Submitted:

24 September 2024

Posted:

25 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

| Major Oxides | Na2O | MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | P2O5 | K2O | CaO | TiO2 | MnO | Fe2O3 | LOI | TOTAL | Sc | V | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Cd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp-01 | 0.3 | 22.8 | 6.9 | 37.3 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 4.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 5 | 11.3 | 99.6 | 20 | 72 | 18 | 1001 | 14 | 35 | 9.9 | 10 | 102 | 7.3 | 19 | 2.4 | 5 | 0.1 |

| Sp -03 | 0.1 | 38.8 | 0.5 | 40.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 7.4 | 11.8 | 100.4 | 4 | 12 | 87 | 965 | 3 | 26 | 0.9 | 10 | 10 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 | 5 | 2 |

| Sp -04 | 0.1 | 34.9 | 0.6 | 35.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 4.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 7.2 | 11.4 | 100.4 | 3 | 12 | 91 | 972 | 19 | 446 | 1.1 | 10 | 32 | 0.4 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 5 | 2 |

| Sp -06 | 0.1 | 38.2 | 0.3 | 41.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 6.6 | 11.6 | 100.6 | 6 | 16 | 75 | 1545 | 3 | 42 | 1.7 | 10 | 10 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.6 |

| Sp -08 | 0.1 | 37.7 | 0.8 | 41.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.6 | 11.3 | 100.2 | 8 | 27 | 73 | 1819 | 4 | 26 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 0.2 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 5 | 1.1 |

| Sp -09 | 0.1 | 37.2 | 0.8 | 42.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 6.6 | 9.1 | 100.1 | 5 | 15 | 54 | 1197 | 4 | 32 | 2.2 | 10 | 10 | 14.4 | 2.6 | 1 | 5 | 0.8 |

| Sp -10 | 0.1 | 37.3 | 2.6 | 38.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 9 | 8.0 | 99.9 | 9 | 24 | 81 | 727 | 5 | 35 | 1.1 | 10 | 10 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 5 | 1.6 |

| Sp -11 | 0.1 | 33.5 | 1.9 | 37.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 4.23 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 8.3 | 1.6 | 99.8 | 7 | 33 | 96 | 1184 | 15 | 34 | 1 | 10 | 29 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 0.1 | 5 | 1.1 |

| Sp -12 | 0.1 | 36.7 | 0.5 | 37.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.7 | 3.4 | 99.8 | 20 | 44 | 82 | 1757 | 24 | 44 | 0.8 | 10 | 140 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.8 |

| Sp -14 | 0.1 | 38.5 | 0.6 | 39.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 74 | 1.3 | 99.9 | 6 | 36 | 74 | 1503 | 17 | 33 | 1.1 | 10 | 20 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.1 | 5 | 1.1 |

| Sp -15 | 0.1 | 38.4 | 0.8 | 41.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 10 | 1.3 | 99.9 | 7 | 19 | 96 | 2033 | 19 | 34 | 0.8 | 10 | 10 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 0.1 | 5 | 1.1 |

| Sp -16 | 0.1 | 37.6 | 0.8 | 40 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 7.9 | 1.9 | 99.9 | 5 | 31 | 74 | 1513 | 12 | 31 | 1.5 | 10 | 10 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 5 | 1.3 |

| Sp -17 | 0.1 | 37.9 | 0.6 | 40.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 10.6 | 1.4 | 99.9 | 12 | 28 | 75 | 1739 | 13 | 29 | 0.7 | 10 | 10 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.7 |

| Sp -18 | 0.1 | 36.2 | 0.8 | 38.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 7.9 | 1.2 | 99.8 | 8 | 43 | 89 | 1019 | 113 | 47 | 0.9 | 10 | 10 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 5 | 1.5 |

| Sp -21 | 0.1 | 38.1 | 0.4 | 37.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 10.0 | 1.7 | 99.9 | 9 | 26 | 80 | 1740 | 7 | 41 | 0.7 | 10 | 10 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.7 |

| Sp -23 | 0.1 | 41.1 | 0.7 | 43.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 9.67 | 1.7 | 99.9 | 0 | 15 | 73 | 1687 | 11 | 36 | 0.9 | 10 | 10 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 5 | 1.1 |

| Sp -24 | 0.1 | 42.1 | 0.6 | 41.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 3.42 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 7.1 | 1.4 | 99.8 | 0 | 27 | 91 | 1860 | 23 | 41 | 0.9 | 10 | 10 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.9 |

| Sp -25 | 0.1 | 36.7 | 3.3 | 37.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 5.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 7.8 | 2.0 | 99.8 | 0 | 37 | 79 | 1175 | 4 | 28 | 2.9 | 10 | 75.4 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.8 |

| Sp -27 | 0.1 | 33.8 | 3.3 | 40.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 9.1 | 1.4 | 99.8 | 0 | 34 | 68 | 1323 | 20 | 37 | 2.1 | 18 | 10 | 2.8 | 4.6 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.7 |

| Trace Elements | Ba | Ti | Cr | Sn | Mn | Cs | Ta |

| Sp-01 | 33 | 22 | 226 | 10 | 814 | 1,1 | 0,2 |

| Sp -03 | 49 | 32 | 233 | 11 | 803 | 0,1 | 0,1 |

| Sp -04 | <10 | 32 | 432 | 10 | 619 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

| Sp -06 | <10 | 36 | 625 | 10 | 934 | 1,2 | <0.1 |

| Sp -08 | <10 | 32 | 112 | 11 | 722 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

| Sp -09 | <10 | 30 | 201 | <10 | 274 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

| Sp -10 | <10 | 66 | 772 | <10 | 565 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

| Sp -11 | <10 | 33 | 381 | <10 | 415 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

| Sp -12 | <10 | 34 | 206 | <10 | 324 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

| Sp -14 | <10 | 55 | 189 | <10 | 217 | 0,1 | 0,1 |

| Sp -15 | <10 | 58 | 204 | <10 | 219 | 0,1 | 0,1 |

| Sp -16 | <10 | 37 | 311 | <10 | 812 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

| Sp -17 | <10 | 44 | 197 | <10 | 613 | 0,1 | 0,1 |

| Sp -18 | <10 | 31 | 312 | <10 | 913 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

| Sp -21 | <10 | 52 | 423 | <10 | 577 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

| Sp -23 | <10 | 35 | 178 | <10 | 311 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

| Sp -24 | <10 | 37 | 120 | 10 | 293 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

| Sp -25 | <10 | 33 | 344 | <10 | 435 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

| Sp -27 | <10 | 34 | 221 | <10 | 209 | 0,1 | <0.1 |

3. Results

3.1. Geochemistry

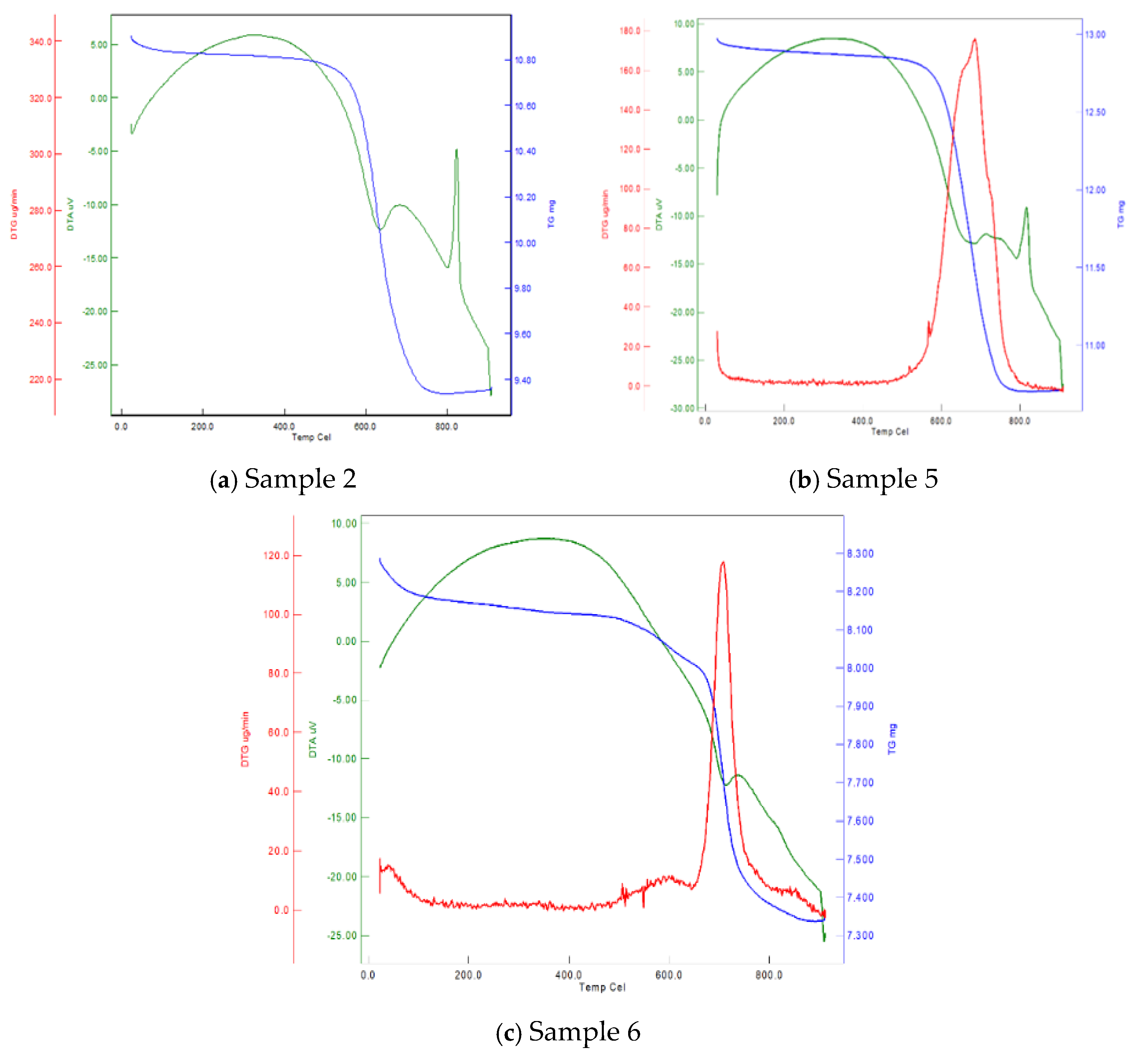

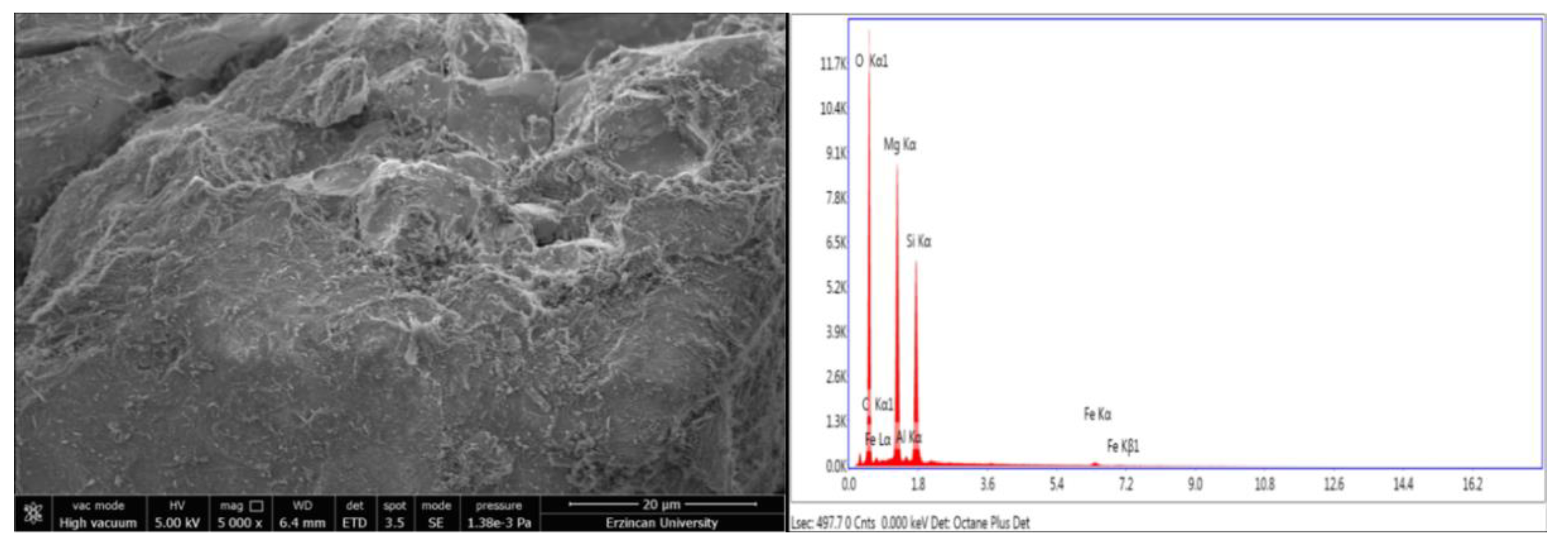

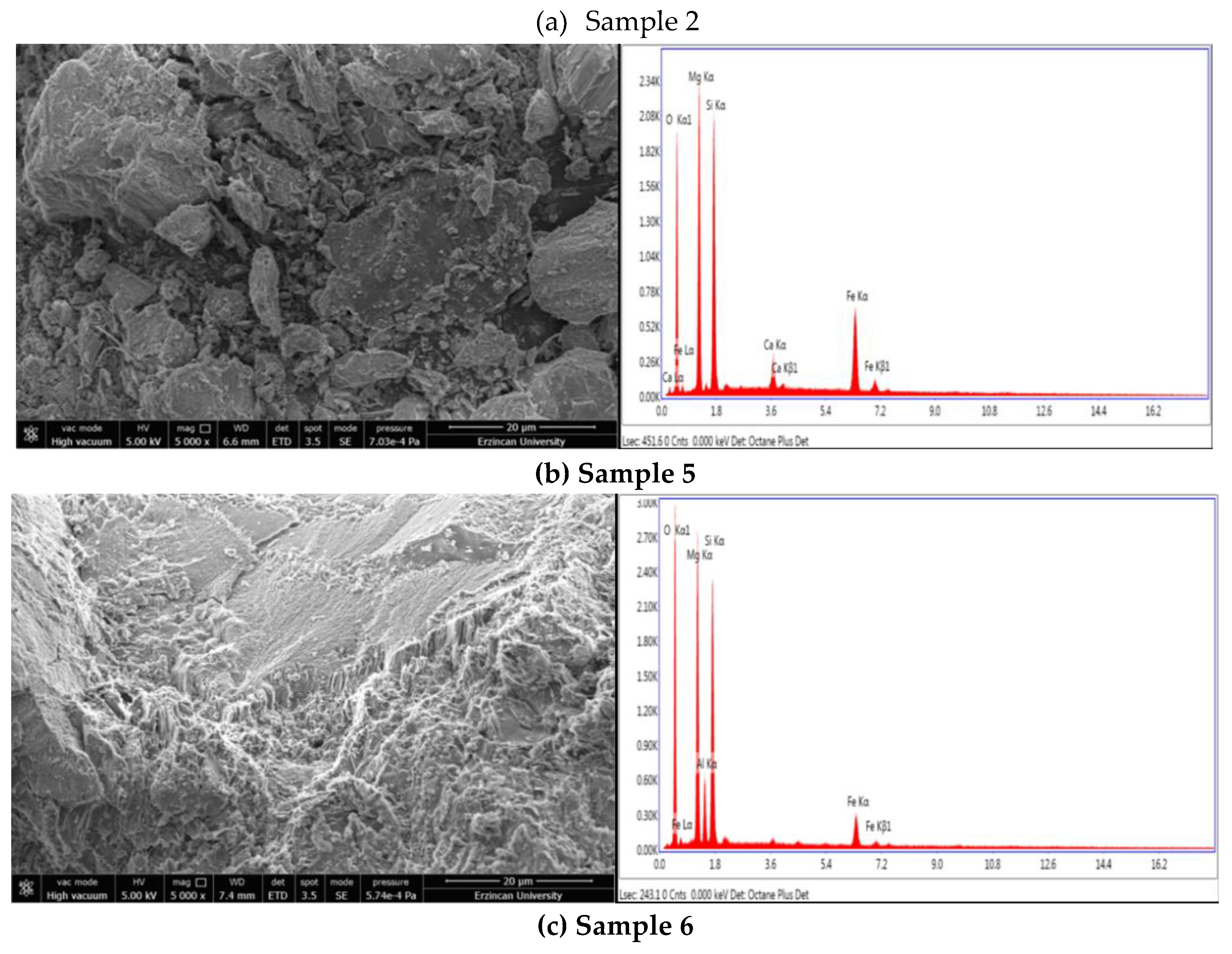

3.2. Thermophysical Properties (SEM, TG, DTA)

5. Conclusions

5. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kılıç, A.D.; İnceöz, M. Mineralogical, geochemical and isotopic effect of silica in ultramaphic systems, eastern Anatolian Turkey. Geochemistry International 2015, 53, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilek, Y.; Flower, M.F.J. ; Arc-trench rollback and forearc accretion: 2. Model template for Albania, Cyprus, and Oman. In: Dilek, Y., Robinson, P.T. (Eds.), Ophiolites in Earth History, vol. 218. Geological Society of London, 2003,43–68. Special Publication.

- Rakovan, J. Rocks Minerals. 2011; 98, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, B.W.; Hattori, K.; Baronnet, A. Elements. 2013; 9, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Wicks, F. J.; Whittaker E. J., W. A reappraisal of the structures of the serpentine minerals. The Canadian Mineralogist, 1975, 13 (3): 227–243.

- Evans, B.W. Lizardite versus antigorite serpentinite: magnetite, hydrogen, and life. Geology 2010, 38, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A. , Acid Leaching Studies of Chrysotile Asbestos from Mines In The Coalinga Region Of California And From Quebec And British Columbia. Am. occup. Hyg. 1997, 41/3,249–268. [CrossRef]

- Klein, F.; Bach, W.; McCollom, T.M. Compositional controls on hydrogen generation during serpentinization of ultramafic rocks. Lithos 2013, 178, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hanley, D. S.; Wicks, F. J. Conditions of formations of lizardite, chrysotile and antigorite, Cassiar, British Columbia, Can. Mineral. 1995, 33, 753 – 773.

- Sanna, A.; Wang, X.; Lacinska, A.; Styles, M.; Paulson, T.; Maroto-Valer, M. Enhancing Mg extraction from lizardite-rich serpentine for CO2 mineral sequestration. Minerals Engineering 2013, 49, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, W. An experimental investigation of the system MgO-SiO2-H2O-CO2. American Journal of Science 1969, 267, 1083–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, J.B. Serpentinisation a review. Lithos 1976, 9, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Früh-Green, G.L.; Connolly, J.A.D.; Plas, A. Serpentinization of oceanic peridotites: Implications for geochemical cycles and biological activity. In: The Subseafloor Biosphere at Mid-Ocean Ridges, Geophys. Am Geophys Union Monograph Ser. 2004, 144,119–136. [CrossRef]

- Page, N.J. Chemical differences among the serpentine Bpolymorphs. Am Mineral 1968, 53, 201–201. [Google Scholar]

- Jones L., C. ; Rosenbauer. R.; Goldsmith, J.I. Carbonate control of H2 and CH4 production in serpentinization systems at elevated P-T’s. Geophys Res Lett, 2010, 37,1–6. [CrossRef]

- Andréani, M.; Baronnet, A.; Boullier, A.M.; Gratier, J.P. A microstructural study of a B crack-seal type serpentine vein using SEM and TEM techniques. Eur J Mineral 2004, 16, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, L.; Jr Le Marche,V. C.; Himmelberg,G.R. Geochemical evidence of present day serpentinization. Science 1967, 156, 830–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleep, N. H.; Bird, D. K,.; Pope, E. C. Serpentinite and the dawn of life. Philos Trans Royal Soc London B 2011, 366, 2857–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, I.; O'Neil, J.R. The relationship between fluids in some fresh Alpine-type ultramafics and possible modern serpentinization, Westem United States. Geol. Soc. Amer. Bull. 2019, 80, 1947–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, P.; Trommsdorff, V. Serpentine Stability to Mantle Depths and Subduction-Related Magmatism, 1995,.268, 5212, 858-61. [CrossRef]

- Rouméjon, S.; Cannat, M. Serpentinization of mantle-derived peridotites at mid-ocean ridges: Mesh texture development in the context of tectonic exhumation. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst 2019, 15, 2354–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittenden, E.T.; Stanton, D.J.; Watson, J.; Dodson, K.J. Serpentine and dunite as magnesium fertilisers. New Zealand. J Agric Res 1967, 10(1): 160-171. [CrossRef]

- Mcnaught, K.J.; Dorofaeff, F.D.; Karlovsky, J. Effect of magnesium fertilisers and season on levels of inorganic nutrients in a pasture on Hamilton clay loam. New Zealand. J Agric Res 1968, 11, 3, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błońska, E.; Januszek, K.; Małek, S.; Wanıc, T. Effects of serpentinite fertilizer on the chemical properties and enzyme activity of young spruce soils. Int Agrophys 2016, 30, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, A.B.; Loureıro, F.; Sampaıo, J.A.; Castılhos, Z.C.; Bezerra, M.S. Capítulo 4. Rochas, minerais e rotas tecnológicas para a produção de fertilizantes alternativos. In: Centro de Tecnologia Minerals 2010., 380.

- Carmignano, O.; Vieira, S.S.; Paulo, B.; Bertoli, A.; Lago, R. M. Serpentinites: Mineral Structure, Properties and Technological Applications. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2019, 00, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaskowskı, A.E.; Bergmann, M.; Sılveıra, C.A.P.; Garnıer, J.; Camargo, M.A.; Cavalcante, O.A. Potencial das rochas das pilhas de rejeitos da mineração Ferbasa-Cia de Ferroligas da Bahia como corretivos e remineralizadores de solo. p. 121-127. In: Anais do III Congresso Brasileiro de Rochagem, 8 a 11 de novembro de 2016 / Adilson Luis Bamberg... et. al. (Eds). Pelotas: Embrapa Clima Temperado; Brasília: Embrapa Cerrados; Assis: Triunfal Gráfica e Editora 2016, 455.

- Moody, J.B. Serpentinization: Areview. Lithos 1976, 9(2), 25–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, J.A. Chrysotile asbestos cement and the Grenfell Tower fire. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 2018, 361, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Kaas, A.; Kinnunen, P.; Carvelli, V.; Monticelli, C.; Yliniemi, J.; Illikainen, M. Fiber reinforced alkali-activated stone wool composites fabricated by hot-pressing technique. Mater. Des. 2020, 186, 108–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozeva, N. G. Carbon and mineral transformations in seafloor serpentinization systems. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 2018.

- Kakooei, H.; Marioryad, H. Evaluation of exposure to the airborne asbestos in an automobile brake and clutch manufacturing industry in Iran. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 56(2), 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, M.; Uehara, S. What is asbestos? Rock Miner. Sci. 2006, 35, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znamenáčková, I.; Dolinská, S.; Lovás, M.; Hredzák, S.; Matik, M.; Tomčová, J.; Čablík, V. Application of microwave energy at treatment of asbestos cement (eternit). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2016; 052023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwaszko, J. Making asbestos-cement products safe using heat treatment. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2019, 10, e00221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, G.; Horner, J.A. Fibrous ceramic aluminum silicate as an alternative to asbestos liners. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1980, 44(1), 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrajano, T. A. Geochemistry of reduced gas related to serpentinization of the Zambales ophiolite, Philippines. Appl. Geochemistry 1990, 5, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollom, T. M. Geochemical constraints on primary productivity in submarine hydrothermal vent plumes. Deep-Sea Res. Letter, 2000; 47, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmingnano, O. Employment of serpentinite rock in architecture. Journal of Material Science & Engineering 2023, 301, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barne, I.; O'Neil, J. R. The relationship between fluids in some fresh alpine-type ultramafics and possible modern serpentinization, western United States. Geological Society of America Bulletin 1969, 80(10), 1947–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, P. B.; Coleman, R. G.; Mumpton, F.A. ; Evans,B.W.Brucite in alpine serpentinites. Am. Mineralogist, 1966; 51, 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kilic, A.D.; Konakcı, N.; Sasmaz, A. Garnet Geochemistry of Pertek Skarns (Tunceli, Turkey) and U-Pb Age Findings. Minerals, 2024; 14, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Me´vel, C. Serpentinization of abyssal peridotites at mid-ocean ridges, C.R. Geosci. 2003, 335, 825 – 852. [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, A. Resour. Policy 2018, 59, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan, Y. Z. Guleman ofiyolitinde metamorfizma izleri, TJK symposium (ın Turkish) 1989, 11, 29-32.

- Kılıç, A.D.; Yıldırım, Ö. Redox Reactions in Antigorite Serpentinites. 3. International Conference on Innovative Academic studies 2023, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps, F.; Godard, M.; Guillot, S.; Hattori, K. Geochemistry of subduction zone serpentinites: A review. Lithos 2013, 178, 96–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yada, K.; Iishi, K. Serpentine minerals hydrothermally synthesized and their microstructures. J. Crystal Growth, 1974; 24/25, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y. Bulk-rock major and trace element compositions of abyssal peridotites: Implications for mantle melting, melt extraction and post-melting processes beneath mid-ocean ridges. Journal of Petrology 2004, 45, 2423–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, M.C.; Taylor, H.F.W. The dehydration of chrysotile in air and under hydrothermal conditions. Mineral. Mag. 1963, 33, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viti, C. Serpentine minerals discrimination by thermal analysis. Am. Mineral. 2010, 95, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, J.C.; Shanks, W.C. Stable isotope compositions of serpentine seamounts in the Mariana forearc: Serpentinization processes, fluid sources and sulphur metasomatism. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2006, 242, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.F. The composition of the Earth. Chemical Geology 1989, 120, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Surour, A.A. Chemistry of serpentine “polymorphs” in the Pan-African serpentinites from the Eastern Desert of Egypt, with an emphasis on the effect of superimposed thermal metamorphism. Miner Petrol 2017, 111, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, F.; Andreani, M.; Boullier, A.M.; Labaume, P. Crack-seal patterns: Records of uncorrelated stress release variations in crustal rocks, in Deformation Mechanisms, Rheology and Tectonics: From Minerals to the Lithosphere, edited by D. Gapais et al. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2005; 243, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, K.H.; Wallis, S.; Enami, T. ; Mizukami,T. Subduction of mantle wedge peridotites: evidence from the Higashi-akaishi ultramafic body in the Sanbagawa metamorphic belt. Island Arc, 2010; 19, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellebrand, E.; Snow, J.E.; Dick, H.J.B. ; Hofmann,A.E. Coupled major and trace elements as indicators of the extent of melting in mid-ocean-ridge peridotites. Nature, 2001; 410, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.F. The composition of the Earth. Chemical Geology 1989, 120, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y. Bulk-rock major and trace element compositions of abyssal peridotites: Implications for mantle melting, melt extraction and post-melting processes beneath mid-ocean ridges. Journal of Petrology 2004, 45, 2423–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, P.B.; Hirth, G.; Shimizu, N.; Spiegelman, M. , Dick, H.J.B. A review of melt migration processes in the adiabatically upwelling mantle beneath oceanic spreading ridges. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London A, 1997; 355, 283–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, H.; Sun, W.; Deng, J.; Robert, E.; Zartmanb, E.; Guo, J.; Bao, Z.; Zong, J. Boron, arsenic and antimony recycling in subduction zones: New insights from interactions between forearc serpentinites and CO2-rich fluids at the slab-mantle interface. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2021, 298, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashiro, A.; Shido, F.; Ewing, M. Composition and origin of serpentinites from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge near 24 and 30°N. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1969, 23, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, C.J.; Escartín, J.; Banks, G. J.; Irving, D.H.B.; Lilly, R.M.; Niu, Y.L.; Banerji, D.; McCaig, A.; Allerton, S.; Smith, D.K. Direct geological evidence for oceanic detachment faulting: the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, 15°45′N. Geology 2002, 30, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J. H. Simple analytic model for subduction zone thermal structure. Geophysical Journal International 1999, 139(3), 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Cassetta, M.; Giarola, M.; Zanatta, M.; Le Guen, M.; Soraru, G.D.; Mariotto, G. Thermal Annealing and Phase Transformation of Serpentine-Like Garnierite. Minerals 2021, 11(2), 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi, C. E.; Gürel S., B. , Kılınç, D.; Emrullahoglu,Ö.F. Production of forsterite from serpentine–Effects of magnesium chloride hexahydrate addition. Advanced Powder Technology 2015, 26(3), 947-953. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q. Zhang, Y.;Dong, Z. Low-wave-velocity and high-electrical-conductivity layer of serpentine: a compilation. Pure and Applied Geophysics 2019, 176, 4941–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantini, R.; Sisti, M.; Arletti, R.; Malferrari, D.; Gamberini, M.C.; Zapparoli, M.; Gualtieri, A.F. Identification and quantification protocol of hazardous-metal bearing minerals: Ni in serpentinite rocks from Valmalenco (Sondrio, Central Alps, Northern Italy). Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 134–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschamps, F. ; Godard, M; Guillot, S; HattoriK. Geochemistry of subduction zoneserpentinites: A review. Lithos 2013, 178:96–127. [CrossRef]

- Savov, I.P.; Ryan, J.G.; D'Antonio, M.; Kelley, K.; Mattie, P. Geochemistry of serpentinizedperidotites from the Mariana ForearcConical Seamount, ODP Leg 125:İmplications for the elemental recycling atsubduction zones. Geochemistry,Geophysics, Geosystem, 2005a; 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | ∑REE | ∑LREE | ∑HREE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp-01 | 0.90 | 0.48 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 3.29 | 2.39 | 0.90 |

| Sp -03 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.38 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 2.55 | 1.64 | 0.91 |

| Sp -04 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.10 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 2.74 | 1.84 | 0.90 |

| Sp -06 | 0.88 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 3.10 | 2.15 | 0.95 |

| Sp -08 | 0.66 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.42 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 3.05 | 2.17 | 0.88 |

| Sp -09 | 0.92 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 3.42 | 2.67 | 0.94 |

| Sp -10 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.36 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 2.67 | 1.70 | 0.97 |

| Sp -11 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 2.51 | 1.61 | 0.90 |

| Sp -12 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.10 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 2.66 | 1.79 | 0.87 |

| Sp -14 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 2.53 | 1.59 | 0.94 |

| Sp -15 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.45 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 2.59 | 1.72 | 0.87 |

| Sp -16 | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 2.69 | 1.74 | 0.95 |

| Sp -17 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.43 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 2.78 | 1.82 | 0.96 |

| Sp -18 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.44 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 2.53 | 1.58 | 0.95 |

| Sp -21 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 2.52 | 1.58 | 0.94 |

| Sp -23 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.38 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 2.66 | 1.70 | 0.96 |

| Sp -24 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.13 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 2.53 | 1.63 | 0.90 |

| Sp -25 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 2.74 | 1.76 | 0.98 |

| Sp -27 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 2.58 | 1.65 | 0.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).