1. Introduction

The environmental problems caused by the consumption of energy obtained from fossil fuels have generated growing global concerns. These fuels produce gases that contribute significantly to the worsening of the greenhouse effect, which highlights the urgent need to seek cleaner and more sustainable alternatives [

1,

2,

3]. In this scenario, enzymatic transesterification stands out for its ability to generate renewable, biodegradable and non-toxic fuel from triglycerides, with lower emissions of exhaust gases and greenhouse effect [

4,

5].

The production of biodiesel using immobilized lipases is a promising approach in the search for alternative and sustainable energy sources in order to mitigate the environmental problems associated with the use of fossil fuels [

6,

7,

8]. In recent years, there has been a gradual transition from chemical catalysts to enzymes as catalysts in biodiesel production, in line with the search for more sustainable processes [

9,

10]. In this context, lipases emerge as an environmentally friendly and efficient alternative for the production of biodiesel and offer significant advantages over traditional chemical methods [

11,

12,

13,

14].

The use of lipases in the catalysis of the transesterification has shown itself to be especially promising. Unlike chemical catalysts, lipases offer milder reaction conditions, higher selectivity, substrate specificity and an absence of unwanted byproducts [

11,

15,

16]. These characteristics make biocatalysis an attractive option due to their eco-efficiency and the reduction in the environmental impacts associated with the biodiesel production process [

6,

12,

16]. In addition, the use of lipases in transesterification allows the use of alternative raw materials, such as waste cooking oils, thereby contributing to a reduction in waste and the circular economy [

17,

18,

19]. This approach not only minimizes competition with food sources, but also proves to be economically viable, since waste cooking oils are generally more affordable in terms of cost [

20,

21].

Although there are still challenges to overcome, such as the high cost of commercial enzymes and the need to optimize reaction conditions, immobilized lipases emerge as a viable technological solution for sustainable biodiesel production on an industrial scale [

18,

22]. Enzymatic immobilization allows lipases to be reused, which reduces operating costs and improves several enzymatic properties such as stability, selectivity and resistance to inhibitors [

23,

24].

There have been many studies in the field of enzyme immobilization applied to biodiesel production. Shao et al. [

25] obtained a conversion of 63.6% of the methyl esters under ideal conditions for the immobilization of lipases from

Candida rugosa in chitosan, while Bergamasco obtained a yield of 66.3% using a PVA support in the immobilization of lipases from

Rhizomucor miehei [

26].

Several immobilization techniques can be used, such as adsorption, covalent bonding, encapsulation and cross-linking [

23,

24]. Among them, encapsulation stands out for its potential by confining enzymatic molecules in microcapsules [

27]. These microcapsules protect enzymes against adverse conditions and allow controlled release, thus increasing catalytic efficiency [

27]. Despite challenges such as the development of compatible materials, encapsulation is highly advantageous for the production of biodiesel with immobilized lipases and improves the stability and efficiency of enzymes, especially on a large scale [

27,

28].

Based on the above, this study aimed to use the extract rich in lipase produced by an Amazonian endophytic fungus, immobilized in calcium alginate, for the production of biodiesel from the transesterification of waste cooking oil with ethanol. The lipolytic extract has catalytic potential similar to that of industrial lipases, allows the reuse of the biocatalyst and increases the efficiency of the process. In addition, the use of waste cooking oil and ethanol makes the reaction more sustainable and aligned with the principles of green chemistry and is an ecological and viable alternative to produce biofuels.

2. Materials and Methods

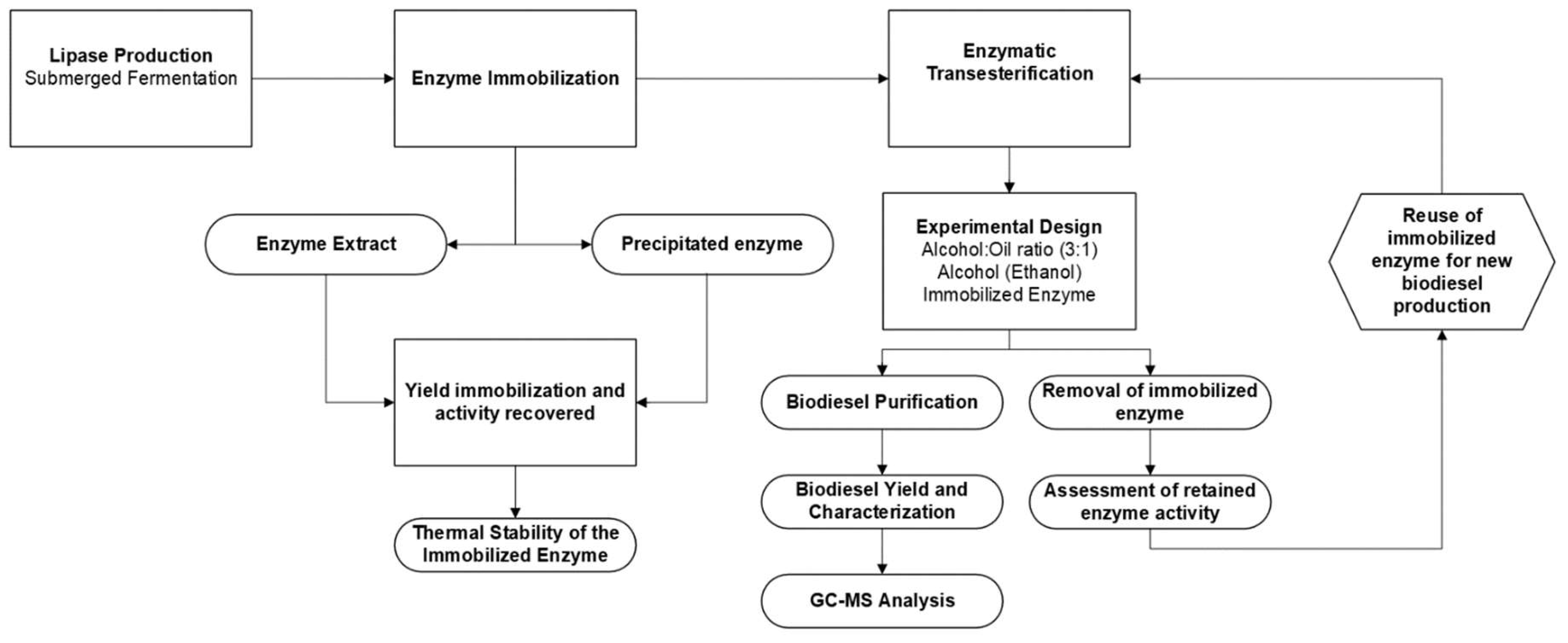

The present study was conducted following the steps described in the flowchart shown in

Figure 1.

2.1. Microorganism

The endophytic fungus

Endomelanconiopsis endophytica QAT_7AC isolated from

Aniba canelilla (Lauraceae) was used in the present study for production of lipase. The fungus is deposited in the Central Microbiological Collections (CCM) of the Amazonas State University (UEA) and was previously selected as a good producer of the enzyme [

29]. Its reactivation was performed on potato dextrose agar (PDA) in a BOD incubator (TE-39I, Tecnal, Brazil) at 30 °C for 11 days.

2.2. Lipase Production

The fungus was grown in Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL of liquid medium composed of NH

2NO

3 (1.0 g/L), MgSO

4.7H

2O (0.6 g/L), KH

2PO

4 (1.0 g/L), peptone (20 g/L) and olive oil (1%), pH 6.0 [

30].

E. endophytica was inoculated with three mycelial discs (5 mm diameter) taken from the edge of the colony grown in PDA. The flasks were incubated in a shaker (TE-4200, Tecnal, Brazil) for five days at 28 °C under agitation at 160 rpm. The experiments were conducted in triplicate. At the end of the 5

th day, the lipolytic extract (LE) was filtered and used in the subsequent steps.

2.3. Determination of Lipase Enzyme Activity

The lipolytic activity was quantified according to the methodology of Winkler and Stuckmann [

31], whereby an emulsion of

p-nitrophenyl palmitate (pNPP) was prepared by adding, dropwise, 10% by volume of solution A (30 mg of pNPP dissolved in 10 mL of isopropanol) in 90% by volume of solution B (0.4 g of Triton X-100; 0.1 g of gum arabic and 90 mL of Tris buffer 50 mM HCL, PH 7.0) under intense agitation. The emulsion obtained and the previously filtered enzyme extract samples were stabilized for 5 min at 37

oC. An aliquot of 0.2 mL of the samples was added to 1.8 mL of the substrate emulsion and the mixture was incubated for 15 min at 40 °C. The absorbance of the mixtures was measured in a spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Japan) at 410 nm [

32]. One unit (U) of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required for the release of 1.0 µmol of

p-nitrophenol per minute under assay conditions.

The dosage of proteins present in the enzyme extract was determined using the Bradford method [

33], whereby 100 µL of enzyme extract was mixed with 1,000 µL of Bradford reagent, followed by reading the absorbance in a spectrophotometer at 595 nm. Bovine serine albumin (BSA) was used for the construction of the standard curve.

2.4. Enzyme Extract Precipitation

Ethanol was used for enzymatic precipitation, according to the methodology of Costa et al. [

34]. With the aid of a burette, 90 mL of 99% ethanol were added at 2 mL/min to 10 mL of enzyme extract in an ice bath. After the addition of ethanol, the mixture was placed in a freezer at -20 °C for 2 h and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 15 min. Subsequently, the precipitate was resuspended in 0.05 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 6.0 and the precipitated lipolytic extract (PLE) was used in the subsequent steps.

2.5. Calculation of Specific Activity, Recovery Percentage and Purification Factor

The PLE was evaluated for the specific activity (SA), the percentage of recovery (R), and the purification factor (PF), in relation to the specific enzymatic activities before and after precipitation, using to the equations below [

35]:

where:

Ap - activity after precipitation (U/mL)

Cpp - protein concentration after precipitation (g)

Aa - enzyme activity before precipitation (U/mL)

Cp - protein concentration before precipitation (g)

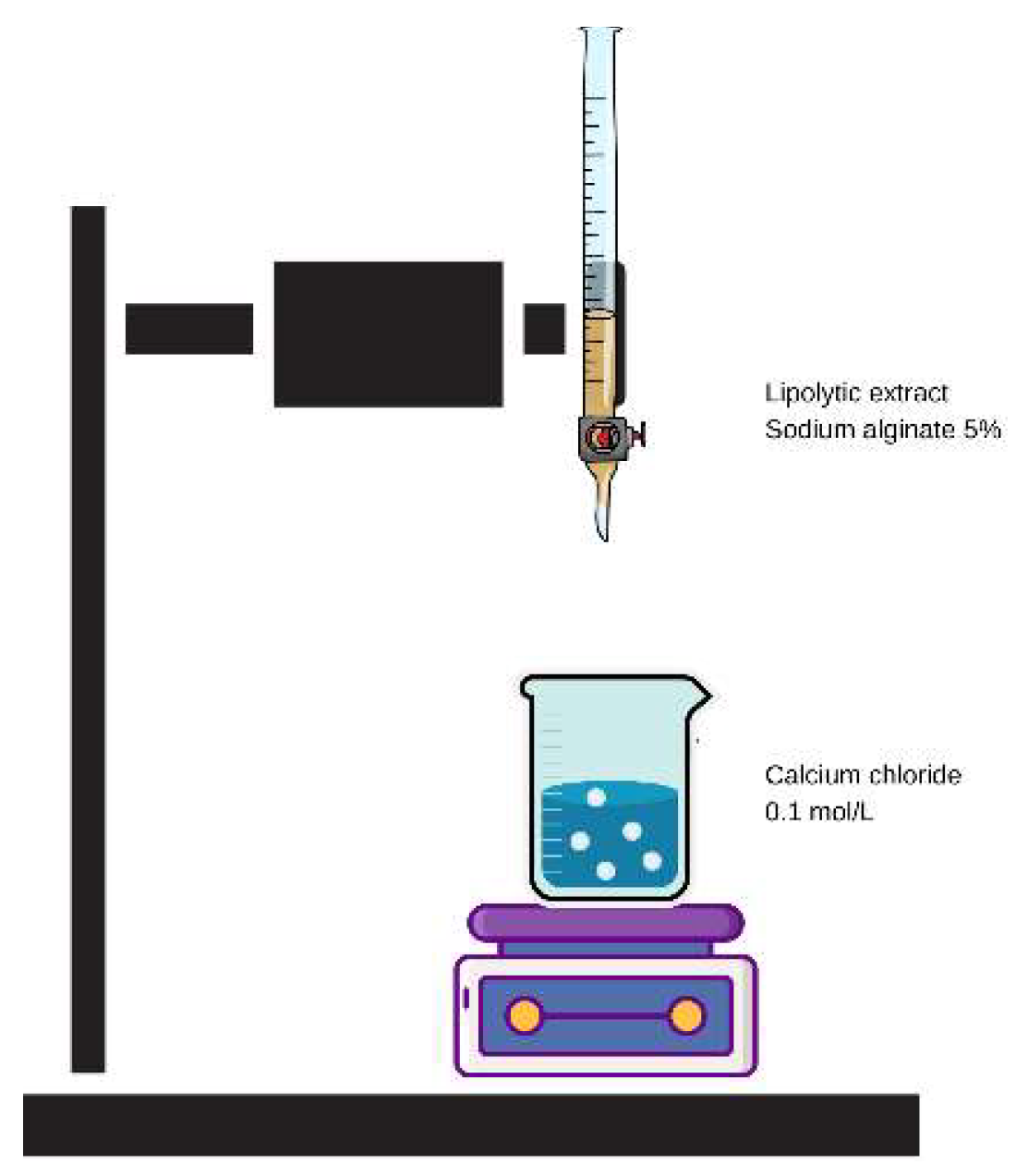

2.6. Immobilization in Calcium Alginate

For the immobilization in calcium alginate, the lipolytic extracts LE and PLE were added separately to 50 mL of a 5% sodium alginate solution. After homogenization, the particles were formed by dripping the aqueous solution of sodium alginate into a gelling solution of calcium chloride at 0.1 M. This process occurred with a flow rate of 3.0 mL/min, with a drop height of 24 cm and a particle immersion time of 1 h (

Figure 2). [

36].

2.7. Immobilization Yield

The immobilization yield (ƞ) was calculated based on the enzymatic activity obtained and the residual enzymatic activity present in the reaction medium after the immobilization process. The immobilization yield was calculated using Equation 4 [

37].

where:

U0: enzymatic activity obtained at the beginning of immobilization (U/g)

UF: residual enzyme activity present in supernatant after immobilization (U/g)

2.8. Enzyme Activity Recovered

The calculation of the recovered activity was determined by the relationship between the enzymatic activity of immobilized biocatalysts and the initial and final activities present in the supernatant, according to Equation 5 [

36].

where:

Us: enzyme activity of immobilized lipolytic extract (U/g)

U0: enzymatic activity obtained at the beginning of immobilization (U/g)

UF: residual enzyme activity present in supernatant after immobilization (U/g)

2.9. Thermal Stability of Immobilized Enzyme Extracts

Thermal stability was evaluated by incubating immobilized lipolytic extracts (ILE and IPLE) in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 7.0). The immobilized extracts were incubated for 24 h at different temperatures, ranging from 20 to 70 °C. For this, 5 mL of buffer were added to tubes containing 0.1 g of ILE or IPLE and kept under constant agitation (20 rpm) in an orbital shaker at study temperatures for 24 h. After the contact time, the tubes were centrifuged, and the supernatant was filtered. Enzyme activity was measured, and the proteins were quantified in the supernatant [

38]. The thermal stability of the non-immobilized lipolytic extract (LE) was also evaluated for the purpose of comparison.

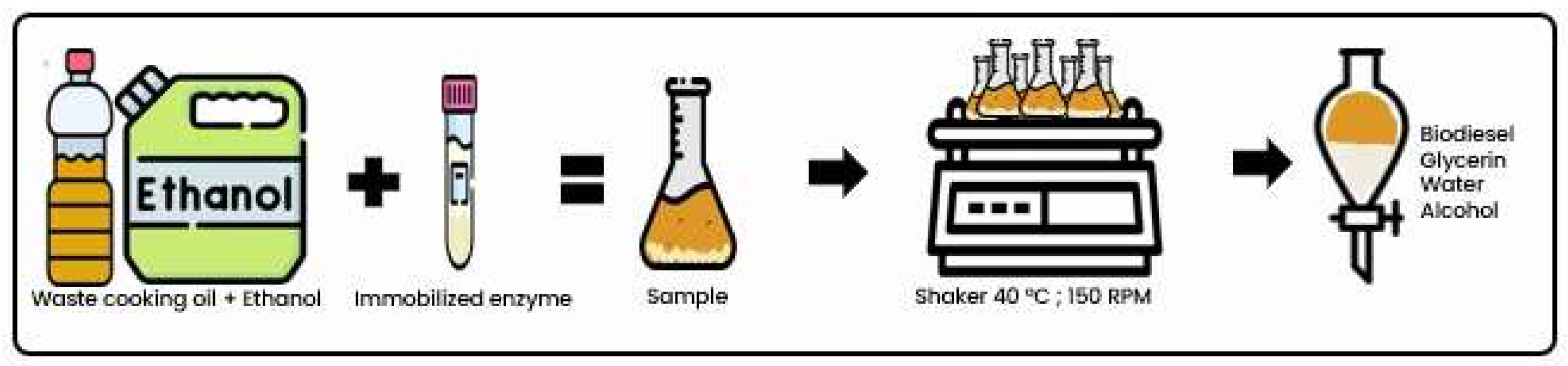

2.10. Enzymatic Transesterification—Biodiesel Production

Enzymatic transesterification was performed using the previously filtered waste cooking oil and ethanol. The reaction time was 360 min and the ethanol/oil ratio used was 3:1 [

6]. The immobilized biocatalyst was added to the reaction medium at a concentration of 3% (w/v) [

39,

40]. The reactions were conducted in an adapted bench reactor, with constant agitation at 150 rpm and a temperature of 40 °C. To adapt the reactor, the reagents were added to 250 mL borosilicate glass Erlenmeyer flasks and sealed. These bottles were then placed in a shaker incubator (TE-4200, Tecnal, Brazil) to control the temperature and agitation.

Figure 3 schematically illustrates the test procedure. Biodiesel production was also carried out with LE for the purpose of comparison.

For the purification of the biodiesel, at the end of the reaction, the mixture obtained was transferred to a separation funnel and allowed to stand for 24 h. After separation of the phases, the biodiesel was washed with water [

41] and used in the calculation of the yield and in the analysis via gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

2.11. Chromatographic Analysis

For the confirmation of the production of biodiesel, the methodology described by Naser et al. [

42] was used (with adaptations). An aliquot of 1.0 mL of acetone was added to 100 µL of the sample obtained after the purification process. The sample was then analyzed on a chromatograph (CG-7890B, Agilent Technologies, USA) coupled to a mass spectrometer (MS-5977a, Agilent Technologies, USA). The column used was a Carboxen 1010 (30 m x 0.53 mm). The drag gas was H

2 with a flow of 1.2 mL/min. The initial temperature of the column was 100 °C, maintained for 1 min, with a ramp rate of 5 °C/min up to 290 °C, and then remained at this temperature for another 21 min. The temperature of the injector and detector remained at 300 °C. The amount of sample injected was 3 µL. The resulting mass spectra were compared with those of the NIST Standard Reference Database 1A library. This comparison allowed the identification of the ethyl esters that were produced.

2.12. Biodiesel Yield

The yield of the biodiesel that was produced was calculated from the mass of biodiesel obtained after the transesterification reaction (m

biodisel) as a function of the mass of waste cooking oil (m

oil) used in the reaction (Equation 7) [

43,

44].

2.13. Reuse of Immobilized Biocatalyst

The reuse of the immobilized biocatalyst was evaluated through consecutive reactions of the biodiesel synthesis, reusing the IPLE and calculating the enzymatic activity at the end of each cycle, according to the aforementioned methodology. The retained enzyme activity was calculated according to Equation 6 [

45].

2.14. Physical-Chemical Characterization of Biodiesel

The biodiesel was characterized following the standards provided by ANP (Brazilian National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels) for the evaluation of quality parameters [

46]. The specific mass was determined using a 10 mL volumetric flask and an analytical balance [

47]. The kinematic viscosity was determined using a viscometer (0860R24, Quimis, Brazil) at 40 °C with the results expressed in mm

2/s [

47].

The flash point was obtained based on the ASTM D92 method [

48], in which biodiesel samples were placed in a porcelain crucible positioned over an asbestos screen that was heated using a Bunsen burner. The increase in the temperature of the biodiesel was monitored with the aid of a mercury thermometer, while a flame was passed over at every 1

oC increase in the temperature of the fuel. The determination of the acid index consisted of weighing 5 g of sample, followed by homogenization in ether: alcohol (2:1) v/v solution and titration, using a 0.1 M sodium hydroxide solution that was previously standardized [

49].

2.15. Statistical Analysis

The results were expressed as the mean and standard deviation and submitted to the analysis of normality and homogeneity of data, analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student’s T and Tukey tests (p<0.05). The data of the experimental design were analyzed with the aid of Statistica 10.0 software.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Lipase Production and Precipitation of the Enzymatic Extract

After 5 days of cultivation of the fungus

E. endophytica QAT_7AC, an enzyme production of 11,262 U/mL and a protein concentration of 1.72 mg/mL were obtained [

6]. This result is remarkable when compared to other studies [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54] and highlights the potential of this endophytic fungus as a source of lipase.

The precipitation of the LE using ethanol resulted in an increase in specific activity by 28%, with a recovery of 73.8% (

Table 1). Ethanol precipitation has previously been employed as an initial method of lipase purification. Zhu et al. [

55] employed this method in the first step of purifying the lipase produced by

Burkholderia gladioli and reported a 6.6% increase in specific enzyme activity. On the other hand, Preczeski et al. [

56] observed a 90% increase in specific activity and a purification factor of 9.82 for a lipase produced by

Aspergillus niger after the addition of salt and precipitation with ethanol. Therefore, ethanol precipitation proves to be effective in terms of increasing lipase enzymatic activity and stands out as a simple and efficient approach for the pre-purification of this enzyme.

3.2. Enzyme Immobilization

Enzyme immobilization is an important strategy to enable the stability and reuse of biocatalysts [

25,

26]. With the immobilization of the LE, approximately 520 calcium alginate beads were produced. Each sphere weighed 30 mg on average and had a diameter of 6 mm. After 24 h of production of the beads, it was possible to observe that the immobilization efficiency reached 89.7%, with retention of 67% of its initial enzymatic activity. When the PLE was immobilized in calcium alginate, 848 beads were produced, each with an average weight of 15 mg and a diameter of 7 mm. The immobilization yield was 92.26%, with 100% recovery of the initial lipase activity. These results are in line with other studies that used calcium alginate in lipase immobilization (

Table 2).

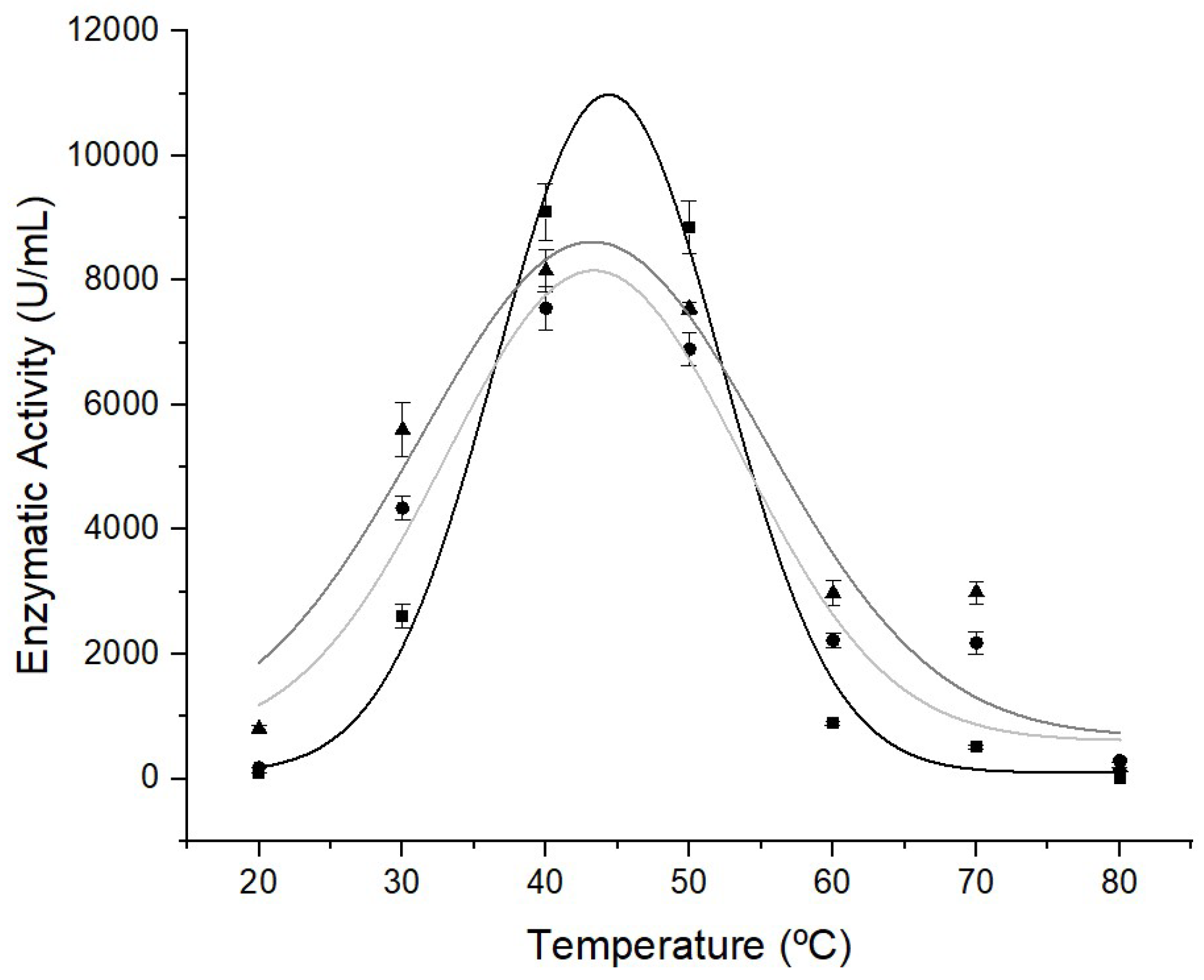

3.3. Thermal Stability of the Biocatalysts

The thermal stability of the lipolytic extract (LE) and immobilized extracts (ILE and IPLE) are shown in

Figure 4. When evaluating the thermal stability of lipolytic extracts produced by

E. endophytica, an increase in lipase activity is observed as the temperature increases, with maximum enzymatic activity recorded between 40 and 50 °C (

Figure 4). This result corroborates those of other studies that also report an ideal temperature of 40-60 °C for free and immobilized lipase in different supports [

62,

63,

64,

65]. The immobilized extracts (ILE and EPLE) maintained the enzymatic activity at a higher temperature range, between 30 and 50 °C, when compared to LE. Therefore, greater resistance of the enzyme to thermal denaturation is observed after its immobilization in alginate beads. In contrast, the further increase in temperature to over 55 °C resulted in a marked decrease in lipase activity. At 80 °C, none of the extracts showed enzymatic activity.

The use of the Gaussian model made it possible to construct a curve and formulate an equation that describes the enzymatic behavior at different temperatures. Mathematical models, such as the Gaussian model, are essential tools for predicting enzyme performance, as they provide a detailed representation of how enzyme activity varies in response to temperature changes. Through the equation used, it was possible not only to confirm the enzyme’s stability, but also identify the specific temperature at which each of the lipolytic extracts reached its highest enzymatic activity. This information is crucial for optimizing operating conditions and improving the control of enzymatic reactions in industrial applications. The derived equations are presented below. Equations 8, 9 and 10 describe the mathematical adjustment for the thermal stability of LE, ILE and IPLE, respectively:

3.4. Biodiesel Production

The parameters used for the production of biodiesel were defined from the experimental design carried out in a previous study [

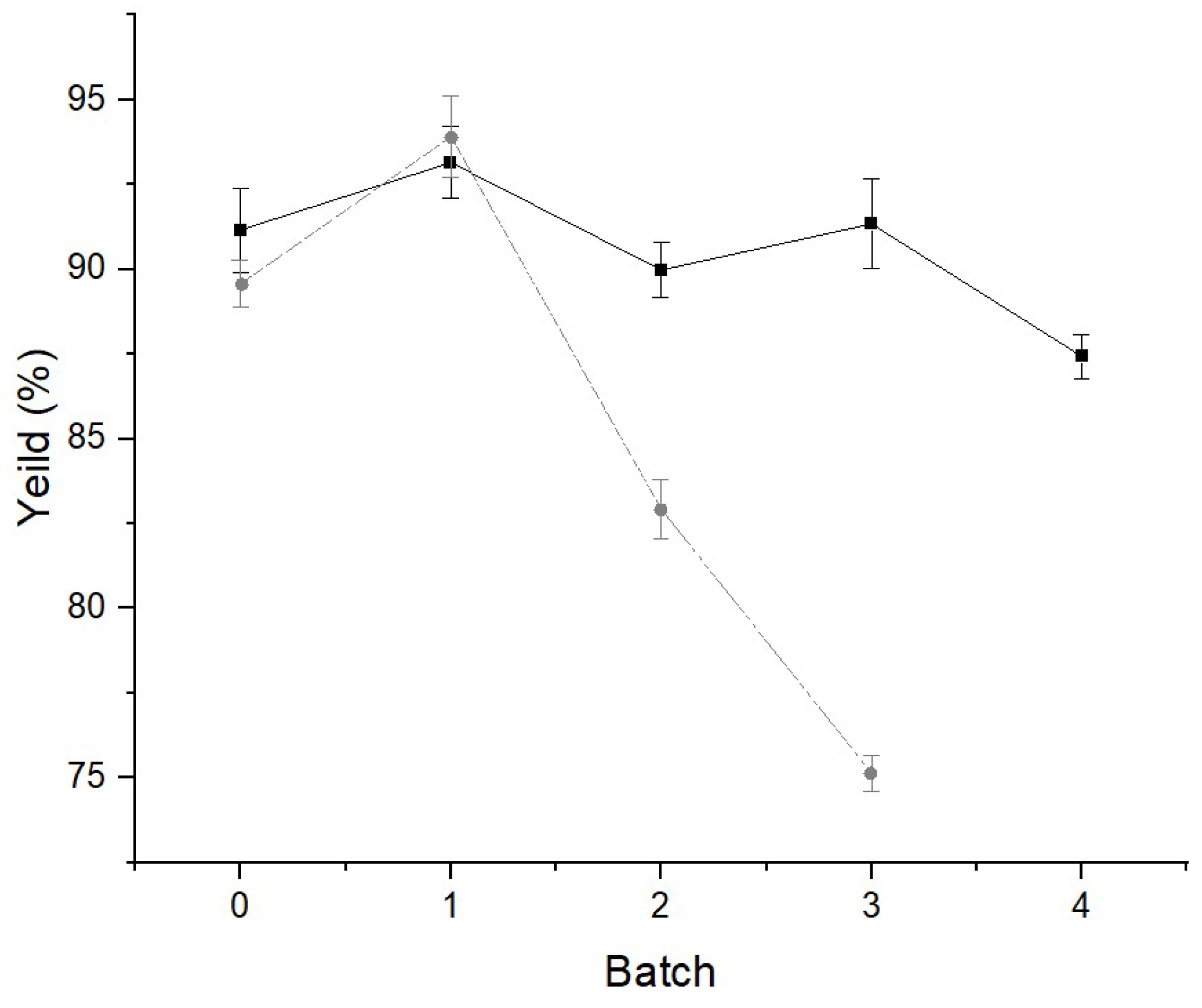

6], in which we analyzed the influence of different experimental conditions on the yield of biodiesel produced by enzymatic esterification of waste cooking oil. The yields obtained to produce biodiesel with the ILE and with the IPLE, after four reaction cycles are shown in

Figure 5.

As shown in

Figure 5, the first aspect to be pointed out is the increase in biodiesel yield when employing immobilized biocatalysts, compared to lipolytic extracts used in free form. Other studies have also proven the increase in biodiesel yield when using the immobilized enzyme compared to the free enzyme [

61,

66,

67].

Yields remained above 75% in three reaction cycles when using the ILE, with a decrease in efficiency of around 20% compared to the first cycle. When using the IPLE, the yield remained above 87% after 4 cycles, reducing less than 10% when compared to the first reaction cycle. However, the enzymatic activity of the IPLE decreased by about 90% in the last reaction cycle, leading to the termination of the use of the biocatalyst. This drop in the enzyme activity was also observed by Knezevic et al. [

61], who used lipase from

Candida rugosa that was immobilized in calcium alginate for six cycles for the production of biodiesel, with a reduction in enzyme activity of 83.3% at the end of the sixth cycle.

On the other hand, Bhushan et al. [

66] immobilized the lipase produced by

Arthrobacter sp. in calcium alginate and reused it for 10 cycles in the hydrolysis of triacylglycerides. The immobilized enzyme showed an increase in thermal, pH and storage stability when compared to the free enzyme. Vetrano et al. [

58] demonstrated excellent recyclability of lipase from

C. rugosa immobilized in alginate, with a residual enzymatic activity of greater than 80% in the tenth reaction cycle. Zhong et al. [

67] investigated the use of the enzyme immobilized in alginate in up to six cycles in hydrolysis reactions. Therefore, it can be observed that the reuse of immobilized lipolytic extracts of

E. endophytica can still be improved and new studies are necessary. However, it is important to highlight that we used the crude extract and the precipitated extract in immobilization, which possibly influenced the results, especially when compared to other studies that used the immobilized purified enzyme [

67,

68,

69].

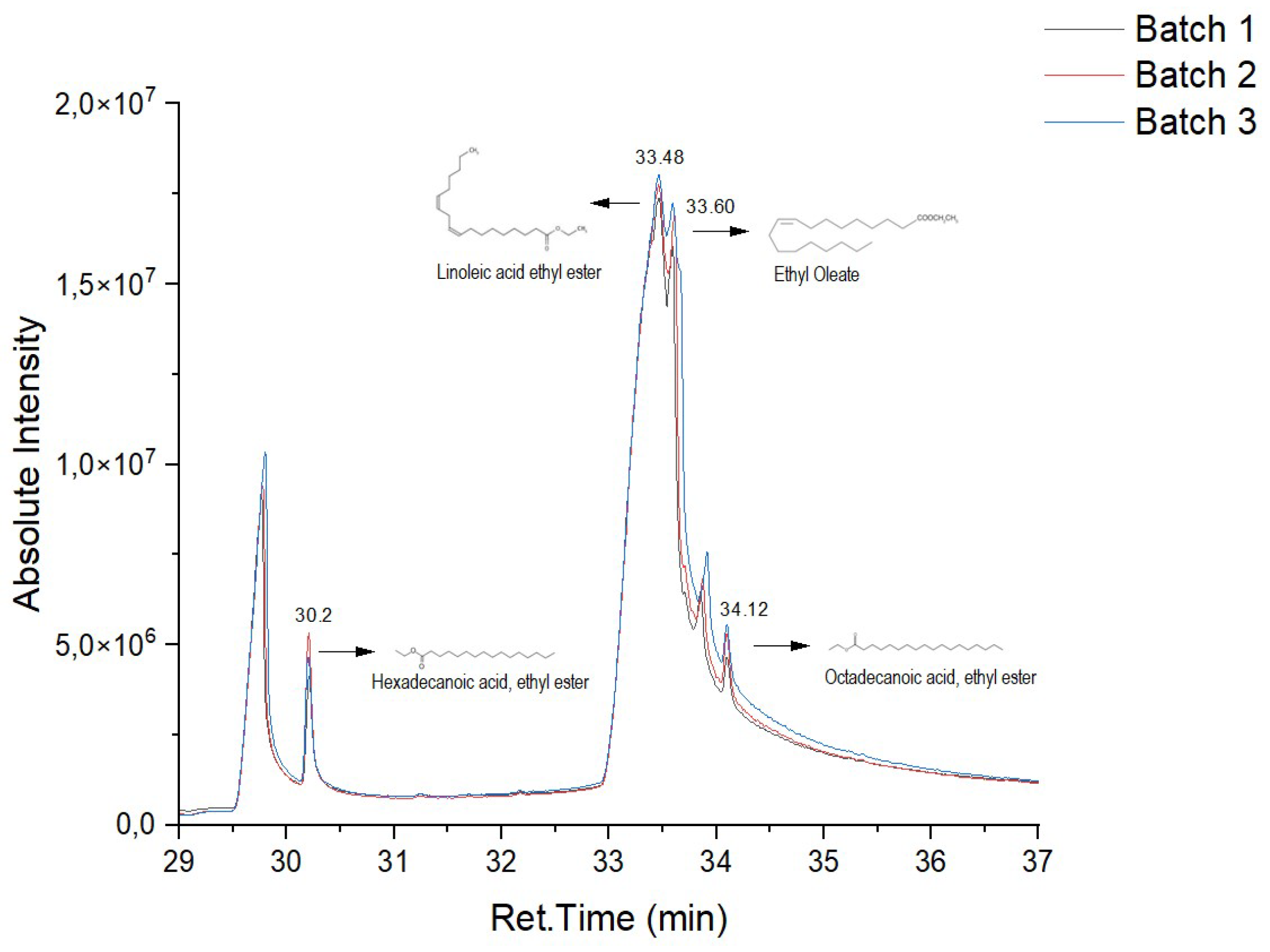

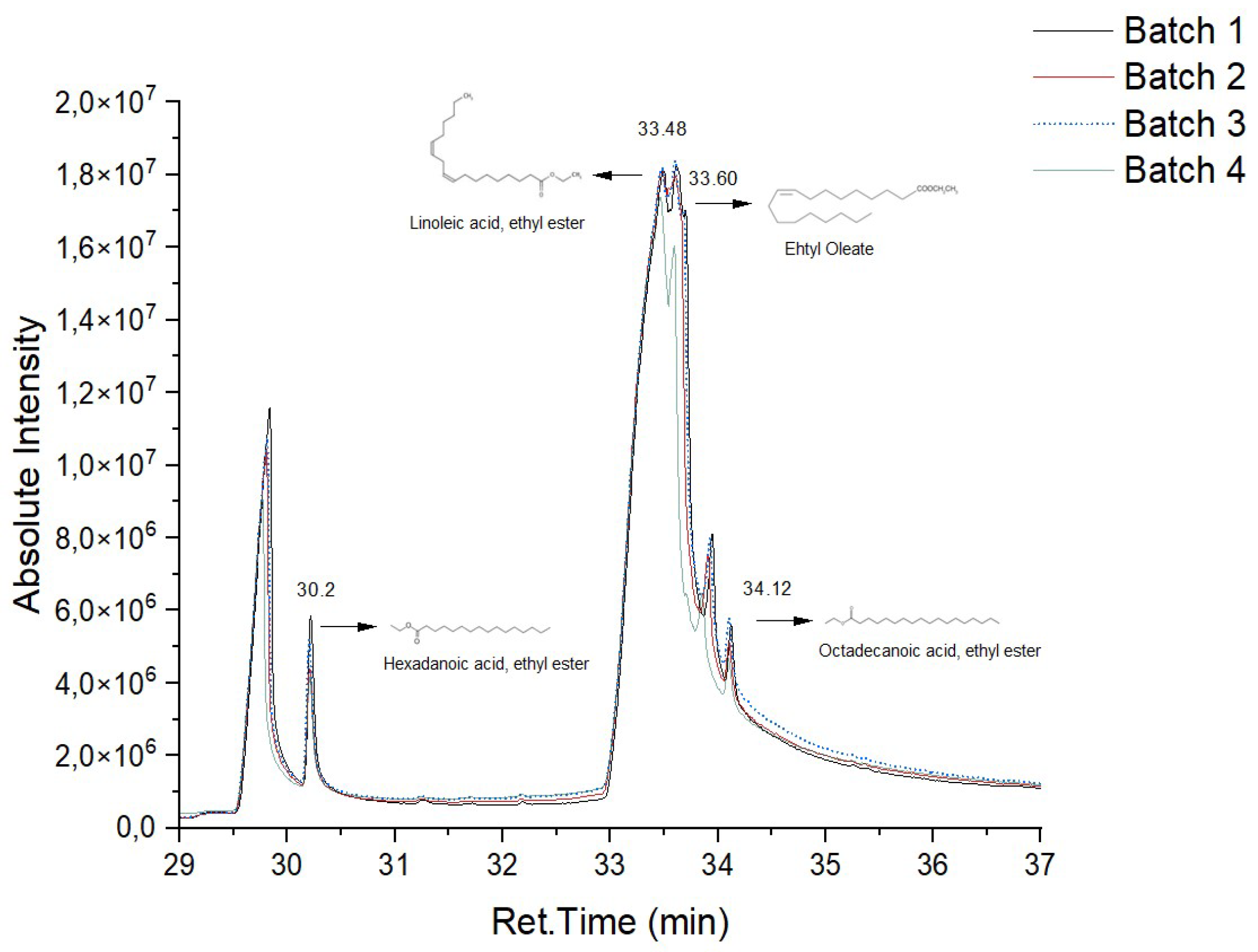

In

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, it is possible to observe the chromatograms of the biodiesel samples obtained from the enzymatic transesterification of the waste cooking oil with ethanol, using the ILE and IPLE, respectively.

In both the biocatalysts, linoleic acid ester (retention time = 33.48 min) was produced in greater quantity, followed by oleic acid ester (retention time = 33.60 min). It was also possible to identify the palmitic acid ester (retention time = 30.20) and, to a lesser extent, the stearic acid ester (retention time = 34.12 min). These results are in line with those obtained in a previous study, where the LE of

E. endophytica was used in the production of biodiesel in free form [

6].

3.5. Physical-Chemical Characterization of Biodiesel

Table 3 presents the properties of the biodiesel produced with the LE, ILE or IPLE, and the respective specifications of the ANP [

46]. It is observed that the biodiesel produced via the enzymatic transesterification process with the LE is within the limits established by the standards for most of the properties. The values of specific gravity and kinematic viscosity indicate good lubricating properties for the biodiesel produced. The high flash point (143 °C) ensures safer storage and transport of the fuel. However, the ester content was below that specified by the ANP, indicating the need to increase the reaction time, since there are still free fatty acids to be converted into product. The excess of free fatty acids was also confirmed by the high acidity index, which also did not meet the standard stipulated by the norm. Thus, further studies should be carried out so that the parameters outside the established limits are within what is set out by the legislation, thereby guaranteeing a high-quality biodiesel that is suitable for use in diesel engines [

70].

5. Conclusions

From the results obtained, it can be observed that the Amazonian endophytic fungus E. endophytica QAT_7AC is a promising source of lipase, an enzyme of great interest for various industrial applications. The lipolytic extract produced by this fungus, both in crude form and when precipitated with ethanol, was effectively immobilized in calcium alginate, with a high recovered enzymatic activity. The biocatalysts were shown to be able to act in the transesterification of waste cooking oil for the production of biodiesel, allowing up to four reaction cycles and meeting most of the quality specifications provided by the ANP. However, in order for this process to be optimized, and for the biodiesel produced to fully meet the ANP standards, additional studies are needed. These studies should focus on improving the recycling of biocatalysts, increasing the number of viable reaction cycles and maximizing the efficiency of the biodiesel production process, thus ensuring a fully sustainable and economically viable approach to the production of biofuels from waste cooking oil and ethanol.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.A., J.G.C.R. and S.D.J; investigation, J.G.C.R. and F.V.C.; methodology: J.G.C.R., P.M.A., S.D.J; formal analysis, P.M.A., N.T.M. and S.D.J.; data curation, J.G.C.R.; validation, J.G.C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.C.R.; writing—review and editing, P.M.A.; N.T.M.; project administration, P.M.A. and S.D.J.; resources: P.M.A. and S.D.J.; funding acquisition, P.M.A and S.D.J. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Amazonas (FAPEAM) (grant number 01.02.016301.00568/2021-05 and 062.00165/2020), by POSGRAD/FAPEAM 2022 and by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) (finance code 001 and grant number 88881.510151/2020-01 - PDPG Amazônia Legal). The APC was funded by Universidade do Estado do Amazonas (UEA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Universidade do Estado do Amazonas - UEA, FAPEAM and CAPES for supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kiehbadroudinezhad, M.; Merabet, A.; Ghenai, C.; Abo-Khalil, A.G.; Salameh, T. The role of biofuels for sustainable MicrogridsF: A path towards carbon neutrality and the green economy. Heliyon 2023, 9, 13407. [CrossRef]

- Shirneshan, A. HC, CO, CO2 and NOx emission evaluation of a diesel engine fueled with waste frying oil methyl ester. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 75, 292–297. [CrossRef]

- Touqeer, T.; Mumtaz, M.W.; Mukhtar, H.; Irfan, A.; Akram, S.; Shabbir, A.; Rashid, U.; Nehid, I.A.; Choong, T.S.Y. Fe3O4-PDA-Lipase as Surface Functionalized Nano Biocatalyst for the Production of Biodiesel Using Waste Cooking Oil as Feedstock: Characterization and Process Optimization. Energies 2019, 13, 177. [CrossRef]

- Farouk, S.M.; Tayeb, A.M.; Abdel-Hamid, S.M.S.; Osman, R.M. Recent advances in transesterification for sustainable biodiesel production, challenges, and prospects: a comprehensive review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 12722-12747. [CrossRef]

- Nazloo, E.K.; Moheimani, N.R.; Ennaceri, H. Graphene-based catalysts for biodiesel production: Characteristics and performance. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 10, 160000. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.G.C.; Cardoso, F.V.; Santos, C.C.; Matias, R.R.; Machado, N.T.; Duvoisin Junior, S.; Albuquerque, P.M. Biocatalyzed Transesterification of Waste Cooking Oil for Biodiesel Production Using Lipase from an Amazonian Fungus Endomelanconiopsis endophytica. Energies 2023, 16, 6937. Doi: 10.3390/en16196937.

- Tabatabaei, M.; Aghbashlo, M.; Dehhaghi, M.; Panahi, H.K.S.; Mollahosseini, A.; Hosseini, M.; Soufiyan, M.M. Reactor tchnologies for biodiesel production and processing: A review. Prog. Energy Comb. Sci. 2019, 74, 239-303. [CrossRef]

- Rathore, D.; Sevda, S.; Prasad, S.; Venkatramanan, V.; Chandel, A.K.; Kataki, R.; Bhadra, S.; Channashettar, V.; Bora, N.; Singh, A. Bioengineering to Accelerate Biodiesel Production for a Sustainable Biorefinery. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 618. [CrossRef]

- Alagumalai, A.; Mahian, O.; Hollmann, F.; Zhang, W. Environmentally benign solid catalysts for sustainable biodiesel production: A critical review. Sci Total Environ. 2021, 10; 144856. [CrossRef]

- Notarnicola, B.; Tassielli, G.; Renzulli, P.A.; Di Capua, R.; Astuto, F.; Riela, S.; Nacci, A.; Casiello, M.; Testa, M.L.; Liotta, L.F.; Pastore, C. Life Cycle Assessment of a system for the extraction and transformation of Water Treatment Sludge (WWTS)-derived lipids into biodiesel. Sci. Total Environ. 2023. 20, 883-163637. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Feng, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Bilal, M.; Lv, H.; Jia, S.; Cui, J. Production and use of immobilized lipases in/on nanomaterials: A review from the waste to biodiesel production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 1, 207-222. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kadmy, I.M.S.; Aziz, S.N.; Hussein, N.H.; El-Shafeiy, S.N.; Hamzah, I.H.; Suhail, A.; Alhomaidi, E.; Algammal, A.M.; El-Saber Batiha, G.; El Badre, H.M.; Hetta, H.F.; Sequencing analysis and efficient biodiesel production by lipase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 323. [CrossRef]

- Ben Bacha, A.; Alonazi, M.; Alharbi, M.G.; Horchani, H.; Ben Abdelmalek, I. Biodiesel Production by Single and Mixed Immobilized Lipases Using Waste Cooking Oil. Molecules. 2022, 27, 8736. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, G.M.; Raina, D.; Narisetty, V.; Kumar, V.; Saran, S.; Pugazhendi, A.; Sindhu, R.; Pandey, A.; Binod, P. Recent advances in biodiesel production: Challenges and solutions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 148751. [CrossRef]

- Mahfoudhi, A.; Benmabrouk, S.; Fendri, A.; Sayari, A. Fungal lipases as biocatalysts: A promising platform in several industrial biotechnology applications. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2022, 119, 3370-3392. [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.P.; Quilles Junior, J.C.; Ohe, T.H.K.; Ferrarezi, A.L.; Nunes, C.D.C.C.; Boscolo, M.; Gomes, E.; Bocchini, D.A.; da Silva, R. Free and Substrate-Immobilised Lipases from Fusarium verticillioides P24 as a Biocatalyst for Hydrolysis and Transesterification Reactions. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2021, 193, 33-51. [CrossRef]

- Malewska, E.; Kurańska, M.; Tenczyńska, M.; Prociak, A. Application of Modified Seed Oils of Selected Fruits in the Synthesis of Polyurethane Thermal Insulating Materials. Materials 2023, 17, 158. [CrossRef]

- Lotti, M.; Pleiss, J.; Valero, F.; Ferrer, P. Enzymatic Production of Biodiesel: Strategies to Overcome Methanol Inactivation. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, 1700155. [CrossRef]

- Zulqarnain; Yusoff, M.H.M.; Ayoub, M.; Ramzan, N.; Nazir, M.H.; Zahid, I.; Abbas, N.; Elboughdiri, N.; Mirza, C.R.; Butt, T.A. Overview of Feedstocks for Sustainable Biodiesel Production and Implementation of the Biodiesel Program in Pakistan. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 19099-19114. [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.C.D.; Ferdaus, M.J.; Foguel, A.; da Silva, T.L.T. Oleogels as a Fat Substitute in Food: A Current Review. Gels 2023, 9, 180. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, D.; Yu, A. Engineering the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica to produce limonene from waste cooking oil. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2019, 12, 241. [CrossRef]

- Wancura, J.H.C.; Tres, M.V.; Jahn, S.L.; de Oliveira, J.V. Lipases in liquid formulation for biodiesel production: Current status and challenges. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2020, 67, 648-667. [CrossRef]

- Mandari, V.; Devarai, S.K. Biodiesel Production Using Homogeneous, Heterogeneous, and Enzyme Catalysts via Transesterification and Esterification Reactions: a Critical Review. Bioenergy Res. 2022, 15, 935-961. [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.K.; Lee, K.T.; Mohamed, A.R. Homogeneous, heterogeneous and enzymatic catalysis for transesterification of high free fatty acid oil (waste cooking oil) to biodiesel: a review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 500-18. [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.; Meng, X.; He, J.; Sun, P.; Analysis of immobilized Candida rugosa lipase catalyzed preparation of biodiesel from rapeseed soapstock, Food Bioprod. Proces. 2008, 86, 283-289. [CrossRef]

- Bergamasco, J. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) Microspheres and Their Use as Supports for Immobilization of Lipase Produced by Rhizomucor miehei and Its Catalytic Study in the Transesterification Reaction of Soybean Oil for Biodiesel Production via the Ethyl Route. Master thesis. São Paulo State University Julio de Mesquita Filho. Institute of Biosciences, Letters, and Exact Sciences of São José do Rio Preto, Brazil, 2013.

- Bilal, M.; Fernandes, C.D.; Mehmood, T.; Nadeem, F.; Tabassam, Q.; Ferreira L.F.R.; Immobilized lipases-based nano-biocatalytic systems - A versatile platform with incredible biotechnological potential. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 175, 108-122. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves Filho, D.; Silva, A.G.; Guidini, C.Z. Lipases: sources, immobilization methods, and industrial applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 7399-7423. [CrossRef]

- Matias, R.R.; Rodrigues, J.G.C.; Procópio, R.E.L.; Matte, C.R.; Duvoisin Junior, S.; Soares, R.M.D.; Albuquerque, P.M. Lipase production from Aniba canelilla endophytic fungi, characterization and application of the enzymatic extract. Res. Soc. Develop. 2022, 11, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Gurgel, R.S.; Rodrigues, J.G.C.; Matias, R.R.; Batista, B.N.; Oliveira, R.L.; Albuquerque, P. M. Biological activity and production of metabolites from Amazon endophytic fungi. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 14, 85-93. [CrossRef]

- Winkler, U.K.; Stuckmann, M. Glycogen, hyaluronate and some other polysaccharides greatly enhance the formation of exolipase by Serratia marcescens. J. Bacteriol. 1979, 138, 663-670. Doi: jb.138.3.663-670.1979.

- Tombini, J. Selection of lipolytic microorganisms and lipase production from soy processing by products. Master thesis. Federal Technological University of Paraná, Pato Branco, Brazil, 2015.

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248. [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.A.L.; Farinas, C.S.; Miranda, E.A. Ethanol precipitation as a downstream processing step for concentration of xylanases produced by submerged and solid-state fermentation. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 35, 477-488. [CrossRef]

- Manera, A.P.; Meinhardt, S.; Kalil, S.J. Purification of amyloglucosidase from Aspergillus niger. Semina: Ciências Agrárias 2011, 32, 651-658. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, V.F.T.; Pereira, N.R.; Waldman, W.R.; Ávila, A.L.C.D.; Pérez, V.H.; Rodríguez, R.J.S. Ion exchange kinetics of magnetic alginate ferrogel beads produced by external gelation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 111, 198–205. [CrossRef]

- Bindu, V.U.; Shanty, A.A.; Mohanan, P.V. Parameters affecting the improvement of properties and stabilities of immobilized α-amylase on chitosan-metal oxide composites. Int. J. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 6, 44-57. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Lou, D.; Tan, J.; Zhu, L. The effects of macromolecular crowding and surface charge on the properties of an immobilized enzyme: activity, thermal stability, catalytic efficiency and reusability. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 38028–38036. [CrossRef]

- Cruz J. Immobilization of Candida antarctica B lipase on chitosan for biodiesel production by transesterification of castor oil. Master thesis. Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Brazil, 2007.

- Marder, F.; Celin, M.M.; Mazuim, M.S.; Schneider, R.C.S.; Macagnan, M.T.; Corbellini, V.A. Biodiesel production by biocatalysis using an alternative method of lipase immobilization in hydrogel. Tecno-Lógica. 2008, 12, 56-64.

- Atadashi, I.M.; Aroua, M.K.; Aziz, A.A. Biodiesel separation and purification: A review. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 437–443. [CrossRef]

- Naser, J.; Avbenake, O.P.; Dabai, F.N.; Jibril, B.Y. Regeneration of spent bleaching Earth and conversion of recovered oil to Biodiesel. Waste Menage. 2021, 126, 258-265. [CrossRef]

- Parandi, E.; Safaripour, M.; Abdellatif, M.H.; Saidi, M.; Bozorgian, A.; Nodeh, H. R.; Rezania, S. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil using a novel biocatalyst of lipase enzyme immobilized magnetic nanocomposite. Fuel 2022, 313, 123057. [CrossRef]

- Jamil, N.; Zairi, M.N.M.; Nasim, N.A.M.; Pa’ee, F. Influences of Enviromental Conditions to Phytoconstituents in Clitoria ternatea (Butterfly Pea Flower) – A review. J. Sci. Technol. 2018, 10, 208-228. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.A.; Macedo, G.P.; Rodrigues; D.S.; Giordano, R.L.C.; Gonçalves, L.R.B. Immobilization of Candida antarctica lipase B by covalent attachment on chitosan-based hydrogels using different support activation strategies. 2012, 60, 16–24. [CrossRef]

- ANP. National Agency of Petroleum. (2004). ANP Resolution 42/2004. Available at www.anp.gov.br/petro/legis_qualidade.asp. Accessed on 07/06/24.

- Battisti, G.; Seabra Junior, E.; Pozzo, D. M.; Santos, R. F. Comparison of the Physicochemical Characteristics of Citronella and Eucalyptus Biodiesel with Soybean Biodiesel. II Seminar on Energy Engineering in Agriculture, Acta Iguazu. 2017, 6, 173-180.

- ASTM: American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM D92-18, Flash and Fire Points by Cleveland Open Cup Tester. vol:05.01, ASTM International, 2018.

- Instituto Adolfo Lutz. Métodos Físico-Químicos para Análise de Alimentos. São Paulo: Instituto Adolfo Lutz, 2008.

- Sopalun, K.; Laosripaiboon, W.; Wachirachaikarn, A.; Iamtham, S. Biological potential and chemical composition of bioactive compounds from endophytic fungi associated with thai mangrove plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 141, 66-76. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.F.; Silva, M.R.L.; Hirata, D.B. Production of new lipase from Preussia africana and a partial characterization. Prep. Biochem. Biotechno. 2021, 52, 942-949. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, K.S.C.; Queiroz, M.S.R.; Gomes, B.S.; Dallago, R.; Souza, R.O.M.A.; Guimarães, D.O.; Itabaiana Jr., I.; Leal, I.C.R. Lipases of endophytic fungi Stemphylium lycopersici and Sordaria sp.: Application in the synthesis of solketal derived monoacylglycerols. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2020, 142, 109664. [CrossRef]

- Sena, I.S.; Ferreira, A.M.; Marinho, V.H.; Holanda, F.H.; Borges, S.F.; Souza, A.A.; Koga, R.C.R.; Lima, A.L.; Florentino, A.C.; Ferreira, I.M. Euterpe oleracea Mart (Açaizeiro) from the Brazilian Amazon: A Novel Font of Fungi for Lipase Production. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2394. [CrossRef]

- Rana Q.U.A.; Irfan, M.; Ahmed, S.; Hasan, F.; Shah, A.A.; Khan, S.; Rehman, F.U.; Khan, H.; Ju, M.; Li, W.; Badshah, M. Bio-catalytic transesterification of mustard oil for biodiesel production. Biofuels 2019, 69-76. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J, Liu Y, Qin Y, Pan L, Li Y, Liang G, Wang Q. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Bacterium Burkholderia gladioli Bsp-1 Producing Alkaline Lipase. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1043-1052. Doi: 10.4014/jmb.1903.03045.

- Preczeski, K.P.; Kamanski, A.B.; Scapini, T.; Camargo, A.F.; Modkoski, T.A.; Rosseto, V.; Venturin, B.; Mulinari, j.; Golunski, S.M.; Mossi, T.A.; Treichel, H. Efficient and Low-Cost Alternative for Lipase Concentration Aimed at Application in the Treatment of Residual Kitchen Oils. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 41, 851–857. [CrossRef]

- Ghattas. N.; Filice, M.; Abidi, F.; Guisan, J.M.; Ben, A. Purification and improvement of the functional properties of Rhizopus oryzae lipase using immobilization techniques. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enz. 2014, 110, 111-116. [CrossRef]

- Vetrano, A.; Gabriele, F.; Germani, R.; Spreti, N. Characterization of lipase from Candida rugosa entrapped in alginate beads to enchance its thermal stability and recyclability. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 10037. [CrossRef]

- Sari, A.N.M.; Koentjoro, M.P.; Prasetyo, E.N. Lipase Immobilization based on biopolymer. In: Surabaya International Health Conference, Surabaya. Empowering Community For Health Status Improvement, Surabaya, 2019.

- Pereira, A.S; Miranda, S.M; Lopes, M.; Belo, I. Factors affecting microbial lipids production by Yarrowi lipolytica strains from volatile fatty acids: Effect of co-substrates, operation mode and oxygen. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 331, 37-47. [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, Z.; Bobic, S.; Milutinovic, A.; Obradovic, B.; Mojovic, L.; Bugarski, B. Alginate-immobilized lipase by electrostatic extrusion for the purpose of palm oil hydrolysis in lecithin/isooctane system. Proc. Biochem. 2002, 32, 313-318. [CrossRef]

- Adetunji, A.I.; Olaniran, A.O. Immobilization and characterization of lipase from an indigenous Bacillus aryabhattai SE3-PB isolated from lipid-rich wastewater. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 48, 898-905. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.S.; Diniz, M.M.; Jong, G.; Gama Filho, H.S.; dos Anjos, M.J.; Finotelli, P.V.; Fontes-Sant’Ana, G.C.; Amaral, P.F.F. Chitosan-alginate beads as encapsulating agents for Yarrowia lipolytica lipase: Morphological, physico-chemical and kinetic characteristics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 139, 621-630. [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.H.; Yang, K.L. Lipase in biphasic alginate beads as a biocatalyst for esterification of butyric acid and butanol in aqueous media. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2016, 82, 173-179. [CrossRef]

- Colla, L.M.; Ficanha, A.M.M.; Rizzardi, J.; Bertolin, T.E.; Reinehr, C.O.; Costa, J.A.V. Production and Characterization of Lipases by Two New Isolates of Aspergillus through Solid-State and Submerged Fermentation. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 25959. [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, I.; Parhad, R.; Qazi, G. N. Immobilization of lipase by entrapment in Ca-alginate beads. J. Bioac. Compat. Polym. 2008, 23, 552-562. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Feng, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Bilal, M.; Lv, H.; Jia, S.; Cui, J. Production and use of immobilized lipases in/on nanomaterials: A review from the waste to biodiesel production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 152, 207-222. [CrossRef]

- Poppe, J.K.; Matte, C.R.; Peralba, M.C.R.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Ayub, M.A.Z. Optimization of ethyl ester production from olive and palm oils using mixtures of immobilized lipases. Appl. Cat. A-Gen., 2015, 490, 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Alnoch, R.C.; Santos, L.A.; Almeida, J.M.; Krieger, N.; Mateo, C. Recent trends in biomaterials for immobilization of lipases for application in non-conventional media. Catalysts 2020, 10, 697. [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Sen, R. Fuel properties, engine performance and environmental benefits of biodiesel produced by a green process. Appl. Energy 2013, 105, 319-326. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).