1. Introduction

Autoimmune diseases (ADs) are becoming more widespread in Westernized societies, with annual increases in the global incidence and prevalence of up to 19.1% and 12.5%, respectively [

1].

The possible causes of ADs include genetic factors in an immune susceptible host, and environmental factors such as lifestyle, diet, drugs, infections, and agricultural and industrial practices [

2]. In addition to the increase in frequency, ADs are often co-associated, and 25% of patients with these diseases develop other comorbid ADs [

3].

The term Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs), refers to disorders involving, either simultaneously or sequentially, more organs [

4]. Diet may contribute to the incidence of IMIDs through interaction mechanisms such as direct food antigens that cause intolerance/allergies, intestinal microbiome alterations, and intestinal permeability [

2].

Abnormal inflammatory responses are closely associated with IMIDs [

4]. Chronic metabolic inflammation has been associated, among other factors, with the Western diet. Several components of the Western diet, such as fats, refined sugars, processed food, and a low dietary fiber intake, can cause inflammatory reactions in the immune system [

5]. The Western diet is associated with a risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and intestinal bowel diseases [

6,

7].

1.1. Influence of Dietary Mechanisms on IMIDs

1.1.1. Diet Composition, Intestinal Microbiota, and Dysbiosis

The intestinal microbiota (IM) comprises all intestinal microorganisms, including their genes, proteins, and metabolic products. IM imbalances, known as dysbiosis, can influence the development of immune disorders through T lymphocyte (T cell) activity [

8].

Microbial dysbiosis is the primary cause of local inflammation and IMIDs such as colitis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Three systematic reviews have been published on the association between IM and disease activity or IBD therapy [

9].

RA [

10], multiple sclerosis (MS) [

11,

12], and other neurological disorders [

13] can also be caused by gut dysbiosis. Gut microbiota changes have been related to disease activity [

10].

The composition of the IM can be affected by diet [

14], and it may influence the susceptibility to intestinal inflammation and autoimmunity [

15], as well as predict susceptibility to IMIDs, such as RA [

10]. Diet can be a therapeutic strategy for preventing and treating RA, MS, and IBD by modulating the IM [

10,

16,

17].

Dietary fibers are non-digestible carbohydrates that constitute an important energy source for the IM. Alterations in their consumption modify the structure and function of the IM within days [

18]. High-fiber foods improve the diversity of the IM as part of a balanced diet. Dietary fiber consumption can improve remission rates in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) and RA as part of a proper diet [

10,

19] and can help reduce joint pain in patients with RA [

10].

IBD onset has been associated with high carbohydrate and low vegetable intake [

20]. Sugar intake has also been associated with an increased risk of IBD [

16]. Reducing carbohydrates in the diet can help improve the balance between the IM and immune function in RA [

10]. High glucose and fructose intake can reduce microbial diversity in the long term; therefore, food choices affect the IM [

13,

21].

Excessive consumption of red meat can lead to changes in the microbiota and an increased risk of RA [

22]. Red meat and excessive dairy may also increase the risk of acute flares in IBD and psoriasis [

23].

N-glycolylneuraminic acid, present in red and processed meats, can be regulated by specific gut microbiota bacteria; however, N-glycolylneuraminic acid accumulation causes inflammation [

24].

A high-sodium diet can also lead to dysbiosis, which promotes a micro-inflammatory state and autoimmune processes [

10].

The microbiota modulates the gut immune system through omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are useful for maintaining gut health. However, the composition of the microbiota is complex, and individualized diets must be designed to account for the needs of each patient [

25].

Interventions related to diet and IM for treating CD, RA, and MS are being studied [

10,

12,

26]. Microbiome signatures are essential for controlling and preventing ADs [

11], and dietary patterns correlating with bacteria groups have been identified. Diet can affect the inflammatory responses in the gut through microbial mechanisms [

16].

1.1.2. Diet Composition and Intestinal Permeability

In addition to its essential role in regulating homeostatic processes, the intestinal barrier (IB) contains the immune system of the intestinal mucosa [

27]. Impaired IB function can activate autoimmune responses, thereby initiating and developing IMID [

28]. As a consequence of a leaky gut, increased inflammation and risk of malabsorption of essential macro- and micronutrients occurs. For example, vitamin D deficiency has been reported as a risk factor for some IMIDs such as RA and MS [

2].

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids can help maintain the IB’s integrity. A low omega-3/omega-6 fatty acid ratio promotes inflammation and increases the risk of RA [

10]. Red and processed meats contain elevated levels of heme iron, which have been correlated with altering the IB [

23]. A high-fat diet can lead to dysregulated microbiota and metabolites, followed by IB dysfunction in ulcerative colitis (UC) [

29]. Consumption of wheat and other cereals can contribute to chronic inflammation and ADs by increasing intestinal permeability [

30]. Sourdough fermentation degrades wheat alpha-amylase/trypsin inhibitors and reduces pro-inflammatory activity [

31].

The IB can be negatively affected by alcohol and food additives such as sweeteners, emulsifiers, and advanced glycation end products produced during food processing [

13].

1.1.3. Diet Composition, Inflammation, and Immune System

The immune system contains the highest energy-consuming cells in the body [

2]. Nutrition influences the inflammatory cascade at the molecular level and the IM [

32]. Both, pro- and anti-inflammatory signs, that can modulate gut immune responses, could be generated by dietary components, which directly interact with the innate and adaptive immune system [

33].

Potential interactions between diet and autoimmunity have been studied by creating a database of overlap between human autoimmune and food epitopes. Epitopes implicated in ADs have been identified in commonly consumed foods. It is thought that foods containing epitopes implicated in each AD may exacerbate symptoms with frequent consumption [

34].

In addition to interacting at the molecular level, diet indirectly affects inflammation by modulating the IM. An increase in antigen-specific regulatory T cells may occur rapidly in response to IM alterations. Food contains components that can act as substrates for microbiota; high-fiber diets have been shown protective in animal models of arthritis. Additionally, IM metabolites with immunoregulatory properties include short-chain fatty acids, protein catabolites, and vitamins [

11,

35].

Dietary inflammatory index

Inflammatory biomarker changes are important when comparing the effectiveness of specific composition diets for symptom improvement in IMID. When comparing groups of diets with different compositions, it’s important to know the potential pro- or anti-inflammatory capacity of all their components. The Dietary Inflammatory Index DII is a literature-derived population-based dietary score to assess the inflammatory potential of an individual’s overall diet. The search was limited to articles that assessed the association of one or more of 45 food and nutrient parameters with six inflammatory biomarkers (IL-1beta, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and CRP levels).

The inflammatory potential for each food parameter was scored +1, -1, or 0 if it increased, decreased, or had no effect respectively on these inflammatory biomarkers. All of the “food parameter-specific DII scores” are added through a specific procedure to calculate the “overall DII score”. (maximally pro-inflammatory diet DII score: +7.98, maximally anti-inflammatory DII score: -8.87, and median: +0.23) [

36,

37].

The DII, and the energy-adjusted DII (E-DII), have been used in numerous studies in recent years [

37].

1.2. Obesity

Obesity is an epidemic in the Western world and is defined as a body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m

2. The main characteristics of obesity include the accumulation and rearrangement of different types of body fat, subclinical chronic inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction. Obesity increases susceptibility to various IMIDs [

38]. Obesity is associated with RA, CD, MS, and psoriasis. Immunoregulatory effects are achieved through caloric restriction [

7,

12]; however, adherence to a proper diet is a major obstacle. Patients adapt more easily to a time-restricted diet than caloric restriction [

39].

The odds of RA remission decrease with obesity. Individuals who are overweight and obese have a 1.27-fold increased risk of RA [

40]. Obesity negatively affects disease activity in axial spondyloarthritis (SpA) and RA [

41,

42], and reduces the probability of an anti-tumor necrosis factor response in RA [

43]. Weight loss impacts disease activity in SpA [

44]. Non-pharmacological and non-surgical interventions for weight loss are associated with reduced psoriasis severity in patients who are overweight or obese [

45].

The IM depends on dietary patterns and is individualized. Weight loss and decreased inflammatory marker levels have been linked to different microorganisms. The

Prevotella-to-

Bacteroides ratio is used to predict body weight and fat loss success). [

46].

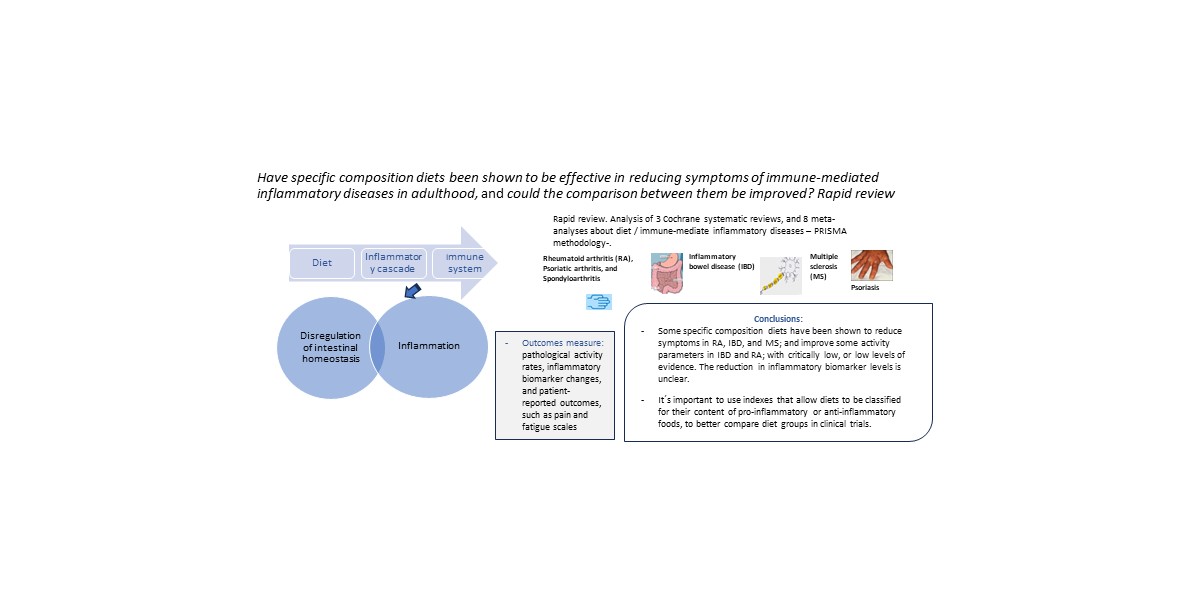

We hypothesize that a specific diet composition influences the improvement of IMID symptoms. This study aimed to review the evidence on specific diet composition effects on the symptoms of some IMIDs (RA, psoriatic arthritis, SpA, MS, IBD [remission maintenance of CD, UC], and psoriasis) in adult patients regarding sex and disease duration. Cochrane systematic reviews and meta-analyses were evaluated, focusing on intervention studies and assessing pathological activity rates, inflammatory biomarker changes, and patient-reported outcomes, such as pain and fatigue scales.

2. Methods

We followed a standardized methodology according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 (PRISMA) [

47,

48].

2.1. Search Methods for Identifying Studies

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were reviewed using PubMed, EMBASE, from inception to September 2024, and Google Scholar. The search strategy is presented in

Supplementary Table S1 (MEDLINE and EMBASE). Two researchers independently conducted the review.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria Used for Literature Search and Screening

Inclusion criteria: Eligible studies included adults with IMIDs (RA, psoriatic arthritis, SpA, MS, IBD [remission maintenance of CD, UC], and psoriasis). Intervention: Diet. Control: Placebo/other control interventions. Study types: Systematic reviews/meta-analyses, focusing on intervention studies. Language: English.

Exclusion criteria: Studies including pediatric patients, Irritable-bowel syndrome, preoperative nutritional interventions, enteral or parenteral nutrition, fasting-mimicking diets, weight loss, exclusion diets + partial enteral nutrition, and studies that sought the effect of certain foods or nutrients (supplements, nutraceuticals, micronutrients, vitamin D) without a clear diet designation.

Limitations: Not all IMIDs (systemic lupus, type 1 diabetes, asthma) [

4], were included and comprehensively reviewed.

2.3. Data Extraction

Two researchers independently assessed the articles. The articles were reviewed, and the data was tabulated for the selected variables. A third author helped reach a consensus in cases of disagreement.

2.4. Outcomes Measures

MS: Change in

Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [

49,

50], (ranges from 0 [no neurological abnormality] to 10 [death due to MS]),

Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 [

51], and the

Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) [

52]. Safety: Number of severe adverse events associated with dietary intervention during the follow-up period.

IBD: Change in

clinical disease activity index [

53], inflammatory biomarkers (fecal calprotectin, C-reactive protein [CRP], and albumin), functional gastrointestinal symptoms (FGSs), and quality of Life (QoL).

RA: Change in

disease activity score 28 (DAS 28) [

54], changes in CRP and interleukin [IL]-6), pain scales, and all relevant efficacy and safety outcomes.

Psoriatic arthritis, SpA, and psoriasis: all relevant efficacy and safety outcomes.

Standardized mean differences (SMD): An SMD≥0.2 was considered a small effect, ≥0.5 as a medium-sized effect, and ≥0.8 as a large effect [

55].

2.5. Quality of Meta-Analyses

We assessed the methodological quality of each meta-analysis (MA) using the AMSTAR 2, a validated measurement tool for evaluating systematic reviews and meta-analyses [

56]. It consists of 16 items that assess methodological quality as one of four grades (high, moderate, low, or critically low) and includes ratings for the quality of the search, reporting, risk of bias, and transparency of the meta-analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Eligible Studies

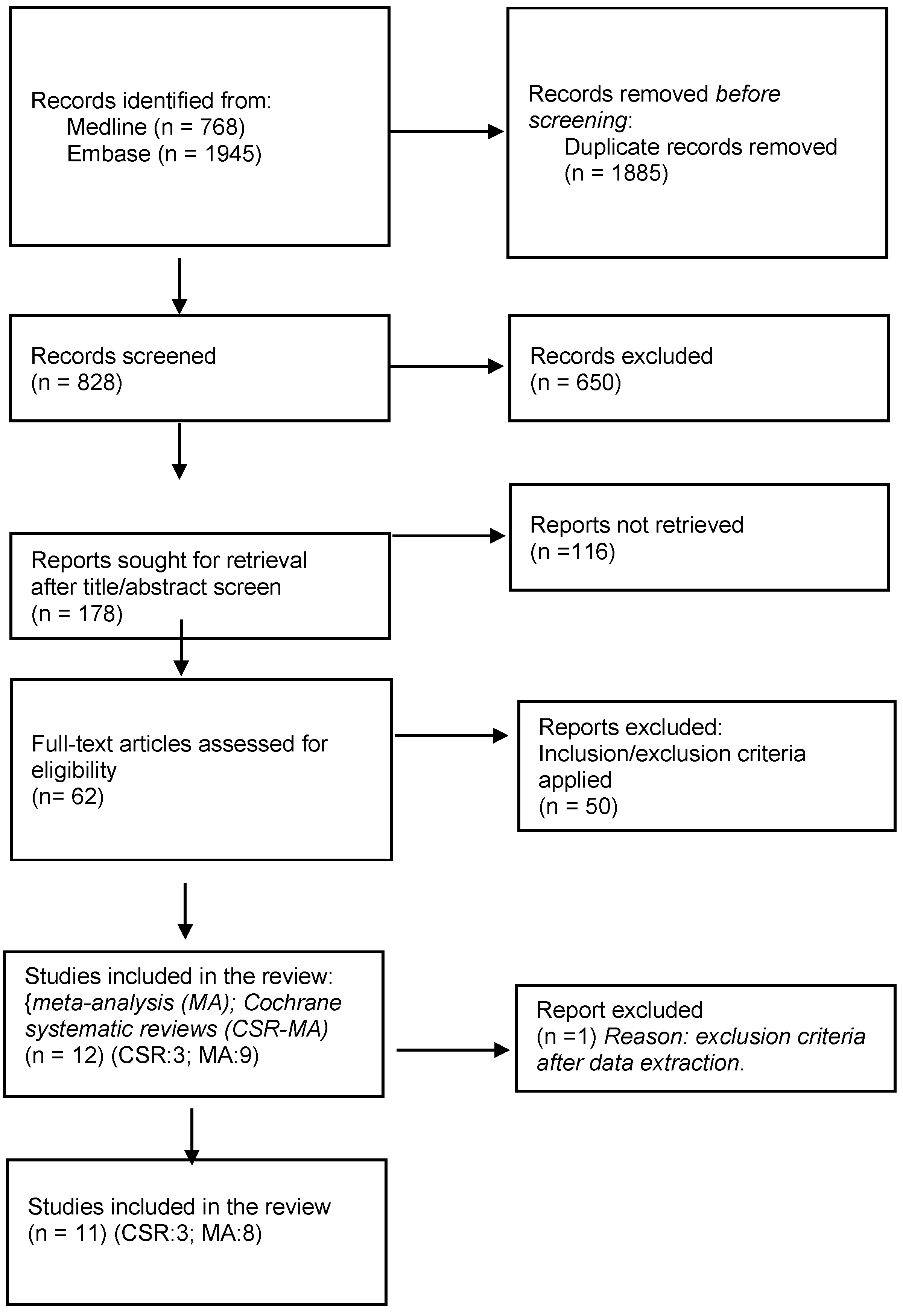

A Flow chart is shown in

Figure 1 with details of included studies and the selection processes.

3.2. Cochrane Systematic Reviews

3.2.1. Cochrane SR-MA on the Outcomes of Diet on Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases

The Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (SR-MA) Informing the 2021 EULAR (Gwinnut 2022), “Effects of Diet on the Outcomes of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases” (RMDs), analyzed several rheumatic pathologies, but studies of experimental diets were only analyzed in RA [

57]. The evidence for most dietary exposures in RA was classified as low or very low because of the small number of studies and sample sizes. This SR-MA evaluated one MA on diet for fatigue in RA (Cramp, 2013. Cochrane Database Syst Rev) [

58], which reported no significant effect of the Mediterranean diet on fatigue, based on an analysis of the Skoldstam randomized controlled trial (RCT) (2003). Dietary biomarkers weren’t evaluated in this trial.

3.2.2. Cochrane SR on the Outcomes of Diets in IBD

SR Cochrane (Limketkai, et al.

, 2019) [

59], focused on diets for induction and remission maintenance in IBD (low refined carbohydrate diet, symptoms-guided diet, low red processed meat diet, exclusion diets [low disaccharides, grains, saturated fats, red and processed meats versus control] in inactive CD, and anti-inflammatory diets [Alberta-based, carrageenan-free diet, and milk-free diet versus control] in inactive UC). This study analyzed RCTs that compared the intervention diet versus the control diet for the induction of remission in active CD and UC, and in inactive CD and UC. Studies that exclusively focused on enteral nutrition, oral nutrient supplementation, medical foods, probiotics, and parenteral nutrition were excluded.

Limketkai's 2019 SR findings showed that the effects of dietary interventions on CD and UC were uncertain; therefore, more RCTs and a consensus on the composition of these interventions are needed. For Induction of remission in active CD, the mean difference in the health-related quality of life (IBDQ) score between the symptoms-guided diets, and the control diet (1 study, 51 participants, and follow-up period unclear), was very low certainty evidence. After analysis of surrogate biomarkers of inflammation, it was uncertain whether highly restricted organic diets lead to a difference in CRP or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) -based on the analysis of the study by Bartel 2008-. For maintenance of remission in inactive CD and UC, Riordan´s 1993 study (Limketkai´s SR), assessed the effect of symptoms-guided diets on CRP, after 24 months. There were no significant differences. No further details were provided. Evidence from the analysis of two studies (Jones 1985, and Jordan 1993) shows that the effect of symptom-guided diets on ESR is uncertain. For inactive UC surrogate inflammatory biomarkers One study with 12 participants (Bhattacharyya 2017), reported fecal calprotectin, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α and it is uncertain whether carrageenan-free diets improve these parameters at 12 months.

The number of studies and patients was too low to be able to compare diet variables with similar characteristics.

Limketkai et al. SR-MA 2022, “Dietary Interventions for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases”, with a similar publication title to Limketkai Cochrane Review 2019, studied solid food diets for IBD remission induction or maintenance. They concluded that partial enteral nutrition potentially benefits CD remission induction and maintenance [

60].

3.2.3. Cochrane SR on the Outcomes of Diets MS

The 2019 Cochrane systematic review on diet and MS analyzed dietary interventions except for those including vitamin D, on MS-related outcomes, including relapses, disability progression, and magnetic resonance imaging measures. They concluded that there was insufficient evidence to determine whether dietary interventions impacted MS-related outcomes [

61].

3.3. Meta-Analyses

Information regarding the included meta-analyses is presented in Table 1. The AMSTAR 2 ratings are shown in Table 2: critically low (3 studies, 37.5%) and low (5 studies, 62.5%). The main limitations are the absence of blinding in the therapeutic maneuver, outcome measures, and therapeutic compliance measures, as well as the great variability in the analyzed diets and inflammatory effects.

Meta-analyses on diet and IMID symptoms are summarized below.

3.3.1. RA, Psoriatic Arthritis, and SpA

Schönenberger SR-MA, 2021 [

62]. (Mediterranean, vegetarian, vegan, and ketogenic diets-all considered anti-inflammatory diets-/ control), analyzed seven RCTs and concluded that anti-inflammatory diets resulted in significantly lower pain than ordinary diets in RA. Subgroup analysis showed that the Mediterranean diet tended to have better results in improving pain than vegetarian or vegan diets. All the studies had a high risk of bias. Owing to the lack of blinding, pain data (patient-reported outcomes) could have been biased, and the evidence was very low (Table 1). Five of the seven studies are analyzed to summarize the effects of anti-inflammatory diets on CRP levels. There were no significant differences. Patients who followed anti-inflammatory diets lost more weight than patients in the control groups, and their BMI decreased. RCTs with a longer intervention period (13 months) tended to have significant effects and a higher baseline BMI appeared to have a greater improvement in pain. The study included mainly female patients.

Genel SR-MA 2020 [

63] (Table 1), evaluated the effects of a low-inflammatory diet intervention in adult patients with RA, osteoarthritis (OA), or seronegative arthropathy (psoriatic, reactive, ankylosing spondylitis, or IBD-related). Only one RCT and one prospective trial about patients with RA were analyzed, with a very low level of evidence. No validated tool was used to assess dietary compliance in these trials. Genel et al. highlighted the differences between OA and RA in terms of the efficacy of dietary interventions. Patients with RA who followed an anti-inflammatory diet showed greater improvements in pain and physical function. No statistically significant benefit was observed in patients with OA. RCTs with significant effects were those with the longest intervention periods. Outcomes were recorded from 2 to 4 months and beyond. Patients in the intervention group with the highest baseline BMI had greater pain improvement. A low-inflammatory diet can cause weight loss, and biomarker improvements can occur independently of weight change. In Genel´s MA of inflammatory biomarkers change scores, Skoldstam´s CRP results in RA, and Schell´s and Dier´s IL6 results in OA were utilized.

Turk SR-MA 2023 [

64] (11 RCTs) studied dietary interventions (gluten-free vegan, anti-inflammatory, and Mediterranean diets/controls) in patients with RA. The meta-analyses of the DAS 28 (4 RCTs, 191 patients) and pain, showed a very low level of evidence and significant symptom reduction when the diet was modified. The anti-inflammatory diet achieved good results (reduced swollen joint count, tender joint count, pain, and DAS 28) (Table 1). inflammatory biomarkers change scores were not evaluated in this MA.

No specific systematic reviews and meta-analyses were found on diet and psoriatic arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. A systematic review (2022) updated the evidence on the efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological treatments to inform the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society-European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology recommendations for managing SpA. No conclusions were reached because the studies were heterogeneous in the type, duration, and frequency of treatment [

65].

3.3.2. IBD

Comeche SR-MA 2020 on IBD [66] (Table 1), 31 research studies were selected for qualitative synthesis, only 10 of them for MA. They analyzed different predefined diets for patients with active IBD and those in remission based on decreased consumption of some types of pro-inflammatory foods or an increase in others to improve IM, which is compatible with other medical treatments. CDAI was significantly improved in the group treated with diet but with reasonable doubts due to the high heterogeneity of the data. No differences were observed for some inflammatory markers (albumin, CRP, and FC). An improvement was observed with the low microparticles, semi-vegetarian, and immunoglobulin exclusion diets (IGED). Foods causing a certain degree of intolerance in patients with CD were identified. The vegetarian diet was the most studied and beneficial for these patients, and the best results were obtained in studies that included patients with active diseases. A low fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diet decreased symptoms in most individuals with IBD. However, it can also produce deficiencies when maintained for long periods, which can be avoided by supplementation. Specific carbohydrate diets and low FODMAP diets can contribute to vitamin D deficiency. IGEDs improve IBD activity, and a gluten-free diet, despite low adherence, can be useful in managing IBD.

The LFD meta-analysis of Zhan on IBD 2018, 2 RCTs, and 4 before-after studies, [

67] (Table 1) showed significant improvement in diarrhea, satisfaction with gut symptoms, abdominal bloating, abdominal pain, fatigue, and nausea, except for the constipation response.

LFD meta-analysis of Peng on IBD, 2022, [

68] (Table 1),4 RCTs and 5 before– after studies, showed a benefit in FGSs and QoL but no improvement in stool consistency and mucosal inflammation in patients with IBD. Symptom improvement was observed in bloating, wind or flatulence, borborygmi, abdominal pain, and fatigue or lethargy, but not for nausea and vomiting. Only two studies assessed the QoL store using the short IBD questionnaire (SIBDQ) showing a reduction in total SIBDQ score. However, two studies evaluated QoL and didn´t observe significant differences using the IBS QoL.

Inflammatory biomarkers change scores were not evaluated In Zhan and Peng. meta-analyses.

3.3.3. MS

The MA cumulative evidence on diet in MS, Guerrero 2022 [

69] analyzed eight low-evidence RCTs with different predefined diets (Table 1). Dietary intervention is associated with reduced fatigue, increased QoL, no significant effect on EDSS, and no severe adverse events. (Table 1). The rationale for dietary interventions was to control inflammation and oxidative stress. The studies with the best results excluded or reduced saturated fats, white flour, dairy, sugar, and meats and recommended the intake of sufficient fruits, vegetables, and fish. A 12-hour fast at night provided good results. One of the studies examined in this MA (Bohlouli, 2021) [

70]. showed a relationship between the DII and MFIS. DII predicted MFIS in the modified Mediterranean diet group. The control diet (traditional Iranian diet) plan was adjusted for energy intake to avoid unexpected body weight changes. Only two RCTs (Mousavi et al, and Rezapour et al), found increased interleukin 4 (anti-inflammatory cytokine) in the intervention group. Among the eight diets investigated, the modified Mediterranean diet was easier to maintain (Mousavi et al, study diet adherence: 96,15%, Katz Sand: 90,3%, compared to restrictive diets -Irish et al: 50%, Bohlouli et al: 75,5%-).

The SR and network MA of Snetselaar, 2023 [

71]. jointly analyzed 10 RCTs and one uncontrolled parallel-group clinical trial (modified Paleolithic diet/low saturated fat diet) and established diet groups that were considered similar, such as the Mediterranean diet (Mediterranean and modified Mediterranean diets). It was concluded that dietary interventions such as the Paleolithic and Mediterranean diets can reduce MS-related fatigue and improve physical and mental QoL (Table 1). inflammatory biomarkers change scores were not evaluated.

Both studies [

69,

71] agree that it is difficult to reach a sufficient level of evidence in dietary studies to make recommendations. The dietary intervention potential and the benefit-risk ratio must be considered [

69].

3.3.4. Psoriasis

No MA or Cochrane SR, specifically identified for diet and psoriasis. A 2018 systematic review on dietary recommendations for adults with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation [

72], updated the literature based on prior systematic reviews. They concluded that dietary interventions can be added to standard medical therapies to reduce disease severity. Dietary weight reduction using a hypocaloric diet in patients with psoriasis who are overweight and obese was recommended.

4. Discussion

This review of COCHRANE SR, and meta-analyses

, mostly RCTs, provides a comprehensive critical assessment of the literature on the effects of diet on disease symptoms in patients with IMIDs. Most of the intervention diets that were analyzed restricted foods with inflammatory effects. The anti-inflammatory effects of specific nutrients are based on their ability to modulate the immune system [

2]. Consuming foods with high cholesterol, sugars, saturated fats [

73], wheat, and other cereals [

30] is associated with inflammation. This does not apply to the consumption of foods containing fiber, vitamins, and low levels of alcohol, herbs, and spices. The magnitude of these associations was small [

73].

4.1. Efficacy of Diets with Specific Compositions to Reduce IMID Symptoms

The limitation of this global review is that the meta-analyses included studies with small samples and were predominantly of poor quality. The selected meta-analyses were not homogeneous (dietary interventions/complete diets, unknown and possibly a diverse dietary inflammatory index (DII) of diets, patients with different baseline characteristics, and various types of habitual diets by country).

Similarly, the Harris-Benedict equation was sometimes used to determine energy needs, but intolerance tests were not performed to determine the baseline characteristics of the patients. In some studies, the level of adherence to the specified diet was extremely low, and patient preferences were not analyzed.

Adherence to a diet was not usually quantified as a primary MA result, with some exceptions [

69]. Different methods are used to monitor compliance, all of which are based on self-reported mean adherence. Among the various diets investigated, the modified Mediterranean diet was easier to maintain (90.3%–96.15%) than the restrictive diets (50%–75.5%).

Safety, defined as the number of severe adverse events associated with dietary interventions within the follow-up period in clinical trials, usually works in favor [

59,

69,

74].

This rapid review shows that dietary interventions have considerable potential. As the available evidence indicates, diets that reduce inflammatory foods should play a role in treating IMIDs. Some specific composition diets have been shown to reduce symptoms in RA, IBD, and MS; improve some activity parameters in IBD and RA; and QoL in MS and IBD; with critically low, or low levels of evidence.

Based on a recent systematic review of RCTs, there is evidence that some interventions, with Diet or Dietary Supplements, might have positive effects on DAS28, reducing the disease activity score in RA, positive findings need confirmation in future high-quality studies.[

75].

The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology recently published recommendations regarding lifestyle and diet for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases; they must be informed about no specific beneficial food types and should aim for a healthy weight [

57].

The British Dietetic Association consensus guidelines state that there is insufficient evidence to recommend an anti-inflammatory diet to maintain IBD remission. However, they do not consider the anti-inflammatory potential of most of the diets analyzed in the consensus, and they are not referenced as anti-inflammatory diets [

76].

Likewise, a systematic review of CDED, reducing exposure to individualized dietary components, concluded that it could be effective for inducting and maintaining remission in patients with mild to moderate CD [

77].

Regarding adulthood, the ESPEN guideline on Clinical Nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease recommendations indicates that Crohn's Disease Exclusion Diet CDED should be considered, with or without partial enteral nutrition (PEN) [

78,

79].

One MA on dietary interventions in UC (adults and children) supported dietary interventions to maintain clinical remission, with a low or very low level of evidence [

80].

A quality analysis of the existing guidelines on nutrition/diet in IBD revealed that they provide few recommendations and that 50% of them support low-quality evidence [

81].

Currently, the usefulness of diets with low inflammatory potential combined with biological therapy is being researched, published, and confirmed [

82]. This practice can improve the low level of evidence achieved thus far in trials comparing diets alone.

Supplementation regimens should be controlled for diets in clinical trials to accurately compare interventions, which is not a common practice. Adapting the diet to a patient’s needs is essential, considering unique characteristics when necessary (intolerances, malabsorption, intestinal strictures, and stenosis) [

78].

Obtaining the same level of evidence in dietary trials as in pharmacological trials is challenging because of the study designs and patient differences (microbiota, intolerances, allergies, BMI, opinions, level of adherence, comorbidities, and pharmacological treatment). These factors justify the need to individualize diets. The patient's energy needs and the inflammatory index of food should also be considered.

4.2. The Additive Effect of Different Diet Components Measurement

Usually, the studies did not analyze an index that would allow the composition of the diets to be objectively compared.

The additive effect of different diet components should be investigated to improve study methodologies [

44]. The composition of diets in the meta-analyses was reviewed, but most of the studies didn´t consider the DII scoring algorithm. It would be interesting to determine the DII of the diets compared in the various studies to assess heterogeneity.

In the review, we found that diets do not have a standard name for similar compositions, and sometimes diets with different compositions are associated with the same global name.

On the other hand, we observed that Cochrane reviews are very strict when comparing diets with the same name, obtaining very few patients for comparison, so it is difficult to conclude.

The Mediterranean, modified Mediterranean, and similar Mediterranean diets were included in the same group, in one of the analyzed meta-analyses [

71]., and perhaps it would be advisable to consider different inflammatory potentials for these three kinds of diets. Anti-inflammatory diet was compared in a separate group.

The network MA [

71], simultaneously reviewed all diets in a single analysis, combining direct and indirect evidence. At present, the effectiveness of network MA for validating all possible indirect comparisons may be questionable in providing robust evidence because, in general, RCTs conducted on diets are not blinded, with low adherence, heterogeneous (differences in baseline patient characteristics, diet compositions, controls, countries with various dietary factors, and diet duration).

4.3. DII May Be Correlated with Circulating Inflammatory Marker Levels

The meta-analysis by Kheirouri, 2019 [

83] on the dietary inflammatory potential and risk of neurodegenerative diseases concluded that the DII may be correlated with circulating inflammatory marker levels. This confirms the DII as an appropriate tool to measure the inflammatory potential of a diet. The role of diets with an inflammatory potential was validated in the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases [

83,

84]

Rad SR-MA, 2024 findings about DII and MS/ demyelinating autoimmune diseases suggest a proinflammatory diet may increase the odds of developing these pathologies. An association between higher DII scores with the likelihood of developing MS was found [

85].

Mirhosseini SR (2023) findings suggest the anti-inflammatory diet as measured by lower DII scores was associated with a better gut microbiome profile and variations in the composition and variety of the microbiome [

86].

The DII of the diets is not usually known in diet studies. In addition, only 3 of the 8 meta-analyses reviewed, which compare potentially anti-inflammatory diets, show inflammatory biomarkers. The reduction in inflammatory biomarker levels is not clear in the meta-analyses.

4.4. Restriction of Common Components in Many Diets

A systematic review by Lerner et al., with very low levels of evidence, concluded that a gluten-free diet (GFD) could be useful for treating non-gluten-dependent ADs, reducing symptoms in many patients, and suppressing harmful intraluminal intestinal events [

87]. Patients with rheumatic diseases present gluten sensitivity more frequently than the general population. Some RCTs included in the meta-analyses studied modified Mediterranean diets with gluten reduction [

62].

An association between psoriasis, celiac disease, and celiac disease markers has previously been identified. According to preliminary studies, a GFD may benefit some patients with psoriasis [

88,

89].

A low FODMAP diet can be considered an anti-inflammatory diet because it includes the withdrawal of inflammatory potential foods, such as fructose (sugar), sorbitol or mannitol (derived from sugar), lactose (dairy), fructans (wheat, rye, and oats), and galactans (chickpeas, rye, and oats). Likewise, wheat contains fructans (FODMAPs), and the GFD has fewer FODMAPs.

Two of the analyzed meta-analyses [

67,

68] demonstrated that introducing a low FODMAP diet effectively treated FGSs in patients with IBD. One study demonstrated improvements in the QoL of patients with IBD [

68]. However, after symptom improvement with a low FODMAP diet, the diet should be modified because it eliminates some prebiotics, which can damage the IM [

90].

Moreover, continuously being on a GFD can cause deficiencies in minerals, vitamins, and fiber. Foods manufactured without gluten are usually rich in salt, fat, and sugar; this composition can contribute to inflammation through modification of the IM. Currently, designing an individualized diet is proposed as a strategy to modulate the composition of the IM [

91]. Therefore, diets must be supervised by a nutrition specialist.

CDED, specifically designed for CD patients, is a whole food diet combined with PEN and excluding processed foods, emulsifiers, animal fat, red and processed meat, carrageenan, gluten, and dairy products among others [

79,

92]. Due to its composition, we could consider the CDED as an anti-inflammatory diet, confirming our findings.

To normalize the classification of anti-inflammatory diets based on the DII, E-DII, o another consensus index, would be interesting to improve research quality.

5. Conclusions

Reduced pain, fatigue, and quality of life were observed in the IMIDs studied, with critically low, or low levels of evidence.

This review updates the global dietary evidence to improve IMID symptoms, discusses the influences of dietary mechanisms, clarifies the weaknesses of clinical trials and dietary meta-analyses, with critically low levels of evidence, and shows the need to use indexes such us DII, that allow diets to be classified for their content of pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory foods, to better compare diet groups in clinical trials. The difficulty in obtaining high-level evidence in dietary studies is apparent, which may delay the application of the results.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Supplementary Table S1. Search strategy MEDLINE and EMBASE.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: MD.G.A and MD.V.G; methodology: MD.G.A, MD.V.G; investigation: MDGA, MDVG, BHC, MBG; formal analysis: MDGA, BHC; validation: MDGA, BHC; writing – original draft: MDGA; visualization, and Supervision: MDGA; writing – review & editing: MDGA, MDVG, BFC, MBG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our hospital for supporting this study and Úrsula Feore Callanan for the English review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

Autoimmune disease AD, immune-mediated inflammatory disease IMID, Western diet (WD), inflammatory bowel diseases IBD, rheumatoid arthritis RA, intestinal microbiota IM, T-lymphocytes T-CELLS, multiple sclerosis MS, intestinal barrier IB, α-amylase/trypsin inhibitors ATI, human leukocyte antigen HLA, Axial Spondyloarthritis SpA, systemic lupus erythematosus SLE, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses PRISMA, Expanded Disability Status Scale EDSS, Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life MSQoL, Modified Fatigue Impact Scale MFIS, Clinical disease activity index CDAI, erythrocyte sedimentation rate ESR, Fecal Calprotectin FC, C-Reactive Protein CRP, Albumin ALB, functional gastrointestinal symptoms FGSs, quality of Life QoL, short IBD questionnaire SIBDQ, disease activity score DAS, Standardized mean differences SMD, , osteoarthritis OA, immunoglobulin exclusion diet IGED, fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols FODMAP, Low FODMAP diet LFD, Specific carbohydrate diets SCD, Dietary inflammatory index DII, tumor necrosis factor TNF, Gluten-Free Diet GFD, Low-density lipoproteins LDL.

References

- Miller, Frederick W. “The Increasing Prevalence of Autoimmunity and Autoimmune Diseases: An Urgent Call to Action for Improved Understanding, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention.” Current Opinion in Immunology, vol. 80, Feb. 2023, p. 102266. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Mazzucca, Camilla Barbero et al. “How to Tackle the Relationship between Autoimmune Diseases and Diet: Well Begun Is Half-Done.” Nutrients vol. 13,11 3956. 5 Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Samuels, Hadas, et al. “Autoimmune Disease Classification Based on PubMed Text Mining.” Journal of Clinical Medicine vol. 11,15 4345. 26 Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, G., Moscardelli, A., Colella, A., Marafini, I., & Salvatori, S. (2023). Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: Common and different pathogenic and clinical features. Autoimmunity reviews, 22(10), 103410. [CrossRef]

- Christ, Anette, et al. “Western Diet and the Immune System: An Inflammatory Connection.” Immunity vol. 51,5 (2019): 794-811. [CrossRef]

- Nezamoleslami, Shokufeh, et al. “The relationship between dietary patterns and rheumatoid arthritis: a case-control study.” Nutrition & metabolism vol. 17 75. 17 Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Li, Tong, et al. “Systematic review and meta-analysis: Association of a pre-illness Western dietary pattern with the risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease.” Journal of digestive diseases vol. 21,7 (2020): 362-371. [CrossRef]

- Zitvogel, Laurence, and Guido Kroemer. “Immunostimulatory gut bacteria.” Science (New York, N.Y.) vol. 366,6469 (2019): 1077-1078. [CrossRef]

- Meade, Susanna, et al. “Gut Microbiome-Associated Predictors as Biomarkers of Response to Advanced Therapies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review.” Gut Microbes, vol. 15, no. 2, Dec. 2023. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Ting et al. “Gut microbiota and rheumatoid arthritis: From pathogenesis to novel therapeutic opportunities.” Frontiers in immunology vol. 13 1007165. 8 Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mousa, Walaa K et al. “Microbial dysbiosis in the gut drives systemic autoimmune diseases.” Frontiers in immunology vol. 13 906258. 20 Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sorboni, Shokufeh Ghasemian et al. “A Comprehensive Review on the Role of the Gut Microbiome in Human Neurological Disorders.” Clinical microbiology reviews vol. 35,1 (2022): e0033820. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ping. “Influence of Foods and Nutrition on the Gut Microbiome and Implications for Intestinal Health.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 23, no. 17, Aug. 2022, p. 9588. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Arroyo Hornero, R. , Hamad, I., Côrte-Real, B., Kleinewietfeld, M., 2020. The Impact of Dietary Components on Regulatory T-cells and Disease. Front. Immunol. 11, 253. [CrossRef]

- Bäcklund, Reecka, et al. “Diet and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis - A systematic literature review.” Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism vol. 58 (2023): 152118. [CrossRef]

- Khademi, Zeinab, et al. “Dietary Intake of Total Carbohydrates, Sugar and Sugar-Sweetened Beverages, and Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies.” Frontiers in Nutrition, vol. 8, Oct. 2021. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Bolte, Laura A., et al. “Long-Term Dietary Patterns Are Associated with pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Features of the Gut Microbiome.” Gut, vol. 70, no. 7, Apr. 2021, pp. 1287–98. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Rastall, R. A., et al. “Structure and Function of Non-Digestible Carbohydrates in the Gut Microbiome.” Beneficial Microbes, vol. 13, no. 2, June 2022, pp. 95–168. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Serrano Fernandez, Victor, et al. “High-Fiber Diet and Crohn’s Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 14, July 2023, p. 3114. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Mallon, K. , et al. “P862 Dietary Risk Factors Associated with Onset of IBD: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis, vol. 17, no. Supplement_1, Jan. 2023, pp. i985–86. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar, Carlijn A et al. “The Effect of Dietary Interventions on Chronic Inflammatory Diseases in Relation to the Microbiome: A Systematic Review.” Nutrients vol. 13,9 3208. 15 Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J. E. , and A. J. Silman. “Risk Factors for the Development of Rheumatoid Arthritis.” Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology, vol. 35, no. 3, Jan. 2006, pp. 169–74. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Graff, Erica, et al. “Dietary Intake and Systemic Inflammation: Can We Use Food as Medicine?”. Current nutrition reports, 10.1007/s13668-023-00458-z. 20 Jan. 2023.

- García-Montero, Cielo et al. “Nutritional Components in Western Diet Versus Mediterranean Diet at the Gut Microbiota-Immune System Interplay. Implications for Health and Disease.” Nutrients vol. 13,2 699. 22 Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Yawei et al. “Associations among Dietary Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, the Gut Microbiota, and Intestinal Immunity.” Mediators of inflammation vol. 2021 8879227. 2 Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gowen, Rachael et al. “Modulating the Microbiome for Crohn's Disease Treatment.” Gastroenterology vol. 164,5 (2023): 828-840. [CrossRef]

- Camara-Lemarroy, C.R. , Metz, L., Meddings, J.B., Sharkey, K.A., Wee Yong, V., 2018. The intestinal barrier in multiple sclerosis: Implications for pathophysiology and therapeutics. Brain 141, 1900–1916. [CrossRef]

- Mu, Qinghui, et al. “Leaky Gut As a Danger Signal for Autoimmune Diseases.” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 8, May 2017. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Jiang S, Miao Z. High-fat diet induces intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction in ulcerative colitis: emerging mechanisms and dietary intervention perspective. Am J Transl Res. 2023 Feb 15;15(2):653-677. [PubMed]

- de Punder K, Pruimboom L. The dietary intake of wheat and other cereal grains and their role in inflammation. Nutrients. 2013 Mar 12;5(3):771-87. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang X, Schuppan D, Rojas Tovar LE, Zevallos VF, Loponen J, Gänzle M. Sourdough Fermentation Degrades Wheat Alpha-Amylase/Trypsin Inhibitor (ATI) and Reduces Pro-Inflammatory Activity. Foods. 2020 Jul 16;9(7):943. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, S. , Bonavita, S., Sparaco, M., Gallo, A., & Tedeschi, G. (2018). The role of diet in multiple sclerosis: A review. Nutritional neuroscience, 21(6), 377–390. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, Muhammad et al. “Dietary Component-Induced Inflammation and Its Amelioration by Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Synbiotics.” Frontiers in nutrition vol. 9 931458. 22 Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gershteyn, Iosif M., et al. “Immunodietica: Interrogating the Role of Diet in Autoimmune Disease.” International Immunology, vol. 32, no. 12, Aug. 2020, pp. 771–83. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Wenjing, and Yingzi Cong. “Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in the Regulation of Host Immune Responses and Immune-Related Inflammatory Diseases.” Cellular & Molecular Immunology, vol. 18, no. 4, Mar. 2021, pp. 866–77. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Shivappa, Nitin, et al. “Designing and Developing a Literature-Derived, Population-Based Dietary Inflammatory Index.” Public Health Nutrition, vol. 17, no. 8, Aug. 2013, pp. 1689–96. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Hébert JR, Shivappa N, Wirth MD, Hussey JR, Hurley TG. Perspective: The Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII)-Lessons Learned, Improvements Made, and Future Directions. Adv Nutr. 2019 Mar 1;10(2):185-195. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiat VR, Reis G, Valera IC, Parvatiyar K, Parvatiyar MS. Autoimmunity as a sequela to obesity and systemic inflammation. Front Physiol. 2022 Nov 21;13:887702. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, S.N. , Fitzgerald, K.C., Beier, M., Mowry, E.M., 2020. Safety and feasibility of various fasting-mimicking diets among people with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 42, 102149. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Ding, et al. “Lifestyle Factors Associated with Incidence of Rheumatoid Arthritis in US Adults: Analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Database and Meta-Analysis.” BMJ Open, vol. 11, no. 1, Jan. 2021, p. e038137. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Ortolan, Augusta, et al. “Do Obesity and Overweight Influence Disease Activity Measures in Axial Spondyloarthritis? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Arthritis care & research vol. 73,12 (2021): 1815-1825. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yang et al. “Impact of Obesity on Remission and Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Arthritis care & research vol. 69,2 (2017): 157-165. [CrossRef]

- Moroni L, Farina N, Dagna L. Obesity and its role in the management of rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2020 Apr;39(4):1039-1047. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortolan, Augusta, et al. “The Impact of Diet on Disease Activity in Spondyloarthritis: A Systematic Literature Review.” Joint Bone Spine, vol. 90, no. 2, Mar. 2023, p. 105476. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Upala, S. , and A. Sanguankeo. “Effect of Lifestyle Weight Loss Intervention on Disease Severity in Patients with Psoriasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Obesity, vol. 39, no. 8, Apr. 2015, pp. 1197–202. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Caputo, Marina, et al. “Targeting Microbiota in Dietary Obesity Management: A Systematic Review on Randomized Control Trials in Adults.” Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, June 2022, pp. 1–33. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- “Index”. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, pp. 633–49. Crossref.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Kurtzke, JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983 Nov;33(11):1444-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, Jeffrey A., et al. “Disability Outcome Measures in Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Trials: Current Status and Future Prospects.” The Lancet Neurology, vol. 11, no. 5, May 2012, pp. 467–76. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Vickrey, B. G., et al. “A Health-Related Quality of Life Measure for Multiple Sclerosis.” Quality of Life Research, vol. 4, no. 3, June 1995, pp. 187–206. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Fisk, John D., et al. “Measuring the Functional Impact of Fatigue: Initial Validation of the Fatigue Impact Scale.” Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 18, no. Supplement_1, Jan. 1994, pp. S79–83. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R F, and J M Bradshaw. “A simple index of Crohn's-disease activity.” Lancet (London, England) vol. 1,8167 (1980): 514. [CrossRef]

- Prevoo ML, van 't Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(1):44–8. 10.1002/art.1780380107.

- Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 1977. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Cuncun, et al. “Use of AMSTAR-2 in the methodological assessment of systematic reviews: protocol for a methodological study.” Annals of Translational Medicine vol. 8,10 (2020): 652. [CrossRef]

- Gwinnutt, James M., et al. “Effects of Diet on the Outcomes of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases (RMDs): Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses Informing the 2021 EULAR Recommendations for Lifestyle Improvements in People with RMDs.” RMD Open, vol. 8, no. 2, June 2022, p. e002167. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Cramp, Fiona, et al. “Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Aug. 2013. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Limketkai, Berkeley N., et al. “Dietary Interventions for Induction and Maintenance of Remission in Inflammatory Bowel Disease.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Feb. 2019. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Limketkai, Berkeley N., et al. “Dietary Interventions for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Dec. 2022. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Parks, Natalie E., et al. “Dietary Interventions for Multiple Sclerosis-Related Outcomes.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, vol. 2020, no. 5, May 2020. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Schönenberger, Katja A., et al. “Effect of Anti-Inflammatory Diets on Pain in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 12, Nov. 2021, p. 4221. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Genel, Furkan, et al. “Health Effects of a Low-Inflammatory Diet in Adults with Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Nutritional Science, vol. 9, 2020. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Turk, Matthew A et al. “Non-pharmacological interventions in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Autoimmunity reviews vol. 22,6 (2023): 103323. [CrossRef]

- Ortolan, Augusta, et al. “Efficacy and Safety of Non-Pharmacological and Non-Biological Interventions: A Systematic Literature Review Informing the 2022 Update of the ASAS/EULAR Recommendations for the Management of Axial Spondyloarthritis.” Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, vol. 82, no. 1, Oct. 2022, pp. 142–52. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Comeche, José M., et al. “Predefined Diets in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 1, Dec. 2020, p. 52. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Yong-le, et al. “Is a Low FODMAP Diet Beneficial for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease? A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review.” Clinical Nutrition, vol. 37, no. 1, Feb. 2018, pp. 123–29. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Ziheng, et al. “A Low-FODMAP Diet Provides Benefits for Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms but Not for Improving Stool Consistency and Mucosal Inflammation in IBD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Nutrients, vol. 14, no. 10, May 2022, p. 2072. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero Aznar, María Dolores et al. “Efficacy of diet on fatigue, quality of life and disability status in multiple sclerosis patients: rapid review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” BMC neurology vol. 22,1 388. 20 Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bohlouli, Jalal, et al. “Modified Mediterranean Diet v. Traditional Iranian Diet: Efficacy of Dietary Interventions on Dietary Inflammatory Index Score, Fatigue Severity and Disability in Multiple Sclerosis Patients.” British Journal of Nutrition, Aug. 2021, pp. 1–11. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Snetselaar, Linda, et al. “Efficacy of Diet on Fatigue and Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials.” Neurology, Oct. 2022, p. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000201371. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Ford, Adam R., et al. “Dietary Recommendations for Adults With Psoriasis or Psoriatic Arthritis From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation.” JAMA Dermatology, vol. 154, no. 8, Aug. 2018, p. 934. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Gill, Paul A., et al. “The Role of Diet and Gut Microbiota in Regulating Gastrointestinal and Inflammatory Disease.” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 13, Apr. 2022. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Bradley C., et al. “The Philosophy of Evidence-Based Principles and Practice in Nutrition.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes, vol. 3, no. 2, June 2019, pp. 189–99. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Josefine et al. “Do Interventions with Diet or Dietary Supplements Reduce the Disease Activity Score in Rheumatoid Arthritis? A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Nutrients vol. 12,10 2991. 29 Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lomer MCE, Wilson B, Wall CL. British Dietetic Association consensus guidelines on the nutritional assessment and dietary management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2023 Feb;36(1):336-377. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Zhanhui, et al. “Effects of Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet on Remission: A Systematic Review.” Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology, vol. 16, Jan. 2023. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Bager, P.; Escher, J.; Forbes, A.; Hébuterne, X.; Hvas, C.L.; Joly, F.; Klek, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Ockenga, J.; et al. ESPEN guideline on Clinical Nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 352–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, Inês et al. “Is There Evidence of Crohn's Disease Exclusion Diet (CDED) in Remission of Active Disease in Children and Adults? A Systematic Review.” Nutrients vol. 16,7 987. 28 Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Herrador-López, Marta, et al. “Dietary Interventions in Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review of the Evidence with Meta-Analysis.” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 19, Sept. 2023, p. 4194. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Weissman, Simcha, et al. “The Overall Quality of Evidence of Recommendations Surrounding Nutrition and Diet in Inflammatory Bowel Disease.” International Journal of Colorectal Disease, vol. 38, no. 1, Apr. 2023. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Chiba M, Hosoba M, Yamada K. Plant-Based Diet Recommended for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023 May 2;29(5):e17-e18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheirouri, Sorayya, and Mohammad Alizadeh. “Dietary Inflammatory Potential and the Risk of Neurodegenerative Diseases in Adults.” Epidemiologic Reviews, vol. 41, no. 1, 2019, pp. 109–20. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Hajianfar, Hossein, et al. “Association between Dietary Inflammatory Index and Risk of Demyelinating Autoimmune Diseases.” International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research, Mar. 2022. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Rad, Esmaeil Yousefi et al. “A systematic review and meta-analysis of Dietary Inflammatory Index and the likelihood of multiple sclerosis/ demyelinating autoimmune disease.” Clinical nutrition ESPEN vol. 62 (2024): 108-114. [CrossRef]

- Mirhosseini, Seyed Mohsen et al. “What is the link between the dietary inflammatory index and the gut microbiome? A systematic review.” European journal of nutrition, 10.1007/s00394-024-03470-3. 28 Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Aaron, et al. “Gluten-Free Diet Can Ameliorate the Symptoms of Non-Celiac Autoimmune Diseases.” Nutrition Reviews, vol. 80, no. 3, Aug. 2021, pp. 525–43. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, Bhavnit K., et al. “Diet and Psoriasis, Part II: Celiac Disease and Role of a Gluten-Free Diet.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, vol. 71, no. 2, Aug. 2014, pp. 350–58. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Bell, Katheryn A., et al. “The Effect of Gluten on Skin and Hair: A Systematic Review.” Dermatology Online Journal, vol. 27, no. 4, 2021. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, Walburga, and Yurdagül Zopf. “Gluten and FODMAPS—Sense of a Restriction/When Is Restriction Necessary?” Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 8, Aug. 2019, p. 1957. Crossref. [CrossRef]

- Cenni S, Sesenna V, Boiardi G, Casertano M, Russo G, Reginelli A, Esposito S, Strisciuglio C. The Role of Gluten in Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Review. Nutrients. 2023 Mar 27;15(7):1615. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Zhanhui et al. “Effects of Crohn's disease exclusion diet on remission: a systematic review.” Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology vol. 16 17562848231184056. 30 Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).