1. Introduction

When our bodies change through illness, injury, or disability, so too does our relationship with ourselves. The associated physical transitions may significantly alter women’s orientations toward their bodies, challenging established notions of functionality, capability, and self-worth (Crooks, 2016; Rice et al., 2015; Thomas et al., 2019). Globally, approximately 16% of society are living with some form of disability (World Health Organization, 2022). Previous research has explored connections between outdoor activity and positive body image (Breault-Hood et al., 2017; Mitten & D’Amore, 2017), but we face a critical gap: how do women experience these outdoor spaces during or after physical challenges? Outdoor environments may offer unique qualities—sensory richness, absence of performance metrics, freedom from judgmental gazes—that create distinctive possibilities for women to reclaim agency during physical transitions.

Research has established promising relationships between time spent in natural environments and positive body image (Bacevičienė et al., 2021; Swami et al., 2016, 2018, 2019, 2020), with physical activity in nature mediating this relationship (Bacevičienė et al., 2021). Despite these insights, there remains no established theory explaining the relationship between body image and physical activity (Martin-Ginis et al., 2012), which is a gap more pronounced when considering diverse embodiments. In this paper, we use the term “diverse embodiments” to encompass the full spectrum of lived bodily experiences among women with illness, injury, and disability, acknowledging the varied ways these individuals inhabit, experience, and engage their bodies in the world. Embodiment refers to the “lived experience of engagement of the body in the world” (Piran & Teall, 2012, p. 171), offering a lens through which we can explore and honour these varied bodily realities and their significance.

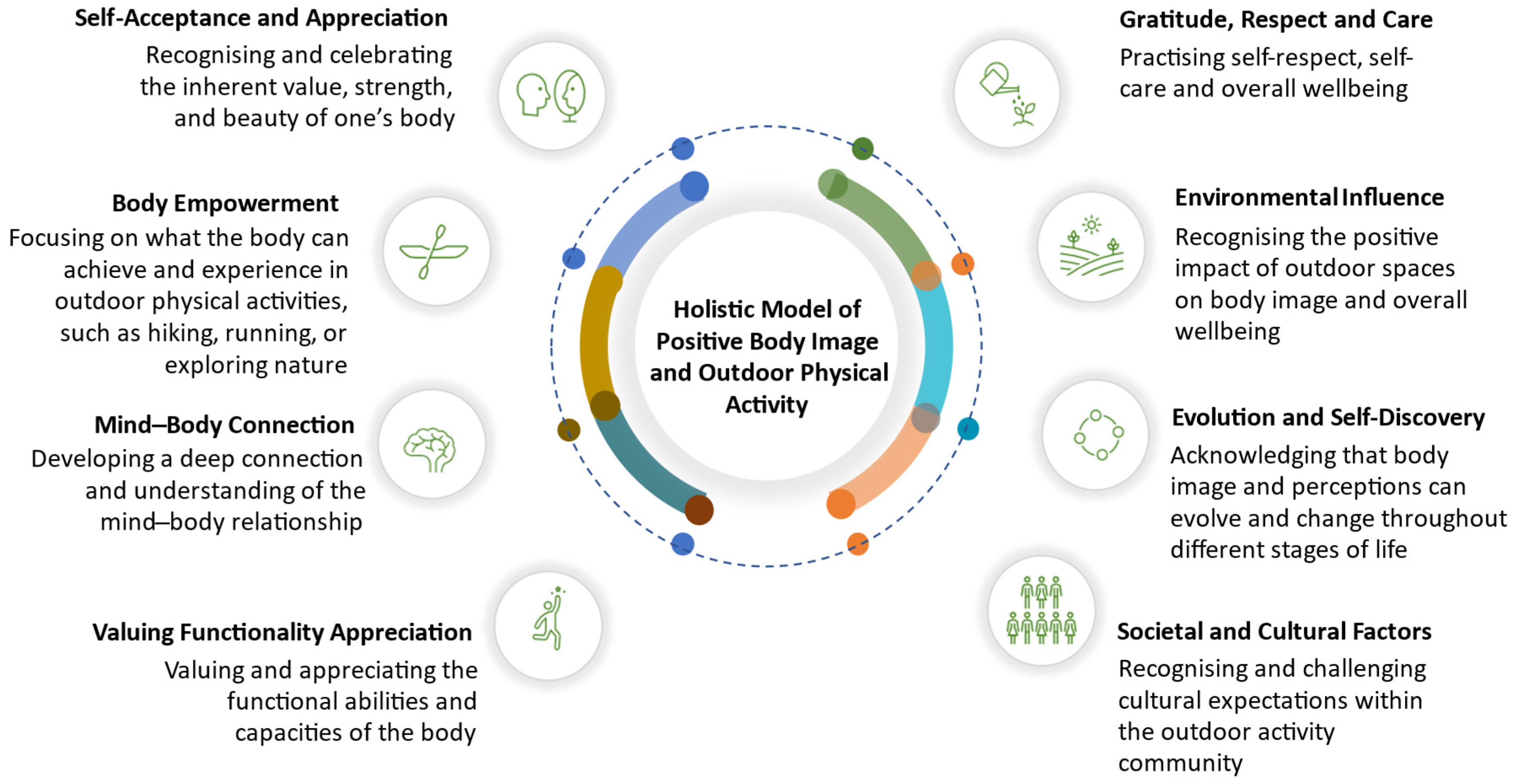

This paper extends Breault-Hood’s (2023) Holistic Model of Positive Body Image and Outdoor Physical Activity (

Figure 1) by examining how its eight principles apply to women experiencing physical challenges. Through secondary analysis of data from participants who identified as having illness, injury, or disability in the original study (

N = 84), we interrogate each principle of the model through the lens of diverse embodiments. This approach centres the voices of women navigating physical challenges, enriching theoretical understanding and informing more inclusive approaches to outdoor engagement.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Transformative Potential of Nature Immersion and Outdoor Physical Activity

Research increasingly recognises how physical activities in natural environments reshape bodily relationships. Piran’s (2017) work shows physical activity fosters agency and embodied connection, while Tylka and Piran (2019) established positive body image as multidimensional, extending beyond mere absence of dissatisfaction to include active appreciation and respect for the body. Outdoor settings offer powerful contexts for positive body image development. Mitten and D’Amore (2017) found that immersion in natural environments during physical activity created unique opportunities for women to experience their bodies as capable.

Participation in outdoor activities amongst like-minded women fosters resilience during challenging periods (Buckley & Westaway, 2020; Chen et al., 2024; Houge Mackenzie et al., 2021; Pomfret et al., 2025). Recent findings confirm outdoor recreation enhances mental wellbeing, boosting coping mechanisms and reducing stress (Pomfret et al., 2024). Women who regularly trail run experience strong community, increased self-confidence, enhanced adaptability, and improved mental wellbeing (Lincoln, 2021). Women increasingly pursue restorative experiences in nature to counteract frenetic lifestyles and seek meaning (Alizadeh & Filep, 2023; Pomfret et al., 2024).

Research provides insight into how outdoor physical activity supports positive body image. Alleva et al. (2020) found functionality-focused interventions enhanced body appreciation while reducing appearance concerns. Tylka and Homan (2015) revealed exercise motivated by functional goals rather than appearance associated with greater intuitive eating and body appreciation. Yet most outdoor programming remains designed for normative bodies (Seaman et al., 2014). The specific mechanisms of nature exposure on body image require examination, as different natural environments may have varying effects, with blue spaces potentially offering unique benefits compared to green spaces (Rygal & Swami, 2021; Stieger et al., 2022). Sundgot-Borgen et al. (2022) found self-compassion and nature connectedness together explained substantial variance in body appreciation. These relationships remain underexplored for women navigating illness, injury, or disability.

2.2. Bodies, Narratives, and Identity During Physical Transitions

Sociocultural theories show how beauty standards become internalised and shape bodily self-evaluations (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Tiggemann, 2011). For women with illness, injury, or disability, these standards intersect with ableist expectations, further marginalizing diverse embodiments (Rice et al., 2021). Garland-Thomson’s (2011) “fitting” and “misfitting” framework reveals how embodied experiences form through relationships between bodies and environments, creating connections either harmonious or disconnected based on “the degree to which that shared material world sustains the particularities of our embodied life” (2011, p. 596). Thomas et al. (2019) emphasise that body functionality research “should recognise what some bodies cannot do, and that many bodies function differently” (p. 89).

For women in outdoor activities, illness, injury, or disability that changes physical capabilities demands significant identity work. Allen-Collinson (2017) notes that “the assault on identity generated by illness, pain and injury has been well documented” (p. 267), though remains underexplored in non-elite contexts. When bodies change—temporarily, permanently, cyclically—women must negotiate “disrupted body projects” (p. 268). This disruption is not merely physical but existential. For women whose sense of self forms partly through outdoor engagement, physical challenges threaten both functional capabilities and core aspects of identity and belonging. The task becomes building new narratives about bodies, capabilities, and worth while navigating sociocultural pressures that render non-normative bodies invisible or problematic.

Research examining body image during illness and injury recovery reveals distinct psychological processes. Charmaz’s (2002) work shows how unpredictable symptoms create a ‘loss of self’ disrupting established body image. Papathomas et al. (2015) found challenges in temporary limitations—participants struggled reconciling former athletic identities with present limitations while projecting toward recovery. This narrative reconstruction differs following injury, where individuals experiencing temporary challenges seek a return to familiar stories, while those facing permanent conditions craft new narratives of identity and capability (Sparkes & Smith, 2013).

Feminist materialist disability theory presents promising avenues for expanding body functionality literature (Rice et al., 2021). By reconsidering “what a body can do,” this approach enriches conceptualisations of functionality in positive body image research. This perspective avoids prescribing what gendered, raced, or disabled bodies inherently are or do, instead acknowledging how social conventions, practices, and discourses shape physical capacities and materiality. It envisions the body as fundamentally dynamic, not fixed, but continually “becoming” (Rice et al., 2021). This framework operates bidirectionally by looking forward to analyse conditions that might broaden bodily potential, while examining evolving meanings of concepts that inform contemporary understandings.

2.3. Reimagining Bodies in Outdoor Contexts: Beyond Deficit Models

Alternative frameworks offer more empowering approaches to diverse embodiments. Garland-Thomson’s (2011) concept of misfitting shifts attention from individual broken bodies to environments designed without diverse physical bodies in mind. For women experiencing illness or injury, these misfits may be temporary or fluctuating, creating what Price (2015) describes as complex bodymind experiences—integrated physical and cognitive realities that challenge conventional frameworks and resist categorisation. “Bodymind” resists the mind/body split in Western thought that privileges the mind and treats mind and body as separate entities (Clare, 2017; Hendren, 2020). It reconfigures human embodiment as fluid and indivisibly entangled with the world, situating embodied experience as knowledge. Bodymind differences refer to embodied non-normatives or bodies and minds that westernized cultures define as outside “normal” (Clare, 2017).

Positive body image frameworks offer promising avenues for understanding this reimagining. Piran’s (2017) developmental theory of embodiment emphasises connection, agency, and freedom from objectification. For women experiencing physical challenges, these frameworks raise critical questions: What happens to functionality appreciation when what a body can do changes day by day? How might body acceptance be practiced when bodies feel unpredictable?

2.4. Research Gaps and Current Study

A critical limitation persists in the current research landscape: empirical studies have predominantly focused on women with normative bodies, creating significant conceptual and methodological gaps. Traditional quantitative measures developed with normative bodies in mind often fail to capture complex, fluctuating experiences (Bailey et al., 2016). Researchers have begun exploring body functionality among diverse populations. Thomas et al. (2019) examined how women with visible physical disabilities experience body functionality, while Tabaac et al. (2018) addressed intersectional perspectives on body image among transgender and gender-nonbinary individuals. However, these studies haven’t specifically examined how outdoor environments might mediate these experiences. To address this gap, the present study investigates how women with illness, injury, and disability experience outdoor physical activity, and how these experiences shape their body-self relationships.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This work takes up a secondary analysis (Heaton, 2008; Sherif, 2018) that returns to a dataset originally collected by Breault-Hood (2023) examining the Holistic Model of Positive Body Image and Outdoor Physical Activity. Secondary analysis creates possibilities for questions not imagined in original study designs, extending the impact of rich qualitative data. The original data collection was conducted through Qualtrics surveys distributed via Facebook groups and snowball sampling. From 553 female-identifying participants came multiple forms of data: structured responses, scaled measurements, and narrative contributions.

This secondary phase of analysis identified women whose experiences included illness, injury, disability, or recovery processes through a thorough review of open-ended responses. This screening process identified 84 women (15.2% of the original sample) whose narratives described significant experiences with physical challenges. Their physical transitions varied widely: from acute injuries and surgical recoveries to chronic conditions including autoimmune disorders, multiple sclerosis, and fibromyalgia; cancer diagnosis and treatment; pregnancy and birth-related physical changes; age-related transitions; temporary and permanent disabilities; and fluctuating conditions.

3.2. Participant Characteristics

Participants were predominantly middle-aged, with over half (52.4%) in the 45-64 age range. A striking difference emerged in employment status, with nearly a third (32.1%) reporting being unable to work—compared to only 3.8% in the overall sample. Despite this employment disparity, 82.2% described their finances as “moderately well” or “very well.” What proved especially significant is how these women engaged with outdoor spaces despite their physical challenges: 60.8% participating 2-4 times per week or more frequently (compared to 43.7% in the overall sample), predominantly at moderate intensity (75.0%). Notably, 82.1% reported that their body perception had changed positively through outdoor physical activity, suggesting that natural environments offered meaningful contexts for reimagining body-self relationships despite physical challenges.

3.3. Analytical Framework

3.3.1. Development of the Original Model

The Holistic Model of Positive Body Image and Outdoor Physical Activity emerged in response to limitations in existing body image frameworks, which have historically overlooked outdoor physical activity contexts and women’s experiences. The model builds upon Wood-Barcalow et al.’s (2010) conceptualisation of positive body image, extending the model by explicitly centring the outdoor environment as a mediating factor in women’s body image development. Theoretical foundations for this approach draw from Piran’s (2017) Developmental Theory of Embodiment, particularly its dimensions of body connection/comfort and agency/functionality. Empirical support for the model’s focus comes from recent research, with Mitten and D’Amore (2017) finding that immersion in natural environments creates unique opportunities for women to experience their bodies as capable rather than decorative.

Methodologically, the model was developed through a convergent mixed methods approach, integrating quantitative findings and qualitative insights from thematic analysis. Specifically, quantitative data established significant correlations between outdoor activity frequency and both body appreciation and functionality appreciation. The model articulates eight interconnected principles (shown in

Figure 1) that collectively address self-acceptance, body empowerment, mind-body connection, functionality appreciation, environmental influence, and sociocultural contexts as they relate to positive body image development through outdoor physical activity.

3.3.2. Theoretical Framework for Disability-Informed Reinterpretation

This secondary analysis positions itself at the intersection of disability studies and women’s outdoor experiences—two areas rarely examined together. While the original model centred women’s experiences, it did not explicitly address how disability might mediate these experiences. This gap reflects broader trends where diverse embodiments are often rendered invisible in outdoor programming (Laurendeau et al., 2020). This study is positioned as a model extension that examines the boundaries of the original framework. Following Kafer’s (2020) argument that disability perspectives can ‘crip’ or ‘reimagine’ existing theoretical models, this analysis asks how the experiences of women with illness, injury, or disability might enrich or challenge The Holistic Model of Positive Body Image and Outdoor Physical principles.

3.4. Data Analysis Procedures

Reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2019) guided the data analysis process, providing both methodological structure and interpretive flexibility. Following this analytical approach, Breault-Hood’s (2023) eight principles were used as sensitising concepts while remaining open to unexpected patterns across 84 narratives of embodied experience. The eight principles from the original model served as sensitising concepts (Bowen, 2006)—not rigid categories but attentional guides. Throughout, a reflexive journal was maintained documenting analytical decisions, enhancing rigor by tracing how interpretations evolved through engagement with both theory and participants’ accounts. For this reinterpretation, we draw on feminist disability theory (Garland-Thomson, 2011; Hall, 2011) and critical embodiment perspectives (Rice et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2019). This theoretical framing acknowledges that the original model primarily reflected experiences of normative bodies. As Wendell (2001) notes, traditional body image frameworks often presume stable, predictable embodiment—an assumption challenged by the fluctuating nature of many illnesses and disabilities.

3.5. Researcher Positionality and Reflexivity

Researchers engaging with narratives of physical challenge are influenced by their own embodied experiences, which shape how they approach, interpret, and represent these narratives. The research team brings lived experience of multiple physical challenges to this analysis. For instance, the lead researcher has endured spinal surgeries and recovery from brain tumour resection resulting in facial paralysis, vestibular issues, and single-sided deafness. These experiences have provided an understanding of both temporary and permanent physical adaptations. This insider positioning offers both strengths and potential limitations. The researchers’ lived experiences allow for recognition of nuances in how women describe navigating physical limitations, while requiring vigilance against universalising individual experiences. Throughout the analysis, a reflexive stance was maintained, documenting how bodily experiences informed interpretations while noting where participants’ experiences diverged from the researchers’ own. The analysis was approached with awareness of the danger of imposing a single narrative of physical challenge onto diverse experiences. Following feminist disability scholarship, the research centred the embodied knowledge of women navigating physical challenges while remaining alert to how researchers’ own experiences might both enhance understanding and potentially limit it.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

The primary data collection received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee at Western Sydney University (HREC Approval Number: H11143). For this secondary analysis, we maintained the same rigorous ethical standards. All data remained anonymised, with pseudonyms used throughout. Given the potentially sensitive nature of narratives about physical challenges and body image, we approached the analysis with enhanced sensitivity to respect participants’ experiences while protecting their privacy.

4. Findings: Bodies That Pause, Bodies That Persist

For this secondary analysis, we isolated responses from the original sample of N = 553 female participants, focusing specifically on the 84 participants (15.2%) who identified as having illness, injury, or disability. Using reflexive thematic analysis guided by Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step approach, we re-examined these participants’ qualitative responses through the framework of Breault-Hood’s (2023) Holistic Model of Positive Body Image and Outdoor Physical Activity.

The analytical process involved several steps: (1) familiarisation with the data subset, (2) initial coding focusing on illness, injury, and disability experiences, (3) organising codes around the eight principles of the model, (4) reviewing themes for coherence, (5) refining and naming themes that reflected the unique experiences of participants with diverse embodiments and (6) producing the analysis presented below. Throughout this process, we maintained a disability-informed interpretive lens to identify how each principle manifested differently for women with physical challenges compared to the general population.

Our analysis reveals not merely differences but divergent orientations: bodies temporarily displaced from familiar capabilities versus bodies permanently reoriented to alternative possibilities. As Ahmed (2006) notes, illness, injury, and disability fundamentally alter how we “reside in space” (p. 1), creating “moments of disorientation” (p. 157) that require new ways of inhabiting both bodies and environments. Through this disability-informed lens, each principle from the original model transforms in significant ways, providing deeper insight into how participants with physical challenges experience their body-self relationships.

By reinterpreting the model through the experiences of women with physical challenges, we move beyond simply accommodating diverse embodiments to recognising how diverse embodiments might transform our theoretical understanding. The following sections explore each of the eight principles through participants’ lived experiences, illuminating how physical challenges create distinctive body-self relationships in outdoor contexts. For each principle, we present participants’ direct quotations to centre their voices and experiences, followed by analytical interpretations that will be integrated with existing literature in the discussion section.

4.1. Self-Acceptance Through Physical Challenges

When bodies change through illness or injury, self-acceptance and body appreciation become not a peaceful reconciliation but an ongoing labour—what Charmaz (2002) describes as navigating the loss of self that accompanies physical transitions. For participants in this study, self-acceptance operated as a continual practice of befriending a body that may feel unfamiliar, of making home in altered terrain.

Participants with acute injuries identified patience as central to the process of self-acceptance—a temporary suspension of expectation, a waiting for return. But for those with chronic conditions or disabilities, our data showed that acceptance became something more profound: not waiting for but dwelling with, not recovery but discovery of alternative ways of being in bodies.

A participant diagnosed with endometriosis wrote:

“The last two years I have struggled more than usual - I was diagnosed with endometriosis which has led to weight gain but also to not being able to use my body in the ways I have done for most of my life. I get tired, and sore, and I’m scared of making things worse or over-exerting myself. I am sometimes angry at my body for not being the reliable friend it has always been.”

Notice the relational language—the body as “friend,” albeit an unreliable one. This reveals what Thomas et al. (2019) term disrupted embodiment, where the body becomes simultaneously self and other. But perhaps more revealing is the emotional landscape: struggle, fear, anger. Self-acceptance in our participants’ accounts is not absence of negative emotion but their incorporation into a more complex relationship with embodiment.

For a participant with multiple sclerosis, this labour produces a different orientation: “I have a neurological disease so even though I have body image issues I am extremely grateful that I have a fully functioning body.” Interestingly, the conjunction “even though” marks a space of tension between “image issues” and “gratitude,” and between social ideals and material function. The phrase “fully functioning body” itself deserves interrogation; what constitutes “full” function when society’s measuring stick presumes normative capability? For these participants, self-acceptance became not an achievement but a practice; it was not a destination but a continual arrival. Our data shows that for women with physical differences, this practice occurs not in isolation but against and within social forces that render certain bodies problematic.

4.2. Agency During Recovery

Body empowerment shifts from dominance or control to what Allen-Collinson (2017) calls disrupted body projects—the sustained effort to maintain continuity when physical capabilities change. Among our participants, agency manifested not as command but as conversation, as negotiating with rather than controlling the body. Participants developed what Crooks (2016) terms embodied expertise, choreographing movements within new constraints.

Participants recovering from acute illness or injury described reclaiming agency through linear trajectories—a gradual return to familiar capability. But for those with chronic conditions, our data revealed that agency manifested differently: as adaptation, as pacing, as finding alternate routes to desired experiences.

A participant who experienced cancer reflected: “I had cancer 11 years ago and spent a year on crutches. I will never ever take my health or my mobility for granted again. Every day I am able to move is a gift and opportunity.” Here, motion itself transforms from expectation to gift. This aligns with what Pini and Soldatic (2012) describe as the “material and discursive reconstitution” (p. 386) of embodied self—where the taken-for-granted becomes the newly appreciated.

For participants with chronic conditions, agency took on more complex dimensions. A participant with fibromyalgia explained:

“I have fibromyalgia so must exercise frequently and at moderate pace to keep healthy and avoid muscle flare ups and extreme fatigue. I’m incredibly grateful for what my body can do because I’ve seen the other side of the spectrum.”

Note the specialised knowledge embedded in this account—what Crooks (2016) terms “embodied expertise.” This participant has learned to navigate not despite but through her condition, developing what might be called a choreography of care—movements carefully calibrated to maintain rather than exhaust capacity. What if agency is not freedom from constraint but freedom within it? Our participants’ narratives suggest that physical limitations do not eliminate agency but transform it, requiring more attentive listening to what bodies can do. In outdoor environments particularly, this transformed agency manifests as creative adaptation—finding new relationships to movement itself.

4.3. Mind-Body Awareness Through Recovery

The mind-body connection deepens through necessity—what was once optional becomes essential. Our analysis found that physical limitations created heightened body awareness among participants, a specialised attunement to signals and sensations. The body becomes not an object to control but a source of knowledge to heed, particularly in unpredictable outdoor environments.

When the body changes, awareness shifts. For participants with acute injuries, this awareness often focused on learning to listen to the body during healing processes. For participants with chronic conditions, it evolved into sophisticated management strategies that accommodated fluctuating capabilities.

A participant recovering from injury reflected: “I am very aware of what my body needs to function well, and I am more inclined to rest now rather than push through and cause injuries if I am not feeling the best. It has taken a long time for me to be content with the body I have been given. I am much kinder and engage in more low-impact activities, lots of massage, and recover now too.”

The phrase “I am much kinder” invites us to consider: what does kindness toward one’s body mean in a culture that often celebrates pushing through pain? This enhanced mind-body connection reflects what Tylka and Piran (2019) describe as body attunement—an essential component of positive body image that involves listening and responding to bodily needs and sensations. For participants experiencing physical challenges, the body became not an object to be controlled but a source of knowledge to be heeded. In outdoor environments, our data shows this heightened awareness manifests as a specialised capacity to read and respond to bodily needs that emerges precisely from the experience of limitation.

4.4. Redefining Functionality After Limitation

Valuing functionality appreciation expands beyond celebrating what bodies can do to embrace what Thomas et al. (2019) identify as the complex, fluctuating nature of functionality for diverse embodiments. Function becomes not an absolute measure but a creative negotiation—acknowledging both capability and limitation, adaptation and persistence.

A central theme in our participants’ narratives was the process of redefining what functionality means after experiencing physical limitations. Participants with temporary injuries often focused on returning to previous functionality, while those with permanent disabilities developed entirely new frameworks for understanding functionality.

One participant with a prolapse after childbirth exemplified this redefinition:

“Post babies, I have a new perspective on my body. Having had a birth injury resulting in pelvic organ prolapse, I am mindful that my body does not function the same as it used to, but I’m also amazed at how I have adapted and can still do my favourite outdoor activity (mountain biking).”

Notice the coexistence of acknowledgment “does not function the same” and amazement “how I have adapted”. This narrative illustrates Thomas et al.’s (2019) argument that for women with physical challenges, body functionality encompasses not only what bodies can do, but also what they cannot do or do differently. The participant celebrates adaptation rather than focusing solely on limitation. Another participant described her changed relationship with functionality after hip surgery:

“I’ve had reduced functionality following one total hip replacement and ahead of another. This has been frustrating and I’m still in a level of regular pain. Nonetheless I’m back outdoors regularly because being outdoors makes me happy, and I have less years ahead than I’ve had before so I need to get moving!!”

The tension between “reduced functionality” and being “back outdoors” opens a space for questioning: what constitutes “function” in outdoor contexts? Is it pace, distance, difficulty of terrain? Or might it be presence itself—the being in natural spaces regardless of how that being occurs? Our participants’ narratives demonstrate the creative adaptability that women develop when navigating changed bodies. They move beyond binary understandings of ability/disability to embrace what remains possible. Functionality becomes not an absolute state but a creative negotiation with changing capability.

4.5. Gratitude Through Adversity

Gratitude and respect take on heightened significance through experiences of limitation. Our analysis revealed that among participants, gratitude emerges not despite constraint, but through it—a recognition of the body’s persistent gifts even when changed. Motion transforms from expectation to gift; capability from right to privilege.

Many participants expressed how experiences of illness, injury, or disability fostered deeper gratitude for their bodies—participants with temporary injuries often expressed gratitude for recovery processes, while those with permanent conditions developed appreciation for specific capabilities that remained intact. A participant with MS reflected: “Having MS, osteoporosis and T12 compression fracture, I’m grateful for anything my body allows me.” The phrase “anything my body allows me” reveals shifted orientation—from body as possession to body as granting permission, from capabilities as rights to capabilities as gifts. This shift represents a reorientation toward embodiment—learning to inhabit the body not as instrument but as companion.

Another participant who had experienced cancer shared:

“My body has experienced a life-threatening illness, and as a result, it is quite different than it used to be. And yet, I can do all that I do, and my body enables me to do it. How could I not love it?”

The rhetorical question suggests transformation not just in body but in relationship to body. This participant has moved from an aesthetic to a functional valuation, from body as visual object to body as enabling presence. These expressions of gratitude reflect what Tylka and Piran (2019) identify as “body appreciation”—a core element of positive body image. For participants with physical challenges, our data shows this appreciation arises from direct experiences of limitation. Gratitude emerges not despite limitation but through it—a recognition of the body’s persistent gifts even amidst constraint.

4.6. Therapeutic Landscapes in Recovery

Environmental influence gains new resonance through Garland-Thomson’s (2011) concept of misfitting—the productive friction between diverse embodiments and spaces designed for normative capabilities. Natural environments offer what built spaces often cannot: freedom from standardised metrics, from judgmental gazes, from prescribed ways of moving.

The meeting between diverse embodiments and natural environments creates distinctive possibilities for healing and adaptation. Participants frequently described outdoor settings as uniquely supportive during physical challenges—as if nature offered different possibilities for bodies in transition than built environments dominated by normative expectations. A participant who survived cancer described her experience:

“I underwent chemo and radiation ten years ago... I would go into radiation at 9:00 and then go to a trail he suggested... Although my body was sick and buttered by the intense treatment, being outside helped me regain my sense of self.”

The phrase “regain my sense of self” suggests outdoor environments offered not just physical but ontological restoration—spaces where identity disrupted by illness might be reclaimed. For participants managing chronic conditions, natural settings offered distinct respite: “I know whenever, when I am super low I can go to nature to bring myself back up. At least once a year I take a solo camping/hiking trip to reconnect myself to nature.” Nature becomes not just location but agent in recovery—a presence that actively participates in restoration.

These narratives support Mitten and D’Amore’s (2017) observation that natural environments offer unique therapeutic potential for body image. For participants with disabilities, our data suggests outdoor spaces can facilitate what Moss and Dyck (2003, p. 9) describe as a “radical body politics”—an approach that acknowledges how both material and discursive aspects of the body influence women’s negotiations of space and identity. These natural environments provide settings where bodies can be experienced outside the normative frameworks that dominate indoor spaces.

4.7. Transformation Through Physical Challenge

Evolution and self-discovery is reframed through Sparkes and Smith’s (2013) work on narrative reconstruction following injury. Our analysis revealed that participants’ bodies evolved along different trajectories: those temporarily challenged often sought return to familiar stories, while those with permanent conditions crafted entirely new narratives of identity and capability.

One participant reflected on how her outdoor experiences changed during long COVID:

“My relationship has changed a lot with my body in the last 6 months. It’s really frustrating not to do the activities I want to, but I know my body is working hard to fight the fatigue and inflammation from covid. It’s still my friend, even if I’m disappointed in it!”

This personification of the body as a “friend” despite disappointment aligns with what Allen-Collinson (2017) describes as the identity work required to maintain continuity in self-concept when physical capabilities change. The participant reconstructs her relationship with her body as a partnership rather than ownership.

Another participant described the transformation that occurred after experiencing temporary vision loss: “For a period, I only had 20% vision and couldn’t drive (later this was resolved with surgery). It was an interesting experience. I found numerous ways to compensate and manage with poor vision. I found I didn’t miss my sight much, and I didn’t fear loss of sight, instead I found new ways of living opening up using all my other senses, and I learned to respect those with real disabilities much more.” This narrative illustrates how physical challenges can lead to expanded perspectives, new skills, and increased empathy—transformations that extend beyond the physical body itself. In our participants’ accounts, physical challenge becomes not merely a limitation to overcome but a catalyst for becoming otherwise.

4.8. Community Support and Social Barriers During Recovery

Societal and cultural factors expand to address the intersecting pressures of ableism and gender norms. Participants with physical challenges navigated not just physical terrain but social landscapes that render certain bodies problematic, invisible, or inspirational—rarely just human.

The social dimensions of navigating illness, injury, and disability in outdoor settings emerged as a significant theme in our data. Participants with temporary injuries often received more readily accessible support, while those with chronic conditions faced greater challenges in finding appropriate communities and navigating inconsistent capabilities. One participant with a disability highlighted the importance of community:

“I have a mixed relationship with my body’s capabilities. Sometimes I am amazed at what it can do and appreciate its strength and resilience. I do however have an autoimmune condition, so sometimes my body needs rest or isn’t capable of doing things some would perceive as everyday tasks. It is very up and down but overall I appreciate that I can still get out and do hikes etc when I am well.”

This narrative highlights the fluctuating nature of many conditions and the importance of community understanding of these variations. As Crooks (2016) emphasises, women with chronic conditions must navigate not only their changing capabilities but also social expectations that presume consistent functionality. Another participant reflected on social barriers and expectations:

“I am overweight and have various health issues but feel proud and empowered undertaking the vigorous activities I do. I love people judge the way I look and are then surprised the level of fitness I have and what I can achieve.”

For many participants in our study, finding communities that focused on capability rather than appearance was crucial to maintaining outdoor engagement during and after recovery processes.

5. Discussion

5.1. Cyclical Rather Than Linear: A Reconceptualised Model

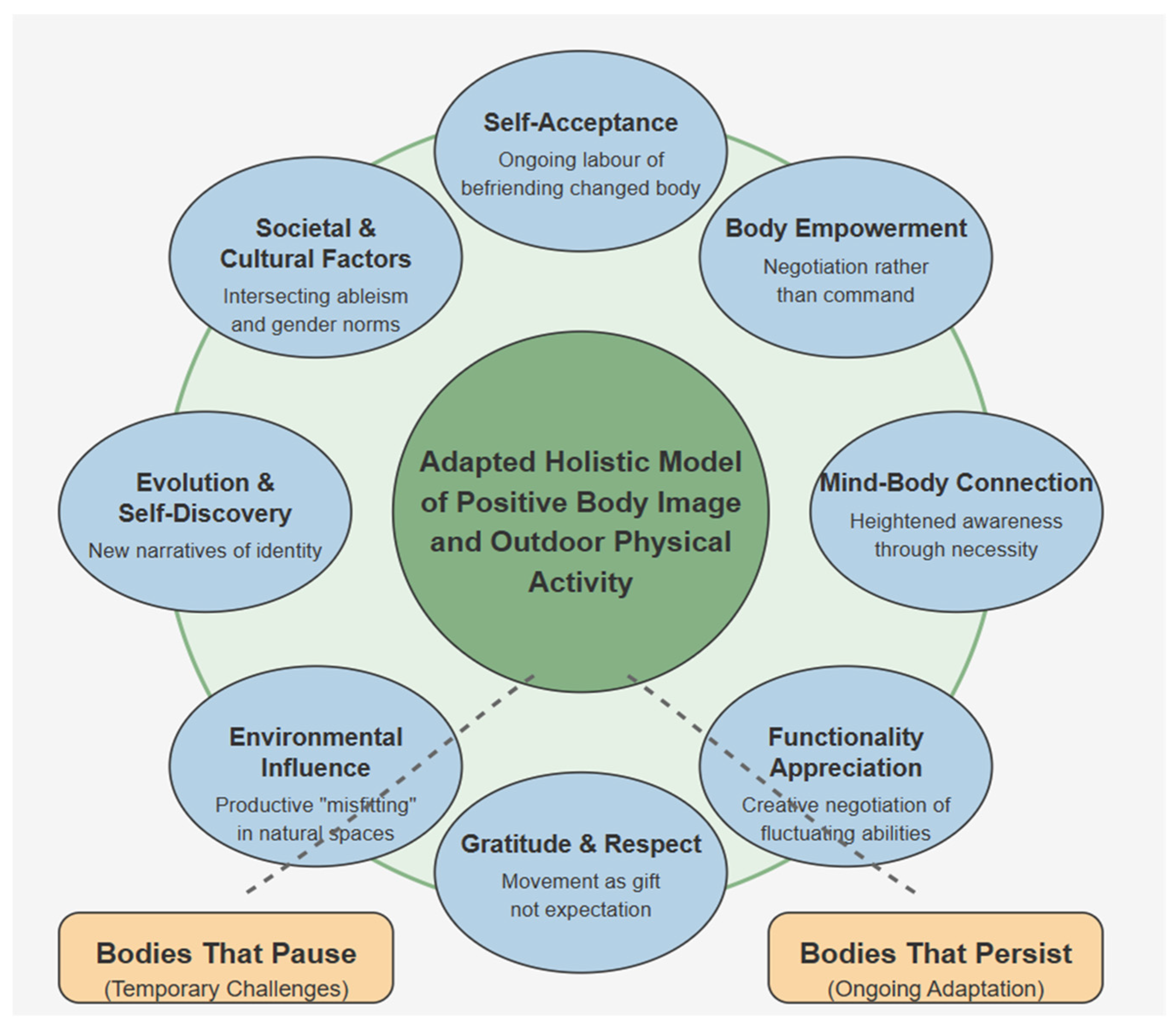

The thematic analysis revealed that the eight principles of Breault-Hood’s (2023) original model operate through distinct mechanisms when applied to women with physical challenges. Rather than following a linear progression, these women often described cyclical processes of adaptation, setback, and renewed engagement. This cyclical nature is particularly pronounced for those with chronic conditions, who must continuously renegotiate their relationship with outdoor environments as their capabilities fluctuate. This adapted model (

Figure 2) extends beyond the original framework by explicitly addressing the temporal dimensions of physical challenge—recognising that women’s relationships with their bodies evolve differently based on whether they are navigating temporary injuries, progressive conditions, or stable disabilities.

The findings suggest that outdoor environments offer distinctive contexts for this negotiation—spaces where bodies in transition might discover new possibilities for meaning, movement, and belonging. Rather than positioning adaptation as a compromise, the experiences of these 84 women reveal it as a form of embodied wisdom that transforms limitation into a site of potential.

5.2. Bodies Finding New Ways to Dwell

The findings extend existing understanding of the relationship between outdoor physical activity and positive body image by specifically examining the experiences of women navigating illness, injury, and disability. Several key insights emerge from this analysis: First, outdoor physical activity provides distinctive opportunities for women to reconcile changed or changing physical capabilities with their sense of identity. Unlike many indoor exercise contexts that emphasise standardised performance metrics or aesthetic outcomes, outdoor environments allow for more personalised definitions of achievement and success. The mountain that once was climbed quickly might still be climbed slowly; the trail once run might now be walked; the view once taken for granted might become newly significant when reached through different means.

Second, the natural environment itself plays a therapeutic role in recovery processes. Participants’ narratives suggest that outdoor settings offer sensory experiences, perspective shifts, and freedom from judgment that are particularly valuable during periods of physical vulnerability. Natural spaces—with their absence of mirrors, performance measurements, and standardised equipment—create room for bodies to move differently, to pause when needed, to find their own rhythms of engagement. This finding extends existing research on nature’s psychological benefits (Bratman et al., 2021), highlighting its specific relevance to body image during recovery.

Third, the study reveals the iterative relationship between physical recovery and psychological wellbeing. Participants’ accounts demonstrated how outdoor engagement facilitated both physical rehabilitation and psychological adjustment to changed bodies or capabilities. The physical challenge of navigating uneven terrain becomes simultaneously a psychological process of redefining capability; the sensory experience of wind on skin becomes a reminder of embodied presence despite limitation. This suggests that outdoor programs may offer unique benefits for holistic recovery approaches that address both physical and psychological dimensions of healing.

Finally, the findings highlight women’s resilience in redefining their relationships with their bodies through physical challenges. Rather than viewing illness or injury solely as disruptions to normal functioning, many participants integrated these experiences into expanded understandings of their bodies’ capabilities and worth. This reframing represents a form of resistance against limiting cultural narratives about disability, aging, and women’s bodies. The women in this study did not merely adapt to limitation but transformed their understanding of what bodies are for—moving from decoration to function, from standardised performance to personalised experience, from body as possession to body as companion.

5.3. Practical Implications

This study offers several important practical implications for professionals working with women experiencing physical challenges in outdoor contexts. For outdoor program providers, findings suggest a need to move beyond normative physical capability assumptions that exclude those with illness, injury, or disability (Wilson, 2017). Women’s experiences of “functionality” during physical challenges are highly personalised and fluctuating, calling for what Thomas et al. (2019, p. 91) term a “capability-sensitive approach”—offering multiple route options, flexible pacing, and redefining “success” beyond distance or technical difficulty.

Drawing on Crooks’ (2016) concept of embodied expertise, rehabilitation professionals might integrate outdoor experiences for clients to develop Piran’s (2017) body attunement. Natural environments offer distinctive therapeutic potential, as Caddick et al. (2015) observe that such settings facilitate embodied agency in ways indoor clinical settings cannot. Outdoor education can challenge its historical privileging of rugged physicality (Warren, 1998) and normative physical capabilities (Laurendeau et al., 2020). Educators might question “what sort of bodies and identities are being produced” (Newbery, 2003, p. 205) in outdoor pedagogical spaces, reimagining disability as a source of knowledge rather than limitation.

For researchers, this study highlights limitations in traditional body image measures developed for normative bodies (Bailey et al., 2016). New methodological approaches could capture the temporal dimensions of physical capability, recognising the fluctuating nature of bodily experience and employing participatory approaches that engage women as co-researchers. By centering the embodied knowledge of women experiencing physical challenges, practitioners across fields can create environments where diverse bodies are recognised not as problems but as sources of wisdom and possibility.