1. Introduction. The State of the Art on Cognition and Intelligence

Cognition and intelligence are two central yet still poorly understood concepts across multiple disciplines, including philosophy, psychology, biology, medicine, and artificial intelligence. Despite their ubiquitous presence in discussions of education, neuroscience, and technology, these concepts suffer from definitional ambiguity that reflects traditional, human-centered perspectives largely uninformed by recent advances in biology, embodied cognition, enactivism, anticipatory systems, philosophy of cognition, and information studies. Contemporary dictionary entries and encyclopedic sources perpetuate this narrow understanding, failing to capture the theoretical complexity and empirical breadth that characterize current scientific discourse.

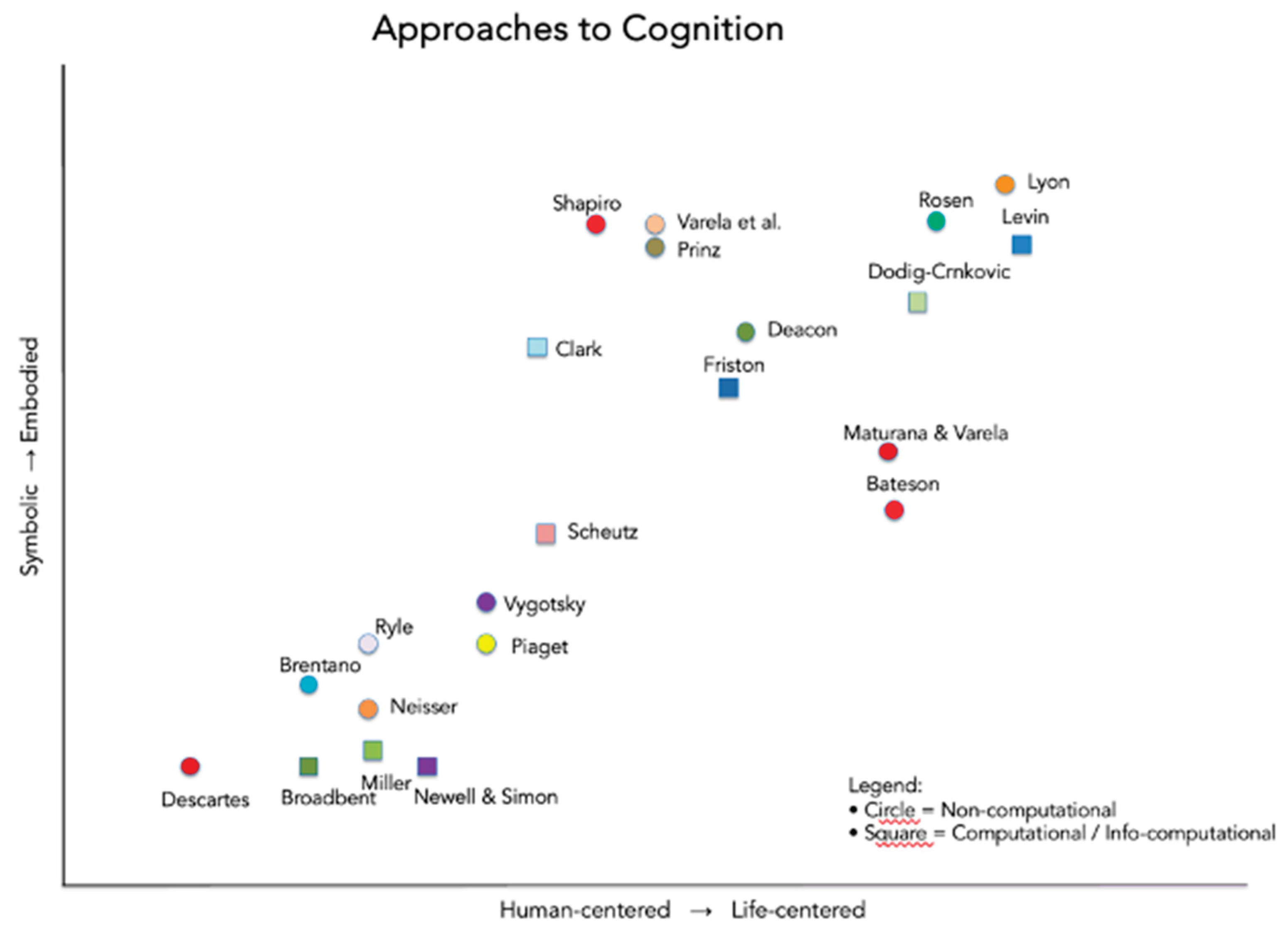

The conceptual landscape of cognition and intelligence can be effectively organized around two fundamental dividing lines that illuminate the theoretical tensions within the field. The first distinction separates mentalist approaches from embodied cognition frameworks, while the second differentiates human-centered perspectives from life-centered alternatives. These theoretical divisions provide essential scaffolding for understanding how different research traditions have approached the fundamental questions of what constitutes cognitive activity and intelligent behavior.

1.1. Mentalism Versus Embodied Cognition

The mentalist tradition, encompassing both classical philosophy of mind and symbolic information-processing psychology, equates cognition with conscious thought or disembodied symbol manipulation. Representative definitions reflect this perspective, characterizing cognition as “the use of conscious mental processes”1 or “the broad set of mental processes that relate to acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses.”2 Such formulations focus on abstract mental operations while minimizing the role of physical embodiment in cognitive processes.

Embodied approaches fundamentally challenge these mentalist assumptions by arguing that cognition emerges through the dynamic interaction of brain, body, and environment, resisting reduction to abstract mental states. As articulated by (Foglia & Wilson, 2013), “Proponents of the view known as ‘embodied cognition’ emphasize the role of sensory and motor functions in cognition itself. By viewing the mind as grounded in the details of its sensory-motor embodiment, they model cognitive skills as the product of a dynamic interplay between neural and non-neural processes”. This perspective repositions cognition as an inherently physical and situated phenomenon rather than an abstract disembodied process.

1.2. Human-Centered Versus Life-Centered Perspectives

Most mainstream accounts, regardless of their position on the mentalism-embodiment spectrum, maintain human-centered assumptions that restrict cognition to human minds or, at most, extend it to other animals possessing nervous systems. This anthropocentric bias limits theoretical scope and empirical investigation to a narrow range of cognitive phenomena associated with complex neural architectures.

The life-centered tradition offers a radical alternative by conceptualizing cognition as intrinsic to life itself, extending cognitive processes to all living systems from single cells to complex multicellular organisms. This perspective fundamentally expands the taxonomic and organizational scope of cognitive science, challenging basic assumptions about the minimal requirements for cognitive activity and the relationship between life and mind.

Table 1.

Human-centered vs. Life-centered Approaches to Cognition and Intelligence.

Table 1.

Human-centered vs. Life-centered Approaches to Cognition and Intelligence.

| Dimension |

Human-centered approach |

Life-centered approach |

| Scope |

Cognition = human mental processes;

Intelligence = subset of those processes. |

Cognition = life itself;

Intelligence = life’s competency in solving problems across scales. |

| Nature of cognitive process |

Cognition as a mental process (thinking, reasoning, memory, etc.). |

Cognition as a somatic process (self-maintenance, sensorimotor coordination, anticipation, sense-making). |

| Environment and coupling |

Emphasis on internal mental processes, Extended/enactive views consider environment. |

Always relational — cognition = organism–environment coupling. |

| Cognition vs. Intelligence |

Cognition = set of mental processes; Intelligence = specific capacities (reasoning, problem-solving, learning). |

Cognition = ongoing life process; Intelligence = competency of that process under novelty, perturbation, and uncertainty. |

1.3. Historical Development of Human-Centered Perspectives

The intellectual history of cognition and intelligence within human-centered traditions reveals three major developmental phases, each representing distinct theoretical commitments and methodological approaches that have shaped contemporary understanding.

Classical mentalism emerged from philosophical traditions that identified cognition with thinking and reasoning within mind-body dualistic frameworks. This approach treated mind and body as fundamentally distinct substances, the mind as non-physical and the body as physical, with cognition representing mental activity closely tied to conscious thought. Philosophical contributors including Descartes, Brentano, and early analytic thinkers established cognition as a defining characteristic of rational human minds, creating an explicitly anthropocentric foundation for subsequent theoretical developments.

The mid-20th century witnessed a paradigmatic shift through the “cognitive revolution” in psychology and artificial intelligence, which reframed cognition as symbol manipulation and abstract information processing. This transformation integrated Turing’s computational concepts, problem-solving models, and systematic psychological frameworks to define mind as a symbolic information-processing system (Newell & Simon, 1972; Neisser, 1967). While maintaining human-centered assumptions, this computational metaphor replaced consciousness-based explanations with mechanistic models of mind as software operating on neural hardware.

Contemporary developments from the 1990s onward have challenged disembodied computational models through embodied, enactive, and extended cognition frameworks. These approaches argue that cognitive processes cannot be understood independently of their physical implementation and environmental context. Foundational contributions established cognition as necessarily embodied, embedded, enactive, and extended—known as 4E cognition (Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 1991; Clark, 1997; Shapiro, 2011/2019; Newen, De Bruin, & Gallagher, 2018). This perspective emphasizes that cognitive processes emerge through situated bodily interactions and environmental contexts, fundamentally challenging earlier mentalist assumptions (Prinz, 2004; Scheutz, 2002; Pfeifer & Bongard, 2006). Within 4E frameworks, intelligence transcends abstract problem-solving capacity to encompass flexible coordination of body, brain, and environment for goal achievement.

1.4. The Life-Centered Perspectives

In distinction to human-centered theoretical developments, life-centered approaches have emerged that fundamentally reconceptualize the scope and nature of cognitive phenomena. Rather than restricting cognition to humans or organisms with nervous systems, this tradition identifies cognition with life processes themselves. The fundamental insight that “Living systems are cognitive systems and living as a process is a process of cognition” (Maturana & Varela, 1980) establishes cognitive activity as coextensive with biological organization.

Multiple theoretical contributions have developed this basic insight by emphasizing anticipation, sense-making, and problem-solving as fundamental features of living systems (Rosen, 1985/2012; Bateson, 1979; Levin, 2019; Lyon, 2006). Within this framework, cognition represents the process of life itself, while intelligence manifests as the competency of living systems to solve problems under conditions of novelty and uncertainty.

While human-centric cognition has been characterized as “a collection of processes such as perception, memory, learning, decision-making, problem-solving, goal-directedness, attention, anticipation, communication, and maybe emotion,” evolutionary perspectives describe cognition as “the set of informational and dynamic processes an organism interacts with to grasp aspects of its world” (Just & Torres de Farias, 2024). These perspectives develop largely independently, with human-centered approaches prevailing mainstream psychology, philosophy of mind and public understanding whereas life-centered approaches dominating within biology, cybernetics, artificial life, and systems theory.

The consequences of this theoretical divergence extend far beyond academic discourse, fundamentally shaping interpretations of life and mind while influencing conceptualizations of intelligence in an era increasingly defined by cognitive and intelligent technologies. Life-centered cognition receives precise articulation in contemporary biological frameworks: “Cognition is comprised of sensory and other information processing mechanisms an organism has for becoming familiar with, valuing, and interacting productively with features of its environment in order to meet existential needs, the most basic of which are survival/persistence, growth/thriving, and reproduction” (Lyon, 2021). This definition establishes cognition as fundamentally biological while providing criteria for identifying cognitive processes across the full spectrum of living systems.

2. Cognition and Intelligence in the Human-Centered Perspective

In psychology and philosophy of mind, cognition is defined as the set of mental processes—perception, memory, reasoning, language, problem-solving—through which humans acquire and use knowledge (Neisser, 1967; APA, 2023; Eysenck & Brysbaert, 2023). Intelligence is typically understood as a subset of these processes, specifically the ability to reason, solve problems, learn, and adapt effectively. The theoretical understanding of these constructs has evolved through several distinct research traditions, each contributing fundamental insights to our current conceptualization.

The developmental approach emerged through systematic investigation of cognitive development, characterizing cognition as a developmental process of adaptation in humans operating through two complementary mechanisms: assimilation and accommodation. Within this framework, intelligence represents the capacity to adapt to the environment by effectively balancing these two processes (Piaget, 1952/1970). This perspective established cognition as fundamentally developmental and adaptive, laying groundwork for subsequent theories that would emphasize the dynamic nature of mental processes.

Building upon developmental foundations, the socio-cultural dimension introduced essential challenges to individualistic approaches. This tradition proposed that cognition develops through the internalization of social interaction, reshaping understanding of mental processes as inherently social phenomena. Intelligence, within this theoretical framework, constitutes the ability to use cultural tools, particularly language, to regulate thought and action (Vygotsky, 1978). This contribution established the essential role of social context in cognitive development and functioning, demonstrating that mental processes cannot be fully understood in isolation from cultural and interpersonal contexts.

The psychometric tradition represented a methodological shift toward quantitative measurement of cognitive abilities, developing comprehensive models of human intelligence based on factor analysis and standardized testing protocols. This approach operationalized intelligence as quantitative measures derived from IQ testing, total scores obtained from standardized test batteries, while positioning cognition as the broader domain encompassing all mental processes (Carroll, 1993; Sternberg, 1985). These psychometric applications provided empirical methods for assessing individual differences in cognitive abilities and established frameworks for understanding the structure of human intelligence.

The information processing paradigm introduced computational metaphors that fundamentally altered cognitive science. This approach characterized human cognition as symbolic information processing occurring within formal problem spaces, conceptualizing intelligence as efficient problem-solving capacity utilizing symbolic computation and explicitly using computational models (Newell & Simon, 1972). The computational framework established formal methods for analyzing cognitive processes and problem-solving strategies, providing precise theoretical tools for understanding mental operations.

Contemporary cognitive science has witnessed significant theoretical expansion through distributed cognition frameworks that challenge traditional computational approaches. Initial developments introduced microcognition, arguing that cognitive capacities emerge from distributed, sub-symbolic processes such as connectionist networks, rather than exclusively from symbolic rule-based reasoning (Clark, 1989). This perspective evolved into the Extended Mind Hypothesis, proposing that cognition extends beyond individual minds into the body and environment through tools and artifacts (Clark & Chalmers, 1998). Recent theoretical integration incorporates predictive processing, describing cognition as the brain’s systematic attempt to minimize prediction errors through environmental interaction (Clark, 2013). Within this framework, cognition is conceptualized as distributed and embodied, while intelligence represents the capacity to flexibly integrate micro-level processes, bodily resources, and environmental supports for problem-solving.

This theoretical progression has culminated in perspectives that extend cognition beyond traditional boundaries of the human mind and brain, incorporating environmental elements that perform cognitive functions such as memory extension and computation. Contemporary approaches thus dissolve the conventional boundary between human cognition and the surrounding environment, proposing that cognitive functions are distributed throughout broader ecological systems. This represents a fundamental shift from individualistic models toward understanding cognition as an emergent property of human-environment interaction systems, establishing the foundation for even more radical reconceptualizations of cognitive processes.

3. Life-Centered Perspectives to Cognition and Intelligence

The life-centered tradition fundamentally redefines cognition and intelligence by grounding these phenomena in the basic processes of living systems themselves. This theoretical shift moves beyond brain-centric models to examine cognitive processes as intrinsic properties of life, establishing cognition not as an emergent property of complex neural networks but as a fundamental characteristic of processes in biological organization.

This radical departure from conventional cognitive science emerged from the recognition that living systems exhibit sophisticated adaptive behaviors across all scales of biological organization. As first proposed by Maturana and Varela (1980), cognition in biological systems is inseparable from the self-organizing processes that constitute life itself. Intelligence, within this framework, represents higher-order capacities such as language or symbolic reasoning that build upon this fundamental cognitive substrate inherent in all living systems.

The ecological dimension of this approach emphasizes cognition as pattern recognition and utilization within broader environmental contexts. Rather than viewing minds as isolated symbolic information processors, this perspective conceptualizes cognition as the basic capacity of a system to recognize, analyze, and organize differences in order to create knowledge and comprehend its environment. Bateson (1979) argued against the separation of mind and body, suggesting that the same fundamental patterns of interaction and relationship govern both natural systems and human cognition. Cognition, in this view, is not an isolated internal process but an emergent property of systems that are interconnected with their environment, “the pattern that connects” (Bateson, 1979). According to him, the “mind” is a machine that computes and contrasts these variations, therefore it applies not only to people but also to any biological or other system that has the ability of perception. Through a cybernetic understanding of systems and information, this constructivist process entails the detection of differences that make a difference and the creative adaptation of these patterns to novel circumstances (Mella, 2020). Intelligence emerges through flexible, creative responses that leverage these relational patterns across varying environmental conditions.

Essential to this life-centered understanding is the recognition that living systems are inherently anticipatory. The capacity to construct models of both self and environment enables organisms to predict future states and guide adaptive action accordingly (Rosen, 1985/2012). This anticipatory modeling represents a form of cognition that extends far beyond reactive stimulus-response mechanisms, incorporating predictive elements that enhance survival and adaptation across diverse biological contexts.

The reflexive nature of biological cognition introduces additional complexity through self-referential processes. Living systems not only process environmental information but also monitor and modify their own cognitive operations, creating recursive feedback loops that enable adaptive reorganization (von Foerster, 2003). This second-order cybernetic capacity allows organisms to adapt not merely to environmental changes but to their own changing cognitive states and capabilities.

Semiotic processes provide another crucial dimension to biological cognition. The processing of iconic, indexical, and symbolic signs occurs across multiple levels of biological organization, from basic cellular signaling to complex symbolic reasoning (Deacon, 1997; 2012). While symbolic reference reaches its highest expression in human cognition, the underlying semiotic processes are present throughout living systems, creating a hierarchical understanding of cognitive complexity that spans from simple organisms to complex social systems.

Contemporary mathematical and computational frameworks have formalized these insights through the Free Energy Principle and Active Inference (Friston, 2010). This approach characterizes cognition as the ongoing attempt of living systems to minimize surprise through continuous environmental modeling and active engagement. Intelligence manifests as the competency with which systems maintain homeostasis and viability under uncertain conditions, providing quantitative measures for cognitive effectiveness across biological scales.

The scope of life-centric approach extends cognition to organisms traditionally considered non-cognitive. Bacterial colonies, slime molds, and other basal organisms demonstrate sophisticated problem-solving capacities without nervous systems (Lyon, 2006, 2020). These findings challenge neurocentric assumptions and establish cognition as a general property of living systems, with intelligence reflected in behavioral flexibility and adaptive resilience.

Scale-invariance represents a particularly significant aspect of life-centered cognition. The capacity to navigate abstract state-spaces of possible configurations operates across cellular, tissue, organ, and organism levels (Levin, 2019; Levin & Dennett, 2021). Individual cells exhibit goal-directed behavior, tissues coordinate collective actions, and organisms pursue complex objectives—all demonstrating cognitive processes that transcend traditional boundaries between different levels of biological organization.

Empirical evidence strongly supports these theoretical propositions. Slime molds (Physarum polycephalum) solve complex spatial problems and anticipate periodic environmental changes despite lacking neural structures (Vallverdú et al., 2018). Bacterial communities engage in collective decision-making through quorum sensing, coordinating metabolic transitions based on population dynamics (Ben-Jacob, 2009). Planarian regeneration demonstrates how cellular systems maintain morphological memories and reconstruct complex body plans following injury. These examples illustrate cognition as a distributed property of living matter rather than a specialized function of nervous systems.

This convergent body of work establishes a fundamental equivalence: cognition represents the basic process of life itself—the maintenance and adaptation of living systems—while intelligence measures the competency with which these processes achieve goals under varying conditions. Rather than viewing cognition and intelligence as sophisticated emergent properties of complex brains, the life-centered tradition reveals them as fundamental characteristics of biological organization, present wherever life itself exists.

4. Comparative Analysis

In the human-centered view, cognition is restricted to the workings of the human mind, and intelligence is treated as a measure of specific mental abilities. In the life-centered view, cognition is understood as coextensive with life itself and an organism’s way of maintaining itself, interacting with its environment, and making sense of the world. Intelligence then is the competency of this ongoing process to cope flexibly with change and uncertainty. The implications are significant: in the first view, cognition is an exclusively human or at most brain-based phenomenon, while in the second it is a property of all living systems, from single cells to humans. There are also approaches which bridge the two, such as Andy Clark’s (2013) and Just & Torres de Farias (2024). The following table summarizes comparison between different approaches.

Figure 1.

(Symbolic → Embodied) vs. (Human-centered → Life-centered) approaches.

Figure 1.

(Symbolic → Embodied) vs. (Human-centered → Life-centered) approaches.

The above Figure presents the visualization of the

Table 2.

5. New Computationalism: Information Processing and Natural Computation Approaches

In the development of artificial intelligence and cognitive science, computation has played a central role. Classical cognitive science defined cognition as symbolic information processing, modeled after digital computation. Cognition was seen as a sequence of rule-governed operations on representations. This model has been criticized for its reliance on pre-defined symbols and rules and for its inability to account for the dynamic, context-sensitive, and embodied nature of cognition (Clark, 1997; Varela et al., 1991; Shapiro, 2019).

In recent years, a new understanding of computation has emerged, which redefines the relation between computation and cognition. Instead of treating computation as symbol manipulation in a Turing machine, the new computationalism defines computation as a form of information processing that can take place in a wide variety of physical, biological, and artificial systems (Dodig-Crnkovic, 2025b). Computation is not limited to digital devices but includes all processes that involve the transformation of information, with analog, quantum, and natural computation. The goal is not to simulate human cognition but to understand the informational structure and dynamics of systems.

Natural computation is the study of information processing in natural systems. It explores processes such as gene regulation, neural signaling, cellular communication, and morphogenesis. These processes are embodied—physical, chemical, and biological. They are distributed, parallel, asynchronous, and adaptive. The new computationalism sees cognition as a form of natural computation—an emergent property of complex systems that process information in order to maintain themselves and interact with their environment.

The traditional association of computation with disembodied symbol manipulation has created an artificial opposition between computational and embodied approaches to cognition, leading many researchers to reject computational frameworks as a priory incompatible with enactive alternatives. However, this rejection stems from an overly restrictive understanding of computation that fails to recognize the broader spectrum of computational processes operating in biological systems. Contemporary developments in computational theory have fundamentally expanded the concept of computation beyond classical Turing-machine models to encompass sub-symbolic, interactive, natural, and physical forms of information processing (Scheutz, 2002).

This expanded computational landscape contains spectrum—from algorithmic and symbolic processes to interactive, morphological, and natural forms (Burgin & Dodig-Crnkovic, 2015). Biological systems exemplify computational forms that transcend predefined algorithmic execution, instead computing through physical reorganization in response to interaction with internal and external signals as interactive computing, Wegner (1998). Living organisms operate as self-modifying computational agents (Kampis, 1991) where structure and process co-evolve continuously, creating dynamic systems that reconstruct their own computational architecture through interaction with their environment.

Table 3.

Types of Computation in Biological Systems.

Table 3.

Types of Computation in Biological Systems.

| Computation model |

Definition |

Biological Example |

Reference Model |

| Symbolic (Turing) |

Rule-based manipulation of discrete symbols |

Digital computers,

formal logic |

Turing machine |

| Sub-symbolic |

Pattern recognition without explicit symbol use |

Neural networks,

reflex arcs |

Connectionist models |

| Morphological |

Computation embedded in physical form and dynamics |

Plant growth, slime mold adaptation |

Pfeifer & Bongard (2006) |

| Self-modifying/ Bioelectric |

Recursive reconfiguration of structure and behavior based on internal feedback |

Regenerative repair in planaria, tissue morphogenesis |

Kampis (1991), Levin (2023) |

| Info-computation |

Integrated processing of form, information, and value-regulation |

All levels of life—cells to cognition |

Dodig-Crnkovic (2022, 2025) |

The recognition of diverse computational types shows how biological systems implement fundamentally different processing strategies across organizational scales. Symbolic computation operates through rule-based manipulation of discrete symbols, exemplified by digital computers and formal logic systems following Turing machine models. Sub-symbolic computation encompasses pattern recognition processes without explicit symbol use, manifested in neural networks and reflex arcs through connectionist architectures. Morphological computation embeds information processing within physical form and dynamics, demonstrated by plant growth patterns and slime mold adaptive behaviors. Bioelectric and self-modifying computation involves recursive reconfiguration of structure and behavior based on internal feedback, evident in regenerative repair processes and tissue morphogenesis. Info-computation represents integrated processing of form, information, and value regulation operating across all levels of biological organization from cellular systems to complex cognition (Dodig-Crnkovic, 2022, 2025).

Contemporary theoretical frameworks have formalized these insights through sophisticated mathematical models that bridge computational and biological approaches. Predictive processing and Free Energy Principle frameworks represent particularly influential developments that model cognition as probabilistic inference and self-organizing regulation (Friston, 2010). Cognitive systems engage in continual minimization of surprise through updating generative models of environmental conditions. This approach exemplifies computation where information processing occurs through probabilistic patterns distributed across neural and physical systems rather than exclusively through logical symbol manipulation on the human-language level.

Intelligence emerges as the competency with which organisms sustain adaptive inference under environmental uncertainty, representing a fundamental shift from viewing intelligence as abstract problem-solving capacity toward understanding it as embodied regulatory competence. This perspective integrates computational rigor with biological realism, demonstrating that sophisticated information processing can occur through physical dynamics without requiring symbolic representation.

Intelligence is not a centralized function but an emergent property of distributed information processing. It is not limited to systems that represent the world but includes systems that interact with the world in a goal-directed way. Intelligence is the capacity of a system to adaptively transform information in order to solve problems and maintain its organization. Sometimes it is defined as an ability to acquire and apply “knowledge” (another complex concept). It is the ability to learn from experience, adapt to new situations, solve problems, plan and strategize, and make sound decisions (with the respect to the agent’s goals). Intelligence involves memory and creativity.

The theoretical synthesis of embodied computation reaches its comprehensive expression through info-computationalism, which frames cognition as embodied computation unfolding within and through physical structures (Dodig-Crnkovic, 2012, 2022, 2025). This framework unifies symbolic and sub-symbolic processes under morphological computation, where form, function, and information co-evolve within physical systems. Cognition transcends mere symbol manipulation to encompass the lived regulation of life processes through dynamic interactions integrating matter, energy, and information into coherent organizational patterns.

Living systems operate as morphologically computing agents that continually reconstruct their organizational structure in response to environmental inputs and internal regulatory requirements, effectively computing their own subsequent states through embodied processes. This perspective supports a spectrum-based view of cognition that extends mental functions beyond humans and animals with nervous systems to encompass the full range of living systems. The theoretical imperative to de-anthropomorphize mind provides robust support for interpreting even minimal evaluative behaviors as genuinely cognitive—not through metaphorical extension but through functional equivalence.

This reconceptualization dissolves the alleged contradiction between computational and embodied approaches by revealing computation itself as necessarily embodied in natural systems. Rather than opposing computation to embodiment, contemporary information processing frameworks demonstrate that the most sophisticated forms of biological computation emerge precisely through embodied processes that integrate information processing with physical organization. Intelligence and cognition thus represent different aspects of the same fundamental phenomenon: the capacity of living systems to process information through their own organizational dynamics while maintaining adaptive relationships with their environments.

6. Conclusions

The exploration of cognition and intelligence across diverse theoretical traditions reveals a field characterized by fundamental conceptual tensions that extend far academic debate. Despite their centrality to multiple disciplines, these concepts remain poorly understood, largely due to definitional frameworks that fail to capture the full scope of contemporary scientific understanding.

Two fundamentally different theoretical orientations emerge from this analysis. The human-centered tradition conceptualizes cognition as distinctively human mental processes, with intelligence representing a specialized subset encompassing reasoning, problem-solving, and learning capacities (Neisser, 1967; Sternberg, 1985). This perspective restricts cognitive processes to organisms possessing advanced neural architectures and privileges abstract symbolic operations over embodied interactions (Newell & Simon, 1972).

In contrast, the life-centered tradition identifies cognition with the process of life itself, recognizing intelligent behavior as the competency of living systems to solve problems under conditions of novelty and uncertainty (Maturana & Varela, 1980; Lyon, 2006). This perspective fundamentally expands the scope of cognitive science by demonstrating that cognitive processes operate across all levels of biological organization, from cellular systems to complex multicellular organisms (Levin, 2019).

This theoretical divergence occurs through parallel development within distinct disciplinary contexts. Human-centered perspectives dominate philosophy of mind, mainstream psychology, neuroscience, and public discourse, while life-centered approaches flourish within biology, systems theory, information studies and cybernetics (Bateson, 1979; Rosen, 1985/2012). Their consequences extend far beyond academic boundaries, fundamentally shaping scientific practice and technological development.

In artificial intelligence, human-centered perspectives encourage systems designed to replicate human mental processes such as logical reasoning as represetative for cognition and symbolic problem-solving for intelligence (Turing, 1950)(Gignac & Szodorai, 2024). Life-centered perspectives, on the other hand, inspire designs based on biological organization principles, including adaptation, self-maintenance, and anticipatory control (Lyon, 2006; Pfeifer & Bongard, 2006). These approaches emphasize emergent intelligence through dynamic component interaction rather than abstract reasoning capabilities.

In medicine and neuroscience, life-centered perspectives transform practice by recognizing that cells, tissues, and organ systems exhibit genuine cognitive properties including memory, learning, and decision-making (Levin, 2019). This recognition reshapes approaches to regenerative medicine and cancer research by revealing cognitive processes at cellular levels (Levin & Dennett, 2021). Synthetic biology benefits from leveraging natural cognitive capacities for autonomous, adaptive biotechnological solutions (Lyon, 2006).

Contemporary computational frameworks further demonstrate significance of these distinctions. Developments in morphological computation, predictive processing, and info-computationalism reveal that computational and embodied approaches can be integrated when computation is understood as necessarily embodied in natural systems (Friston, 2010; Hauser, Füchslin, & Pfeifer, 2014; Dodig-Crnkovic, 2012). These frameworks suggest that sophisticated intelligence emerges through integrating information processing with physical organization.

Rather than viewing these perspectives as mutually exclusive, future research may benefit from recognizing their complementary insights. Human-centered approaches excel at analyzing complex symbolic reasoning and conscious experience in humans, while life-centered approaches reveal fundamental cognitive processes underlying all biological organization. The choice between these theoretical frameworks reflects deeper commitments about mind and life that shape both scientific inquiry and technological development. As we enter an era defined by intelligent technologies and biological interventions, these theoretical foundations will determine how we understand and design systems that interact with, enhance, or replicate cognitive capacities.

References

- American Psychological Association (APA). (2023). Cognition. APA Dictionary of Psychology.

- Bateson, G. (1979). Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity. Dutton.

- Ben-Jacob, E. (2009) Learning from bacteria about natural information processing. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1178:78-90. [CrossRef]

- Burgin, M. and Dodig-Crnkovic, G. (2015) “A Taxonomy of Computation and Information Architecture”. In: “Proceedings of the 2015 European Conference on Software Architecture Workshops (ECSAW ‘15)”. ACM, New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J. B. (1993). Human Cognitive Abilities: A Survey of Factor-Analytic Studies. Cambridge University Press.

- Clark, A. (1989). Microcognition: Philosophy, Cognitive Science, and Parallel Distributed Processing. MIT Press.

- Clark, A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(3), 181–204.

- Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58(1), 7–19.

- Deacon, T. (1997). The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. W.W. Norton.

- Deacon, T. (2012). Incomplete Nature: How Mind Emerged from Matter. W.W. Norton.

- Dodig-Crnkovic, G. (2012) Info-computationalism and Morphological Computing of Informational Structure. In Integral Biomathics; Simeonov, P., Smith, L., Ehresmann, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, pp. 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Dodig-Crnkovic, G. (2017) Nature as a Network of Morphological Infocomputational Processes for Cognitive Agents, The European Physical Journal Special Topics. Eur. Phys. J. 2017, 226, 181–195. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1140/epjst/e2016-60362-9. [CrossRef]

- Dodig-Crnkovic, G. (2022) Natural computation of cognition, from single cells up. In: Unconventional Computing, Arts, Philosophy; World Scientific: Singapore; pp. 57–78. [CrossRef]

- Dodig-Crnkovic, G. (2025a) De-Anthropomorphizing the Mind: Life as a Cognitive Spectrum. A Unified Framework for Biological Minds. Preprints. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202503.1449/v2.

- Dodig-Crnkovic, G. (2025b) Sensing, Feeling, Affect, And The Origins Of Cognition In Biological Systems, Preprint https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202506.0840/v1. [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M. W., & Brysbaert, M. (2023). Fundamentals of Cognition (4th ed.). Routledge, London.

- Foglia, L. & Wilson, R. A. (2013) Embodied cognition WIREs Cogn Sci, 4:319–325. [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138. [CrossRef]

- Gignac, G. E., Szodorai E. T. (2024) Defining intelligence: Bridging the gap between human and artificial perspectives, Intelligence, Volume 104. [CrossRef]

- Hauser, H., Füchslin, R. M., & Pfeifer, R. (2014). Opinions and Outlooks on Morphological Computation. https://www.morphologicalcomputation.org/e-book.

- Just, B. B., & Torres de Farias, S. (2024). Living cognition and the nature of organisms. Biosystems, 246, 105356. [CrossRef]

- Kampis, G. (1991) Self-Modifying Systems in Biology and Cognitive Science. A New Framework For Dynamics, Information, and Complexity, Pergamon Press.

- Levin, M. (2019). The computational boundary of a “self”: Developmental bioelectricity drives multicellularity and scale-free cognition. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2688.

- Levin, M., & Dennett, D. (2021). Cognition all the way down. Biological Theory, 16(1), 1–18.

- Lyon P, Keijzer F, Arendt D, Levin M (2021) Reframing cognition: getting down to biological basics. Philos Trans Royal Soc B Biol Sci. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1098/ rstb. 2019. 0750.

- Lyon, P. (2006). The biogenic approach to cognition. Cognitive Processing, 7(1), 11–29.

- Lyon, P. (2020) Of what is “minimal cognition” the half-baked version? Adapt Behav 28(6):407–424. [CrossRef]

- Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1980). Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. Reidel.

- Mella, P. (2020). Bateson’s Model of the Mind and the Fundamental Conjecture on Cognition. In: Constructing Reality. SpringerBriefs in Psychology(). Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Neisser, U. (1967). Cognitive Psychology. Prentice-Hall.

- Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human Problem Solving. Prentice-Hall.

- Newen, A., De Bruin, L., & Gallagher, S. (Eds.). (2018). The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition. Oxford University Press.

- Pfeifer, R., Bongard, J. (2006) How the Body Shapes the Way We Think: A New View of Intelligence, The MIT Press . [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. International Universities Press.

- Piaget, J. (1970). Genetic Epistemology. Columbia University Press.

- Prinz, J. (2004). Gut Reactions: A Perceptual Theory of Emotion. Oxford University Press.

- Rosen, R. (1985/2012). Anticipatory Systems: Philosophical, Mathematical, and Methodological Foundations. Springer.

- Scheutz, M. (Ed.). (2002). Computationalism: New Directions. MIT Press.

- Shapiro, L. (2019). Embodied Cognition (2nd ed.). Routledge, London.

- Sternberg, R. J. (1985). Beyond IQ: A Triarchic Theory of Human Intelligence. Cambridge University Press.

- Turing, A. M. (1950). Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Mind, 59(236), 433–460. [CrossRef]

- Vallverdú J, Castro O, Mayne R, Talanov M, Levin M, Baluška F, Gunji Y, Dussutour A, Zenil H, Adamatzky A. (2018) Slime mould: The fundamental mechanisms of biological cognition. Biosystems. 165:57-70. [CrossRef]

- Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. MIT Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press.

- Wegner, P. (1998) Interactive foundations of computing, Theoretical Computer Science, Vol.192(2), pp. 315-351. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).