2. Movement of the LCRE in a MIFR

We presuppose two inertial frames of reference,

and

, that are in a state of uniform relative motion to each other.

moves with constant velocity

in the positive direction of the

axis in

. Moreover, assume that the two objects having the same rest mass (RM) and the same size, in

, move parallel to the

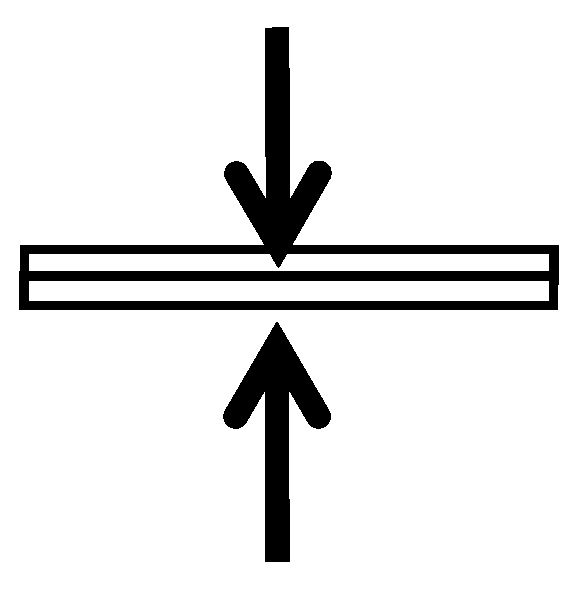

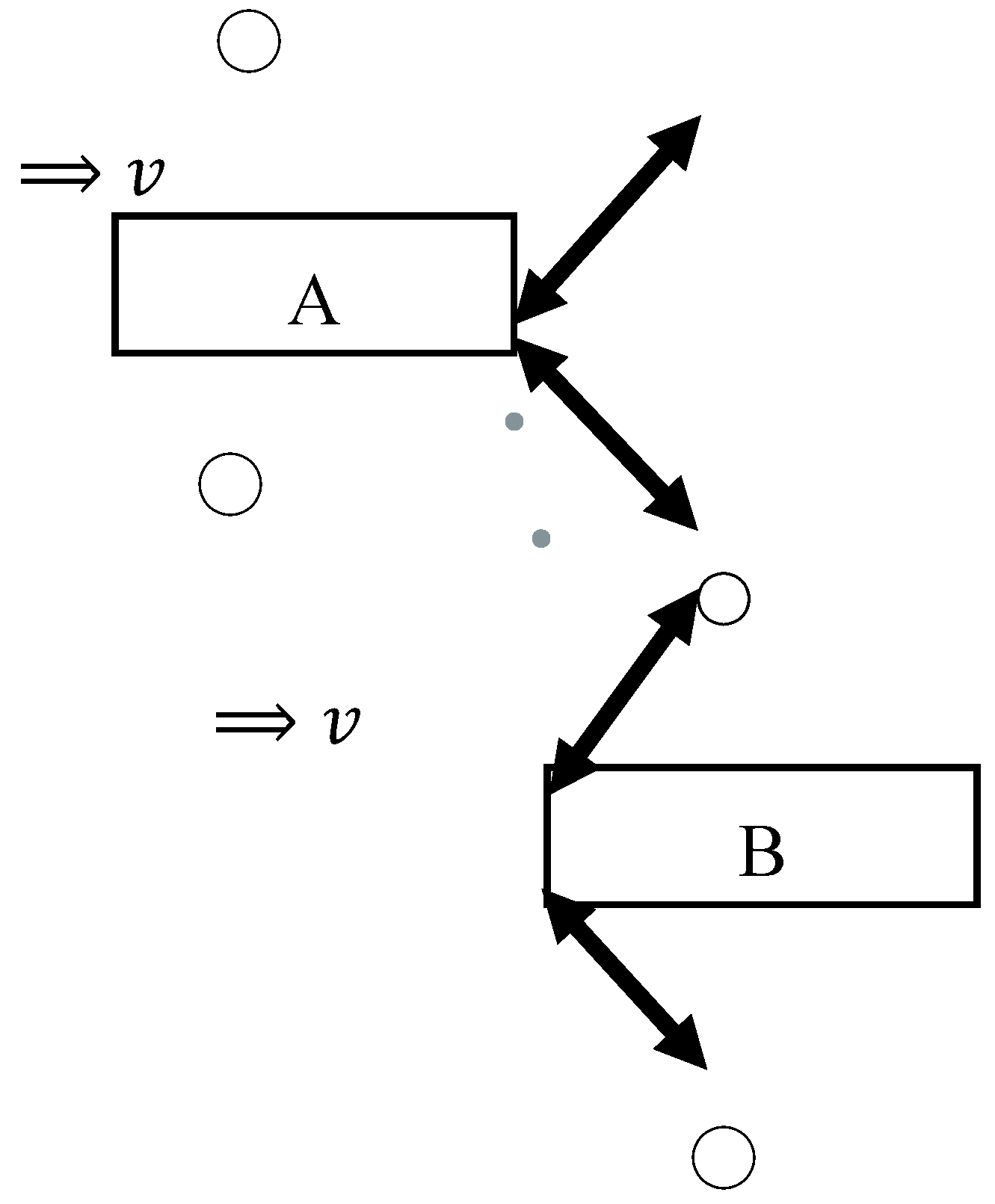

-axis from opposite directions and with the same speed as shown in

Figure 1. Those velocities are

and

, respectively. The two objects are symmetrical to the

-axis, and they are located very close to it. Each length in the direction of travel of the objects is much longer than that perpendicular to the direction of travel of them, and moreover the latter is negligibly extremely short. Here let

-axis be the axis perpendicular to the

-axis. In addition, assume that the origin of the

-axis is on the

-axis.

When the objects become perfectly symmetric with respect to the

-axis, as shown in

Figure 2, the forces perpendicular to the direction of travel of them are applied to the CRE of each object in the MIFR. The forces result in a perfectly inelastic collision between the objects and thereby they combine. Here, as shown in

Figure 2, the length in the direction of the

-axis of the CO is negligibly extremely short.

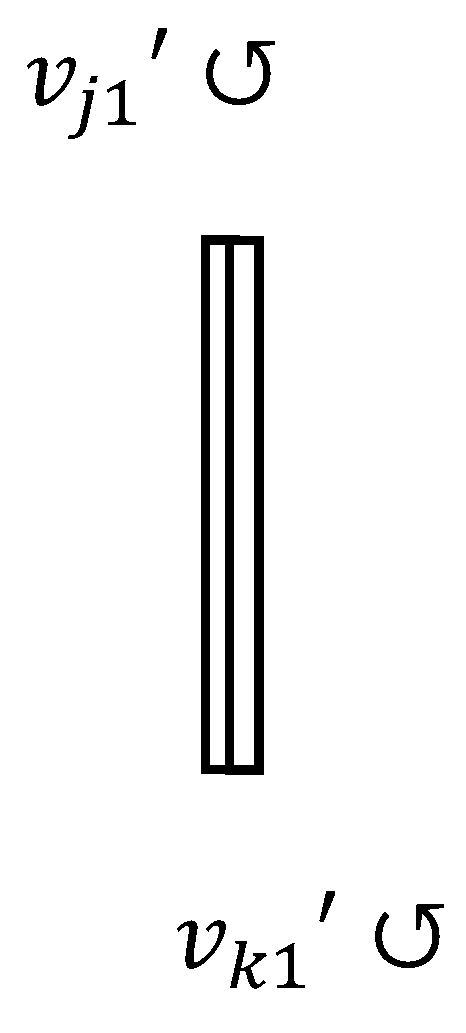

After the objects combine, the translational motion of each object stops, and a recoilless rotational motion of the CO occurs counterclockwise. The reason for this is that each momentum of the objects before the combination between them acts like the moment of force on the CO. Suppose that this rotational motion takes place around

. When the CO rotates and becomes perpendicular to the

-axis, it can be considered a rod with negligible width as shown in

Figure 3. The distribution of RM of the CO is symmetric with respect to the

-axis. Here let

be a velocity of a minute portion (MP) of the CO that lies in the range where

. Similarly, let

be a velocity of a MP of the CO that exists in the range where

. Suppose that a MP with

and one with

are symmetrical with respect to the

-axis. When observed from

,

and

of each MP symmetrical with respect to the

-axis are opposite in direction but equal in magnitude, i.e.,

. Hence, the energy of each MP is equal because the RM and magnitude of velocity of each are the same. In sum, in

, the LCRE of the CO is on the

-axis.

We will observe these phenomena from

. Here assume that, when observed from

,

. Then, as shown in

Figure 4, the object on the right is stationary, and that on the left moves at a speed

parallel to the

-axis.

Here relativistic velocity, , is expressed as based on the law of velocity addition in SR.

After a perfectly inelastic collision between the objects occurs, the CO starts rotating around

. When the CO rotates and becomes perpendicular to the

-axis, the length in the direction of the

-axis of the CO is negligibly extremely short as shown in

Figure 5. On the other hand, the center of RM of the CO moves at

in the positive direction of the

-axis in

since its center of RM is stationary in

. This is also shown in

Figure 5. Here let

be a velocity of a MP of the CO in the range where

. This corresponds to

in

. In addition, let

be a velocity of a MP of the CO in the range where

. This corresponds to

in

. Suppose that a MP with

and one with

are symmetrical with respect to the

-axis. When observed from

,

and

of each MP symmetrical with respect to the

-axis are opposite in direction and furthermore different in magnitude.

Based on the thought experiment described above, we consider the LCRE before and after the combination of two objects. First, we confirm the LCRE of the two objects before the combination between them. The formula for relativistic energy (RE) is expressed by the following formula:

where

,

and

denote energy, RM and velocity, for an object, and

is speed of light. Then the energy of the object stationary,

, by substituting 0 for

in Equation (1), is expressed as follows:

By contrast, the energy of the object having

,

, by substituting

for

in Equation (1), is as follows:

Since

,

. Hence, since

, we get the following inequality:

The center of RM of the two objects is on the -axis since the distribution of RM of them is symmetric to the -axis. By contrast, since from inequality (4), the distribution of RE of the two objects is not symmetric to the -axis, and the LCRE of them is located near the object having . Even so, the LCRE of the two objects is located at the vicinity of on the -axis because they are located very close to the -axis, and each length perpendicular to the -axis is almost negligible.

Second, we consider the LCRE of the two objects after the combination between them. For simplicity, we examine the energy distribution when the CO resulting from the perfectly inelastic collision begins to rotate counterclockwise and thereafter it become perpendicular to the -axis in . The distribution of RM of the CO, since the rotational motion of it takes place around , is symmetric to the origin of the -axis on the -axis, in other words, to the -axis.

The velocity of each MP of the CO in the range where , since the CO rotates counterclockwise in , is the sum of its negative rotational velocity and the positive translational one of . By contrast, the velocity of each MP of the CO in the range where is the sum of its positive rotational velocity and the positive translational one of since the CO rotates counterclockwise in .

We compare the RE of each MP of the CO located symmetrically to the -axis. The value of numerator in Equation 1, is equal with respect to every MP since the RM of each MP is the same and is the constant. Hence, the difference in RE of each MP is determined by which is the value of denominator in Equation (1).

Let

be the RE of a MP having

that lies in the range where

. Similarly, let

be the RE of a MP having

that exists in the range where

. First, we calculate the values of

and

based on the law of velocity addition in SR. Since the direction of

is opposite to the direction of translational movement of the CO and that of

is the same as that of translational movement of it, each value becomes as follows:

Here we can assume that the values of

,

and

are extremely small, in other words,

and

. Hence, since the values

and

are almost determined by each numerator. Then

and

is approximately equal to

and

, respectively. Furthermore, since

, we obtain the following inequality:

Second, substituting

in Equation (5) for

in Equation (1) and

in Equation (5) for

in Equation (1) gives

and

, respectively. Since from inequality (6), we get the following inequality:

Furthermore, since from inequality (7), for

and

, we find the following expression:

Let

be the total RE of all minute portions in the range where

. Similarly, let

be the total RE of all minute portions in the range where

.

is given by the following expression:

Likewise,

is expressed by the following expression:

Here it is assumed that each term in Equation (9) and the corresponding one in Equation (10) are symmetrical with respect to the

-axis. Since Equation (8) holds true for all minute portions symmetrical with respect to the

-axis, the RE of each term in Equation (10) is always greater than that of the corresponding one in Equation (9). As a result, we can find the following inequality:

Here the length of the CO when it becomes perpendicular to the -axis is assumed to be sufficiently long. Then, from inequality (11), the LCRE of the CO consisting of the two objects lies in the range where and which is far away from the vicinity of , in other words, that of the -axis. This means that, by change in the distribution of energy, the LCRE of two objects moves from the vicinity of . Therefore, we conclude that the LCRE in a MIFR can change.

The above conclusion, of course, also holds when the CO is not perpendicular to the

-axis. Suppose that, in

, the rotating CO with negligible width overlaps the

-axis, and hence its LCRE is on it. When observing this from

, we need to consider the relativity of simultaneity in SR. The time at each point in the rear in the CO’s traveling direction is advancing faster than those in the front in its traveling direction because the former is located behind the CO’s traveling direction compared to the latter. Hence, the rotating CO does not overlap the

-axis completely. A MP in the rear in its traveling direction is already in the range of

even though that in the front in its traveling direction is on the

-axis, in other words, on the point of

. Here the former RE of including the rest energy shifts to the range of

since its RM also shifts to there. In the realm where Newtonian mechanics applies, we are usually unable to observe such physical phenomenon because the difference in the locations of each MP are extremely small.[

6]

3. Uncertainty of the LCRE When a MO Comes to Rest

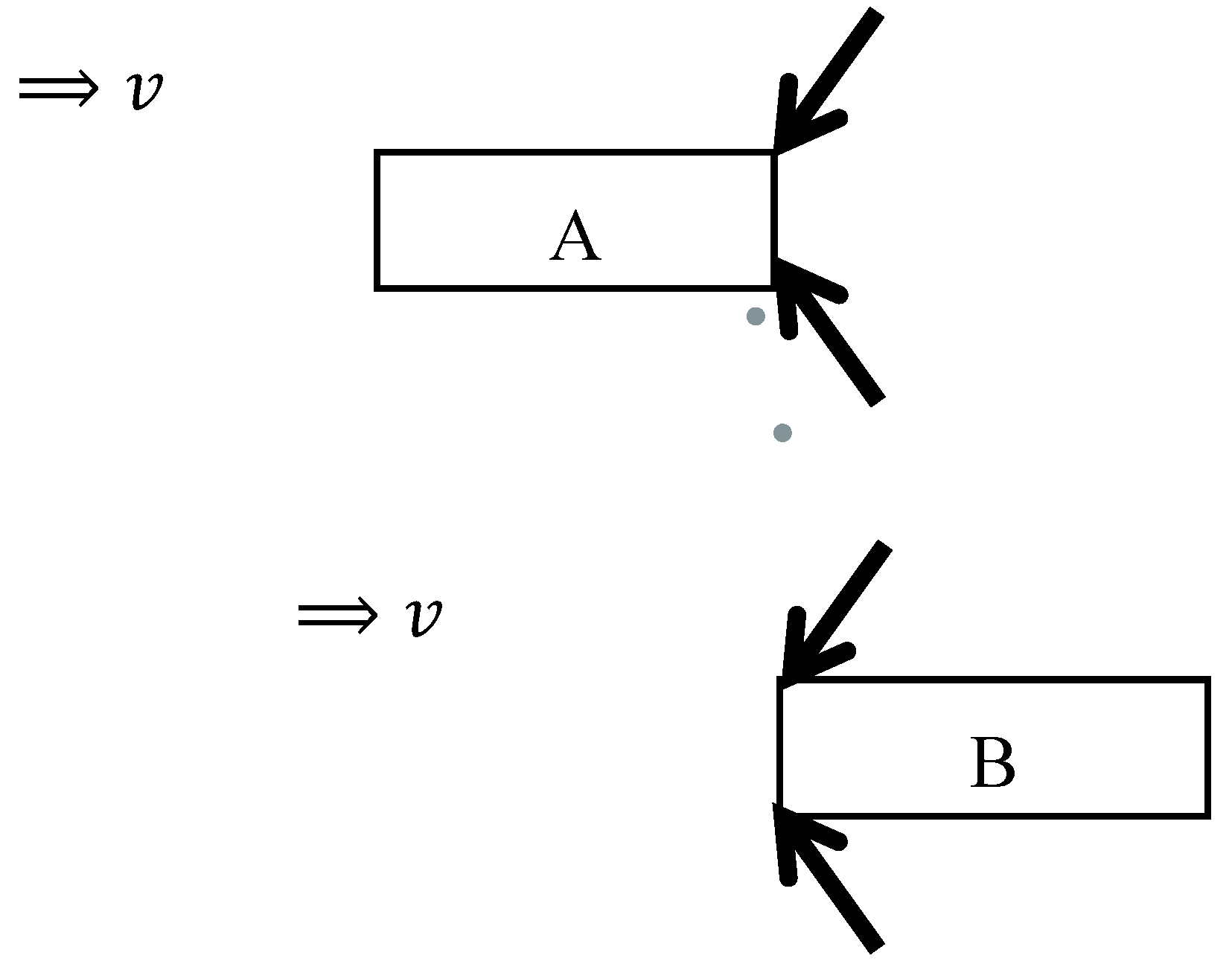

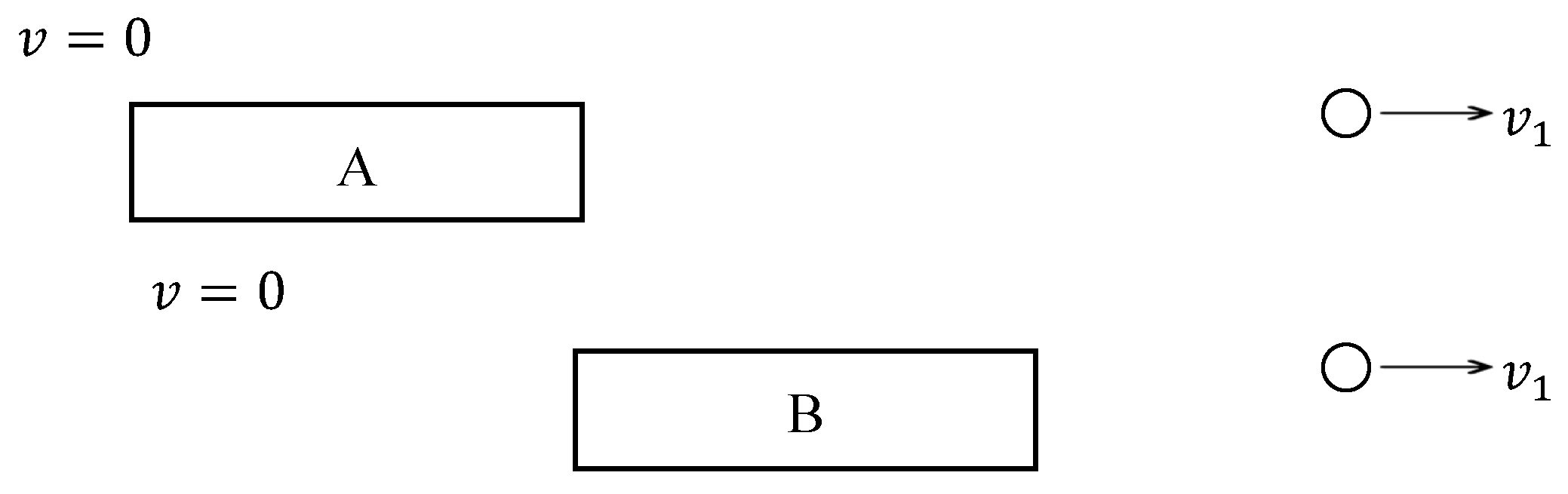

We presuppose that two objects A and B with the same RM and the same size are moving parallel to the positive direction of the -axis with the same velocity .

We simultaneously, to each MO, apply the forces of the same magnitude that act in the direction opposite to the traveling direction of them. Let the

-axis be the axis perpendicular to the

-axis. To A from the positions

and

, and to B from the positions

and

, the forces are applied simultaneously in the direction of the arrow in

Figure 6.

The forces on A are applied from the front in the traveling direction of it. By contrast, the forces on B are applied from the rear in the traveling direction of it. These are also shown in

Figure 6. Each force is simultaneously applied from the point on the same

coordinate and acts on each object at the same time. Here, for component of force, each component perpendicular to the traveling direction of A is cancelled out since the directions of the two components are opposite. The same is true for B. Hence, the resultant force applied to A from two positions is parallel to the

-axis. The same is true for the resultant force applied to B from two positions.

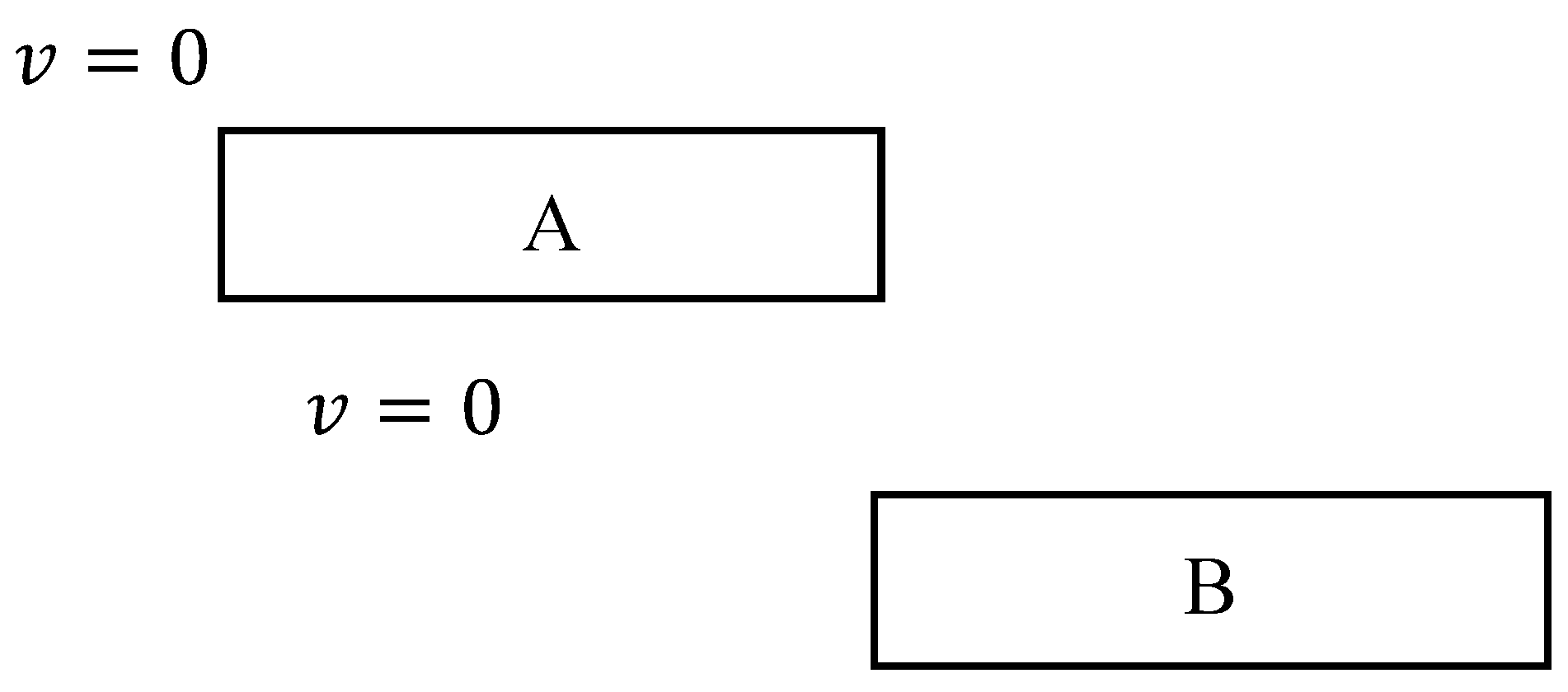

After the force applied to A is transmitted to the rear of it, the velocity of it decreases and finally it comes to rest. By contrast, the force applied to B is transmitted to the front of it, and then the velocity of it decreases and finally it comes to rest. The time at each point in A is advancing faster than that at each point in B because the former is located behind the traveling direction compared to the latter. This is due to the relativity of simultaneity in SR. Therefore, the forces on A are transmitted throughout the object faster than those on B even if, when observed from the frame of reference where A and B are stationary, each force is simultaneously transmitted throughout each object. This means that the TTF inside each MO differs. As a result, as shown in

Figure 7, A comes to rest faster than B. In other words, B continues to move after A comes to rest, so it moves forward in the positive direction of the

-axis and then comes to rest. The effect of LC disappears when the MO comes to rest due to negative acceleration motion. The length of an object at rest becomes longer than one when it is in motion, and its length becomes proper length.

We try to quantify the above process. Let , , and so on be the points spaced in order at equal intervals on the -axis. Suppose that the rear end of A advances from to and comes to rest, and its tip advances from to and comes to rest. In other words, A at the position between and is located between and after coming to rest. On the other hand, the rear end of B advances from to and comes to rest, and its tip advances from to and comes to rest. In other words, B at the position between and is located between and after coming to rest.

We examine the movement of the CRE of A (

) and that of the CRE of B (

). Each CRE equals to the center of rest energy if each object comes to rest. The

moves from

to

on the

-axis until A completely comes to rest. Therefore, the movement distance of the

is as follows:

On the other hand, the

moves from

to

on the

-axis until B completely comes to rest. Therefore, the movement distance of the

is as follows:

We find that the difference in

and

on the

-axis is as follows:

As a result, the moves further in the positive direction of the -axis compared with the even though, to the objects with the same RM and the same size, we simultaneously apply the forces of the same magnitude and direction.

Here, using the case in

Figure 6, we assume that two particles at the ends of the double arrow lines, which have the same RM, begin to move due to the reaction of the forces applied to A as shown in

Figure 8. The sum of momentums of their particles is equal in magnitude and opposite in the direction compared to the momentum of A. This is also true if two particles at the ends of the double arrow lines start moving due to the reaction of the forces applied to B. Here let

be the particle system that interacts with A. Similarly, let

be the particle system having the interaction with B. Then, since A and B move in the negative direction of the

-axis, each CRE in

and

moves in the positive direction of it. In addition, each CRE of

and

always exists at

and

since they move parallel to the

-axis like A and B. Each CRE of

and

is originally at the point with the same

-coordinate. Each reaction of the forces applied to A and B occurs at the same time and at the above point. Hence, the

-coordinate of each CRE of

and

at the same time is always the same.

Figure 9 shows that each CRE of

and

represented by a circle is moving at the same velocity, and the

-coordinate of each CRE at the same time is the same.

We already demonstrate that and are not equal even though the movement distance of CRE of having the interaction with and that of CRE of having the interaction with are the same. The LCRE, as shown in Figs. 8 and 9, differs depending on where the forces are applied to the MO, such as when the forces are applied to the front end of the MO, or when the forces are applied to the rear end of it. The thought experiment here can be regarded as that in an IFR. Hence, we find that the LCRE in an IFR is not necessarily uniquely determined.