Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Examinations and Sampling

2.2. Quantification of P4, AMH, Hp in Sera

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hameed Ajafar, M.; Hasan Kadhim, A.; Mohammed AL-Thuwaini, T. The Reproductive Traits of Sheep and Their Influencing Factors. Reviews in Agricultural Science 2022, 10, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allabban, M.; Erdem, H. Koyunlarda Real-Time Ultrasonografik Muayene Ile Gebelik Tanısı. Journal of Bahri Dagdas Animal Research 2020, 9, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.K.; Reed, S.A. Benefits of Ultrasound Scanning during Gestation in the Small Ruminant. Small Ruminant Research 2017, 149, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karen, A.; Szabados, K.; Reiczigel, J.; Beckers, J.-F.; Szenci, O. Accuracy of Transrectal Ultrasonography for Determination of Pregnancy in Sheep: Effect of Fasting and Handling of the Animals. Theriogenology 2004, 61, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chundekkad, P.; Blaszczyk, B.; Stankiewicz, T. Embryonic Mortality in Sheep: A Review. Turk J Vet Anim Sci 2020, 44, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, P.R. Ovine Caesarean Operations: A Study of 137 Field Cases. British Veterinary Journal 1989, 145, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, P.R.; Murray, L.D.; Penny, C.D. A Preliminary Study of Serum Haptoglobin Concentration as a Prognostic Indicator of Ovine Dystocia Cases. British Veterinary Journal 1992, 148, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, J.; Brown, R.; Roberts, L. Bovine Haptoglobin Response in Clinically Defined Field Conditions. Veterinary Record 1991, 128, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cray, C.; Zaias, J.; Altman, N.H. Acute Phase Response in Animals: A Review. Comp Med 2009, 59, 517–526. [Google Scholar]

- Ulaankhuu, A.; Lkhamjav, G.; Nakamura, Y.; Zolzaya, M. Result of Studying Some Acute Phase Proteins and Cortisol in Pregnant Ewes. Mongolian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2017, 19, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alward, K.J.; Bohlen, J.F. Overview of Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) and Association with Fertility in Female Cattle. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2020, 55, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monniaux, D.; Drouilhet, L.; Rico, C.; Estienne, A.; Jarrier, P.; Touzé, J.-L.; Sapa, J.; Phocas, F.; Dupont, J.; Dalbiès-Tran, R.; et al. Regulation of Anti-Müllerian Hormone Production in Domestic Animals. Reprod Fertil Dev 2013, 25, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgut, A.O.; Koca, D. Anti-Müllerian Hormone as a Promising Novel Biomarker for Litter Size in Romanov Sheep. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2024, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasciu, V.; Nieddu, M.; Baralla, E.; Porcu, C.; Sotgiu, F.; Berlinguer, F. Measurement of Progesterone in Sheep Using a Commercial ELISA Kit for Human Plasma. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 2022, 34, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.N.Md.A. Hormonal Changes in the Uterus During Pregnancy—Lessons from the Ewe: A Review. Journal of Agriculture & Rural Development 2006, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, O.A.; Ahmed, N.K.; Taha, M.M.; Abedal-Majed, M.A.; Ali, F.M.; Samsudin, A.A. Reproductive Performance and Physiological Responses in Awassi Ewes Under Intravaginal Sponges Application and Fed Selenium and Vitamin E. Tropical Animal Science Journal 2024, 47, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, K.R.; Rickard, J.P.; Pini, T.; de Graaf, S.P. Exogenous Melatonin Advances the Ram Breeding Season and Increases Testicular Function. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, C.; Niu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F.; Li, F. An Intensive Milk Replacer Feeding Program Benefits Immune Response and Intestinal Microbiota of Lambs during Weaning. BMC Vet Res 2018, 14, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscos, C.; Samartzi, F.; Lymberopoulos, A.; Stefanakis, A.; Belibasaki, S. Assessment of Progesterone Concentration Using Enzymeimmunoassay, for Early Pregnancy Diagnosis in Sheep and Goats. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2003, 38, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

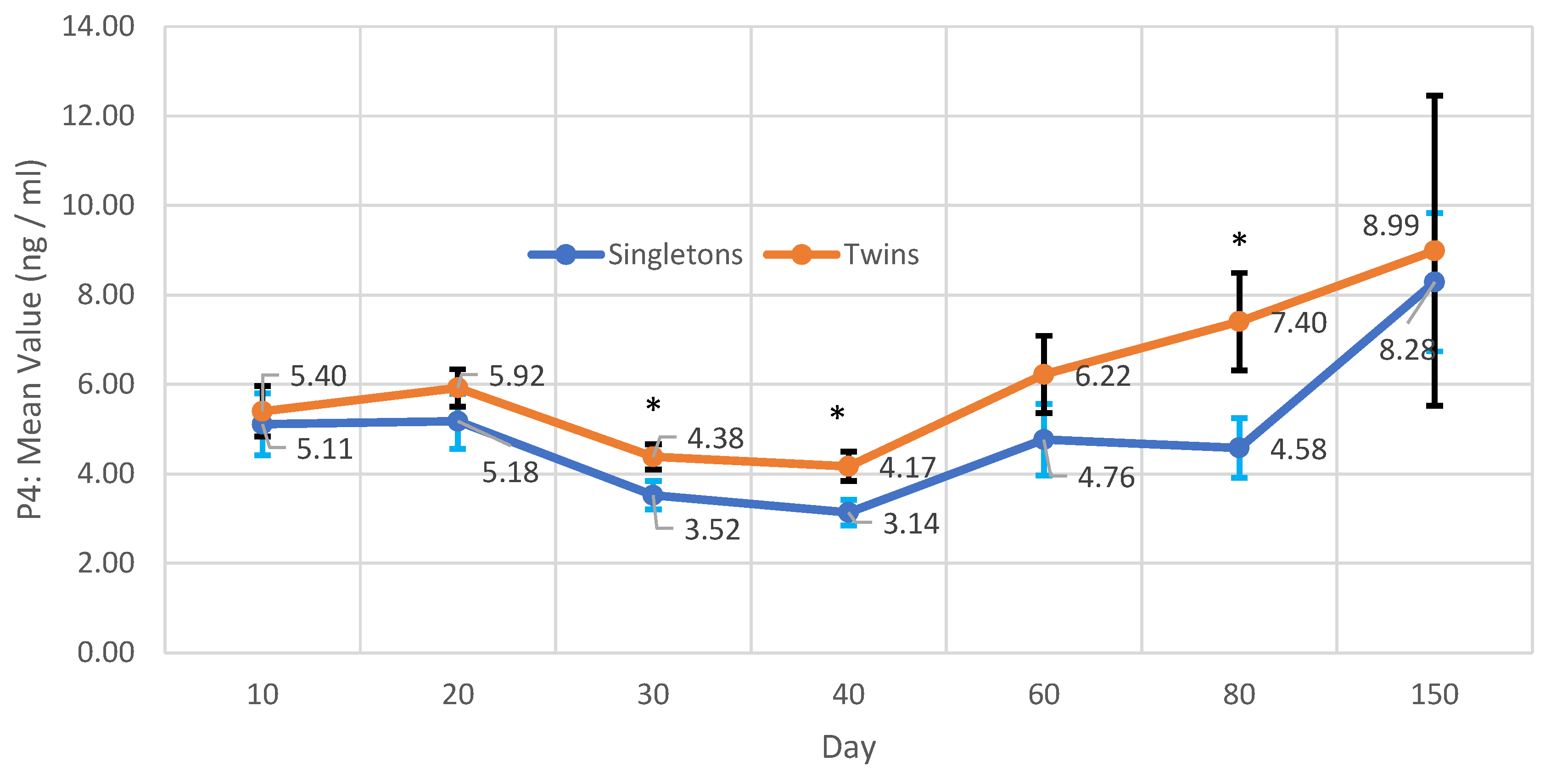

- Younis, L.; Akram, S. Assessing Progesterone Levels in Awassi Ewes: A Comparison between Pregnant and Non-Pregnant, Twins, and Singletons during the First Trimester. Egyptian Journal of Veterinary Sciences 2023, 54, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hümmelchen, H.; Wagner, H.; Brügemann, K.; König, S.; Wehrend, A. Effects of Breeding for Short-Tailedness in Sheep on Parameters of Reproduction and Lamb Development. Vet Med Sci 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukasa-Mugerwa, E.; Viviani, P. Progesterone Concentrations in Peripheral Plasma of Menz Sheep during Gestation and Parturition. Small Ruminant Research 1992, 8, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gubory, K.H.; Solari, A.; Mirman, B. Effects of Luteectomy on the Maintenance of Pregnancy, Circulating Progesterone Concentrations and Lambing Performance in Sheep. Reprod Fertil Dev 1999, 11, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammin, D.; Markey, B.; Bassett, H.; Buxton, D. The Ovine Placenta and Placentitis—A Review. Vet Microbiol 2009, 135, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, J.D.; McCoy, K. Weight, Composition, Mitosis, Cell Death and Content of Progesterone and DNA in the Corpus Luteum of Pregnancy in the Ewe. J Reprod Fertil 1988, 83, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaulfuss, K.H.; Giucci, E.; May, J. Influencing Factors on the Level of the Ovulation Rate in Sheep during the Main Breeding Season--an Ultrasonographic Study. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr 2003, 110, 445–450. [Google Scholar]

- Karen, A.; Beckers, J.-F.; Sulon, J.; de Sousa, N.M.; Szabados, K.; Reczigel, J.; Szenci, O. Early Pregnancy Diagnosis in Sheep by Progesterone and Pregnancy-Associated Glycoprotein Tests. Theriogenology 2003, 59, 1941–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mousawe, A.; Ibrahim, N. Diagnosis of Pregnancy in Iraqi Awassi Ewes Through Progesterone Hormone Measurement and Ultrasonography Following Induction of Fertile Estrus with Sulpiride. Egyptian Journal of Veterinary Sciences 2024, 55, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, L.; Aboud, Q. Evaluate the Effectiveness of Pregnancy-Associated Glycoprotein and Progesterone in Predicting the Gestational Status in Goats. University of Thi-Qar Journal of Agricultural Research 2023, 12, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, R.S.; Memon, M.A. Breeding Soundness Examinations of Rams and Bucks, a Review. Theriogenology 1980, 13, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Chakraborty, D.; Gupta, P.; Khan Nusrat, N.; Saba, B. Factors Affecting Performance Traits in Kashmir Merino Sheep. Journal of Animal Research 2012, 2, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J.R.; Thompson, J.A.; Perkins, N.R. Factors Affecting Pregnancy Rates Following Laparoscopic Insemination of 28,447 Merino Ewes under Commercial Conditions: A Survey. Theriogenology 1998, 49, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Brun, V.; Meikle, A.; Fernández-Foren, A.; Forcada, F.; Palacín, I.; Menchaca, A.; Sosa, C.; Abecia, J.-A. Failure to Establish and Maintain a Pregnancy in Undernourished Recipient Ewes Is Associated with a Poor Endocrine Milieu in the Early Luteal Phase. Anim Reprod Sci 2016, 173, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, N.W.; Rowson, L.E.A.; Short, R.V. Egg Transfer in Sheep. Factors Affecting the Survival and Development of Transferred Eggs. Reproduction 1960, 1, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlivan, T.D.; Martin, C.A.; Taylor, W.B.; Cairney, I.M. Estimates of Pre- and Perinatal Mortality in the New Zealand Romney Marsh Ewe. I. Pre- and Perinatal Mortality in Those Ewes That Conceived to One Service. J Reprod Fertil 1966, 11, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, A.B.; Knights, M.; Winkler, J.L.; Marsh, D.J.; Pate, J.L.; Wilson, M.E.; Dailey, R.A.; Seidel, G.; Inskeep, E.K. Patterns of Late Embryonic and Fetal Mortality and Association with Several Factors in Sheep1. J Anim Sci 2007, 85, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humblot, P. Use of Pregnancy Specific Proteins and Progesterone Assays to Monitor Pregnancy and Determine the Timing, Frequencies and Sources of Embryonic Mortality in Ruminants. Theriogenology 2001, 56, 1417–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.R.; Andrade, J.P.N.; Cunha, T.O.; Madureira, G.; Moallem, U.; Gomez-Leon, V.; Martins, J.P.N.; Wiltbank, M.C. Is Pregnancy Loss Initiated by Embryonic Death or Luteal Regression? Profiles of Pregnancy-Associated Glycoproteins during Elevated Progesterone and Pregnancy Loss. JDS Communications 2023, 4, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaskous, S.; Gottschalk, J.; Hippel, T.; Grün, E. The Behavior of Growth-Influencing and Steroid Hormones in the Blood Plasma during Pregnancy of Awassi Sheep in Syria. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr 2003, 116, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kulcsár, M.; Dankó, G.; Magdy, H.G.I.; Reiczigel, J.; Forgach, T.; Proháczik, A.; Delavaud, C.; Magyar, K.; Chilliard, Y.; Solti, L.; et al. Pregnancy Stage and Number of Fetuses May Influence Maternal Plasma Leptin in Ewes. Acta Vet Hung 2006, 54, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gür, S.; Türk, G.; Demirci, E.; Yüce, A.; Sönmez, M.; Özer, Ş.; Aksu, E. Effect of Pregnancy and Foetal Number on Diameter of Corpus Luteum, Maternal Progesterone Concentration and Oxidant/Antioxidant Balance in Ewes. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2011, 46, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manalu, W.; Sumaryadi, M.Y.; Kusumorini, N. Effect of Fetal Number on the Concentrations of Circulating Maternal Serum Progesterone and Estradiol of Does during Late Pregnancy. Small Ruminant Research 1997, 23, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricketts, A.P.; Flint, A.P.F. Onset of Synthesis of Progesterone by Ovine Placenta. Journal of Endocrinology 1980, 86, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takarkhede, R.C.; Honmode, J.D.; Kadu, M.S. Seasonal Variations in Estradiol-17f3 and Progesterone Level during Oestrus Cycle in Malpura Ewes. Indian Journal of Animal Sciences 2002, 72, 296–299. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, T.E.; Burghardt, R.C.; Johnson, G.A.; Bazer, F.W. Conceptus Signals for Establishment and Maintenance of Pregnancy. Anim Reprod Sci 2004, 82–83, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman, R.A.; Yake, H.K.; Snider, A.P.; Lents, C.A.; Murphy, T.W.; Freking, B.A. An Extreme Model of Fertility in Sheep Demonstrates the Basis of Controversies Surrounding Antral Follicle Count and Circulating Concentrations of Anti-Müllerian Hormone as Predictors of Fertility in Ruminants. Anim Reprod Sci 2023, 259, 107364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, J.; Smith, H.; McGrice, H.A.; Kind, K.L.; van Wettere, W.H.E.J. Towards Improving the Outcomes of Assisted Reproductive Technologies of Cattle and Sheep, with Particular Focus on Recipient Management. Animals 2020, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, J.L.H.; Scheetz, D.; Jimenez-Krassel, F.; Themmen, A.P.N.; Ward, F.; Lonergan, P.; Smith, G.W.; Perez, G.I.; Evans, A.C.O.; Ireland, J.J. Antral Follicle Count Reliably Predicts Number of Morphologically Healthy Oocytes and Follicles in Ovaries of Young Adult Cattle1. Biol Reprod 2008, 79, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Krassel, F.; Scheetz, D.M.; Neuder, L.M.; Ireland, J.L.H.; Pursley, J.R.; Smith, G.W.; Tempelman, R.J.; Ferris, T.; Roudebush, W.E.; Mossa, F.; et al. Concentration of Anti-Müllerian Hormone in Dairy Heifers Is Positively Associated with Productive Herd Life. J Dairy Sci 2015, 98, 3036–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, E.S.; Bisinotto, R.S.; Lima, F.S.; Greco, L.F.; Morrison, A.; Kumar, A.; Thatcher, W.W.; Santos, J.E.P. Plasma Anti-Müllerian Hormone in Adult Dairy Cows and Associations with Fertility. J Dairy Sci 2014, 97, 6888–6900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossa, F.; Carter, F.; Walsh, S.W.; Kenny, D.A.; Smith, G.W.; Ireland, J.L.H.; Hildebrandt, T.B.; Lonergan, P.; Ireland, J.J.; Evans, A.C.O. Maternal Undernutrition in Cows Impairs Ovarian and Cardiovascular Systems in Their Offspring1. Biol Reprod 2013, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossa, F.; Evans, A.C.O. Review: The Ovarian Follicular Reserve—Implications for Fertility in Ruminants. animal 2023, 17, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinshead, F.; Walker, C.; Hanlon, D. Determination of the Normal Reference Interval for Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) in Bitches and Use of AMH as a Potential Predictor of Litter Size. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2017, 52, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evci, E.C.; Aslan, S.; Schäfer-Somi, S.; Ergene, O.; Sayıner, S.; Darbaz, I.; Seyrek-İntaş, K.; Wehrend, A. Monitoring of Canine Pregnancy by Considering Anti-Mullerian Hormone, C-Reactive Protein, Progesterone and Complete Blood Count in Pregnant and Non-Pregnant Dogs. Theriogenology 2023, 195, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, J.; Roberts, L. Haptoglobin as an Indicator of Infection in Sheep. Veterinary Record 1994, 134, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, J.F.; Hernández, Á.; Meeusen, E.N.T.; Rodríguez, F.; Molina, J.M.; Jaber, J.R.; Raadsma, H.W.; Piedrafita, D. Fecundity in Adult Haemonchus Contortus Parasites Is Correlated with Abomasal Tissue Eosinophils and Γδ T Cells in Resistant Canaria Hair Breed Sheep. Vet Parasitol 2011, 178, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albay, M.K.; Karakurum, M.C.; Sahinduran, S.; Sezer, K.; Yildiz, R.; Buyukoglu, T. Selected Serum Biochemical Parameters and Acute Phase Protein Levels in a Herd of Saanen Goats Showing Signs of Pregnancy Toxaemia. Vet Med (Praha) 2014, 59, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narin, K.; Aytekin, İ. Paraoxonase, Haptoglobin, Serum Amyloid A, Tumor Necrosis Factor and Acetylcholinesterase Levels in Ewes with Pregnancy Toxemia. Turkish Journal of Veterinary Research 2024, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greguła-Kania, M.; Kosior-Korzecka, U.; Hahaj-Siembida, A.; Kania, K.; Szysiak, N.; Junkuszew, A. Age-Related Changes in Acute Phase Reaction, Cortisol, and Haematological Parameters in Ewes in the Periparturient Period. Animals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurell, T.E.; Bane, D.P.; Hall, W.F.; Schaeffer, D.J. Serum Haptoglobin Concentration as an Indicator of Weight Gain in Pigs. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research 1992, 56, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Iliev, P.; Georgieva, T. Acute Phase Proteins in Sheep and Goats—Function, Reference Ranges and Assessment Methods: An Overview. Bulg J Vet Med 2018, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

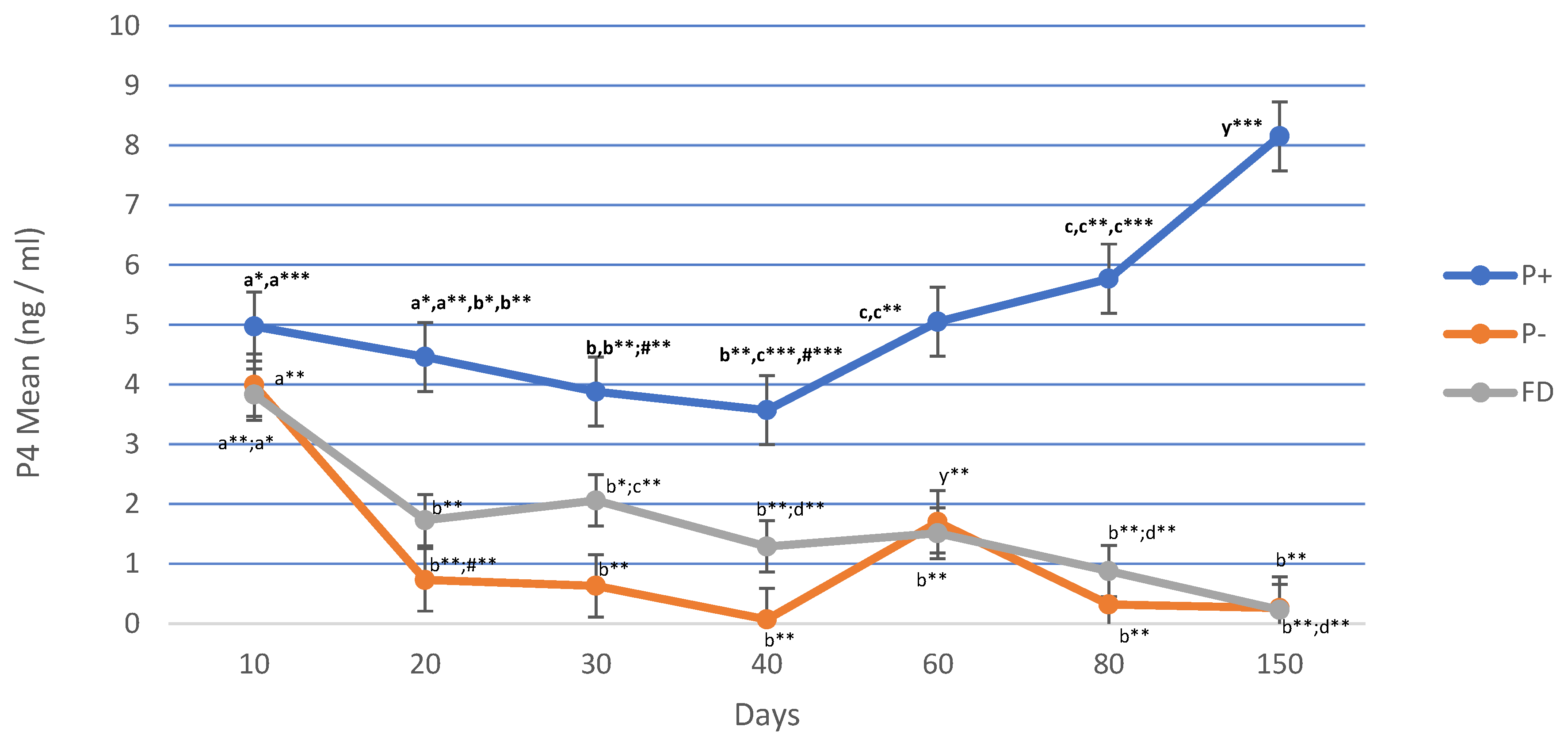

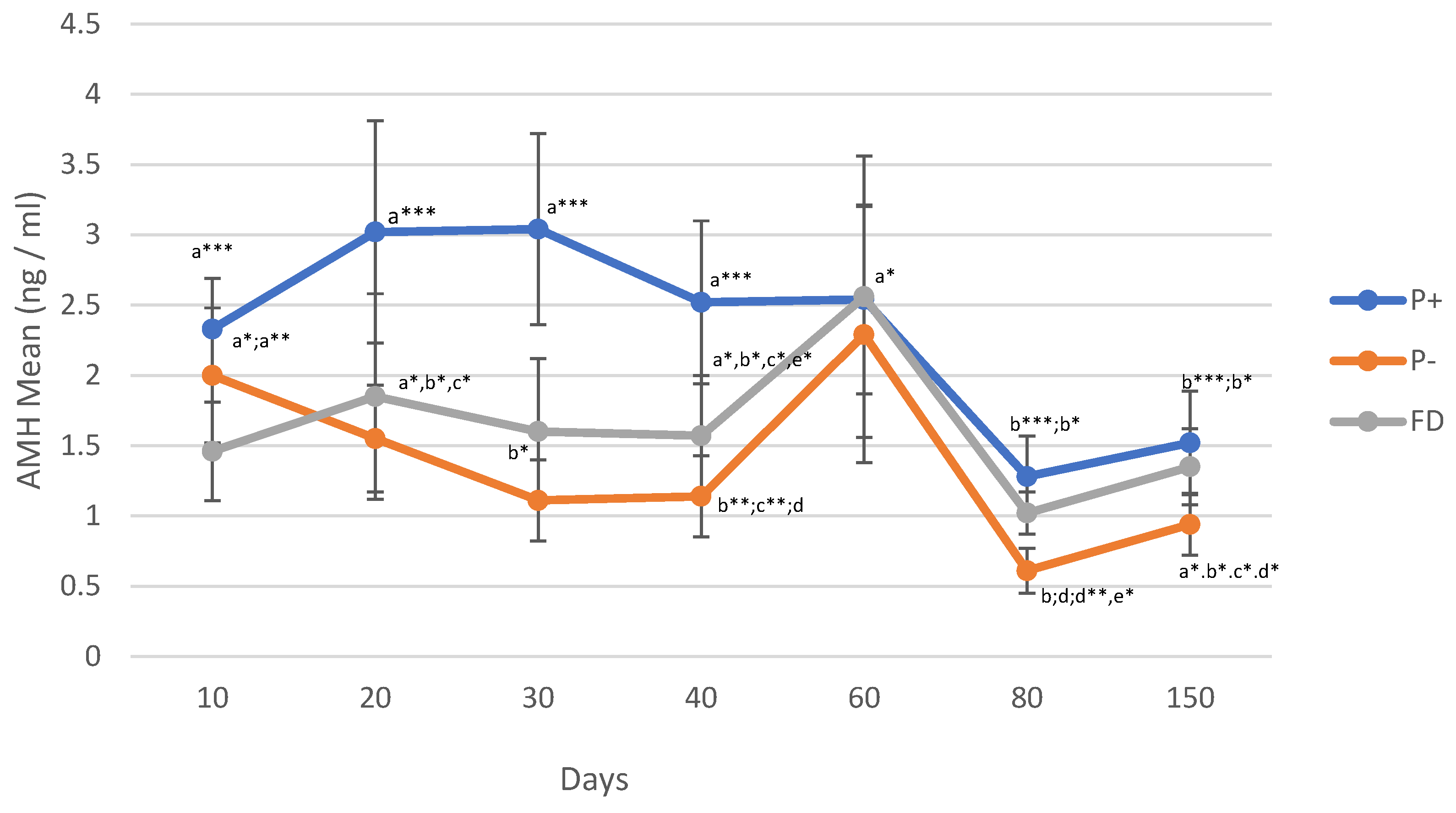

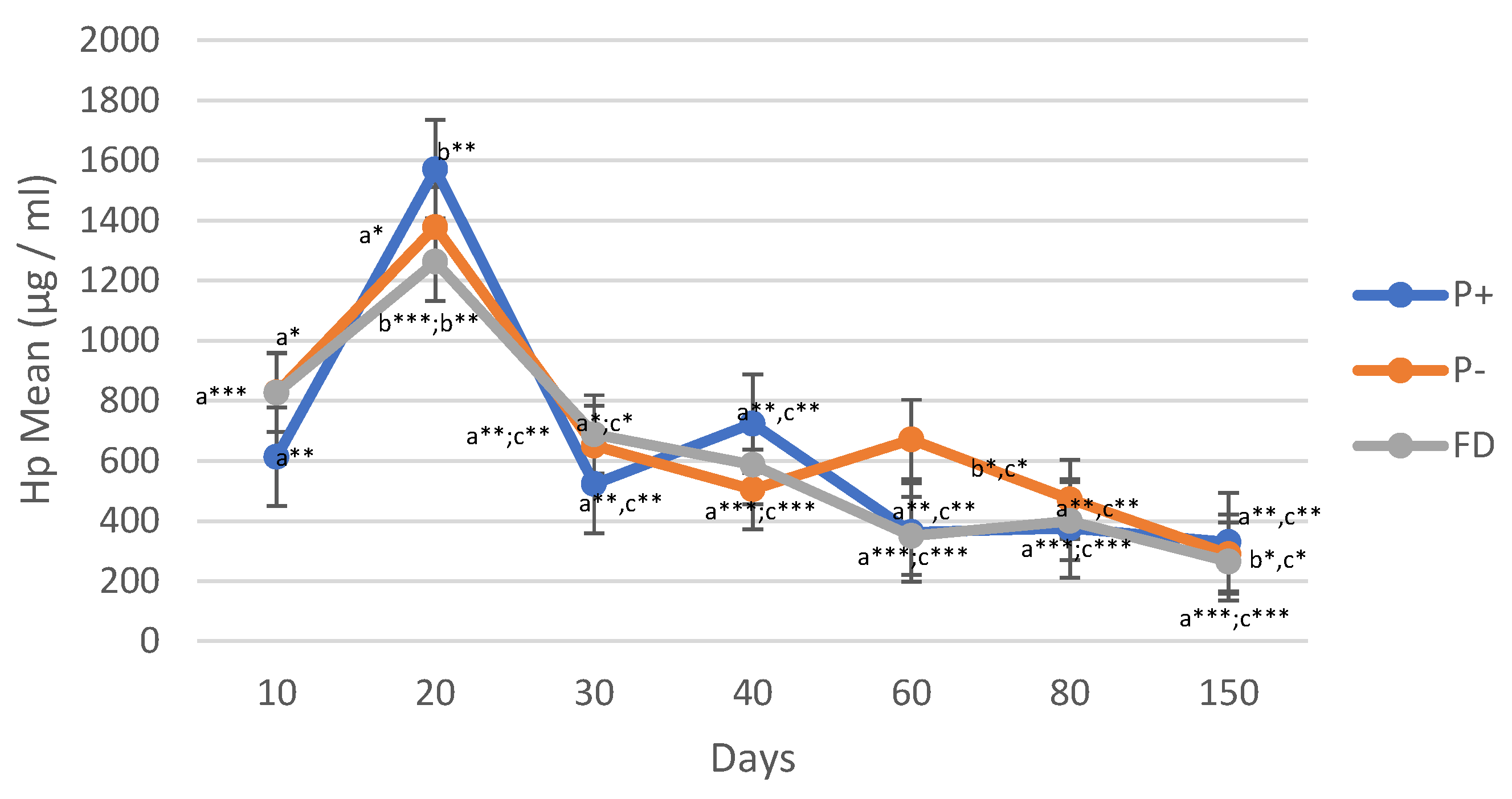

| P4 (ng/mL) | AMH (ng/mL) | Hp (µg/ml) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAYS | P+ | P- | p | P+ | P- | p | P+ | P- | p |

| 10 | 4.97±0.50 | 3.99±0.74 | n.s. | 2.33±0.36 | 2.00±0.48 | n.s. | 613.92±88.46 | 827.42±196.72 | n.s. |

| 20 | 4.46±0.57(a***) | 0.73±0.39(b***) | *** p < 0.0001 | 3.02±0.79 | 1.55±0.38 | n.s. | 1570.51±206.54 | 1378.27±296.17 | n.s. |

| 30 | 3.88±0.23(a***) | 0.63±0.46(b***) | *** p < 0.0001 | 3.04±0.68(s**) | 1.11±0.29 b**) | p < 0.01 | 523.13±131.71 | 650.83±202.15 | n.s. |

| 40 | 3.57±0.24(a***) | 0.07±0.01(b***) | *** p < 0.0001 | 2.52±0.58 | 1.14±0.29 | n.s. | 724.33±166.61 | 505.48±110.85 | n.s. |

| 60 | 5.05±0.63(a**) | 1.70±0.75(b**) | ** p < 0.0001 | 2.54±0.67 | 2.29±0.91 | n.s. | 362.65±85.75 | 671.17±167.98 | n.s. |

| 80 | 5.77±0.67(a***) | 0.32±0.16(b***) | *** p < 0.0001 | 1.28±0.29 | 0.61±0.16 | n.s. | 375.72±60.59 | 471.86±130.36 | n.s. |

| 150 | 8.15±1.67(a***) | 0.26 ±0.09(b***) | *** p < 0.0001 | 1.52±0.37 | 0.94±0.22 | n.s. | 329.65±31.65 | 289.90±72.63 | n.s. |

| P4 (ng/mL) | AMH (ng/mL) | Hp (µg/ml) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAYS | P- | FD | p | P- | FD | p | P- | FD | p |

| 10 | 3.99±0.74 | 3.83±0.59 | n.s | 2.00±0.48 | 1.46±0.35 | n.s | 827.42±196.72 | 826.76±255.12 | n.s |

| 20 | 0.73±0.39(a*) | 1.73±0.4(b*) | p < 0.05 | 1.55±0.38 | 1.85±0.73 | n.s | 1378.27±296.17 | 1262.95±211.74 | n.s |

| 30 | 0.63±0.46(a**) | 2.06±0.40(b**) | p < 0.01 | 1.11±0.29 | 1.60±0.52 | n.s | 650.83±202.15 | 688.91±214.04 | n.s |

| 40 | 0.07±0.01(a**) | 1.29±0.36(b**) | p < 0.01 | 1.14±0.2 | 1.57±0.43 | n.s | 505.48±110.85 | 586.84±142.42 | n.s |

| 60 | 1.70±0.75(a**) | 1.51±0.43(b**) | p < 0.01 | 2.29±0.91 | 2.56±1.00 | n.s | 671.17±167.98 | 350.08±64.88 | n.s |

| 80 | 0.32±0.16 | 0.88±0.37 | n.s | 0.61±0.16 | 1.02±0.15 | n.s | 471.86±130.36 | 399.90±82.29 | n.s |

| 150 | 0.26±0.09 | 0.23±0.06 | n.s | 0.94±0.22 | 1.35±0.27 | n.s | 289.90±72.63 | 264.96±34.59 | n.s |

| P4 (ng/mL) | AMH (ng/mL) | Hp (µg/ml) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAYS | P+ | FD | p | P+ | FD | p | P+ | FD | p |

| 10 | 4.97±0.50 | 3.83±0.59 | n.s | 2.33±0.36(a*) | 1.46±0.35(b) | n.s | 613.92±88.46 | 826.76±255.12 | n.s |

| 20 | 4.46±0.57(a**) | 1.73±0.47(b**) | ** p < 0.01 | 3.02±0.79(a*) | 1.85±0.73(b) | n.s | 1570.51±206.54 | 1262.95±211.74 | n.s |

| 30 | 3.88±0.23(a***) | 2.05±0.40(b***) | *** p < 0.001 | 3.04±0.68(a*) | 1.60±0.52(b*) | *p < 0.01 | 523.13±131.71 | 688.91±214.04 | n.s |

| 40 | 3.57±0.24(a***) | 1.28±0.36(b***) | **** p < 0.0001 | 2.52±0.58 | 1.57±0.43 | n.s | 724.33±166.61 | 586.84±142.42 | n.s |

| 60 | 5.05±0.63(a***) | 1.51±0.43(b***) | **** p < 0.0001 | 2.54±0.67 | 2.56±1.00 | n.s | 362.65±85.75 | 350.08±64.88 | n.s |

| 80 | 5.77±0.67(a***) | 0.88±0.37(b***) | **** p < 0.0001 | 1.28±0.29 | 1.02±0.15 | n.s | 375.72±60.59 | 399.90±82.29 | n.s |

| 150 | 8.15±1.67(a***) | 0.23±0.06(b***) | **** p < 0.0001 | 1.52±0.37 | 1.35±0.27 | n.s | 329.65±31.65 | 264.96±34.59 | n.s |

| P4 (ng/mL) | AMH (ng/mL) | Hp (µg/ml) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Months | P+ | P- | FD | P+ | P- | FD | P+ | P- | FD | |

| A2 | 4.46±0.19(a***) | 1.35±0.3 (a) | 2.23±0.26 (a**,a***) |

2.52±0.29 (a*, a***) | 1.5±0.19(a) | 1.62±0.26(a) | 857.97±89.78 (a***) |

840.50±116.90(a;b**) | 841.37±108.23 (a*) |

|

| A4 | 5.56±0.45(b***) | 1.01±0.41(a) | 1.20±0.29(b**) | 1.91±0.38(b*) | 1.5±0.50(a) | 1.79±0.52(a) | 369.19±51.79(b***) | 571.52±105.88(a) | 374.99±51.51(b*) | |

| A6 | 8.60±1.71 (b***,c**) |

0.26±0.09(a) | 0.23±0.06 (b***) |

8.15±1.67 (b*,c***) |

0.9±0.22(a) | 1.36±0.27(a) | 329.65±31.65(b***, c**) | 289.90±72.63(c**) | 264.96 ±34.59(b*; c*) | |

| Weight measurement days (days) | Weights | P4 | AMH | Hp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 67.26±6.71 | 4.97±0.50(a*) | 2.39±0.36(a***;a**) | 613.91±88.46(a*;a**) |

| 80 | 76.18±8.98 | 5.77±0.66(a*) | 1.27±0.29(b***) | 375.72±60.58(b*) |

| 150 | 86.15±9.14 | 8.15±1.67(a*) | 1.52±0.37(b**) | 329.64±31.64(b*;b**) |

| p | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 | a**:b** p < 0.01 a***:b*** p < 0.001 |

a*:b* p < 0.05 a**:b** p < 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).