Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Trial Design

2.2. Participants

- Being diagnosed with RA by a rheumatologist and starting disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment.

- RA disease duration longer than 1 year

- Age range 18-65 years

- Body Mass Index (BMI)=18.5-40 kg/m 2

- Smoking three and less than three cigarettes a day

- Diabetes, cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, kidney and liver disease, psychiatric disorders

- Use biological drugs, regular users of Non Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), oral cortisol intake >12.5mg.

- Those who have used a special diet, herbal supplements, vitamin-mineral supplements (except D vit.), probiotics in the last 3 months

- Those who received antibiotic treatment in the last 3 months

- Pregnant or lactating women

- Patients were included in the study on a voluntary basis and signed an informed consent form.

2.3. Dietary Intervention

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Anthropometric Measurements

2.4.2. Disease Activity

2.4.3. Biochemical Parameters

2.4.4. Fecal Sampling and 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene Sequencing

2.4.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.4.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Anthropometric Measurements

3.2. Biochemical Parameters

3.3. Disease Activity

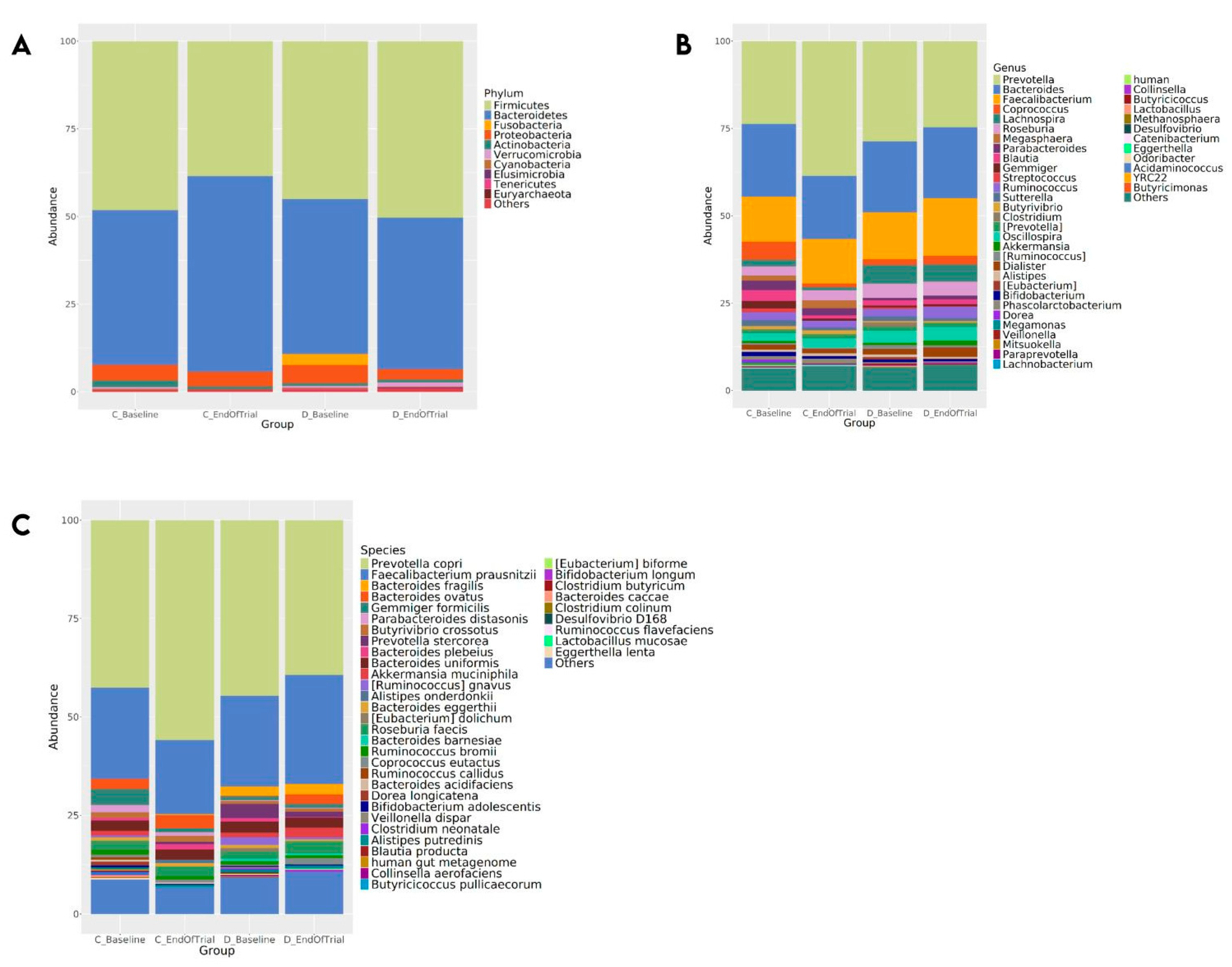

3.4. Fecal Microbiota Composition

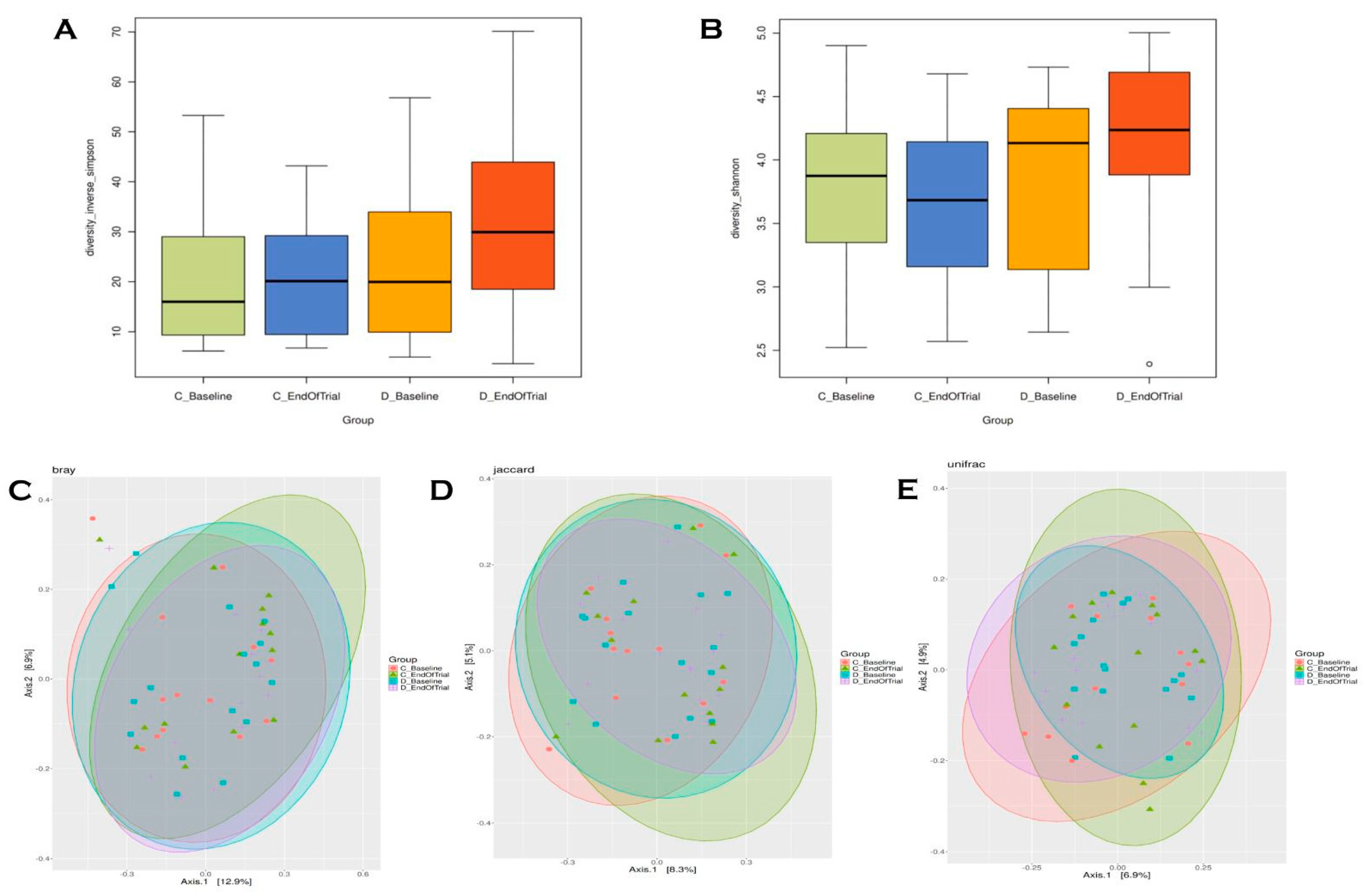

3.5. Alpha and Beta Diversity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RA | Romatoid Artrit |

| Th17 | T helper 17 |

| SCFA | Short-Chain Fatty Acid |

| DAS28-ESR | Disease Activity Score-28 Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate |

| DAS28-CR | Disease Activity Score-28-C Reactive Protein |

| SDAI | Simple Disease Activity Index |

| EULAR | European League Against Rheumatism |

| ACR | American College of Rheumatology |

| DMARD | Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drug |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| NSAIDs | Non Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs |

| BIA | Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis |

| AETD | American Association of Hand Therapists |

| FPG | Fasting plasma glucose |

| LDL | Low Density Lipoprotein |

| HDL | High Density Lipoprotein |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| DNA | Deoksiribo Nükleik Asit |

| dsDNA | double-stranded Deoksiribo Nükleik Asit |

| rRNA | ribosomal Ribo Nükleik Asit |

| ASV | Amplicon Sequence Variants |

| MAC | Microbiota-Accessible Carbohydrates |

References

- Choy, E. Understanding the dynamics: pathways involved in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2012, 51, v3–v11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venetsanopoulou, A.I.; Alamanos, Y.; Voulgari, P.V.; Drosos, A.A. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Rheumatoid Arthritis Development. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2023, 34, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, S.K.; Frits, M.; Cui, J.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Mahmoud, T.; Iannaccone, C.; Lin, T.; Yoshida, K.; Weinblatt, M.E.; Shadick, N.A.; et al. Diet and Rheumatoid Arthritis Symptoms: Survey Results From a Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry. Arthritis Care Res. 2017, 69, 1920–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, I.B.; Schett, G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2011, 365, 2205–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemao, C.A.; Budden, K.F.; Gomez, H.M.; Rehman, S.F.; Marshall, J.E.; Shukla, S.D.; Donovan, C.; Forster, S.C.; Yang, I.A.; Keely, S.; et al. Impact of diet and the bacterial microbiome on the mucous barrier and immune disorders. Allergy 2020, 76, 714–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Castillo, Z.; Valdés-Miramontes, E.; Llamas-Covarrubias, M.; Muñoz-Valle, J.F. Troublesome friends within us: the role of gut microbiota on rheumatoid arthritis etiopathogenesis and its clinical and therapeutic relevance. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.J.; Ivanov, I.I.; Darce, J; Hattori, K.; Shima, T.; Umesaki, Y.; Littman, D.R.; Benoist, C.; Mathis, D. Gut-residing segmented filamentous bacteria drive autoimmune arthritis via T helper 17 cells. Immunity 201, 32, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam-Ndoul, B.; Castonguay-Paradis, S.; Veilleux, A. Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Trans-Epithelial Permeability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Wright K, Davis JM, Jeraldo P, Marietta EV, Murray J, Nelson H, Matteson EL, Taneja V. An expansion of rare lineage intestinal microbes characterises rheumatoid arthritis. Genome Med 2016, 8, 43. [CrossRef]

- Wells, P.M.; Adebayo, A.S.; E Bowyer, R.C.; Freidin, M.B.; Finckh, A.; Strowig, T.; Lesker, T.R.; Alpizar-Rodriguez, D.; Gilbert, B.; Kirkham, B.; et al. Associations between gut microbiota and genetic risk for rheumatoid arthritis in the absence of disease: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020, 2, e418–e427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondanelli, M.; Perdoni, F.; Peroni, G.; Caporali, R.; Gasparri, C.; Riva, A.; Petrangolini, G.; Faliva, M.A.; Infantino, V.; Naso, M.; et al. Ideal food pyramid for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A narrative review. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 40, 661–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh RK, Chang HW, Yan D, Lee KM, Ucmak D, Wong K, Abrouk M, Farahnik B, Nakamura M, Zhu TH, Bhutani T and Liao W. Infuence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J Transl Med 2017, 15, 73.

- Illiano, P.; Brambilla, R.; Parolini, C. The mutual interplay of gut microbiota, diet and human disease. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 833–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes-Bayir, A.; Mendes, B.; Dadak, A. The Integral Role of Diets Including Natural Products to Manage Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Narrative Review. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 5373–5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalsen, A.; Riegert, M.; Lüdtke, R.; Bäcker, M.; Langhorst, J.; Schwickert, M.; Dobos, G.J. Mediterranean diet or extended fasting's influence on changing the intestinal microflora, immunoglobulin A secretion and clinical outcome in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia: an observational study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2005, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, B.; Johansson, I.; Rantapää-Dahlqvist, S. Diet and alcohol as risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis: a nested case–control study. Rheumatol. Int. 2014, 35, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, O Bingham C 3rd, Birnbaum NS, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, Cohen MD, Combe B, Costenbader KH, Dougados M, Emery P, Ferraccioli G, Hazes JMW, Hobbs K, Huizinga TWJ, Kavanaugh A, Kay J, Kvien TK, Laing T, Mease P, Ménard HA, Moreland LW, Naden RL, T, Pincus T, Smolen JS, Stanislawska-Biernat E, Symmons D, Tak PP, Upchurch KS, Vencovsky J, Wolfe F, Hawker G. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: An american college of rheumatology/european league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2010, 69, 1580–1588.

- Lam, N.; Goh, H.; Kamaruzzaman, S.; Chin, A.; Poi, P.; Tan, M. Normative data for hand grip strength and key pinch strength, stratified by age and gender for a multiethnic Asian population. Singap. Med J. 2016, 57, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riel PLCM. The development of the disease activity score (DAS) and the disease activity score using 28 joint counts (DAS28). Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014, 32, S-65-74.

- Aletaha, D.; Ward, M.M.; Machold, K.P.; Nell, V.P.K.; Stamm, T.; Smolen, J.S. Remission and active disease in rheumatoid arthritis: Defining criteria for disease activity states. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 2625–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Huntley, J.; Fierer, N.; Owens, S.M.; Betley, J.; Fraser, L.; Bauer, M.; et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1621–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; Mcmurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D. Amplicon Sequence Variants Artificially Split Bacterial Genomes into Separate Clusters. mSphere 2021, 6, e0019121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.J.; Koren, O.; Hugenholtz, P.; DeSantis, T.Z.; A Walters, W.; Caporaso, J.G.; Angenent, L.T.; Knight, R.; E Ley, R. Impact of training sets on classification of high-throughput bacterial 16s rRNA gene surveys. ISME J. 2011, 6, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffi, J.-M.N.; Koffi, K.K.; Bonny, S.B.; Bi, A.I.Z. Genetic Diversity of Taro Landraces from Côte d’Ivoire Based on Qualitative Traits of Leaves. Agric. Sci. 2021, 12, 1433–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, William H, and W. Allen Wallis. "Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis.". Journal of the American statistical Association 1952, 47, 583–621. [CrossRef]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550.

- Philippou, E.; Nikiphorou, E. Are we really what we eat? Nutrition and its role in the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018, 17, 1074–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäcklund, R.; Drake, I.; Bergström, U.; Compagno, M.; Sonestedt, E.; Turesson, C. Diet and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis – A systematic literature review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2022, 58, 152118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picchianti-Diamanti, A.; Panebianco, C.; Salemi, S.; Sorgi, M.L.; Di Rosa, R.; Tropea, A.; Sgrulletti, M.; Salerno, G.; Terracciano, F.; D’amelio, R.; et al. Analysis of Gut Microbiota in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: Disease-Related Dysbiosis and Modifications Induced by Etanercept. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From Dietary Fibre to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [CrossRef]

- Merra G, Noce A, Marrone G, Cintoni M, Tarsitano MG, Capacci A De Lorenzo A. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2020, 13, 7.

- Deiana, M.; Serra, G.; Corona, G. Modulation of intestinal epithelium homeostasis by extra virgin olive oil phenolic compounds. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 4085–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliannan, K.; Wang, B.; Li, X.-Y.; Kim, K.-J.; Kang, J.X. A host-microbiome interaction mediates the opposing effects of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids on metabolic endotoxemia. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishikawa, T.; Maeda, Y.; Nii, T.; Motooka, D.; Matsumoto, Y.; Matsushita, M.; Matsuoka, H.; Yoshimura, M.; Kawada, S.; Teshigawara, S.; et al. Metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiome revealed novel aetiology of rheumatoid arthritis in the Japanese population. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Kurakawa, T.; Umemoto, E.; Motooka, D.; Ito, Y.; Gotoh, K.; Hirota, K.; Matsushita, M.; Furuta, Y.; Narazaki, M.; et al. Dysbiosis Contributes to Arthritis Development via Activation of Autoreactive T Cells in the Intestine. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016, 68, 2646–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert JA, Bemis EA, Ramsden K, et al. Association of antibodies to Prevotella copri in anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide-positive individuals at risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis and in patientswith early or established rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2023, 75, 507–516. [CrossRef]

- Arvonen, M.; Berntson, L.; Pokka, T.; Karttunen, T.J.; Vähäsalo, P.; Stoll, M.L. Gut microbiota-host interactions and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2016, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou L, Zhang M, Wang Y, Dorfman RG, Liu H, Yu T, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii produces butyrate to maintain Th17/Treg balance and to ameliorate colourectal colitis by inhibiting histone deacetylase Inflammation Bowel Dis 2018, 24, 1926–40.

- Moon, J.; Lee, A.R.; Kim, H.; Jhun, J.; Lee, S.-Y.; Choi, J.W.; Jeong, Y.; Park, M.S.; Ji, G.E.; Cho, M.-L.; et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii alleviates inflammatory arthritis and regulates IL-17 production, short chain fatty acids, and the intestinal microbial flora in experimental mouse model for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2023, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; et al. The oral and gut microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partially normalised after treatment. Nat Med 2015, 21, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltonen, R.; Kjeldsen-Kragh, J.; Haugen, M.; Tuominen, J.; Toivanen, P.; Førre, Ø.; Eerola, E. CHANGES OF FAECAL FLORA IN RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS DURING FASTING AND ONE-YEAR VEGETARIAN DIET. Rheumatology 1994, 33, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalsen, A.; Riegert, M.; Lüdtke, R.; Bäcker, M.; Langhorst, J.; Schwickert, M.; Dobos, G.J. Mediterranean diet or extended fasting's influence on changing the intestinal microflora, immunoglobulin A secretion and clinical outcome in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia: an observational study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2005, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti, A.P.; Panebianco, C.; Salerno, G.; Di Rosa, R.; Salemi, S.; Sorgi, M.L.; Meneguzzi, G.; Mariani, M.B.; Rai, A.; Iacono, D.; et al. Impact of Mediterranean Diet on Disease Activity and Gut Microbiota Composition of Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Control (n=14) |

Diet (n=16) |

Total (n=30) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 53.71±7.36 | 49.25±10.44 | 51.33±9.26 | 0.193 |

| Sex | 1.000 | |||

| Female | 12 (%85.7) | 14 (%87.5) | 26 (%86.7) | |

| Male | 2 (%14.3) | 2 (%12.5) | 4 (%13.3) | |

| Place of residence | 1.000 | |||

| Urban | 13 (%92.9) | 15 (%3.8) | 28 (%93.3) | |

| Rural | 1 (%7.1) | 1 (%6.3) | 2 (%6.7) | |

| Marital status | 0.814 | |||

| Married | 11 (%78.6) | 13 (%81.3) | 24 (%80.0) | |

| Single | 0 (%0) | 1 (%6.3) | 1 (%3.3) | |

| 3 (%21.4) | 2 (%12.5) | 5 (%16.7) | ||

| Level of education | 0.200 | |||

| Primary School | 7 (%50.0) | 8 (%50.0) | 15 (%50.0) | |

| Middle School | 3 (%21.4) | 0 (%0) | 3 (%10.0) | |

| High School | 4 (%28.6) | 6 (%37.5) | 10(%33.3) | |

| University | 0 (%0) | 2 (%12.5) | 2 (%6.7) | |

| Employment | 0.814 | |||

| Housewife | 11 (%78.6) | 13 (%81.3) | 24 (%80.0) | |

| Full-time job | 2 (%14.3) | 3 (%18.8) | 5 (%16.7) | |

| Retired | 1 (%7.1) | 0 (%0) | 1 (%3.3) | |

| Socioeconomic status | 0.840 | |||

| Low | 5 (%35.7) | 4 (%25.0) | 9 (%30.0) | |

| Medium | 9 (%64.3) | 11 (%68.8) | 20 (%66.7) | |

| High | 0 (%0) | 1 (%6.3) | 1 (%3.3) | |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Vaginal birth | 14 (%100.0) | 16 (%100.0) | 30 (%100.0) | |

| Caesarean section | 0 (%0) | 0 (%0) | 0 (%0) | |

| Duration of breastfeeding (months) | 8.00±9.98 | 13.40±7.72 | 11.38±8.73 | |

| Physical activity | 0.440 | |||

| Inactive | 11 (%78.6) | 10 (%62.5) | 21 (%70.0) | |

| Minimal active | 3 (%21.4) | 6 (%37.5) | 9 (%30.0) | |

| Active | 0 (%0) | 0 (%0) | 0 (%0) | |

| Gingivitis | 1 (%7.1) | 2 (%12.5) | 3 (%10.0) | 1.000 |

| RA Disease Duration (Years) | 13.21±6.69 | 11.56±8.49 | 12.33±7.62 | 0.563 |

| Sleep duration (hours) | 6.57±1.28 | 7.13±1.26 | 6.87±1.28 | 0.244 |

| Parameters | Control (n=14) |

Diet (n=16) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) | |||

| Baseline | 79.75±12.80 | 75.26±13.52 | |

| End of trial | 80.96±13.14 | 73.81±13.49 | |

| p‡ | 0.009 | 0.020 | |

| Change | -1.20±1.46 | 1.45±2.22 | 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Baseline | 31.44±6.06 | 29.18±4.90 | |

| End of trial | 31.93±6.31 | 28.57±4.69 | |

| p‡ | 0.012 | 0.015 | |

| Change | -0.49±0.62 | 0.61±0.89 | 0.001 |

| Percent fat (%) | |||

| Baseline | 37.04±7.24 | 35.74±7.81 | |

| End of trial | 42.91±10.20 | 33.70±7.99 | |

| p‡ | 0.001 | 0.014 | |

| Change | -5.87±5.31 | 2.04±2.93 | 0.000 |

| Fat mass (kg) | |||

| Baseline | 30.12±9.49 | 27.33±9.87 | |

| End of trial | 35.51±13.08 | 25.48±9.92 | |

| p‡ | 0.003 | 0.008 | |

| Change | -5.39±5.46 | 1.86±2.42 | 0.000 |

| Muscle mass (kg) | |||

| Baseline | 49.65±6.19 | 47.84±6.27 | |

| End of trial | 45.39±6.19 | 48.83±7.21 | |

| p‡ | 0.008 | 0.026 | |

| Change | 4.26±5.12 | -0.99±1.60 | 0.002 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | |||

| Baseline | 105.57±8.34 | 99.75±12.22 | |

| End of trial | 109.71±9.16 | 95.13±10.24 | |

| p‡ | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Change | -4.14±2.35 | 4.63±3.40 | 0.000 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | |||

| Baseline | 119.07±11.45 | 114.63±8.71 | |

| End of trial | 119.93±11.81 | 111.75±8.73 | |

| p‡ | 0.047 | 0.000 | |

| Change | -0.86±1.46 | 2.88±2.39 | 0.000 |

| Waist-Hip ratio | |||

| Baseline | 0.89±0.04 | 0.87±0.07 | |

| End of trial | 0.93±0.05 | 0.85±0.06 | |

| p‡ | 0.010 | 0.031 | |

| Change | -0.14±0.05 | 0.02±0.03 | 0.001 |

| Waist-height ratio | |||

| Baseline | 0.66±0.07 | 0.62±0.08 | |

| End of trial | 0.69±0.08 | 0.59±0.07 | |

| p‡ | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Change | -0.03±0.02 | 0.03±0.02 | |

| Neck circumference (cm) | |||

| Baseline | 37.36±3.56 | 36.44±2.86 | |

| End of trial | 38.0±3.78 | 35.41±3.03 | |

| p‡ | 0.010 | 0.001 | |

| Change | -0.64±0.79 | 1.03±0.96 | 0.000 |

| Wrist circumference (cm) | |||

| Baseline | 17.93±1.77 | 17.19±1.67 | |

| End of trial | 18.43±1.83 | 16.66±1.67 | |

| p‡ | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Change | -0.50±0.44 | 0.53±0.50 | 0.000 |

| Height-Wrist ratio | |||

| Baseline | 9.00±0.99 | 9.41±0.83 | |

| End of trial | 8.75±0.93 | 9.72±0.86 | |

| p‡ | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Change | 0.25±0.21 | -0.30±0.28 | 0.000 |

| Hand grip strength (kg) | |||

| Right hand (kg) | |||

| Baseline | 12.43±4.94 | 19.06±5.74 | |

| End of trial | 9.93±4.05 | 23.13±6.09 | |

| p‡ | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Change | 2.50±1.45 | -4.06±2.72 | 0.000 |

| Left hand (kg) | |||

| Baseline | 13.07±4.80 | 18.25±6.92 | |

| End of trial | 9.79±3.79 | 22.44±6.39 | |

| p‡ | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Change | 3.29±1.98 | -4.19±2.34 | 0.000 |

| Variables | Control (n=14) |

Diet (n=16) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| FPG (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 84.50(76.75-87.00) | 88.00(85.00-96.50) | |

| End of trial | 88.50(81.75-100.0) | 90.00(83.25-94.75) | |

| p‡ | 0.197 | 0.501 | |

| Change | -1.00(-12.50-1.25 | 1.00(-3.00-5.00) | 0.077 |

| CRP (mg/L) | |||

| Baseline | 5.27(2.19-13.33) | 4.39(2.31-7.67) | |

| End of trial | 11.50(4.90-18.57) | 2.16(1.46-3.86) | |

| p‡ | 0.002 | 0.015 | |

| Change | -3.63(-10.28- -1.04) | 1.01(0.03-3.22) | 0.000 |

| ESR (mm/s) | |||

| Baseline | 23.00(9.50-31.00) | 31.00(16.50-51.25) | |

| End of trial | 33.00(13.75-39.50) | 25.00(9.50-39.00) | |

| p‡ | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Change | -4.00(-9.75- -2.50) | 5.00(3.00-8.00) | 0.000 |

| AST (u/L) | |||

| Baseline | 20.00(14.50-21.75) | 18.00(15.00-22.00) | |

| End of trial | 18.00(14.75-24.25) | 20.50(14.00-22.00) | |

| p‡ | 0.728 | 0.362 | |

| Change | -1.00(-3.50-2.25) | -0.50(-3.75-2.00) | 0.918 |

| ALT (u/L) | |||

| Baseline | 17.00(10.25-25.25) | 17.00(12.50-21.00) | |

| End of trial | 16.50(11.50-30.00) | 17.00(11.75-22.75) | |

| p‡ | 0.484 | 0.706 | |

| Change | -0.05(-6.25-3.00) | -0.50(-4.50-3.00) | 0.854 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 4.70(4.38-5.73) | 3.70(3.43-4.18) | |

| End of trial | 4.70(4.15-5.50) | 3.40(2.80-4.45) | |

| p‡ | 0.875 | 0.038 | |

| Change | -0.16(-0.52-0.55) | 0.30(-0.05-0.48) | 0.208 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 0.73(0.65-0.88) | 0.66(0.58-0.76) | |

| End of trial | 0.71(0.63-0.86) | 0.62(0.58-0.73) | |

| p‡ | 0.363 | 0.080 | |

| Change | 0.02(-0.03-0.06) | 0.01(-0.01-0.07) | 0.667 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 125.00(97.00-151.25) | 94.50(76.25-140.25) | |

| End of trial | 144.50(113.75-178.00) | 106.00(83.00-128.50) | |

| p‡ | 0.330 | 0.796 | |

| Change | -9.00(-54.25-24.25) | 8.00(-27.25-18.75) | 0.334 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 116.05(77.38-132.35) | 119.90(92.73-143.55) | |

| End of rial | 124.50(106.60-141.85) | 112.40(98.58-143.80) | |

| p‡ | 0.033 | 0.352 | |

| Change | -22.00(-41.50-10.78) | 5.30(-7.03-16.05) | 0.013 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 55.55(44.60-67.35) | 52.90(46.93-68.03) | |

| End of trial | 54.95(45.30-62.50) | 53.20(46.90-64.70) | |

| p‡ | 0.258 | 0.408 | |

| Change | 2.40(-5.90-8.83) | 0.55(-3.20- 5.08) | 0.951 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 186.50(158.75-214.75) | 198.50(163.75-246.25) | |

| End of trial | 215.50(175.75-232.550) | 197.00(156.00-236.50) | |

| p‡ | 0.011 | 0.255 | |

| Change | -22.50(-41.00- -2.00) | 7.50(-8.25-27.00) | 0.008 |

| Variables | Control (n=14) |

Diet (n=16) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tender joints | |||

| Baseline | 5.57±4.72 | 5.69±4.64 | |

| End of trial | 11.50±6.36 | 1.94±2.74 | |

| p‡ | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Change | -5.93±3.69 | 3.75±2.35 | 0.000 |

| Swollen joints | |||

| Baseline | 0.00(0.00-0.00) | 0.00(0.00-0.00) | |

| End of trial | 0.50(0.00-2.00) | 0.00(0.00-0.00) | |

| p‡ | 0.023 | 0.102 | |

| Change | 0.00(-1.00-0.00) | 0.00(0.00-0.00) | 0.012 |

| DAS28-ESR | |||

| Baseline | 3.59±1.04 | 4.68±1.14 | |

| End of trial | 5.39±0.77 | 3.01±0.92 | |

| p‡ | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Change | -1.80±0.54 | 1.68±0.74 | 0.000 |

| DAS28-CRP | |||

| Baseline | 3.17±0.81 | 3.80±1.04 | |

| End of trial | 4.91±0.51 | 2.15±0.65 | |

| p‡ | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Change | -1.74±0.50 | 1.66±0.73 | 0.000 |

| SDAI | |||

| Baseline | 15.31±8.40 | 20.96±6.93 | |

| End of trial | 29.69±9.05 | 11.18±12.63 | |

| p‡ | 0.000 | 0.008 | |

| Change | -14.39±4.09 | 9.78±12.83 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).