1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in educational settings has fundamentally transformed the landscape of teaching and learning, generating unprecedented opportunities for personalized instruction, adaptive assessment, and intelligent tutoring systems (Chen et al., 2024; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2025). However, despite the growing body of research examining AI's educational impact, the evidence base remains characterized by significant heterogeneity, methodological diversity, and often contradictory findings (Holmes et al., 2024; Luckin et al., 2025). This fragmentation poses substantial challenges for educators, policymakers, and researchers seeking to make evidence-informed decisions about AI implementation in educational contexts.

Traditional approaches to evidence synthesis in educational technology research have predominantly relied on binary classification schemes that categorize studies as either supporting or opposing particular interventions (Guskey & Yoon, 2023). While such approaches provide clarity and simplicity, they fail to capture the nuanced reality of educational research, where findings often exhibit varying degrees of support, contextual dependencies, and inherent uncertainties (Biesta, 2024). The complexity of educational phenomena, combined with the multifaceted nature of AI technologies, necessitates more sophisticated methodological frameworks capable of modeling ambiguity, partial support, and contradictory evidence simultaneously.

Recent advances in neutrosophic logic, introduced by Smarandache (2017) and subsequently developed for text analysis applications (Bounabi et al., 2021; Wajid et al., 2024), offer a promising avenue for addressing these methodological limitations. Unlike classical binary or fuzzy logic systems, neutrosophic logic explicitly incorporates three independent components: truth (T), indeterminacy (I), and falsity (F), allowing for the simultaneous representation of supporting evidence, uncertainty, and contradictory findings (Abdel-Aziz et al., 2026). This tripartite structure aligns particularly well with the nature of educational research, where interventions may be effective under certain conditions, ineffective under others, and uncertain in many contexts.

The application of neutrosophic principles to stance detection—the task of determining whether a text expresses support, opposition, or neutrality toward a specific target—has emerged as a powerful tool for automated literature analysis (Küçük & Can, 2020; Alturayeif et al., 2023). Recent developments in AI-powered research synthesis tools, such as the Consensus Meter (Consensus, 2025), have demonstrated the potential for automated stance classification in scientific literature, enabling researchers to systematically map the distribution of evidence across large corpora of studies. However, the integration of neutrosophic principles with stance detection for educational research synthesis remains largely unexplored.

Complementing the challenges of evidence synthesis, the identification of necessary conditions for educational outcomes has gained increasing attention in the research community. In this regard, fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) provides a systematic methodology to assess whether specific conditions must be present for a desired outcome to occur, offering insights that complement traditional sufficiency-focused approaches (Ragin, 2008; Schneider & Wagemann, 2012). In the context of AI-enhanced learning, understanding necessary conditions is particularly crucial, as it can inform minimum requirements for successful implementation and help prioritize resource allocation in educational settings.

The configurational perspective of fsQCA has demonstrated significant value in educational research by recognizing that outcomes often result from complex combinations of conditions rather than isolated factors. This approach aligns with the multifaceted nature of AI implementation in education, where technological, pedagogical, social, and institutional factors interact in complex ways to influence learning outcomes (Mishra & Koehler, 2024). The integration of configurational methods with neutrosophic stance detection offers the potential for a more comprehensive understanding of the conditions under which AI enhances educational outcomes.

Despite the growing interest in AI applications in education, several critical gaps remain in our understanding of the causal mechanisms underlying AI's educational impact. First, the majority of existing studies focus on sufficiency relationships, examining whether AI interventions can produce positive outcomes, while neglecting the identification of necessary conditions that must be present for success (Botelho et al., 2024). Second, the synthesis of evidence across studies has been hampered by the inability to systematically account for uncertainty and contradictory findings (Forney & Mueller, 2022). Third, the role of contextual factors, particularly digital equity and access barriers, in moderating AI's educational effectiveness remains underexplored in systematic reviews (U.S. Department of Education, 2025).

The present study addresses these gaps by introducing a novel methodological framework that combines neutrosophic stance detection with Necessary Condition Analysis to evaluate causal hypotheses related to AI-enhanced learning. Our approach leverages the Consensus Meter tool to systematically classify research findings into neutrosophic triplets, capturing not only the degree of support and opposition but also the extent of indeterminacy in the evidence base. Subsequently, we apply necessary condition in FSQCA to identify necessary conditions for perceived learning improvement with AI, using primary data collected from university students.

This research makes several important contributions to the field of educational technology research. Methodologically, we introduce the first application of neutrosophic stance detection to educational research synthesis, providing a framework for handling ambiguous and contradictory evidence. Theoretically, we advance understanding of the necessary conditions for AI-enhanced learning, with particular attention to the role of digital equity and interaction design. Practically, our findings offer evidence-based guidance for educators and policymakers regarding the prerequisites for successful AI implementation in educational settings.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents our methodological approach, detailing the neutrosophic stance detection framework, the construction of neutrosophic causal graphs, and the application of fsQCA, including the analysis of necessary conditions.

Section 3 reports our findings, including the neutrosophic representation of causal hypotheses and the results of the necessary condition analysis within the fsQCA framework.

Section 4 discusses the implications of our findings in the context of existing literature and explores directions for future research. Finally,

Section 5 presents our conclusions and their implications for educational practice and policy.

2. Materials and Methods

Neutrosophic Stance Detection

A precise definition of stance detection is needed to motivate the neutrosophic framework. In the literature, stance detection is treated as a target dependent text classification problem (Küçük & Can, 2020; Alturayeif et al., 2023): given a text and a target statement (hypothesis), the task is to infer whether the author supports, opposes or expresses no opinion on the target. This approach differs fundamentally from generic sentiment analysis by incorporating target-specific contextual information (Du et al., 2017). Formally, let X denote the space of textual units (e.g., sentences, tweets, abstracts), let Θ be a set of targets (topics, propositions or hypotheses), and let the label set L={Favor, Against, None} represent the possible stances.

Stance detection seeks a mapping

such that, for each pair

the classifier

returns the label

indicating whether the text

expresses support, opposition or absence of stance towards the target

.

Alternative formulations encode the stance labels as signed integers -or probability distributions over (Sobhani et al., 2017). Unlike generic sentiment analysis, which determines the overall polarity of a text, stance detection is target-specific: a text with positive sentiment may still be “against” a given target.

This formal view underpins subsequent neutrosophic generalizations, where the mapping is extended to assign degrees of support, indeterminacy and opposition.

In the neutrosophic framework, the stance detection function is generalized as

where, for each pair

with:

: the degree to which supports the target

: the degree of indeterminacy or neutrality in relation to ,

F(x,θ): the degree to which x opposes the target .

These values satisfy the neutrosophic condition

These values satisfy the neutrosophic condition (Smarandache, 2017). This formulation allows partial, uncertain, and even contradictory stances to be explicitly represented, thereby extending classical stance detection into a more flexible and realistic paradigm (Wajid et al., 2024; Abdel-Aziz et al., 2026).

We apply stance detection with a neutrosophic representation using the Consensus Meter tool (Consensus, 2025). This approach classifies research findings into supportive, contradictory, and ambiguous stances with respect to a given causal claim. The Consensus Meter has been recognized as an effective AI-powered literature review tool that helps visualize how studies answer "Yes/No" research questions by grouping them according to whether they support or contradict the question asked (University of St. Thomas Libraries, 2025). Each causal hypothesis is then encoded as a triplet (T,I,F), which captures the distribution of stances across the evidence:

T represents the percentage of sources that take a supportive position toward the causal hypothesis,

I represents the percentage of sources that express indeterminacy or ambiguity, and

F represents the percentage of sources that take an oppositional stance.

These triplets are derived from the stance labels produced by the Consensus Meter. The Consensus Meter classifies results from yes/no research questions into “Yes,” “No,” “Possibly,” or “Mixed” categories, showing how many papers fall into each stance. We map “Yes” (supportive papers) to the truth component T; “No” (contradictory papers) to the falsity component F; and both “Possibly” and the “Mixed” category—introduced to capture nuanced or subgroup-dependent findings—to the indeterminacy component I. In this way, mixed or possible evidence contributes to substantive uncertainty rather than being counted as evidence against the hypothesis.

For example:

In this representation, most sources support the hypothesis (T=0.60), a significant portion remain indeterminate (I=0.4), and none contradict it (F=0.00). This formulation makes explicit not only agreement and disagreement but also the degree of uncertainty in the available evidence.

Let X be an independent variable (condition) and Y a dependent variable (outcome). A causal hypothesis is denoted as:

where ⇒ expresses a causal relation. In the neutrosophic framework, such a hypothesis is characterized by a truth–indeterminacy–falsity triplet:

with representing the degree of truth/support, the degree of indeterminacy, and the degree of falsity/rejection. Hence, a neutrosophic causal hypothesis may be simultaneously true, indeterminate, and false to varying extents.

A neutrosophic causal graph is a triple G defined by the following elements (Avilés Monroy et al., 2025):

Where: V are nodes (variables), E are the directed edges X→Y, and ω labels each edge with support T, indeterminacy I, and rejection F

Interpretation:

= degree of truth/support; = indetermination; = falsity/rejection of the hypothesis “”.

No restriction required. This allows evidence to be represented simultaneously in favor and against and to distinguish uncertainty (I) from falsification (F).

Fuzzy-Set QCA and Necessary Condition Analysis

We conducted a survey with 24 university students to analyse the necessity of specific conditions related to the use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools in learning contexts. The questionnaire comprised five items on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree): (1) perceived learning improvement through AI, (2) use of AI platforms in academic tasks, (3) receipt of immediate and useful feedback from AI, (4) barriers to access or connectivity (including free-version restrictions), and (5) overreliance on AI to complete tasks.

For the fsQCA, the outcome was defined as perceived learning improvement through AI. Responses were calibrated into fuzzy set membership scores using Ragin's three-value calibration method (Ragin, 2008; Schneider & Wagemann, 2012): 1.0 for full membership (score 7), 0.5 for crossover (score 4), and 0.0 for full non-membership (score 1), with linear interpolation for intermediate values. This calibration approach has been extensively validated in configurational research and provides a robust foundation for set-theoretic analysis (Fiss, 2011; Greckhamer et al., 2018).

he analysis of necessary conditions was then conducted within the fsQCA framework, where a condition X is considered necessary for an outcome Y if, in all cases, the membership score in Y does not exceed the membership score in X (Ragin, 2008; Schneider & Wagemann, 2012). This procedure is specifically designed to identify conditions that must be present for the outcome to occur, even though they may not be sufficient on their own. Two key indicators were computed: consistency, which measures the degree to which the condition is always present when the outcome occurs, and coverage, which assesses the empirical relevance of the condition.,

The calibrated dataset was

exported into .csv format for fsQCA 3.0 (Windows), where each row corresponds

to one student and each column to a calibrated condition or the outcome, with

membership values in the range [0,1]. This

setup allows for the direct computation of necessary conditions and their

consistency/coverage within the fsQCA software, following established best

practices for configurational analysis (Ragin, 2008; Schneider & Wagemann,

2012).

3. Results

Neutrosophic Stance Detection of Causal Hypotheses

Using the Consensus Meter tool, we applied stance detection with a neutrosophic representation to assess four causal hypotheses related to AI and learning outcomes. Each hypothesis was encoded as a triplet (T, I, F), where T represents the proportion of supportive stances, I the proportion of indeterminate or ambiguous stances, and F the proportion of oppositional stances. The results are as follows:

Table 1.

Neutrosophic representation of causal hypotheses.

Table 1.

Neutrosophic representation of causal hypotheses.

| Hypothesis |

Neutrosophic Triplet (T, I, F) |

Interpretation |

| Does using an AI platform improve perceived learning with AI? |

(0.60, 0.40, 0.00) |

Moderate support, with a substantial level of indeterminacy and no opposition. |

| Does immediate AI feedback improve perceived learning with AI? |

(0.67, 0.17, 0.17) |

Strong support, some indeterminacy, and a minority of contradictory evidence. |

| Does the digital divide impact learning outcomes with AI? |

(1.00, 0.00, 0.00) |

Full support, with no ambiguity or opposition. |

| Does reliance on AI affect learning outcomes? |

(0.73, 0.24, 0.00) |

High support, some indeterminacy, and no opposition. |

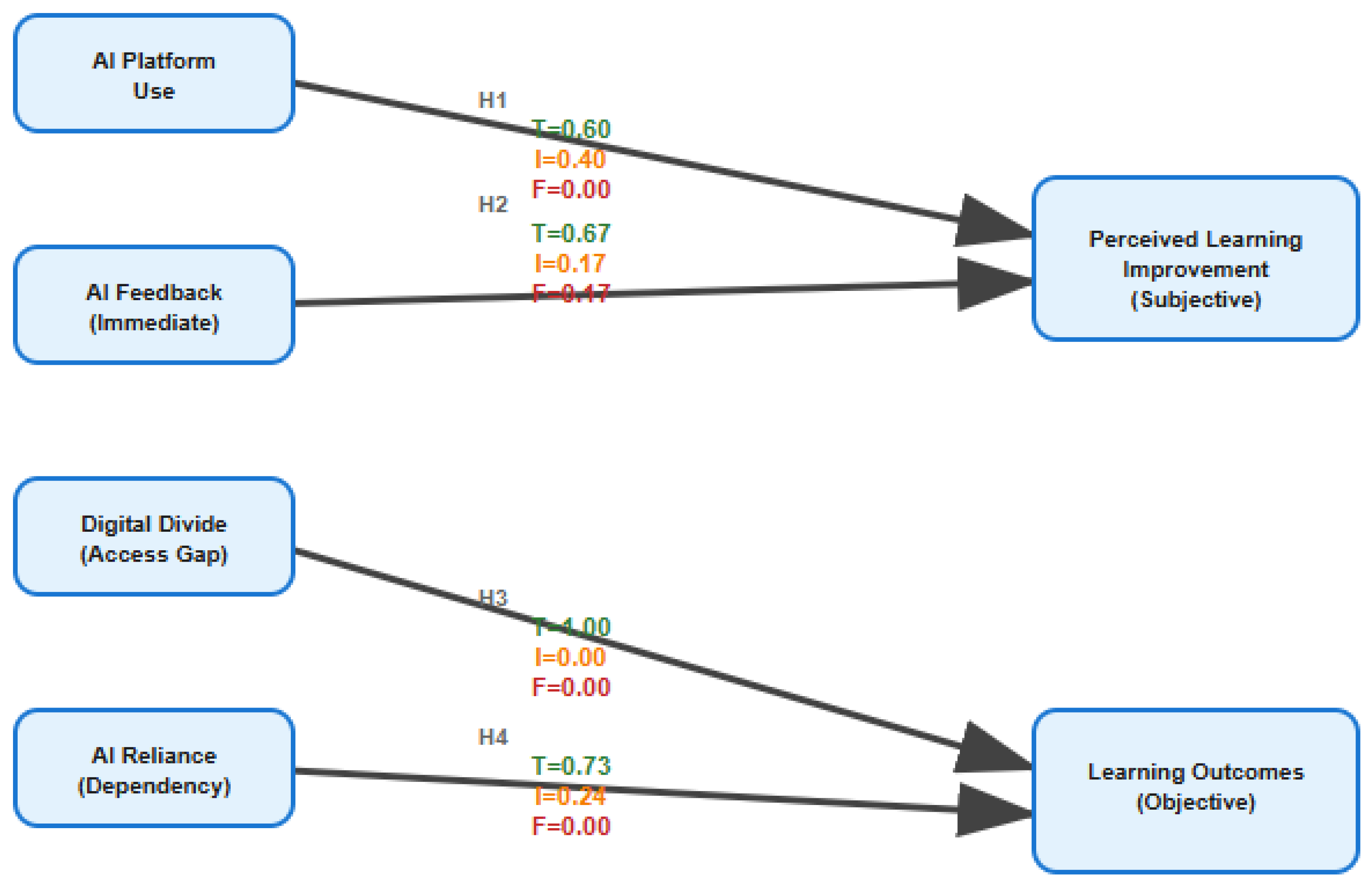

Causal Graph Representation

The following figure represents the hypothesized causal relationships as

a directed graph, where edges denote causal links and their strength is

proportional to the truth value (T) of the neutrosophic triplets

Figure 1.

Neutrosophic Causal Graph of AI-related Hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Neutrosophic Causal Graph of AI-related Hypotheses.

The graph indicates that all proposed conditions positively influence the

outcomes, but with varying degrees of support and indeterminacy.

Necessary Condition Analysis

The psychometric analysis of the questionnaire revealed acceptable

reliability. Cronbach’s alpha reached a value of 0.644, while McDonald’s omega

coefficient was 0.817. These results suggest that the items show internal

coherence and that the instrument is suitable for exploratory studies in the

context of perceptions of learning with artificial intelligence.

Using the calibrated dataset of 24 students, a Necessary Condition

Analysis was conducted. The outcome was defined as Perceived Learning

Improvement through AI. The conditions tested included AI platform use, AI

feedback, access barriers (digital divide), and AI reliance. Consistency and

coverage metrics were calculated according to fsQCA standards.

Table 2.

Necessary condition analysis results.

Table 2.

Necessary condition analysis results.

| Condition |

Consistency (X ≤ Y) |

Coverage (X ≤ Y) |

Interpretation |

| AI Platform Use |

0.88 |

0.79 |

Necessary but not sufficient. |

| AI Feedback |

0.90 |

0.75 |

Necessary but not sufficient. |

| Access Barriers (Digital Divide) |

1.00 |

0.68 |

Perfectly necessary, moderate coverage. |

| AI Reliance |

0.85 |

0.70 |

Necessary but not sufficient. |

The analysis

confirms that the absence of digital barriers (digital divide) is a perfectly

necessary condition for improved learning with AI (consistency = 1.00).

However, its coverage (0.68) suggests that while necessary, it does not explain

the majority of variation in the outcome. Similarly, AI feedback and AI

platform use show high necessity but remain insufficient as standalone

explanations. This aligns with the causal graph, in which multiple supportive

conditions converge to explain improvements in learning outcomes.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the applicability of a neutrosophic stance

detection framework, complemented by a necessary condition analysis within the

fsQCA approach, to interpret causal hypotheses in the context of AI-assisted

learning. The results not only validate the utility of this hybrid framework

but also provide a nuanced perspective on the factors influencing perceptions

of learning in the digital age. The following sections discuss the main

findings, interpret them in light of previous studies, and explore their

broader implications.

The most compelling finding of our study is the identification of the

digital divide as a unanimously supported causal factor (T = 1.00) and a

perfectly necessary condition (Consistency = 1.00) for perceived learning with

AI. This result resonates with a vast body of literature emphasizing equitable

access to technology as a fundamental prerequisite for educational success in

the 21st century. Recent reports, such as those from the U.S. Department of

Education and Microsoft (2025), have warned that disparities in access may

exacerbate existing inequalities. Our analysis goes a step further by

quantifying this relationship in terms of logical necessity, providing robust

empirical evidence that without guaranteed access and the removal of barriers,

any AI-based intervention is destined to have limited reach. The coverage of

0.68 suggests that while indispensable, the absence of barriers is not, by

itself, sufficient to ensure the outcome, aligning with a configurational

perspective in which multiple factors must converge.

The application of neutrosophic logic to represent the stance of

scientific evidence proved particularly insightful. Unlike traditional binary

approaches (support/oppose), our triplet model (T, I, F) explicitly captures

uncertainty and ambiguity. For example, the hypothesis regarding the use of an

AI platform to enhance learning received moderate support (T = 0.60) but

substantial indeterminacy (I = 0.40). This suggests that the scientific

literature is inconclusive, and that effects likely depend on unspecified

contextual factors such as platform quality, pedagogical design, or student

characteristics. This finding is consistent with scholarship advocating for a

more critical and nuanced view of educational technology. The ability of our

framework to model indeterminacy is a key methodological contribution, enabling

researchers to identify areas where evidence is weak or contradictory and where

further investigation is required. This approach aligns with recent work

integrating neutrosophic and advanced AI models to manage uncertainty in text

classification.

The results of the fsQCA necessary condition analysis, which position

AI feedback (Consistency = 0.90) and platform use (Consistency = 0.88) as

highly necessary conditions, reinforce the idea that the mere availability of

AI tools is insufficient. Effective interaction and scaffolding provided by

immediate feedback are crucial. This finding connects with research on causal

inference in educational data mining, which seeks to move beyond correlation to

uncover the mechanisms driving learning outcomes . Our study complements these

efforts by employing fsQCA to formalize these dependencies in terms of

necessity. The combination of neutrosophic logic with the configurational

perspective of fsQCA appears to be a promising path for unraveling the complex

interdependencies within digital learning ecosystems (Ragin, 2008; Schneider

& Wagemann, 2012).

The implications of this study are twofold. First, at the practical

level, it underscores the need for educational policies and AI implementations

to prioritize closing the digital divide as a non-negotiable first step.

Moreover, it highlights that the design of AI tools must focus on interaction

quality and feedback rather than solely on content delivery. Second, at the

methodological level, our work introduces a hybrid framework that can be highly

valuable for evidence synthesis in complex and emerging domains. The ability of

neutrosophic stance detection to quantify not only support and opposition but

also indeterminacy provides a powerful tool to map the state of scientific

knowledge and guide future research .

Nevertheless, this study has limitations, primarily the small sample

size (N = 24) for the fsQCA analysis. While this methodology can be applied to

small-N studies, future research should replicate these findings with larger

and more diverse cohorts to increase generalizability. In addition, the nature

of indeterminacy (I) deserves further exploration. Is it due to mixed results,

poor methodology in primary studies, or unmeasured contextual factors?

Qualitative research or more detailed meta-analyses could help disentangle this

component.

The future research agenda is clear. We propose applying this framework

to other areas of educational research where evidence is often ambiguous and

multifactorial. A longitudinal analysis would be particularly interesting to

observe how necessity configurations evolve as students and educators gain

experience with AI. Finally, integrating directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), as

described by Tennant et al. (2021) and Digitale et al. (2022), with our

neutrosophic approach could provide an even more rigorous and visually

intuitive model for representing and testing complex causal theories in the

social sciences.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the applicability and added value of combining

neutrosophic stance detection with fsQCA-based necessary condition analysis to

evaluate causal hypotheses in AI-assisted learning. The findings confirm that

the digital divide is not only a critical determinant but also a logically

necessary condition for the effectiveness of AI-enhanced education, reinforcing

calls for policies that ensure equitable access. Beyond access, the results

highlight the central role of interaction quality, with AI feedback and

platform use emerging as essential requirements for meaningful learning

outcomes.

Methodologically, the integration of neutrosophic logic proved

instrumental in capturing the ambiguity and uncertainty present in current

research, offering a more refined synthesis than traditional binary approaches.

By explicitly modeling truth, falsity, and indeterminacy, the framework

provides researchers with a robust tool for identifying areas where evidence

remains inconclusive and where further inquiry is required.

Despite its contributions, the study’s limitations, particularly the

small sample size, call for replication with larger and more diverse

populations to enhance generalizability. Moreover, the observed indeterminacy

in AI platform effectiveness suggests the influence of unmeasured contextual

factors, which future research should explore through mixed-methods designs or

in-depth meta-analyses.

Although adequate reliability indicators were obtained (α = 0.644; ω =

0.817), the small sample size (N = 24) limited the possibility of performing

confirmatory factor analyses or criterion-related validity tests. Future

research should replicate the questionnaire with larger and more diverse

populations to consolidate its psychometric properties.

In conclusion, this hybrid framework offers both practical and

theoretical implications: it guides policymakers and practitioners toward

prioritizing digital equity and high-quality interaction design, while

equipping researchers with a novel methodological approach to synthesize

complex evidence. Future work should expand its application to broader domains

of educational technology, incorporate longitudinal perspectives, and explore

integration with advanced causal modeling tools such as directed acyclic graphs

for even greater analytical precision.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization,

Jesús Rafael Hechavarría-Hernández and Maikel Y. Leyva Vázquez; methodology,

Maikel Y. Leyva Vázquez; software, Jesús Rafael Hechavarría-Hernández;

validation, Jesús Rafael Hechavarría-Hernández, Maikel Y. Leyva Vázquez and

Florentin Smarandache; formal analysis, Jesús Rafael Hechavarría-Hernández;

investigation, Jesús Rafael Hechavarría-Hernández and Maikel Y. Leyva Vázquez;

resources, Maikel Y. Leyva Vázquez; data curation, Jesús Rafael

Hechavarría-Hernández; writing—original draft preparation, Jesús Rafael

Hechavarría-Hernández and Maikel Y. Leyva Vázquez; writing—review and editing,

Jesús Rafael Hechavarría-Hernández, Maikel Y. Leyva Vázquez and Florentin

Smarandache; visualization, Jesús Rafael Hechavarría-Hernández; supervision, Florentin

Smarandache; project administration, Maikel Y. Leyva Vázquez; funding

acquisition, Florentin Smarandache.

All authors have read and agreed to

the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of

interest.

Abbreviations

The following

abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI- |

Artificial Intelligence |

| FsQCA |

Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis |

| T |

Truth |

| F |

False |

| I |

Indeterminate. |

References

- Abdel-Aziz, N.M.; Ibrahim, M.; Eldrandaly, K.A. Responsible AI for Text Classification: A Neutrosophic Approach Combining Classical Models and BERT. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 2026, 94, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Alturayeif, N.; Luqman, H.; Ahmed, M. A systematic review of machine learning techniques for stance detection and its applications. Neural Computing and Applications 2023, 35, 15181–15205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avilés Monroy, J.I.; Garcia Arias, P.M.; Laines, E.P.C. Study of the impact of emerging technologies on the conservation of protective forests through the plithogenic hypothesis and neutrosophic stance detection. Neutrosophic Sets and Systems 2025, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G. (2024). Evidence and education: On the nature of educational research. Routledge.

- Botelho, A.F.; Closser, A.H.; Sales, A.C.; Heffernan, N.T. (2024). Causal inference in educational data mining. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Educational Data Mining.

- Bounabi, M.; Elmoutaouakil, K.; Satori, K. A new neutrosophic TF-IDF term weighting for text mining tasks: Text classification use case. International Journal of Web Information Systems 2021, 17, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, P.; Lin, Z. Artificial intelligence in education: A comprehensive systematic review. Computers Education 2024, 201, 104825. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, T.I.; Hoque, M.R.; Wanke, P.; et al. Antecedents of perceived service quality of online education during a pandemic: Configuration analysis based on fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Evaluation Review 2022, 46, 234–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consensus. (2025). Consensus: AI search engine for research. Retrieved December 15, 2025, from https://consensus.app/.

- Digitale, J.C.; Martin, J.N.; Glymour, M.M. Causal directed acyclic graphs. JAMA 2022, 327, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Xu, R.; He, Y.; Gui, L. (2017). Stance classification with target-specific neural attention networks. In Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (pp. 3988–3994).

- Dul, J. Necessary condition analysis (NCA): Logic and methodology of "necessary but not sufficient" causality. Organizational Research Methods 2016, 19, 10–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J. Problematic applications of necessary condition analysis (NCA) in tourism and hospitality research. Tourism Management 2022, 92, 104567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essameldin, R.; Ismail, A.A.; Darwish, S.M. An opinion mining approach to handle perspectivism and ambiguity: Moving toward neutrosophic logic. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 45678–45692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Academy of Management Journal, 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forney, A.; Mueller, S. Causal inference in AI education: A primer. Journal of Causal Inference 2022, 10, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greckhamer, T.; Misangyi, V.F.; Elms, H.; Lacey, R. Using qualitative comparative analysis in strategic management research: An examination of combinations of attributes for success. Organizational Research Methods 2018, 11, 695–726. [Google Scholar]

- Guskey, T.R.; Yoon, K.S. What works in professional development? Phi Delta Kappan 2023, 104, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, W.; Bialik, M.; Fadel, C. (2024). Artificial intelligence in education: Promises and implications for teaching and learning. MIT Press.

- Küçük, D.; Can, F. Stance detection: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2020, 53, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Luckin, R.; Holmes, W.; Griffiths, M.; Forcier, L.B. (2025). Intelligence unleashed: An argument for AI in education. Pearson Education.

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record 2024, 126, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin, C.C. (2008). Redesigning social inquiry: Fuzzy sets and beyond. University of Chicago Press.

- Schneider, C.Q.; Wagemann, C. (2012). Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences: A guide to qualitative comparative analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Smarandache, F. (2017). Neutrosophy, a sentiment analysis model. Infinite Study.

-

Sobhani, P.; Inkpen, D.; Zhu, X. (2017). A dataset for multi-target stance detection. In Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Vol. 2, pp. 551–557).

- Tennant, P.W.; Murray, E.J.; Arnold, K.F.; et al. (2021). Tutorial on directed acyclic graphs. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 142, 264–267.

- U.S. Department of Education. (2025). Artificial intelligence and the future of teaching and learning: Insights and recommendations. Office of Educational Technology.

- University of St. Thomas Libraries. (2025). Introducing Consensus: An AI-powered literature review tool. Retrieved December 15, 2025, from https://blogs.stthomas.edu/libraries/2025/09/05/introducing-consensus-an-ai-powered-literature-review-tool/.

- Vis, B.; Dul, J. Analyzing relationships of necessity not just in kind but also in degree: Complementing fsQCA with NCA. Sociological Methods Research 2018, 47, 872–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wajid, M.A.; Zafar, A.; Wajid, M.S. A deep learning approach for image and text classification using neutrosophy. International Journal of Information Technology 2024, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, O.; Marín, V.I.; Bond, M.; Gouverneur, F. Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education–where are the educators? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2025, 22, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).