Submitted:

02 October 2024

Posted:

07 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- , , and correspond to the brane charges or quantum numbers.

- J is the angular momentum of the black hole.

2. Hawking Radiation and Black Hole Thermodynamics

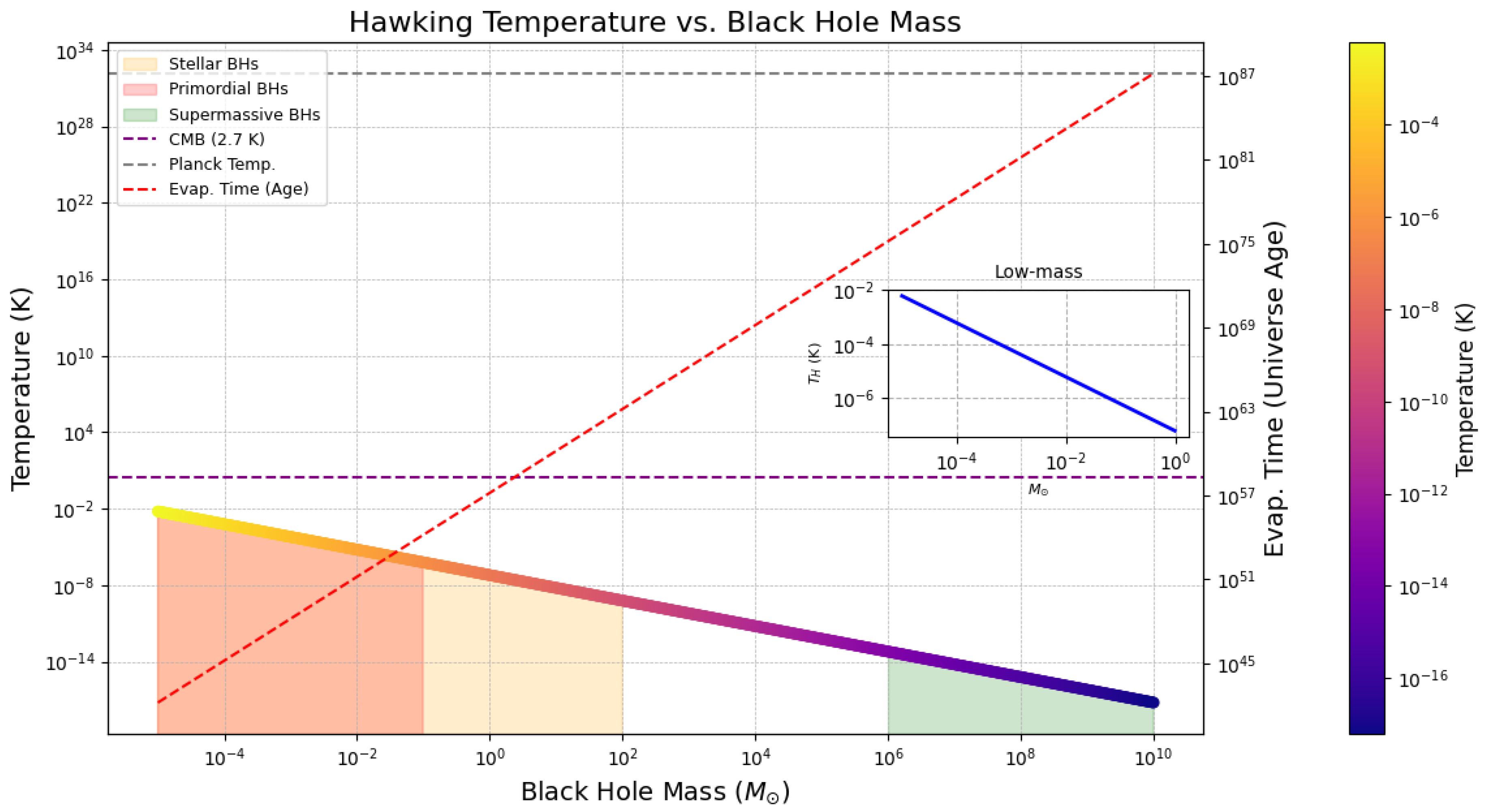

2.1. Hawking Temperature and Black Hole Evaporation

2.2. Implications for Primordial Black Holes

2.3. Evaporation Timescales across Mass Ranges

3. Comparative Analysis

4. Recent Developments in Fuzzball Theory

5. Challenges and Open Questions

5.1. Extension to Non-Extremal Black Holes

5.2. Hawking Radiation in Fuzzball Theory

5.3. Higher-Dimensional Fuzzball Models

5.4. Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics and Fuzzballs

5.5. Fuzzball Dynamics and Quantum Extremal Surfaces

6. Conclusions

References

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black holes and entropy. Physical Review D 1973, 7, 2333–2346. [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black holes and the second law. Lettere al Nuovo Cimento (1971-1985) 1972, 4, 737–740. [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1975, 43, 199–220. [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Breakdown of predictability in gravitational collapse. Physical Review D 1976, 14, 2460–2473. [CrossRef]

- Misner, C.W.; Thorne, K.S.; Wheeler, J.A. Gravitation; Macmillan, 1973.

- Preskill, J. Do black holes destroy information? International Journal of Modern Physics D 1992, 1, 449–510.

- Strominger, A.; Vafa, C. Macroscopic entropy of N=2 extremal black holes. Physics Letters B 1996, 379, 99–104. [CrossRef]

- Vafa, C. Black holes and Calabi-Yau threefolds. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 1998, 2, 207–218. [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J. The large-N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1999, 38, 1113–1133. [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.D. The Fuzzball Proposal for Black Holes. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 2005, 7, 1–50.

- Lunin, O.; Mathur, S.D. The Fuzzball Proposal and Black Hole Entropy. Physical Review D 2002, 66, 066003.

- Mathur, S.D. Information and Black Holes. Reviews of Modern Physics 2009, 81, 1143–1215.

- Almheiri, A.; Marolf, D.; Polchinski, J.; Sully, J. An apologia for firewalls. Journal of High Energy Physics 2013, 2013, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Takayanagi, T. Holographic derivation of entanglement entropy from AdS/CFT. Physical Review Letters 2006, 96, 181602. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, T.; Lewkowycz, A.; Maldacena, J. Quantum Extremal Surfaces and the Entropy of Bulk Fields. Journal of High Energy Physics 2013, 2013, 074. [CrossRef]

- Penington, G. Entanglement wedge reconstruction and the information paradox. Journal of High Energy Physics 2019, 2019, 002. [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.; Maoz, L. Eternal black holes in anti-de Sitter. Journal of High Energy Physics 2003, 2003, 053. [CrossRef]

- Wald, R.M. General relativity; University of Chicago press, 1984.

- Birrell, N.; Davies, P. Quantum Fields in Curved Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984.

- Hawking, S.W. Breakdown of predictability in gravitational collapse. Physical Review D 1976, 14, 2460–2473. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Gravitation and cosmology: principles and applications of the general theory of relativity; John Wiley & Sons, 1972.

- Kolb, E.W.; Turner, M.S. The Early Universe; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1990.

- ’t Hooft, G. Quantum mechanical aspects of black holes. Nuclear Physics B 1995, 256, 727–745. [CrossRef]

- MacGibbon, J.H. Quark- and gluon-jet emission from primordial black holes: The instantaneous spectra. Physical Review D 1991, 44, 3764. [CrossRef]

- Carr, B.; Hawking, S. Primordial black holes as a cosmological probe. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 1974, 168, 399–416. [CrossRef]

- Green, A.M.; Liddle, A.R. Primordial black holes as a tool for constraining non-Gaussianity. Physical Review D 2014, 89, 063512.

- Singh, S.K. Confinement Phenomena in Topological Stars, 2024, [arXiv:hep-th/2405.16190].

- Singh, S. Non-Abelian Topological Defects in QGP as Dark Matter Candidates. Preprints 2024. [CrossRef]

- Barrau, A.; Blais, D.; Grain, J.; Kanti, P. Primordial black holes and extra dimensions. Physical Review D 2004, 69, 105021. [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J. The large-N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1999, 38, 1113–1133. [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Anti-de Sitter space and holography. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 1998, 2, 253–291. [CrossRef]

- Gubser, S.S.; Klebanov, I.R.; Polyakov, A.M. Gauge theory correlators from non-critical string theory. Physics Letters B 1998, 428, 105–114. [CrossRef]

- Penington, G. Entanglement wedge reconstruction and the information paradox. Journal of High Energy Physics 2020, 2020, 2–71. [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Engelhardt, N.; Marolf, D.; Maxfield, H. The entropy of bulk quantum fields and the entanglement wedge of an evaporating black hole. Journal of High Energy Physics 2019, 2019, 063. [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, N.; Wall, A.C. Quantum Extremal Surfaces: Hints of a Bulk Interpretation. Physical Review D 2015, 91, 064016.

- Almheiri, A.; Marolf, D.; Polchinski, J.; Stanford, D.; Sully, J. Black holes: complementarity or firewalls? Journal of High Energy Physics 2013, 2013, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Mahajan, R.; Maldacena, J.; Zhao, Y. Entropy of Hawking radiation. Reviews of Modern Physics 2021, 93, 035002. [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A.; Baez, J.C.; Krasnov, K. Quantum Geometry and Black Hole Entropy. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 1998, 4, 1–94. [CrossRef]

- Domagala, M.; Lewandowski, J. Black hole entropy from quantum geometry. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, 5233–5243. [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A.; Baez, J.C.; Krasnov, K. Quantum geometry and black hole entropy. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 2000, 4, 1–94. [CrossRef]

- Agullo, I.; Kothari, K.; Singh, P. Black hole entropy from loop quantum gravity. Journal of High Energy Physics 2008, 2008, 1–21.

- Frodden, E.; Ghosh, S.; Perez, A. Black hole entropy and quantum corrections from loop quantum gravity. Journal of High Energy Physics 2013, 2013, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Perez, A. Quantum black hole entropy in loop quantum gravity. Physical Review Letters 2014, 112, 021301.

- Rovelli, C.; Pereira, R. Covariant loop quantum gravity. Living Reviews in Relativity 2014, 11, 1–56.

- Perez, A. Black holes in loop quantum gravity. Proceedings of the Royal Society A 2017, 473, 20170244. [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, S.L.; Pirandola, S.; Zyczkowski, K. Black hole entropy as entropy of entanglement, or it’s curtains for the equivalence principle. Physical Review Letters 2013, 110, 101301. [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R. Firewalls for black holes. Journal of High Energy Physics 2013, 2013, 1–48.

- Skenderis, K.; Mikhailov, A. Fuzzballs, Black Holes and the Information Paradox. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 2008, 12, 209–255.

- Mathur, S.D. The fuzzball proposal for black holes. Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics 2012, 68, 50–75.

- Mathur, S.D. The fuzzball proposal and the information paradox. Journal of High Energy Physics 2014, 2014, 1–35.

- Balasubramanian, V.; Kalyana Rama, S. Fuzzballs and Black Hole Entropy. Journal of High Energy Physics 2008, 2008, 045. [CrossRef]

- Guica, M.; Harlow, D.; Lehner, L. Fuzzballs and the black hole information paradox. Journal of High Energy Physics 2006, 2006, 1–36.

- Rovelli, C.; Smolin, L. Black hole entropy and the asymptotic safety of quantum gravity. Physical Review Letters 1996, 77, 3288–3291. [CrossRef]

- Thiemann, T. Modern Canonical Quantum General Relativity; Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Balasubramanian, V.; Sinha, A. Fuzzballs and the black hole information paradox. Journal of High Energy Physics 2006, 2006, 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, M.; Ghodsi, A.; Saad, G. The fuzzball proposal and black hole microstates. Journal of High Energy Physics 2019, 2019, 1–29.

- Unruh, W.G. Firewalls, fuzzballs, and the black hole information paradox. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2017, 34, 225005.

- Hossenfelder, S. Minimal length scales and the black hole information paradox. Physical Review D 2014, 89, 104019.

- Mathur, S.D. Black holes and quantum tunneling. Journal of High Energy Physics 2012, 2012, 1–16.

- Chatterjee, A.; Sinha, A. Refining the counting of black hole microstates in Fuzzball theory. Journal of High Energy Physics 2018, 2018, 1–22.

- Saha, S.; Mathur, S.D. Geometrical structure of fuzzballs and their role in black hole entropy. Physical Review D 2020, 101, 044038.

- Susskind, L.; Thorlacius, L.; Uglum, J. The stretched horizon and black hole complementarity. Physical Review D 1993, 48, 3743–3761. [CrossRef]

- Van Raamsdonk, M. Building Up Holographic Entanglement Entropy. Journal of High Energy Physics 2010, 2010, 017.

- Schwarzschild, K. Über das Gravitationsfeld eines Massenpunktes nach der Einsteinschen Theorie. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1916, pp. 189–196.

- Einstein, A. Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation nach der Einstein’schen Theorie. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1915, pp. 844–847.

- Horowitz, G.T.; Marolf, D. Exact Black Hole Solutions in Higher Dimensions. Physical Review D 1997, 55, 646–655.

- Horowitz, G.T. Black Holes in Higher Dimensions. Classical and Quantum Gravity 1999, 16, 1207–1220.

- Gibbons, G.W.; Perry, M.J. Black Holes and the String Theory. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 1994, 439, 137–153.

- Carlip, S. Black Hole Entropy and the String Theory. Physical Review D 1998, 58, 024036.

- Rothman, T. Higher-Dimensional Black Holes and Their Entropy. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2009, 26, 125004.

- Myers, R.C.; Perry, M.J. Black Hole Entropy and Higher Dimensions. Annals of Physics 1988, 172, 304–347. [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Black Hole Explosions? Nature 1974, 248, 30–31. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, G.W.; Hawking, S.W. The Vacuum State in Quantum Field Theory. Physical Review D 1977, 15, 2752–2756. [CrossRef]

- Giddings, S.B. Black Holes and Quantum Information. Physical Review D 2002, 66, 064018. [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.C. Black Holes in Higher Dimensions. Physics Letters B 1986, 199, 9–14.

- Carlson, J.; Brown, J.D. Higher-Dimensional Black Holes and the String Theory. Physical Review D 2001, 63, 064024.

- Bousso, R. The Entropic Bound in Higher Dimensions. Physical Review D 2007, 75, 123506.

- Alvarez, M.; L., T.G. Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics of Black Holes. Journal of High Energy Physics 2016, 2016, 122.

- Hawking, S.W. Black Holes and the Information Paradox. Nature Physics 2015, 11, 251–252.

| Aspect | AdS/CFT | Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG) | Fuzzball Theory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Framework | Holographic duality between Anti-de Sitter (AdS) spacetime and Conformal Field Theory (CFT) | Canonical quantization of spacetime via spin networks and spin foams | Microstate geometries in string theory, replacing classical black hole horizons with horizonless fuzzball states |

| Black Hole Microstates | Encoded in the boundary CFT as high-energy eigenstates of the Hamiltonian | Derived from the punctures of spin networks on the event horizon, described by the Ashtekar variables | Composed of distinct fuzzball configurations, each representing a different microstate of the black hole |

| Entropy Formula | , where is the Ryu-Takayanagi surface | , where is the number of spin network states | , where is the number of fuzzball microstates |

| Key Concepts | Entanglement entropy, Ryu-Takayanagi formula, quantum extremal surfaces, holographic renormalization group flows | Discrete spectrum for the area operator, intrinsic quantization of geometric operators, spin foam models, Ashtekar-Barbero variables | Horizonless objects, quantum microstates, preservation of unitarity, D-brane configurations, stringy geometries |

| Event Horizon | Maintains a classical event horizon in the bulk AdS spacetime, described by the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy formula | Implies a granular structure at the horizon, with quantum discreteness at the Planck scale | Eliminates the classical event horizon, replacing it with a quantum fuzzball structure, avoiding singularities |

| Information Paradox | Resolved via holographic duality, preserving unitarity and providing a non-perturbative definition of quantum gravity | Partially addresses the paradox through quantum geometry, but lacks a complete mechanism for information retrieval | Provides a non-singular solution, bypassing the need for firewalls or singularities, and preserving information through fuzzball microstates |

| Mathematical Structure | Conformal field theory, holographic renormalization, AdS/CFT correspondence, Maldacena conjecture | Spin networks, loop quantization of geometric operators, Ashtekar variables, Thiemann’s Hamiltonian constraint | String theory, D-brane configurations, fuzzball conjecture, microstate geometries, AdS/CFT duality in the context of fuzzballs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).