Submitted:

18 September 2024

Posted:

18 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect colonies

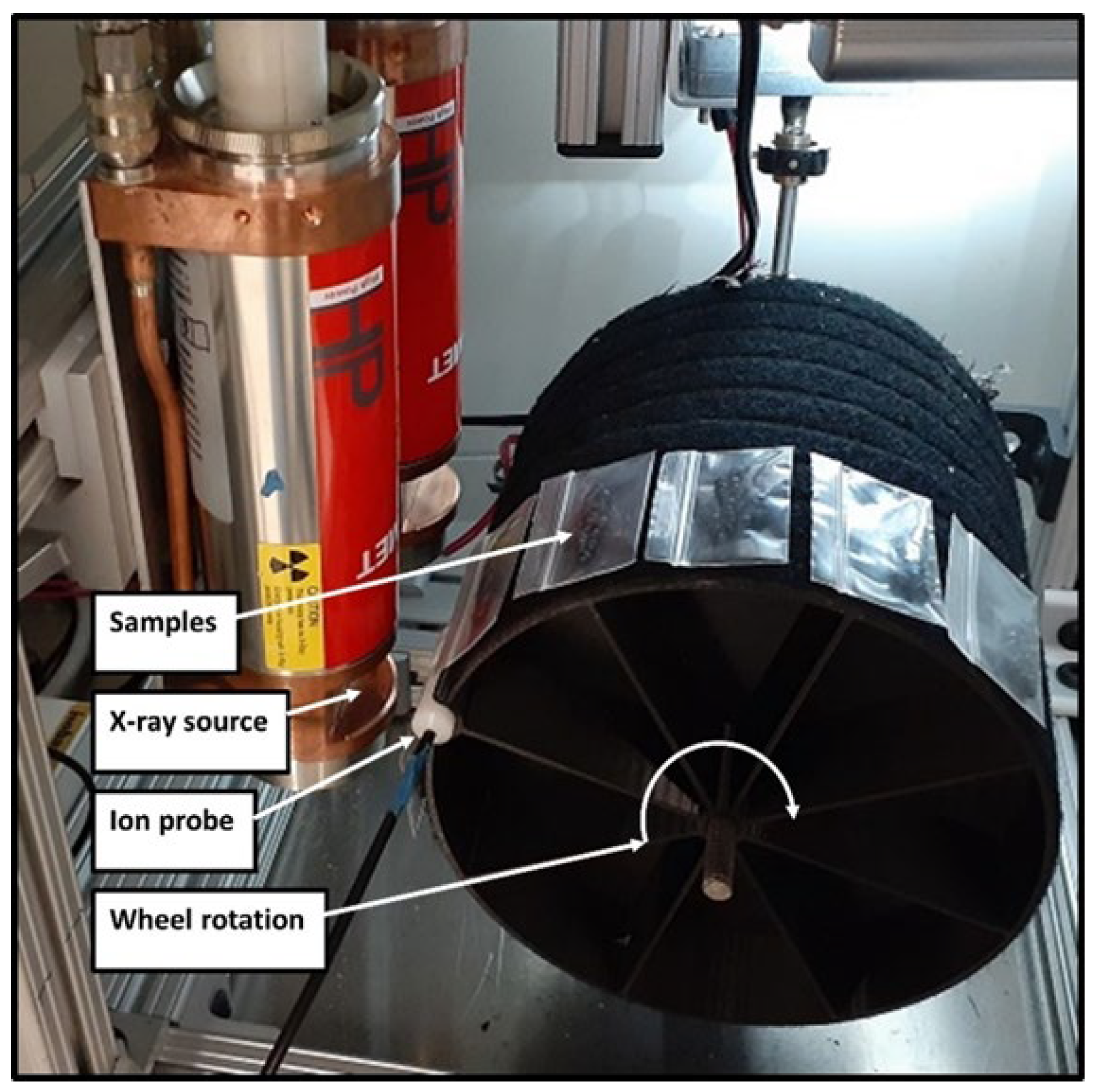

2.2. Irradiation Process

2.3. Effect of X-Ray Irradiation on Egg Eclosion

2.4. Effect of Egg Age on Radiosensitivity

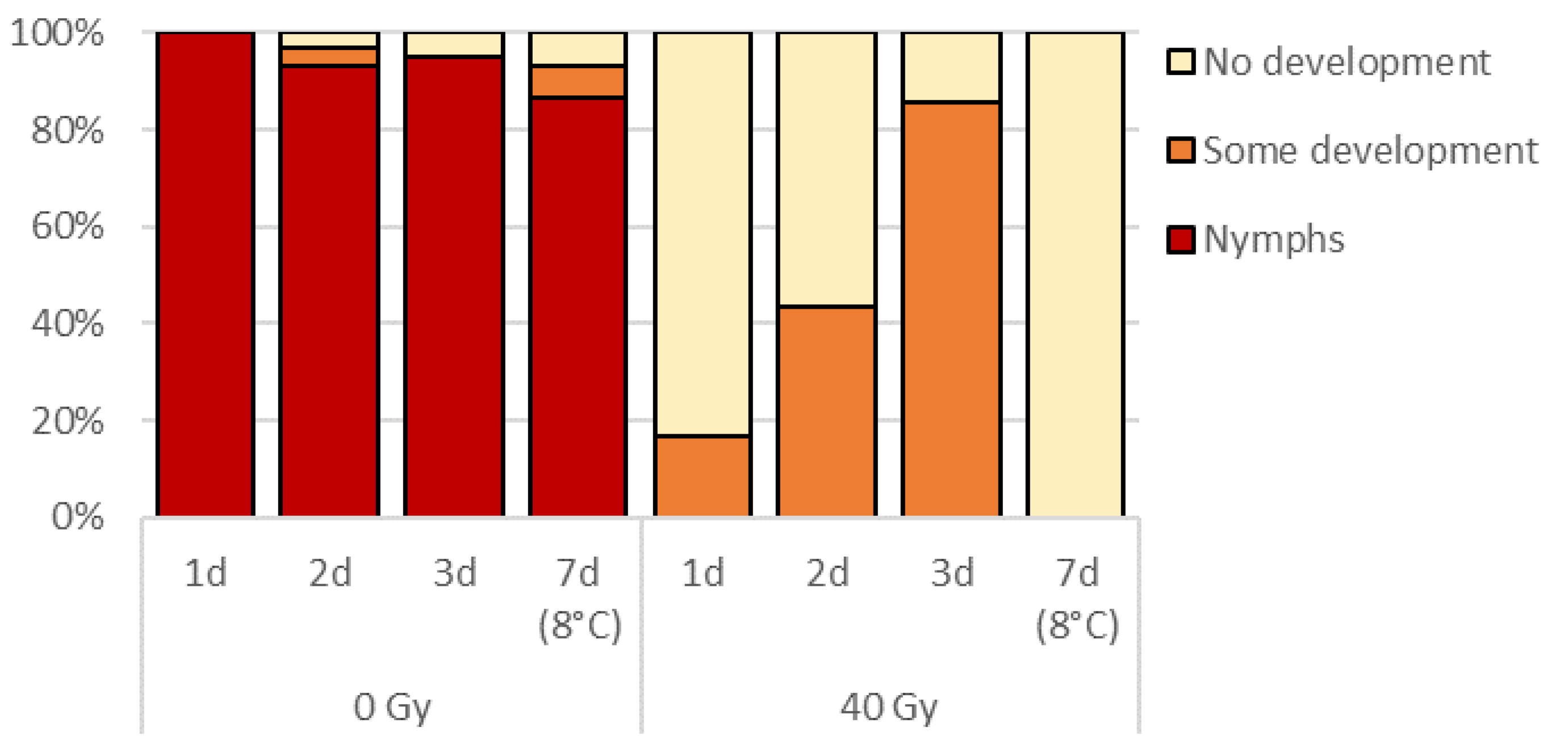

2.5. Suitability of Irradiated Eggs for Parasitoid Development

2.6. Parasitoid preference

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

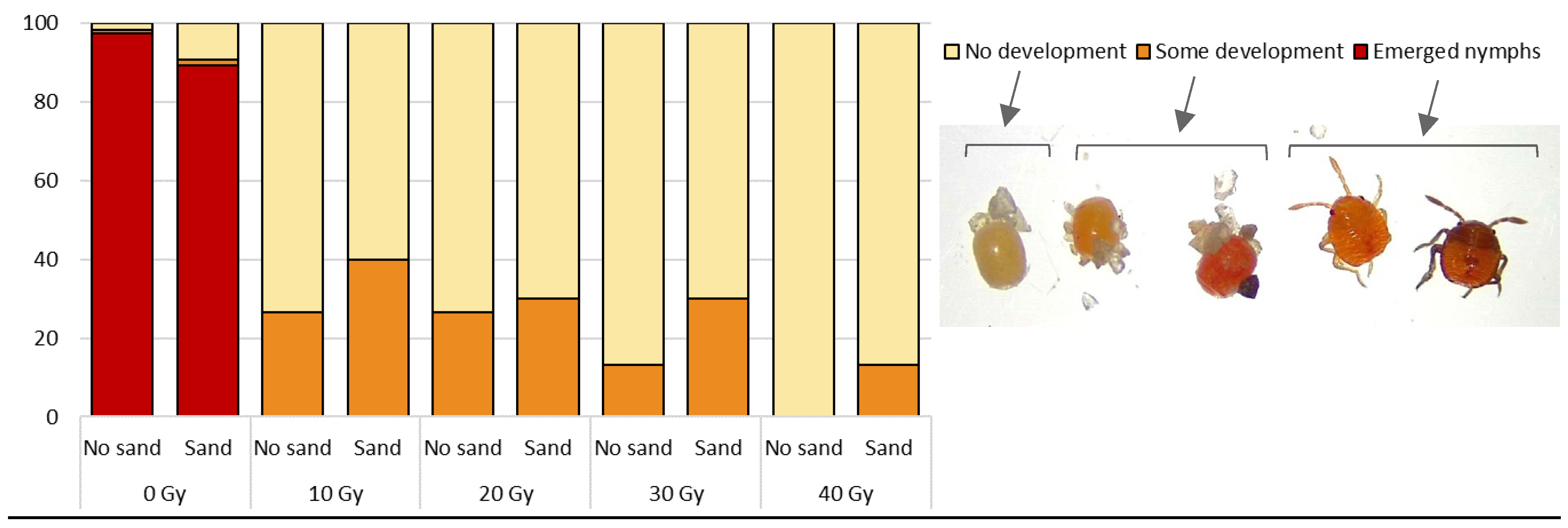

3.1. Effect of X-Ray Irradiation on Egg Eclosion

3.2. Effect of Egg Age on Radiosensitivity

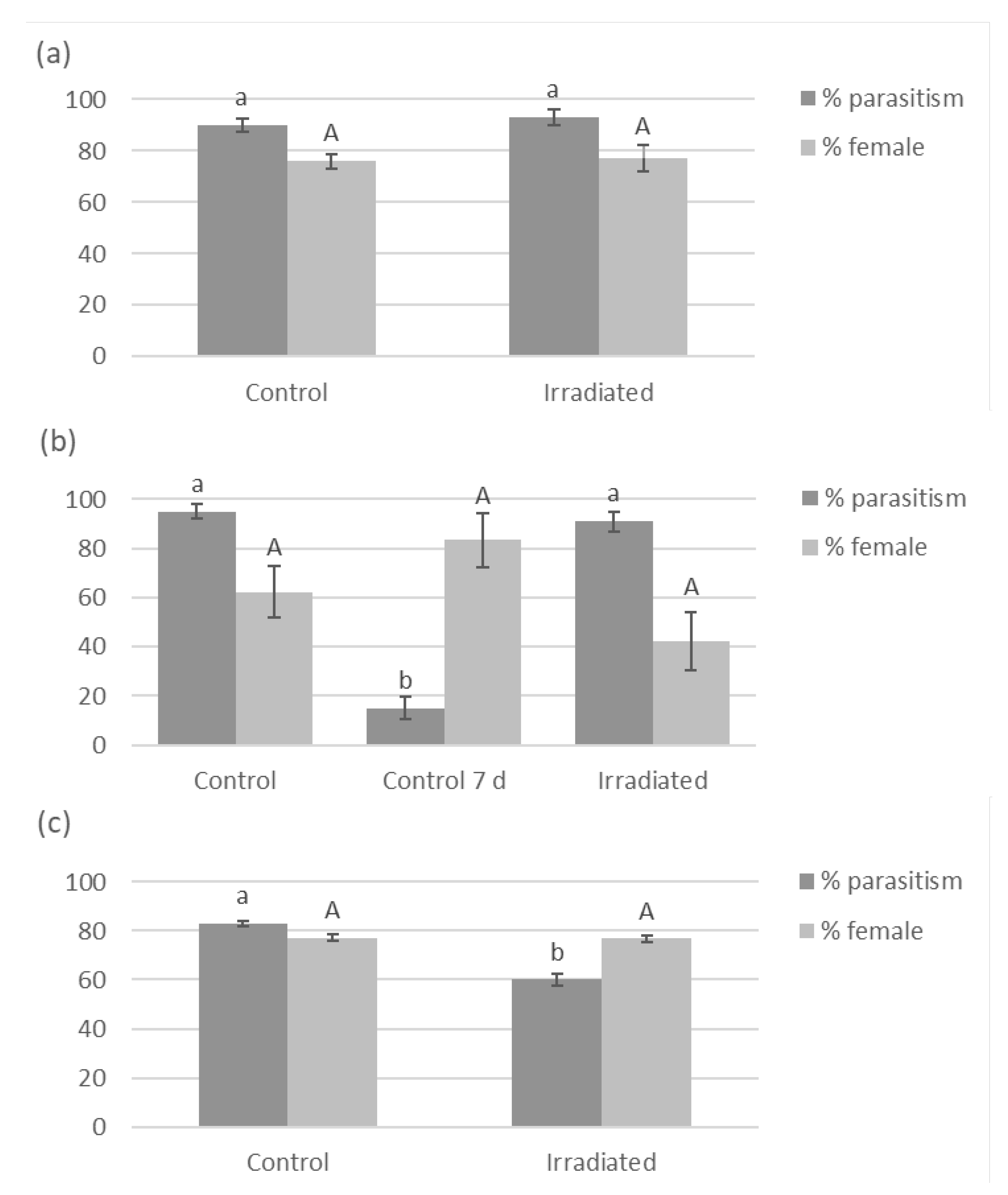

3.3. Suitability of Irradiated Eggs for Parasitoid Development

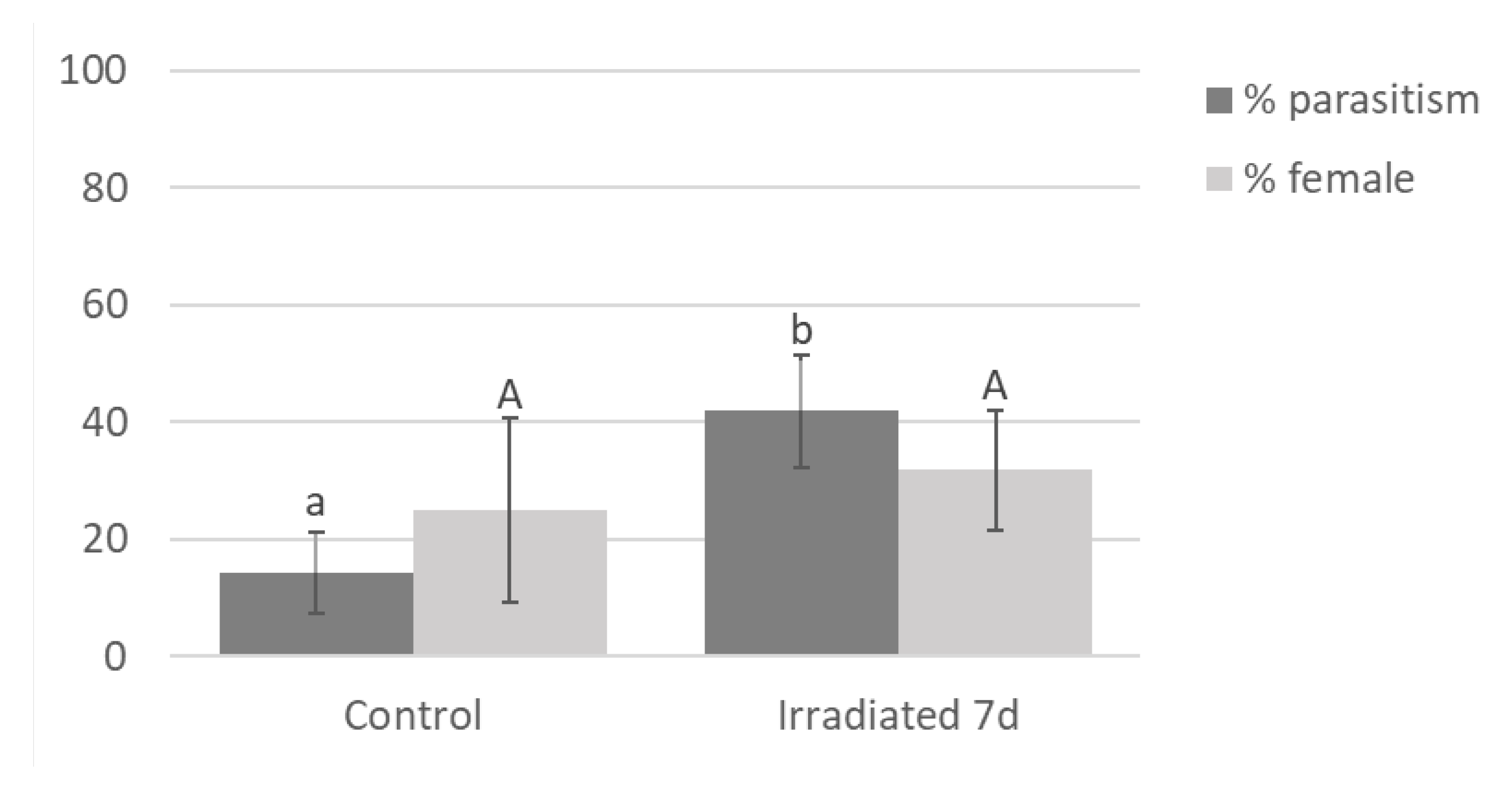

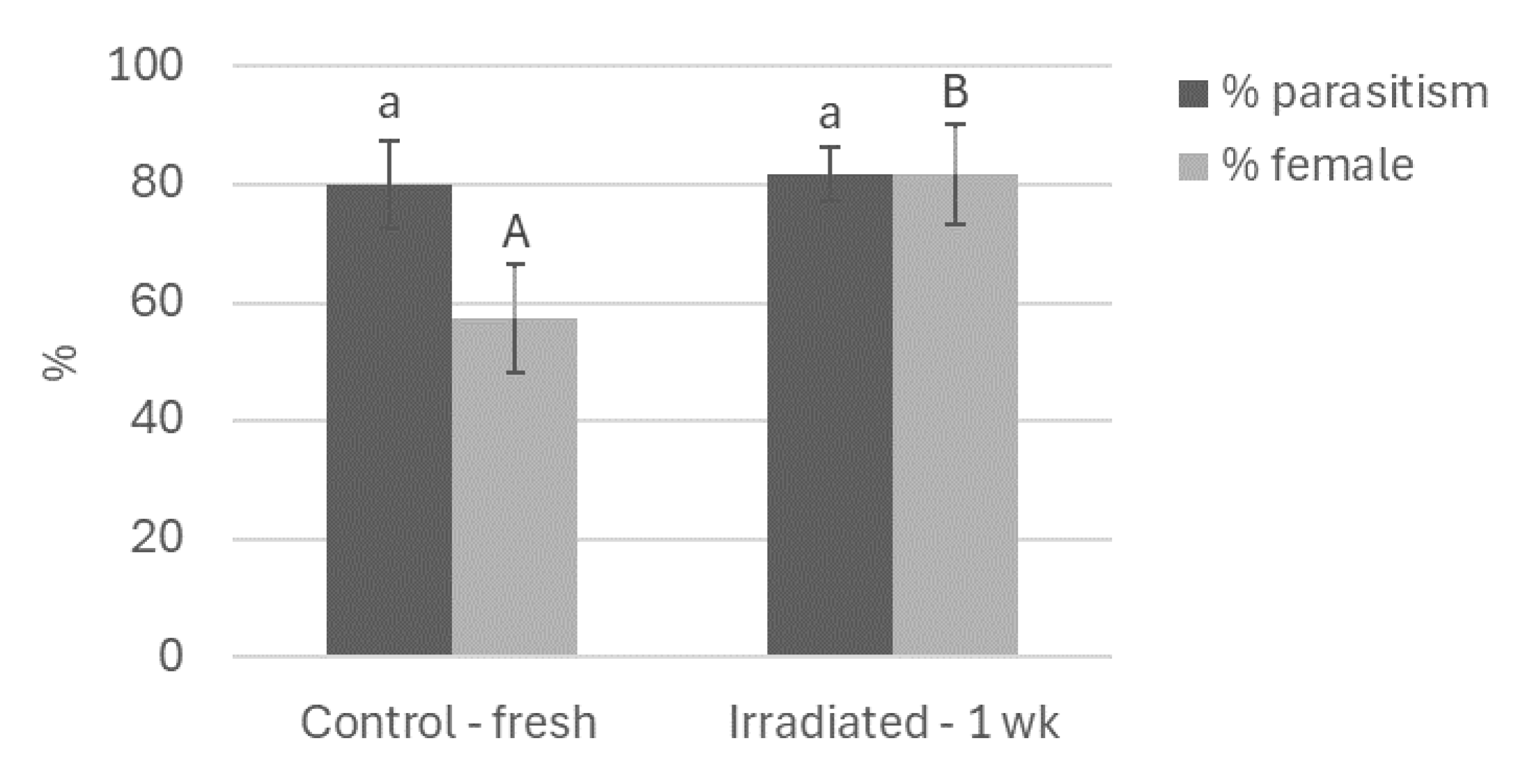

3.4. Parasitoid Preference

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heimpel, G.E.; Mills, N.J. Biological control; Cambridge University Press: 2017.

- van Lenteren, J.C. Implementation of biological control. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 1988, 3, 102-109.

- Lee, D.-H.; Short, B.D.; Joseph, S.V.; Bergh, J.C.; Leskey, T.C. Review of the biology, ecology, and management of Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. Env. Entomol. 2013, 42, 627-641.

- Mahmood, R.; Jones, W.A.; Bajwa, B.E.; Rashid, K. Egg parasitoids from Pakistan as possible classical biological control agents of the invasive pest Bagrada hilaris (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). J. Entomol. Sci. 2015, 50, 147-149. [CrossRef]

- Conti, E.; Avila, G.; Barratt, B.; Cingolani, F.; Colazza, S.; Guarino, S.; Hoelmer, K.; Laumann, R.A.; Maistrello, L.; Martel, G. Biological control of invasive stink bugs: Review of global state and future prospects. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2021, 169, 28-51. [CrossRef]

- Ademokoya, B.; Athey, K.; Ruberson, J. Natural enemies and biological control of stink bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) in North America. Insects 2022, 13, 932. [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.L.; Jennings, D.E.; Hooks, C.R.; Shrewsbury, P.M. Sentinel eggs underestimate rates of parasitism of the exotic brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys. Biol. Control 2014, 78, 61-66. [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, M.L.; Dieckhoff, C.; Vinyard, B.T.; Hoelmer, K.A. Parasitism and predation on sentinel egg masses of the brown marmorated stink bug (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in three vegetable crops: importance of dissections for evaluating the impact of native parasitoids on an exotic pest. Env, Entomol. 2016, nvw134. [CrossRef]

- Costi, E.; Haye, T.; Maistrello, L. Surveying native egg parasitoids and predators of the invasive Halyomorpha halys in Northern Italy. J. Appl. Entomol. 2019, 143, 299-307. [CrossRef]

- Tillman, G.; Toews, M.; Blaauw, B.; Sial, A.; Cottrell, T.; Talamas, E.; Buntin, D.; Joseph, S.; Balusu, R.; Fadamiro, H. Parasitism and predation of sentinel eggs of the invasive brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Stål)(Hemiptera: Pentatomidae), in the southeastern US. Biol. Control 2020, 145, 104247. [CrossRef]

- Ganjisaffar, F.; Talamas, E.J.; Bon, M.C.; Perring, T.M. First report and integrated analysis of two native Trissolcus species utilizing Bagrada hilaris eggs in California. J. Hymenopt. Res. 2020, 80, 49-70. [CrossRef]

- Hogg, B.N.; Grettenberger, I.M.; Borkent, C.J.; Stokes, K.; Zalom, F.G.; Pickett, C.H. Natural biological control of Bagrada hilaris by egg predators and parasitoids in north-central California. 2022, 171, 104942. [CrossRef]

- Tillman, G.; Cottrell, T.; Balusu, R.; Fadamiro, H.; Buntin, D.; Sial, A.; Vinson, E.; Toews, M.; Patel, D.; Grabarczyk, E. Effect of duration of deployment on parasitism and predation of Halyomorpha halys (Stål)(Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) sentinel egg masses in various host plants. Fla. Entomol. 2022, 105, 44-52. [CrossRef]

- Herlihy, M.V.; Talamas, E.J.; Weber, D.C. Attack and success of native and exotic parasitoids on eggs of Halyomorpha halys in three Maryland habitats. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0150275.

- Federico, R.P.; Francesco, B.; Leonardo, M.; Elena, C.; Lara, M.; Giuseppino, S.P. Searching for native egg-parasitoids of the invasive alien species Halyomorpha halys Stål (Heteroptera Pentatomidae) in Southern Europe. J. Zool. 2016, 99, 1-8.

- Power, N.; Ganjisaffar, F.; Xu, K.; Perring, T.M. Effects of parasitoid age, host egg age, and host egg freezing on reproductive success of Ooencyrtus mirus (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) on Bagrada hilaris (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) eggs. Env. Entomol. 2021, 50, 58-68.

- Cantón-Ramos, J.M.; Callejón Ferre, Á.J. Raising Trissolcus basalis for the biological control of Nezara viridula in greenhouses of Almeria (Spain). Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 5, 3207-3212.

- Haye, T.; Fischer, S.; Zhang, J.; Gariepy, T. Can native egg parasitoids adopt the invasive brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae), in Europe? J. Pest Sci. 2015, 88, 693-705. [CrossRef]

- Martel, G.; Auge, M.; Talamas, E.; Roche, M.; Smith, L.; Sforza, R.F.H. First laboratory evaluation of Gryon gonikopalense (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae), as potential biological control agent of Bagrada hilaris (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). Biol. Control 2019, 135, 48-56. [CrossRef]

- Egwuatu, R.; Taylor, T.A. Development of Gryon gnidus (Nixon)(Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) in eggs of Acanthomia tomentosicollis (Stål)(Hemiptera: Coreidae) killed either by gamma irradiation or by freezing. Bull. Entom. res. 1977, 67, 31-33. [CrossRef]

- Morandin, L.A.; Long, R.F.; Kremen, C. Hedgerows enhance beneficial insects on adjacent tomato fields in an intensive agricultural landscape. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 189, 164-170. [CrossRef]

- Dyck, V.A.; Hendrichs, J.; Robinson, A.S. Sterile insect technique: principles and practice in area-wide integrated pest management; Taylor & Francis: 2021.

- Roselli, G.; Anfora, G.; Sasso, R.; Zapponi, L.; Musmeci, S.; Cemmi, A.; Suckling, D.M.; Hoelmer, K.A.; Ioriatti, C.; Cristofaro, M. Combining Irradiation and Biological Control against Brown Marmorated Stink Bug: Are Sterile Eggs a Suitable Substrate for the Egg Parasitoid Trissolcus japonicus? Insects 2023, 14, 654.

- Kohli, A.K. Gamma Irradiator Technology: Challenges and Future Prospects. Univers. J. Appl. Sci. 2018, 12, 47-51. [CrossRef]

- Mastrangelo, T.; Parker, A.G.; Jessup, A.; Pereira, R.; Orozco-Dávila, D.; Islam, A.; Dammalage, T.; Walder, J.M.M. A New Generation of X Ray Irradiators for Insect Sterilization. J. Econ. Entomol. 2010, 103, 85-94. [CrossRef]

- Kaboré, B.A.; Nawaj, A.; Maiga, H.; Soukia, O.; Pagabeleguem, S.; Ouédraogo/Sanon, M.S.G.; Vreysen, M.J.; Mach, R.L.; De Beer, C.J. X-rays are as effective as gamma-rays for the sterilization of Glossina palpalis gambiensis Vanderplank, 1911 (Diptera: Glossinidae) for use in the sterile insect technique. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17633. [CrossRef]

- Congress.gov. Text - H.R.5515 - 115th Congress (2017-2018): An act to authorize appropriations for fiscal year 2019 for military activities of the Department of Defense, for military construction, and for defense activities of the Department of Energy, to prescribe military personnel strengths for such fiscal year, and for other purposes. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/5515/text (accessed on 05/28/2024).

- Bundy, C.S.; Grasswitz, T.R.; Sutherland, C. First report of the invasive stink bug Bagrada hilaris (Burmeister) (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) from New Mexico, with notes on its biology. Southwest Entomol. 2012, 37, 411-414, doi:. [CrossRef]

- Reed, D.A.; Palumbo, J.C.; Perring, T.M.; May, C. Bagrada hilaris (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae), an invasive stink bug attacking cole crops in the southwestern United States. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2013, 4, C1-C7, doi: . [CrossRef]

- Torres-Acosta, R.I.; Sánchez-Peña, S.R. Geographical distribution of Bagrada hilaris (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in Mexico. J. Entomol. Sci. 2016, 51, 165-167. [CrossRef]

- Faúndez, E.I. From agricultural to household pest: The case of the painted bug Bagrada hilaris (Burmeister)(Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) in Chile. J. Med. Entomol. 2018, 55, 1365-1368. [CrossRef]

- Colazza, S.; Guarino, S.; Peri, E. Bagrada hilaris (Burmeister)(Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) a pest of capper in the island of Pantelleria [Capparis spinosa L.; Sicily]. Inf. Fitopatol. 2004, 54.

- Palumbo, J.C.; Perring, T.M.; Millar, J.G.; Reed, D.A. Biology, ecology, and management of an invasive stink bug, Bagrada hilaris, in North America. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2016, 61, 453-473. [CrossRef]

- Stark, J.D.; Banks, J.E. Population-level effects of pesticides and other toxicants on arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2003, 48, 505-519.

- Taylor, M.E.; Bundy, C.S.; McPherson, J.E. Unusual ovipositional behavior of the stink bug Bagrada hilaris (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2014, 107, 872-877. [CrossRef]

- Tofangsazi, N.; Hogg, B.N.; Hougardy, E.; Stokes, K.; Pratt, P.D. Host searching behavior of Gryon gonikopalense and Trissolcus hyalinipennis (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae), two candidate biological control agents for Bagrada hilaris (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). 2020, 151, 104397.

- Hogg, B.N.; Hougardy, E.; Talamas, E. Adventive Gryon aetherium Talamas (Hymenoptera, Scelionidae) associated with eggs of Bagrada hilaris (Burmeister)(Hemiptera, Pentatomidae) in the USA. J. Hymenopt. Res. 2021, 87, 481.

- Martel, G.; Sforza, R.F. Evaluation of three cold storage methods of Bagrada hilaris (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) and the effects of host deprivation for an optimized rearing of the biocontrol candidate Gryon gonikopalense (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae). Biol. Control 2021, 163, 104759. [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M. Effects of gamma radiation on the Mediterranean flour moth, Ephestia kuehniella, eggs and acceptability of irradiated eggs by Trichogramma cacoeciae females. J. Pest Sci. 2010, 83, 243-249. [CrossRef]

- Haff, R.; Jackson, E.; Gomez, J.; Light, D.; Follett, P.; Simmons, G.; Higbee, B. Building lab-scale x-ray tube based irradiators. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2016, 121, 43-49. [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.-S.; Haff, R.P.; Ovchinnikova, I.; Light, D.M.; Mahoney, N.E.; Kim, J.H. Curcumin and quercetin as potential radioprotectors and/or radiosensitizers for X-ray-based sterilization of male navel orangeworm larvae. 2019, 9, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Hougardy, E.; Hogg, B.N. Host patch use and potential competitive interactions between two egg parasitoids from the family Scelionidae, candidate biological control agents of Bagrada hilaris (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 611-619. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, M.; Jalali, M.A.; Michaud, J.; Ziaaddini, M.; Hashemirad, H. Multiparasitism of stink bug eggs: competitive interactions between Ooencyrtus pityocampae and Trissolcus agriope. 2014, 59, 279-286. [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023.

- Ozyardimci, B.; Cetinkaya, N.; Denli, E.; Ic, E.; Alabay, M. Inhibition of egg and larval development of the Indian meal moth Plodia interpunctella (Hübner) and almond moth Ephestia cautella (Walker) by gamma radiation in decorticated hazelnuts. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2006, 42, 183-196. [CrossRef]

- Ayvaz, A.; Albayrak, S.; Karaborklu, S. Gamma radiation sensitivity of the eggs, larvae and pupae of Indian meal moth Plodia interpunctella (Hübner)(Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 505-512.

- Donoughe, S. Insect egg morphology: evolution, development, and ecology. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2022, 50, 100868. [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J. Parasitoids: behavioral and evolutionary ecology; Princeton University Press: 1994.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).