Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

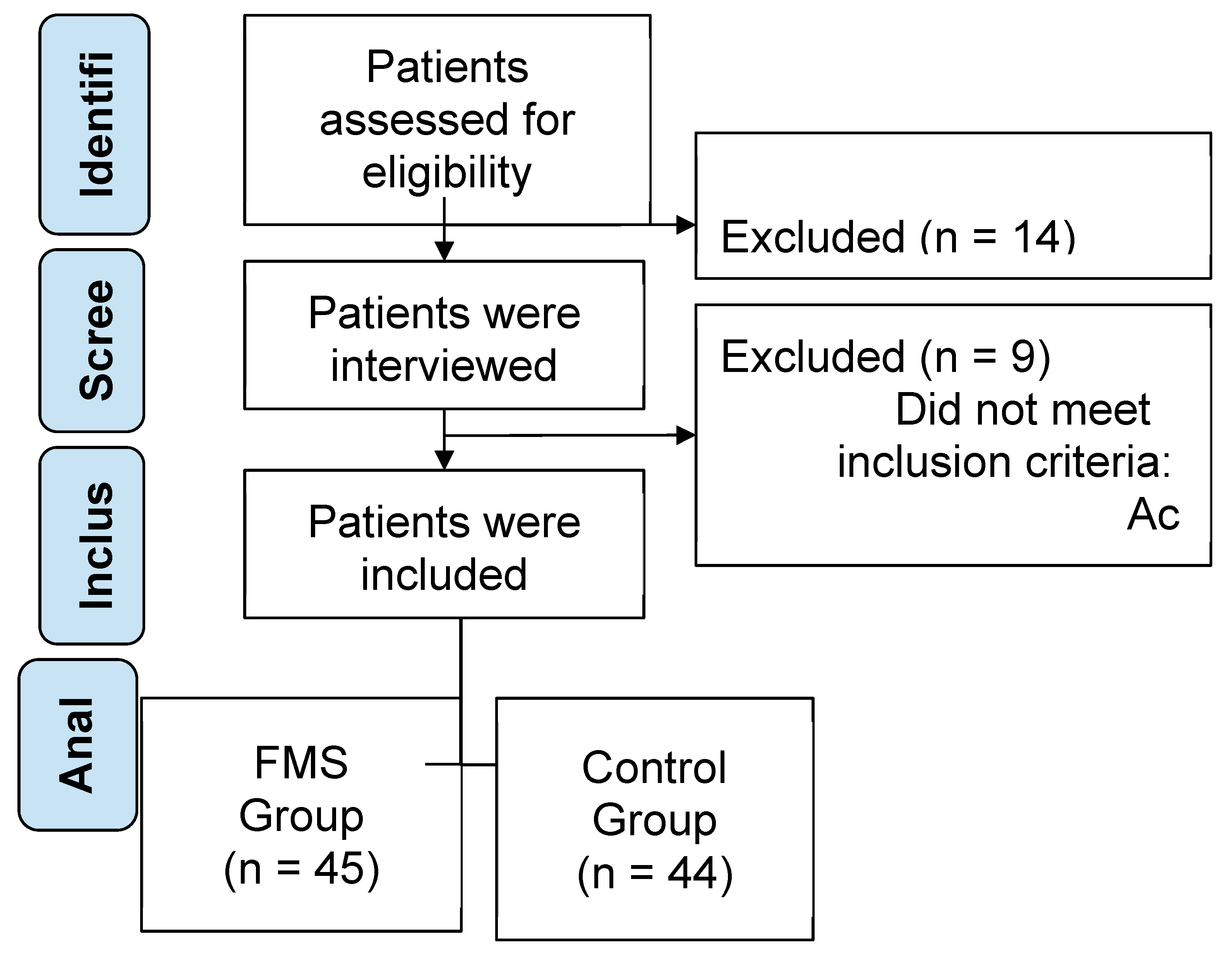

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.4. Outcomes

2.4.1. Anthropometric and Clinical Measurements

2.3.2. Dietary Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Sample

| Characteristics | FMS Group (n = 45) |

W | p-value | Control Group (n = 44) |

W | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Female/Male) | 33/12 | 30/14 | ||||

| Age (years) | 50.1 ± 8.5 | 0.973 | 0.293 | 48.7 ± 9.1 | 0.976 | 0.348 |

| Weight (Kg) | 72.5 ± 10.3 | 0.958 | 0.057 | 68.9 ± 9.7 | 0.963 | 0.064 |

| Height (m) | 1.62 ± 0.08 | 0.979 | 0.481 | 1.63 ± 0.07 | 0.981 | 0.507 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 27.5 ± 4.2 | 0.945 | 0.014* | 24.9 ± 3.8 | 0.951 | 0.018* |

| WHR | 0.89 ± 0.05 | 0.970 | 0.182 | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 0.975 | 0.225 |

| BIA (%) | ||||||

| Fat mass (%) | 34.5 ± 5.3 | 0.942 | 0.011* | 28.1 ± 4.7 | 0.946 | 0.015* |

| Fat-free mass (%) | 65.5 ± 5.3 | 0.940 | 0.02* | 71.9 ± 4.7 | 0.911 | 0.021* |

| Muscle mass (%) | 47.5 ± 4.8 | 0.943 | 0.019* | 49.3 ± 4.2 | 0.905 | 0.020* |

| VAS - Visual Analog Scale | ||||||

| Pain intensity (0-10 scale) | 6.8 ± 1.9 | 0.882 | <0.001*** | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.911 | <0.001*** |

| FSS - Fatigue Severity Scale | ||||||

| Total score | 5.1 ± 1.1 | 0.894 | <0.001*** | 4.8 ± 1.0 | 0.905 | <0.001*** |

| Daily Interference | 6.1 ± 1.2 | 0.890 | <0.001*** | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 0.907 | <0.001*** |

| Task Initiation | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 0.888 | <0.001*** | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 0.904 | <0.001*** |

| Motivation | 5.7 ± 1.3 | 0.891 | <0.001*** | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 0.902 | <0.001*** |

| Post-effort Fatigue | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 0.889 | <0.001*** | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 0.903 | <0.001*** |

| Social Engagement | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 0.886 | <0.001*** | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 0.904 | <0.001*** |

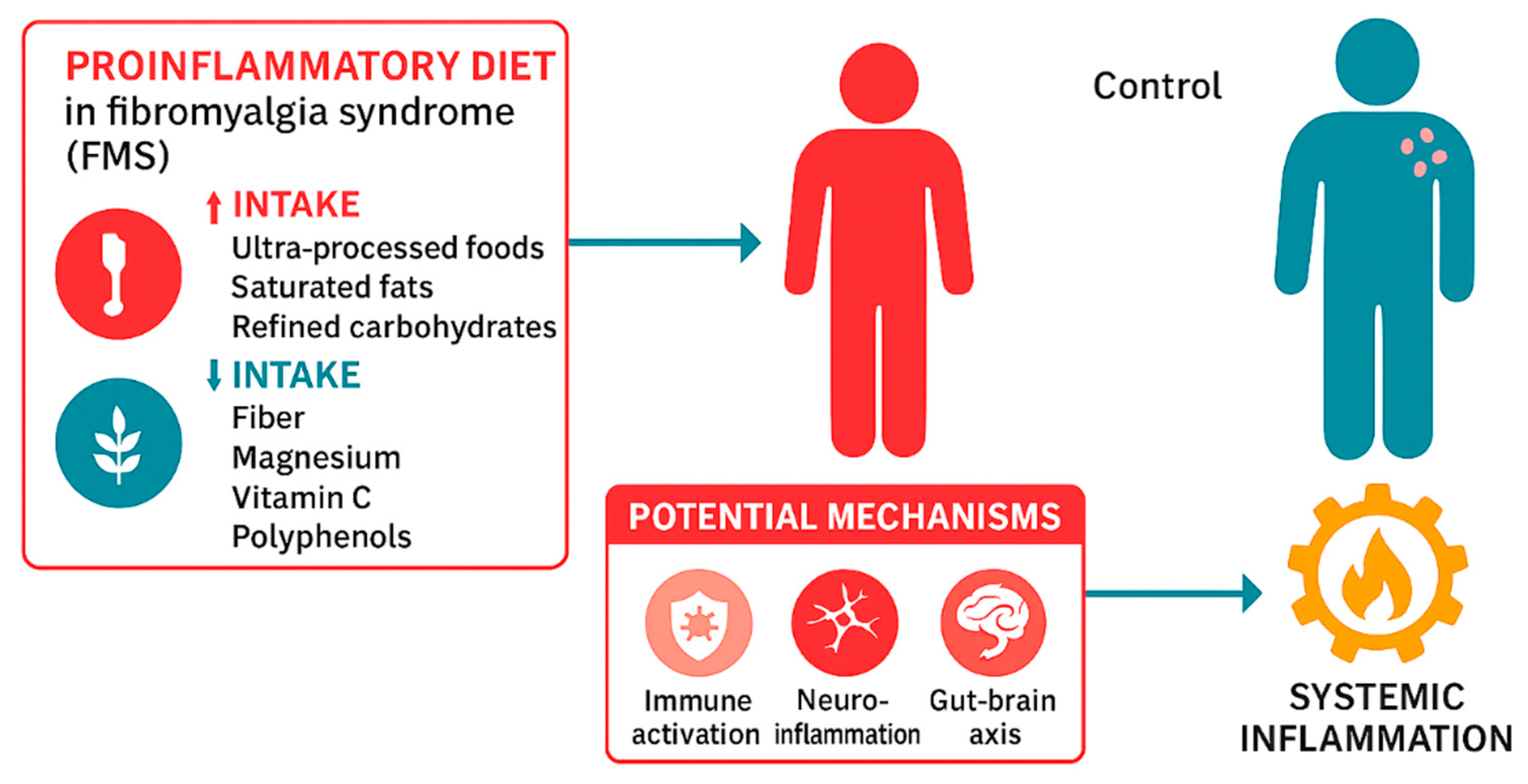

3.2. Inflammatory Dietary Intake and Ultra-processed Food Consumption

3.2.1. Ultra-processed Food Consumption (NOVA Classification)

3.3.2. Inflammatory Dietary Intake (DII/E-DII)

- Pro-inflammatory components

- Anti-inflammatory components

- 1.

- Macronutrient Intake

- 2.

- Micronutrient Intake

- 3.

- Bioactive Compounds

- 4.

- Food-Based Items

| Characteristics | FMS Group |

Control Group |

Statistic | p-value | Size effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOVA - Ultra-Processed Food Classification System | |||||

| Unprocessed/minimally processed foods | 35.1 ± 9.2% | 45.3 ± 8.7% | 264.0 | <0.001*** | -1.14 |

| Processed culinary ingredients | 14.3 ± 5.6% | 16.7 ± 4.9% | 272.0 | 0.04* | -0.46 |

| Processed foods | 16.1 ± 5.3% | 11.3 ± 4.6% | 675.0 | <0.01** | 0.97 |

| Ultra-processed foods | 34.5 ± 8.9 % | 26.7 ± 7.1 % | 695.0 | <0.001*** | 0.97 |

| DII/E-DII-Dietary Inflammatory Index | |||||

| Energy-adjusted score | 14.3 ± 5.6 | 16.7 ± 4.9 | 348.0 | 0.013* | -0.46 |

| Pro-inflammatory components (%) | 45.3 ± 8.7 | 35.1 ± 9.2 | 162.0 | <0.001*** | 1.14 |

| Macronutrients (g/day) | |||||

| Saturated Fats | 29.4 ± 6.1 | 24.8 ± 5.7 | 530.0 | 0.02* | 0.97 |

| Trans Fats | 4.1 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 488.0 | 0.045* | -0.48 |

| Cholesterol (mg/day) | 210.5 ± 35.4 | 187.6 ± 30.7 | 606.0 | 0.04* | 0.42 |

| Refined carbohydrates / sugar | 220.4 ± 35.2 | 198.7 ± 32.4 | 777.0 | 0.01* | 0.64 |

| Sodium | 1850.0 ± 320.0 | 2040.0 ± 340.0 | 502.0 | 0.039* | -0.56 |

| Anti-inflammatory components (%) | 16.1 ± 5.3 | 11.3± 4.6 | 595.0 | 0.03* | 0.97 |

| Macronutrients (g/day) | |||||

| Proteins | 68.4 ± 12.7 | 74.3 ± 11.8 | 316.0 | 0.048* | -0.48 |

| Fats | 82.6 ± 15.1 | 76.5 ± 13.9 | 487.0 | 0.058 | 0.42 |

| Carbohydrates | 220.4 ± 35.2 | 198.7 ± 32.4 | 777.0 | 0.01* | 0.64 |

| Fibers | 18.6 ± 4.5 | 21.3 ± 5.2 | 357.0 | 0.17 | -0.56 |

| Micronutrients (g/day) | |||||

| Vitamine C | 58.2 ± 12.9 | 74.6 ± 13.5 | 186.0 | <0.001*** | -1.24 |

| Magnesium | 240.5 ± 36.7 | 278.9 ± 40.2 | 223.0 | <0.001*** | -1.0 |

| Iron | 10.3 ± 2.1 | 11.2 ± 2.3 | 294.0 | 0.021* | -0.41 |

| Zinc | 8.1 ± 1.6 | 9.4 ± 1.7 | 369.0 | 0.234* | -0.79 |

| Bioactive compounds (g/day) | |||||

| Alcohol | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 1.4 | 198.0 | 0.01* | -1.03 |

| Caffeine (mg/day) | 182.3 ± 45.2 | 219.7 ± 52.8 | 216.0 | 0.03* | -0.76 |

| Flavonoids / Polyphenols | 185.2 ± 38.6 | 229.4 ± 41.3 | 204.0 | 0.009** | -1.08 |

| Food-based items (g/day) | |||||

| Turmeric | 5.8 ± 2.3 | 4.1 ± 1.9 | 574.0 | 0.03* | 0.81 |

| Garlic and onion | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 220.0 | 0.05 | -0.62 |

| Ginger | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 220.0 | 0.05 | -0.62 |

| Piperine | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 574.0 | 0.06 | 0.72 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Recommendations of Clinical practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR | American College of Rheumatology |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| BIA | Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| DII | Dietary Inflammatory Index |

| E-DII | Energy-adjusted Dietary Inflammatory Index |

| FIQ | Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire |

| FMS | Fibromyalgia Syndrome |

| FSS | Fatigue Severity Scale |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| NOVA | Ultra-Processed Food Classification System |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SES | Socioeconomic Status |

| SIR | Systemic Inflammatory Response |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| UPF | Ultra-Processed Food |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| WHR | Waist-to-Hip Ratio |

References

- García-Domínguez, M. Fibromyalgia and Inflammation: Unrevealing the Connection. Cells 2025, 14, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipovic, T.; Filipović, A.; Nikolic, D.; Gimigliano, F.; Stevanov, J.; Hrkovic, M.; Bosanac, I. Fibromyalgia: Understanding, Diagnosis and Modern Approaches to Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.A.; Asaad, F.; Patel, N.; Jain, E.; Abd-Elsayed, A. Management of Fibromyalgia: An Update. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín Pérez, S.E.; Lucas Hernández, L.; Oliva de la Nuez, J.L.; Soussi El-Hammouti, A.; González Cobiella, T.; del Castillo Rodríguez, J.C.; Herrera Pérez, M.; Martín Pérez, I.M. Evaluation of Sleep Patterns and Chronotypes in Spanish Women with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. J. Sleep Med. 2024, 21, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpton, J.E.; Moulin, D.E. Fibromyalgia. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2014, 119, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzcharles, M.A.; Yunus, M.B. The Clinical Concept of Fibromyalgia as a Changing Paradigm in the Past 20 Years. Pain Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 184835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Feijoo, F.; Samartin-Veiga, N.; Carrillo-de-la-Peña, M.T. Quality of Life in Patients with Fibromyalgia: Contributions of Disease Symptoms, Lifestyle and Multi-Medication. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 924405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez-Sánchez, C.M.; Duschek, S.; Reyes Del Paso, G.A. Psychological Impact of Fibromyalgia: Current Perspectives. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetingok, S.; Seker, O.; Cetingok, H. The Relationship between Fibromyalgia and Depression, Anxiety, Anxiety Sensitivity, Fear Avoidance Beliefs, and Quality of Life in Female Patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e30868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormsen, L.; Rosenberg, R.; Bach, F.W.; Jensen, T.S. Depression, Anxiety, Health-Related Quality of Life and Pain in Patients with Chronic Fibromyalgia and Neuropathic Pain. Eur. J. Pain 2010, 14, 127.e1–127.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensi Cabo-Meseguer, A.; Cerdá-Olmedo, G.; Trillo-Mata, J.L. Fibromyalgia: Prevalence, Epidemiologic Profiles and Economic Costs. Med. Clin. 2017, 149, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, L.P. Worldwide epidemiology of fibromyalgia. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2013, 17, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovrom, E.A.; Mostert, K.A.; Khakhkhar, S.; McKee, D.P.; Yang, P.; Her, Y.F. A Comprehensive Review of the Genetic and Epigenetic Contributions to the Development of Fibromyalgia. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siracusa, R.; Di Paola, R.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Impellizzeri, D. Fibromyalgia: Pathogenesis, Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Treatment Options Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.B.S.; Meng, J.; Zhang, J. Does Low Grade Systemic Inflammation Have a Role in Chronic Pain? Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 785214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assavarittirong, C.; Samborski, W.; Grygiel-Górniak, B. Oxidative Stress in Fibromyalgia: From Pathology to Treatment. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1582432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, C.; Schmid, S.; Michalski, M.; Tümen, D.; Buttenschön, J.; Müller, M.; Gülow, K. The Influence of Gut Microbiota on Oxidative Stress and the Immune System. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Ordóñez, J.F.; Moreno-Fernández, A.M.; Ramírez-Tejero, J.A.; Durán-González, E.; Martínez-Lara, A.; Cotán, D. Implication of Intestinal Microbiota in the Etiopathogenesis of Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnie, B.; Coppieters, I.; Denecker, S.; Six, J.; Danneels, L.; Meeus, M. Central Sensitization in Fibromyalgia? A Systematic Review on Structural and Functional Brain MRI. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2014, 44, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.; Schweinhardt, P. Dysfunctional Neurotransmitter Systems in Fibromyalgia, Their Role in Central Stress Circuitry and Pharmacological Actions on These Systems. Pain Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 741746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Rodríguez, A.; Reyes-Long, S.; Roldan-Valadez, E.; González-Torres, M.; Bonilla-Jaime, H.; Bandala, C.; Avila-Luna, A.; Bueno-Nava, A.; Cabrera-Ruiz, E.; Sanchez-Aparicio, P.; et al. Association of the Serotonin and Kynurenine Pathways as Possible Therapeutic Targets to Modulate Pain in Patients with Fibromyalgia. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Priego, L.N.; Cueto-Ureña, C.; Ramírez-Expósito, M.J.; Martínez-Martos, J.M. Fibromyalgia: A Review of the Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Multidisciplinary Treatment Strategies. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munipalli, B.; Allman, M.E.; Chauhan, M.; Niazi, S.K.; Rivera, F.; Abril, A.; Wang, B.; Wieczorek, M.A.; Hodge, D.O.; Knight, D.; Perlman, A.; Abu Dabrh, A.M.; Dudenkov, D.; Bruce, B.K. Depression: A Modifiable Risk Factor for Poor Outcomes in Fibromyalgia. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2022, 13, 21501319221120738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, H. Controversies and Challenges in Fibromyalgia: A Review and a Proposal. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2017, 9, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzadok, R.; Ablin, J.N. Current and Emerging Pharmacotherapy for Fibromyalgia. Pain Res. Manag. 2020, 2020, 6541798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masquelier, E.; D'haeyere, J. Physical Activity in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia. Jt. Bone Spine 2021, 88, 105202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, A.; Dominski, F.H.; Sieczkowska, S.M. What We Already Know about the Effects of Exercise in Patients with Fibromyalgia: An Umbrella Review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2020, 50, 1465–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardy, K.; Klose, P.; Busch, A.J.; Choy, E.H.; Häuser, W. Cognitive Behavioural Therapies for Fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD009796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metyas, C.; Aung, T.T.; Cheung, J.; Joseph, M.; Ballester, A.M.; Metyas, S. Diet and Lifestyle Modifications for Fibromyalgia. Curr. Rheumatol. Rev. 2024, 20, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tel Adıgüzel, K.; Köroğlu, Ö.; Yaşar, E.; Tan, A.K.; Samur, G. The Relationship between Dietary Total Antioxidant Capacity, Clinical Parameters, and Oxidative Stress in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Novel Point of View. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 68, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, G.; Dadar, M.; Chirumbolo, S.; Aaseth, J. Fibromyalgia and Nutrition: Therapeutic Possibilities? Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 103, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minerbi, A.; Khoutorsky, A.; Shir, Y. Decoding the Connection: Unraveling the Role of Gut Microbiome in Fibromyalgia. Pain Rep. 2024, 10, e1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poursalehi, D.; Tirani, S.A.; Shahdadian, F.; et al. Ultra-Processed Foods Intake in Relation to Metabolic Health Status, Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Adropin Levels in Adults. Nutr. J. 2024, 23, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.C.; Louzada, M.L.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; Baraldi, L.G.; Jaime, P.C. Ultra-Processed Foods: What They Are and How to Identify Them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Lawrence, M.; Costa Louzada, M.L.; Pereira Machado, P. Ultra-Processed Foods, Diet Quality, and Health Using the NOVA Classification System; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gibney, M.J. Ultra-Processed Foods: Definitions and Policy Issues. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2018, 3, nzy077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quetglas-Llabrés, M.M.; Monserrat-Mesquida, M.; Bouzas, C.; Mateos, D.; Ugarriza, L.; Gómez, C.; Tur, J.A.; Sureda, A. Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Biomarkers Are Related to High Intake of Ultra-Processed Food in Old Adults with Metabolic Syndrome. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Leo, E.E.; Meza Peñafiel, A.; Hernández Escalante, V.M.; Cabrera Araujo, Z.M. Ultra-Processed Diet, Systemic Oxidative Stress, and Breach of Immunologic Tolerance. Nutrition 2021, 91–92, 111419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensi, M.T.; Napoletano, A.; Sofi, F.; Dinu, M. Low-Grade Inflammation and Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption: A Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poti, J.M.; Braga, B.; Qin, B. Ultra-Processed Food Intake and Obesity: What Really Matters for Health—Processing or Nutrient Content? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2017, 6, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Evangelopoulos, A.; Tzivaki, I.; Daskalopoulou, S.; Adamou, A.; Michalaki Zafeiri, G.C.; Karampela, I.; Dalamaga, M.; Kounatidis, D. Ultra-Processed Foods and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: What Is the Evidence So Far? Biomolecules 2025, 15, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, F.; Vaidean, G.; Parekh, N. Ultra-Processed Foods and Cardiovascular Diseases: Potential Mechanisms of Action. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1673–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, M.M.; Lotfaliany, M.; Forbes, M.; Loughman, A.; Rocks, T.; O'Neil, A.; Machado, P.; Jacka, F.N.; Hodge, A.; Marx, W. Higher Ultra-Processed Food Consumption Is Associated with Greater High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein Concentration in Adults: Cross-Sectional Results from the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, A.E.D.S.C.; Araújo, L.F.; Levy, R.B.; Barreto, S.M.; Giatti, L. Association between Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Serum C-Reactive Protein Levels: Cross-Sectional Results from the ELSA-Brasil Study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2019, 137, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, G.M.D.S.; França, A.K.T.D.C.; Viola, P.C.A.F.; Carvalho, C.A.; Marques, K.D.S.; Santos, A.M.D.; Batalha, M.A.; Alves, J.D.A.; Ribeiro, C.C.C. Intake of Ultra-Processed Foods Is Associated with Inflammatory Markers in Brazilian Adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Querol, N.; Cabricano-Canga, L.; Bueno Hernández, N.; Gonçalves, A.Q.; Caballol Angelats, R.; Pozo Ariza, M.; Martín-Borràs, C.; Montesó-Curto, P.; Castro Blanco, E.; Dalmau Llorca, M.R.; et al. Nutrition and Chronobiology as Key Components of Multidisciplinary Therapeutic Interventions for Fibromyalgia and Associated Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Narrative and Critical Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almirall, M.; Musté, M.; Serrat, M.; Touriño, R.; Espartal, E.; Marsal, S. Restrictive Diets in Patients with Fibromyalgia: State of the Art. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elma, Ö.; Brain, K.; Dong, H.J. The Importance of Nutrition as a Lifestyle Factor in Chronic Pain Management: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.R.; Bernardo, A.; Costa, J.; Cardoso, A.; Santos, P.; de Mesquita, M.F.; Vaz Patto, J.; Moreira, P.; Silva, M.L.; Padrão, P. Dietary Interventions in Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review. Ann. Med. 2019, 51 (Suppl. 1), 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.R.; Bernardo, A.; de Mesquita, M.F.; Vaz-Patto, J.; Moreira, P.; Silva, M.L.; Padrão, P. An Anti-Inflammatory and Low Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, and Monosaccharides and Polyols Diet Improved Patient Reported Outcomes in Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 856216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, E.K.; Massoni, S.C.; Hoffart, C.M.; Takata, Y. Dietary Effects on Pain Symptoms in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Systematic Review and Future Directions. Nutrients 2023, 15, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdrich, S.; Hawrelak, J.A.; Myers, S.P.; Harnett, J.E. Determining the Association between Fibromyalgia, the Gut Microbiome and Its Biomarkers: A Systematic Review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondinella, D.; Raoul, P.C.; Valeriani, E.; Venturini, I.; Cintoni, M.; Severino, A.; Galli, F.S.; Mora, V.; Mele, M.C.; Cammarota, G.; et al. The Detrimental Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on the Human Gut Microbiome and Gut Barrier. Nutrients 2025, 17, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.-A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Khan, R.L.; Mayer, E.A.; Russell, I.J.; Walitt, B. The American College of Rheumatology Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia and Measurement of Symptom Severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.J.; Blue, M.N.M.; Hirsch, K.R.; Saylor, H.E.; Gould, L.M.; Nelson, A.G.; Smith-Ryan, A.E. Validation of InBody 770 Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis Compared to a Four-Compartment Model Criterion in Young Adults. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2021, 41, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, C.S.; Clark, S.R.; Bennett, R.M. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire: Development and Validation. J. Rheumatol. 1991, 18, 728–733. [Google Scholar]

- Miró, J.; Sánchez, A.; Nieto, R.; et al. Validación del Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) en población española. Rev. Esp. Reumatol. 2008, 35, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Leiva, J.M.; Sánchez, J.; et al. Aplicación de la escala visual analógica (VAS) para la evaluación del dolor en pacientes con fibromialgia en una muestra española. Med. Clin. (Barc.) 2009, 132, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, M.; Martínez, M.; et al. Validación de la Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) en población española con fibromialgia. Rev. Esp. Reumatol. 2010, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupiáñez, J.; Ballesteros, S.; et al. Validación de la Fatigue Severity Scale en población española con fibromialgia: Un estudio multicéntrico. Rev. Neurol. 2011, 53, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivappa, N.; Steck, S.E.; Hurley, T.G.; Hussey, J.R.; Ma, Y.; Ockene, I.S.; Wirth, M.D.; Fitzgerald, S.; Blair, C.K.; Hebert, J.R. Designing and Developing a Dietary Inflammatory Index. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0.2.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Srour, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Méjean, C.; Andrianasolo, R.M.; Chazelas, E.; Deschasaux, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Monteiro, C.A.; Julia, C.; Touvier, M. Ultra-Processed Food Intake and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Prospective Cohort Study (NutriNet-Santé). BMJ 2019, 365, l1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, R.; Pourkazemi, F.; Hashempur, M.H.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Rooney, K. Editorial: Diet, Nutrition, and Functional Foods for Chronic Pain. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1456706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minerbi, A.; Gonzalez, E.; Brereton, N.J.B.; Anjarkouchian, A.; Dewar, K.; Fitzcharles, M.-A.; Chevalier, S. Altered microbiome composition in individuals with fibromyalgia. Pain 2019, 160, 2589–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gil, A.M.; Elizondo-Montemayor, L.; Moreno-Rodríguez, A.; González-González, J.G.; Galván-Salazar, H.R.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, R.; Lavalle-González, F.J. The Role of Diet as a Modulator of the Inflammatory Process in the Neurological Diseases. Nutrients. 2023, 15(6), 1304. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Ultra-Processed Food and Gut Microbiota: Do Additives Affect the Microbiome? Nutrients 2025, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, M.; Aurino, L.; Cataldi, M.; Cacciapuoti, N.; Di Lauro, M.; Lonardo, M.S.; Gautiero, C.; Guida, B. A Close Relationship Between Ultra-Processed Foods and Adiposity in Adults in Southern Italy. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, M.J.; Forde, C.G.; Mullally, D.; Gibney, E.R. Ultra-Processed Foods: A Narrative Review of the Impact on Human Health. Nutrients 2023, 16, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyneke, G.L.; Lambert, K.; Beck, E.J. Food-Based Indexes and Their Association with Dietary Inflammation. Adv. Nutr. 2025, 16, 100400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, M.D.; Alcocer-Gómez, E.; Cano-García, F.J.; Sánchez-Domínguez, B.; Fernández-Riejo, P.; Moreno Fernández, A.M.; Fernández-Rodríguez, A.; De Miguel, M. Clinical Symptoms in Fibromyalgia Are Associated to Overweight and Lipid Profile. Rheumatol. Int. 2014, 34, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, S.; Prabhu, R.; Rangaswami, R.; Marappa, S.; Venkatesan, R.; Prevalence of Dyslipidemia in Fibromyalgia: A Single-Center Case Control Study from South India. ACR Convergence 2021. Available online: https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/prevalence-of-dyslipidemia-in-fibromyalgia-a-single-center-case-control-study-from-south-india (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Lopez-Garcia, E.; Schulze, M.B.; Manson, J.E.; Meigs, J.B.; Albert, C.M.; Rifai, N.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Consumption of Trans Fatty Acids is Related to Plasma Biomarkers of Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, L.; Ma, L.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, J.; Seo, J.H. High-Fat Diet Enhances Pain Sensitivity in Mice with Acid Saline-Induced Fibromyalgia-like Condition through Upregulation of TNF-α in Dorsal Root Ganglia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, Á.; Fernández-Sánchez, M.; Martínez-López, E.; Rodríguez-Blanque, R.; Aguilar-Cordero, M.J.; Sánchez-López, A.M. Nutrition and Chronobiology as Key Components of Multidisciplinary Management in Fibromyalgia. Nutrients 2024, 16, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Cruz, A.; Bacardí-Gascón, M.; Turnbull, W.H.; Rosales-Garay, P.; Severino-Lugo, I. A Flexible, Low-Glycemic Index Mexican-Style Diet in Overweight and Obese Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes Improves Metabolic Parameters During a 6-Week Treatment Period. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 1967–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escaffi, M.J.; Navia, C.; Quera, R.; Simian, D. Nutrición y enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal: posibles mecanismos en la incidencia y manejo. Rev. Med. Clin. Condes 2021, 32, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, L.; Buscail, C.; Sabate, J.-M.; Bouchoucha, M.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Touvier, M.; Monteiro, C.A.; Hercberg, S.; Benamouzig, R.; Julia, C. Association Between Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Results From the French NutriNet-Santé Cohort. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosanoff, A.; Dai, Q.; Shapses, S.A. Magnesium and Inflammation: Advances and Perspectives. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 115, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Barbagallo, M. The Role of Magnesium in the Pathogenesis of Metabolic Disorders. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbagallo, M.; Veronese, N.; Dominguez, L.J. Magnesium and Aging: Current Concepts and Future Perspectives. Nutrients 2021, 13, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Pérez, S.E.; Fernández Carnero, J.; Sosa Reina, M.D. Mecanismos y efectos terapéuticos de la terapia manual ortopédica. En Terapia manual ortopédica en el tratamiento del dolor; Quevedo García, A., Alonso Sal, A., Alonso Pérez, J.L., Eds.; Elsevier España: Madrid, España, 2022; pp. 87–110. ISBN 978-84-1382-020-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. The Causal Role of Magnesium Deficiency in the Neuroinflammation, Chronic Pain, Memory and Emotional Deficits Induced by Estrogen Decline. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 784119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosanoff, A.; Dai, Q.; Shapses, S.A. Essential Nutrient Interactions: Does Low or Suboptimal Magnesium Status Interact with Vitamin D and/or Calcium Status? Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdle, B.; Ghafouri, B.; Ernberg, M.; Larsson, B. Evidence of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Fibromyalgia: Deviating Muscle Energy Metabolism Detected Using Microdialysis and Magnetic Resonance. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Beevers, C.S.; Huang, S. The Therapeutic Potential of Curcumin in Inflammatory Diseases. Anti-Inflammatory & Anti-Allergy Agents in Medicinal Chemistry 2011, 10, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, V.P.; Sudheer, A.R. Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Properties of Curcumin. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 2007, 595, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Janmeda, P.; Docea, A.O.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Modu, B.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Oxidative Stress, Free Radicals and Antioxidants: Potential Crosstalk in the Pathophysiology of Human Diseases. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1158198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, M.; Abrahamse, H.; George, B.P. Flavonoids: Antioxidant Powerhouses and Their Role in Nanomedicine. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młynarska, E.; Biskup, L.; Możdżan, M.; Grygorcewicz, O.; Możdżan, Z.; Semeradt, J.; Uramowski, M.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Hypertension: The Insight into Antihypertensive Properties of Vitamins A, C and E. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, A.; Bianchi, M.; Fear, E.J.; Giorgi, L.; Rossi, L. Management of Fibromyalgia: Novel Nutraceutical Therapies Beyond Traditional Pharmaceuticals. Nutrients 2025, 17, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Valko, R.; Liska, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Flavonoids and Their Role in Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Human Diseases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2025, 413, 111489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Oliveira, B.; Lopes, C.; Freitas, P.; Moreira, P. The Association between Socioeconomic Status and Ultra-Processed Food Consumption in Portuguese Adults: The PORMETS Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).