Submitted:

03 October 2024

Posted:

03 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

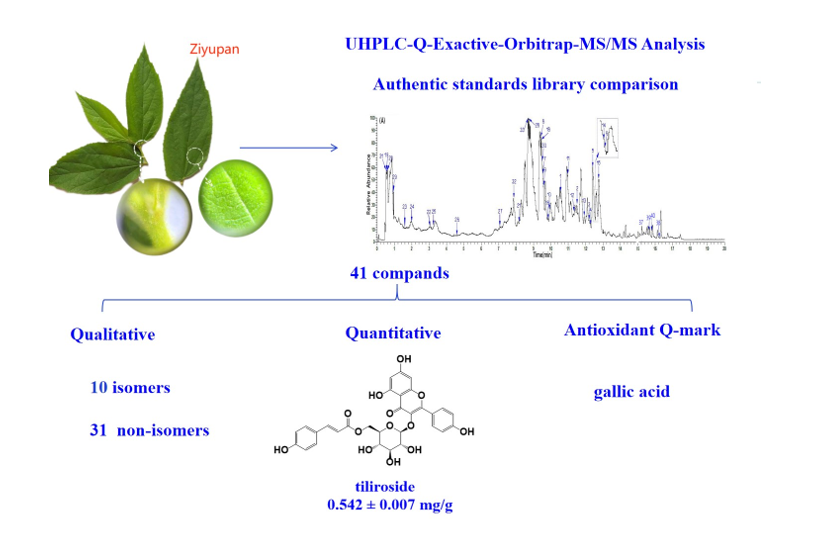

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

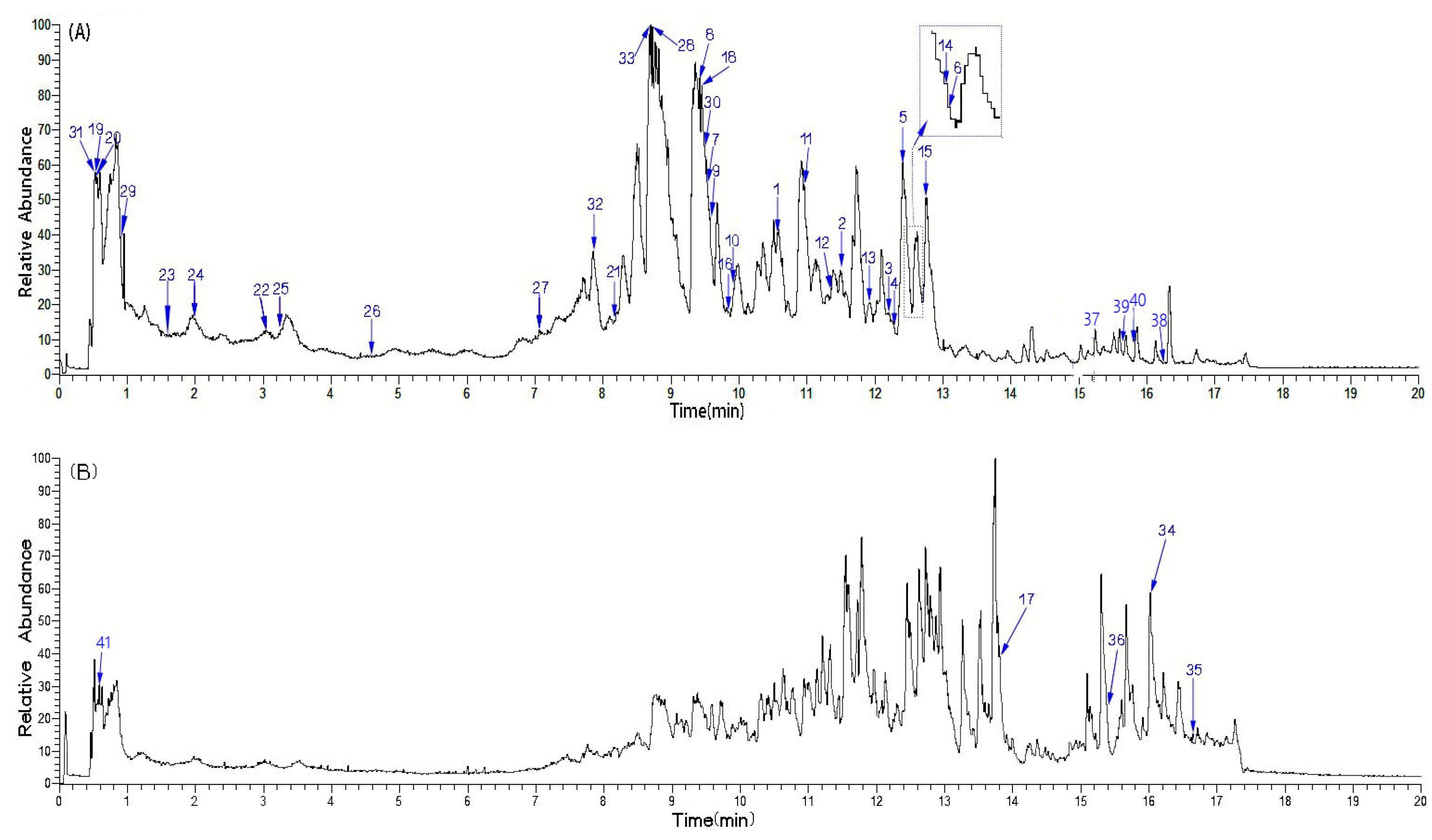

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

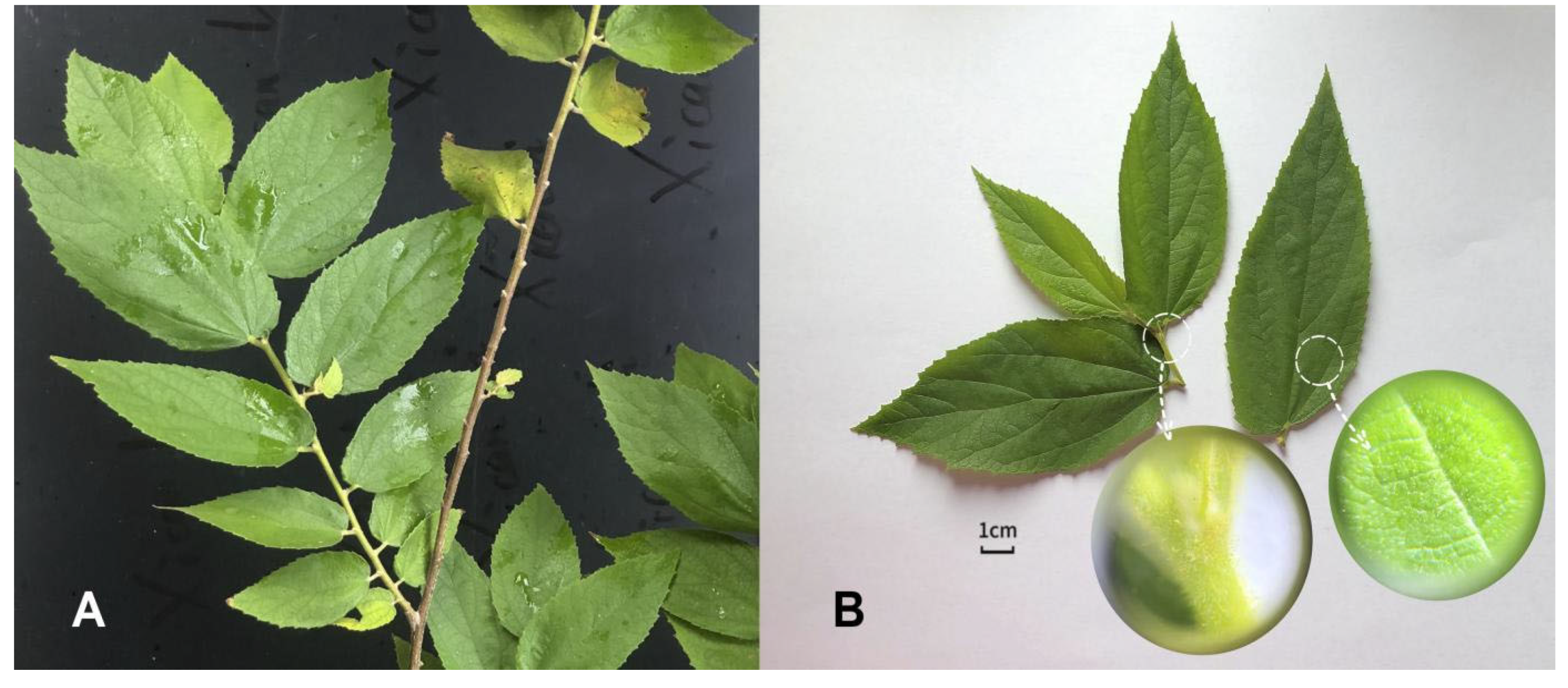

3.1. Plant Materials and Chemicals

3.2. Authentic Standards

3.3. Preparation of Sample and Authentic Standard Solutions

3.3.1. Preparation of Lyophilized Aqueous Extract and Sample Solutions

3.3.2. Preparation of Authentic Standard Solutions

3.4. Simultaneous Qualitative and Quantitative Analyses Using Database-Affinity UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap-MS/MS

3.5. Relative Antioxidant Level Evaluation Experiment

3.6. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Z.; Liu, X.R.; Liu, Y.L.; Xu, Q.M.; Yang, S.L. ChemInform Abstract: Two New Flavones from Uvaria macrophylla Roxb. var. microcarpa and Their Cytotoxic Activities. ChemInform. 2012, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Xu, Q.; Yangy, S. Chemical constituents from leaves of Uvaria microcarpa (in Chinese). Zhong Cao Yao. 2011, 42, 2197. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z.; huang, L.; Chen, R.; Yu, D. Chemical constituents of Uvaria Kurzii (in Chinese). Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2009, 34, 2203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.N. Study on the chemical constituents of Uvaria microcarpa Champ. ex Benth (in Chinese). Second Military Medical University Master Dissertation. 2009, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.-N.; Chen, H.-S.; Jin, Y.-S.; Liu, H.; Yang, X.-W. Chemical Constituents from the Stems of Uvaria microcarpa. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines. 2009, 7, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, P.-C.; Chen, R.-Y.; Dai, S.-J.; Yu, S.-S.; Yu, D.-Q. Four new compounds from the roots of Uvaria macrophylla. Journal of Asian Natural Products Research. 2006, 7, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, R.-Y.; Yu, S.-S.; Yu, D.-Q. Uvamalols D-G: Novel polyoxygenated seco-cyclohexenes from the roots ofUvaria macrophylla. Journal of Asian Natural Products Research. 2003, 5, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, P. A Novel Dihydroflavone from the Roots of Uvaria Macrophylla. Chin Chem Lett. 2002, 13, 857–858. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, D. Summary of studies of ZIyupan (in Chinese). Guangxi TCM. 2006, 29, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Li, X.; Zeng, J.; Cai, R.; Li, C.; Chen, C.B. Library-based UHPLC-Q-Exactive-Orbitrap-MS Putative Identification of Isomeric and Non-isomeric Bioactives from Zibushengfa Tablet and Pharmacopoeia Quality-marker Chemistry. J Liq Chromatogr Relat Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, X.; Cai, R.; Chen, B.; Zeng, J.; Li, C.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y. UHPLC-Quadrupole-Exactive-Orbitrap-MS/MS-based Putative Identification for Eucommiae Folium (Duzhongye) and its Quality-marker Candidate for Pharmacopeia. J Sep Sci. 2023, 46, 00. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Li, X.; Cai, R.; Li, C.; Chen, S. Jinhua Qinggan Granule UHPLC-Q-extractive-Orbitrap-MS assay: Putative identification of 45 potential anti-Covid-19 constituents, confidential addition, and pharmacopoeia quality-markers recommendation. J Food Drug Anal. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xican Li; Jingyuan Zeng; Chunhou Li; Hanxiao Chai; Shaoman Chen; Nana Jin; Tingshan Chen; Xiaohua Lin; Sunbal Khan; Cai, R. Simultaneous Qualitative and Quantitative Determination of 33 Compounds from Rubus Alceifolius Poir Leaves Using UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap-MS Analysis. Curr Anal Chem. 2024; 20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.C.; Zeng, J.; Cai, R.; Li, C. New UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap MS/MS-based Library-comparison Method Simultaneously Distinguishes 22 Phytophenol Isomers from Desmodium styracifolium. Microchem J. 2023, 190, 108938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.C.; Chen, S.M.; Zeng, J.Y.; Cai, R.X.; Liang, Y.L.; Chen, C.B.; Chen, B.; Li, C.H. Database-aided UHPLC-Q-orbitrap MS/MS Strategy Putatively Identifies 52 Compounds from Wushicha Granule to Propose Anti-counterfeiting Quality-markers for Pharmacopoeia. Chin Med. 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Mehta, K.; Sehgal, A.; Singh, S.; Sharma, N.; Ahmadi, A.; Arora, S.; Bungau, S.J.C.R.i.F.S. Exploring the role of polyphenols in rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition 2022, 62, 5372–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, X.; He, X.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, Z.; Wu, C.J.N. Gastroprotective Effect of Isoferulic Acid Derived from Foxtail Millet Bran against Ethanol-Induced Gastric Mucosal Injury by Enhancing GALNT2 Enzyme Activity. 2024, 16, 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Feng, G.; Zhao, N.; Wu, L.; Zhu, H.J.M.M.R. Isoferulic acid inhibits human leukemia cell growth through induction of G2/M-phase arrest and inhibition of Akt/mTOR signaling. 2020, 21, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Y.; Ha, J.Y.; Kim, K.M.; Jung, Y.S.; Jung, J.C.; Oh, S. Anti-Inflammatory activities of licorice extract and its active constituents, glycyrrhizic acid, liquiritin and liquiritigenin, in BV2 cells and mice liver. Molecules 2015, 20, 13041–13054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee CH, Tsai HY, Chen CL, et al. Isoliquiritigenin Inhibits Gastric Cancer Stemness, Modulates Tumor Microenvironment, and Suppresses Tumor Growth through Glucose-Regulated Protein 78 Downregulation. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolia A, Kumar H, Ramamurthy S, et al. Effect of Propolis Nanoparticles against Enterococcus faecalis Biofilm in the Root Canal. Molecules 2021, 26, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Ye, J.; Gao, L.; Liu, Y. The main bioactive constituents of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. for alleviation of inflammatory cytokines: A comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021, 133, 110917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.Y.; Im, E.; Kim, N.D. Therapeutic Potential of Bioactive Components from Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colorectal Cancer: A Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin M, Guo S, Zhang W, et al. Chemical Constituents of Supercritical Extracts from Alpinia officinarum and the Feeding Deterrent Activity against Tribolium castaneum. Molecules 2017, 22, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owczarek-Januszkiewicz, A.; Magiera, A.; Olszewska, M.A. Enzymatically Modified Isoquercitrin: Production, Metabolism, Bioavailability, Toxicity, Pharmacology, and Related Molecular Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 14784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shingnaisui, K.; Dey, T.; Manna, P.; Kalita, J. Therapeutic potentials of Houttuynia cordata Thunb. against inflammation and oxidative stress: A review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 220, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.M.N.; Dighe, S.N.; Katavic, P.L.; Collet, T.A. Antibacterial Potential of Extracts and Phytoconstituents Isolated from Syncarpia hillii Leaves In Vitro. Plants (Basel) 2022, 11, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yuan, C.; Ramaswamy, H.S.; Ren, Y.; Ren, X. Antioxidant capacity and hepatoprotective activity of myristic acid acylated derivative of phloridzin. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed SS, Rahman MO, Alqahtani AS, et al. Anticancer potential of phytochemicals from Oroxylum indicum targeting Lactate Dehydrogenase A through bioinformatic approach. Toxicol Rep. 2022, 10, 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Morgan, M.R.; Day, A.J. Transport of trans-tiliroside (kaempferol-3-β-D-(6"-p-coumaroyl-glucopyranoside) and related flavonoids across Caco-2 cells, as a model of absorption and metabolism in the small intestine. Xenobiotica 2015, 45, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabeek, W.M.; Marra, M.V. Dietary Quercetin and Kaempferol: Bioavailability and Potential Cardiovascular-Related Bioactivity in Humans. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M.S.M.; Abdella, A.; Khidr, Y.A.; Hassan, G.O.O.; Al-Saman, M.A.; Elsanhoty, R.M. Pharmacological Activities and Characterization of Phenolic and Flavonoid Constituents in Methanolic Extract of Euphorbia cuneata Vahl Aerial Parts. Molecules 2021, 26, 7345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Seedi HR, Yosri N, Khalifa SAM, et al. Exploring natural products-based cancer therapeutics derived from egyptian flora. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 269, 113626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin Y, Yang P, Wang L, et al. Galangin as a direct inhibitor of vWbp protects mice from Staphylococcus aureus-induced pneumonia. J Cell Mol Med. 2022, 26, 828–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ditano-Vázquez P, Torres-Peña JD, Galeano-Valle F, et al. The Fluid Aspect of the Mediterranean Diet in the Prevention and Management of Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes: The Role of Polyphenol Content in Moderate Consumption of Wine and Olive Oil. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Totoki, T.; Takada, S.; Otsuka, S.; Maruyama, I. Potential roles of 1,5-anhydro-D-fructose in modulating gut microbiome in mice. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 19648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma LJ, Hou XD, Qin XY, et al. Discovery of human pancreatic lipase inhibitors from root of Rhodiola crenulata via integrating bioactivity-guided fractionation, chemical profiling and biochemical assay. J Pharm Anal. 2022, 12, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajnef I,Khemiri S,Yahmed B N, et al. Straightforward extraction of date palm syrup from Phoenix dactylifera L. byproducts: application as sucrose substitute in sponge cake formulation. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2021, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Santana-Gálvez, J.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A. Chlorogenic Acid: Recent Advances on Its Dual Role as a Food Additive and a Nutraceutical against Metabolic Syndrome. Molecules 2017, 22, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Esawi, M.A.; Elansary, H.O.; El-Shanhorey, N.A.; Abdel-Hamid, A.M.E.; Ali, H.M.; Elshikh, M.S. Salicylic Acid-Regulated Antioxidant Mechanisms and Gene Expression Enhance Rosemary Performance under Saline Conditions. Front Physiol. 2017, 8, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi HW, Tian M, Song F, et al. Aspirin's Active Metabolite Salicylic Acid Targets High Mobility Group Box 1 to Modulate Inflammatory Responses. Mol Med. 2015, 21, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, C.; Jung, U.; Jo, S.K. Screening of anti-obesity agent from herbal mixtures. Molecules 2012, 17, 3630–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebaka, V.R.; Wee, Y.J.; Ye, W.; Korivi, M. Nutritional Constituent and Bioactive Constituents in Three Different Parts of Mango Fruit. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Mateos A, Feliciano RP, Boeres A, et al. Cranberry (poly)phenol metabolites correlate with improvements in vascular function: A double-blind, randomized, controlled, dose-response, crossover study. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016, 60, 2130–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Wu D, Liu J, et al. Characterization of xanthine oxidase inhibitory activities of phenols from pickled radish with molecular simulation. Food Chem X 2022, 14, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, S.H.; Nile, A.S.; Keum, Y.S.; Sharma, K. Utilization of quercetin and quercetin glycosides from onion (Allium cepa L.) solid waste as an antioxidant, urease and xanthine oxidase inhibitors. Food Chem. 2017, 235, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo FF, de Paulo Farias D, Neri-Numa IA, Pastore GM. Polyphenols and their applications: An approach in food chemistry and innovation potential. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 127535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen CC, Shyur LF, Jan JT, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine herbal extracts of Cibotium barometz, Gentiana scabra, Dioscorea batatas, Cassia tora, and Taxillus chinensis inhibit SARS-CoV replication. J Tradit Complement Med. 2011, 1, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Z,Niu L,Chen Y, et al. Recent advance in the biological activity of chlorogenic acid and its application in food industry. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2023, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos B A P,Ferro M A,Oliveira M M, et al. Biosynthesis and bioactivity of Cynara cardunculus L. guaianolides and hydroxycinnamic acids: a genomic, biochemical and health-promoting perspective. Phytochemistry Reviews 2019, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi-Rad J, Quispe C, Castillo CMS, et al. Ellagic Acid: A Review on Its Natural Sources, Chemical Stability, and Therapeutic Potential. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 3848084. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X. T., Chen, Y. Y., Yue, S. J., Xu, D. Q., Fu, R. J., & Tang, Y. P. Zhongguo Zhong yao za zhi = Zhongguo zhongyao zazhi = China journal of Chinese materia medica. 2022, 47, 5193–5202. [Google Scholar]

- Chojnacka, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A.; Skrzypczak, D.; Mikula, K.; Młynarz, P. Phytochemicals containing biologically active polyphenols as an effective agent against Covid-19-inducing coronavirus. J Funct Foods. 2020, 73, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketsuwan, N.; Leelarungrayub, J.; Kothan, S.; Singhatong, S. Antioxidant constituents and activities of the stem, flower, and leaf extracts of the anti-smoking Thai medicinal plant: Vernonia cinerea Less. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017, 11, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketsuwan, N.; Leelarungrayub, J.; Kothan, S.; Singhatong, S. Antioxidant constituents and activities of the stem, flower, and leaf extracts of the anti-smoking Thai medicinal plant: Vernonia cinerea Less. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017, 11, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzepka, Z.; Bębenek, E.; Chrobak, E.; Wrześniok, D. Synthesis and Anticancer Activity of Indole-Functionalized Derivatives of Betulin. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin AS, Engel S, Smith BA, et al. Structure and biological evaluation of novel cytotoxic sterol glycosides from the marine red alga Peyssonnelia sp. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010, 18, 8264–8269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.L.C.; Freire, C.S.R.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Silva, A.M.S. Recent Developments in the Functionalization of Betulinic Acid and Its Natural Analogues: A Route to New Bioactive Constituents. Molecules 2019, 24, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer-Dubowska, W.; Narożna, M.; Krajka-Kuźniak, V. Anti-Cancer Potential of Synthetic Oleanolic Acid Derivatives and Their Conjugates with NSAIDs. Molecules 2021, 26, 4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye S, Zhong J, Huang J, et al. Protective effect of plastrum testudinis extract on dopaminergic neurons in a Parkinson's disease model through DNMT1 nuclear translocation and SNCA's methylation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández del Río, L.; Gutiérrez-Casado, E.; Varela-López, A.; Villalba, J.M. Olive Oil and the Hallmarks of Aging. Molecules 2016, 21, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhulipalla, H.; Syed, I.; Munshi, M.; Mandapati, R.N. Development and Characterization of Coconut Oil Oleogel with Lycopene and Stearic Acid. J Oleo Sci. 2023, 72, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Sun L, Zhao D, et al. Adenosine and L-proline can possibly hinder Chinese Sacbrood virus infection in honey bees via immune modulation. Virology 2022, 573, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.C. Solvent effects and improvements in the deoxyribose degradation assay for hydroxyl radical-scavenging. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 2083–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, X.C.; Tian, Y.G.; Lin, Q.Q.; Xie, H.; Lu, W.B.; Chi, Y.G.; Chen, D.F. Lyophilized aqueous extracts of Mori Fructus and Mori Ramulus protect Mesenchymal stem cells from *OH-treated damage: bioassay and antioxidant mechanism. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 16, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.C.; Wang, T.T.; Liu, J.J.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhang, J.; Lin, J.; Zhao, Z.X.; Chen, D.F. Effect and mechanism of wedelolactone as antioxidant-coumestan on •OH-treated mesenchymal stem cells. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, J.; Li, J.; Tang, B.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Yan, Y. Standards-Based UPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap MS Systematically Identifies 36 Bioactive Compounds in Ampelopsis grossedentata (Vine Tea). Separations 2022, 9, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Cai, R.; Chen, B.; Jiang, G.; Liang, Y.; Chen, X. Identification and Semi-quantification of 36 Compounds from Violae Herba (Zihuadiding) via UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap-MS/MS as well as Proposal of Anti-counterfeiting Quality-marker for Pharmacopeia. Chromatographia. 2024, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Qin, W.; Liang, M.; Liu, Q.; Chen, D. Antioxidant and Cytoprotective effects of Pyrola decorata H. Andres and its five phenolic components. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019, 19, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

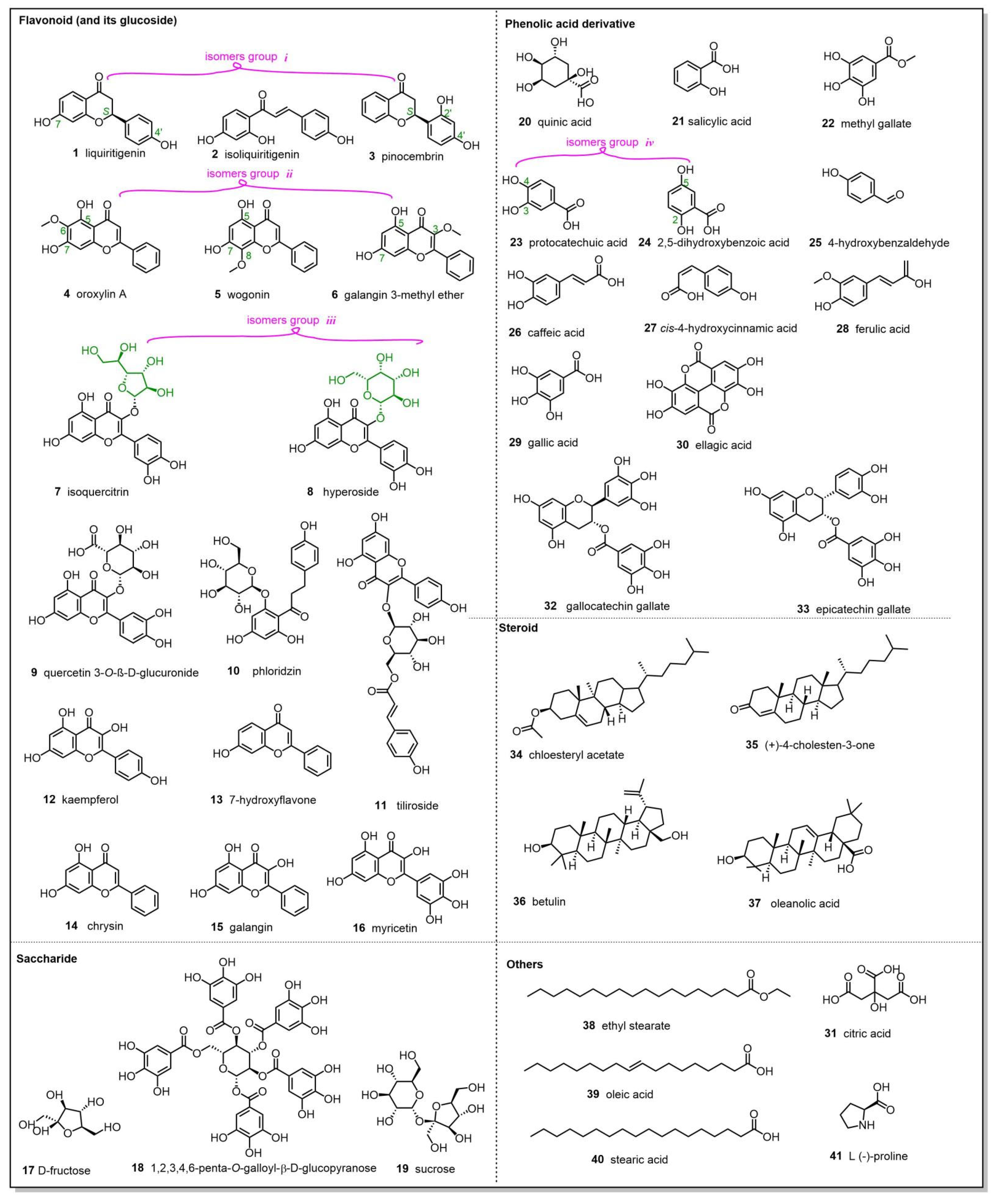

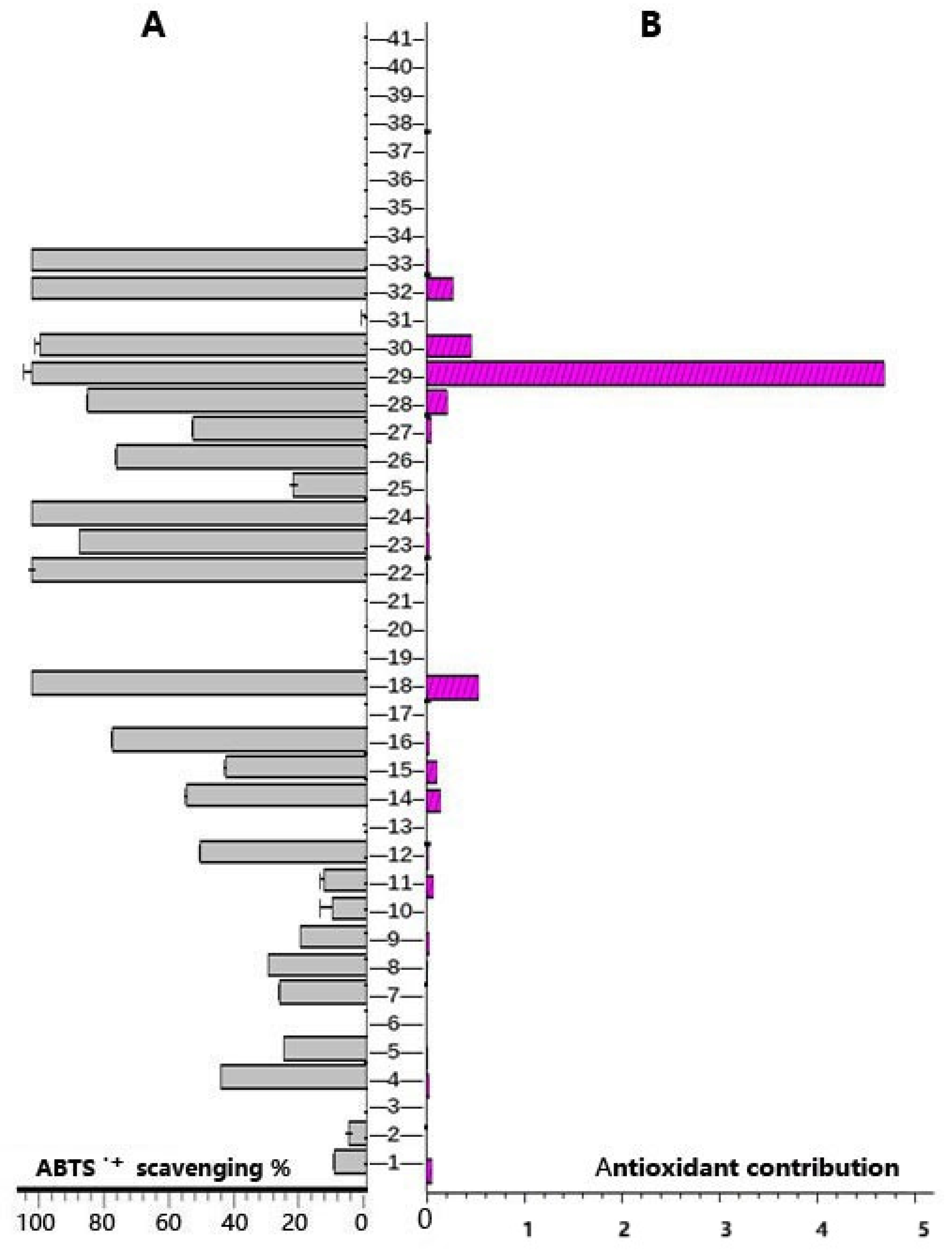

| No. | RTmin | Name | Molecular ion | Observedm/z value | Theoreticalm/z value | Error(δ ppm) | Content (mg/g)n=3 | Characteristic MS/MS fragment peak m/z | Bioactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

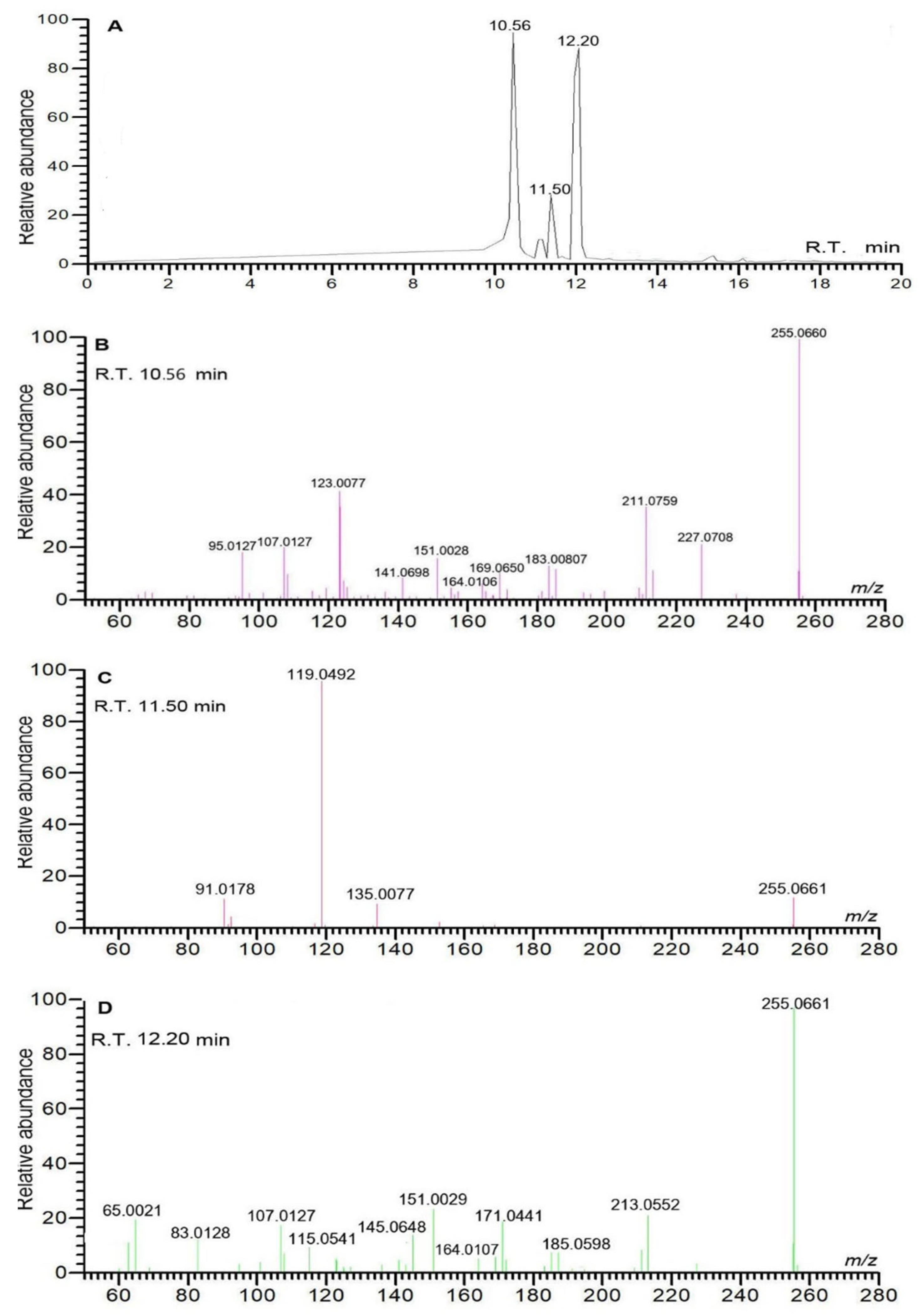

| 1 | 10.56 | liquiritigenin | C15H11O4- | 255.0661 | 255.0663 | 0.7843 | 0.577±0.013 | 255.0659, 119.0492, 91.0178 | anti-inflammatory [19] |

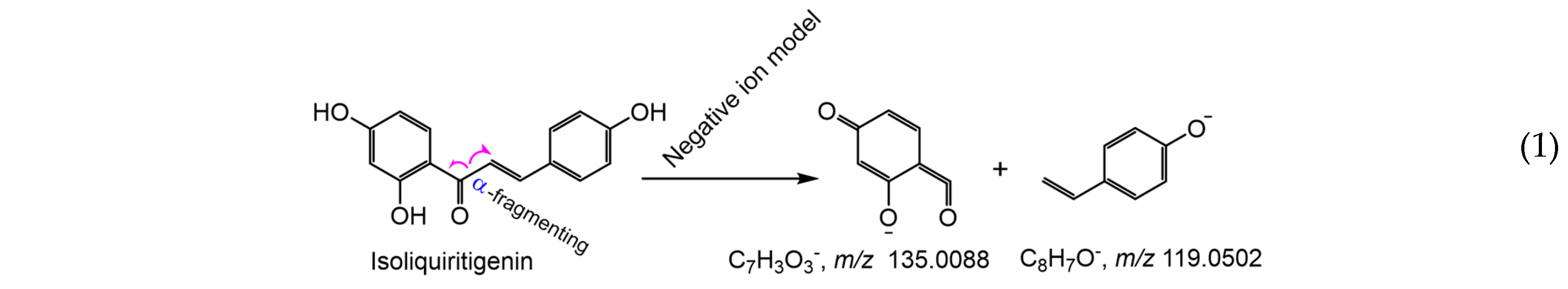

| 2 | 11.50 | isoliquiritigenin | C15H11O4- | 255.0661 | 255.0663 | 0.7843 | 0.012±0.000 | 255.0661, 119.0492, 91.0178 | antitumor [20] |

| 3 | 12.20 | pinocembrin | C15H11O4- | 255.0662 | 255.0663 | 0.3921 | 0.072±0.000 | 255.0661, 213.0552, 151.0029 | antitumor [21] |

| 4 | 12.29 | oroxylin A | C16H11O5- | 283.0612 | 283.0612 | 0 | 0.048±0.002 | 283.0611, 268.0377 | antioxidant [22] |

| 5 | 12.35 | wogonin | C16H11O5- | 283.0611 | 283.0612 | 0.3533 | 0.026±0.001 | 283.0611, 163.0027, 268.0374 109.9998 | anti-inflammatory [23] |

| 6 | 12.52 | galangin 3-methyl ether | C16H11O5- | 283.0612 | 283.0612 | 0 | 0.012±0.000 | 239.0346, 211.0395, 167.0494 | antibiotic [24] |

| 7 | 9.54 | isoquercitrin | C21H19O12- | 463.0873 | 463.0882 | 1.9438 | 0.017±0.002 | 463.0874, 300.0273, 271.0247 255.0298 | anti-inflammatory [25] |

| 8 | 9.43 | hyperoside | C21H19O12- | 463.0875 | 463.0882 | 1.5118 | 0.025±0.002 | 463.0874, 300.0273, 271.0247 | anti-inflammatory [26] |

| 9 | 9.57 | quercetin 3-O-β-D-glucuronide | C21H17O13- | 477.0674 | 477.0675 | 0.2096 | 0.138±0.005 | 301.0353, 151.0028, 109.0284 | antimicrobial [27] |

| 10 | 9.93 | phloridzin | C21H23O10- | 435.1280 | 435.1297 | 3.9080 | 0.034±0.001 | 273.0770, 167.0341, 123.0442, 119.0492 | antioxidant [28,29] |

| 11 | 10.96 | tiliroside | C30H25O13- | 593.1298 | 593.1301 | 0.5059 | 0.542±0.007 | 285.0397, 255.0292, 227.0341 | antioxidant [30] |

| 12 | 11.36 | kaempferol | C15H9O6- | 285.0405 | 285.0405 | 0 | 0.033±0.000 | 285.0405, 117.0335, 93.0334 | anti-inflammatory [31] |

| 13 | 11.93 | 7-hydroxyflavone | C15H9O3- | 237.0553 | 237.0557 | 1.6877 | 0.027±0.000 | 237.0553, 208.0524, 91.0178 | antibacterial [32] |

| 14 | 12.51 | chrysin | C15H9O4 - | 253.0504 | 253.0506 | 0.7905 | 0.267±0.002 | 251.0500, 209.0598, 143.0491 | antitumor [33] |

| 15 | 12.67 | galangin | C15H9O5- | 269.0456 | 269.0455 | 0.3717 | 0.247±0.001 | 269.0456, 169.0650 | anti-inflammatory [34] |

| 16 | 9.86 | myricetin | C15H9O8- | 317.0301 | 317.0303 | 0.6309 | 0.036±0.005 | 317.0301, 151.0028, 137.0234, 109.0284 | antioxidant [35] |

| 17 | 13.82 | D-fructose | C6H13O6+ | 181.0715 | 181.0707 | 4.4198 | 0.247±0.000 | 163.0385, 149.0229, 65.0393 | antioxidant [36] |

| 18 | 9.46 | 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-β-D-glucopyranose | C41H31O26- | 939.1146 | 939.1109 | 3.9403 | 0.547±0.700 | 169.0134, 125.0234, 107.0127, 95.0126 | antioxidant [37] |

| 19 | 0.53 | sucrose | C12H21O11- | 341.1086 | 341.1089 | 0.8797 | 0.986±0.048 | 341.1086, 179.0553, 161.0448, 89.0233 | sweetening agent [38] |

| 20 | 0.55 | quinic acid | C7H11O6- | 191.0555 | 191.0561 | 3.1413 | 0.377±0.003 | 191.0555, 93.0335, 85.0283 | anti-oxidant [39] |

| 21 | 8.18 | salicylic acid | C7H5O3- | 137.0234 | 137.0244 | 7.2992 | 0.056±0.001 | 137.0234, 93.0333 | anti-inflammatory[40,41] |

| 22 | 3.06 | methyl gallate | C8H7O5- | 183.0291 | 183.0299 | 4.3715 | 0.007±0.000 | 183.0291, 124.0156, 78.0099 | anti-inflammatory [42] |

| 23 | 1.6 | protocatechuic acid | C7H5O4- | 153.0186 | 153.0193 | 4.5751 | 0.026±0.006 | 153.0186, 109.0285, 108.0206 | antimicrobial [43] |

| 24 | 2 | 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid | C7H5O4- | 153.0186 | 153.0193 | 4.5751 | 0.015±0.003 | 153.0182, 109.0284, 108.0206 | improvements in vascular function [44] |

| 25 | 3.22 | 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde | C7H5O2- | 121.0285 | 121.0295 | 8.2644 | 0.006±0.001 | 121.0285, 92.0257 | improvements in vascular function [45,46] |

| 26 | 4.6 | caffeic acid | C9H7O4- | 179.0339 | 179.0350 | 6.1452 | 0.012±0.000 | 179.0345, 136.0474,135.0441,133.0282 | antibacterial [47] |

| 27 | 7.11 | cis-4-Hydroxycinnamic acid | C9H7O3- | 163.0392 | 163.0401 | 5.5214 | 0.094±0.005 | 119.0492 | anti-SARS [48] |

| 28 | 8.71 | ferulic acid | C10H9O4- | 193.0496 | 193.0506 | 5.1813 | 0.258±0.301 | 193.0136, 178.0262, 134.0364 | antibacterial [49,50] |

| 29 | 0.86 | gallic acid | C7H5O5- | 169.0133 | 169.0142 | 5.3254 | 4.800±0.103 | 169.0133, 125.0234 | antioxidant [51] |

| 30 | 9.5 | ellagic acid | C14H5O8- | 300.9989 | 300.9990 | 0.3333 | 0.485±0.000 | 300.9990, 145.0286, 117.0335 | antioxidant [52] |

| 31 | 0.52 | citric acid | C6H7O7- | 191.0189 | 191.0197 | 4.1884 | 0.757±0.007 | 111.0078, 87.0076, 85.0248 | improvements in vascular function [53] |

| 32 | 7.98 | gallocatechin gallate | C22H17O11- | 457.0736 | 457.0776 | 8.7527 | 0.274±0.004 | 169.0133, 125.0234 | antiviral [54] |

| 33 | 8.68 | epicatechin gallate | C22H17O10- | 441.0831 | 441.0827 | 0.9070 | 0.020±0.000 | 289.0715, 169.0134, 125.0234, 109.0285 | antioxidant [55] |

| 34 | 16.03 | cholesteryl acetate | C29H49O2+ | 429.3706 | 429.3727 | 4.8951 | 14.418±1.041 | 429.3706, 165.0912, 91.0545, 81.0705, | antitumor[56] |

| 35 | 16.67 | (+)-4-cholesten-3-one | C27H45O+ | 385.3459 | 385.3465 | 1.5584 | 0.003±0.000 | 385.3454, 109.0649, 97.0650, 91.0545 | antitumor[57] |

| 36 | 15.38 | betulin | C30H51O2+ | 443.3878 | 443.3884 | 1.3544 | 0.130±0.005 | 443.3497, 105.0700, 91.0547, 81.0705 | antitumor[58] |

| 37 | 15.18 | oleanolic acid | C30H47O3- | 455.3531 | 455.3531 | 0 | 0.026±0.004 | 455.3531 | antitumor [59] |

| 38 | 16.22 | ethyl stearate | C20H39O2- | 311.2956 | 311.2956 | 0 | 0.209±0.013 | 311.1682, 183.0114, 119.0492 | antioxidant [60] |

| 39 | 15.62 | oleic acid | C18H33O2- | 281.2487 | 281.2486 | 0.3558 | 0.046±0.000 | 281.2487 | antioxidant [61] |

| 40 | 15.8 | stearic acid | C18H35O2- | 283.2643 | 283.2643 | 0 | 0.197±0.002 | 283.2643, 92.1626 | antioxidant [62] |

| 41 | 0.54 | L-(-)-proline | C5H10NO2+ | 116.0708 | 116.0706 | 1.7241 | 0.940±0.045 | 116.0706, 70.0657 | immune modulation [63] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).