1. Introduction

Exoskeletons are emerging as effective tools for facilitating motor rehabilitation in patients with impaired upper limb function [

1,

2]. In this regard, robotic exoskeletons designed specifically for the hand have the potential to enhance hand rehabilitation and assist individuals in activities of daily live (ADLs). The human hand poses a significant challenge for the design and control of such devices, due to its high bio-mechanical complexity [

3,

4]. The hand can perform precise manipulation tasks, thanks to the coordinated action of 27 bones, 27 joints, and 34 intrinsic and extrinsic muscles.

Hand exoskeletons commonly mimic the skeletal structure of the fingers, the phalanges, by means of joint-based rigid-bodies. Recently, the use of soft materials has been proposed, as they allow for more natural movements and better adaptation to the hand dexterity. The main efforts on soft exoskeletons have focused on deformable materials and real-time control of an increased number of degrees of freedom (DoF) [

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, robust closed-loop control strategies are difficult to apply since most of these methods require the calculation of the exoskeleton dynamics to compute the control signal in real-time. Among the control models for exoskeletons, position-based and force-based controls are widely used. Additionally, control strategies based on the evaluation of electromyographic (EMG) signals, combined with machine learning algorithms are increasingly proposed [

9,

10,

11]. More recently, electroencephalographic (EEG) signals and cameras have also been proposed for motor control [

12]. For instance, in [

13], a rigid-soft combined mechanism is developed to support hand rehabilitation based on a EEG brain-controlled switch implemented in Matlab™, while an external VICON™motion capturing system is required to determine the fingers position in 3D space. The authors in [

14] present a force myography (FMG) to allow grasping assistance. The controller is based on a switching algorithm to properly modulate a soft-extra-muscle (SEM) glove, while machine-learning models running offline were trained to estimate grasp forces. Approaches in [

11,

15,

16] depend on machine-learning offline processing to support EEG/EMG control, force-based control or simple switch-driven modulation.

In terms of actuation, pneumatics actuators (PAs) [

17], electroactive polymers (EAP) [

18] and shape memory alloys (SMAs) [

19] are the most predominant technologies used in soft robotic exoskeleton and gloves. As mentioned in [

11,

18], in most of the cases, finite elements methods (FEMs) are used to model flexible and deformable properties, requiring compute-intensive requirements. In previous efforts reported in [

20,

21], we presented the development of a rigid-body robotic exoskeleton to assist in the recovery of hand motor function for post-stroke subjects. Our study proposed a closed-loop model predictive control (MPC) method with the aim of compensating the effects of muscle fatigue during the rehabilitation therapies. To this purpose, EMG-based muscular effort must be detected within the control loop in order to modulate the exoskeleton’s velocity accordingly. Since the MPC method requires the computation of the exoskeleton dynamics model, applying this control algorithm implies significant challenges to soft exoskeleton mechanisms. In fact, few works in the literature [

22] have applied robust control methods to modulate a soft robotic exoskeleton.

In this paper, we tackle the challenge of calculating the exoskeleton’s equations of motion (EoM) to support robust dynamics control for a hybrid soft-exoskeleton design based on compliant joints, as depicted in the inset of

Figure 1a. We have adopted the parallel structure introduced by [

23] to solve large-scale EoM dynamics as a foundation of the proposed soft-based highly-redundant joint exoskeleton robot. The proposed dynamics control method via inverse-dynamics EoM is based on the well-known Recursive Newton-Euler Algorithm (RNEA), presented by [

24].

Figure 1b details the multi-body diagram to represent each digit of the exoskeleton. Spatial operators for velocity (

), acceleration (

) and force (

) led to six-dimensional physical quantities that combined the angular and linear motions of the system. The RNEA method computes two recurrences to propagate the aforementioned spatial operators from the exoskeleton’s base to each fingertip of the serial-chain. In this regard, solving the inverse-dynamics via the RNEA method allows for the calculation of applied forces to properly control the exoskeleton’s dynamics motion. Other works in [

25,

26,

27] have used similar approaches to dynamics modeling and robust control for exoskeletons based on the RNEA method. Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to apply a parallel solution for the RNA as an alternative to control soft exoskeletons in real-time.

As mentioned, classical techniques used in soft-robotics that are mostly based on finite element theory are not suitable in our application, since we require online computation of the dynamics model within a closed-loop control algorithm capable to scale up. To this purpose, hardware-based parallel computation of the EoM will be processed within an embedded system with multi-core CPU/GPU capabilities, to support the real-time calculation of the exoskeleton’s large-scale dynamics model, considering up to

degrees of freedom to emulate continuous flexible soft bending, and achieving a

computational complexity. To support the evaluation of this approach, we propose a hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) architecture as represented in

Figure 1a. This control scheme consists of two main components: (i) a software-side modeling the soft-exoskeleton under analysis, which is supported by Matlab®, directly running on a desktop computer; and (ii) a hardware-side supported by an embedded platform with highly parallel computing capabilities, in charge of calculating the inverse dynamics control to drive the exoskeleton.

By adopting this HIL-based architecture, it is possible to represent very complex models, such as the referenced soft-exoskeleton, without the necessity of actually building it and integrating all the required sensors and acquisition stages. Nonetheless, this approach also allows us to validate the proposed control scheme in real hardware platforms, such as the selected embedded systems. The software-side reproduces all the complex dynamics of the exoskeleton and generates the corresponding outputs (position, velocity and acceleration) that are sent to the hardware-side. With these signals coming from the exoskeleton’s digital twin, the hardware-side applies the corresponding control scheme and in turn generates the control signals to the virtual actuators (e.g., motors), also implemented in the software-side. As it has been explained before, the biggest advantage is the ability to test, validate and evaluate the performance and scalability (with respect to the number of available cores or processing units) of the control scheme as it would execute in a real deployment. Our main contributions can be summarized as follows:

an alternative approach to calculate dynamics equations of motion for soft exoskeletons in real-time, adopting a parallel computation for highly-articulated systems with a computational complexity, and

the integration and deployment of this approach on embedded systems, facilitating modular dynamics-based control of soft exoskeletons by following a hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) approach.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2.1 briefly introduces several design approaches for the proposed soft exoskeleton, based on previous works reported in [

20,

21,

28]. Also, the formulation for the equations of motion (EoM) based on the Newton-Euler formalism using spatial operators;

Section 2.2 details the proposed parallel computing approach for the EoM, by applying the well-known RNEA method (Recursive Newton-Euler Algorithm) [

24,

25], allowing dynamics control of the soft exoskeleton with a computational performance

;

Section 3 presents the computing results obtained from several multi-core CPU/GPU embedded systems running under a HIL approach;

Section 4 deals with discussions and remarks about the proposed approach for controlling soft exoskeletons; and

Section 5 concludes this work with some insights, limitations and future work.

2. Methods

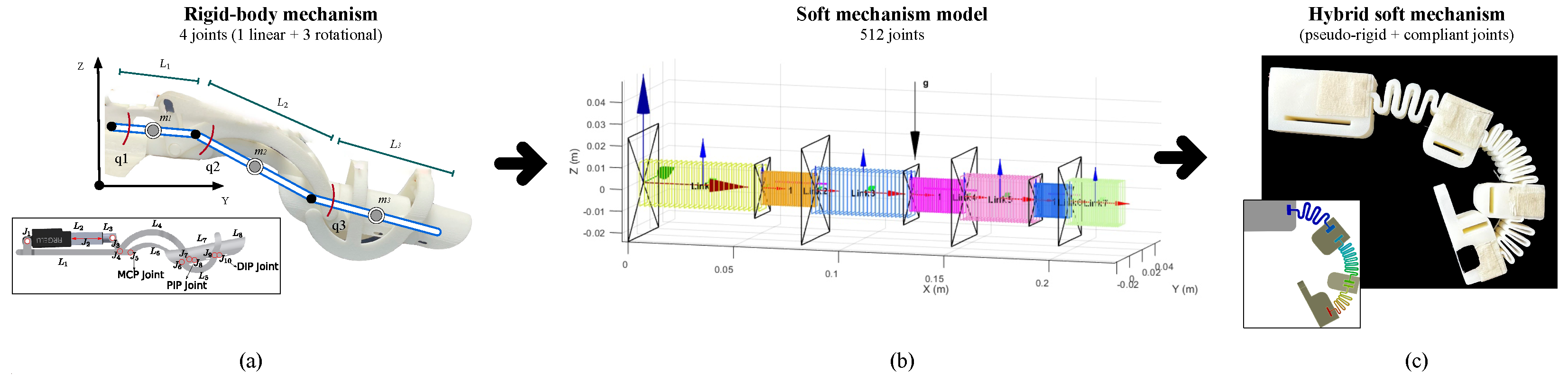

Our first design approach for the exoskeleton was presented in previous works reported in [

20,

21]. The system was conceived as a branched physical model, in which each finger is composed by a chain of rigid bodies serially connected through joint links.

Figure 2a details the former mechanical design. As mentioned, we are working on a novel design approach supported by a hybrid soft mechanism based on compliant joints, as shown in

Figure 2c. In order to apply our proposed method to model such mechanism, we require to determine a sufficient amount of joints to emulate soft motion properties.

Figure 2b details this approximation to a soft finger of the exoskeleton via 512 degrees of freedom.

2.1. Equations of Motion

Soft motion is described based on Newton-Euler dynamics extended to large-scale articulated systems. Equations of Motion (EoM) are presented using spatial operators in , allowing joint kinematics and dynamics calculations to mimic soft deformation. Next subsection reviews the fundamental concepts of the classic mechanics that are related to body dynamics modeling, establishing an appropriate mathematical representation of the physical quantities involved in the dynamics behavior of the robotic exoskeleton.

Assuming from

Figure 1b that the joint frame

i and the center of mass (

) are two points located on the body

i, the term

is the position vector connecting frames

i and

, while

connects consequently joint frames that are serially coupled. Also, the term

is the rotation matrix that relates frames

with

. The translational (

) and angular velocities (

) for each body, as well as and forces (

) and moments (

) acting on the joint frame can be integrated into spatial operators that led to six-dimensional physical quantities, by combining the angular and linear variables of body motions. Using spatial notation, velocities

V, accelerations

, and forces

F of a body

i are expressed with respect to center of mas

using six-dimensional vectors in

, as follows:

Using the position vector

, shown in

Figure 1b, the physical quantities can be also expressed with respect to the joint frame

, as:

Being

the spatial operator connecting both frames, defined by the skew-symmetric matrix

, as:

Where

is the identity operator. From Equation (

2), the spatial forces acting onto the joint frame (

) can be derived as

, where

is the spatial inertia operator of the body

i with respect to its center of mass (

), and

corresponds to the spatial velocity defined in Equation (

2). Differentiating as a function of time yields:

Using the spatial operation for translation defined in Equation (

3), spatial forces with respect to the joint frame can be calculated as:

From Equation (

2), spatial accelerations can be defined as

. Replacing into Equation (

5) yields:

Since each finger of the exoskeleton is composed by a serial chain of connected joints, spatial forces can be propagated from the fingertip (

) to the base (

), by using specific operators for rotation and translation. Therefore, a propagated term can be included into Equation (

6), such as:

Equation (

7) describes a backward propagation of spatial forces, where six-dimensional operators in

for rotation

R and translation

P are defined as follows:

Where

is the classical basic rotation matrix and

is the skew-symmetric matrix of the position vector

. As depicted in

Figure 1b, spatial forces are calculated by following a backward propagation, initiating at the fingertip frame (

) and finalizing at the base frame of the exoskeleton’s finger (

). To this purpose, the spatial terms

in Equation (

4) allow the propagation of the spatial forces (

F) through the exoskeleton, considering the external load (

) imposed by the hand or any manipulated object. Therefore,

.

Applying a similar approach, both

and

are also used to propagate spatial velocities (

) and accelerations (

) by following a forward propagation from

, as:

The mathematical expressions for the Equations of Motion (EoM): spatial velocities

, accelerations

and forces

are presented in Equation (

7) and (

9) respectively, and consolidated in Algorithm 1. The inputs to the algorithm are the joint trajectories (therapy motion) determined by the terms

, whereas the output is the required torque

for each joint

i. As mentioned, the method is divided into two recurrences: (i) a forward calculation and propagation of the spatial velocities and accelerations and (ii) a backward recurrence to calculate spatial forces and the torques acting on each joint of the fingers.

Table 1 presents the list of parameters used for the EoM. Nonetheless, this

approach is insufficient to model large-scale soft systems composed by thousands of joints that enable body deformation, since the computing time increases linearly as a function of the number of degrees of freedom

n.

|

Algorithm 1 RNE serial computation |

1. Input joint trajectory (therapy motion) for each joint i: 2. initialize parameters: fixed-base (no 6D motion of the wrist) and gravity acceleration acting on the carpal (along x-axis). 3. , 4. 5. Forward recurrence: spatial velocities and accelerations propagation from carpals to distal phalanges:

fordo

(1) (2)

end for ——————————————————- 6. (payload at the distal phalange is included) do payload force

do 7. Backward recurrence: spatial forces calculated from distal phalanges to the carpals.

fordo (3)

(4)

end for Return

|

2.2. Parallel Computing

Embedded systems with multi-core CPU/GPU architectures has enabled an increase in computational power that allows complex algorithms to run on the edge in real-time. This novel edge computing paradigm can be applied to our system, allowing a modular and compact design for the exoskeleton’s control electronics. In this regard, we propose a reformulation of Algorithm 1 to compute the EoM in a parallel fashion.

As previously mentioned, the classical formulation of the EoM based on the spatial Newton Euler formalism requires an

computational complexity. It was [

30] that improved the computational efficiency by computing the EoM recursively (forward dynamics) by referring the forces to generalized coordinates in the joint space. This was called the Recursive Newton-Euler Algorithm (RNEA), which was later modified by [

31], by using a new approach called CRBA (Composed Rigid Body Algorithm). In [

32] presented the first parallel approach to solve the CRBA for both inverse/foward dynamics problems with an

complexity, but strictly dependent on the overlapping costs associated to calculation of the inertial operators. In [

23], the overlapping costs of Fijany’s parallel approach was solved, adapting the RNEA algorithm by following the well-known Kogge and Stone recursive doubling technique [

33].

Here, we adopted the solution proposed by [

23], in order to solve the inverse dynamics model to compute the exoskeleton’s EoM into two computational recurrences: i) a forward propagation of spatial velocities (

V) and accelerations (

), ii) a backward propagation of spatial forces (

F). Applying the Kogge and Stone method for each recurrence yields the structure presented in

Figure 3, which reduces the equation set

of Equation (

7) and (

9) for a total of

computational steps (

e) by powers of 2. The key element for this parallel approach is to identify the

dependent term of each equation, which can be propagated to each computer node/process of the embedded system.

Note in Equation (

9), the spatial velocity is composed by two terms:

, in which

can be propagated whereas

can be computed in parallel for each computer node at the same computational step (

e). The left plot of

Figure 3 illustrates this process. While the serial

Algorithm 1 would require

computational steps to solve

equations for the spatial velocities

, the parallel approach solves the same

equations in only

computational steps, since

. Likewise, spatial accelerations follow the same structure. In the case of the spatial forces, the propagation is backwards, as detailed by the right plot of

Figure 3.

Therefore, scaling up to higher degrees of freedom (n), e.g. will required only computational steps, assuming the embedded systems incorporates 512 processing nodes/cores (p), i.e. . If , multi-threading can be applied for the parallel computation of the EoM. Algorithm 2 presents the parallel computation of the dynamics equations of motion for the soft exoskeleton.

In order to evaluate the performance of Algorithm 2, the Amdahl’s law is used [

34]. Equation (

10) describes the speedup metric, which is defined by the fraction of the algorithm that is inherently serial (

) and the portion that is parallelized (

):

|

Algorithm 2 RNE parallel computation |

1. Input joint trajectory (therapy motion) for each joint i:

: do parallel 2. , 3. Spatial velocity: 4. , , 5. Spatial acceleration: 6. Forward recurrence: spatial velocities and accelerations propagation:

fordo if if send to node else send to node endif endif if if receive from node else receive from node endif endif if if else , , , endif endif

end for 7. , 8. Spatial force: 8. Backward recurrence: spatial forces propagation:

fordo if if send to node else send to node endif endif if if receive from node else receive from node endif endif if if else endif endif

end for Return

|

if

the load distribution of processor (

p) can be assigned to each individual joint of the exoskeleton (

n: degrees of freedom). Otherwise, if

communication packing and multi-threading processing are required.

3. Results

Algorithm 2 was coded in ANSI C programming language and implemented using the standard message-passing-interface (MPI) supported by the

mpich library [

35]. In this section, we analyze the performance of the

RNE algorithm running in several computing architectures:

Intel®Core™i7 Processor with 6 CPU cores at 2.6GHz and 512 GPU NVIDIA Quadro P1000 cores | 32GB RAM | Ubuntu 22.04.3 LTS.

Hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) with the Embedded Nvidia Jetson™Nano with 1024 cores at 625MHz | 8GB RAM | Ubuntu 22.04.3 LTS.

Figure 4 details the computing time response of the proposed parallel approach running on the Intel®Core™i7 with NVIDIA Quadro GPU. The plot

Figure 4a compares both serial

and parallel

algorithms. As mentioned, both solutions for the inverse dynamics EoM were coded in ANSI C, using the high-performance Meschach framework; a comprehensive matrix-vector linear algebra for the operation of 6D spatial terms. The

RNE approach significantly outperformed the serial algorithm

DoF, obtaining a real-time response of

in the calculation of the inverse dynamics control for the soft exoskeleton with

joints. In this test, we used an interpolated 3D spline trajectory with

knot-points. Contrary, the serial

RNE required

for the calculations. Considering the size of the input trajectory for the exoskeleton (

knot-points), the net computational time is proportional to

. In this sense, the inset within plot

Figure 4b shows the resulting computing time of the parallel RNE approach with variations in the input trajectory knot-points.

The overall performance of the proposed solution is presented in

Figure 5. The speedup exponentially increases after

, while achieving a

degree of parallelism after approximately

, which demonstrates the required scalability for controlling highly-articulated and large-scale soft exoskeletons in real-time.

Another important element of the proposed

RNE algorithm is related to the propagation structure of the EoM, in which the inherent sequential-time component of the algorithm can be drastically reduced if an embedded system-on-chip (SoC) is used. With an SoC-based embedded system, CPU/GPU cores are integrated with the memory in the same silicon, allowing higher data bandwidth to propagate data. This issue can be observed in

Figure 6. Using the MPICH-library jumpshot feature, real execution with data propagation can be analyzed, by determining both serial and parallel computing time involved the calculation of the dynamics EoM. In this test, we used

to clearly visualize the computational steps (

e) followed by the

propagation of spatial velocities (

), accelerations (

) and forces (

), as previously defined in

Figure 3.

As previously mentioned, classical techniques used in soft-robotics that rely on finite element theory are not suitable in our application, since we require real-time computation running online while the exoskeleton. In this regard, we compared our

RNE model against the Ansys®simulator, performing finite element analysis based on the Newton-Raphson iteration method applied to the proposed semi-soft structure driven by the compliant joint mechanism shown in

Figure 2c. Also, as detailed in the inset of

Figure 7a, the exoskeleton model is composed by one finger with 3 phalanges (the distal, middle, and proximal) performing a closing/opening trajectory with 90 knot-points with a step time of

. Under this topology Ansys used

nodes for the semi-soft structure of the exoskeleton, requiring a simulation time of

and execution time of

. Ansys determines the number of nodes and degrees of freedom (DoF) automatically. For the same trajectory with

knot-points and a step time of

, our

RNE model required

for 512 DoF, as shown in

Figure 4b. Increasing up to

DoF yielded a computing time of

, using a MPI configuration for

(more degrees of freedom than processing cores). Even with this computing-intense configuration, our model dramatically outperformed Ansys results in terms of simulation time.

Also,

Figure 7b presents computing time results for the soft model implemented in SoRoSim©Matlab™introduced by [

29]. SoRoSim uses Geometric Variable Strain (GVS) approach for the dynamic simulation of soft systems. We tested several configurations from

up to

joints for the links assembly, as detailed in the insets of

Figure 7b. For

, the method performed with a computational time of

, whereas our method required

. Besides, the computational performance of SoRoSim exhibits a linear complexity

, i.e., higher computing times will be obtained for large-scale articulated soft systems, compromising the scalability of the solution. In contrast, our model will scale with a complexity of

, as demonstrated in

Figure 4.

Next, we present the performance of the

RNE algorithm running in a SoC-based embedded system with 1024 cores powered by the Nvidia Jetson Orin™Nano, with the ultimate goal of reducing the inherent serial time computation of Algorithm 2, and the advantage of compacting the proposed inverse-dynamics controller to support closed-loop robust control of the soft exoskeleton in real-time by following the proposed Hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) configuration.

Figure 8 presents the experimental results obtained with this embedded system.

Both mpich and meschach libraries were compiled within the Nvidia Jetson Orin™Nano, allowing the computation of Algorithm 2 with similar computing times of those obtained from the Intel®Core™i7 Processor with 512 GPU NVIDIA Quadro cores, as presented in

Figure 4b. For

, the parallel RNE algorithm required

for

trajectory knot-points. As observed in

Figure 8, the variance in computational time remains under

, resulting feasible for in-loop real-time response.

Finally,

Table 2 presents the computing time results for the aforementioned tests:

refers to Algorithm 1 running on the Intel®Core™i7 Processor with 512 GPU NVIDIA Quadro cores, SoroSim refers to the tests presented in

Figure 7b running under Matlab™,

also refers to Algorithm 2 running on the Intel®Core™i7 Processor, whereas HIL-

refers to Algorithm 2 running on the embedded Nvidia Jetson Orin™Nano with 1024 cores. Furthermore, for the tests conducted in Ansys®, was not possible to configure the soft exoskeleton for different DoF values, since Ansys®determined

DoF for the assembly shown in

Figure 7a, requiring a simulation time of

(

minutes).

4. Discussion

Algorithm 2 was implemented and tested on the embedded Nvidia Jetson Orin™Nano with 1024 cores, allowing the real-time calculation of the proposed inverse-dynamics controller based on the RNE method. As shown in

Figure 8, the obtained computational complexity is of the form

, being

the overall knot-points used to interpolate the reference trajectory for the exoskeleton.

In this regard, it is worth to highlight that those changes in the trajectory knot-points are associated with the precision and intensity of the therapy. In previous work reported in [

28], we used a VICON™ motion capture system to extract the kinematics of motion associated to 6 hand gestures for rehabilitation. We implemented interpolation methods based on 3D splines to determine both cartesian and joint trajectories to drive the exoskeleton assistance. Here, the joint trajectory for positions (

), velocities (

) and accelerations (

) are used as inputs to Algorithm 2, in order to estimate the computing time cost of the parallel inverse dynamics controller by analyzing the impact of increasing motion precision according to the computational complexity of the form

.

Although similar computing times were obtained with the embedded platform in comparison to the desktop solution (c.f

Table 2), the proposed HIL-driven embedded approach allow us to deploy a modular control system, facilitating the use of the soft exoskeleton in real rehabilitation scenarios. Also, we demonstrate that even with higher values of

, the inherent logarithmic response

is maintained, supporting highly-articulated soft exoskeletons.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J. Colorado, D. Mendez; methodology, J. Colorado, D. Mendez, Andres Gomez-Bautista, John Bermeo, Fredy Cuellar; software, J. Colorado, Andres Gomez-Bautista, John Bermeo, Fredy Cuellar; validation, J. Colorado, D. Mendez, Andres Gomez-Bautista, John Bermeo, Fredy Cuellar; formal analysis, J. Colorado, D. Mendez, Andres Gomez-Bautista, John Bermeo, Fredy Cuellar, C. Alvarado-Rojas; investigation, J. Colorado, D. Mendez, C. Alvarado-Rojas; data curation, J. Colorado, Andres Gomez-Bautista; writing—original draft preparation, J. Colorado; writing—review and editing, D. Mendez, Andres Gomez-Bautista, John Bermeo, Fredy Cuellar, C. Alvarado-Rojas; supervision, J. Colorado, D. Mendez; project administration, J. Colorado; funding acquisition, J. Colorado. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.