1. Introduction

Obesity and overweight occur due to an imbalance between energy intake (diet) and energy expenditure (physical activity). High-fat diets are associated with an increased risk of obesity, which in turn elevates the risk of various chronic diseases [

1]. In particular, the fat consumed in snacks contributes to excessive energy intake, promoting weight gain. While reducing fat intake is an important strategy for addressing obesity, such reductions may not be well accepted by consumers due to a potential decrease in the sensory quality, such as texture and flavor, of food products. Therefore, the use of fat replacers to reduce the fat content in foods offers the potential to lower the caloric content, which can significantly affect health maintenance by altering the energy density of specific foods [

2].

Fat replacers provide some or all of the functions of fat while producing fewer calories. These ingredients mimic the physicochemical and sensory properties of fats in food. Fat replacers are typically categorized into three groups based on their composition: carbohydrate-based, protein-based, and fat-based [

3]. Carbohydrate-based fat replacers include dextrin, modified starch, cellulose, fruit-based fibers, hydrocolloid gums, maltodextrin, pectin, and polydextrose. These replacers primarily absorb water and form gels, typically providing only 1–2 kcal/g. Protein-based fat replacers, such as microparticulate protein and modified whey protein concentrate, provide a creamy texture similar to fat, offering 1–4 kcal/g. Fat-based replacers, like altered triglycerides and sucrose polyester, contain short-, medium-, and long-chain fatty acids randomly distributed on a glycerol backbone, and provide 5 kcal/g. Most fat-based replacers are heat-stable and versatile in use [

2,

3].

In this study, maltodextrin, whey protein isolate (WPI), and medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) were selected as fat replacers. Madeleines were chosen as the application model due to their relatively high fat content compared to other baked products. Maltodextrin has been shown to reduce overall quality when replacing more than 60% of fat, with 70–80% substitution leading to undesirable stickiness and unacceptable cake texture. Additionally, complete fat replacement (100%) significantly reduces consumer acceptance in baked products, suggesting that full-fat replacement is not recommended [

4,

5]. Substituting 12.5–25% of fat with WPI causes minimal changes in dough density, volume, texture, crystallinity, and sensory characteristics. However, replacing more than 80% of fat with WPI leads to an increase in cake volume, but the cake becomes heavier and firmer due to the heat-induced coagulation of WPI, rather than remaining soft [

6,

7]. For MCT, a 33% substitution is considered optimal, while complete fat replacement (100%) results in a less oily or moist texture, which could lead to consumer rejection [

8]. Reduced-fat cookies made with blended carbohydrate- or protein-based fat replacers have been reported to exhibit superior textural properties compared to full-fat versions [

9].

As evidenced by previous studies, fat contributes significantly to the flavor and texture of most foods [

2], particularly in baked products, fat substitution has a greater impact on texture than substituting sugar or flour [

9,

10]. The studies mentioned above utilized either single fat replacers or binary mixtures and thus did not compare the effects of triple blends. To cater to a diverse consumer base, it is essential to evaluate the effects of fat replacers based on their composition and the combined effects of blended replacers. This approach will allow for the optimization of product quality, ensuring that physicochemical and sensory characteristics resemble those of full-fat foods. Therefore, in this study, maltodextrin, WPI, and MCT were used as carbohydrate-based, protein-based, and fat-based fat replacers, respectively. The effects of single, double, and triple blends of these replacers on the characteristics of madeleines were investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Meaterials

The ingredients used in this study were as follows: butter (Anchor Butter, Fonterra, New Zealand), flour (Soft Flour, CJ CheilJedang, Korea), eggs (Healthy Eggs, Pulmuone, Korea), sugar (White Sugar, CJ CheilJedang, Korea), baking powder (Good Baking Powder, Bread Garden, Korea), lemon juice (Squeezed Lemon, Solimon, Spain), salt (Sea Salt, Chungjungone, Korea), maltodextrin (Nutricost, UT, USA), WPI (Marron Foods, NY, USA), and MCT (Bioriginal, Canada). Maltodextrin (MD) and whey protein isolated (WPI) were hydrated at concentrations of 20% and 30%, respectively, to form gels that exhibited rheological properties similar to those of fat [

9,

11].

2.2. Sample Preparation

Madeleines were prepared according to the formulation recommended by the Human Resources Development Service of Korea (HRDK) for craftsman confectionary making. Cristina M. Rosell (2022) recommended replacing 35-65% of fat with fat replacers in baked products [

12]. Based on this recommendation, preliminary experiments were conducted, and a 50% replacement level was identified to be optimal for maintaining the structure of madeleines. The proportions of MD, WPI, and MCT were determined using a mixture design, specifically a second-degree simplex lattice design, with a total fat replacer content of 25g (

Table 1).

Flour and baking powder were sifted, and butter was melted using a double boiler. Eggs were beaten using a whisk and mixed with sugar and salt to prevent clumping. After thorough mixing, the sifted flour was added, followed by lemon juice, melted butter, and fat replacers. The dough was placed into madeleine molds in 20g portions, then baked at 180°C for 15 minutes in a preheated oven (Gas Oven Range, SK magic, Korea). After baking, the madeleines were cooled at room temperature for 1 hour before being used in experiments. This process was repeated three times for each sample.

2.3. Physicochemical Properties

2.3.1. pH

The pH of the samples was measured in triplicate using a pH meter (Orion Star™ A211 pH Benchtop Meter, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). A 5 g portion of the sample, ground using a blender (HR2041, Philips, Netherlands), was mixed with 45 mL of distilled water. The mixture was then agitated for 5 minutes at 140 rpm using a stirrer (KA-11-98, Korea Ace, Korea). After shaking, the sample was filtered through a paper filter (VCF-01-100W, Hario, Japan), and the filtrate was collected for pH measurement.

2.3.2. Crust Color

The crust color of the samples was measured for lightness (L), redness (a), and yellowness (b) in triplicate using a Spectrophotometer (YS3060 Grating, Shenzhen 3nh Technology, China). The standard white plate values for L, a, and b were 97.21, 0.01, and 0.27, respectively.

2.3.3. Moisture Content

The moisture content of samples was measured in triplicate according to American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC) Method 44-15A using a dry oven (J-300M, Jisco, Korea).

2.3.4. Texture Profile Analysis

The texture profile analysis (TPA) of the samples was conducted using a texture analyzer (TA.XTExpressC, Stable Micro Systems, England). Hardness, cohesiveness, springiness, and chewiness were determined from the force-time curves obtained from two-bite compressions. The samples were cut into 2 x 2 x 2 cm pieces for analysis, and the analysis conditions were as follows: Pre-test speed: 3.0 mm/s, Test speed: 1.0 mm/s, Post-test speed: 1.0 mm/s, Strain: 30.0%, Time: 3.0 s, Trigger Force: 4.0 g. TPA measurements were repeated five times, and the values were analyzed after excluding the minimum and maximum hardness values.

2.4. Consumer Accpetnace Test

2.4.1. Subjects

A total of 55 consumers participated in this study, consisting of 6 males (10.9%) and 49 females (89.1%), with an average age of 21.0 ± 2.4 years. Subjects were recruited through an advertisement posted on an online platform. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of CUK-IRB (1040395-202309-16) on September 15, 2023. All subjects voluntarily agreed to take part in the study and provided informed consent before participation.

2.4.2. Sample Preparation and Presentation

The samples were cut in half along their longer side and presented in disposable dishes (100 mm, Cleanlab, Korea) labeled with a random three-digit number. The order of sample presentation was arranged using a William Latin-square design to minimize contrast effects [

13]. A sequential monadic order was used for sample evaluation [

14], and water (ICIS 8.0, Lotte Chilsung Beverage, Korea) was provided between samples to prevent carry-over effects.

2.4.3. Test Procedure

The subjects evaluated overall, appearance, odor, taste/flavor, and texture liking using a 9-point hedonic scale (1 = extremely dislike, 5 = neither like nor dislike, 9 = extremely like) after tasting the samples [

15]. They also freely described the drivers of liking and disliking of each sample through open-ended questions [

16]. Following the sensory evaluation, subjects completed a questionnaire on their baked product consumption habits (frequency, consumption context, and concerns) and their perceptions of fat replacers, including their awareness, interest, and willingness to consume them. The consumer test was conducted in individual booths and took approximately 30 minutes to complete.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to examine differences in pH, crust color (L, a, and b), moisture content, TPA parameters, and liking score among the samples. When a significant effect was observed at the 5% significance level, Duncan’s multiple range test was conducted as a post-hoc analysis to compare the mean values between samples.

The open-ended questions were analyzed qualitatively. Similar terms mentioned as drivers of (dis) liking were categorized into representative terms. Textural analysis was performed to identify drivers of (dis) liking that were mentioned with a frequency of 10% or higher, or those that had significantly higher observed values than expected values based on the chi-square per cell test. Additionally, correspondence analysis (CA) was conducted to visually summarize the relationship between the samples and the drivers of (dis) liking.

Multiple factors analysis (MFA) was used to analyze the relationship between the physicochemical properties, liking scores, and drivers of (dis) liking, with fat replacer content treated as a supplementary variable. To further classify the samples based on the MFA results, hierarchical clustering on principle component analysis (HCPC) was applied.

All data analyses were conducted using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corp., NY, USA) and FactoMineR [

17] in R-Studio.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Properties

The results of pH, crust color, and moisture content of the samples are shown in

Table 2. The pH values of the MD, MPI, and MD+MPI samples were lower than those of the CON sample, while the pH values of the MCT and MCT-contianing samples (MD+MCT, WPI+MCT) were significantly higher.

For crust color, significant differences were observed in the L and a values between the samples, but no significant differences were found for the b value. The browning of baked products, which results from the Maillard reaction and caramelization, is mainly reflected in the L value [

11,

18]. The L value was lower in the MD-containing samples, likely because the reducing sugars in maltodextirn participate in the Maillard reaction with amino compounds, darkening the color [

19]. In contrast, the L values were higher in the WPI, MCT, and WPI+MCT samples. WPI, which is white, and MCT, which is colorless, replaced the carotenoid-based pigments found in butter, resulting in a relatively ligher color in these samples [

20]. This finding aligns with Chung [

21]’s study, which showed that increasing the proportion of whey protein concentrate in muffins significantly lightened their color.

Moisture content was higher in the MD-containing samples (31.7-38.5%), with moisture content tending to increase as the proportion of MD added increased. MD acts as a hygroscopic agent [

22], and this finding is consistent with Colla and Gamlath [

23]’s research, which showed that moisture content increased significantly with higher levels of MD in baked savory legume snacks. On the other hand, the WPI, MCT, and WPI+MCT samples had lower moisture content (26.0-29.6%). The strong water-holding capacity of WPI contributes to the firming of air cells during heating, but it reduces its ability to retain moisutre, leading to a decrease in moisture content with higher WPI levels [

6]. Additionally, in the MCT-containing samples, larger pore sizes seem to have resulted in decreased moisture content. Fat reduces the permeability of cell walls to gases, leading to greater expantion, and consequently, the formation of larger holes and a more porous structure [

24,

25].

The TPA results of the samples are presented in

Table 3. Significant differences were observed in hardness, cohesiveness, and chewiness between the samples, except for springiness. The MD sample showed the lowest hardness value, likely due to its higher moisture content, which reduced its hardness [

5]. In contrast, the WPI samples exhibited a higher hardness level, which aligns with the findings of Kim [

6], where an increase in WPI content led to a significant increase in the hardness of cakes. Chewiness, closely related to hardness, showed a similar trend to hardness [

26]. All samples with fat replacers had significantly higher cohesiveness than the CON sample, due to the reduction in total fat content. Gluten in flour helps with moisture absorption, cohesiveness, viscosity, and elasticity in dough [

27], while fat disrupts the continuity of protein and starch structures, preventing gluten formation and acting as a shortening agent [

25].

3.2. Consumer Acceptance Test

3.2.1. Consumer Acceptance and Drivers of (dis) Liking

The samples had a significant effect on overall, taste/flavor, and texture liking, while no significant differences were observed for appearance and odor liking (

Table 4). The MD+WPI+MCT sample received the highest liking scores, followed by MD+MCT and CON, which showed similar levels of liking. In contrast, the MD and WPI samples had the lowest overall liking scores. Overall, samples with a single fat replacer had lower liking scores compared to those with two or more components. However, the MCT sample showed no significant differences from the CON sample, suggesting that MCT contribute to maintaining consumer acceptance. A similar trend was observed for taste/flavor and texture liking. Although appearance liking did not differ significantly among samples, WPI-containing samples tended to receive lower scores, likely due to their lower L values, which indicate a darker color.

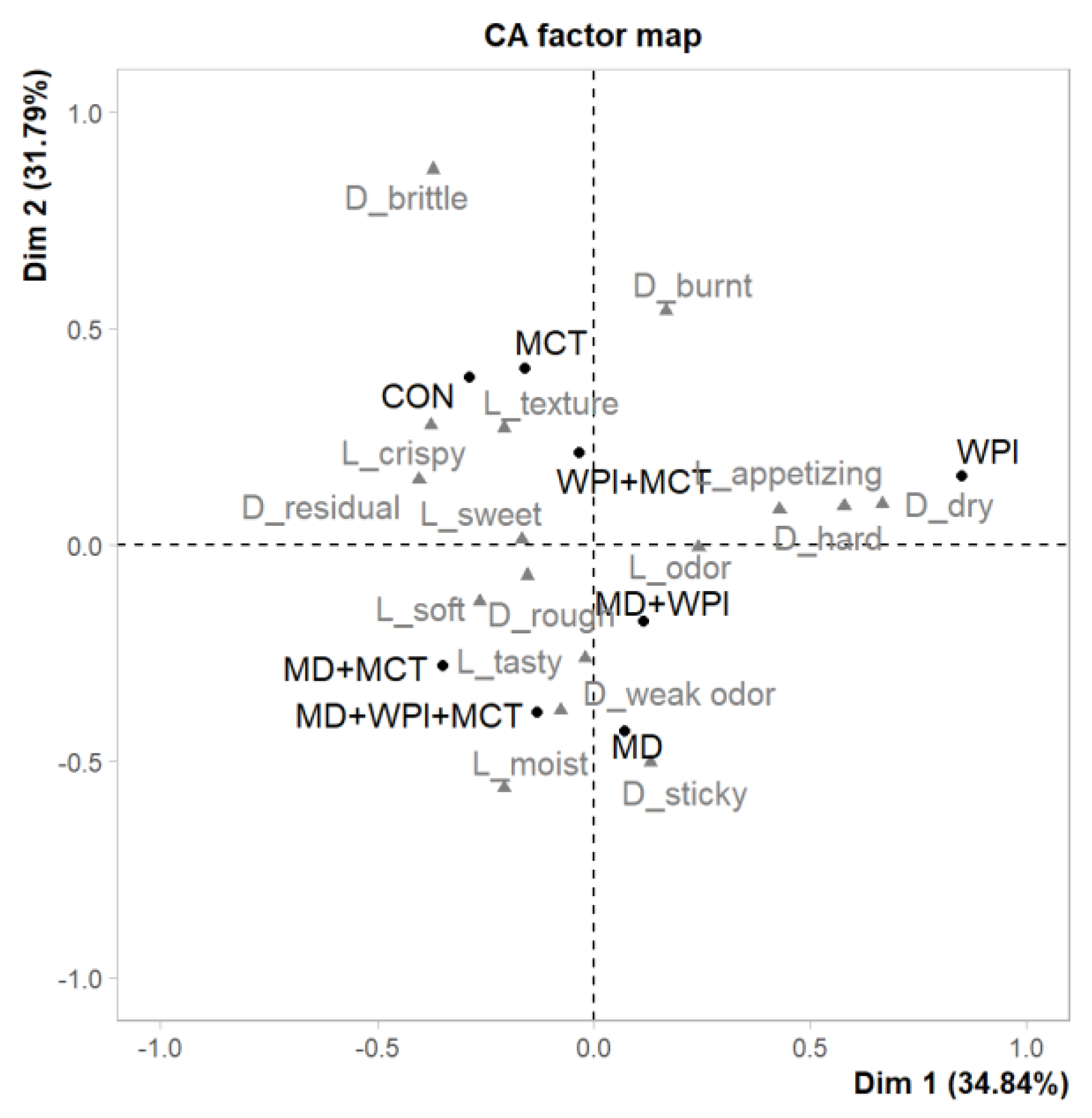

The CA results for the drivers of (dis) liking in the samples (

Figure 1) showed that Dim 1 and Dim 2 accounted for 34.84% and 31.79% of the variance, respectively, explaining 66.63% of the total variance. The WPI samples were positioned in the (+) of Dim 1, where L_appetizing, closely linked to high ratings for appearance liking, was frequently mentioned as a major driver of liking. However, D_dry and D_hard were identified as drivers of disliking, which explained the lower texture liking scores. This finding is consistent with Kim [

6]’s study, which reported that increasing the amount of WPI in butter sponge cakes led to a drier and firmer texture. In contrast, the CON sample and the samples containing MCT were located in the (-) of Dim 1, with L_crispy and L_soft commonly cited as drivers of liking. However, the CON and MCT samples in the (+) of Dim 2 were distinguished by D_brittle and D_burnt. Samples containing MD were positioned in the (-) of Dim 2, with L_moist being identified as a driver of liking. However, for the MD samples, D_sticky was specifically mentioned as a driver of disliking.

3.2.2. Consumer Perception of Fat Replacers

The analysis of baked product consumption frequently revealed that more than half of the consumers (58.3%) reported consuming them two to three times per week, followed by two to three times per month (34.5%). These results suggest that baked products are deeply integrated into consumers’ daily dietary patterns. Moreover, the majority of consumers tend to consume baked products as snacks (74.5%) rather than meal replacement (23.6%). Regarding concerns related to baked product consumption, caloric content (38.2%) was the most frequently mentioned issue. This indicates a widespread perception that baked products are generally high in calories. Additionally, 12.7% of consumers were concerned about nutritional facts (e.g., sugar and fat content). Overall, consumers exhibited a significant interest in the caloric and nutritional aspects of baked products, which may be further amplified due to their predominant consumption as snacks.

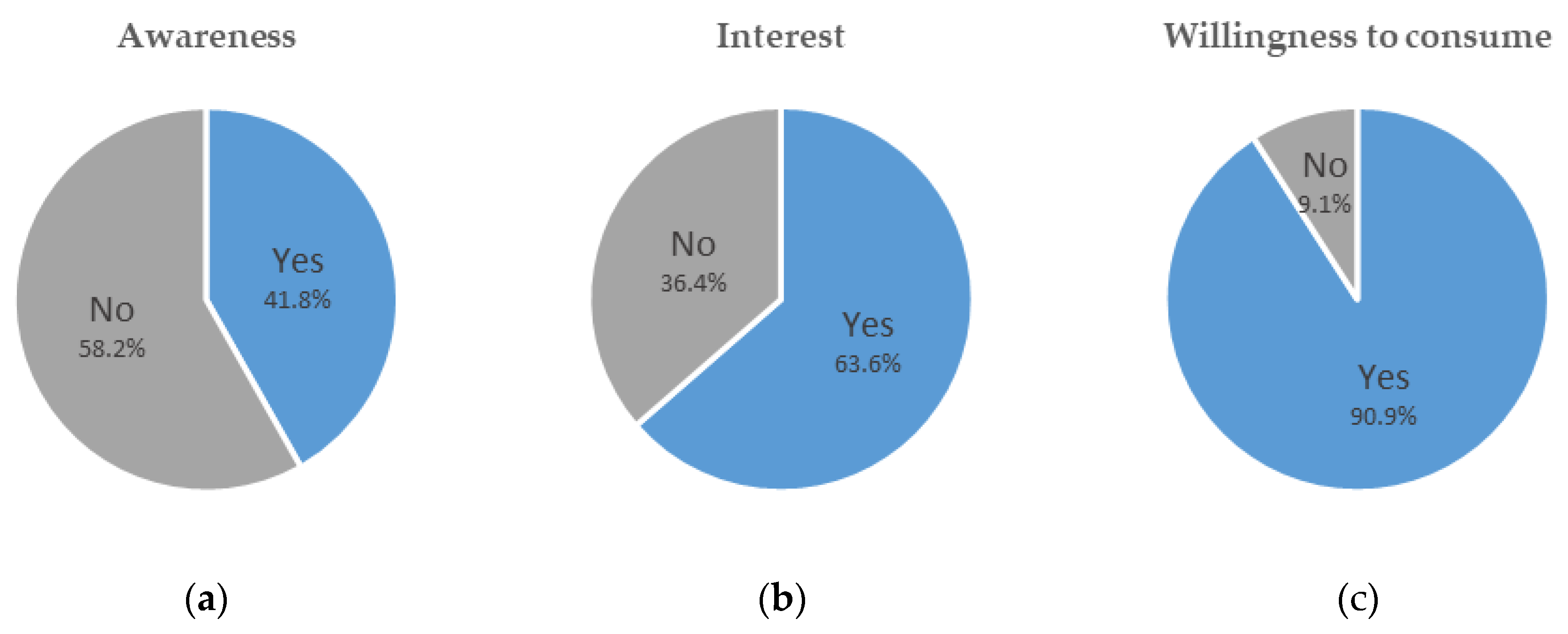

The results of consumer awareness, interest, and willingness to consume products containing fat replecer showed that awareness was relatively low at 41.8%, but interest increased to 63.3%. Notably, 90.9% of consumers expreesed a willingness to consume products containing fat replecer, suggesting strong potential for consumer acceptance.

Figure 2.

Consumer (a) awareness, (b) interest, and (3) willingness to consume products containing fat replacer.

Figure 2.

Consumer (a) awareness, (b) interest, and (3) willingness to consume products containing fat replacer.

The consumer perception of fat replacers was predominantly positive (

Table 6). The main reasons for the positive perception were their low calorie (71.4%) and low fat (21.4%) content, with weight loss and obesity prevention (16.7%) and health benefits (19.0%) also being important factors. Neutral perceptions were mainly due to a lack of urgency (33.3%). Negative perceptions were primarily related to concern about the lack of safety information.

3.3. Correlation Between Physicochemical Properties and Consumer Acceptance

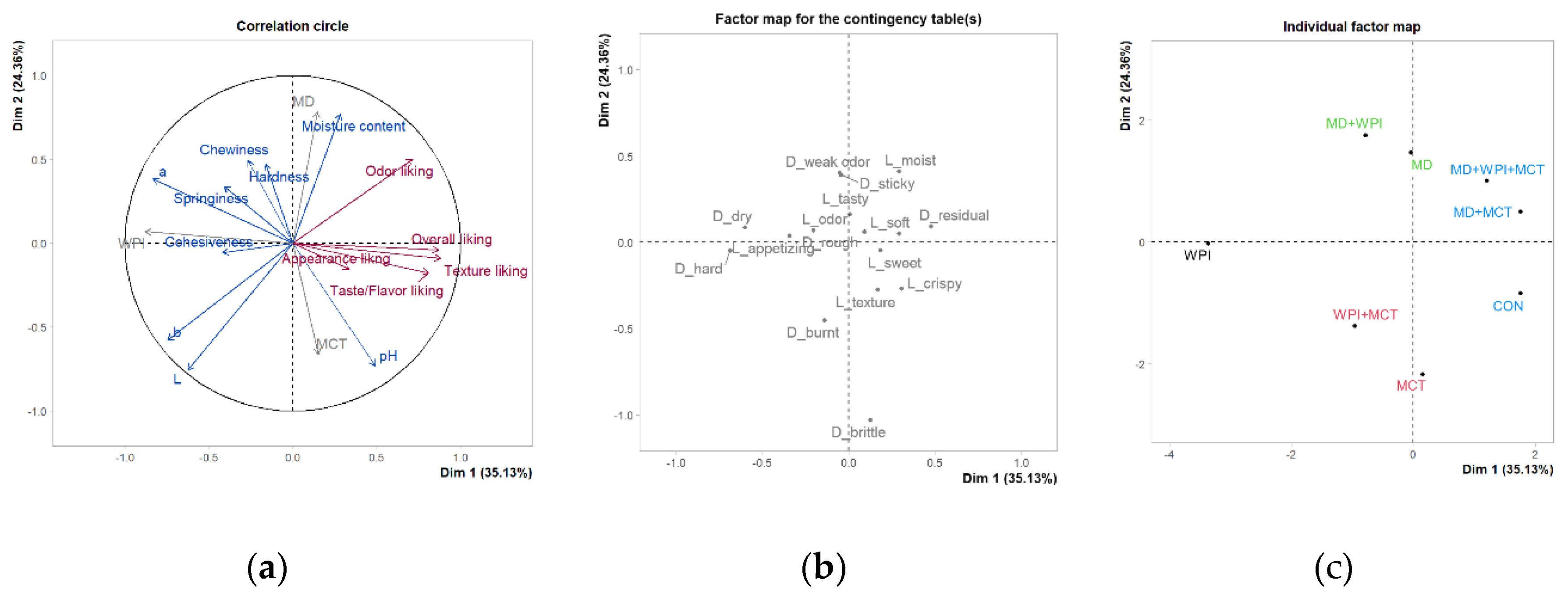

MFA was performed to analyze the correlation between physicochemical properties and consumer acceptance (

Figure 3). Dim 1 and Dim 2 explained 35.13% and 24.36% of the variance, respectively, accounting for a total of 59.49% of the variance. Additionally, HCPC analysis classified the samples into four clusters (

Figure 3-(b)): Cluster 1 (CON, MD+MCT, MD+WPI+MCT), Cluster 2 (WPI), Cluster 3 (MD, MD+WPI), and Cluster 4 (MCT, WPI+MCT).

In the (+) of Dim 1, Cluster 1 (CON, MD+MCT, MD+WPI+MCT) was positioned, and these samples showed generally low TPA parameter values. Consequently, L_crispy, L_soft, and L_moist were identified as key drivers of liking, and these samples received high liking ratings from consumers. In contrast, the WPI sample, which demonstrated opposite characteristics, was located in the (-) of Dim 1. This sample exhibited high TPA parameter values, leading consumers to frequently mention D_hard and D_dry as drivers of disliking, resulting in lower liking ratings.

In the (+) of Dim 2, Cluster 3 (MD, MD+WPI) was positioned, and the MD-containing samples were characterized by high moisture content. As a result, moisture-related sensory attributes such as L_moist and D_sticky were frequently mentioned as drivers of (dis) liking. Conversely, Cluster 4 (MCT, WPI+MCT), which contained MCT samples, was positioned in the (-) of Dim 2. These samples with relatively lower moisture content, thus, D_brittle was identified as the main driver of disliking.

4. Conclusions

This study analyzed the physicochemical properties, consumer acceptance, and drivers of (dis) liking of madeleine using fat replacers, as well as consumer perceptions of fat replacers. The results showed that the binary and ternary blend samples did not exhibit the distinct physicochemical characteristics seen in the single component samples. This is interpreted as the result of the interaction between the fat replacers, which neutralized their individual effects. The MD sample showed that the high moisture content was the primary drivers of disliking (D_sticky), while the WPI sample was associated with D_hard, D_dry as drivers of disliking, and the MCT sample was associated with D_brittle. However, these negative characteristics were alleviated by the blending of the fat replacers, and in the MD+MCT and MD+WPI+MCT samples, drivers of liking such as L_crispy, L_soft, and L_moist emerged. Moreover, HCPC results revealed that these samples were clustered with the CON sample, showing similar characteristics. These results suggest that when multiple components are present, balanced characteristics emerge rather than the distinct traits of individual components, which positively impacted consumer acceptance and contributed to higher liking.

Additionally, consumers typically consume baked products as snacks, and the main concern highlighted was the calorie content. This indicates a tendency among consumers to avoid high-calorie foods, which, in turn, heightened interest in fat replacers. In fact, many consumers were not well-versed in fat replacers, a significant portion (63.3%) expressed interest, and 90.9% of consumers showed a willingness to consume. Particularly, the low calorie and fat content of fat replacers had a positive impact on consumer perception. These findings suggest that fat replacers have considerable market potential.

However, it should be noted that the consumers who participated in this study were relatively young, so the results cannot be generalized to represent all consumers. Additionally, since the fat replacers were used to substitute only 50% of the fat content, this limitation may affect the results. Nevertheless, the combination of fat replacers was found to be more favorable in terms of consumer acceptance than single ingredients. It is expected that future research focused on identifying the optimal combination of within a triple mixture could lead to even better results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SY.L., S.Y.L., DY.H., JY.J. and M-R.K.; methodology, SY.L., S.Y.L., and M-R.K.; validation, SY.L., S.Y.L., and M-R.K.; formal analysis, SY.L. and S.Y.L.; investigation, SY.L., S.Y.L., DY.H. and JY.J.; data curation, M-R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, SY.L., S.Y.L. and DY.H.; writing—review and editing, M-R.K.; visualization, S.Y.L.; supervision, M-R.K.; project administration, M-R.K.; funding acquisition, M-R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Research Fund, 2022 of The Catholic University of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00458728).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MD |

Maltodextrin |

| WPI |

Whey protein isolate |

| MCT |

Medium-chain triglycerides |

| TPA |

Texture profile analysis |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| CA |

Correspondence analysis |

| MFA |

Multiple factor analysis |

| HCPC |

Hierarchical clustering on principle component analysis |

References

- Kopelman, P.G. Obesity as a medical problem. Nature 2000, 404, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, Y.; Chen, S.; Xu, L.; Wu, N.; Tu, Y. Recent trends in design of healthier fat replacers: Type, replacement mechanism, sensory evaluation method and consumer acceptance. Food Chemistry 2024, 138982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonnalagadda, S.S.; Jones, J.M.; Black, J.D. Position of the American Dietetic Association: fat replacers. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2005, 105, 266–275. [Google Scholar]

- Colla, K.; Costanzo, A.; Gamlath, S. Fat replacers in baked food products. Foods 2018, 7, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshminarayan, S.M.; Rathinam, V.; KrishnaRau, L. Effect of maltodextrin and emulsifiers on the viscosity of cake batter and on the quality of cakes. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2006, 86, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-H. Quality characteristics of low-fat butter sponge cakes prepared with whey protein isolate. Korean Journal of Food science and Technology 2010, 42, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Ramírez, M.; Calderón-Domínguez, G.; García-Garibay, M.; Jiménez-Guzmán, J.; Villanueva-Carvajal, A.; de la Paz Salgado-Cruz, M.; Arizmendi-Cotero, D.; Del Moral-Ramírez, E. Effect of whey protein isolate addition on physical, structural and sensory properties of sponge cake. Food Hydrocolloids 2016, 61, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmall, T.L.; BREWER, M.S. Medium chain triglyceride effects on sensory and physical characteristics of shortened cakes. Journal of food quality 1996, 19, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoulias, E.; Oreopoulou, V.; Tzia, C. Textural properties of low-fat cookies containing carbohydrate-or protein-based fat replacers. Journal of Food Engineering 2002, 55, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.; Ketelsen, S.; Antenucci, R. Formulating oatmeal cookies with calorie-sparing ingredients. Food technology (Chicago) 1994, 48, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Psimouli, V.; Oreopoulou, V. The effect of fat replacers on batter and cake properties. Journal of Food Science 2013, 78, C1495–C1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazar, G.; Rosell, C.M. Fat replacers in baked products: Their impact on rheological properties and final product quality. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2023, 63, 7653–7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, E.J. Experimental designs balanced for the estimation of residual effects of treatments. Australian Journal of Chemistry 1949, 2, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFie, H.J.; Bratchell, N.; Greenhoff, K.; Vallis, L.V. Designs to balance the effect of order of presentation and first-order carry-over effects in hall tests. Journal of sensory studies 1989, 4, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lee, J. Korean consumers’ acceptability of commercial food products and usage of the 9-point hedonic scale. Journal of Sensory Studies 2018, 33, e12467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symoneaux, R.; Galmarini, M.V.; Mehinagic, E. Comment analysis of consumer’s likes and dislikes as an alternative tool to preference mapping. A case study on apples. Food Quality and Preference 2012, 24, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. Journal of statistical software 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purlis, E. Browning development in bakery products–A review. Journal of Food Engineering 2010, 99, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Yoon, H.H. Quality characteristics of rice muffin added with nondigestible maltodextrin. Korean Journal of Food and Cookery Science 2021, 37, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, M. Foods: experimental perspectives; 1989.

- Chung, H.-J. Quality characteristics of low-fat muffins containing whey protein concentrate. Journal of Korean Society of Food Science 2006, 22, 890–897. [Google Scholar]

- Conforti, F.D.; Archilla, L. Evaluation of a maltodextrin gel as a partial replacement for fat in a high-ratio white-layer cake. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2001, 25, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, K.; Gamlath, S. Inulin and maltodextrin can replace fat in baked savoury legume snacks. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2015, 50, 2297–2305. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Luna, K.; Astiasarán, I.; Ansorena, D. Gels as fat replacers in bakery products: A review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2022, 62, 3768–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, D.G.; Fisher, N. Release of carbon dioxide from dough during baking. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 1976, 27, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesniak, A.S. Classification of textural characteristics a. Journal of food science 1963, 28, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, A.; Khatkar, B. Effects of fatty acids composition and microstructure properties of fats and oils on textural properties of dough and cookie quality. Journal of food science and technology 2018, 55, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).