Submitted:

21 September 2024

Posted:

24 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fieldwork Methods

2.2. Image Treatment and Analysis

2.3. Environmental Measures

2.4. Physical Health Measures and Welfare Scoring System

2.4.1. Body Condition Scoring

2.4.2. Skin Condition Scoring

2.4.3. Injury and Scar Condition Scoring

2.4.4. Parasite and Epibiont Condition Scoring

| Parasite and epibiont categories |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Orange film/diatoms (OFD) |

Orange film covering parts of the body to different extent (Figure 7.A) [139,140]. |

|

Lamprey bite and skid marks (LBM) |

Circular marks with a pale centre and darker edges, sometimes raised. Skidding marks are often observed with parallel scratches (Figure 7.B) [130,131]. |

|

Cookiecutter wounds/ scars (CCW) |

Oval-shaped crater-like wounds. Colour will depend on the healing stage, from pink to red in a fresh wound to whitish in a healing phase, to a depressed scar with normal pigmentation once healed (Figure 7.C) [130,141]. |

|

Whale lice (Louse) (WL) |

Small crustaceans of the Cyamid family found on body parts with folds (e.g., the ventral grooves or around blowholes). Infestations can also be observed on open wounds or immune-compromised individuals (Figure 7.D) [99,142]. |

|

Fluke barnacle load (FBL) |

Crustaceans from the family Coronulidae typically attached to appendages like pectoral fins or fluke (Figure 7.E and F) [104,143]. |

2.4.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Anthropogenic Injuries and Body Condition

3.2. Parasite/Epibiont Loads and Skin Health Condition

3.3. Environmental Parameters

3.4. Overall Welfare State

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Environmental Degradation on Epidermal State

4.2. Anthropogenic Activities and Stress Response

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abadi, S.H.; Tolstoy, M.; Wilcock, W.S.D. Estimating the Location of Baleen Whale Calls Using Dual Streamers to Support Mitigation Procedures in Seismic Reflection Surveys. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0171115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantine, R.; Johnson, M.; Riekkola, L.; Jervis, S.; Kozmian-Ledward, L.; Dennis, T.; Torres, L.G.; Aguilar de Soto, N. Mitigation of Vessel-Strike Mortality of Endangered Bryde’s Whales in the Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 186, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigada, S.; Donovan, G.P.; Druon, J.-N.; Lauriano, G.; Pierantonio, N.; Pirotta, E.; Zanardelli, M.; Zerbini, A.N.; di Sciara, G.N. Satellite Tagging of Mediterranean Fin Whales: Working towards the Identification of Critical Habitats and the Focussing of Mitigation Measures. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.R.; Richardson, W.J.; Yazvenko, S.B.; Blokhin, S.A.; Gailey, G.; Jenkerson, M.R.; Meier, S.K.; Melton, H.R.; Newcomer, M.W.; Perlov, A.S.; et al. A Western Gray Whale Mitigation and Monitoring Program for a 3-D Seismic Survey, Sakhalin Island, Russia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2007, 134, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chion, C.; Turgeon, S.; Cantin, G.; Michaud, R.; Ménard, N.; Lesage, V.; Parrott, L.; Beaufils, P.; Clermont, Y.; Gravel, C. A Voluntary Conservation Agreement Reduces the Risks of Lethal Collisions between Ships and Whales in the St. Lawrence Estuary (Québec, Canada): From Co-Construction to Monitoring Compliance and Assessing Effectiveness. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0202560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waerebeek, K.V.; Baker, A.N.; Félix, F.; Gedamke, J.; Iñiguez, M.; Sanino, G.P.; Secchi, E.; Sutaria, D.; Helden, A. van; Wang, Y. Vessel Collisions with Small Cetaceans Worldwide and with Large Whales in the Southern Hemisphere, an Initial Assessment. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Mamm. 2007, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, G.; Bressem, M.F.V.; Willson, A.; Collins, T.; Harthi, S.A.; Willson, M.S.; Baldwin, R.; Leslie, M.; Waerebeek, K.V. Visual Health Assessment and Evaluation of Anthropogenic Threats to Arabian Sea Humpback Whales in Oman. J Cetacean Res Manage 2022, 23, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vere, A.J.; Lilley, M.K.; Frick, E.E. Anthropogenic Impacts on the Welfare of Wild Marine Mammals. Aquat. Mamm. 2018, 44, 150–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, J.O.; Hyndman, T.H. Underaddressed Animal-welfare Issues in Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2018; cobi.13267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C.; Bejder, L.; Green, L.; Johnson, C.; Keeling, L.; Noren, D.; Van der Hoop, J.; Simmonds, M. Anthropogenic Threats to Wild Cetacean Welfare and a Tool to Inform Policy in This Area. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, D. A History of Animal Welfare Science. Acta Biotheor. 2011, 59, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.J.; Adolphs, R. A Framework for Studying Emotions across Species. Cell 2014, 157, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, D. Toward a Synthesis of Conservation and Animal Welfare Science. Anim. Welf. 2010, 19, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.; Fernández Ajó, A.A.; Lowe, C.; Burgess, E.; Buck, C.L. A Tale of Two Whales: Putting Physiological Tools to Work for North Atlantic and Southern Right Whalesputting Physiological Tools to Work for North Atlantic and Southern Right Whales. In; 2020; pp. 205–226 ISBN 978-0-19-884361-0.

- Lennox, R.J.; Chapman, J.M.; Souliere, C.M.; Tudorache, C.; Wikelski, M.; Metcalfe, J.D.; Cooke, S.J. Conservation Physiology of Animal Migration. Conserv. Physiol. 2016, 4, cov072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paquet, P.C. Wildlife Conservation and Animal Welfare: Two Sides of the Same Coin? Marine Ecology View Project Recovery Efforts for Southern Resident Killer Whales View Project. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kareiva, P.; Marvier, M. What Is Conservation Science? BioScience 2012, 62, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skandrani, Z. From “What Is” to “What Should Become” Conservation Biology? Reflections on the Discipline’s Ethical Fundaments. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2016, 29, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, A. Report of the Workshop to Support the IWC’s Consideration of Non-Hunting Related Aspects of Cetacean Welfare, Kruger, S Africa, 2 to 6 May 2016; Proceedings International Whaling Commission: Cambridge, 2017; Vol. IWC BT-; [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, S.; Fenwick, N.; Ryan, E.A.; Baker, L.; Baker, S.E.; Beausoleil, N.J.; Carter, S.; Cartwright, B.; Costa, F.; Draper, C.; et al. International Consensus Principles for Ethical Wildlife Control. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallach, A.D.; Bekoff, M.; Batavia, C.; Nelson, M.P.; Ramp, D. Summoning Compassion to Address the Challenges of Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 32, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doniol-Valcroze, T.; Berteaux, D.; Larouche, P.; Sears, R. Influence of Thermal Fronts on Habitat Selection by Four Rorqual Whale Species in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007, 335, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesage, V.; Gosselin, J.-F.; Hammill, M.; Kingsley, M.C.; Lawson, J. Ecologically and Biologically Significant Areas (EBSAs) in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence, a Marine Mammal Perspective. Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schleimer, A.; Ramp, C.; Plourde, S.; Lehoux, C.; Sears, R.; Hammond, P. Spatio-Temporal Patterns in Fin Whale Balaenoptera Physalus Habitat Use in the Northern Gulf of St. Lawrence. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2019, 623, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevick, P.T.; Allen, J.; Clapham, P.J.; Katona, S.K.; Larsen, F.; Lien, J.; Mattila, D.K.; Palsbøll, P.J.; Sears, R.; Sigurjónsson, J.; et al. Population Spatial Structuring on the Feeding Grounds in North Atlantic Humpback Whales ( Megaptera Novaeangliae ). J. Zool. 2006, 270, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilchuk, K.; Lesage, V.; Ramp, C.; Sears, R.; Bérubé, M.; Bearhop, S.; Beauplet, G. Trophic Niche Partitioning among Sympatric Baleen Whale Species Following the Collapse of Groundfish Stocks in the Northwest Atlantic. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2014, 497, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Berrow, S.D.; McHugh, B.; O’Donnell, C.; Trueman, C.N.; O’Connor, I. Prey Preferences of Sympatric Fin ( Balaenoptera Physalus ) and Humpback ( Megaptera Novaeangliae ) Whales Revealed by Stable Isotope Mixing Models. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2014, 30, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, A. A Review of Food of Balaenopterid Whales. Sci. Rep. Whales Res. Inst. 1980, 32, 155–197. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, P.; Sévigny, C.; Bourgault, D.; Dumont, D. Sea Ice Interannual Variability and Sensitivity to Fall Oceanic Conditions and Winter Air Temperature in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Canada. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ramp, C.; Delarue, J.; Palsbøll, P.J.; Sears, R.; Hammond, P.S. Adapting to a Warmer Ocean—Seasonal Shift of Baleen Whale Movements over Three Decades. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0121374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welfare Quality ® Assessment Protocol for Pigs; 2009;

- De Jong, I.C.; Hindle, V.A.; Butterworth, A.; Engel, B.; Ferrari, P.; Gunnink, H.; Moya, T.P.; Tuyttens, F.A.M.; Van Reenen, C.G. Simplifying the Welfare Quality® Assessment Protocol for Broiler Chicken Welfare. Animal 2016, 10, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, H.; Walters, H.; Vancia, V.; Connelly, L.; Waran, N. Development of a Robust Canine Welfare Assessment Protocol for Use in Dog (Canis Familiaris) Catch-Neuter-Return (CNR) Programmes. Animals 2019, 9, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, A.; Moles, X.; Pallisera, J. Animal Welfare Assessment Protocol for Does, Bucks, and Kit Rabbits Reared for Production. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansiddhi, P.; Brown, J.L.; Thitaram, C. Welfare Assessment and Activities of Captive Elephants in Thailand. Animals 2020, 10, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toni, M.; Manciocco, A.; Angiulli, E.; Alleva, E.; Cioni, C.; Malavasi, S. Assessing Fish Welfare in Research and Aquaculture, with a Focus on European Directives. Animal 2019, 13, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.M.; Beausoleil, N.J.; Ramp, D.; Mellor, D.J. A Ten-Stage Protocol for Assessing the Welfare of Individual Non-Captive Wild Animals: Free- Roaming Horses (Equus Ferus Caballus) as an Example. Animals 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.M.; Beausoleil, N.J.; Ramp, D.; Mellor, D.J. Mental Experiences in Wild Animals: Scientifically Validating Measurable Welfare Indicators in Free-Roaming Horses. Anim. Open Access J. MDPI 2023, 13, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleby, M.C.; Olsson, A.S.; Galindo, F. Animal Welfare, 3rd Edition; CABI, 2018; ISBN 978-1-78639-020-2.

- Mellor, D.J.; Patterson-Kane, Emily.; Stafford, K.J. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. In The Sciences of Animal Welfare; Wiley-Blackwell, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4443-0769-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, D.J.; Beausoleil, N.J.; Littlewood, K.E.; McLean, A.N.; McGreevy, P.D.; Jones, B.; Wilkins, C. The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including Human–Animal Interactions in Assessments of Animal Welfare. Anim. 2020 Vol 10 Page 1870 2020, 10, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viksten, S.M.; Visser, E.K.; Nyman, S.; Blokhuis, H.J. Developing a Horse Welfare Assessment Protocol. Anim. Welf. 2017, 26, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, P.R.; Maloney, S.K. ; Blache, & D. Review of Sheep Body Condition Score in Relation to Production Characteristics. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.L.; Bang, H.T.; Ji, S.Y.; Jeong, J.Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.D.; Lee, Y.K.; Reddy, K.E.; Kim, K.H. A Simple Method to Evaluate Body Condition Score to Maintain theoptimal Body Weight in Dogs. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2019, 61, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, E.; Raspa, F.; Giribaldi, M.; Barbero, R.; Bergagna, S.; Antoniazzi, S.; McLean, A.K.; Minero, M.; Cavallarin, L. A Functional Approach to the Body Condition Assessment of Lactating Donkeys as a Tool for Welfare Evaluation. PeerJ 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Aguilar, M.D.; Escribano, D.; Martínez-Miró, S.; López-Arjona, M.; Rubio, C.P.; Martínez-Subiela, S.; Cerón, J.J.; Tecles, F. Application of a Score for Evaluation of Pain, Distress and Discomfort in Pigs with Lameness and Prolapses: Correlation with Saliva Biomarkers and Severity of the Disease. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 126, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, K.G.; Dent, E.V.; Wilson, D.A.; Janicek, J.; Kramer, J.; LaCarruba, A.; Walsh, D.M.; Cassels, M.W.; ESTHER, T.M.; SCHILTZ, P.; et al. Repeatability of Subjective Evaluation of Lameness in Horses. Equine Vet. J. 2010, 42, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerlink, I.; Peijnenburg, M.; Wemelsfelder, F.; Turner, S.P. Emotions after Victory or Defeat Assessed through Qualitative Behavioural Assessment, Skin Lesions and Blood Parameters in Pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 183, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whay, H.R.; Main, D.C.J.; Green, L.E.; Webster, A.J.F. Assessment of the Welfare of Dairy Caftle Using Animal-Based Measurements: Direct Observations and Investigation of Farm Records. Vet. Rec. 2003, 153, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonde, M.; Rousing, T.; Badsberg, J.H.; Sørensen, J.T. Associations between Lying-down Behaviour Problems and Body Condition, Limb Disorders and Skin Lesions of Lactating Sows Housed in Farrowing Crates in Commercial Sow Herds. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2004, 87, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, A.J.F.; Main, D.C.J.; Whay, H.R. Welfare Assessment: Indices from Clinical Observation. Anim. Welf. 2004, 13, S93–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, I.L.K.; Borger-Turner, J.L.; Eskelinen, H.C. C-Well: The Development of a Welfare Assessment Index for Captive Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops Truncatus). Anim. Welf. 2015, 24, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressem, M.-F.V.; Bertulli1, C.G.; Cecchetti, A.; Van Bressem, M.-F.; Van Waerebeek, K. Skin Disorders in Common Minke Whales and White-Beaked Dolphins off Iceland, a Photographic Assessment; 2014;

- Hermosilla, C.; Silva, L.M.R.; Prieto, R.; Kleinertz, S.; Taubert, A.; Silva, M.A. Endo- and Ectoparasites of Large Whales (Cetartiodactyla: Balaenopteridae, Physeteridae): Overcoming Difficulties in Obtaining Appropriate Samples by Non- and Minimally-Invasive Methods. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2015, 4, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.E.; Moore, M.J.; Rolland, R.M.; Kellar, N.M.; Hall, A.J.; Kershaw, J.; Raverty, S.A.; Davis, C.E.; Yeates, L.C.; Fauquier, D.A.; et al. Overcoming the Challenges of Studying Conservation Physiology in Large Whales: A Review of Available Methods. Conserv. Physiol. 2013, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.E.; Rolland, R.M.; Kraus, S.D. Conservation Physiology of an Uncatchable Animal: The North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena Glacialis). Integr. Comp. Biol. 2015, 55, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramp, C.; Gaspard, D.; Gavrilchuk, K.; Unger, M.; Schleimer, A.; Delarue, J.; Landry, S.; Sears, R. Up in the Air: Drone Images Reveal Underestimation of Entanglement Rates in Large Rorqual Whales. Endanger. Species Res. 2021, 44, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bressem, M.-F.E.; Flach, L.; Reyes, J.C.; Echegaray, M.; Santos, M.; Viddi, F.; Félix, F.; Lodi, L.; Van Waerebeek, K. Epidemiological Characteristics of Skin Disorders in Cetaceans from South American Waters. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Mamm. 2015, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, H.J. The Adipocyte as an Endocrine Organ in the Regulation of Metabolic Homeostasis. Neuropharmacology 2012, 63, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yun, K.; Mu, R. A Review on the Biology and Properties of Adipose Tissue Macrophages Involved in Adipose Tissue Physiological and Pathophysiological Processes. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, C.L.; Hunt, K.E.; Robbins, J.; Seton, R.E.; Rogers, M.; Gabriele, C.M.; Neilson, J.L.; Landry, S.; Teerlink, S.S.; Buck, C.L. Patterns of Cortisol and Corticosterone Concentrations in Humpback Whale (Megaptera Novaeangliae) Baleen Are Associated with Different Causes of Death. Conserv. Physiol. 2021, 9, coab096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, H.N.; Karr, L.K.; Shrader, T.C.; Yates, D.T. Allostatic Load Index Effectively Measures Chronic Stress Status in Zoo-Housed Giraffes. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2023, 4, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanninger, E.-M.; Selling, J.; Heyer, K.; Burkhardt-Holm, P. Skin Conditions, Epizoa, Ectoparasites and Emaciation in Cetaceans in the Strait of Gibraltar: An Update for the Period 2016-2020. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 2023, 24, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Li, K.; Rehman, M.U.; Nawaz, S.; Kulyar, M.F.-A.; Hu, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; An, M.; et al. Detection of Culex Tritaeniorhynchus Giles and Novel Recombinant Strain of Lumpy Skin Disease Virus Causes High Mortality in Yaks. Viruses 2023, 15, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raverty, S.; Leger, J.S.; Noren, D.P.; Huntington, K.B.; Rotstein, D.S.; Gulland, F.M.D.; Ford, J.K.B.; Hanson, M.B.; Lambourn, D.M.; Huggins, J.; et al. Pathology Findings and Correlation with Body Condition Index in Stranded Killer Whales (Orcinus Orca) in the Northeastern Pacific and Hawaii from 2004 to 2013. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0242505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D. (David G.) Understanding Animal Welfare : The Science in Its Cultural Context; Wiley-Blackwell, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4443-0948-5.

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Mellor, D.J.; Cronin, G.M.; Tilbrook, A.J. Scientific Assessment of Animal Welfare. N. Z. Vet. J. 2015, 63, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrillon, J.; Bengtson Nash, S. Evaluating Cetacean Body Condition; a Review of Traditional Approaches and New Developments. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 6144–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockyer, C. All Creatures Great and Smaller: A Study in Cetacean Life History Energetics. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2007, 87, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachtendonk, R.; Calambokidis, J.; Flynn, K. Blue Whale Body Condition Assessed Over a 14-Year Period in the NE Pacific: Annual Variation and Connection to Measures of Ocean Productivity. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettis, H.M.; Rolland, R.M.; Hamilton, P.K.; Brault, S.; Knowlton, A.R.; Kraus, S.D. Visual Health Assessment of North Atlantic Right Whales (Eubalaena Glacialis) Using Photographs. Can. J. Zool. 2004, 82, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.J.; Rowles, T.K.; Fauquier, D.A.; Baker, J.D.; Biedron, I.; Durban, J.W.; Hamilton, P.K.; Henry, A.G.; Knowlton, A.R.; McLellan, W.A.; et al. REVIEW: Assessing North Atlantic Right Whale Health: Threats, and Development of Tools Critical for Conservation of the Species. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2021, 143, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettis, H.; Rolland, R.; Hamilton, P.; Knowlton, A.; Burgess, E.; Kraus, S. Body Condition Changes Arising from Natural Factors and Fishing Gear Entanglements in North Atlantic Right Whales Eubalaena Glacialis. Endanger. Species Res. 2017, 32, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, R.; Schick, R.; Pettis, H.; Knowlton, A.; Hamilton, P.; Clark, J.; Kraus, S. Health of North Atlantic Right Whales Eubalaena Glacialis over Three Decades: From Individual Health to Demographic and Population Health Trends. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2016, 542, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Best, P.; Perryman, W.; Baumgartner, M.; Moore, M. Body Shape Changes Associated with Reproductive Status, Nutritive Condition and Growth in Right Whales Eubalaena Glacialis and E. Australis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012, 459, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, A.L.; Weller, D.W.; Punt, A.E.; Ivashchenko, Y.V.; Burdin, A.M.; VanBlaricom, G.R.; Brownell, R.L. Leaner Leviathans: Body Condition Variation in a Critically Endangered Whale Population. J. Mammal. 2012, 93, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joblon, M.J.; Pokras, M.A.; Morse, B.; Harry, C.T.; Rose, K.S.; Sharp, S.M.; Niemeyer, M.E.; Patchett, K.M.; Sharp, W.B.; Moore, M.J. Body Condition Scoring System for Delphinids Based on Short-Beaked Common Dolphins (Delphinus Delphis), 2008.

- Noren, S.R.; Schwarz, L.; Chase, K.; Aldrich, K.; Oss, K.M.-V.; Leger, J.S. Validation of the Photogrammetric Method to Assess Body Condition of an Odontocete, the Shortfinned Pilot Whale Globicephala Macrorhynchus. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2019, 620, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basran, C.; Bertulli, C.; Cecchetti, A.; Rasmussen, M.; Whittaker, M.; Robbins, J. First Estimates of Entanglement Rate of Humpback Whales Megaptera Novaeangliae Observed in Coastal Icelandic Waters. Endanger. Species Res. 2019, 38, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, A.L.; Weller, D.W.; Ivashchenko, Y.V.; Burdin, A.M.; Brownell, Jr, R.L. Anthropogenic Scarring of Western Gray Whales ( Eschrichtius Robustus ). Mar. Mammal Sci. 2009, 25, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.N.; Karniski, C.; Robbins, J.; Pitchford, T.; Todd, S.; Asmutis-Silvia, R. Vessel Collision Injuries on Live Humpback Whales, Megaptera Novaeangliae, in the Southern Gulf of Maine. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2017, 33, 558–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowlton, A.R.; Hamilton, P.K.; Marx, M.K.; Pettis, H.M.; Kraus, S.D. Monitoring North Atlantic Right Whale Eubalaena Glacialis Entanglement Rates: A 30 Yr Retrospective. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012, 466, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laist, D.W.; Knowlton, A.R.; Mead, J.G.; Collet, A.S.; Podesta, M. Collisions Between Ships and Whales. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2001, 17, 35–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowlton, A.R.; Marx, M.K.; Pettis, H.M.; Hamilton, P.K.; Kraus, S.D. Analysis of Scarring on North Atlantic Right Whales (Eubalaena Glacialis) Monitoring Rates of Entanglement Interaction, 1980-2002. 2005.

- Robbins, J.; Mattila, D. Estimating Humpback Whale (Megaptera Novaeangliae) Entanglement Rates on the Basis of Scar Evidence Report to The; 2004;

- Korte, S.M.; Olivier, B.; Koolhaas, J.M. A New Animal Welfare Concept Based on Allostasis. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Seeman, T. Protective and Damaging Effects of Mediators of Stress. In Elaborating and Testing the Concepts of Allostasis and Allostatic Load. In Proceedings of the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences; New York Academy of Sciences, December 1 1999; Vol. 896; pp. 30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Seeley, K.E.; Proudfoot, K.L.; Edes, A.N. The Application of Allostasis and Allostatic Load in Animal Species: A Scoping Review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulland, F.M.; Nutter, F.B.; Dixon, K.; Calambokidis, J.; Schorr, G.; Barlow, J.; Rowles, T.; Wilkin, S.; Spradlin, T.; Gage, L. Health Assessment, Antibiotic Treatment, and Behavioral Responses to Herding Efforts of a Cow-Calf Pair of Humpback Whales (Megaptera Novaeangliae) in the Sacramento River Delta, California. Aquat. Mamm. 2008, 34, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duignan, P.J.; Stephens, N.S.; Robb, K. Fresh Water Skin Disease in Dolphins: A Case Definition Based on Pathology and Environmental Factors in Australia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reif, J.S.; Mazzoil, M.S.; McCulloch, S.D.; Varela, R.A.; Goldstein, J.D.; Fair, P.A.; Bossart, G.D. Lobomycosis in Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphins from the Indian River Lagoon, Florida. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2006, 228, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bressem, M.F.; Raga, J.A.; Di Guardo, G.; Jepson, P.D.; Duignan, P.J.; Siebert, U.; Barrett, T.; De Oliveira Santos, M.C.; Moreno, I.B.; Siciliano, S.; et al. Emerging Infectious Diseases in Cetaceans Worldwide and the Possible Role of Environmental Stressors. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2009, 86, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bressem, M.-F.; Burville, B.; Sharpe, M.; Berggren, P.; Van Waerebeek, K. Visual Health Assessment of White-Beaked Dolphins off the Coast of Northumberland, North Sea, Using Underwater Photography. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2018, 34, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautek, G.; Bressem, F.V.; Ritter, F. External Body Conditions in Cetaceans from La Gomera, Canary Islands, Spain. 2019, 11.

- Toms, C.N.; Stone, T.; Och-Adams, T. Visual-only Assessments of Skin Lesions on Free-ranging Common Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops Truncatus): Reliability and Utility of Quantitative Tools. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2020, 36, 744–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertulli, C.G.; Rasmussen, M.H.; Rosso, M. An Assessment of the Natural Marking Patterns Used for Photo-Identification of Common Minke Whales and White-Beaked Dolphins in Icelandic Waters. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2016, 96, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bressem, M.F.; Burville, B.; Sharpe, M.; Berggren, P.; Van Waerebeek, K. Visual Health Assessment of White-Beaked Dolphins off the Coast of Northumberland, North Sea, Using Underwater Photography. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2018, 34, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bressem, M.-F.; Minton, G.; Collins, T.; Willson, A.; Baldwin, R.; Van Waerebeek, K. Tattoo-like Skin Disease in the Endangered Subpopulation of the Humpback Whale, Megaptera Novaeangliae, in Oman (Cetacea: Balaenopteridae). Zool. Middle East 2015, 61, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnert, K.; IJsseldijk, L.L.; Uy, M.L.; Boyi, J.O.; van Schalkwijk, L.; Tollenaar, E.A.P.; Gröne, A.; Wohlsein, P.; Siebert, U. Whale Lice (Isocyamus Deltobranchium & Isocyamus Delphinii; Cyamidae) Prevalence in Odontocetes off the German and Dutch Coasts – Morphological and Molecular Characterization and Health Implications. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2021, 15, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten, S.; Raga, J.A.; Aznar, F.J. Epibiotic Fauna on Cetaceans Worldwide: A Systematic Review of Records and Indicator Potential. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraci, J.R.; Aubin, D.J.S. Effects of Parasites on Marine Mammals. Int. J. Parasitol. 1987, 17, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJsseldijk, L.L.; van Neer, A.; Deaville, R.; Begeman, L.; van de Bildt, M.; van den Brand, J.M.A.; Brownlow, A.; Czeck, R.; Dabin, W.; Ten Doeschate, M.; et al. Beached Bachelors: An Extensive Study on the Largest Recorded Sperm Whale Physeter Macrocephalus Mortality Event in the North Sea. PloS One 2018, 13, e0201221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.G. On the Occurrence of Diatoms on the Skin of Whales. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Contain. Pap. Biol. Character 1920, 91, 352–357. [Google Scholar]

- FERNANDO, F.; Bearson, B.; Falconí, J. Epizoic Barnacles Removed from the Skin of a Humpback Whale after a Period of Intense Surface Activity. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2006, 22, 979–984. [Google Scholar]

- Omura, H. Diatom Infection on Blue and Fin Whales in the Autarctic Whaling Area V-the Ross Sea Area. Sci. Rep. Whales Res. Inst. 1950, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, M.A.; Huber, D.; Travis, K.; Doosey, M.H.; Ford, J.; Decker, S.; Mann, J. Simulating Cookiecutter Shark Bites with a 3D-Printed Jaw-Dental Model. Zoomorphology 2023, 142, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, V.A.; Ng, K.; Kaneshige, J.; Furuta, S.; Hayashi, M.S. Cookiecutter Shark-Related Injuries: A New Threat to Swimming Across the Ka’iwi Channel. Hawaii J. Health Soc. Welf. 2021, 80, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stepchew, C.; Yaipen-Llanos, C.F. Marine Mammals in Peru with Cookiecutter Shark Bites (Isistius Brasiliensis): First Record of Interspecific Interactions.

- Brown, E.J.; Vosloo, A. The Involvement of the Hypothalamopituitary-Adrenocortical Axis in Stress Physiology and Its Significance in the Assessment of Animal Welfare in Cattle. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2017, 84, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Williamson, G.M. Stress and Infectious Disease in Humans. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 109, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godbout, J.P.; Glaser, R. Stress-Induced Immune Dysregulation: Implications for Wound Healing, Infectious Disease and Cancer. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006, 1, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herr, H.; Viquerat, S.; Naujocks, T.; Gregory, B.; Lees, A.; Devas, F. Skin Condition of Fin Whales at Antarctic Feeding Grounds Reveals Little Evidence for Anthropogenic Impacts and High Prevalence of Cookiecutter Shark Bite Lesions. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2022, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shears, G.M.; Bertulli, C.B.; Rasmussen, M.H.; Basran, C.; McCormick, K.; Stevick, P.T.; Todd, S.K. Documentation of Scarification Type, Frequency and Persistence in Icelandic Humpback Whales in Skjálfandi Bay. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Council on Animal Care CCAC Guidelines: Wildlife; 2023. ISBN 978-0-919087-97-2.

- Agler, B. Testing the Reliability of Photographic Identification of Individual Fin Whales (Balaenoptera Physalus). Ret Int Whal Commn 1992, 42, 731–737. [Google Scholar]

- Katona, S.K.; Whitehead, H.P. Identifying Humpback Whales Using Their Natural Markings. Polar Rec. 1981, 20, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeseman, T.; Southerland, K.; Acebes, J.M.; Audley, K.; Barlow, J.; Bejder, L.; Birdsall, C.; Bradford, A.L.; Byington, J.K.; Calambokidis, J.; et al. A Collaborative and Near-Comprehensive North Pacific Humpback Whale Photo-ID Dataset. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, A.L.; Weller, D.W.; Punt, A.E.; Ivashchenko, Y.V.; Burdin, A.M.; VanBlaricom, G.R.; Brownell, R.L. Leaner Leviathans: Body Condition Variation in a Critically Endangered Whale Population. J. Mammal. 2012, 93, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, P.; Chassé, J.; Gilbert, D.; Larouche, P.; Brickman, D.; Pettigrew, B.; Devine, L.; Gosselin, A.; Pettipas, R.; LaFleur, C. Physical Oceanographic Conditions in the Gulf of St Lawrence in 2010; 2011;

- Bourdages, H.; Brassard, C.; Desgagnés, M.; Galbraith, P.; Gauthier, J.; Legaré, B.; Nozères, C.; Parent, E. Preliminary Results from the Groundfish and Shrimp Multidisciplinary Survey in August 2016 in the Estuary and Northern Gulf of St Lawrence; 2017;

- Devine, L.; Scarratt, M.; Plourde, S.; Galbraith, P.; Lehoux, C. Chemical and Biological Oceanographic Conditions in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence during 2015. 2017, 48 pp.

- Mitchell, M.R.; Harrison, G.; Pauley, K.; Gagné, A.; Maillet, G.; Strain, P. Atlantic 1025 Zonal Monitoring Program Sampling Protocol. Can Tech Rep Hydrogr Ocean Sci 2002, 223, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Z.; Jain, A.D.; Tran, D.; Yi, D.H.; Wu, F.; Zorn, A.; Ratilal, P.; Makris, N.C. Ecosystem Scale Acoustic Sensing Reveals Humpback Whale Behavior Synchronous with Herring Spawning Processes and Re-Evaluation Finds No Effect of Sonar on Humpback Song Occurrence in the Gulf of Maine in Fall 2006. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnúsdóttir, E.E.; Rasmussen, M.H.; Lammers, M.O.; Svavarsson, J. Humpback Whale Songs during Winter in Subarctic Waters. Polar Biol. 2014, 37, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourisseau, M.; Simard, Y.; Saucier, F.J. Krill Aggregation in the St. Lawrence System, and Supply of Krill to the Whale Feeding Grounds in the Estuary from the Gulf. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006, 314, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, L.S.; Olsen, A.; Smith, A.; Burnett, J.D.; Chandler, T.E.; Larson, S.; Hunt, K.E.; Torres, L.G. Stressed and Slim or Relaxed and Chubby? A Simultaneous Assessment of Gray Whale Body Condition and Hormone Variability. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2022, 38, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakoulaki, D.; Mavrotas, G.; Papayannakis, L. Determining Objective Weights in Multiple Criteria Problems: The Critic Method. Comput. Oper. Res. 1995, 22, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, F.H.; Allahviranloo, T.; Pedrycz, W.; Shahriari, M.; Sharafi, H.; GhalehJough, S.R. Fuzzy Decision Analysis: Multi Attribute Decision Making Approach; Springer Nature, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-44742-6.

- Krishnan, A.R.; Kasim, M.M.; Hamid, R.; Ghazali, M.F. A Modified CRITIC Method to Estimate the Objective Weights of Decision Criteria. Symmetry 2021, 13, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertulli, C.; Cecchetti, A.; Van Bressem, M.-F.; Van Waerebeek, K. Skin Disorders in Common Minke Whales and White-Beaked Dolphins off Iceland, a Photographic Assessment. J. Mar. Anim. Their Ecol. 2012, 5, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sanino, G.P.; Bressem, M.V.; Waerebeek, K.; Pozo, N. Skin Disorders of Coastal Dolphins at Añihué Reserve, Chilean Patagonia: A Matter of Concern.; 2014.

- Segura-Göthlin, S.; Fernández, A.; Arbelo, M.; Andrada Borzollino, M.A.; Felipe-Jiménez, I.; Colom-Rivero, A.; Fiorito, C.; Sierra, E. Viral Skin Diseases in Odontocete Cetaceans: Gross, Histopathological, and Molecular Characterization of Selected Pathogens. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1188105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.S.; Herman, L.M. Aggressive Behavior between Humpback Whales (Megaptera Novaeangliae) Wintering in Hawaiian Waters. Can. J. Zool. 1984, 62, 1922–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapham, P.J.; Palsbøll, P.J.; Mattila, D.K.; Vasquez, O. Composition and Dynamics of Humpback Whale Competitive Groups in the West Indies. Behaviour 1992, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helweg, D.A.; Herman, L.M. Diurnal Patterns of Behaviour and Group Membership of Humpback Whales (Megaptera Novaeangliae) Wintering in Hawaiian Waters. Ethology 1994, 98, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCordic, J.A.; Todd, S.K.; Stevick, P.T. Differential Rates of Killer Whale Attacks on Humpback Whales in the North Atlantic as Determined by Scarification. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2014, 94, 1311–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naessig, P.J.; Lanyon, J.M. Levels and Probable Origin of Predatory Scarring on Humpback Whales (Megaptera Novaeangliae) in East Australian Waters. Wildl. Res. 2004, 31, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, J.; Mattila, D. Monitoring Entanglements of Humpback Whales (Megaptera Novaeangliae) in the Gulf of Maine on the Basis of Caudal Peduncle Scarring. 2001.

- Denys, L. Morphology and Taxonomy of Epizoic Diatoms (Epiphalaina and Tursiocola) on a Sperm Whale (Physeter Macrocephalus) Stranded on the Coast of Belgium. Diatom Res. 1997, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.J. On the Diatoms of the Skin Film of Whales, and Their Possible Bearing on Problems of Whale Movements; Cambridge University Press. 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, S.L.; Visser, I.N. Cookie Cutter Shark (Isistius Sp.) Bites on Cetaceans, with Particular Reference to Killer Whales (Orca)(Orcinus Orca). Aquat. Mamm. 2011, 37, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.-M. An Illustrated Key to the Species of Whale-Lice (Amphipoda, Cyamidae), Ectoparasites of Cetacea, with a Guide to the Literature. Crustaceana 1967, 12, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogata, Y.; Matsumura, K. Larval Development and Settlement of a Whale Barnacle. Biol. Lett. 2006, 2, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoach, D.B.; Newton, S.D. Confirmatory Factor Analysis. BERASAGE Handb. Educ. Res. 2016, 2, 851–872. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis. 2009.

- Cheung, G.W.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Lau, R.S.; Wang, L.C. Reporting Reliability, Convergent and Discriminant Validity with Structural Equation Modeling: A Review and Best-Practice Recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2024, 41, 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinn, M.A.; Toms, C.N.; Sinclair, C.; Orbach, D.N. Seasonal Prevalence of Skin Lesions on Dolphins across a Natural Salinity Gradient. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabot, D.; Guénette, S. Physiology of Water Breathers: Effects of Temperature, Dissolved Oxygen, Salinity and pH. Clim. Change Impacts Vulnerabilities Oppor. Anal. Mar. Atl. Basin 2013, 16–44. [Google Scholar]

- Thibodeau, B.; de Vernal, A.; Mucci, A. Recent Eutrophication and Consequent Hypoxia in the Bottom Waters of the Lower St. Lawrence Estuary: Micropaleontological and Geochemical Evidence. Mar. Geol. 2006, 231, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutras, M.; Mucci, A.; Sundby, B.; Gratton, Y.; Katsev, S. Nutrient Cycling in the Lower St. Lawrence Estuary: Response to Environmental Perturbations. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2020, 239, 106715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, G.K.; Elias, P.M.; Wakefield, J.S.; Crumrine, D. Cetacean Epidermal Specialization: A Review. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2022, 51, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milstone, L.M.; Hu, R.-H.; Dziura, J.D.; Zhou, J. Impact of Epidermal Desquamation on Tissue Stores of Iron. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2012, 67, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, C.N.; Bucking, C.; Wood, C.M. The Skin of Fish as a Transport Epithelium: A Review. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2013, 183, 877–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressem, M.-F.V.; Waerebeek, K.V.; Garcia-Godos, A.; Dekegel, D.; Pastoret, P.-P. HERPES-LIKE VIRUS IN DUSKY DOLPHINS, LAGENORHYNCHUS OBSCURUS, FROM COASTAL PERU. Mar. Mammal Sci. 1994, 10, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, T.J.; Kitchell, J.F.; Bennington, V.; McKinley, G.A.; Moody, E.K.; Weidel, B.C. Climate Impacts on Landlocked Sea Lamprey: Implications for Host-Parasite Interactions and Invasive Species Management. Ecosphere 2014, 5, art68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, J.E. Marine Parasites and Disease in the Era of Global Climate Change. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2021, 13, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulland, F.M.; Baker, J.D.; Howe, M.; LaBrecque, E.; Leach, L.; Moore, S.E.; Reeves, R.R.; Thomas, P.O. A Review of Climate Change Effects on Marine Mammals in United States Waters: Past Predictions, Observed Impacts, Current Research and Conservation Imperatives. Clim. Change Ecol. 2022, 3, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandersea, M.W.; Kibler, S.R.; Tester, P.A.; Holderied, K.; Hondolero, D.E.; Powell, K.; Baird, S.; Doroff, A.; Dugan, D.; Litaker, R.W. Environmental Factors Influencing the Distribution and Abundance of Alexandrium Catenella in Kachemak Bay and Lower Cook Inlet, Alaska. Harmful Algae 2018, 77, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, K.E.; Rolland, R.M.; Kraus, S.D.; Wasser, S.K. Analysis of Fecal Glucocorticoids in the North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena Glacialis). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2006, 148, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lysiak, N.S.J.; Trumble, S.J.; Knowlton, A.R.; Moore, M.J. Characterizing the Duration and Severity of Fishing Gear Entanglement on a North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena Glacialis) Using Stable Isotopes, Steroid and Thyroid Hormones in Baleen. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, R.M.; McLellan, W.A.; Moore, M.J.; Harms, C.A.; Burgess, E.A.; Hunt, K.E. Fecal Glucocorticoids and Anthropogenic Injury and Mortality in North Atlantic Right Whales Eubalaena Glacialis. Endanger. Species Res. 2017, 34, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleimer, A.; Ramp, C.; Delarue, J.; Carpentier, A.; Bérubé, M.; Palsbøll, P.J.; Sears, R.; Hammond, P.S. Decline in Abundance and Apparent Survival Rates of Fin Whales ( Balaenoptera Physalus ) in the Northern Gulf of St. Lawrence. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 4231–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, J.L.; Ramp, C.A.; Sears, R.; Plourde, S.; Brosset, P.; Miller, P.J.; Hall, A.J. Declining Reproductive Success in the Gulf of St. Lawrence’s Humpback Whales (Megaptera Novaeangliae) Reflects Ecosystem Shifts on Their Feeding Grounds. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowlton, A.R.; Robbins, J.; Landry, S.; McKenna, H.A.; Kraus, S.D.; Werner, T.B. Effects of Fishing Rope Strength on the Severity of Large Whale Entanglements. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, L.; Rose, N.A.; Visser, I.N.; Rally, H.; Ferdowsian, H.; Slootsky, V. The Harmful Effects of Captivity and Chronic Stress on the Well-Being of Orcas (Orcinus Orca). J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 35, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Gui, D.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Xie, Q.; Yu, X.; Wu, Y. Blubber Cortisol-Based Approach to Explore the Endocrine Responses of Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphins (Sousa Chinensis) to Diet Shifts and Contaminant Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Welfare measures (criteria) | Scoring scale | Inter-Criteria Correlation weight | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fin whales | Humpbacks | ||

| Body Condition Score | 0-1-2-3-4 | 23.71% | 25.24% |

| Skin Condition Score | 0-1-2-3-4 | 18.26% | 24.08% |

| Injury/Scarring Condition Score | 0-1-2-3-4 | 24.46% | 32.91% |

| Parasite/Epibiont Condition Score | 1-2-3 | 33.57% | 17.76% |

| Total= | Weighted scores | ||

| Physical Indicator Score | Inferred welfare state | ||

|

Physical condition is optimal, suggesting comfort of good health, high functional capacity and postprandial satiety, inferring positive welfare state. Physical condition is moderate, suggesting feelings of hunger and/or psychophysical exertion, inferring moderate welfare state. Physical condition is poor, suggesting chronic pain due to hunger, psychophysical exertion and underlying pathological states, inferring negative welfare state. |

||

| Skin lesions categories | Description |

|---|---|

| Pale skin patch syndrome (PSP) |

Areas of opaque to translucent skin, light grey or whitish colouration [131]. (Figure 4.A) |

| Light-focal skin disease (LFD) |

Clusters of distinct, smallish round or oval white/light grey lesions [131]. (Figure 4.B) |

| Dark focal skin disease (DFD) |

Clusters of distinct, smallish round or oval black/dark grey lesions [131]. (Figure 4.C) |

| Tortuous cutaneous marks (TCM) | Black or white linear lesions leaving tortuous tracks, with raised or depressed patterns [132]. (Figure 4.D) |

| Tattoo skin disease-like lesions (TSD-L) |

Dark or light grey rounded borders with a characteristic stippled pattern [7,53]. (Figure 4.E) |

| Cutaneous nodules (NOD) |

Circumscribed nodules with grey or normal pigmentation [58]. (Figure 4.F) |

| Miscellaneous | Other cutaneous lesions not associated with current categories. |

| Fin whales | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion Correlation Coefficient and P values Prevalence | |||||||||||||

| TC˚ | p | S % | p | DO | p | NO-3 | p | PO3-4 | p | O3SI-2 | p | % | |

| PSP | 0.30 | .030 | -0.31 | .002 | 0.36 | .009 | 0.01 | .944 | -0.27 | .004 | 0.00 | .999 | 0.04 |

| LFD | 0.04 | .789 | 0.08 | .568 | -0.01 | .906 | 0.07 | .602 | 0.23 | .103 | 0.02 | .883 | 0.56 |

| DFD | -0.35 | .014 | -0.35 | .012 | 0.19 | .173 | -0.32 | .025 | -0.37 | .008 | 0.07 | .594 | 0.32 |

| NOD | -0.42 | .002 | -0.50 | .000 | 0.39 | .005 | 0.04 | .757 | -0.40 | .000 | 0.18 | .203 | 0.04 |

| BLL | -0.17 | .229 | -0.20 | .149 | 0.17 | .233 | -0.06 | .652 | -0.19 | .172 | 0.02 | .874 | 0.02 |

| TCM | -0.05 | .730 | 0.02 | .864 | -0.11 | .419 | 0.12 | .372 | 0.18 | .201 | 0.11 | .441 | 0.20 |

| TSD | 0.09 | .501 | 0.10 | .471 | -0.30 | .031 | -0.06 | .666 | -0.02 | .857 | -0.14 | .406 | 0.08 |

| CCW | -0.09 | .509 | -0.06 | .656 | 0.06 | .656 | 0.06 | .632 | 0.08 | .549 | 0.09 | .500 | 0.72 |

| LBM | -0.09 | .514 | -0.11 | .422 | 0.13 | .337 | 0.07 | .601 | 0.03 | .824 | 0.06 | .632 | 0.74 |

| OFD | -0.18 | .188 | -0.20 | .160 | 0.38 | .007 | 0.19 | .164 | -0.01 | .906 | 0.14 | .321 | 0.54 |

| Humpback whales | |||||||||||||

| Lesion Correlation Coefficient and P values Prevalence | |||||||||||||

| TC˚ | p | S % | p | DO | p | NO-3 | p | PO3-4 | p | O3SI-2 | p | % | |

| PSP | -0.14 | .317 | -0.19 | .182 | 0.29 | .041 | 0.17 | .222 | -0.12 | .368 | 0.16 | .263 | 0.56 |

| LFD | 0.08 | .571 | 0.06 | .631 | 0.14 | .321 | 0.32 | .063 | 0.02 | .868 | 0.16 | .241 | 0.48 |

| DFD | 0.08 | .535 | 0.01 | .893 | 0.07 | .621 | 0.05 | .679 | -0.12 | .370 | -0.04 | .739 | 0.16 |

| NOD | -0,19 | .662 | -0.19 | .182 | 0.18 | .193 | -0.06 | .667 | -0.08 | .578 | 0.02 | .858 | 0.68 |

| BLL | -0.09 | .526 | -0.16 | .265 | 0.02 | .852 | -0.37 | .008 | -0.12 | .377 | -0.29 | .044 | 0.16 |

| TCM | 0.01 | .971 | 0.09 | .528 | -0.02 | .889 | 0.22 | .120 | 0.20 | .158 | 0.19 | .180 | 0.02 |

| CCW | 0.24 | .091 | 0.26 | .063 | -0.14 | .317 | 0.27 | .054 | 0.14 | .328 | 0.15 | .284 | 0.24 |

| LBM | 0.33 | .019 | -0.08 | .560 | 0.18 | .203 | -0.38 | .006 | -0.08 | .540 | -0.25 | .075 | 0.36 |

| OFD | -0.22 | .120 | -0.24 | .083 | 0.25 | .075 | -0.02 | .845 | -0.10 | .470 | 0.01 | .972 | 0.24 |

| SL | 0.33 | .018 | -0.32 | .025 | 0.20 | .152 | -0.01 | .968 | -0.32 | .021 | -0.08 | .549 | 0.40 |

| BR | -0.31 | .026 | .038 | .005 | -0.25 | .069 | -0.02 | .873 | 0.34 | .015 | 0.03 | .810 | 0.84 |

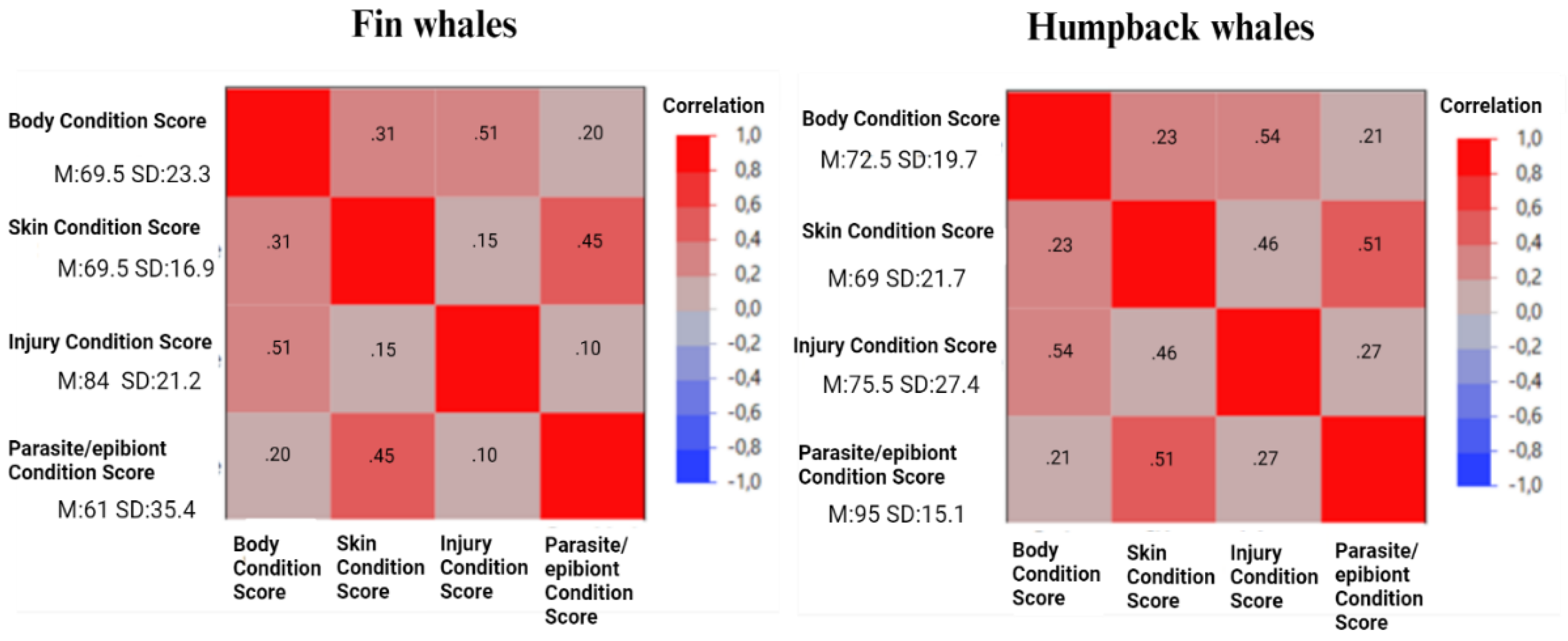

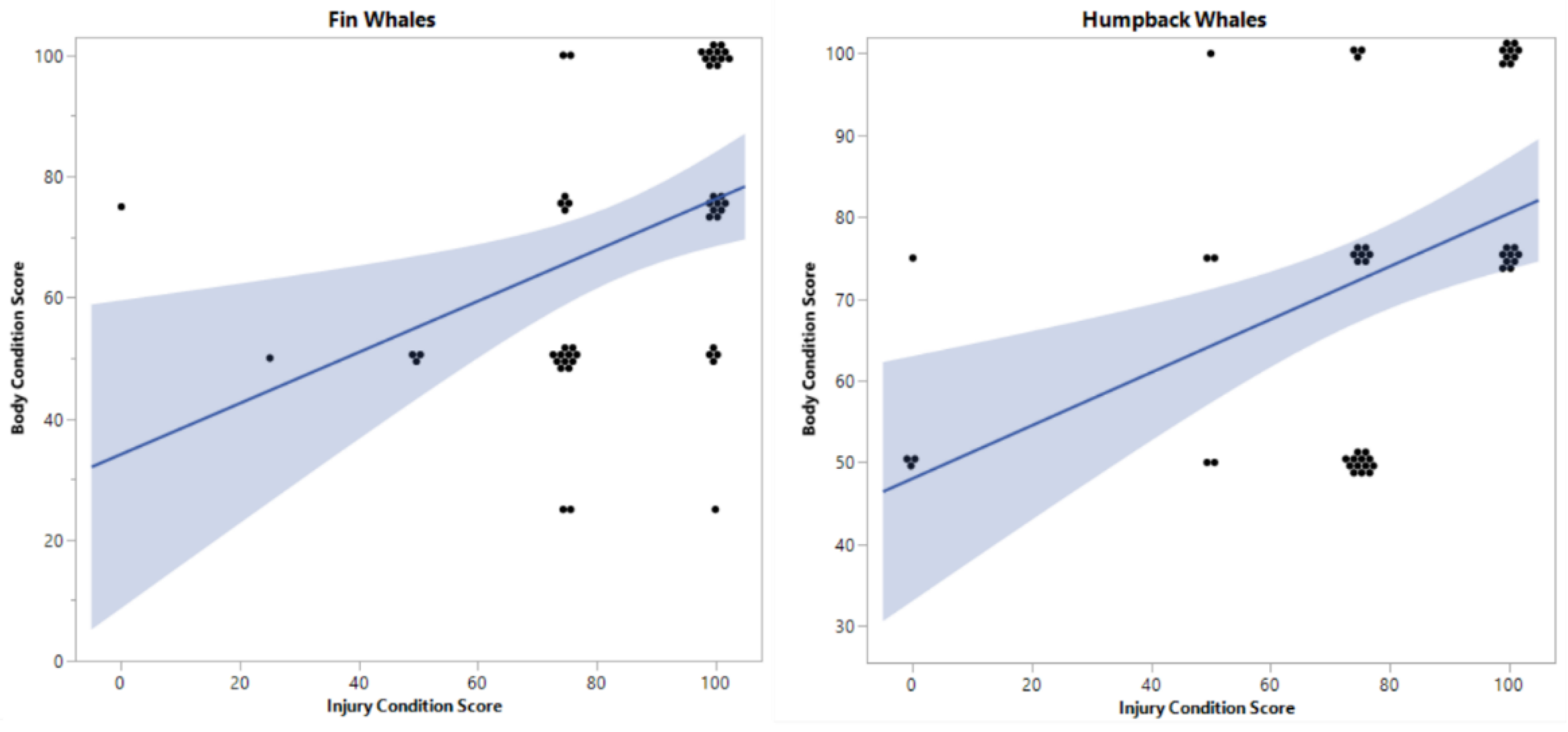

| Species | BCS | SCS | ICS | PCS | OWS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | |||||

| Bp | 69.05 (23.30) | 69.5 (16.97) | 84.0 (21.28) | 61.0 (35.41) | 70.18 (17.93) |

| Mn | 72.5 (19.72) | 69.2 (21.75) | 75.5 (27.42) | 95.2 (15.15) | 76.63 (16.10) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).