Submitted:

09 October 2024

Posted:

10 October 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

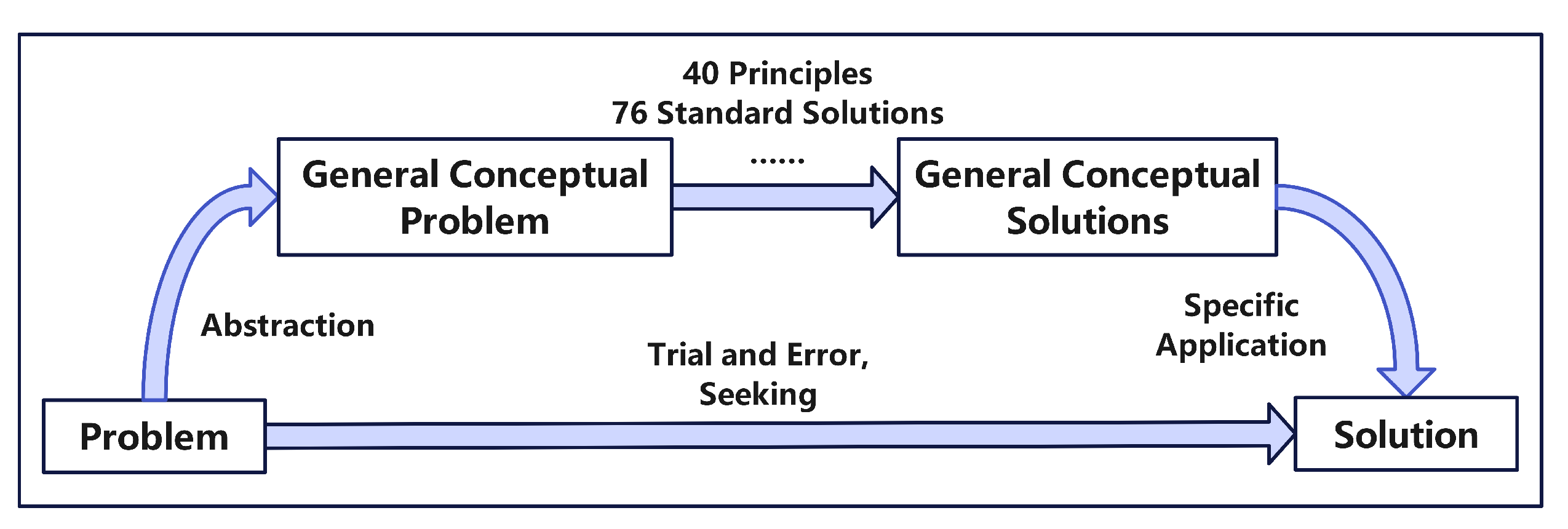

1. Introduction

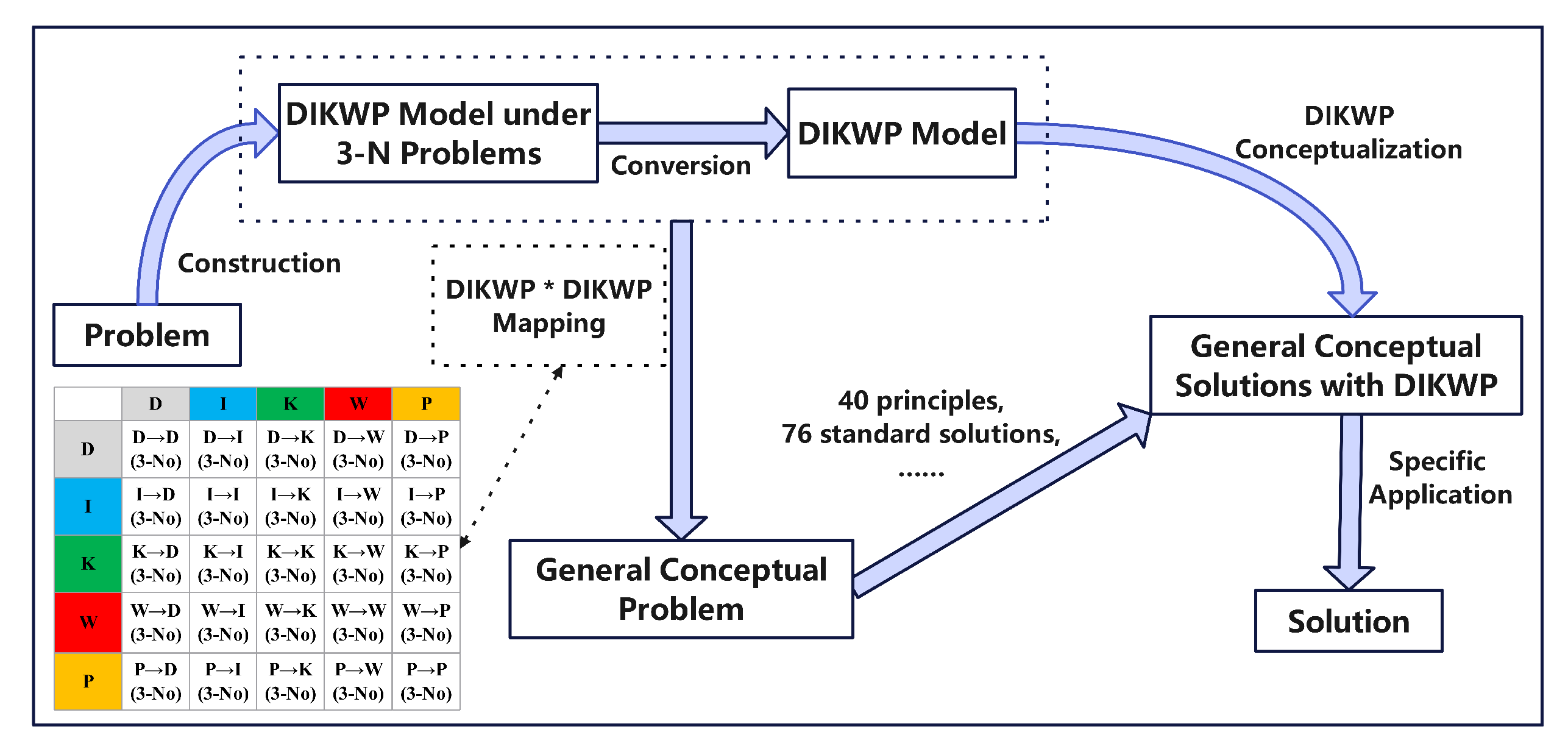

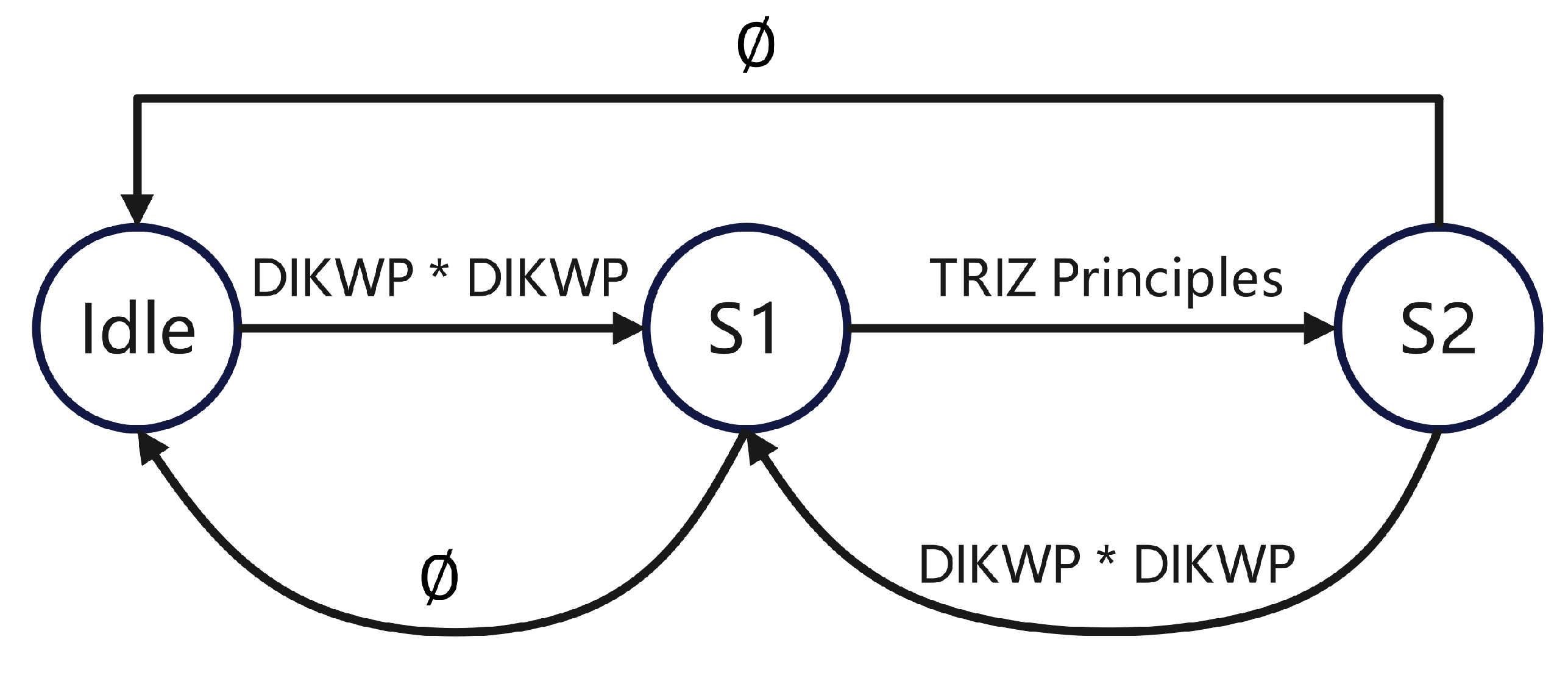

- Integration of DIKWP Model with TRIZ Methodology for Artificial Consciousness Innovation: This paper introduces the DIKWP-TRIZ framework, which integrates the elements of Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom, and Purpose (DIKWP) into the traditional TRIZ methodology. This integration provides a structured approach for applying TRIZ principles to cognitive processes, specifically aimed at addressing the complexities and ethical considerations involved in the development of artificial consciousness systems. By bridging the gap between cognitive modeling and inventive problem-solving, this approach offers a novel methodology that enhances innovation capabilities in complex, value-driven contexts.

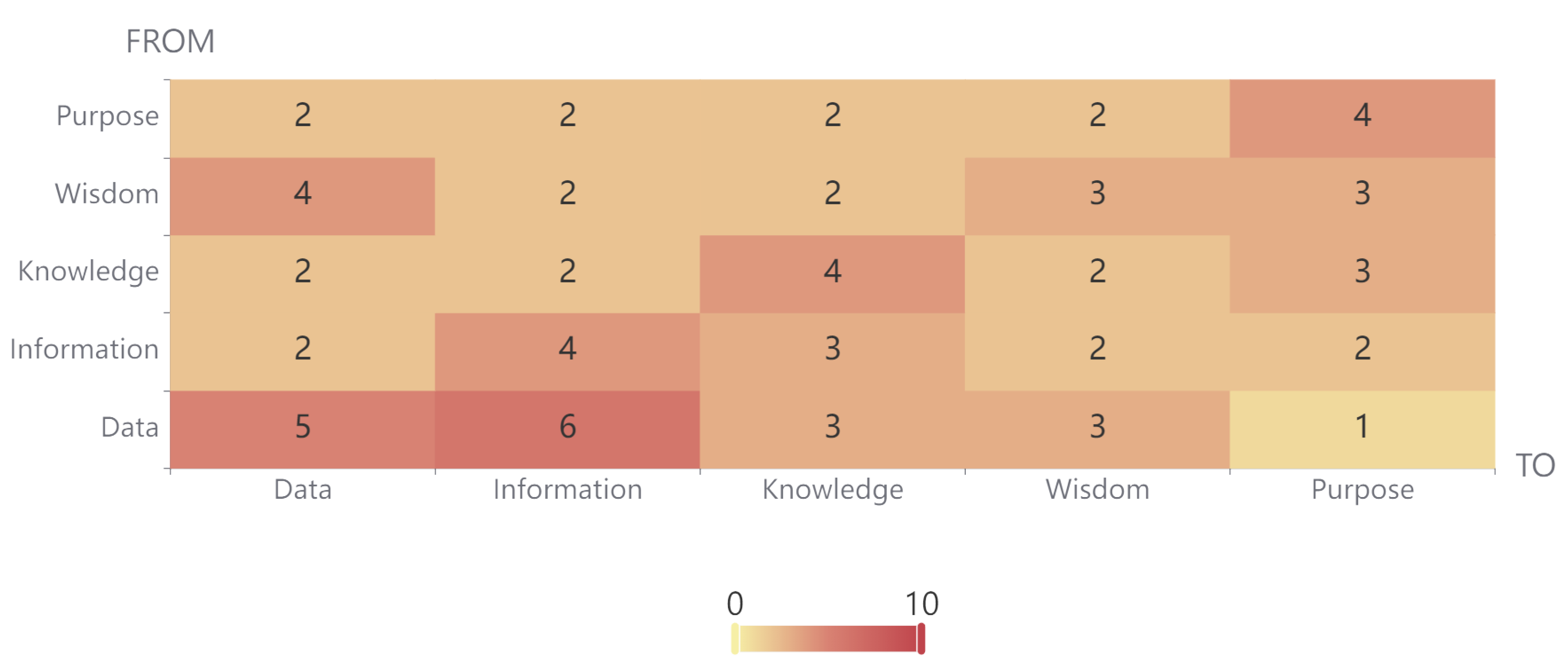

- Comprehensive Mapping of TRIZ Principles to Cognitive Transformations in DIKWP: The research systematically maps TRIZ principles to various cognitive transformations within the DIKWP model, such as the transition from data to knowledge or from wisdom to purpose. This mapping not only clarifies the applicability of each TRIZ principle in cognitive processes but also identifies overlaps and redundancies among the principles. By proposing a refined set of principles and contextual guidelines, the paper improves the precision and efficiency of TRIZ applications in complex cognitive scenarios, thereby facilitating more effective problem-solving and innovation.

- Development of a Methodological Framework for Reducing Redundancies and Enhancing Consistency in TRIZ-DIKWP Applications: The study addresses potential inconsistencies and redundancies in the application of TRIZ principles within the DIKWP framework by employing a cognitive space coverage integrity analysis and redundancy evaluation. The proposed methodological framework includes strategies for integrating overlapping principles and offers decision-making tools to guide practitioners in selecting the most appropriate principles for specific cognitive processes. This structured approach ensures a coherent and systematic application of TRIZ principles, enhancing the overall robustness and effectiveness of the DIKWP-TRIZ methodology.

2. Related Works

2.1. DIKWP Model

2.2. TRIZ Theory

3. Research Methodology

3.1. DIKWP Conceptualization

3.1.1. Data Conceptualization

3.1.2. Information Conceptualization

3.1.3. Knowledge Conceptualization

3.1.4. Wisdom Conceptualization

3.1.5. Purpose Conceptualization

3.2. Mapping TRIZ Principles to DIKWP Transformations

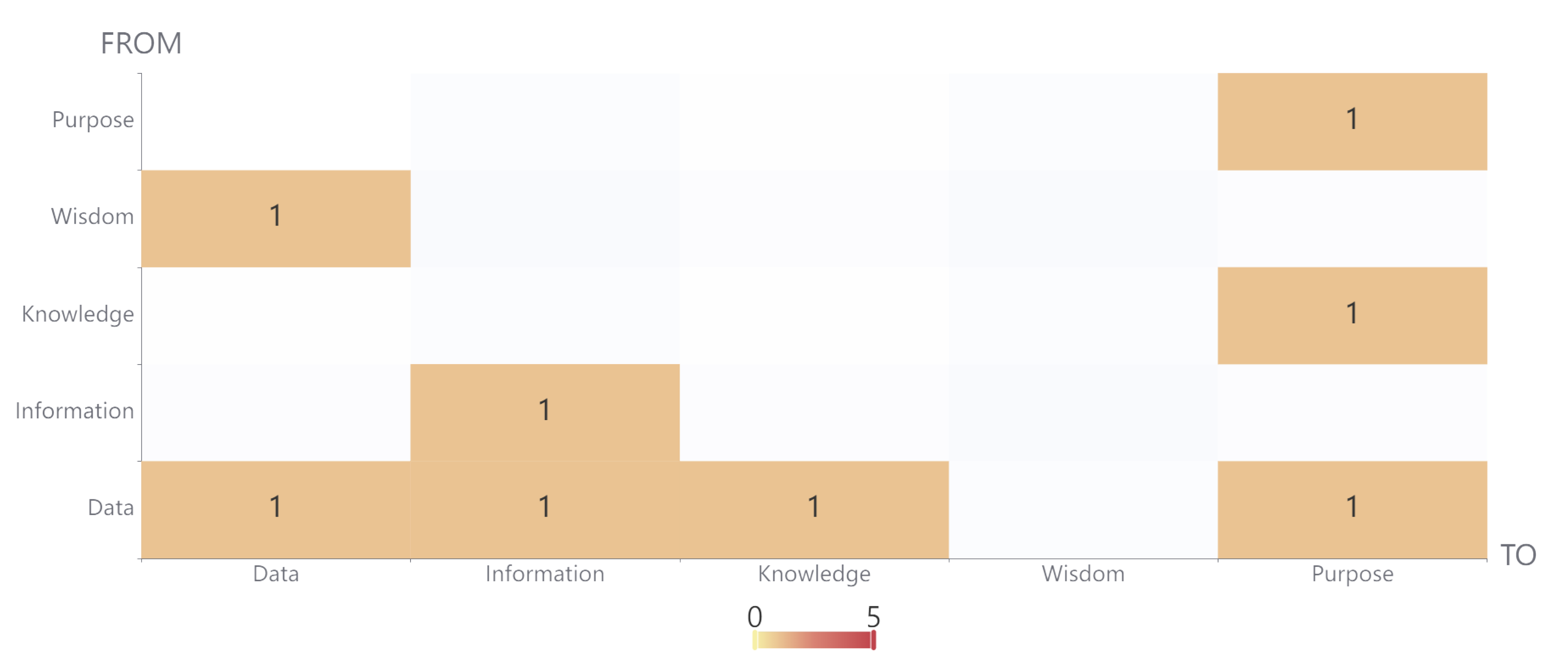

3.3. Cognitive Space Coverage Integrity Analysis

3.4. Evaluation of Redundancy and Inconsistency

4. Mapping and Coverage Analysis of TRIZ Rules in DIKWP

4.1. Mapping the 40 TRIZ Principles to the DIKWP Model

4.1.1. Data (D) → Data (D)

-

Principle 1: SegmentationThis principle involves dividing large datasets into smaller, more manageable segments to facilitate detailed analysis and obtain targeted insights. This strategy helps optimize resource utilization and enhances the efficiency of the analytical process [17].

-

Principle 2: Extraction

-

Principle 5: MergingIntegrating datasets from different sources to create a more complete and robust dataset. This not only enhances the overall accuracy of the data but also increases its utility, providing a solid foundation for decision-making [20].

-

Principle 10: Preliminary ActionsPreprocessing the data, such as cleansing, standardization, or structural adjustment, prior to formal analysis to ensure the smoothness and effectiveness of subsequent data operations. This step is essential in data analysis, as it directly impacts the quality of the final results. For instance, in data mining, preprocessing steps like data cleaning, normalization, and integration are essential for reducing noise and inconsistencies, which are common in large datasets. Proper preprocessing improves the performance of data analysis and mining algorithms, leading to more robust findings. Additionally, preprocessing also includes standardization, which ensures that all data points are on the same scale, enhancing the accuracy of analytical models and decision-making processes [21].

-

Principle 35: Parameter ChangesAdjusting parameters within the data, such as units, dimensions, or scales, to maintain consistency and enable meaningful comparisons across different datasets. By standardizing parameters, misunderstandings caused by differences in measurement can be avoided, ensuring the reliability and comparability of the analysis results. For example, standardizing units and scales helps prevent discrepancies caused by varying measurement systems, which is essential in fields such as scientific computing and statistical modeling. Automated systems for dimensional consistency checking in scientific programming highlight the importance of ensuring uniformity in units and parameters to avoid errors and maintain data integrity.

4.1.2. Data (D) → Information (I)

-

Principle 3: Local QualityFocus on analyzing specific data subsets to generate detailed information. This approach can reveal insights that might be overlooked from a global perspective, providing in-depth understanding at a local level. For example, in large-scale market research data, examining the behavior patterns of a particular consumer group can uncover unique preferences and needs, thereby informing product customization. For example, a study on large-scale software engineering data demonstrated the benefits of splitting data into smaller, more homogeneous subsets, resulting in improved model performance and more accurate predictions [22].

-

Principle 5: MergingIntegrate data points from various sources to form a coherent and valuable information system, facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. For instance, combining user behavior data, geographical information, and social media feedback can help companies build a more comprehensive user profile, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of marketing strategies.

-

Principle 9: Preliminary Anti-ActionThe principle of preliminary anti-action in TRIZ, which involves preprocessing steps like filtering out noise or irrelevant data, is crucial to enhancing the clarity and quality of information. For instance, techniques such as noise reduction in various applications, like hyperspectral imaging, improve the analysis of key signals by eliminating non-white noise prior to formal analysis [23]. Additionally, noise filtering algorithms can significantly improve data quality, especially in scenarios involving imbalanced data or chaotic signals, thereby enhancing the subsequent data analysis [24]. These preprocessing steps are essential for ensuring the authenticity and reliability of information, reducing potential biases during analysis, and improving the overall quality of results [25].

-

Principle 17: Another DimensionUtilize multidimensional representations of data, such as through visualization tools or multi-layered models, to reveal deeper insights and provide a rich and detailed understanding. For example, using three-dimensional charts to show trend changes in time series data or employing heat maps to illustrate the strength of correlations between variables can help analysts grasp data characteristics more intuitively.

-

Principle 28: Mechanics SubstitutionAutomate data processing tasks using algorithms and tools to efficiently transform large amounts of data into meaningful information. With the advancement of machine learning and artificial intelligence technologies, such automated methods have become an indispensable part of modern data analysis, significantly enhancing the speed and accuracy of information extraction.

-

Principle 35: Parameter ChangesBy altering the measurement standards, formats, or parameters of data, new information semantics can be revealed. In financial market analysis, applying different smoothing parameters to historical trading data can distinguish between short-term and long-term market fluctuations. For example, using moving averages with different periods (such as 5-day and 200-day moving averages) can identify short-term market volatility and long-term trends, thereby providing a basis for investment decisions.

4.1.3. Data (D) → Knowledge (K)

-

Principle 6: UniversalityExtract general principles or models from specific data points and extend localized insights to broader contexts. For example, in collaborative environments such as cross-functional software development teams, applying universal principles from one industry can enhance team knowledge sharing and efficiency across different sectors [26].

-

Principle 24: IntermediaryUtilize intermediate models, such as simulations or analytical frameworks, as bridges between raw data and refined knowledge to facilitate the understanding and interpretation of complex datasets. For example, In financial risk management, intermediary models like stochastic differential equations are used to model economic scenarios and bridge the gap between complex raw data and actionable insights [27].

-

Principle 35: Parameter ChangesAdjust the parameters of data collection and analysis based on existing knowledge to more precisely focus on core areas of data processing. For example, in climate research, the data collection frequency of observation stations can be adjusted according to existing climate change models to capture critical signals of climate variability.

4.1.4. Data (D) ← Wisdom (W)

- Principle 40: Composite Materials We extend the semantics of materials to transform them into data, while composites are expanded into multiple channels or methods serving as data sources. Correspondingly, in information technology, this process involves integrating various data sources and analytical models to generate comprehensive, high-quality decisions guided by wisdom. This approach is exemplified in applications such as financial risk management [28] and the formulation of optimized traffic management strategies [29], where diverse data inputs and sophisticated analysis converge to produce holistic, informed decisions.

4.1.5. Data (D) → Purpose (P)

-

Principle 4: AsymmetryWe can prioritize subsequent objectives based on the relevance of data collection and analysis activities to the intended purpose, ensuring that resources are concentrated in high-impact areas. This approach allows for a strategic allocation of efforts, maximizing the effectiveness of decision-making and optimizing outcomes by focusing on areas that most significantly contribute to achieving the desired goals.

-

Principle 11: Beforehand CushioningStakeholders utilize historical traffic and log data from the same period in previous years to proactively prepare data systems and infrastructure, supporting anticipated goal-driven demands and enhancing flexibility and readiness. For instance, in e-commerce platforms, to accommodate the surge in traffic during upcoming shopping seasons, stakeholders may upgrade server capacity and optimize database architecture in advance. These proactive measures ensure that the system can handle high concurrent access loads, thereby maintaining performance and reliability under increased demand [30,31].

-

Principle 15: DynamismMaintain a flexible data strategy that can evolve with changing purposes or goals, ensuring its ongoing relevance and effectiveness. For example, in a rapidly changing market environment, regularly evaluating and adjusting data analysis models to reflect the latest market demands and trends enables the organization to base its decisions on the most up-to-date information. For instance, the concept of asymmetric resource allocation is also applicable in situations involving emergency medical services. During mass casualty incidents, allocating resources based on prioritization, such as through column generation models, maximizes lifesaving capacity [32].

-

Principle 35: Parameter ChangesDynamically adjust data parameters to align with evolving goals, ensuring that data serves as an effective tool for achieving strategic objectives. For instance, in public health management projects, adjusting monitoring indicators based on changes in disease transmission patterns can reflect changes in public health conditions in a timely manner, providing accurate and timely data support for preventive measures.

4.1.6. Information (I) → Data (D)

-

Principle 10: Preliminary ActionBased on the differentiated content of information semantics, specific datasets that may be required in the future can be generated in advance. For example, by collecting meteorological information, agricultural data models can be developed beforehand, such as generating data on the projected impact of rainfall and temperature variations on crop yields. This proactive approach provides robust data support for agricultural decision-making, enabling stakeholders to make informed choices based on predictive insights.

-

Principle 22: Blessing in DisguiseNegative or anomalous elements within information can be transformed into specific data points for further analysis and decision-making. For instance, by identifying anomalies in business operations, such as production delays, specific operational data can be generated or retrieved to optimize production processes. This targeted approach enables a deeper understanding of underlying issues and supports the development of more effective strategies for process improvement and risk mitigation.

4.1.7. Information (I) → Information (I)

-

Principle 13: The Other Way RoundReorganize the flow or structure of information to promote better understanding and more effective communication of complex concepts. For example, in technical documentation, using inversion by first introducing practical application cases and then gradually explaining the theoretical background can help readers more easily grasp abstract concepts and technical details.

-

Principle 14: SpheroidalityPresent information in an interconnected format, such as through network diagrams or graphical representations, to highlight relationships and interdependencies between different pieces of information. This approach helps uncover patterns and connections hidden within vast amounts of data, enabling users to identify logical relationships between information segments. For instance, in financial analysis, using relational graphs to depict financial transactions between different companies can reveal potential market linkages.

-

Principle 17: Another DimensionThe cognitive subject can employ various forms of representation, such as charts and diagrams, to transform one type of differentiation into another, providing multiple perspectives and deeper insights into the information. For example, in data visualization, representing information across different dimensions, such as through multidimensional scaling and graph visualizations, can help users better understand high-dimensional data. A study on visualizing dimension coverage in exploratory analysis demonstrated that representing data visually with multiple perspectives helps analysts form new questions and gain deeper insights into datasets [33]. In market research, combining bar charts and pie charts can enhance the analysis by offering different viewpoints on the same data. For instance, visualizing research topics using a three-dimensional strategic diagram enabled researchers to gain a more nuanced understanding of interdisciplinary research areas and emerging trends [34]. This multi-faceted approach enhances the ability to analyze complex data and facilitates more informed and strategic decision-making.

-

Principle 35: Parameter ChangesWe can adjust the parameters of information semantic differentiation, such as the level of detail or presentation format, to enhance clarity and accessibility for diverse audiences. For instance, in popular science articles aimed at the general public, simplifying language and terminology, and using visual aids such as charts to illustrate complex scientific principles, can make the information more comprehensible to non-experts. This tailored approach ensures that the core message is effectively communicated, regardless of the audience’s level of expertise.

4.1.8. Information (I) → Knowledge (K)

-

Principle 15: DynamismAllow knowledge to evolve with the incorporation of new information, maintaining the relevance and timeliness of the knowledge structure. For example, in medical research, as new clinical trial results become available, updating clinical guidelines ensures that medical practices are always based on the latest evidence.

-

Principle 24: IntermediaryEmploy frameworks or models to transform information into knowledge, serving as a bridge between raw information and structured understanding. For instance, in the field of education, developing a curriculum as a framework to guide student learning helps integrate scattered learning materials into a systematic knowledge system.

-

Principle 34: Discarding and RecoveringUpdate knowledge by integrating new information and discarding outdated or irrelevant content to maintain the currency and effectiveness of the knowledge base. For instance, in legal consulting, regularly reviewing legal texts to remove outdated clauses and incorporate newly enacted laws helps maintain the accuracy and authority of legal opinions.

4.1.9. Information (I) → Wisdom (W)

-

Principle 23: FeedbackEmploy results to refine wisdom and the information processing process, forming a cycle of continuous improvement. This means that after each round of information processing, reflection and summarization are essential to adjust strategies based on actual outcomes. For example, in the field of education, teachers can continuously adjust their teaching methods based on feedback from students’ learning outcomes to improve the quality of instruction.

-

Principle 32: Color ChangesWe extend the semantics of color to the realm of presentation, such as modifying the format or framing of information to enhance the effectiveness of wisdom-based communication. This approach, which may include storytelling or contextualization, makes the information more engaging and impactful, thereby conveying it more effectively to the audience. For example, in marketing campaigns, communicating a product’s core values through a brand narrative, rather than simply listing its features, can create a deeper resonance with consumers.

4.1.10. Information (I) → Purpose (P)

-

Principle 16: Partial or Excessive ActionsAdjust the level of effort in information processing according to the specific requirements of the objective, ensuring that the information is neither excessive nor insufficient. This means determining the scope and depth of information collection and analysis based on the importance and required detail of the objective. For example, in project management, if the goal is to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of a project, efforts should be focused on collecting data directly related to costs and benefits, avoiding the collection of excessive unrelated data to improve the efficiency and relevance of information processing.

-

Principle 32: Color ChangesWe extend the semantics of color to the realm of presentation. Modify the presentation of information according to the objective to enhance the clarity and impact of information transmission. This principle emphasizes the importance of presentation format, suggesting that information should be expressed or visually represented in a way that better aligns with the needs of the target audience. For example, in corporate annual reports, to better convey the company’s performance and future outlook to shareholders, key financial data can be presented using charts, timelines, and other visual tools to make the information more intuitive and understandable [35,36,37].

4.1.11. Knowledge (K) → Data (D)

-

Principle 9: Preliminary Anti-ActionUse existing knowledge systems to pre-screen irrelevant data, ensuring that only valuable information is collected and analyzed. This approach not only improves data processing efficiency but also prevents irrelevant data from influencing the decision-making process. For instance, in the design phase of clinical trials, cases that do not meet the criteria can be excluded based on prior research findings, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the trial results.

-

Principle 25: Self-serviceApply existing knowledge systems to autonomously guide data collection and processing, reducing the need for external intervention. For instance, in the design of intelligent sensor networks, pre-set algorithms can be used to automatically identify important data streams and prioritize them, thereby optimizing resource allocation and enhancing the system’s adaptive capabilities [38,39].

4.1.12. Knowledge (K) → Information (I)

-

Principle 3: Local QualityThe key nodes and relationships within the knowledge structure are concretized into information content, aimed at addressing specific problems or application contexts. This process typically involves extracting critical components from the body of knowledge and transforming them into actionable information semantics that can be directly applied. By converting essential knowledge elements into practical information, this approach ensures that theoretical insights are effectively utilized in real-world scenarios.

-

Principle 13: The Other Way AroundGenerating specific information content based on the inverse logical relationships within knowledge is particularly useful in handling anomalies and reverse reasoning scenarios. This process involves reverse-analyzing causal relationships within the knowledge base to produce information that can explain or predict specific phenomena. For example, leveraging maintenance knowledge to perform reverse reasoning can generate diagnostic information about equipment failures, such as potential causes and corresponding solutions for a particular type of malfunction. This enables technical personnel to quickly identify the root cause of an issue, providing effective support in troubleshooting and decision-making during equipment failures [40].

4.1.13. Knowledge (K) → Knowledge (K)

-

Principle 16: Partial or Excessive ActionsAdjust the effort in the application and development of knowledge based on the specific contextual demands to ensure efficiency and relevance. This means dynamically modulating the allocation of resources in knowledge management according to actual needs, avoiding both overinvestment and underinvestment. For example, in academic research, researchers can adjust the breadth and depth of the literature review according to the specific phase of a project, ensuring that the research direction remains aligned with the current scientific frontier.

-

Principle 22: Blessing in DisguiseUtilize challenges or limitations within knowledge as opportunities to develop deeper understanding or new methodologies. This approach emphasizes the potential for breakthroughs in addressing problems and obstacles, advancing knowledge through critical thinking and innovation. For instance, in technological innovation, when faced with a technical bottleneck, it can be viewed as an opportunity to explore alternative solutions or develop entirely new approaches, thereby driving technological progress.

-

Principle 23: FeedbackContinuously refine knowledge through feedback loops, integrating new insights and experiences to enhance understanding. This implies establishing effective feedback mechanisms in the process of knowledge accumulation, regularly evaluating the practical application of knowledge, and making adjustments based on feedback. For example, in corporate management practices, the content of training programs can be continuously improved based on the evaluation of post-training outcomes to ensure that employee skills evolve in line with organizational needs.

-

Principle 34: Discarding and RecoveringUpdate knowledge by eliminating outdated concepts and incorporating new findings, maintaining a robust and up-to-date knowledge base. This method underscores the importance of knowledge renewal, retaining core knowledge while continuously discarding obsolete parts and adding the latest research outcomes. For example, in medical education, with the release of new clinical research results, teaching content should be promptly updated by removing disproven theories and including the latest medical practices.

4.1.14. Knowledge (K) → Wisdom (W)

-

Principle 15: DynamismAllow knowledge and wisdom to co-evolve over time, adapting to new information and changing contexts to maintain their relevance and effectiveness. This means that knowledge and wisdom should not be static but should continually update and develop in a changing environment. For instance, in medical research, as new discoveries emerge, existing treatment methods need to be constantly adjusted to align with the latest scientific understanding.

-

Principle 40: Composite MaterialsWe extend the semantics of materials to analyze and transform knowledge content. Combine diverse sources of knowledge to develop a more nuanced and comprehensive form of wisdom, integrating multiple perspectives and experiences. This approach highlights the importance of interdisciplinary knowledge integration and cross-domain learning, where the fusion of knowledge from different fields creates richer wisdom. For example, in public policy-making, integrating knowledge from social sciences, economics, and ethics can lead to more comprehensive and sustainable policy measures.

4.1.15. Knowledge (K) → Purpose (P)

-

Principle 25: Self-serviceEnable knowledge to autonomously adjust or redefine objectives, allowing goal setting to exhibit flexibility and adaptability based on new insights. This means that knowledge should possess a self-regulating capability, dynamically adjusting objectives according to newly acquired knowledge. For example, in research institutions, when a major breakthrough occurs in a particular field, researchers can independently adjust their research directions to ensure that their work remains at the forefront of academic progress.

-

Principle 31: Porous MaterialsWe will expand and extend the porous semantics. Therefore, this invention principle can be defined as maintaining the openness of objectives to the influx of new knowledge, allowing goals to dynamically adjust and optimize as understanding evolves. This method emphasizes the plasticity and adaptability of objectives, ensuring that goals are continually updated as new knowledge is acquired. For instance, in corporate strategic planning, regularly reviewing changes in the external environment and internal capabilities enables timely adjustments to the company’s development direction to respond to market changes [41].

-

Principle 35: Parameter ChangesAdjust objectives based on new knowledge to ensure that goals remain aligned with the latest insights and information. This implies that during the process of setting objectives, the latest advances in knowledge should be considered, updating goals in a timely manner to reflect new understandings. For instance, in public policy-making, when new scientific research indicates that a particular policy intervention may be more effective, the government should promptly adjust related policies to ensure their effectiveness and timeliness.

4.1.16. Wisdom (W) → Data (D)

-

Principle 6: UniversalityWisdom is utilized to extract insights with universally similar or identical semantics from data, integrating multiple independent data points into a coherent understanding that transcends individual cases. For example, in the healthcare field, long-term accumulated expertise and clinical experience can assist in identifying common disease patterns from various patient physiological indicators. This enables the formulation of reliable diagnoses and treatment plans based on these recognized patterns, providing a solid foundation for medical decision-making.

-

Principle 24: IntermediaryThe cognitive subject can employ wisdom-driven models or frameworks to analyze data, offering more refined and contextually relevant insights. For example, in social science research, psychological theoretical models can be applied to interpret survey results. By leveraging the value-driven processes inherent in wisdom, these models facilitate a deeper exploration of the motivations behind individual behaviors and the social factors that influence them. This approach allows for a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of complex human dynamics, enhancing the ability to generate meaningful and actionable conclusions [42].

-

Principle 25: Self-serviceWisdom can guide data collection and interpretation, enabling autonomous operations by the cognitive subject and reducing reliance on external guidance. This involves incorporating intelligent decision-making mechanisms into data processing. For instance, in intelligent traffic management systems, historical traffic flow patterns and emergency response experiences can be utilized to automatically adjust traffic signal control strategies, thereby optimizing traffic flow. This approach enhances system responsiveness and efficiency by enabling adaptive, self-regulating decision-making processes.

-

Principle 35: Parameter ChangesThe cognitive subject can adjust data parameters based on insights derived from wisdom to ensure that data collection and analysis methods support deeper understanding. For example, in environmental monitoring projects, working parameters of air quality monitoring equipment can be fine-tuned in response to a nuanced understanding of climate change trends, allowing for the capture of more critical environmental signals. This adaptive approach enhances the precision and relevance of the data collected, facilitating a more accurate analysis of complex environmental dynamics.

4.1.17. Wisdom (W) → Information (I)

-

Principle 16: Partial or Excessive ActionsThe cognitive subject can leverage wisdom to determine appropriate information processing methods, ensuring efficient resource allocation. This means that in handling information, it is crucial to apply measures that correspond to the level of semantic differentiation. For instance, in corporate strategy development, wisdom can guide which information requires in-depth exploration based on market trend analysis and which content only needs a high-level overview, thus preventing resource waste or information overload [43]. This approach optimizes the decision-making process by aligning the depth of information analysis with strategic priorities and resource availability.

-

Principle 22: Blessing in DisguiseLeveraging wisdom to identify the deeper meanings or hidden value within information semantics can transform potential problems into opportunities for insight. For example, when faced with negative customer feedback, a wise analysis might uncover new ways to improve products or services, turning challenges into a catalyst for innovation and enhancement. This proactive approach not only addresses immediate concerns but also contributes to long-term growth and development by converting setbacks into strategic advancements.

4.1.18. Wisdom (W) → Knowledge (K)

-

Principle 3: Local QualityThe cognitive subject transforms high-quality strategies derived from wise decision-making in a specific domain into specialized knowledge systems. For example, in healthcare management, wisdom-based medical decisions—such as strategies for responding to pandemics—are translated into structured knowledge systems for managing specific diseases. This may include knowledge of the allocation of medical resources and patient management tailored to infectious diseases, thereby enabling a more systematic and effective approach to healthcare administration and crisis response.

-

Principle 23: FeedbackUtilize experiential feedback to refine both knowledge and wisdom, enhancing understanding and decision-making abilities through the lessons learned from both successes and failures. This process emphasizes learning and reflection in practice, where continuous trial and error lead to the development of a more mature knowledge system and wise judgment. For instance, in corporate strategic planning, analyzing the outcomes of past decisions can help identify which strategies were effective and which need adjustment, thereby optimizing future strategic choices.

4.1.19. Wisdom (W) → Wisdom (W)

-

Principle 15: DynamismEnable wisdom to adapt and evolve with changing circumstances, ensuring its continued relevance and effectiveness in guiding decisions. This means that wisdom is not a static collection of knowledge but requires adjustment in response to changes in the external environment. For example, in business management, leaders should continuously adjust their management philosophies and strategies in response to market changes and competitive dynamics to maintain the company’s competitiveness. Through dynamic adjustment, wisdom can better address future uncertainties. Research has shown that businesses that adapt their strategies in response to competitive intensity and market dynamism tend to achieve better performance outcomes [44]. Similarly, a study on business model adaptation highlights how proactive adjustment to environmental threats can significantly improve business performance [45].

-

Principle 23: FeedbackUtilize results and experiences to continuously refine and enhance wisdom, forming a feedback loop that supports continuous improvement. This principle emphasizes the importance of experiential learning, drawing lessons from past successes and failures to optimize future decision-making. For instance, in medical practice, doctors can adjust treatment plans based on patient outcomes, using a continuous feedback mechanism to steadily improve the quality of care and treatment efficacy.

-

Principle 34: Discarding and RecoveringAbandon outdated or ineffective wisdom to make room for new insights, ensuring that wisdom remains a dynamic and flexible cognitive asset. This means being willing to let go of perspectives or methods that are no longer applicable while accumulating new knowledge. For example, in the technology field, as new technologies develop, old technical theories and practices may become obsolete, necessitating timely updates to professional knowledge and the discarding of outdated concepts and techniques.

4.1.20. Wisdom (W) → Purpose (P)

-

Principle 7: Nested DollEnsure that wisdom guides the setting of objectives at different levels, aligning strategic vision with operational goals. This means that at various levels of an organization, wisdom should serve as the foundation for objective setting. For example, at the corporate strategy level, senior management should set long-term development goals based on a deep understanding of industry trends and organizational strengths. At the departmental level, middle management should establish short-term work plans based on these long-term goals, ensuring coherence and alignment between upper and lower-level objectives.

-

Principle 10: Preliminary ActionBased on the strategic goals outlined in wisdom-based decision-making, action intentions and plans can be generated proactively. In corporate strategic management, for instance, long-term wisdom-driven decisions—such as global market forecasts—are used to formulate market entry strategies and objectives for the coming years. This forward-looking approach ensures that strategic actions are aligned with anticipated market trends and long-term organizational goals, enhancing the effectiveness and adaptability of the company’s strategic initiatives.

-

Principle 15: DynamismMaintain the flexibility and adaptability of objectives to incorporate evolving wisdom and insights. This means that objectives should be dynamic and continuously updated as new knowledge is accumulated. For example, in the field of education, as research on learning sciences deepens, educational goals should be revised accordingly to better support student development.

-

Principle 34: Discarding and RecoveringAdjust or redefine objectives based on new wisdom to maintain their relevance and effectiveness in a constantly changing environment. This principle emphasizes the dynamic adjustment of goals, suggesting that original objectives should be updated when new knowledge or experience emerges, allowing them to better align with the current context. For instance, in industries with rapid technological advancements, companies should adjust their research and development objectives according to the latest technological trends to maintain a competitive edge.

4.1.21. Purpose (P) → Data (D)

-

Principle 10: Preliminary ActionFuture data collection plans and requirements can be proactively generated based on the content of intentions to ensure that the data will meet the analytical needs of anticipated goals. In market analysis, for example, new data collection strategies can be developed in advance based on market expansion intentions, such as gathering information on emerging market trends and competitor activities. This approach ensures that data acquisition is strategically aligned with the expected objectives, facilitating more effective analysis and informed decision-making.

-

Principle 23: FeedbackBased on the feedback mechanisms of the intended goals, supplementary and optimized data can be generated to create datasets that more accurately align with the objectives. In user experience optimization, for instance, new data collection requirements can be derived from user feedback to capture additional user behavior information. This helps refine product design according to the intent of product improvements, ensuring that the data collected supports targeted enhancements and delivers a better user experience.

4.1.22. Purpose (P) → Information (I)

-

Principle 6: UniversalityPurposes can be transformed into various reusable standardized information templates, reflecting semantic differences through distinct, specific purposes. These templates can be adapted to suit different contexts and objectives, allowing for the effective communication of nuanced information semantics across diverse scenarios. This structured approach enhances the clarity and consistency of information dissemination while ensuring alignment with varying goals and situational requirements.

-

Principle 13: The Other Way AroundThe cognitive subject can utilize the differentiation of intentions to perform reverse reasoning and generate explanatory information semantics. In project management, for instance, reverse analysis of project objectives can produce informative content that explains decisions, such as why a specific project path was chosen or the rationale behind resource allocation strategies. This approach provides a clear and structured explanation of strategic choices, facilitating better understanding and communication of the underlying reasoning.

4.1.23. Purpose (P) → Knowledge (K)

-

Principle 2: Taking OutThe cognitive subject can extract the core goals and strategies from intentions to form independent knowledge modules. These modules, containing comprehensive semantics, can be used to guide future actions. In corporate management, for instance, the core strategic intentions for company growth can be structured into knowledge modules, such as market expansion strategies or brand development strategies, to support strategic implementation across various departments. This approach ensures that each department aligns its actions with the overarching strategic vision, facilitating coherent and coordinated organizational growth [46].

-

Principle 15: DynamismIn risk management, transforming dynamic risk assessment intentions into a real-time, adaptive risk management knowledge system is crucial. For instance, a large financial institution must navigate an ever-changing market environment and policy risks, such as macroeconomic fluctuations and international market uncertainties. Traditional static risk management strategies are no longer sufficient to meet the demands of rapidly evolving market conditions. It is essential to translate risk management intentions into a dynamic, continuously updated knowledge framework that can effectively respond to emerging risks and challenges.

4.1.24. Purpose (P) → Wisdom (W)

-

Principle 36: Phase TransitionsIn risk management, transforming dynamic risk assessment intentions into a real-time, adaptive risk management knowledge system is crucial. For instance, a large financial institution must navigate an ever-changing market environment and policy risks, such as macroeconomic fluctuations and international market uncertainties. Traditional static risk management strategies are no longer sufficient to meet the demands of rapidly evolving market conditions. It is essential to translate risk management intentions into a dynamic, continuously updated knowledge framework that can effectively respond to emerging risks and challenges [47,48].

-

Principle 40: Composite MaterialsWe have expanded the semantics of composite materials, transforming them into multidimensional objectives. The cognitive subject comprehensively considers the multidimensional goals embedded within the intentions—such as economic benefits and social responsibility—to generate wise decisions that balance the interests of all stakeholders. This holistic approach ensures that decision-making is aligned with diverse objectives, facilitating sustainable and ethically sound outcomes.

4.1.25. Purpose (P) → Purpose (P)

-

Principle 15: DynamismAllow intentions to evolve over time, adapting to new insights, goals, and environmental changes to maintain their effectiveness and relevance. This means that intentions should not be static but should be dynamically adjusted in response to internal and external changes. For example, in corporate strategic planning, as market trends shift and technological advancements occur, a company’s long-term development goals should be adjusted in a timely manner to ensure strategic foresight and adaptability.

-

Principle 25: Self-ServiceEnable intentions to self-adjust based on internal standards and changing needs, promoting flexibility and resilience in goal setting. This means that when setting intentions, a certain degree of autonomy should be granted within the organization, allowing for self-adjustment of goals according to actual circumstances. For instance, in project management, teams can flexibly adjust interim goals based on project progress and resource allocation to ensure smooth project execution.

-

Principle 34: Discarding and RecoveringPeriodically reassess and update intentions, discarding outdated goals and embracing new ones to adapt to changing environments. This requires organizations to be forward-looking in setting intentions, promptly eliminating goals that are no longer applicable, and introducing new goals to meet emerging challenges. For example, in the field of technological research and development, as new technologies emerge, companies should adjust their R&D direction in a timely manner, abandoning areas of technology that are no longer competitive and focusing on more promising research directions.

-

Principle 35: Parameter ChangesAdjust the parameters and standards of intentions as necessary to ensure alignment with overarching strategies and values. This means that when setting intentions, consideration should be given to their consistency with the overall strategy of the organization, and modifications should be made as needed to align with strategic adjustments. For example, in social service organizations, as societal needs change and service models evolve, service goals and standards should be adjusted accordingly to better meet the needs of service recipients.

4.1.26. Data (D) ↔ Knowledge (K) ↔ Data (D) (Bidirectional Loop)

-

Principle 15 DynamismEnable continuous adaptation in data collection and knowledge application to ensure that both elements can co-evolve. This means that data collection methods and strategies for applying knowledge should possess flexibility, capable of being adjusted according to changes in actual conditions. For example, in scientific research, as experimental data accumulates, hypotheses and theoretical models need to be continually refined to reflect the latest findings; the revised theoretical models can then inform the design of subsequent experiments, ensuring the relevance and effectiveness of data collection.

-

Principle 23: Self-ServiceEstablish a feedback loop between data and knowledge, utilizing insights from data to refine knowledge and vice versa. This implies that effective feedback mechanisms should be established during the processing of data and the application of knowledge to continuously optimize the relationship between data and knowledge. For instance, in medical diagnosis, real-time analysis of patient records can continually update diagnostic models, enhancing diagnostic accuracy; the updated models can then guide subsequent data collection, forming a virtuous cycle.

-

Principle 35: Parameter ChangesAdjust parameters in data collection and knowledge representation to optimize the flow of information and insights. This indicates that during the processing of data and the representation of knowledge, relevant parameters should be adjusted according to actual needs to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of information transmission. For example, in social media analysis, by adjusting the frequency of data scraping and the criteria for keyword filtering, one can better capture user behavior patterns; optimizing the representation of knowledge, such as using visualization tools to present analytical results, can more intuitively convey insights, supporting the decision-making process.

4.1.27. Information (I) ↔ Wisdom (W) ↔ Information (I) (Bidirectional Loop)

-

Principle 15 DynamismMaintain adaptability in information and wisdom so that they evolve with new contexts and challenges. This means that information and wisdom should possess flexibility, capable of being adjusted according to changes in the external environment. For instance, in business management, as the market environment evolves, enterprises should continually update their business models and strategic plans, using the latest market information to guide decisions and deepening managerial wisdom through accumulated experience.

-

Principle 25: Self-ServiceUtilize wisdom to refine the processing and interpretation of information, and use new information to update and deepen wisdom. This implies that during the processing of information, existing wisdom should be employed to guide the selection, analysis, and interpretation of information; simultaneously, new information should be used to test and enrich current wisdom. For example, in education, teachers can leverage their teaching experience and wisdom to design course content, while student feedback and new research findings can be utilized to continuously improve teaching methods and content, forming a closed loop of continuous improvement.

-

Principle 32: Color ChangesAlter the framework or presentation style of information and wisdom to gain new insights and enhance understanding. This suggests that during the processing of information and the dissemination of wisdom, different perspectives and methods should be adopted to display information, thereby helping people understand issues from multiple angles. For example, in policy formulation, complex policy backgrounds and influencing factors can be presented through storytelling or case studies, assisting policymakers in better grasping the core of the issue and making wiser decisions.

4.1.28. Knowledge (I) ↔ Information (I) ↔ Data (D) (Multi-Element Transformation)

-

Principle 15: DynamismDynamism Maintain flexibility throughout the transformation processes among all elements, enabling them to adapt and respond to new challenges and opportunities. This means that throughout the entire transformation process, data, information, and knowledge should have the ability to dynamically and be capable of timely modifications based on environmental changes and new discoveries. For example, in corporate strategic planning, as the market environment evolves, companies need to continuously update their methods of data collection, strategies for information processing, and ways of applying knowledge, to ensure the foresight and adaptability of their strategic plans.

-

Principle 24: IntermediaryIntermediary Use models or frameworks to connect data, information, and knowledge, facilitating a coherent flow of insights among the three. This means establishing an orderly bridge between data, information, and knowledge to ensure smooth and logical information transfer among them. For example, in the field of scientific research, researchers can use theoretical models to guide the collection and analysis of data, transforming raw data into useful information and further refining it into knowledge that supports decision-making. Additionally, these models can help validate existing knowledge, ensuring its applicability when faced with new data.

-

Principle 35: Parameter ChangesParameter Adjustment Adjust parameters among all elements to ensure consistency and coherence, optimizing the transformation process from data to knowledge. This implies that in every stage of data collection, information processing, and knowledge generation, the corresponding parameters should be adjusted according to actual needs to enhance the efficiency and quality of the transformation. For instance, in big data analysis, by adjusting algorithm parameters, the data processing workflow can be optimized to ensure the accuracy and reliability of information extraction; during the knowledge generation phase, the method of knowledge representation, such as using charts or visualization tools, can be adjusted to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of knowledge dissemination.

4.1.29. Wisdom (W) ↔ Knowledge (K) ↔ Purpose (P) (Multi-Element Transformation)

-

Principle 7: Nested DollNested Dolls Align wisdom, knowledge, and purpose across different levels, ensuring mutual support and enhancement among each element. This means establishing a hierarchical relationship among layers so that wisdom, knowledge, and purpose at each level can promote one another, forming a multilevel coordination system. For example, in organizational management, the wisdom of top-level leaders can guide middle managers in formulating concrete management knowledge, which in turn helps front-line employees better understand the organization’s purpose, thus creating a coherent execution chain from top to bottom.

-

Principle 15: DynamismDynamism Maintain adaptability and alignment across all elements, ensuring their effectiveness in responding to changing contexts and challenges. This means that during the transformation of wisdom, knowledge, and purpose, there should be flexibility to adjust according to changes in the external environment. For example, in corporate strategic planning, as the market environment evolves, the company’s purpose must be continually adjusted, prompting the enterprise to re-examine and update its knowledge base, thereby ensuring the realization of strategic goals.

-

Principle 23: FeedbackFeedback Utilize feedback from each element to refine and strengthen the others, creating a cycle of continuous improvement and alignment. This implies establishing effective feedback mechanisms among wisdom, knowledge, and purpose, ensuring dynamic balance through constant evaluation and adjustment. For instance, in the educational sector, teachers can adjust teaching strategies based on students’ learning feedback, thereby better-imparting knowledge; students, by acquiring new knowledge, can further deepen their understanding of learning objectives, thus forming a virtuous cycle [49,50].

4.1.30. Data (D) ↔ Purpose (P) ↔ Wisdom (W) ↔ Information (I) ↔ Knowledge (K) (Full Network Interaction)

-

Principle 15: DynamismDynamism Maintain flexibility throughout the network, allowing each element to evolve and develop in response to new challenges and opportunities. This means that during the transformation process of data, purpose, wisdom, information, and knowledge, there should be a dynamic adjustment capability, enabling them to adapt to changes in the external environment. For example, in technological innovation, with the emergence of new technologies, enterprises need to continuously update their data processing techniques, information analysis methods, knowledge management systems, and wisdom application strategies to ensure their leading position in competition.

-

Principle 23: FeedbackFeedback Implement feedback loops at multiple levels, using insights from each element to refine and enhance the overall cognitive process. This means establishing effective feedback mechanisms among data, purpose, wisdom, information, and knowledge, ensuring dynamic balance through constant evaluation and adjustment. For example, in the educational sector, teachers can adjust teaching methods based on student learning feedback, and students, by acquiring new knowledge, can deepen their understanding of learning objectives, thus forming a cycle of continuous improvement.

-

Principle 24: IntermediaryIntermediary Utilize integrative models and frameworks to facilitate interactions among all elements, ensuring the coherence and comprehensiveness of the cognitive process. This means establishing a systematic intermediary mechanism among data, purpose, wisdom, information, and knowledge to promote coordination and integration among these elements. For example, in intelligent decision support systems, a comprehensive analytical framework can be used to integrate data from diverse sources, converting this data into useful information, and then through knowledge management and the refinement of wisdom, support the final decision-making process.

-

Principle 35: Parameter ChangesParameter Adjustment Continuously adjusts parameters among all elements to maintain coherence and consistency, supporting effective communication and decision-making. This implies that in every stage of data processing, information analysis, knowledge generation, and wisdom application, the corresponding parameters should be adjusted according to actual needs to ensure coordination and optimization among the elements. For instance, in business operations, the frequency of data collection can be adjusted according to market changes, the focus of information processing can be adjusted according to business requirements, and the direction of knowledge application can be adjusted according to strategic goals, thereby achieving efficient overall operations.

-

Principle 40: Composite MaterialsComposite Materials Combine multiple principles and elements to create a robust and flexible cognitive framework supporting complex problem-solving and innovation. This implies that in the cognitive process, a variety of methods and tools should be integrated to form a multidimensional cognitive system. For example, in policy formulation, a comprehensive and systematic policy-making framework can be created by integrating data analysis, expert wisdom, historical information, and current purpose, supporting more scientific and effective decision-making.

4.2. Cognitive Space Coverage Completeness Analysis

5. Identifying Overlaps and Redundancies

5.1. Data (D) → Data (D)

- Principle 35: Parameter Changes and Principle 1: Segmentation: In the process of data segmentation, it is often necessary to segment data based on specific parameters such as time or region. This requirement overlaps with the role of the Parameter Changes principle, which involves adjusting data parameters to uncover new patterns. Both principles are inherently intertwined, as parameter adjustments are frequently utilized as a foundational step in the segmentation process to enable more effective and meaningful data partitioning. Consequently, the application of these two principles may lead to functional redundancy, particularly when parameter adjustments and segmentation are simultaneously employed to analyze data variations and extract novel insights.

5.2. Data (D) → Information (I)

- Principle 9: Preliminary Anti-Action and Principle 5: Merging: The Preliminary Anti-Action principle involves pre-processing data before integration, such as cleaning and removing noise to ensure data accuracy. The Merging principle, on the other hand, comes into play after data pre-processing, focusing on the integration of data from different sources to form a new information system. There is a functional overlap between these two principles, particularly in the sequential application of data processing and integration, where both principles may be employed simultaneously, potentially leading to redundancy in handling and combining data.

- Principle 17: Another Dimension and Principle 28: Mechanics Substitution: The Another Dimension principle refers to enhancing data representation by adding dimensions, such as multi-dimensional graphics or multi-level models, to generate more comprehensive information. The Mechanics Substitution principle, however, involves the use of algorithms and tools to automate the transformation of data into information. Both principles share a common objective in data presentation and information generation, particularly in the utilization of tools and models to achieve this goal. The overlap arises when both principles are applied in the context of automated information generation and data representation.

- Principle 3: Local Quality and Principle 9: Preliminary Anti-Action: Both the Local Quality principle and the Preliminary Anti-Action principle involve deep optimization or pre-processing of specific data segments during the initial data handling phase. The overlap occurs in the data refinement stage, where both principles may be applied concurrently, leading to redundant processes, especially when multiple rounds of data processing are required. This repetition can result in unnecessary duplication of efforts, impacting overall efficiency.

5.3. Data (D) ← Purpose (P)

- Principle 11: Beforehand Cushioning and Principle 15: Dynamism: Both the Beforehand Cushioning and Dynamics principles involve adjustments in the process of achieving objectives based on situational changes. However, Beforehand Cushioning emphasizes proactive preparation to mitigate potential disruptions, whereas Dynamics focuses on real-time adaptation to evolving conditions. Despite their differing focal points—preventive versus reactive—both principles aim to ensure stability and continuity in the achievement of goals. Their concurrent application may result in overlapping actions, where both proactive measures and real-time adaptations are employed, potentially leading to an overcomplicated strategy for managing changes.

- Principle 15: Dynamism and Principle 35: Parameter Changes: The Dynamics principle pertains to the holistic adjustment of strategies aimed at achieving objectives, whereas the Parameter Changes principle focuses on the modification of specific data parameters. Both principles converge in the areas of goal adaptation and parameter optimization. This overlap suggests that while the Dynamics principle provides a broad framework for strategic realignment, the Parameter Changes principle offers granular adjustments to fine-tune the process. Consequently, their simultaneous application can lead to redundant efforts in strategy and parameter optimization, potentially complicating the systematic approach to reaching desired outcomes.

5.4. Information (I) → Information (I)

- Principle 17: Another Dimension and Principle 14: Spheroidality: Both the Another Dimension principle and the Spheroidality principle are concerned with multi-dimensional information representation, such as using various combinations of graphical models to reveal deeper meanings within the data. These principles intersect in their shared goal of enhancing the diversity and complexity of information presentation. By leveraging different dimensions and spherical representations, they aim to present data in a manner that facilitates a more comprehensive understanding. This overlap may result in redundancy when both principles are applied concurrently to achieve multi-dimensional visualization and interpretation.

- Principle 17: Another Dimension and Principle 35: Parameter Changes: The Another Dimension principle involves representing information across multiple dimensions, while the Parameter Changes principle focuses on adjusting the depth and breadth of the information being presented. Both principles share common ground in their influence on the manner in which information is expressed and communicated. They aim to modify and optimize the presentation format, whether through dimensional expansion or parameter adjustments, which can lead to redundancy when used simultaneously to alter the expression of information.

- Principle 13: The Other Way Round and Principle 35: Parameter Changes: The Other Way Round principle generates new semantic information through reverse reasoning, while the Parameter Changes principle creates new information semantics by altering the parameters of expression. Both principles, though distinct in their approaches—one leveraging reverse logic and the other modifying expression parameters—share a common objective of producing new information by modifying the way it is expressed. This convergence may lead to overlapping methodologies in the generation of novel information semantics, where both reverse reasoning and parameter adjustments are employed simultaneously.

5.5. Information (I) → Wisdom (W)

- Principle 23: Feedback and Principle 25: Self-Service: Both the Another Dimension principle and the Spheroidality principle are concerned with multi-dimensional information representation, such as using various combinations of graphical models to reveal deeper meanings within the data. These principles intersect in their shared goal of enhancing the diversity and complexity of information presentation. By leveraging different dimensions and spherical representations, they aim to present data in a manner that facilitates a more comprehensive understanding. This overlap may result in redundancy when both principles are applied concurrently to achieve multi-dimensional visualization and interpretation.

- Principle 15: Dynamism and Principle 32: Color Changes: The Color Changes principle and the Dynamism principle are both concerned with presenting information and wisdom from varied perspectives and methodologies. While the Color Changes principle prioritizes altering the modes of expression, such as visual modifications or alternative representations, the Dynamism principle places greater emphasis on dynamically adjusting the content and strategies of wisdom to adapt to evolving circumstances. Their convergence lies in the shared objective of enhancing the adaptability and efficacy of information communication through modifications in both form and substance.

- Principle 15: Dynamism and Principle 23: Feedback: Both the Feedback principle and the Dynamism principle involve the adaptation of wisdom strategies and information dissemination based on environmental changes and feedback. The Feedback principle emphasizes a cyclical process of receiving and incorporating external inputs to refine wisdom, whereas the Dynamism principle is more focused on internal flexibility, allowing for real-time strategic adjustments. Despite these differences, both principles are fundamentally aligned in their aim to optimize responses to fluctuating conditions, either through external information integration or internal strategic recalibration

5.6. Knowledge (K) → Knowledge (K)

- Principle 22: Blessing in Disguise and Principle 23: Feedback: Both the Blessing in Disguise principle and the Feedback principle are centered around the process of optimizing the knowledge system and application strategies through challenges or feedback in the course of knowledge utilization. The Blessing in Disguise principle emphasizes discovering new opportunities amid challenges or adversity, effectively turning obstacles into learning moments. On the other hand, the Feedback principle focuses on the integration of external feedback to improve and refine existing knowledge systems. Although their approaches differ, both principles converge in their aim to enhance the application of knowledge by responding to external influences, either through adversity or feedback mechanisms.

5.7. Knowledge (K) → Purpose (P)

- Principle 31: Porous Materials and Principle 35: Parameter Changes: Porous Materials principle and the Parameter Changes principle underscore the importance of flexibility and adaptability in goal-setting. The Porous Materials principle focuses on maintaining an openness to new knowledge and insights, allowing objectives to be permeable and receptive to novel information. In contrast, the Parameter Changes principle emphasizes the dynamic optimization of goals through the adjustment of various parameters, enabling the refinement and recalibration of objectives based on changing conditions. Despite their distinct focal points, both principles advocate for a responsive and evolving approach to achieving desired outcomes, thereby enhancing the robustness and resilience of strategic goal management.

5.8. Wisdom (W) → Wisdom (W)

- Principle 15: Dynamism and Principle 23: Feedback: Both the Dynamics principle and the Feedback principle play pivotal roles in the continual refinement of wisdom transformation, emphasizing the iterative process of decision-making optimization in response to environmental changes and experiential feedback. The Dynamics principle is concerned with the adaptive nature of wisdom, focusing on its capacity to respond flexibly to evolving circumstances. In contrast, the Feedback principle places a greater emphasis on reflecting upon and incorporating lessons learned from past experiences to drive improvements. Although they address distinct aspects of the transformation process, both principles advocate for a dynamic and reflective approach to decision-making that enhances the adaptability and resilience of wisdom.

- Principle 23: Feedback and Principle 34: Discarding and Recovering: The Feedback principle and the Discarding and Recovering principle both address self-improvement and renewal within the process of wisdom transformation. The Feedback principle seeks to enhance wisdom by learning from past experiences and integrating these insights into the decision-making process. Conversely, the Discarding and Recovering principle focuses on the deliberate abandonment of outdated wisdom to make room for new perspectives and insights. Both principles, despite their different methodologies, converge in their shared objective of fostering continuous evolution and renewal of wisdom, ensuring that outdated or ineffective approaches are replaced by more relevant and innovative ones.

- Principle 15: Dynamism and Principle 34: Discarding and Recovering: The Dynamics principle and the Discarding and Recovering principle are essential components in the adaptation and evolution of wisdom in reaction to varying external conditions. The Dynamics principle underscores the necessity for wisdom to remain agile and responsive to environmental transformations, enabling strategic modifications that align with emergent realities. On the contrary, the Discarding and Recovering principle emphasizes the significance of jettisoning ineffective or obsolete wisdom to pave the way for more efficacious strategies. Collectively, these principles highlight the requirement for a proactive stance in wisdom management, wherein the ability to adapt and the readiness to discard outdated frameworks synergistically optimize the transformation process.

5.9. Wisdom (W) → Purpose (P)

- Principle 15: Dynamism and Principle 23: Feedback: Both the Dynamics principle and the Feedback principle play pivotal roles in the continual refinement of wisdom transformation, emphasizing the iterative process of decision-making optimization in response to environmental changes and experiential feedback. The Dynamics principle is concerned with the adaptive nature of wisdom, focusing on its capacity to respond flexibly to evolving circumstances. In contrast, the Feedback principle places a greater emphasis on reflecting upon and incorporating lessons learned from past experiences to drive improvements. Although they address distinct aspects of the transformation process, both principles advocate for a dynamic and reflective approach to decision-making that enhances the adaptability and resilience of wisdom.

- Principle 23: Feedback and Principle 34: Discarding and Recovering: The Feedback principle and the Discarding and Recovering principle both address self-improvement and renewal within the process of wisdom transformation. The Feedback principle seeks to enhance wisdom by learning from past experiences and integrating these insights into the decision-making process. Conversely, the Discarding and Recovering principle focuses on the deliberate abandonment of outdated wisdom to make room for new perspectives and insights. Both principles, despite their different methodologies, converge in their shared objective of fostering continuous evolution and renewal of wisdom, ensuring that outdated or ineffective approaches are replaced by more relevant and innovative ones.

- Principle 15: Dynamism and Principle 34: Discarding and Recovering: The Dynamics principle and the Discarding and Recovering principle are essential components in the adaptation and evolution of wisdom in reaction to varying external conditions. The Dynamics principle underscores the necessity for wisdom to remain agile and responsive to environmental transformations, enabling strategic modifications that align with emergent realities. On the contrary, the Discarding and Recovering principle emphasizes the significance of jettisoning ineffective or obsolete wisdom to pave the way for more efficacious strategies. Collectively, these principles highlight the requirement for a proactive stance in wisdom management, wherein the ability to adapt and the readiness to discard outdated frameworks synergistically optimize the transformation process.

5.10. Purpose (P) → Data (D)

- Principle 10: Preliminary Action and Principle 35: Parameter Changes: The Preliminary Action principle and the Parameter Changes principle both emphasize the importance of preemptive adjustments and preparations prior to data collection or analysis to ensure the validity of data and the precision of subsequent analyses. The Preliminary Action principle focuses on data preprocessing activities, such as cleaning and organizing data to establish a solid foundation for further exploration. Conversely, the Parameter Changes principle involves fine-tuning analytical parameters based on specific objectives to optimize the alignment of analytical strategies with desired outcomes. Despite their distinct areas of emphasis—data preparation versus parameter adjustment—both principles aim to enhance the effectiveness and accuracy of data-driven processes through proactive planning and systematic adjustments.

5.11. Purpose (P) → Purpose (P)

- Principle 15: Dynamism and Principle 34: Discarding and Recovering: Both the Dynamics principle and the Discarding and Recovering principle are concerned with maintaining the relevance and adaptability of goals through continuous revision and adjustment. The Dynamics principle focuses on the dynamic modification of objectives, ensuring they remain aligned with evolving conditions. On the other hand, the Discarding and Recovering principle emphasizes the need to replace outdated goals with new ones to better adapt to changing circumstances. Although their approaches differ, both principles highlight the importance of goal flexibility, either through ongoing adjustment or through the strategic abandonment of obsolete targets in favor of more suitable ones.

- Principle 25: Self-Service and Principle 34: Discarding and Recovering: The Self-Service principle and the Discarding and Recovering principle both emphasize enhancing goal adaptability and flexibility through internal self-regulation and goal updating during the goal-setting process. The Self-Service principle underscores the autonomous capacity for self-regulation, allowing goals to adjust themselves in response to internal needs and external conditions. Conversely, the Discarding and Recovering principle advocates for regular evaluation and revision of goals, promoting adaptability by systematically discarding outdated objectives and incorporating new ones. Both principles, through distinct mechanisms, contribute to the continuous evolution and optimization of goals, ensuring they remain relevant and effective in a dynamic environment.

6. DIKWP-TRIZ versus TRIZ

6.1. Traditional Framework of TRIZ and Its Limitations

6.2. Innovations and Advantages of DIKWP-TRIZ

6.2.1. Purpose and Ethical Considerations

6.2.2. Problem-Solving Capabilities in a Multidimensional Cognitive Framework

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Ilevbare, I.M.; Probert, D.; Phaal, R. A review of TRIZ, and its benefits and challenges in practice. Technovation 2013, 33, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, K.H.; Zhang, J.; Tan, K.C. A TRIZ-Based Method for New Service Design. Journal of Service Research 2005, 8, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Duan, Y. Modeling and Resolving Uncertainty in DIKWP Model. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y. Existence Computation: Revelation on Entity vs. Relationship for Relationship Defined Everything of Semantics. 2019 20th IEEE/ACIS International Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking and Parallel/Distributed Computing (SNPD), 2019, pp. 139–144. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Shao, L.; Hu, G. Specifying Knowledge Graph with Data Graph, Information Graph, Knowledge Graph, and Wisdom Graph. International Journal of Software Innovation, 6, 10–25. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, X.; Wu, J. Data privacy protection for edge computing of smart city in a DIKW architecture. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2019, 81, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Duan, Y. The DIKWP (Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom, Purpose) Revolution: A New Horizon in Medical Dispute Resolution. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.B.; Song, Y.W.; Kim, S.B.; Lee, K.H.; Hu, J.H. Considerations on the Smart Factory and the Use of TRIZ 40 Inventive Principles: Focusing on Site Improvements in the Field of Semiconductor Industry. Asia-pacific Journal of Convergent Research Interchange. [CrossRef]

- Reusch, P.J.A.; Zadnepryanets, M. TRIZ 40 inventive principles application in project management. 2015 IEEE 8th International Conference on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems: Technology and Applications (IDAACS), 2015, Vol. 2, pp. 521–526. [CrossRef]

- Kretzschmar, N.; Chekurov, S. The applicability of the 40 TRIZ principles in design for additive manufacturing. Proceedings of the 29th DAAAM International Symposium; Katalinic, B., Ed. DAAAM International, 2018, number 1 in Annals of DAAAM and proceedings, pp. 888–893. International DAAAM Symposium on Intelligent Manufacturing and Automation, DAAAM; Conference date:24-10-2018 Through 27-10-2018. [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, H. Method for Transferring the 40 Inventive Principles to Information Technology and Software. Procedia Engineering 2015, 131, 993–1001, TRIZ and Knowledge-Based Innovationin Science and Industry. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livotov, P.; Chandra Sekaran, A.P. ; Mas’udah. Lower Abstraction Level of TRIZ Inventive Principles Improves Ideation Productivity of Engineering Students. New Opportunities for Innovation Breakthroughs for Developing Countries and Emerging Economies; Benmoussa, R., De Guio, R., Dubois, S., Koziołek, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 526–538. [Google Scholar]

- Gazem, N.; Rahman, A.A. Improving TRIZ 40 Inventive Principles Grouping in Redesign Service Approaches. Asian Social Science 2014, 10, 127–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Tan, R.; Wang, C.; Li, Z. Computer-aided classification. of patents oriented to TRIZ. 2009 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Zanni-Merk, C.; Cavallucci, D.; Collet, P. An ontology-based approach for inventive problem solving. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2014, 27, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Liu, H.; Zanni-Merk, C.; Cavallucci, D. IngeniousTRIZ: An automatic ontology-based system for solving inventive problems. Knowledge-Based Systems 2015, 75, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; neng Chen, W.; Gu, T.; Zhang, H.; Deng, J.D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Segment-Based Predominant Learning Swarm Optimizer for Large-Scale Optimization. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2017, 47, 2896–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Kerr, B.; Dontcheva, M.; Grover, J.; Hoffman, M.; Wilson, A. CoreFlow: Extracting and Visualizing Branching Patterns from Event Sequences. Computer Graphics Forum 2017, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.; Galas, D.; Galitski, T. Maximal Extraction of Biological Information from Genetic Interaction Data. PLoS Computational Biology 2009, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrel-Samuels, P.; Francis, E.; Shucard, S. Merged Datasets: An Analytic Tool for Evidence-Based Management. California Management Review 2009, 52, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]