1. Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a group of organic compounds widespread in the environment during the incomplete combustion of organic matter such as wood, coal, oil, and gas. This can occur in various settings, including certain industrial processes, motor vehicle emissions, wildfires, tobacco smoke, grilled or charbroiled foods (incomplete combustion of fats and juices). It can be also accumulated in soil due to deposition from the atmosphere, runoff from contaminated sites, or improper disposal of industrial waste. It sediments at the bottom of rivers, lakes, and oceans, where they can persist for long periods, and could be transformed to aliment for fish or plant [

1].

Thus, many PAHs are considered hazardous environmental pollutants of wich exposure to high levels have been associated with potential health risks and are reported to cause skin irritations, allergic reactions, respiratory disorders... The 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA) is a PAH, considered as pure carcinogen substance that induced tumors in rodents [

2,

3,

4]. Prolonged exposure may lead to chronic toxicity, immune suppression, and inflammation, particularly in tissues that directly interact with DMBA or its metabolites. DMBA metabolism occurs in the liver into reactive metabolites by cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP450). DMBA intoxication induce oxidative stress and create abnormal conditions at the cellular and tissue levels, then can result in various adverse effects, including lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, DNA damage… until cancer diseases [

3,

5].

Therefore, to combat the adverse effects caused by everyday exposure to air pollution, which we often live, studies have been conducted to explore natural antioxidants, in order to mitigate the damage that often lead to chronic diseases and cancer [

4,

5,

6]. Several researches have shown that

P.lentiscus (Anacardiaceae) is characterized by important therapeutic properties for millennia [

7,

8]. The traditional culture of this plant was inscribed as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO [

9]. It was mentioned by Avicenna on his book

Canon of Medicine to treat some diseases and was highlighted for its hepato-protective effects [

10]. Nowadays,

P.lenticus has shown antioxidant properties, evidenced by the restoration of hepatic function following sodium arsenite intoxication [

11]. Certain bio-compounds in

P.lenticus have demonstrated protective effects against carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced hepatotoxicity [

6]. The biological activities of this plant are strongly associated with its high phenolic content with antioxidant properties that play a crucial role in maintaining cellular health and reducing the risk of chronic diseases. Notably,

P.lenticus exhibits significant potential in treating various cancers, particularly gastric cancers [

12]. Thus, this plant presents a promising phyto-therapeutic agent due to its richness in bioactive compounds known for their antioxidant and tumor-suppressing effects [

12,15].

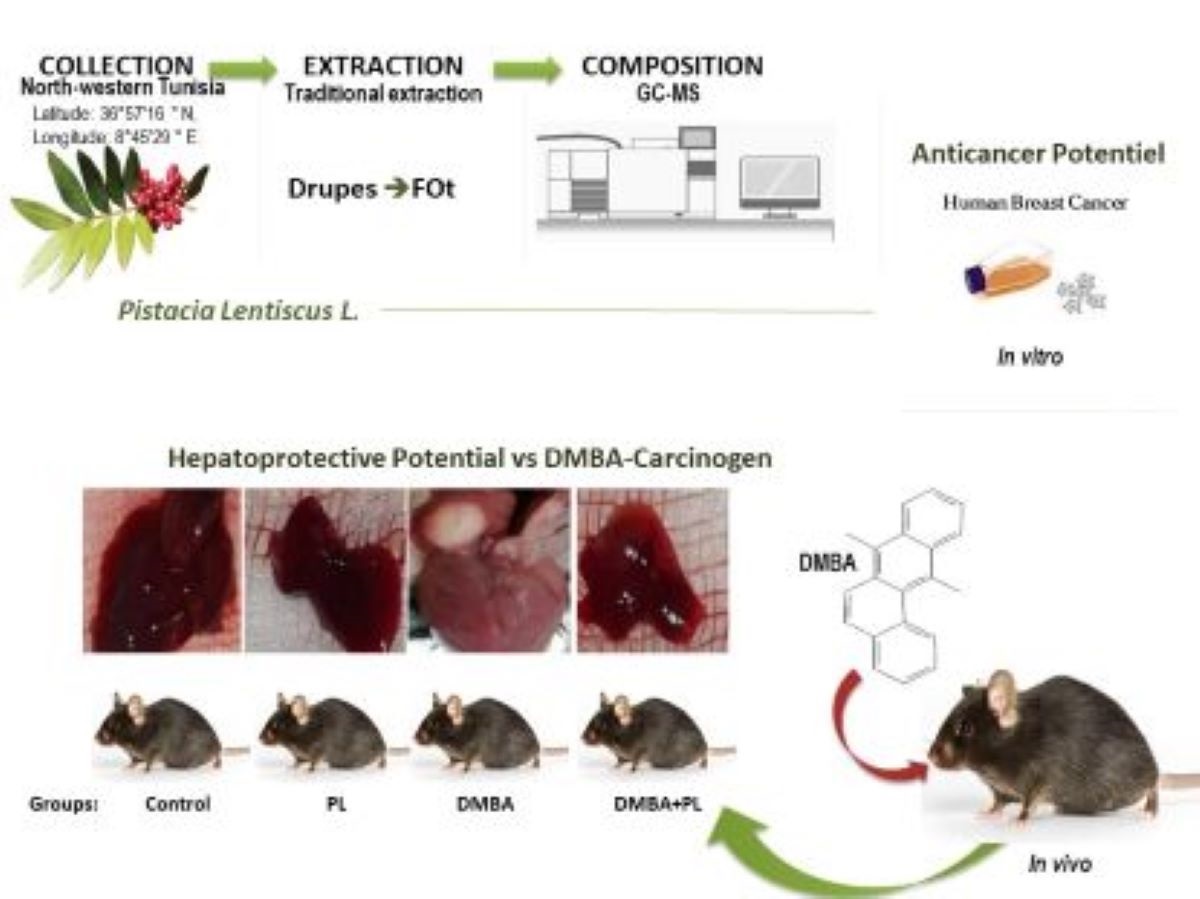

In this study we investigated for the first time the P.lenticus traditionally extracted fixed oil against DMBA-intoxication. We highlited the in vivo antioxidant hepato-protective potential of P.lenticus against DMBA-intoxication on metabolic status and oxidative stress disorders in the liver and kidney of C57BL/6 female mice against the resultant steatosis and inflammation in liver. In vitro, the anti-cancer effect as well as the phytochemical screening of P.lenticus were assessed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Fixed Oil Extraction

Pistacia lentiscus L., 1753 (Sapindales; Anacardiaceae) drupes were harvested from the region of Tabarka in December 2020, District of Jendouba, and Northeast Tunisia (Latitude: 36°57′16”N, Longitude: 8°45′29”E, altitude 108 m; annual rainfall 800-600 mm). The collected plants were identifïed and the certifïed specimen was deposited in the Herbarium of the National Research Institute of Rural Engineering Water and Forestry I.N.G.R.E.F-Tunisia under the reference VS1-PL 2009. The landscape in Tabarka region is not polluted with absence of both domestic and industrial pollution. Fixed oil (FOt) was extracted from freshly collected plants using a traditional method used in the region of Tabarka-Tunisia. Firstly, the harvested P. lenticus fruits were rinsed and stored. The black drupes (500gr) were grinded using a porcelain mortar. The mixture resulting from the grinding was put to kneading and skimming using a wooden spatula in a heated water bath. After that, the shredded material was put in the manual press to separate the liquid phase of the waste. Then it was put to sedimentation for 24-48h and thus oil was easily recovered. The extracted FOt was stored at 8°C, until analysed.

2.2. Cell Lines

The MDA-MB-231 (ATCC® HTB-26™) and MCF-7(ATCC® HTB-22™) human breast cancer cell lines were provided by Pr. José Luis, Institute of Neuro-physiopathology, University of Aix-Marseille, France.

2.3. Animals

C57BL/6-female mice breastfed aged four weeks were purchased from the Pasteur Institute of Tunis-Tunisia. The handling of the animals was in the respect of the code of practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientifïc Purposes and the European Community guidelines-(86/609/EEC). The trial was approved by the Ethical Committee of the National School of Veterinary Medicine of Tunis (approval number: 14/2020/ENMV). Mice were acclimated and housed in polypropylene cages under standard controlled conditions of the animal facility of the National School of Veterinary Medicine-Tunisia: 12/12h light/dark cycle, 20±2°C temperatures, 55%±15% humidity. Food and water were ad-libitum.

2.4. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis (GC-MS)

Chemometric profïling was performed using a GC-MS system (Thermo Fïsher Scientifïc, Walthan, Massachusetts, USA). The extracts were solubilised in methanol (1% v/v) and 1 μL of each sample was injected in a split mode (ratio 15:1) for 75 min, using Agilent GC7890B gas chromatography instrument coupled with an Agilent MS 240 Ion Trap (Agilent, CA, USA). The separation was accomplished in a HP-5MS capillary column (30 m×250 μm, fïlm thickness: 0.25 μm). Helium (99.99 %) was used as carrier gas, released at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min. The initial oven temperature started at 40°C, maintained for 2 min, then increased 5°C/min to 250°C, and held constant at this temperature for 20 min. The injector temperature was set at 280°C. The detection was made in full scan mode for 60 min. Mass spectrometry (MS) operating parameters were as follows: ion source temperature: 200°C, interface temperature: 280°C, ionizing electron energy (EI) mode: 70 eV, scan range: 50–1,000 m/z. Interpretation and identifïcation bio-compounds were performed by comparing mass spectra with those referenced in the NIST 05 database (NIST Mass Spectral Database, PC-Version 5.0, 2005 National Institute of Standardization and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA).

2.5. Experimental Design

The research plan obtained ethical clearance from the National School of Veterinary Medicine of Tunis Ethics Committee (Protocol ID Number: 14/2020/ENMV) and was in compliance with directive 2010/63/EU of animal welfare (Articles 26, 30 and 33) [16]. The experiment was carried out for 28 days in the same conditions for all animals. Mice were divided into 4 groups of 10 animals in each:

Control-group: animals served as control and received equivalent volume of H2O + NaCl (1ml) every day (5/7),

DMBA-group: animals were treated with one dose per week of DMBA (20 mg/kg b.w./week) for 28 days,

DMBA+PL-group: animals received (20 mg/kg b.w.) once a week and daily dose (5/7) of P.lenticus FOt (100 mg/kg b.w.) for 28 days,

PL-group: animals received daily dose (5/7) of P.lenticus FOt (100 mg/kg b.w.) for 28 days, Animals were sacrificed by decapitation according to the American Veterinary Medicine Association Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals at the end of the experiment [17].

2.6. Anthropometric Parameters

During the treatment, weight gain (g), food (g) and water (mL) intake, and blood sugar levels per mouse were taken regularly each two days. Also, blood sugar content was measured every two days through a drop of blood from the codal vein using an Accu-Chek blood meter.

2.7. Plasma Biochemical Parameters

Blood was collected in heparinized tubes for estimation of liver and kidney plasma parameters. A blood centrifugation at 3000 g for 10 min at 4°C was carried out and plasma was harvested.

Lipid profile of total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) and liver and Kidney function parameters of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanines aminotransferases (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (PAL), C-reactive protein (C-RP) (kit-ELISA), urea, creatinine (Crea) were carried out according to a standard method [18] using commercial diagnostic kits (BioSystems S.A., Costa Brava 30, 08030 Barcelona, Spain, certified according to ISO 13485 and ISO 9001).

2.8. Preparation of Homogenate and Estimation of Protein

Animals were sacrificed by decapitation then kidney and liver were quickly removed, washed in 0.9% NaCl and blotted on ash-free paper to weights. 0.4g of each tissue were placed in 4mL (50mM) phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution (pH 7.8), homogenized and centrifuged for 15min at 9000g (4°C). Supernatants were collected and were stored at -80°C for the estimated oxidative stress biomarkers and various enzyme activities below. Total proteins in liver and kidney tissues homogenates were determined according to the biuret method [19] using serum albumin as standard. Briefly, proteins in kidney and liver supernatants constituted with copper a colorful complex measurable at 546 nm wavelength and compared to the blank. Results were expressed as mg of protein.

2.9. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

2.9.1. Lipid Peroxidation (TBARS) Assay

The level of malondialdehyde (MDA) in liver and kidney supernatants was determined as an index of lipid peroxidation according to the double heating method (TBARS) [20]. A BHT-TCA solution (1% BHT dissolved in 20% TCA) was added to supernatant. After centrifuging at 1000g for 5 min at 4°C, the supernatants were mixed with HCl (0.5), TBA-Tris (TBA (120 mM) dissolved in Tris (26 mM)), then heated for 10 min at 80°C. After that the mixture was put directly in ice for cooling to stop the activity of the resulting chromophore. The MDA levels were determined by using an extinction coefficient for the MDA-TBA complex of 1.56 1M− 1 cm− 1 and expressed as nmol/mg protein (nmol/mg Pr).

2.9.2. Sulfhydryl Groups (-SH) Determination

Sulfhydryl groups concentration (-SH) was performed according to the method Ellman et al. (1959). Briefly, liver and kidney homogenates were each mixed with 100mL of EDTA (20mM; pH 8.2). Mixture was vortexed and absorbance was measured at 412 nm (A1). Then, 100mL of DTNB (10mM) was added to the mixture incubated for 15min and the optic density was measured at 412nm (A2). Results were calculated as (A2-A1-B) *1.57mM where B was the blank. The concentration of the sulfhydryl group was expressed as mmol /mg of protein [21].

2.9.3. Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) Determination

Hydrogen peroxide was measured according to a standard colorimetric technique of Kakinuma et al. (1979), using available kit (BioSystems S.A., Costa Brava 30, 08030 Barcelona, Spain, certified according to ISO 13485 and ISO 9001). Briefly, H2O2 forms a red colored quinoa-eradicate after interaction with 4-amino-antipyrine and phenol. Absorbance was redden at 505 nm and results were deducted from a standard calibration curve and expressed as nmol/mg protein [22].

2.10. Enzymes Antioxidant Capacity

The determination of enzymatic antioxidant activities was accomplished by detection of the glutathione peroxidase activity (GPx) performed according to the method of Rotruck et al., (1980). Briefly, 0.2 mL of liver and kidney tissues homogenates were added to 0.2 mL of phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH7.4), 0.2 mL of GSH (4 mM) and 0.4 mL of H2O2 (5 mM). Then, the reaction mixture was incubated for 1 min at 37°C. Centrifugation was carried out for 5 min at 1500 g, after adding 0.5 mL of TCA (5%) to block the reaction. The supernatant (0.2 ml) was collected and mixed with 0.5 ml of DTNB (10 mM) and phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) [22]. The glutathione peroxidase activity was measured at 412 nm wavelength and compared to the blank. Results were expressed as mM/min/mg of protein (UI/mg of protein). The catalase activity CAT was also measured according to a standard method [23] and expressed as µmol H2O2/min/mg of protein. The superoxide dismutase enzyme SOD activity was measured according to a standard method [23] and expressed as Unity mM/min/mg of protein (U SOD/mg of protein).

2.11. Histopathological Analysis

Directly after euthanasia, small pieces of liver and kidney were removed, washed with NaCl (0.9%) and were preserved in a buffered neutral formalin solution (10%). After dehydration with ethanol then xylene, samples were finished in paraffin to be cut into 0.2 µm thick sections. Putting on the slides, the sections were deparaffinized, hydrated (with decreasing concentrations of ethanol) to facilitate their staining with hematoxylin and eosin.

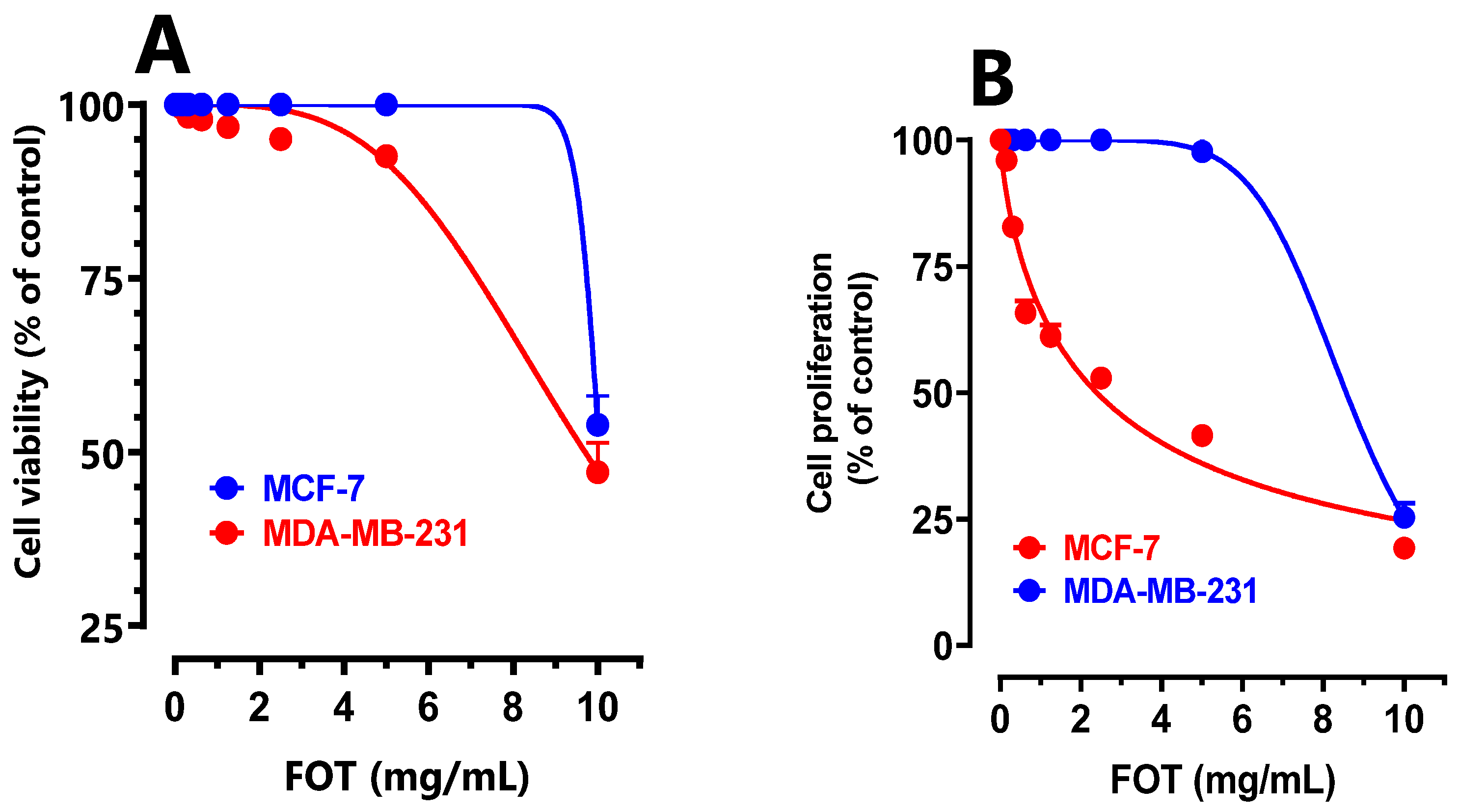

2.12. In Vitro Anticancer Effect

MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cell lines were initially seeded in 96-well culture plates at a concentration of 104 cells/well. Following this seeding, the cells were subjected to incubation either alone or in escalating concentrations of P.lenticus FOt. After incubation periods of 24 hours or 72 hours, cellular viability and proliferation were evaluated through the utilization of the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide tetrazolium reduction colorimetric MTT assay, as described by Mosmann in 1983 [24]. Subsequently, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde, stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and lysed with SDS. Absorbance readings were taken at 560 nm wavelengths using a Multiskan microplate reader (Lab systems, GmbH). The untreated cells (medium) served as the positive control, and the results were presented as percentages of viable cells compared to the non-treated cells used as controls.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

The data was analysed using GraphPad Prism 8.4.2 Software (La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey post hoc test, and was expressed as the mean ± standard error (SEM). All statistical tests were three-tailed and a P value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

4. Discussion

In the present study we investigated the toxicity of DMBA-carcinogen induced oxidative damage in liver tissues on C57BL/6 female mice as well as the hepato-protective potential of P.lenticus FOt bio-compounds on the induced oxidative stress.

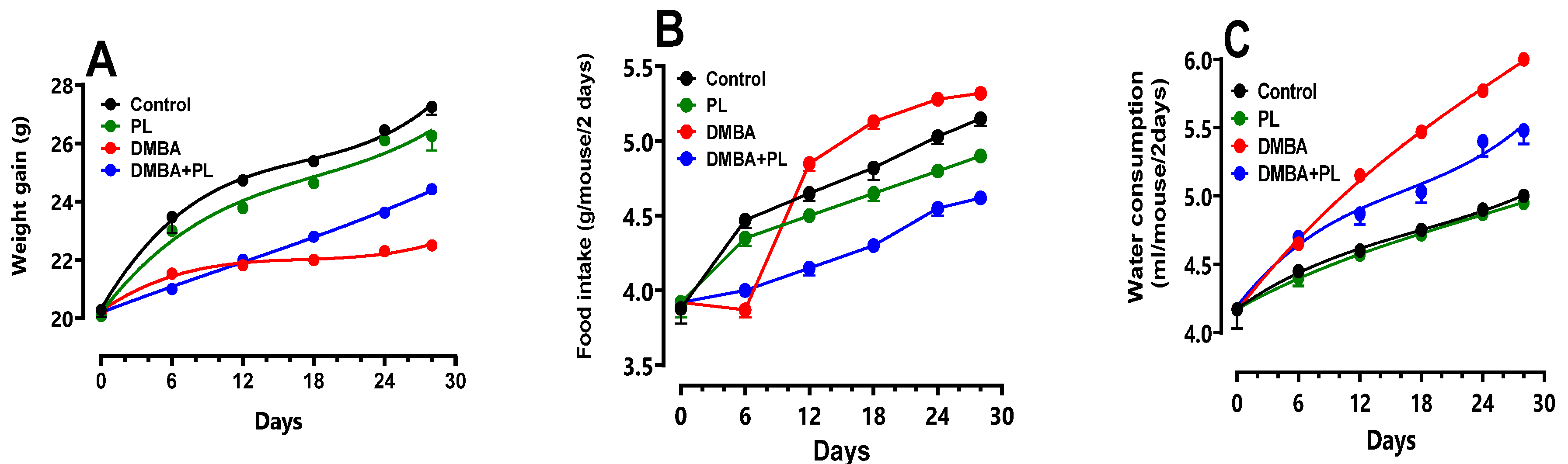

Overall, the DMBA treatment induced an increase in body weight, water intake, blood sugar levels and a decrease in food intake compared to control and co-treated groups (

p<0.05).

P.lenticus extract has a corrective effect in anthropometric parameters of weight, water intake, food intake and blood sugar levels compared to the DMBA group (

Figure 1.) (

p<0.05). Research have proven that despite the increase in appetite, DMBA may induce a catabolic state where the body breaks down muscle to meet energy demands. This can happen if energy expenditure exceeds the amount of energy the body is able to extract from the increased food intake [25]. This disruption can result in increased appetite and altered energy expenditure, contributing to weight loss [25]. It can impair mitochondrial decrease in number and function in tissues, leading to inefficient energy production [26]. Moreover, DMBA can cause inflammation and oxidative stress, which may affect insulin sensitivity and fat metabolism [

4,27]. This chronic inflammation can contribute to muscle wasting (loss of lean mass) and poor nutrient absorption, further promoting weight loss despite higher food intake [28]. Although increased food intake might occur, this impairment can lead to increased energy expenditure due to the inefficiency of energy use, as the body struggles to produce ATP (adenosine triphosphate). DMBA may stimulate pathways that increase thermogenesis (heat production), further increasing energy expenditure. For example, activation of brown adipose tissue can elevate metabolic rate, leading to more calories burned, even during rest [26,29].

In the other hand, the oxidative stress and inflammation caused by DMBA exposure can exacerbate metabolic dysregulation, promoting adiposity and obesity [30]. Our study has proven that DMBA induced an increase in lipid profile, liver function parameters and kidney function parameters (

Table 2) compared to the control group and

P.lentiscus group (

p<0.05). While the same parameters have decreased in the co-treated group compared to DMBA group (

Table 2) (

p<0.05). Some metabolic disorders can be caused by a high-fat diet that can induce oxidative stress in C57BL/6J mice, leading to TG accumulation and hepatic steatosis [30]. It was proven that oxidative stress induced by an intra-peritoneal hepatotoxic injection in C57BL/6 mice significantly increased the serum hepatic transaminase (ALT, myeloperoxidase), cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-17), and lipid peroxidation [31]. One the other hand, previous study have proven that different concentrations of

P.lenticus FO (0.1%-5%) reduced the cell viability of human fat cells [32].

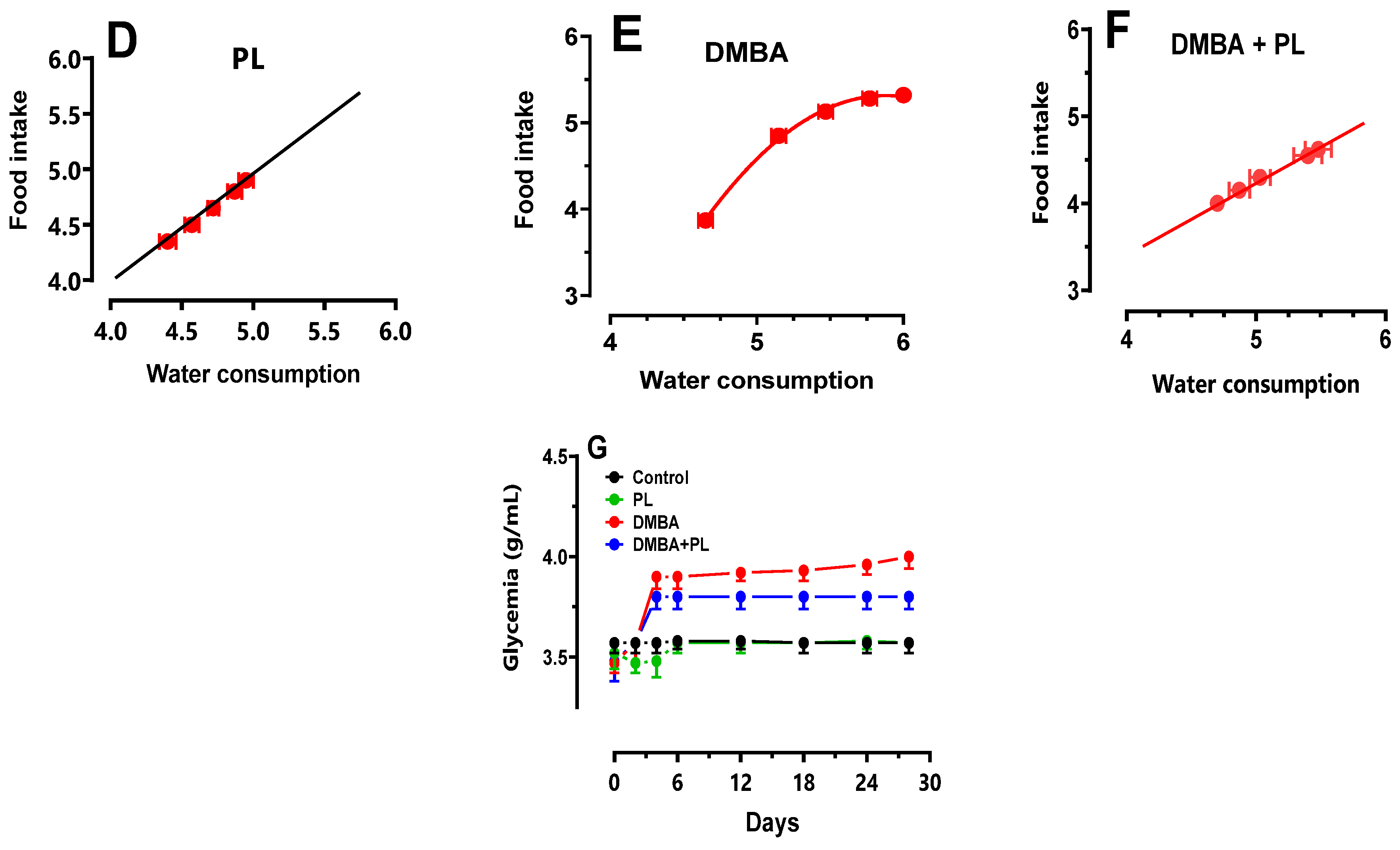

Our result proved that DMBA induced disturbance in oxidative stress biomarkers in liver and kidney tissues (

Figure 2a–c). These results are in accordance with other research studies, proving that DMBA can cause an increase in ROS production, leading to lipid peroxidation and damage to liver cells. Furthermore, it was proven that DMBA significantly modulates cutaneous lipid peroxidation and induced an exhaustion of total antioxidant capacity that consequently inducing skin cancer [14]. Exposure to DMBA may reduce the levels of antioxidants in liver cells, making them more susceptible to oxidative stress and damage. Moreover, oxidative stress can lead to cellular damage and it is implicated in the development of various diseases, including liver and kidney disorders.

Antioxidants are bio-compounds that help protect cells from oxidative stress and damage caused by ROS, which are highly reactive molecules that can harm cellular components like DNA, proteins, and lipids [32]. In this context, the most important result drawn from the present study is the corrector effect of

P.lenticus to prevent oxidative damages in liver. FOt decrease the lipid profile of

PL group compared to the control and in the cotreated group compared to DMBA group (p<0.05) (Figure. 2). Also, it has a potent antioxidant therapeutic effect that increases the antioxidant enzymes and reduces stress biomarkers in liver and kidney tissues. Our results are in agreement with results showing the antioxidant potential of

P.lenticus extracts [

5], as well as those highlighting their hepato-protective effects [

8]. Moreover, it has been proven that this plant has a corrective effect on the retraction of hepatic function after sodium arsenite intoxication [

10].

P.lenticus has relatively mitigated oxidative damage and can exhibit an increase in hepatic antioxidant enzymes [

9].

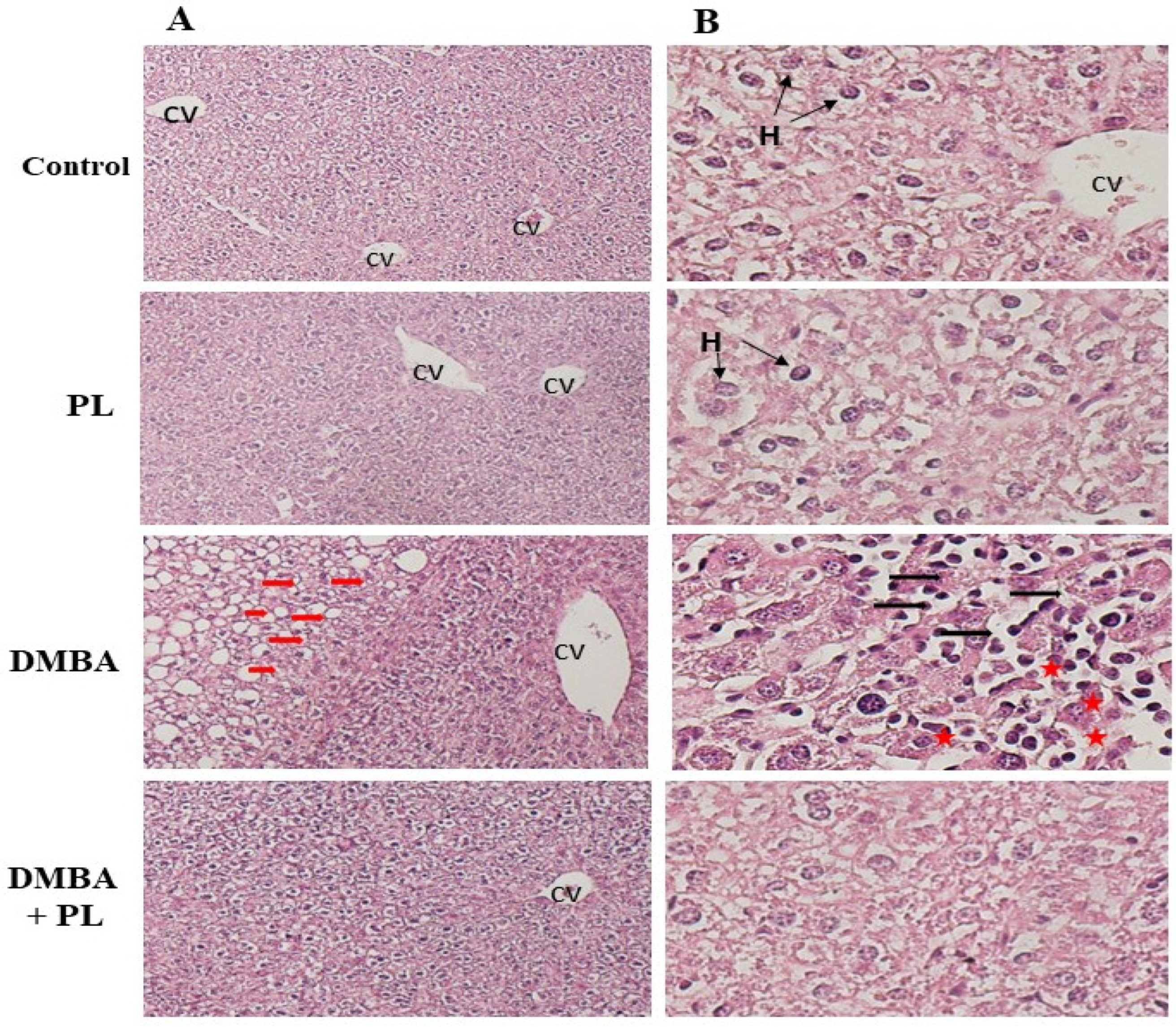

In the present study, our histology data has proven that DMBA treatment induced alteration in hepatocytes cells while no significant funding has been proven in the kidney in the short-term treatment (28 days). Animal models, due to their marked resemblance to the human biological system, have proven to be valuable tools for preclinical investigations. They allow for the evaluation of the efficacy and safety of new therapies in a biological context like that of humans, with interconnected and synergistically functioning biological systems. The use of animals in scientific experiments is strictly governed by the principle of the 3Rs: Refinement, Reduction, Replacement. In line with this principle, we tested the efficacy of this plant on epithelial cells (in primary assays), and then on breast cancer cells (

Figure 5), to replace the animal model, adhering to the 3Rs principles.

Our findings have proven an anti-proliferative potential of

P.lenticus FOt unveiled in a dose dependent manner (

Figure 5). Our results agree with studies reporting that

P.lenticus extracts blocks the differentiation of cancerous of 13 types of human tumour/leukaemia cells, CRC HCT116 cell lines and gastric cancer [

11,14]. This anticancer effect is due to fact that

P.lenticus occurring phytocompounds contribute to various biological activities and health benefits. FOt GC-MS analysish has depicted new chemotypes, mainly: 1H-Indole-3-acetic acid, Benzeneacetic acid, methyl ester, Hexadecanoic acid, 13-octodecenoic acid and Bicyclo(2.2.1)heptan-2-one,1 (

Table 1). These bio-compounds belong to monoterpenes, fatty acid and ester classes. Previous phytochemical studies carried out on

P. lenticus, have proven that FO was rich in alpha-pinene, beta-myrtene, beta-pinene, limonene and beta-karyophylene. FOt is a combination of terpenes where α-pinene (67%) can be the significant compounds. Some combination with myrcene induced can give a potent anticancer effect [

11]. It is also characterized by the presence of flavanol glycosides (flavonoids) (

Table 1) such as: quercetin, myricetin, luteolin, isoflavone genistein, gallic acid and quinic acid [33].

Some medicinal plant can be a potential hepato-protective agent. Artemisia annua leaf extract attenuates hepatic steatosis and inflammation in high-fat diet-fed mice [

5]. This suggests that some bio-compounds enhancement of hepatic antioxidant systems might contribute to its role in preventing DMBA-induced cancer initiation [14,34,35].

Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress caused by the accumulation of fat in liver cells can damage DNA and other cellular components, leading to mutations that promote the development of cancer [

10]. Research have proven that exposure to DMBA led to the activation of an enzyme called sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), which is known to promote lipid synthesis in liver cells. The activation of SREBP-1c resulted in an increase in the expression of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis and lipid accumulation, leading to the development of steatosis. Moreover, DMBA undergoes bioactivation mainly through the CYP1 enzyme family in both liver and extra-hepatic tissues [36]. Importantly, DMBA disrupt the signaling pathways within the hypothalamus, leading to an imbalance in key hormones and neuropeptides [37,38]. The interplay between DMBA-induced oxidative damage and central brain effects highlights the complex mechanisms by which this carcinogen can influence overall body metabolism and weight. DMBA impact on metabolism can be multifaceted, particularly through its effects on the hypothalamic pathways, which regulate energy homeostasis. Moreover, Leptin, secreted by fat cells, typically suppresses appetite. DMBA may induce leptin resistance, reducing the body’s ability to respond to leptin, causing an increase in appetite despite energy stores being sufficient [37]. Also, the same think happens with the hunger hormone: Ghrelin, that stimulates appetite. Where, DMBA may alter its secretion or its effect on the brain, further increasing food intake [38].

There is evidence to suggest that

P.lenticus extract may have a protective effect against oxidative stress leading to steatosis. Supplementation diet with

P.lenticus reduced the accumulation of fat in the liver [39] witch improve liver function. One possible mechanism is through its antioxidant properties:

P.lenticus is rich in antioxidants, such as polyphenols and flavonoids [

6], which can scavenge free radicals and reduce oxidative stress in liver cells [

9,

13,30].

P. lenticus bio-compounds are known have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [

4] to inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which can reduce inflammation in the liver.

Figure 1.

Anthropometric parameters of body weight gain, water intake, food intake and blood sugar levels of C57BL/B6 female mice during the DMBA-treatment period and the protective effect of P.lentiscus Animals were pretreated 28 days per oral (p.o), one dose per week of DMBA (20 mg kg, b.w.) alone for the DMBA group and with addition of daily dose (5/7) of fixed oil of P.lenticus (100 mg kg, b.w. p.o) in the DMBA + PL group. The animals of PL group were treated with daily dose (5/7) of fixed oil of P.lenticus (100 mg kg, b.w. p.o). While those of the control group were treated daily (5/7) with (0.9%) NaCl. Values are given as median and (minimum value- maximum value), p<0.05 (ANOVA test).

Figure 1.

Anthropometric parameters of body weight gain, water intake, food intake and blood sugar levels of C57BL/B6 female mice during the DMBA-treatment period and the protective effect of P.lentiscus Animals were pretreated 28 days per oral (p.o), one dose per week of DMBA (20 mg kg, b.w.) alone for the DMBA group and with addition of daily dose (5/7) of fixed oil of P.lenticus (100 mg kg, b.w. p.o) in the DMBA + PL group. The animals of PL group were treated with daily dose (5/7) of fixed oil of P.lenticus (100 mg kg, b.w. p.o). While those of the control group were treated daily (5/7) with (0.9%) NaCl. Values are given as median and (minimum value- maximum value), p<0.05 (ANOVA test).

Figure 2.

The protective effect of Pistacia lentiscus against the 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene, inducing oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme disorders in liver and kidney tissues of C57Bl/6-female mice. A, B, C: oxidative stress disorders in MDA, -SH and H2O2 parameters, respectively. D, E, F: antioxidant activity of SOD, CAT and GPx, respectively. Animals were pretreated 28 days per oral (p.o), one dose per week of DMBA (20 mg kg, b.w.) alone for the DMBA group and with addition of daily dose (5/7) of fixed oil of PL (100 mg kg, b.w. p.o) in the DMBA + PL group. The PL was treated with daily dose (5/7) of fixed oil of PL (100 mg kg, b.w. p.o). Values are given as median and (minimum value- maximum value), ** p<0.05: compared to the control group, (ANOVA test) and * p<0.05: Compare to DMBA using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis’s test.

Figure 2.

The protective effect of Pistacia lentiscus against the 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene, inducing oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme disorders in liver and kidney tissues of C57Bl/6-female mice. A, B, C: oxidative stress disorders in MDA, -SH and H2O2 parameters, respectively. D, E, F: antioxidant activity of SOD, CAT and GPx, respectively. Animals were pretreated 28 days per oral (p.o), one dose per week of DMBA (20 mg kg, b.w.) alone for the DMBA group and with addition of daily dose (5/7) of fixed oil of PL (100 mg kg, b.w. p.o) in the DMBA + PL group. The PL was treated with daily dose (5/7) of fixed oil of PL (100 mg kg, b.w. p.o). Values are given as median and (minimum value- maximum value), ** p<0.05: compared to the control group, (ANOVA test) and * p<0.05: Compare to DMBA using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis’s test.

Figure 3.

Pistacia lentiscus protective effect against the DMBA induced histo-pathologic alteration in liver and kidney tissues of C57BL/B6 female mice. A: The liver (H&E) Microscopic observation (X10 on the left), B: The liver Microscopic observation (X40 on the between), (n= 10/group) Animals were pretreated 28 days per oral (p.o), one dose per week of DMBA (20 mg kg, b.w.) alone for the DMBA group and with addition of daily dose (5/7) of fixed oil of P.lenticus (100 mg kg, b.w. p.o) in the DMBA + PL group. The PL was treated with daily dose (5/7) of fixed oil of P.lenticus (100 mg kg, b.w. p.o). H: hepatocytes injury, *: dilated sinusoids, PS: the portal space. Black arrows: accumulation of inflammatory and red cells.

Figure 3.

Pistacia lentiscus protective effect against the DMBA induced histo-pathologic alteration in liver and kidney tissues of C57BL/B6 female mice. A: The liver (H&E) Microscopic observation (X10 on the left), B: The liver Microscopic observation (X40 on the between), (n= 10/group) Animals were pretreated 28 days per oral (p.o), one dose per week of DMBA (20 mg kg, b.w.) alone for the DMBA group and with addition of daily dose (5/7) of fixed oil of P.lenticus (100 mg kg, b.w. p.o) in the DMBA + PL group. The PL was treated with daily dose (5/7) of fixed oil of P.lenticus (100 mg kg, b.w. p.o). H: hepatocytes injury, *: dilated sinusoids, PS: the portal space. Black arrows: accumulation of inflammatory and red cells.

Figure 4.

Protective effect of P.lentiscus traditionally extracted fixed oil on DMBA induced histo-pathologic alteration in kidney tissues of C57BL/B6 female mice. Microscopic observation (X40) in the kidney (H&E) of A: the control group, B: PL group treated with fixed oil of P.lenticus 100 mg/kg bw daily dose (5/7), C: DMBA group treated with 20 mg/kg b.w dose per week for 28 days and D: DMBA+ PL group treated with fixed oil of P.lenticus at 100 mg/kg bw daily dose (5/7) dose and DMBA at 20 mg/kg bw dose per week for 28 days. BC: Bowman capsule, S: Bowman space, G: a glomerulus, P: The proximal tubule, S: Bowman space, D: distal tubules.

Figure 4.

Protective effect of P.lentiscus traditionally extracted fixed oil on DMBA induced histo-pathologic alteration in kidney tissues of C57BL/B6 female mice. Microscopic observation (X40) in the kidney (H&E) of A: the control group, B: PL group treated with fixed oil of P.lenticus 100 mg/kg bw daily dose (5/7), C: DMBA group treated with 20 mg/kg b.w dose per week for 28 days and D: DMBA+ PL group treated with fixed oil of P.lenticus at 100 mg/kg bw daily dose (5/7) dose and DMBA at 20 mg/kg bw dose per week for 28 days. BC: Bowman capsule, S: Bowman space, G: a glomerulus, P: The proximal tubule, S: Bowman space, D: distal tubules.

Figure 5.

Effect of P.lentiscus FOT extracted fixed oil on MCF-7 and MDA-MB cell viability (A) and cell proliferation (B).

Figure 5.

Effect of P.lentiscus FOT extracted fixed oil on MCF-7 and MDA-MB cell viability (A) and cell proliferation (B).

Table 1.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry’ fatty acid identification of P.lentiscus traditionally extracted fixed oil.

Table 1.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry’ fatty acid identification of P.lentiscus traditionally extracted fixed oil.

Peaks

N° |

Retention time (min) |

Library identified compound name/ID |

Area (%) |

Chemical class |

Molecular formula |

| 1 |

18.018 |

Bicyclo(2.2.1)heptan-2-one, 1 |

05.2 |

Cyclic monoterpene |

C7H10O |

| 2 |

19.078 |

Benzeneacetic acid |

13.7 |

Monocarboxylic acid |

C8H8O2

|

| 3 |

34.896 |

1H-Indole-3-acetic acid, methyl ester |

53.8 |

Methyl ester |

C11H11NO2

|

| 4 |

36.922 |

Hexadecanoic acid, |

09.9 |

Fatty acidethyl ester |

C16H32O2

|

| 5 |

40.103 |

Methy (l1Z,14Z,17Z)-eicosatrienoate |

11.9 |

Acid methyl ester |

C21H36O2

|

| 6 |

40.211 |

13-octodecenoic acid, methyl |

05.5 |

Monocarboxylic acid |

C28H50O6

|

| |

Monoterpene |

05.2 |

|

|

| |

Fatty acid |

19.2 |

|

|

| |

Ester |

75.6 |

|

|

| |

Total identified |

100% |

|

|

Table 2.

Biochemical parameters of lipid profile, liver and kidney function and blood glucose content.

Table 2.

Biochemical parameters of lipid profile, liver and kidney function and blood glucose content.

| |

Lipid profile |

Liver function |

kidney function |

| |

TC (g/L) |

TG (g/L) |

HDL (g/L) |

LDL (g/L) |

ALT (UI/I) |

AST (UI/I) |

PAL (UI/I) |

C-RP (µg/dL) |

Crea (mg/L) |

Urea (g/L) |

| Group control |

1 ± 0.2 |

1.9 ± 0.1 |

1.1 ± 0.2 |

0.9 ± 0.1 |

98 ± 52 |

196 ± 72 |

212 ± 38 |

0.9 ± 0.6 |

4.9 ± 0.9 |

0.6 ± 0.1 |

| Group P.L |

0.9 ± 0.03 |

1.8 ± 0.5 |

1 ± 0.03 |

0.8 ± 0.05 |

96 ± 62 |

186 ± 82 |

204± 50 |

0.82 ± 0.7 |

4.9 ± 0.5 |

0.6 ± 0.05 |

| Group DMBA |

1.5 ± 0.2a

|

2.2 ± 0.9a

|

1.5 ± 0.2a

|

1.2 ± 0.09a

|

130 ± 88 a

|

230 ± 51 a

|

249 ± 65 a

|

1.5 ± 0.7 a

|

6.2 ± 0.5a

|

0.9 ± 0.09a

|

| Group DMBA+ P.L |

1.2 ± 0.1b |

2 ± 0.8b |

1.2 ± 0.1b |

1 ± 0.1b |

128 ± 73 b |

213 ± 62b |

223 ± 51b |

1.1 ± 0.3 b |

5.9 ± 0.3b |

0.7 ± 0.1b |