oil (23%), modified starch, starch, sea salt, flavouring, olive extract, colour (beta-carotene), vitamin B12 |

|

| Plant 2 |

Water, coconut oil (23%), modified starch, starch, sea salt, cheddar flavour, olive extract, colour (beta-carotene, paprika), vitamin B12 |

|

| Plant 3 |

Water, coconut oil (23%), modified starch, starch, sea salt, smoke flavour, olive extract, colour (beta-carotene), vitamin B12 |

|

| Plant 4 |

Water, coconut oil (25%), modified potato starch, salt, calcium lactate, preservative (sorbic acid), natural flavouring, natural colour (beta-carotene), iron, vitamin D2, B6 & B12 |

|

| Plant 5 |

Water, coconut oil (24%) (non-hydrogenated), modified starch, sea salt, olive extract, vegan flavourings, colour (natural beta-carotene), vitamin B12 |

|

| Plant 6 |

Water, shea oil, coconut oil, modified starch, salt, flavouring, lemon juice powder, spice extract, colour (beta-carotene) |

|

| Plant 7 |

Water, coconut oil (24%) (non-hydrogenated), modified starch, sea salt, olive extract, vegan flavourings, colour (natural beta-carotene), vitamin B12 |

|

Table 3.

Chemical composition, pH, water activity, and meltability of Block-style products.

Table 3.

Chemical composition, pH, water activity, and meltability of Block-style products.

| |

Cheddar |

Processed |

Plant 1 |

Plant 2 |

Plant 3 |

Plant 4 |

Plant 5 |

| Protein (%) |

25.6 ± 0.1a

|

18.5 ± 0.1b

|

1.2 ± 0.0d

|

0.1 ± 0.0e

|

0.1 ± 0.0e

|

1.7 ± 0.0c

|

0.1 ± 0.0e

|

| Fat (%) |

34.8 ± 0.8a

|

24.9 ± 0.2c

|

23.8 ± 0.2d

|

21.1 ± 0.2f

|

22.6 ± 0.4e

|

24.2 ± 0.8cd

|

26.6 ± 0.1b

|

| Moisture (%) |

38.0 ± 0.1g

|

47.8 ± 0.1f

|

50.7 ± 0.0d

|

53.2 ± 0.1b

|

51.9 ± 0.1c

|

56.9 ± 0.1a

|

46.9 ± 0.1e

|

| Ash (%) |

3.8 ± 0.0b

|

4.5 ± 0.0a

|

2.4 ± 0.1c

|

2.2 ± 0.1d

|

2.1 ± 0.0d

|

2.4 ± 0.0c

|

2.2 ± 0.0d

|

| CHO* (%) |

< 0.0e

|

4.8 ± 0.2d

|

21.9 ± 0.3b

|

23.4 ± 0.2a

|

23.3 ± 0.4ab

|

14.9 ± 0.8c

|

24.2 ± 0.1a

|

| pH |

5.28 ± 0.0b

|

6.03 ± 0.0a

|

4.06 ± 0.0d

|

3.56 ± 0.0e

|

4.01 ± 0.0d

|

3.50 ± 0.0f

|

4.20 ± 0.0c

|

| Water activity |

0.95 ± 0.0c

|

0.98 ± 0.0a

|

0.98 ± 0.0ab

|

0.98 ± 0.0ab

|

0.96 ± 0.0bc

|

0.98 ± 0.0a

|

0.96 ± 0.0bc

|

| Meltability (%) |

81.7 ± 4.4a

|

2.2 ± 0.4c

|

6.7 ± 1.7c

|

2.2 ± 2.6c

|

3.3 ± 1.7c

|

17.2 ± 7.5b

|

0.0d

|

Table 4.

Chemical composition, pH, water activity, and meltability of Slice-style products.

Table 4.

Chemical composition, pH, water activity, and meltability of Slice-style products.

| |

Cheddar |

Processed |

Plant 1 |

Plant 2 |

Plant 3 |

Plant 4 |

Plant 5 |

Plant 6 |

Plant 7 |

| Protein (%) |

25.2 ± 0.4a

|

12.9 ± 0.0b

|

0.1 ± 0.0c |

0.1 ± 0.0c |

0.1 ± 0.0c |

0.1 ± 0.0c

|

0.1 ± 0.0c |

0.2 ± 0.0c

|

0.2 ± 0.0c

|

| Fat (%) |

35.0 ± 0.5a

|

20.5 ± 0.8f

|

22.5 ± 0.3de

|

22.7 ± 0.1de

|

21.6 ± 0.3e

|

25.3 ± 0.4c

|

22.9 ± 0.35d

|

32.0 ± 0.1b

|

25.8 ± 0.0c

|

| Moisture (%) |

37.5 ± 0.0h

|

53.4 ± 0.0a

|

52.9 ± 0.2b

|

52.4± 0.0c

|

52.6 ± 0.0c

|

48.2 ± 0.1e

|

51.8± 0.0d

|

42.7 ± 0.1g

|

47.3 ± 0.0f

|

| Ash (%) |

3.7 ± 0.0b

|

5.7 ± 0.0a

|

2.3 ± 0.0d

|

2.3 ± 0.0d

|

2.4 ± 0.0d

|

2.6 ± 0.1c

|

2.3 ± 0.1d

|

2.2 ± 0.1d

|

1.8 ± 0.0e

|

| CHO* (%) |

<0.0e

|

7.8 ± 0.8d

|

22.1 ± 0.5c

|

22.6 ± 0.1c

|

23.3 ± 0.4bc

|

23.8 ± 0.5ab

|

22.8 ± 0.4bc

|

22.9 ± 0.3bc

|

24.9 ± 0.1a

|

| pH |

5.32 ± 0.0a

|

6.00 ± 0.0b

|

4.10 ± 0.0e

|

4.05 ± 0.0f

|

3.91 ± 0.0g

|

4.71 ± 0.0c

|

3.89 ± 0.0h

|

4.49 ± 0.0d

|

4.47 ± 0.0d

|

| Water activity |

0.95 ± 0.0e

|

0.97 ± 0.0bcd

|

0.97 ± 0.0ab

|

0.98 ± 0.0a

|

0.97 ± 0.0abcd

|

0.97 ± 0.0abcd

|

0.96 ± 0.0cd

|

0.97 ± 0.0abc

|

0.96 ± 0.0d

|

| Meltability (%) |

83.3 ± 3.3a

|

4.0 ± 0.0d

|

1.7 ± 0.0d

|

1.8 ± 0.2d

|

1.7 ± 0.0d

|

34.5 ± 2.6c

|

2.2 ± 0.9c

|

46.1 ± 1.9b

|

1.7 ± 0.0c

|

Table 5.

Colour space values (L*, a*, b*) before and after melting for Block-style products.

Table 5.

Colour space values (L*, a*, b*) before and after melting for Block-style products.

| |

Cheddar |

Processed |

Plant 1 |

Plant 2 |

Plant 3 |

Plant 4 |

Plant 5 |

| Before melting |

| L* |

83.3 ± 0.2e

|

76.7 ± 1.1g

|

88.2 ± 0.1d

|

79.8 ± 0.4f

|

90.0 ± 0.1c

|

93.6 ± 0.4a

|

92.1 ± 0.1b

|

| a* |

-3.6 ± 0.1f

|

9.1 ± 0.2b

|

-1.6 ± 0.0d

|

10.3 ± 0.1a

|

-4.2 ± 0.0g

|

-1.3 ± 0.0c

|

-2.3 ± 0.0e

|

| b* |

28.6 ± 0.5e

|

47.6 ± 0.2b

|

29.5 ± 0.3d

|

50.6 ± 0.5a

|

34.5 ± 0.1c

|

7.7 ± 0.1g

|

16.5 ± 0.1f

|

| After melting |

| L* |

73.7 ± 0.9e

|

67.5 ± 0.4f |

77.7 ± 0.4d

|

68.2 ± 4.1b

|

78.7 ± 0.9c

|

88.5 ± 0.3a

|

81.9 ± 0.5b

|

| a* |

-6.3 ± 0.1g

|

8.8 ± 0.4b |

-1.9 ± 0.1d

|

15.5 ± 0.2a

|

-5.8 ± 0.1f

|

-1.2 ± 0.0c

|

-4.2 ± 0.0e

|

| b* |

27.8 ± 0.6d |

52.3 ± 0.2b

|

51.1 ± 0.5c

|

68.6 ± 2.0a

|

53.8 ± 0.7b

|

11.3 ± 0.2f

|

22.3 ± 0.1e |

Table 6.

Colour space values (L*, a*, b*) before and after melting for Slice-style products.

Table 6.

Colour space values (L*, a*, b*) before and after melting for Slice-style products.

| |

Cheddar |

Processed |

Plant 1 |

Plant 2 |

Plant 3 |

Plant 4 |

Plant 5 |

Plant 6 |

Plant 7 |

| Before melting |

| L* |

81.7 ± 0.4f

|

80.6 ± 0.3g

|

86.9 ± 0.1c

|

79.2 ± 0.1h

|

85.8 ± 0.1e

|

88.1 ±0.0a

|

87.4 ± 0.1b

|

75.4 ± 0.2i

|

86.7 ± 0.1d

|

| a* |

-3.9 ± 0.01e

|

11.4 ± 0.2b

|

-5.2 ± 0.0h

|

9.0 ± 0.1c

|

-4.1 ± 0.1f

|

-3.0 ±0.0d

|

-4.9 ± 0.1g

|

17.5 ± 0.1a

|

-3.9 ± 0.0e

|

| b* |

30.4 ± 0.3f

|

45.9 ± 0.2b

|

35.8 ± 0.1d

|

51.5 ± 0.1a

|

35.6 ± 0.3d

|

32.4 ± 0.0f

|

34.6 ± 0.1e

|

44.5 ± 0.8c

|

23.9 ± 0.0g

|

| After melting |

| L* |

70.9 ± 0.6e

|

77.5 ± 0.8b

|

76.6 ± 1.2bc

|

63.7 ± 0.0f

|

75.9 ± 0.1c

|

81.5 ±1.1a

|

73.8 ± 0.3d

|

64.5 ± 0.4f

|

70.4 ± 0.0e

|

| a* |

-6.4 ± 0.0g

|

17.8 ± 0.2b

|

-5.4 ± 0.1f

|

15.0 ± 0.1c

|

-4.1 ± 0.0d

|

-6.2 ±0.0g

|

-3.9 ± 0.0d

|

21.8 ± 0.2a

|

-5.1 ± 0.0e

|

| b* |

30.9 ± 0.7g

|

67.8 ± 0.6a

|

54.2 ± 0.6e

|

61.4 ± 0.1b

|

53.9 ± 0.1d

|

53.1 ±0.3de

|

53.5 ± 0.2de

|

58.2 ± 0.8c

|

33.1 ± 0.0f

|

Table 7.

Rheological parameters storage modulus (G’), loss modulus (G’’) at 20°C and 90°C, maximum loss tangent (Tan δmax), texture profile analysis parameters; hardness, adhesiveness, springiness and cohesiveness of block-style products.

Table 7.

Rheological parameters storage modulus (G’), loss modulus (G’’) at 20°C and 90°C, maximum loss tangent (Tan δmax), texture profile analysis parameters; hardness, adhesiveness, springiness and cohesiveness of block-style products.

| |

Cheddar |

Processed |

Plant 1 |

Plant 2 |

Plant 3 |

Plant 4 |

Plant 5 |

| Hardness (N) |

179.2 ± 2.4a

|

80.8 ± 1.6f

|

105.9 ± 0.6e

|

145.3 ± 2.3b

|

131.5 ± 0.6c

|

65.7 ± 0.7g

|

124.5 ± 2.2d

|

| Adhesiveness (N.s) |

11.1 ± 0.8b

|

16.1 ± 4.1c

|

0.8 ± 0.3a

|

2.1 ± 0.7a

|

4.5 ± 0.4a

|

1.3 ± 0.1a

|

5.1 ± 0.8a

|

| Springiness (-) |

0.2 ± 0.0ab

|

0.1 ± 0.0b

|

0.4 ± 0.1ab |

0.5 ± 0.2a

|

0.4 ± 0.2ab

|

0.2 ± 0.0ab

|

0.2 ± 0.1ab

|

| Cohesiveness (-) |

0.1 ± 0.0c

|

0.1 ± 0.0c

|

0.1 ± 0.0b

|

0.1 ± 0.0a

|

0.1 ± 0.0b

|

0.1 ± 0.0d

|

0.1 ± 0.0d |

|

G’ (20°C)

|

56.9 ± 5.6bc

|

15.1 ± 0.9d

|

34.7 ± 4.3cd |

23.4 ± 2.8d

|

47.3 ± 0.2bc

|

86.1 ± 16.5a

|

70.5 ± 12.9ab

|

|

G’’ (20°C)

|

15.1 ± 0.8a

|

3.3 ±0.5c

|

4.7 ± 0.8c

|

1.9 ± 0.5c

|

4.4 ± 0.4c

|

8.8 ± 2.3b

|

9.5 ± 2.2b

|

|

G’ (90°C)

|

0.1 ± 0.0d

|

2.7 ± 0.7a

|

0.2 ± 0.0d

|

1.2 ± 0.1bc

|

0.7 ± 0.1cd

|

1.9 ± 0.2b

|

1.4 ± 0.3bc

|

|

G’’ (90°C)

|

0.1 ± 0.0bc

|

0.8 ± 0.2a

|

0.0 ± 0.0c

|

0.3 ± 0.0b

|

0.2 ± 0.0bc

|

0.3 ± 0.0bc

|

0.3 ± 0.1bc

|

| Tan δ max |

1.9 ± 0.0a

|

0.4 ± 0.0b

|

0.2 ± 0.0d

|

0.3 ± 0.0c

|

0.2 ± 0.0cd

|

0.1 ± 0.0e

|

0.2 ± 0.0de

|

Table 8.

Rheological parameters storage modulus (G’), loss modulus (G’’) at 20°C and 90°C, maximum loss tangent (Tan δmax) and uniaxial compression testing parameters; hardness of slice-style products.

Table 8.

Rheological parameters storage modulus (G’), loss modulus (G’’) at 20°C and 90°C, maximum loss tangent (Tan δmax) and uniaxial compression testing parameters; hardness of slice-style products.

| |

Cheddar |

Processed |

Plant 1 |

Plant 2 |

Plant 3 |

Plant 4 |

Plant 5 |

Plant 6 |

Plant 7 |

| Hardness (N) |

3.4 ± 0.0ef

|

0.6 ± 0.0h

|

2.8 ± 0.0g

|

3.6 ± 0.0d

|

3.3 ± 0.0f

|

4.7 ± 0.0b

|

3.5 ± 0.0e

|

6.6 ± 0.1a

|

3.8 ± 0.0c

|

|

G’ (20°C)

|

119.4 ± 16.7b

|

11.7 ± 2.4f

|

57.5 ± 7.1de

|

94.3 ± 21.2bcd

|

49.6 ± 5.1ef

|

72.4 ± 6.7cde

|

106.8 ± 21.5bc

|

290.4 ± 14.9a

|

85.9 ± 7.8bcde

|

|

G’’ (20°C)

|

32.3 ± 4.3b

|

4.3 ± 0.2de

|

4.5 ± 1.6 cd

|

13.9 ± 5.8bc

|

2.8 ± 0.3e |

9.7 ± 1.6bcd

|

15.6 ± 4.7c

|

45.9 ± 5.7a

|

11.9 ± 0.3bcd

|

|

G’ (90°C)

|

0.0 ± 0.0d

|

0.7 ± 0.1cd

|

1.9 ± 0.4a

|

1.3 ± 0.4abc

|

1.5 ± 0.1ab

|

1.5 ± 0.2ab

|

1.2 ± 0.4bc

|

0.4 ± 0.0d

|

1.4 ± 0.2ab

|

|

G’’ (90°C)

|

0.1 ± 0.0b

|

0.3 ± 0.0ab

|

0.5 ± 0.1a

|

0.3 ± 0.1ab

|

0.3 ± 0.1ab

|

0.4 ± 0.1a

|

0.2 ± 0.1ab

|

0.1 ± 0.0b

|

0.2 ± 0.1ab

|

| Tan δ max |

2.5 ± 0.4a

|

0.6 ± 0.0b

|

0.2 ± 0.0c

|

0.2 ± 0.3c

|

0.2 ± 0.0c

|

0.2 ± 0.0c

|

0.2 ± 0.0c

|

0.2 ± 0.0c

|

0.2 ± 0.0c

|

Table 9.

Beta coefficient values for Block style dairy and plant-based cheese analogues.

Table 9.

Beta coefficient values for Block style dairy and plant-based cheese analogues.

| |

Liking of Appearance |

Liking of Aroma |

Liking of Flavour |

Liking of Texture |

Overall Acceptability |

Colour |

Cheddar Aroma |

Firmness in Mouth |

Pasty Texture |

Crumbly Texture |

Sweet Taste |

Salt Taste |

Sour Taste |

Bitter Taste |

Cream Flavour |

Cheddar Flavour |

Dairy Sweet Flavour |

Dairy Fat Flavour |

Fruity (estery) Flavour |

Off-Flavour |

Astringent Aftertaste |

| Cheddar |

1.83 |

1.49 |

2.21 |

1.83 |

2.28 |

2.63 |

2.62 |

0.29 |

1.48 |

-1.42 |

0.28 |

0.22 |

-0.47 |

-0.31 |

0.85 |

2.43 |

0.67 |

1.25 |

-0.27 |

-1.22 |

-0.65 |

| Processed |

0.13 |

0.09 |

0.15 |

0.08 |

0.14 |

0.50 |

0.20 |

-0.25 |

0.29 |

-0.21 |

-0.05 |

-0.01 |

0.00 |

-0.03 |

0.06 |

0.18 |

0.03 |

0.07 |

-0.08 |

-0.07 |

0.00 |

| Plant 1 |

-0.27 |

-0.22 |

-0.33 |

-0.27 |

-0.34 |

-0.39 |

-0.39 |

-0.04 |

-0.22 |

0.21 |

-0.04 |

-0.03 |

0.07 |

0.05 |

-0.13 |

-0.36 |

-0.10 |

-0.19 |

0.04 |

0.18 |

0.10 |

| Plant 2 |

-0.23 |

-0.19 |

-0.28 |

-0.23 |

-0.29 |

-0.34 |

-0.33 |

-0.04 |

-0.19 |

0.18 |

-0.04 |

-0.03 |

0.06 |

0.04 |

-0.11 |

-0.31 |

-0.09 |

-0.16 |

0.03 |

0.16 |

0.08 |

| Plant 3 |

-0.20 |

-0.16 |

-0.24 |

-0.20 |

-0.25 |

-0.29 |

-0.29 |

-0.03 |

-0.16 |

0.16 |

-0.03 |

-0.02 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

-0.09 |

-0.27 |

-0.07 |

-0.14 |

0.03 |

0.14 |

0.07 |

| Plant 4 |

-1.53 |

-1.24 |

-1.84 |

-1.53 |

-1.91 |

-2.20 |

-2.19 |

-0.24 |

-1.24 |

1.18 |

-0.24 |

-0.18 |

0.40 |

0.26 |

-0.71 |

-2.04 |

-0.56 |

-1.05 |

0.22 |

1.02 |

0.55 |

| Plant 5 |

-0.98 |

-0.79 |

-1.17 |

-0.97 |

-1.21 |

-1.40 |

-1.40 |

-0.15 |

-0.79 |

0.75 |

-0.15 |

-0.12 |

0.25 |

0.17 |

-0.45 |

-1.30 |

-0.36 |

-0.67 |

0.14 |

0.65 |

0.35 |

Table 10.

P-Values of Beta Coefficients (Figures shaded in green and red represented positive and negative significant correlations [+/- (P<0.05) respectively, for Block style products.

Table 10.

P-Values of Beta Coefficients (Figures shaded in green and red represented positive and negative significant correlations [+/- (P<0.05) respectively, for Block style products.

| |

Liking of Appearance |

Liking of Aroma |

Liking of Flavour |

Liking of Texture |

Overall Acceptability |

Colour |

Cheddar Aroma |

Firmness in Mouth |

Pasty Texture |

Crumbly Texture |

Sweet Taste |

Salt Taste |

Sour Taste |

Bitter Taste |

Cream Flavour |

Cheddar Flavour |

Dairy Sweet Flavour |

Dairy Fat Flavour |

Fruity (estery) Flavour |

Off-Flavour |

Astringent Aftertaste |

| Cheddar |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.25 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.20 |

0.75 |

0.61 |

0.08 |

0.11 |

0.65 |

0.02 |

0.00 |

0.14 |

0.00 |

0.43 |

0.00 |

0.23 |

| Processed |

0.12 |

0.33 |

0.01 |

0.38 |

0.06 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.72 |

0.69 |

0.06 |

0.10 |

0.30 |

0.00 |

0.68 |

0.24 |

0.07 |

0.17 |

0.51 |

| Plant 1 |

0.55 |

0.64 |

0.57 |

0.73 |

0.59 |

0.07 |

0.49 |

0.40 |

0.33 |

0.68 |

0.56 |

0.94 |

0.78 |

0.90 |

0.82 |

0.51 |

0.96 |

0.84 |

0.74 |

0.72 |

0.79 |

| Plant 2 |

0.62 |

0.99 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.53 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.38 |

0.97 |

0.37 |

0.84 |

0.42 |

0.10 |

0.19 |

0.87 |

0.46 |

0.96 |

0.03 |

0.26 |

| Plant 3 |

0.80 |

0.56 |

0.20 |

0.24 |

0.12 |

0.36 |

0.49 |

0.13 |

0.37 |

0.50 |

0.10 |

0.36 |

0.12 |

0.29 |

0.92 |

0.64 |

0.68 |

0.56 |

0.69 |

0.58 |

0.32 |

| Plant 4 |

0.02 |

0.06 |

0.07 |

0.19 |

0.08 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.71 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.61 |

0.00 |

0.11 |

0.36 |

0.00 |

0.06 |

0.00 |

0.38 |

0.53 |

0.05 |

| Plant 5 |

0.08 |

0.09 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.15 |

0.02 |

0.34 |

0.33 |

0.65 |

0.05 |

0.28 |

0.61 |

0.01 |

0.64 |

0.35 |

0.92 |

0.35 |

0.38 |

Table 11.

Beta coefficient values for Slice style dairy and plant-based cheese analogues.

Table 11.

Beta coefficient values for Slice style dairy and plant-based cheese analogues.

| |

Liking of Appearance |

Liking of Aroma |

Liking of Flavour |

Liking of Texture |

Overall Acceptability |

Colour |

Cheddar Aroma |

Firmness in Mouth |

Pasty Texture |

Crumbly Texture |

Sweet Taste |

Salt Taste |

Sour Taste |

Bitter Taste |

Cream Flavour |

Cheddar Flavour |

Dairy Sweet Flavour |

Dairy Fat Flavour |

Fruity (estery) Flavour |

Off-Flavour |

Astringent Aftertaste |

| Cheddar |

1.98 |

2.44 |

2.95 |

3.12 |

3.19 |

-3.35 |

2.04 |

0.77 |

0.31 |

-0.35 |

0.29 |

0.21 |

0.97 |

0.43 |

0.73 |

2.09 |

0.80 |

0.75 |

0.46 |

-1.89 |

-0.24 |

| Processed |

-0.49 |

-0.60 |

-0.72 |

-0.76 |

-0.78 |

0.82 |

-0.50 |

-0.19 |

-0.07 |

0.09 |

-0.07 |

-0.05 |

-0.24 |

-0.11 |

-0.18 |

-0.51 |

-0.20 |

-0.18 |

-0.11 |

0.46 |

0.06 |

| Plant 1 |

0.33 |

0.41 |

0.49 |

0.52 |

0.53 |

-0.56 |

0.34 |

0.13 |

0.05 |

-0.06 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

0.16 |

0.07 |

0.12 |

0.35 |

0.13 |

0.13 |

0.08 |

-0.32 |

-0.04 |

| Plant 2 |

-0.69 |

-0.84 |

-1.02 |

-1.08 |

-1.11 |

1.16 |

-0.71 |

-0.27 |

-0.11 |

0.12 |

-0.10 |

-0.07 |

-0.33 |

-0.15 |

-0.25 |

-0.72 |

-0.28 |

-0.26 |

-0.16 |

0.66 |

0.08 |

| Plant 3 |

0.33 |

0.41 |

0.50 |

0.52 |

0.54 |

-0.56 |

0.34 |

0.13 |

0.05 |

-0.06 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

0.16 |

0.07 |

0.12 |

0.35 |

0.14 |

0.13 |

0.08 |

-0.32 |

-0.04 |

| Plant 4 |

-0.19 |

-0.24 |

-0.28 |

-0.30 |

-0.31 |

0.32 |

-0.20 |

-0.07 |

-0.03 |

0.03 |

-0.03 |

-0.02 |

-0.09 |

-0.04 |

-0.07 |

-0.20 |

-0.08 |

-0.07 |

-0.04 |

0.18 |

0.02 |

| Plant 5 |

0.32 |

0.40 |

0.48 |

0.51 |

0.52 |

-0.54 |

0.33 |

0.13 |

0.05 |

-0.06 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

0.16 |

0.07 |

0.12 |

0.34 |

0.13 |

0.12 |

0.07 |

-0.31 |

-0.04 |

| Plant 6 |

-1.10 |

-1.36 |

-1.64 |

-1.73 |

-1.77 |

1.86 |

-1.13 |

-0.43 |

-0.17 |

0.20 |

-0.16 |

-0.12 |

-0.54 |

-0.24 |

-0.40 |

-1.16 |

-0.45 |

-0.42 |

-0.25 |

1.05 |

0.13 |

| Plant 7 |

-0.47 |

-0.58 |

-0.70 |

-0.74 |

-0.75 |

0.79 |

-0.48 |

-0.18 |

-0.07 |

0.08 |

-0.07 |

-0.05 |

-0.23 |

-0.10 |

-0.17 |

-0.49 |

-0.19 |

-0.18 |

-0.11 |

0.45 |

0.06 |

Table 12.

P-Values of Beta Coefficients (Figures shaded in green and red represented positive and negative significant correlations [+/- (P<0.05) respectively, for Slice style products.

Table 12.

P-Values of Beta Coefficients (Figures shaded in green and red represented positive and negative significant correlations [+/- (P<0.05) respectively, for Slice style products.

| |

Liking of Appearance |

Liking of Aroma |

Liking of Flavour |

Liking of Texture |

Overall Acceptability |

Colour |

Cheddar Aroma |

Firmness in Mouth |

Pasty Texture |

Crumbly Texture |

Sweet Taste |

Salt Taste |

Sour Taste |

Bitter Taste |

Cream Flavour |

Cheddar Flavour |

Dairy Sweet Flavour |

Dairy Fat Flavour |

Fruity (estery) Flavour |

Off-Flavour |

Astringent Aftertaste |

| Cheddar |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.08 |

0.09 |

0.93 |

0.62 |

0.21 |

0.00 |

0.19 |

0.03 |

0.00 |

0.06 |

0.01 |

0.25 |

0.00 |

0.87 |

| Processed |

0.01 |

0.53 |

0.73 |

0.11 |

0.99 |

0.00 |

0.24 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.84 |

0.50 |

0.82 |

0.00 |

0.33 |

0.36 |

0.33 |

0.06 |

0.51 |

0.34 |

0.11 |

| Plant 1 |

0.40 |

0.21 |

0.21 |

0.71 |

0.27 |

0.00 |

0.83 |

0.82 |

0.43 |

0.14 |

0.69 |

0.63 |

0.20 |

0.25 |

0.53 |

0.26 |

0.37 |

0.88 |

0.33 |

0.08 |

0.24 |

| Plant 2 |

0.07 |

0.82 |

0.04 |

0.07 |

0.07 |

0.00 |

0.72 |

0.10 |

0.04 |

0.10 |

0.91 |

0.48 |

0.03 |

0.10 |

0.35 |

0.09 |

0.55 |

0.41 |

0.09 |

0.50 |

0.58 |

| Plant 3 |

0.07 |

0.61 |

0.46 |

0.43 |

0.50 |

0.00 |

0.81 |

0.21 |

0.31 |

0.95 |

0.65 |

0.78 |

0.90 |

0.81 |

0.83 |

0.93 |

0.70 |

0.76 |

0.86 |

0.69 |

0.92 |

| Plant 4 |

0.18 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

0.34 |

0.04 |

0.00 |

0.10 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.05 |

0.62 |

0.63 |

0.78 |

0.09 |

0.59 |

0.56 |

0.08 |

0.14 |

0.32 |

0.02 |

0.10 |

| Plant 5 |

0.10 |

0.49 |

0.30 |

0.46 |

0.40 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

0.61 |

0.54 |

0.59 |

0.67 |

0.62 |

0.70 |

0.92 |

0.73 |

0.81 |

0.50 |

0.83 |

0.98 |

0.52 |

0.68 |

| Plant 6 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.71 |

0.47 |

0.47 |

0.05 |

0.52 |

0.53 |

0.44 |

0.60 |

0.90 |

0.78 |

0.13 |

0.87 |

0.98 |

0.05 |

0.33 |

| Plant 7 |

0.47 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.03 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.18 |

0.02 |

0.24 |

0.70 |

0.24 |

0.53 |

0.20 |

0.19 |

0.02 |

0.14 |

0.05 |

0.37 |

0.03 |

0.23 |