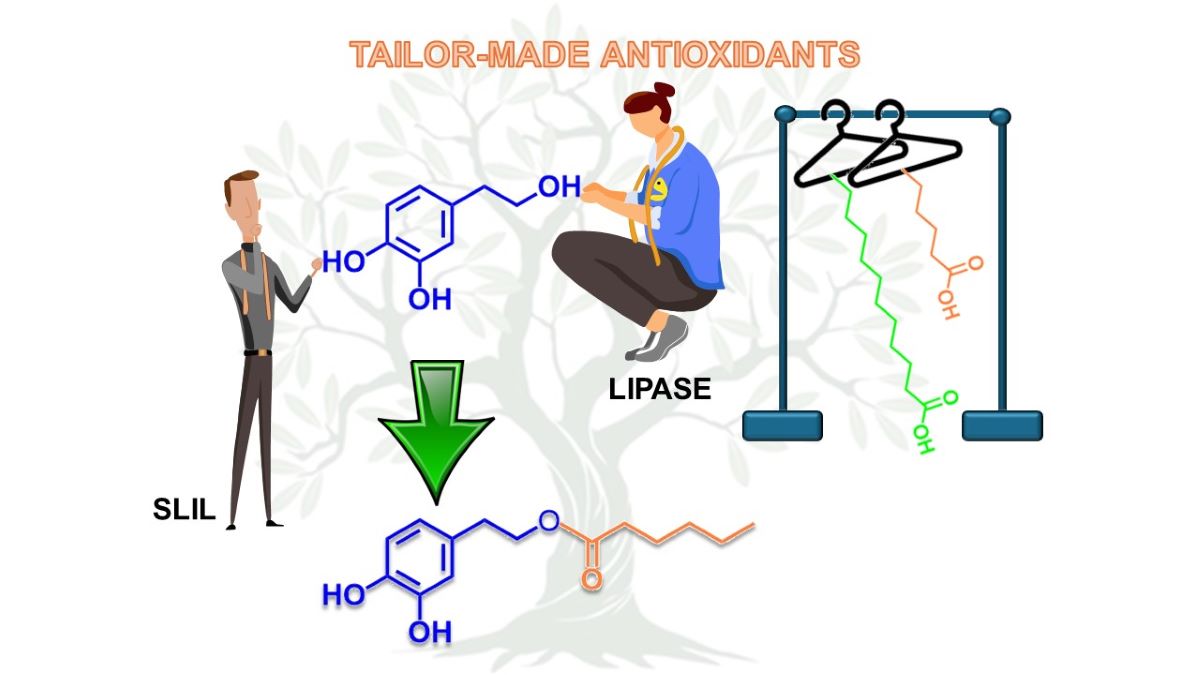

2.1. Suitability of IL-Lipase Combined Tools for the Esterification of FFAs with HT

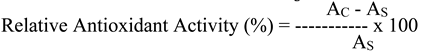

The biocatalytic esterification of two substrates mutually immiscible, such as an aromatic alcohol, like HT and a FFA as acyl donor, may be considered the main handicap for a good performance, which is usually overcome by using chemical derivatives of substrates [

26], or a great excess of inert solvents [

27] to facilitate the reaction. By using ILs, many biocatalytic esterification reactions have been successfully carried out, where the easy recovery for reuse of this solvent was the main flag of greenness. As representative example, the hexanoic acid (Hex) was selected as acyl donor to carry out the biocatalytic esterification with HT by using a 1:4 HT:Hex molar ratio in the SLIL [C

12mim][NTf

2] green solvent. After the addition of the immobilized

C. antarctica lipase B Novozym 435 (N435) (400 mg/mmol HT), the mixture was incubated at 80

oC under magnetic stirring, where the presence of the MS 13X dehydrating agent allowed to shift the reaction equilibrium towards the synthetic side by withdrawing the released water by-product. Under these conditions the hydroxytyrosyl hexanoate (HT-Hex) product was obtained at 87 % yield after 3 h reaction time, as determined by HPLC (see

Table 1, entry 4). The synthesis of the product was also confirmed by ATR-FTIR, revealing the formation of an ester bond through the identification of the C=O stretching by the shift of the vibration band of the carboxyl group from 1704 cm

−1 to 1735 cm

−1, and the detection of a new band at 1238 cm

−1 corresponding to the C-O-C stretching (see

Figure S1). In the same context, the HT-Hex product was identified and characterized by HPLC-MS and

1H-NMR and

13C-NMR analyses, as detailed in Supplementary Material (

Figures S2–S7). The

1H-NMR and

13C-NMR spectra clearly showed that the primary OH group in the alkyl chain is the only one involved in the ester product, confirming the selectivity of the enzymatic esterification.

These results show the convenience of the combination of biocatalysis and SLILs to achieve the efficient esterification of FFAs with HT. While the exquisite selectivity of the enzymes makes this desired transformation simpler and more efficient, the selection of this SLIL as non-aqueous green solvent with an excellent solubilization capacity, permits to significantly reduce its contribution to the mass transfer and improves the reaction rate compared to other organic solvents (see section 2.5,

Table 3, entries 2 and 3).[

16,

20]. Besides, the potential for recovery and reuse of this SLIL is much more interesting from the economic and environmental points of view. Thus, it has been demonstrated that the synergy between the IL and the biocatalysts is fundamental for the efficient modification of natural bioactive compounds following the selectivity and economy criteria. [

19,

20,

21,

22] However, the excellence of this combo IL-biocatalysts can be boosted through the optimization of the reaction conditions, attending to the amount of biocatalyst, the reaction temperature and the molar ratio of substrates.

As can be seen in

Table 1 (entries 1-4), the increase in the enzyme amount from 50 to 400 mg provides a concomitant increase in product yield up to 87 % (see entry 4). However, it should be noted that the productivity of the reaction systems shows a bell-shape profile by increasing the amount of enzyme, being obtained the best results when using 100 mg N435/mmol HT (see entry 3), a value 4-fold higher than that obtained for the highest enzyme content. Reaction temperature was also shown as an important parameter, being observed a clear improvement in product yield (from 47% to 83 %, see entries 2, 5 and 6) when temperature raised from 60 to 80 ºC. This fact was directly related with the improved suitability of the reaction system for dissolving both HT and Hex substrates into the SLIL system, enhancing their transfer rate to the active site of the enzyme while maintaining the enzyme activity by the protective effect of SLIL media.[

20] The ability of hydrophobic SLILs to stabilize enzymes at high temperatures has been widely reported (

e.g. up to 1370 days half-life time at 60ºC in the N-octadecyl-N’,N”,N”’-trimethylammonium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide IL)[

20,

28]. This stabilization is attributed to the preservation of the essential water-shell around the enzyme, as well as the native enzyme conformation into the IL net, which acts as a stabilizing confined space for the biocatalysts. It should be noted that by decreasing the HT:Hex substrates molar ratio to 1:2 mol/mol (see entry 7), both, product yield (76 %) and productivity (2.6 mmol HT-Hex/g N435 h) parameters remained practically similar to those obtained for a 1:4 HT:Hex molar ratio (see entry 2). Consequently, the 1:2 HT-Hex molar ratio was selected for further experiments because of the improvement in green metric parameters of the process (

e.g. atom economy).[

10,

29]

2.2. Biocatalytic Synthesis of HT Monoesters with Different Acyl Chain Length

To analyze the suitability of the N435/[C12mim][NTf2] combo system for the lipophilization of HT, the biocatalytic synthesis of HT monoesters of fatty acids of different alkyl chain length was studied under the optimized reaction conditions.

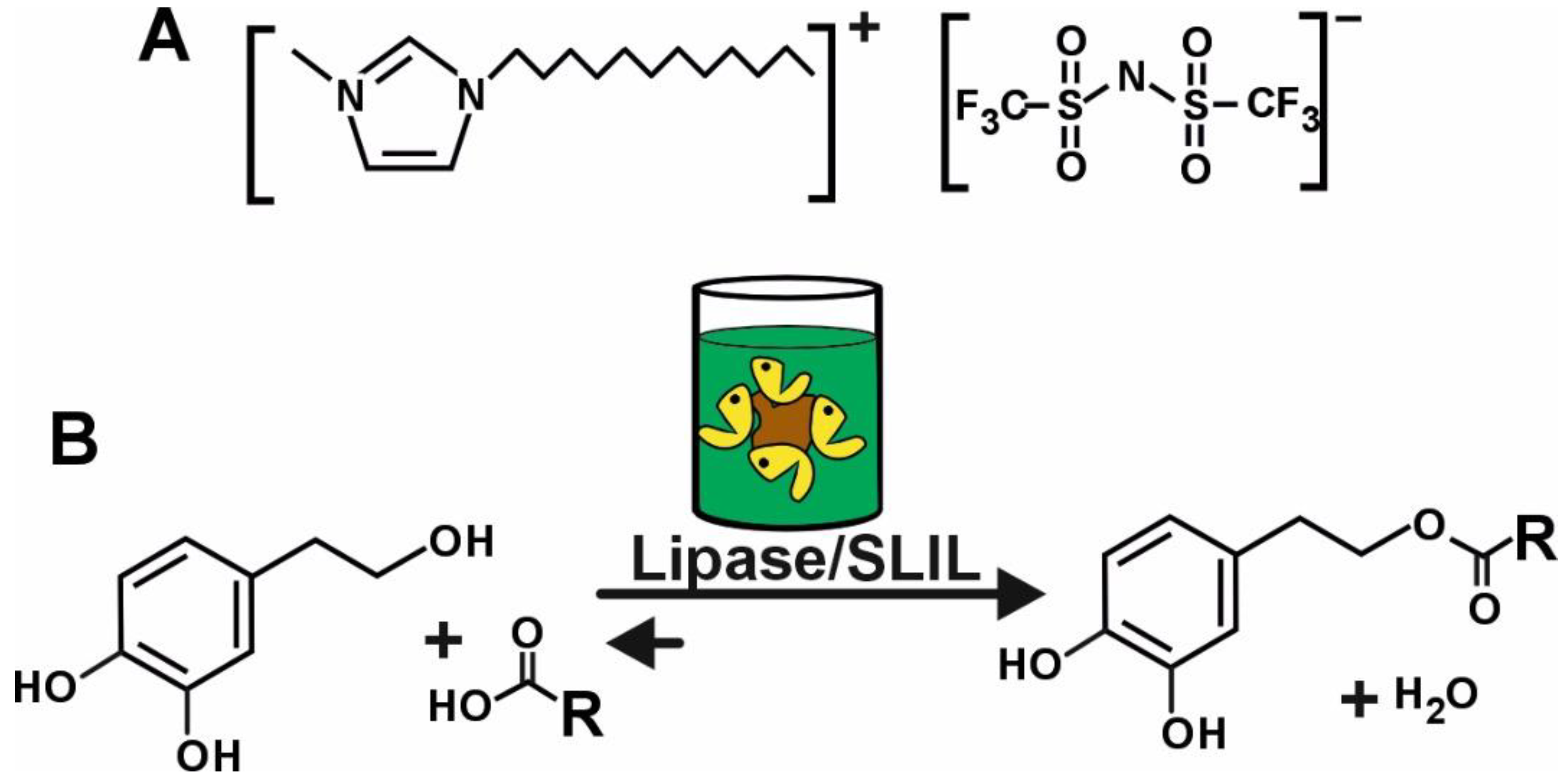

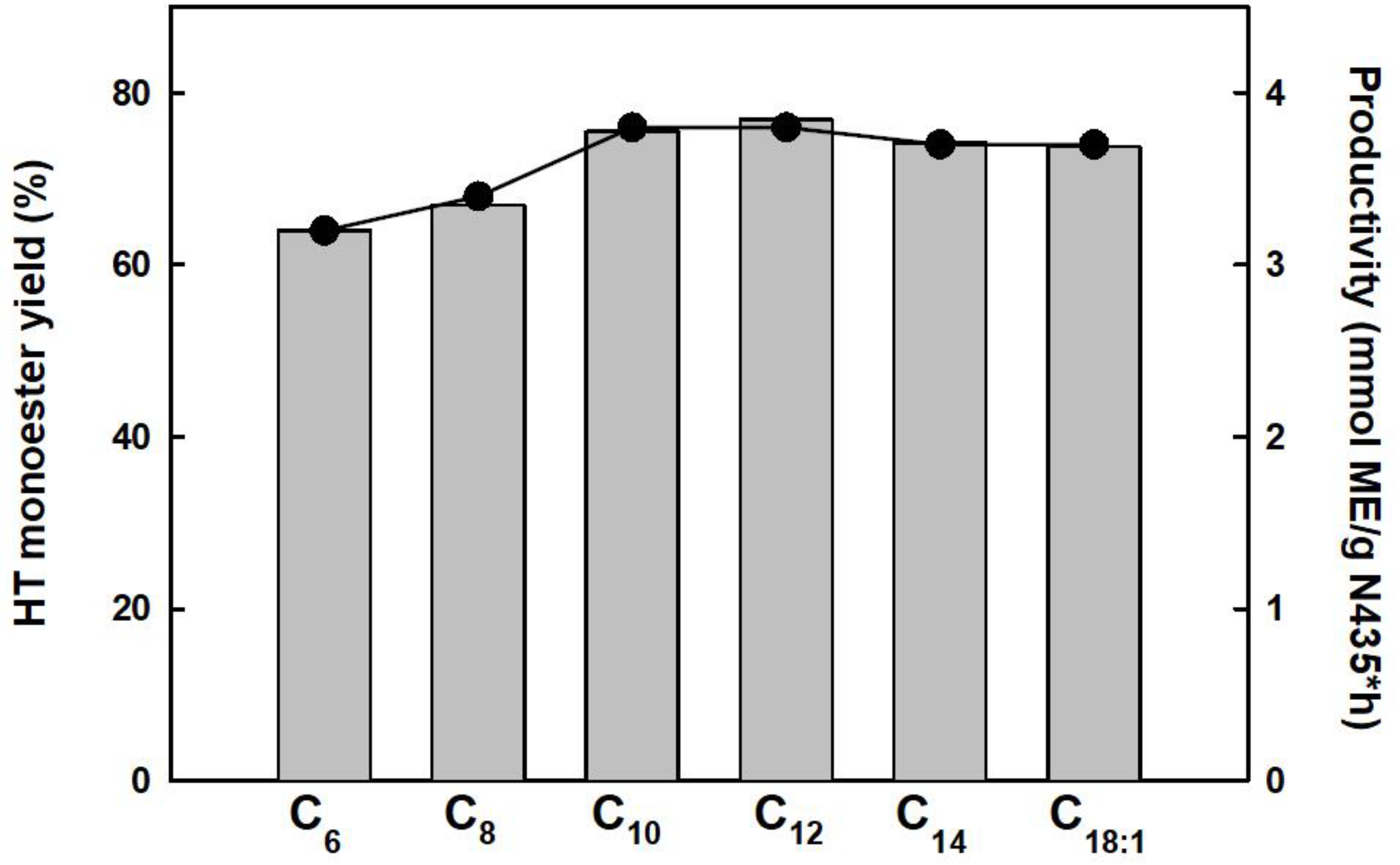

Figure 2 shows the time-course profiles of the N-435-catalyzed direct esterification of hexanoic (C6), octanoic (C8), decanoic (C10), lauric (C12), myristic (C14) or oleic (C18:1) acid with HT using a 1:2 HT: FFA molar ratio at 80 ºC. For all the assayed reaction systems, it should be noted that the immobilized enzyme was able to achieve a product yield higher than 50% within the first 30 minutes, whatever the size of the alkyl chain and being almost completed in 2 h with a slight increase afterwards (

i.e. up to 70-83 % HT-monoester yield after 4 h reaction). The suitability of the proposed approach is also demonstrated when compared with other strategies previously described, where similar yields were achieved after 16 h reaction by using a transesterification synthetic approach in acetonitrile as reaction medium.[

26] According to the profiles in

Figure 2, a reaction time of 2 h was selected as the most appropriate for enzymatically producing HT monoesters attending to the balance between high yield and productivity, as well as to minimize any possible undesired oxidations on HT derivatives induced by heat, that could occur after long reaction times at 80 ºC.

Figure 3 shows the evolution of the HT-monoester product yield and the productivity of the reaction system as a function of the alkyl chain length of the carboxylic acid used for the biocatalytic esterification of HT after 2 h of reaction. Both parameters show a similar behavior being increased with the alkyl chain length from hexanoic (C

6) to lauric (C

12) acids, then remained practically unchanged (

i.e. aprox. 80 % yield and 3.8 mmol HT-monoester/g N435·h) for myristic and oleic acids as the most hydrophobic cases. Once again, these results emphasized the excellent synergies between biocatalysts and SLILs to achieve the efficient and selective lipophilization of aromatic alcohols.[

10,

19] A similar behavior was reported for the N435-catalyzed esterification of FFAs with different alkyl length with glycerol [

21] and panthenol, [

23,

29], where lauric acid also displayed the best performance for both, either in SLIL or solvent-free reaction media. For these hydrophobic SLIL-based reaction media, these results clearly demonstrated that biocatalysts performance in the reaction system is positively influenced by the increase in the alkyl chain length of the acyl donor. This improvement is driven by the hydrophobic interactions between the alkyl chains of both substrates and SLIL, fully aligning with the “like-dissolves-like” principle, which enhances the suitability of the system for biocatalysis.[

19,

28] It is important to note that, despite the excess of acyl donor respect HT and the increased hydrophobicity of the reaction media with all tested FFAs, the degree of selectivity towards the synthesis of HT monoesters is not affected, not detecting diester products that could signify a decrease in the antioxidant activity.

2.3. Scaling Up of the Production of HT-Monohexanoate

To demonstrate the robustness of this procedure, a tempting assay to measure the suitability for scaling-up was carried out by increasing 10-folds the reaction mass with respect to the optimized reaction in

Table 1. Under these conditions the incubation was performed in a reactor with an anchor mechanical stirring, coupled to a vacuum system to remove the water by-product released from the enzymatic reaction.

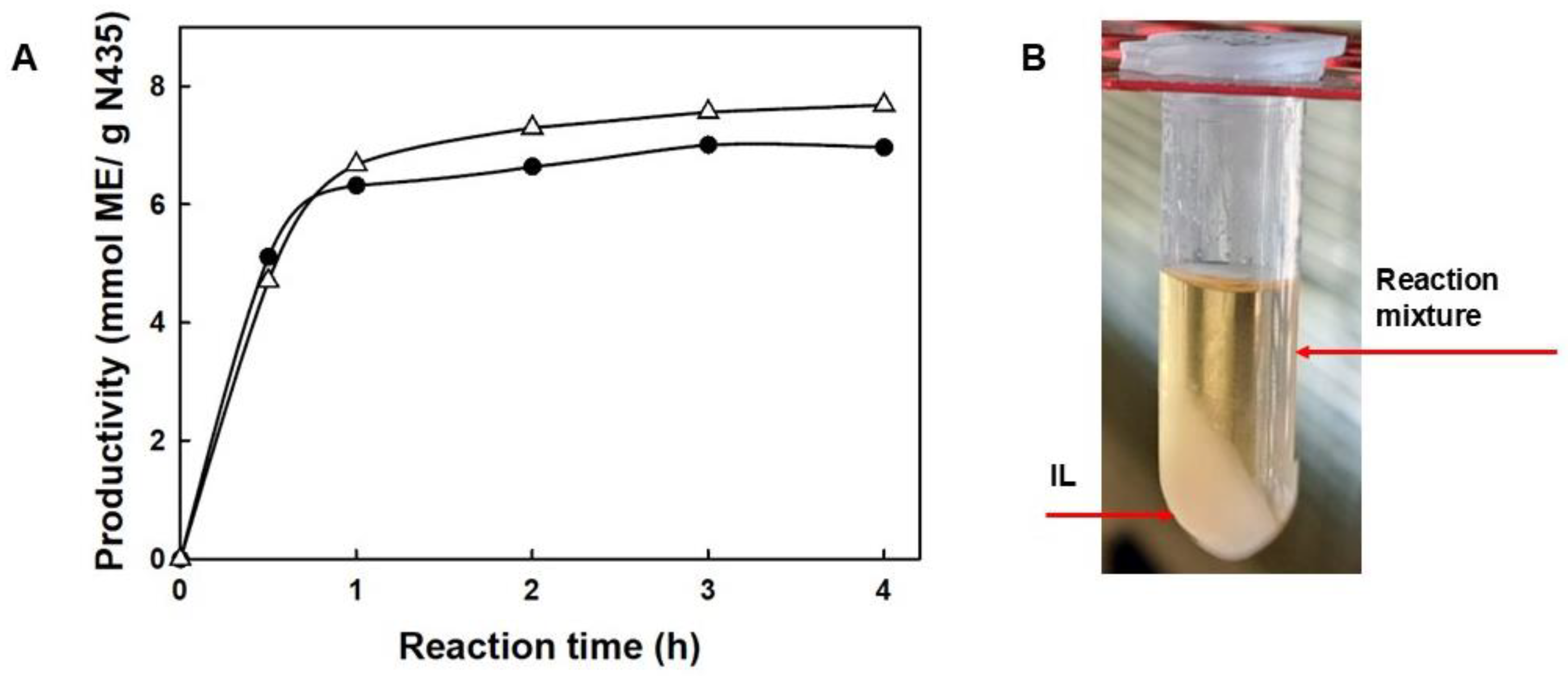

Figure 4A shows the accumulated productivity (in terms of mmol of HT-monohexanoate per gram of N435) for the N435-catalyzed direct esterification of Hex with 0.5 mmol (low scale) or 5 mmol (high scale) HT by using a 1:2 HT:FFA molar ratio in 70% (w/w) [C

12mim][NTf

2] at 80 ºC. The comparison of the time-course profiles reveals similar biocatalytic performance in both scales of synthesis and even, a slight improvement when the reaction mass is increased 10-folds, reaching a value close to 8 mmol HT-monohexanoate/g N435 at 3 h reaction time. This result was attributed to the better suitability of the mechanical anchor stirring for mixing the resulting viscous reaction medium, with respect to the magnetic stirring used for low reaction size. By this approach an adequate mass-transfer rate during the biocatalytic process occurred, as well as an efficient removal of the water by-product produced along the reaction by the vacuum system coupled to the reactor. These results highlight the relevance of the setup as an additional element to the N435/SLIL combo to achieve the best performance. This improvement of the biocatalytic efficiency provided by the suitable set-up at high reaction volumes was also observed, although to a greater extent, for the synthesis of panthenyl monolaurate [

29], and xylityl monolaurate [

30],by direct esterification in solvent free media.

To build green chemical processes, it is necessary to develop integrated approaches for selective (bio)transformation and separation capables of directly providing products, including the recovery for reuse of all the elements of the reaction system (

e.g. biocatalysts, solvents, etc.). The SLILs (

e.g. [C

12mim][NTf

2], etc.) are temperature switchable ionic liquid/solid phases that behave as sponge-like systems that permit to develop straightforward and clean approaches for product separation after the biocatalytic step by a simple protocol of cooling and centrifugation. By this approach, the SLIL precipitates as a solid salt at the bottom, while the products remain in the upper liquid phase, as pure products when they are liquids, or dissolved in another green molecular cosolvent (

e.g. water, etc.) previously added. [

19,

20,

23,

28]

Figure 4B shows the phase behavior of the reaction media resulted from the biocatalytic step for HT-monohexanoate synthesis in [C

12mim][NTf

2] after the addition of five volumes of a (85:15 v/v) propylene glycol: H

2O mixture, then cooling at -10ºC and centrifuged for 10 min, at 0 ºC, 10.000 rpm. As can be seen, this easy protocol permits the full precipitation of the solid SLIL, while the reaction products are extracted in the molecular liquid upper phase, as demonstrated by HPLC analysis that confirmed the recovery of 94 % HT-Hex. Furthermore, the

19F- NMR analysis of the upper liquid phase only detected scarce traces of residual SLIL (up to 1%, see

Figure S8), that could be fully eliminated by other classical procedures (

i.e. ionic exchange column). Because of the solid character of HT and its derivatives, the separation of the HT-monoester product from the SLIL phase needs the addition of a liquid molecular solvent that favor its extraction. Among other molecular solvents, an 85:15 (v/v) propylene glycol: H

2O mixture provides the best precipitation of the solid SLIL after cooling and centrifugation. It should be noted that propylene glycol (PG), meets the specifications of the Food Chemicals Codex (Report Number: 27 NTIS Accession Number: PB265504, 1973) in agreement with the Select Committee on GRAS Substances (SCOGS). [

31] Because of the safety of PG, the extracted mixture containing the HT-monoester could be used without additional steps of purification, contrary to other strategies where the use of volatile organic solvents involves tedious work-ups that also contribute to waste, reducing the greenness of the overall process.

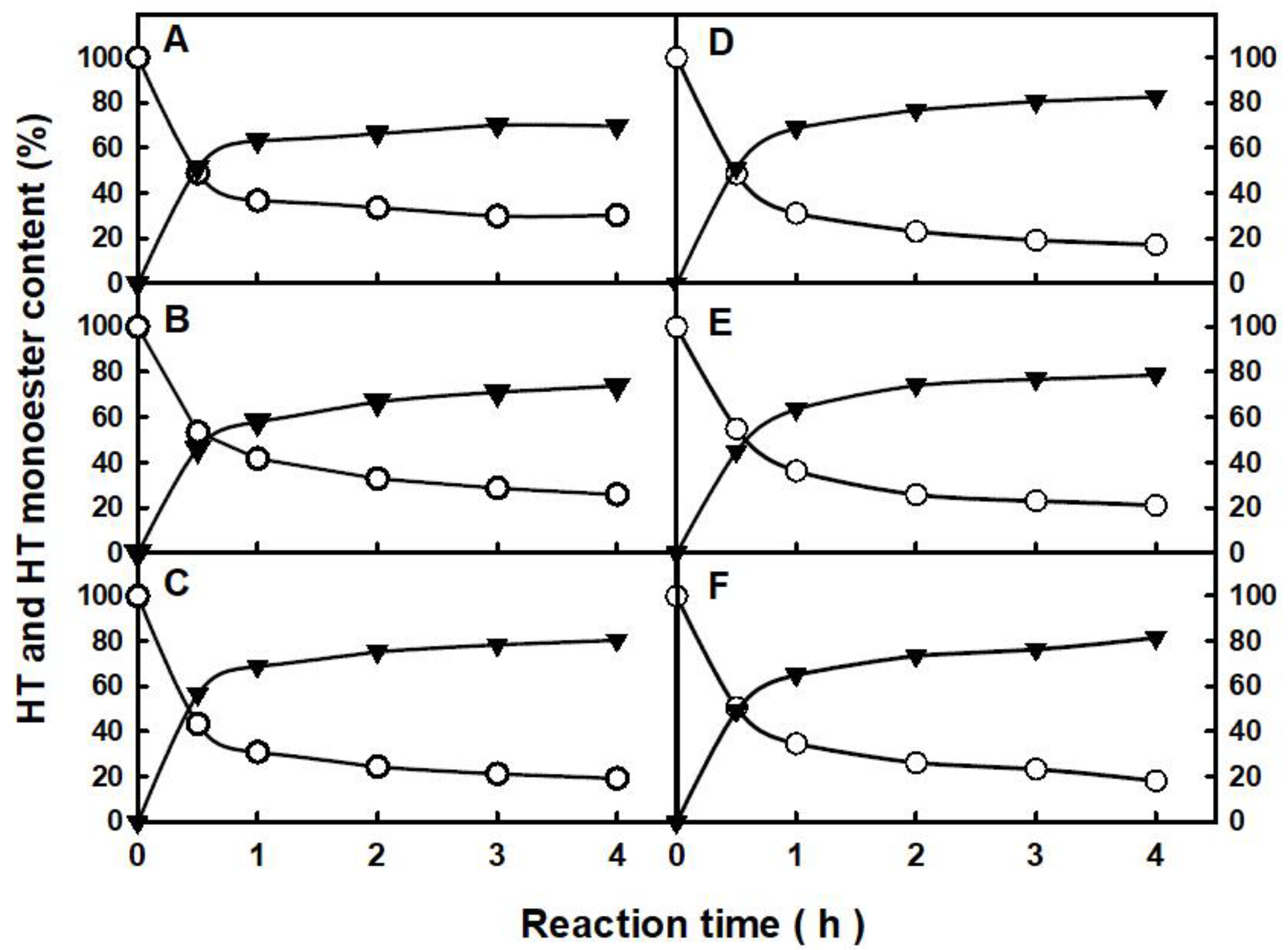

2.4. Antioxidant Activity of the HT-Monoesters

The industrial interest for preparing lipophilized HT derivatives to be used as nutraceutics in hydrophobic-based formulations is fully dependent on the maintenance of the antioxidant power with respect to the free HT. The antioxidant activity of HT and its derivatives after the esterification with different alkyl-chain length FFAs was determined by their capacity to reduce the free radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, which manifests through a color turn from deep purple to pale yellow that can be quantified by Vis-UV spectroscopy at 517 nm. [

10,

32,

33]

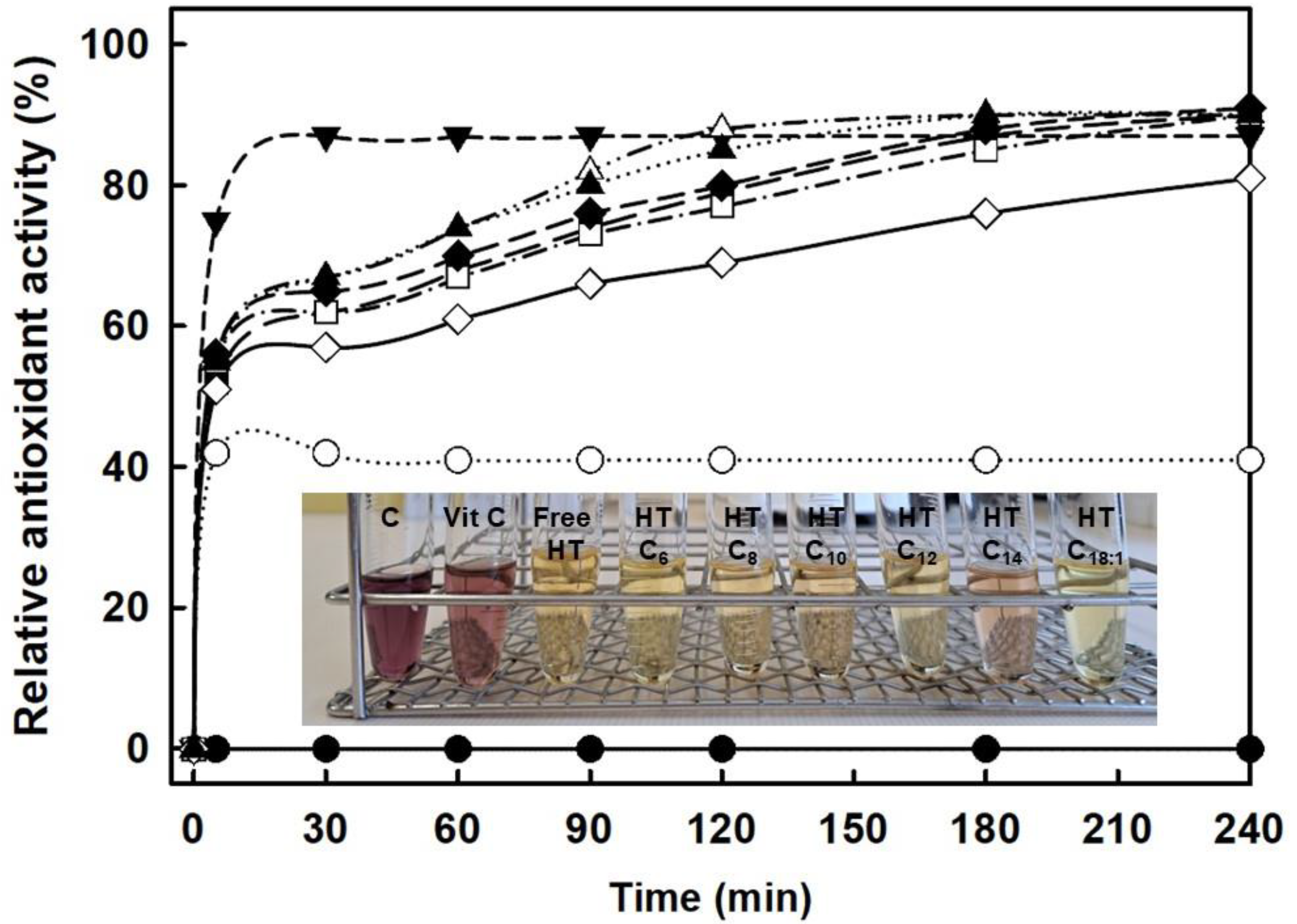

Figure 5 shows the time course profiles of the antioxidant activity of the HT-monoesters based on different alkyl chain length. Firstly, SLIL-free samples were obtained from the reaction media by liquid-liquid extraction, and their respective concentrations were determined by HPLC through a calibration pattern. Free HT and vitamin C (ascorbic acid) were used as control references of the antioxidant activity, and the concentration of all samples was adjusted to 80 nmol for a proper comparison (see Materials and Methods section).

As can be seen, HT and HT-monoesters show relative antioxidant activities ranging from 75 to 88 % after 4 h reaction, values practically twice than that showed by vitamin C (41%), being related to two reductive hydroxyl groups on HT structure with respect to the sole reductive group of vitamin C.[

34] The excellent suitability showed by free HT as natural antioxidant (88 %) agrees with previously reported studies,[

1,

2,

3] even as reductant for precious metal recovery from electronic wastes.[

7]. Furthermore, it should be noted how all the HT-monoesters derivatives maintained the same antioxidant activity regardless the length of the alkyl chain of the FFA. As demonstrated by NMR analysis (see

Figure S7), the ester bond between the FFA and the HT was selectively formed between the carboxylic group of the FFA and the primary hydroxyl group of HT present at the lateral chain, which is not involved in the antioxidant properties of HT. Although the biocatalytic lipophilization of HT provides bioactive molecules with the similar antioxidant power to free HT, it should be noted that the presence of the alkyl chain seems to reduce the reaction rate of DPPH reduction. Thus, while free HT, or vitamin C, reacts immediately with DPPH maintaining unchanged its antioxidant activity with time, the HT-monoester derivatives showed a lower reaction rate of DPPH reduction, being necessary up to 4 h until to reach the maximum level of antioxidant activity (see

Figure 5). This fact was also reported by for the lipophilization of HT,[

27,

35] as well as for other aromatic acids (

e.g. caffeic acid, coumaric, etc.,[

10]), being attributed to a lower ionization of the aromatic hydroxyl groups after the esterification. Other authors report a decay in antioxidant activity after lipophilization, although they recorded the DPPH test only after 10-30 min of incubation reaction, where the steady state has not yet been reached.[

34,

36] Thus, the esterification of FFAs with HT not only improve the miscibility with lipophilic formulations in cosmetics or foods favoring the skin penetration and intestinal absorption, but also the longer reaction time of HT-monoester derivatives could be considered an enhancement in the half-life time of the antioxidant activity in free radicals scavenging.

2.5. Green Metric Assessment of the Biocatalytic Synthesis of HT-Monoesters

To assess the sustainability of the biocatalytic strategy here presented, the synthesis of HT-monohexanoate was selected as representative example of HT-monoesters, and it has been analyzed by means of different recognized green metric parameters

i.e. Atom Economy (AE), Yield (ε), Stoichiometric Factor (SF), Mass Recovery Parameter (MRP), Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) and E-factor parameters, as well as the EcoScale tool. The AE, 1/SF and ε parameters provide information about the reactivity of substrates and atoms incorporated into the desired products. It should be noted that the MRP concerns the recyclability of the reaction species (or their contribution to waste), whereas RME is considered as a global indicator of sustainability comprising all the above parameter. The values of all these parameters range between 0 to 1, corresponding the highest value to the best sustainability. Alternatively, the E-factor parameter may be used as waste quantification criteria, being expected the lowest value for sustainable processes. Related to waste, the Total Carbon Release (TCR) parameter has been designed to quantify the emissions of CO

2 as results from the incineration of waste from organic (waste accumulated in the in the synthesis step) and aqueous (wastewater in the downstream step) residues from the reactions. [

37] And finally, the EcoScale tool permits to extend the sustainable analysis to other criteria, such as the energy expense, the process cost and/or toxicity of reagents, running by introducing different penalties to an initial value of 100% corresponding to the maximum sustainability. [

10,

29] (see Material and Methods and Supplementary Material sections for further details). For an appropriate comparison of these results, the analysis of sustainability has also been extended to other selected strategies of HT esterification for a better understanding of the green metrics dimension. The reaction conditions of all the approaches considered, as well as the results obtained for the E-factor parameter, the TCR and the EcoScale tool, are shown in

Table 3.

The strategies selected are representative examples of different approaches for the biocatalytic esterification of fatty acids (free or derivatized) with HT. Among other conditions, the most relevant differences attend to the use of solvents as reaction medium (entries 2-4), or aliphatic esters, as activated acyl donors for a transesterification reaction mechanism (entries 1 and 2), able to provide homogeneous reaction media suitable for the enzymatic catalysis. It should be noted the higher molar ratio for these transesterification strategies (that produces an alcohol as by-product), while the direct esterification ones using free Hex and HT deal with a more fair molar ratio of substrates (1:2 HT:Hex, entries 3 and 4). In all cases the reaction has been catalyzed by N435, providing excellent yields (75-98 %) but different performances. Thus, a high HT-monoester yield (93%, entry 2) was obtained at the shortest reaction time (1.25 h), leading to the highest value of productivity (5.4 mmol ME/g N435 ∙ h). These results are slightly higher than those here reported by a direct esterification approach (see entry 4, 3.1 mmol HT-monoester/g N435∙h). It can be noted that the use of a very low amount of biocatalyst (entry 3, 33 mg/mmol HT) involves a lengthening in the reaction time up to 48 h for achieving a 75 % HT-monoester yield, being the productivity greatly reduced (0.5 mmol ME/g N435 ∙ h). In this regard, it seems more appropriate to increase the amount of enzyme to improve esterification reaction rates and productivity.

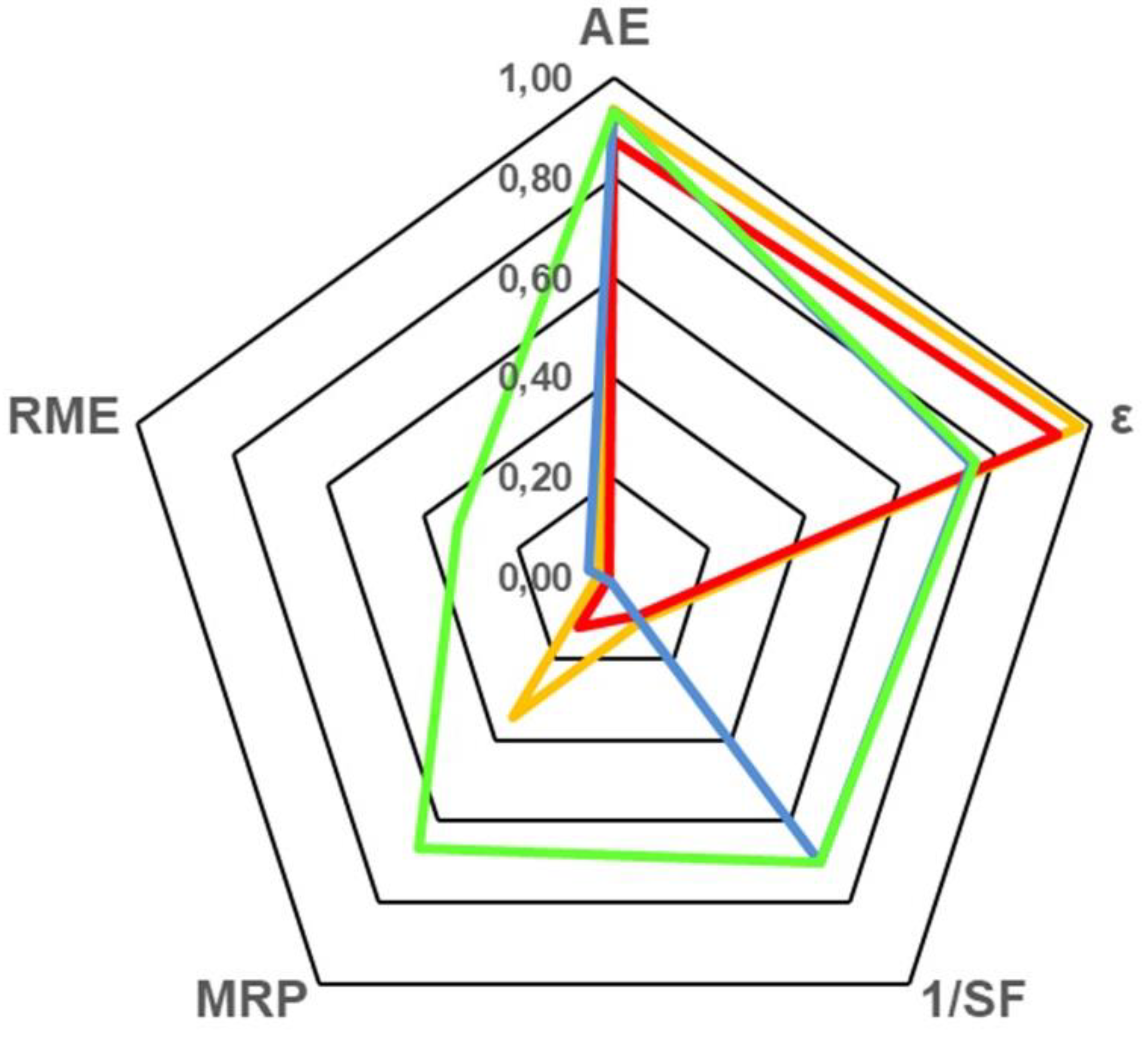

However, the productivity parameter only focuses on reaction efficiency, and other critical aspects regarding the reaction conditions and work-up that provide information on resource use (substrates, energy, solvents, etc.) and waste generation, must also be considered.[

10,

29] Therefore, a complementary sustainability analysis becomes necessary to identify the most efficient approach. In this regard, the ε is complemented with other green parameters like AE, 1/SF, MRP and RME, which are usually represented as the vertices of a pentagon (

Figure 6). Thus, the greenness of the process is shown when a balanced pentagon with a maximum radius of 1 is obtained, as indicated by the highest value for each metric. [

38] It should be emphasized that the calculations of all parameters have been strictly referred to the biocatalytic step.

The AE parameter provides information about the suitability of the strategy selected, revealing the contribution of byproducts to the overall synthesis. As depicted in

Figure 6, the esterification approaches (entries 3 and 4,

Table 3) show the best values as only water is released along the reaction, which mass is negligible respect to the HT ester product. The transesterification strategies (see entries 1 and 2,

Table 3) also show a high AE value despite releasing ethanol or acetaldehyde, respectively, as their molecular weights also becomes practically insignificant respect to that of HT monoester having long alkyl chain. However, since AE does not consider the stoichiometry of the reaction, it is important to determine the 1/SF parameter that quantifies non-used substrates according to the reaction stoichiometry, as they are an important source of waste. As can be seen in

Figure 6, the high excess of acyl donors in entries 1 and 2 results in the lowest 1/SF values (0.1), as opposed to the 1:2 HT: Hex molar ratio used in entries 3 and 4 (0.7 1/SF value). Furthermore, the 1/SF value has a deep impact in the results of the MRP parameter, which accounts for all non-recovered elements after the reaction for further reuse, that directly contribute to waste. This value is even decreased by the used of an organic solvent, as occurs in the strategies using MTBE (entries 2 and 3) which display the lower MRP values. Conversely, the suitability of SLILs to be recovered and reused [

19,

20,

21,

28], together with the fair molar ratio of substrates used in the strategy here reported, leads to the best MRP value (0.66, entry 4), being 66 folds higher than the MRP value of entry 3 (0.01) despite using the same approach in MTBE solvent. This evidences that the selection of the solvent is crucial for the sustainability of processes. The results of all the above green metrics are collected in the RME parameter, giving a landscape of the reaction sustainability. Therefore, whilst the entries 1-3 adopt a triangle or a square shape, only the direct esterification of Hex with HT in SLILs fits more properly to a pentagon and shows the higher radius. The RME value can be indirectly considered an indicator of waste generation, as is related to the E-factor (see formula in

Table S1). Thus, the E-factor parameter (

Table 3) reveals that the best productivity achieved in the entry 2 is at the cost of a large amount of waste, questioning the interest of this approach. This parameter also assigns the lowest value for the entry 4 (2.0) corroborating that the combination of biocatalysis and SLILs provides the best utilization of substrates and reagents with low waste generation. Beyond waste, there is a serious concern about its further contribution to the environmental CO

2 emissions. [

39] For this reason, the TCR parameter permits to calculate the CO

2 emissions after their incineration (considering the worst case scenario) and can be calculated from the E-factor (

i.e. TCR = (PMI organic x 2.3) + (PMI water x 0.63), where PMI = E-factor + 1).[

40] In this analysis of green metrics, only the synthetic step has been considered and because of this, the E-factor only refers to the organic waste produced in this step. According to the results shown in

Table 3, the synthetic approach developed in this work provided the best TCR results, pointing out its lower CO

2 footprint with respect to the strategies 1-3.

To extend the analysis to other issues like the reagent’s characteristics, incubation conditions and purification, the EcoScale tool was also used. Herein, penalties are assigned as a function of the toxicity, hazard, energy invested, price, work-up, etc. of the overall process (listed in

Table S2). According to the results, this tool has taken into consideration the higher price of the activated acyl donor (

i.e. ethyl palmitate and vinyl decanoate) compared to FFAs, and the reagents and steps involved in each approach. All the penalties assigned reduce the score of the EcoScale for entries 1-3 from 100 % (corresponding to an ideal sustainable reaction) to almost 50 %. Meanwhile, the one here reported obtains a value of 77 % because of the reduction in the range of reagents, the improved safety and simplification of the overall process. A punctuation, that according to the authors of this tool, corresponds to excellent operating conditions.[

41]