Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) has become the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. The risk factors for gastric cancer include Helicobacter pylori infection, age, high salt intake, and low intake of fruits and vegetables.[

1] The traditional chemotherapy regimen, including a combination of platinum, fluoropyrimidine, and paclitaxel with two or three drugs (including trastuzumab as an anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody for HER2 positive cases), is the standard treatment for advanced unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer (AGC). However, the median survival of ACG is still less than 2 years, and new treatment methods need to be introduced. [

2,

3,

4]Immunotherapy is a series of treatment methods that enhance the immune system and combat cancer cells by altering signaling pathways. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have become a new treatment for some cancer patients, including AGC, with good clinical efficacy in some patients. [

5,

6] Although immunotherapy has achieved good efficacy in treating gastric cancer patients, most patients do not respond well to immunotherapy, and immunotherapy resistance has become a huge challenge affecting the effectiveness of immunotherapy. In addition to the joint action of immune cells and immune molecules, the characteristics of tumor cells also play an important role in the intrinsic resistance of immunotherapy, although the exact mechanism is still unclear. [

7] Therefore, clinical researchers need to investigate the potential mechanisms of GC immune resistance and search for new immune therapy resistance biomarkers. In this review, we discussed the mechanisms of immune suppression and drug resistance in GC, predicted biomarkers for immune therapy resistance, and new clinical strategies to enhance immune therapy efficacy.

Immunotherapies for GC

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

Normally, antigen-presenting cells (APCs) can present major histocompatibility complexes (MHC) to T cells. When T cell receptors (TCR) bind to MHC, CD8+T cells are activated and transformed into tumor cell killers. Immunosuppression can protect normal organisms from damage caused by immune reactions, and immune checkpoints play a crucial role in immune suppression as “inhibitors” to prevent long-term inflammation and autoimmunity. Programmed cell death protein 1 and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) are common immune checkpoints in the process of T cell activation. PD-1 is often expressed on the surface of various immune cells. When it binds to its ligand PD-L1, the intercellular inhibitory signaling pathway of T cells is activated, and T cell function is inhibited.[

8,

9,

10] Tumor cells expressing PDL1 can protect them from CD8+T cell-mediated lysis. When PD-L1 is involved, activated T cells can express CD80 as a receptor for transmitting inhibitory signals, leading to peripheral T cell tolerance. Moreover, prolonged exposure to tumor antigens can upregulate negative regulatory factors such as PD-1 in T cells, ultimately leading to their functional failure.[

11,

12,

13]

Immunotherapy that blocks the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a prospective treatment approach for tumors. Clinical trials have shown that nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, can effectively improve overall survival (median OS 5.12 months vs. 4.14 months) and disease progression time (median PFS 1.61 months vs. 1.45 months) in gastric cancer patients compared to placebo. [

14] In the Phase 2 clinical KEYNOTE-059 trial, out of 223 patients who received Pembrolizumab (anti-pd-1 monoclonal antibody) alone and underwent imaging evaluation, 95 cases (42.6%) showed a reduction in tumor volume, with a median duration of remission of 8.4 months. [

15] In another clinical trial, compared with chemotherapy, the use of single agent avilumab (anti-pd-1 monoclonal antibody) in third line treatment for GC patients did not lead to significant improvement in OS (median OS 4.6 months vs 5.0 months) or PFS (median PFS 1.4 months vs 2.0 months). However, in the avelumab group, only 90 cases (48.9%) experienced any level of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), while in the chemotherapy group, 131 cases (74.0%) of patients experienced TRAEs. The avilumab shows more controllable safety than chemotherapy.[

16] The combination of anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody and chemotherapy may achieve better therapeutic effects and may become a new standard treatment for GC patients. In the Ib/II phase clinical trial NCT02915432, toripalimab (anti-pd-1 monoclonal antibody) combined with chemotherapy achieved better efficacy than monoclonal antibody alone. The objective response rate (median ORR 66.7% vs 12.1%) and disease progression time (median PFS 5.8 months vs 1.9 months) of the combination therapy group were significantly better than those of the monotherapy group.[

17] A large number of clinical trials have demonstrated the superiority of PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors, which may have better efficacy and fewer side effects than traditional chemotherapy. PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors may become a new prospective treatment option for GC patients.

Chimeric Antigen Receptor -T Cell Therapy (CAR-T) Primary

Tumor cells have high immunogenicity, and the specific expression of tumor associated antigens (TAA) is key to activating anti-tumor immune responses. T cells can recognize tumor cells and attack them based on TAA molecules. CAR-T therapy is an immunotherapy based on this mechanism. . Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) is the core of CAR-T, which enables T cells to recognize tumor antigens in a manner independent of histocompatibility complexes, enabling them to recognize a wider range of target antigens. CAR consists of four main components: extracellular target antigen binding domain, hinge region, transmembrane domain, and one or more intracellular signaling domains. The antigen binding domain is the part of CAR that confers target antigen specificity, with certain fragments targeting the extracellular surface TAA. The main function of the transmembrane domain is to anchor CAR onto the T cell membrane, while the transmembrane domain can also affect the expression level and stability of CAR.[

18,

19]

CAR-T therapy has achieved good results in the treatment of hematological malignancies, such as B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), B-cell non Hodgkin lymphoma (BNHL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).[

20] In recent years, CAR-T immunotherapy has also been explored as a method for treating solid tumors, including GC. According to previous studies, CLDN18.2 is a gastric specific subtype of claudin-18. Clinical data shows that the overall objective response rate of CLDN18.2 specific human mouse chimeric monoclonal antibody IMAB362 to gastric cancer patients is about 10%, and it has no significant toxicity to normal tissues other than the stomach. Therefore, CLDN18.2 may be a promising therapeutic target for treating gastric cancer and other CLDN18.2-positive tumors.[

21,

22] Jiang et al. successfully developed humanized CLDN18.2 specific HU8E5 and HU8E5-2i single chain fragment variables (scFv). CLDN18.2 specific CAR-T cells were developed using HU8E5 or HU8E5-2i scFv as targeting fragments. HU8E5-2I-28Z CAR-T cells can partially or completely eliminate tumors in the CLDN18.2 positive gastric cancer PDX model (P<0.001), persist in the body and effectively infiltrate tumor tissues, without significant harmful effects on normal organs.[

23] Although many preclinical trials have shown that CAR-T cells are prospective candidate therapies for treating GC, CAR-T cell therapy has not yet been applied in clinical trials for GC patients. More breakthroughs are needed in the clinical translation of CAR-T cell therapy.

Tumor Vaccines

Protective vaccination has been proven to be one of the most effective health measures for preventing infectious diseases, while therapeutic vaccination for cancer is clearly more challenging. Cancer vaccines are designed for antigens that can trigger selective immune responses against cancer cells rather than normal cells. At present, therapeutic vaccines for tumors mainly target differentiation antigens, cancer testis antigens, and/or overexpressed antigens, but their clinical application is limited.[

24] Most cancers have neoantigen specific T cells, which provide specific and highly immunogenic targets for vaccine administration due to somatic mutations.[

25] The most common antigens, including New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma 1 (NY-ESO-1), TTK protein kinase (TTK), testicular cancer antigen 2 (CTAG2), and melanoma associated antigen a (MAGE-A) (42), have been confirmed to be widely present in gastric cancer.[

26] The CD8+T cells stimulated by these antigens can specifically react with the antigen, so these CD8+T cells can specifically lyse certain tumor cells. Several tumor vaccines have been used in clinical trials. MAGE-3 peptide is a tumor vaccine based on the MAGE gene. In experiments, it was used to treat 12 cases of advanced gastrointestinal cancer, including 6 cases of gastric cancer, without any toxic side effects. Ultimately, four patients observed peptide specific CTL responses after vaccination. The physical condition of four patients has improved. The tumor markers of seven patients decreased. In addition, mild tumor regression confirmed by imaging studies was observed in the three patients. These results indicate that vaccination with MAGE-3 peptide may be a safe and promising method for treating gastrointestinal cancer.[

27] In Liu et al.‘s study, PNVAC (a personalized neoantigen vaccine without complex chemical attachments) was found to effectively prolong disease-free survival in gastric cancer patients. PNVAC can induce CD4+and CD8+T cell responses as well as memory T cells for antigen experiences. Moreover, this immune response is persistent and still evident one year after vaccination.[

28]

Potential Mechanisms of Resistance to Immunotherapy in GC

Immunotherapy induced anti-tumor response has been successfully used in clinical treatment of GC. With the widespread use of immunotherapy, more and more GC patients have an extended survival period. However, after a period of immunotherapy, some patients may experience tumor recurrence, volume growth, and distant metastasis. The exact mechanism by which this situation occurs is not yet clear. Traditionally, it is believed that it is often associated with downregulation of tumor antigens, enhancement of escape mutants, interferon - γ (IFN - γ) signaling, and abnormal recognition by T cells.[

29,

30]

Tumor-Intrinsic Resistance to Immunotherapy in GC

The main method for tumor cells to evade immune response is to upregulate immune checkpoint molecules and downregulate tumor antigens. Immune checkpoints include PD-1, PD-2, CTLA-4, etc., which are usually expressed on the surface of immune cells. These molecules are key molecules that prevent immune cells from causing inflammation, destruction, and autoimmunity. They can block signal transduction within T cells. Tumor cells may highly express these checkpoint proteins to protect themselves from being lysed by cytotoxic T lymphocytes, thereby avoiding death.[

31] Multiple studies have shown that PD-I and CTLA-4 molecules are highly expressed on the surface of GC cells.[

32,

33]The expression levels of immune checkpoints may vary in different pathological subtypes of gastric cancer.[

34]Tumor cells can even suppress T cell immunity by secreting PD-L1 through exosomes, which is difficult to recover through ICI.[

35]Therefore, determining a reliable immunotherapy targeting specific immune checkpoints remains a daunting challenge.

Certain factors secreted by tumor cells can upregulate immune checkpoints in various ways. GC cells can also secrete cytokines and growth factors to promote tumor growth and reduce anti-tumor immune responses. Transforming growth factor - β (TGF - β) is a factor secreted by tumor cells that can regulate the proportion of several types of immune cells and play an important role in immune tolerance [

32]. It is crucial for enhancing immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment (TME). TGF - β can directly inhibit the cytotoxicity of T cells and NK cells, as well as the antigen presentation ability of DC cells. In addition, TGF - β can also block the differentiation of primitive T cells into effector T cells and promote the transformation of macrophages into M2 phenotype.[

36,

37] The most significant and characteristic T cell response in cancer is mediated by Th1 subpopulation cells, and immature T cells cultured with TGF - β cannot differentiate into Th1 phenotype. On the contrary, T cells in mice lacking TGF - β specificity exhibit a strong Th1 phenotype.[

38] Meanwhile, TGF - β can also inhibit the anti-inflammatory response mediated by transcription factor NF kB. MYD88 is an adapter protein for all Toll like receptors (TLR) except TLR3, used to activate NF kB signaling. TGF - β can promote the degradation of MYD88. SMAD6 induces polyubiquitination of MYD88 by recruiting the ubiquitin ligase SMURF1/2 in macrophages stimulated by TGF - β.[

39] [

40]Therefore, TME rich in TGF - β may promote immune evasion by inhibiting the inflammatory function of macrophages. Other cytokines, such as Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) secreted by GC cells, can promote the upregulation of PD-1 immune checkpoint in gastric cancer by inducing immunosuppressive macrophages, further leading to tumor immune escape.[

40]

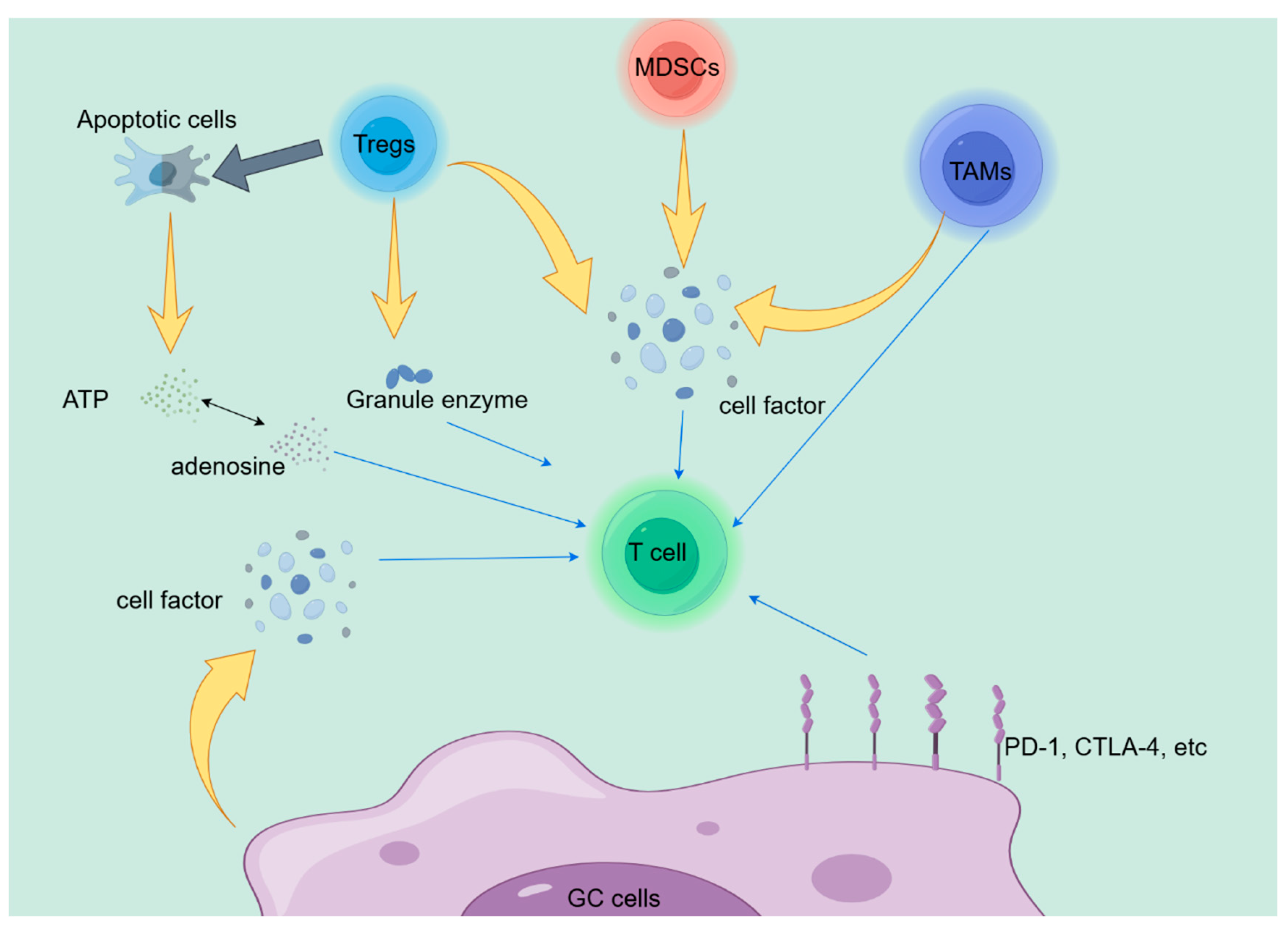

Tumor-Extrinsic Resistance to Immunotherapy in GC

The various cell-cell interactions in the tumor microenvironment (TME) are an important pathway leading to immune suppression, and the classical PD-L1/PD-1 signaling between tumor cells and CD8+T cells has been confirmed in different cancers. However, in addition to tumor cells, many inhibitory cells can also suppress the cytotoxicity of T cells, including regulatory T cells (Tregs), bone marrow-derived inhibitory cells (MDSCs), and tumor associated macrophages (TAMs). Improper differentiation of these cell subpopulations, upregulation of immunosuppressive related proteins, typically creates an anti-inflammatory environment, leading to CD8+T cell dysfunction and immune resistance.[

41,

42,

43,

44] Tregs exert anti-tumor functions by inhibiting T cells in various ways. Firstly, Tregs can secrete cytokines such as IL-10, TGF-b, and IL-35, which inhibit effector T cell activity and promote Treg proliferation.[

45,

46] At the same time, apoptotic Treg cells release a large amount of ATP through CD39 and CD73 and convert it into adenosine, which exerts anti-inflammatory effects through adenosine.[

47] Finally, studies have shown that Tregs can also use granzyme and perforin to kill T cells.[

48] MDSCs are a heterogeneous group of pathologically activated immature cells that are a major component of the immunosuppressive network. On the one hand, MDSCs can suppress the immune function of T cells by overexpressing ARG1, iNOS, and ROS.[

49,

50,

51] On the other hand, MDSCs can prevent the progression of T cell cycle, reduce T cell generation, and ultimately suppress tumor immunity.[

52] Tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) are key immune components of TME and can be classified into M1 (pro-inflammatory) and M2 (anti-inflammatory) phenotypes based on their polarization. TAMs can impair T cell function in various ways, including limiting infiltration, blocking proliferation and activation, and inhibiting cell toxicity. For example, IL10 produced by TAMs can reduce CD8 protein levels and impair TCR signaling, further leading to immune suppression.[

53] TAM also highly expresses Tim3, Tim4, PD-1, and PD-L1, which can inhibit macrophage phagocytosis, inflammasome activation, and production of effector cytokines, ultimately leading to tumor immune suppression.[

54,

55,

56]

The cytokines enriched in TME are another important pathway that interferes with the efficacy of tumor immunotherapy. Various studies have demonstrated that certain cytokines, such as TGF - β, DKK1, IL-4, and IL-10, play important roles in disrupting CD8+T cell function. Most cells in TME can produce TGF - β, including cancer cells, fibroblasts, TAMs, Tregs, and even platelets.[

36] TGF - β can affect tumor immunity through multiple pathways. For example, the TGF - β/SMAD pathway reduces the cytotoxicity of T lymphocytes by decreasing the expression of perforin, granzyme A, granzyme B, and IFN-g.[

57]Shi et al. found that high expression of DKK1 can mediate the PI3K-AKT axis to induce polarization of macrophages in the tumor microenvironment towards the M2 phenotype, thereby promoting tumor immune escape and hindering anti-PD-1 therapy. In the study, by establishing a gastric cancer model and blocking DKK1, it was found that the infiltration of NK cells and CD8+T cells increased in the experimental group, while M2 macrophages were significantly reduced. And by blocking DKK1, tumor microenvironment reprogramming was enhanced, enhancing the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy in the same gene gastric cancer model.[

40]IL-4 and IL-10 are typical cytokines expressed by helper T lymphocytes, involved in infections and autoimmune diseases. Moreover, they are highly enriched in various cells of gastric cancer TME.[

58,

59] IL-4 and IL-10 can suppress the function of CD8+tumor infiltrating T cells by recruiting immunosuppressive components such as Tregs, M2 tam, and MDSCs. For example, studies have shown that the NR_109/FUBP1/c-Myc axis can mediate the secretion of IL-4, thereby affecting M2 like TAM polarization and leading to immune suppression in gastric cancer patients. [

60] However, recent reports suggest that IL-4 and IL-10 can directly or indirectly enhance the anti-tumor effect of CD8+T cells in the gastric cancer tumor microenvironment.[

59,

61,

62]

As shown in

Figure 1, we have discussed many potential mechanisms related to immune therapy resistance in the previous text.However, elucidating the immunotherapy resistance of GC remains highly challenging. Therefore, a large amount of clinical and basic experimental data is necessary for understanding and overcoming immunotherapy resistance, and providing more clinical benefits to patients.

Potential Biomarkers of GC Immunotherapy

The occurrence and progression of tumors in patients mainly depend on the interaction of various cells in the tumor microenvironment, such as the proliferation and invasion ability of tumor cells, the interaction of immune cells induced by regulatory factors produced by various cells in the tumor microenvironment, etc. Meanwhile, the immune resistance of GC is believed to be the result of specific molecular abnormalities, such as stimulating and inhibitory factors, ultimately leading to abnormal T cell function. Therefore, it is particularly necessary to identify reliable biomarkers before immunotherapy to predict the prognosis of GC patients.

Immune Checkpoint Proteins

PD-L1, also known as CD274, is a transmembrane protein expressed in GC cells. PD-1 is usually expressed on the surface of T cells as a receptor for PD-L1. When it binds to PD-L1, it can inhibit the anti-tumor effect of T cells. Mainstream, the binding of PD-L1 and PD-1 is still considered the main mechanism of anti-tumor immune evasion. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can inhibit their binding, helping T cells recognize and kill GC cells. Most researchers believe that the expression of PD-1/PD-L1 can predict the prognosis of G immunotherapy. Research has shown that high levels of PD-L1 can be detected in GC cells, and PD-L1 levels are significantly correlated with survival benefits.[

63] The results of the COMPASSION-04 clinical trial showed that the efficacy of Cadonilimab combined with chemotherapy in the treatment of HER2 negative gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma was correlated with the expression level of PD-L1. The median OS of patients with PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 was 20.32 months; In patients with PD-L1 CPS<1, the median OS was 17.64 months.[

64] In another study, it was found that the PD-L1 CPS<10 Pembrolizumab monotherapy group had no better efficacy than the chemotherapy group, while in patients with CPS ≥ 10, the Pembrolizumab treatment group had a longer overall survival rate than the chemotherapy group.[

65] Meanwhile, Shitara et al.‘s study found that compared to paclitaxel, Pembrolizumab did not significantly improve the overall survival rate of advanced gastric cancer or gastroesophageal junction cancer with high PD-L expression in second-line treatment.[

66] These controversial research findings may be due to the heterogeneity of PD-L1 in different samples, different detection methods, and complex interactions between anti-tumor immune responses and GC cells. In addition, the treatment of GC patients may significantly affect the outcomes. This suggests that the expression of PD-L1 may be a positive biomarker for GC patients receiving immunotherapy, and the prognostic value of PD-L1 in EC needs further clinical research to confirm.

Other potential prognostic biomarkers, such as CTLA-4, IDO1, IL-8, IL-10, TGF - β, have been reported to be associated with the therapeutic response and tumor staging of GC. [

67,

68] However, there is currently insufficient research on their correlation with the prognosis of GC immunotherapy, therefore further studies and extensive clinical trials are needed to explore more biomarkers with prognostic value.

Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) have shown great value in evaluating the prognosis of various solid tumors, including gastrointestinal tumors[

69] The efficacy of immunotherapy in anti-tumor treatment largely depends on the degree of infiltration of immune cells such as T cells into tumor tissue. The upregulation of CD8+T cells and CD4+T cells in the tumor microenvironment of GC patients is significantly correlated with delayed survival and better prognosis.[

70] Due to the crucial role of TILs in the tumor microenvironment in immune response, researchers have proposed a concept called “Immunoscore” which combines tumor TNM staging and tumor lymphocyte infiltration as basic parameters for cancer classification. Research has found that cancer patients with high “Immunoscore” are often associated with good clinical outcomes from several different immune therapies.[

71] However, further research is needed to understand the specific mechanism by which “Immunoscore” participates in GC tumor immunotherapy

Non-Coding RNA

Non-coding RNA refers to a type of RNA that can perform its biological functions at the RNA level, although it cannot be translated into proteins. Non-coding RNA includes various RNAs such as rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, snoRNA, and microRNA. MicroRNA (miRNA) is a non-coding RNA containing 20-24 nucleotides. After gene expression, they bind to the 3’UTR region of the target gene in complementary nucleotide sequences, degrading mRNA or inhibiting translation into proteins.[

72] Therefore, miRNAs play a role as oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes in tumors by regulating the expression of target genes, and participate in various aspects such as cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and angiogenesis.[

73] Multiple studies have shown that miRNAs are widely involved in the immune therapy resistance of tumors. For example, miR-BART5-5p directly targets PIAS3 and enhances PD-L1 through miR-BART5/PIAS3/pSTAT3/PD-L1 axis control. This helps to resist cell apoptosis, tumor cell proliferation, invasion and migration, immune escape, immune therapy resistance, further promoting the progression of gastric cancer and worsening clinical outcomes.[

74] Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are endogenous non coding RNAs derived from a single exon or multiple exons, present in the cytoplasm of various biological cells. These circular RNAs have a conserved, covalently fixed closed loop structure that is more difficult to degrade than linear RNAs with a 5 ‘cap and 3’ poly (A) tail.[

75,

76,

77] Tumor occurrence, cancer progression, and immune therapy resistance are usually regulated by circular RNAs. For example, the cancer cell-derived extracellular vesicle circUSP7 induces CD8+T cell dysfunction and induces anti-PD-1 resistance in non-small cell lung cancer by regulating the miR-934/SHP2 axis.[

78]

Although a large number of studies have shown that non coding RNAs are associated with immune resistance in tumor therapy, the selection of non-coding RNAs as biomarkers for GC immunotherapy is still uncertain due to the abundance of non-coding RNAs from various sources in the tumor microenvironment, and further research is needed.

Strategies to Enhance the Efficacy of Immunotherapy

Chemotherapy Combined with Immunotherapy

The use of chemotherapy is often accompanied by severe bone marrow suppression and leukopenia, therefore chemotherapy is considered to suppress the efficacy of immunotherapy.[

79] But more and more recent studies have shown that chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy has a significant synergistic effect. In a clinical trial, neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy was used for the first three cycles of surgical resection of gastric cancer tissue. Sintilimab (3 mg/kg in cases with less than 60 kg or 200 mg on the first day in cases with ≥ 60 kg) was combined with CapeOx (oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 combined with capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 twice a day) for D1-D14, with a 21 day interval between cycles. After surgical resection, CapeOx was used for three cycles of adjuvant therapy at the same dose. Sintilimab combined with CapeOx showed superior pathological complete response (PCR) rates and good safety in neoadjuvant therapy.[

80] This synergistic effect may stem from the fact that chemotherapy can induce immunogenic cell death (ICD) in tumors, followed by widespread innate and adaptive immune responses. According to reports, classic chemotherapy regimens FOLFOX or FOLFIRI can induce damage associated molecular models (DAMPs) in mouse and human tumor cell lines. DAMPs are strong signals that promote DC maturation and tumor antigen presentation, which can further lead to tumor ICD and subsequently enhanced T cell anti-tumor response.[

81,

82]

Immunoadjuvants

Immune adjuvant is a type of auxiliary substance that can enhance the body’s immune response to antigens or change the type of immune response when injected together or pre injected into the body. Currently clinically proven immune adjuvants are typically highly involved in activating humoral immunity rather than cellular immunity. Therefore, immune adjuvants are currently commonly used in various vaccines to prevent viral and bacterial infections.[

83] Fortunately, research has found that manganese salts can promote immune response by promoting antigen uptake, antigen presentation, and germinal center formation, and may be an adjuvant that enhances the efficacy of immunotherapy. In the experiment, the manganese salt combined with immunotherapy group significantly inhibited the growth of melanoma tumors implanted subcutaneously in mice, and the survival rate was significantly improved.[

84] Although there is currently no research indicating that immune adjuvants such as manganese salts can counteract immune suppression in GC patients, immune adjuvants still have great potential in enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapy for gastric cancer.

Antiangiogenics

Most solid tumors have the characteristic of vascular abnormalities, which often promote the progression and treatment resistance of tumors such as gastric cancer. [

85,

86,

87]These abnormalities are caused by elevated levels of angiogenic factors, such as VEGF and angiopoietin 2 (ANG2); The use of drugs targeting these molecules can promote the normalization of abnormal tumor vascular systems, thereby improving therapeutic efficacy. Clinical trials have shown that anlotinib (an anti angiogenic drug targeting VEGF) can significantly inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and proliferation of gastric cancer cells. Moreover, anlotinib can inhibit the expression of PD-L1 and achieve better therapeutic effects when used in combination with PD-1 antibodies.[

88] Anti vascular therapy is often used as a second-line treatment for gastric cancer, so it is crucial to determine whether its combination with immunotherapy can have a synergistic effect.

Tumor Microenvironment

Various types of cells in the tumor microenvironment directly or indirectly affect other cells in the tumor microenvironment, playing an important role in the formation of tumor immunotherapy resistance. Therefore, targeting TME may be a potential method to enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy. High levels of regulatory T cells (Tregs) are associated with poor clinical prognosis in some types of solid tumors, including gastric cancer.[

89,

90] For example, Tregs with high expression of CCR4 play an important role in suppressing anti-tumor immune responses in peripheral blood and tumor microenvironment.[

91] In a clinical study, researchers found that the combination therapy of Mogamulizumab (anti-CCR4 antibody) and nivolumab (anti-PD-1 antibody) can effectively reduce effector Tregs in tumor infiltrating lymphocytes of patients with solid tumors, including gastric cancer, increase CD8+T cells, and ultimately enhance immune response. [

92]

DNA Damage Response and Repair

Tumor tissue often exhibits genomic instability, and tumor cells often have significant defects in DNA damage response and repair (DDR). [

93] The DDR pathway affects the resistance and sensitivity of tumor cells to radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. In theory, the combination therapy of ICI and DNA damage therapy can reduce treatment resistance and improve the efficacy of ICI treatment. Drugs targeting the DDR pathway have been used in anti-cancer therapy. For example, Ceralasertib (AZD6738) is an effective selective ATR pathway inhibitor that can inhibit the replication stress response induced by DNA damage in the s-phase of the tumor cell cycle and promote DDR. The combination of ceralasertib and durvalumab (anti-PD-L1 antibody) can significantly prolong the progression free survival and overall survival of melanoma patients.[

94] Although there is limited research on the combination of targeted DDR therapy and immunotherapy for gastric cancer, we are confident that this is a strategy with great potential to enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy.

Conclusions

In this review, we describe the current status of GC immunotherapy. We also discussed the possible mechanisms of drug resistance in patients undergoing immunotherapy and described potential biomarkers with prognostic value for GC patients receiving immunotherapy. At the same time, we also introduced some auxiliary methods that may enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy. In clinical practice, immunotherapy is often used as a salvage treatment for patients with advanced GC. More clinical trials are needed to verify whether immunotherapy can achieve better results in early application and find strategies to enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy. Due to the differences in immune environments, it is necessary to study the possible mechanisms of immune suppression in GC in order to develop precise targeted therapy methods, overcome immune therapy resistance in GC, and improve the prognosis of GC patients.

Cover Letter

Gastric cancer has become one of the most common tumors in the world today. With the use of traditional treatment methods such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the survival period of GC patients has been extended. However, some patients experience tumor progression after a period of standardized treatment. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and other immune therapies have shown good clinical efficacy in some patients. Immunosuppression greatly weakens the persistence and effectiveness of immunotherapy. Due to the heterogeneity of the immune microenvironment and the highly diverse tumor characteristics of different individuals, the exact mechanism of GC immunotherapy resistance is still unclear. This article reviews the research progress on immune therapy resistance, with a focus on the current immune therapy methods and the potential mechanisms of immune suppression and resistance in immune therapy. Additionally, we discuss prospective potential biomarkers for predicting immune efficacy and new methods for enhancing efficacy to provide a clear insight into GC immunotherapy.

Funding

The research receive no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The Figure 1 is drawn by Figdraw.

References

- Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NCT, Lordick F. Gastric cancer. The Lancet. 2020;396:635-48.

- Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, Iveson T, Nicolson M, Coxon F, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358:36-46. [CrossRef]

- Joshi SS, Badgwell BD. Current treatment and recent progress in gastric cancer. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2021;71:264-79. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Yu W, Xie F, Luo H, Liu Z, Lv W, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy with immune checkpoint blockade, antiangiogenesis, and chemotherapy for locally advanced gastric cancer. Nature Communications. 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;375:1823-33. [CrossRef]

- Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:2443-54. [CrossRef]

- Rieth J, Subramanian S. Mechanisms of Intrinsic Tumor Resistance to Immunotherapy. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018;19.

- Li B, Chan HL, Chen P. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Basics and Challenges. Current medicinal chemistry. 2019;26:3009-25.

- Tang Q, Chen Y, Li X, Long S, Shi Y, Yu Y, et al. The role of PD-1/PD-L1 and application of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in human cancers. Frontiers in immunology. 2022;13:964442.

- Yi M, Jiao D, Xu H, Liu Q, Zhao W, Han X, et al. Biomarkers for predicting efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Molecular cancer. 2018;17:129.

- Park JJ, Omiya R, Matsumura Y, Sakoda Y, Kuramasu A, Augustine MM, et al. B7-H1/CD80 interaction is required for the induction and maintenance of peripheral T-cell tolerance. Blood. 2010;116:1291-8.

- Chen DS, Mellman I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature. 2017;541:321-30.

- Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Science translational medicine. 2016;8:328rv4.

- Kang YK, Boku N, Satoh T, Ryu MH, Chao Y, Kato K, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England). 2017;390:2461-71.

- Fuchs CS, Doi T, Jang RW, Muro K, Satoh T, Machado M, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Pembrolizumab Monotherapy in Patients With Previously Treated Advanced Gastric and Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer: Phase 2 Clinical KEYNOTE-059 Trial. JAMA oncology. 2018;4:e180013.

- Bang YJ, Ruiz EY, Van Cutsem E, Lee KW, Wyrwicz L, Schenker M, et al. Phase III, randomised trial of avelumab versus physician’s choice of chemotherapy as third-line treatment of patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer: primary analysis of JAVELIN Gastric 300. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2018;29:2052-60.

- Wang F, Wei XL, Wang FH, Xu N, Shen L, Dai GH, et al. Safety, efficacy and tumor mutational burden as a biomarker of overall survival benefit in chemo-refractory gastric cancer treated with toripalimab, a PD-1 antibody in phase Ib/II clinical trial NCT02915432. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2019;30:1479-86.

- Sterner RC, Sterner RM. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood cancer journal. 2021;11:69.

- Ma S, Li X, Wang X, Cheng L, Li Z, Zhang C, et al. Current Progress in CAR-T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2548-60.

- Wang Z, Wu Z, Liu Y, Han W. New development in CAR-T cell therapy. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2017;10:53.

- Trarbach T, Schuler M, Zvirbule Z, Lordick F, Krilova A, Helbig U, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Multiple Doses of Imab362 in Patients with Advanced Gastro-Esophageal Cancer: Results of a Phase Ii Study. Annals of Oncology. 2014;25.

- Niimi T, Nagashima K, Ward JM, Minoo P, Zimonjic DB, Popescu NC, et al. claudin-18, a novel downstream target gene for the T/EBP/NKX2.1 homeodomain transcription factor, encodes lung- and stomach-specific isoforms through alternative splicing. Molecular and cellular biology. 2001;21:7380-90.

- Jiang H, Shi Z, Wang P, Wang C, Yang L, Du G, et al. Claudin18.2-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor Engineered T Cells for the Treatment of Gastric Cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2019;111:409-18.

- Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nature medicine. 2004;10:909-15.

- Robbins PF, Lu YC, El-Gamil M, Li YF, Gross C, Gartner J, et al. Mining exomic sequencing data to identify mutated antigens recognized by adoptively transferred tumor-reactive T cells. Nature medicine. 2013;19:747-52.

- Ku GY. The Current Status of Immunotherapies in Esophagogastric Cancer. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2019;33:323-38.

- Sadanaga N, Nagashima H, Mashino K, Tahara K, Yamaguchi H, Ohta M, et al. Dendritic cell vaccination with MAGE peptide is a novel therapeutic approach for gastrointestinal carcinomas. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2001;7:2277-84.

- Liu Q, Chu Y, Shao J, Qian H, Yang J, Sha H, et al. Benefits of an Immunogenic Personalized Neoantigen Nanovaccine in Patients with High-Risk Gastric/Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer. Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany). 2022:e2203298.

- Jenkins RW, Barbie DA, Flaherty KT. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. British Journal of Cancer. 2018;118:9-16.

- Schoenfeld AJ, Hellmann MD. Acquired Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancer cell. 2020;37:443-55.

- Ishida, Agata, Shibahara. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. Honjo J The EMBO journal. 1992.

- Lote H, Cafferkey C, Chau I. PD-1 and PD-L1 blockade in gastrointestinal malignancies. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2015;41:893-903.

- Mimura K, Kua LF, Xiao JF, Asuncion BR, Nakayama Y, Syn N, et al. Combined inhibition of PD-1/PD-L1, Lag-3, and Tim-3 axes augments antitumor immunity in gastric cancer-T cell coculture models. Gastric cancer : official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 2021;24:611-23.

- Derks S, Nason KS, Liao X, Stachler MD, Liu KX, Liu JB, et al. Epithelial PD-L2 Expression Marks Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer immunology research. 2015;3:1123-9.

- Poggio M, Hu T, Pai CC, Chu B, Belair CD, Chang A, et al. Suppression of Exosomal PD-L1 Induces Systemic Anti-tumor Immunity and Memory. Cell. 2019;177:414-27.e13.

- Batlle E, Massagué J. Transforming Growth Factor-β Signaling in Immunity and Cancer. Immunity. 2019;50:924-40.

- Chen J, Gingold JA, Su X. Immunomodulatory TGF-β Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Trends in molecular medicine. 2019;25:1010-23.

- Sad S, Mosmann TR. Single IL-2-secreting precursor CD4 T cell can develop into either Th1 or Th2 cytokine secretion phenotype. J Journal of Immunology. 1994;153:3514-22.

- Lee YS, Park JS, Kim JH, Jung SM, Lee JY, Kim SJ, et al. Smad6-specific recruitment of Smurf E3 ligases mediates TGF-β1-induced degradation of MyD88 in TLR4 signalling. Nat Commun. 2011;2:460.

- Shi T, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Song X, Wang H, Zhou X, et al. DKK1 Promotes Tumor Immune Evasion and Impedes Anti–PD-1 Treatment by Inducing Immunosuppressive Macrophages in Gastric Cancer. Cancer immunology research. 2022;10:1506-24.

- Tay C, Tanaka A, Sakaguchi S. Tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells as targets of cancer immunotherapy. Cancer cell. 2023;41:450-65.

- Li C, Jiang P, Wei S, Xu X, Wang J. Regulatory T cells in tumor microenvironment: new mechanisms, potential therapeutic strategies and future prospects. Molecular cancer. 2020;19:116.

- Nakamura K, Smyth MJ. Myeloid immunosuppression and immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2020;17:1-12.

- Vitale I, Manic G, Coussens LM, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L. Macrophages and Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell metabolism. 2019;30:36-50.

- Damo M, Joshi NS. Treg cell IL-10 and IL-35 exhaust CD8+ T cells in tumors. Nature immunology. 2019;20:674-5.

- Collison LW, Pillai MR, Chaturvedi V, Vignali DA. Regulatory T cell suppression is potentiated by target T cells in a cell contact, IL-35- and IL-10-dependent manner. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2009;182:6121-8.

- Maj T, Wang W, Crespo J, Zhang H, Wang W, Wei S, et al. Oxidative stress controls regulatory T cell apoptosis and suppressor activity and PD-L1-blockade resistance in tumor. Nature immunology. 2017;18:1332-41.

- Grossman WJ, Verbsky JW, Barchet W, Colonna M, Atkinson JP, Ley TJ. Human T regulatory cells can use the perforin pathway to cause autologous target cell death. Immunity. 2004;21:589-601.

- Wu Y, Yi M, Niu M, Mei Q, Wu K. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: an emerging target for anticancer immunotherapy. Molecular cancer. 2022;21:184.

- Terabe M, Matsui S, Park JM, Mamura M, Noben-Trauth N, Donaldson DD, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta production and myeloid cells are an effector mechanism through which CD1d-restricted T cells block cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated tumor immunosurveillance: abrogation prevents tumor recurrence. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;198:1741-52.

- Marvel D, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment: expect the unexpected. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2015;125:3356-64.

- Mazzoni A, Bronte V, Visintin A, Spitzer JH, Apolloni E, Serafini P, et al. Myeloid suppressor lines inhibit T cell responses by an NO-dependent mechanism. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2002;168:689-95.

- Smith LK, Boukhaled GM, Condotta SA, Mazouz S, Guthmiller JJ, Vijay R, et al. Interleukin-10 Directly Inhibits CD8+ T Cell Function by Enhancing N-Glycan Branching to Decrease Antigen Sensitivity. Immunity. 2018;48:299-312.e5.

- Dixon KO, Tabaka M, Schramm MA, Xiao S, Tang R, Dionne D, et al. TIM-3 restrains anti-tumour immunity by regulating inflammasome activation. Nature. 2021;595:101-6.

- Strauss L, Mahmoud MAA, Weaver JD, Tijaro-Ovalle NM, Christofides A, Wang Q, et al. Targeted deletion of PD-1 in myeloid cells induces antitumor immunity. Science immunology. 2020;5.

- Gordon SR, Maute RL, Dulken BW, Hutter G, George BM, McCracken MN, et al. PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumour immunity. Nature. 2017;545:495-9.

- Thomas DA, Massagué J. TGF-beta directly targets cytotoxic T cell functions during tumor evasion of immune surveillance. Cancer cell. 2005;8:369-80.

- Saraiva M, Vieira P, O’Garra A. Biology and therapeutic potential of interleukin-10. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2020;217.

- Song X, Traub B, Shi J, Kornmann M. Possible Roles of Interleukin-4 and -13 and Their Receptors in Gastric and Colon Cancer. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021;22.

- Zhang C, Wei S, Dai S, Li X, Wang H, Zhang H, et al. The NR_109/FUBP1/c-Myc axis regulates TAM polarization and remodels the tumor microenvironment to promote cancer development. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer. 2023;11.

- Qiao J, Liu Z, Dong C, Luan Y, Zhang A, Moore C, et al. Targeting Tumors with IL-10 Prevents Dendritic Cell-Mediated CD8+ T Cell Apoptosis. Cancer cell. 2019;35:901-15.e4.

- Guo Y, Xie YQ, Gao M, Zhao Y, Franco F, Wenes M, et al. Metabolic reprogramming of terminally exhausted CD8+ T cells by IL-10 enhances anti-tumor immunity. Nature immunology. 2021;22:746-56.

- Thompson ED, Zahurak M, Murphy A, Cornish T, Cuka N, Abdelfatah E, et al. Patterns of PD-L1 expression and CD8 T cell infiltration in gastric adenocarcinomas and associated immune stroma. Gut. 2017;66:794-801.

- Gao X, Ji K, Jia Y, Shan F, Chen Y, Xu N, et al. Cadonilimab with chemotherapy in HER2-negative gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: the phase 1b/2 COMPASSION-04 trial. Nature medicine. 2024;30:1943-51.

- Shitara K, Van Cutsem E, Bang YJ, Fuchs C, Wyrwicz L, Lee KW, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab or Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy vs Chemotherapy Alone for Patients With First-line, Advanced Gastric Cancer: The KEYNOTE-062 Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA oncology. 2020;6:1571-80.

- Shitara K, Özgüroğlu M, Bang YJ, Di Bartolomeo M, Mandalà M, Ryu MH, et al. Pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel for previously treated, advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (KEYNOTE-061): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England). 2018;392:123-33.

- Sun T, Zhou Y, Yang M, Hu Z, Tan W, Han X, et al. Functional genetic variations in cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 and susceptibility to multiple types of cancer. Cancer research. 2008;68:7025-34.

- Lin SJ, Gagnon-Bartsch JA, Tan IB, Earle S, Ruff L, Pettinger K, et al. Signatures of tumour immunity distinguish Asian and non-Asian gastric adenocarcinomas. Gut. 2015;64:1721-31.

- Ammannagari N, Atasoy A. Current status of immunotherapy and immune biomarkers in gastro-esophageal cancers. Journal of gastrointestinal oncology. 2018;9:196-207.

- Zhuang Y, Peng LS, Zhao YL, Shi Y, Mao XH, Chen W, et al. CD8(+) T cells that produce interleukin-17 regulate myeloid-derived suppressor cells and are associated with survival time of patients with gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:951-62.e8.

- Galon J, Pagès F, Marincola FM, Angell HK, Thurin M, Lugli A, et al. Cancer classification using the Immunoscore: a worldwide task force. Journal of translational medicine. 2012;10:205.

- Lytle JR, Yario TA, Steitz JA. Target mRNAs are repressed as efficiently by microRNA-binding sites in the 5’ UTR as in the 3’ UTR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:9667-72.

- Svoronos AA, Engelman DM, Slack FJ. OncomiR or Tumor Suppressor? The Duplicity of MicroRNAs in Cancer. Cancer research. 2016;76:3666-70.

- Yoon CJ, Chang MS, Kim DH, Kim W, Koo BK, Yun SC, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded miR-BART5-5p upregulates PD-L1 through PIAS3/pSTAT3 modulation, worsening clinical outcomes of PD-L1-positive gastric carcinomas. Gastric cancer : official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 2020;23:780-95.

- Li J, Sun D, Pu W, Wang J, Peng Y. Circular RNAs in Cancer: Biogenesis, Function, and Clinical Significance. Trends in cancer. 2020;6:319-36.

- Salzman J, Chen RE, Olsen MN, Wang PL, Brown PO. Cell-type specific features of circular RNA expression. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1003777.

- Wilusz JE, Sharp PA. Molecular biology. A circuitous route to noncoding RNA. Science (New York, NY). 2013;340:440-1.

- Chen S-W, Zhu S-Q, Pei X, Qiu B-Q, Xiong D, Long X, et al. Cancer cell-derived exosomal circUSP7 induces CD8+ T cell dysfunction and anti-PD1 resistance by regulating the miR-934/SHP2 axis in NSCLC. Molecular cancer. 2021;20.

- Garewal HS, Robertone A, Salmon SE, Jones SE, Alberts DS, Brooks R. Phase I trial of esorubicin (4’deoxydoxorubicin). Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1984;2:1034-9.

- Jiang H, Yu X, Li N, Kong M, Ma Z, Zhou D, et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant sintilimab, oxaliplatin and capecitabine in patients with locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: early results of a phase 2 study. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer. 2022;10.

- Zindel J, Kubes P. DAMPs, PAMPs, and LAMPs in Immunity and Sterile Inflammation. Annual review of pathology. 2020;15:493-518.

- Murao A, Aziz M, Wang H, Brenner M, Wang P. Release mechanisms of major DAMPs. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death. 2021;26:152-62.

- Pulendran B, P SA, O’Hagan DT. Emerging concepts in the science of vaccine adjuvants. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2021;20:454-75.

- Zhang R, Wang C, Guan Y, Wei X, Sha M, Yi M, et al. Manganese salts function as potent adjuvants. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2021;18:1222-34.

- Abouelnazar FA, Zhang X, Zhang J, Wang M, Yu D, Zang X, et al. SALL4 promotes angiogenesis in gastric cancer by regulating VEGF expression and targeting SALL4/VEGF pathway inhibits cancer progression. Cancer cell international. 2023;23:149.

- Jain RK. Antiangiogenesis strategies revisited: from starving tumors to alleviating hypoxia. Cancer cell. 2014;26:605-22.

- Jain RK. Normalizing tumor microenvironment to treat cancer: bench to bedside to biomarkers. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:2205-18.

- Zheng W, Sun G, Li Z, Wu F, Sun G, Cao H, et al. The Effect of Anlotinib Combined with anti-PD-1 in the Treatment of Gastric Cancer. Frontiers in surgery. 2022;9:895982.

- Cheng N, Li P, Cheng H, Zhao X, Dong M, Zhang Y, et al. Prognostic Value of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Tertiary Lymphoid Structures in Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated and -Negative Gastric Carcinoma. Frontiers in immunology. 2021;12:692859.

- Paijens ST, Vledder A, de Bruyn M, Nijman HW. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the immunotherapy era. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2021;18:842-59.

- Sugiyama D, Nishikawa H, Maeda Y, Nishioka M, Tanemura A, Katayama I, et al. Anti-CCR4 mAb selectively depletes effector-type FoxP3+CD4+ regulatory T cells, evoking antitumor immune responses in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:17945-50.

- Doi T, Muro K, Ishii H, Kato T, Tsushima T, Takenoyama M, et al. A Phase I Study of the Anti-CC Chemokine Receptor 4 Antibody, Mogamulizumab, in Combination with Nivolumab in Patients with Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2019;25:6614-22.

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646-74.

- Kim R, Kwon M, An M, Kim ST, Smith SA, Loembé AB, et al. Phase II study of ceralasertib (AZD6738) in combination with durvalumab in patients with advanced/metastatic melanoma who have failed prior anti-PD-1 therapy. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2022;33:193-203.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).