Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

28 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Date source

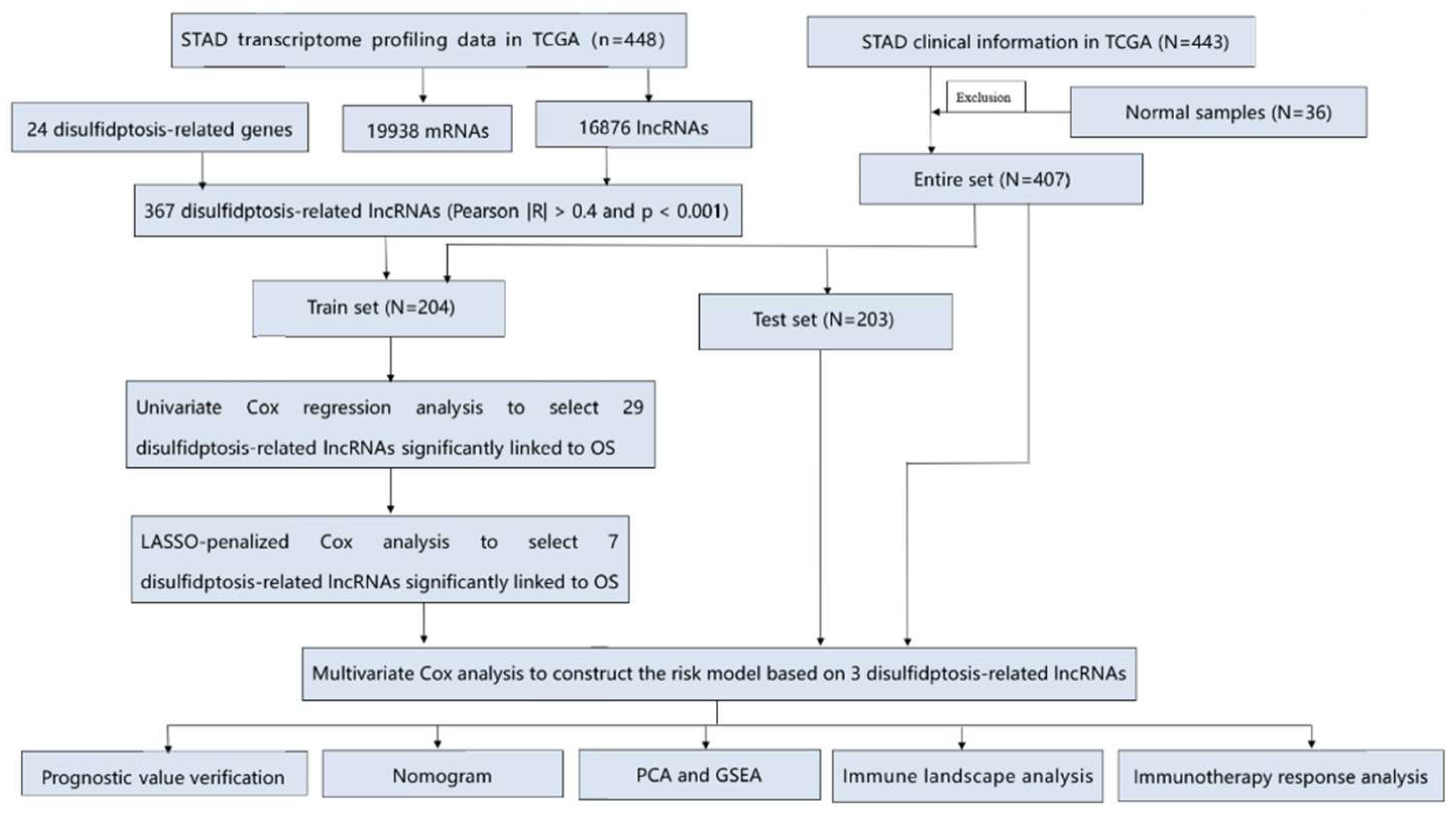

2.2. The development and verification of the arlncRNAs signature

2.3. Independent prognostic analysis and ROC curve plotting

2.4. Nomagram and Calibration

2.5. Gene set enrichment analysis

2.6. Investigation of TME, immune infiltration and immune checkpoints

2.7. TMB, MSI and TIDE

2.8. Drug sensitivity analysis

3. Results

3.1. Data source and processing

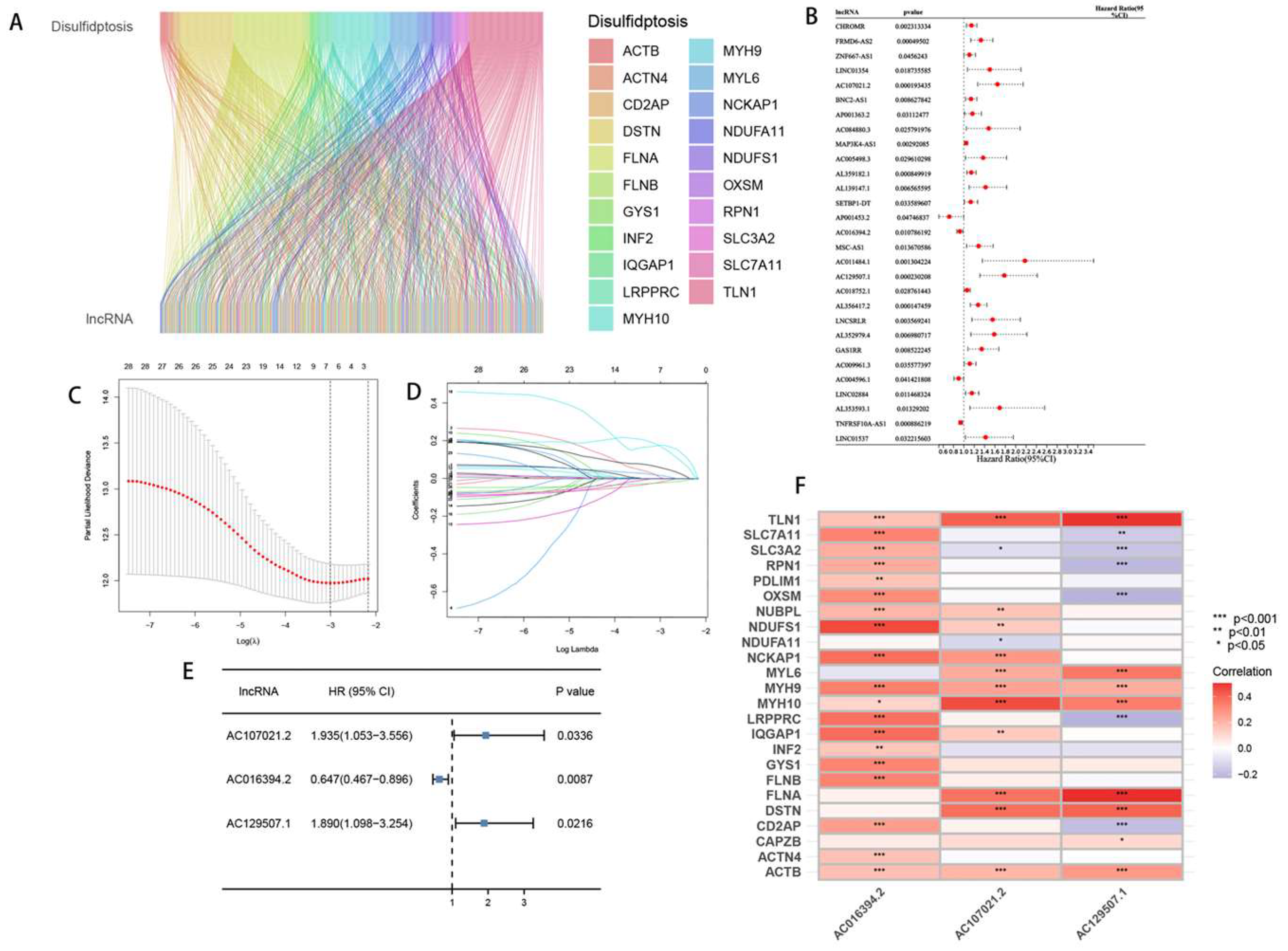

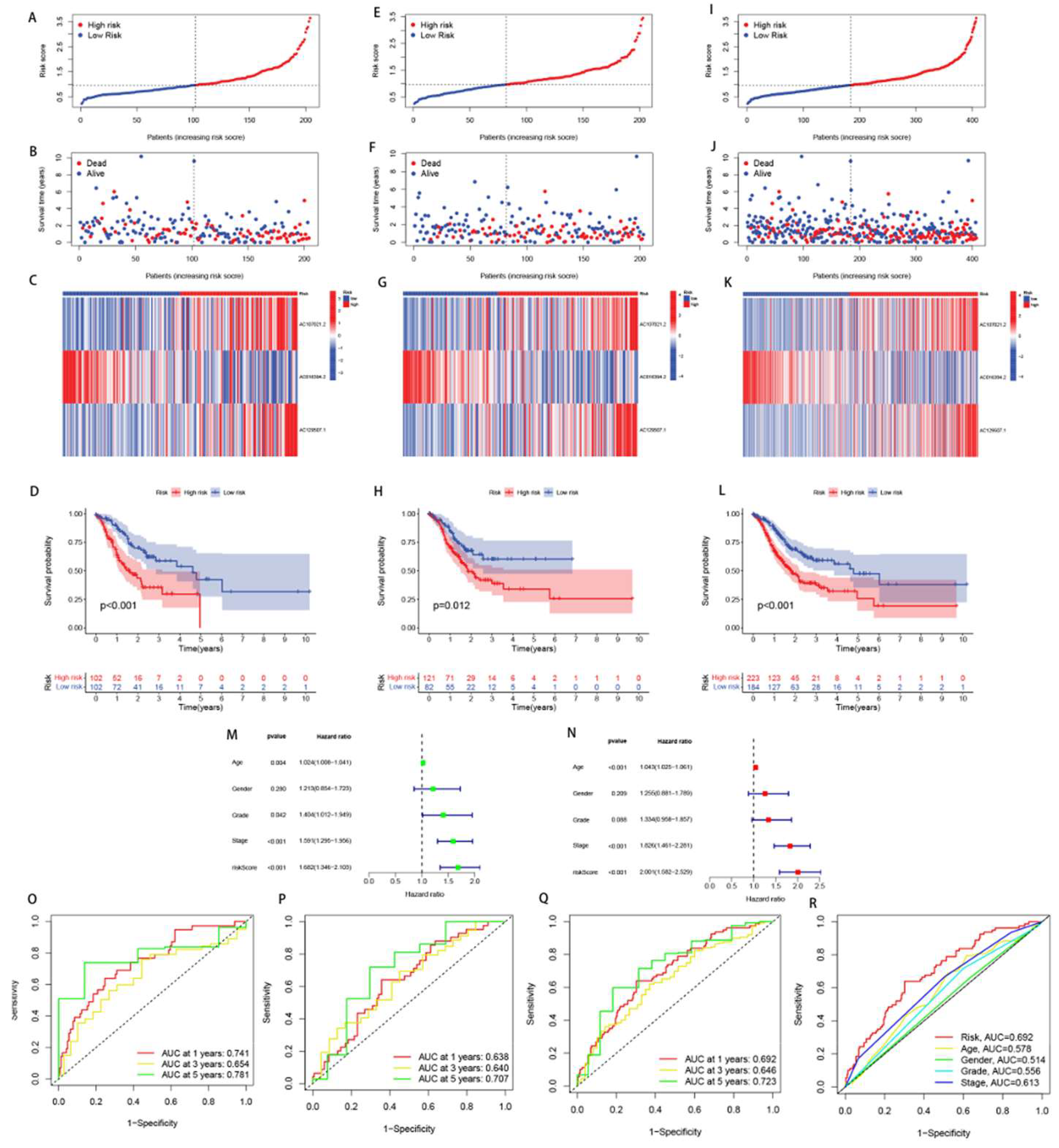

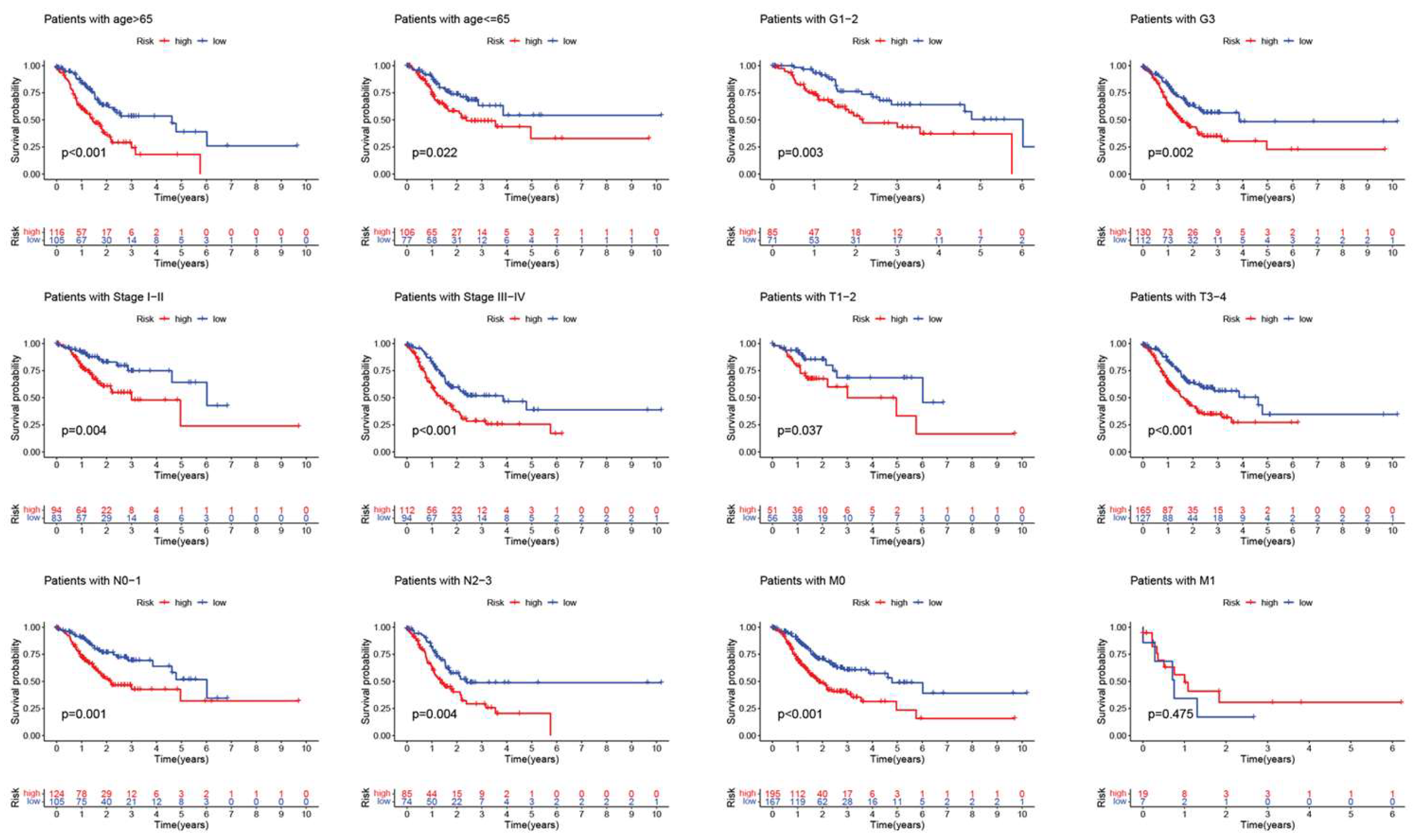

3.2. Construction and validation of the drlncRNA prognostic model

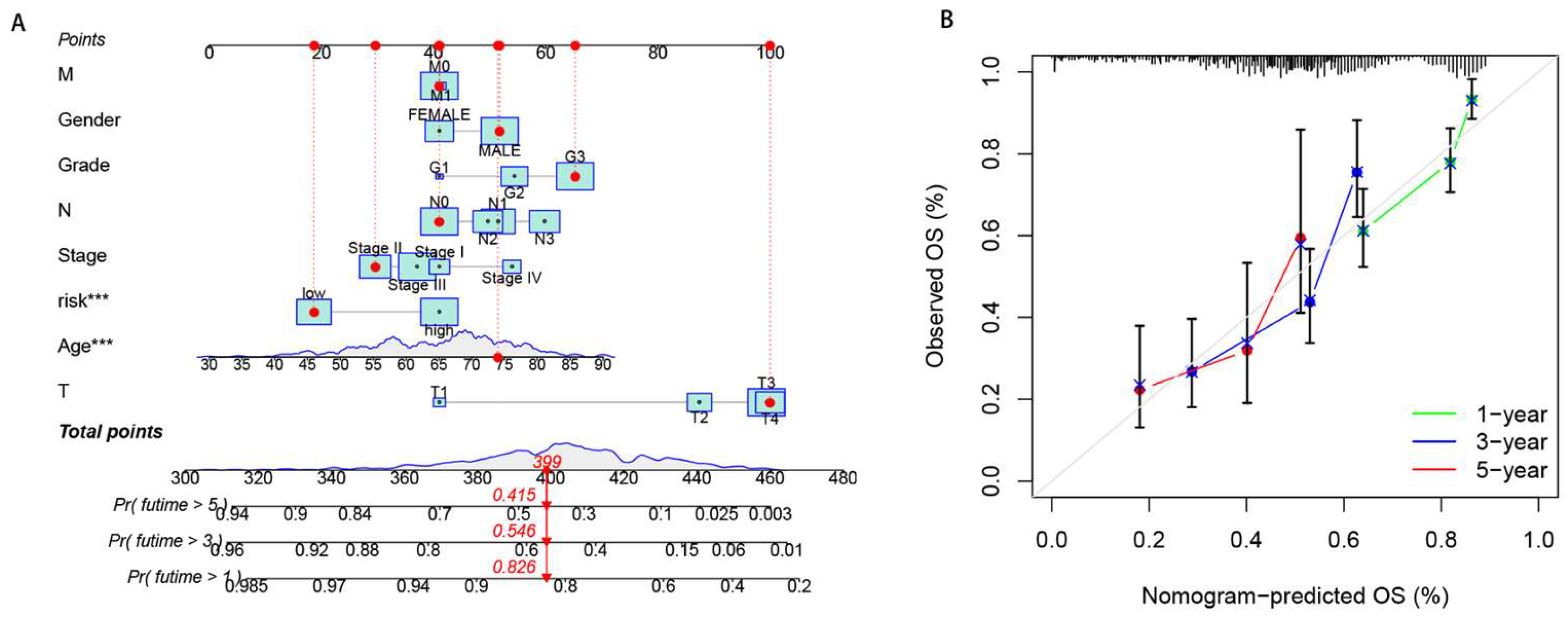

3.3. Nomogram and calibration curves

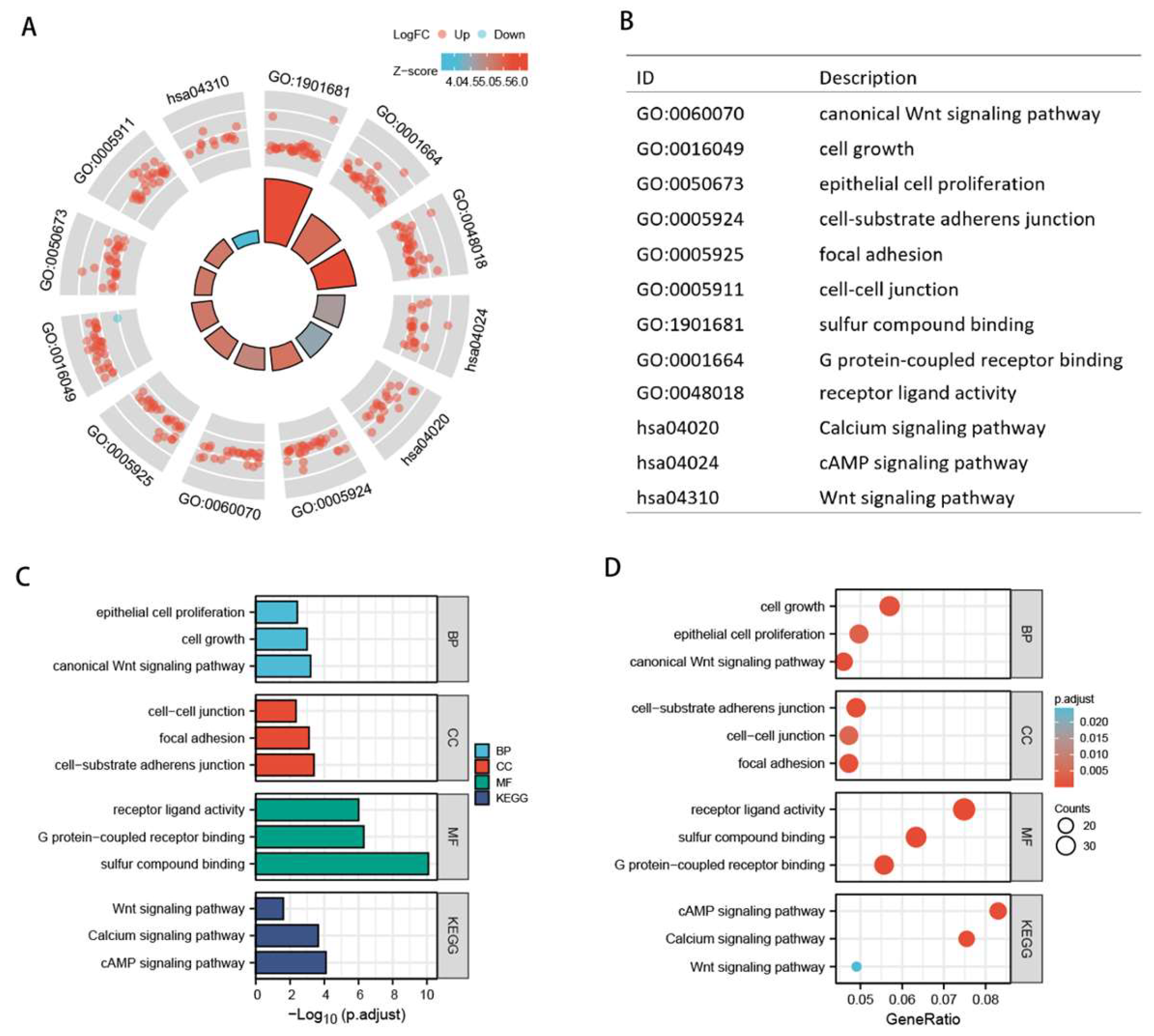

3.4. Functional analysis of the model

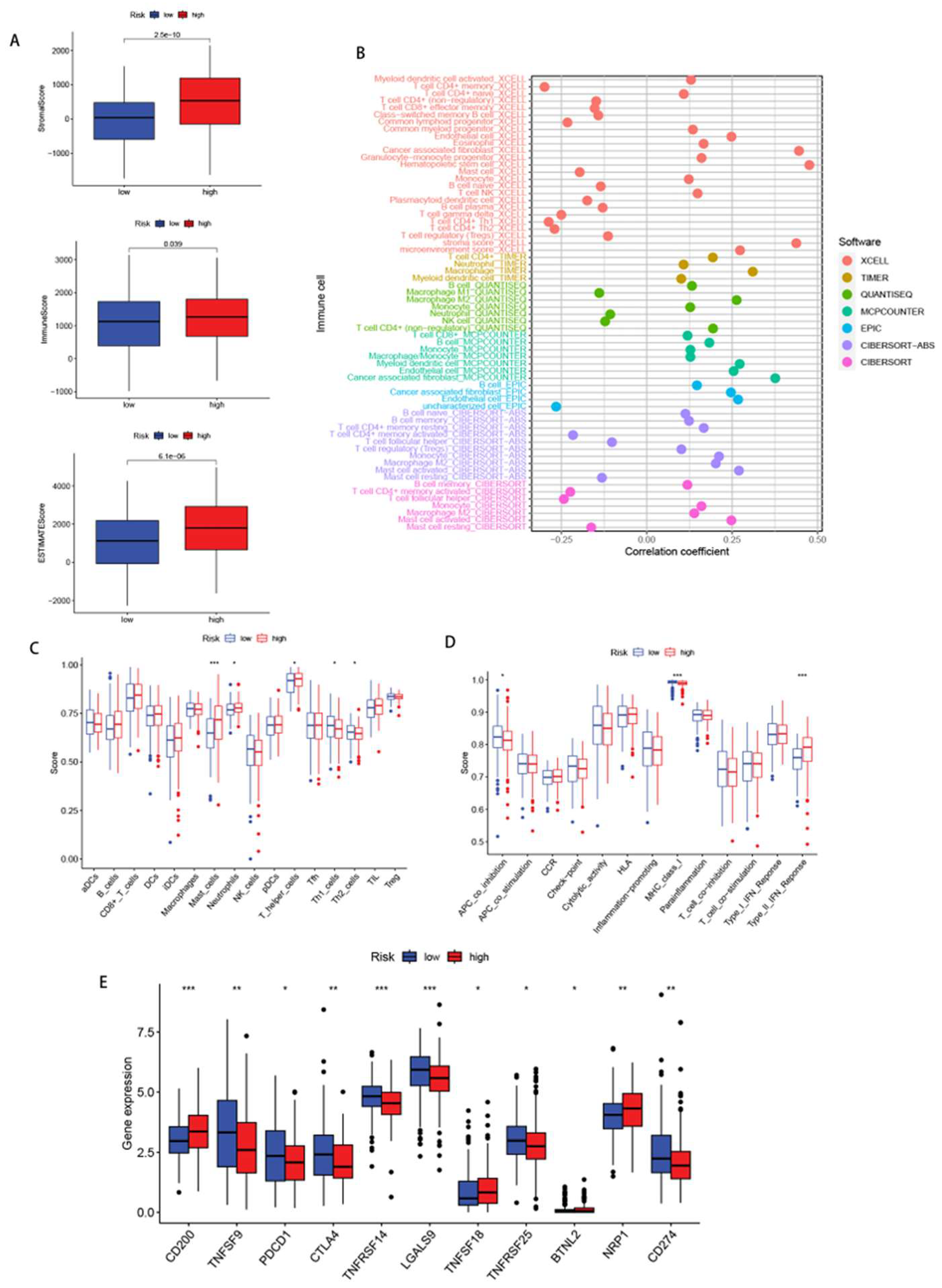

3.5. Immune infiltration status

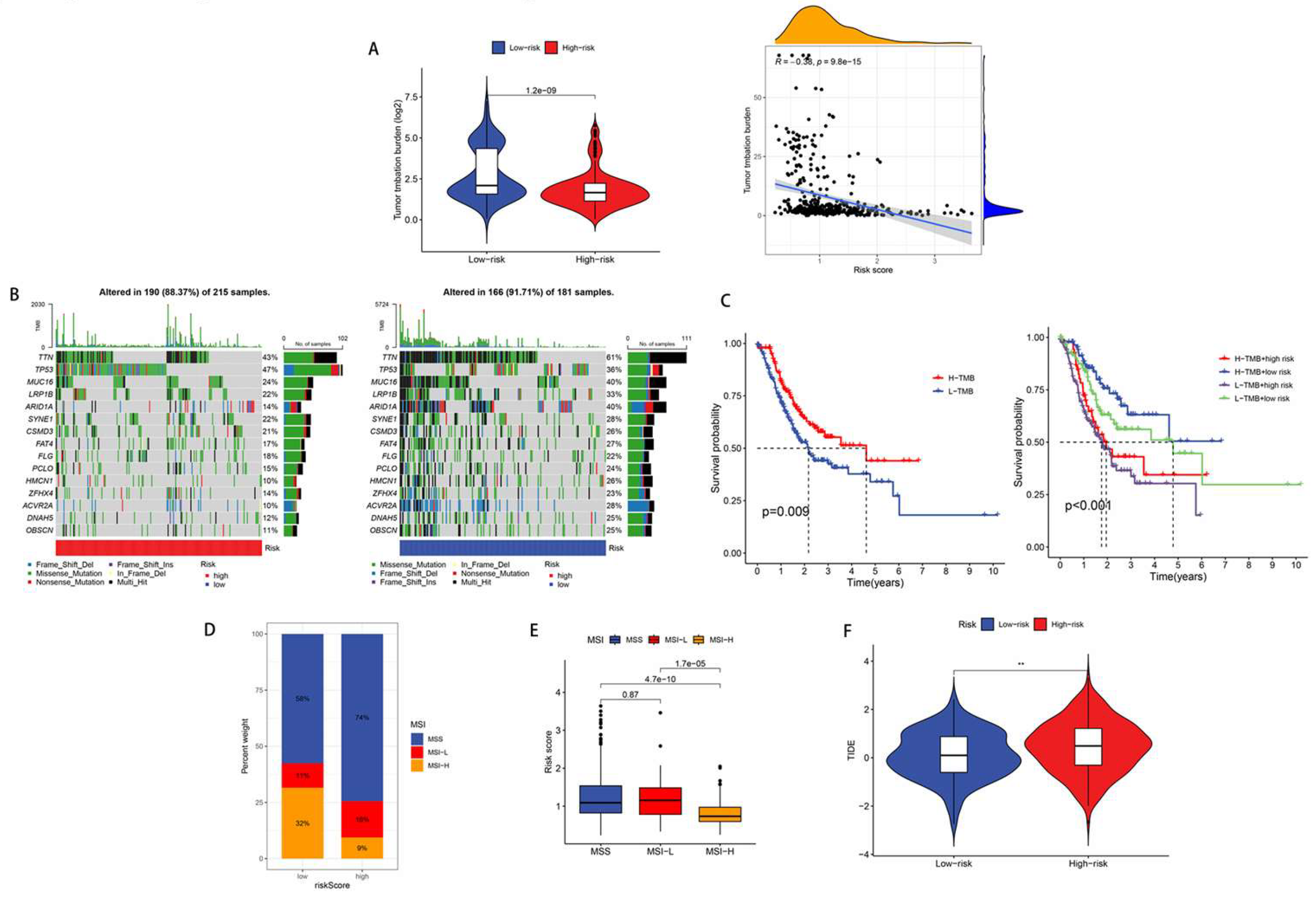

3.6. Immunotherapy response analysis

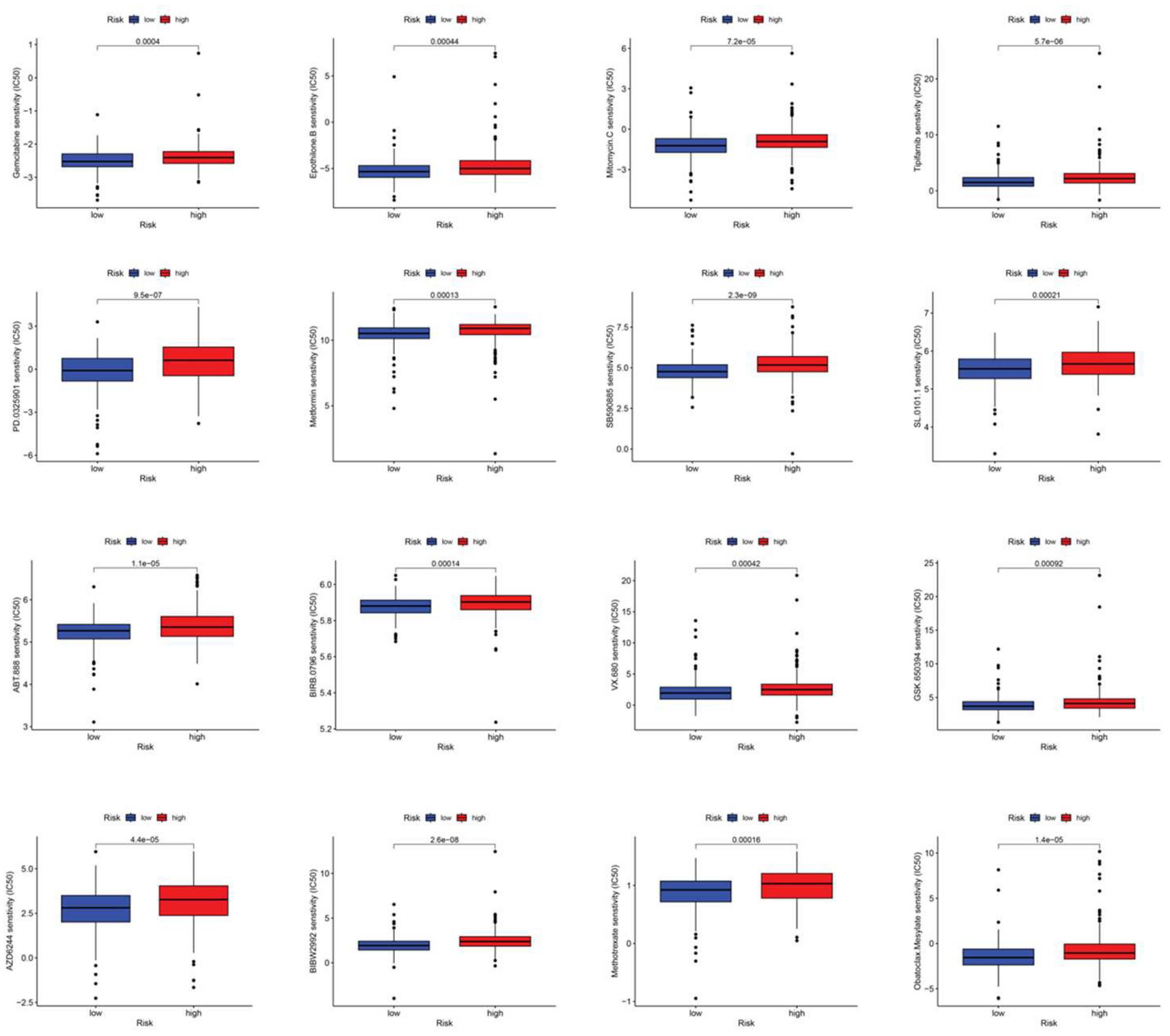

3.7. Drug sensitive analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Cutsem, E.; Sagaert, X.; Topal, B.; Haustermans, K.; Prenen, H. Gastric cancer. Lancet (London, England) 2016, 388, 2654–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Camargo, M.C.; Gini, A.; Kunzmann, A.T.; Matsuda, T.; Meheus, F.; Verhoeven, R.H.A.; Vignat, J.; Laversanne, M.; et al. The current and future incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in 185 countries, 2020-40: A population-based modelling study. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 47, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrift, A.P.; El-Serag, H.B. Burden of Gastric Cancer. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 2020, 18, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, P.; Islami, F.; Anandasabapathy, S.; Freedman, N.D.; Kamangar, F. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2014, 23, 700–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Meltzer, S.J. Gastric Cancer in the Era of Precision Medicine. Cellular and molecular gastroenterology and hepatology 2017, 3, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Liu, Z.; Yang, D.; Yin, K.; Chang, X. Recent Progress and Future Perspectives of Immunotherapy in Advanced Gastric Cancer. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 948647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki Vareki, S.; Garrigós, C.; Duran, I. Biomarkers of response to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology 2017, 116, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Nie, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, C.; Colic, M.; Olszewski, K.; Horbath, A.; Chen, X.; Lei, G.; et al. Actin cytoskeleton vulnerability to disulfide stress mediates disulfidptosis. Nature cell biology 2023, 25, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppula, P.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Cystine transporter SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: ferroptosis, nutrient dependency, and cancer therapy. Protein & cell 2021, 12, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Liu, Q.; Xing, F.; Zeng, C.; Wang, W. Disulfidptosis: a new form of programmed cell death. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR 2023, 42, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Zhou, C.; Ding, Y.; Duan, S. Disulfidptosis: a new target for metabolic cancer therapy. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR 2023, 42, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, Y.; Ma, Z.; Liu, W.; Yu, T.; Yan, C.; Jiang, H.; Tian, S.; Xu, T.; Shu, Y. TEAD4 modulated LncRNA MNX1-AS1 contributes to gastric cancer progression partly through suppressing BTG2 and activating BCL2. Molecular cancer 2020, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Gou, H.; Wang, D.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Su, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J. LncRNA TNFRSF10A-AS1 promotes gastric cancer by directly binding to oncogenic MPZL1 and is associated with patient outcome. International journal of biological sciences 2022, 18, 3156–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Liu, X.; Wu, H.; Yu, X.; Wei, C.; Huang, X.; Ji, G.; Nie, F.; Wang, K. Long noncoding AGAP2-AS1 is activated by SP1 and promotes cell proliferation and invasion in gastric cancer. Journal of hematology & oncology 2017, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.W.; Xia, R.; Lu, K.; Xie, M.; Yang, F.; Sun, M.; De, W.; Wang, C.; Ji, G. LincRNAFEZF1-AS1 represses p21 expression to promote gastric cancer proliferation through LSD1-Mediated H3K4me2 demethylation. Molecular cancer 2017, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Yu, Q.; Huang, R.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liao, L. Stromal score as a prognostic factor in primary gastric cancer and close association with tumor immune microenvironment. Cancer medicine 2020, 9, 4980–4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Niu, R. Identification of the three subtypes and the prognostic characteristics of stomach adenocarcinoma: analysis of the hypoxia-related long non-coding RNAs. Functional & integrative genomics 2022, 22, 919–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, F.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Shi, Z.; Li, X.; Wu, D.; Liu, H.; Chen, J. Necroptosis-related lncRNA in lung adenocarcinoma: A comprehensive analysis based on a prognosis model and a competing endogenous RNA network. Frontiers in genetics 2022, 13, 940167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, X.; Leng, Q.; Tan, J.; Huang, H.; Zhong, R.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y. Cuproptosis-related lncRNAs emerge as a novel signature for predicting prognosis in prostate carcinoma and functional experimental validation. Frontiers in immunology 2024, 15, 1471198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Li, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhou, Y. Comprehensive Analysis of Disulfidptosis-Related LncRNAs in Molecular Classification, Immune Microenvironment Characterization and Prognosis of Gastric Cancer. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, V.H.; Yung, B.S.; Faraji, F.; Saddawi-Konefka, R.; Wang, Z.; Wenzel, A.T.; Song, M.J.; Pagadala, M.S.; Clubb, L.M.; Chiou, J.; et al. The GPCR-Gα(s)-PKA signaling axis promotes T cell dysfunction and cancer immunotherapy failure. Nature immunology 2023, 24, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.J.; Yang, Y.; Peng, W.T.; Sun, J.C.; Sun, W.Y.; Wei, W. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 regulating β2-adrenergic receptor signaling in M2-polarized macrophages contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma progression. OncoTargets and therapy 2019, 12, 5499–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, S.; Ghosh, P.; Kusaba, H.; Buchholz, M.; Longo, D.L. Effect of promoter methylation on the regulation of IFN-gamma gene during in vitro differentiation of human peripheral blood T cells into a Th2 population. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 2003, 171, 2510–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.; Gu, L.; Ning, H.; Zhang, Y.; Hsueh, E.C.; Fu, M.; Hu, X.; Wei, L.; Hoft, D.F.; Liu, J. Increased Th17 cells in the tumor microenvironment is mediated by IL-23 via tumor-secreted prostaglandin E2. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 2013, 190, 5894–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zhang, W. Th17 cells: positive or negative role in tumor? Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII 2010, 59, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, Z.; Mohammadi, H.; Safarzadeh, E.; Hemmatzadeh, M.; Mahdian-Shakib, A.; Jadidi-Niaragh, F.; Azizi, G.; Baradaran, B. The paradox of Th17 cell functions in tumor immunity. Cellular immunology 2017, 322, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Hua, H.; Jiang, Y. cAMP-PKA/EPAC signaling and cancer: the interplay in tumor microenvironment. Journal of hematology & oncology 2024, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Feng, Z.P. The good and bad of microglia/macrophages: new hope in stroke therapeutics. Acta pharmacologica Sinica 2013, 34, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aras, S.; Zaidi, M.R. TAMeless traitors: macrophages in cancer progression and metastasis. British journal of cancer 2017, 117, 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, B.; Zhu Chen, L.; Paniagua-Sancho, M.; Marchal, J.A.; Perán, M.; Giovannetti, E. Deciphering the performance of macrophages in tumour microenvironment: a call for precision immunotherapy. Journal of hematology & oncology 2024, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, R.; Connelly, T.; Choi, R.; Choi, H.; Samarkina, A.; Li, L.; Gregorio, E.; Chen, Y.; Thakur, R.; Abdel-Mohsen, M.; et al. Tumor-infiltrating mast cells are associated with resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy. Nature communications 2021, 12, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.C.; Balko, J.M. Mechanisms of MHC-I Downregulation and Role in Immunotherapy Response. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 844866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janjigian, Y.Y.; Shitara, K.; Moehler, M.; Garrido, M.; Salman, P.; Shen, L.; Wyrwicz, L.; Yamaguchi, K.; Skoczylas, T.; Campos Bragagnoli, A.; et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England) 2021, 398, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennock, G.K.; Chow, L.Q. The Evolving Role of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer Treatment. The oncologist 2015, 20, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Wolchok, J.D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2018, 359, 1350–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, S.; Agrawal, M.Y.; Kaushik, I.; Ramachandran, S.; Srivastava, S.K. Immune checkpoint proteins: Signaling mechanisms and molecular interactions in cancer immunotherapy. Seminars in cancer biology 2022, 86, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionov, Y.; Peinado, M.A.; Malkhosyan, S.; Shibata, D.; Perucho, M. Ubiquitous somatic mutations in simple repeated sequences reveal a new mechanism for colonic carcinogenesis. Nature 1993, 363, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lamberti, G.; Di Federico, A.; Alessi, J.; Ferrara, R.; Sholl, M.L.; Awad, M.M.; Vokes, N.; Ricciuti, B. Tumor mutational burden for the prediction of PD-(L)1 blockade efficacy in cancer: challenges and opportunities. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2024, 35, 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wei, X.L.; Wang, F.H.; Xu, N.; Shen, L.; Dai, G.H.; Yuan, X.L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, S.J.; Shi, J.H.; et al. Safety, efficacy and tumor mutational burden as a biomarker of overall survival benefit in chemo-refractory gastric cancer treated with toripalimab, a PD-1 antibody in phase Ib/II clinical trial NCT02915432. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2019, 30, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Lewis, K.D.; Gutzmer, R.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Gogas, H.; Protsenko, S.; Pereira, R.P.; Eigentler, T.; Rutkowski, P.; Demidov, L.; et al. Biomarkers of treatment benefit with atezolizumab plus vemurafenib plus cobimetinib in BRAF(V600) mutation-positive melanoma. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2022, 33, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budczies, J.; Kazdal, D.; Menzel, M.; Beck, S.; Kluck, K.; Altbürger, C.; Schwab, C.; Allgäuer, M.; Ahadova, A.; Kloor, M.; et al. Tumour mutational burden: clinical utility, challenges and emerging improvements. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology 2024, 21, 725–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastenhuber, E.R.; Lowe, S.W. Putting p53 in Context. Cell 2017, 170, 1062–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Cao, J.; Topatana, W.; Juengpanich, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, B.; Shen, J.; Cai, L.; Cai, X.; Chen, M. Targeting mutant p53 for cancer therapy: direct and indirect strategies. Journal of hematology & oncology 2021, 14, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, M.; Hollstein, M.; Hainaut, P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2010, 2, a001008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, R.; Kato, S.; Lee, S.; Jimenez, R.E.; Sicklick, J.K.; Kurzrock, R. ARID1A alterations function as a biomarker for longer progression-free survival after anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, S.; Chen, Y.; Anandhan, S.; Szabo, P.M.; Basu, S.; Blando, J.M.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Natarajan, S.M.; Xiong, L.; et al. ARID1A mutation plus CXCL13 expression act as combinatorial biomarkers to predict responses to immune checkpoint therapy in mUCC. Science translational medicine 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, M.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, X. ARID1A Mutations Are Associated with Increased Immune Activity in Gastrointestinal Cancer. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindson, J. Gemcitabine and cisplatin plus immunotherapy in advanced biliary tract cancer: a phase II study. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology 2022, 19, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.M.; Patel, J.D.; Robert, F.; Kio, E.A.; Thara, E.; Ross Camidge, D.; Dunbar, M.; Nuthalapati, S.; Dinh, M.H.; Bach, B.A. Veliparib and nivolumab in combination with platinum doublet chemotherapy in patients with metastatic or advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A phase 1 dose escalation study. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2021, 161, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).