1. Introduction

Landmines continue to pose significant threats to both military personnel and civilians. According to casualty statistics from military conflicts, approximately 60% of injuries are attributable to the explosion of mines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) [

1]. The International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) reported that in 2022, the total number of casualties and specifically anti-vehicle mines (AVMs) resulting from explosive remnants of war (ERW) reached 4,710 and 102, respectively [

2]. Consequently, the development of blast-resistant or blastworthy structures for armored fighting vehicles (AFVs) as blast load mitigation remains critical.

As blast load and IEDs become more powerful, the blastworthy structures of AFVs must be increasingly resilient to withstand such threats. Various methods for blast loading mitigation have been researched through analytical, numerical, and experimental methods. As the simplest structure, single plates have been widely studied regarding their response to blast loading [

3,

4,

5,

6]. To enhance blastworthiness performance, modifications to single plates have been explored, such as adding stiffeners [

7,

8] and altering the flat plate to a V-shape [

9,

10]. However, single plates are insufficient for mitigating extreme blast loading. One of the most effective alternative blastworthy structures is the sandwich panel.

Sandwich panels are composite materials in which two or more different materials are combined at a macroscopic scale to produce a new material with superior performance compared to the constituent materials [

11]. A sandwich panel consists of two thin, rigid face sheets bonded to a thick, lightweight core. This hybrid design fundamentally increases the moment of inertia of the structure without significantly adding mass. Various core structures have been studied for sandwich panels under blast loading. For example, Dharmasena et al. [

12] investigated the blast response of metallic square honeycomb sandwich panels (HSPs) structures. The results showed that the deformation of the back face of the sandwich panel was 40-90% smaller than that of an equivalent solid plate. Zhu et al. [

13] conducted experimental studies on the blast responses of metallic hexagonal HSP. The introduction of hexagonal HSP significantly decreased deflection. Zhang et al. [

14] experimentally investigated the influence of geometric parameters of metallic trapezoidal corrugated-core sandwich panels subjected to blast loading. The results showed that increasing the sheet and cell thickness, as well as increasing the corrugated angle, enhanced the blast resistance. In addition to honeycomb and corrugated cores, aluminum foam has also proven effective as a core material in sandwich panels for withstanding blast loading. Numerous studies have examined aluminum foam sandwich panels (AFSPs) [

15,

16,

17], for instance, Hanssen et al. [

18] examined the behavior of AFSPs under blast loading experimentally, analytically, and numerically. The results demonstrated that using foam as a sacrificial layer can control the contact stress level, providing local protection to the structure. Liu et al. [

19] studied the responses of AFSPs under blast loading and found that the peak load of the sandwich panel was reduced by 61.54–64.69% compared to a single plate.

Conventional honeycomb structures typically exhibit positive Poisson’s ratio (PPR) characteristics. Over the past three decades, there has been increasing interest in negative Poisson’s ratio (NPR) or auxetic materials due to their unique and contrasting properties compared to conventional materials. These auxetic materials are a prime example of metastructures, which are artificially designed structures with specific geometrical arrangements leading to unusual physical and mechanical properties. Auxetic structures, as a subset of metastructures, expand in all directions when stretched and contract when compressed. This opposite deformation behavior of auxetic materials leads to enhanced mechanical properties, such as more resistant to indentation [

20,

21], increased shear modulus [

22,

23], improvement in fracture toughness [

24,

25,

26], and high energy absorption [

20,

27]. Due to these superior mechanical properties, auxetic materials have found applications in diverse fields such as medicine, biomedicine, sports, and engineering (for more details, see reference [

28]). Although auxetic materials have superior mechanical properties, the application of ASPs in AFVs remains relatively uncommon and under-researched.

Several studies have investigated auxetic sandwich panels (ASPs) under air blast loading. For instance, Imbalzano et al. [

29] and Yan et al. [

30] studied the responses of ASP and hexagonal HSP to blast loading numerically and experimentally, respectively. Both studies demonstrated that ASP exhibits higher blast resistance than conventional HSP due to increased compressive stiffness as the impact zone of ASP shrinks inward. Lan et al. [

31] examined the dynamic response of cylindrical ASP, conventional HSP, and AFSP subjected to blast loading. The results showed that cylindrical ASP outperformed both conventional HSP and AFSP across all design parameter combinations. Qi et al. [

32] conducted experiments on close-in blast loading on ASP. The results showed that the introduction of ASP effectively prevented damage to the concrete base under close-in blast loading. Chen et al. [

33,

34] conducted experimental studies on the blast response of ASP with re-entrant and double-arrow structures as the core under paper tube-guided air blast loading. The results showed that the double-arrow structure had 10.9-20.5% less permanent displacement than re-entrant structures. Yan et al. [

35] conducted blast experiments on 3D-printed auxetic honeycomb sandwich beams (AHSBs). The results showed that AHSBs possess better blast performance than regular honeycomb. Overall, most research on ASP under blast loading indicates that ASP offers superior blastworthiness compared to previous structures.

The primary objective of blastworthiness performance is to protect occupants within a structure. One quantifiable metric is the displacement or acceleration experienced by occupants. Additionally, blastworthy structures must achieve sufficient lightweight construction to facilitate the mobility of AFVs. These two objectives often conflict with each other. Multi-objective optimization has been demonstrated as effective in addressing this challenge. Due to the complexity and non-linearity, there is no direct relationship between geometric parameters of auxetic structures and blastworthiness performance. Therefore, surrogate models or metamodels are utilized. Numerous studies have focused on multi-objective optimization of blastworthiness performance, for instance, Cong et al. [

10] optimized the design of multi-V hulls for light AFVs using artificial neural networks (ANNs) and the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II (NSGA-II). They optimized for lower tibia force and hull mass, achieving a 33-42% improvement in blastworthiness and a 43% reduction in mass compared to the baseline design. Qi et al. [

36] and Wang et al. [

37] conducted optimizations of curved and graded AFSPs, respectively, using NSGA-II with ANN and Kriging models as metamodels. Qi and Jiang et al. [

38,

39] optimized re-entrant ASP using radial basis function (RBF) and NSGA-II. The optimum design produces better performance by reducing maximum deflection until 33% and increase the areal specific energy absorption until 158.6%. Wang et al. [

40] and Lan et al. [

41] optimized 3D double-arrow sandwich panels.

Previous studies have primarily focused on re-entrant and double-arrow structures as cores for ASPs. However, other fundamental auxetic structures, such as star honeycomb and chiral honeycomb, remain largely unexplored. This study investigates ASPs incorporating four basic auxetic geometries: re-entrant honeycomb (REH), double-arrow honeycomb (DAH), star honeycomb (SH), and chiral honeycomb (CH), specifically for air blast loading scenarios. Numerical simulations were employed to evaluate the blastworthiness performance of these ASP configurations. Subsequently, a metamodel was developed to establish relationships between the design variables of ASPs and their blastworthiness performance. Global sensitivity analysis (GSA) was conducted to highlight the influence of each design variable on blastworthiness. Following this, multi-objective optimization was performed to generate a Pareto-optimal front. Finally, the optimal design from the Pareto front was identified as a protective structure suitable for AFVs subjected to air blast loading.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A. and S.P.S.; methodology, A., S.P.S., D.W., and A.N.P.; software, A.; validation, A., S.P.S., D.W., and A.N.P.; formal analysis, A., S.P.S., D.W., and A.N.P.; data curation, A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.; writing—review and editing, S.P.S., D.W., and A.N.P.; visualization, A.; supervision, S.P.S., D.W., and A.N.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

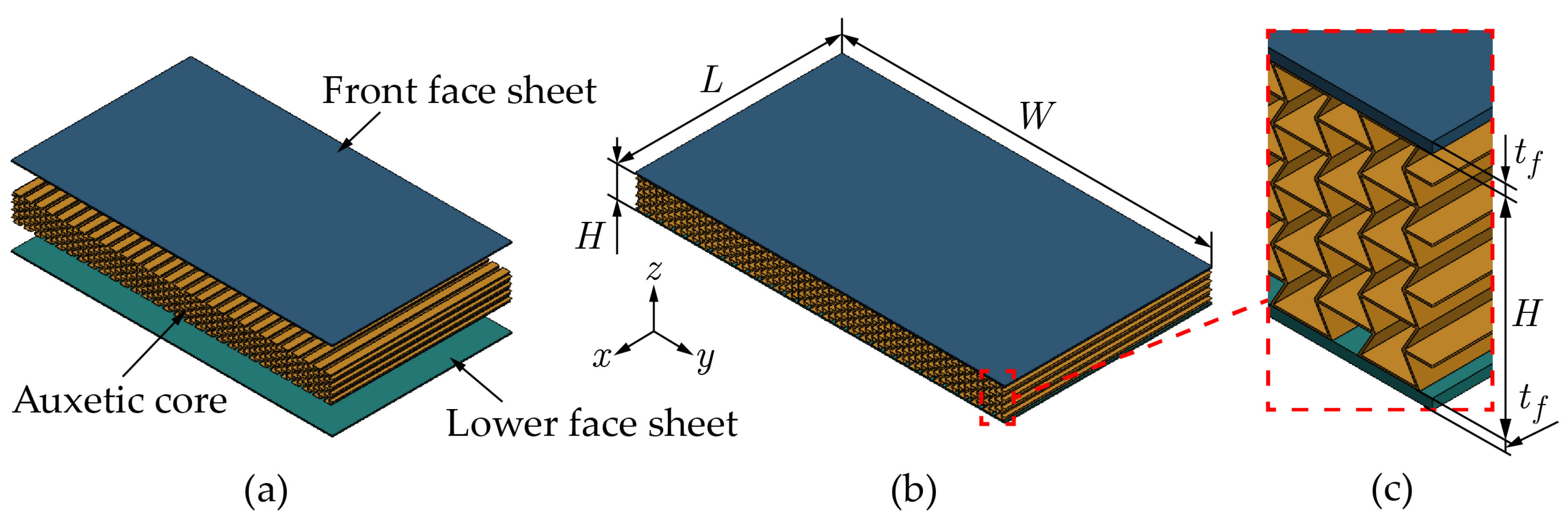

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic diagram of ASP which consists of two face sheets and auxetic core. (b) The overall dimensions of ASP. (c) Enlarged diagram of ASP.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic diagram of ASP which consists of two face sheets and auxetic core. (b) The overall dimensions of ASP. (c) Enlarged diagram of ASP.

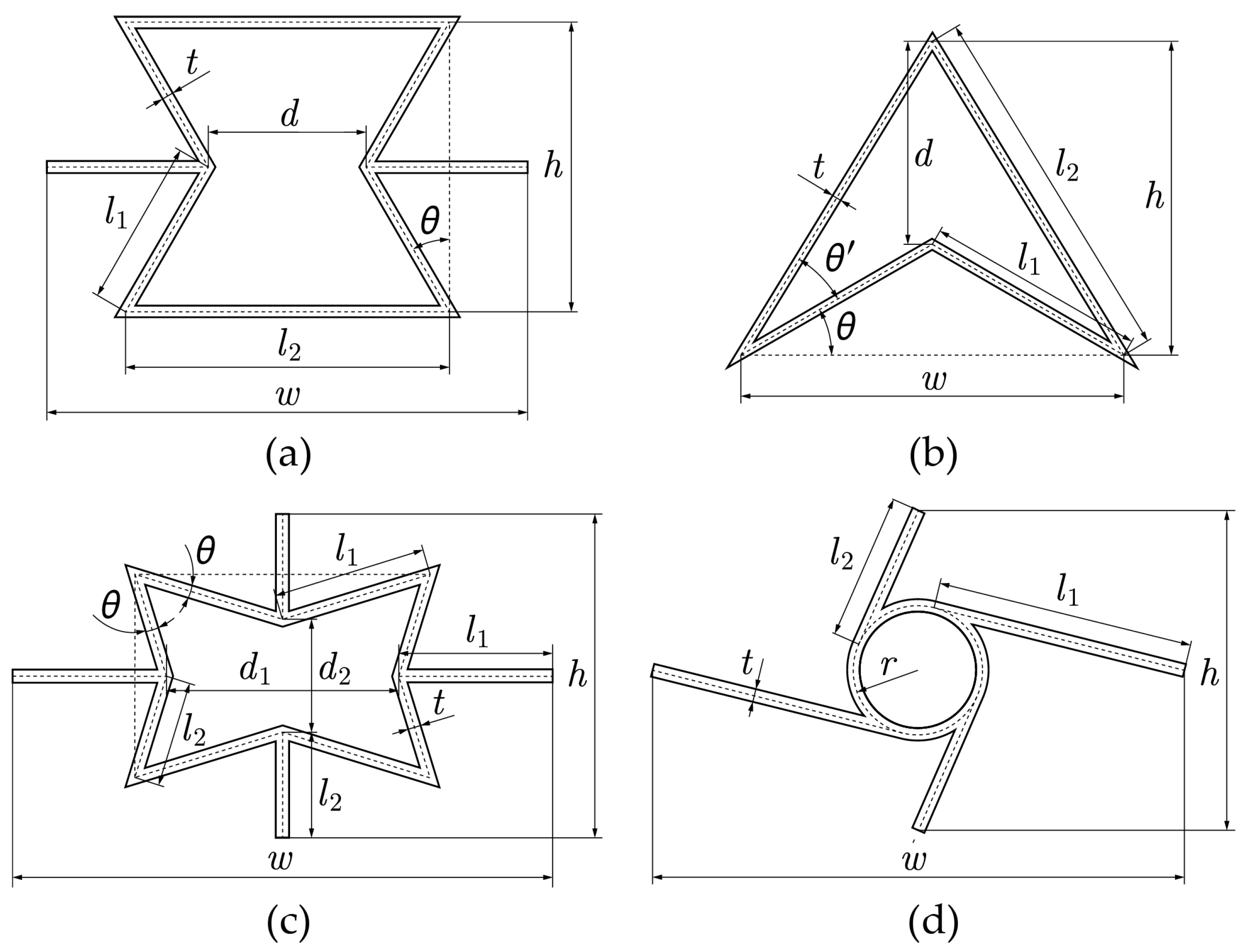

Figure 2.

Geometric parameters of: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH.

Figure 2.

Geometric parameters of: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH.

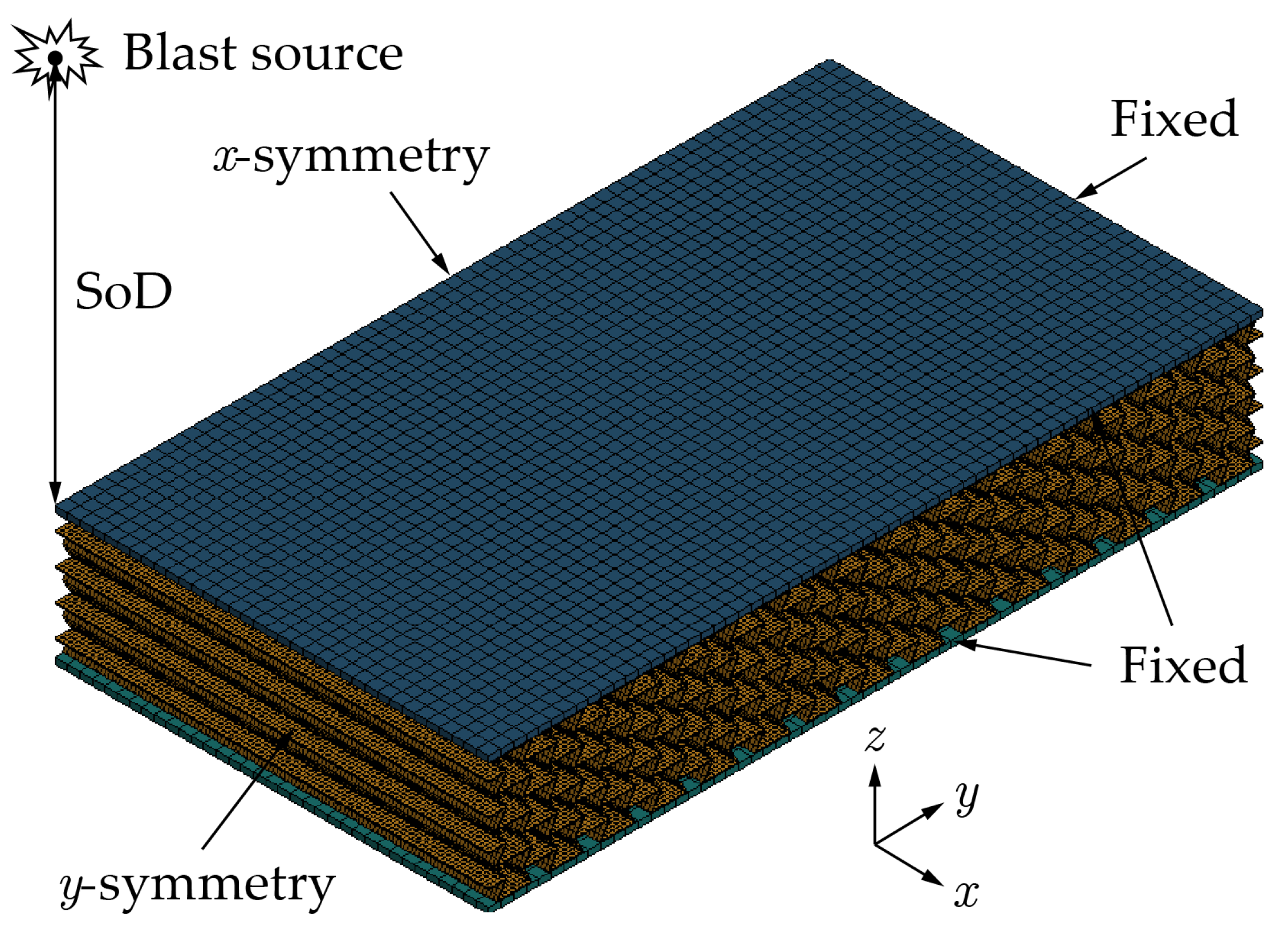

Figure 3.

The FE model of quarter-symmetric model of ASP undergoing air blast loading.

Figure 3.

The FE model of quarter-symmetric model of ASP undergoing air blast loading.

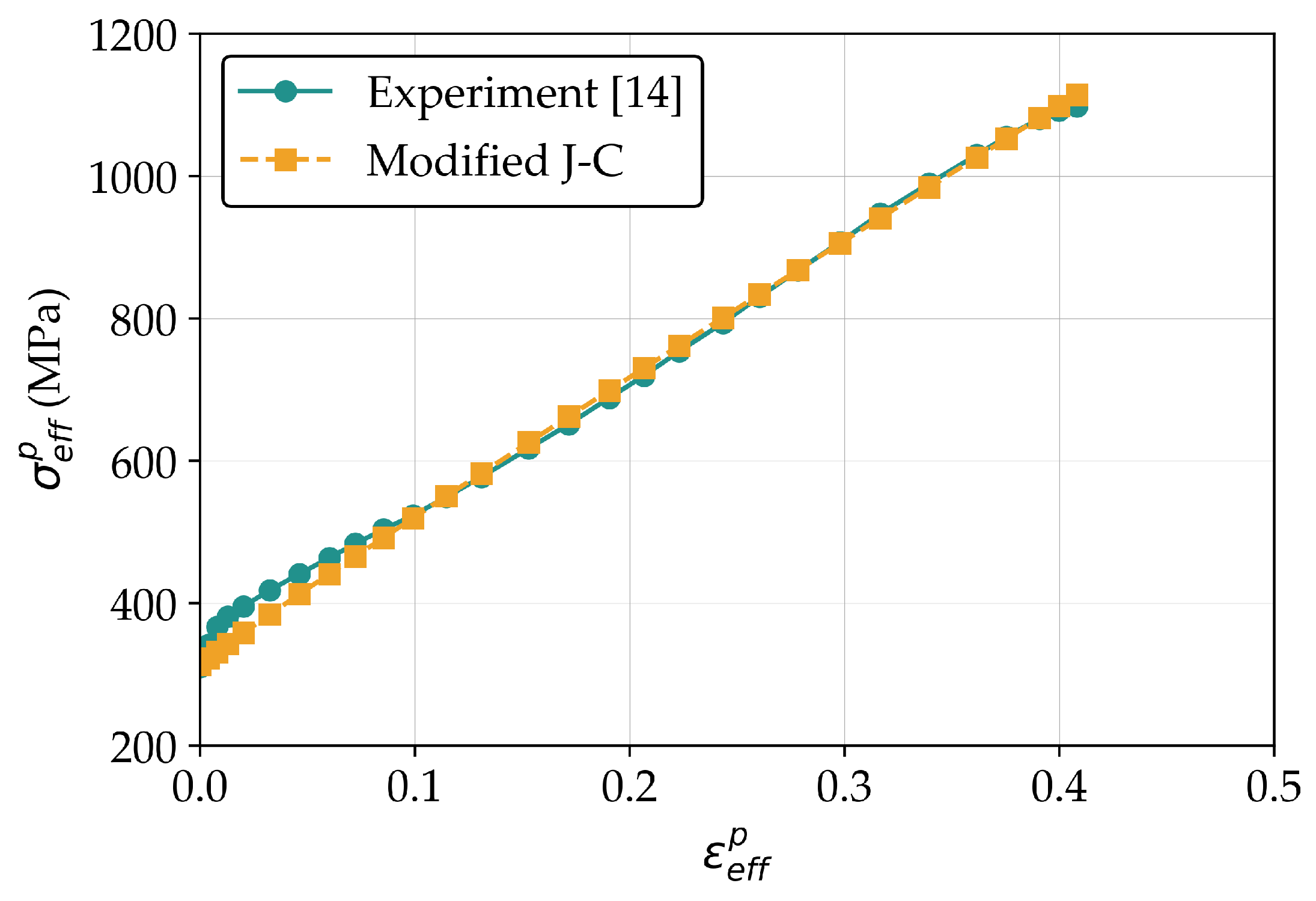

Figure 4.

The curve fitting of modified J-C parameters of 304 stainless steel with the experiment [

14].

Figure 4.

The curve fitting of modified J-C parameters of 304 stainless steel with the experiment [

14].

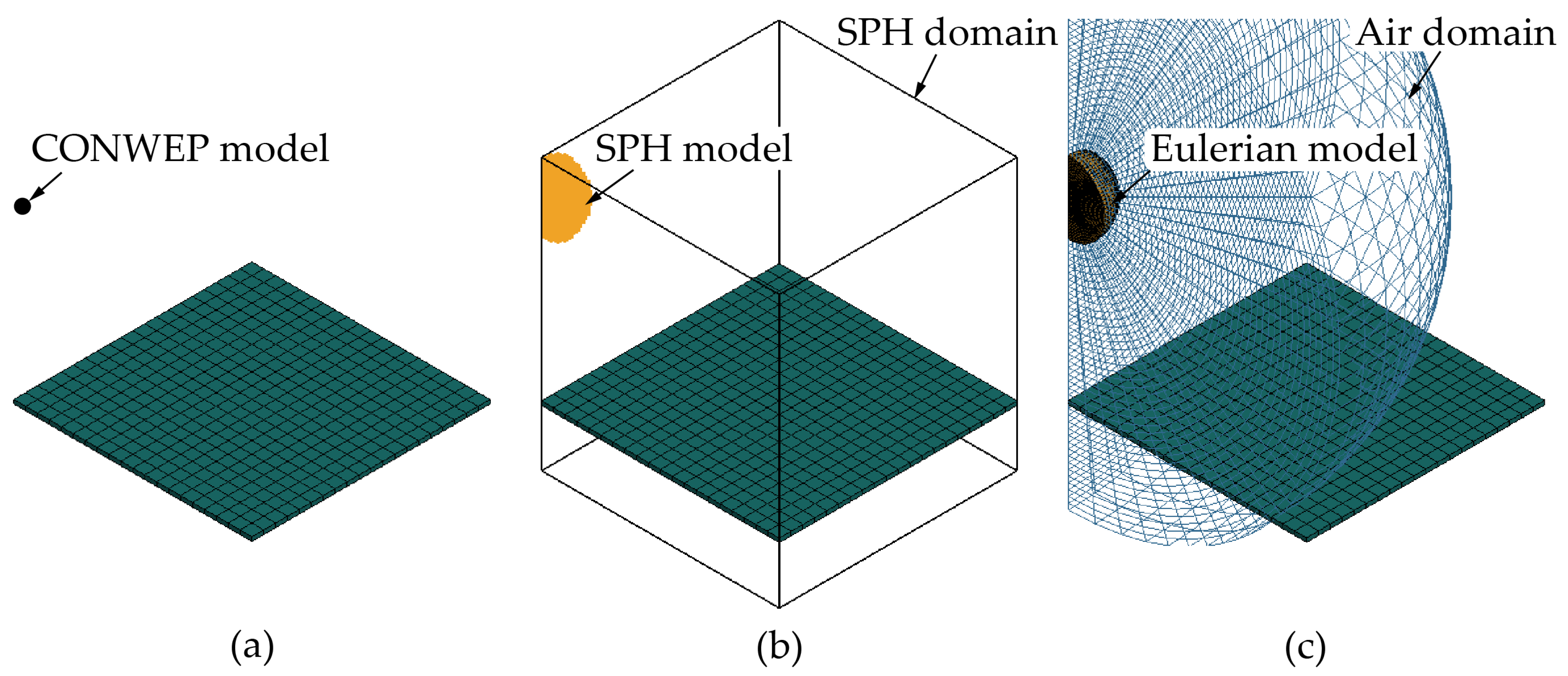

Figure 5.

The FE model of three types of air blast model: (a) CONWEP, (b) SPH, (c) MMALE.

Figure 5.

The FE model of three types of air blast model: (a) CONWEP, (b) SPH, (c) MMALE.

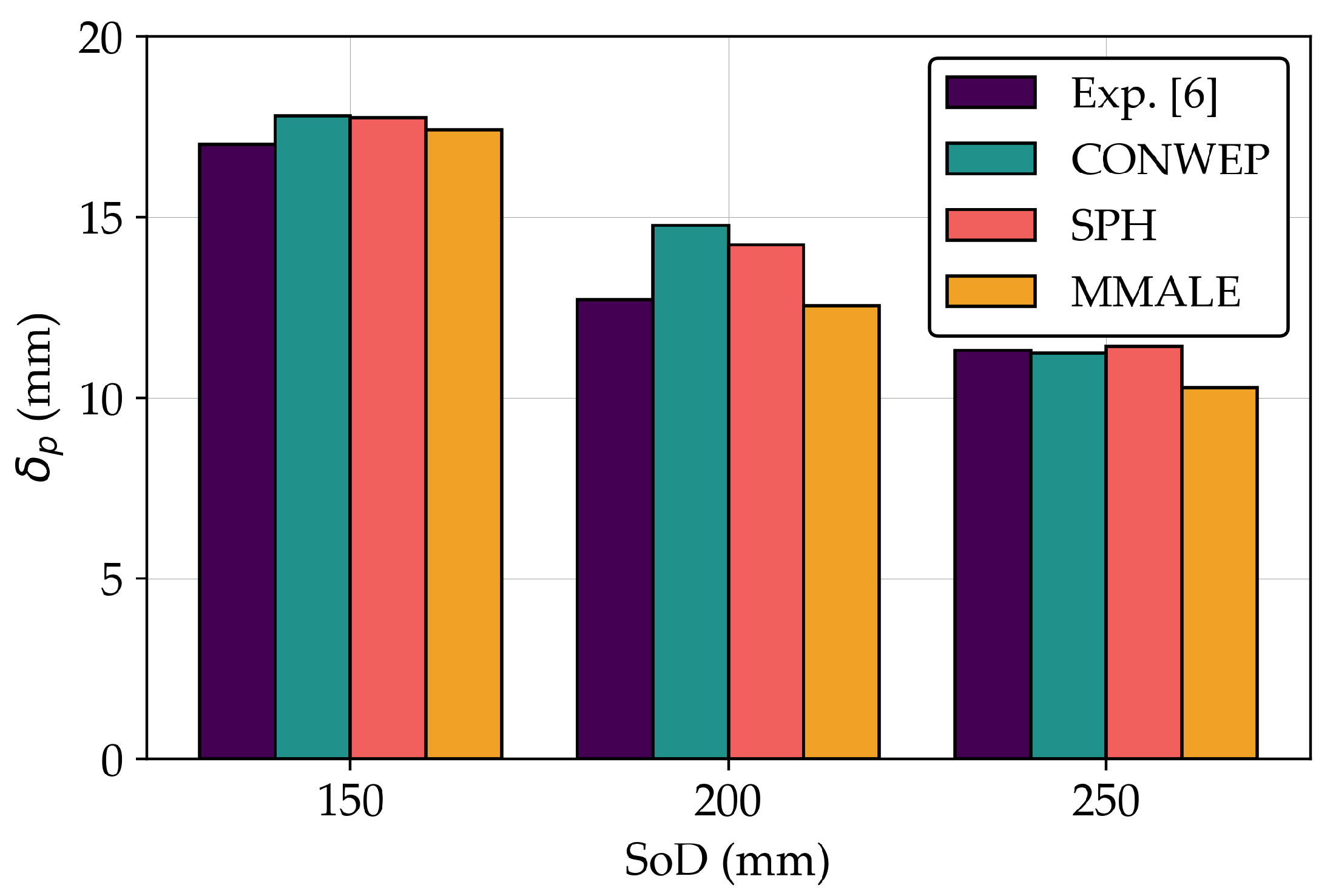

Figure 6.

The bar plot of

for different air blast model compared with the experimental results [

6].

Figure 6.

The bar plot of

for different air blast model compared with the experimental results [

6].

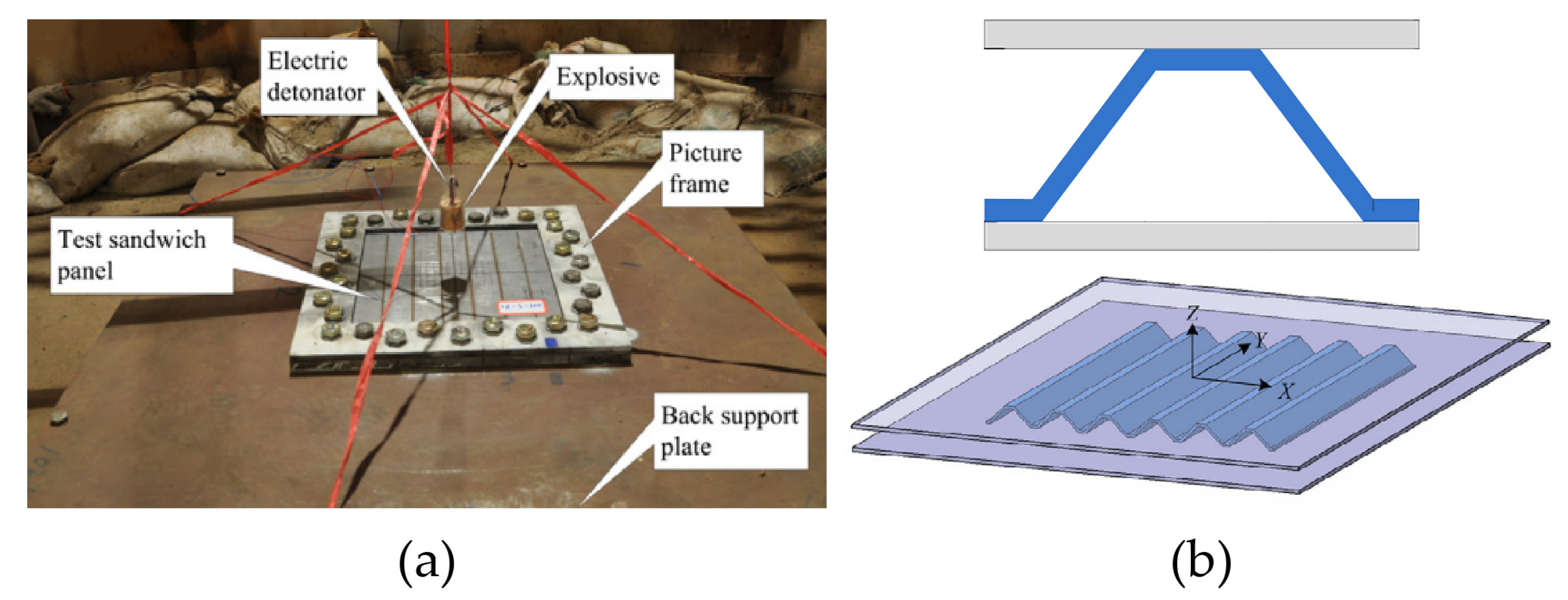

Figure 7.

(a) The experimental set-up of blast test. (b) The schematic diagram of trapezoidal corrugated-core sandwich panel [

14].

Figure 7.

(a) The experimental set-up of blast test. (b) The schematic diagram of trapezoidal corrugated-core sandwich panel [

14].

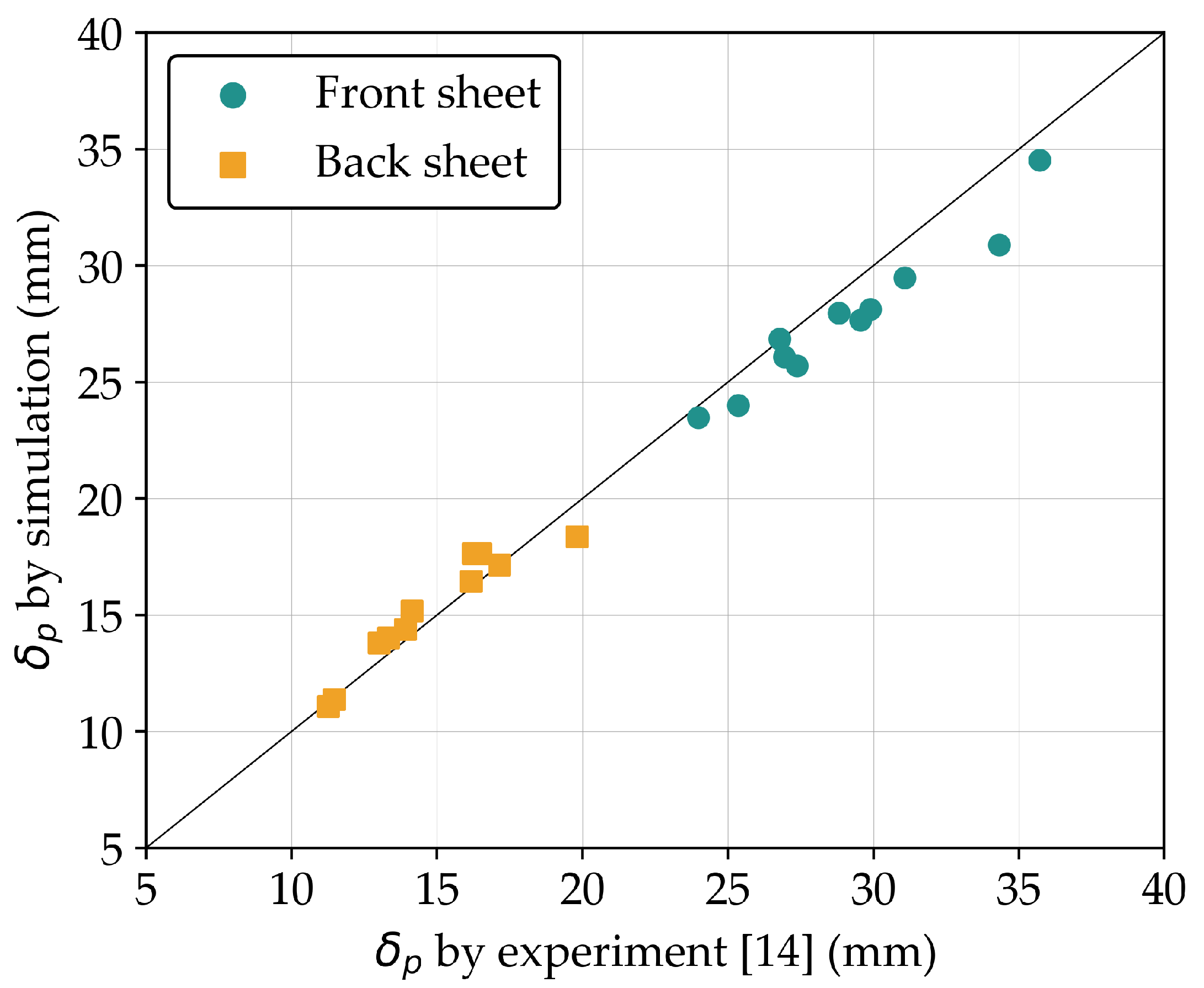

Figure 8.

The

comparison of numerical and experimental results [

14] for trapezoidal corrugated-core sandwich panels.

Figure 8.

The

comparison of numerical and experimental results [

14] for trapezoidal corrugated-core sandwich panels.

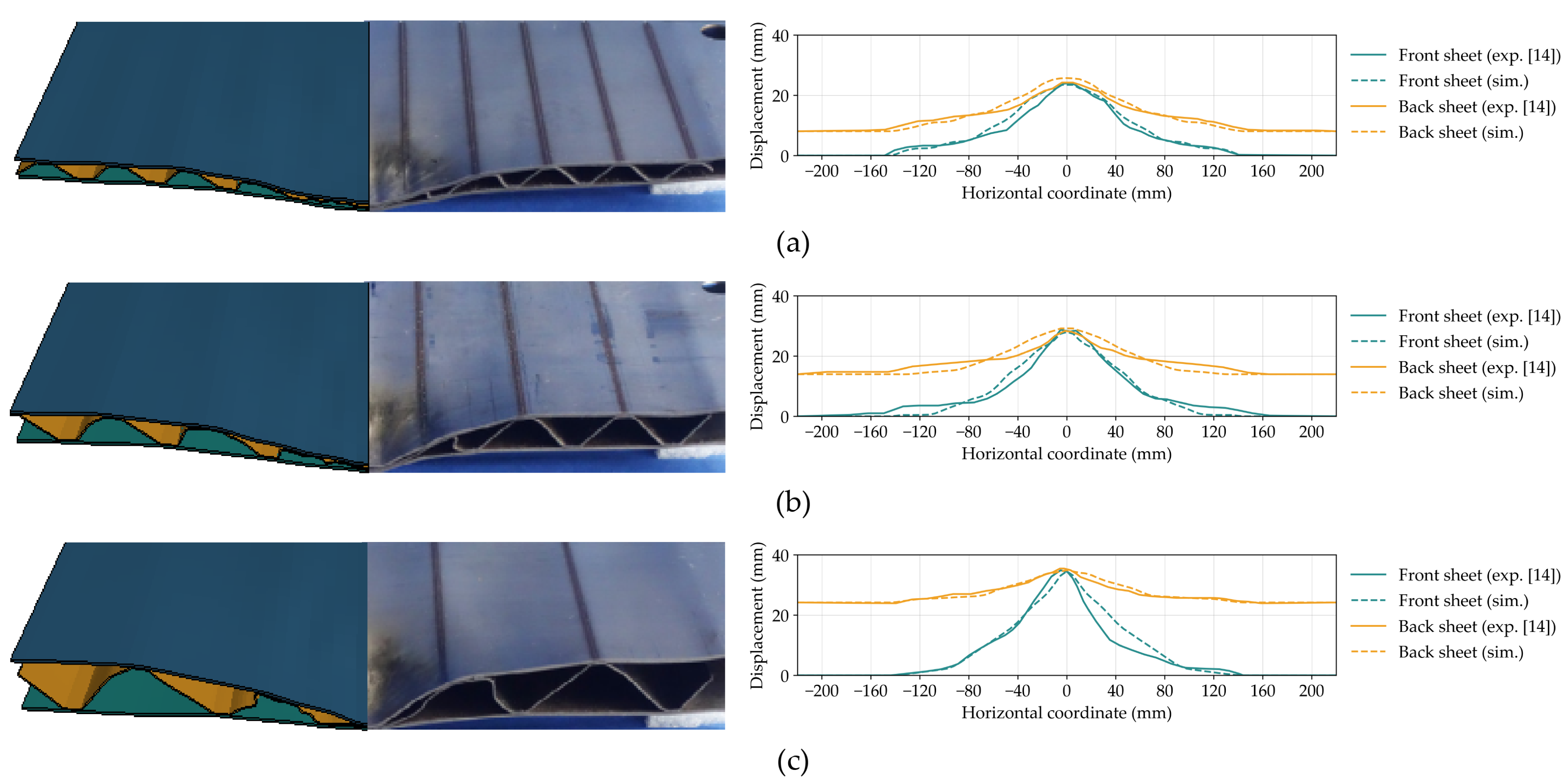

Figure 9.

The comparison of numerical simulation and experimental [

14] deformation of specimen: (a) TZ-12, (b) TZ-2, and (c) TZ-13.

Figure 9.

The comparison of numerical simulation and experimental [

14] deformation of specimen: (a) TZ-12, (b) TZ-2, and (c) TZ-13.

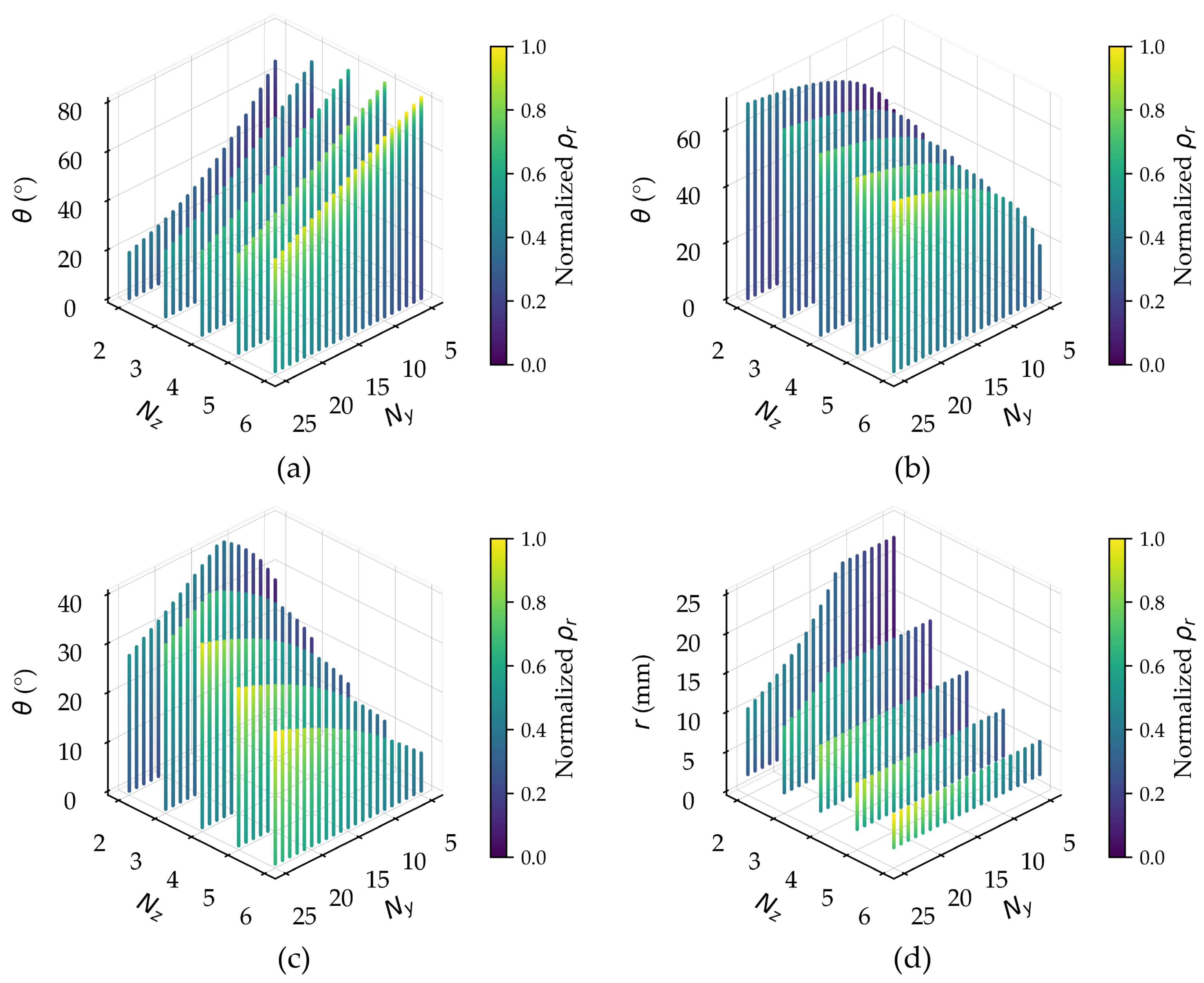

Figure 10.

Design space of: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH for MOOP. The color represents the normalized .

Figure 10.

Design space of: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH for MOOP. The color represents the normalized .

Figure 11.

Comparison of predicted (left) and SEA (right) by metamodel and simulation results of: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH model.

Figure 11.

Comparison of predicted (left) and SEA (right) by metamodel and simulation results of: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH model.

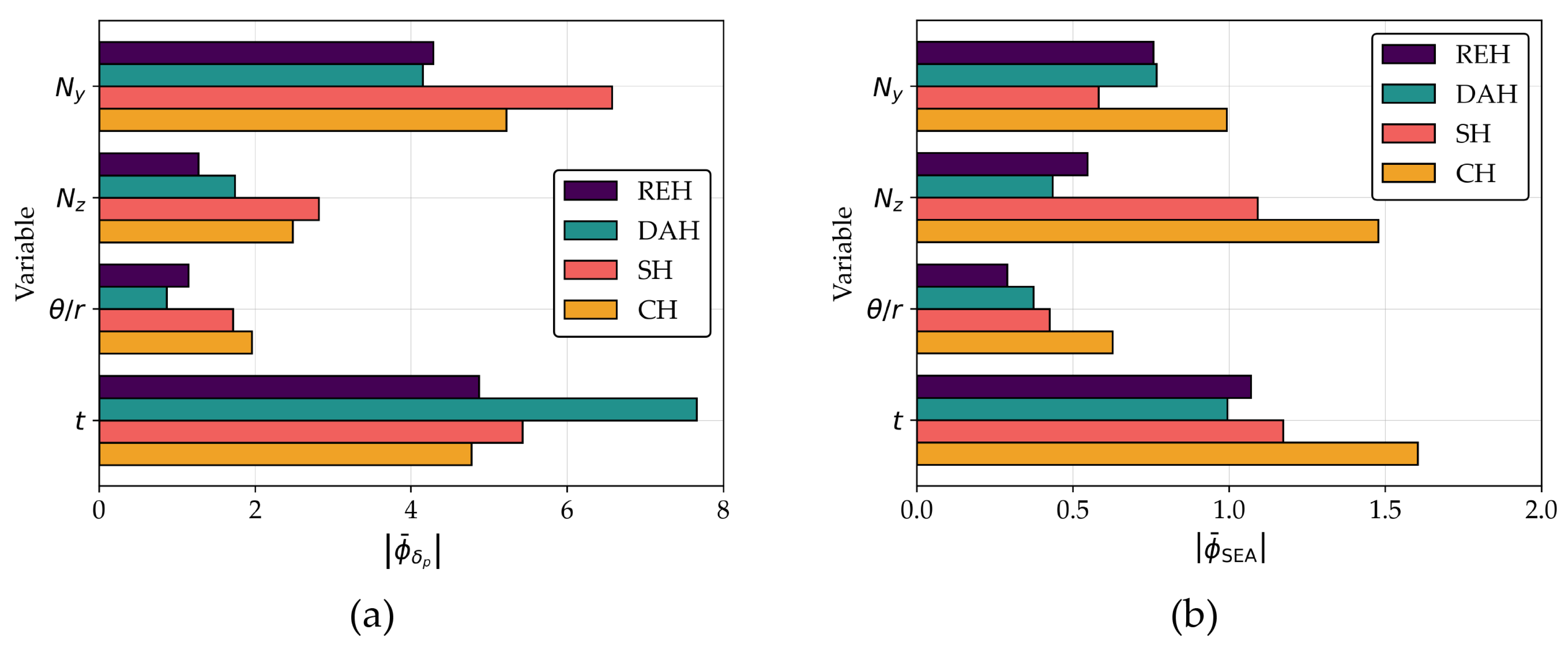

Figure 12.

The averaged SHAP bar plot of: (a) and (b) SEA for each auxetic model.

Figure 12.

The averaged SHAP bar plot of: (a) and (b) SEA for each auxetic model.

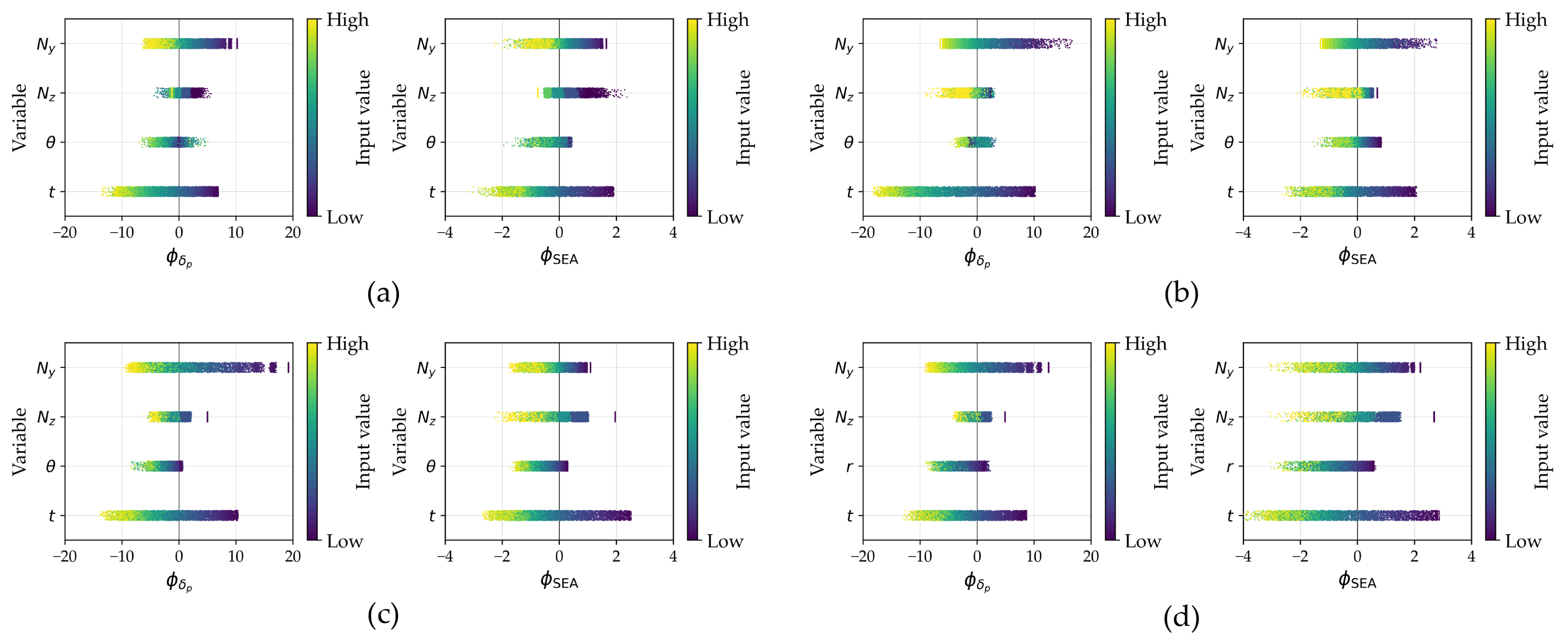

Figure 13.

SHAP summary plot of (left) and SEA (right) for: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH model.

Figure 13.

SHAP summary plot of (left) and SEA (right) for: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH model.

Figure 14.

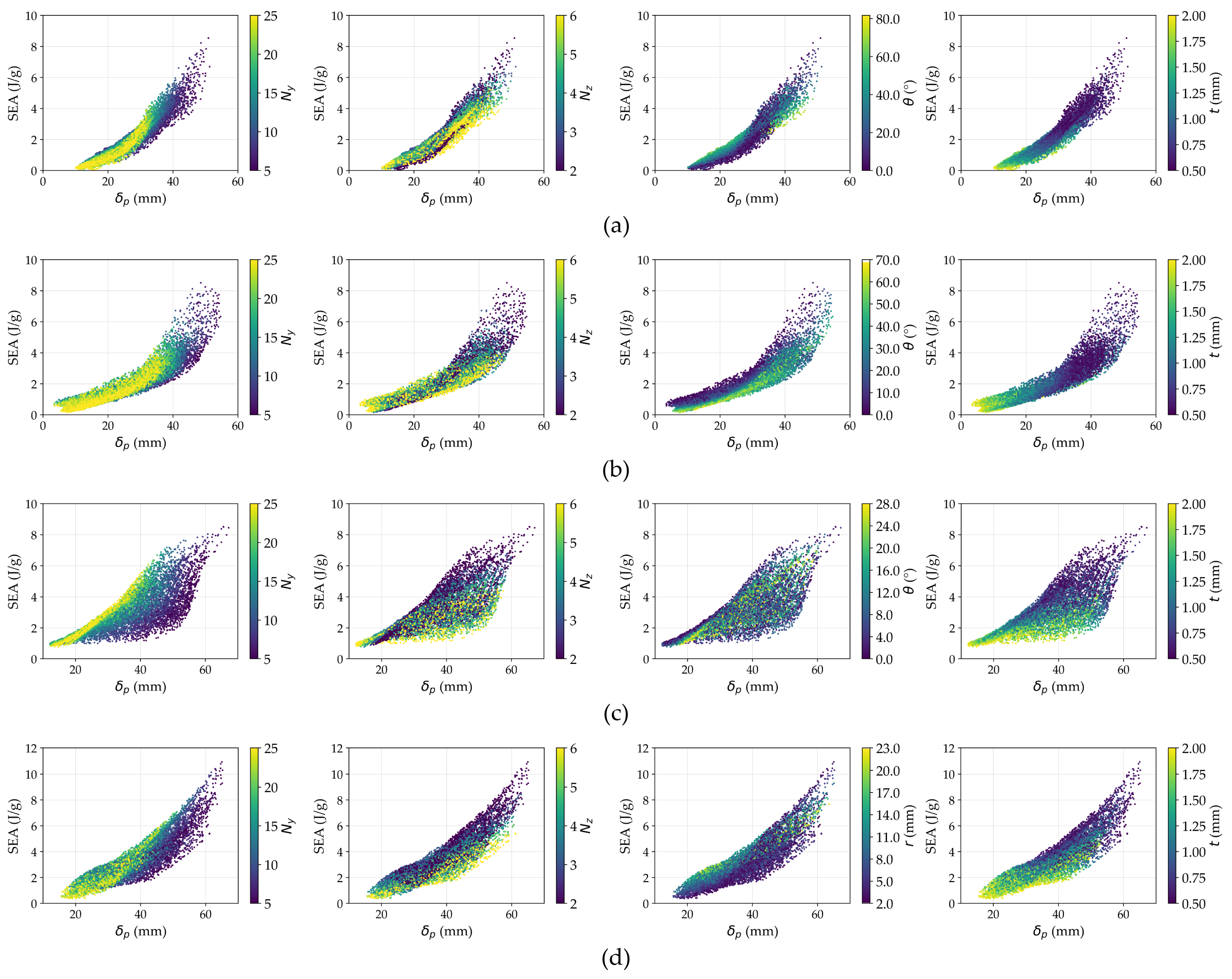

Scatter plot of the influence of input variables for: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH model.

Figure 14.

Scatter plot of the influence of input variables for: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH model.

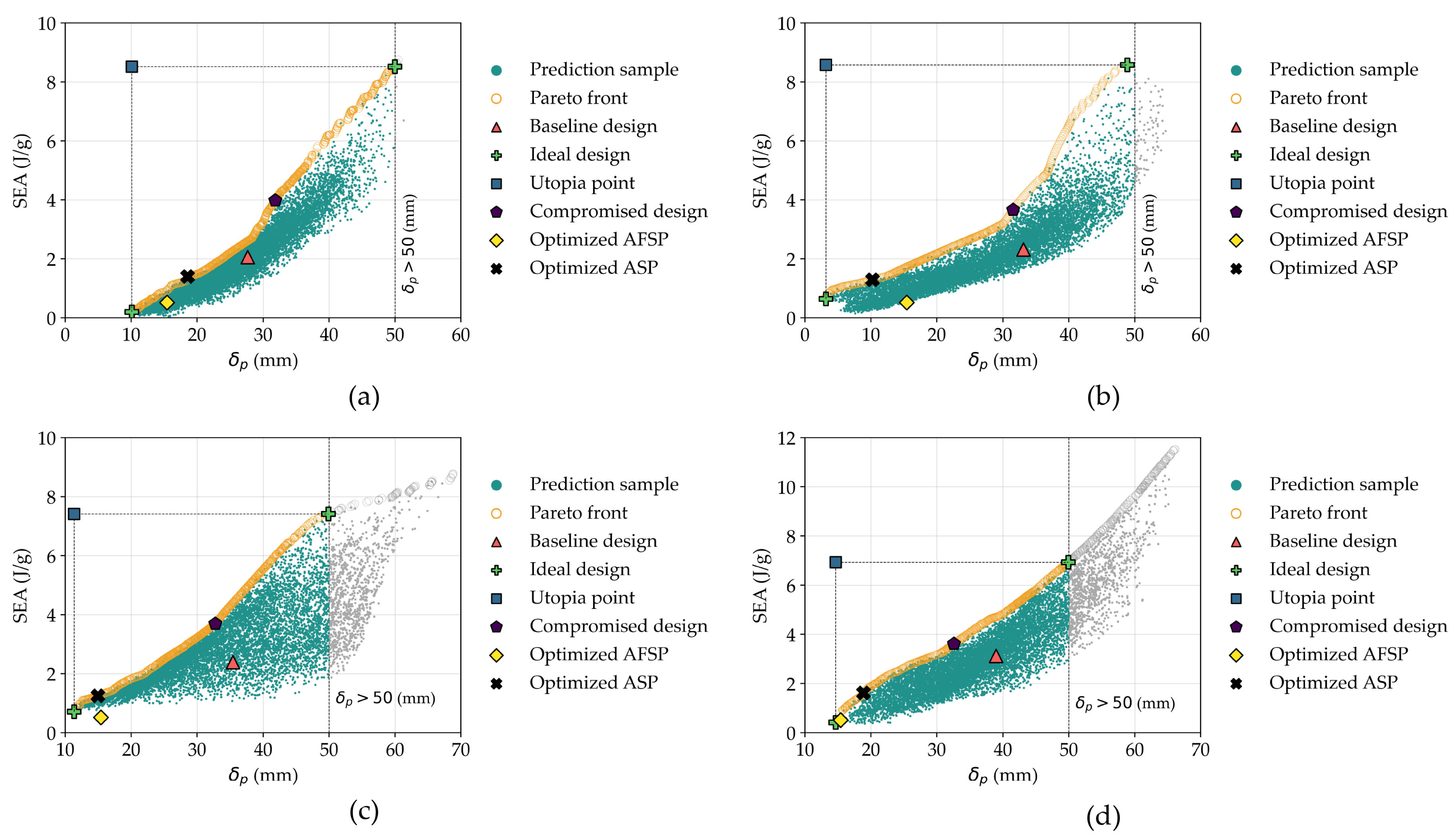

Figure 15.

Pareto front of MOOP for: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH model. The pareto front is limited to .

Figure 15.

Pareto front of MOOP for: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH model. The pareto front is limited to .

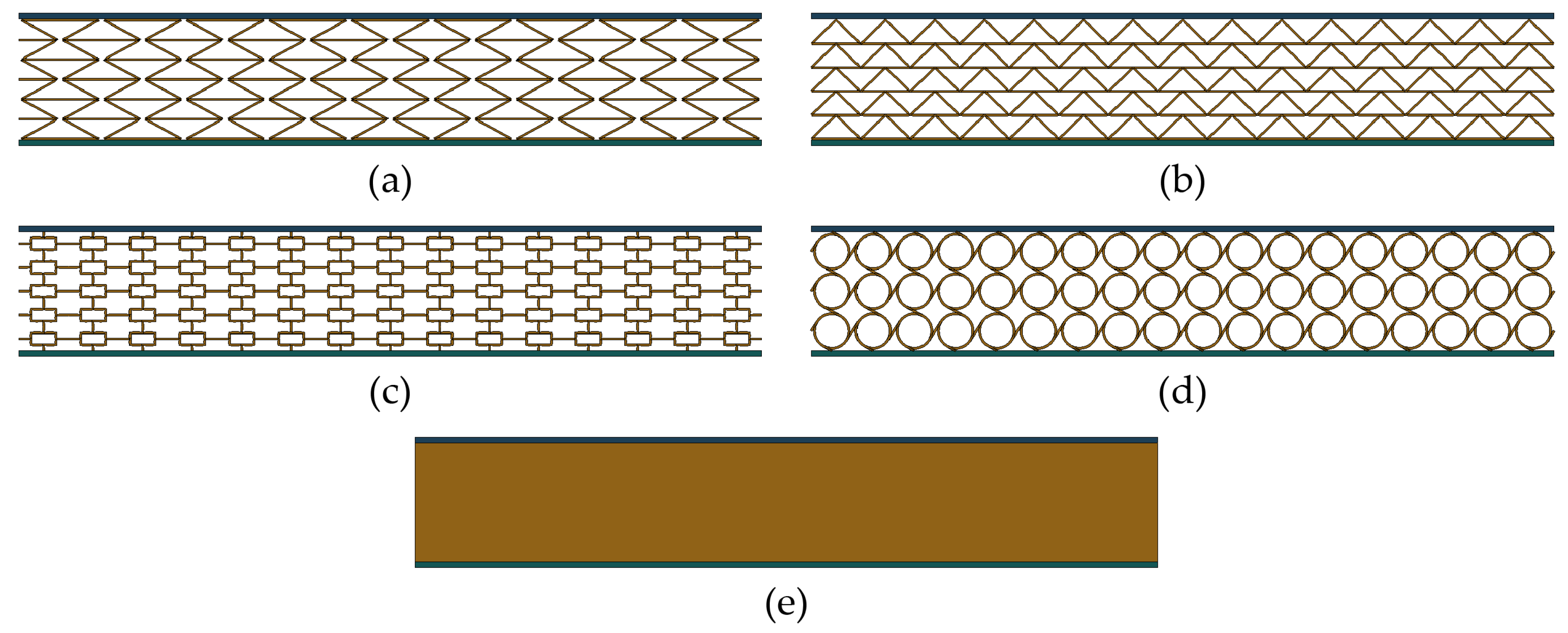

Figure 16.

The comparison of optimized ASP models: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, (d) SH; and (e) optimized AFSP model [

43].

Figure 16.

The comparison of optimized ASP models: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, (d) SH; and (e) optimized AFSP model [

43].

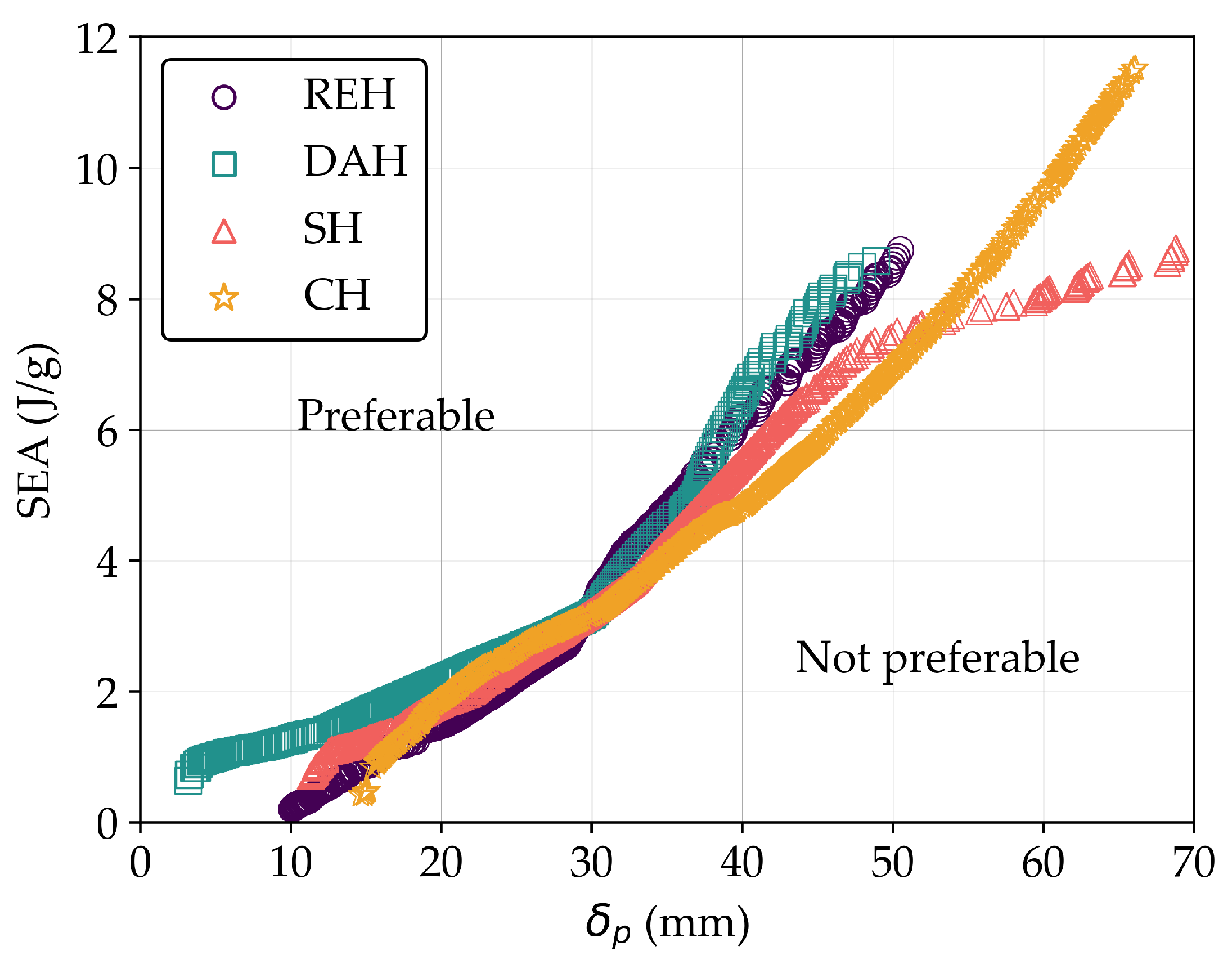

Figure 17.

The comparison of the pareto front for all auxetic models.

Figure 17.

The comparison of the pareto front for all auxetic models.

Figure 18.

Deformed shapes of four type models for each ASP: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH, at 5 ms. (from left to right: ideal model of maximum SEA, compromised model, baseline model, and ideal model of minimum ).

Figure 18.

Deformed shapes of four type models for each ASP: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH, at 5 ms. (from left to right: ideal model of maximum SEA, compromised model, baseline model, and ideal model of minimum ).

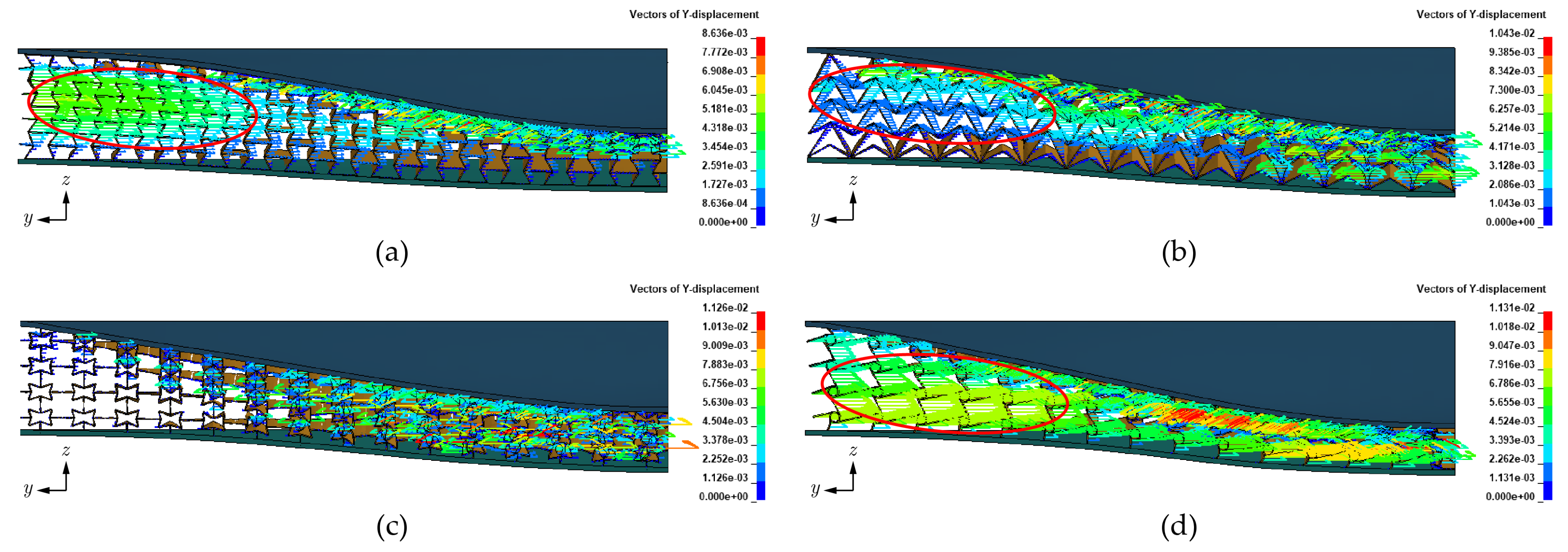

Figure 19.

Displacement vectors of ASP baseline model: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH. Red ellipse indicates the area that exhibit NPR behavior.

Figure 19.

Displacement vectors of ASP baseline model: (a) REH, (b) DAH, (c) SH, and (d) CH. Red ellipse indicates the area that exhibit NPR behavior.

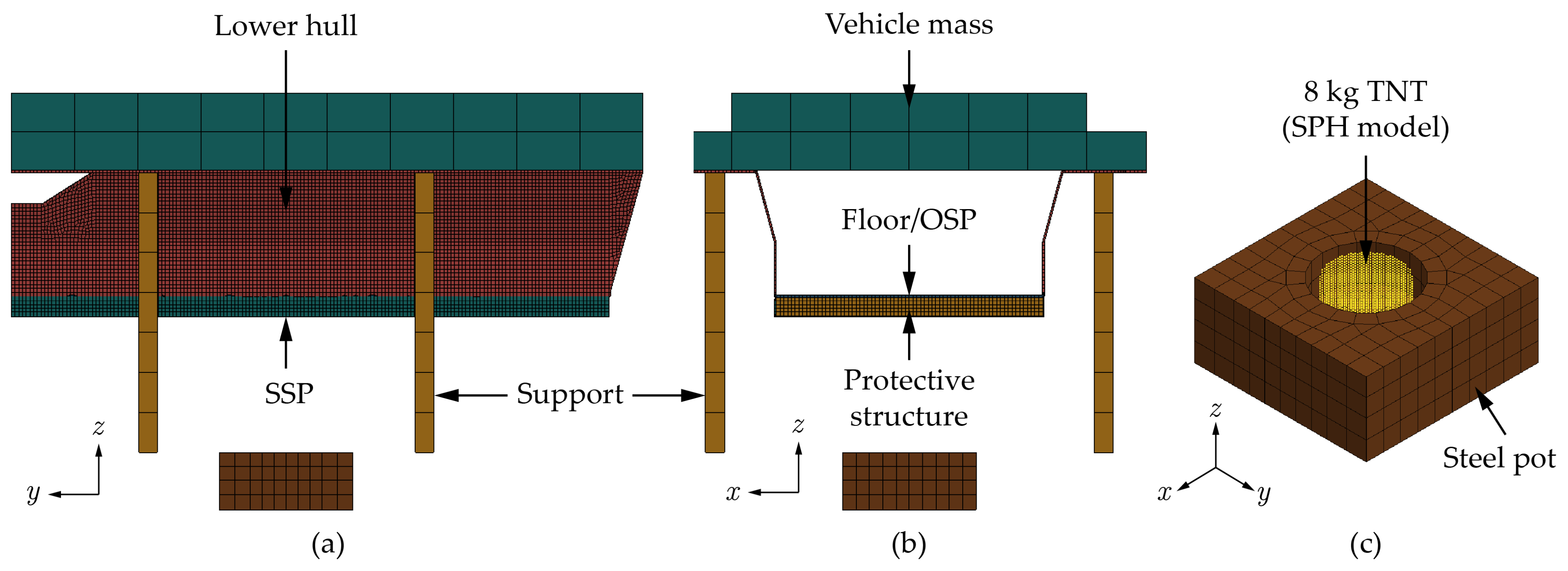

Figure 20.

The FE model of AFV sub-system under 8 kg TNT: (a) side view, (b) front view, (c) 8 kg TNT placed on a rigid steel pot.

Figure 20.

The FE model of AFV sub-system under 8 kg TNT: (a) side view, (b) front view, (c) 8 kg TNT placed on a rigid steel pot.

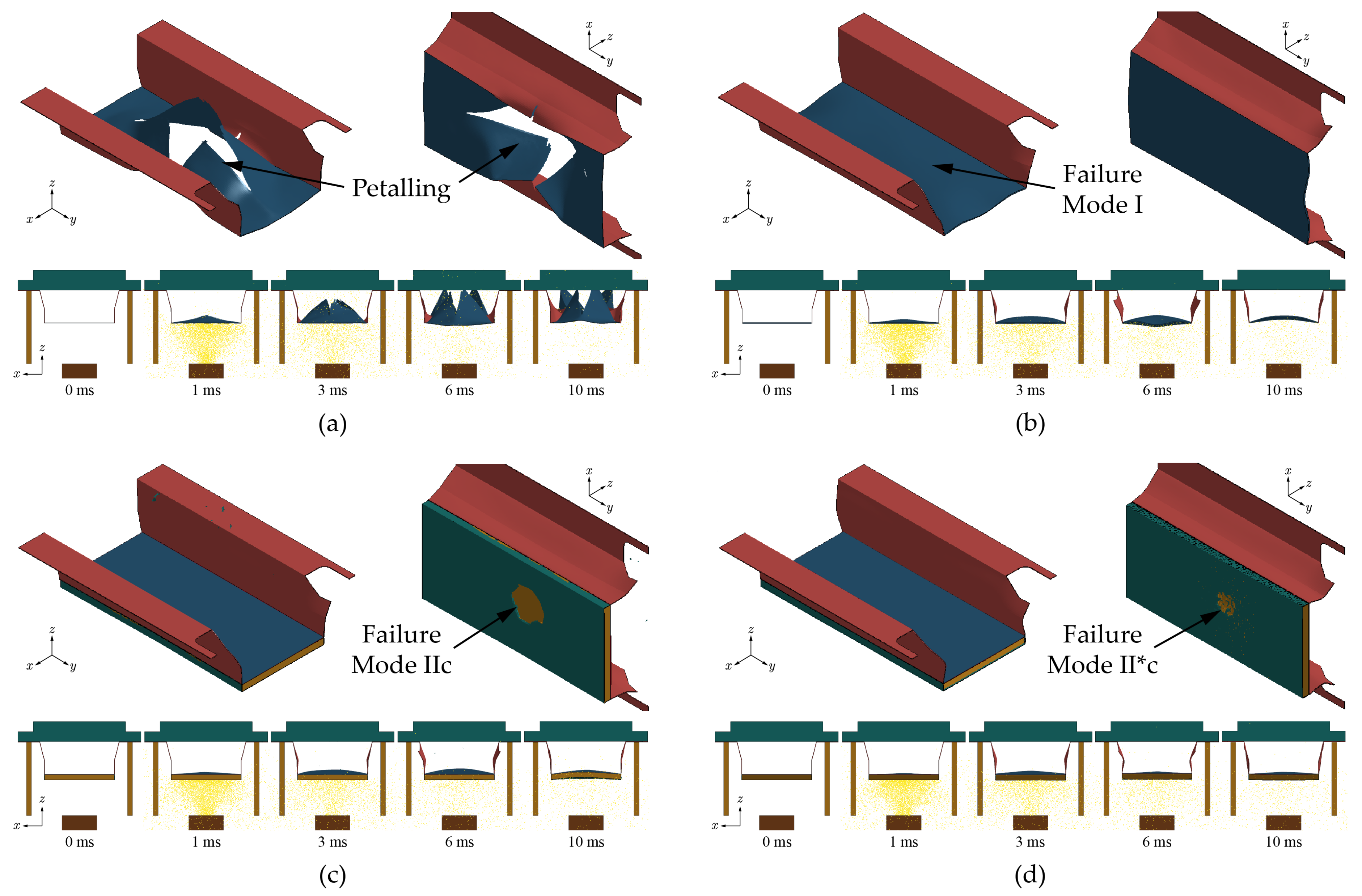

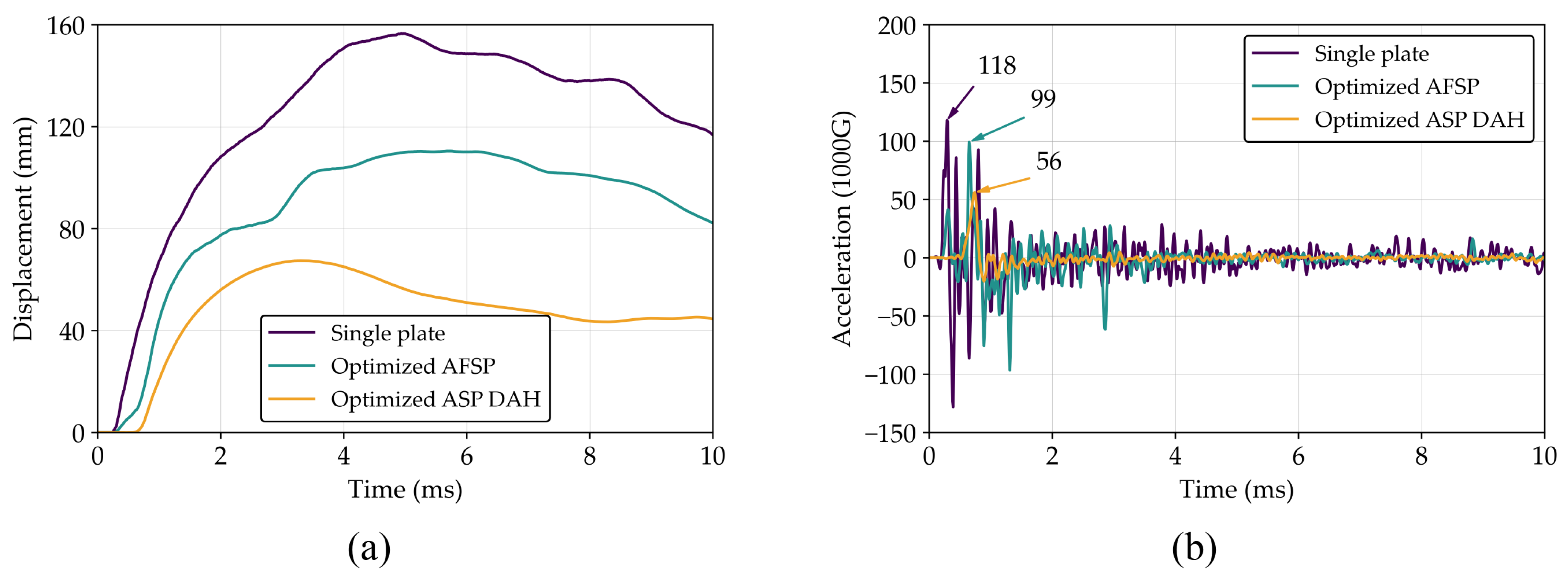

Figure 21.

Simulation result of AFV sub-system: (a) 10 mm OSP, (b) 20 mm OSP, (c) optimized AFSP, (d) optimized ASP DAH.

Figure 21.

Simulation result of AFV sub-system: (a) 10 mm OSP, (b) 20 mm OSP, (c) optimized AFSP, (d) optimized ASP DAH.

Figure 22.

Dynamic responses: (a) displacement and (b) acceleration for different structure types.

Figure 22.

Dynamic responses: (a) displacement and (b) acceleration for different structure types.

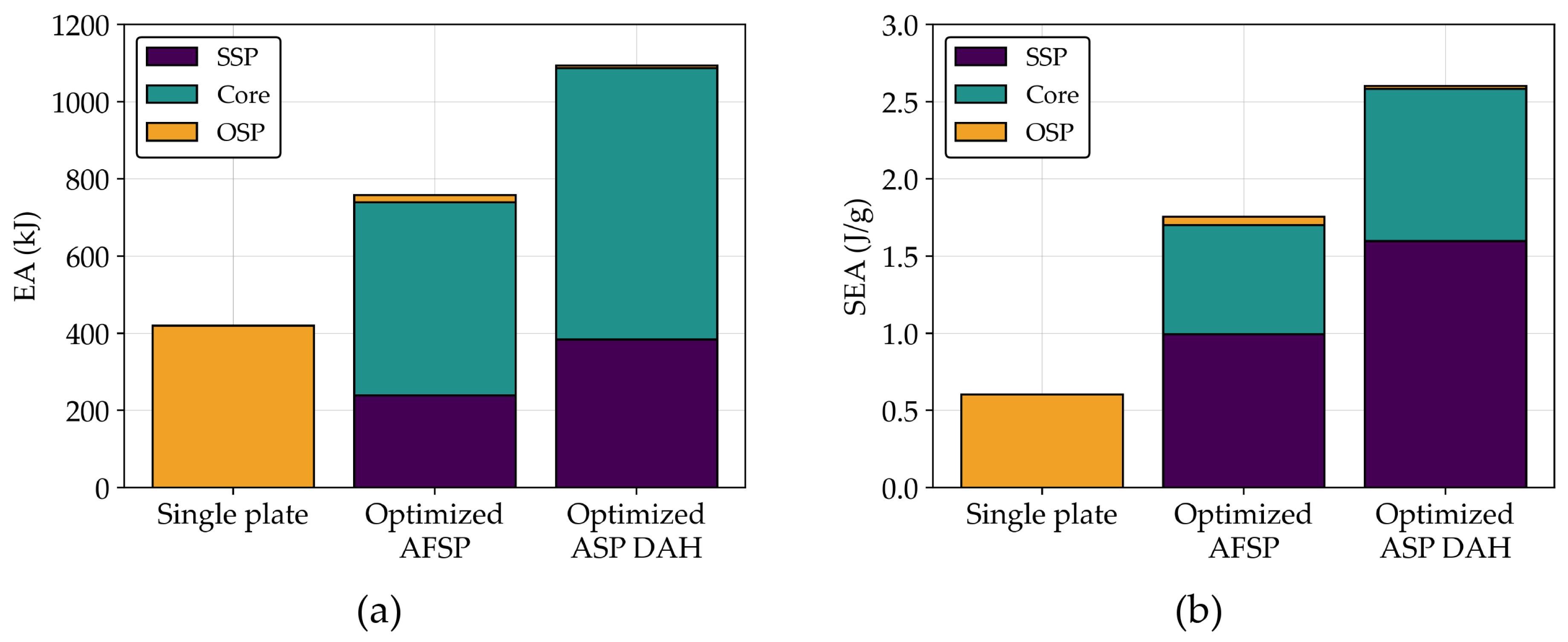

Figure 23.

(a) EA and (b) SEA from each part of AFV sub-system for different structure types.

Figure 23.

(a) EA and (b) SEA from each part of AFV sub-system for different structure types.

Table 1.

Geometry parameter definition for each auxetic geometry.

Table 1.

Geometry parameter definition for each auxetic geometry.

| Geometry |

Independent Variable |

Dependent Variable |

Constraint |

| REH |

, , , t

|

|

|

|

|

| DAH |

, , , t

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SH |

, , , t

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CH |

, , r, t

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

Modified J-C parameters of 304 stainless steel.

Table 2.

Modified J-C parameters of 304 stainless steel.

| E |

|

|

A |

B |

n |

|

C |

|

|

m |

|

|

| (GPa) |

(-) |

(kg/m3) |

(MPa) |

(MPa) |

(-) |

(s-1) |

(-) |

(K) |

(K) |

(-) |

(J/kg.K) |

(-) |

| 200 |

0.3 |

7900 |

310 |

1872 |

0.96 |

0.001 |

0.016 |

293 |

1673 |

1 |

500 |

0.9 |

Table 3.

High explosive burn material and JWL EOS parameter of TNT [

55].

Table 3.

High explosive burn material and JWL EOS parameter of TNT [

55].

|

|

|

A |

B |

|

|

|

|

|

| (kg/m3) |

(m/s) |

(GPa) |

(GPa) |

(GPa) |

(-) |

(-) |

(-) |

(MJ/m3) |

(-) |

| 1630 |

6930 |

21 |

371.2 |

3.231 |

4.15 |

0.95 |

0.3 |

7000 |

1 |

Table 4.

The

of various air blast model and experimental results [

6].

Table 4.

The

of various air blast model and experimental results [

6].

| SoD |

Exp. |

CONWEP |

SPH |

MMALE |

| Sim. |

Err. |

Sim. |

Err. |

Sim. |

Err. |

| (mm) |

(mm) |

(mm) |

(%) |

(mm) |

(%) |

(mm) |

(%) |

| 150 |

17 |

17.81 |

4.76 |

17.75 |

4.21 |

17.41 |

2.31 |

| 200 |

12.7 |

14.77 |

16.30 |

14.23 |

10.36 |

12.54 |

-1.12 |

| 250 |

11.3 |

11.23 |

-0.62 |

11.42 |

1.07 |

10.27 |

-9.02 |

Table 5.

The

results of numerical and experimental results [

14] for trapezoidal corrugated-core sandwich panels.

Table 5.

The

results of numerical and experimental results [

14] for trapezoidal corrugated-core sandwich panels.

| Specimen |

Front Sheet |

Back Sheet |

| Exp. |

Sim. |

Err. |

Exp. |

Sim. |

Err. |

| (mm) |

(mm) |

(%) |

(mm) |

(mm) |

(%) |

| TZ-2 |

28.81 |

27.97 |

-2.92 |

14.14 |

15.19 |

7.43 |

| TZ-4 |

34.33 |

30.89 |

-10.02 |

19.81 |

18.37 |

-7.27 |

| TZ-5 |

25.35 |

24.00 |

-5.33 |

11.47 |

11.39 |

-0.70 |

| TZ-6 |

29.55 |

27.65 |

-6.43 |

16.17 |

16.46 |

1.79 |

| TZ-7 |

26.77 |

26.86 |

0.34 |

13.33 |

14.02 |

5.18 |

| TZ-8 |

31.07 |

29.49 |

-5.09 |

17.15 |

17.15 |

-0.06 |

| TZ-9 |

26.94 |

26.09 |

-3.16 |

13.00 |

13.81 |

6.23 |

| TZ-10 |

29.90 |

28.13 |

-5.92 |

16.49 |

17.64 |

6.97 |

| TZ-11 |

27.37 |

25.71 |

-6.07 |

13.91 |

14.38 |

3.38 |

| TZ-12 |

23.98 |

23.49 |

-2.04 |

16.23 |

17.65 |

8.75 |

| TZ-13 |

35.72 |

34.53 |

-3.33 |

11.26 |

11.07 |

-1.69 |

Table 6.

Design constraint of each auxetic model for MOOP.

Table 6.

Design constraint of each auxetic model for MOOP.

| Geometry |

Design Constraint |

| REH |

|

| DAH |

|

| SH |

|

| CH |

|

Table 7.

Error parameter of all auxetic metamodel.

Table 7.

Error parameter of all auxetic metamodel.

| Geometry |

|

SEA |

| MAX |

MSE |

|

MAX |

MSE |

|

| (mm) |

(mm2) |

(-) |

(J/g) |

(J2/g2) |

(-) |

| REH |

3.059 |

0.713 |

0.991 |

0.418 |

0.009 |

0.996 |

| DAH |

3.307 |

0.684 |

0.994 |

0.302 |

0.006 |

0.997 |

| SH |

4.524 |

1.188 |

0.992 |

0.250 |

0.006 |

0.997 |

| CH |

4.309 |

1.779 |

0.982 |

0.498 |

0.012 |

0.996 |

Table 8.

Design variables and blastworthy performances of some selected design point for all auxetic geometry.

Table 8.

Design variables and blastworthy performances of some selected design point for all auxetic geometry.

| Geometry |

Type |

|

|

|

t |

|

|

SEA |

| Pred. |

Sim. |

Err. |

Pred. |

Sim. |

Err. |

| (-) |

(-) |

(/mm) |

(mm) |

(-) |

(mm) |

(mm) |

(%) |

(J/g) |

(J/g) |

(%) |

| REH |

Baseline |

15 |

4 |

30.0 |

1.00 |

0.115 |

27.50 |

27.64 |

-0.51 |

2.13 |

2.06 |

3.40 |

| Ideal min

|

25 |

6 |

45.3 |

1.99 |

0.434 |

10.07 |

8.32 |

21.03 |

0.20 |

0.22 |

-9.09 |

| Ideal max SEA |

5 |

2 |

0.1 |

0.54 |

0.022 |

49.96 |

50.89 |

-1.83 |

8.52 |

8.58 |

-0.70 |

| Compromised |

19 |

2 |

26.3 |

0.53 |

0.059 |

31.83 |

33.99 |

-6.35 |

3.98 |

4.08 |

-2.45 |

| Optimized |

9 |

3 |

61.5 |

1.63 |

0.203 |

18.58 |

17.92 |

3.68 |

1.40 |

1.19 |

17.65 |

| DAH |

Baseline |

15 |

4 |

30.0 |

1.00 |

0.123 |

30.39 |

33.12 |

-8.24 |

2.25 |

2.32 |

-3.02 |

| Ideal min

|

23 |

6 |

0.1 |

2.00 |

0.310 |

3.16 |

2.93 |

7.85 |

0.64 |

0.63 |

1.59 |

| Ideal max SEA |

6 |

2 |

2.6 |

0.5 |

0.024 |

48.88 |

49.51 |

-1.27 |

8.58 |

8.56 |

0.23 |

| Compromised |

25 |

2 |

0.1 |

0.68 |

0.070 |

31.56 |

33.90 |

-6.90 |

3.66 |

3.43 |

6.71 |

| Optimized |

15 |

5 |

0.1 |

1.72 |

0.205 |

10.24 |

9.76 |

4.92 |

1.29 |

1.31 |

-1.53 |

| SH |

Baseline |

15 |

4 |

17.0 |

1.00 |

0.115 |

34.85 |

35.41 |

-1.58 |

2.44 |

2.39 |

2.09 |

| Ideal min

|

20 |

6 |

16.1 |

2.00 |

0.328 |

11.33 |

11.78 |

-3.82 |

0.72 |

0.65 |

10.77 |

| Ideal max SEA |

13 |

2 |

1.1 |

0.51 |

0.032 |

49.89 |

50.25 |

-0.72 |

7.42 |

7.59 |

-2.24 |

| Compromised |

25 |

2 |

0.6 |

0.89 |

0.081 |

32.76 |

33.77 |

-2.99 |

3.69 |

3.57 |

3.36 |

| Optimized |

15 |

5 |

0.3 |

1.86 |

0.207 |

14.94 |

14.42 |

3.61 |

1.25 |

1.29 |

-3.10 |

| CH |

Baseline |

15 |

4 |

5.0 |

1.00 |

0.091 |

38.51 |

38.95 |

-1.13 |

3.17 |

3.12 |

1.60 |

| Ideal min

|

25 |

6 |

6.3 |

2.00 |

0.346 |

14.64 |

11.81 |

23.96 |

0.42 |

0.53 |

-20.75 |

| Ideal max SEA |

17 |

2 |

2.1 |

0.62 |

0.034 |

49.92 |

49.91 |

0.02 |

6.93 |

6.92 |

0.14 |

| Compromised |

18 |

3 |

14.5 |

0.66 |

0.072 |

32.57 |

34.33 |

-5.13 |

3.61 |

3.53 |

2.27 |

| Optimized |

18 |

3 |

14.6 |

1.88 |

0.206 |

18.87 |

15.44 |

22.22 |

1.62 |

1.28 |

26.56 |

Table 9.

The blastworthiness parameter of AFV sub-system without and with several types of protective structures.

Table 9.

The blastworthiness parameter of AFV sub-system without and with several types of protective structures.

| Parameter |

Single Plate |

Optimized AFSP |

Optimized ASP DAH |

| Max. displ. (mm) |

156.56 |

110.40 |

67.34 |

| (56.99%*/39.00%**) |

| SEA (J/g) |

0.60 |

1.76 |

2.61 |

| (335.00%*/48.30%**) |

| Max. acc. (1000G) |

118.01 |

99.20 |

55.99 |

| (52.55%*/43.56%**) |