Submitted:

29 September 2024

Posted:

30 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Selection of Burned Forest Areas

2.3. Landsat Time Series for Post-Fire Recovery

2.4. Post-Fire Recovery Percentage

2.5. Statistical Analysis of Recovery Differences in Drought Levels and Fire Severity

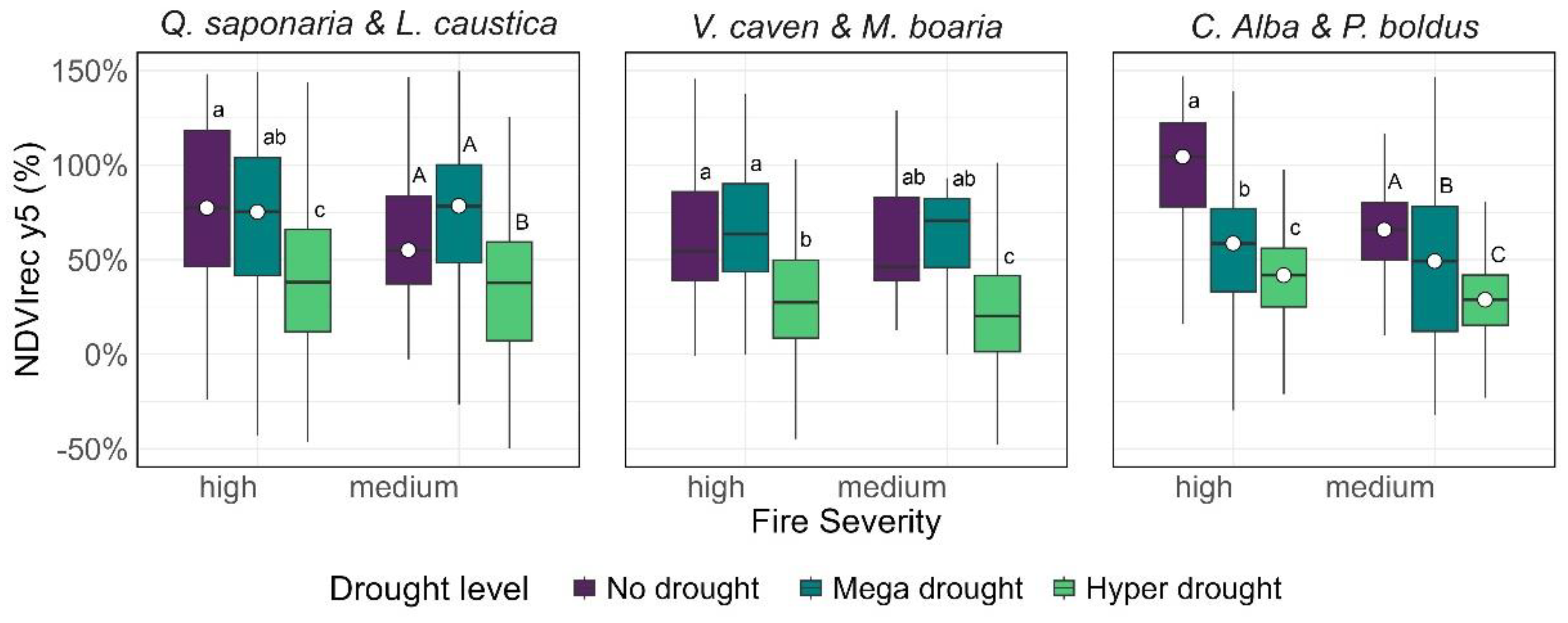

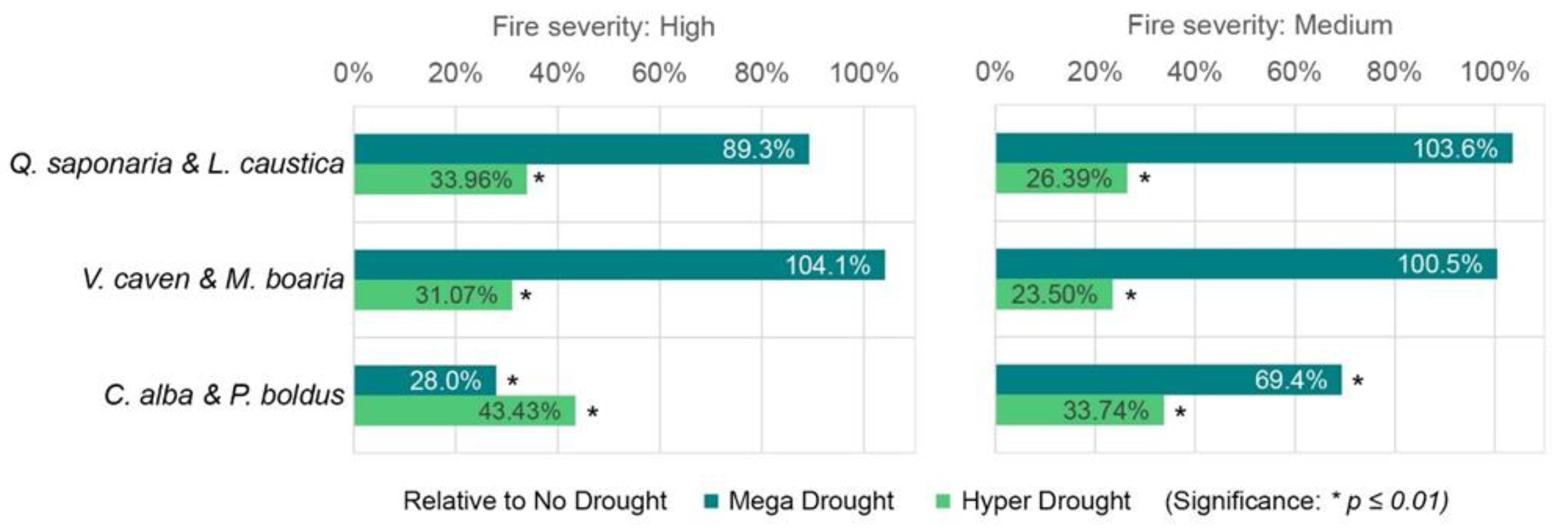

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Turner, M.G. Disturbance and landscape dynamics in a changing world. Ecology 2010, 91, 2833–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.S.; Pickett, S.T.A. The Ecology of Natural Disturbance and Patch Dynamics; Academic Press: 1985.

- Scheffer, M.; Carpenter, S.; Foley, J.A.; Folke, C.; Walker, B. Catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Nature 2001, 413, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidl, R.; Rammer, W.; Spies, T.A. Disturbance legacies increase the resilience of forest ecosystem structure, composition, and functioning. Ecological Applications 2014, 24, 2063–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenne, D.P.; Roíguez-Sánchez, F.; Coomes, D.; Baeten, L.; Verstraeten, G.; Hommel, P.W.F.M. Microclimate moderates plant responses to macroclimate warming. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS 2013, 110, 18561–18565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidl, R.; Thom, D.; Kautz, M.; Martin-Benito, D.; Peltoniemi, M.; Vacchiano, G.; Wild, J.; Ascoli, D.; Petr, M.; Honkaniemi, J.; et al. Forest disturbances under climate change. Nature Climate Change 2017, 7, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, D.; Rammer, W.; Seidl, R. Disturbances catalyze the adaptation of forest ecosystems to changing climate conditions. Global change biology 2017, 23, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Berdugo, M.; Liu, Y.-R.; Riedo, J.; Sanz-Lazaro, C.; Moreno-Jiménez, E.; Romero, F.; Tedersoo, L.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Increasing the number of stressors reduces soil ecosystem services worldwide. Nature Climate Change 2023, 13, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendall, E.R.; Bedward, M.; Boer, M.; Clarke, H.; Collins, L.; Leigh, A.; Bradstock, R.A. Changes in the resilience of resprouting juvenile tree populations in temperate forests due to coupled severe drought and fire. Plant Ecology 2022, 223, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, M.; von Hardenberg, J.; AghaKouchak, A.; Llasat, M.C.; Provenzale, A.; Trigo, R.M. On the key role of droughts in the dynamics of summer fires in Mediterranean Europe. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, D. Natural disturbances as drivers of tipping points in forest ecosystems under climate change – implications for adaptive management. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research 2023, 96, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreaud, R.D.; Alvarez-Garreton, C.; Barichivich, J.; Boisier, J.P.; Christie, D.; Galleguillos, M.; LeQuesne, C.; McPhee, J.; Zambrano-Bigiarini, M. The 2010–2015 megadrought in central Chile: Impacts on regional hydroclimate and vegetation. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 6307–6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Escaff, T.; Garreaud, R.; Bozkurt, D.; Jacques-Coper, M.; Pauchard, A. The key role of extreme weather and climate change in the occurrence of exceptional fire seasons in south-central Chile. Weather and Climate Extremes 2024, 45, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisier, J.P.; Rondanelli, R.; Garreaud, R.D.; Muñoz, F. Anthropogenic and natural contributions to the Southeast Pacific precipitation decline and recent megadrought in central Chile. Geophysical research letters 2016, 43, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreaud, R.D.; Boisier, J.P.; Rondanelli, R.; Montecinos, A.; Sepúlveda, H.H.; Veloso-Aguila, D. The Central Chile Mega Drought (2010–2018): A climate dynamics perspective. International Journal of Climatology 2020, 40, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.; Lara, A.; Altamirano, A.; Di Bella, C.; González, M.E.; Julio Camarero, J. Forest browning trends in response to drought in a highly threatened mediterranean landscape of South America. Ecological Indicators 2020, 115, 106401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Garreton, C.; Boisier, J.P.; Garreaud, R.; Seibert, J.; Vis, M. Progressive water deficits during multiyear droughts in basins with long hydrological memory in Chile. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, M.T.K.; Robles, V.; Tamburrino, Í.; Martínez-Harms, J.; Garreaud, R.D.; Jara-Arancio, P.; Pliscoff, P.; Copier, A.; Arenas, J.; Keymer, J.; et al. Extreme Drought Affects Visitation and Seed Set in a Plant Species in the Central Chilean Andes Heavily Dependent on Hummingbird Pollination. Plants 2020, 9, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.; Syphard, A.D.; Berdugo, M.; Carrasco, J.; Gómez-González, S.; Ovalle, J.F.; Delpiano, C.A.; Vargas, S.; Squeo, F.A.; Miranda, M.D.; et al. Widespread synchronous decline of Mediterranean-type forest driven by accelerated aridity. Nature Plants 2023, 9, 1810–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.E.; Gómez-González, S.; Lara, A.; Garreaud, R.; Díaz-Hormazábal, I. The 2010–2015 Megadrought and its influence on the fire regime in central and south-central Chile. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz, A.; Kitzberger, T.; Paritsis, J.; Veblen, T.T. Ecological and climatic controls of modern wildfire activity patterns across southwestern South America. Ecosphere 2012, 3, art103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia-Jalabert, R.; González, M.E.; González-Reyes, Á.; Lara, A.; Garreaud, R. Climate variability and forest fires in central and south-central Chile. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, C. Reseña Ecológica de los Bosques Mediterráneos de Chile. BOSQUE 1982, 4, 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luebert, F.; Pliscoff, P. Sinopsis bioclimática y vegetacional de Chile 2ed.; Editorial Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, R.; Marticorena, C.; Alarcón, D.; Baeza, C.; Cavieres, L.; Finot, V.L.; Fuentes, N.; Kiessling, A.; Mihoc, M.; Pauchard, A.; et al. Catálogo de las plantas vasculares de Chile. Gayana. Botánica 2018, 75, 1–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundel, P.W.; Arroyo, M.T.K.; Cowling, R.M.; Keeley, J.E.; Lamont, B.B.; Vargas, P. Mediterranean Biomes: Evolution of Their Vegetation, Floras, and Climate. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 2016, 47, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganteaume, A.; Camia, A.; Jappiot, M.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Long-Fournel, M.; Lampin, C. A Review of the Main Driving Factors of Forest Fire Ignition Over Europe. Environmental Management 2013, 51, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armesto, J.J.; Bustamante-Sánchez, M.; Díaz, M.F.; González, M.E.; Holz, A.; Nuñez-Avila, M.; Smith-Ramírez, C. Fire disturbance regimes, ecosystem recovery and restoration strategies in Mediterranean and temperate regions of Chile. In Fire effects on soils and restoration strategies; CRC Press: 2009; pp. 553–584.

- Becerra, P.; Smith-Ramirez, C.; Arellano, E. Evaluación de técnicas pasivas y activas pra la recuperación del bosque esclerófilo de Chile Central Corporación Nacional Forestal Imprenta Edición, Santiago, Chile, 2018.

- Montenegro, G.; Ginocchio, R.; Segura, A.; Keely, J.E.; Gómez, M. Fire regimes and vegetation responses in two Mediterranean-climate regions. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 2004, 77, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-González, S.; Cavieres, L.A. Litter burning does not equally affect seedling emergence of native and alien species of the Mediterranean-type Chilean matorral. International Journal of Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.R.; Fuentes, E.R. Does Fire Induce Shrub Germination in the Chilean Matorral? Oikos 1989, 56, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, R.H.; Collins, L.; Leigh, A.; Ooi, M.K.J.; Curran, T.J.; Fairman, T.A.; Resco de Dios, V.; Bradstock, R. Limits to post-fire vegetation recovery under climate change. Plant, Cell & Environment 2021, 44, 3471–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.E.; Yang, Z.; Cohen, W.B. Detecting trends in forest disturbance and recovery using yearly Landsat time series: 1. LandTrendr—Temporal segmentation algorithms. Remote Sensing of Environment 2010, 114, 2897–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbesselt, J.; Hyndman, R.; Newnham, G.; Culvenor, D. Detecting trend and seasonal changes in satellite image time series. Remote Sensing of Environment 2010, 114, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana-Soto, A.; García, M.; Aguado, I.; Salas, J. Assessing post-fire forest structure recovery by combining LiDAR data and Landsat time series in Mediterranean pine forests. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2022, 108, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wei, C.; Liu, X.; Zhu, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, Y. Object-based change detection for vegetation disturbance and recovery using Landsat time series. GIScience & Remote Sensing 2022, 59, 1706–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraverbeke, S.; Gitas, I.; Katagis, T.; Polychronaki, A.; Somers, B.; Goossens, R. Assessing post-fire vegetation recovery using red–near infrared vegetation indices: Accounting for background and vegetation variability. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2012, 68, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Pérez-Cabello, F.; Lasanta, T. Pinus halepensis regeneration after a wildfire in a semiarid environment: Assessment using multitemporal Landsat images. International Journal of Wildland Fire 2011, 20, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Vik, J.O.; Mysterud, A.; Gaillard, J.-M.; Tucker, C.J.; Stenseth, N.C. Using the satellite-derived NDVI to assess ecological responses to environmental change. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2005, 20, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Chen, H.W.; Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Yue, X.; He, B.; Guo, L.; Yuan, W.; Zhong, Z.; Huang, L.; et al. Global patterns and drivers of post-fire vegetation productivity recovery. Nature Geoscience 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, D.; Rojas, M.; Boisier, J.P.; Valdivieso, J. Projected hydroclimate changes over Andean basins in central Chile from downscaled CMIP5 models under the low and high emission scenarios. Climatic Change 2018, 150, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreaud, R.D.; Clem, K.; Veloso, J.V. The South Pacific Pressure Trend Dipole and the Southern Blob. Journal of Climate 2021, 34, 7661–7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, R.O.; Castillo-Soto, M.E.; Traipe, K.; Olea, M.; Lastra, J.A.; Quiñones, T. A Probabilistic Multi-Source Remote Sensing Approach to Evaluate Extreme Precursory Drought Conditions of a Wildfire Event in Central Chile. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 865406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Ramírez, C.; Castillo-Mandujano, J.; Becerra, P.; Sandoval, N.; Fuentes, R.; Allende, R.; Paz Acuña, M. Combining remote sensing and field data to assess recovery of the Chilean Mediterranean vegetation after fire: Effect of time elapsed and burn severity. Forest Ecology and Management 2022, 503, 119800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.; Mentler, R.; Moletto-Lobos, Í.; Alfaro, G.; Aliaga, L.; Balbontín, D.; Barraza, M.; Baumbach, S.; Calderón, P.; Cárdenas, F.; et al. Historical Fire Scar Database - 3. Satellital images after fires. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- CIREN-CONAF. Informe técnico final proyecto: Monitoreo de cambios, corrección cartográfica y actualización del catastro de bosque nativo en las regiones de Valparaíso, Metropolitana y Libertador Bernardo O’Higgins. 2013, 130.

- CIREN-CONAF. Informe técnico final proyecto: Monitoreo de cambios, corrección cartográfica y actualización del catastro de bosque nativo de la región del Maule. 2016, 90.

- CONAF, C.N.F. Monitoreo de Cambios, Corrección Gráfica y Actualización del Catastro de los Recursos Vegetacionales de la Región de Valparaíso, año 2019; Santiago, Chile, 2022; p. 70.

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Moreira-Muñoz, A.; Kolden, C.A.; Chávez, R.O.; Muñoz, A.A.; Salinas, F.; González-Reyes, Á.; Rocco, R.; de la Barrera, F.; Williamson, G.J.; et al. Human–environmental drivers and impacts of the globally extreme 2017 Chilean fires. Ambio 2019, 48, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.D.; Thode, A.E. Quantifying burn severity in a heterogeneous landscape with a relative version of the delta Normalized Burn Ratio (dNBR). Remote sensing of environment 2007, 109, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Parks, S.A.; Hegewisch, K.C. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Scientific Data 2018, 5, 170191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.E.; Yang, Z.; Gorelick, N.; Braaten, J.; Cavalcante, L.; Cohen, W.B.; Healey, S. Implementation of the LandTrendr Algorithm on Google Earth Engine. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret, F.; Keeling, E.G.; Sala, A. Components of tree resilience: Effects of successive low-growth episodes in old ponderosa pine forests. Oikos 2011, 120, 1909–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.M.; Roller, G.B. Early forest dynamics in stand-replacing fire patches in the northern Sierra Nevada, California, USA. Landscape Ecology 2013, 28, 1801–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, D.C.; Fontaine, J.B.; Robinson, W.D.; Kauffman, J.B.; Law, B.E. Vegetation response to a short interval between high-severity wildfires in a mixed-evergreen forest. Journal of Ecology 2009, 97, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langsrud, Ø. ANOVA for unbalanced data: Use Type II instead of Type III sums of squares. Statistics and Computing 2003, 13, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IPBES. Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (Version 1). Zenodo; 978-3-947851-20-1; 2019.

- Jolly, W.M.; Cochrane, M.A.; Freeborn, P.H.; Holden, Z.A.; Brown, T.J.; Williamson, G.J.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Climate-induced variations in global wildfire danger from 1979 to 2013. Nature Communications 2015, 6, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rundel, P.W.; Arroyo, M.T.K.; Cowling, R.M.; Keeley, J.E.; Lamont, B.B.; Pausas, J.G.; Vargas, P. Fire and Plant Diversification in Mediterranean-Climate Regions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2018, 9, 00851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeley, J.E.; Bond, W.J.; Bradstock, R.A.; Pausas, J.G.; Rundel, P.W. Fire in Mediterranean ecosystems: Ecology, evolution and management; Cambridge University Press: 2011.

- Falk, D.A.; van Mantgem, P.J.; Keeley, J.E.; Gregg, R.M.; Guiterman, C.H.; Tepley, A.J.; Jn Young, D.; Marshall, L.A. Mechanisms of forest resilience. Forest Ecology and Management 2022, 512, 120129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; MacDonald, G.; Okin, G.S.; Gillespie, T.W. Quantifying Drought Sensitivity of Mediterranean Climate Vegetation to Recent Warming: A Case Study in Southern California. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Rodríguez, M.Á.; Ameztegui, A.; Gelabert, P.; Rodrigues, M.; Coll, L. Short-term recovery of post-fire vegetation is primarily limited by drought in Mediterranean forest ecosystems. Fire Ecology 2023, 19, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Macua, J.J.; Ninyerola, M.; Zabala, A.; Domingo-Marimon, C.; Pons, X. Factors affecting forest dynamics in the Iberian Peninsula from 1987 to 2012. The role of topography and drought. Forest Ecology and Management 2017, 406, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, I.; Cogoni, D.; Calderisi, G.; Fenu, G. Short-Term Effects and Vegetation Response after a Megafire in a Mediterranean Area. Land 2022, 11, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resco de Dios, V.; Arteaga, C.; Hedo, J.; Gil-Pelegrín, E.; Voltas, J. A trade-off between embolism resistance and bark thickness in conifers: Are drought and fire adaptations antagonistic? Plant Ecology & Diversity 2018, 11, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guajardo Valdés, A.G. Respuestas ecofisiológicas de plantas de Lithraea caustica (Mol.) Hook et Arn. sometidas a restricción hídrica controlada. 2010.

- Peña-Rojas, K.; Donoso, S.; Pacheco, C.; Riquelme, A.; Gangas, R.; Guajardo, A.; Durán, S. Respuestas morfo-fisiológicas de plantas de Lithraea caustica (Anacardiaceae) sometidas a restricción hídrica controlada. Bosque (Valdivia) 2018, 39, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, M.; Plaza, Á.; Garfias, R. A recent review of fire behavior and fire effects on native vegetation in Central Chile. Global Ecology and Conservation 2020, 24, e01210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E.; Keeley, S.C. Post-Fire Regeneration of Southern California Chaparral. American Journal of Botany 1981, 68, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E. Resilience of mediterranean shrub communities to fires. In Resilience in mediterranean-type ecosystems; Dell, B., Hopkins, A.J.M., Lamont, B.B., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1986; pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Vita, A.; Serra, M.T.; Grez, I.; González, M.; Olivares, A. Respuesta del rebrote en espino (Acacia caven (Mol.) Mol.) sometido a intervenciones silviculturales en zona árida de Chile. Ciencias Forestales 1997, 12, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya-Tangarife, C.; De La Barrera, F.; Salazar, A.; Inostroza, L. Monitoring the effects of land cover change on the supply of ecosystem services in an urban region: A study of Santiago-Valparaíso, Chile. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viedma, O.; Meliá, J.; Segarra, D.; Garcia-Haro, J. Modeling rates of ecosystem recovery after fires by using landsat TM data. Remote Sensing of Environment 1997, 61, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenberg, L.; Malkinson, D.; Beeri, O.; Halutzy, A.; Tesler, N. Spatial and temporal patterns of vegetation recovery following sequences of forest fires in a Mediterranean landscape, Mt. Carmel Israel. CATENA 2007, 71, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, A.; Tague, C.; Clark, R. Characterizing post-fire vegetation recovery of California chaparral using TM/ETM+ time-series data. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2007, 28, 1339–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, S.; Jones, S.; Soto-Berelov, M.; Skidmore, A.; Haywood, A.; Nguyen, T.H. Using Landsat Spectral Indices in Time-Series to Assess Wildfire Disturbance and Recovery. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, R.; Dennison, P.E.; Huang, C.; Moritz, M.A.; D'Antonio, C. Effects of fire severity and post-fire climate on short-term vegetation recovery of mixed-conifer and red fir forests in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. Remote Sensing of Environment 2015, 171, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, B.C.; Hudak, A.T.; Kennedy, R.E.; Braaten, J.D.; Henareh Khalyani, A. Examining post-fire vegetation recovery with Landsat time series analysis in three western North American forest types. Fire Ecology 2019, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agee, J.K. Fire ecology of Pacific Northwest forests; Island press Washington, DC: 1993; Volume 499.

- Meng, R.; Wu, J.; Zhao, F.; Cook, B.D.; Hanavan, R.P.; Serbin, S.P. Measuring short-term post-fire forest recovery across a burn severity gradient in a mixed pine-oak forest using multi-sensor remote sensing techniques. Remote Sensing of Environment 2018, 210, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Ramírez, C.; Castillo-Mandujano, J.; Becerra, P.; Sandoval, N.; Allende, R.; Fuentes, R. Recovery of Chilean Mediterranean vegetation after different frequencies of fires. Forest Ecology and Management 2021, 485, 118922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tian, Y.; Myneni, R.B.; Ciais, P.; Saatchi, S.; Liu, Y.Y.; Piao, S.; Chen, H.; Vermote, E.F.; Song, C.; et al. Widespread decline of Congo rainforest greenness in the past decade. Nature 2014, 509, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilker, T.; Lyapustin, A.I.; Tucker, C.J.; Hall, F.G.; Myneni, R.B.; Wang, Y.; Bi, J.; Mendes de Moura, Y.; Sellers, P.J. Vegetation dynamics and rainfall sensitivity of the Amazon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 16041–16046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.M.; Asner, G.P. Effects of long-term rainfall decline on the structure and functioning of Hawaiian forests. Environmental Research Letters 2017, 12, 094002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, M.; Segura, A.M.; Fuentes, E.R. Limiting mechanisms in the regeneration of the Chilean matorral–Experiments on seedling establishment in burned and cleared mesic sites. Plant Ecology 2000, 147, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Castillo, T.; Miranda, A.; Rivera-Hutinel, A.; Smith-Ramírez, C.; Holmgren, M. Nucleated regeneration of semiarid sclerophyllous forests close to remnant vegetation. Forest Ecology and Management 2012, 274, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solans Vila, J.P.; Barbosa, P. Post-fire vegetation regrowth detection in the Deiva Marina region (Liguria-Italy) using Landsat TM and ETM+ data. Ecological Modelling 2010, 221, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Burriel, F.; Delicado, P.; Cucchietti, F.M. Wildfires Vegetation Recovery through Satellite Remote Sensing and Functional Data Analysis. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justin, E.; David, V. Landscape-level interactions of prefire vegetation, burn severity, and postfire vegetation over a 16-year period in interior Alaska. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2005, 35, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.; Chambers, J.C.; Pyke, D.A.; Pierson, F.B.; Williams, C.J. A review of fire effects on vegetation and soils in the Great Basin Region: Response and ecological site characteristics. 2013.

- Fernández-García, V.; Calvo, L.; Suárez-Seoane, S.; Marcos, E. Remote Sensing Advances in Fire Science: From Fire Predictors to Post-Fire Monitoring. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cabello, F.; Montorio, R.; Alves, D.B. Remote sensing techniques to assess post-fire vegetation recovery. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health 2021, 21, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Skutsch, M.; Paneque-Gálvez, J.; Ghilardi, A. Remote sensing of forest degradation: A review. Environmental Research Letters 2020, 15, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L. Tropical forest recovery: Legacies of human impact and natural disturbances. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 2003, 6, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holl, K.D.; Aide, T.M. When and where to actively restore ecosystems? Forest Ecology and Management 2011, 261, 1558–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, J.J.; Cayuela, L.; Echeverria, C.; Salas, J.; Rey Benayas, J.M. Monitoring land cover change of the dryland forest landscape of Central Chile (1975–2008). Applied Geography 2010, 30, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armesto, J.J.; Arroyo, K.; Mary, T.; Hinojosa, L.F. The Mediterranean environment of Central Chile. In The physical geography of South America; Velben, T.T., K.R.Y., Orme, A.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, 2007; Volume 7, pp. 184–199. [Google Scholar]

- Mamadaliev, D.; Touko, P.L.M.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-C. ESFD-YOLOv8n: Early Smoke and Fire Detection Method Based on an Improved YOLOv8n Model. Fire 2024, 7, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, W.R.L.; Hicke, J.A.; Fisher, R.A.; Allen, C.D.; Aukema, J.; Bentz, B.; Hood, S.; Lichstein, J.W.; Macalady, A.K.; McDowell, N.; et al. Tree mortality from drought, insects, and their interactions in a changing climate. New Phytologist 2015, 208, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, H.D. Response of past and present Mediterranean ecosystems to environmental change. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 2003, 27, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret, F.; Escudero, A.; Iriondo, J.M.; Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Valladares, F. Extreme climatic events and vegetation: The role of stabilizing processes. Global Change Biology 2012, 18, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, N.S.; Jarvis, D.; Veblen, T.T.; Pickett, S.T.A.; Kulakowski, D. Is initial post-disturbance regeneration indicative of longer-term trajectories? Ecosphere 2017, 8, n. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, Y.H.; Hirschi, M.; Thiery, W.; El-Kenawy, A.M.; Yang, C. Drought characteristics in Mediterranean under future climate change. npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 2023, 6, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).