1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

While technological advances have enhanced productivity and convenience, they have caused persistent environmental issues. Carbon emissions, deteriorating sewage and sanitation, and air pollution are threatening public health and inflicting physical and psychological disorders on modern society. In response, consistent efforts have been made to devise solutions that protect health. Formerly, clinical treatments, including surgery and medication, and the biomedical model were predominantly used to maintain good health [

1]. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined health as a state of physical, mental, and social wellbeing, beyond the mere absence of illness. In this context, it is important to explore the social aspects of health [

2]. Along with biological factors, a sense of consistent happiness and greater quality of life plays a pivotal role in health. A related concept is “therapeutic landscape,” which suggests a connection between place and health. Therapeutic landscape refers to the combination of physical environment, social conditions, and human perceptions of producing healing effects [

3]. Interactions between human activities and physical environments constitute the identity of a place and the positive feelings derived therefrom give rise to mental and physical healing [

4]. In therapeutic places, specialized actions are taken, social relationships are built, and empathy is generated. Gardens, forests, woods, parks, and other green spaces are among the representative elements of therapeutic landscapes and several studies have claimed that these have an influence on health and wellbeing [

5,

6,

7,

8]. A therapeutic landscape has both positive and negative characteristics depending on its location and utilization [

9]. Sometimes a space with a positive impact can be scary or uncomfortable under certain circumstances and conditions [

10]. This is because the temporal, social, and cultural contexts of the relationship between people and nature are different.

How people relate to nature is categorized as “viewing,” “being in,” and “active participation” [

11]. Through active participation in nature, a close relationship can be formed with a higher possibility of positive effects. With emotional empathy between the two entities, resilience emerges, which helps to flexibly respond and adapt to inevitable situations. Thus, the therapeutic effects of a place are enhanced when there is an understanding of the contexts between the two entities and the interrelationship deepens, compared to simply viewing or being close to nature [

12]. In other words, actively participating in nature, beyond merely viewing natural objects, instills nature with a singular value and meaning [

13]. In this regard, this study explored the significance of a relationship-centered approach to nature. Specifically, it explored gardens from the categories of therapeutic landscapes as they exist in proximity to daily life and represent an accessible location for participatory activities. Gardens provide spaces for static activities, including observing nature, resting, and leisure, and gardening is a dynamic activity comprising leveling soil, sowing seeds, and growing flowers and plants [

14]. Gardens can be regarded as private places where people engage in individual activities and as public places where multiple people gather. Gardens encourage the revitalization of spaces and provide durable and dynamic experiences by linking social, emotional, and symbolic elements [

12]. This study attempted to understand the impact of creating and managing a garden on people.

The study selected youth with intellectual disabilities (YwID), a population highly likely to be socially excluded, as the study subjects, and examined the possibility of their changing and growing through the mediating role of gardens. YwID are at higher risk of being excluded from community participation than other groups [

15,

16]. As gardening is a social prescription that can develop individuals’ potential and provide new opportunities [

17], it may encourage YwID to participate in a local community and enhance their abilities to engage in various activities. Garden-based learning activities for YwID could play an important role in their health and welfare and the broader context of their social and existential recovery [

18]. The findings provide critical data for identifying the efficacy and potential for sustainable growth through garden-based learning for YwID and validating the impact of gardens as a therapeutic landscape.

1.2. Current Research

In therapeutic landscapes, natural spaces play an important role. Originally, the therapeutic landscape concept considered places supporting physical and mental health, including pilgrimage destinations and spas [

3,

19]. Thereafter, the scope of therapeutic landscapes expanded to hospitals [

20], walkways [

21], homes [

22], zoos [

23], beaches [

24], and deserts [

25]. Recently, natural elements, such as mountains, rivers, and oceans, have been recognized as important therapeutic landscapes [

10]. Ulrich [

26] claimed that when people have a close relationship with nature, they feel emotional stability and pleasure, and their concentration improves. Studies have confirmed that, in a therapeutic sense, natural spaces have different values and meanings than hospitals and homes. Stress decreases and positive emotions develop when people interact with nature and view plants, water, or gardens [

27]. Natural spaces serve a special therapeutic role in facilitating a healthy life and forming relationships [

5,

10]. Thus, natural environments are prime examples of therapeutic spaces that help the treatment, recovery, and rehabilitation of patients in poor health [

28].

Moreover, therapeutic landscapes have gone beyond the natural to become embedded in the everyday lives of contemporary people. With the increasing need for multidimensional medical services, hospitals and places where people reside could be therapeutic places [

22]. In particular, private gardens, as ordinary places, become happy gathering places, redolent of friendships and support [

29]. Gardens are places of comfort wherein diverse activities are performed and mental, physical, and spiritual healing is supported [

30]. The therapeutic garden has helped individuals feel a decreased sense of loss, greater creativity, improved self-expression, and greater engagement in social interactions, and opportunities for sensory stimulation, improved self-esteem, and space for physical exercise [

31]. The therapeutic garden is an effective way of improving the health and wellbeing of people of all ages [

32].

Various studies on the therapeutic role of gardens for people with mental health issues have included older adults, youth, college students, office workers, and veterans [

33,

34]. However, no studies have specifically focused on YwID. Thus, this study primarily examined future educational implications of the use of gardening characteristics with youth and explored the potential of gardening in improving the functioning of YwID by helping them adapt to the social environment and integrate into society. Accordingly, it was necessary to understand the influences of gardens on youth. Green spaces enhance concentration and reduce stress in youth [

35]. Moreover, they are reported to help reduce attention deficit, hyperactivity, and depression [

36]. These findings indicate that gardens, through the familiar mediators of flowers and plants, can contribute substantially to improving mental stability and physical health in youth. The participants of the present study have unique characteristics as they are YwID. Hence, the study could not analyze the effects of gardens by using common assessment tools. Therefore, it employed the garden-based learning method – a practical educational approach – to examine the influences of gardens on YwID. Based on previous findings that garden-based learning causes positive results in the academic performance and personal behaviors of students who had lost interest in learning [

37,

38], the study concluded that this approach is appropriate for its goals.

Yang et al. [

39] analyzed the healing effects of gardens on socially disadvantaged people with developmental disabilities, dementia, schizophrenia, and depression, which are problems in the Korean society. This study focuses on an aspect of research on government policy concerning the garden-based healing program operated by the Korea Forest Service in collaboration with specialized institutions. The findings show that gardening activities contribute to substantial improvements in mental health variables concerning depression, anxiety, daily activities, quality of life, and mindfulness. This study examined the types of educational activities conducted with different types of socially disadvantaged groups and the treatment effects observed in these groups. However, this study did not specifically confirm the effects on the participants based on their characteristics and suggested the general conclusion that gardening positively influences the health and wellbeing of socially vulnerable people. The present study aims to address the limitations of previous studies by analyzing the phenomenon in more depth and deriving therapeutic effects.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collection

People with intellectual disabilities face several limitations and difficulties in their everyday lives [

40,

41]. As they have difficulties in collecting or selecting information independently, they cannot voluntarily participate in physical activities [

42] and their short attention span makes them acquire smaller volumes of knowledge at a slower pace than others [

43]. They experience difficulty in forming and maintaining relationships as they do not fully understand the social behaviors of others [

44]. In this study, participants were required to actively participate in the garden-based program and convey their experiences and the effects of the program independently. Accordingly, the study recruited participants who did not face difficulties in basic communication and desired to lead a self-directed life by utilizing the knowledge acquired in the learning program. The students of Holt Special School, located in Goyang City, Gyeonggi-do, met these requirements. Founded in 1962, the school has operated various vocational programs for developing the potential of students to encourage independent living and enhance social adaptability. In particular, the center is mainly used by cleaners with mild intellectual disabilities, aged 18–24 years. They are suitable candidates for this study because of their high willingness to participate in social activities and gain basic communication skills, making it possible to assess the program’s effects. A total of 26 students, including 13 men and 13 women, participated in this study. Their average age was 20.5 years. The study was conducted from July 13–October 26, 2022. As the participants needed to express their thoughts and feelings, the recommendation of the teachers who were teaching students with severe disabilities was sought and prior consent of the students’ guardians was obtained for their participation. The study was conducted by two gardening instructors, two garden designers, and a psychologist, and the experts participated in every session of the educational program for efficient research. Before the garden-based learning program, and the validation and assessment of the research, the overview of the study and the methods of gardening were fully explained to all the participants, and data were collected only from those who consented to participate. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (blinded for review).

People with mental disabilities struggle to maintain attention for long periods and have difficulties in conveying personal ideas and exchanging opinions. Considering this, interview transcription and participant observation methods were employed for systematic data collection. The researchers filled in behavior observation charts at every session of the program, recording and assessing the level of participation, attitude, and interest of the participants using a systematically structured scale. In addition, individual interviews were conducted to gain an objective understanding of the effect of the program from the participants’ perspective. This participatory action research (PAR) method involved expert assessors observing participants and making a professional assessment. By applying PAR, researchers can examine the social, psychological, and educational changes in people with disabilities, and analyze outcomes, such as social adaptability and mental stability, from diverse perspectives. The advantage of this approach is that researchers and participants can build a relationship, which provides the basis for freely exchanging ideas and opinions [

29], and researchers can understand the behavioral patterns and characteristics of participants by closely observing their actions and desires [

45]. Thus, the researchers can participate in the program activities, thereby, understanding situations in the field and identifying the effects of the program. In this study, to examine personal experiences before and after participation, the participants were guided to naturally express their thoughts. The researchers thoroughly understood the characteristics of intellectual disabilities to narrow the gap between the two social groups of researchers and participants and formed a friendly relationship with the participants. The researchers wrote notes while working in the field as part of the research procedure [

29]. Interviews were held conversationally to explore personal experiences of participating in the garden-based healing program and changes in the participants’ perceptions. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed, supplemented with working notes, and the findings from the field observations were documented through selective thematic coding. The behaviors and responses of the participants to certain situations in the program were closely observed and the process by which the participants showed changes in behavioral patterns was examined. Through observation and analysis, specific determinants of changes and their meanings and perspectives were obtained.

2.2. Implementing a Garden-Based Learning Program

Regarding the participants, it is not appropriate to apply common educational methods as YwID have poorer capacity for adaptive behaviors and shorter attention spans than youth without intellectual disabilities. Therefore, the study adopted an approach that attracted the attention of the participants and gave them a sense of positive self-efficacy after participation. According to Burt et al. [

46], field training develops students’ ability to apply knowledge to real situations and piques their interest. In particular, a nature-based outdoor program is a special approach to support students’ social, emotional, and intellectual improvements, including academic performance [

47]. Such an approach could enhance awareness of sustainable life and environmental value while facilitating the immersion of the young generation [

48].

To better understand the research subject, the functions and roles of gardens need to be defined. However, these definitions can vary depending on social, cultural, and political contexts [

49]. In the United Kingdom, gardens are regarded as a place for pleasure, leisure, and play, whereas in India, they are a place for learning, community, and peace [

50]. Gardens play various roles and carry complex meanings in society; hence, a specialized approach is required to accurately recognize the value and meaning of gardens. In this context, considering the unique characteristics of YwID, this study designed a program wherein participants would feel less burdened, and positive or negative assessments could be made without hesitation. Garden-based learning programs for youth improve social interactions and emotional wellbeing, provide opportunities for physical activities, and facilitate better behavioral responses [

51]. By participating in garden-based learning programs, youth transition from passive observers to active participants [

52]. Adolescence is a vulnerable developmental stage, characterized by emotional, social, and biological changes. In this stage, gardens function as a place of learning, provide inclusiveness-based learning opportunities, and instill a positive perception of pleasure, peace, ecology, sustainability, and nutrition. Garden-based learning could be a practical solution to address climate change and environmental issues through experiential learning with nature [

53].

Based on these findings, this study developed a customized garden-based healing program wherein participants could develop diverse capabilities by acquiring self-help skills, enhancing self-determination, and improving social relationships. To participate, basic reading skills, simple number competencies, and communication skills using limited language were required. Program development comprised prior preparation, program development, program implementation, and monitoring and assessment. Educational objectives were determined according to the characteristics of YwID who have insufficient adaptive abilities to integrate in society to help their social growth through garden-based learning. Programs were designed session-wise with respective goals and expected effects. As the participants found it difficult to sustain focus during theoretical lectures, programs were focused on experiential activities that would arouse interest and encourage active participation. The programs were operated flexibly, adjusting break time and class time according to the observed participant responses so that they could focus on the program. In addition, educational content was designed and placed to draw participants’ attention and engagement using elements of nature [

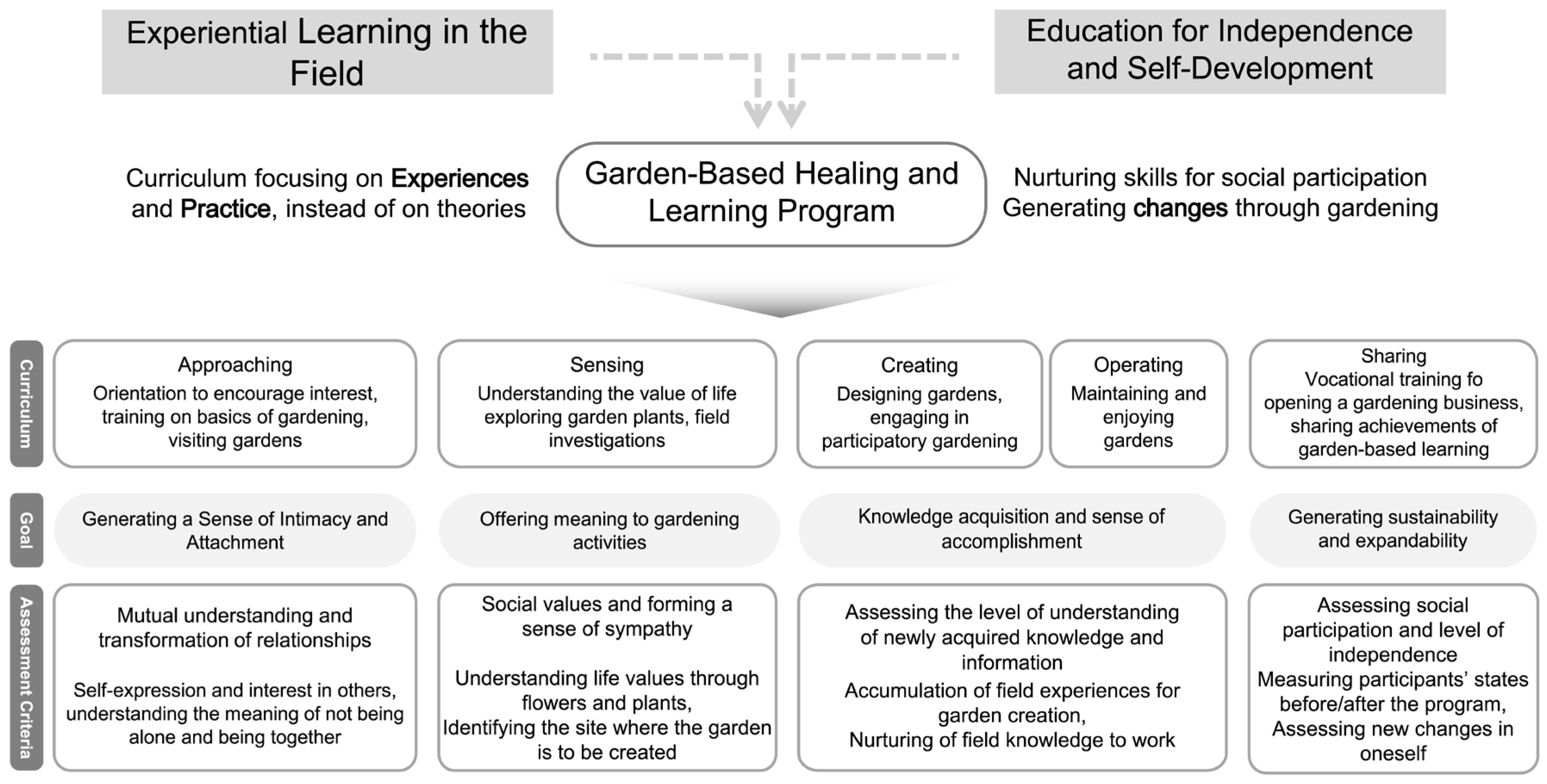

46] to enhance their concentration. Each session was designed to allow the participants to explore and observe plants, express their feelings in the process, and handle and interact with the plants while learning gardening-related knowledge. The study intended to build a foundation by teaching YwID to manage and maintain gardens, introducing them to diverse values and learning. Practical field training, rather than theories, was emphasized and the program was largely aimed at cultivating social skills as a long-term therapeutic effect. Specifically, it aimed to impart knowledge on applying sustainable gardening in daily life by using the school infrastructure. The curriculum included understanding gardening, creating a garden, managing a garden, and gardening activities, each of which comprised approaching, sensing, creating, operating, and sharing (

Figure 1). At each stage, participants were encouraged to achieve set goals, such as building intimacy and attachment, finding meaning, acquiring knowledge, and enhancing feelings of accomplishment, and deriving sustainability and expandability. Assessment criteria were set for each course to validate the effectiveness of the program. Over 3 months, 24 sessions were held and every program was observed for performance analysis against the set goals. To validate the program’s effectiveness, the study observed and assessed the participants’ outputs and their emotions and feelings at each stage.

3. Results

This study investigated the relationship between therapeutic landscapes and learning. Specifically, among numerous types of therapeutic landscapes, this study examined gardens as a place for learning and its effects on YwID’s self-growth and improved adaptability to environmental changes. The results show that through the garden-based learning program, YwID built social relationships, improved physical and mental wellbeing, and nurtured social skills. It confirmed that gardening activities motivated positive thinking, expanding the scope of interest and attention and reinforcing physical, mental, and social restorative capabilities. A characteristic of garden-based learning programs is that they allow for emotional therapy by inducing positive feelings, such as interest, joy, pleasure, and happiness, while participants are engaged in productive activities that involve handling plants and interacting with nature. In the process of learning and getting accustomed to the repetitive task of growing and caring for plants, participants enjoy the social therapeutic effects of gardening, such as acquiring professional knowledge, feeling a sense of professional accomplishment, and developing capabilities for vocational rehabilitation. Hence, the program helped in recovering psychological stability, building social relationships, and improving individual capabilities.

3.1. Emotional Healing for the Recovery of Psychological Stability

Being close to a garden provides an opportunity to share feelings with plants as they find links between the lifecycle of plants and their own. Thus, caring for plants has a positive influence on those who cannot live a self-directed life due to their lack of self-determination and provides a sense of responsibility and accomplishment.

Planting flowers and lugging soil around with my friends made me sweat a ton, but it felt really good. It’s funny how hard work can actually make you feel great. Watching the plants grow and thrive helped calm my anxiety. When I saw the garden changing, I could feel the mystery of life. I became confident and thought that I could also make it. I think the garden gave me happiness.

(Participant A)

The garden-based learning program focused on providing participants with the opportunity to create a healthy and safe space by and for themselves. Participants could create a space wherein they could escape from a daunting society and feel comfortable and safe without help from others. In this space, they enjoyed private time or interacted with friends, unknowingly experiencing the positive influences of the outside environment.

Throughout the program, the participants were so happy simply because they were in the garden; not in the class. They talked with friends and sometimes sang a song in the garden they made by themselves. We hold cultural events, such as aerobics and flea markets. It seems that now this place has become a playground and a shelter, especially for the youth.

(Instructor A)

3.2. Social Healing through Social Relationships

Garden-based learning can build social skills and self-esteem in people with interpersonal difficulties. Participants developed a sense of understanding and cooperation as they worked together to solve challenging tasks in the garden, which became a common interest. It had a positive effect on connecting “people to nature” and “people to people.” The garden sensitivity training course helped participants develop an appreciation for nature by engaging all five senses with garden materials. The garden trip allowed them to explore plants, learn from them, and create precious memories together.

I still chat with my friend who held my hand when we were learning to close our eyes and feel the texture of the plants. Planting flowers and pulling weeds is tough but I have great memories of doing it with my friends. We bonded through all the hard work and got close enough to share our problems.

(Participant B)

Through gardening, patience and concentration can be developed. In particular, people develop the ability to accept the emotions of others to maintain a collaborative relationship. Gardening encourages a positive way of thinking, be it a sense of stability, patience, or respect.

A participant did not take part in transporting seedlings so others yelled at them until they cried. However, after realizing that the participant was allergic to pollen, the others showed an act of caring by allowing a short break time. They also understood the situation of a participant with an injured arm and told them to rest and not feel sorry about it.

(Instructor B)

What initially felt awkward and uncomfortable, turned into something positive. Fond memories remain of the people met during the garden training, the friends made, and the guests invited to the finished garden. The positive effects of incorporating the garden into the program have grown. Participants who relied on assistance took ownership of the garden and created special memories. The garden became a medium for social interaction.

Towards the end, I started feeling sad. I hated saying goodbye to the teachers I met through the class. I remember all the fun times with my friends, creating the garden, having garden parties, and inviting guests. The memories we made during the garden class are really precious to me.

(Participant C)

3.3. Physical Healing through New Activities

As gardens were used as a place of learning, students who usually did not participate in physical activities were encouraged to come outdoors. Touching soil and planting flowers made it possible for students to be with nature, develop a sense of space, and contribute to joint movement and activation of muscles. Acts of digging and laying soil were helpful for gross motor skills, whereas planting flowers and seedlings and trimming roots, stalks, and leaves improved fine motor skills.

Compared to the theory lectures in class, it was a special experience to come out and dig soil, plant seeds, and sweat with friends. For the first time in my life, I used a garden trowel, planted flowers, and pulled out weeds, and I moved heavy packages, cut timber, and made wood fences. At that time, it was hard for me to do such things repetitively but I felt comfortable and rewarded when I saw flowers and plants growing.

(Participant D)

With flowers and plants functioning as mediators, gardening arouses people’s five senses while improving cognition. Furthermore, various cognitive activities performed in gardening stimulate the senses, improve immunity, and activate the circulation of blood and hormones, improving overall health. The results of this program show that gardening actively changes participants.

Sometimes I walk around the garden. I smell the plants and see how tall each plant has grown, calling their names. In particular, I wonder whether the flower I planted is growing well and it is marvelous to see them change as time goes by. I can occasionally see small bugs that I only see in books. When I’m out in the garden with my friends, hearing the birds chirping around me, it helps me clear my head more than listening to music.

(Participant E)

3.4. Independent Healing Based on the Ability to Be Different

Typically, YwID do not interact with youth their age and have difficulties maintaining interpersonal relationships. However, through gardening, they naturally learn and acquire sociability by sharing outputs with others, recognizing the value of their existence. This indicates that gardening is an effective tool to encourage the social participation of people with disabilities and improve their quality of life.

It was a marvelous experience, seeing the garden exactly as we had imagined in front of our eyes. Referring to the picture that we first drew, we planted flowers one by one and spread soil, and a beautiful garden was finally created. I feel so proud of the garden because we created it with friends. Specifically, I really want to show the flower that I planted by myself to my parents.

(Participant F)

Through the garden-based learning program, some participants identified their areas of interest and attention and expressed delight after completing the garden. When people design a garden according to their interests, they feel emotionally stable and achieve a sense of accomplishment.

The participants found their work rewarding as they watched the garden come together. They enjoyed activities, such as loosening the hard soil, cutting wood, moving supplies, digging, and planting flowers. Their growing interest in gardening made them aspire to become gardeners.

(Instructor C)

Garden-based education shows the potential to evolve into a new vocational rehabilitation. YwID who are interested in flowers and plants can explore new career paths as they discover various interests and capabilities. They desire to overcome their limitations by learning skills through repetitive training and accumulating experiences of success. This means that garden-based learning refines emotions in the process of caring for plants and promotes occupational self-achievement.

One-time programs give pleasure and joy for a short time but soon fade from memory. Consistent healing for youth with intellectual disabilities means helping them make a wise and appropriate decision based on sharp observation of the problems in the field and having pride in themselves while working in society. I would like to lead the students with an interest in gardening into becoming social gardeners.

(Instructor D)

4. Discussion

This study explored the effects of garden-based learning programs on the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of YwID. Participants directly observed plants growing, felt emotionally supported, and built positive relationships through collaborative activities. Moreover, while gardening, participants acquired the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to make responsible decisions and the ability to effectively apply them. The program confirmed the effects of gardening that were observed in previous studies, including stress reduction and blood pressure improvement through contact with the natural environment [

54], improvement in everyday mindset [

13], relief from social isolation [

17] and lower anxiety [

55], and immunologic effects against stress [

35]. The reasons for these effects were that the participants became aware of the importance of life while sowing seeds and growing plants, and found value in their existence. In the garden, they communed with living things, such as flowers, plants, and insects, and, in the process, felt happy. Furthermore, as the garden acted as a living lab, participants learned and accumulated hands-on knowledge. In other words, gardening provided new knowledge to those with difficulties living in society due to low intelligence and lack of comprehension. Participants engaged in self-directed activities and felt a sense of accomplishment. They learned and developed an altruistic attitude through the program. YwID usually have very low self-esteem and are helped and cared for by others. However, in the process of growing plants, they developed the confidence that they could care for others. This change in the mindset improved social, emotional, and cognitive effects. The garden-based learning program improved the psychological state of YwID and offered them the opportunity for vocational rehabilitation. Repetitive cultivating activities involved in growing and caring for plants enhanced specialized skills. The process of regulating emotions through gardening extended their self-efficacy. Thus, gardening had a direct impact on the promotion of health and social independence.

Garden-based participatory learning induces direct and active experiences. While in contact with nature, people have positive emotional experiences and activities focused on participants’ interests heighten their concentration to allow for the accumulation of new knowledge. Horticultural therapy is appropriate for YwID because, rather than being dependent on verbal instructions, it provides alternatives to interact with instructors and participate in collaborative, active, and self-directed activities with peers. This is enhanced when participants voluntarily join gardening activities and enjoy the tasks without anxiety or fear. In addition, considering the characteristic of YwID of being dependent on others’ thoughts and opinions, the experience of touching and handling real objects brings emotional stability, improved social adaptation, and physical motor skills. Gardening facilitates the promotion of physical and mental health and becomes an instrument for the rehabilitation of participants’ disability. In other words, gardens are a space for facilitating social relationships, promoting healthy growth and development, contributing to physical activities, achieving a positive mindset and mental happiness, raising cohesion in communities, and nurturing solidarity in neighborhoods.

Based on the findings, garden-based healing programs can be an alternative public health service for youth with disabilities. Traditionally, medical interventions, such as psychotropic drugs, have been used to supplement the capabilities in which people showed deficiencies. However, the social model that posits that people with disabilities can live as members of a community is gaining attention and importance [

56]. The social model is closely related to living in a family and with others in the local community, which is emphasized in disability welfare. Thus, sustainable care for the disabled includes them living as a member of the local community and society by their abilities. Particularly, employment is an important process for earning income and for an individual’s existence to be recognized and valued in society. In this context, garden-based learning programs have an exceptional meaning as a social model for healing for YwID.

The findings showed that the health-promoting effect of therapeutic landscapes is enhanced and reinforced when people directly participate in the activities. The wellbeing effects of green spaces, fields, and parks [

57] are maximized when people’s experiential activities are added. This can be explained by the attention restoration theory, which states that the surrounding environment affects a person’s life [

58]. Nevertheless, the natural environment has a positive restorative effect [

54]. Depending on environmental characteristics and human behavior, the positive and negative effects can vary [

59]. Differences in perception arise with variations in conditions, such as accessibility of the topography, climate conducive to long-term stay, relationship with others, and the amount of knowledge and information obtained from the place [

10]. A characteristic of gardening confirmed in this study is that of adding experiential activities to the natural environment. In other words, when active participation through education is achieved in a preexisting natural environment, the space gains greater value. Such phenomena arise when therapeutic landscapes and humans interact vibrantly to create a therapeutic experiential landscape. Therapeutic experiential landscapes can be seen as an extension of therapeutic landscapes and are characterized by maximizing therapeutic restorative potential when mediating activities (e.g., learning, enjoying, and playing) are performed in a preexisting natural landscape. This study was conducted in the specific space of gardens; however, there is a need for further research on the effects of experiential interventions on different types of therapeutic landscapes.

5. Conclusion

Global public health policies mainly focus on social and economic conditions to protect and promote individuals’ health [

60]. Thus, they do not simply depend on biomedical interventions, instead adopt new approaches. This study investigated the healing effect of gardening on YwID. As it is not easy for YwID to collect information, experience situations, and make decisions independently, this study needed to devise an approach that could help the participants properly utilize the garden’s resources. Consequently, it developed and operated a customized learning program for YwID and analyzed its impact. The findings show that the garden-based learning program transformed participants’ perceptions of disability and cultivated their ability to respond to challenges. Participants experienced sympathizing with others; maintaining positive relationships and obtaining knowledge, skills, and attitudes for behaving responsibly through gardening. Garden-based learning, utilizing flowers and plants, enhanced physical and mental health, improved functioning, helped YwID adapt to the environment, and integrated them into society. It was a form of vocational training by which people with disabilities could become employable by learning gardening skills, promoting their participation in society, and upgrading their quality of life.

The findings suggest that gardens, as a therapeutic landscape, are no longer spaces of symbolic significance and visual aspects. Instead, with educational interventions, they can become a consistent positive catalyst. Therapeutic landscapes are limited in the therapeutic effect they generate simply by existing; however, the efficacy of their therapeutic effect can be enhanced through relational events or experiences. The study observed that educational activities foster deeper relationships with nature and generate a specialized effect. This study utilized gardens as a therapeutic landscape and considered only YwID to test the research hypotheses on garden-based learning. However, as there are a variety of therapeutic landscapes, different types of activity-based interventions could be made depending on the characteristics of each type. Thus, future research should identify and explore expanding the benefits of therapeutic landscapes.

Author Contributions

Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, D.K.; Supervision, E.P.; Funding acquisition, H.Y.; Methodology, Y.B.; Project administration, H.J.; Formal analysis, H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by two projects of the [Korea National Arboretum: the 2022 Korea National Arboretum R&D] grant number [KNA1-3-2, 21-5] and the [“Gardening Program for the Socially Vulnerable” Project].

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental procedures and protocols of the study were approved by the Korea University Institutional Review Board (protocol no. KUIRB-2022-0218-03, 05/04/2022), and methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the study are not publicly available owing to the ethical standards required by the Institutional Review Board but are available with the consent of the participants on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This article was written as part of the project “Gardening Program for the Socially Vulnerable” supported by the Korea National Arboretum. We are grateful to everyone who has been part of this project, especially the Korea Forest Service Government.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Sheridan, C.L.; Radmacher, S.A. Health Psychology: Challenging the Biomedical Model; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1992.

- Breslow, L. A quantitative approach to the World Health Organization definition of health: physical, mental and social well-being. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1972, 1, 347–355. [CrossRef]

- Gesler, W.M. Therapeutic landscapes: medical issues in the light of the new cultural geography. Soc. Sci. Med. 1992, 34, 735–746. [CrossRef]

- English, J.; Wilson, K.; Keller-Olaman, S. Health, healing and recovery: therapeutic landscapes and the everyday lives of breast cancer survivors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Pitt, H. Therapeutic experiences of community gardens: putting flow in its place. Health Place 2014, 27, 84–91. [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.; Franke, T.; McKay, H.; Sims-Gould, J. Therapeutic landscapes and wellbeing in later life: impacts of blue and green spaces for older adults. Health Place 2015, 34, 97–106. [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L.; Foley, R.; Houghton, F.; Maddrell, A.; Williams, A.M. From therapeutic landscapes to healthy spaces, places and practices: a scoping review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 196, 123–130. [CrossRef]

- Kaley, A.; Hatton, C.; Milligan, C. Therapeutic spaces of care farming: transformative or ameliorating? Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 227, 10–20. [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, S.; McMullan, C. Healing in places of decline: (re)imagining everyday landscapes in Hamilton, Ontario. Health Place 2005, 11, 299–312. [CrossRef]

- Kearns, R.; Milligan, C. Placing therapeutic landscape as theoretical development in Health & Place. Health Place 2020, 61, 102224. [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Peacock, J.; Sellens, M.; Griffin, M. The mental and physical health outcomes of green exercise. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2005, 15, 319–337. [CrossRef]

- Duff, C. Exploring the role of “enabling places” in promoting recovery from mental illness: a qualitative test of a relational model. Health Place 2012, 18, 1388–1395. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, N.; Wada, T.; Hirai, H.; Miyake, T.; Matsuura, Y.; Shimizu, N.; Kurooka, H.; Horiuchi, S. The effects of horticultural activity in a community garden on mood changes. Environ. Control Biol. 2008, 46, 233–240. [CrossRef]

- Sempik, J. Green care and mental health: gardening and farming as health and social care. Mental Health Social Inclusion 2010, 14, 15–22. [CrossRef]

- Almedom, A.M. Social capital and mental health: an interdisciplinary review of primary evidence. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 943–964. [CrossRef]

- Boardman, J. Social exclusion of people with mental health problems and learning disabilities: key aspects. In Social Inclusion and Mental Health, Boardman, J., Currie, A., Killaspy, H., Mezey, G., Eds.; Royal College of Psychiatrists: Cambridge, 2010; pp. 22–45.

- Howarth, M.; Griffiths, A.; Da Silva, A.; Green, R. Social prescribing: a “natural” community-based solution. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2020, 25, 294–298. [CrossRef]

- Andresen, R.; Oades, L.G.; Caputi, P. Psychological Recovery: Beyond Mental Illness; John Wiley & Sons: London, 2011.

- Gesler, W.M. Therapeutic landscapes: theory and a case study of Epidauros, Greece. Environ. Plan. D 1993, 11, 171–189. [CrossRef]

- Wood, V.J.; Gesler, W.; Curtis, S.E.; Spencer, I.H.; Close, H.J.; Mason, J.; Reilly, J.G. ‘Therapeutic landscapes’ and the importance of nostalgia, solastalgia, salvage and abandonment for psychiatric hospital design. Health Place 2015, 33, 83–89. [CrossRef]

- Doughty, K. Walking together: the embodied and mobile production of a therapeutic landscape. Health Place 2013, 24, 140–146. [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. Changing geographies of care: employing the concept of therapeutic landscapes as a framework in examining home space. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 55, 141–154. [CrossRef]

- Hallman, B.C. A “family-friendly” place: family leisure, identity and wellbeing—the zoo as therapeutic landscape. In Therapeutic Landscapes, Williams, A., Ed.; Routledge: London, 2017; pp. 133–145.

- Bell, S.L.; Phoenix, C.; Lovell, R.; Wheeler, B.W. Seeking everyday wellbeing: the coast as a therapeutic landscape. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 142, 56–67. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Cui, Q.; Xu, H. Desert as therapeutic space: cultural interpretation of embodied experience in sand therapy in Xinjiang, China. Health Place 2018, 53, 173–181. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Natural versus urban scenes: some psychophysiological effects. Environ. Behav. 1981, 13, 523–556. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [CrossRef]

- Annerstedt, M.; Währborg, P. Nature-assisted therapy: systematic review of controlled and observational studies. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 371–388. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, P.; Gartrell, G.; Egg, G.; Nolan, A.; Cross, M. End-of-life care in a community garden: findings from a participatory action research project in regional Australia. Health Place 2017, 45, 110–116. [CrossRef]

- Norfolk, D. The Therapeutic Garden; Bantam Press: London, 2000.

- D’Andrea, S.J.; Batavia, M.; Sasson, N. Effect of horticultural therapy on preventing the decline of mental abilities of patients with Alzheimer’s type dementia. J. Ther. Hortic. 2007, 18, 9–13.

- Donnelly, G.F. Therapeutic gardening. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2006, 20, 261. [CrossRef]

- Pitt, H. Therapeutic experiences of community gardens: putting flow in its place. Health Place 2014, 27, 84–91. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.L.; Monroy, M.; Keltner, D. Awe in nature heals: evidence from military veterans, at-risk youth, and college students. Emotion 2018, 18, 1195–1202. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L.; Keena, K.; Pevec, I.; Stanley, E. Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence. Health Place 2014, 28, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.F.; Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C. Views of nature and self-discipline: evidence from inner city children. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 49–63. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Gallardo, J.R.; Verde, A.; Valdés, A. Garden-based learning: an experience with “at risk” secondary education students. J. Environ. Educ. 2013, 44, 252–270. [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Dixon, P.S. Impact of garden-based learning on academic outcomes in schools: synthesis of research between 1990 and 2010. Rev. Educ. Res. 2013, 83, 211–235. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ro, E.; Lee, T.J.; An, B.C.; Hong, K.P.; Yun, H.J.; Park, E.Y.; Cho, H.R.; Yun, S.Y.; Park, M.; et al. The multi-sites trial on the effects of therapeutic gardening on mental health and well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8046. [CrossRef]

- American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD). Intellectual Disability: Definition, Classification, and System of Support; AAIDD: Washington, DC, 2010.

- Schalock, R.L. International perspectives on intellectual disability. In Cross-Cultural Psychology: Contemporary Themes and Perspectives, Keith, K.D., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing: West Sussex, 2010; pp. 312–328.

- Lotan, M.; Isakov, E.; Kessel, S.; Merrick, J. Physical fitness and functional ability of children with intellectual disability: effects of a short-term daily treadmill intervention. ScientificWorldJournal 2004, 4, 449–457. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, W.L.; Lindsay, R.L. Interpersonal disabilities: social skill deficits in older children and adolescents. Their description, assessment, and management. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 1992, 39, 551–567. [CrossRef]

- Walton, K.M.; Ingersoll, B.R. Improving social skills in adolescents and adults with autism and severe to profound intellectual disability: a review of the literature. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 594–615. [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, P. Qualitative Research Methods (3rd ed.), 2009. Oxford University Press, South Melbourne.

- Burt, K.G.; Luesse, H.B.; Rakoff, J.; Ventura, A.; Burgermaster, M. School Gardens in The United States: current barriers to integration and sustainability. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 1543–1549. [CrossRef]

- Lohr, A.M.; Krause, K.C.; McClelland, D.J.; Van Gorden, N.; Gerald, L.B.; Del Casino Jr., V.; Wilkinson-Lee, A.; Carvajal, S.C. The impact of school gardens on youth social and emotional learning: a scoping review. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2021, 21, 371–384. [CrossRef]

- Desmond, D.; Grieshop, J.; Subramaniam, A. Revisiting Garden-Based Learning in Basic Education; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, 2004.

- Subramaniam, A. Garden-Based Learning in Basic Education: A Historical Review [Monograph]; Centre for Youth Development, University of California, 2002.

- Bowker, R.; Tearle, P. Gardening as a learning environment: a study of children’s perceptions and understanding of school gardens as part of an international project. Learning Environ. Res. 2007, 10, 83–100. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Ro, M.R.; Lee, Y.S. Effects of horticultural activities on anxiety reduction of female high school students. Acta Hortic. 2004, XXVI, 249–251. [CrossRef]

- Krasny, M.E.; Tidball, K.G. Applying a resilience systems framework to urban environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 465–482. [CrossRef]

- Dunkley, R.A. Learning at eco-attractions: exploring the bifurcation of nature and culture through experiential environmental education. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 47, 213–221. [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: a literature review on restorativeness. Behav. Sci. (Basel) 2014, 4, 394–409. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, A.; Rossero, E. “It is like post-traumatic stress disorder, but in a positive sense!”: new territories of the self as inner therapeutic landscapes for youth experiencing mental ill-health. Health Place 2024, 85, 103157. [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare, T. The social model of disability. In The Disability Studies Reader, Davis, L.J., Ed.; Psychology Press: London, 2006; pp. 197–204.

- Milligan, C.; Gatrell, A.; Bingley, A. ‘Cultivating health’: therapeutic landscapes and older people in northern England. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 1781–1793. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Ter Heijne, M. Fear versus fascination: an exploration of emotional responses to natural threats. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 261–272. [CrossRef]

- Howarth, M.; Lawler, C.; da Silva, A. Creating a transformative space for change: a qualitative evaluation of the RHS Wellbeing Programme for people with long term conditions. Health Place 2021, 71, 102654. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).