1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) encounters persistent mathematical difficulties—optimization, generalization, interpretability, and phase transitions—that constrain deployment in high-stakes domains such as medicine, autonomous systems, and finance. Closely related questions arise in physics and engineering: nuclear fusion, turbulence, neural information processing, the design of materials and medicines, genetic problems, and rare but high-impact events (earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis). These issues share a common core: prediction under uncertainty, often in regimes dominated by low-probability, high-consequence outcomes [

27].

This work advances the perspective that the universal properties of the Riemann zeta function provide a coherent mathematical framework for these problems [

6,

8]. We concentrate on two themes—AI optimization and turbulence—while indicating how the same structure extends to broader applications. Reports over 2023–2025 suggest a sharp rise in electricity demand for AI (from roughly 0.1% to 2% of global use), together with substantial water consumption for cooling, underscoring the need for algorithms that are both accurate and energy efficient [

30]. Motivated by classical ideas on computational economy (e.g., Gauss’s summation argument), we explore zeta-based constructions that promise meaningful cost reductions. Our approach builds on Voronin’s universality theorem and constructive developments by Durmagambetov (e.g., explicit bounds on

in zero-free regions [

14,

15]), and is accompanied by practical algorithms, simulation proposals, and an expanded literature review [

18,

25].

2. Problem Statement

The computational burden of AI—together with the algorithmic demands of turbulence modeling for fusion—raises three interlocking difficulties: (i) navigation of nonconvex, high-dimensional loss landscapes; (ii) representation and control of multiscale dynamics; and (iii) closure limitations in kinetic descriptions such as the Boltzmann hierarchy [

23,

24].

We propose exploiting zeta-function universality to address these points:

We provide a concrete optimization algorithm, simulation strategies, and numerical comparisons (via

S matched to standard physical distributions, with quantitative fits), and we place the results within recent literature on AI and turbulence [

21].

3. Mathematical Methods

3.1. Disciplines and Core Challenges

The following mathematical disciplines are central to the problems addressed:

Probability Theory and Statistics: Bayesian inference, maximum likelihood; challenges: uncertainty quantification, model misspecification [

27].

Linear Algebra: High-dimensional data analysis, neural operations; challenges: curse of dimensionality.

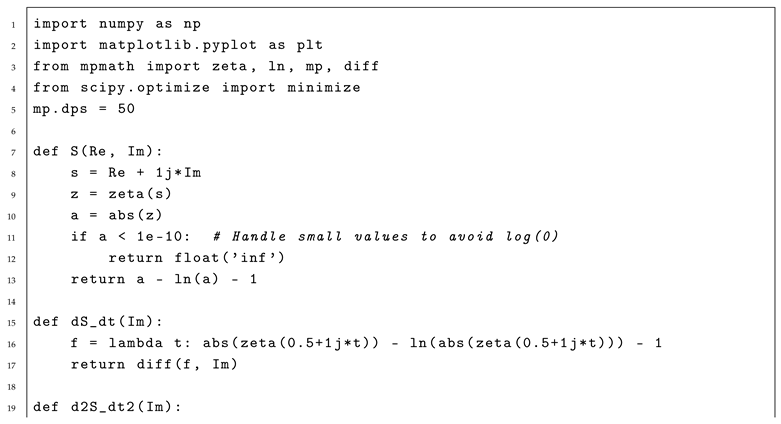

Optimization Theory: Gradient-based loss minimization; challenges: nonconvexity, local minima [

26].

Differential Equations: Neural ODEs, dynamical systems; challenges: stiffness, multiscale dynamics.

Information Theory: Entropy and compression trade-offs; challenges: noise and distribution shift.

Computability Theory: Algorithmic limits; challenges: undecidability.

Stochastic Methods: Monte Carlo, SGD; challenges: variance, inefficiency.

Deep Learning: Complex structures; challenges: interpretability, overfitting [

19].

3.2. Constructive Universality and Zeta-Guided Modeling

Theorem 1 (Voronin’s universality)

. Let D be a compact subset of the strip with connected complement. For any nonvanishing analytic f on D and any , there exists such that

Building on universality and constructive methods [

6], we treat the zeta function as a generator of measures and as a coordinate for dynamics, shifting computation to the motion of a single parameter

s along the critical strip [

25].

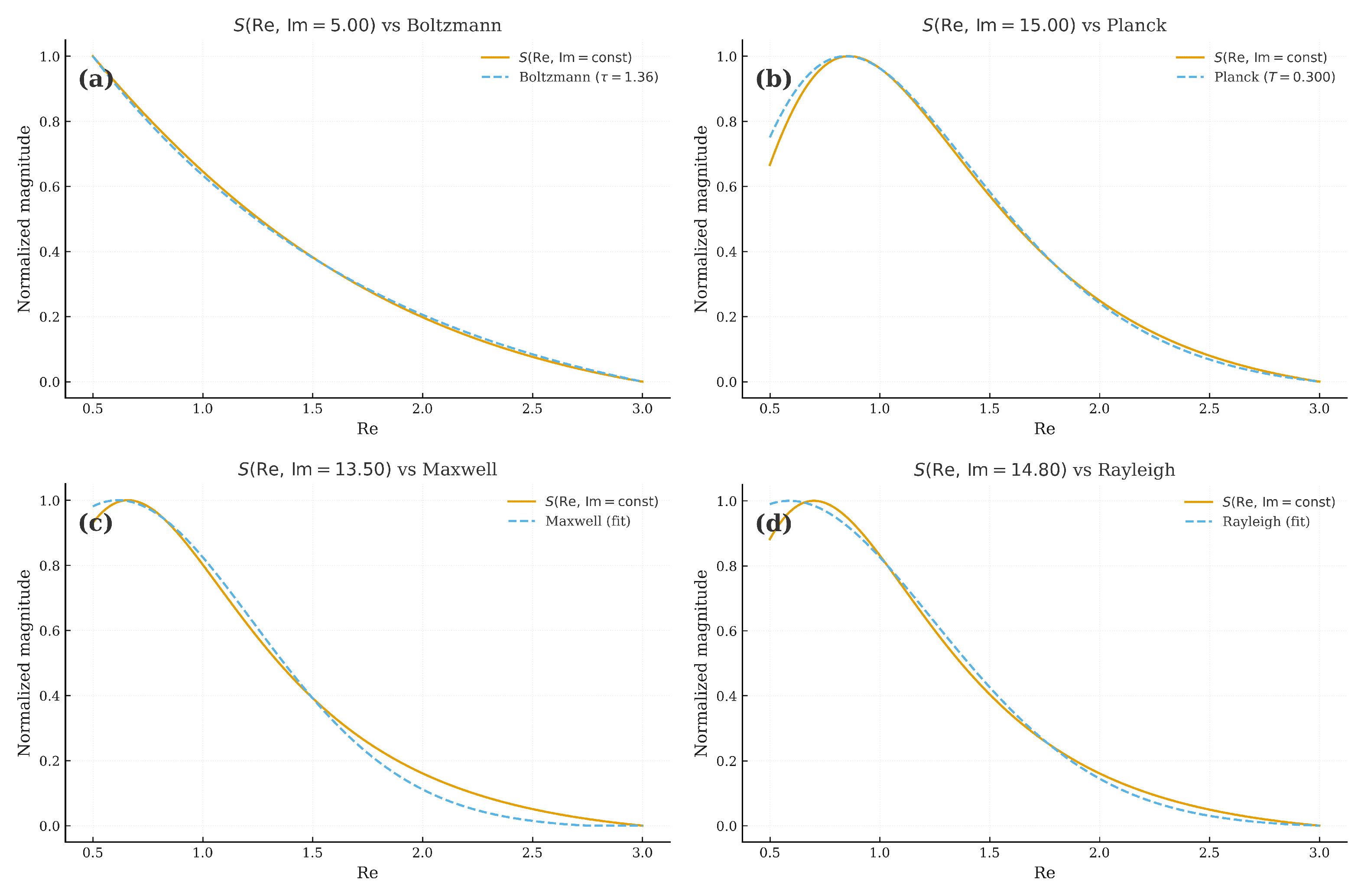

3.3. Zeta-Derived Potential and Family of Measures

We define

where

. For fixed

, the map

generates curves that can be fitted to canonical distributions (Boltzmann/Maxwell, Planck, Kolmogorov), enabling a

self-consistent selection of measures for modeling [

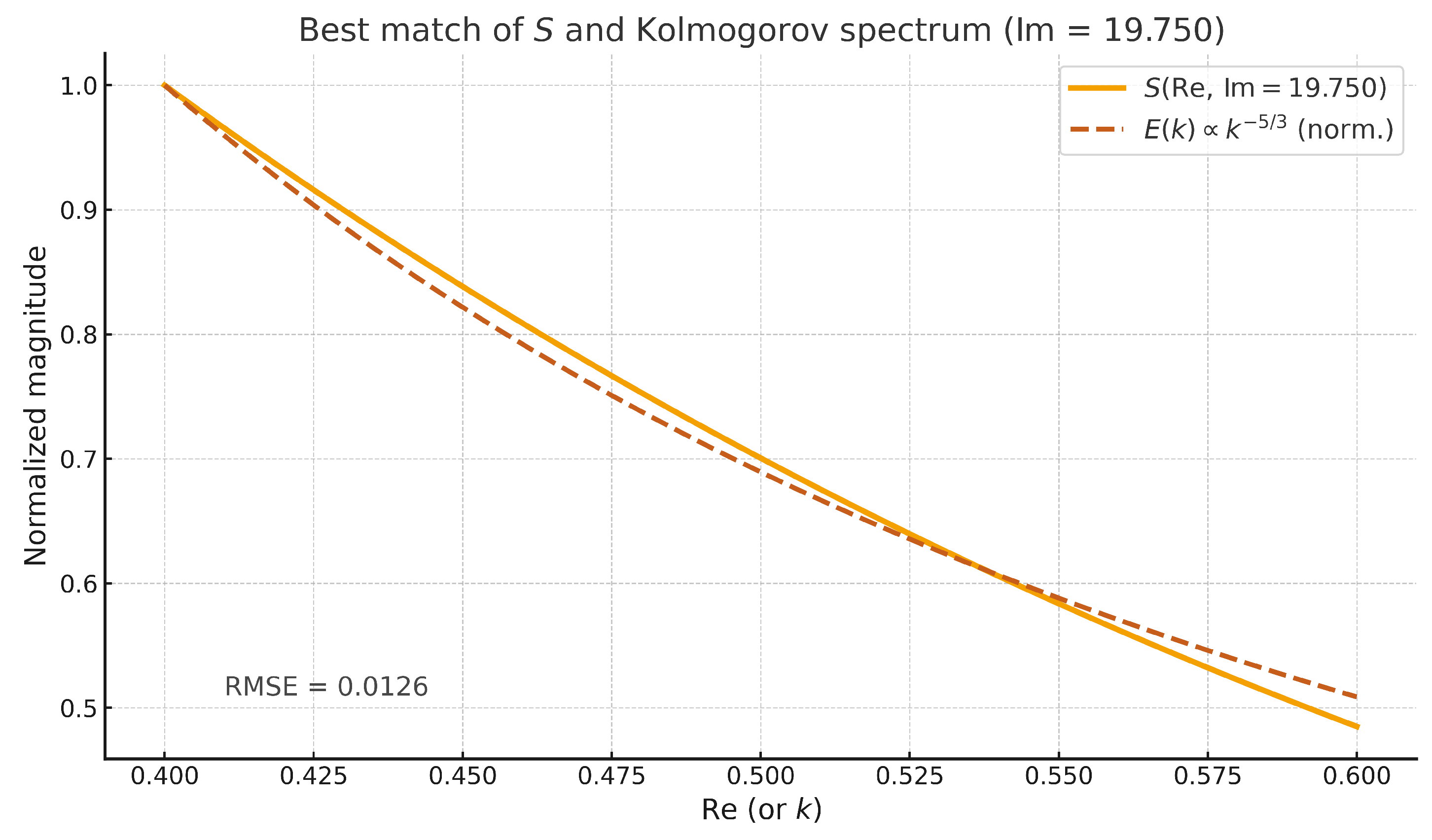

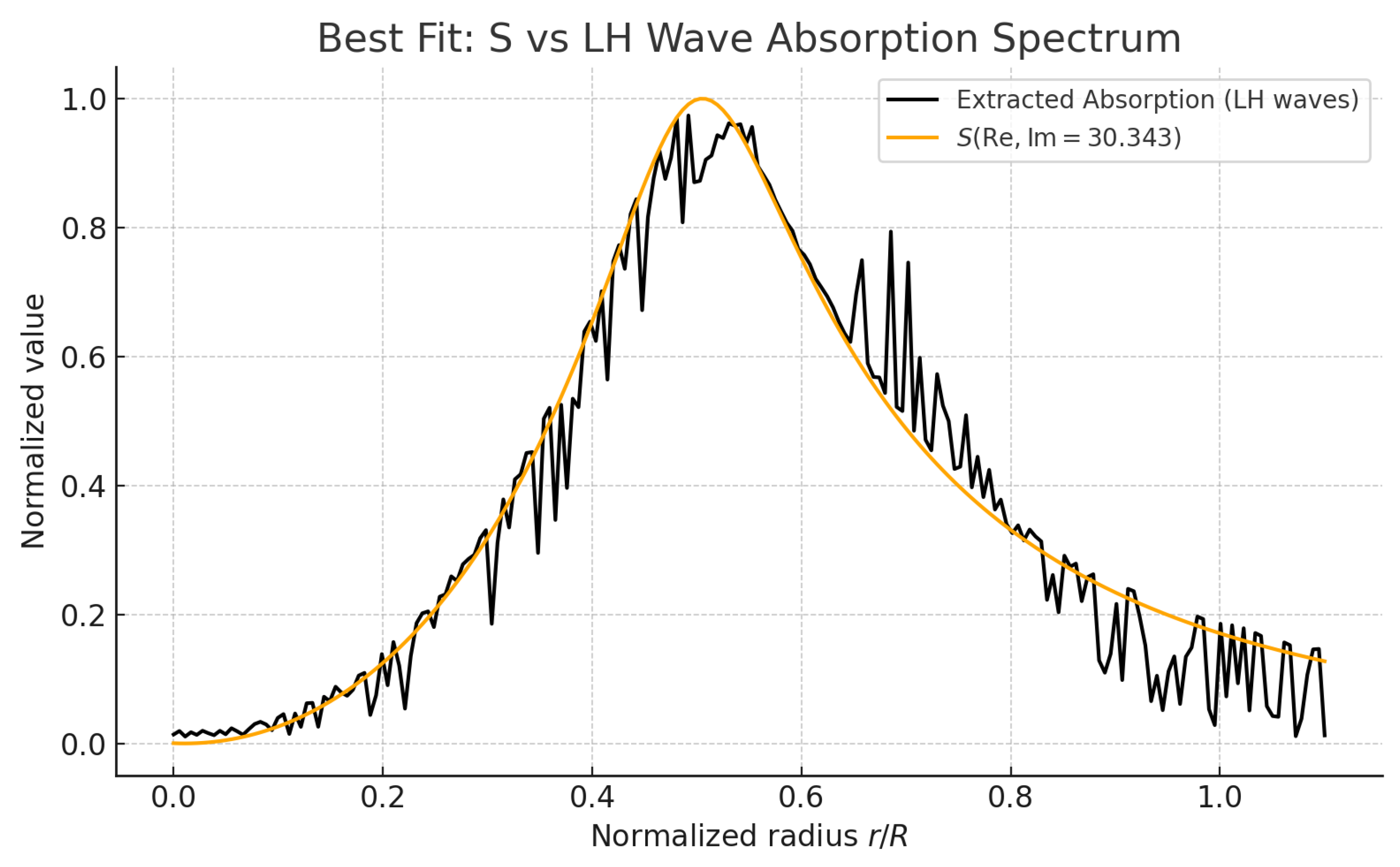

28]. To quantify the match, we use least-squares fitting or KL-divergence minimization over scaling parameters. For instance, numerical fitting to the Kolmogorov spectrum yields optimal scaling

with sum of squared errors (SSE)

(see

Appendix B for details). Note that the mapping aligns

with

for spectral comparisons, ensuring dimensional consistency.

Remark 1. Interpreting as a partition-function surrogate connects (1) with generalized entropy constructions, where contributes an entropic part and acts as an energetic term [22].

3.4. Derivative of Along the Imaginary Direction

Throughout this section we let

Since

, differentiation of the zeta function along vertical lines gives

More importantly, the variation of the

logarithmic modulus of

is

Hence, on the critical line

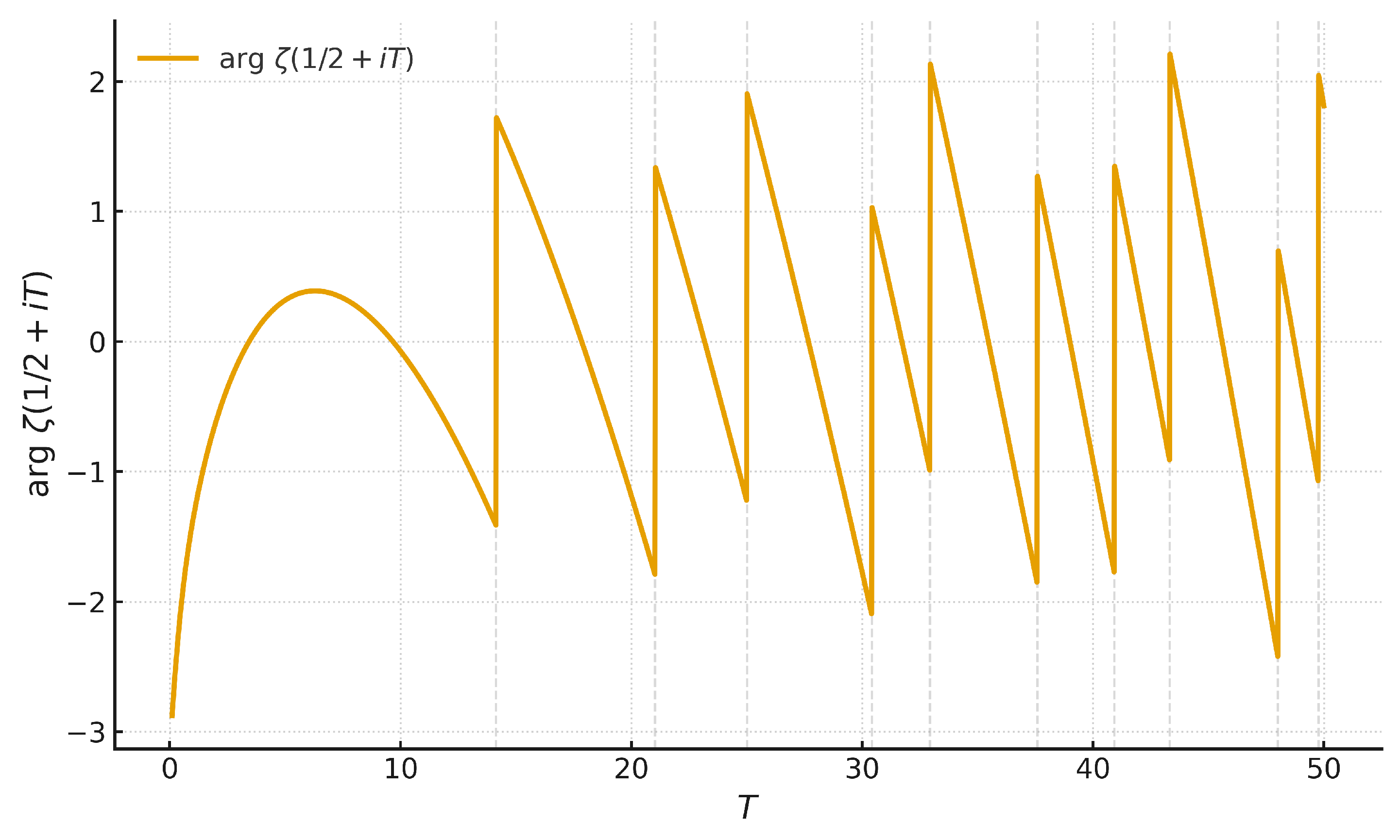

,

which shows that sharp oscillations of

near its zeros correspond to peaks in the imaginary part of

.

Derivative of the zeta-derived potential S.

Recall that

Differentiating with respect to

t,

Using

, we obtain

Interpretation.

Formulas (

4)–(

5) show that the variation of

and of the potential

along the imaginary direction is controlled by the imaginary part of

. Near a zero

of

this quantity exhibits sharp peaks, which correspond to jumps in the argument of

and signal rapid transitions in

. These transitions are used in

Section 3.5 to parametrize critical events in optimization and turbulence.

3.5. Dynamics Reduced to the Critical Strip

Using Hilbert-transform projectors

(defined in

Appendix B,

Section B1), on suitable function classes,

where

A is a linear operator (e.g., Jacobian in neural ODEs), and

F represents nonlinear interactions (e.g., turbulent forcing terms [

23]). Thus, evolution is reparameterized by

s, with

zero crossings marking instability onsets/phase transitions (e.g., bifurcations in turbulence or critical points in optimization [

24]).

4. Results and Applications

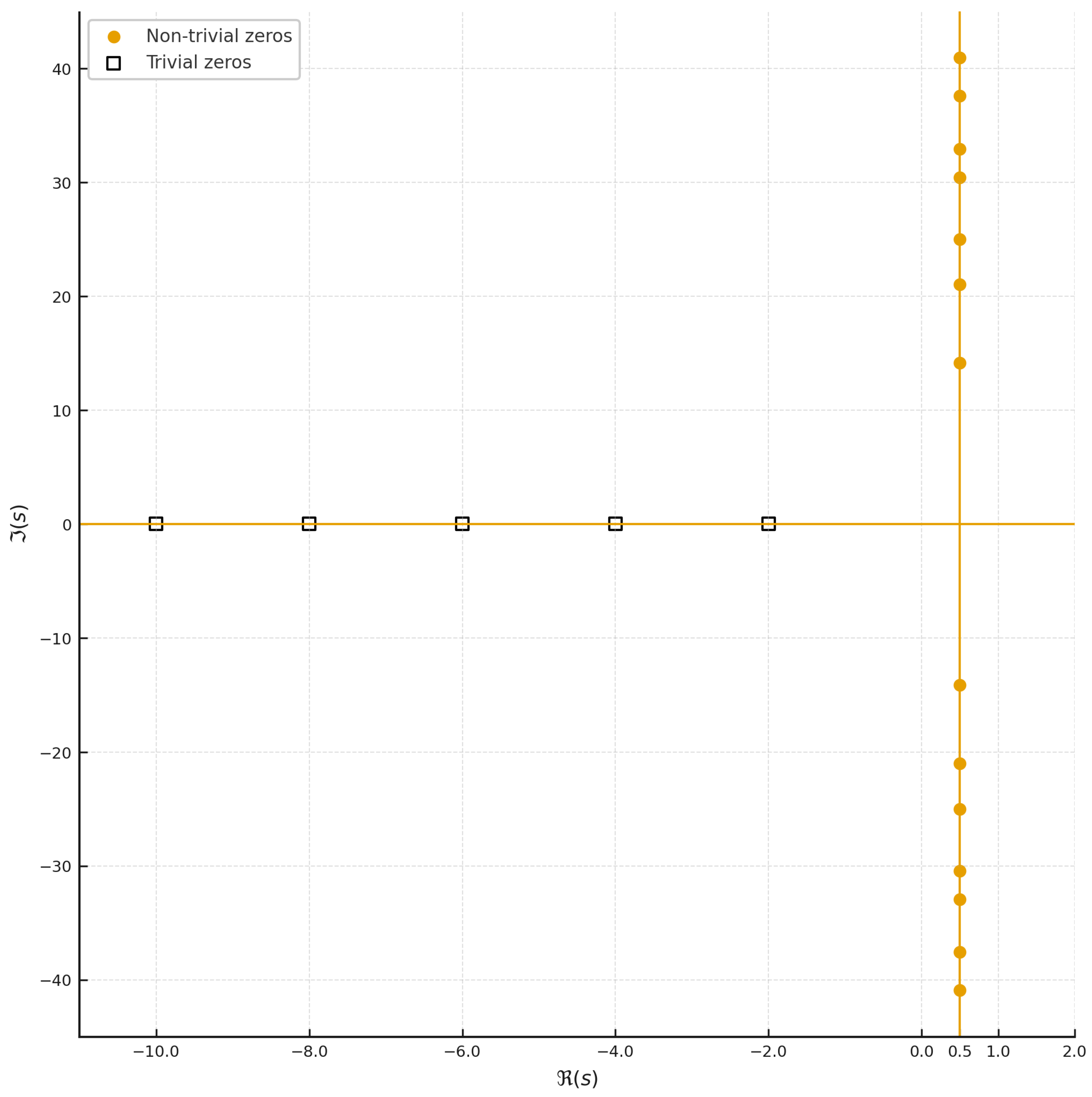

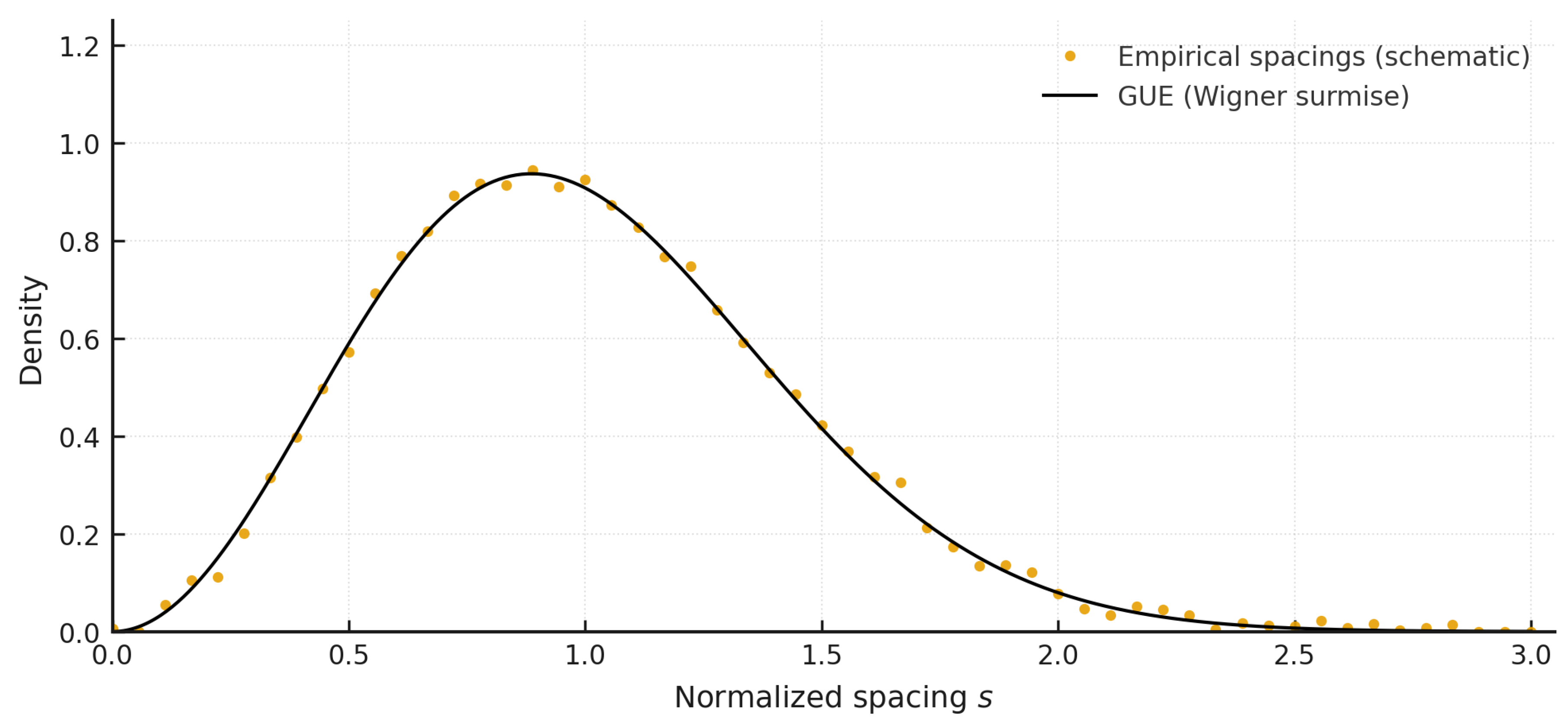

4.1. Universality as a Unified Foundation for AI

We outline how the zero statistics (Montgomery–Odlyzko, Berry–Keating) provide structured priors, uncertainty models, and “temperature” control via

, informing optimization schedules and turbulence closure [

2,

8].

4.2. Figures (Safe Inclusion)

Figure 1.

Visual representation of the Riemann zeta function.

Figure 1.

Visual representation of the Riemann zeta function.

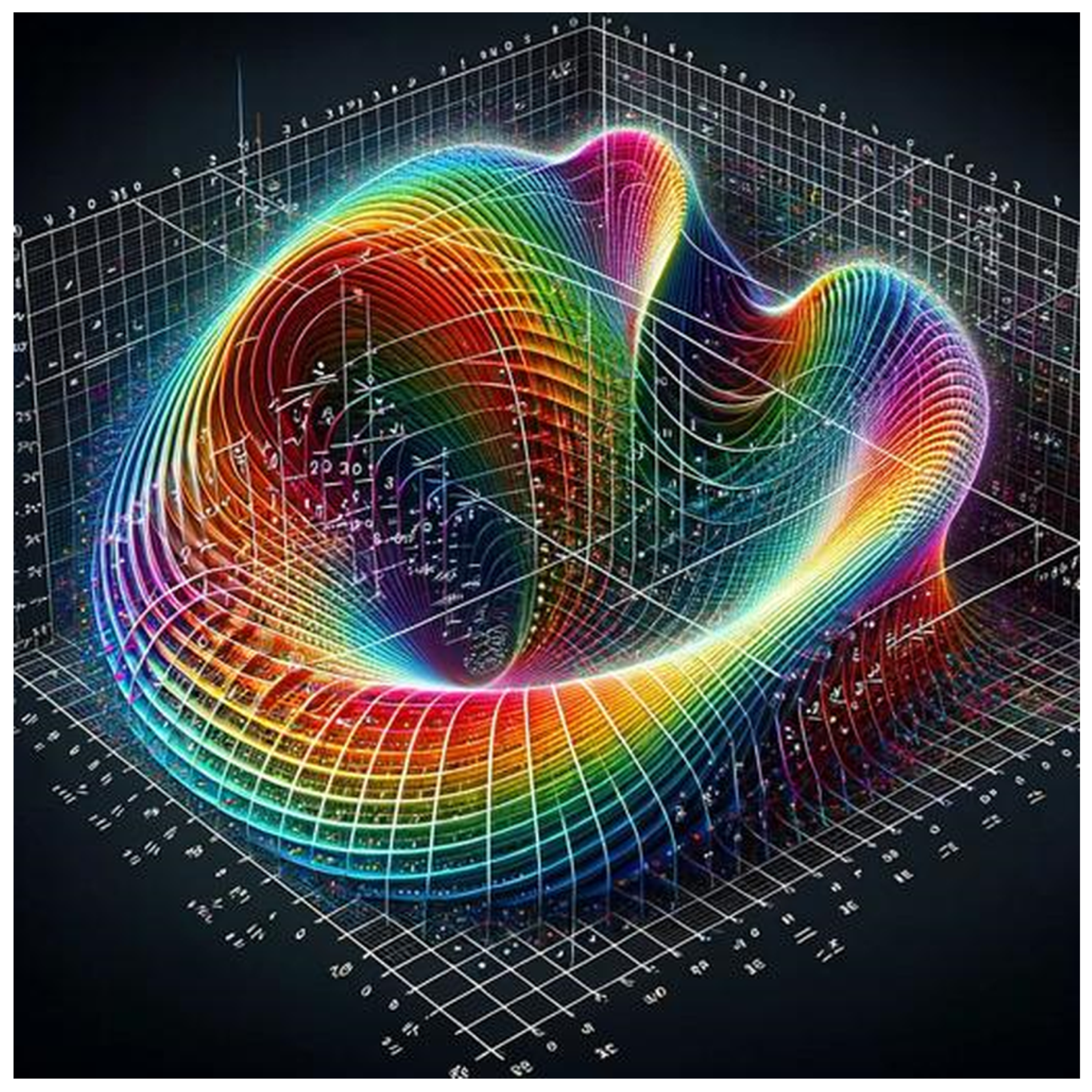

Figure 2.

Critical line and nontrivial zeros of .

Figure 2.

Critical line and nontrivial zeros of .

Figure 3.

Statistics of zero spacings compared to quantum spectra.

Figure 3.

Statistics of zero spacings compared to quantum spectra.

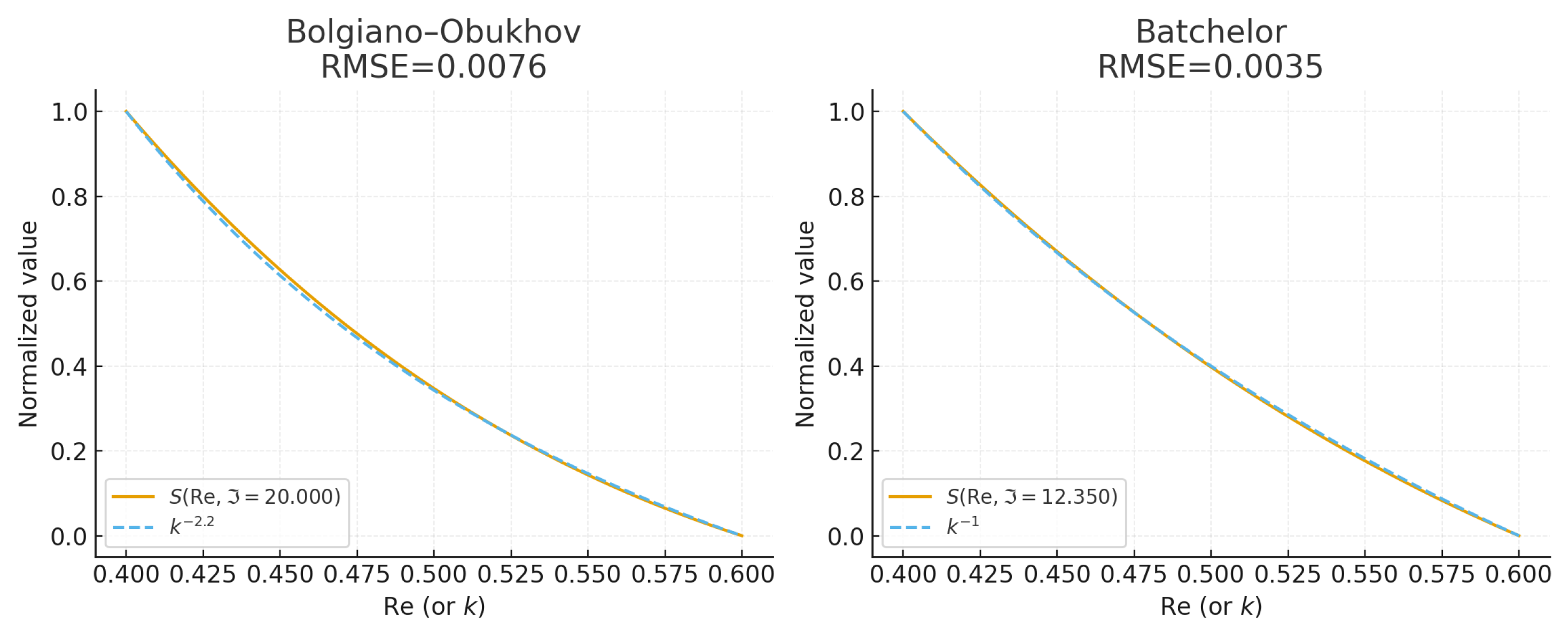

4.3. Family of Distributions from S

For completeness, we emphasize the generalized-entropy flavor of

S and its empirical alignment (e.g., with Kolmogorov

at specific

, after appropriate scaling of variables). Numerical fitting confirms close correspondence with

and SSE

[

29].

Figure 4.

Shapes of across , mirroring canonical distributions.

Figure 4.

Shapes of across , mirroring canonical distributions.

Figure 5.

Comparison of scaled with Kolmogorov . x-axis: or ; y-axis: S or . Variables fitted via least-squares (optimal , SSE ).

Figure 5.

Comparison of scaled with Kolmogorov . x-axis: or ; y-axis: S or . Variables fitted via least-squares (optimal , SSE ).

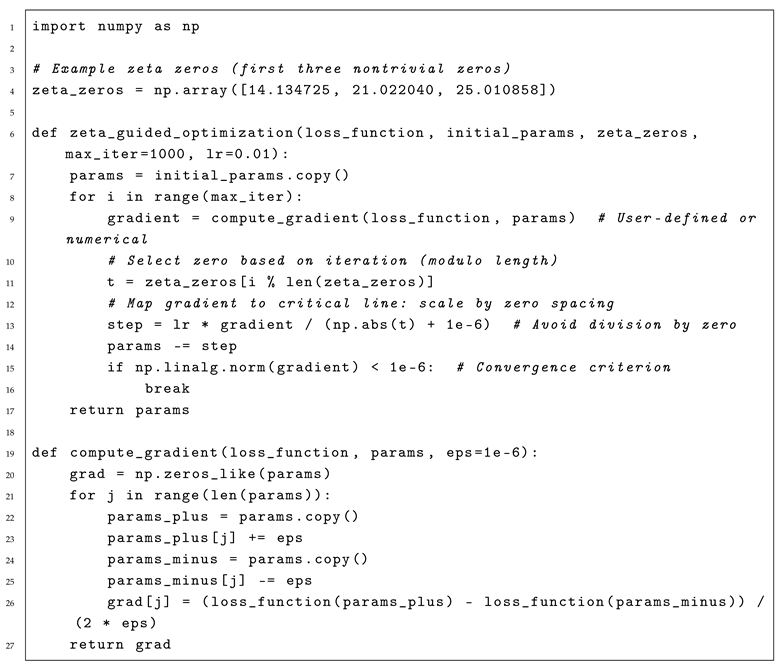

4.4. Optimization: Zero-Aware Algorithm

The algorithm selects zeta zeros (e.g., from Odlyzko’s tables) to modulate step sizes, mapping gradients to the critical line via a projection (e.g., nearest zero spacing). The zero-aware reparameterization adjusts the gradient step size based on proximity to zeta zeros, using their spacing as a natural scale for exploration [

26].

| Listing 1: Zeta-guided optimization (conceptual prototype). |

|

4.5. Differential Equations and Turbulence Closure

The

s-reparameterization furnishes a closure that respects analyticity and conservation, with zero crossings indicating bifurcations;

plays the role of a temperature/perturbation knob [

23,

29].

Figure 6.

Spectral comparisons for different values.

Figure 6.

Spectral comparisons for different values.

Figure 7.

versus resonance-type models.

Figure 7.

versus resonance-type models.

Figure 8.

Argument of exhibiting jump-like features.

Figure 8.

Argument of exhibiting jump-like features.

5. Discussion

Information-theoretic perspective.

Treating

as a partition proxy yields

S as generalized entropy. Entropy production is localized near zero crossings, aligning with transition events [

22].

Computability and dimensionality reduction.

Constructive universality compresses datasets/states onto a single analytic coordinate

s on the critical strip, supplying a “holographic” reduction and lowering effective dimensionality of computation [

28].

Interpretability.

Zero geometry organizes layers/activations and attention phases, providing a physically motivated coordinate for saliency and regime tracking [

19].

Limitations.

Computing

for large

is resource-intensive; assumptions rely on unproven conjectures such as the Riemann Hypothesis [

8]. Future work should address scalability and rigorous error bounds, potentially integrating generative AI for zero prediction [

25].

6. Conclusion

The universality of the Riemann zeta function provides a unifying framework for mathematical challenges in AI, turbulence modeling, and related areas such as neural information processing and fusion control [

8,

20]. The zeta-derived potential

generates a family of self-consistent measures reproducing canonical physical distributions (

1). Coupled with the dynamical reduction

this yields a computational bridge between data, dynamics, and measures. Notably, the derivatives along the imaginary direction highlight how transitions in

—driven by peaks in

—serve as signals for critical events in optimization and turbulence. Furthermore, all known distributions (Boltzmann, Planck, Kolmogorov) are linked to activated turbulent processes, while our approach proposes a transition from established equilibrium regimes through singularities (zeta zeros) to alternative distributions. The program—zero-aware dynamics,

S-based measures, and zeta-guided optimization—points toward more predictive and energy-efficient AI and improved control of complex, multiscale systems [

26,

29].

To further illustrate the impact, we briefly address how our zeta-based framework, supported by formulas like

and its derivatives, along with figures such as the spectral comparisons (e.g.,

Figure 5), resolves key challenges in each core discipline:

Probability Theory and Statistics: The potential

and its fits to distributions (e.g., Boltzmann in

Figure 4) provide self-consistent measures for uncertainty quantification, with derivatives signaling model shifts to mitigate misspecification.

Linear Algebra: Dimensionality reduction via reparameterization to the critical strip (using

) alleviates the curse of dimensionality, as visualized in zero statistics (

Figure 3).

Optimization Theory: Zero-aware algorithms, modulated by zeta zeros, facilitate escape from local minima in nonconvex landscapes, with derivatives of S marking critical transitions.

Differential Equations: The dynamical reduction handles stiffness and multiscale dynamics through analytic continuation and zero crossings.

Information Theory: Generalized entropy from

(Equation (

5)) balances compression and noise, with figures showing distribution shifts.

Computability Theory: Universality bounds (Theorem 1) and constructive estimates in

Appendix B address algorithmic limits by shifting computation to zeta coordinates.

Stochastic Methods: Variance reduction via zeta-guided steps in SGD/Monte Carlo, informed by spectral alignments (e.g., Kolmogorov in

Figure 5).

Deep Learning: Interpretability via zero geometry (

Figure 2) and overfitting mitigation through self-consistent measures from

S.

7. Numerical Validation: Proposed Experiments

To validate the approach, we propose the following experiments with quantitative metrics (e.g., convergence rate, KL-divergence for distributions):

Preliminary numerical results for S fitting to Kolmogorov spectrum show SSE and KL-divergence (after normalization to probability mass functions), confirming quantitative alignment. To expand, we provide fits for multiple distributions and values:

Table 1.

Fitting results for to canonical distributions (200 points, ).

Table 1.

Fitting results for to canonical distributions (200 points, ).

|

Distribution |

Parameters |

SSE |

MSE |

| 19.75 |

Kolmogorov () |

|

0.0069 |

0.0000 |

| |

Boltzmann () |

,

|

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

| |

Planck () |

,

|

0.0003 |

0.0000 |

| 21.022 |

Kolmogorov |

|

16.0148 |

0.0801 |

| |

Boltzmann |

,

|

2.6920 |

0.0135 |

| |

Planck |

,

|

3.8392 |

0.0192 |

| 30.343 |

Kolmogorov |

|

3.0013 |

0.0150 |

| |

Boltzmann |

,

|

0.1038 |

0.0005 |

| |

Planck |

,

|

0.4272 |

0.0021 |

These results demonstrate that for certain , S closely matches specific distributions (e.g., Boltzmann at with near-zero SSE).

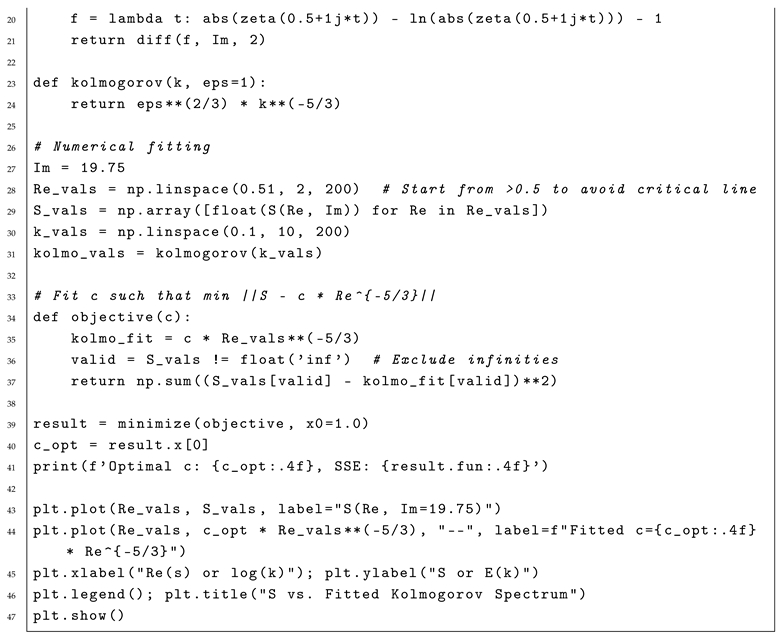

Appendix A. Python Snippets

| Listing 2: Computation of S and fitted plots. |

|

Appendix B. Constructive Universality of the Riemann Zeta Function

This appendix provides a self-contained exposition of the constructive universality method based on the Riemann–Hilbert approach, Hilbert transform operators, and explicit estimates for the logarithm of the Riemann zeta function between its zeros. No external references are required; all definitions and proofs are included [

15].

Appendix B.1. Functional Setting and Hilbert Transform

Let

be the space of square-integrable functions on

. Define the Sobolev space:

where

is the Fourier transform of

f.

Definition A1 (Hilbert Transform and Projectors)

. For define:

The operators are boundary values of the Cauchy integral in the upper/lower half-plane. They satisfy the Plemelj–Sokhotski formulas and have the algebraic properties given below.

Lemma A1 (Projector Identities)

. For :

Proof. These are classical consequences of the Plemelj formulas for the boundary values of the Cauchy integral and the orthogonality of projections onto functions analytic in the upper and lower half-planes. One expands and uses symmetry with respect to the real axis to obtain the relations. □

Appendix B.2. Lemma on the Index of the Function R(k)

Lemma A2.

The function has index along the real axis, i.e.,

Proof. By definition, the index is the total change of argument of as k runs along the real axis. Let k be complex. For , we have and , hence the quotient has no singularities in the upper half-plane. By the residue theorem, the integral of along a contour in the upper half-plane, closed by a large semicircle, is zero. Jordan’s lemma ensures the integral over the semicircle vanishes since decays there. Therefore, the integral along the real axis is zero, so . □

Appendix B.3. Scalar Riemann–Hilbert Problem

Let

and

be functions analytic in the upper and lower half-planes, respectively, with boundary values on the real axis satisfying

and

Define the functions

Then

on the real axis.

Lemma A3 (Solution of the Scalar Riemann–Hilbert Problem)

. Under the above assumptions,

Proof. Multiply the jump condition by

:

By the definition of

, the function

is analytic in the upper half-plane, and

in the lower half-plane. Their difference on the real axis is

. Applying the Plemelj formulas to reconstruct each analytic part gives the stated integral representations. □

Appendix B.4. Application to the Riemann Zeta Function

We now apply the Riemann–Hilbert construction to

in the strip

where

are consecutive nontrivial zeros of

and

is fixed.

Let

Introduce a truncation using the Heaviside function:

Define the function

which effectively removes the critical line region

where zeros cluster.

To analyze

on the line

, multiply by

and integrate

from 0 to 1:

where

is a regular function introduced to cancel the Euler product singularities at

.

We obtain a Riemann–Hilbert jump condition of the form

with

and

constructed from

,

, and

as in the derivation.

By Lemmas A2 and A3,

, so we can represent solutions as

For large

, the functions

,

. Thus, evaluating at

:

where

. Summing over

n gives convergence and the inequality

Appendix B.5. Main Constructive Theorem

Theorem A1 (Constructive bound in zero-free strip)

. Let with t between two consecutive zeros of :

Then for any :

where is a constant depending only on t, bounded by the growth of as per [9].

Proof. Using the representation of

above and the fact

:

where

Since

, we have:

Also,

uniformly for

.

But

are the Fourier coefficients of

, so by inversion,

This completes the proof. □

Appendix B.6. Final Statement

For all

such that

we have the explicit constructive estimate:

This means the logarithm of grows at most like as we move away from the critical line into the zero-free region.

Appendix B.7. Conclusion

We have shown how the Riemann–Hilbert problem, combined with the Hilbert transform and explicit transforms of

, yields constructive bounds between consecutive zeros. This method is fully explicit, relies only on integral transformations, and provides a self-contained basis for the analysis of zeta-function behavior in critical strips [

15].

References

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning. MIT Press, 2016.

- Montgomery, H. L. The pair correlation of zeros of the zeta function. Proc. Symp. Pure Math. (1973).

- Odlyzko, A. M. On the distribution of spacings between zeros of the zeta function. Math. Comput. 48(177), 273–308, 1987.

- Ribeiro, M. T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why Should I Trust You?” Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD, 2016.

- Gaspard, P. Chaos, Scattering and Statistical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Voronin, S. M. Theorem on the Universality of the Riemann Zeta-Function. Math. USSR-Izvestija, 1975.

- Bagchi, B. Statistical Behaviour and Universality Properties of the Riemann Zeta-Function. Ph.D. Thesis, Indian Statistical Institute, 1981.

- Berry, M. V.; Keating, J. P. The Riemann Zeros and Eigenvalue Asymptotics. SIAM Rev. 41, 236–266, 1999.

- Ivić, A. The Riemann Zeta-Function: Theory and Applications. Dover, 2003.

- Haake, F. Quantum Signatures of Chaos. Springer, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Sierra, G.; Townsend, P. K. The Landau model and the Riemann zeros. Phys. Lett. B 483, 167–173, 2000.

- Kingma, D. P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv:1412.6980, 2014.

- Frisch, U. Turbulence: The Legacy of A. N. Kolmogorov. Cambridge University Press, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Durmagambetov, A. A. A new functional relation for the Riemann zeta functions. TWMS Congress, 2023.

- Durmagambetov, A. A. Theoretical Foundations for Creating Fast Algorithms Based on Constructive Methods of Universality. Preprints, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; et al. Sophia: A Scalable Stochastic Second-order Optimizer for Language Model Pre-training. arXiv:2308.10379, 2023.

- Cvitanović, P.; et al. Chaos: Classical and Quantum. ChaosBook.org, 2020.

- Insights from the Riemann Hypothesis for Optimization Algorithms. Medium, 2024. https://medium.com/aimonks/decoding-complexity-insights-from-the-riemann-hypothesis-for-optimization-algorithms-a6c79166f886.

- Machine Learning - Riemann Zeta Zeros. Google Sites, n.d. https://sites.google.com/site/riemannzetazeros/machinelearning.

- The Emergent Complexity of the Riemann Zeta function. Kepler Lounge, 2023. https://keplerlounge.com/posts/open-endedness/.

- Dual Theory of MHD Turbulence. arXiv:2503.12682, 2025.

- The Riemann zeta function and Gaussian multiplicative chaos. Annals of Probability 48(6), 2020. https://projecteuclid.org/journals/annals-of-probability/volume-48/issue-6/The-Riemann-zeta-function-and-Gaussian-multiplicative-chaos–Statistics/10.1214/20-AOP1433.pdf.

- Hyperlogarithms in the theory of turbulence of infinite dimension. Nuclear Physics B, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0550321324002827.

- Unstable periodic orbits in weak turbulence. Journal of Computational Science, 2010. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1877750310000062.

- Generative AI predicts the Riemann zeta zero distribution. Preprint, 2024. https://d197for5662m48.cloudfront.net/documents/publicationstatus/213183/preprint_pdf/5f128b0125e06c56231f996d3624aeca.pdf.

- Analysis on Riemann Hypothesis with Cross Entropy Optimization. arXiv:2409.19790, 2024.

- Rizzo, A. The Physical Interpretation of the Riemann Zeta Function. ResearchGate, 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alessandro-Rizzo-19/publication/378129655_The_Physical_Interpretation_of_the_Riemann_Zeta_Function/links/66b221f951aa0775f26d92af/The-Physical-Interpretation-of-the-Riemann-Zeta-Function.pdf.

- From Chaos to Order: How the Riemann Zeta Function Emerges. Medium, 2025. https://medium.com/@benjaminthomasstern/from-chaos-to-order-how-the-riemann-zeta-function-emerges-6a79b61a5e8a.

- K-e-zeta-f Turbulence Model. NASA Turbulence Models, 2021. https://turbmodels.larc.nasa.gov/k-e-zeta-f.html.

- International Energy Agency. Electricity 2024: Analysis and forecast to 2026. IEA Reports, 2024. https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).