Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

09 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Management, and Sample Size

2.3. Ultrasonographic Evaluation, Data Obtention and Groups Definition

2.4. Sampling and Laboratorial Evaluation of Hormones

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Hormone Profile

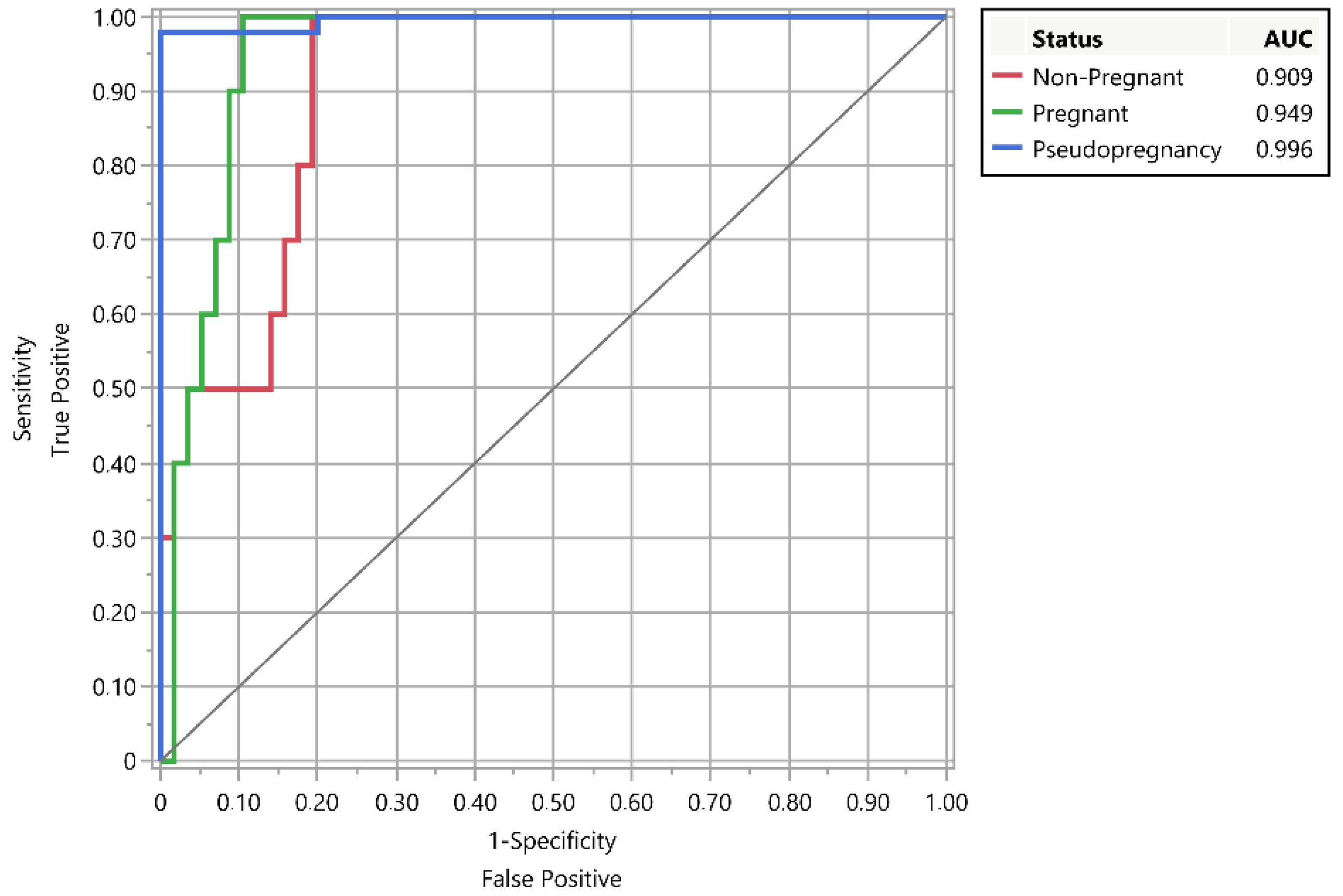

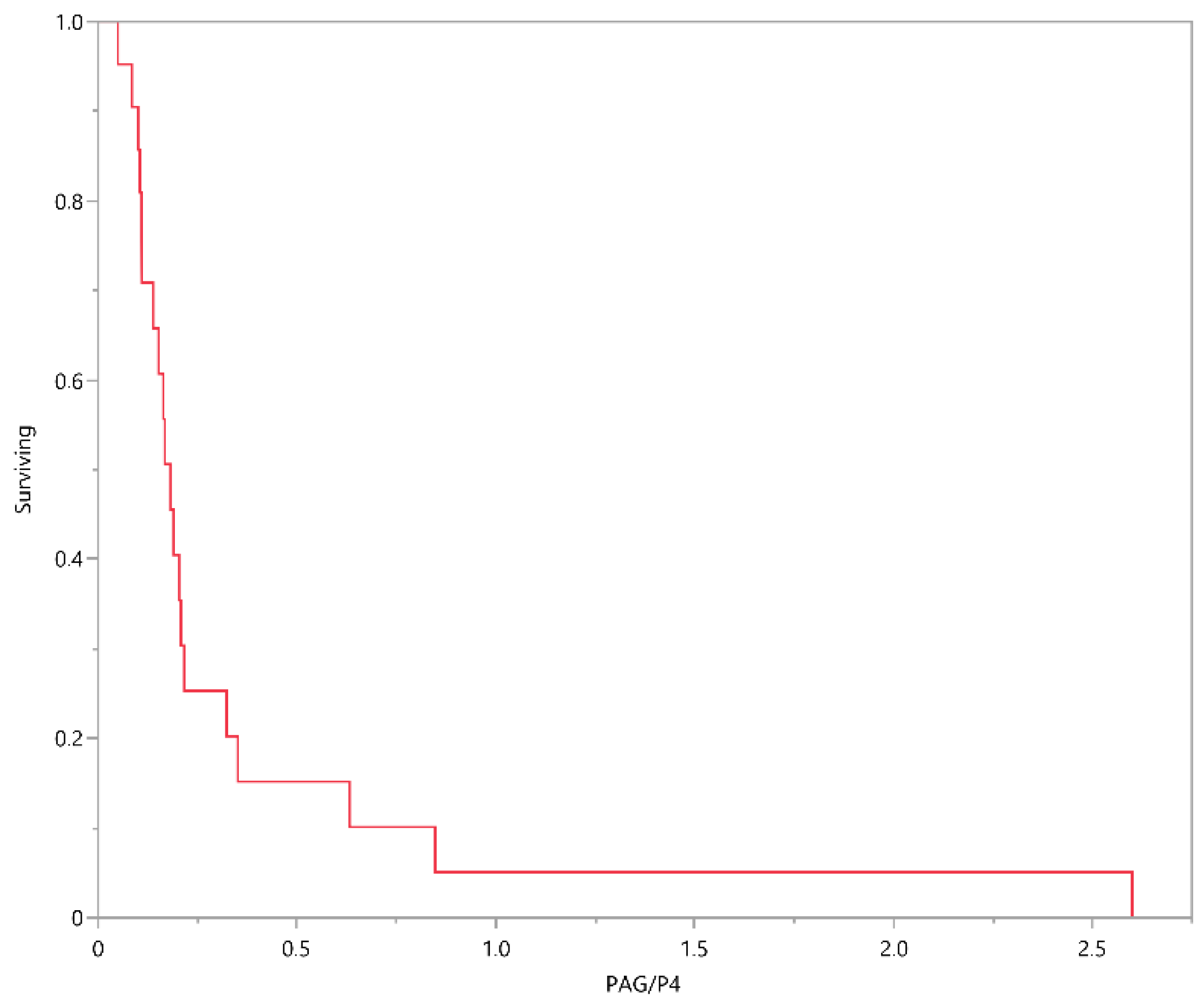

3.2. PAGs/P4 Ratio Biomarker

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almubarak, A.M.; Abass, N.A.E.; Badawi, M.E.; Ibrahim, M.T.; Elfadil, A.A.; Abdelghafar, R.M. Pseudopregnancy in Goats: Sonographic Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors in Khartoum State, Sudan. Vet World 2018, 11, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, A.L.R.S.; Brandão, F.Z.; Souza-Fabjan, J.M.G.; Veiga, M.O.; Balaro, M.F.A.; Siqueira, L.G.B.; Facó, O.; Fonseca, J.F. Hydrometra in Dairy Goats: Ultrasonic Variables and Therapeutic Protocols Evaluated during the Reproductive Season. Animal Reproduction Science 2018, 197, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesselink, J.W. Hydrometra in Dairy Goats: Reproductive Performance after Treatment with Prostaglandins. Veterinary Record 1993, 133, 186–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, J.M.G.; Maia, A.L.R.S.; Brandão, F.Z.; Vilela, C.G.; Oba, E.; Bruschi, J.H.; Fonseca, J.F. Hormonal Treatment of Dairy Goats Affected by Hydrometra Associated or Not with Ovarian Follicular Cyst. Small Ruminant Research 2013, 111, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desire, S.; Mucha, S.; Coffey, M.; Mrode, R.; Broadbent, J.; Conington, J. Pseudopregnancy and Aseasonal Breeding in Dairy Goats: Genetic Basis of Fertility and Impact on Lifetime Productivity. Animal 2018, 12, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.K.; Agrawal, K.P. A Review of Pregnancy Diagnosis Techniques in Sheep and Goats. Small Ruminant Research 1992, 9, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselink, J.W.; Taverne, M.A.M. Ultrasonography of the Uterus of the Goat. Veterinary Quarterly 1994, 16, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverne, M.; Hesselink, J.W.; Bevers, M.M.; Van Oord, H.A.; Kornalijnslijper, J.E. Aetiology and Endocrinology of Pseudopregnancy in the Goat. Reprod Domestic Animals 1995, 30, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverne, M.A.M.; Lavoir, M.C.; Bevers, M.M.; Pieterse, M.C.; Dieleman, S.J. Peripheral Plasma Prolactin and Progesterone Levels in Pseudopregnant Goats during Bromocryptine Treatment. Theriogenology 1988, 30, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittek, T.; Erices, J.; Elze, K. Histology of the Endometrium, Clinical–Chemical Parameters of the Uterine Fluid and Blood Plasma Concentrations of Progesterone, Estradiol-17β and Prolactin during Hydrometra in Goats. Small Ruminant Research 1998, 30, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbayo, J.M.; Green, J.A.; Manikkam, M.; Beckers, J.-F.; Kiesling, D.O.; Ealy, A.D.; Roberts, R.M. Caprine Pregnancy-Associated Glycoproteins (PAG): Their Cloning, Expression, and Evolutionary Relationship to Other PAG. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2000, 57, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbato, O.; Menchetti, L.; Brecchia, G.; Barile, V.L. Using Pregnancy-Associated Glycoproteins (PAGs) to Improve Reproductive Management: From Dairy Cows to Other Dairy Livestock. Animals 2022, 12, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, F.; Cabrera, F.; Batista, M.; Rodrı́guez, N.; Álamo, D.; Sulon, J.; Beckers, J.-F.; Gracia, A. A Comparison of Diagnosis of Pregnancy in the Goat via Transrectal Ultrasound Scanning, Progesterone, and Pregnancy-Associated Glycoprotein Assays. Theriogenology 2004, 62, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalha, E.S.; Sulon, J.; Figueiredo, J.R.; Beckers, J.F.; Espeschit, C.J.B.; Martins, R.; Silva, L.D.M. Plasma Profile of Pregnancy Associated Glycoprotein (PAG) in Pregnant Alpine Goats Using Two Radioimmunoassay (RIA) Systems. Small Ruminant Research 2001, 42, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, D.; Sulon, J.; Kane, Y.; Beckers, J.-F.; Leak, S.; Kaboret, Y.; De Sousa, N.M.; Losson, B.; Geerts, S. Effects of an Experimental Trypanosoma Congolense Infection on the Reproductive Performance of West African Dwarf Goats. Theriogenology 2004, 62, 1438–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, F.; Sulon, J.; Calero, P.; Batista, M.; Gracia, A.; Beckers, J.F. Pregnancy-Associated Glycoproteins (PAG) Detection in Milk Samples for Pregnancy Diagnosis in Dairy Goats. Theriogenology 2001, 56, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- zarrouk, A.; drion, P.V.; Drame, E.D.; Beckers, J.F. Pseudograstation Chez La Chèvre: Facteur d’infecondité. Ann. Med. Vet. 2000, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Haugejorden, G.; Waage, S.; Dahl, E.; Karlberg, K.; Beckers, J.F.; Ropstad, E. Pregnancy Associated Glycoproteins (PAG) in Postpartum Cows, Ewes, Goats and Their Offspring. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 1976–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrusfield, M. Veterinary Epidemiology, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Epitools, 2024. Available online: https://epitools.ausvet.com.au/oneproportion (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Silveira, D.C.; Vargas, S.F.; Oliveira, F.C.; Barbosa, R.M.; Knabah, N.W.; Goularte, K.L.; Vieira, A.D.; Baldassarre, H.; Gasperin, B.G.; Mondadori, R.G.; et al. Pharmacological Approaches to Induce Follicular Growth and Ovulation for Fixed-Time Artificial Insemination Treatment Regimens in Ewes. Animal Reproduction Science 2021, 228, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawy, I.; Hussain, S. Impact of Both Growth Hormone and Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone on Puberty Based on Serum Progesterone and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Level in Iraqi Local Breed Ewe Lambs. Egyptian Journal of Veterinary Sciences 2025, 56, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaro, M.F.A.; Santos, A.S.; Moura, L.F.G.M.; Fonseca, J.F.; Brandão, F.Z. Luteal Dynamic and Functionality Assessment in Dairy Goats by Luteal Blood Flow, Luteal Biometry, and Hormonal Assay. Theriogenology 2017, 95, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDEXX Laboratories Inc. Alertys* Ruminant Pregnancy Test Kit, 2019. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/idexx-ws-web-documents/org/lpd-web-insert/alertys%20ruminant%20pregnancy%20test-06-41169-14.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Kline, A.C.; Menegatti Zoca, S.; Epperson, K.M.; Quail, L.K.; Ketchum, J.N.; Andrews, T.N.; Rich, J.J.J.; Rhoades, J.R.; Walker, J.A.; Perry, G.A. Evaluation of Pregnancy Associated Glycoproteins Assays for on Farm Determination of Pregnancy Status in Beef Cattle. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Singh, S.P.; Bharadwaj, A. Temporal Changes in Circulating Progesterone and Pregnancy-Associated Glycoprotein Concentrations in Jakhrana Goats with Failed Pregnancy. Indian J of Anim Sci 2020, 90, 861–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, M.; Medina, J.; Calero, P.; González, F.; Quesada, E.; Gracia, A. Incidence and Treatment of Hydrometra in Canary Island Goats. Veterinary Record 2001, 149, 329–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Brom, R.; Klerx, R.; Vellema, P.; Lievaart-Peterson, K.; Hesselink, J.W.; Moll, L.; Vos, P.; Santman-Berends, I. Incidence, Possible Risk Factors and Therapies for Pseudopregnancy on Dutch Dairy Goat Farms: A Cross-sectional Study. Veterinary Record 2019, 184, 770–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes Júnior, E.S.; Cruz, J.F.; Teixeira, D.I.A.; Lima Verde, J.B.; Paula, N.R.O.; Rondina, D.; Freitas, V.J.F. Pseudopregnancy in Saanen Goats (Capra hircus) Raised in Northeast Brazil. Vet Res Commun 2004, 28, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, J.L.M. Vector Plus; 2001; pp. 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, E.P.B.X.; Santos, M.H.B.; Arruda, I.J.; Bezerra, F.Q.G.; Aguiar, F.C.R.; Neves, J.P.; Lima, P.F.; Oliveira, M.A.L. Hydrometra and Mucometra in Goats Diagnosed by Ultrasound and Treated with PGF2α. Medicina Veterinária (UFRPE) 2007, 1, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Nadolu, D.; Zamfir, C.; Anghel, A.; Ilisiu, E. Quantitative and Qualitative Variation of Saanen Goat Milk Keeped in Extended Lactation for Two Years. Czech Journal of Animal Science 2023.

- Zarrouk, A.; Engeland, I.; Sulon, J.; Beckers, J.F. Determination of Pregnancy-Associated Glycoprotein Concentrations in Goats (Capra hircus) with Unsuccessful Pregnancies: A Retrospective Study. Theriogenology 1999, 51, 1321–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yotov, S.; Branimir, S. Effect of GnRH Administration on Pregnancy-Associated Glycoproteins in Dairy Sheep with Different Reproductive Status. Acta Scientiae Veterinariae 2023. [CrossRef]

- Akköse, M.; Çinar, E.M.; Yazlik, M.O.; Çebi̇-Şen, Ç.; Polat, Y. Pregnancy-Associated Glycoprotein Concentrations during Early Gestation in Pregnant Awassi Sheep. Medycyna Weterynaryjna 2021, 77, 6564–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akköse, M.; Çınar, E.M.; Yazlık, M.O.; Kaya, U.; Polat, Y.; Çebi, Ç.; Özbeyaz, C.; Vural, M.R. Serum Pregnancy–Associated Glycoprotein Profiles during Early Gestation in Karya and Konya Merino Sheep. Veterinary Medicine & Sci 2024, 10, e1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szenci, O. Recent Possibilities for the Diagnosis of Early Pregnancy and Embryonic Mortality in Dairy Cows. Animals 2021, 11, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llewelyn, C.A.; Ogaa, J.S.; Obwolo, M.J. Plasma Progesterone Concentrations during Pregnancy and Pseudopregnancy and Onset of Ovarian activityPost Partum in Indigenous Goats in Zimbabwe. Trop Anim Health Prod 1992, 24, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadaev, M. Pregnancy Diagnosis Techniques in Goats – a Review. BJVM 2015, 18, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsas, D. Pregnancy Diagnosis in Goats. In Current Therapy in Large Animal Theriogenology; Youngquist RS, Threlfall WR: Saunders, Philadelphia, 2007; pp. 547–554. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, N.M.; Garbayo, J.M.; Figueiredo, J.R.; Sulon, J.; Gonçalves, P.B.D.; Beckers, J.F. Pregnancy-Associated Glycoprotein and Progesterone Profiles during Pregnancy and Postpartum in Native Goats from the North-East of Brazil. Small Ruminant Research 1999, 32, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, R.P.; Sutherland, W.D.; Sasser, R.G. Bovine Luteal Cell Production in Vitro of Prostaglandin E2, Oxytocin and Progesterone in Response to Pregnancy-Specific Protein B and Prostaglandin F2. Reproduction 1996, 107, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandiya, U.; Nagar, V.; Yadav, V.P.; Ali, I.; Gupta, M.; Dangi, S.S.; Hyder, I.; Yadav, B.; Bhakat, M.; Chouhan, V.S.; et al. Temporal Changes in Pregnancy-Associated Glycoproteins across Different Stages of Gestation in the Barbari Goat. Animal Reproduction Science 2013, 142, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, J.; Baril, G.; Azevedo, J.; Mascarenhas, R. Lifespan of a Luteinised Ovarian Cyst, Hormonal Profile and Uterine Ultrasonographic Appearance in a Cyclic Nulliparous Serrana Goat. In Reproduction in domestic animals; 2008; p. 43 (suppl 5), 88. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, N.M.; Ayad, A.; Beckers, J.F.; Gajewski, Z. Pregnancy-Associated Glycoproteins (PAG) as Pregnancy Markers in the Ruminants. J Physiol Pharmacol 2006, 57 Suppl 8, 153–171. [Google Scholar]

| Hormone | Reproductive status | P-value | Statistical power (α, σ, δ) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPG | NPG | PG | |||

| PAGs (ng/mL) | 0.08 ± 0.02 a | 0.13 ± 0.04 a | 1. 45 ± 0.04 b | < 0.001 | 1 (0.05, 0.13, 0.32) |

| P4 (S-N OD) | 6.76 ± 0.49 a | 0.69 ± 1.00 b | 8.15 ± 1.05 a | < 0.001 | 1 (0.05, 3.32, 2.38) |

| PAGs/P4 ratio | 0.01 ± 0.11 a | 0.24 ± 0.23 b | 0.18 ± 0.23 b | < 0.001 | 1 (0.05, 0.72, 1.25) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).