Submitted:

08 August 2024

Posted:

09 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

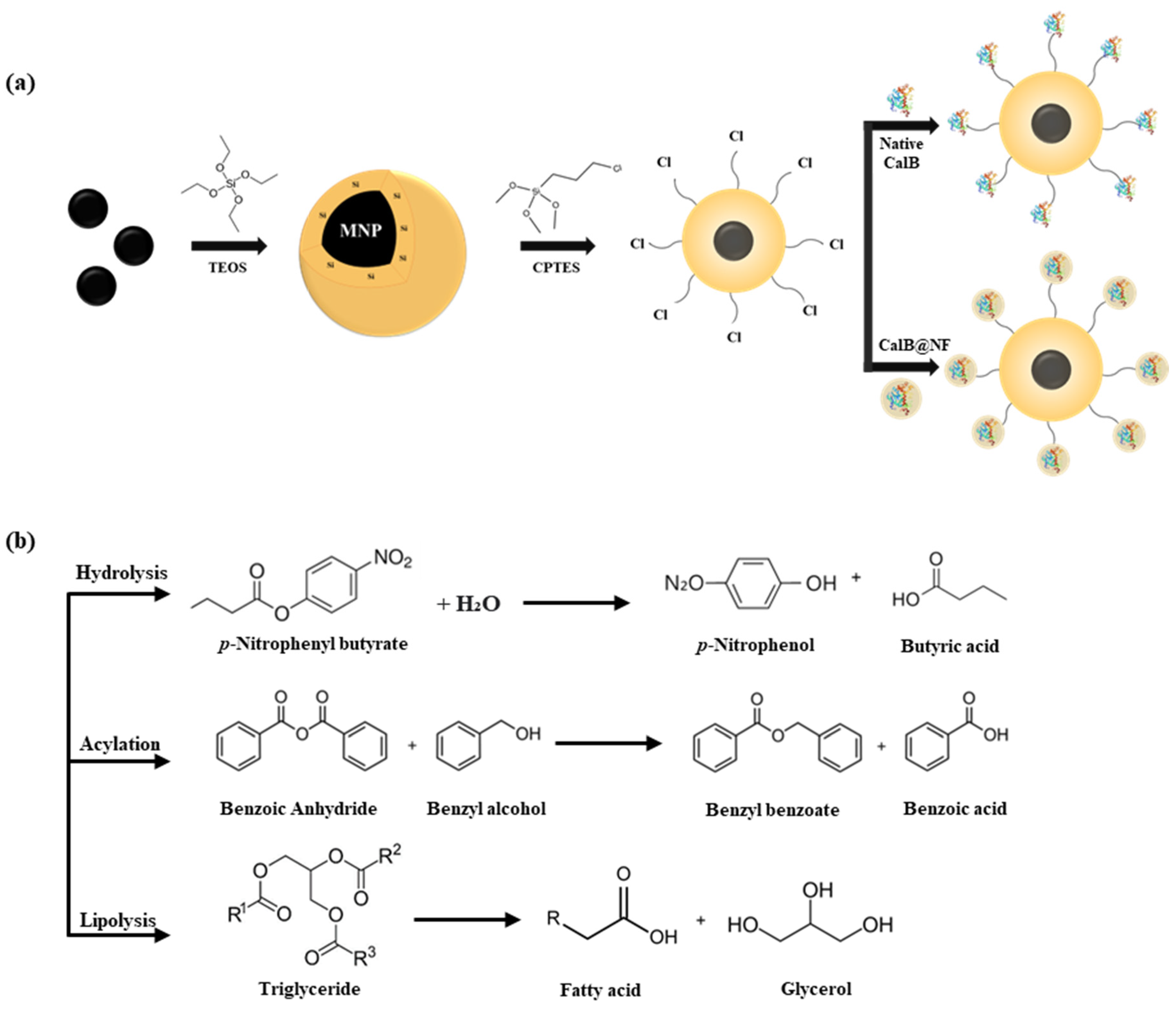

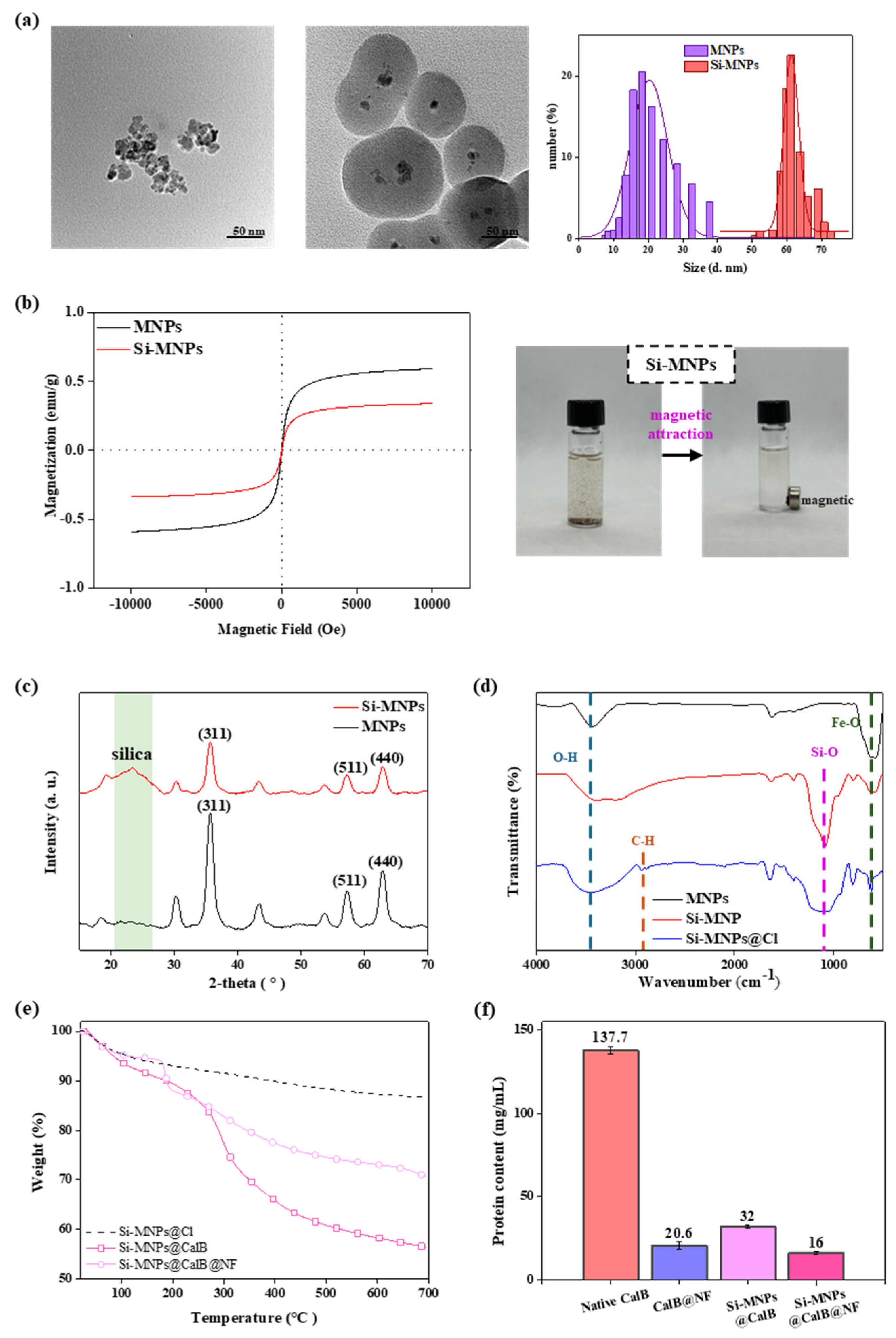

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of Si-MNPs and Si-MNPs@Cl

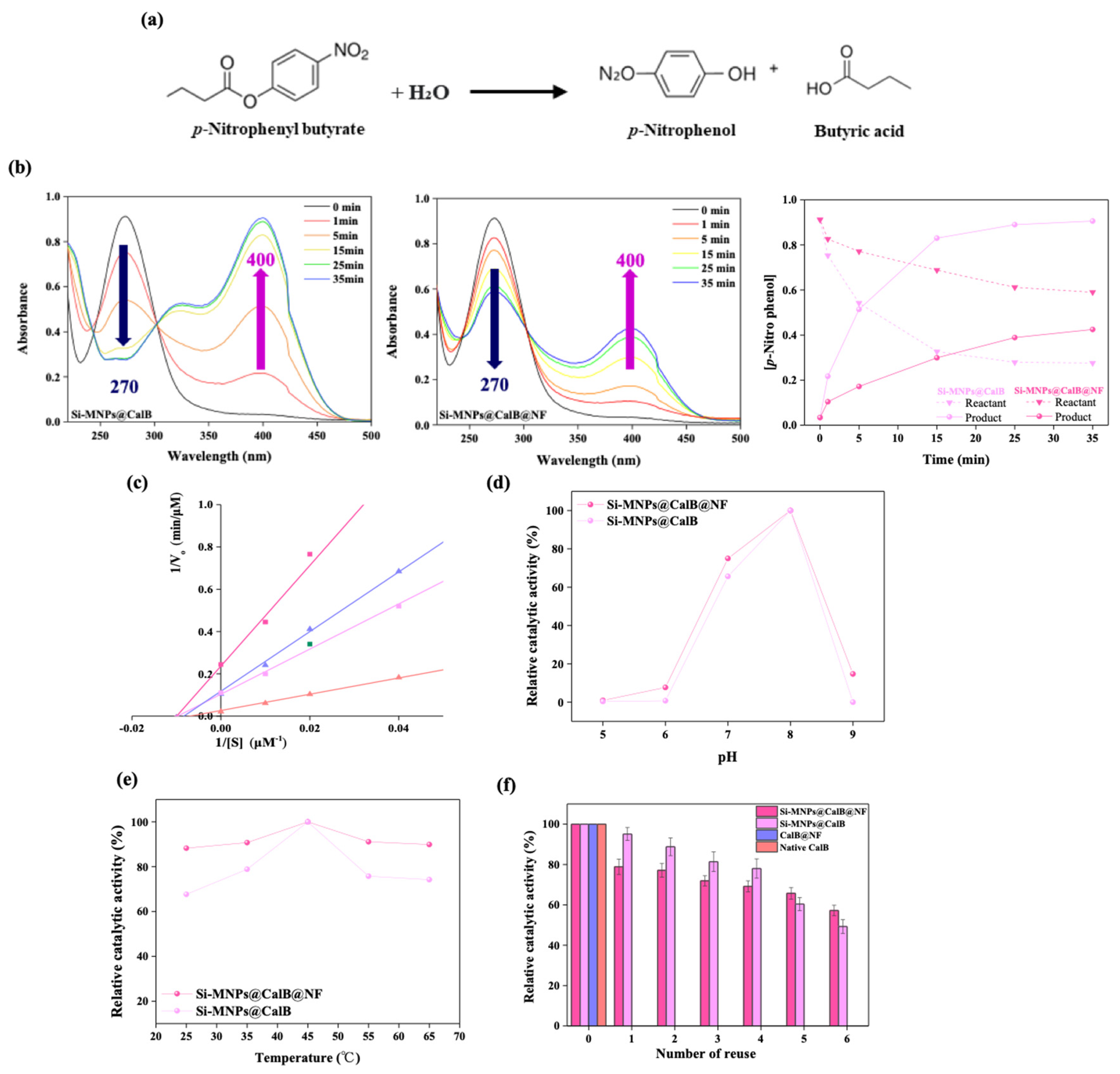

2.2. Enzymatic Hydrolysis

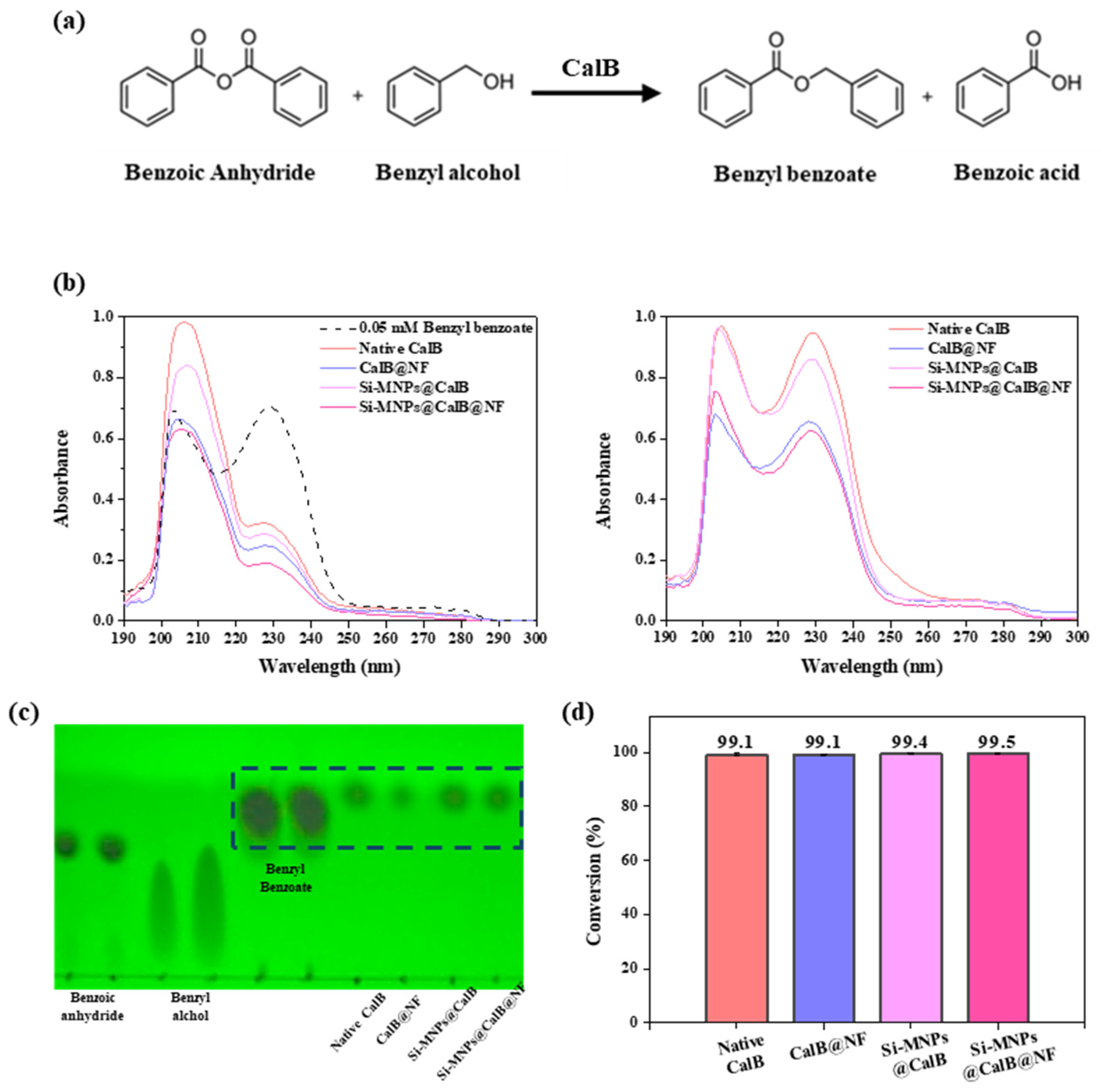

2.3. Enzymatic Acylation

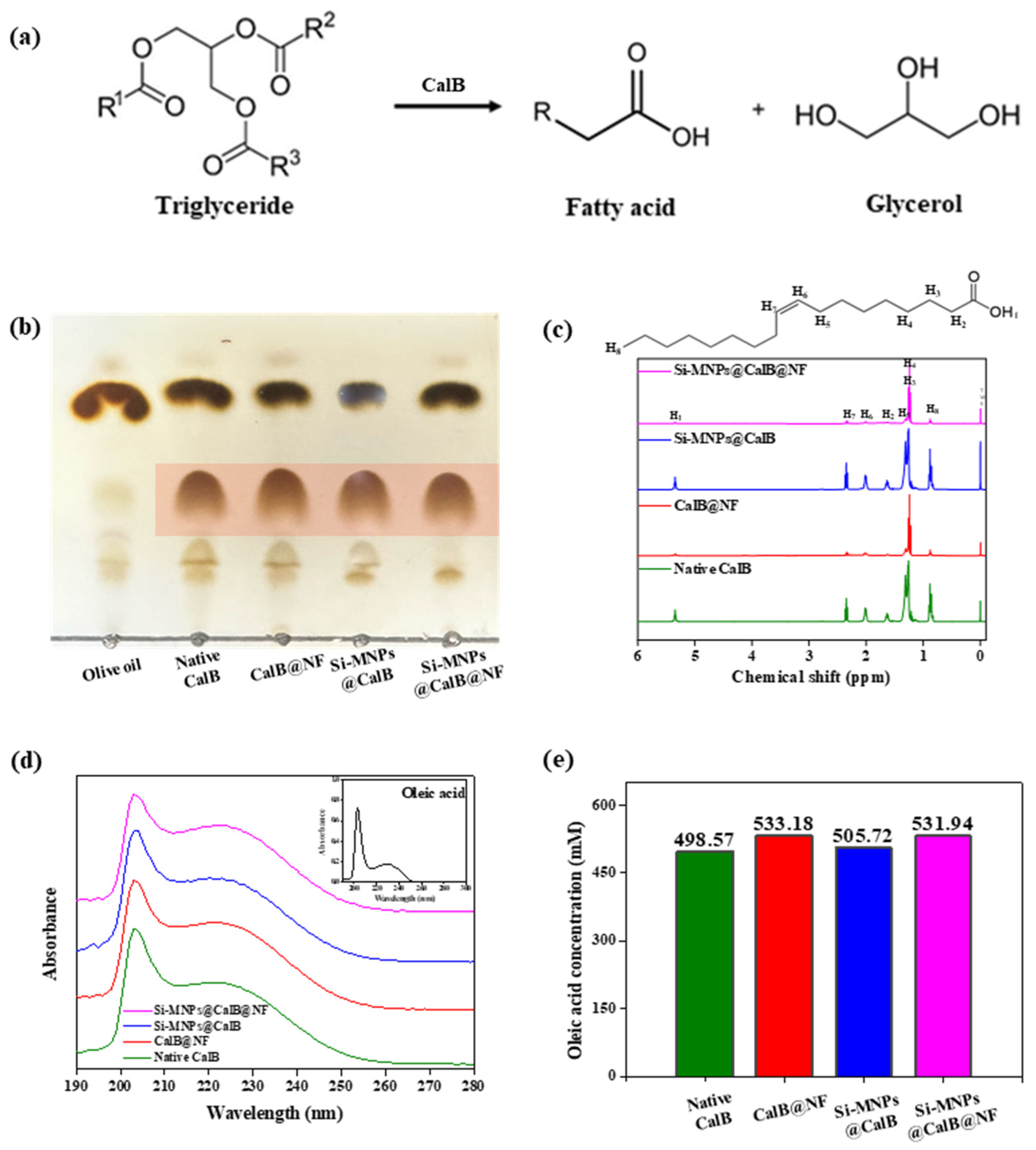

2.4. Enzymatic Lipolysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. The Preparation of MNPs and Si-MNPs

3.3. Immobilization of Native CalB & CalB@NF Lipase on Si-MNPs

3.4. Bradford Assay

3.5. Enzymatic Hydrolysis, Acylation, and Lipolysis

3.6. pH and Thermal Stability, and Reusability

3.7. Instrumental Analysis

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schoemaker, H. E.; Mink, D.; Wubbolts, M. G. Dispelling the myths-biocatalysis in industrial synthesis. Science, 2003, 299, 1694–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldatkin, O.; Kucherenko, I.; Pyeshkova, V.; Kukla, A.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; El’Skaya, A.; Dzyadevych, S.; Soldatkin, A. Novel conductometric biosensor based on three-enzyme system for selective determination of heavy metal ions. Bioelectrochemystry. 2012, 83, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H. R.; Kim, M. I.; Hong, S. E.; Choi, J.; Kim, Y. M.; Yoon, K. R.; Lee, S.; Ha, S. H. Effect of functional group on activity and stability of lipase immobilized on silica-coated magnetite nanoparticles with different functional group. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 29, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauch, B.; Fisher, S. J.; Cianci, M. Open and closed states of Candida antarctica lipase B: Protonation and the mechanism of interfacial activation1. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 2348–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C. H.; Patel, S.; Rajbhandari, P. Adipose tissue lipid metabolism: Lipolysis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2023, 83, 102114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, M.; Berger, J. E.; Steinberg, D. Hormone-sensitive lipase and monoglyceride lipase activities in adipose tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 1964, 239, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Soni, P.; Reetz, M. T. Laboratory evolution of enantiocomplementary Candida antarctica lipase B mutants with broad substrate scope. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1872–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basso, A.; Serban, S. Industrial applications of immobilized enzymes—A review. Mol. Catal. 2019, 479, 110607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. R.; Rathod, V. K. Enzyme catalyzed synthesis of cosmetic esters and its intensification: A review. Process Biochem. 2015, 50, 1793–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihu, A.; Alam, M. Z. Solvent tolerant lipases: A review. Process Biochem. 2015, 50, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navvabi, A.; Razzaghi, M.; Fernandes, P.; Karami, L.; Homaei, A. Novel lipases discovery specifically from marine organisms for industrial production and practical applications. Process Biochem. 2018, 70, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angajala, G.; Pavan, P.; Subashini, R. Lipases: An overview of its current challenges and prospectives in the revolution of biocatalysis. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R. N.; dos Anjos, C. S.; Orozco, E. V.; Porto, A. L. Versatility of Candida antarctica lipase in the amide bond formation applied in organic synthesis and biotechnological processes. Mol. Catal. 2019, 466, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N. W.; Zong, M. H.; Wu, H. Highly efficient transformation of waste oil to biodiesel by immobilized lipase from Penicillium expansum. Process Biochem. 2009, 44, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SÁ, A. G. A.; de Meneses, A. C.; de Araújo, P. H. H.; de Oliveira, D. A review on enzymatic synthesis of aromatic esters used as flavor ingredients for food, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals industries. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Cai, Z.; Xie, Y.; Ma, A.; Zhang, H.; Rao, P.; Wang, Q. Synthesis, physicochemical properties, and health aspects of structured lipids: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 759–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulinari, J.; Oliveira, J. V.; Hotza, D. Lipase immobilization on ceramic supports: An overview on techniques and materials. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 42, 107581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanem, A. Trends in lipase-catalyzed asymmetric access to enantiomerically pure/enriched compounds. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 1721–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Gao, J. Immobilization of Candida antarctica lipase B by adsorption in organic medium. New Biotechnol. 2010, 27, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlercreutz, P. Immobilisation and application of lipases in organic media. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6406–6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, O.; Christensen, M. W. Lipases from candida a ntarctica: Unique biocatalysts from a unique origin. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2002, 6, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R. R.; Neto, D. M. A.; Fechine, P. B.; Lopes, A. A.; Gonçalves, L. R.; Dos Santos, J. C.; de Souza, M. C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Ethyl butyrate synthesis catalyzed by lipases A and B from Candida antarctica immobilized onto magnetic nanoparticles. Improvement of biocatalysts’ performance under ultrasonic irradiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangiagalli, M.; Carvalho, H.; Natalello, A.; Ferrario, V.; Pennati, M. L.; Barbiroli, A.; Lotti, M.; Pleiss, J.; Brocca, S. Diverse effects of aqueous polar co-solvents on Candida antarctica lipase B. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hundschell, C.; Jakob, F.; Wagemans, A. Molecular weight dependent structure of the exopolysaccharide levan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvidson, S. A.; Rinehart, B. T.; Gadala-Maria, F. Concentration regimes of solutions of levan polysaccharide from Bacillus sp. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 65, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonh, J. H.; Bae, J. H. Levan-Protein Nanocomposite and Uses Thereof. KR Patent 2021, 10, 0012979. [Google Scholar]

- Rotticci, D.; Rotticci-Mulder, J. C.; Denman, S.; Norin, T.; Hult, K. Improved enantioselectivity of a lipase by rational protein engineering. ChemBioChem. 2001, 2, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, M.; Kostrov, X. Immobilization of enzymes on porous silicas–benefits and challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6277–6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, H.; Tian, R.; Ma, D.; Bao, X.; Su, D. S.; Zou, H. Ultrafast enzyme immobilization over large-pore nanoscale mesoporous silica particles. Chem. Commun. 2006, 1322–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, M.; Serrano, M.; Máximo, M.; Gómez, M.; Ortega-Requena, S.; Bastida, J. Synthesis of cetyl ricinoleate catalyzed by immobilized Lipozyme® CalB lipase in a solvent-free system. Catal. Today 2015, 255, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, S.; Patnode, K.; Li, H.; Baryeh, K.; Liu, G.; Hu, J.; Chen, B.; Pan, Y.; Yang, Z. Enhancing enzyme immobilization on carbon nanotubes via metal–organic frameworks for large-substrate biocatalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 12133–12141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartczak, D.; Kanaras, A. G. Preparation of peptide-functionalized gold nanoparticles using one pot EDC/sulfo-NHS coupling. Langmuir 2011, 27, 10119–10123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Ma, T.; Zhou, L.; Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Ying, H.; Chen, C.; Wang, P. Polyamine-induced tannic acid co-deposition on magnetic nanoparticles for enzyme immobilization and efficient biodiesel production catalysed by an immobilized enzyme under an alternating magnetic field. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 6015–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Y.; Ahn, C. Y.; Lee, J.; Chang, J. H. Amino acid side chain-like surface modification on magnetic nanoparticles for highly efficient separation of mixed proteins. Talanta 2012, 93, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazarika, K. P.; Borah, J. Study of biopolymer encapsulated Eu doped Fe3O4 nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia application. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A. K.; Gupta, M. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomater. 2005, 26, 3995–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Křížová, J.; Španová, A.; Rittich, B.; Horák, D. Magnetic hydrophilic methacrylate-based polymer microspheres for genomic DNA isolation. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1064, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Y.; Lee, J. H.; Chang, J. H.; Lee, J. H. Inorganic nanomaterial-based biocatalysts. BMB Rep. 2011, 44, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D. T.; Chen, C. L.; Chang, J. S. Immobilization of Burkholderia sp. lipase on a ferric silica nanocomposite for biodiesel production. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 158, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrasbi, M. R.; Mohammadi, J.; Peyda, M.; Mohammadi, M. Covalent immobilization of Candida antarctica lipase on core-shell magnetic nanoparticles for production of biodiesel from waste cooking oil. Renewable energy 2017, 101, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. H.; Sung, D. K.; Chang, J. H. Highly efficient antibody purification with controlled orientation of protein A on magnetic nanoparticles. MedChemComm 2017, 1, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. Y.; Lee, S. Y.; Lee, J. H.; Lee, H. S.; Chang, J. H. Biomimetic magnetic nanoparticles for rapid hydrolysis of ester compounds. Materials Letters 2013, 110, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylkie, K.; Nowak, P.; Rybczynski, P.; Ziegler-Borowska, M. Polymer-Coated Magnetite Nanoparticles for Protein Immobilization. Materials 2021, 14, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, N. J. The Bradford method for protein quantitation. The protein protocols handbook 2009, 17–24.

- Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Km (µM) |

Vmax (µM∙min-1) |

Kcat (min-1) |

Kcat/ Km (µM-1∙min-1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native CalB | 187 | 46 | 1391 | 7.4 |

| CalB@NF | 94 | 9 | 1909 | 20.3 |

| Si-MNPs@CalB | 139 | 9.5 | 1151 | 8.3 |

| Si-MNPs@CalB@NF | 96 | 4 | 975 | 10.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).