Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Related Works

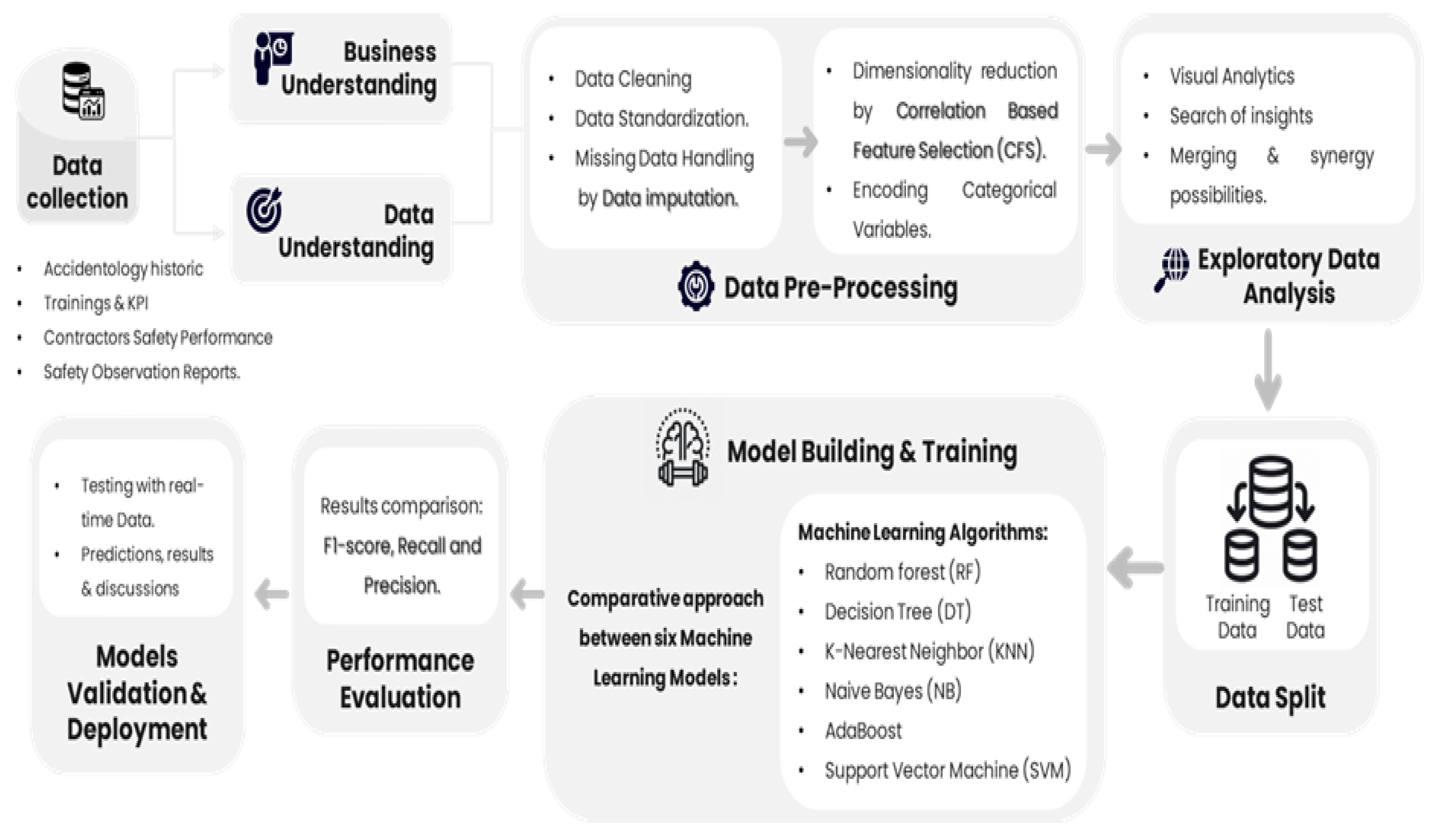

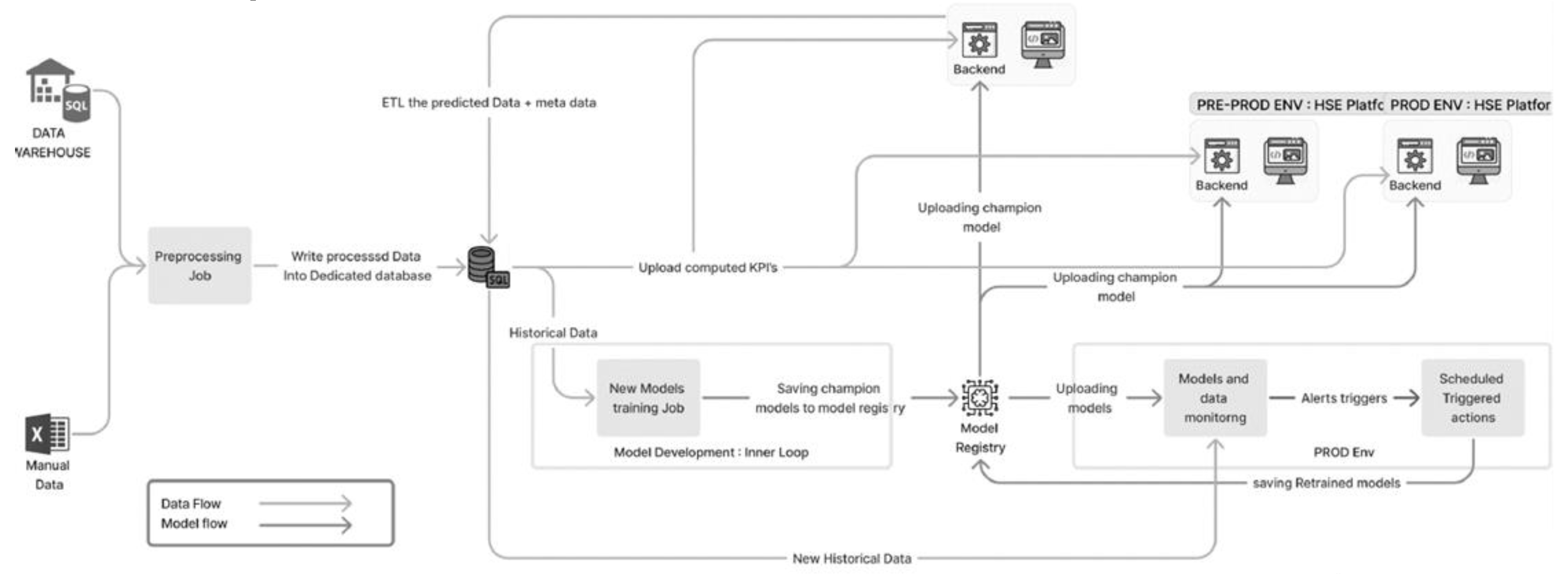

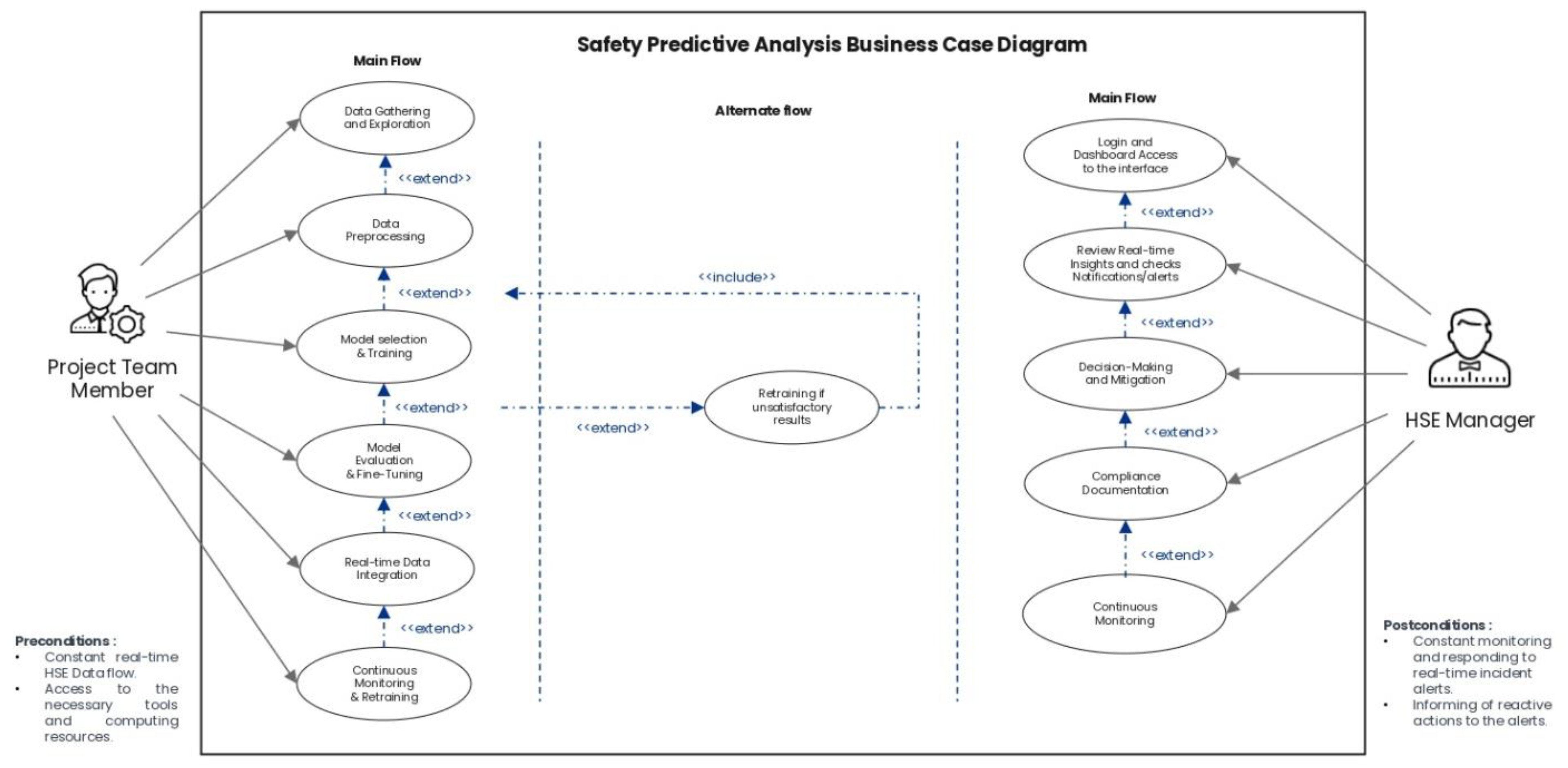

2.2. Process Overview

- Key factors or components involved in the analysis, representing the data used as input for the predictive model.

- An overview of previously employed strategies, including the problem definition, data sources, analytical methods, and an evaluation of their strengths and limitations in terms of scientific accuracy and dependability.

- Their capacity to deal with large-dimension problems, which is necessary when endeavoring to identify relevant variables among many potential factors.

- Their flexibility in reproducing the data-generation structure, irrespective of complexity, thanks to a non-linear structure that is adaptable to the data (non-parametric philosophy).

- Their great predictive and, in some cases, interpretative, potential.

2.3. Data in Use

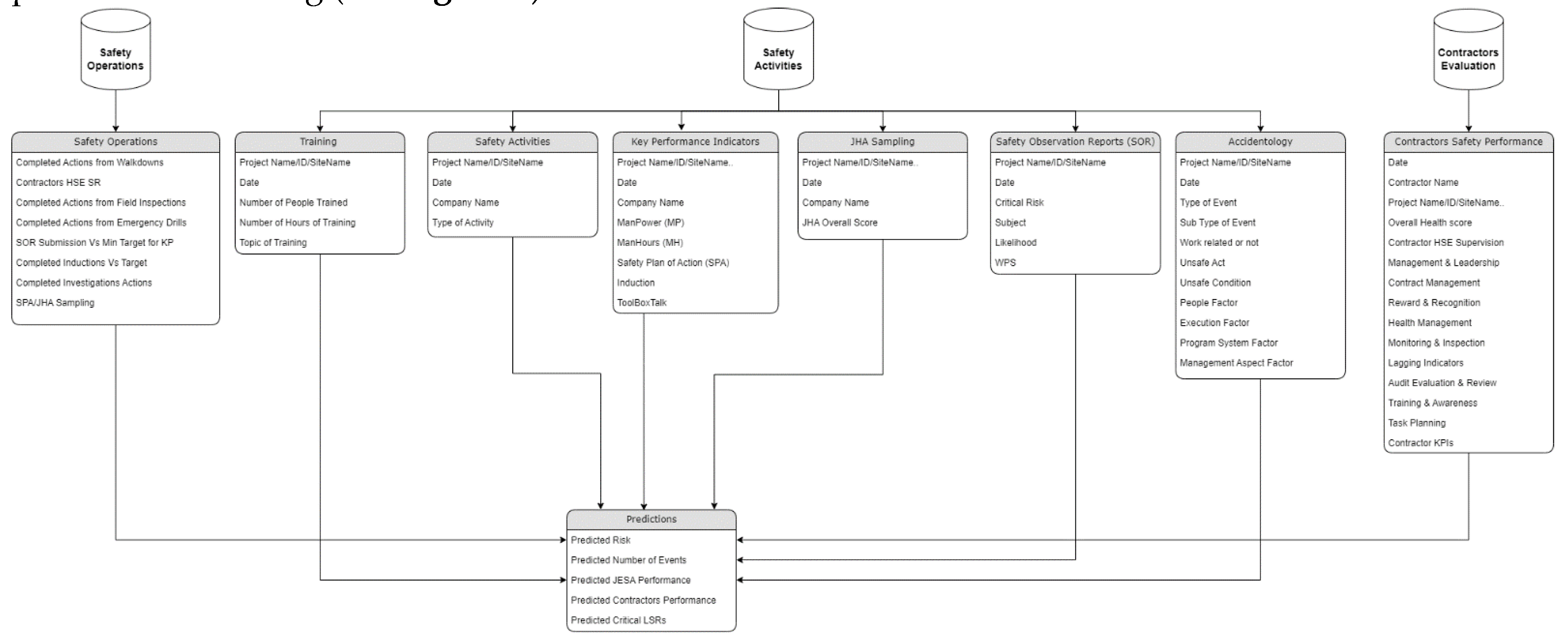

- The Safety Operations Database contains detailed records of safety observation reports, completed safety inductions, and actions implemented by field inspectors. This database captures real-time safety practices, including hazard observations and responses to identified risks. It provides critical insights into the day-to-day management of safety on construction sites and helps identify patterns of behavior or conditions that could lead to incidents.

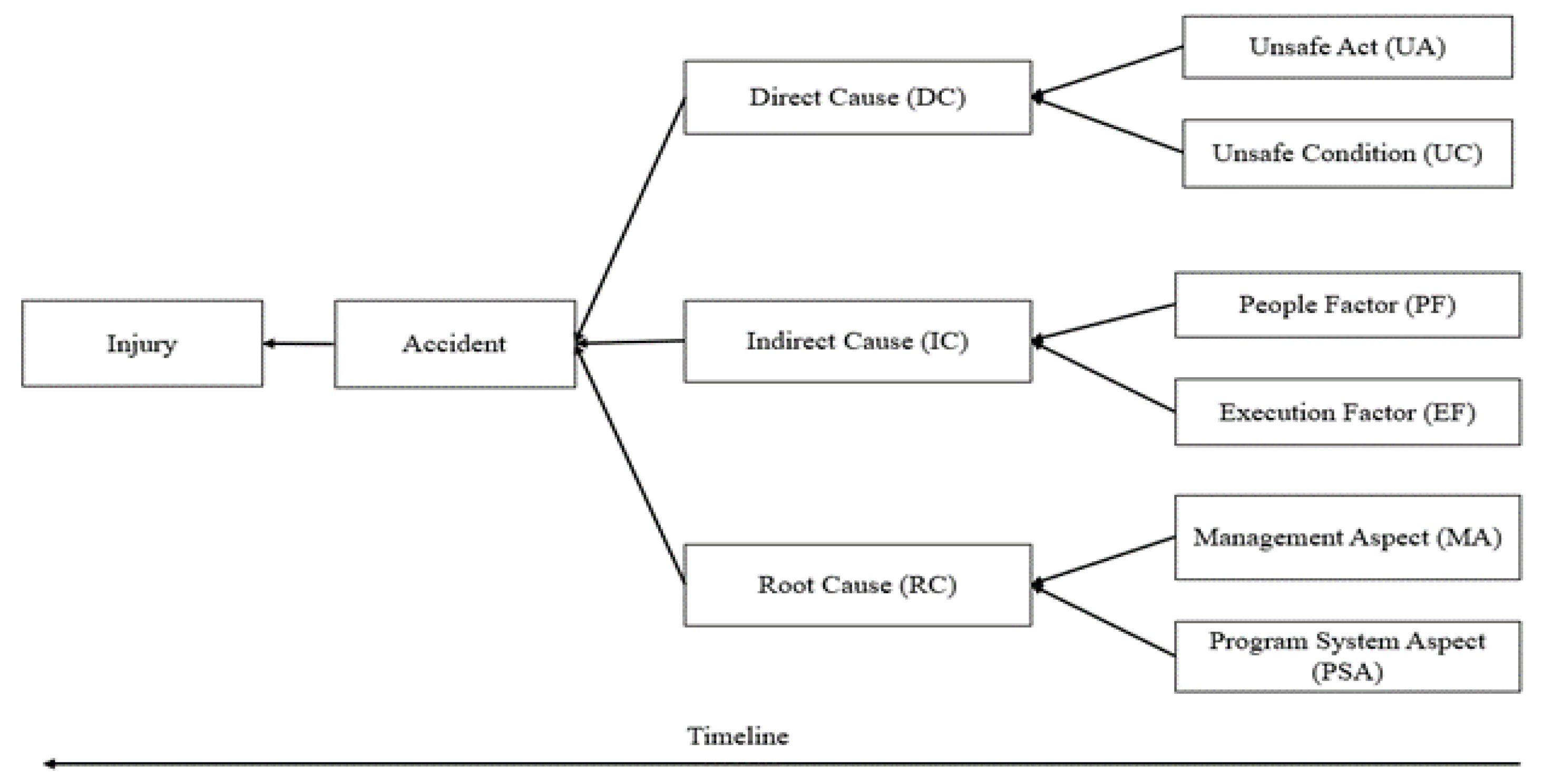

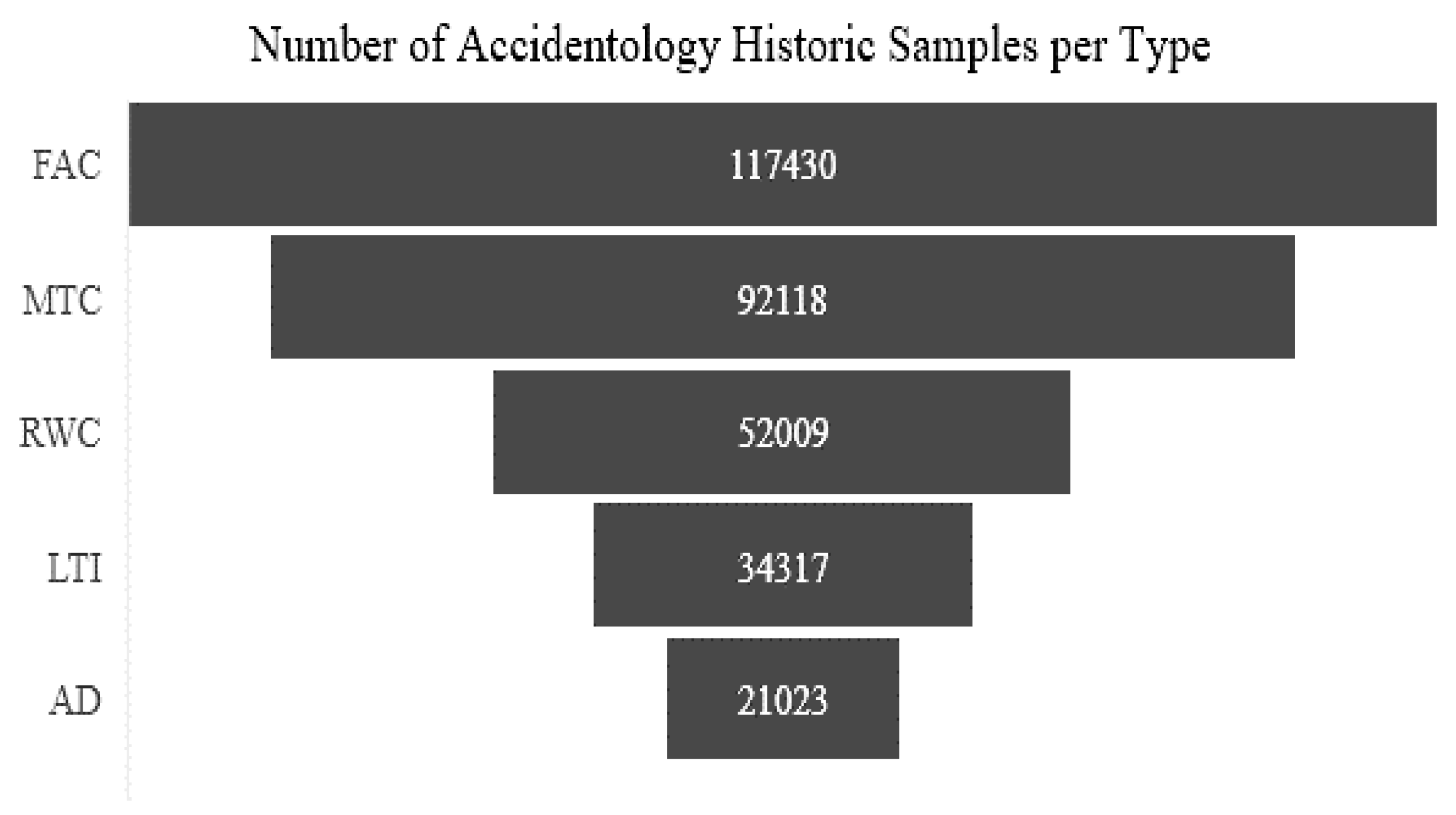

- The Safety Activities Database includes data on workforce training, critical activities conducted on-site, and key safety performance indicators. It also documents job hazard analysis (JHA) samplings, which assess the risks associated with specific tasks, and detailed historical accident data categorized into direct, indirect, and root causes. This database offers a comprehensive view of the safety measures employed and their correlation with accident occurrences, enabling a deeper understanding of proactive and reactive safety strategies.

- The Contractors’ Safety Performance Database evaluates the safety performance of contractors working on the construction sites. This database provides an overall health score for each contractor based on their compliance with safety regulations, historical performance, and the corrective measures implemented in response to previous incidents. It helps assess contractor accountability and identifies practices or teams that may pose higher risks to workplace safety.

- Volume: Over 132,500 employees across 103 sites and more than 3,000 contractors.

- Diversity: A wide range of construction activities (15 critical activities daily) and workforce demographics, reflecting real-world variability.

- Granularity: Incident data is meticulously categorized into direct, indirect, and root causes, enhancing the accuracy of the models by isolating factors contributing to accident likelihood.

- Temporal Scope: The dataset includes historical data collected over multiple years, providing a longitudinal perspective on safety trends and risks.

- Identify high-risk scenarios based on training gaps, critical activity execution, and safety inspection outcomes.

- Highlight contractor-specific risks and areas for improvement, aiding targeted interventions.

- Accurately predict accident likelihood, helping prioritize proactive measures to enhance safety and project outcomes.

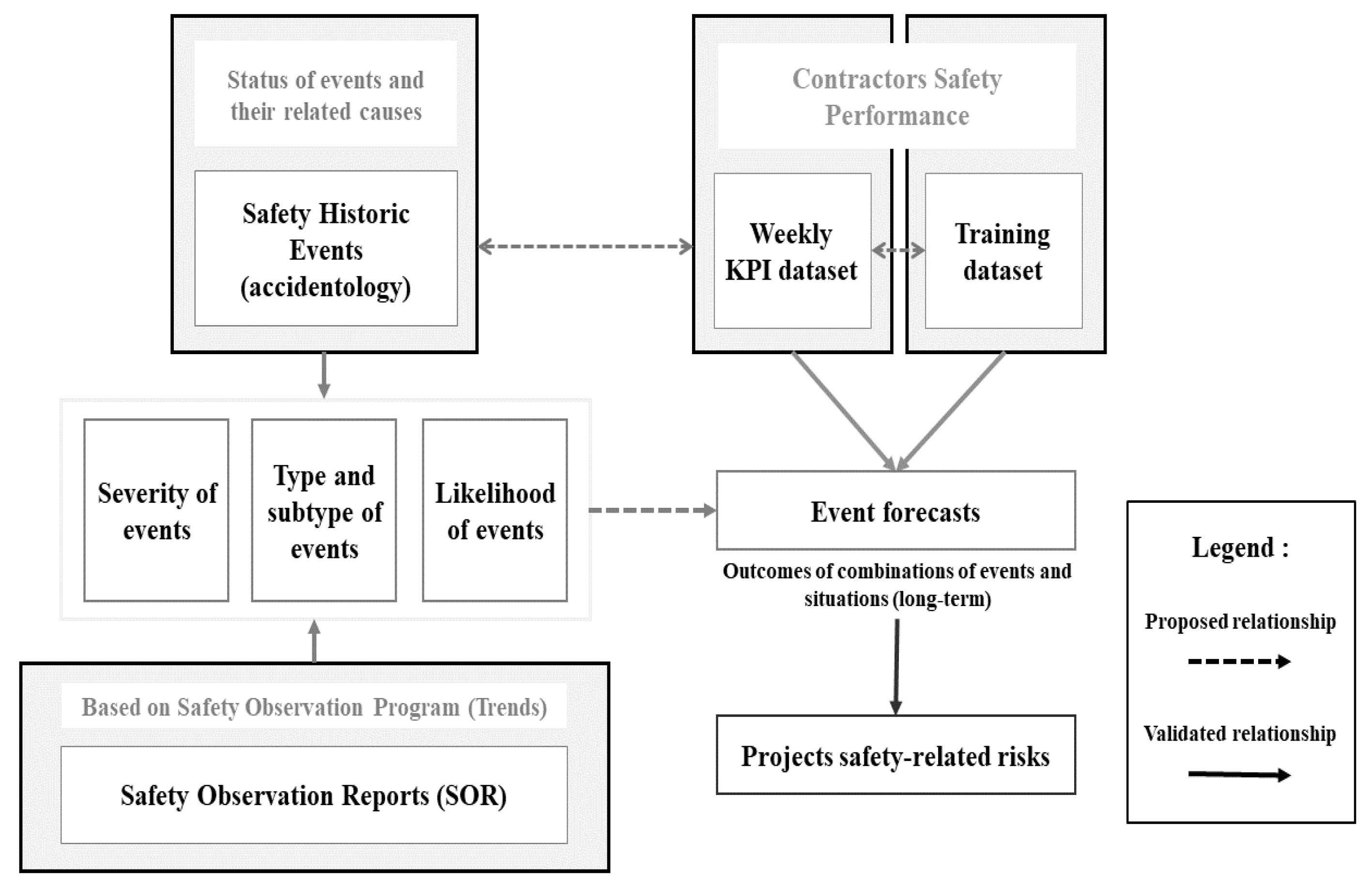

2.4. Synergy Possibilities

- Key Performance Indicators (KPI) And Training Datasets:

- Safety Observation Reports (SOR) And Preliminary Event Notifications (PEN): A Synergy of Situational Predictive Methods:

- Synergy and Cross-Validation Among Situational and Long-Term Methods

2.5. Research Hypothesis

2.5.1. Risk Mitigation Statistics

2.5.2. Theoretical Approach

- Address large-scale challenges by identifying key variables from an extensive set of possibilities.

- Replicate complex data generation processes due to their non-linear structure (non-procedural approach).

- Offer predictive capabilities, and in some cases, interpretative insights.

3. Results

3.1. Unified Model Approach

- Safety Observation Reports (SOR) & Accidentology Historical: Safety Observation Reports (SORs) and accidentology histories serve as situational methods in this context, aiming to forecast safety outcomes for individual events based on specific environmental data. We hypothesize that combining these situational methods can yield predictions that are more reliable than those obtained using a single method in isolation. For instance, Random Forest and Decision Tree algorithms excel in predicting the type of injury and identifying its direct, indirect, and root causes. However, they do not inherently predict injury severity. In contrast, Safety Observation Reports demonstrate proficiency in forecasting injury severity and have proven effective in differentiating between successful and failed safety outcomes. Thus, while both methods focus on situational predictions, they are grounded in distinct aspects of the safety system.

- Safety Key Performance Indicators Datasets: Both safety prediction families, namely safety leading indicators, and the training dataset are time-dependent, as well as safety activities and operations, typically measured over weeks or months. Consequently, they are not suited for situational predictions but rather for forecasting injury rates over extended periods, spanning months to years. While training and safety leading indicators assess distinct facets of the safety system, they may not be entirely independent. Safety leading indicators gauge the efficacy of safety management, as documented by Hinze J, Hallowell M, & Baud K. (2013), whereas training evaluates overall safety perceptions. This encompasses perceptions regarding management’s safety commitment, the role of supervisors, and the adequacy and effectiveness of training, encapsulated as “safety climate dimensions”. These perceptions may be influenced by various factors, such as the quality and quantity of training programs, audit frequency, and incentive structures. Therefore, we postulate that integrating training data with safety-leading indicators could yield synergistic effects and opportunities for cross-validation.

- Contractors Safety Performance Datasets: This section aims to predict safety performance in construction sites using contractors’ safety performance data. By analyzing the comprehensive dataset, including factors such as accident types, severity, and frequency, as well as contractor characteristics and historical safety records, examination of past safety performance, including incident rates, corrective actions taken, and adherence to safety regulations, to gauge the overall safety culture and performance trajectory. We employ various machine learning algorithms to identify patterns and predict potential safety incidents related to the accidentology historic dataset.

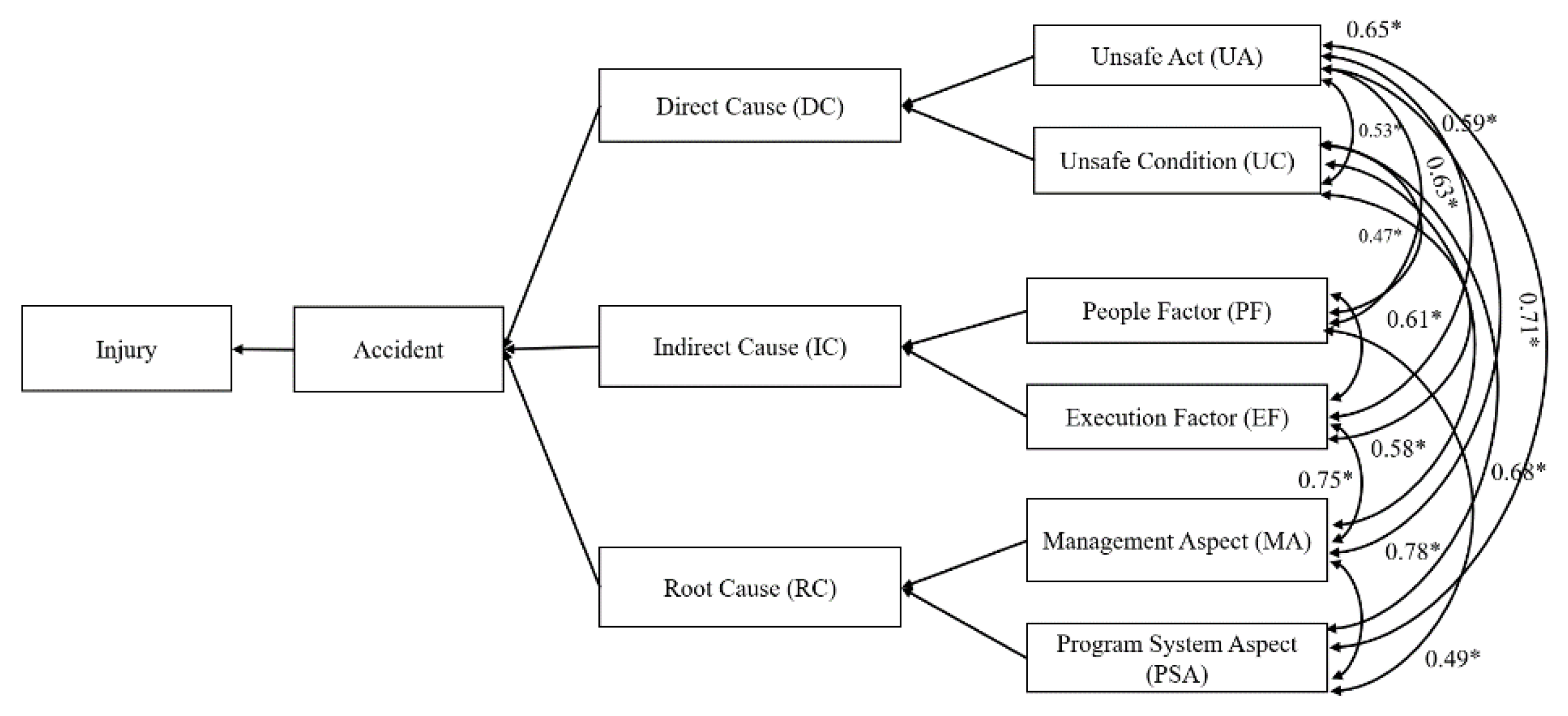

3.2. Correlation of Causal Factors

- -

- The data used for the analysis were collected from incident reports, workplace surveys, safety audits & inspections across 103 worksites. Each row in the merged datasets represents a distinct historic incident, supported by a complete and detailed investigation through multiple variables (see Figure 2) and a following plan of action that contains the safety measures needed.

- -

- Variables included in the analysis were chosen based on their relevance to workplace incidents, as determined by the literature reviews. This selection process ensured that only factors with a known or hypothesized link to accident occurrence were included.

- -

-

The relationships between variables were analyzed the matrix to quantify the strength and direction of their associations. The correlation coefficient values range from -1 to 1, where:

- -1 indicates a perfect negative relationship (one variable increases while the other decreases).

- 0 indicates no relationship.

- 1 indicates a perfect positive relationship (both variables increase or decrease together).

- -

- The statistical significance of the correlations was determined using a threshold p-value of 0.03, meaning correlations with p < 0.01 are unlikely to have occurred by chance.

- -

- The findings from the correlation matrix not only identify individual risk factors but also reveal how these factors interact. This interconnected view helps prioritize interventions and policies that address not only standalone risks but also the combined effects of multiple variables.

3.3. Impact on Accident Occurrence

3.4. Predictive Analysis of Accident Occurrence

- -

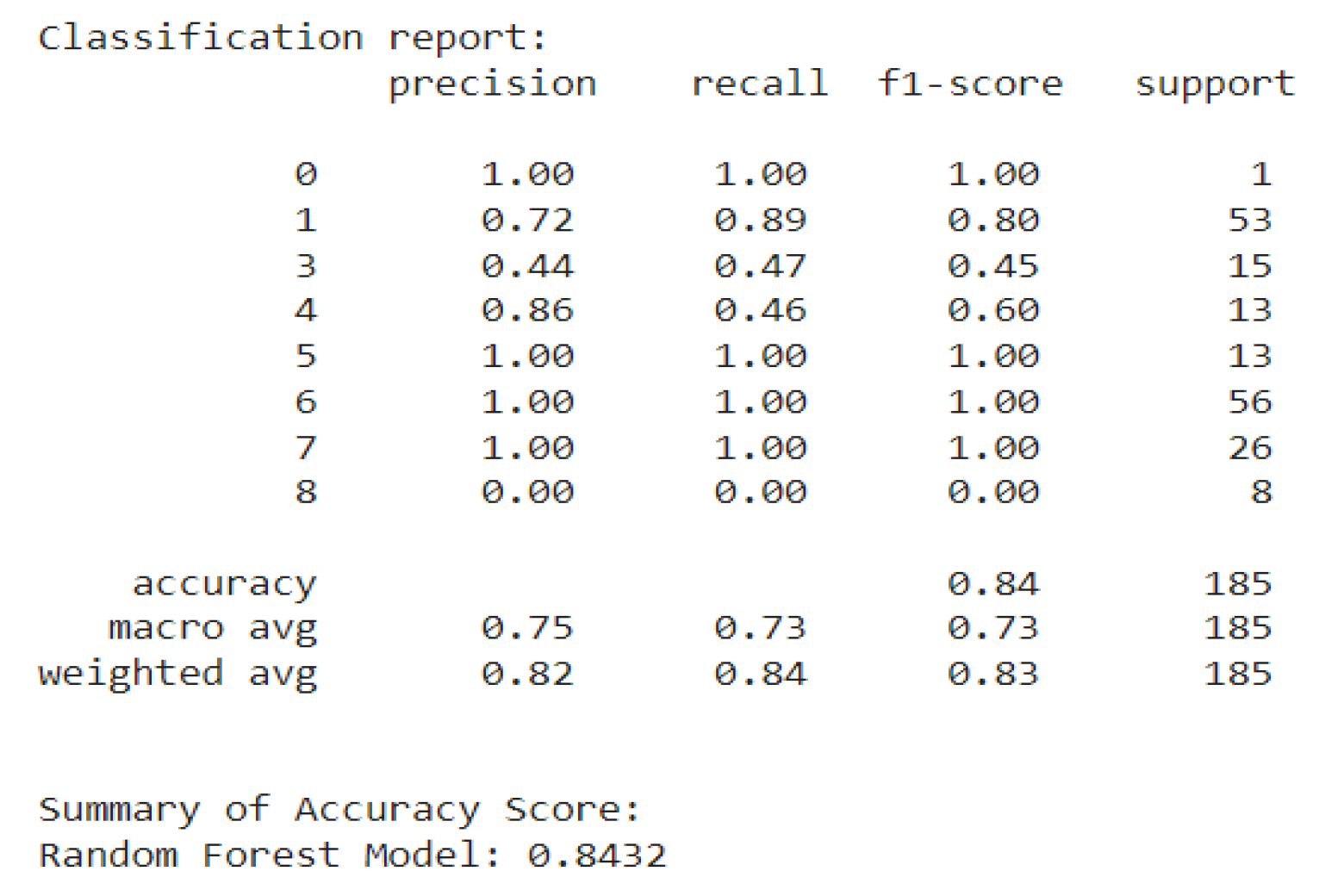

- Random forest (RF): The RF model was built using 100 decision trees, maximum tree depth of 15, minimum samples split of 2. These parameters were optimized using a grid search method to balance bias and variance, thereby minimizing overfitting while maintaining robust predictions.

- ✓

- Random Forest was used for its ability to manage complex interactions between multiple factors (Zhang, Khattak, Matara, Hussain, & Farooq, 2022) and reduce overfitting (see Figure 9).

- ✓

- The dataset was divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets using a stratified sampling technique to ensure balanced representation of accident occurrences.

- ✓

- Model performance was evaluated using standard metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall & F1-score.

- ✓

- Cross-validation was performed with k = 5 folds to ensure robustness and generalizability of the results.

- -

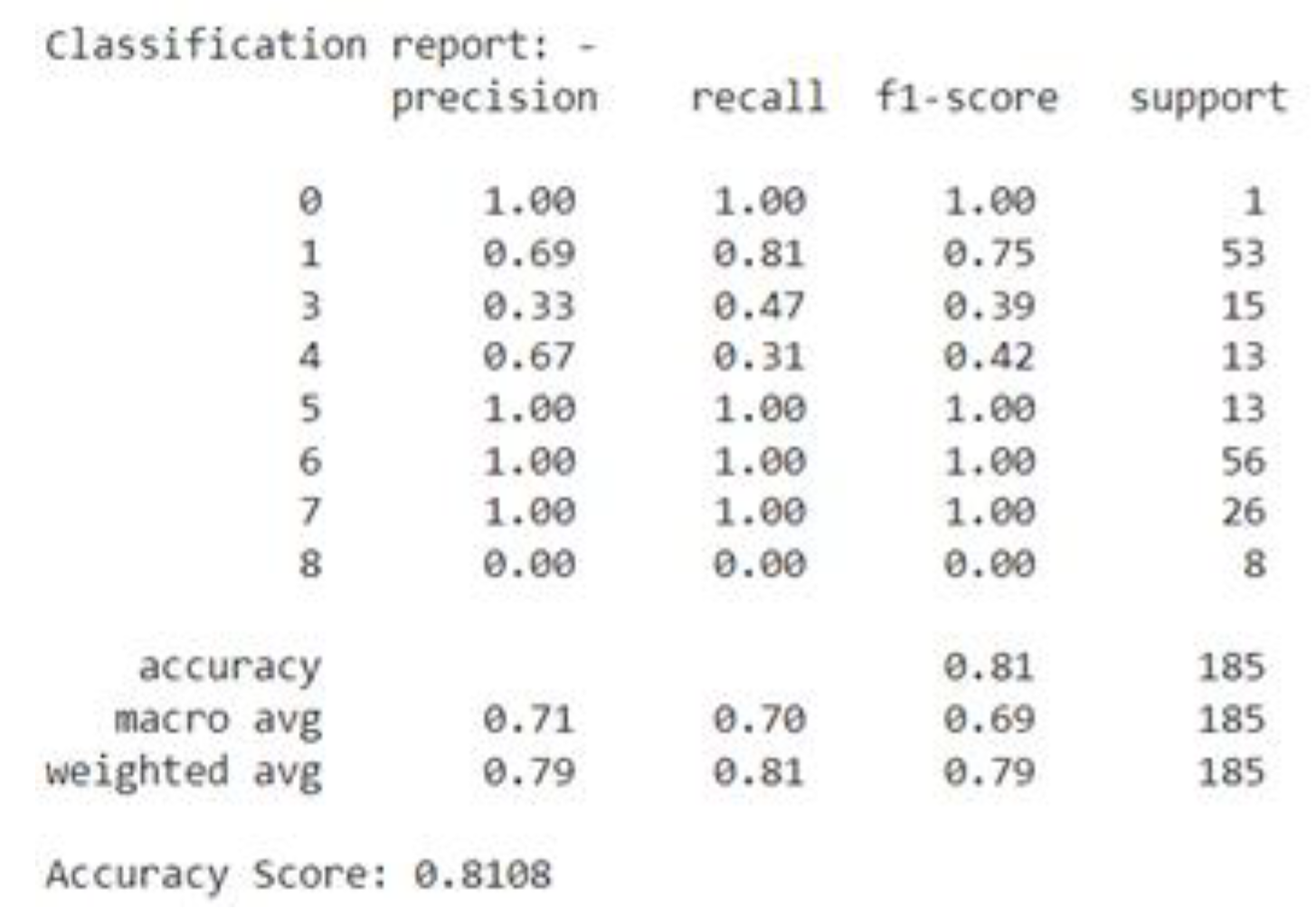

- Decision Tree (DT): Decision Tree was also incorporated (Eetvelde, Mendonça, Ley, & Tischer, 2021) to offer clear, interpretable insights into how different factors influence accident predictions (see Figure 10). Unlike other machine learning models that may function as “black boxes,” the Decision Tree offers a visual and logical breakdown of how variables and thresholds contribute to the risk prediction process.

- ✓

- Criterion for Splitting: Gini impurity was used as the splitting criterion to measure the quality of splits at each node.

- ✓

- Maximum Depth: The maximum depth of the tree was set to 5 to prevent overfitting and to enhance interpretability.

- ✓

- Minimum Samples per Split: A threshold of 10 samples per split was defined to ensure meaningful partitions.

- ✓

- Pruning Strategy: Post-pruning was applied to remove nodes that did not significantly contribute to the predictive accuracy, further simplifying the model for better generalization.

- ✓

- The dataset was divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets using stratified sampling.

- ✓

- The Decision Tree was trained using Scikit-learn in Python, and its performance was evaluated using standard metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

- ✓

- Cross-validation with k = 5 folds was conducted to ensure the robustness of the model.

- -

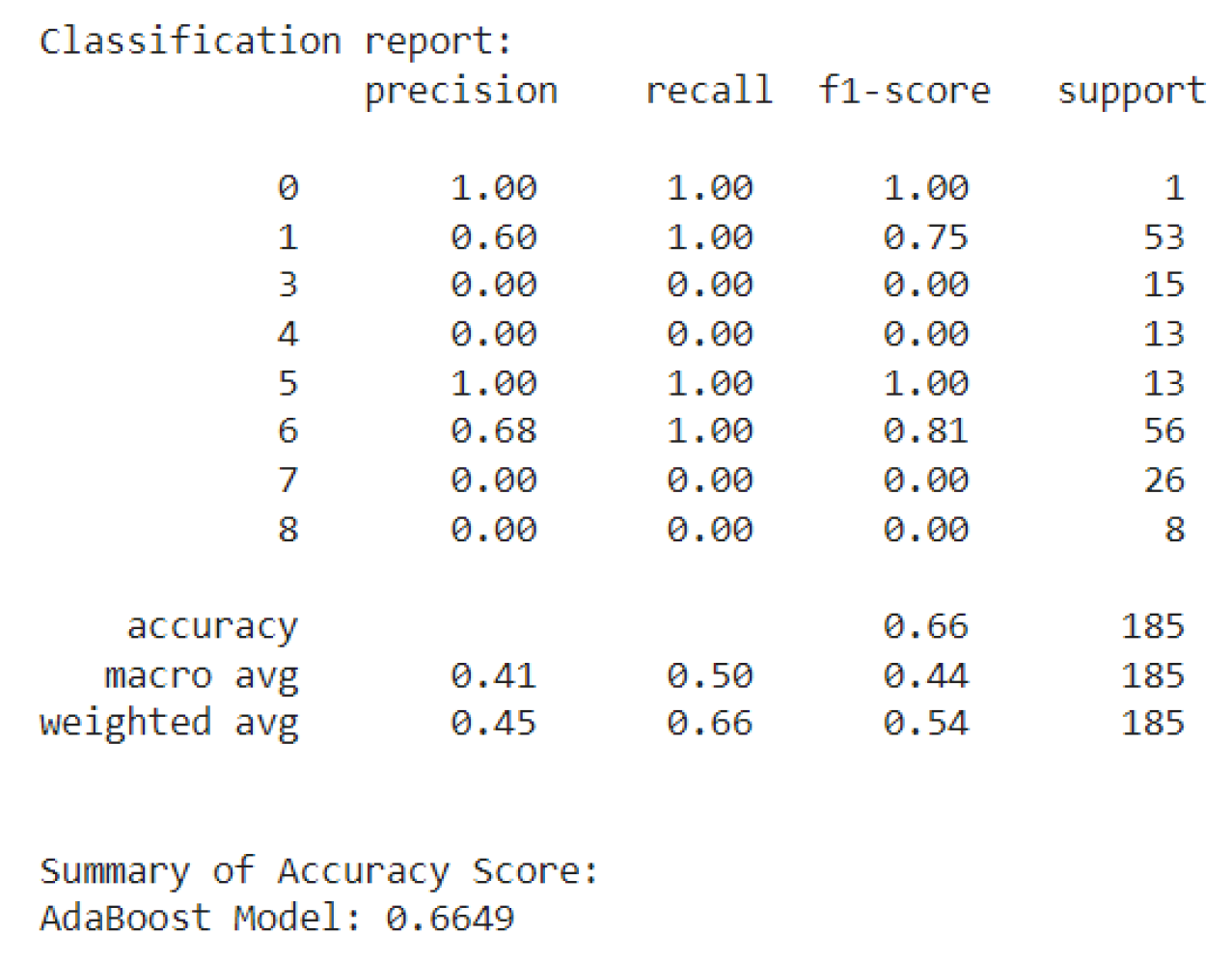

- AdaBoost: AdaBoost was applied (see Figure 11) to enhance prediction accuracy by focusing on correcting misclassifications and boosting the performance of weaker models (Augustine & & Shukla, 2022).

- ✓

- Base Estimator: Decision Trees with a maximum depth of 1–3 were used as weak learners. This choice balances interpretability and the model’s ability to identify simple decision boundaries.

- ✓

- Number of Estimators: The number of boosting iterations was set to 50, providing a sufficient balance between computation time and model accuracy.

- ✓

- Learning Rate: A learning rate of 0.1 was employed, controlling the contribution of each weak learner to the final model. This parameter was tuned to avoid overfitting while maximizing performance.

- ✓

- Boosting Strategy: The AdaBoost algorithm assigned higher weights to misclassified samples in each iteration, focusing subsequent weak learners on correcting these errors.

- ✓

- The training and testing datasets were the same as those used for other models, with 80% of the data used for training and 20% for testing.

- ✓

- The model’s performance was evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score.

- ✓

- Hyperparameters were optimized using grid search cross-validation with k = 5 folds.

3.5. Interpretations

- Random Forest achieved the highest accuracy of 84.32%, making it the most reliable model for predicting accidents. This model can be used confidently to identify high-risk factors and predict accidents, enabling proactive safety measures on construction sites. The high accuracy of Random Forest suggests that it could serve as a reliable tool for safety management in real construction environments. Safety managers could leverage this model to identify and predict high-risk conditions, enabling them to take preventive measures before accidents occur. So, Random Forest is the most effective tool for predicting and preventing accidents, guiding safety interventions on construction sites based on identified risk factors.

- Decision Tree performed with an accuracy of 81.08%, providing a slightly lower but still strong prediction. Its interpretability makes it valuable for safety managers who need clear, actionable insights to guide safety decisions and protocols. While slightly less accurate, DT offers a more interpretable approach. Safety managers may find it beneficial for developing clear safety guidelines and protocols based on the model’s outputs. The ease of interpreting decision tree splits makes it an excellent tool for training and guiding site supervisors and contractors in accident prevention strategies. So, Decision Tree can be used for designing clear safety guidelines and training programs, thanks to its interpretability.

- AdaBoost showed an accuracy of 66.49%, which is lower than the other two models. While less accurate, it could still be useful for improving model performance by focusing on misclassifications in specific contexts.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbasianjahromi, H.; Aghakarimi, M. (2021). Safety performance prediction and modification strategies for construction projects via machine learning techniques. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management.

- Alexander, D.; Hallowell, M.; Gambatese, J. Precursors of construction fatalities. II: predictive modeling and empirical validation. Journal of construction engineering and management, 2017; 143. [Google Scholar]

- APC, C.; J, G.; TNY, C.; Y, Y.; G, W.; E. ; L. Improving Safety Performance of Construction Workers through Learning from Incidents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 5, 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine, T.; Shukla, S. (2022). Road accident prediction using machine learning approaches. 2nd International Conference on Advance Computing and Innovative Technologies in Engineering (ICACITE).; (pp. 808–811).

- Baker, H.; Hallowell, M.R.; Tixier, A.J.-P. AI-based prediction of independent construction safety outcomes from universal attributes. Automation in Construction 2020, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baradan, S.; Usmen, M.A. Comparative injury and fatality risk analysis of building trades. J. Constr. Eng. Manage 2006, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, M.; Lessa, L.; Vasconcelos, B. Construction accident prevention: A systematic review of machine learning approaches. Work 2023, 145, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.R.; Yang, Y.T. A predictive risk index for safety performance in process industries. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind 2004, 17, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. ; al.; e. Artificial Intelligence Marvelous Approach for Occupational Health and Safety Applications in an Industrial Ventilation Field: A Short-systematic Review. Electronics, 2020; 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Gu, B.; Chin, S.E. Machine Learning Predictive Model Based on National Data for Fatal Accidents of Construction Workers. Automation in Construction 2020, 110, 102974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, D.K.H.; Goh, Y.M. A Poisson model of construction incident occurence. J. Constr. Eng. Manage 2005, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.D.; Phillips, R.A. Exploratory analysis of the safety climate and safety behavior relationship. J. Saf. Res. 2004, 35, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eetvelde, H.; Mendonça, L.; Ley, C.S.; Tischer, T. Machine learning methods in sport injury prediction and prevention: a systematic review. Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics 2021, 8, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.P.; Chen, Y.; Louisa, W. Safety climate in construction industry: A case study in Hong Kong. J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 2006, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargnoli, M.; Lombardi, M. Building Information Modelling (BIM) to Enhance Occupational Safety in Construction Activities: Research Trends Emerging from One Decade of Studies. Buildings 2020, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Gonzalez, V.; Yiu, K.T. ; Cabrera-Guerrero.; G. (2019). The Use of Machine Learning and Big Five Personality Taxonomy to Predict Construction Workers’ Safety Behaviour. Computer Science.

- Gillen, M.; Baltz, D.; Gassel, M.; Kirch, L.; Vaccaro, D. Perceived safety climate, job demands, and coworker support among union and nonunion injured construction workers. J. Saf. Res. 2002, 33, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendon, A.I. Safety climate factors, group differences and safety behavior in road construction. J. Saf. Sci 2001, 39, 157–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowell, M.R.; Gambatese, J.A. Activity-based safety and health risk quantification for formwork construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 2009, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, H.W. (1941). Industrial Accident Prevention: A Scientific Approach. McGraw-Hill.

- Hinze, J. , Hallowell, M.; Baud, K. Construction-safety best practices and relationships to safety performance. J. Constr. Eng. Man. 2013, 04013006, 1943–7862. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S.E. The predictive validity of safety climate. J. Saf, Res. 2007, 511–521.

- Kakhki, F.D.; Freeman, S.A.; Mosher, G.A. Evaluating machine learning performance in predicting injury severity in agribusiness industries. Safety Science 2019, 117, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.U.; Yin, J.; Mustafa, F.S.; Shi, W. Factor assessment of hazardous cargo ship berthing accidents using an ordered logit regression model. Ocean Engineering 2023, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, K.; Gurgun, A. (2021). MACHINE LEARNING APPLICATIONS IN CONSTRUCTION SAFETY LITERATURE. Proceedings of International Structural Engineering and Construction.

- Lee, J.; Yoon, Y.; Oh, T.; Park, S.; Ryu, S. A Study on Data Pre-Processing and Accident Prediction Modelling for Occupational Accident Analysis in the Construction Industry. Journal of Safety Research 2020, 73, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Halpin, D.W. Predictive tool for estimating accident risk. J. Constr. Eng. Manage 2003, 4, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamulkar, S.; Lad, V.H.; Patel, K.A. (5-7 September 2022). Development of a Framework for Selection of a Tunnel Lining Formwork System. Proceedings 38th Annual ARCOM Conference (pp. 359–368). Glasgow, UK: Association of Researchers in Construction Management.

- Rozenfeld, O.; Sacks, R.; Rosenfeld, Y.; Baum, H. Construction Job Safety Analysis. J. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Maiti, J. Machine learning in occupational accident analysis: A review using science mapping approach with citation network analysis. Safety Science 2020, 131, 104900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S. (2020). Occupational Hazards in Building Construction. SCITECH Nepal(10.3126).

- Shuang, Q.; Zhang, Z. (2023). Determining Critical Cause Combination of Fatality Accidents on Construction Sites with Machine Learning Techniques. Buildings.

- Tam, C.M.; Fung, I.W.H. (1998). Effectiveness of safety management strategies on safety performance in Hong Kong. J. Construction Management Economy.

- TD, S.; C, M.-J.; MA, D.; DM, D. Stress, burnout and diminished safety behaviors: An argument for Total Worker Health® approaches in the fire service. J Safety Res. 2020, 75, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedla, A.; Kakhki, F.D.; Jannesari, A. Predictive Modeling for Occupational Safety Outcomes and Days Away from Work Analysis in Mining Operations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarei, E.; Karimi, A.; Habibi, E.; Barkhordari, A.R. Dynamic occupational accidents modeling using dynamic hybrid Bayesian confirmatory factor analysis: An in-depth psychometrics study. Safety Science 2021, 131, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Khattak, A.; Matara, C.M.; Hussain, A.; Farooq, A. (2022). Hybrid feature selection-based machine learning Classification system for the prediction of injury severity in single and multiple-vehicle accidents. PLoS One(10.1371).

- Zhu, R.; Hu, X.; Hou, J.; Li, X. (2021). Application of machine learning techniques for predicting the consequences of construction accidents in China. Process Safety and Environmental Protection.

- Zohar, D. Safety climate in industrial organizations: Theoretical and Applied Implications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Main findings | Authors, Year | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Predictive Model Based on National Data for Fatal Accidents of Construction Workers | Machine learning can effectively predict fatal accidents at construction sites, with month, employment size, age, weekday, and service length being the most influential factors. | Jongko Choi, Bonsung Gu, Sangyoon Chin, Jong-seok Lee (2020) | 10.1016/j.autcon.2019.102974 |

| Application of Machine Learning Techniques for Predicting the Consequences of Construction Accidents in China | Naive Bayes and Logistics regression are the best machine learning algorithms for predicting the severity of construction accidents, with accident type, reporting, and handling being the most critical factors. | Rongchen Zhu, Xiaofeng Hu, Jiaqi Hou, Xin Li (2021) | 10.1016/j.psep.2020.08.006 |

| Predictive Modeling for Occupational Safety Outcomes and Days Away from Work Analysis in Mining Operations | Machine learning techniques, such as decision trees and random forests, can improve mining safety by predicting accident outcomes and days away from work. | Anurag Yedla, Fatemeh Davoudi Kakhki, A. Jannesari (2020) | 10.3390/ijerph17197054 |

| Customized AutoML: An Automated Machine Learning System for Predicting Severity of Construction Accidents | Customized AutoML is an automated machine learning system that accurately predicts construction accident severity for professionals with limited data science knowledge, offering higher scalability, accuracy, and result-oriented insight. | V. Toğan, F. Mostofi, Y. Ayözen, Onur Behzat Tokdemir (2022) | 10.3390/buildings12111933 |

| Safety Performance Prediction and Modification Strategies for Construction Projects Via ML Techniques | The decision tree algorithm effectively predicts safety performance in construction projects, with safety employees, training, rule adherence, and management commitment being key criteria. | H. Abbasianjahromi, Mehdi Aghakarimi (2021) | 10.1108/ecam-04-2021-0303 |

| Component-Based Machine Learning for Performance Prediction in Building Design | This paper presents a component-based machine learning approach for predicting building performance, enabling high prediction quality with errors as low as 3.7% for cooling and 3.9% for heating. | P. Geyer, Sundaravelpandian Singaravel (2018) | 10.1016/J.APENERGY.2018.07.011 |

| Machine Learning Applications in Construction Safety Literature | Machine learning methods, particularly support vector machine and decision tree, are widely used in construction safety literature to predict accident outcomes and identify potential safety risks. | K. Koc, A. Gurgun (2021) | 10.14455/isec.2021.8(1).csa-05 |

| Evaluating Machine Learning Performance in Predicting Injury Severity in Agribusiness Industries | Machine learning techniques can accurately predict injury severity in agribusiness industries using workers’ compensation claims, with a 92-98% accuracy rate. | Fatemeh Davoudi Kakhki, S. Freeman, G. Mosher (2019) | 10.1016/j.autcon.2019.102974 |

| Injury Categories | Direct Causes Categories | Indirect Cuses Categories | Root Causes Categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| - First Aid Case -Medical Treatment Case -Restricted Work Case - Lost Time Injury - Asset Damage |

Unsafe Act (UA) | People Factor (PF) | Management Aspect (MA) |

| - Individual behavior/ attitude - Tools or Equipment Use - Procedures implementation |

- Physical Capabilities - Mental Capabilities - Physiological |

- Resource Management - Leadership - Contractors & Subcontractor Mgt. |

|

| Unsafe Condition (UC) | Execution Factor (EF) | Program System Aspect (PSA) | |

| -Workplace Hazards - Process Hazards - Tools & Equipment Condition - Protective Defenses - Weather conditions |

- Engineering / Design - Project level execution - Communication - Skill & Knowledge - Tools & Equipment Provision |

- Work Standards / Procedures - Risk Evaluation - Task Planning - Training - Inspection and Audit program |

| Injury Type | % of Data related to UA | % of Data related to UC | % of Data related to PF | % of Data related to EF | % of Data related to MA | % of Data related to PSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAC | 35,21 | 27,35 | 12,34 | 7,32 | 9,87 | 7,91 |

| MTC | 30,56 | 28,45 | 14,67 | 11,23 | 8,74 | 6,35 |

| RWC | 22,45 | 29,87 | 13,42 | 17,48 | 9,81 | 6,97 |

| LTI | 16,78 | 25,12 | 15,43 | 21,87 | 14,26 | 6,54 |

| AD | 10,34 | 21,13 | 13,21 | 23,14 | 19,87 | 12,31 |

| Injury Type | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | SD | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UA | ------ | 0.65* | 0.71* | 0.47* | 0.53* | 0.49* | 0.13 | 0.56 |

| UC | 0.65* | ------ | 0.78* | 0.60* | 0.58* | 0.61* | 0.15 | 0.70 |

| PF | 0.71* | 0.78* | ------ | 0.63* | 0.59* | 0.62* | 0.13 | 0.72 |

| EF | 0.47* | 0.60* | 0.63* | ----- | 0.71* | 0.68* | 0.14 | 0.68 |

| MA | 0.53* | 0.58* | 0.59* | 0.71* | ---- | 0.75* | 0.14 | 0.69 |

| PSA | 0.49* | 0.61* | 0.62* | 0.68* | 0.75* | ---- | 0.14 | 0.69 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | SD | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AO | ------ | 0.75* | 0.70* | 0.77* | 0.65* | 0.68* | 0.74* | 0.12 | 0.72 |

| UA | 0.75* | ----- | 0.65* | 0.71* | 0.47* | 0.53* | 0.49* | 0.13 | 0.56 |

| UC | 0.70* | 0.65* | ------ | 0.78* | 0.60* | 0.58* | 0.61* | 0.15 | 0.70 |

| PF | 0.77* | 0.71* | 0.78* | ------ | 0.63* | 0.59* | 0.62* | 0.13 | 0.72 |

| EF | 0.65* | 0.47* | 0.60* | 0.63* | ----- | 0.71* | 0.68* | 0.14 | 0.68 |

| MA | 0.68* | 0.53* | 0.58* | 0.59* | 0.71* | ----- | 0.75* | 0.14 | 0.69 |

| PSA | 0.74* | 0.49* | 0.61* | 0.62* | 0.68* | 0.75* | ---- | 0.14 | 0.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).