Submitted:

09 October 2024

Posted:

10 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Materials and Methods

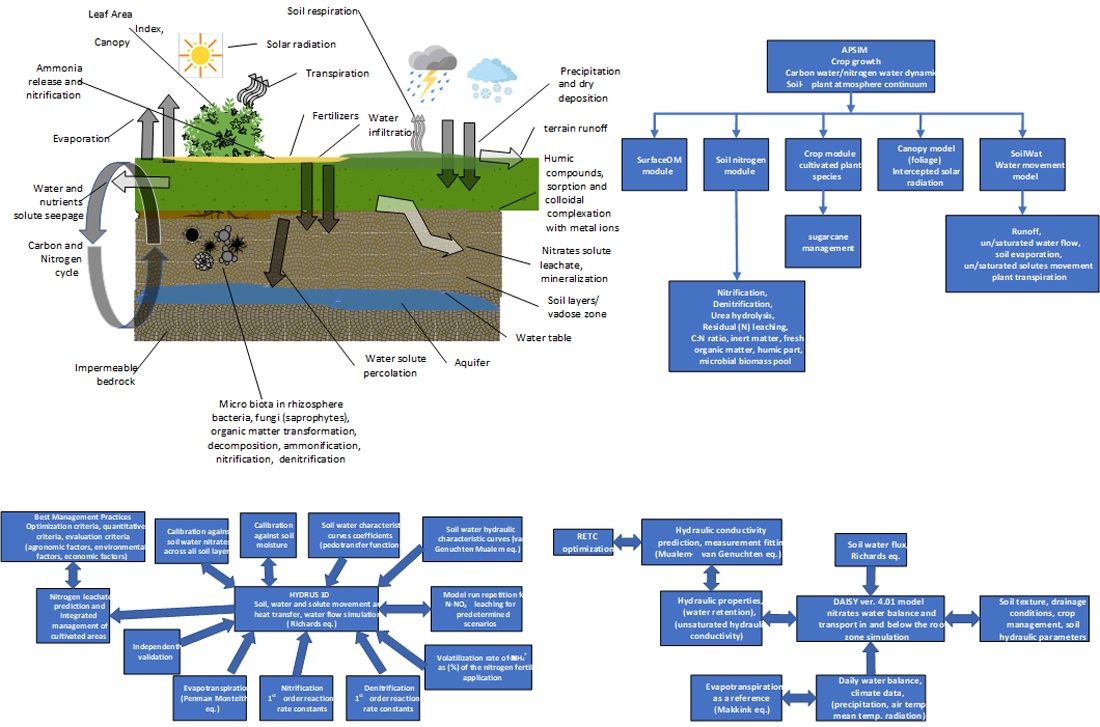

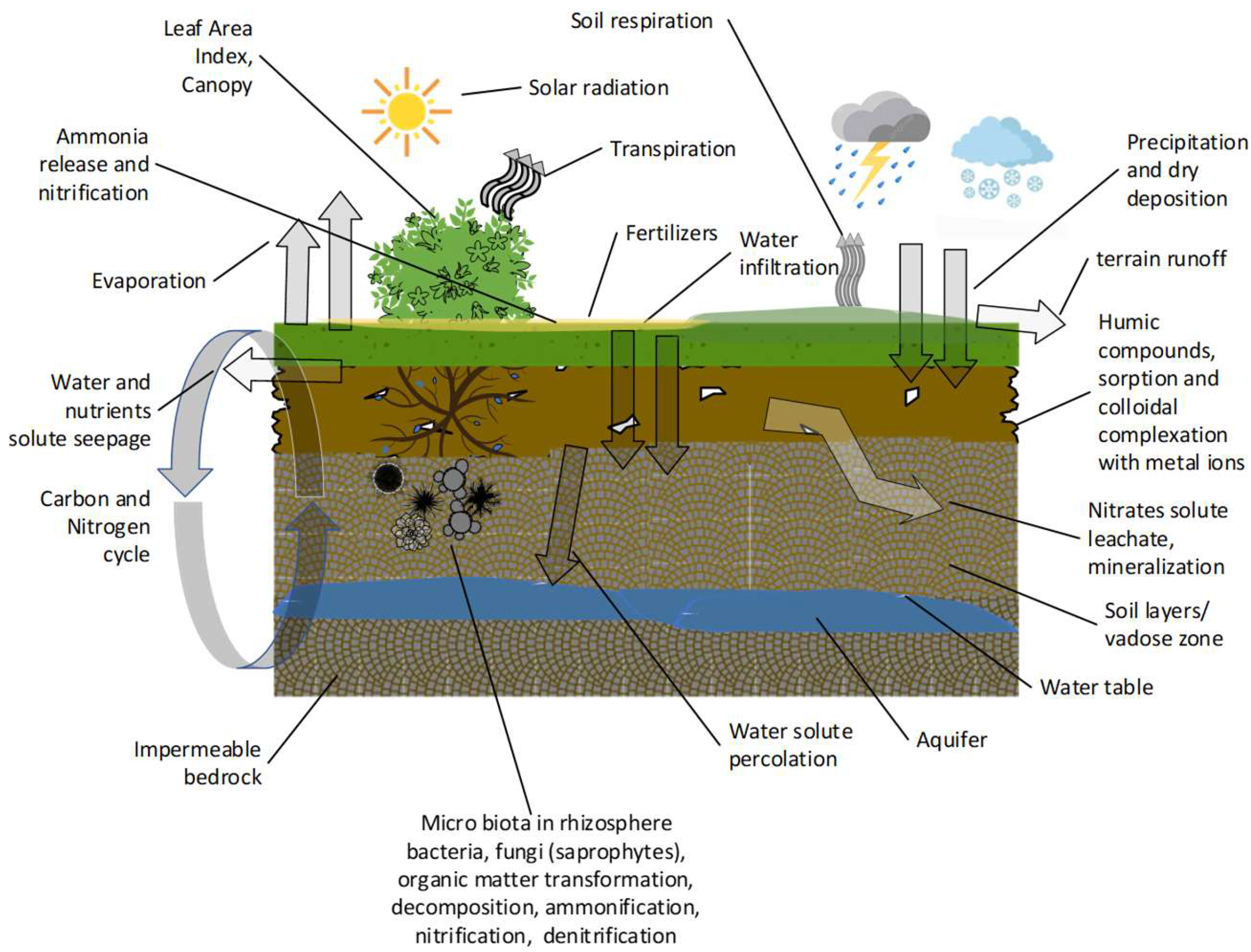

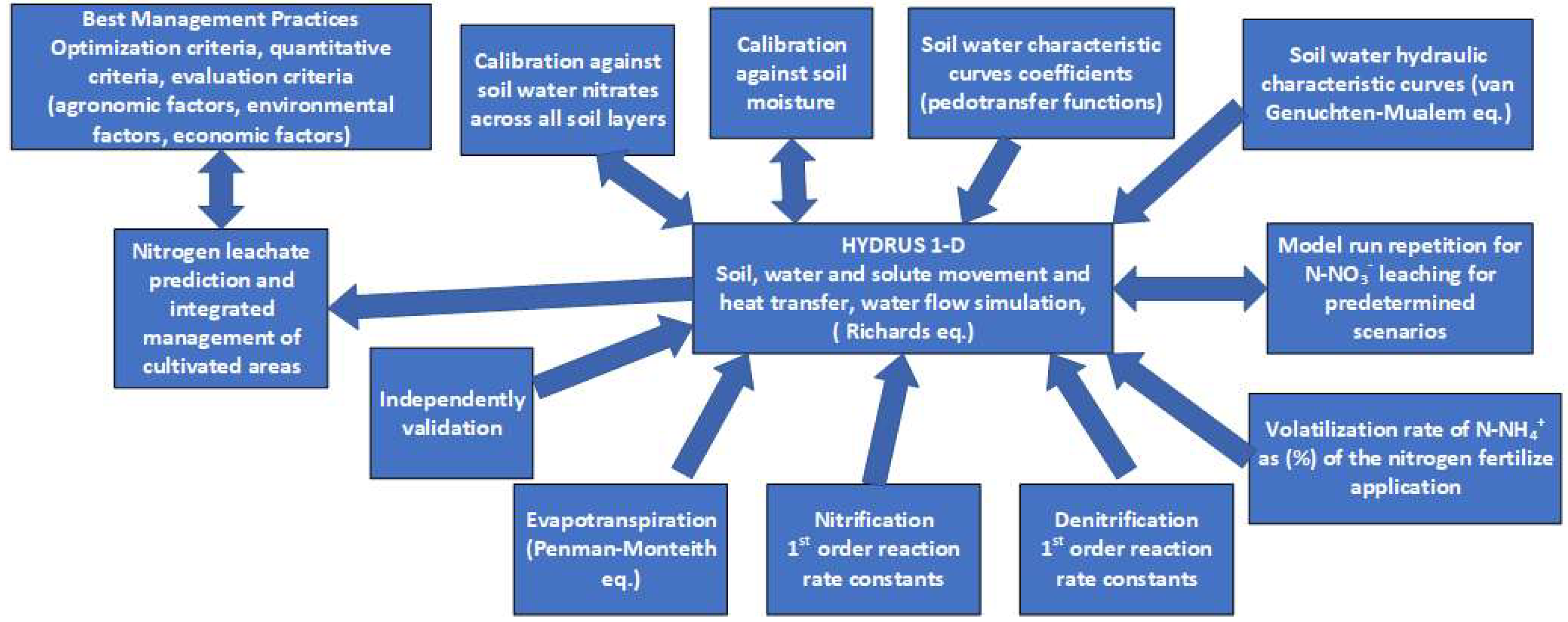

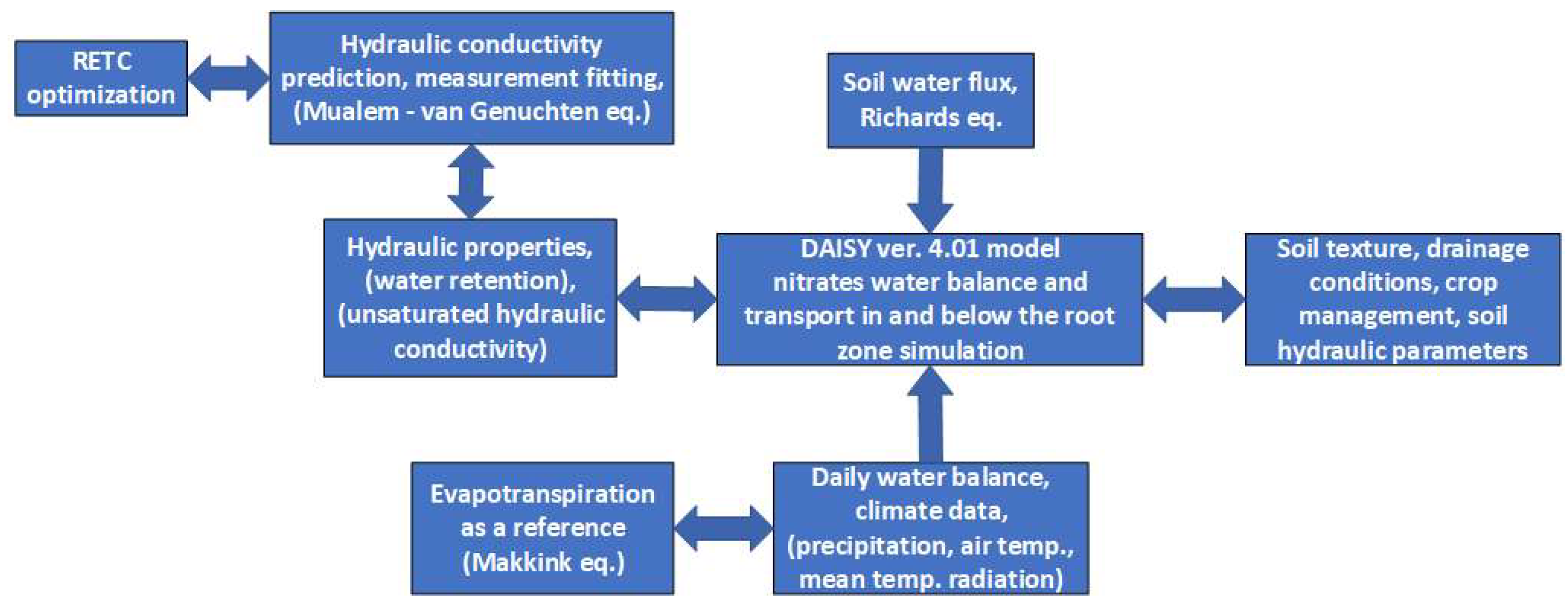

3.1. Process-based or conceptual models

3.2. Empirical Models Or Statistical Models

3.3 Deterministic Models

3.4 Stochastic models

3.5 Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning models

3.6 Physics-Based Models

4. Metal Ions Leaching and Solute Transport

4.1 Soil Medium

4.2 Modified Soil Medium

4.3 Cement Leaching Medium

4.4 Landfill Capping Layers

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Directive 91/676/EEC, concerning the protection of waters against pollution caused by nitrates from agricultural sources. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:01991L0676-20081211, (accessed ). 5 April.

- Directive 2015/1787/EU, amending Annexes II and III to Council Directive 98/83/EC on the quality of water intended for human consumption. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32015L1787, (accessed ). 5 April.

- UN, LEAP platform, regarding ΕU Council Directive 98/83/EC on the quality of water intended for human consumption. https://leap.unep.org/countries/eu/national-legislation/council-directive-9883ec-quality-water-intended-human-consumption (accessed ). 7 April.

- Directive 2000/60/EC, establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. Official Journal of the European Communities L327, 1-72. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32000L0060 (accessed ). 5 April.

- Directive 2008/105/EC, on environmental quality standards in the field of water policy, amending and subsequently repealing Council Directives 82/176/EEC, 83/513/EEC, 84/156/EEC, 84/491/EEC, 86/280/EEC and amending Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32008L0105, (accessed ). 5 April.

- Decision No 2455/2001/EC, official website of the European Parliament & the Council of , establishing the list of priority substances in the field of water policy and amending Directive 2000/60/EC, available on https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32001D2455, (accessed 5 April 2024). 20 November.

- Directive 2013/39/EU, amending Directives 2000/60/EC and 2008/105/EC as regards priority substances in the field of water policy. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013L0039, (accessed ). 5 April.

- Regulation (EU) 2020/741 on minimum requirements for water reuse, official journal available on https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32020R0741&from=EN, (accessed ). 7 April.

- Interreg EU, ‘New guidelines for water reuse’, official website, available on https://www.interregeurope.eu/policy-learning-platform/news/new-guidelines-for-water-reuse, (accessed ). 7 April.

- Giakoumatos, S.D.V. , Gkionakis, A.K.T. Development of an Ontology-Based Knowledge Network by Interconnecting Soil/Water Concepts/Properties, Derived from Standards Methods and Published Scientific References Outlining Infiltration/Percolation Process of Contaminated Water. J Geosci Environment Protection 2021, 9, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, K.B.W.; El-Shafie, A.; Othman, F.; Khan, M.M.H.; Birima, A.H.; Ahmed, A.N. Groundwater level forecasting with machine learning models: A review. Water Res 2024, 252, 121249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, C.; Farahin, N.; Mohd, N.S.; Koting, S.; Ismail, Z.; Sherif, M.; El-Shafie, A. Groundwater Quality Forecasting Modelling Using Artificial Intelligence: A Review. Groundwater for Sustainable Development 2021, 14, 100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Hameed, M.M.; Marhoon, H.A.; Zounemat-Kermani, M.; Heddam,S. ; Kim S.; Sulaiman, S.O.; Tan, M.L.; Saadi, Z.; Mehr, A.D.; Allawi, M.F.; Abba, S.I.; Zain, J.M.; Falah, M.W.; Jamei, M.; Bokde, N.D.; Bayatvarkeshi, M.; Al-Mukhtar, M.; Bhagat, S.K.; Tiyasha, T.; Khedher, K.M.; Al-Ansari, N.; Shahid, S.; Yaseen, Z.M. Groundwater level prediction using machine learning models: A comprehensive review. Neurocomputing 2022, 489, 271–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizamir, M.; Kazemi, Z.; Kermani, M.; Kim, S.; Heddam, S.; Kisi, O.; Chung, I.-M. Investigating Landfill Leachate and Groundwater Quality Prediction Using a Robust Integrated Artificial Intelligence Model: Grey Wolf Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithm and Extreme Learning Machine. Water 2023, 15, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Luo, D.; Tan, J.; Li, S.; Song, X.; Xiong, R.; Wang, J.; Ma, C.; Xiong, H. Spatial Mapping and Prediction of Groundwater Quality Using Ensemble Learning Models and SHapley Additive exPlanations with Spatial Uncertainty Analysis. Water 2024, 16, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. ; Groundwater Resources Management through the Applications of Simulation Modeling: A Review. Science of The Total Environment 2014, 499, 414–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, F.; Alizadeh, A.; Rashchi, F.; Mostoufi, N. Kinetics of leaching: a review. Reviews in Chemical Engineering 2022, 38, 113–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, L.R.; Ma, L.; Howell, A.T. Agricultural system models in field research and technology transfer, Lewis Publishers, CRC press, US, 2002.

- Tsakiris, G.; Alexakis, D. , Water quality models: An overview., European Water- E.W. Publications 2012, 37, 33-46. https://www.ewra.net/ew/pdf/EW_2012_37_04. 7 April.

- Omar, P.J.; Gaur, S.; Dwivedi, S.B.; et al. Groundwater modelling using an analytic element method and finite difference method: An insight into Lower Ganga river basin. J Earth Syst Sci. 2019, 128, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamin, P.; Cochand, M.; Dagenais, S. , et al. Direct measurement of groundwater flux in aquifers within the discontinuous permafrost zone: an application of the finite volume point dilution method near Umiujaq (Nunavik, Canada). Hydrogeol J, 2020, 28, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathania, T.; Bottacin-Busolin, A.; Rastogi, A.K.; et al. Simulation of Groundwater Flow in an Unconfined Sloping Aquifer Using the Element-Free Galerkin Method. Water Resour Manage 2019, 33, 2827–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Liang, T. Mapping pesticide contamination potential. Environ Manage 1989, 13, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltman, W.H.J.; Boesten, J.J.T.I.; van der Zee, S.E.A.T.M. Analytical modeling of pesticide transport from the soil surface to a drinking water well. J. Hydrol. 1995, 169, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, L.J.; Blauhut, V.; Bloomfield, J.P.; Cammalleri, C.; Engeland, K.; Everard, N.; Facer-Childs, K. , et al. Processes and Estimation Methods for Streamflow and Groundwater. In Hydrological Drought (2nd Edition), edited by Lena M. Tallaksen and Henny A.J. van Lanen, 2024. pp. xxiii–xxv. Elsevier, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, D.B.; Huggins, L.F.; Monke, E.J. ; ANWERS: a model for watershed planning. Trans. ASAE 1980, 23(4), 938–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knisel, W.G. CREAMS: A Field Scale Model for Chemicals, Runoff, and Erosion from Agricultural Management Systems. USDA Conservation Research Report, ttps://www.tucson.ars.ag.gov/unit/publications/PDFfiles/312.pdf (accessed 7 April 2024) 1980, 26, 36–64. [Google Scholar]

- Knisel, W.G.; Williams, J.R. ; Hydrology component of CREAMS and GLEAMS models. In: Singh, V.P. (Eds.). Computer Models of Watershed Hydrology, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, R.; Knisel, W.; Still, D. GLEAMS: Groundwater loading effects of agricultural management systems. Trans. ASAE 1987, 30, 1403–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, B.; Miralles, D.G.; Lievens, H.; van der Schalie, R.; de Jeu, R.A.M.; Fernández-Prieto, D.; Beck, H.E.; Dorigo, W.A.; Verhoest. N.E.C. GLEAM v3: Satellite-Based Land Evaporation and Root-Zone Soil Moisture. Geosci Model Dev. 2017, 10, 1903–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.G. , Williams, J.R., 1987. Validation of SWRRB—Simulator for Water Resources in Rural Basins. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 113, (2), 243–56. [CrossRef]

- Young, R.A.; Onstad, C.A.; Bosch, D.D.; Anderson, W. P. AGNPS: A Nonpoint-Source Pollution Model for Evaluating Agricultural Watersheds. J Soil Water Conserv 1989, 44, 2–168. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, J.D.; Jackson, C.R.; Wang, L. A Lumped Conceptual Model to Simulate Groundwater Level Time-Series. Environ Modell Softw 2014, 61, 229–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.R.; Snow, V.O.; Cichota, R.; Jolly, B.H. The effect of situational variability in climate and soil, choice of animal type and N fertilisation level on nitrogen leaching from pastoral farming systems around Lake Taupo, New Zealand. Agr Syst 2011, 104, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, I.R.; Chapman, D.F.; Snow, V.O.; Eckard, R.J.; Parsons, A.J.; Lambert, M.G.; Cullen, B.R. DairyMod and EcoMod: biophysical pasture simulation models for Australia and New Zealand. Aust J Exp Agr 2008, 48, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, K.; Bond, W.J.; Srikanthan, R.; Frost, A.J. Predicting the impact of climatic variability on deep drainage under dryland agriculture. In: Zerger, A., Argent, R.M. (Eds.), MODSIM 2005 International Congress on Modelling and Simulation. Modelling and Simulation Society of Australia and New Zealand, 2005; pp.1716–1722. https://www.mssanz.org.au/modsim05/papers/verburg.pdf, (accessed 7 April 2024).

- Li, C.; Frolking, S.; Frolking, T.A. A model of nitrous oxide evolution from soil driven by rainfall events: 1. Model structure and sensitivity. J. Geophys. Res. 97, 9759–9776. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Frolking, S.; Frolking, T.A. A model of nitrous oxide evolution from soil driven by rainfall events: 2. Model applications. J. Geophys. Res. 97, 9777–9783. [CrossRef]

- Giltrap, D.L.; Li, C.; Saggar, S. DNDC: a process-based model of greenhouse gas fluxes from agricultural soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010, 136, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhespy, S.L.; Anthony, S.; Cardenas, L.; Chadwick, D.; del Prado, A.; Li, C.S.; Misselbrook, T.; Rees, R.M.; Salas, W.; Sanz-Cobena, A.; Smith, P.; Tilston, E.L.; Topp, C.F.E.; Vetter, S.; Yeluripati, J.B. First 20 years of DNDC (DeNitrification DeComposition): model evolution. Ecol. Modell. 2014, 292, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Farahbakhshazad, N.; Jaynes, D.B.; Dinnes, D.L.; Salas, W.; McLaughlin, D. Modeling nitrate leaching with a biogeochemical model modified based on observations in a row-crop field in Iowa. Ecol. Modell. 2006, 196, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Zhu, B.; Zhou, Z.; Zheng, X.; Li, C.; Wang, T.; Tang, J. Modeling nitrogen loadings from agricultural soils in southwest China with modified DNDC. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2011, 116 (G2). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Deng, J.; Wang, L. Assessing impacts of nitrogen management on nitrous oxide emissions and nitrate leaching from greenhouse vegetable systems using a biogeochemical model. Geoderma. 2021, 382, 114701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Grosso, S.J.; Parton, W.J.; Keough, C.A.; Reyes-Fox, M. Special features of the DayCent modeling package and Additional Procedures for Parameterization, Calibration, Validation, and applications. In Chapter 5, Methods of introducing system models into agricultural research. Vol II. Advances in Agricultural Systems. Ahuja, L., Ma, L. (Eds.), Modeling Series 2, Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2011. pp. 155-176. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liao, K.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, X.; Yang, J.; Huang, J. Determining the hot spots and hot moments of soil N2O emissions and mineral N leaching in a mixed landscape under subtropical monsoon climatic conditions. Geoderma 2022, 420 115896. [CrossRef]

- Francés, F.; Vélez, J.I.; Vélez, J.J. , Split-parameter structure for the automatic calibration of distributed hydrological models. J. Hydrol. 2007, 332, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertes, C.; Bautista, I.; Lidón, A.; Francés, F. Best management practices scenario analysis to reduce agricultural nitrogen loads and sediment yield to the semiarid Mar Menor coastal lagoon (Spain). Agric. Syst. 2021, 188, 103029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, G.H.; Samani, Z.A. Reference crop evapotranspiration from ambient air temperature. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 1985, 85, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap, M.G.; Leij, F.J.; van Genuchten, M.T. Rosetta: A computer program for estimating soil hydraulic parameters with hierarchical pedotransfer function. J. Hydrol. 2001, 251, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, S.; Francés, F.; et al. Impact of a transformation from flood to drip irrigation on groundwater recharge and nitrogen leaching under variable climatic conditions. Sci Total Environ 2022, 825, 153805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brisson, N.; Mary, B.; Ripoche, D.; Jeuffroy, M.H.; Ruget, F.; Nicoullaud, B.; Gate, P.; Devienne-Barret, F.; Antonioletti, R.; Durr, C.; Richard, G.; Beaudoin, N.; Recous, S.; Tayot, X.; Plenet, D.; Cellier, P.; Machet, J.M.; Meynard, J.M.; Delecolle, R. STICS: a generic model for the simulation of crops and their water and nitrogen balances. I. Theory and parameterization applied to wheat and corn. Agronomie 1998, 18, (5-6), 311–346. [CrossRef]

- Brisson, N.; Launay, M.; Mary, B.; Beaudoin, N. Conceptual Basis, Formalizations and Parameterization of the STICS Crop Model. Ed. Quae, France, 2009, pp. 297 available on file:///C:/Users/Administrator/Downloads/extrait_conceptual-basis-formalisations-and-paramet%20(1).pdf.

- Plaza-Bonilla, D.; Nolot, J-M. ; Raffaillac, D.; Justes, E. Cover Crops Mitigate Nitrate Leaching in Cropping Systems Including Grain Legumes: Field Evidence and Model Simulations. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 212, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, N.; Lecharpentier, P.; Ripoche, D.; Strullu, L.; Mary, B.; Leonard, J.; et al. (Eds.) , STICS Soil-Crop Model. Conceptual Framework, Equations and Uses. Versailles, éditions Quæ, 516 p., France, 2022. Available on file:///C:/Users/Administrator/Downloads/9782759236794%20(1).pdf.

- Delandmeter, et al. A comprehensive analysis of CO2 exchanges in agro-ecosystems based on a generic soil-crop model-derived methodology. Agr. Forest. Meteorol. 2023, 340, 109621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, J.; Willaume, M.; Murgue, C.; Lacroix, B.; Therond, O. The soil-crop models STICS and AqYield predict yield and soil water content for irrigated crops equally well with limited data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 206, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribouillois, H.; Constantin, J.; Guillon, B.; Willaume, M.; Aubrion, G.; Fontaine, A.; Hauprich, P.; Kerveillant, P.; Laurent, F.; Therond, O. AqYield-N: A simple model to predict nitrogen leaching from crop fields. Agr. Forest. Meteorol. 2020, 84, 107890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baveye, P.C. Ecosystem-scale modelling of soil carbon dynamics: Time for a radical shift of perspective? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 184, 109112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Yang, M.; Hou, Y.; Peng, C.; Wu, H.; Zhu, Q.; Liang, Q.; Xie, J.; Wang, M. Simulating soil water and soil nitrate contents, crop biomass and N acquired, allowing water drainage and nitrate leaching fluxes to be modelled with confidence. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 697, 134054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Peng, C.; Moore, T.R.; Hua, D.; Li, C.; Zhu, Q.; Peichl, M.; Arain, M.A.; Guo, Z. Modeling dissolved organic carbon in temperate forest soils: TRIPLEX-DOC model development and validation. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 867–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.G.; Srinivasan, R.; Muttiah, R.S.; Williams, J.R. Large area hydrologic modeling and assessment Part I: model Development. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1998, 34, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, J.M. and Brown, C.D. (1996). A catchment scale model for pesticides in surface waters. In: A.A.M. del Re, E. Capri, S.P. Evans, and M. Trevisan (Eds.) The Environmental Fate of Xenobiotics, Proceedings of the X Symposium Pesticide Chemistry, Castelnuovo Fogliani, Piacenza, Italia, La Goliardica Pavese, Pavia, Italy, September 30 - October 2 1996, pp. 371- 379.

- Qiu, H.; Qi, J.; Lee, S.; Moglen, G.E.; McCarty, G.W.; Chen, M.; Zhang, X. Effects of temporal resolution of river routing on hydrologic modeling and aquatic ecosystem health assessment with the SWAT model. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2021, 146, 105232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Carpena, R.; Parsons, J.E.; Gilliam, J.W. Modeling hydrology and sediment transport in vegetative filter strips. J. Hydrol. 1999, 214(1), 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.; Zamora-Re, M.; Graham, W.; Dukes, M.; Kaplan, D. Quantifying nitrate leaching to groundwater from a corn-peanut rotation under a variety of irrigation and nutrient management practices in the Suwannee River Basin, Florida. Agr. Water Manage. 2021, 246, 106634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chen, L.; Wei, G.; Shen, Z. New framework for optimizing best management practices at multiple scales. J. Hydrol. 2019, 578, 124133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbaugh, A.W.; Banta, E.R.; Hill, M.C.; McDonald, M.G. MODFLOW-2000, The U.S. Geological Survey Modular Ground-Water Model - User Guide to Modularization Concepts and the Ground-Water Flow Process, Report 2000-92, USGS Numbered Series. 2000. http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/ofr200092, (access 7 April 2024).

- Aliyari, F.; Bailey, T.R.; Tasdighi, A.; Dozier, A.; Arabi, M.; Zeiler, K. Coupled SWAT-MODFLOW model for large-scale mixed agro-urban river basins. Environ. Model. Softw. 2019, 115, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Bailey, T.R.; Records, M.R.; Wible, C.T.; Arabi, M. Comprehensive simulation of nitrate transport in coupled surface-subsurface hydrologic systems using the linked SWAT-MODFLOW-RT3Dmodel. Environ. Model. Softw. 2019, 122, 104242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.W.; Hoogenboom, G.; Porter, C.H.; Boote, K.J.; Batchelor, W.D.; Hunt, L.; Wilkens, P.W.; Singh, U.; Gijsman, A.J.; Ritchie, J.T. The DSSAT cropping system model. Eur. J. Agron. 2003, 1, 235–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimůnek, J.; van Genuchten, M.T.; Ŝejna, M. Development and applications of the HYDRUS and STANMOD software packages and related codes. Vadose Zone J. 2008, 7, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Fan, X.; Qi, Z.; Wan, L.; Hu, K. Simulation of water drainage and nitrate leaching at an irrigated maize (Zea mays L. ) oasis cropland with a shallow groundwater table, Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 355, 108573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA-ARS, Root zone water quality model version 1.0. Technical Documentation. GPSR Technical Report No. 2. USDA-ARS Great Plains Systems Research Unit. Ft. Collins, CO 1992.

- do-Rosário-Cameira, M. , Li, R., Fangueiro, DIntegrated modelling to assess N pollution swapping in slurry amended soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, J.; Wagenet, R. LEACHM (Leaching Estimation and Chemistry Model): A Process-Based Model of Water and Solute Movement, Transformations, Plant Uptake and Chemical Reactions in the Unsaturated Zone, Version 3.0, Department of Soil, Crop and Atmospheric Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 1992.

- Sophocleous, M.A.; Koelliker, J.K.; Govindaraju, R.S.; Birdie, T.; Ramireddygari, S.R.; Perkins, S.P. Integrated numerical modeling for basin-wide water management: the case of the Rattlesnake Creek basin in south-central Kansas. J. Hydrol. 1999, 214(1–4), 179–196. [CrossRef]

- Podlasek, A. Modeling Leachate Generation: Practical Scenarios for Municipal Solid Waste Landfills in Poland. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2023, 30, 13256–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, L.A. Capillary conduction of liquids through porous mediums. J. Appl. Phys. 1931, 1, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimůnek, J.; Sejna, M.; Saito, H.; Sakai, M.; van Genuchten, M.T. The HYDRUS-1D software package for simulating the movement of water, heat, and multiple solutes in variably saturated media, version 4.17, HYDRUS Software Series 3. USA: Dpt. of Environ. Sciences. University of California Riverside, Ca. USA, 2013.

- van Genuchten, M.T. A closed-form equation for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 1980, 44, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniruzzaman, M.; Pedretti, D. Mechanistic models supporting uncertainty quantification of water quality predictions in heterogeneous mining waste rocks: a review. Stoch Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2021, 35, 985–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimůnek, J.; van Genuchten, M.T.; Šejna, M. The HYDRUS software package for simulating two-and three-dimensional movement of water, heat, and multiple solutes in variably-saturated media. Tech-man version 2.0, 1, 260, 2012.

- Liu, F.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lai, X.; Liao, K. ; Guo, CStorages and leaching losses of soil water dissolved CO2 and N2O on typical land use hillslopes in southeastern hilly area of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023a 886, 163780. [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Prentice, I.C.; Sykes, M.T. Representation of vegetation dynamics in the modelling of terrestrial ecosystems: comparing two contrasting approaches within European climate space. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2001, 10, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, K.; Rao, S.; Krey, V.; et al. RCP 8.5—A scenario of comparatively high greenhouse gas emissions. Climatic Change, 2011, 109, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanke, J.H.; Olin, S.; Stürck, J.; Sahlin, U.; Lindeskog, M.; Helming, J.; Lehsten, V. Assessing the impact of changes in land-use intensity and climate on simulated trade-offs between crop yield and nitrogen leaching. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 239, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelil, S.; Henine, H.; Chaumont, C.; Tournebize, J. NIT-DRAIN model to simulate nitrate concentrations and leaching in a tile-drained agricultural field, Agr. Water Manage. 2022, 271, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemeŝ, V. Operational testing of hydrological simulation models. Hydrol. Sci. J. 1986, 31, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beegum, S.; Timlin, D.; Reddy, K.R.; et al. Improving the cotton simulation model, GOSSYM, for soil, photosynthesis, and transpiration processes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mc Kinion, J.M.; Baker, D.N.; Whisler, F.D.; Lambert, J.R. Application of the GOSSYM/COMAX system to cotton crop management. Agr. Syst. [CrossRef]

- Running, S.W.; Hunt, E.R.J. Generalization of a forest ecosystem process model for other biomes, BIOME-BGC, and an application for global-scale-models. In: Scaling Processes Between Leaf and the Globe. Ehleringer, J., Field, C. Eds.; Academic Press, San Diego, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 141–157,. [CrossRef]

- White, M.A.; Thornton, P.E.; Running, S.W.; Nemani, R.R. Parameterization and sensitivity analysis of the BIOME-BGC terrestrial ecosystem model: net primary production controls. Earth Interact. 2000, 4, 1–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesi, M.; Maselli, F.; Moriondo, M.; Fibbi, L.; Bindi, M.; Running, S.W. Application of BIOME-BGC to Simulate Mediterranean Forest Processes. Ecol. Model. 2007, 206, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.S.; Reynolds, J.F.; Maestre, F.T.; Li, F.M. Hydrological and ecological responses of ecosystems to extreme precipitation regimes: A test of empirical-based hypotheses with an ecosystem model. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 2016, 22, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.; Abrahamsen, P.; Petersen, C.T.; Styczen, M. Daisy: model use, calibration, and validation. T. ASABE 2012b 55, 1317–1335. [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsen, P.; Hansen, S. Daisy: an open soil-crop-atmosphere system model. Environ. Model. Softw. 2000, 15, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, H.A.R. From Penman to Makkink, In Hooghart, C. (Eds.), Evaporation and Weather, Proceedings and Information. Comm. Hydrological Research TNO, The Hague. 1987, pp. 5-30.

- Børgesen, C.D.; Pullens, J.W.M.; Zhao, J.; Blicher-Mathiesen, G.; Sørensen, P.; Olesen, J.E. NLES5 – An empirical model for estimating nitrate leaching from the root zone of agricultural land. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 134, 126465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mualem, Y. , 1976. A new model for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated porous media. Water Resour. Res. 12, 513–522. [CrossRef]

- van Genuchten, M.T.; Leij, F.J.; Yates, S.R. In: The RETC Code for Quantifying the Hydraulic Functions of Unsaturated Soils. Agency, EPA/600/2-91/065, USDA, Agricultural Research Service. Riverside, California 1991, 9250, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, K.A.; Pullens, J.W.M.; Børgesen, C.D. Optimized number of suction cups required to predict annual nitrate leaching under varying conditions in Denmark. J. Environ. Manage. 2023, 328, 116964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refsgaard, J.C.; Thorsen, M.; Jensen, J.B.; Kleeschulte, S.; Hansen, S. Large Scale Modelling of Groundwater Contamination from Nitrate Leaching. J. Hydrol. 1999, 221(3–4), 117–40s. [CrossRef]

- Holzworth, D.P.; et al. APSIM – evolution towards a new generation of agricultural systems simulation. Environ. Model. Softw., 2014, 62, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reading, L.P.; Bajracharya, K.; ·Wang, J. Simulating deep drainage and nitrate leaching on a regional scale: implications for groundwater management in an intensively irrigated area. Irrigation Sci. 2019, 37, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogeler, I.; Hansen, E.M.; Thomsen, I.K. The effect of catch crops in spring barley on nitrate leaching and their fertilizer replacement value. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 343, 108282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorburn, P.J.; Biggs, J.S.; Attard, S.J.; Kemei, J. Environmental impacts of irrigated sugarcane production: nitrogen lost through runoff and leaching. Agric Ecosyst Environ., 2011, 144, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, E.; Thorburn, P. Long term sugarcane crop residue retention offers limited potential to reduce nitrogen fertilizer rates in Australian wet tropical environments. Front Plant Sci. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.M.; Eriksen, J.; Søegaard, K.; Kristensen, K. Effects of grazing strategy on limiting nitrate leaching in grazed grass-clover pastures on coarse sandy soil. Soil Use Manage. 2012a 28, 478–487. [CrossRef]

- Vogeler, I.; Hansen, E.M.; Nielsen, S.; Labouriau, R.; Cichota, R.; Olesen, J.E.; Thomsen, I. K. Nitrate leaching from suction cup data: influence of method of drainage calculation and concentration interpolation. J. Environ. Qual. 2020, 49, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, P.E. CoupModel: model use, calibration, and validation. Trans. ASABE 2012, 55, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, J.L. Evaporation and environment. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1965, 19, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rappe-George, M.O.; Hansson, L.J.; Ring, E. , Jansson, P. E.; Gärdenäs, A.I. Nitrogen leaching following clear-cutting and soil scarification at a Scots pine site – A modelling study of a fertilization experiment. Forest Ecology and Management, 2017, 385, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, M.J.; Halvorson, A.D.; Pierce, F.J. Nitrate leaching and economic analysis package (NLEAP): model description and application. In Managing Nitrogen for Groundwater Quality and Farm Profitability, Follett, R.F., Keeney, D.R., Cruse, R.M. Eds., Soil Sci. Soc. Am., Madison, WI, 1991, pp. 285–322. [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.A.; Shaffer, M.; Brodahl, M.K. New NLEAP for shallow and deep-rooted rotations. J. Soil Water Conserv 1998 53 (4), 338–340.

- De Paz, J.M.; Delgado, J.A.; Ramos, C.; Shaffer, M.J.; Barbarick, K.K. Use of a new GIS nitrogen index assessment tool for evaluation of nitrate leaching across a Mediterranean region. J. Hydrol. 2009, 365, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, M.J.; Delgado, J.A.; Gross, C.; Follett, R.F.; Gagliardi, P. Simulation processes for the nitrogen loss and environmental assessment package. In Advances in Nitrogen Management for Water Quality; Delgado, J.A., Follett, R.F. Eds.; SWCS, Ankeny, IA, USA, 2010; pp. 362–373.

- Qiu, J.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Tang, H.; Li, C.; Van Ranst, E. GIS-model based estimation of nitrogen leaching from croplands of China. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2011, 90, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, L.; Qiu, J.; Li, C.; Gao, M.; Gao, C. Calibration of DNDC model for nitrate leaching from an intensively cultivated region of Northern China. Geoderma. 2014. 223–225, 108–118. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wen, X.; Hu, C.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Hu, B. Regional simulation of nitrate leaching potential from winter wheat-summer maize rotation croplands on the North China Plain using the NLEAP-GIS model. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020a 294, 106861. [CrossRef]

- Lyra, A.; Loukas, A.; Sidiropoulos, P.; Voudouris, K.; Mylopoulos, N. Integrated Modeling of Agronomic and Water Resources Management Scenarios in a Degraded Coastal Watershed (Almyros Basin, Magnesia, Greece). Water, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukas, A.; Mylopoulos, N.; Vasiliades, L. A modeling system for the evaluation of Water Resources Management Strategies in Thessaly, Greece. Water Resour. Manage. 2007, 21, 1673–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzabiras, J.; Vasiliades, L.; Sidiropoulos, P.; Loukas, A.; Mylopoulos, N. Evaluation of Water Resources Management Strategies to Overturn Climate Change Impacts on Lake Karla Watershed. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 30, 5819–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliades, L.; Mastraftsis, I. A Monthly Water Balance Model for Assessing Streamflow Uncertainty in Hydrologic Studies. In 7th International Electronic Conference on Water Sciences, 15–30 March 2023, 25, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.R.; Renard, K.G.; Dyke, P.T. EPIC: a new method for assessing erosion’s effect on soil productivity. J. Soil Water Conserv. 1983, 38, 381–383. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, A.N.; Williams, J.R. EPIC, Erosion/Productivity Impact Calculator: 1. Model Documentation (Technical Bulletin No. 1768). USDA, Agricultural Research Service, Springfield, Va., USA, 1990, pp. 235. https://agrilife.org/epicapex/files/2015/05/EpicModelDocumentation.pdf, (access 7 April 2024).

- Zheng, C. , Wang, P.P. MT3DMS:A Modular Three-Dimensional Multi-Species Transport Model for Simulation of Advection, Dispersion and Chemical Reactions of Contaminants in Groundwater Systems, Documentation and User’s Guide, Report Contract Report SERDP-99-1, U.S.Army Engineer Research and Development Center, Vicksburg, MS. 1999. https://hdl.handle.net/11681/4734.

- Guo, W.; Langevin, C.D. User’s guide to SEAWAT: a computer program for simulation of three-dimensional variable-density ground-water flow, Report 06-A7, 2002. http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/twri06A7, (access 7 April 2024).

- Galbiati, L.; Bouraoui, F.; Elorza, F.J.; Bidoglio, G. Modeling Diffuse Pollution Loading into a Mediterranean Lagoon: Development and Application of an Integrated Surface–Subsurface Model Tool. Ecol. Model. 2006, 193(1–2), 4–18. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martín, M.Á. Understanding Nutrient Loads from Catchment and Eutrophication in a Salt Lagoon: The Mar Menor Case. Water, 2023, 15, 3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martín, M.Á.; Arora, M.; Monreal, E.T. Defining the maximum nitrogen surplus in water management plans to recover nitrate polluted aquifers in Spain, J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 356, 120770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, K.; Waagepetersen, J.; Børgesen, C.D.; Vinther, F.P.; Grant, R.; Blicher-Mathiesen, G. Reestimation and further development in the model N-LES - N-LES3 to N-LES4: Aarhus Universitet. DJF, Plant Science 2008, 139. https://pure.au.dk/portal/en/publications/reestimation-and-further-development-in-the-model-n-les-n-lessub3-2, (access 7 April 2024).

- Yin, X.; et al. Performance of process-based models for simulation of grain N in crop rotations across Europe. Agric. Syst. 2017, 154, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.D.; Ahuja, L.R.; Shaffer, M.D.; Rojas, K.W.; DeCoursey, D.G.; Farahani, H.; Johnson, K. RZWQM: Simulating the effects of management on water quality and crop production, Agr. Syst. 1998, 57(2), 161–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, N.D.; Nguyen, Q.B.; Le, C.H.; Doan, T.D.; Le, V.H.; Gourbesville, P. Comparing Model Effectiveness on Simulating Catchment Hydrological Regime. In Advances in Hydroinformatics, Gourbesville, P., Cunge, J., Caignaert, G., Eds.; Springer Water. Springer, Singapore, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Skaggs, R.W.; Fausey, N. R.; Nolte, B.H. Water management evaluation for north central Ohio. T. ASAE 1981, 24(4), 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaggs, R.W.; Youssef, M.; Chescheir, G.M. DRAINMOD: model use, calibration, and validation. Trans. ASABE 2012, 55, 1509–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ale, S.; Gowda, P.H.; Mulla, D.J.; Moriasi, D.N.; Youssef, M.A. Comparison of the performances of DRAINMOD-NII and ADAPT models in simulating nitrate losses from subsurface drainage systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 129, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, M. DRAINMOD-P: A Model for Simulating Phosphorus Dynamics and Transport in Artificially Drained Agricultural Lands. North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA, 2019.

- El-Sadek, A. Upscaling field scale hydrology and water quality modelling to catchment scale. Water Resour. Manag. 2007, 21, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, A.A.; Hansen, I.S. Numerical models in water quality management: a case study for the Yamuna river (India). Water Sci. Technol. [CrossRef]

- Al-Adhaileh, M.H.; Aldhyani, T.H.H.; Alsaade, F.W.; Al-Yaari, M.; Albaggar, A.A. Groundwater Quality: The Application of Artificial Intelligence, Journal of Environmental and Public Health 2022, 8425798, 14. 8425798. [CrossRef]

- Ejigu, M. Overview of water quality modeling. Cogent Engineering 2021, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.A.; Landis, A.E.; Theis, T.L. Use of Monte Carlo Analysis to Characterize Nitrogen Fluxes in Agroecosystems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 2324–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.Z.; et al. Offsite transport of pesticides in water: Mathematical models of pesticide leaching and runoff. Pure Appl. Chem. 1995, 67, 2109–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekofteh, H.; Afyuni, M.; Hajabbasi, M.A.; Iversen, B.V.; Nezamabadi-pour, H.; Abassi, F.; Sheikholeslam, F. Nitrate leaching from a potato field using adaptive network-based fuzzy inference system. J. Hydroinform. 2013, 15, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remesan, R.; Mathew, J. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence-Based Approaches. In Hydrological Data Driven Modelling. Earth Systems Data and Models, vol 1. Springer, Cham. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Hanoon, M.S.; Ahmed, A.N.; Fai, C.M.; et al. Application of Artificial Intelligence Models for modeling Water Quality in Groundwater: Comprehensive Review, Evaluation and Future Trends. Water Air Soil Poll. 2021, 232, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggerty, R.; Sun, J.; Yu, H.; Li, Y. Application of machine learning in groundwater quality modeling -A comprehensive review, Water Res. 2023, 233, 119745. 233. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Yaseen, Z.M.; Scholz, M.; Ali, M.; Gad, M.; Elsayed, S.; Khadr, M.; et al. Evaluation and Prediction of Groundwater Quality for Irrigation Using an Integrated Water Quality Indices, Machine Learning Models and GIS Approaches: A Representative Case Study. Water 2023, 15, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Magd, A.; Ahmed, Sh.; Ismael, I.S.; El-Sabri, M.A.S.; Abdo, M.S.; Farhat, H.I. Integrated Machine Learning–Based Model and WQI for Groundwater Quality Assessment: ML, Geospatial, and Hydro-Index Approaches. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2023, 30, 53862–53875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Mao, J.; Mohiuddin, K.M. Artificial neural networks: a tutorial. Computer 1996, 29(3), 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besaw, L.E.; Rizzo, D.M. Counterpropagation neural network for stochastic conditional simulation: an application with Berea Sandstone. In Seventh IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW New York, 2007.

- Wagh, V.M.; Panaskar, D.B.; Muley, A.A. Estimation of nitrate concentration in groundwater of Kadava River basin-Nashik District, Maharashtra, India by using artificial neural network model. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2017, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunayana, K.K.; Dube, O.; Sharma, R. Use of neural networks and spatial interpolation to predict groundwater quality. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 2801–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaqoot, H.A.; Hamada, M.; Miqdad, S. A comparative study of Ann for predicting nitrate concentration in groundwater Wells in the southern area of Gaza strip. Applied Artificial Intelligence. [CrossRef]

- Fallah-Mehdipour, E.; Bozorg Haddad, O.; Marino, M.A. Real-time operation of reservoir system by genetic programming. Water Resour. Manage. 2012, 26(14), 4091–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isazadeh, M.; Biazar, S.M.; Ashrafzadeh, A. Support vector machines and feedforward neural networks for spatial modeling of groundwater qualitative parameters. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76(17), 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, M.A. Classifier Ensemble Method for Fuzzy Classifiers. In Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery. FSKD Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Wang, L., Jiao, L., Shi, G., Li, X., Liu, J. Eds. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg. 2006; 4223, pp. 784–793. [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.; Gaagai, A.; Agrama, A.A.; Walaa, F.M.; et al. Comprehensive evaluation and prediction of groundwater quality and risk indices using quantitative approaches, multivariate analysis, and machine learning models: An exploratory study, Heliyon 2024, 10, e36606. 10. [CrossRef]

- DeCoursey, D.G.; Ahuja, L.R.; Hanson, J.; Shaffer, M.; Nash, R.; Rojas, K.W.; Hebson, C.; Hodges, T.; Ma, Q.; Johnsen, K.E.; Ghidey, F. 1992. Root zone water quality model, Version 1.0, Technical Documentation. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Great Plains Systems Research Unit, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

- Ma, L.; Ahuja, L.R.; Ascough, J.C.; Shaffer, M.J.; Rojas, K.W.; Malone, R.W.; Cameira, M.R. Integrating System Modeling with Field Research in Agriculture: Applications of the Root Zone Water Quality Model (RZWQM), In Advances in Agronomy. Eds.; Academic Press, 2001, 71, 233–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, H.; Vanclooster, M.; Swerts, M.; Diels, J. Simulating nitrogen behaviour in soil cropped with winter wheat. Fert. Res. 1991, 27, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclooster, M.; Viaene, P.; Diels, J. 1994. WAVE—a mathematical model for simulating agrochemicals in the soil and vadose environment. Reference and user’s manual (release 2.0). Institute for Land and Water Management, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium.

- Vanclooster, M.; Viaene, P.; Diels, J.; Feyen, J. A deterministic validation procedure applied to the integrated soil crop model. Ecol. Model. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.; Jensen, H.E.; Nielsen, N.E.; Svendsen, H. Simulation of nitrogen dynamics and biomass production in winter wheat using the Danish simulation model Daisy. Fert. Res. 1991, 27, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, L.R. , Johnsen, K.E.; Rojas, K.W. Water and chemical transport in soil matrix and macropores. In The Root Zone Water Quality Model, Ahuja, L.R., Rojas, K.W., Hanson, J.D., Shaffer, M.J., Ma, L. Eds., Highlands Ranch, Colo.: Water Resources Publications, 2000; pp. 13–50. [Google Scholar]

- Flerchinger, G.N.; Aiken, R.M.; Rojas, K.W.; Ahuja, L.R.; Johnsen, K.E.; Alonso, C.V. Soil heat transport, soil freezing, and snowpack conditions. In The Root Zone Water Quality Model, Ahuja, L.R., Rojas, K.W., Hanson, J.D., Shaffer, M.J., Ma, L., Eds. Highlands Ranch, Colo.: Water Resources Publications, 2000; pp.281-314.

- Hanson, J.D. , Generic crop production model for the Root Zone Water Quality Model. In The Root Zone Water Quality Model, Ahuja, L.R., Rojas, K.W., Hanson, J.D., Shaffer, M.J., Ma, L. Eds. Highlands Ranch, Colo.: Water Resources Publications, 2000; pp. 81-118.

- Shaffer, M.J.; Rojas, K.W.; DeCoursey, D.G.; Hebson, C.S. Nutrient chemistry processes: OMNI. In The Root Zone Water Quality Model, Ahuja, L.R., Rojas, K.W., Hanson, J.D., Shaffer, M.J., Ma, L., Eds. Highlands Ranch, Colo.: Water Resources Publications. 2000a; pp. 119-144.

- Shaffer, M.J.; Rojas, K.W.; DeCoursey, D.G. The equilibrium soil chemistry process: SOLCHEM. In The Root Zone Water Quality Model, Ahuja, L.R., Rojas, K.W., Hanson, J.D., Shaffer, M.J., Ma, L., Eds. Highlands Ranch, Colo.: Water Resources Publications. 2000b; pp. 145-161.

- Farahani, H.J.; DeCoursey, D.G. , Evaporation and transpiration processes in the soil-residue-canopy system. In The Root Zone Water Quality Model, Ahuja, L.R., Rojas, K.W., Hanson, J.D., Shaffer, M.J., Ma, L. Eds. Highlands Ranch, Colo.: Water Resources Publications, 2000; pp. 51-80.

- Rojas, K.W.; Ahuja, L.R. Management practices. In The Root Zone Water Quality Model, Ahuja, L.R., Rojas, K.W., Hanson, J.D., Shaffer, M.J., Ma, L., Eds. Highlands Ranch, Colo.: Water Resources Publications 2002; pp. 45-280.

- Wauchope, R.D.; Rojas, K.W.; Ahuja, L.R.; Ma, Q.L.; Malone, R.W.; Ma. L. Documenting the pesticide processes module of the ARS RZWQM agroecosystem model. Pest Mgmt. Sci. 2004, 60, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinton, J. Marine Biology, 5th edition, Oxford University Press, ch. 11, 2018.

- Eby, G.N. Principals of Environmental Geochemistry, Thomson-Brooks/Cole, Australia, ch.9, 2004.

- Pferdmenges, J.; Breuer, L.; Julich, S.; Kraft, P. Review of soil phosphorus routines in ecosystem models. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2020, 126, 104639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhurst, D.L.; Appelo, C.A.J. 2013. Description of input and examples for PHREEQC version 3: a computer program for speciation, batch-reaction, one-dimensional transport, and inverse geochemical calculations. U.S. Geol. Surv. Tech. Methods, B. 6, Chapter A43. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Ζ. , et al. Integrated approach to hydrogeochemical appraisal of groundwater quality concerning arsenic contamination and its suitability analysis for drinking purposes using water quality index. Scientific Reports. Nature 2023, 13, 20455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, J. Calibration and Uncertainty Analysis for Complex Environmental Models. Eds.; Watermark Numerical Computing, Brisbane, Australia, 2015. https://s3.amazonaws.com/docs.pesthomepage.org/documents/pest_book_toc.pdf, (access 7 April 2024).

- Dzombak, D.A.; Morel, F.M.M. Surface Complexation Modeling: Hydrous Ferric Oxide. Wiley, New York, 1991. Available on https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Surface+Complexation+Modeling%3A+Hydrous+Ferric+Oxide-p-9780471637318, (access 7 April 2024).

- Tipping, E.; Hurley, M.A. A unifying model of cation binding by humic substances. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 1992, 56, 3627–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, S.; Le Forestier, L.; Bataillard, P.; Devau, N. Leaching of trace metals (Pb) from contaminated tailings amended with iron oxides and manure: New insight from a modelling approach. Chem. Geol. 2021, 579, 120356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Molinari, S.; Dalconi, M.C.; Valentini, L.; Ricci, G.; Carrer, C.; Ferrari, G.; Artioli, G. The leaching behaviors of lead, zinc, and sulfate in pyrite ash contaminated soil: mineralogical assessments and environmental implications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, J.P. Vis. MINTEQ 3. 1 Use Guide, Dep. L., Water Recources, Stock. Swed. 2011, 1, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, T.; Angioletto, E.; Quadri, M.B.; Cargnin, M.; de Souza, M.H. , Acceleration of acid mine drainage generation with ozone and hydrogen peroxide: Kinetic leach column test and oxidant propagation modeling. Min. Eng. 2022, 175, 107282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, T.; Angioletto, E.; Quadri, M.B.; Cardoso, W.A. Ozone propagation in sterile waste piles from uranium mining: Modeling and experimental validation. Transport Porous Med, 2019, 127, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carman, P.C. Fluid flow through granular beds. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 1997, 75, S32–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, M.A.; Rimstidt, J.D. The kinetics and electrochemical rate determining step of aqueous pyrite oxidation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 1994, 58, 5443–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, X.; Zhang, S. Construction modeling and parameter optimization of multistep horizontal energy storage salt caverns. Energy 2020b 203, 117840. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; An, G.; Shan, B.; Wang, W.; Jia, J.; Wang, T.; Zheng, X. Parameter Optimization of Solution Mining under Nitrogen for the Construction of a Gas Storage Salt Cavern. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 91, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuAisha, M.; Rouabhi, A. On the validity of the uniform thermodynamic state approach for underground caverns during fast and slow cycling. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2019, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tackie-Otoo, B.N.; Haq, M.B. A comprehensive review on geo-storage of H2 in salt caverns: Prospect and research advances. Fuel, 2024, 356, 129609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhurst, D.L.; Appelo, C.A.J. User’s Guide to PHREEQC (Version 2): A Computer Program for Speciation, Batch-Reaction, One-Dimensional Transport, and Inverse Geochemical Calculations. Report. Water-Resources Investigations Report. [CrossRef]

- Feizi, M.; Jalali, M. Leaching of Cd, Cu, Ni and Zn in a sewage sludge-amended soil in presence of geo- and nano-materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.L.; Henry, C.L.; Chaney, R.; Compton, H.; DeVolder, P.S. Using municipal biosolids in combination with other residuals to restore metal contaminated mining areas. Plant Soil 2003, 249, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, Q.; Jamro, I.A.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Luan, J. Geochemical modeling and assessment of leaching from carbonated municipal solid waste incinerator (MSWI) fly ash. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2016, 23, 12107–12119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Sloot, H.A. , Kosson, D.S., Van Zomeren, A., 2017. Leaching, geochemical modelling and field verification of a municipal solid waste and a predominantly non-degradable waste landfill. Waste Manag. 63, 74-95. [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Chan, W.P.; Dou, X.; Lisak, G.; Chang, V.W.C. Co-complexation effects during incineration bottom ash leaching via comparison of measurements and geochemical modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 189, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, K.; Lassabatere, L.; Bechet, B. Zinc and lead transfer in a contaminated roadside soil: experimental study and modeling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, A.J.; Eighmy, T.T.; Hjelmar, O.; Kosson, D.S.; Sawell, S.E.; Vehlow, J.; van der Sloot, H.A.; Vehlow, J. Studies in environmental science, 67 (chapter 15-Leaching modelling), Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Residues, the international ash working group (IAWG), Eds.; 1st ed., Elsevier, The Netherlands. 1997; Volume 67, pp. 607-636. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, W.; Guo, Y. Effect of integrating straw into agricultural soils on soil infiltration and evaporation. Water Sci. Technol. 2012, 65(12), 2213–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Li, Y.; Ma, X. Effects on Infiltration and Evaporation When Adding Rapeseed-Oil Residue or Wheat Straw to a Loam Soil. Water 2017, 9, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielina, M.; Bielski, A.; Młyńska, A. Leaching of chromium and lead from the cement mortar lining into the flowing drinking water shortly after pipeline rehabilitation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2020/2184 on the quality of water intended for human consumption. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32020L2184, (access 5 April 2024).

- Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Yang, F.; Wang, A. Study on properties of representative ordinary Portland cement: Heavy metal risk assessment, leaching release kinetics and hydration coupling mechanism. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 385, 131507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xu, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhao, B.; Li, L.; Qiang, Z. Dec. Modeling iron release from cast iron pipes in an urban water distribution system caused by source water switch. J. Environ. Sci.-China 2021, 110, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizarro, G.; Vargas, I.T.; Pastén, P.A.; Calle, G.R. Modeling MIC copper release from drinking water pipes. Bioelectrochemistry 2014, 97, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grugnaletti, M.; Pantini, S.; Verginelli, I.; Lombardi, F. An easy-to-use tool for the evaluation of leachate production at landfill sites. Waste Manage. 2016, 55, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J-E. ; Kim, M.; Kim, JY.; Park, I-S.; Park, J-W. Leachate modeling for a municipal solid waste landfill for upper expansion. KSCE J. Civil Eng. 2010, 14, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, P.R.; Aziz, N.; Lloyd, C.; Zappi, P. The Hydrologic Evaluation of Landfill Performance (HELP) model: User’s guide for version 3; EPA/600/R-94/168a; US-EPA, Office of Research and Development, Ci, Ohio, USA, 1994.

- Beck-Broichsitter, S.; Gerke, H.H.; Horn, R. Assessment of leachate production from a municipal solid-waste landfill through waterbalance modeling. Geosciences 2018, 8, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayer, M.J. UNSAT-H Version 3.0: Unsaturated Soil Water and Heat Flow Model: theory, user manual, and examples. Rep 13249. Battelle Pacific Northwest Laboratory, Hanford, Washington, USA, 2000. https://www.pnnl.gov/main/publications/external/technical_reports/PNNL-13249.pdf, (access 7 April 2024).

- Šimůnek, J.; van Genuchten, M.T.; Šejna, M. The HYDRUS-1D software package for simulating the one-dimensional movement of water, heat, and multiple solutes in variably-saturated media. Dpt. of Environ. Sciences, University of California Riverside, Riverside, Ca, USA, 2005. https://www.ars.usda.gov/arsuserfiles/20360500/pdf_pubs/P2119.pdf, (access 7 April 2024). 7 April.

- Diersch, H.J.G. FEFLOW, Finite Element Subsurface Flow and Transport Simulation System Reference Manual; DHI-WASY Ltd.: Berlin, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesania, F.A. Jennings, A. A hydraulic barrier design teaching module based on HELP 3.04 and HELP model for Windows v2. 05. Environ. Modell. Softw. 1998, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, P.; Mulla, D.; Desmond, E.; Ward, A.; Moriasi, D. ADAPT: Model use, calibration and validation. Transactions of the ASABE Soil Water & Science 2012, 55, 1345–1352, https://experts.umn.edu/en/publications/adapt-model-use-calibration-and-validation, (access 7 April 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Rijtema, P.E.; Kroes, G.J. Some results of nitrogen simulations with the model ANIMO. Fert. Res. 1991, 27, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenendijk, P.; Kroes, J.G. Modelling the Nitrogen and Phosphorus Leaching to Groundwater and Surface Water with ANIMO 3.5 (No. 144). Winand Staring Centre, Wageningen, 1999. https://edepot.wur.nl/363774, (access ). 7 April.

- Matinzadeh, M.M.; Koupai, J.A.; Sadeghi-Lari, A.; Nozari, H.; Shayannejad, M. Development of an Innovative Integrated Model for the Simulation of Nitrogen Dynamics in Farmlands with Drainage Systems Using the System Dynamics Approach. Ecol. Modell. 2017, 347, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Bingner, R.L.; Theurer, E.D.; Rebich, R.A.; Moore, P.A. Phosphorus component in AnnAGNPS. Trans. ASAE 2005, 48, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pease, L.M.; Oduor, P.; Padmanabhan, G. Estimating sediment, nitrogen, and phosphorous loads from the Pipestem Creek watershed, North Dakota, using AnnAGNPS. Comput. Geosci. 2010, 36, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraoui, F.; Dillaha, T.A. ANSWERS-2000: runoff and sediment transport model. J. Environ. Eng. ASCE 1996, 122, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraoui, F.; Dillaha, T.A. Answers-2000: non-point-source nutrient planning model. J. Environ. Eng. ASCE 2000, 126, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.A.; Cole, C.V.; Sharpley, A.N.; Williams, J.R. A simplified soil and plant phosphorus model: I. Documentation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1984, 48, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A.B.; Nelson, N.O.; Sweeney, D.W.; Baffaut, C.; Lory, J.A.; Senaviratne, A.; Pierzynski, G.M.; Janssen, K.A.; Barnes, P.L. Calibration of the APEX model to simulate management practice effects on runoff, sediment, and phosphorus loss. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 1332–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, W.I.; King, K.W.; Williams, M.R.; Confesor, R.B. Modified APEX model for simulating macropore phosphorus contributions to tile drains. J. Environ. Qual. 2017, 46, 1413–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.P.; Lu, W.X.; Long, Y.Q.; Li, P. Application and comparison of two prediction models for groundwater levels: a case study in Western Jilin Province, China. J. Arid Environ. 2009, 73(4–5), 487–492. [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.K.; Dunn, S.M.; Ferrier, R.C. A spatially-distributed conceptual model for reactive transport of phosphorus from diffuse sources: an object-oriented approach. Complex. Integr. Resour. Manag. 2004. 970.

- Koo, B.K.; Dunn, S.M.; Ferrier, R.C. A distributed continuous simulation model to identify critical source areas of phosphorus at the catchment scale: model description. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2005, 1359–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, W.J.; Scurlock, J.M.O.; Ojima, D.S.; Gilmanov, T.G.; Scholes, R.J.; Schimel, D.S.; Kirchner, T.; Menaut, J.C; Seastedt, T.; Garcia Moya, E.; Kamnalrut, A.; Kinyamario, J.I. Observations and modeling of biomass and soil organic matter dynamics for the grassland biome worldwide. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 1993, 7, 785–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. The DNDC Model. In Evaluation of Soil Organic Matter Models Powlson, D.S., Smith, P., Smith, J.U. Eds.; NATO ASI Series, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996, Volume 38, pp. 263-267. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.; Grant, B.; Qi, Z.; He, W.; Van der Zaag, A.; Drury, C.F.; Helmers, M. Development of the DNDC model to improve soil hydrology and incorporate mechanistic tile drainage: A comparative analysis with RZWQM2. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2020, 123, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, R.C.M.; Rotunno Filho, O.C.; Mansur, W.J.; Nobre, M.M.M.; Cosenza, C.A.N. Groundwater vulnerability and risk mapping using GIS, modeling and a fuzzy logic tool. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2007, 94, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqsoom, A.; Aslam, B.; Khalil, U.; Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Ashraf, H.; Faisal Tufail, R.; Farooq, D.; Blaschke, T. A GIS-Based DRASTIC Model and an Adjusted DRASTIC Model (DRASTICA) for Groundwater Susceptibility Assessment along the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) Route. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9 (5). [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, J.; de Ridder, N.A. , Numerical modelling of groundwater basins. ILRI Publication 29, Wageningen; The Netherlands, 1990.

- Peña-Haro, S.; Llopis-Albert, C.; Pulido-Velazquez, M.; Pulido-Velazquez, D. Fertilizer standards for controlling groundwater nitrate pollution from agriculture: El Salobral-Los Llanos case study, Spain. J. Hydrol 2010, 392(3–4), 174–187. [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zheng, X. Critical Review of Measures and Decision Support Tools for Groundwater Nitrate Management: A Surface-to-Groundwater Profile Perspective. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598: 126386. [CrossRef]

- Lyra, A.; Loukas, A.; Sidiropoulos, P.; Tziatzios, G.; Mylopoulos. N. An Integrated Modeling System for the Evaluation of Water Resources in Coastal Agricultural Watersheds: Application in Almyros Basin, Thessaly, Greece. Water 2021, 13, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudra, R.P.; Negi, S.C.; Gupta, N. Modelling Approaches for Subsurface Drainage Water Quality Management. Water Qual. Res. J. 2005, 40, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Merritt, W.S.; Croke, B.F.W.; Weber, T.R.; Jakeman, A.J. A review of catchment-scale water quality and erosion models and a synthesis of future prospects. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2019, 114, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acock, B.; Reddy, V.R.; Whisler, F.D.; Baker, D.N.; Hodges, H.F.; Boote, K.J. The soybean crop simulator GLYCIM, Model Documentation, PB, 851163/AS, US Dpt. Of Agriculture, Washington DC., available from NTIS, Springfield, VA, 1985.

- Diaz-Ramirez, J.; Martin, J.I.; William, H.M. ; Modelling phosphorus export from humid subtropical agricultural fields: a case study using the HSPF model in the Mississippi alluvial plain. J. Earth Sci. Climatic Change 2013, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Gao, J. , Yan, R. A Phosphorus Dynamic model for lowland Polder systems (PDP). Ecol. Eng. 2016, 88, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, P.; Simmons, C.T. HydroGeoSphere: a fully integrated, physically based hydrological model. Ground Water 2012, 50, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delottier, H.; Therrien, R.; Young, N.L.; Paradis, D. A Hybrid Approach for Integrated Surface and Subsurface Hydrologic Simulation of Baseflow with Iterative Ensemble Smoother. J. Hydrol. 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.L.; Donnelly, C.; Refsgaard, J.C.; Karlsson, I.B. Simulation of nitrate reduction in groundwater - an upscaling approach from small catchments to the Baltic Sea basin. Adv. Water Resour. 2018, 111, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, G.; Pers, C.; Rosberg, J.; Strömqvist, J.; Arheimer, B. Development and testing of the HYPE (Hydrological Predictions for the Environment) water quality model for different spatial scales. Hydrol. Res 2010, 41(3-4), 295–319. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, M.H.; Persson, K.; Ulen, B.; Lindsjo, A.; Jarvis, N.J. A dual porosity model to quantify phosphorus losses from macroporous soils. Ecol. Model. 2007, 205, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, D.; Jones, J.; Grant, G. An improved methodology for predicting the daily hydrologic response of ungauged catchments. Environ. Model. Softw. 1998, 13(3–4), 395–403. https, 7 April 2604. [Google Scholar]

- Croke, B.F.; Andrews, F.; Jakeman, A.J.; Cuddy, S.M.; Luddy, A. Software and data news: IHACRES Classic Plus: a redesign of the IHACRES rainfall-runoff model. Environ Model Softw. 2006, 21, 426–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, A.; Rixon, S.; Zeuner, C.; Levison, J.; Binns, A. Goel, P. , Text mining-aided meta-research on nutrient dynamics in surface water and groundwater: Popular topics and perceived gaps, J. Hydrol. 2023, Part B, 130338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Blake, L.A. , Wade, A.J.; Futter, M.N.; Butterfield, D.; Couture, R.-M.; Cox, B.A.; Crossman, J.; Ekholm, P.; Halliday, S.J.; Jin, L.; Lawrence, D.S.L.; Lepisto, A.; Lin, Y.; Rankinen, K.; Whitehead, P.G. The INtegrated CAtchment model of phosphorus dynamics (INCA-P): description and demonstration of new model structure and equations. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2016, 83, 356–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viney, N.R.; Sivapalan, M.; Deeley, D. A conceptual model of nutrient mobilisation and transport applicable at large catchment scales. J.Hydrol. [CrossRef]

- De Roo, A.; Wesseling, C.; Van Deursen, W. Physically based river basin modelling within a GIS: the LISFLOOD model. Hydrol Process 2000, 14(11–12), 1981–1992 . https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC16897, (access April 2024).

- McGechan, M.B.; Jarvis, N.J.; Hooda, P.S.; Vinten, A.J.A. Parameterization of the MACRO model to represent leaching of colloidally attached inorganic phosphorus following slurry spreading. Soil Use Manag. 2002, 18, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tediosi, A.; Whelan, M.J.; Rushton, K.R.; Gandolfi, C. Predicting rapid herbicide leaching to surface waters from an artificially drained headwater catchment using a one dimensional two-domain model coupled with a simple groundwater model, J. Contam. Hydrol. 2013, 145, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosby, B.J.; Ferrier, R.C.; Jenkins, A.; Wright, R.F. Modelling the effects of acid deposition: refinements, adjustments and inclusion of nitrogen dynamics in the MAGIC model. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2001, 5(3), 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, J.D.; Brown, D.S.; Novo-Gradac, K.J. MINTEQA2/PRODEFA2, A Geochemical Assessment Model for Environmental Systems: Version 3.0 User’s Manual. Environmental Research Laboratory, US EPA, Athens, GA, 1990.

- Chen, C.; He, W.; Zhou, H.; Xue, Y.R.; Zhu, M.D. A comparative study among machine learning and numerical models for simulating groundwater dynamics in the Heihe River Basin, northwestern China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neteler, M.; Mitasova, H. Open-Source GIS: A GRASS GIS approach. The Kluwer International Series in Engineering and Computer Science. 2nd ed. Boston, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2005, pp. 424. https://www.giscenter.ir/Content/File/Input/Document/Output_Attachment_CMS_Books-14010805-17.29.46.pdf, (access ). 7 April.

- Kunkel, R.; Wendland, F. The GROWA98 model for water balance analysis in large river basins—the river Elbe case study. J. Hydrol. 2002, 259, 152–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, M.J.; Larson, W.E. (Eds.) ; NTRM: a soil-crop simulation model for nitrogen, tillage, and crop-residue management. USDA-ARS Conservation Research Report 34-l. National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA, 1987.

- Seligman, N.G.; van Keulen, H. PAPRAN: A Simulation Model of Annual Pasture Production Limited by Rainfall and Nitrogen. In Frissel, M.J. and Van Veen, J.A., Eds., Simulation of Nitrogen Behaviour of Soil-Plant Systems, Pudoc, Wageningen, 1981, 192-220.

- Branger, F.; Tournebize, J.; Carluer, N.; Kao, C.; Braud, I.; Vauclin, M. A simplified modelling approach for pesticide transport in a tile-drained field: The PESTDRAIN model. Agric. Water Manag. 2009, 96, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhurst, D.L.; Wissmeier, L. PhreeqcRM: A reaction module for transport simulators based on the geochemical model PHREEQC. Adv. Water Resour. 2015, 83, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoumans, O.F.; Van der Salm, C.; Groenendijk, P. PLEASE: a simple model to determine P losses by leaching. Soil Use Manag. 2013, 29, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsel, R.F.; Smith, C.N.; Mulkey, L.A.; Dean, J.D.; Jowise, P.P. Users’ manual for the Pesticide Root Zone Model (PRZM): release 1. EPA Report 600/3-84-109. EPA, Athens, GA, 1984.

- Ma, L.; Ahuja, L.R.; Nolan, B.T.; Malone, R.W.; Trout, T.J.; Qi, Z. Root Zone Water Quality Model (RZWQM2): Model Use, Calibration, and Validation. Trans. ASABE 2012, 55, 1425–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavo, P.; Recous, S.; Parnaudeau, V.; Reau, R. Modeling N Dynamics to Assess Environmental Impacts of Cropped Soils. In: Advances in Agronomy, Publisher: Academic Press, 2008, 97, 131–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterbaan, RJ. SAHYSMOD (version 1.7a): description of principles, user manual and case studies. The Netherlands: International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement, Wageningen; 2005. p. 140.

- Querner, E.P. Description of a regional groundwater flow model SIMGRO and some applications. Agric. Water Manag. 1988, 14(1-4), 209–18. [CrossRef]

- Enders, A.; Vianna, M.; Gaiser, T.; Krauss, G.; Webber, H.; Srivastava, A.K.; Seidel, S.J.; Tewes, A.; Rezaei, E.E. ; Ewert. F. SIMPLACE—a Versatile Modelling and Simulation Framework for Sustainable Crops and Agroecosystems. In Silico Plants 5, no. 1: diad006, Eds.; Amy Marshall-Colon. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Johnsson, H.; Bergstrom, L.; Jansson, P.E. Simulated nitrogen dynamics and losses in a layered agricultural soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1987, 18, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, E.H.; Kharaka, E.K.; Gunter, W.D.; DeBraal, J.D. Geochemical Modelling of Water-Rock interactions using SOLMINEQ.88. In Chemical modelling of aqueous systems II. D.L. Melchior and Bassett D.L., Eds.; Publisher: ACS, Washington, DC. USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor, B.; Wu, K. Effects of equilibrium chemistry on leaching of contaminants from solidified/stabilized wastes. In Chemistry and microstructure of solidified waste forms. R.D. Spence. Eds.; Publisher: Lewis Publications, Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Babajimopoulos, C.; Panoras, A.; Georgoussis, H.; Arampatzis, G.; Hatzigiannakis, E.; Papamichail, D. Contribution to irrigation from shallow water table under field conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 2007, 92, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenhuis, T.S.; Bodnar, M.; Geohring, L.D.; Aburime, S.A.; Wallach, R. A simple model for predicting solute concentration in agricultural tile lines shortly after application. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 1997, 1, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjith, S.; Anand, V.; Shivapur, P.; Shiva, K.; Chandrashekarayya, G.; Hiremath, D. Water Quality Model for Streams: A Review. J. Environ. Prot. 2019, 10, 1612–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, P.F; Anthony, S.; Lord, E. Basin scale nitrate modelling using a minimum information requirement approach. In Water Quality: Processes and Policy, Trudgill S. Walling D, Webb B Eds.; Publisher: Wiley: Chichester; 1999, 101–117. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, P.F.; Beven, K.J. Spatial and temporal predictions of soil moisture dynamics, runoff, variable source areas and evapotranspiration for plynlimon, mid-wales. Hydrol. Process. 1993, 7, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, C.D.; Gates, T.K.; Bailey, R.T. Evaluating best management practices to lower selenium and nitrate in groundwater and streams in an irrigated river valley using a calibrated fate and reactive transport model. J. Hydrol. 2018, 566, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laflen, J.M.; Lane, L.J.; Foster, G.R. WEPP—a next generation of erosion prediction technology. J. S.W.C. 1991, 46, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, S.A.; Razali, R.; KuShaari, K.; Mansor, N.; Azeem, B.; Ford Versypt, A.N. A review of mathematical modeling and simulation of controlled-release fertilizers. J. Control. Release 2018, 271, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, M.; Li, T.; Lu, Y.; Liu, L. Controlled release urea improved crop yields and mitigated nitrate leaching under cotton-garlic intercropping system in a 4-year field trial. Soil Till. Res. 2018, 175, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Del Campo, M.A.; Esteller, M.V.; Morell, I.; Expósito, J.L.; Bandenay, G.L.; Díaz-Delgado, C. , A lysimeter study under field conditions of nitrogen and phosphorus leaching in a turf grass crop amended with peat and hydrogel. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borchard, N.; Schirrmann, M.; Cayuela, M.L.; Kammann, C.; Wrage-Mönnig, N.; Estavillo, J.M.; Fuertes-Mendizábal, T.; Sigua, G.; Spokas, K.; Ippolito, J.A.; Novak, J. Biochar, soil and land-use interactions that reduce nitrate leaching and N2O emissions: a meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2354–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotoli, M.; Epicoco, N.; Falagario, M. Multi-criteria decision-making techniques for the management of public procurement tenders: a case study. Appl. Soft. Comput. 2020, 88, 106064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model or platform/type | Pressure drivers/ Application | Porous medium | Data collection/input | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADAPT (extension of GLEAMS with DRAINMOD hydrological component) | Agricultural subsurface drainage for nutrient transport/ Macrospore flow transfer | [137,176,216] | ||

| AGNPS/ non-point source model, (lumped conceptual type) | Non-point pollution simulation resulting from agricultural activities | Watersheds | [32,102] | |

| ANFIS | Groundwater quality for irrigation using, prediction of irrigation water quality index (IWQI), soluble sodium percentage (SSP), sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), potential salinity (PS), Kelley index (KI) and residual sodium carbonate index (RSC) | Sandstone aquifer | On-site water sampling collection | [149] |

| ANIMO /mechanistic model | Nutrient leaching prediction and surface, ground water quality prediction, agri-environmental indicators testing, nitrogen transformation and leaching | Root zone | [176,217-219] | |

| ANN combined with SES-BiLSTM and SES-ANFIS models, (LMBP) and (MLP) algorithms, ANN combined with fuzzy logic | Water table depletion, saltwater intrusion wedge/ Water quality prediction in different groundwater, groundwater level prediction | Groundwater | On-site water sampling collection, preprocessing (SES) method for weight of the dataset and models’ output adjustment | [12-13,141,148] |

| AnnAGNPS | Phosphorus and nitrogen transport | Watersheds | [220-221] | |

| ANSWERS /lumped conceptual type | /Watershed, nutrient planning | [102] | ||

| ANSWERS2000 (incl. Green and Ampt infiltration model) | /Catchment scale, Surface runoff and sediment transport model, sediment loss | Water, soil | it uses 30-s time steps during runoff and switches to daily time steps between runoff events | [222-223] |

| APEX /single porosity approach | Sediment, and phosphorus loss/ phosphorus contributions to tile drains, management practice effects simulation on runoff, sediment, and phosphorus loss | Macropore soil, forestry | [224-226] | |

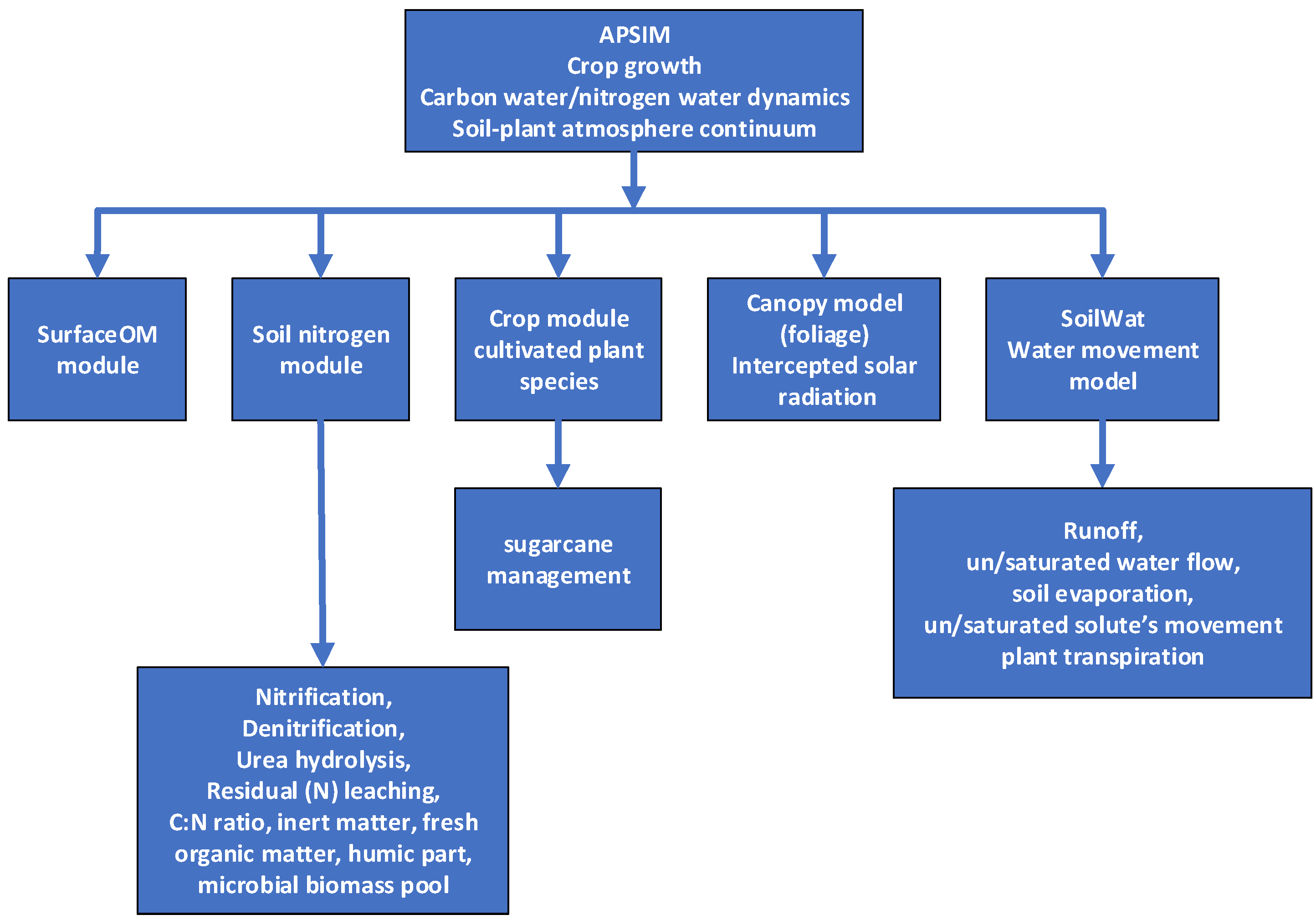

| APSIM various versions, biophysical, unsaturated zone model, incorp. modules for simulating specific crops, (use of Rosetta and PAWCER model) | Nitrate dynamics leaching in irrigated croplands/Crop yield and N uptake, nitrate leaching control, simulate impacts of environmental and agricultural management factors on deep drainage and nitrate leaching, controlling deep drainage and nitrate leaching | Crop field, paddock scale | SurfaceOM, SoilN, SoilWat, Canopy, Crop modules, soil properties data for particle size analysis, irrigation scheduling, annual rainfall, soil moisture content and chemical properties, runoff, soil evaporation, saturated hydraulic conductivity, water flow and content parameters, fraction of inert carbon, C:N ratio, organic matter content, air and dry water content, soil texture, drained upper limit | [103-104] |

| AquiMod/ Lumped Conceptual Model | /Groundwater level prediction tool | Groundwater level time-series | [33] | |

| AqYield/AqYield-N, Nitrogen oriented variant | Nitrogen leaching/ field scale, management for mitigating environmental nitrogen losses/ crop model N leaching | Crop soil | Soil properties, daily climate features, sowing & harvest dates, irrigation, soil tillage depth | [56-57] |

| Biome-BGC, biogeochemical ecosystem model | Soil carbon and nitrogen fluxes/ soil water storage, net primary productivity, transpiration, soil respiration, nitrogen mineralization and leaching prediction, net ecosystem exchange, key indicators for ecosystem quality status | Global scale model | Soil texture, depth, elevation, meteorological data (i.e. wet precipitation, temperature), local physiological parameters (e.g, canopy, limitation of light penetration, maximum photosynthetic rates, leaf carbon to nitrogen ratios, dead wood lignin proportion). | [91-92,94] |

| BRANN / type of ANN | /prediction of groundwater levels | Ground water model | [12,16,227] | |

| CALF | Herbicides/ Herbicides dynamic estimator | [144] | ||

| CAMEL | Diffuse sources transport of reactive phosphorus/ Phosphorus identification at critical source areas | Catchment scale | [28-29] | |

| CENTURY/process-based monthly time step model, DeyCent is the daily time step counterpart | crop development | Soil carbon (C) and Nitrogen (N) dynamics | Soil Organic Matter (SOM) and litter pools with different (C:N) ratios and decay rates | [86,230] |

| CERES-Maize | crop growth simulation | Crop soil | Weather data, solar radiation, soil texture, bulk density, growth parameters | [18] |

| CoupModel/ bio-geophysical, process-based, multi-component ecosystem model | Fertilizing optimization in croplands/ C, N dynamic cycles of terrestrial ecosystems | Agricultural soil | Soil organic matter, vegetation biomass, soil, weather and N deposition data | [110] |

| CREAMS | Field-scale Chemicals Runoff, and erosion model | [27] | ||

| CROPGRO-Soybean | crop growth simulation | Crop soil | Weather data, solar radiation, soil texture, bulk density, growth parameters | [18] |

| DAISY ver. 4.01 | Nitrogen leaching / Cropping strategies affected nitrate leaching, agri-environmental indicators evaluation, precise fertilization | Agricultural soil | Soil hydraulic properties, climate data, soil texture, crop management | [95,101,128] |

| DayCent /mechanistic model, multi-layer soil division, a daily version of CENTURY | Nitrogen cycle in soils for various ecosystems | Cropland and forest soil | Soil and topographic properties/hillslopes, spatial distribution of land-use types, daily meteorological data, plant parameters nutrient amendments | [44-45] |

| DNDC | Nitrate leaching in crop field, aquifers nitrification/ Modeling nitrate leaching in crop field, carbon sequestration and nitrogen denitrification estimation | Crop field soil | Coupled with a biogeochemical model, crop yields datasets | [37-38,40,43,117-118,231-232] |

| DRAINMOD /deterministic hydrological model | Agricultural subsurface drainage for nutrient transport, groundwater salinity problems/ groundwater flow under shallow water table conditions, control the rising water table, transformation of nitrogen in a stream | Field scale, cultivated soil, soil profiles | [16,135-136,219] | |

| DRAINMOD-NII | nitrogen cycle to predict nitrogen dynamics | Shallow water table soils | Decomposition rate and C/N ratio, kinetics rates constants, N diffusion coefficient in the gaseous phase | [136-137,219] |

| DRAINMOD-P | Agricultural drainage for phosphorus transport/ phosphorus cycle to predict phosphorus dynamics | Artificial, agricultural, forest soil | [138,176] | |

| DRASTIC/ Adjusted DRASTIC Model (DRASTICA) | Groundwater vulnerability/ Soil solute leaching factors control on regional scale and prediction, land use management | Groundwater at a regional scale | GIS based, depth to groundwater, soil properties, topography | [15,104,233-234] |

| DSSAT (crop growth module) | Crop production simulation over time and space for different purposes | Cropland soil | Soil, crop, weather, and management input data | [70,161] |

| ECM | Nutrients’ load to surface water, total (N,P) / Prediction of phosphorus and nitrogen total amount delivered to surface water | national environmental databases/ geoclimatic region typology | [19]) | |

| EcoMod (agro ecosystem model) | Nutrients’ fate, leaching, adsorption, ammonium nitrification, gaseous (N2) losses / quantify the pastoral ecosystem responses to variability in climate and soil, choice of animal type for pasture, irrigation and fertilizer application | Pastoral soil ecosystem | Stochastically created 99-year climate files (Stochastic Climate Library), pasture growth date, animal’s physiology including production, water and nutrient dynamics in soils, calculations for light interception and photosynthesis. | [34-35] |

| EPIC | Soil erosion/ Erosion and Productivity Calculator, erosion’s effect on soil productivity and assessment | Agricultural soil | [124-125] | |

| EVACROP 1.5, uptd ver. EVACROP 3.0 percolation model | Nitrate leaching in crop field, aquifers nitrification/ Cultivation yield, optimization with catch crops | Crop field soil | Grain equivalent factors | [108-109] |

| FASTCHEM, geochemical hydrodynamic solute transport code based on MINTEQ approach | Fossil power plants pressure on soils/ Flying ash leaching attenuation on soils | Soil - flying ash interaction | [200] | |

| FEFLOW /Finite Element Subsurface Flow and Transport Simulation System | Predicts leachate flow and transport, landfill hydraulic stability prediction | Landfill capping | Saturated hydraulic conductivity, soil water retention characteristics, actual meteorological data, solar radiation, leaf area index, evapotranspiration, surface runoff and the interflow | [211,214] |

| FRAME (coupled unsaturated flow model SIWARE and a groundwater simulation model SGMP) | irrigation water management model | Groundwater basins | [16,235] | |

| GEPIC/spatially distributed | simulated crop-soil nitrogen dynamics, calculates the optimal fertilizer allocation, groundwater quality standards compliance | Cultivated land/regional scale | [236-238] | |

| GLEAMS (inc. hydrol. erosion, & pesticide component)/lumped conceptual | Agricultural subsurface drainage, nutrient transport, fate of agricultural chemicals/ water quality evaluation, prediction, model, agricultural, management, through the plant root zone | Field-size area soil | [29-30,239] | |

| GLYCIM | Soybean crop simulation model | [89,241] | ||

| GOSSYM/ mechanistic two-dimensional (2D) gridded soil model, incorporates many routines as components, coupled with expert system GOSSYM-COMAX, GOSSYM-2DSOIL | Soil nitrogen pollution, herbicides/ Cotton crop growth and yield, COMAX an inference incorporated engine for cultivation practices, fertilizing regulation, water, carbon and nitrogen interactions in soil, plant root zone and crop response to climate variables and water irrigation | Cultivated soil | Daily weather information, crop maturity, soil condition, plant growth data | [18,89-90] |