1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic disorder marked by widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and often co-occurring mood disorders [

1,

2]. Patients frequently report cognitive difficulties, including issues with memory, attention or concentration, commonly referred to as “

fibro-fog”. Many individuals find these cognitive symptoms even more distressing than the pain itself [

3,

4]. Dyscognition, a term that encompasses both subjectively and objectively observed cognitive symptoms, suggests that

fibro-fog and dyscognition may represent the same phenomenon. These cognitive challenges exacerbate the disability associated with FM and significantly impact the daily functioning and quality of life of individuals. Given that FM is primarily characterized by widespread pain, it is unsurprising that pain, which is physiologically designed to command attention and motivate behavior, interferes with cognitive functioning [

5,

6]. Dyscognition in FM is associated with various socioeconomic and psychosocial consequences, including functional disability, unemployment, and increased healthcare utilization. It can be both frustrating and debilitating, impairing memory, concentration, and overall cognitive performance [

3,

7,

8]. Fatigue, which often includes symptoms such as brain fog, headaches, joint pain, and poor sleep, is believed to be linked to the overactivation of inflammatory mechanisms. Inflammation is thought to exacerbate fatigue symptoms though various pathways, including dysfunction of natural killer cells and T/B cell memory, increased activation of nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κB), chronic innate antiviral signaling, and elevated inflammatory markers [

9]. Collectively, these symptoms constitute key elements of the FM disease complex [

10].

Over the years, the World Health Organization (WHO) [

11] has developed an analgesic scale to guide healthcare professionals in managing pain based on its intensity. This scale suggests starting treatment with non-opioid medications, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, for mild pain; progressing to weak opioids, such as tramadol, for moderate pain; and using strong opioids, such as morphine, for severe pain. While this approach proves effective for many clinical conditions, patients with FM often face challenges in adhering to it. FM is a chronic pain disorder characterized by non-inflammatory pain, as a result, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are generally ineffective in managing FM pain. The pain experienced by individuals with FM is complex and multifactorial, often failing to respond to the standard analgesic treatments recommended by WHO. Many FM patients report fluctuating pain intensity, which does not align with the discrete categories of "mild," "moderate," or "severe," thus complicating the application of the analgesic ladder. Moreover, opioids are often less effective for treating the non-specific pain associated with FM, and their long-term use can be harmful due to potential side effects and the risk of dependence. Consequently, various pharmacological treatments have been explored to alleviate the diverse symptoms of FM.

The neurotransmitters involved in pain signaling include glutamate, substance P, nerve growth factor, and serotonin (5HT-2A and 5HT-3A). In contrast, neurotransmitters that inhibit pain transmission include norepinephrine, serotonin (5HT-1A, 5HT-1B), dopamine, endogenous opioids, endocannabinoids, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Patients with FM exhibit an imbalance, characterized by elevated levels of pain-facilitating neurotransmitters, such as glutamate and substance P, and reduced levels of pain-inhibiting neurotransmitters, such as GABA and norepinephrine. Pharmacologic treatments for FM aim to restore this balance in brain chemistry. However, drug therapy alone is often insufficient ant typically more effective when integrated into a broader, multifaceted treatment approach [

2]. This is particularly true when FM patients present symptoms that differ from the conventional expectations. Antidepressants, particularly tricyclics, have been widely recommended due to their efficacy in improving pain, sleep quality, and overall patient well-being. The role of antidepressants in FM management has been supported by numerous randomized controlled trials, which have demonstrated their ability to provide significant symptom relief [

1].

Treatment for FM aims to address different aspects of the syndrome, including pain, sleep disturbances, and cognitive dysfunction, representing a significant advancement toward a more nuanced understanding of its underlying pathophysiology, which is believed to involve central pain sensitization. Despite these advances, no single drug has been shown to be fully effective against the entire spectrum of FM symptoms, including

fibro-fog. This limitation has driven the exploration of combination therapies and highlighted the need for more comprehensive clinical trials to better address the diverse symptomatology of the condition [

12].

However, the complexity of FM treatment, along with the combined use of medications that affect the central nervous system (CNS), can lead to serious and diverse complications, ranging from cognitive decline and increased susceptibility to infections to neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders. One of the most common off-label uses involves the extensive prescription of opioids for managing nociplastic and musculoskeletal pain, despite limited evidence supporting their efficacy in these contexts. Similarly, benzodiazepines (BZP), which are not approved for pain management, are frequently prescribed to patients experiencing pain, often in combination with opioids or other medications. The high prevalence of concurrent BZP use highlights the need for further research into the risks and benefits of such practices, particularly in light of the FDA’s warnings about the potential dangers associated with co-administration. This emphasizes the urgent need for studies that evaluate the clinical and safety implications of off-label prescribing patterns and the exploration of alternative, evidence-based approaches to pain management [

13], particularly in light of the adverse anticholinergic effects these medications may induce [

14]. Furthermore, this combination of drugs increases the likelihood of falls and hospitalizations [

15].

Of particular concern in the FDA’s warning regarding the concomicant use of tramadol and BZP, wich carries a heightened risk of fatal outcomes [

16], given the substantial number of FM patients who combine these therapies. Neuropsychiatric complications, such as delirium, drug-induced parkinsonism, serotonin syndrome, and CNS depression, can arise from the use of commonly prescribed medications for FM, including opioids, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antipsychotics [

17]. CNS depression is a critical condition induced by substances that slow the brain and spinal cord, including illicit drugs, alcohol, and certain medications. Symptoms of CNS depression may include drowsiness, confusion, slurred speech, impaired coordination, and, in severe cases, can progress to coma or even death. [

18].

On the other hand, serotonin syndrome is a potentially life-threatening condition resulting from excessive serotonin levels in the body. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that plays a role in regulating mood, appetite, and sleep. An excess of serotonin can cause confusion, agitation, muscle twitching, fever, and seizures due to its accumulation in the brain and spinal cord [

19]. This syndrome typically occurs when multiple medications that increase serotonin levels are taken together, either due to overdose or drug interactions. The complexity of its symptoms, along with the variability in patient responses to treatment, makes the management of FM particularly challenging [

1].

Therefore, these pharmacological treatments may be considered as potential contributors to dyscognition in FM. It is exceptionally rare to find an individual with this diagnosis who is not regularly using antidepressants, antiepileptics or potent analgesics such as tramadol. Given that some of these medications carry warnings against operating heavy machinery, it seems plausible to expect that they may impair performance on cognitive assessments [

5].

For these reasons, the primary aim of the current study is to examinate the rational use of medications among patients diagnosed with FM, evaluate potential drug interactions, and assess the appropriateness of treatments in alignment with established clinical guidelines.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted to examinemedication usage, potential drug interactions and the treatment appropriateness in women with FM. Recruitment was conducted in Fibromyalgia Patient Associations and European Musculoskeletal Institute from Valencia (Spain), from September to November 2023.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Universidad CEU Cardenal Herrera (CEEI22/327, approval date: 14 October 2022).

Inclusion criteria: Women diagnosed with FM, as defined by the presence of pain at 18 tender points who are undergoing treatment for FM symptoms and have not made any changes to their treatment regimen in the past year, were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria: Patients under the age of 18, or those with concurrent medical conditions whose treatments could potentially confound pain management therapies, were excluded. Aditionally, patients not receiving any medication for pain management were also excluded.

The medication consumed by the patients, including both prescribed and over-the-counter drugs, as well as the severity of their condition, were analyzed. The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system, developed by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistic Methodology, was employed to categorize the drugs [

20]. In cases of combination therapies, the active principles were considered individually. Additionally, a literature review was conducted to identify the most recent clinical guidelines available for the treatment of FM.

2.1. Medication Analysis

Drug interactions were identified through peer review using CheckTheMeds® [

21] (

https://ww.checkthemeds.com), a program that analyzes interactions using a variety of information resources. These resources include monthly bulletins and technical data sheets from the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Health Products, drug interaction studies, the U.S, Food and Drug Administration, Stockley’s drug interactions, the American Geriatrics Society, the Thomson MICROMEDEX DRUGDEX® System database and Lexicomp®. This tool is a practical and efficient healthcare instrument designed to assist physicians and pharmacists in improving the quality of patient care. Its primary function is to detect pharmacological alerts, such as underdosages (which may lead to therapeutic ineffectiveness ), overdosages (which can result in increased side effect of drugs effects ), contraindicated drugs, or special circumstances (such as the risk of serotonin syndrome, sedation, or QT interval prolongation). Additionally, it provides information on drug incompatibilities or significant interactions, correlating them with the patient’s clinical presentation. Side effects, ineffective use, drug interactions, and other drug-related problems were identified from the patients’ perspective.

The platform categorizes alerts into four distinct classifications, ranging from mild to severe. These categories are defined as follows: "occasional", "caution and evaluate the benefit-to-risk ratio of the alert", " consider action to modify medication", and "avoid association of drugs".

2.2. Fibromyalgia Guidelines

In Spain, rheumatology services have developed a guideline for the management of FM that list medications not recommended for use, along with explanations of their potential consequences. Efforts are made to select a specific pharmacological therapies, but there is insufficient clinical evidence to guide these decisions. Furthermore, psychological therapy and physical activity are strongly recommended. Despite these recommendations, physicians should choose among the available medications, considering patients’ needs and weighing the advantages and disadvantages of each option [

22].

In the absence of more recent guidelines, the EULAR guideline for the treatment of FM [

23] has served as a key reference. This guideline emphasizes pain management as a primary focus, while also addressing other clinical outcomes such as fatigue, sleep quality, and the patient’s daily functional capacity. As a result, it provides a comprehensive approach to managing FM and its associated symptoms. The aim is to determinate the proportion of patients receiving appropriate prescriptions for managing their condition. The EULAR guidelines for FM treatment recommended initial interventions such as physical exercise, hydrotherapy or acupuncture. If these interventions are insufficient or if sleep disturbances arise, therapy should be individualized to include psychological interventions or pharmacological options such as amitriptyline, duloxetine, pregabalin, tramadol or cyclobenzaprine. In cases of significant disability due to FM, EULAR recommends participation in multimodal rehabilitation programs.The pharmacological treatment recommendations from the EULAR guideline are summarized in

Table 1.

2.3. Anticholinergic Load Scale

The cumulative effect of medications with anticholinergic properties, which inhibit the binding of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine to muscarinic receptors, is referred to as anticholinergic load. The effects of anticholinergic drugs are observed in both peripheral and central systems.

Peripheral effects typically include dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, tachycardia, and urinary retention, while central effects may involve cognitive impairment, confusion, and dizziness. Advanced age increases susceptibility to the CNS effects of anticholinergic drugs, which can contribute to dyscognition. Therefore, we assessed the anticholinergic burden in patients diagnosed with FM using the CRIDECO Anticholinergic Load Scale (CALS), where a score of 3 or higher is considered high anticholinergic risk [

14]. This was then compared with the anticholinergic alerts generated by ‘CheckTheMeds’.

4. Discussion

Medication review in FM treatments is a critical aspect of managing this chronic disease, which is characterized by widespread pain, fatigue, and other associated symptoms. The medication review process involves a comprehensive evaluation of all prescriptions, over-the-counter medications, and supplements taken by patients with FM. The primary objective is to optimize therapeutic outcomes, ensure the safety of pharmacological therapies, and improve patient adherence to treatment regimens.

A review of different guidelines has revealed a lack of consensus on the appropriate medications for the treatment of FM symptoms. The EULAR recommendations suggest certain active principles that are not entirely recommended for this patient population, due to medical alerts that emerged after their publication in 2017 [

22,

24,

25,

26]. In contrast, the Spanish Rheumatology Society [

22] provides a comprehensive review of available treatments but refrains from recommending any, as all lack sufficient evidence to support their effectiveness. These significant discrepancies may be attributed to the high standards required for a treatment to be scientifically validated.

Physicians face numerous challenges in determining the most appropriate treatment for FM patients, no official consensus exists on this matter. In addition, the complexity of FM treatment often results in patients becoming polymedicated, with 74.94% of the total drugs prescribed being used for pain management. This factor is also related to the patients’ experiences of fragility and dyscognition [

12,

27].

Focusing on the medications taken by patients and the potential issues associated with the involved active principles, we observe that in the group of drugs without anticholinergic load, paracetamol stands out is included. Several studies have confirmed that paracetamol is not effective in relieving pain in FM [

24,

28], yet it is used in 12.87% of their treatments within our population. Duloxetine is used by 18.52% of patients, while pregabalin and gabapentin are taken by 6.44%. Other studies suggest that duloxetine appears to be safe and effective, although its efficacy is dose-dependent [

24,

26,

28]. Pregabalin is recommended, but careful consideration is needed to ensure that patients do not have any underlying issues with the retinal nerves [

24,

26,

28]. Conversely, gabapentin has shown limited efficacy and is not fully recommended [

24,

28].

For the group of drugs with low anticholinergic burden (score 1), both prednisone and fluoxetine are not recommended due to their lake of efficacy [

28]. Likewise, the use of BZP for pain management is not recommended in these populations, given the absence of evidence supporting their effectiveness, as well as the potential risks of addiction and other adverse effects [

22]. Despite this, 18.24% of our patients are using BZP chronically. The recommended duration for BZP use is typically 2 to 4 weeks for insomnia and up to 12 weeks for anxiety treatment [

29], yet many patients in our population have been on these treatments for several years. Furthermore, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have less convincing evidence of efficacy in adults with FM [

28]. Nonetheless, 30.69% of our patients are using antidepressants. In some cases, these medications may be prescribed for reasons other than pain management. It is worth noting that the more medications a patient takes, the greater the risk of side effect or pharmacological interaction [

30].

In the medium anticholinergic burden group (score 2), tramadol is included. While opioids are generally not recommended for FM treatment [

28], some studies suggest that they may be appropriate for certain patients, though not as a first-line therapeutic strategy [

23,

24]. Tramadol represents 6.44% of prescribed pain treatments in our population, consistent with the view that is not generally recommended for all patients. On the other hand, an FDA review has highlighted a growing concern regarding the combined use of opioid medications with BZP or other CNS depressants, which has been associated with significant side effects such as shortness of breath, slowed breathing, respiratory depression, CNS depression, serotonin syndrome, and even fatalities [

16,

31]. Given the large number of patients in our study taking BZP, this may pose a significant risk in the future. In our study population, 58.62% of patients are concurrently using BZP and opioids, which, when combined with the alerts provided by “CheckTheMeds”, indicates a potential risk. Tramadol is mainly metabolized to O-desmethyltramadol by CYP2D6. This metabolite has a markedly higher affinity for the µ-opioid receptor than tramadol itself. Therefore, in individuals with increased CYP2D6 activity, standard doses of tramadol may increase the risk of adverse effects such as respiratory depression or serotonin syndrome, especially when taken with other CNS-acting drugs [

31]. Alerts indicating increased CYP2D6 activity were observed in 2.84% of our population (

Figure 2), which should be considered to better adapt tramadol use.

The final group includes active principles with a high anticholinergic burden (score 3). Amitriptyline is recognized as an effective option for reducing pain, sleep disorders, and fatigue in FM patients. However, it is important to acknowledge its potential adverse effects [

14,

24,

25,

26,

28]. Amitriptyline is consumed by 10.19% of our population either as a standalone pain treatment or in combination with other drugs ( 8.33%). It is considered one of the drugs with the highest anticholinergic potency, contributing a considerable burden (3 points) on its own. When combined with other anticholinergic drugs, such as BZP (1 point), SSRI (1 point) or tramadol (2 points), the anticholinergic side effects are exacerbated. This can lead to increased dyscognition, reduced attention, and impaired information processing [

14], which may contribute to the cognitive symptoms, often referred to as

fibro-fog, that are characteristic of this population.

Long-term exposure to anticholinergic medications has been linked to diminished cognitive function, including reduced information processing speed and impaired verbal recall. These effects persists even after the use of anticholinergic medications decreases [

32], presenting a significant health problem in polymedicated patients and those with multiple symptoms.

Fibro-fog is a legitimate and frequently misunderstood symptom associated with FM, warranting greater attention and understanding from both healthcare professionals and society. Exploring medications as potential contributors to cognitive dysfunction presents a valuable area for consideration. As of our study findings demonstrate, 50.93% of the study population has a substantial anticholinergic burden, manifesting similar symptoms to those documented in the

fibro-fog literature [

7,

8,

14].

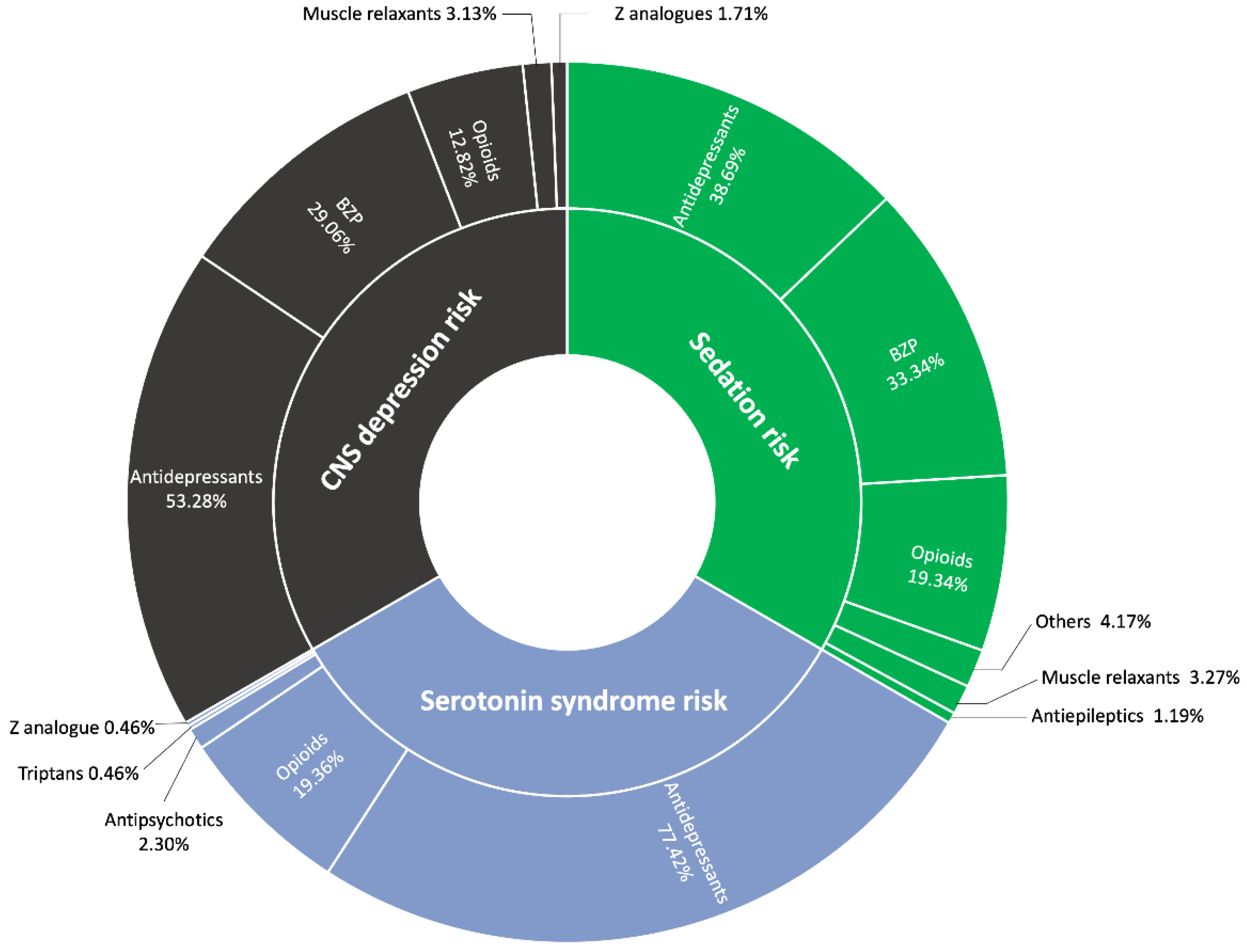

Regarding the distribution of alerts provided by ‘CheckTheMeds,’ the most prevalent alert is for CNS depression (21.70%), followed by sedation (20.22%) and serotonin syndrome (11.34%). CNS depression can lead to a range of issues, such as drowsiness, confusion, impaired motor coordination, and respiratory depression. In our study, opioids, antidepressants, and BZP were primarily responsible for these effects. This is particularly concerning in polymedicated patients, as the hepatic metabolism of these drugs may increase the risk of toxicity and overdose [

33].

Benzodiazepines and opioids both contribute to CNS depression, albeit through different mechanisms. BZP enhance GABA's inhibitory effects by binding to GABA-A receptors, which leads to sedation and anxiety relief. In contrast, opioids bind to mu-opioid receptors, inhibiting neurotransmitter release, reducing neuronal activity, and inducing pain relief, sedation, and respiratory depression. Both drug classes can impair cognition, and when taken in high doses or in combination with other CNS depressants (such as alcohol), they significantly increase the risk of overdose. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), on the other hand, elevate serotonin levels by inhibiting its reuptake, with therapeutic effects typically emerging after several weeks. However, SSRIs only achieve complete remission of depressive symptoms in approximately one-third of patients. Additionally, SSRIs may modulate microglial activation, potentially influencing neuroinflammation and cognitive symptoms [

34]. Additionally, serotonin syndrome, a potentially life-threatening condition, has been reported in patients treated with tramadol in combination with other serotonergic agents, or tramadol alone. Symptoms of serotonin syndrome include mental status changes, autonomic instability, neuromuscular disturbances, and gastrointestinal issues. Furthermore, combining tramadol with sedative drugs, such as BZP, increases the risk of CNS depression, which can lead to sedation, respiratory depression, coma, or even death due to the additive depressant effects on the nervous system [

35].

During a medication review, healthcare professionals can assess the efficacy, side effects,potential interactions, and overall medication burden for each patient. This process is particularly important in the context of FM, where polypharmacy is common due to associated symptoms such as irritable bowel syndrome, migraines, and sleep disorders, all of which increase the potential of drug-drug interactions. Our study highlights that 50.93% of the population carries a significant anticholinergic burden. Additionally, 21.70% are at risk of CNS depression, and 11.34% are at risk of serotonin syndrome, with a majority of these cases necessitating intervention. These adverse effects, including confusion and impaired coordination, can exacerbate symptoms such as

fibro-fog and contribute to increase frailty in this patient population [

7,

8,

14].

Periodic medication evaluations are crucial in the management of FM. These reviews typically involve assessing antidepressants, anticonvulsants, muscle relaxants, and analgesics. Since FM affects several body systems, an effective treatment approach often integrates pharmacological therapy with physical and psychological interventions. [

23]. A comprehensive medication review may result in dosage adjustments, the discontinuation of ineffective therapies, or the introduction of new medications. Moreover, it considers the patient’s lifestyle, preferences, and experiences with medication adherence, all of which are integral to developing a successful treatment plan.

5. Conclusions

Pharmacological reviews are a fundamental aspect of patient-centered healthcare, particularly for individuals with complex medical conditions such as FM. Regularly evaluating medication regimens ensures the safe and effective use of treatments, thereby enhancing the overall quality of care and improving health outcomes. By prioritizing these reviews, healthcare providers can help prevent serious complications, such as CNS depression, serotonin syndrome, and excessive anticholinergic burden, factors that can significantly affect patients’ quality of life.

Our study highlights the importance of assessing the rational use of medications in patients with FM. The high prevalence of polypharmacy and the significant anticholinergic burden observed in our population underscore the need for careful medication management. Assessing potential drug interactions is essential, as our findings reveal a substantial risk of CNS depression and serotonin syndrome, conditions that require prompt intervention.

Pharmacological interventions are essential in managing FM symptoms, not only to improve quality of life but also to ensure treatment safety. The anticholinergic burden plays a pivotal role in the overall well-being of FM patients, particularly in those who are polymedicated. This burden requires careful evaluation, as its reduction may help alleviate symptoms like fibro-fog. Additionally, given the lack of consensus regarding FM treatments, it is essential for physicians to meticulously assess each patient’s unique needs and responses. An individualized approach allows for more effective treatment and improves outcomes for individuals living with this debilitating condition.

In conclusion, our study emphasizes the necessity of aligning treatments with established clinical guidelines to optimize therapeutic outcomes. Regular medication reviews, personalized treatment plans, and diligent monitoring of drug interactions are essential to enhancing the safety and efficacy of FM management. By addressing these aspects, healthcare providers can significantly improve the quality of life for FM patients.

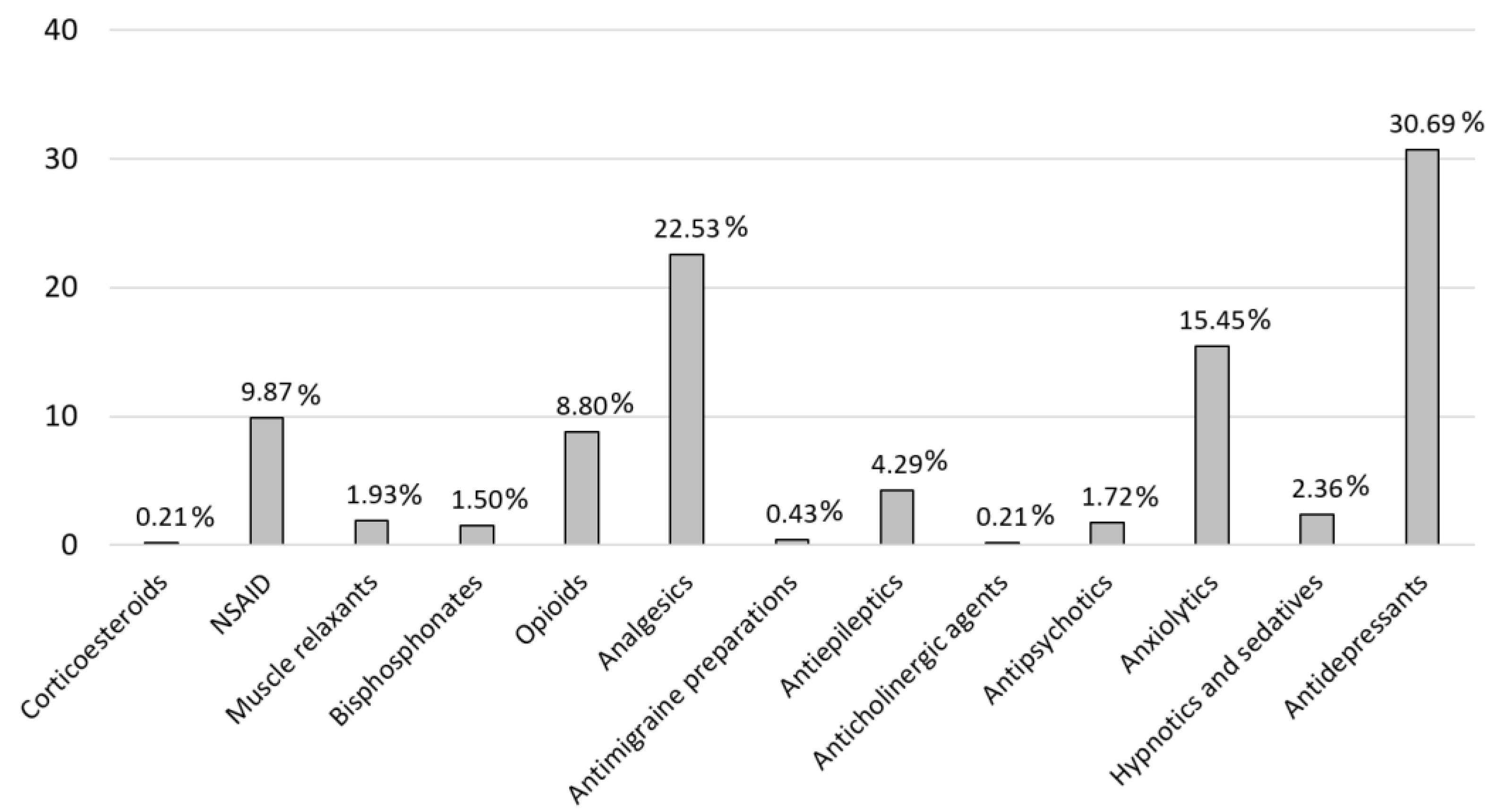

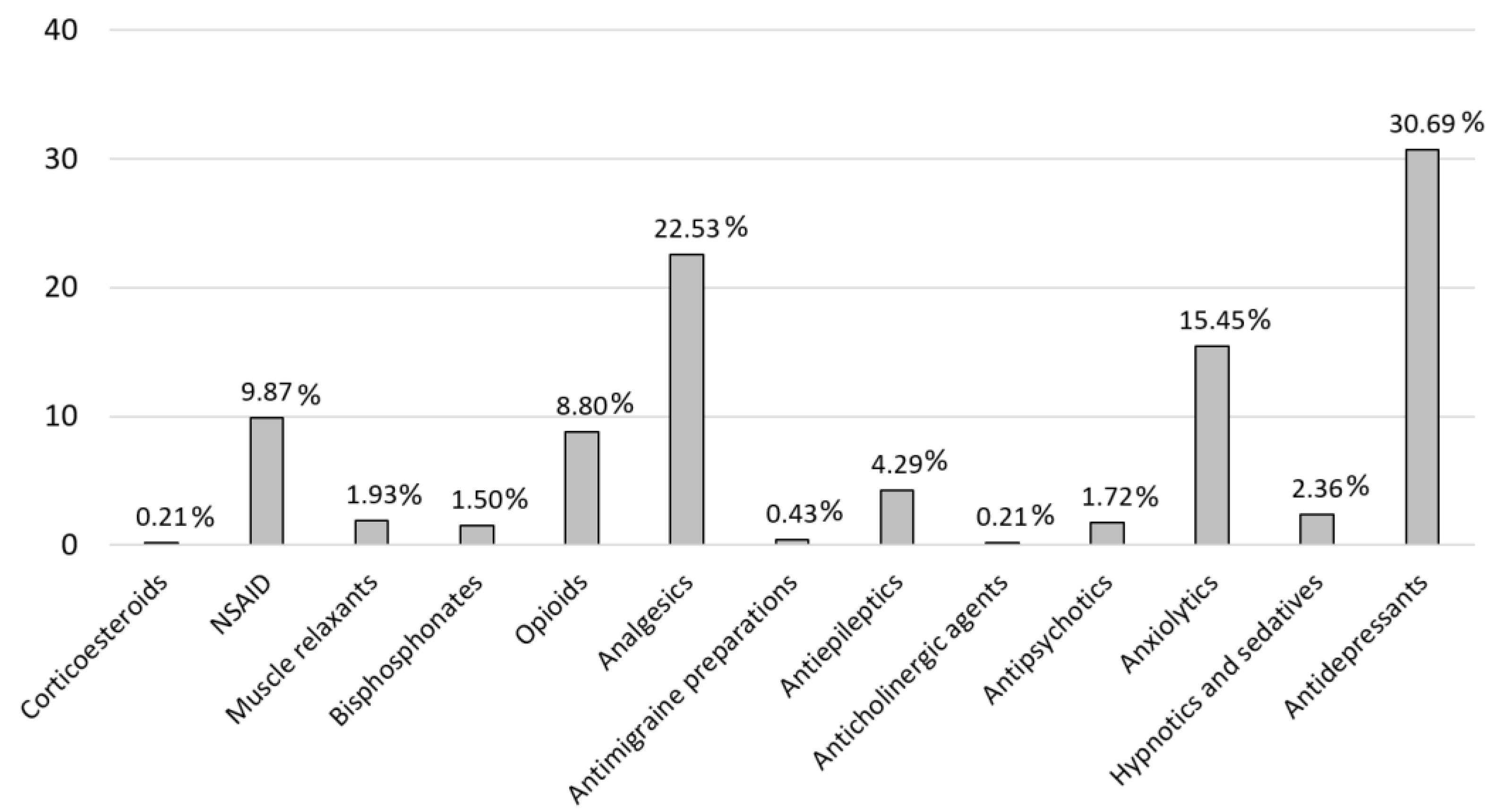

Figure 1.

Pain Medication distribution. Corticosteroids (H02A): Prednisone; NSAID (M01A): Chondroitin sulfate, dexketoprofen, etoricoxib, glucosamine, ibuprofen, naproxen, celecoxib; Muscle relaxants (M03B): Methocarbamol, baclofen, tizanidine; Bisphosphonates (M05B): Denosumab, risedronic acid; Opioids (N02A): Fentanyl, oxycodone, tapentadol, tramadol; Analgesics (N02B): Gabapentin, metamizole, paracetamol, pregabalin; Antimigraine preparations (N02C): Almotriptan, zolmitriptan; Antiepileptics (N03A): Topiramate, clonazepam, carbamacepine; Anticholinergic agents (N04A): Biperiden; Antipsychotics (N05A): Levosulpiride, olanzapine, quetiapine, chlorpromazine; Anxiolytics (N05B): Bromazepam, ketazolam, medazepam, alprazolam, diazepam, lorazepam, potassium clorazepate, hydroxyzine; Hypnotics and sedatives (N05C): Lormetazepam, melatonin, zolpidem, flurazepam; Antidepressants (N06A): Duloxetine, vortioxetine, citalopram, desvenlafaxine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, mirtazapine, trazodone, venlafaxine, maprotiline, paroxetine, amitriptyline.

Figure 1.

Pain Medication distribution. Corticosteroids (H02A): Prednisone; NSAID (M01A): Chondroitin sulfate, dexketoprofen, etoricoxib, glucosamine, ibuprofen, naproxen, celecoxib; Muscle relaxants (M03B): Methocarbamol, baclofen, tizanidine; Bisphosphonates (M05B): Denosumab, risedronic acid; Opioids (N02A): Fentanyl, oxycodone, tapentadol, tramadol; Analgesics (N02B): Gabapentin, metamizole, paracetamol, pregabalin; Antimigraine preparations (N02C): Almotriptan, zolmitriptan; Antiepileptics (N03A): Topiramate, clonazepam, carbamacepine; Anticholinergic agents (N04A): Biperiden; Antipsychotics (N05A): Levosulpiride, olanzapine, quetiapine, chlorpromazine; Anxiolytics (N05B): Bromazepam, ketazolam, medazepam, alprazolam, diazepam, lorazepam, potassium clorazepate, hydroxyzine; Hypnotics and sedatives (N05C): Lormetazepam, melatonin, zolpidem, flurazepam; Antidepressants (N06A): Duloxetine, vortioxetine, citalopram, desvenlafaxine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, mirtazapine, trazodone, venlafaxine, maprotiline, paroxetine, amitriptyline.

Figure 2.

Breakdown of alerts by causative therapeutic groups. * Other therapies included antipsychotics, antihistamines, and melatonin.

Figure 2.

Breakdown of alerts by causative therapeutic groups. * Other therapies included antipsychotics, antihistamines, and melatonin.

Table 1.

EULAR recommendations for the Management of Fibromyalgia [

23].

Table 1.

EULAR recommendations for the Management of Fibromyalgia [

23].

| Pharmacological Treatment |

Level of Evidence |

Grade |

Recommendation |

Agreement (%) |

| Amitriptyline (low doses) |

Ia |

A |

Some evidence |

100 |

| Duloxetine o milnacipran |

Ia |

A |

Some evidence |

100 |

| Pregabalin |

Ia |

A |

Some evidence |

94 |

| Cyclobenzaprine |

Ia |

A |

Some evidence |

75 |

| Tramadol |

Ib |

A |

Some evidence |

100 |

Table 2.

Alerts distribution.

Table 2.

Alerts distribution.

| |

Avoid |

Consider Intervention |

Know and Assess |

Occasional |

Total |

| CNS depression |

0.00% |

14.18% |

7.52% |

0.00% |

21.70% |

| Sedation |

0.00% |

14.30% |

4.81% |

1.11% |

20.22% |

| Serotoninergic syndrome |

0.00% |

10.48% |

0.86% |

0.00% |

11.34% |

| Loss of effectiveness |

0.00% |

0.00% |

2.59% |

3.82% |

6.41% |

| Toxicity |

0.00% |

1.73% |

1.97% |

1.23% |

4.93% |

| QT interval prolongation |

0.25% |

1.48% |

0.74% |

1.60% |

4.07% |

| Preventing risk of falls and fractures |

0.00% |

3.82% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

3.82% |

| Duplicity |

0.74% |

2.59% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

3.33% |

| Increased Adverse Drug Reactions |

0.00% |

1.48% |

1.60% |

0.12% |

3.21% |

| Haemorrhages |

0.37% |

1.60% |

1.11% |

0.00% |

3.08% |

| CYP2D6 |

0.00% |

0.37% |

2.47% |

0.00% |

2.84% |

| Consider reducing anticholinergic load |

0.00% |

2.71% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

2.71% |

| Therapeutic cascade |

0.00% |

2.47% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

2.47% |

| Consider alternative to antidepressants |

0.00% |

1.85% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

1.85% |

| Anticholinergic risk |

0.00% |

1.11% |

0.25% |

0.25% |

1.60% |

| Joint use of SSRIs and tricyclic |

0.00% |

1.48% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

1.48% |

| Assess need for 3 analgesics |

0.00% |

1.36% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

1.36% |

| Alternatives to clonazepam |

0.00% |

1.23% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

1.23% |

| Low blood pressure |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.86% |

0.00% |

0.86% |

| Antagonising the anticonvulsant effect |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.74% |

0.74% |

| CYP2C19 |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.37% |

0.00% |

0.37% |

| Hepatotoxicity |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.25% |

0.25% |

| NSAIDs + bisphosphonates |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.12% |

0.12% |

| TOTAL |

1.36% |

64.24% |

25.15% |

9.25% |

100% |

Table 3.

EULAR recommendation of FM treatment and drug combinations.

Table 3.

EULAR recommendation of FM treatment and drug combinations.

| |

N |

CALS for EULAR Recommendations |

Number of Other Drugs Combinate |

Total Cals Treatment |

Percentage of Patients with CALS ≥ 3 |

| Amitriptyline |

N= 11 (10.19%) |

3 |

4.3 ± 1.16 |

5.4 ± 1.56 |

100% |

| Duloxetine |

N= 19 (17.59%) |

0 |

3.16 ± 1.01 |

1.61 ± 0.77 |

35% |

| Tramadol |

N= 7 (6.48%) |

2 |

3.57 ± 0.79 |

3.57 ± 1.13 |

85.71% |

| pregabalin |

N= 6 (5.56%) |

0 |

3.83 ± 0.72 |

3 ± 0.81 |

50% |

| Amitriptyline + duloxetine |

N= 5 (4.63%) |

3 |

3.4 ± 1.14 |

3.6 ± 0.55 |

100% |

| Amitriptyline + tramadol |

N= 3 (2.78%) |

5 |

4.33 ± 1.53 |

6.67 ± 1.53 |

100% |

| Duloxetine + pregabalin |

N= 7 (6.48%) |

0 |

4.37 ± 2.50 |

2.14 ± 3.64 |

14.29% |

| Duloxetine + tramadol |

N= 12 (11.11%) |

2 |

5.08 ± 0.90 |

3.17 ± 1.34 |

75% |

| Pregabalin + tramadol |

N= 4 (3.7%) |

2 |

5.5 ± 1.91 |

3.5 ± 1.29 |

75% |

| Amitriptyline + duloxetine + pregabalin |

N= 1 (0.93%) |

3 |

8 |

6 |

100% |

| Tramadol + pregabalin + duloxetine |

N=3 (2.78%) |

2 |

6.33 ± 2.52 |

3.67 ± 2.89 |

33.33% |