Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. PolyModel Theory

2.1. Mathematical Formulation and Model Estimation

2.1.1. Model Description and Estimation

- A pool of target assets which are the components of the portfolios one want to construct.

- A very large pool of risk factors which form a proxy of the real-world financial environment.

- n is the number of the risk factors.

- is assumed to capture the major relationship between independent variable and dependent variable ; in practice, it is usually a polynomial of some low degree.

- is the noise term in the regression model with zero mean; usually it is assumed to be normal distribution but does not have to be.

- denotes the vector of the target time series such of return of hedge fund

- denotes the following matrix of the risk factorwhich is a matrix, where is the Hermitian polynomial of degree k.

- denotes the regression error vector

- is the coefficient vector of length 5

2.2. Feature Importance and Construction

2.2.1. Fundamental Statistical Quantities

-

and adjustedAs PolyModel is a collection of simple regression models, then it is quite natural to talk about for every simple regression model., also known as coefficient of determination, is one of the most common criteria to check the fitting goodness of a regression model. It is defined as follows:where, if we denote by , and denote the vector of average of entries of with the same length by , then

- ESS is the explained sum of squares which is .

- RSS is the residual sum of squares which is .

- TSS is the total sum of squares which is .

Moreover, it is a well-known fact in regression theory that TSS = RSS + ESS.measures how much total uncertainty is explained by the fitted model based on the observed data, thus, the higher is, the better the model should be. However, this statistic does not take the number of model complexity into consideration, thus, a high may also indicates overfitting and usually this is the case (for instance, in a one dimension problem given general n data points, there is usually a degree polynomial which can pass through every one of them). Various modifications have been introduced, one very direct generalization is the adjusted-: where n is the number of observations and p is the number of coefficients in the regression model. -

Target Shuffling and P-Value ScoreTo avoid fake strong relationship between target and risk factors, we apply target shuffling which is particular useful to identify "cause-and-effect" relationship. By shuffling the the targets, we have the chance to determine if the relationship fitted by the regression model is significant enough by checking the probability of the we have seen based on the observations.The procedure can be summarized as follows:

- Do random shuffles on the target time series observations many times, say N times. For each , let we assume that there are T data points . We fix the order of , and we do N times of random shuffle of . In this way, we try to break any relation from the original data set and create any possible relations between the target and risk factor.

-

For each newly ordered target observations , we can fit a simple regression model and calculate the . Then we get.Thus, we have a population of based on above procedures.

-

Evaluate the significance of the calculated from the original data, for instance, we can calculate the p-value of it based on the population from last step. Here we assume that our original for target asset and risk factor is denoted as . Then, we could define.

- We compute and call it P-Value Score of target asset and risk factor which indicates the importance of the risk factor to the target asset time series .

The higher the P-Value Score is, the more important the risk factor is. As we also need to take different regimes over the time into the picture, at each time stamp, we only look at the past 3 years’ return data, and thus, we can have a dynamic P-Value Score series for each target asset and risk factor pair.

2.2.2. Feature Construction

-

Sharpe RatioIt is one of the most common statistical metric to estimate the performance of a portfolio. Roughly speaking, it is the ration between the portfolio return and its volatility, thus, usually is regarded as a measure of the ratio between reward and risk.Assume R represents the return of the target portfolio, represents the return of the benchmark financial time series, for instance, RFR. Then Sharpe Ratio is defined asIn practice, one may also ignore the benchmark if it is very small or static. Notice that Sharpe Ratio is a feature that is only dependent on target portfolio itself.

-

Morningstar Risk-adjusted Return (MRaR)This is another feature mostly dependent on the target portfolio itself. Given the target portfolio (e.g. hedge fund return ), denote its return at time t as ; denote the return of benchmark at time t as , the MRaR over n months is defined as follows [42]where n is the total number of months in calculation period; is the geometric excess return at month t; is the risk aversion parameter, and uses 2. Investors can adjust the value of according to their own risk flavors.

-

StressVaR (SVaR)SVaR can be regarded as a good alternative risk measure instead of VaR, in fact, it can be regarded as a factor model-based VaR. However, its strength resides in the modeling of nonlinearities and the capability to analyze a very large number of potential risk factors [45].There are three major steps in the estimation of StressVaR of a hedge fund .

- (a)

- Most relevant risk factors selection: for each risk factor , we can calculate the P-Value Score of it with respect to . Recall section 2.5.2, this score can indicate the explanation power of risk factor , and the application of target shuffling improves the ability of our model in preventing discovering non-casual relations. Once a threshold of P-Value Score is set, we can claim that all the risk factors whose P-Value Score is above the threshold are the most relevant risk factors, and denote the whole set of them as .

- (b)

-

Estimation of the Maximum Loss of : For every risk factor , using the fitted polynomial for the pair , we can predict the return of for all risk factor returns from to quantiles of the risk factor distributions. In particular, we are interested in the potential loss of corresponding to of the factor returns. Once this is estimated for one factor , we can define for the pair as follows:where

- is the maximum potential loss corresponding to quantile of risk factor .

- is unexplained variance under the ordinary least square setting which can be estimated by the following unbiased estimator if penalty terms are added to the regression modelswhere p is the degree of freedom of the regression model.

- where is the cumulative distribution function (cdf) of standard normal distribution.

- (c)

- Calculation of StressVaR: The definition of StressVaR of is

-

Long-term alpha (LTA)For the given hedge fund and risk factor pair , assume we already fitted the regression polynomial . Assume that represents the q-quantile of the empirical distribution of where . They are calculated using the very long history of the factor. The extremes and are computed by fitting a Pareto distribution on the tails.Then we definesubject to , where correspond to Lagrange method of interpolating an integral and are hyper-parameters.The global LTA (long-term average) is the median of the factor expectations for selected factors. for is defined as the quantile among all the LTA(, ) values, where represents the selected ones.

-

Long-term ratio (LTR)Once we get the and for , is simply defined as

-

Long-term stability (LTS)For fund , where is a hyper-parameter whose value is set to .

3. Methodology

3.1. Inverted Transformers (iTransformer)

3.2. Hedge Fund Performance Prediction

4. Portfolio Construction

5. Experiments and Results

5.1. Data Description

| Label | Code |

|---|---|

| T-Bil | INGOVS USAB |

| SWAP 1Y Zone USA In USD DIRECT VAR-LOG |

INMIDR USAB |

| American Century Zero Coupon 2020 Inv (BTTTX) 1989 |

BTTTX |

| COMMODITY GOLD Zone USA In USD DIRECT VAR-LOG |

COGOLD USAD |

| EQUITY MAIN Zone NORTH AMERICA In USD MEAN VAR-LOG |

EQMAIN NAMM |

| ... | ... |

| Fund Name |

|---|

| 400 Capital Credit Opportunities Fund LP |

| Advent Global Partners Fund |

| Attunga Power & Enviro Fund |

| Barington Companies Equity Partners LP |

| BlackRock Aletsch Fund Ltd |

| Campbell Managed Futures Program |

| ... |

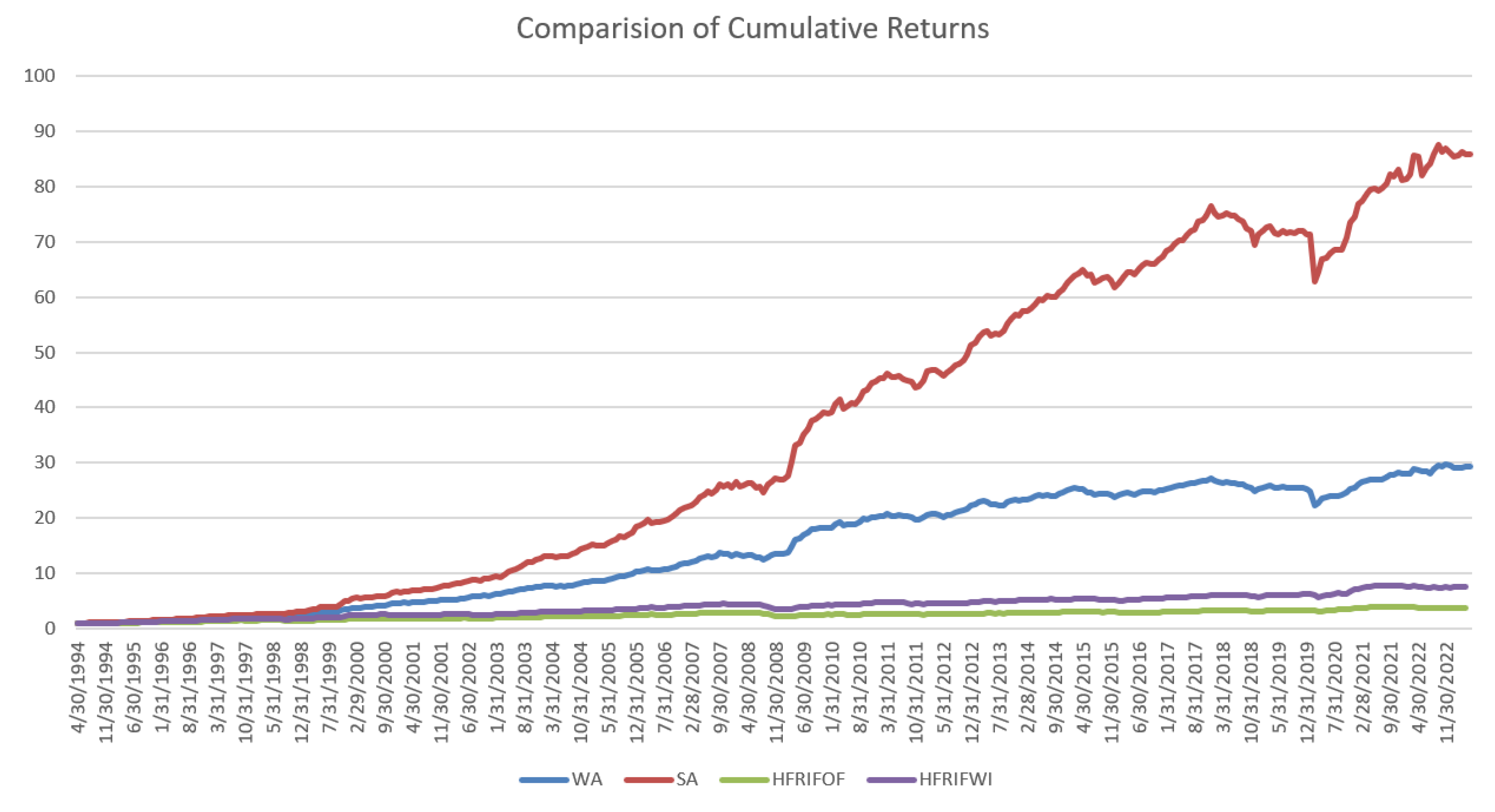

5.2. Benchmark Description

-

HFRI Fund of Funds Composite Index (HFRIFOF)“Fund of Funds invest with multiple managers through funds or managed accounts. The strategy designs a diversified portfolio of managers with the objective of significantly lowering the risk (volatility) of investing with an individual manager. The Fund of Funds manager has discretion in choosing which strategies to invest in for the portfolio. A manager may allocate funds to numerous managers within a single strategy, or with numerous managers in multiple strategies. The minimum investment in a Fund of Funds may be lower than an investment in an individual hedge fund or managed account. The investor has the advantage of diversification among managers and styles with significantly less capital than investing with separate managers. PLEASE NOTE: The HFRI Fund of Funds Index is not included in the HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index."

-

HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index (HFRIFWI)“The HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index is a global, equal-weighted index of single-manager funds that report to HFR Database. Constituent funds report monthly net of all fees performance in US Dollar and have a minimum of $50 Million under management or $10 Million under management and a twelve (12) month track record of active performance. The HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index does not include Funds of Hedge Funds."

5.3. Performance of the Constructed Portfolio

6. Conclusion

References

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. The capital asset pricing model: Theory and evidence. Journal of economic perspectives 2004, 18, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Savarese, S.; Hoi, S. Blip-2: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training with frozen image encoders and large language models. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2023; pp. 19730–19742. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Kim, J.; Polak, P. Mapping the Invisible: Face-GPS for Facial Muscle Dynamics in Videos. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE First International Conference on Artificial Intelligence for Medicine, Health and Care (AIMHC). IEEE; 2024; pp. 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Dong, Z.; Polak, P. Face-GPS: A Comprehensive Technique for Quantifying Facial Muscle Dynamics in Videos. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging Meets NeurIPS: An official NeurIPS Workshop; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, H.C.; Yan, P.; Tan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, B. Multiple distresses detection for Asphalt Pavement using improved you Only Look Once Algorithm based on convolutional neural network. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2024, 25, 2308169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, H.C.; Lu, B.; Li, M. Evaluation of asphalt pavement texture using multiview stereo reconstruction based on deep learning. Construction and Building Materials 2024, 412, 134837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, F.; Jiang, Y.; Fu, Z. Mm-bsn: Self-supervised image denoising for real-world with multi-mask based on blind-spot network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2023; pp. 4189–4198. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, F. Self-supervised image denoising for real-world images with context-aware transformer. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 14340–14349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Beedu, A.; Sheinkopf, J.; Essa, I. Mamba Fusion: Learning Actions Through Questioning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.11513. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Patel, N.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Khorrami, F. CLIPScope: Enhancing Zero-Shot OOD Detection with Bayesian Scoring. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14737. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Hao, W.; Wang, J.C.; Zhang, P.; Polak, P. Every Image Listens, Every Image Dances: Music-Driven Image Animation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.18801. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, W.; Zheng, S.; Pang, L.; Ling, H.; Chen, C. Attention-Enhancing Backdoor Attacks Against BERT-based Models. In Proceedings of the The 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Yang, R.; Wang, X.; Jin, Y.; Li, C.; Lian, J.; Xie, X. Reinforcement subgraph reasoning for fake news detection. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2022; pp. 2253–2262. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, S. Manifold-constrained Gaussian process inference for time-varying parameters in dynamic systems. Statistics and Computing 2023, 33, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Han, X.; Sun, Y.; Yang, S. CATS: Enhancing Multivariate Time Series Forecasting by Constructing Auxiliary Time Series as Exogenous Variables. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.01673. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.; Gao, J.; Dong, G.; Yang, C.; Campbell, B.; Bowman, B.; Zoellner, J.M.; Abdel-Rahman, E.; Boukhechba, M. SRDA: Mobile Sensing based Fluid Overload Detection for End Stage Kidney Disease Patients using Sensor Relation Dual Autoencoder. In Proceedings of the Conference on Health, Inference, and Learning. PMLR; 2023; pp. 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Datta, D.; Dong, G.; Cai, L.; Boukhechba, M.; Barnes, L. Leveraging mobile sensing and bayesian change point analysis to monitor community-scale behavioral interventions: A case study on covid-19. ACM Transactions on Computing for Healthcare 2022, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Cai, L.; Kumar, S.; Datta, D.; Barnes, L.E.; Boukhechba, M. Detection and analysis of interrupted behaviors by public policy interventions during COVID-19. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM Conference on Connected Health: Applications, Systems and Engineering Technologies (CHASE). IEEE; 2021; pp. 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Gao, M.; Xiao, J.; Liu, C.; Tian, Y.; He, Y. Research and implementation of cancer gene data classification based on deep learning. Journal of Software Engineering and Applications 2023, 16, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chung, Y.A.; Glass, J. Ast: Audio spectrogram transformer. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.01778. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, B.; Polak, P.; Zhang, P. Musechat: A conversational music recommendation system for videos. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024; pp. 12775–12785.

- Liu, X.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, P. Tackling data bias in music-avqa: Crafting a balanced dataset for unbiased question-answering. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision; 2024; pp. 4478–4487. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, W.; Wang, K.; Fu, Z.; Zhou, L. Let community rules be reflected in online content moderation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.12035. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, T.; Hakkani-Tur, D.; Jin, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, R. Calibrate and Debias Layer-wise Sampling for Graph Convolutional Networks. Transactions on Machine Learning Research.

- Xu, T.; Zhu, R.; Shao, X. On variance estimation of random forests with Infinite-order U-statistics. Electronic Journal of Statistics 2024, 18, 2135–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Polak, P. CP-PINNs: Changepoints Detection in PDEs using Physics Informed Neural Networks with Total-Variation Penalty. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and the Physical Sciences Workshop, NeurIPS 2023; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Polak, P. CP-PINNs: Data-Driven Changepoints Detection in PDEs Using Online Optimized Physics-Informed Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on AI, Science, Engineering, and Technology (AIxSET). IEEE; 2024; pp. 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F.; Guillot, K.; Crawford, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Tzeng, N. An Open and Large-Scale Dataset for Multi-Modal Climate Change-aware Crop Yield Predictions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD); 2024; pp. 5375–5386. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F.; Crawford, S.; Guillot, K.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, X.; et al. MMST-ViT: Climate Change-aware Crop Yield Prediction via Multi-Modal Spatial-Temporal Vision Transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023; pp. 5751–5761. [Google Scholar]

- Papanicolaou, A.; Fu, H.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Healy, B.; Khorrami, F. An optimal control strategy for execution of large stock orders using long short-term memory networks. Journal of Computational Finance 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanicolaou, A.; Fu, H.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Khorrami, F. A Deep Neural Network Algorithm for Linear-Quadratic Portfolio Optimization With MGARCH and Small Transaction Costs. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 16774–16792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Sarangi, P.K.; Verma, R. A systematic review of stock market prediction using machine learning and statistical techniques. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 49, 3187–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, H.; Gonon, L.; Teichmann, J.; Wood, B. Deep hedging. Quantitative Finance 2019, 19, 1271–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherny, A.; Douady, R.; Molchanov, S. On measuring nonlinear risk with scarce observations. Finance and Stochastics 2010, 14, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coste, C.; Douady, R.; Zovko, I.I. The stressvar: A new risk concept for extreme risk and fund allocation. The Journal of Alternative Investments 2010, 13, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douady, R. Managing the downside of active and passive strategies: Convexity and fragilities. Journal of portfolio management 2019, 46, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrau, T.; Douady, R. Artificial Intelligence for Financial Markets: The Polymodel Approach; Springer Nature, 2022.

- Zhao, S. PolyModel: Portfolio Construction and Financial Network Analysis. PhD thesis, Stony brook University, 2023.

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction; Springer series in statistics, Springer, 2009.

- MRAR Illustrated.

- Morningstar Risk-Adjusted Return.

- The Morningstar Rating for Funds.

- Coste, C.; Douady, R.; Zovko, I.I. The StressVaR: A New Risk Concept for Superior Fund Allocation. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0911.4030. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, C.; Chen, W.; Ma, Z.; Yan, J.; Sun, L. Transformers in time series: A survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.07125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Long, M. itransformer: Inverted transformers are effective for time series forecasting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06625. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer normalization. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.06450. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.; Kim, J.; Tae, Y.; Park, C.; Choi, J.H.; Choo, J. Reversible instance normalization for accurate time-series forecasting against distribution shift. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Non-stationary transformers: Exploring the stationarity in time series forecasting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 9881–9893. [Google Scholar]

- Siqiao, Z.; Dan, W.; Raphael, D. Using Machine Learning Technique to Enhance the Portfolio Construction Based on PolyModel Theory. Research in Options 2023 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vuletić, M.; Prenzel, F.; Cucuringu, M. Fin-gan: Forecasting and classifying financial time series via generative adversarial networks. Quantitative Finance 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedge Fund Research, https://www.hfr.com/hfri-indices-index-descriptions.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).