2.1. Thought Experiment

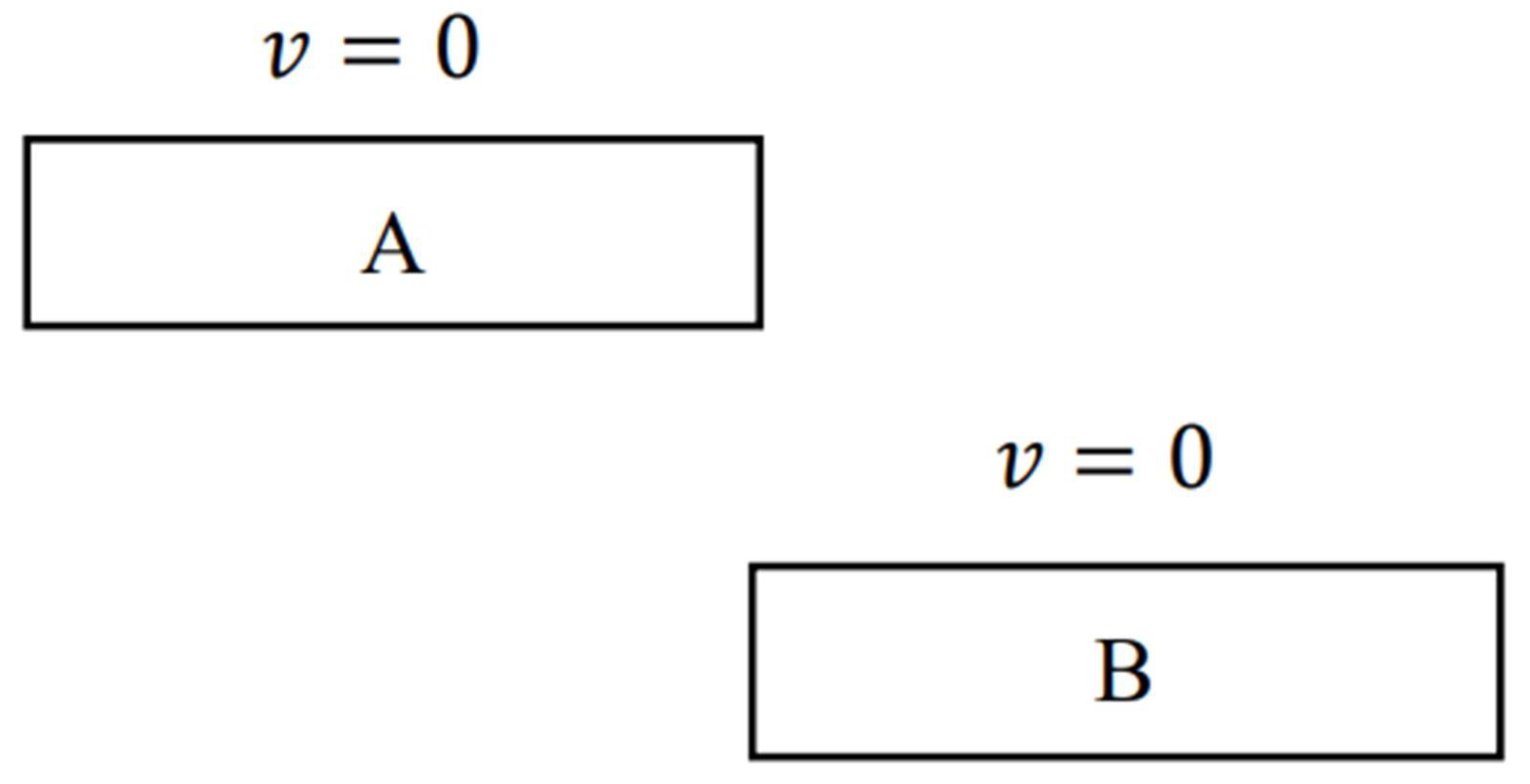

We presuppose two inertial frames of reference,

and

, that are in a state of uniform relative motion to each other.

moves with constant velocity

in the positive direction of the

axis in

. Moreover, assume that the two objects having the same rest mass (RM) and the same size, in

, move parallel to the

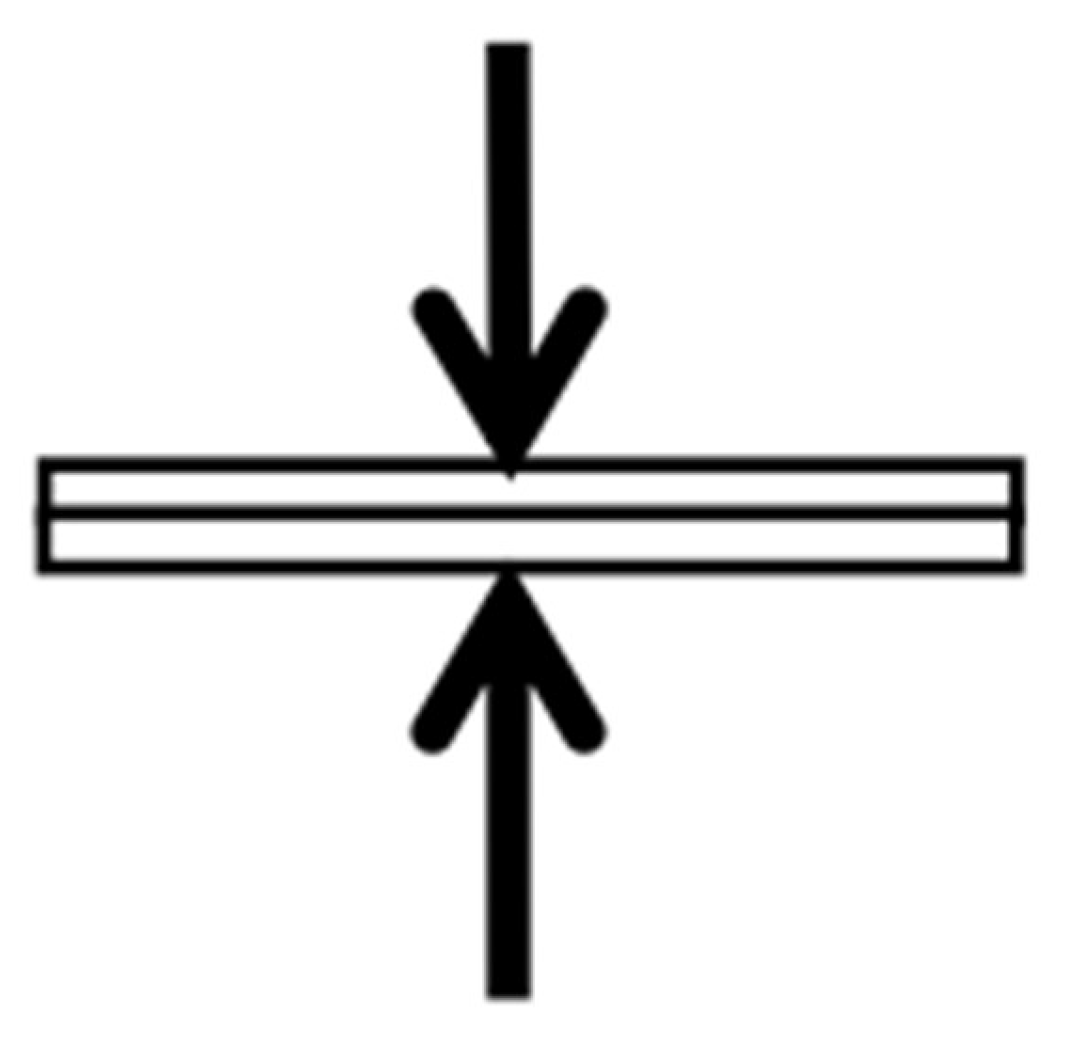

-axis from opposite directions and with the same speed as shown in

Figure 1. Those velocities are

and

, respectively. The two objects are symmetrical to the

-axis, and they are located very close to it. Each length in the direction of travel of the objects is much longer than that perpendicular to the direction of travel of them. Let

-axis be the axis perpendicular to the

-axis. In addition, assume that the origin of the

-axis is on the

-axis.

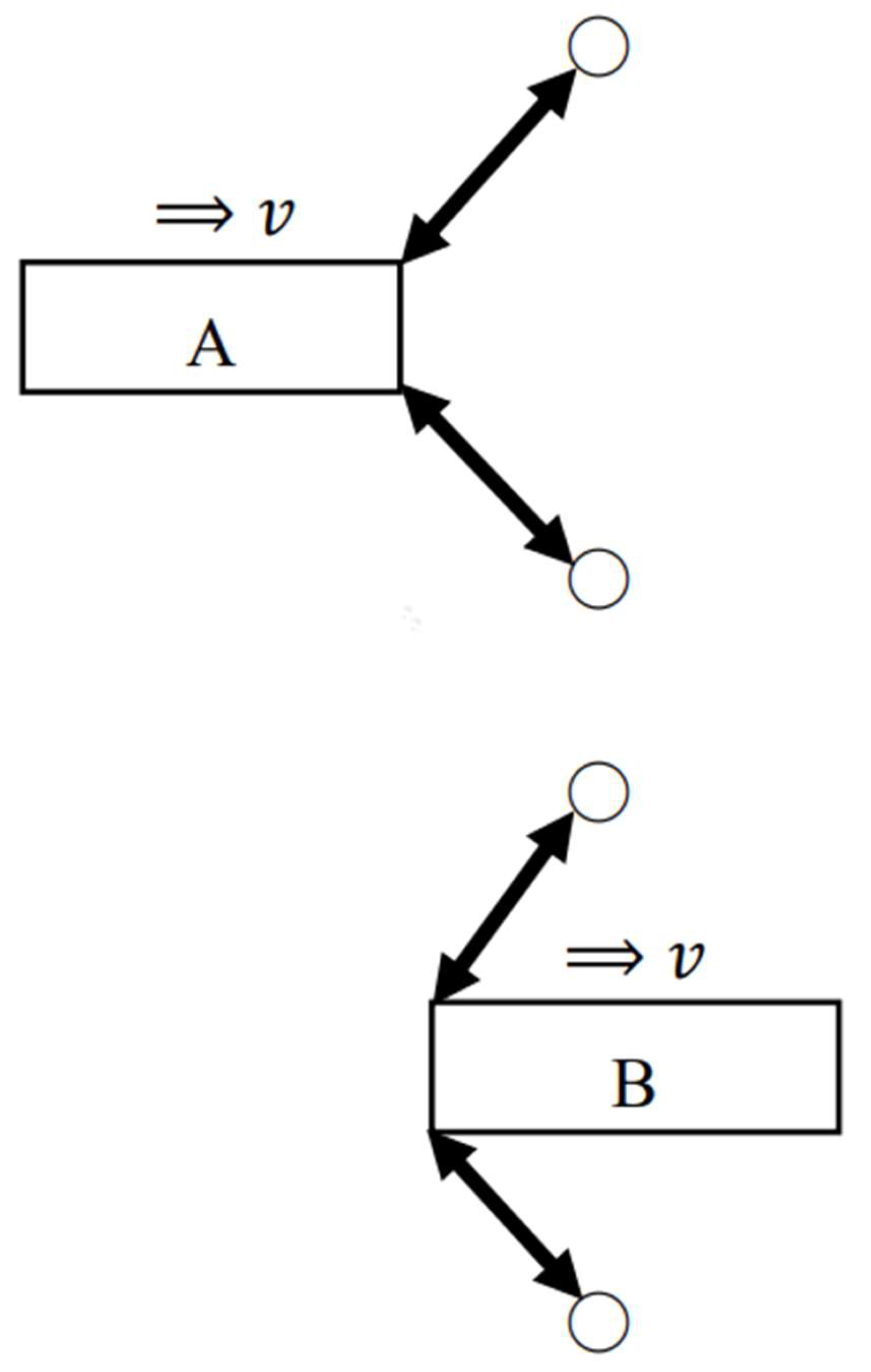

When the objects become perfectly symmetric with respect to the

-axis, as shown in

Figure 2, the forces perpendicular to the direction of travel of them are applied to the CRE of each object in the MIFR. The forces result in a perfectly inelastic collision between the objects and thereby they combine. Here, as shown in

Figure 2, the length in the direction of the

-axis of the CO is extremely short compared to that along the

-axis.

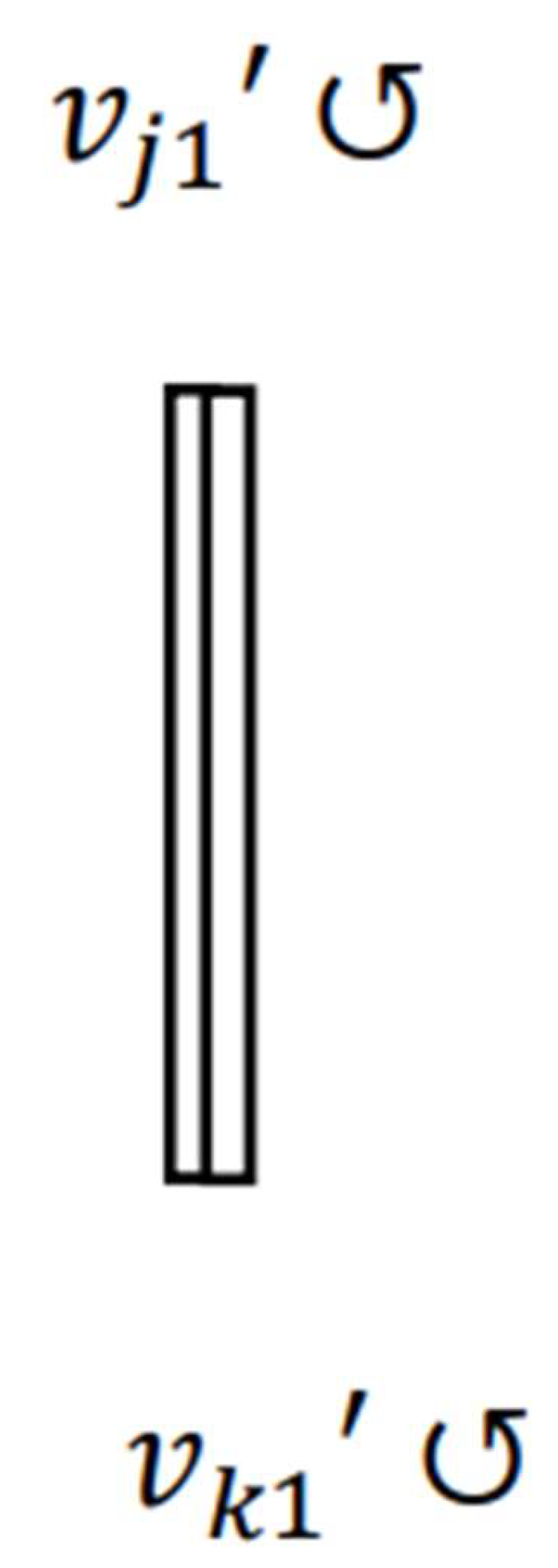

After the objects combine, the translational motion of each object stops, and a recoilless rotational motion of the CO occurs counterclockwise as shown in

Figure 3. The reason for this is that each momentum of the objects before the combination between them acts like the moment of force on the CO. Suppose that this rotational motion takes place around

. When the CO rotates and becomes perpendicular to the

-axis, the distribution of RM of the CO is symmetric with respect to the

-axis. Let

be a velocity of a MP of the CO that lies in the range where

. Similarly, let

be a velocity of a MP of the CO that exists in the range where

. Suppose that a MP with

and one with

are symmetrical with respect to the

-axis. When observed from

,

and

of each MP are opposite in direction but equal in magnitude, i.e.,

.

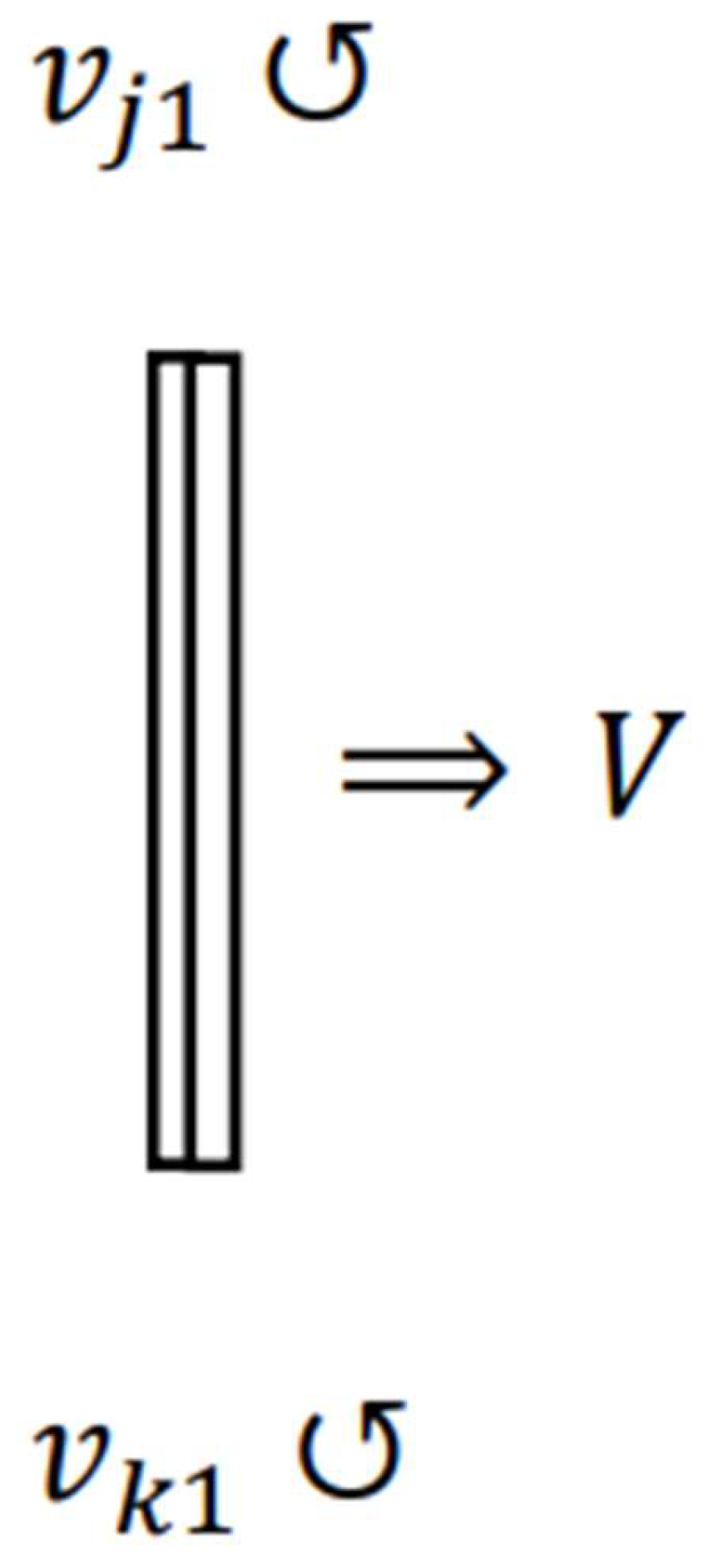

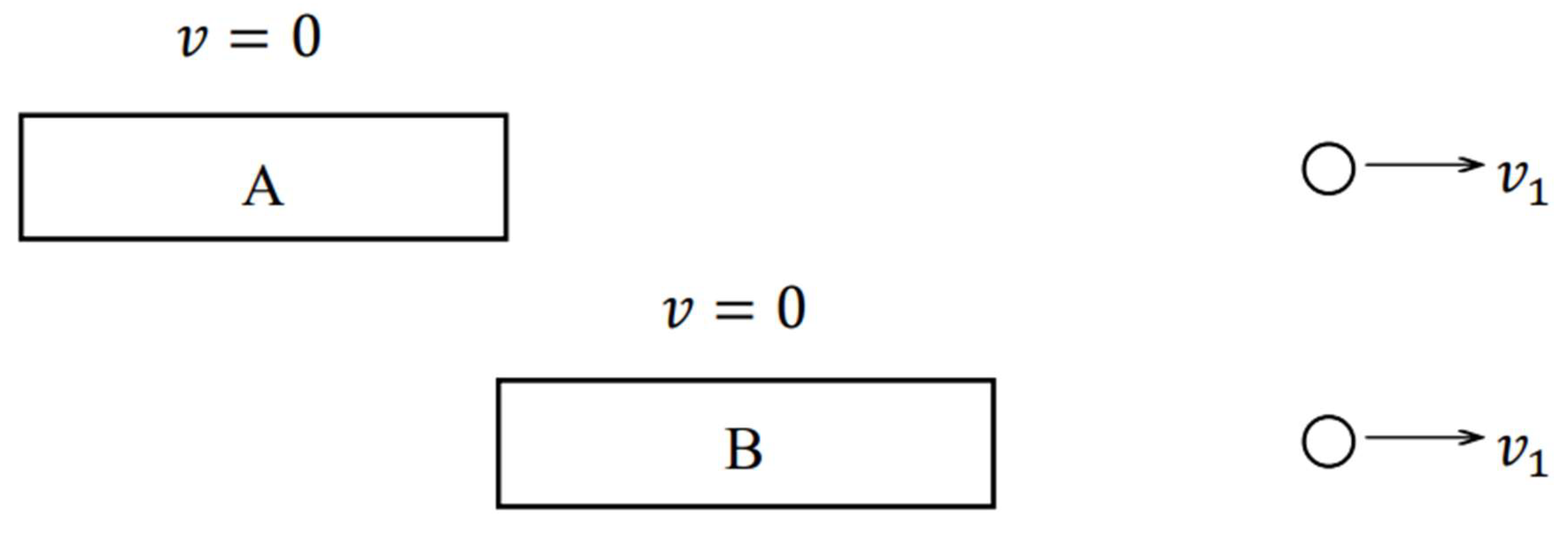

We will observe these phenomena from

. Suppose that, when observed from

,

. Then, as shown in

Figure 4, the object on the right is stationary, and that on the left is moving at a velocity

parallel to the

-axis.

Here is expressed as based on the law of velocity addition in SR. For simplicity, if we assume that all velocities here are non-relativistic those which Newtonian mechanics is applicable, .

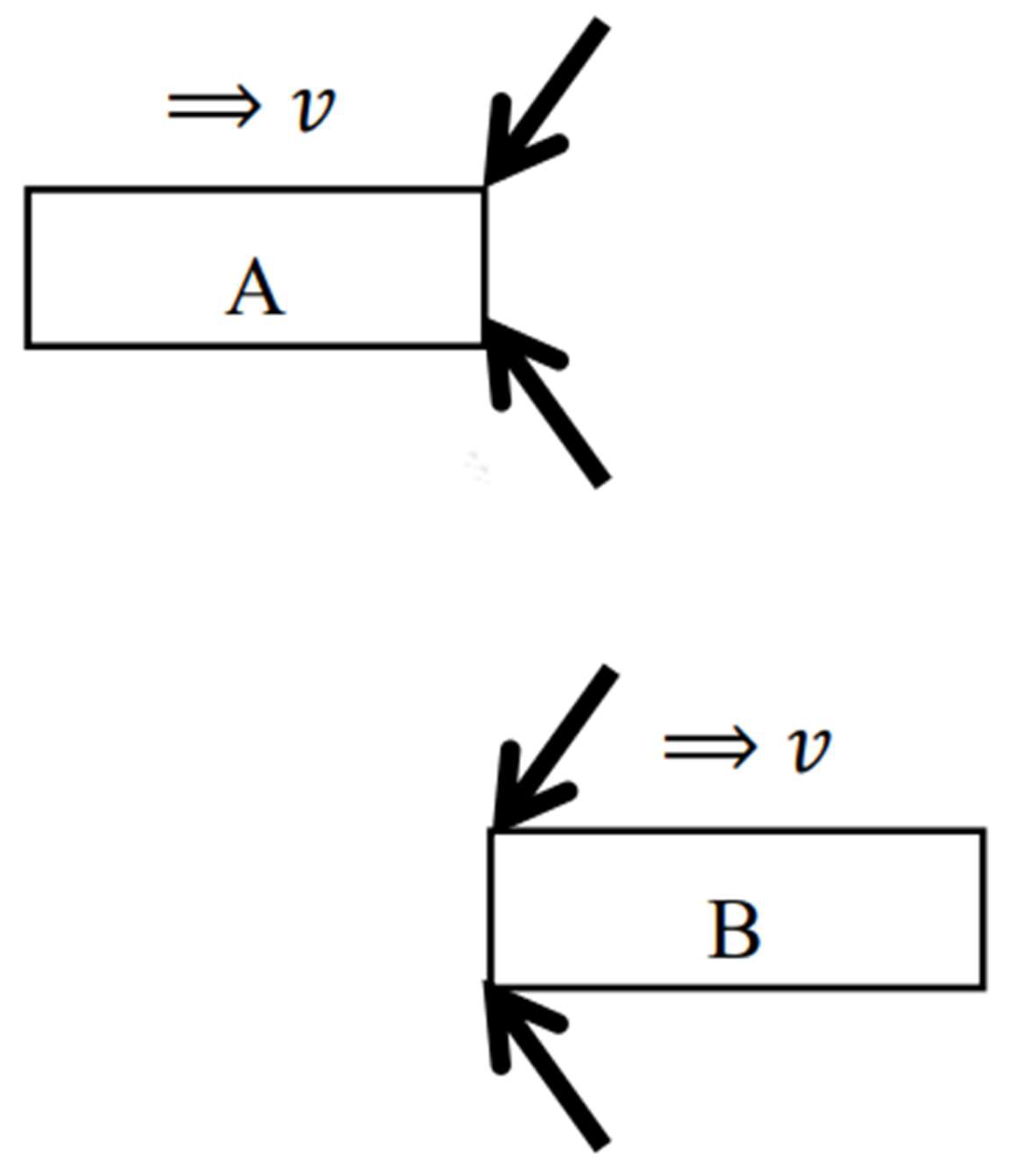

After a perfectly inelastic collision between the objects occurs, the CO starts rotating around

. When the CO rotates and becomes perpendicular to the

-axis, the length in the direction of the

-axis of the CO is extremely short as shown in

Figure 5. On the other hand, the center of RM of the CO moves at

in the positive direction of the

-axis in

since its center of RM is stationary in

. This is also shown in

Figure 5. Here let

be a velocity of a MP of the CO in the range where

. This corresponds to

in

. In addition, let

be a velocity of a MP of the CO in the range where

. This corresponds to

in

. Here it is assumed that a MP with

and one with

are symmetrical with respect to the

-axis. When observed from

,

and

of each MP are different in magnitude depending on whether the x-component of each rotational velocity is the same or opposite to the direction of travel of the CO.

2.2. Numerical Calculation of the CE Based on Newtonian Mechanics

For simplicity, we perform the numerical calculation for the CE in the above thought experiment based on Newtonian mechanics. We examine the location of the CE (LCE) before and after the combination of two objects. Let be the RM. Since the rest energy of the CO remains symmetrical with respect to the -axis, we will calculate only its kinetic energy, KE, , by substituting concrete values. Here, the units of various physical quantities will be omitted. The energy produced by the perfectly inelastic collision that becomes thermal energy leads to an increase in the RM of the object. This increase is symmetric with respect to the -axis.

We assume that each object consists of 10 minute portions (MPs) which have the same RM and shape respectively in

. Each object in

Figure 1 consists of 10 equal MPs parallel to

-axis. Each MP has a RM of 1 and is a square with side 1 on the

-

plane. Each object has a RM of

, so the sum of the two is

. Since each object is moving at the uniform velocity of

or

along the

-axis, the velocities of the MPs are also

or

respectively. Let

and

be the distance from the

-axis to the center of each object and assume that they are

and

0.5 respectively.

We analyze the physical quantities of the object that becomes perpendicular to the

-axis due to the rotational motion after the combination. The CO in

Figure 3, which has the length of 10 in the direction perpendicular to the

-axis, consists of 10 equal MPs parallel to the

-axis. Each MP has a length of 1 in the direction perpendicular to the

-axis and a length of 2 in the direction of the

-axis. The RM of each MP, which is generated by the combination of two objects, becomes

. In the direction perpendicular to the

-axis, the centers of each MP are located at distances of

, 3.5, 2.5, 1.5, 0.5,

0.5,

1.5,

2.5,

3.5, and

4.5 from the center of rotation, in other words, the

-axis.

The circumferences of the centers of the MPs at positions of 4.5 and 0.5 when they rotate once are 9.0 and 1.0, respectively. Hence, the angular velocity of the former is 9.0 times that of the latter. Similarly, the angular velocity of the MP at 4.5 is approximately 1.3, 1.8 and 3.0 times the angular velocities of the MPs at 3.5, 2.5 and 1.5, respectively. If we assign the angular velocity to the center of each MP according to those magnifications, the angular velocities of the MPs at locations 4.5, 3.5, 2.5,1.5 and 0.5 are approximately 2.7, 2.1, 1.5, 0.9, 0.3, respectively. On the other hand, we can consider each MP at positions 0.5, 1.5, 2.5, 3.5, and 4.5 in the same way. The angular velocities of the MPs at locations 0.5, 1.5, 2.5, 3.5 and 4.5 are approximately 0.3, 0.9, 1.5, 2.1 and 2.7 respectively.

We consider the above physical phenomenon from . Before two objects combine and begin to rotate, the velocity of one object is , and that of the other object is . The momentum, , of the former, which has the RM of and the velocity of , is . On the other hand, the momentum of the object with the velocity of 0 is zero. The center of KE of two objects is at location 0.5 in the direction perpendicular to the -axis since the center of the object having KE is at that location. After two objects combine and begin to rotate, the velocity of the center of the CO, which becomes the RM of due to the combination, is .

We examine the velocity of each MP of the CO when they become perpendicular to the

-axis due to the rotation. Since the center of rotation of the CO has the above velocity of 10 and the relative velocities of the MPs to it are the values as their angular velocities we have already calculated, the velocity of each MP is:

Then the KE of each MP is:

As a result, if let

be total KE, we get the following

:

We consider the center of KE of the MPs when they become perpendicular to the

-axis. As above mentioned, the centers of the MPs are located at distances of

, 3.5, 2.5, 1.5, 0.5,

0.5,

1.5,

2.5,

3.5, and

4.5 from the

-axis. If let

be distance from the

-axis multiplied by KE, the distribution of KE of each MP is given as the following

:

Furthermore, the sum of the

is:

Let LCKE be the location of the center of KE. We can derive the LCKE of the CO using the following formula:

Substituting Eq. (5) into the numerator in Eq. (6) and Eq. (3) into the denominator in Eq. (6), the LCKE of the MPs is given:

Therefore, the LCKE of the CO moves by:

As a result, since the rest energy of the CO does not change, its LCE also moves in the negative direction on the -axis no matter what the specific numbers are.

2.3. Movement of the LCRE

We demonstrate the LCRE before and after the combination of two objects based on the results of calculations of the CE according to Newtonian mechanics. We confirm the LCRE of the two objects before the combination between them. The formula for the RE is expressed by:

where

is speed of light. Then the

of the object stationary,

, by substituting 0 for

in Eq. 9, is expressed as follows:

By contrast, the

of the object having

,

, by substituting

for

in Eq. 9, is as follows:

Since

,

. Hence, since

, we get:

Since the distance in the direction perpendicular to the

-axis is not under Lorentz contraction, that from the center of each object to the

-axis is 0.5. Then the LCRE of them is:

where m

From inequality (12), the distribution of RE of the two objects is not symmetric to the

-axis, and the LCRE of them is within the range

Now we consider the LCRE of the CO when it becomes perpendicular to the -axis in . We compare the RE of each MP of the CO located symmetrically to the -axis. The value of numerator in Eq. (9), is equal with respect to every MP since each MP has the same RM and is the constant. Hence, the difference in RE between the MPs is determined by which is the value of denominator in Eq. (9).

Each MP of the CO in the range where , since the CO rotates counterclockwise in , has the velocity which is the sum of its negative rotational one and the positive translational one of . By contrast, Each MP of the CO in the range where has the velocity which is the sum of its positive rotational one and the positive translational one of since the CO rotates counterclockwise in .

The velocity of a MP is expressed as:

We can assume that the values of

,

and

are extremely small, in other words,

and

. Hence, since the values

and

are almost determined by each numerator, they are approximately equal to

and

respectively. This corresponds to the velocity of each MP obtained by the numerical calculation based on Newtonian mechanics above. Furthermore, since

, we obtain:

Moreover, substituting

and

into

in Eq. (9) respectively, we have

and

. From inequality (15), we get:

If let

and

be the RE of a MP having

and that of a MP having

, respectively, each RE is expressed:

As a result, from inequality (16), for

and

, we find the following inequality:

In addition, let

and

be the distance from the

-axis to a MP having

and that from the

-axis to one having

respectively, and then

. Moreover, for each MP, let

and

be each

multiplied by each distance from the

-axis. For each MP symmetric to the

-axis, from the expression (18) and

, the following inequality holds:

Since here has a negative sign, the LCRE of two MPs is in the range where .

Let

and

be the total of

of all MPs in the range where

and that of

of all MPs in the range where

, respectively.

is given by:

Likewise,

is expressed by:

Here it is assumed that each term in Eq. (20) and the corresponding one in Eq. (21) are symmetrical with respect to the

-axis. Therefore, from inequality (19),

of each term in Eq. (21) is always greater than that of the corresponding one in Eq. (20). We can find the following inequality:

Since has a negative sign, the LCRE of the CO exists in the range where . Furthermore, from Eqs. (7) and (8), excluding rest energy, we have already demonstrated that the LCKE of the CO moves from the initial that. On the other hand, the location of its center of rest energy does not change. As a result, the LCRE of the CO moves by the change of its LCKE, in other words, its location of the center of RE other than rest energy.

The above conclusion, of course, also holds when the CO is not perpendicular to the -axis. Suppose that, in , the rotating CO with extremely short width overlaps the -axis, and hence its LCRE is on it. When observing this from , we need to consider the relativity of simultaneity in SR. The time at each point in the rear in the CO’s traveling direction is advancing faster than those in the front in its traveling direction. Hence, the rotating CO does not overlap the -axis completely. A MP in the rear in its traveling direction is already in the range of even though that in the front in its traveling direction is on the -axis, in other words, at the point of . Here the former RE of including the rest energy shifts to the range of since its RM shifts to there. In the realm where Newtonian mechanics applies, we are usually unable to observe such physical phenomenon because the difference in the locations of each MP are extremely small.6