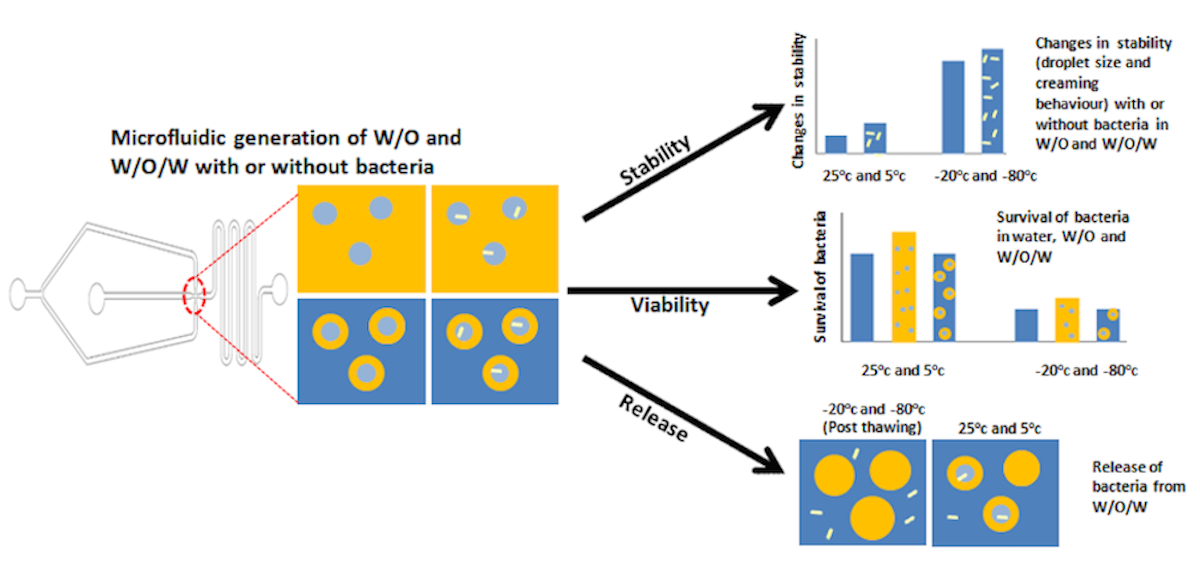

3.1 The Effect of Storage on Droplet Size Change

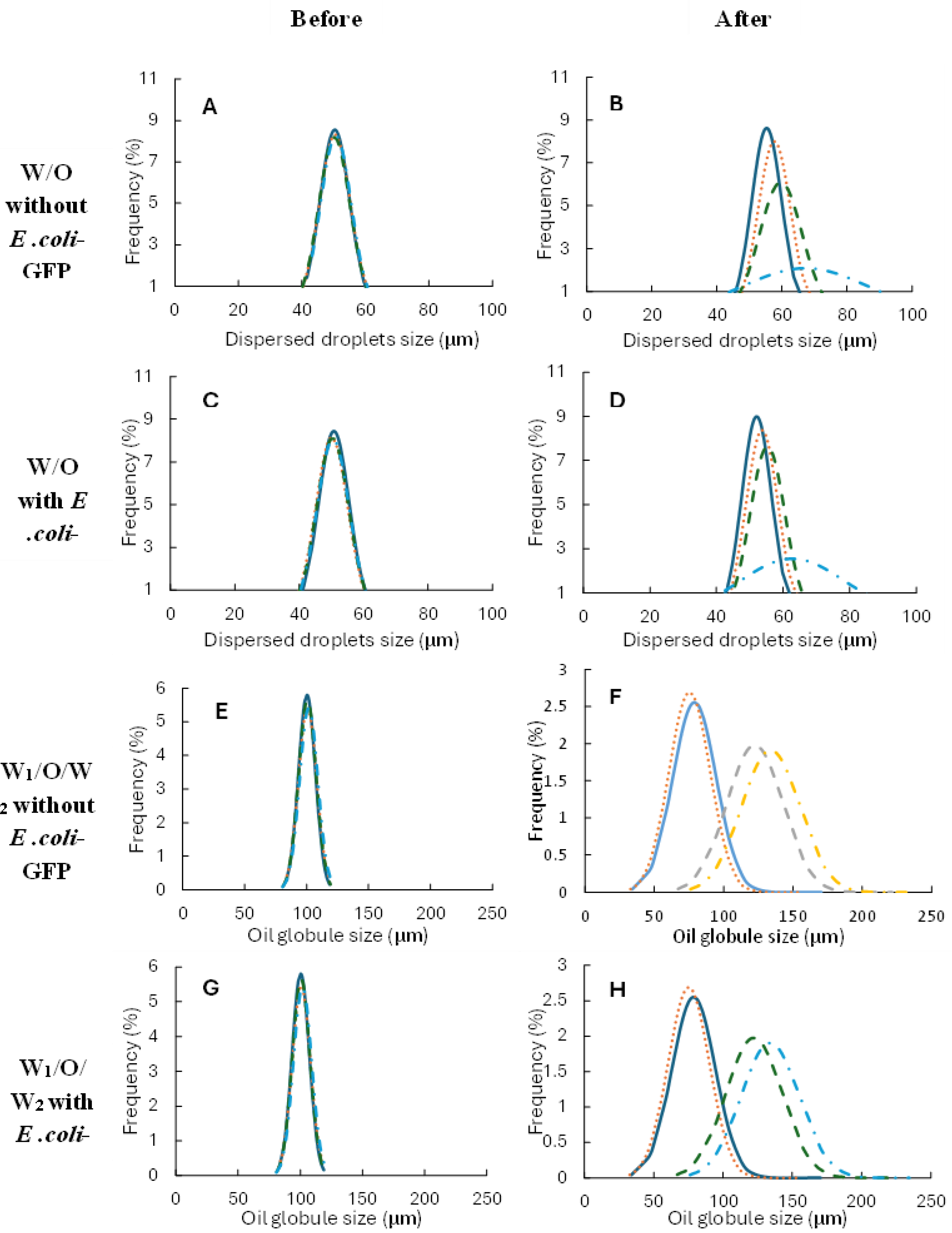

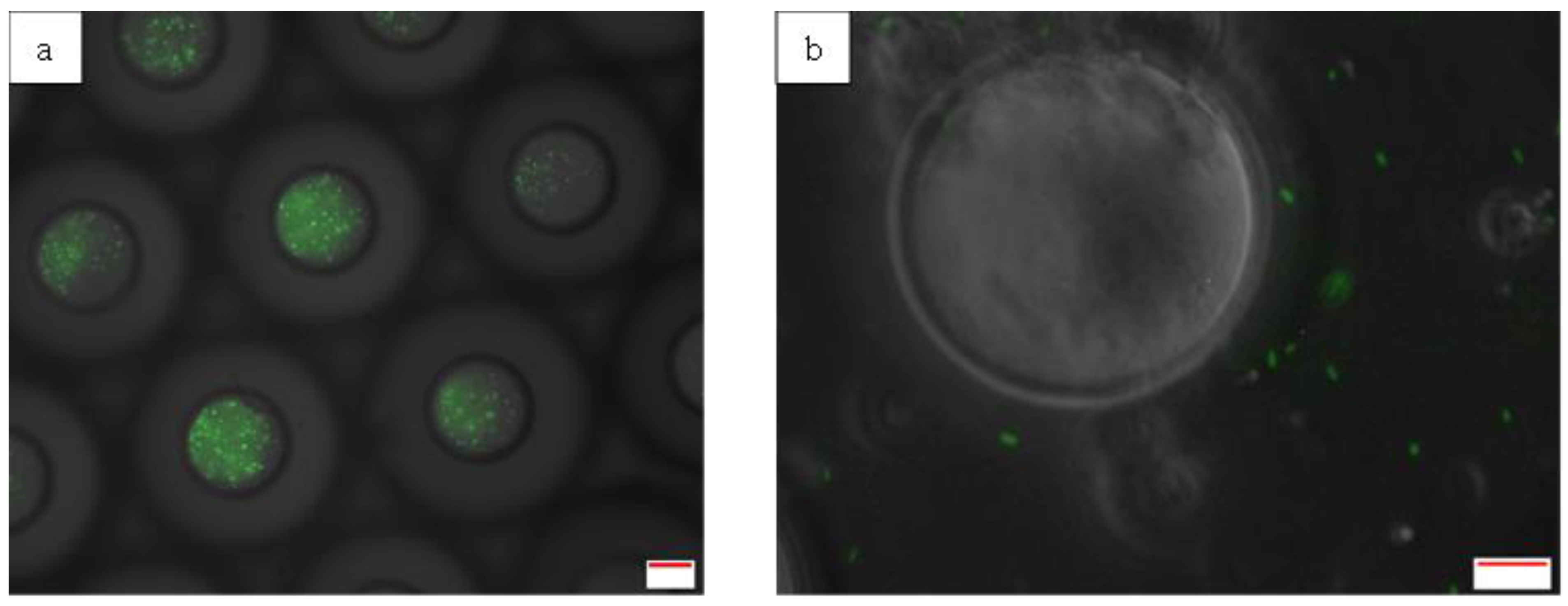

Monodispersed droplet for both single and double emulsion droplet were observed for all samples with or without

E. coli-GFP with a CV value of approximately 9% for single emulsion droplet and 7% for double emulsion droplet prior to the storage test as observed in

Figure 1 (A, C, E, G) and

Table 1. The results indicate the ability of the flow-focusing microfluidic devices in producing highly monodispersed droplet and the presence of

E. coli-GFP does not affect droplet formation. For samples of single emulsion droplet, no significant change (p>0.05) in droplet size was observed after storage at 25°C and 5°C (

Table 1) for both samples with and without bacteria. The droplet remains monodispersed with only 0.1-0.2% change in the value of the coefficient of variation (CV). However, a significant change (p<0.05) in droplet size and distribution were observed after 24 hours of storage for samples stored at freezing temperatures of -20°C and -80 °C for both sample with and without bacteria. The highest change was observed for samples stored at -80°C whereby the CV value increases from 9.6% to 28.3% for samples without

E. coli-GFP indicating a polydisperse distribution of droplet (CV values of higher than 25% are regarded as polydisperse). Comparing samples with or without

E. coli-GFP, change in droplet stability was minimized with the presence of

E. coli-GFP whereby a smaller change in average droplet size and CV was observed with samples containing

E. coli-GFP as compared to samples without

E. coli-GFP.

A significant change (p<0.05) in the size of oil globule after 24 hours of storage was observed for all double W

1/O/W

2 emulsion samples whereby a decrease in average oil globule size was observed for samples stored at 25°C and 5°C. However, presence of large droplet was also observed with up to 170 µm in droplet size (

Figure 1 F, H). Samples stored at freezing temperatures of -20°C and -80°C, showed an increase (p<0.05) in droplet size after storage (

Table 1). Samples containing

E. coli-GFP show better droplet stability as compared to samples without

E. coli-GFP indicating the ability of bacterial cells in maintaining droplet stability during cold temperature storage. Complete external coalescence occurred between the inner W1 droplet with the outer W2 phase after 24 hours of storage forming single oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion.

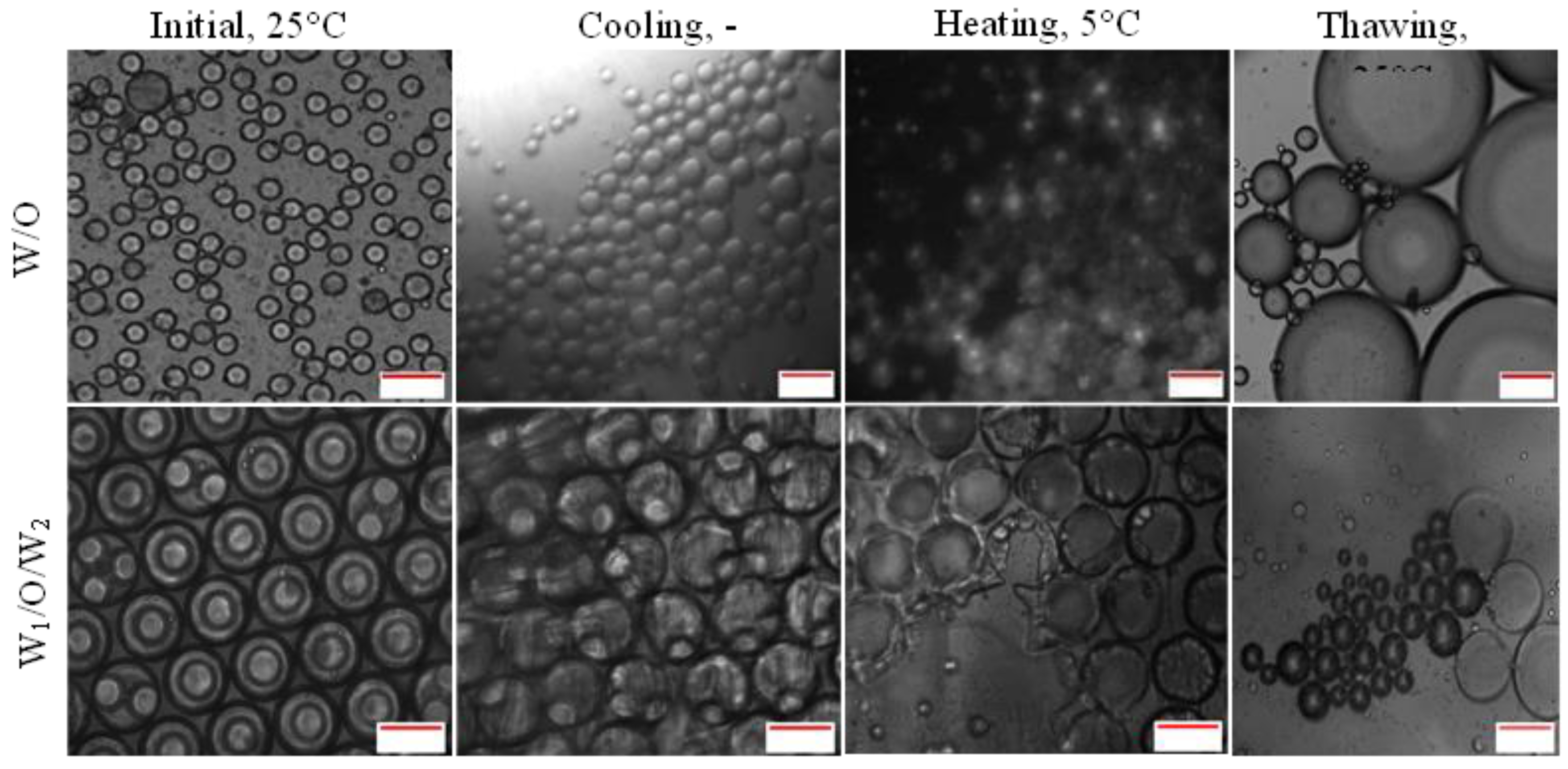

The storage of single W/O samples at -20°C caused the solidification of the aqueous phase and partial crystallization of the oil phase whereas storing the samples at -80 °C completely solidifies the emulsions. With broad crystallization temperature as opposed to pure water that exhibits a sharp crystallization curve, it is quite difficult to determine the exact crystallization temperature of the soybean oil due to the presence of lipids and a mixture of molecules. It has been reported previously that soybean oil is partially crystallized at a temperature between -10°C to approximately -20°C whereby below this temperature, the soybean oil is most likely to become solid (Tieko Nassu and Gonçalves, 1999; Harada and Yokomizo, 2000; Mezzenga, Folmer and Hughes, 2004; Ishibashi, Hondoh and Ueno, 2016). Several destabilization mechanisms of single W/O emulsions during the freeze-thaw process have been proposed depending on the droplet arrangements in the emulsion (Aronson and Petko, 1993; Aronson et al., 1994; He and Chen, 2002; Chen and He, 2003; Lin et al., 2007). The destabilization of loosely packed W/O emulsion droplet is due to the collision-mediated coalescence (Lin et al., 2007). This process is triggered by the uneven crystallization of the polydisperse water droplet in the emulsion whereby the collision between the smaller still-liquid water droplet with protruding ice crystals of the larger frozen droplet punctures the membrane surrounding the smaller still-liquid water droplet. This leads to the heterogeneous nucleation and crystallization of the smaller water droplet that coalesces forming larger droplet upon thawing (Lin et al., 2007; Ghosh and Rousseau, 2009b). However, this may not be the case for single W/O droplet generated by the microfluidic device as it is highly monodispersed and therefore, minimizes the heterogeneous crystallization of the water droplet and the effect of collision-mediated coalescence.

Although the effect of collision-mediated coalescence was minimized, the destabilization of W/O droplet was still observed and is mainly attributed to the static and upright storage of the samples during freezing that caused the inevitable sedimentation of the water droplet making them closely packed. For densely packed emulsions, the destabilization mechanism is induced by the direct breakage of interfacial films and emulsion inversion (Aronson and Petko, 1993; Aronson

et al., 1994). The direct breakage of the droplet interfacial film occurred as neighbouring droplet crystallizes and expands causing destabilization. Droplet expansion pressed the droplet closely together while crystallized droplet punctured the interfacial film of neighbouring still-liquid droplet leading to droplet rupture (Ghosh and Coupland, 2008). This caused the content of the ruptured droplet to flow out and formed a link between the two frozen droplets resulting in flocculation as observed in this study in

Figure 2 b (van Boekel and Walstra, 1981). During the thawing process, the crystal network collapsed and the two partially coalesced droplet merged together forming a larger droplet (complete coalescence) as observed in

Figure 2 d (Vanapalli, Palanuwech and Coupland, 2002). Droplet crystallization and expansion also resulted in the thinning of the oil and surfactant layer around the aqueous phase that accelerates droplet coalescence during the melting process (Ghosh and Rousseau, 2009b). Emulsion inversion, as reported by Aronson and Petko (1993) involves the rearrangement of ice crystals and the still-liquid oil that leads to the presence of distinct oil droplet within the ice structure. However, this may not be the case for samples tested in this study as it occurs mainly in densely packed emulsions containing distinctively high-volume fraction of the dispersed phase (Vanapalli, Palanuwech and Coupland, 2002).

It has been reported previously that the stability of water-in-oil droplet during the freeze-thaw process depended on the freezing sequence of the oil and aqueous phases and also the type of surfactants used (Ghosh and Rousseau, 2009b). The freezing sequence between the oil and aqueous phase may depend on the type of oil used as some oils may have a lower freezing point or higher freezing point than the aqueous phase. Ghosh and Rousseau (2009) reported that for single water-in-oil emulsions, instability is mostly evident in samples with the oil phase that crystallizes first prior to the aqueous phase and when the emulsifier is in liquid-state during the freezing process. For emulsion containing soybean oil, the oil phase crystallizes at a much lower temperature than the aqueous phase in which droplet destabilization should be minimized. However, significant changes (p < 0.05) in droplet size distribution were observed for samples stored at -80°C. At -80°C, the gradual crystallization of the oil phase due to difference in the melting fraction of fats in soybean oil as the high-melting fraction crystallizes first followed by the low-melting fraction (Ishibashi, Hondoh and Ueno, 2016) resulted in the ice crystals to be forced into the still-liquid oil phase forming a region with highly concentrated ice crystals (Ghosh and Coupland, 2008; Degner et al., 2013). During thawing, as the oil melts, the ice crystals will immediately coalesce as a further increase in temperature caused the aqueous droplet to melt and fuse together (Degner et al., 2014).

Previous study reported on the separation of the W

1 phase from the double emulsion droplet where the separated W

1 phase retained in the W

2 phase supported by a very thin and complex layer of oil and surfactants (Mohd Isa

et al., 2021). This also caused the reduction in oil globule size as the W

1 phase escaped into the W

2 phase. Similar behaviour was also seen for samples of double emulsion kept at a lower temperature of 5°C. However, for double emulsion samples kept at a much lower temperature of -20°C and -80°C, significant (p < 0.05) increase in the average oil globule size and change in the droplet size distribution was observed. Interestingly, the inner W

1 phase remains intact in the W

1/O/W

2 during the freezing process as shown in

Figure 2 f and droplet separation process was not observed.

The destabilization mechanism of the double emulsion droplet is mainly attributed to the coalescence between the inner W

1 phase and the outer W

2 phase which is termed as external coalescence (Magdassi and Garti, 1987; Rojas and Papadopoulos, 2007). In contrast to single emulsions droplet whereby the droplet destabilization process occurred throughout the freeze and thawing processes, the external coalescence of double emulsion occurred during the thawing process of the emulsions while the inner W

1 phase remains intact during the freezing process (Rojas and Papadopoulos, 2007). The thawing process caused deformation of the inner W

1 phase followed by the complete burst of droplet due to external coalescence and is mainly affected by the size of the inner W

1 phase and surfactant concentration. According to Rojas and Papadopoulos (2007), the determined threshold of the W

1 inner aqueous phase size to the oil globule size ratio is 0.3 in which above, resulting in coalescence upon thawing. In addition, emulsion droplet with thick surfactant layers creates a repulsive force between the W

1 inner phase and the O/W

2 interface that improves droplet stability against external coalescence (Wangqi Hou and Papadopoulos, 1996). A similar mechanism was observed in this study whereby the inner W

1 droplet remain intact during the freezing process and rapid freezing prevents the droplet from splitting (

Figure 2 e-f). Emulsions destabilization only occurred during the thawing process for both samples kept at -20°C and -80°C. As the frozen oil melts at a lower temperature during the thawing process of samples kept at freezing temperatures, the liquid oil flows through the cracks and gaps created by the gradual thawing of the aqueous phase (

Figure 2 g) leading to absence of the oil layer that separates the inner W

1 phase from the outer W

2 phase. This accelerates the external coalescence of the aqueous phase as it melts completely with increase in temperature forming single oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion. Moreover, the droplet distribution graph that tails towards the larger droplet size with sharp distribution at the smaller droplet size region shows evidence of oil globule coalescence after the thawing process that is in contrast to droplet instability that was induced by Ostwald ripening whereby it tends to form sharp droplet distribution at the larger size region with tailing at smaller droplet size region (Aronson and Petko, 1993).

The presence of bacteria also affected droplet stability, especially for single emulsion droplet. As the PGPR surfactant remained liquid during the freezing process (Ghosh and Rousseau, 2009), it is most likely retained in the oil phase and withdrawn from the ice crystals as the aqueous phase freezes. These accelerate the coalescence process of the aqueous phase as the emulsions warmed up. However, the presence of E. coli-GFP on the interface minimizes the droplet coalescence during the thawing process as they are most likely crystallized on the interface. The E. coli-GFP was observed to have a high affinity towards the soybean oil as determined by the BATH assay (Figure S2). Changes in bacterial characteristics due to storage in freezing temperatures ease the attachment of the bacteria onto the interface making the droplet less susceptible to rupture. The stabilization effect of bacteria may be similar to emulsion stabilization due to surfactant crystallization and presence of particles on the droplet interface forming Pickering emulsion as reported previously by Ghosh and Rousseau (2009) and Zhu et al. (2017). The crystallization of glycerol monostearate (GMS) at 25°C creates a crystalline shell around the water droplet that helps in preventing crystallization damage between the adjacent water droplet and coalescence during the thawing process which is in contrast to emulsions containing molten PGPR (Ghosh and Rousseau, 2009). According to Zhu et al. (2017), the addition of heated soy and whey protein in emulsions improves droplet stability against freeze/thaw cycling due to Pickering stearic stabilization. However, further study is still required to confirm the effect of bacteria on droplet stability in freezing conditions.

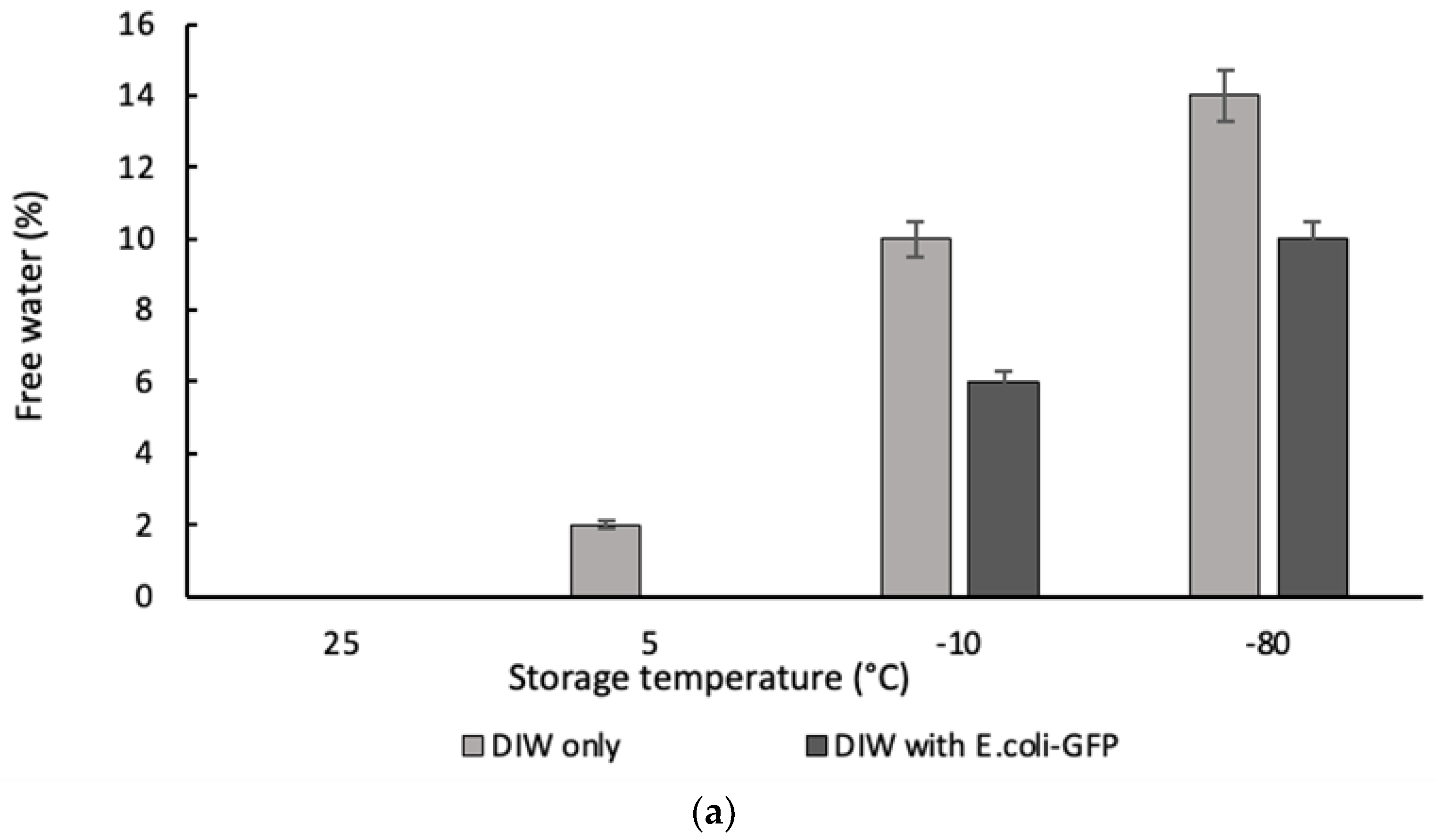

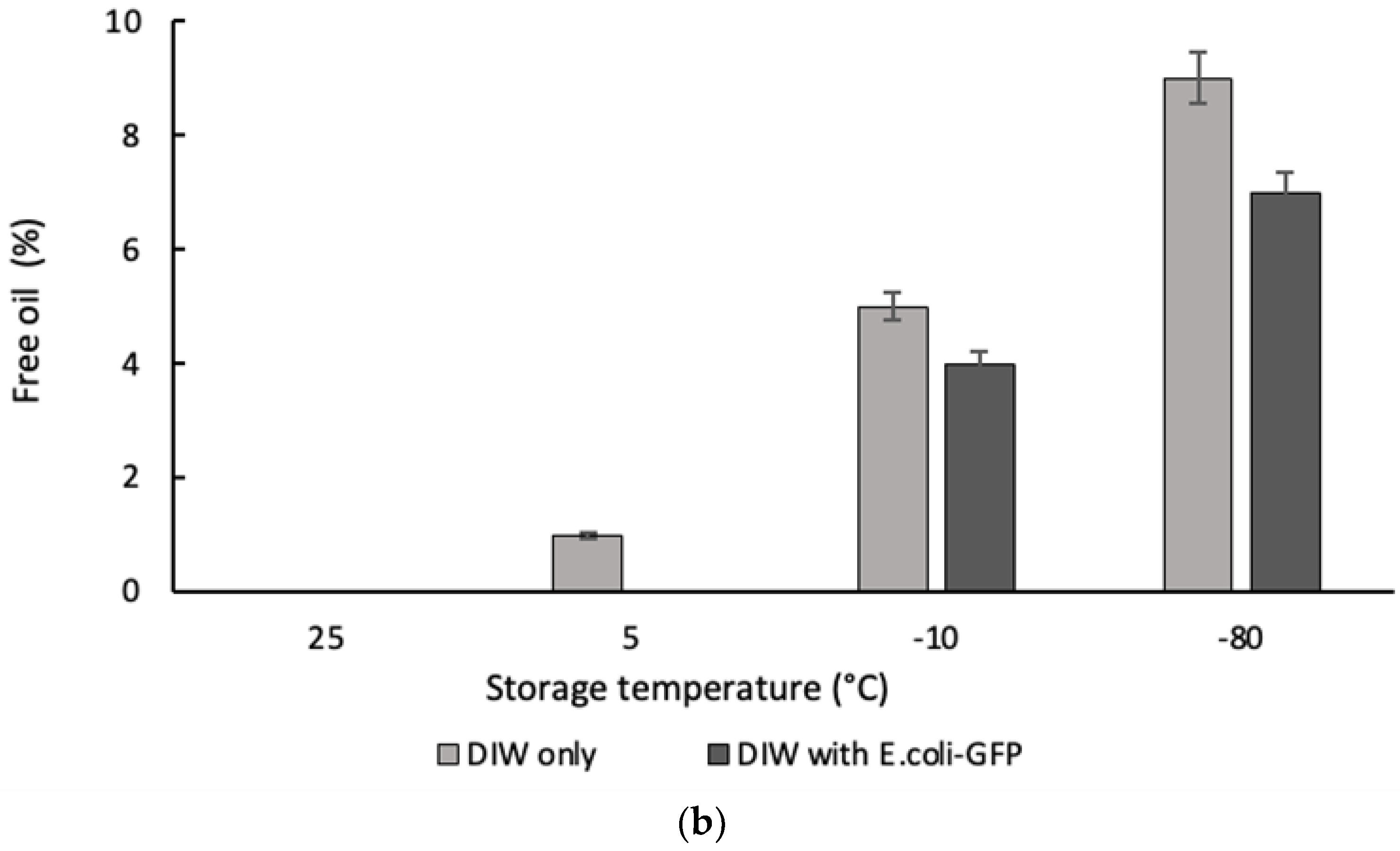

3.2 The Effect of Storage on Phase Separation of Emulsions

Droplet destabilization of W/O resulted in the presence of a free water layer due to droplet coalescence while the destabilization of W

1/O/W

2 droplet led to the presence of a free oil layer due to the external coalescence between the inner and outer aqueous phase (forming O/W emulsion) and coalescence between large oil droplets that resulted in the presence of an oil layer on top of the sample.

Figure 3 shows the percentage ratio of free water and oil measured after 24 hours of storage with respect to the total emulsion. From the results obtained it was determined that phase separation occurred for samples of both single and double emulsions kept in -20°C and -80°C with the highest amount of free water and free oil observed for samples kept at -80°C. Emulsion stability for samples stored at 25°C was maintained during the storage period as there were no observable free water or oil. However, a small percentage of free water and oil (approximately 2%) were observed for samples without

E. coli-GFP at 5°C and is mainly attributed to the closely packed water droplet during storage and the absence of

E. coli-GFP that helps in improving droplet stability. Overall comparison between samples with or without the presence of

E. coli-GFP shows that phase separation was minimized with the presence of

E. coli-GFP.

Droplet destabilization occurred for W/O emulsions kept at -20°C and -80°C due to partial coalescence of the droplet as the crystallization of the dispersed phase resulted in film rupture that connects neighbouring droplet leading to complete coalescence upon thawing (Boode, Walstra and de Groot-Mostert, 1993; Vanapalli, Palanuwech and Coupland, 2002). This eventually leads to bulk water separation that is minimized with the presence of E. coli-GFP in the inner W1 phase. During the consecutive crystallization of the oil phase, the dispersed ice crystals were forced to the still-liquid region of the oil phase and further reduction in temperature lead to the withdrawal of crystallized oil from this region. Combination of these processes leads to complete droplet coalescence and extensive aqueous phase separation from the emulsion during the thawing process (Degner et al., 2013, 2014). The partially crystallized oil phase of samples stored in -20°C prevented the complete withdrawal of the oil phase as some region within the emulsion may contain liquid oil thus minimizes extensive droplet coalescence.

The direct destabilization process of the double emulsion droplet that occurs immediately upon the thawing process leads to oil phase separation and the external coalescence of the inner W

1 phase and W

2 phase. As shown in

Figure 2 g, the movement of liquid oil through the cracks of the outer aqueous phase during the thawing process immediately separates the oil and aqueous phase forming bulk oil layer due to coalescence of bigger oil droplets while some oil droplets remain in a layer of O/W emulsion. The unfrozen W

1 phase will remain in the W

2 phase and eventually be infused into the W

2 phase as it melts (

Figure 2 h). This process leads to the complete release of the W

1 phase into the W

2 phase and extensive separation of the oil phase from the emulsion. Complete W

1/O/W

2 emulsion destabilization due to external coalescence during the thawing phase of the oil layer was also reported previously by Rojas and Papadopoulos (2007) whereby it leads to the complete release of the W

1 phase into the W

2 phase forming O/W emulsions.

The presence of crystallized surfactants and Pickering particles has been reported to improve droplet stability as it minimizes droplet coalescence during the thawing process by creating a protective layer that prevents droplet fusion (Ghosh and Coupland, 2008; Marefati et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2017). A similar stabilization effect may occur with the presence of E. coli-GFP on the interfacial layer. Under the freezing condition, E. coli-GFP undergo changes in membrane conformation and cell shrinkage (Souzu, 1980) making it easily embedded in the interfacial layer. Previous study reported the presence of E. coli-GFP in single W/O emulsions droplet helps in maintaining the stability of the droplet during five days of storage at 25°C whereby the presence of E. coli-GFP particularly dead cells helps in reducing interfacial tension due to its attachment on the interfacial layer (Mohd Isa et al., 2022). The bacterial affinity towards the interface is due to its hydrophobic nature as the dead E. coli-GFP cells exhibit higher affinity towards the oil phase as compared to live cells. BATH assay of E. coli-GFP with soybean oil reveals its affinity towards the oil phase (Figure S2) thus, may help in reducing the interfacial tension and creates a protective barrier that prevents extensive droplet coalescence during the thawing process. Moreover, the presence of bacteria in the W2 phase due to its release as the W1/O/W2 emulsion destabilizes may help in preventing coalescence between the oil droplet as reported previously by Firoozmand and Rousseau (2016) whereby the presence of bacterial cells in the aqueous phase of the O/W emulsions improves droplet stability due to the attachment of bacterial cells onto the oil droplet that creates a boundary layer thus protecting the droplet against coalescence and phase separation.

3.3. Thermal Properties of Emulsions by Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC).

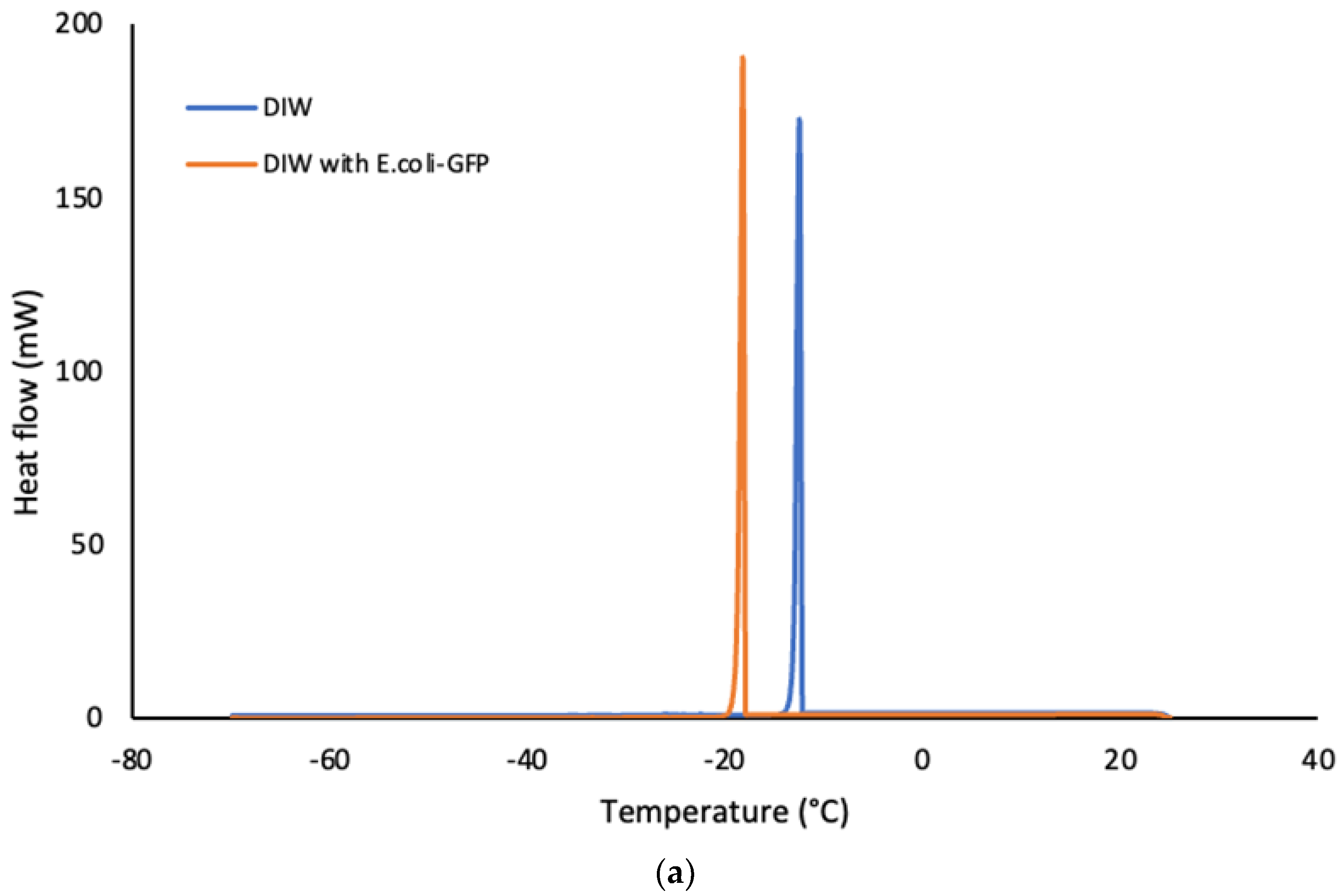

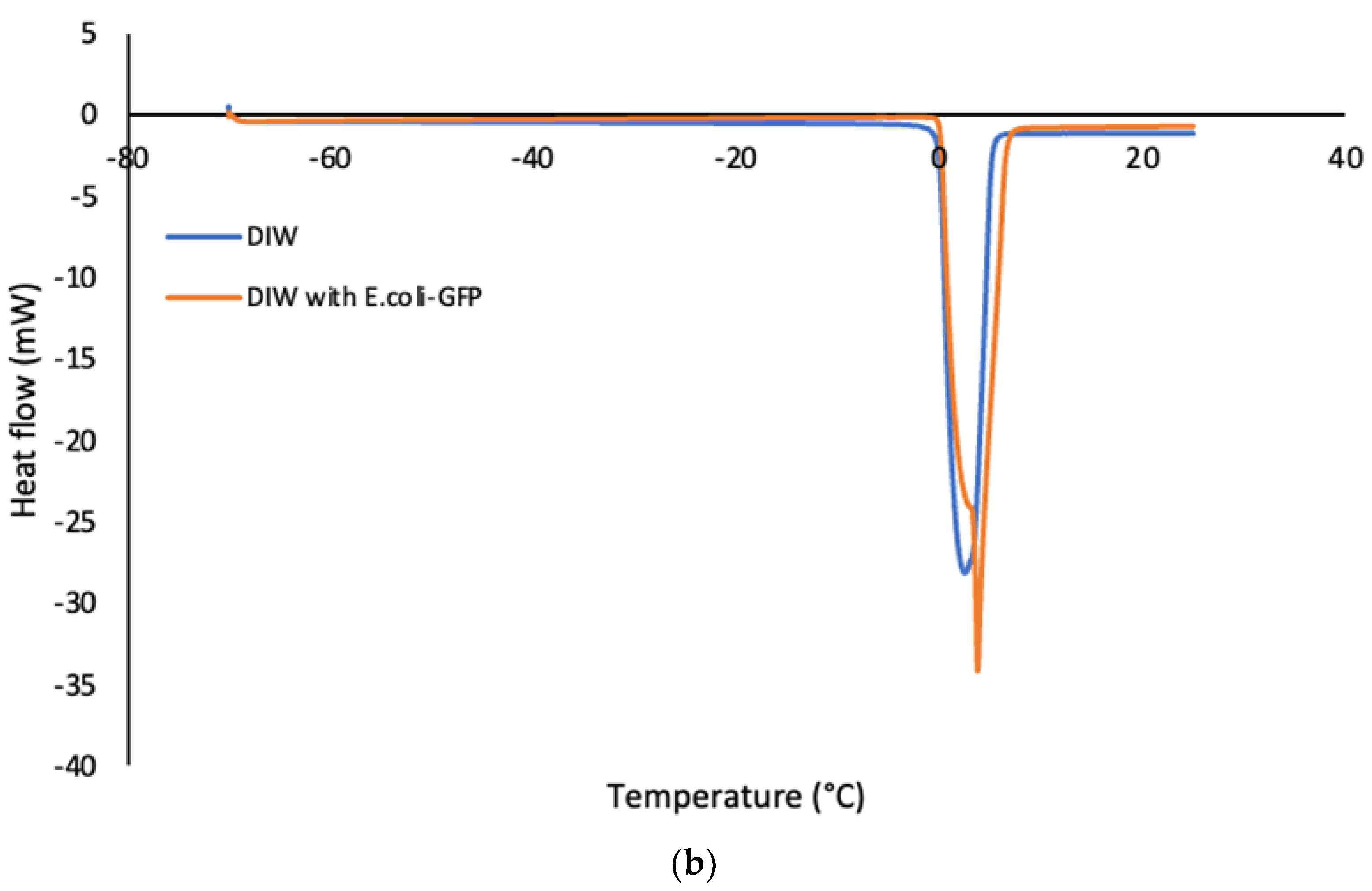

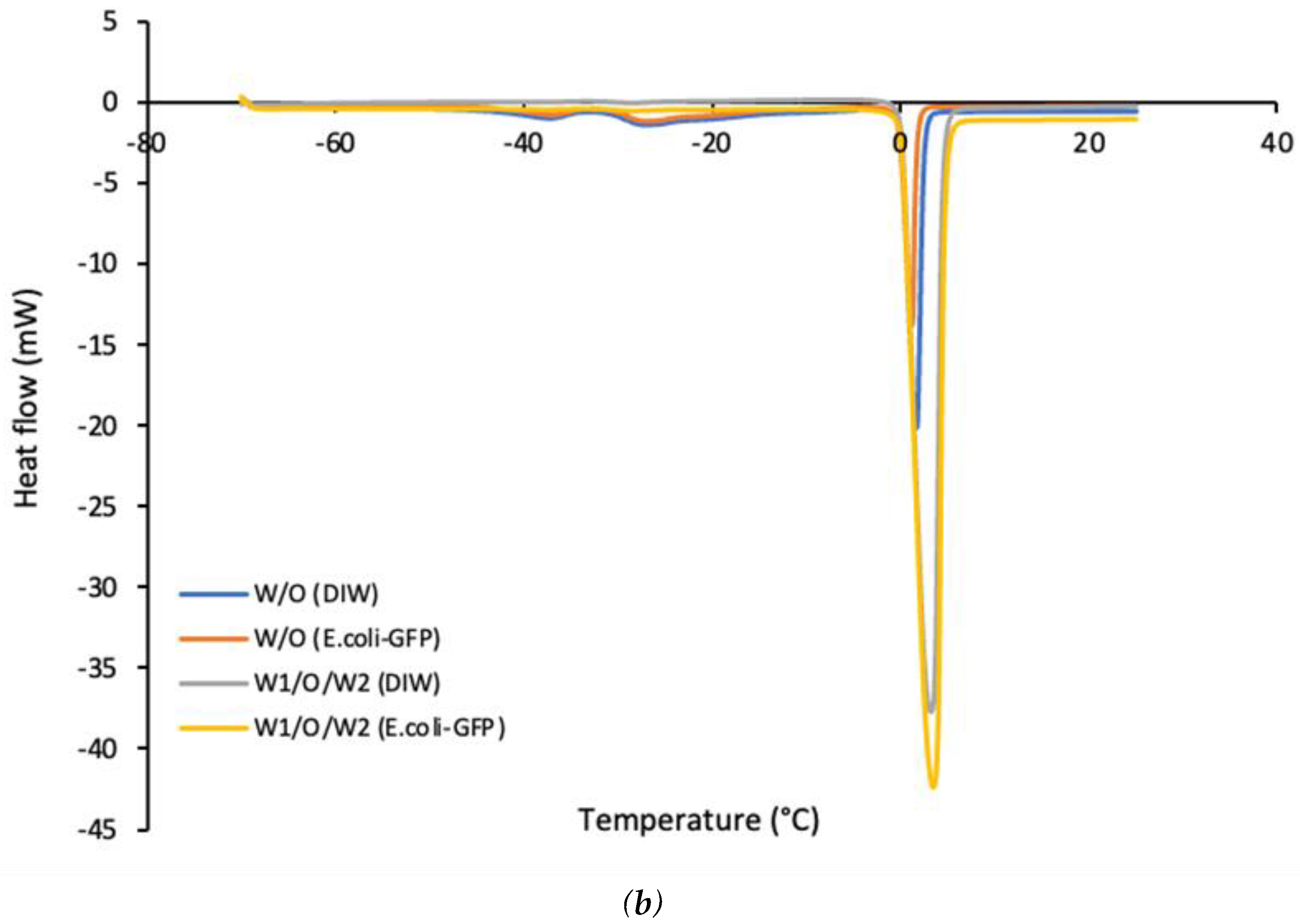

The thermal properties of the bulk aqueous solution (

Figure 4) were characterised as opposed to emulsified samples of single and double emulsions in soybean oil (

Figure 5). The crystallization temperature of the samples was determined from the onset temperature of the crystallization peaks in which the temperature was recorded at the beginning of the crystallite formation. The onset temperature was determined by using the Star e software (Mettler Toledo, Mettler Scientific Instruments, Germany). Referring to the crystallization peaks in

Figure 4 a, it was determined that the crystallization of

E. coli-GFP suspension in DIW occurred at a lower temperature as compared to pure DIW. The pure DIW crystallizes at -12°C and melted at 0°C which is around the same temperature as reported previously in several studies (Cramp

et al., 2004; Clausse

et al., 2005; Ghosh and Rousseau, 2009b). For the

E. coli-GFP suspension, the crystallization temperature was recorded at -17°C while the melting of the

E. coli-GFP suspension occurred around the same temperature as the pure DIW. The reduction in the crystallization temperature with the presence of

E. coli-GFP is due to the freezing point depression whereby the presence of

E. coli-GFP as solute tend to lower the freezing point.

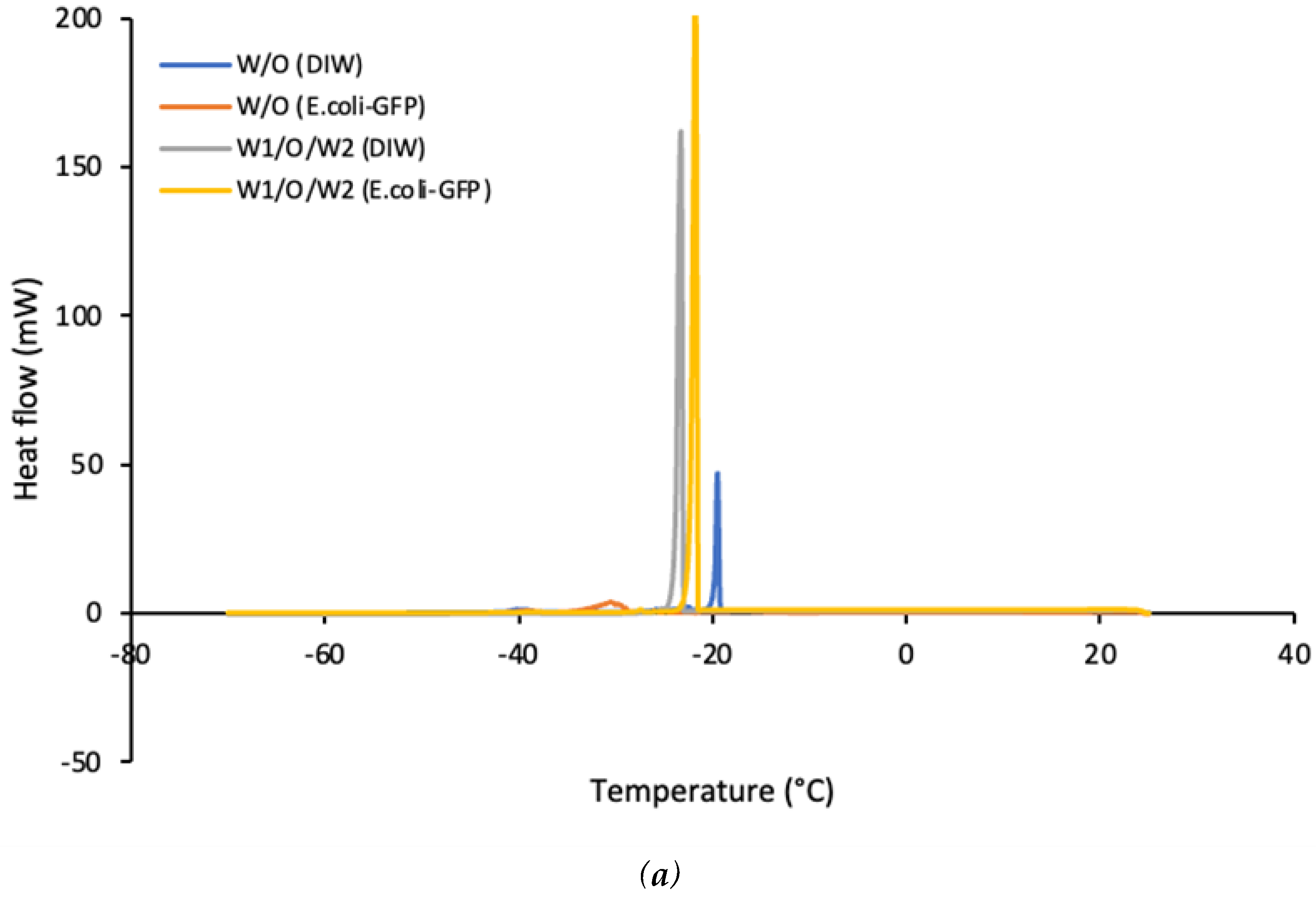

Figure 5 shows that the emulsified samples freeze at a much lower temperature compared to bulk solutions. A broader crystallization curve was observed for samples of W/O emulsions as compared to W

1/O/W

2 emulsions. This is mostly attributed to the presence of a large percentage of oil in the continuous phase as compared the aqueous phase for W/O emulsion. The presence of long chains of lipids together with a mixture of other molecules in soybean oil resulted in a broader crystallization temperature as opposed to pure water making it difficult to determine the exact freezing point of the soybean oil. It has been reported that pure soybean oil crystallizes at approximately -10°C to -20°C whereby it is most likely to solidify below these temperatures while soybean oil emulsions solidify at a much lower temperature than the pure oil (Harada and Yokomizo, 2000; Ishibashi, Hondoh and Ueno, 2016). In this study, the single W/O emulsion crystallizes at -20°C for samples without

E. coli-GFP while samples with

E. coli-GFP crystallize at -28°C. The melting point of both of the emulsions was around 0°C. The difference in crystallization temperature is mainly attributed to the destabilization of emulsions without

E. coli-GFP whereby the presence of free water due to phase separation increases the crystallization temperature of the samples. In addition, the similar melting point of the emulsions with that of bulk solutions also indicates the loss in emulsion stability due to an increase in the percentage of free water during the thawing process (Chen and He, 2003; Clausse

et al., 2005). It has been reported previously that the W/O emulsions solidify at a lower temperature than that of bulk water as it overcomes the free energy barrier due to homogeneous nucleation (Vanapalli, Palanuwech and Coupland, 2002). Water droplet in emulsions solidifies at a lower temperature than the temperature required to solidify bulk water (-20 °C) and are much lower than the equilibrium melting point of water of 0 °C (Lin

et al., 2007).

For double W

1/O/W

2 emulsions, a small difference in crystallization temperature was observed between samples with or without

E. coli-GFP as samples containing

E. coli-GFP crystallise at -21°C while samples without

E. coli-GFP crystallizes at -23°C. Only one peak was observed which gives the crystallization peak of the W2 phase as opposed to 2 peaks reported by Kovács

et al. (2005). The absence of the second peak indicates the loss of the inner W1 phase due to emulsion breakdown (Kovács

et al., 2005; Schuch, Köhler and Schuchmann, 2013). However, this may not be the case in this study as the inner W

1 droplet were intact during the freezing process as observed in

Figure 3 f and the loss of inner W

1 phase occurred during the thawing/melting process which explains the presence of only one peak for the melting curve with a melting temperature of approximately 0°C for all samples. Schuch, Köhler and Schuchmann (2013) also described that it is possible to distinguish between the inner W

1 phase and the outer W

2 phase from the cooling curves due to the presence of two peaks that resulted from the difference in crystallization temperature but it is impossible to distinguish between these two phases from the melting curves of the W

1/O/W

2. Another possible explanation for the presence of only one cooling curve is due to the highly monodispersed distribution of the droplet that was prepared by using the microfluidic method with single and large size of the W

1 inner core and a thin oil layer separating the W

1 phase from the W

2 phase. A combination of these factors may have caused the outer W

2 phase and the inner W

1 phase to crystallize simultaneously within the same temperature range. Schuch, Köhler and Schuchmann (2013) previously reported that the crystallization of emulsion droplet may depend on the size of the droplet. However, further studies are still required in order to understand the effect of droplet size distribution on the crystallization temperature of the multiple emulsion.

3.4 Bacterial Viability During Storage

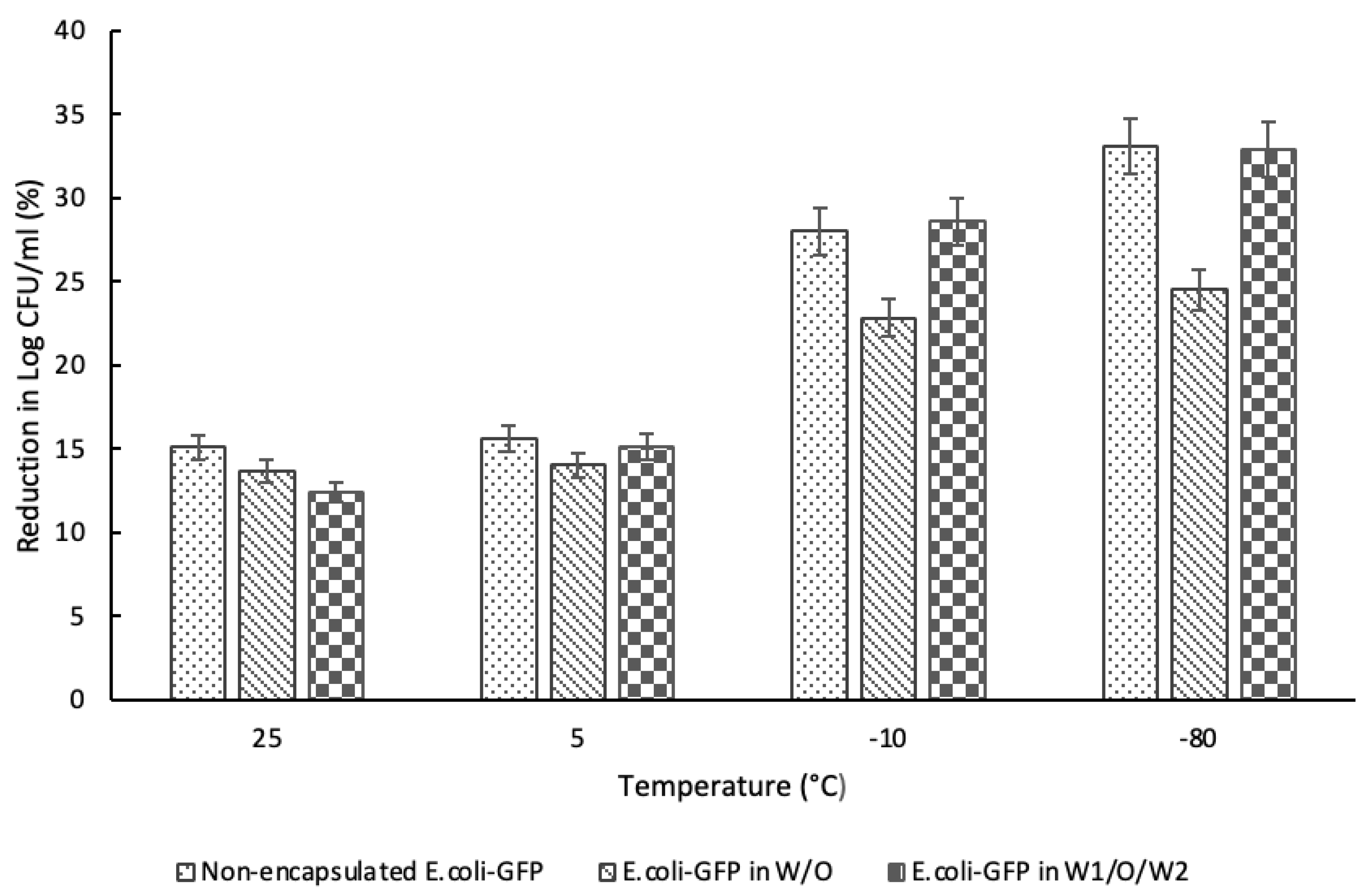

Referring to

Figure 6, a large reduction in

E. coli-GFP cell count was observed for samples kept at -20°C and -80°C as compared to samples kept in 25°C and 5°C whereby comparing between non-encapsulated samples, 1.2 log CFU/mL and 1.3 log CFU/mL reduction in viable cell count was observed for samples kept in 25°C and 5°C respectively while 2.3 log CFU/mL and 2.7 log CFU/mL of reduction was observed for samples kept in -20°C and -80°C respectively.

E. coli-GFP encapsulated in W/O droplet shows a smaller percentage of bacterial reduction as compared to samples encapsulated in W

1/O/W

2 droplet and control samples of free

E. coli-GFP cells in sterilised DIW.

It has been reported previously that freeze-thawing may cause detrimental effects on bacterial cells that lead to a reduction in bacterial viability (Souzu, 1980, 1989; Souzu, Sato and Kojima, 1989; Strocchi et al., 2006). Cell damage during the freeze-thaw process occurred due to various physico-chemical reactions (Simonin et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019). Some of the factors responsible for cell damage during storage at low temperatures are the nature of the cells (O’Brien et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019), whereby different bacterial species exhibit different resistance to cell damage depending on cell conformation. Furthermore, the use of cryoprotectant with various formulations (Wang et al., 2019) and the freeze-thawing conditions (Fonseca, Béal and Corrieu, 2002; Powell-Palm et al., 2018) of the samples may also affect the degree of cell damage during storage.

The effect of water crystallization is one of the most common factors responsible for cell damage (Souzu, 1980; Mazur, 2017; Powell-Palm

et al., 2018). The detrimental effect of water-crystallization on bacterial viability depended on the freezing rate whereby the decrease in bacterial viability is minimized at a low-freezing rate as compared to high-freezing rate. This is due to the cryoconcentration effect as the crystallization of the external medium resulted in cell dehydration thus preventing the lethal intracellular crystallization. The crystallization of the extracellular medium forces the cells to be concentrated in the unfrozen region of the medium whereby a continuous decrease in temperature caused the region to be increasingly concentrated. This leads to cell dehydration as the cells were exposed to a highly concentrated solution during the freezing process. Meanwhile, the rapid freezing of bacterial suspension resulted in extensive supercooling that crystallizes intracellular water as it is not able to flow out of the cells fast enough causing extensive cell damage (Simonin

et al., 2015). These indicate that the degree of cell damage during the freezing process depended on the availability of intra- and extracellular water. Referring to the DSC thermograms (

Figure 5), the broader crystallization temperature of the emulsion as compared to the bulk bacterial solution (

Figure 4) indicates that the encapsulation of bacteria in emulsion droplet promotes slow freezing of and thus minimizes cell damage during the freezing process. Encapsulation in W/O emulsion droplet shows a smaller reduction in cell count as compared to samples encapsulated in W

1/O/W

2 emulsion droplet and free cells in DIW due to the thick oil layer and the low water ratio that minimizes cells damage due to water crystallization.

The effect of encapsulation in improving bacterial viability during the freeze-thaw process has also been reported previously (Goderska and Czarnecki, 2008; Priya, Vijayalakshmi and Raichur, 2011; Dianawati, Mishra and Shah, 2013). The microencapsulation of Lactobacillus acidophilus in the self-assembled polyelectrolyte layers of chitosan and carboxymethyl cellulose has been reported to protect bacteria not only from the adverse effect of simulated GI tract but also during the freeze and freeze-drying processes (Priya, Vijayalakshmi and Raichur, 2011). Furthermore, the microencapsulation of Bifidobacterium longum in milk proteins and sugar alcohols aids in improving the protection effect of cryoprotectants such as glycerol resulting in better bacterial viability and function after the freeze and freeze-drying processes (Dianawati, Mishra and Shah, 2013). Moreover, the freezing of emulsion based products such as milk has also been reported to cause small changes in the viability of bacteria indicating the ability of the emulsion structure in protecting bacteria against extensive cell damage. A study done by Sánchez et al. (2003) shows that the freezing of goat milk at -20°C or even after extended storage at -80°C does not significantly affect the viability of E. coli as opposed to cow milk due to differences in milk composition. A similar result was also reported by Nurliyani, Suranindyah and Pretiwi (2015) whereby the frozen storage of Ettawah Crossed bred goats milk samples for 60 days does not cause changes in the total bacteria while changes in emulsion stability were observed after 30 days of storage. Therefore, the encapsulation of bacteria in emulsion droplet especially W/O may help in improving bacterial viability during the freezing process due to the protective effect of the emulsion structure as it reduces available water ratio and prevents the lethal crystallization effect of the water phase.

3.5. The Release of Bacteria from Double Emulsions

Although the storage of samples under freezing temperature leads to the unfavourable phase separation, the immediate destabilization of W

1/O/W

2 emulsion triggered by the thawing process may be beneficial for the controlled release of bacteria for various applications. A high encapsulation efficiency of approximately 99% was achieved by using microfluidic for bacteria encapsulation in W

1/O/W

2 that indicating successful encapsulation of bacteria prior to cold storage. The increase in cell counts of the W

2 phase, therefore, resulted from the release of bacteria from the W

1 phase due to emulsion destabilization process during storage as presented in

Table 2. Complete bacterial release into the W

2 phase was observed for samples kept in freezing temperatures of -20°C and -80°C with 5.10 log CFU/mL of viable bacteria were observed in the W

2 phase from the overall viable cell of 5.19 log CFU/mL (for samples kept at -20°C) and 4.90 log CFU/mL of viable bacteria were observed in the W

2 phase from the overall viable cell of 4.93 log CFU/mL (for samples kept at -80°C). Only 2.75 log CFU/mL of cells were released into the W

2 phase from the overall viable cell of 6.42 log CFU/mL for samples kept in 25°C and 2.77 log CFU/mL of cells were released from the overall viable cells of 6.18 log CFU/mL at 5°C. The release of bacteria for samples kept in 25°C and 5°C was mainly attributed to the rupture of the thin film that separates the W

1 phase from the W

2 phase, induced by the change in the osmotic balance of the droplet due to the production of bacterial by-products during the storage period. On the other hand, the complete destabilization of the W

1/O/W

2 emulsion droplet that was kept in frozen temperature is due to the freeze-thawing process that leads to phase separation. This process resulted in the complete release of the encapsulated bacteria as the emulsion destabilizes into a layer of the bulk oil phase (top), O/W emulsion (middle) and the aqueous phase (bottom) containing the released bacteria.

As the inner W

1 phase remains intact during the freezing process (

Figure 2 f), the frozen W

1/O/W

2 may serve as an alternative for bacterial microencapsulation whereby the controlled release of the encapsulated bacteria at the desired time can be achieved by simply thawing the frozen emulsion samples causing immediate and complete release of the bacteria into the W

2 phase. Emulsion destabilization induced by the freeze-thawing process has been used extensively in various applications such as in emulsion liquid membrane (ELM) processing (Hirai, Hodono and Komasawa, 2000; Hirai

et al., 2002) and waste emulsion treatment such as in oil sludge demulsification (He and Chen, 2002; Chen and He, 2003). Its application in pharmaceuticals have also been discussed previously by Bernal-Chávez

et al. (2023). Moreover, a study by Rojas and Papadopoulos (2007) also revealed the potential application of W

1/O/W

2 emulsion droplet for the controlled release of encapsulated materials that is triggered by the thawing of the oil phase. Similar to the results obtained in this study, the internal coalescence of the inner W

1 phase and the external coalescence of the outer W

2 phase were not observed during the freezing stage but occurred extensively during the thawing of the oil phase which leads to complete release of the encapsulated material (

Figure 7). This study was then followed by a study on its potential application for the controlled release of protein from the bulk emulsion systems (Rojas

et al., 2008). As expected, similar results were also obtained in the bulk emulsion systems whereby the stability of the droplet was maintained during the freezing process while the thawing of the oil phase leads to an instant release of the encapsulated protein.