Submitted:

13 September 2024

Posted:

14 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Magnetoencephalography Recording

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

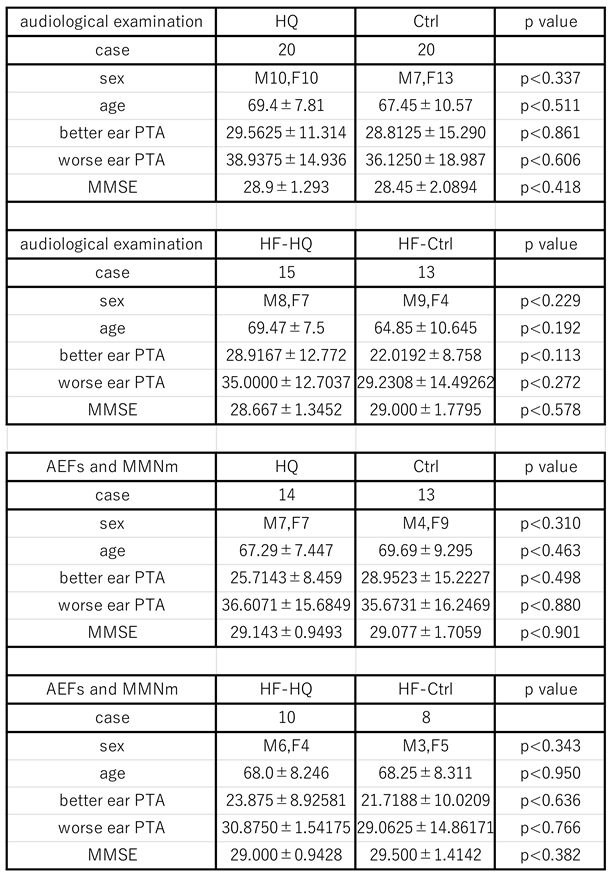

3.1. The Participants

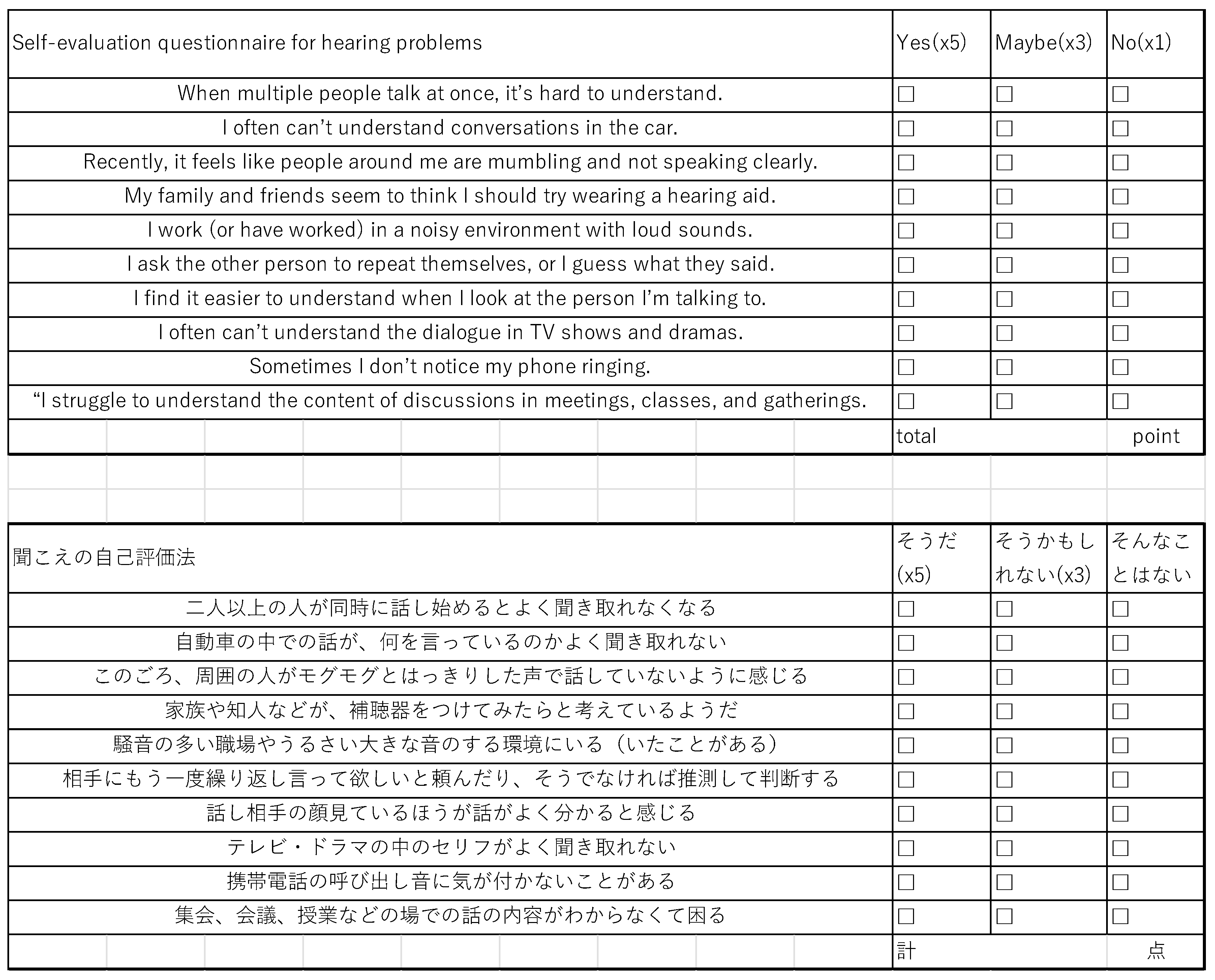

3.2. Self-Evaluation Questionnaire

3.3. PTA Measurement and Speech Perception Test

3.4. Auditory Processing Test

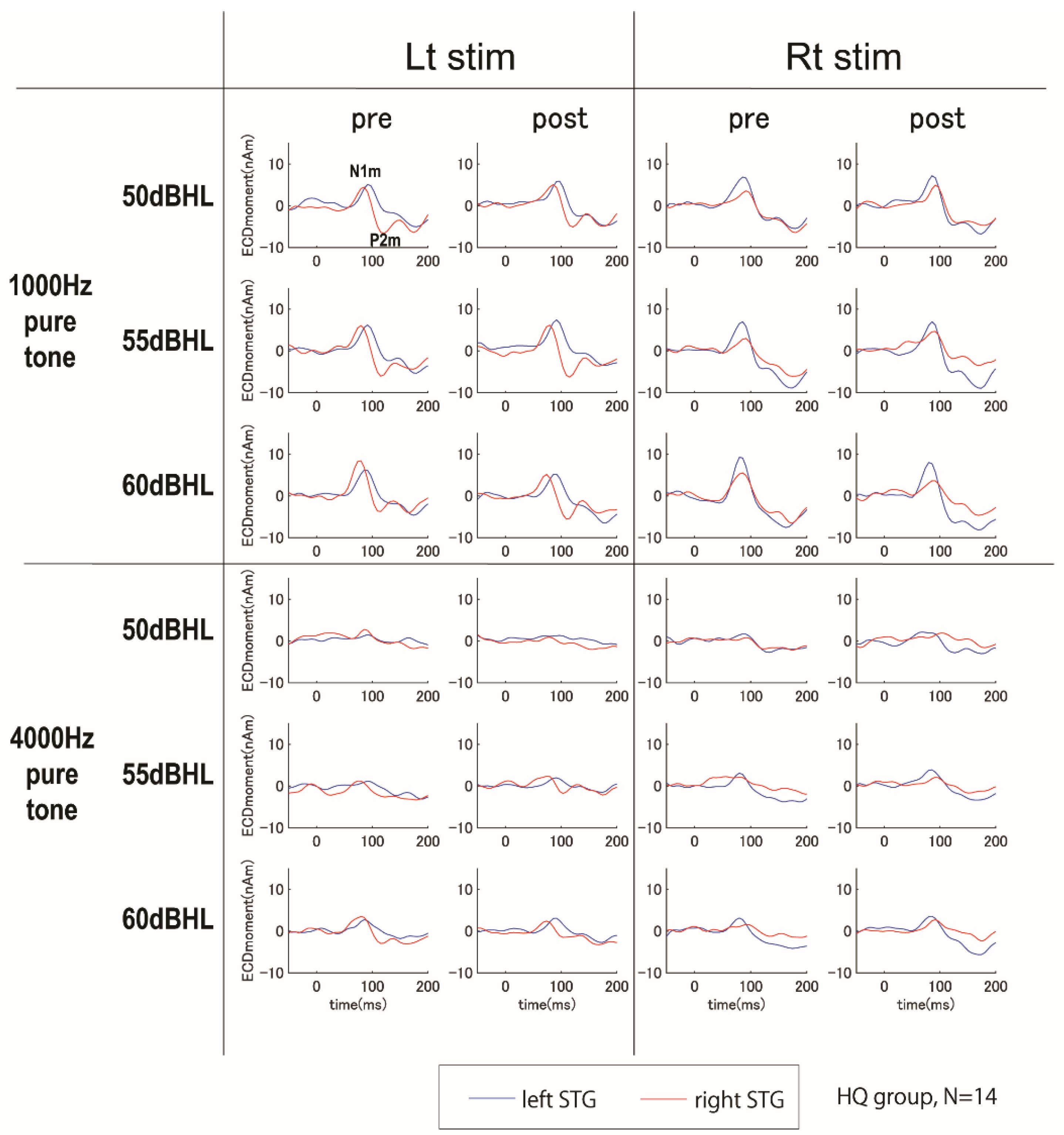

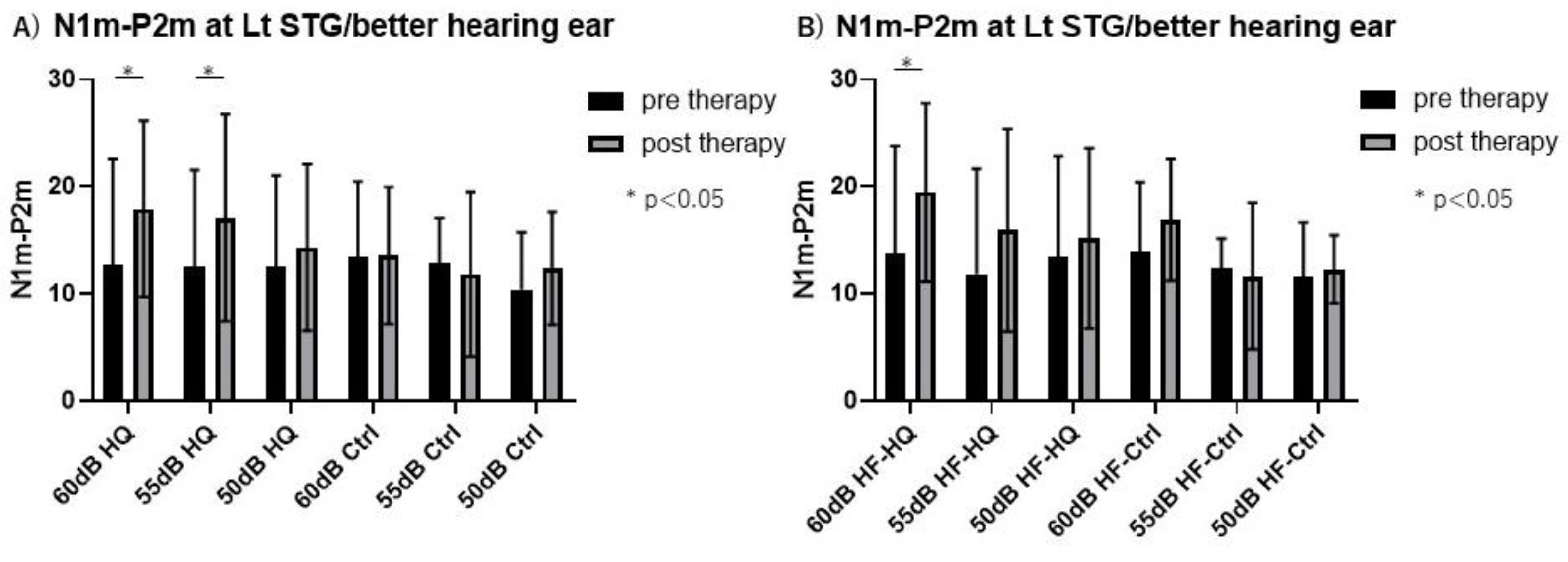

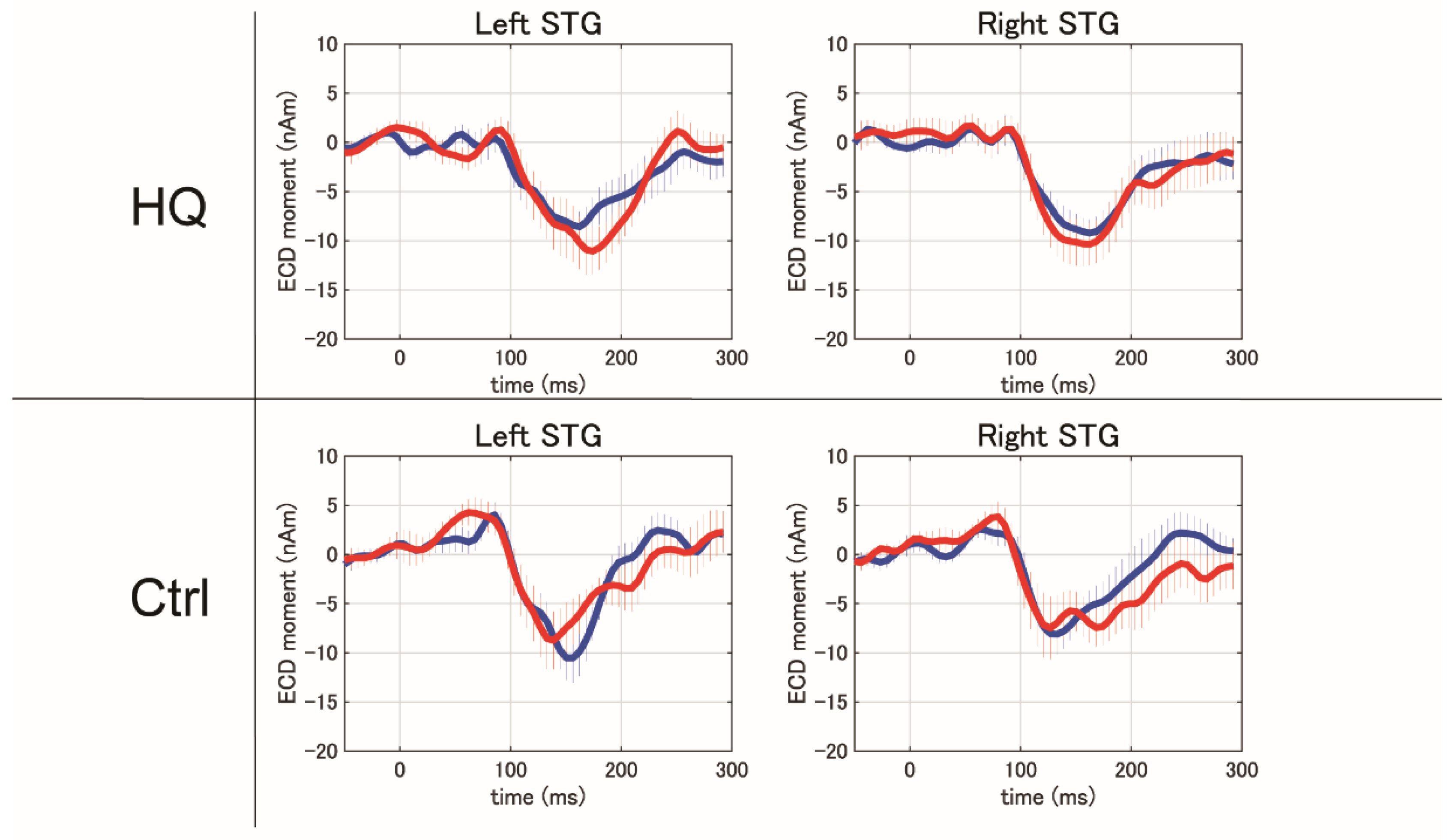

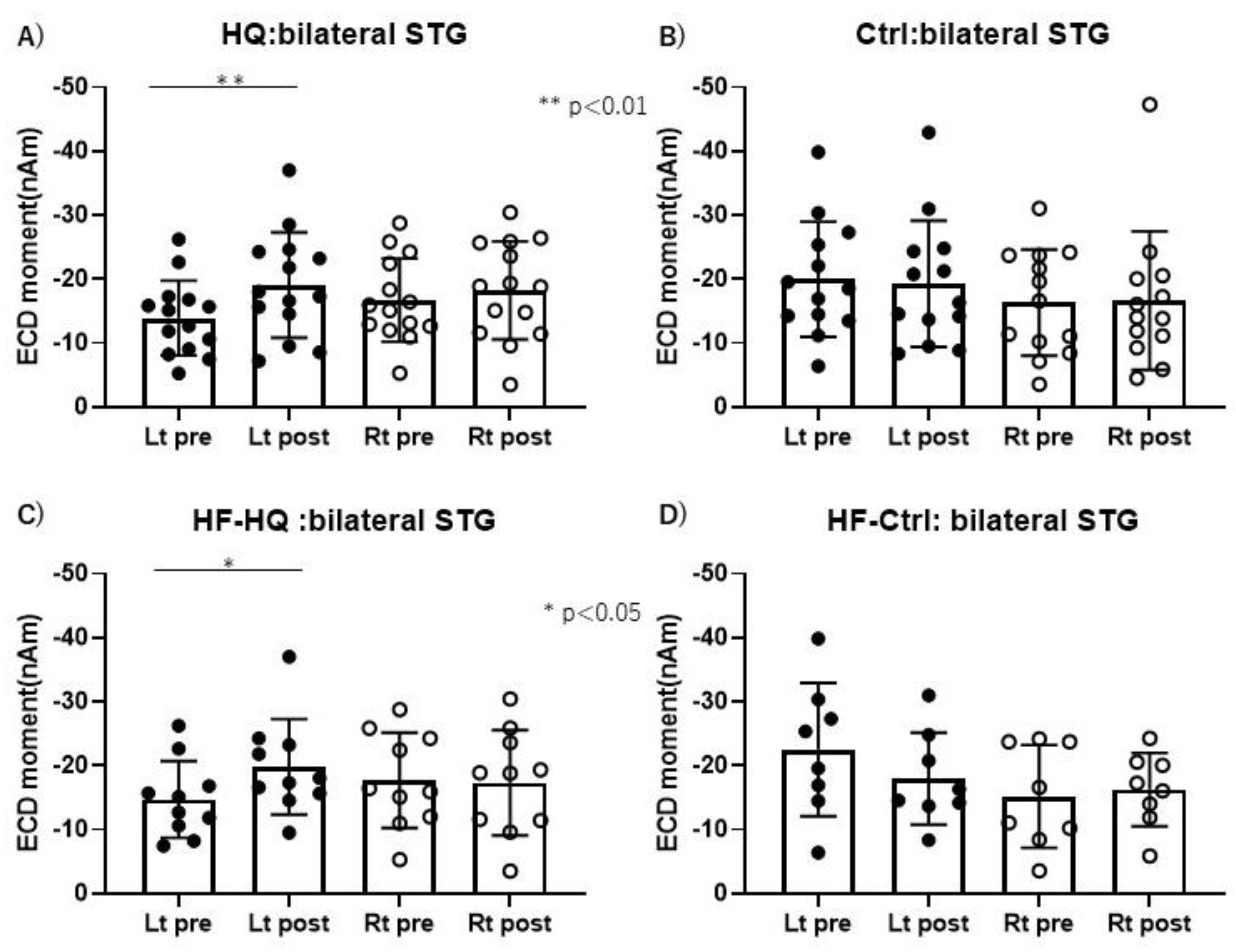

3.5. Magnetoencephalography Recording

4. Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kramer, SE.; Kapteyn, TS.; Houtgast, T. Occupational performance: comparing normally-hearing and hearing-impaired employees using the Amsterdam Checklist for Hearing and Work. Int J Audiol 2006, 45, 503-12. PMID: 17005493. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, M.; Schulte, M.; Zokoll, MA.; Wagener, KC.; Meis, M.; Brand, T.; Holube, I. Relation Between Listening Effort and Speech Intelligibility in Noise. Am J Audiol 2017, 26, 378-392. PMID: 29049622. [CrossRef]

- Schepker, H.; Haeder, K.; Rennies, J.; Holube, I. Perceived listening effort and speech intelligibility in reverberation and noise for hearing-impaired listeners. Int J Audiol 2016, 55, 738-747. Epub 2016 Sep 14. PMID: 27627181. [CrossRef]

- Pichora-Fuller, MK.; Kramer, SE.; Eckert, MA.; Edwards, B.; Hornsby, BW.; Humes, LE.; Lemke, U.; Lunner, T.; Matthen, M.; Mackersie, CL.; Naylor, G.; Phillips, NA.; Richter, M.; Rudner, M.; Sommers, MS.; Tremblay, KL.; Wingfield, A. Hearing Impairment and Cognitive Energy: The Framework for Understanding Effortful Listening (FUEL). Ear Hear 2016, 37, Suppl 1:5S-27S. PMID: 27355771. [CrossRef]

- Downs, DW. Effects of hearing and use on speech discrimination and listening effort. J Speech Hear Disord 1982, 47, 189-93. PMID: 7176597. [CrossRef]

- Hétu, R.; Riverin, L.; Lalande, N.; Getty, L.; St-Cyr, C. Qualitative analysis of the handicap associated with occupational hearing loss. Br J Audiol 1988, 22, 251-64. PMID: 3242715. [CrossRef]

- Holman, JA.; Drummond, A.; Hughes, SE.; Naylor, G. Hearing impairment and daily-life fatigue: a qualitative study. Int J Audiol 2019, 58, 408-416. Epub 2019 Apr 28. PMID: 31032678; PMCID: PMC6567543. [CrossRef]

- Bess, FH.; Hornsby, BW.; Commentary: listening can be exhausting--fatigue in children and adults with hearing loss. Ear Hear 2014, 35, 592-9. PMID: 25255399; PMCID: PMC5603232. [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, BW.; Naylor, G.; Bess, FH. A Taxonomy of Fatigue Concepts and Their Relation to Hearing Loss. Ear Hear 2016, 37 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 136S-44S. PMID: 27355763; PMCID: PMC4930001. [CrossRef]

- Key, AP.; Gustafson, SJ.; Rentmeester, L.; Hornsby, BWY.; Bess, FH. Speech-Processing Fatigue in Children: Auditory Event-Related Potential and Behavioral Measures. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2017, 60, 2090-2104. PMID: 28595261; PMCID: PMC5831094. [CrossRef]

- McGarrigle, R.; Dawes, P.; Stewart, AJ.; Kuchinsky, SE.; Munro, KJ. Measuring listening-related effort and fatigue in school-aged children using pupillometry. J Exp Child Psychol 2017, 161, 95-112. Epub 2017 May 12. PMID: 28505505. [CrossRef]

- Karawani, H.; Jenkins, K.; Anderson S. Restoration of sensory input may improve cognitive and neural function. Neuropsychologia 2018, 114, 203-213. Epub 2018 May 2. PMID: 29729278; PMCID: PMC5988995. [CrossRef]

- Choi, AY.; Shim, HJ.; Lee, SH.; Yoon, SW.; Joo, EJ. Is cognitive function in adults with hearing impairment improved by the use of hearing AIDS? Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2011, 4, 72-76. Epub 2011 May 31. PMID: 21716953; PMCID: PMC3109330. [CrossRef]

- Grapp, M.; Hutter, E.; Argstatter, H.;, Plinkert, PK.; Bolay, HV. Neuro-Music Therapy for Recent-Onset Tinnitus. SAGE Open, 2013, 3, 215824401348969. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H.; Fukushima, M.; Teismann, H.; Lagemann, L.; Kitahara, T.; Inohara, H.; Kakigi, R.; Pantev, C. Constraint-induced sound therapy for sudden sensorineural hearing loss--behavioral and neurophysiological outcomes. Sci Rep. 2014, 4, 3927. PMID: 24473277; PMCID: PMC3905271. [CrossRef]

- Bisgaard, N.; Ruf, S. Findings From EuroTrak Surveys From 2009 to 2015: Hearing Loss Prevalence, Hearing Aid Adoption, and Benefits of Hearing Aid Use. Am J Audiol 2017, 26, :451-461. PMID: 29049628. [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, U.; Hesse, G. Hearing aids: indications, technology, adaptation, and quality control. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017, 16, Doc08. PMID: 29279726; PMCID: PMC5738937. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, CE.; Jilla, AM.; Danhauer, JL.; Sullivan, JC.; Sanchez, KR. Benefits from, Satisfaction with, and Self-Efficacy for Advanced Digital Hearing Aids in Users with Mild Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Semin Hear 2018, 39, 158-171. Epub 2018 Jun 15. PMID: 29915453; PMCID: PMC6003810. [CrossRef]

- Staehelin, K.; Bertoli, S.; Probst, R.; Schindler, C.; Dratva, J.; Stutz, EZ. Gender and hearing aids: patterns of use and determinants of nonregular use. Ear Hear 2011, 32, e26-37. PMID: 21795978. [CrossRef]

- Wong, LL.; Hickson, L.; McPherson, B. Hearing aid satisfaction: what does research from the past 20 years say? Trends Amplif 2003, 7, 117-161. PMID: 15004650; PMCID: PMC4168909. [CrossRef]

- Bertoli, S.; Staehelin, K.; Zemp, E.; Schindler, C.; Bodmer, D.; Probst, R. Survey on hearing aid use and satisfaction in Switzerland and their determinants. Int J Audiol 2009, 48, 183-95. PMID: 19363719. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Nakaishi, S.; Imura, T.; Kawahara, Y.; Hashizume, A.; Kurisu, K.; Yuge, L. Neuromagnetic evaluation of a communication support system for hearing-impaired patients. NeuroReport 2017, 28, 712-719. August 16, 2017. |. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, HG Jr.; Ritter, W. The sources of auditory evoked responses recorded from the human scalp. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1970, 28, 360-367. PMID: 4191187. [CrossRef]

- Liégeois-Chauvel, C.; Musolino, A.; Badier, JM.; Marquis, P.; Chauvel, P. Evoked potentials recorded from the auditory cortex in man: evaluation and topography of the middle latency components. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1994, 92, 204-214. PMID: 7514990. [CrossRef]

- Scherg, M.; Von, Cramon, D. Two bilateral sources of the late AEP as identified by a spatio-temporal dipole model. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1985, 62, 32-44. PMID: 2578376. [CrossRef]

- Näätänen, R.; Picton, T. The N1 wave of the human electric and magnetic response to sound: a review and an analysis of the component structure. Psychophysiology 1987, 24, 375-425. PMID: 3615753. [CrossRef]

- Scarff, CJ.; Reynolds, A.; Goodyear, BG.; Ponton, CW.; Dort, JC.; Eggermont, JJ. Simultaneous 3-T fMRI and high-density recording of human auditory evoked potentials. Neuroimage 2004, 23, 1129-1142. PMID: 15528112. [CrossRef]

- Wyss, C.; Boers, F.; Kawohl, W.; Arrubla, J.; Vahedipour, K.; Dammers, J.; Neuner, I.; Shah, NJ. Spatiotemporal properties of auditory intensity processing in multisensor MEG. Neuroimage 2014, 102, 465-473. Epub 2014 Aug 13. PMID: 25132019. [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, G. Summary of the N1-P2 Cortical Auditory Evoked Potential to Estimate the Auditory Threshold in Adults. Semin Hear 2016, 37, 1-8. PMID: 27587918; PMCID: PMC4910570. [CrossRef]

- Morse, K.; Vander, Werff, KR. Onset-offset cortical auditory evoked potential amplitude differences indicate auditory cortical hyperactivity and reduced inhibition in people with tinnitus. Clin Neurophysiol 2023, 149, 223-233. Epub 2023 Feb 23. PMID: 36963993. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Martin, K.; Roland, P.; Bauer, P.; Sweeney, MH.; Gilley, P.; Dorman, M. P1 latency as a biomarker for central auditory development in children with hearing impairment. J Am Acad Audiol 2005, 16, 564-573. PMID: 16295243. [CrossRef]

- Ching, TY.; Zhang, VW.; Hou, S.; Van, Buynder, P. Cortical Auditory Evoked Potentials Reveal Changes in Audibility with Nonlinear Frequency Compression in Hearing Aids for Children: Clinical Implications. Semin Hear 2016, 37, 25-35. PMID: 27587920; PMCID: PMC4910568. [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M.; Rouhbakhsh, N.; Rahbar, N. Towards early intervention of hearing instruments using cortical auditory evoked potentials (CAEPs): A systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2021, 144, 110698. Epub 2021 Mar 27. PMID: 33839460. [CrossRef]

- Takasago, M.; Kunii, N.; Komatsu, M.; Tada, M.; Kirihara, K.; Uka, T.; Ishishita, Y.; Shimada, S.; Kasai, K.; Saito, N. Spatiotemporal Differentiation of MMN From N1 Adaptation: A Human ECoG Study. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 586. PMID: 32670112; PMCID: PMC7333077. [CrossRef]

- Kucuk, CA.; Dere, HH.; Mujdeci, B. Evaluating the Effectiveness of a New Auditory Training Program on the Speech Recognition Skills and Auditory Event-Related Potentials in Elderly Hearing Aid Users. Audiol Neurootol 2022, 27, 368-376. Epub 2022 Apr 8. PMID: 35398843. [CrossRef]

- Ibraheem, OA.; Kolkaila, EA.; Nada, EH.; Gad, NH. Auditory cortical processing in cochlear-implanted children with different language outcomes. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2020, 277, 1875-1883. Epub 2020 Apr 8. PMID: 32270327. [CrossRef]

- Onuma, N.; Mizuno,E. Needs Assessment for Audiological Support According to the Self-Evaluation of Hearing Problems in Elderly People. Tsukuba College of Technology Techno Report 2001, 8, 145-152.

- Humes, LE. The World Health Organization's hearing-impairment grading system: an evaluation for unaided communication in age-related hearing loss. Int J Audiol 2019, 58, 12-20. Epub 2018 Oct 15. PMID: 30318941; PMCID: PMC6351193. [CrossRef]

- Inui, K.; Okamoto, H.; Miki, K.; Gunji, A.; Kakigi, R. Serial and parallel processing in the human auditory cortex: a magnetoencephalographic study. Cereb Cortex 2006, 16, 18-30. Epub 2005 Mar 30. PMID: 15800024. [CrossRef]

- Gil, D.; Iorio, MC. Formal auditory training in adult hearing aid users. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010, 65, 165-174. PMID: 20186300; PMCID: PMC2827703. [CrossRef]

- Lavie, L.; Banai, K.; Karni, A.; Attias, J. Hearing Aid-Induced Plasticity in the Auditory System of Older Adults: Evidence From Speech Perception. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2015, 58, 1601-1610. PMID: 26163676. [CrossRef]

- Yumba, WK. Cognitive Processing Speed, Working Memory, and the Intelligibility of Hearing Aid-Processed Speech in Persons with Hearing Impairment. Front Psychol 2017, 15, 1308. PMID: 28861009; PMCID: PMC5559705. [CrossRef]

- Moore, BC.; Vinay, SN. Enhanced discrimination of low-frequency sounds for subjects with high-frequency dead regions. Brain 2009, 132(Pt 2), 524-36. Epub 2008 Nov 26. PMID: 19036764. [CrossRef]

- Andrillon, T.; Kouider, S.; Agus, T.; Pressnitzer, D. Perceptual learning of acoustic noise generates memory-evoked potentials. Curr Biol 2015, 25, 2823-2829. Epub 2015 Oct 8. PMID: 26455302. [CrossRef]

- Gommeren, H.; Bosmans, J.; Cardon, E.; Mertens, G.; Cras, P.; Engelborghs, S.; Van, Ombergen, A.; Gilles, A.; Lammers, M.; Van, Rompaey, V. Cortical Auditory Evoked Potentials in Cognitive Impairment and Their Relevance to Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review Highlighting the Evidence Gap. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 781322. PMID: 34867176; PMCID: PMC8637533. [CrossRef]

- Picton, T. Hearing in time: evoked potential studies of temporal processing. Ear Hear 2013, 34, 385-401. PMID: 24005840. [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, BM.; Campeanu, S.; Tremblay, KL.; Alain, C. Auditory evoked potentials dissociate rapid perceptual learning from task repetition without learning. Psychophysiology 2011, 48, 797-807. Epub 2010 Nov 5. PMID: 21054432. [CrossRef]

- Ross, B.; Jamali, S.; Tremblay, KL. Plasticity in neuromagnetic cortical responses suggests enhanced auditory object representation. BMC Neurosci 2013, 14, 151. PMID: 24314010; PMCID: PMC3924184. [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, K.; Kraus, N.; McGee, T.; Ponton, C.; Otis, B. Central auditory plasticity: changes in the N1-P2 complex after speech-sound training. Ear Hear 2001, 22, 79-90. PMID: 11324846. [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, G.; Kennedy, V. Cortical electric response audiometry hearing threshold estimation: accuracy, speed, and the effects of stimulus presentation features. Ear Hear 2006, 27, 443-456. PMID: 16957496. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, EB. Hearing-Aid Directionality Improves Neural Speech Tracking in Older Hearing-Impaired Listeners. Trends Hear 2022, 26, 23312165221099894. PMID: 35730193; PMCID: PMC9228639. [CrossRef]

- Van, Dun, B.; Kania, A.; Dillon, H. Cortical Auditory Evoked Potentials in (Un)aided Normal-Hearing and Hearing-Impaired Adults. Semin Hear 2016, 37, 9-24. PMID: 27587919; PMCID: PMC4910567. [CrossRef]

- Näätänen, R.; Paavilainen, P.; Rinne, T.; Alho, K. The mismatch negativity (MMN) in basic research of central auditory processing: a review. Clin Neurophysiol 2007, 118, 2544-2590. Epub 2007 Oct 10. PMID: 17931964. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, CH.; Baillet, S.; Hsiao, FJ.; Lin, YY. Effects of aging on the neuromagnetic mismatch detection to speech sounds. Biol Psychol 2015, 104, 48-55. Epub 2014 Nov 15. PMID: 25451380. [CrossRef]

- Korczak, PA.; Kurtzberg, D.; Stapells, DR. Effects of sensorineural hearing loss and personal hearing AIDS on cortical event-related potential and behavioral measures of speech-sound processing. Ear Hear 2005, 26, 165-185. PMID: 15809543. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liang, M.; Zhao, F.; Yu, G.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, G. Auditory Spatial Discrimination and the Mismatch Negativity Response in Hearing-Impaired Individuals. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0136299. PMID: 26305694; PMCID: PMC4549058. [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Sun, X. A mismatch negativity study in Mandarin-speaking children with sensorineural hearing loss. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2016, 91, 128-140. Epub 2016 Oct 24. PMID: 27863627. [CrossRef]

- Nikjeh, DA.; Lister, JJ.; Frisch, SA. Preattentive cortical-evoked responses to pure tones, harmonic tones, and speech: influence of music training. Ear Hear 2009, 30, 432-446. PMID: 19494778. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ma, Y. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation improves both hearing function and tinnitus perception in sudden sensorineural hearing loss patients. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 14796. PMID: 26463446; PMCID: PMC4604476. [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y.; Nishita, Y.; Tange, C.; Sugiura, S.; Otsuka, R.; Ueda, H.; Nakashima, T.; Ando, F.; Shimokata, H. The Longitudinal Impact of Hearing Impairment on Cognition Differs According to Cognitive Domain. Front Aging Neurosci 2016, 8, 201. PMID: 27597827; PMCID: PMC4992677. [CrossRef]

- Acar, B.; Yurekli, MF.; Babademez, MA.; Karabulut, H.; Karasen, RM. Effects of hearing aids on cognitive functions and depressive signs in elderly people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2011, 52, 250-252. Epub 2010 May 15. PMID: 20472312. [CrossRef]

- Allen, NH.; Burns, A.; Newton, V.; Hickson, F.; Ramsden, R.; Rogers, J.; Butler, S.; Thistlewaite, G.; Morris, J. The effects of improving hearing in dementia. Age Ageing 2003, 32, 189-193. PMID: 12615563. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).